2017-12-05 Tue

■ #3144. 英語音韻史における long ash 1 と long ash 2 [vowel][diphthong][oe][germanic][phonetics][i-mutation][oe_dialect][pronunciation][phoneme]

英語音韻史では慣例として,古英語の West-Saxon 方言において <æ> で綴られる長母音は,その起源に応じて2種類に区別される.それぞれ伝統的に ǣ1 と ǣ2 として言及されることが多い(ただし,厄介なことに研究者によっては 1 と 2 の添え字を逆転させた言及もみられる).この2種類は,中英語以降の歴史においても方言によってしばしば区別されることから,方言同定に用いられるなど,英語史研究上,重要な役割を担っている.

中尾 (75--76) によれば,ゲルマン語比較言語学上,ǣ1 と ǣ2 の起源は異なっている.ǣ1 は西ゲルマン語の段階での *[aː]- が鼻音の前位置を除き West-Saxon 方言において前舌化したもので,non-West-Saxon 方言ではさらに上げを経て [eː] となった (ex. dǣd "deed", lǣtan "let", þǣr "there") .一方,ǣ2 は西ゲルマン語の *[aɪ] が古英語までに [ɑː] へ変化したものが,さらに i-mutation を経た出力である (ex. lǣran "teach", dǣlan "deal") .これは,West-Saxon のみならず Anglian でも保たれたが,Kentish では上げにより [eː] となった.したがって,ǣ1 と ǣ2 の音韻上の関係は,West-Saxon では [æː] : [æː],Anglian では [eː] : [æː],Kentish では [eː] : [eː] となる.まとめれば,以下の通り.

PGmc aː > OE WS æː NWS æː > eː WGmc aɪ > OE ɑː > (i-mutation) WS, Angl æː K æː > eː

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

2017-08-27 Sun

■ #3044. 古英語の中点による分かち書き [punctuation][writing][manuscript][oe][distinctiones]

英語の分かち書きについて,以下の記事で話題にしてきた.「#1112. 分かち書き (1)」 ([2012-05-13-1]),「#1113. 分かち書き (2)」 ([2012-05-14-1]),「#2695. 中世英語における分かち書きの空白の量」 ([2016-09-12-1]),「#2696. 分かち書き,黙読習慣,キリスト教のテキスト解釈へのこだわり」 ([2016-09-13-1]),「#2970. 分かち書きの発生と続け書きの復活」 ([2017-06-14-1]),「#2971. 分かち書きは句読法全体の発達を促したか?」 ([2017-06-15-1]) .

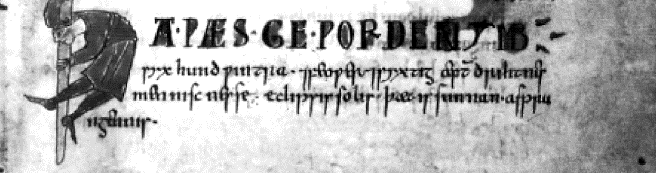

現代的な語と語の分かち書きは,古英語ではまだ完全には発達していなかったが,語の分割する方法は確かに模索されていた.しかし,ある方法をとるにしても,その使い方はたいてい一貫しておらず,いかにも発展途上という段階にみえるのである.1例として,空白とともに中点 <・> を用いている Bede の Historia Ecclesiastica, III, Bodleian Library, Tanner MS 10, 54r. より冒頭の4行を再現しよう(Crystal 19).

ÞA・ǷÆS・GE・WORDENYMB

syx hund ƿyntra・7feower7syxtig æft(er) drihtnes

menniscnesse・eclipsis solis・þæt is sunnan・aspru

ngennis・

then was happened about

six hundred winters・and sixty-four after the lord's

incarnation・(in Latin) eclipse of the sun・that is sun eclipse

まず,空白と中点の2種類の分かち書きが,一見するところ機能の差を示すことなく併用されているという点が目を引く.また,現代の感覚としては,分割すべきところに分割がなく(7 [= "and"] の周辺),逆に分割すべきでないところに分割がある(題名の GE・WORDENYMB にみられる接頭辞と語幹の間)という点も興味深い.

空白で分かち書きする場合,手書きの場合には語と語の間にどのくらいの空白を挿入するかという問題があり,狭すぎると分割機能が脅かされる可能性があるが,中点は(前後の文字のストロークと融合しない限り)狭い隙間でも打てるといえば打てるので,有用性はあるように思われる.

中点は,英語に限らず古代の書記にしばしば見られたし,自然な句読法の1つといってよいだろう.現代日本語でも,中点は特殊な用法をもって活躍している.

・ Crystal, David. Making a Point: The Pernickety Story of English Punctuation. London: Profile Books, 2015.

2017-08-21 Mon

■ #3038. 古英語アルファベットは27文字 [alphabet][oe][ligature][thorn][th][grapheme]

現代英語のアルファベットは26文字と決まっているが,英語史の各段階でアルファベットを構成する文字の種類の数は,多少の増減を繰り返してきた.例えば古英語では,現代英語にある文字のうち3つが使われておらず,逆に古英語特有の文字が4つほどあった.26 - 3 + 4 = 27 ということで,古英語のアルファベットには27の文字があったことになる.

| PDE | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z | ||||

| OE | a | æ | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | (k) | l | m | n | o | p | (q) | r | s | t | þ | ð | u | ƿ | (x) | y | (z) |

「#17. 注意すべき古英語の綴りと発音」 ([2009-05-15-1]) の表とは若干異なるが,古英語に存在はしたがほどんど用いられない文字をアルファベット・セットに含めるか含めないかの違いにすぎない.上の表にてカッコで示したとおり,古英語では <k>, <q>, <x>, <z> はほとんど使われておらず,体系的には無視してもよいくらいのものである.

古英語に特有の文字として注意すべきものを取り出せば,(1) <a> と <e> の合字 (ligature) である <æ> (ash),(3) th 音(無声と有声の両方)を表わす <þ> (thorn) と,同じく (3) <ð> (eth),(4) <w> と同機能で用いられた <ƿ> (wynn) がある.

現代英語のアルファベットが26文字というのはあまりに当たり前で疑うこともない事実だが,昔から同じ26文字でやってきたわけではないし,今後も絶対に変わらないとは言い切れない.歴史の過程で今たまたま26文字なのだと認識することが必要である.

2017-07-20 Thu

■ #3006. 古英語の辞書 [lexicography][dictionary][oe][doe][bibliography][hel_education][link]

古英語を学習・研究する上で有用な辞書をいくつか紹介する.

(1) Bosworth, Joseph. A Compendious Anglo-Saxon and English Dictionary. London: J. R. Smith, 1848.

(2) Bosworth, Joseph and Thomas N. Toller. Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Oxford: OUP, 1973. 1898. (Online version available at http://lexicon.ff.cuni.cz/texts/oe_bosworthtoller_about.html.)

(3) Hall, John R. C. A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Rev. ed. by Herbert T. Merritt. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 1996. 1896. (Online version available at http://lexicon.ff.cuni.cz/texts/oe_clarkhall_about.html.)

(4) Healey, Antonette diPaolo, Ashley C. Amos and Angus Cameron, eds. The Dictionary of Old English in Electronic Form A--G. Toronto: Dictionary of Old English Project, Centre for Medieval Studies, U of Toronto, 2008. (see The Dictionary of Old English (DOE) and Dictionary of Old English Corpus (DOEC).)

(5) Sweet, Henry. The Student's Dictionary of Anglo-Saxon. Cambridge: CUP, 1976. 1896.

おのおのタイトルからも想像されるとおり,詳しさや編纂方針はまちまちである.入門用の Sweet に始まり,簡略辞書の Hall から,専門的な Bosworth and Toller を経て,最新の Healey et al. による電子版 DOE に至る.DOE を除いて,古英語辞書の定番がおよそ19世紀末の産物であることは注目に値する.この時期に,様々なレベルの古英語辞書が,独自の規範・記述意識をもって編纂され,出版されたのである.

現代風の書き言葉の標準が明確に定まっていない古英語の辞書編纂では,見出し語をどのような綴字で立てるかが悩ましい問題となる.使用者は,たいてい適切な綴字を見出せないか,あるいは異綴りの間をたらい回しにされるかである.大雑把にいえば,入門的な Sweet の立てる見出しの綴字は "critical" で規範主義的であり,最も専門的な DOE は "diplomatic" で記述主義的である.その間に,緩やかに "critical" な Hall と緩やかに "diplomatic" な Bosworth and Toller が位置づけられる.

合わせて古英語語彙の学習には,以下の2点を挙げておこう.

・ Barney, Stephen A. Word-Hoard: An Introduction to Old English Vocabulary. 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale UP, 1985.

・ Holthausen, Ferdinand. Altenglisches etymologisches Wōrterbuch. Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, 1963.

Holthausen の辞書は,古英語語源辞書として専門的かつ特異な地位を占めているが,語源から語彙を学ぼうとする際には役立つ.Barney は,同じ趣旨で,かつ読んで楽しめる古英語単語リストである.

2017-05-25 Thu

■ #2950. 西ゲルマン語(から最初期古英語にかけての)時代の音変化 [sound_change][germanic][oe][vowel][diphthong][phonetics][frisian]

「#2942. ゲルマン語時代の音変化」 ([2017-05-17-1]) に引き続き,Hamer (15) より,標題の時代に関係する2つの音変化を紹介する.

| Sound change | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| D | The diphthongs all developed as follows: ai > ā, au > ēa (ēa = ǣa), eu > ēo, iu > īo. (This development of eu and iu was in fact very much later, but it is placed here in the interests of simplification.) | |

| E | a > æ unless it came before a nasal consonant. | dæg, glæd, but land/lond. |

E は Anglo-Frisian Brightening あるいは First Fronting と呼ばれる音過程を指し,Lass (42) によると,以下のように説明される.

The effects can be seen in comparing say OE dæg, OFr deg with Go dags, OIc dagr, OHG tag. (The original [æ] was later raised in Frisian.)

In outline, AFB turns low back */留/ to [æ], except before nasals (hence OE, OHG mann but dæg vs. tag. It is usually accepted that at some point before AFB (which probably dates from around the early fifth century), */留/ > [留̃] before nasals, and the nasalized vowel blocked AFB.

AFB は古英語の名詞屈折などにおける厄介な異形態を説明する音変化として重要なので,古英語学習者は気に留めておきたい.

・ Hamer, R. F. S. Old English Sound Changes for Beginners. Oxford: Blackwell, 1967.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2017-05-17 Wed

■ #2942. ゲルマン語時代の音変化 [sound_change][germanic][oe][vowel][i-mutation]

英語の音韻史を学ぼうとすると,古英語以前から現代英語にかけて,あまりに多数の音変化が起こってきたので目がクラクラするほどだ.本ブログでも,これまで個々には多数の音変化を扱ってきたが,より体系的に主要なものだけでも少しずつ提示していき,蓄積していければと思っている.

今回は,Hamer (14--15) の古英語音変化入門書より,古英語に先立つゲルマン語時代の3種の注目すべき母音変化を紹介する.

| Sound change | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| A | u > o unless followed by a nasal consonant, or by u or i/j in the following syllable. (By this is meant if the vowel element of the following syllable consisted of any u sound, or of any i sound or of any combination beginning with j.) | bunden, holpen are both OE p.p. of Class III Strong Verbs, the u of bunden having been retained, because of the following n. god, gyden = 'god', goddess. gyden had earlier had i instead of e in its ending, and this i first caused the u to survive, then later caused it to change to y by i-mutation (see I below). Thus both the o and y in these forms derive from Gmc. u. |

| B | e > i if followed by a nasal consonant, or by i/j in the following syllable. | bindan, helpan are both OE infin. of Class III Strong Verbs. helpan has 3 sg. pres indic. hilpþ < Gmc. *hilpiþi. |

| C | eu > iu before i/j in the following syllable. |

A については,「#1471. golden を生み出した音韻・形態変化」 ([2013-05-07-1]) も参照.A, B に共通する bindan の語形については,「#2084. drink--drank--drunk と win--won--won」 ([2015-01-10-1]) をどうぞ.また,いずれの音変化にも i-mutation が関与していることに注意.

・ Hamer, R. F. S. Old English Sound Changes for Beginners. Oxford: Blackwell, 1967.

2017-04-20 Thu

■ #2915. Beowulf の冒頭52行 [beowulf][link][oe][literature][popular_passage][oe_text]

「#2893. Beowulf の冒頭11行」 ([2017-03-29-1]) で挙げた11行では物足りなく思われたので,有名な舟棺葬 (ship burial) の記述も含めた Beowulf 冒頭の52行を引用したい.舟棺葬とは,6--11世紀にスカンディナヴィアとアングロサクソンの文化で見られた高位者の葬法である.

原文は Jack 版で.現代英語訳は Norton Anthology に収録されているアイルランドのノーベル文学賞受賞詩人 Seamus Heaney の版でお届けする.

| OE | PDE translation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| a-verse | b-verse | ||

| Hwæt, wē Gār-Dena | in geārdagum, | So. The Spear-Danes in days gone by | |

| þēodcyninga | þrym gefrūnon, | and the kings who ruled them had courage and greatness. | |

| hū ðā æþelingas | ellen fremedon. | We have heard of those princes' heroic campaigns. | |

| Oft Scyld Scēfing | sceaþena þrēatum, | There was Shield Sheafson, scourge of many tribes, | |

| 5 | monegum mǣgþum | meodosetla oftēah, | a wrecker of mead-benches, rampaging among foes. |

| egsode eorl[as], | syððan ǣrest wearð | This terror of the hall-troops had come far. | |

| fēasceaft funden; | hē þæs frōfre gebād, | A foundling to start with, he would flourish later on | |

| wēox under wolcnum, | weorðmyndum þāh, | as his powers waxed and his worth was proved. | |

| oðþæt him ǣghwylc þ[ǣr] | ymbsittendra | In the end each clan on the outlying coasts | |

| 10 | ofer hronrāde | hȳran scolde, | beyond the whale-road had to yield to him |

| gomban gyldan. | Þæt wæs gōd cyning! | and begin to pay tribute. That was one good king. | |

| Ðǣm eafera wæs | æfter cenned | Afterward a boy-child was born to Shield, | |

| geong in geardum, | þone God sende | a cub in the yard, a comfort sent | |

| folce tō frōfre; | fyrenðearfe ongeat | by God to that nation. Hew knew what they had tholed, | |

| 15 | þ[e] hīe ǣr drugon | aldor[lē]ase | the long times and troubles they'd come through |

| lange hwīle. | Him þæs Līffrēa, | without a leader; so the Lord of Life, | |

| wuldres Wealdend | woroldāre forgeaf; | the glorious Almighty, made this man renowned. | |

| Bēowulf wæs brēme | ---blǣd wīde sprang--- | Shield had fathered a famous son: | |

| Scyldes eafera | Scedelandum in. | Beow's name was known through the north. | |

| 20 | Swā sceal [geong g]uma | gōde gewyrcean, | And a young prince must be prudent like that, |

| fromum feohgiftum | on fæder [bea]rme, | giving freely while his father lives | |

| þæt hine on ylde | eft gewunigen | so that afterward in age when fighting starts | |

| wilgesīþas | þonne wīg cume, | steadfast companions will stand by him | |

| lēode gelǣsten; | lofdǣdum sceal | and hold the line. Behavior that's admired | |

| 25 | in mǣgþa gehwǣre | man geþēon. | is the path to power among people everywhere. |

| Him ðā Scyld gewāt | tō gescæphwīle, | Shield was still thriving when his time came | |

| felahrōr fēran | on Frēan wǣre. | and he crossed over into the Lord's keeping. | |

| Hī hyne þā ætbǣron | tō brimes faroðe, | His warrior band did what he bade them | |

| swǣse gesīþas, | swā hē selfa bæd, | when he laid down the law among the Danes: | |

| 30 | þenden wordum wēold | wine Scyldinga; | they shouldered him out to the sea's flood, |

| lēof landfruma | lange āhte. | the chief they revered who had long ruled them. | |

| Þǣr æt hȳðe stōd | hringedstefna | A ring-whorled prow rode in the harbor, | |

| īsig ond ūtfūs, | æþelinges fær; | ice-clad, outbound, a craft for a prince. | |

| ālēdon þā | lēofne þēoden, | They stretched their beloved lord in his boat, | |

| 35 | bēaga bryttan | on bearm scipes, | laid out by the mast, amidships, |

| mǣrne be mæste. | Þǣr wæs mādma fela | the great ring-giver. Far-fetched treasures | |

| of feorwegum, | frætwa gelǣded; | were piled upon him, and precious gear. | |

| ne hȳrde ic cȳmlīcor | cēol gegyrwan | I never heard before of a ship so well furbished | |

| hildewǣpnum | ond heaðowǣdum, | with battle-tackle, bladed weapons | |

| 40 | billum ond byrnum; | him on bearme læg | and coats of mail. The massed treasure |

| mādma mænigo, | þā him mid scoldon | was loaded on top of him: it would travel far | |

| on flōdes ǣht | feor gewītan. | on out into the ocean's sway. | |

| Nalæs hī hine lǣssan | lācum tēodan, | They decked his body no less bountifully | |

| þēodgestrēonum, | þon þā dydon | with offerings than those first ones did | |

| 45 | þe hine æt frumsceafte | forð onsendon | who cast him away when he was a child |

| ǣnne ofer ȳðe | umborwesende. | and launched him alone out over the waves. | |

| Þā gȳt hie him āsetton | segen g[yl]denne | And they set a gold standard up | |

| hēah ofer hēafod, | lēton holm beran, | high above his head and let him drift | |

| gēafon on gārsecg. | Him wæs geōmor sefa, | to wind and tide, bewailing him | |

| 50 | murnende mōd. | Men ne cunnon | and mourning their loss. No man can tell, |

| secgan tō sōðe, | selerǣden[d]e, | no wise man in hall or weathered veteran | |

| hæleð under heofenum, | hwā þǣm hlæste onfēng. | knows for certain who salvaged that load. | |

・ Jack, George, ed. Beowulf: A Student Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1994.

・ Greenblatt, Stephen, ed. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 8th ed. New York:: Norton, 2006.

2017-04-17 Mon

■ #2912. AElfric's Life of King Oswald [oe][literature][popular_passage][pchron][oe_text]

Ælfric の説教集の第3弾とされる The Lives of the Saints は,998年までに書かれたとされる.そのなかから Life of King Oswald の冒頭部分をサンプル・テキストとして取り上げよう.King Oswald は633--641年にノーサンブリアを治めた王で,その子孫とともに十字架を篤く崇拝した者として知られている.ルーン文字の刻まれたノーサンブリアの有名な Ruthwell Cross も,そのような十字架崇拝の伝統の所産だろう.

Ælfric の説教集は多くの写本で現存しているが,以下の Smith 版テキストは,MS London, British Library Cotton Julius E.vii のものである.現代英語訳も付けて示す (Smith 132--33) .

Æfter ðan ðe Augustīnus tō Engla lande becōm, wæs sum æðele cyning, Oswold gehāten, on Norðhumbra lande, gelȳfed swyþe on God. Sē fērde on his iugoðe fram his frēondum and māgum tō Scotlande on sǣ, and þǣr sōna wearð gefullod, and his gefēran samod þe mid him sīðedon. Betwux þām wearð ofslagen Eadwine his ēam, Norðhumbra cynincg, on Crīst gelȳfed, fram Brytta cyninge, Ceadwalla gecīged, and twēgen his æftergengan binnan twām gēarum; and se Ceadwalla slōh and tō sceame tūcode þā Norðhumbran lēode æfter heora hlāfordes fylle, oð þæt Oswold se ēadiga his yfelnysse ādwǣscte. Oswold him cōm tō, and him cēnlīce wið feaht mid lȳtlum werode, ac his gelēafa hine getrymde, and Crīst gefylste tō his fēonda slege. Oswold þā ærǣrde āne rōde sōna Gode tō wurðmynte, ǣr þan þe hē tō ðām gewinne cōme, and clypode tō his gefērum:`Uton feallan tō ðǣre rōde, and þone Ælmihtigan biddan þæt hē ūs āhredde wið þone mōdigan fēond þe ūs āfyllan wile. God sylf wāt geare þæt wē winnað rihtlīce wið þysne rēðan cyning tō āhreddenne ūre lēode.' Hī fēollon þā ealle mid Oswolde cyninge on gebedum; and syþþan on ǣrne mergen ēodon tō þām gefeohte, and gewunnon þǣr sige, swā swā se Eallwealdend heom ūðe for Oswoldes gelēafan; and ālēdon heora fȳnd, þone mōdigan Cedwallan mid his micclan werode, þe wēnde þaet him ne mihte nān werod wiðstandan.

After Augustine came to England, there was a certain noble king, called Oswald, in the land of the Northumbrians, who believed very much in God. He travelled in his youth from his friends and kinsmen to Dalriada ("Scotland in sea"), and there at once was baptised, and his companions also who travelled with him. meanwhile his uncle Edwin, king of the Northumbrians, who believed in Christ, was slain by the king of the Britons, named Ceadwalla, as were two of his successors within two years; and that Ceadwalla slew and humiliated the Northumbrian people after the death of their lord, until Oswald the blessed put an end to his evil-doing. Oswald came to him, and fought with him boldly with a small troop, but his faith strengthened him, and Christ assisted in the slaying of his enemies. Oswald then immediately raised up a cross in honour of God, before he came to the battle, and called to his companions: "Let us kneel to the cross, and pray to the Almighty that he rid us from the proud enemy who wishes to destroy us. God himself knows well that we strive rightly against this cruel king in order to redeem our people." They then all knelt with King Oswald in prayers; and then early on the morrow they went to the fight, and gained victory there, just as the All-powerful granted them because of Oswald's faith; and they laid low their enemies, the proud Ceadwalla with his great troop, who believed that no troop could withstand him.

・ Smith, Jeremy J. Old English: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge: CUP, 2009.

2017-04-14 Fri

■ #2909. Peterborough Chronicle の Early Britain の記述 [oe][literature][popular_passage][pchron][oe_text][pictish][kochushoho]

何回目かになる,古英語のテキストとその現代英語訳を挙げるシリーズ(oe_text) .今回は,The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle のE写本,いわゆる Peterborough Chronicle からのテキストで,ブリテン島の地理,民族,言語,歴史が述べられている部分を抜粋する.初学者用に綴字の標準化された市河・松浪版 (86--89) より,現代英語訳も合わせて示す.

Brytene īeȝland is eahta hund mīla lang, and twā hund mīla brād. And hēr sind on þȳs īeȝlande fīf ȝeþēodu: Englisc, and Brytwilisc, and Scyttisc, and Pyhtisc, and Bōclæden. Ǣrest wǣron būend þisses landes Bryttas; þā cōmon of Armenia, and ȝesǣton sūðewearde Brytene ǣrest. Þā ȝelamp hit þæt Pyhtas cōmon sūþan of Scithian, mid langum scipum, nā manigum. And þā cōmon ǣrest on Norþ-Ibernia ūp, and þǣr bǣdon Scottas þæt hīe ðǣr mōsten wunian. Ac hīe noldon him līefan, for ðǣm hīe cwǣdon þæt hīe ne mihten ealle ætgædere ȝewunian þǣr. And þā cwǣdon þā Scottas, `Wē ēow magon þēah hwæðere rǣd ȝelǣran, wē witon ōþer īeȝland hēr bē ēastan, þǣr ȝē magon eardian ȝif ȝē willað, and ȝif hwā ēow wiðstent, wē ēow fultumiað þæt ȝē hit mæȝen ȝegān.'

ðā fērdon þā Pyhtas, and ȝefērdon þis land norþanweard, and sūþanweard hit hæfdon Bryttas, swā wē ǣr cwǣdon. And þā Pyhtas him ābǣdon wīf æt Scottas, on þā ȝerād þæt hīe ȝecuren hiera cynecynn ā on þā wīfhealfe. Þæt hīe hēoldon swā lange siððan. And þā ȝelamp hit ymbe ȝēara ryne þæt Scotta sum dǣl ȝewāt of Ibernian on Brytene, and þæs landes sumne dǣl ȝeēodon. And wæs hiera heretoga Reoda ȝehāten, from þǣm hie sind ȝenemnode Dǣl Reodi.

The island of Britain is eight hundred miles long, and two hundred miles broad. And here in this island are five languages: English, British, Pictish, and Latin. At first the inhabitants of this island were Britons; they came from Armenia, and first occupied Britain in the south (i.e. the southern part of Britain). Then it happened that the Picts came from the south from Scythia, with warships, not many. And they first landed in North Ireland, and there begged the Scots that they might dwell there. But they (= the Scots) would not allow them, because they said that they could not live there all together. And then the Scots said, `We can, however, give you advice: we know another island to the east from here, where you can dwell, if you wish; and if anyone resists you, we will help you that you may conquer it.'

Then the Picts went away, and conquered the northern part of this land, and the Britons had the southern part of it, as we have said before. And the Picts asked wives for them from the Scots, on the conditions that they should choose their royal line always on the female side. They kept it for a long time. And it happened then, in the course of years, that some portion of the Scots departed from Ireland to Britain, and conquered some part of the land, And their leader was called Reoda; from him they are named (the people) of Dal Rialda.

・ 市河 三喜,松浪 有 『古英語・中英語初歩』 研究社,1986年.

2017-04-11 Tue

■ #2906. 古英語聖書より「種をまく人の寓話」 [oe][popular_passage][bible][literature][oe_text][hel_education][kochushoho]

「#2895. 古英語聖書より「岩の上に家を建てる」」 ([2017-03-31-1]) に引き続き,新約聖書を古英語訳で読んでみよう.今回は,同じくよく知られた Matthew 13: 3--8 の「種をまく人の寓話」を紹介する.市川・松浪 (84--86) より,現代英語訳も付して示す.

Sōþlīċe ūt ēode se sāwere his sǣd tō sāwenne. And þā þā hē sēow, sumu hīe fēollon wiþ weȝ, and fuglas cōmon and ǣton þā. Sōþlīċe sumu fēollon on stǣnihte, þǣr hit næfde miċle eorþan, and hrædlīċe ūp sprungon, for þǣm þe hīe næfdon þāre eorþen dēopan; sōþlīċe, ūp sprungenre sunnan, hīe ādrūgodon and forscruncon, for þǣm þe hīe næfdon wyrtruman. Sōþlīċe sumu fēollon on þornas, and þā þornas wēoxon, and forþrysmdon þā. Sumu sōþlīċe fēollon on gōde eorþan, and sealdon wæstm, sum hundfealdne, sum siextiȝfealdne, sum þrītiȝfealdne.

Truly the sower went out to sow his seeds. And while he was sowing, some of them fell along the way, and birds came and ate them. Truly some fell on stony ground where it had not much earth, and quickly sprang up, because they had not any deep earth; truly, the sun (being) risen up, they dried up and shrank up, because they had not roots. Truly some fell on thorns, and the thorns grew, and choked them. Some truly fell on good ground, and gave fruit, some hundredfold, some sixtyfold, (and) some thirtyfold.

・ 市河 三喜,松浪 有 『古英語・中英語初歩』 研究社,1986年.

2017-04-07 Fri

■ #2902. Pope Gregory のキリスト教布教にかける想いとダジャレ [oe][literature][popular_passage][christianity][oe_text][pun][kochushoho]

古英語末期を代表する散文作家 Ælfric (955--1010) は,標準的な West-Saxon 方言で多くの文章を残した.今回は,Catholic Homilies の第2集に収められた,Pope Gregory のイングランド伝道に対する熱い想いを綴った,有名なテキストを紹介しよう.市川・松浪のエディション (105--10) の POPE GREGORY より,古英語テキストと現代英語訳を示す.

Þā underȝeat se pāpa þe on ðām tīman þæt apostoliċe setl ȝesæt, hū sē ēadiga Grēgōrius on hālgum mæȝnum ðēonde wæs, and hē ðā hine of ðǣre munuclican drohtnunge ȝenam, and him tō ȝefylstan ȝesette, on diaconhāde ȝeendebyrdne. Ðā ȝelāmp hit æt sumum sǣle, swā swā ȝȳt foroft dēð, þæt englisce ċȳpmenn brōhton heora ware tō Rōmāna byriȝ, and Gregorius ēode be ðǣre strǣt tō ðām engliscum mannum heora ðing scēawiȝende. Þā ȝeseah hē betwux ðām warum, ċȳpecnihtas ȝesette, þā wǣron hwītes līchaman and fæȝeres andwlitan menn, and æðelīċe ȝefexode.

Grēgōrius ðā behēold þǣra cnapena wlite, and befrān of hwilċere þēode hī ȝebrohte wǣron. Þā sǣde him man þæt hī of engla lande wǣron, and þæt ðǣre ðēode mennisc swā wlitiȝ wǣre. Eft ðā Grēgōrius befrān, hwæðer þæs landes folc cristen wǣre ðe hǣðen. Him man sǣde þæt hī hǣðene wǣron. Grēgōrius ðā of innweardre heortan langsume siċċetunge tēah, and cwæð: “Wā lā wā, þæt swa fæȝeres hīwes menn sindon ðām sweartan dēofle underðēodde.” Eft hē āxode hū ðǣre ðēode nama wǣre, þe hī of comon. Him wæs ȝeandwyrd þæt hī Angle ȝenemnode wǣron. Þā cwæð hē: “rihtlīċe hī sind Angle ȝehātene, for ðan ðe hī engla wlite habbað, and swilcum ȝedafenað þæt hī on heofonum engla ȝefēran bēon.” Gȳt ðā Grēgōrius befrān, hū ðǣre scīre nama wǣre, þe ðā cnapan of ālǣdde wæron. Him man sǣde þæt ðā scīrmen wǣron Dēre ȝehātene. Grēgōrius andwyrde: “Wel hī sind Dēre ȝehātene. for ðan ðe hī sind fram graman ȝenerode, and tō cristes mildheortnysse ȝecȳȝede.” Gȳt ðā hē befrān: “Hū is ðǣre leode cyning ȝehāten?” Him wæs ȝeandswarod þæt se cyning Ælle ȝehāten wǣre. Hwæt, ðā Grēgōrius gamenode mid his wordum to ðām naman, and cwæð: “Hit ȝedafenað þæt alleluia sȳ ȝesungen on ðām lande. tō lofe þæs ælmihtigan scyppendes.”

Grēgōrius ðā sōna ēode tō ðām pāpan þæs apostolican setles, and hine bæd þæt hē Angelcynne sume lārēowas āsende, ðe hī to criste ȝebiȝdon, and cwæð þæt hē sylf ȝearo wǣre þæt weorc tō ȝefremmenne mid godes fultume, ȝif hit ðām pāpan swā ȝelīcode. Þā ne mihte sē pāpa þæt ȝeðafian, þeah ðe hē eall wolde, for ðan ðe ðā rōmāniscan ċeasterȝewaran noldon ȝeðafian þæt swā ȝetoȝen mann and swā ȝeðungen lārēow þā burh eallunge forlēte, and swā fyrlen wræcsīð ȝename.

Then perceived the pope who at that time sat on the apostolic seat, how the blessed Gregory was thriving in the holy troops, and he then picked him up from the monastic condition, and made him (his) helper, (being) ordained to deaconhood. Then it happened at one time (= one day), as it yet very often does, that English merchants brought their wares to the city of Rome, and Gregory went along the street to the English men, looking at their things. Then he saw, among the wares, slaves set. They were men of white body and fair face, and excellently haired.

Gregory then beheld the appearance of those boys, and asked from which country they were brought. Then he was told that they were from England, and that the people of that country were so beautiful. Then again Gregory asked whether the fold of the land was Christian or heathen. They told him that they were heathen. Gregory then drew a long sigh from the depth of (his) heart, and said, 'Alas! that men of so fair appearance are subject to the black devil.' Again he asked how the name of the nation was, where they came from. He was answered that they were named Angles. Then said he, 'rightly they are called Angles, because they have angels' appearance, and it befits such (people) that they should be angels' companions in heavens!' Still Gregory asked how the name of the shire was, from which they were led away. They told him that the shiremen were called Deirians. Gregory answered, 'They are well called Deirians, because they are delivered from ire, and invoked to Christ's mercy.' Still he asked 'How is the king of the people called?' He was answered that the king was called Ælle. What! then Gregory joked with his words to the name, and said, 'It is fitting that Halleluiah be sung in the land, in praise of the Almighty Creator.'

Then Gregory at once went to the pope of the apostolic seat, and entreated him that he should send some preachers to the English, whom they converted to Christ, and said that he himself was ready to perform the work with God's help, if it so pleased the pope. The pope could not permit it, even if he quite desired (it), because the Roman citizens would not consent that such an educated and competent scholar should leave the city completely and take such a distant journey of peril.

なお,この逸話の主人公は後の Gregory I だが,テキスト中で示されている pāpa は当時の Pelagius II を指している.この後,さすがに Gregory が自らイングランドに布教に出かけるというわけにはいかなかったので,後に Augustinus (St Augustine) を送り込んだというわけだ.

この逸話を受けて,渡部とミルワード (50--51) は,英国のキリスト教はダジャレで始まったようなものだと評している.

渡部 若いときにグレゴリーがローマで非常に肌の白い,金髪の奴隷を見ました.で,その奴隷に「おまえはどこから来たのか」ときいたら,「アングル (Angle)」人と答えた.そこでグレゴリーは「おまえはアングル人じゃなくてエンジェル (angel) のようだ」といったというような有名な話があります.

ミルワード そう,有名なシャレです.ですから,ある意味でイギリスのキリスト教史は言葉のシャレから始まると言うことができます.--- Non angli, sed angeli, --- Not Angles, but angels.

渡部 そして,「おまえの国は?」と聞いたら「デイラ (Deira) です」とその奴隷は答えた.すると「〔神の〕怒から (de ira) 救われて,キリストの慈悲に招かれるであろう」とグレゴリーは言ってやった.それから「おまえの王様の名は何か」と聞いたら「エルラ (Ælla) です」と奴隷は答えた.するとグレゴリーはそれをアレルヤとかけて「エルラの国でもアルレルリア (Allelulia) と,神をたたえる言葉が唱えられるようにしよう」と言った有名な話がありますね.本当にジョークで始まったんですね,イギリスの布教は.

(後記 2024/04/13(Sat):Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」にて,この1節の "Eft hē āxode . . . ȝefēran bēon." の部分について古英語音読していますのでご参照ください.「#1048. コアリスナーさんたちと古英語音読」です.)

(後記 2024/06/12(Wed):上記 Voicy で読み上げた部分の写本画像へのリンクです:Catholic Homilies, Second Series, "IX, St Gregory the Great" (MS Ii.1.33, fol. 140v) *

・ 市河 三喜,松浪 有 『古英語・中英語初歩』 研究社,1986年.

・ 渡部 昇一,ピーター・ミルワード 『物語英文学史――ベオウルフからバージニア・ウルフまで』 大修館,1981年.

2017-04-05 Wed

■ #2900. 449年,アングロサクソン人によるブリテン島侵略 [bede][oe][literature][popular_passage][history][anglo-saxon][oe_text][kochushoho]

Bede の古英語訳により,英語史上記念すべき449年の記述 ("The Coming of the English") を市川・松浪編の古英語テキスト(現代英語訳付き)で読んでみよう (pp. 89--94) .アングロサクソン人は,ブリトン人に誘われた機会に乗じて,いかにしてブリテン島に居座るに至ったのか.

Ðā wæs ymb fēower hund wintra and nigon and fēowertiġ fram ūres Drihtnes menniscnysse þæt Martiānus cāsere rīċe onfēng and vii ġēar hæfde. Sē wæs syxta ēac fēowertigum fram Augusto þām cāsere. Ðā Angelþēod and Seaxna wæs ġelaðod fram þām foresprecenan cyninge, and on Breotone cōm on þrim miċlum scipum, and on ēastdæle þyses ēalondes eardungstōwe onfēng þurh ðæs ylcan cyninges bebode, þe hī hider ġelaðode, þæt hī sceoldan for heora ēðle compian and fohtan. And hī sōna compedon wið heora ġewinnan, þe hī oft ǣr norðan onherġedon; and Seaxan þā siġe e ġeslōgan. Þā sendan hī hām ǣrendracan and hēton secgan þysses landes wæstmbǣrnysse and Brytta yrgþo. And hī sōna hider sendon māran sciphere strengran wiġena; and wæs unoferswīðendliċ weorud,þā hī tōgædere ġeþēodde wǣron. And him Bryttas sealdan and ġēafan eardungstōwe betwih him, þæt hī for sibbe and for hǣlo heora ēðles campodon and wunnon wið heora fēondum, and hī him andlyfne and āre forġēafen for heora ġewinne.

Cōmon hī of þrim folcum ðām strangestan Germānie, þæt is of Seaxum and of Angle and of Ġēatum. Of Ġēata fruman syndon Cantware and Wihtsǣtan; þæt is se þēod þe Wiht þæt ēalond oneardað. Of Seaxum, þæt is of ðām lande þe mon hāteð Ealdseaxan, cōmon Ēastseaxan and Sūðseaxan and Westseaxan. And of Engle cōman Ēastngle and Middelengle and Myrċe and eall Norðhembra cynn; is þæt land ðe Angulus is nemned, betwyh Ġēatum and Seaxum; and is sǣd of ðǣre tīde þe hī ðanon ġewiton oð tōdæġe þæt hit wēste wuniġe. Wǣron ǣrest heora lāttēowas and heretogan twēġen ġebrōðra, Henġest and Horsa. Hī wǣron Wihtgylses suna, þæs fæder wæs Witta hāten, þæs fæder wæs Wihta hāten, þæs fæder wæs Woden nemned, of ðæs strȳnde moniġra mǣġðra cyningcynn fruman lǣdde. Ne wæs ðā ylding tō þon þæt hī hēapmǣlum cōmon māran weorod of þām þēodum þe wǣ ǣr ġemynegodon. And þæt folc ðe hider cōm ongan weaxan and myċlian tō þan swīðe þæt hī wǣron on myclum eġe þām sylfan landbīġengan ðe hī ǣr hider laðedon and cȳġdon.

It was 449 years after our Lord's incarnation that the emperor Martianus received the kingdom, and he had (it) seven years. He was the forty-sixth from the emperor Augustus. Then the Angles and Saxons were invited by the aforesaid king (Vortigern), and came to Britain on three great ships, and received a dwelling place in the east of this island by order of the same king, who invited them hither, that they should strive and fight for their country. And they soon fought with their enemies who had oft harassed them from the north before; and the Saxons won victory then. Then they sent home messengers and bade (them) tell the fertility of this land and the Britons' cowardice. And then they sent a larger fleet of the stronger friends soon; and (it) was an invincible troop when there were united together. And the Britons gave and alloted them habitation among themselves, on the condition that they should fight for the peace and safety of their country and resist their enemies, and they (the Britons) should give them sustenance and estates in return for their strife.

They came of the three strongest races of Germany, that is, of Saxons and of Angles and of Jutes. Of Jutes' origin are the people of Kent and the 'Wihtsætan', that is, the people who inhabit the Isle of Wight. Of the Saxons, of the land (of the people) that is called Old Saxons, came the East Saxons, the South Saxons, and the West Saxons. And of Angles came the East Angles and the Middle Angles and Mercians and the whole race of Northumbria; it is the land that is called Angulus, between the Jutes and the Saxons; and it is said from the time when they departed thence till today that it remains waste. At first their leaders and commanders were two brothers, Hengest and Horsa. They were the sons of Wihtgyls, whose father was called Witta, whose father was named Wihta, whose father was named Woden, of whose stock the royal families of many tribes took their origin. There was no delay until they came in crowds, larger hosts from the tribes that we had mentioned before. And the people who came hither began to increase and multiply so much that they were a great terror to the inhabitants themselves who had invited and invoked them hither.

・ 市河 三喜,松浪 有 『古英語・中英語初歩』 研究社,1986年.

2017-04-03 Mon

■ #2898. Caedmon's Hymn [oe][popular_passage][literature][bede][oe_text][caedmon]

731年に完成したとされる Bede の Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (= Ecclesiastical History of the English People) は,アルフレッド大王の時代にマーシアの学者によって古英語に訳されている.そこには文盲の牛飼い Cædmon が霊感を得て作成したとされる,9行からなる現存する最古の古英詩 Cædmon's Hymn が収録されているが,そのテキストについては,さらに早い8世紀初頭の Bede のラテン語写本 (MS Kk. v. 16, Cambridge University Library; 通称 "Moore Manuscript") の中に,ノーサンブリア方言で書かれたバージョンも残されている.まず,オリジナルに最も近いと言われる Moore バージョンのテキストおよび現代英語訳を Irvine (37) より再掲しよう.

Nu scylun hergan hefænricæs uard,

metudæs mæcti end his modgidanc,

uerc uuldurfadur, sue he uundra gihuæs,

eci dryctin, or astelidæ.

He ærist scop aelda barnum

heben til hrofe, haleg scepen;

tha middungeard moncynnæs uard,

eci dryctin, æfter tiadæ

firum foldu, frea allmectig.

Now [we] must praise the Guardian of the heavenly kingdom, the Creator's might and His intention, the glorious Father's work, just as He, eternal Lord, established the beginning of every wonder. He, holy Creator, first shaped heaven as a roof for the children of men, then He, Guardian of mankind, eternal Lord, almighty Ruler, afterwards fashioned the world, the earth, for men.

次に,アルフレッド時代のものを Mitchell (212) より引用する.両テキスト間の綴字,音韻,形態,語彙の差に注意したい.

Nū sculon heriġean heofonrīċes weard,

Meotodes meahte ond his mōdġeþanc,

weorc wuldorfæder, swā hē wundra ġehwæs,

ēċe Drihten, ōr onstealde.

Hē ǣrest scēop eorðan bearnum

heofon tō hrōfe, hāliȝ Scyppend;

þā middanġeard monncynnes weard,

ēċe Drihten, æfter tēode

fīrum foldan, Frēa ælmihtiġ.

・ Irvine, Susan. "Beginnings and Transitions: Old English." Chapter 2 of The Oxford History of English. Ed. Lynda Mugglestone .Oxford: OUP, 2006.

・ Mitchell, Bruce. An Invitation to Old English and Anglo-Saxon England. Blackwell: Malden, MA, 1995.

2017-03-31 Fri

■ #2895. 古英語聖書より「岩の上に家を建てる」 [oe][popular_passage][bible][literature][oe_text][hel_education][voicy]

古英語訳の聖書は,古英語読解のための初級者向け教材として有用である.近代英語の欽定訳聖書 (The Authorized Version) や現代英語版はもちろん,日本語を含むありとあらゆる言語への訳も出されており,比較・参照できるからだ.

以下,新約聖書より Matthew 7: 24--27 の「岩の上に家を建てる」寓話について,古英語版テキストを MS Corpus Christi College Cambridge 140 より示そう (Mitchell 60) .合わせて,対応する近代英語テキストを欽定訳聖書より引用する.

Ǣlċ þāra þe ðās mīne word ġehȳrþ and þā wyrcþ byþ ġelīċ þǣm wīsan were se hys hūs ofer stān ġetimbrode.

Þā cōm þǣr reġen and myċel flōd and þǣr blēowon windas and āhruron on þæt hūs and hyt nā ne fēoll・ sōþlīċe hit wæs ofer stān ġetimbrod.

And ǣlċ þāra þe ġehȳrþ ðās mīne word and þā ne wyrcþ・ sē byþ ġelīċ þǣm dysigan menn þe ġetimbrode hys hūs ofer sand-ċeosel.

Þā rīnde hit and þǣr cōmon flōd and blēowon windas and āhruron on þæt hūs and þæt hūs fēoll・ and hys hryre wæs miċel

Therefore whosoever heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them, I will liken him unto a wise man, which built his house upon a rock:

And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell not: for it was founded upon a rock.

And every one that heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them not, shall be likened unto a foolish man, which built his house upon the sand:

And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell: and great was the fall of it.

聖書に関する古英語テキストについては,「#1803. Lord's Prayer」 ([2014-04-04-1]),「#1870. 「創世記」2:18--25 を7ヴァージョンで読み比べ」 ([2014-06-10-1]) も参照されたい.

(後記 2022/05/03(Tue):Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」にて,この1節を古英語の発音で読み上げていますのでご参照ください.「古英語をちょっとだけ音読 マタイ伝「岩の上に家を建てる」寓話より」です.)

・ Mitchell, Bruce. An Invitation to Old English and Anglo-Saxon England. Blackwell: Malden, MA, 1995.

2017-03-30 Thu

■ #2894. 793年,ヴァイキングによるリンディスファーン島襲撃 [anglo-saxon_chronicle][popular_passage][oe][history][literature][oe_text]

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle は,アルフレッド大王の命により890年頃に編纂が開始された年代記である.古英語で書かれており,9写本が現存している.最も長く続いたものは通称 Peterborough Chronicle と呼ばれもので,1154年までの記録が残っている.以下の抜粋は,Worcester Chronicle と呼ばれるバージョンの793年の記録である(Crystal 19 より現代英語訳も合わせて引用).数年前からイングランドに出没し始めたヴァイキングが,この年に,ノーサンブリアのリンディスファーン島を襲った.イングランド人の怯える様が,印象的に記されている.最後に言及されている Sicga なる人物は,788年にノーサンブリア王 Ǣlfwald を殺した悪名高い貴族である.

Ann. dccxciii. Her ƿæron reðe forebecna cumene ofer noðhymbra land . 7 þæt folc earmlic breȝdon þæt ƿæron ormete þodenas 7 liȜrescas . 7 fyrenne dracan ƿæron ȝeseƿene on þam lifte fleoȝende. þam tacnum sona fyliȝde mycel hunȝer . 7 litel æfter þam þæs ilcan ȝeares . on . vi. id. ianr . earmlice hæþenra manna herȝunc adileȝode ȝodes cyrican in lindisfarna ee . þurh hreaflac 7 mansliht . 7 Sicȝa forðferde . on . viii . kl. martius.

Year 793. Here were dreadful forewarnings come over the land of Northumbria, and woefully terrified the people: these were amazing sheets of lightning and whirlwinds, and fiery dragons were seen flying in the sky. A great famine soon followed these signs, and shortly after in the same year, on the sixth day before the ides of January, the woeful inroads of heathen men destroyed god's church in Lindisfarne island by fierce robbery and slaughter. And Sicga died on the eighth day before the calends of March.

歴史上,この793年の事件は,イングランドにおける本格的なヴァイキングの侵攻の開始を告げる画期的な出来事である.

・ Crystal, David. Evolving English: One Language, Many Voices. London: The British Library, 2010.

2017-03-29 Wed

■ #2893. Beowulf の冒頭11行 [beowulf][link][oe][literature][popular_passage][oe_text][hel_education]

Beowulf は,古英語で書かれた最も長い叙事詩(3182行)であり,アングロサクソン時代から現存する最も重要な文学作品である.スカンディナヴィアの英雄 Beowulf はデンマークで怪物 Grendel を殺し,続けてその母をも殺した.Beowulf は後にスウェーデン南部で Geat 族の王となるが,年老いてから竜と戦い,戦死する.

この叙事詩は,古英語で scop と呼ばれた宮廷吟遊詩人により,ハープの演奏とともに吟じられたとされる.現存する唯一の写本(1731年の火事で損傷している)は1000年頃のものであり,2人の写字生の手になる.作者は不詳であり,いつ制作されたかについても確かなことは分かっていない.8世紀に成立したという説もあれば,11世紀という説もある.

冒頭の11行を Crystal (18) より,現代英語の対訳付きで以下に再現しよう.

1 HǷÆT ǷE GARDEna in ȝeardaȝum . Lo! we spear-Danes in days of old 2 þeodcyninȝa þrym ȝefrunon heard the glory of the tribal kings, 3 hu ða æþelinȝas ellen fremedon . how the princes did courageous deeds. 4 oft scyld scefing sceaþena þreatum Often Scyld Scefing from bands of enemies 5 monegū mæȝþum meodo setla ofteah from many tribes took away mead-benches, 6 eȝsode eorl[as] syððan ærest ƿearð terrified earl[s], since first he was 7 feasceaft funden he þæs frofre ȝebad found destitute. He met with comfort for that, 8 ƿeox under ƿolcum, ƿeorðmyndum þah, grew under the heavens, throve in honours 9 oðþ[æt] him æȝhƿylc þara ymbsittendra until each of the neighbours to him 10 ofer hronrade hyran scolde over the whale-road had to obey him, 11 ȝomban ȝyldan þ[æt] ƿæs ȝod cyninȝ. pay him tribute. That was a good king!

冒頭部分を含む写本画像 (Cotton MS Vitellius A XV, fol. 132r) は,こちらから閲覧できる.その他,以下のサイトも参照.

・ Cotton MS Vitellius A XV, Augustine of Hippo, Soliloquia; Marvels of the East; Beowulf; Judith, etc.: 写本画像を閲覧可能.

・ Beowulf: BL による物語と写本の解説.

・ Beowulf Readings: 古英語原文と「読み上げ」へのアクセスあり.

・ Beowulf Translation: 現代英語訳.

・ Diacritically-Marked Text of Beowulf facing a New Translation (with explanatory notes): 古英語原文と現代英語の対訳のパラレルテキスト.

・ Crystal, David. Evolving English: One Language, Many Voices. London: The British Library, 2010.

2017-03-16 Thu

■ #2880. AElfwine's Prayerbook より月齢と潮差について [oe][calendar]

原始より,人類は天体や自然を観察し,暦を作り上げてきた.特に身近な観察対象に,月と潮がある.1日の潮の干満の差(潮差)は半月周期で変化を繰り返し,朔望(陰暦1日と15日)のころ最大(大潮)となり,上下弦のころ最小(小潮)となる.

古英語テキストにも,月齢と潮差による暦の記述が見られる.Winchester の New Minster の修道院長 Ælfwine が,私的な祈祷書の写本をもっていた(現在では London, British Library, Cotton Titus D. xxvi--xxvii として2つの写本に分かれている).この写本が編まれたのは,1023--31年の間とされ,関与している2人の写字生のうち,1人は Ælfwine その人とされる.この写本には78のテキストが収められているが,過半数は信仰文・祈祷文である.ほとんどがラテン語で書かれているが,10のテキストについては古英語で書かれている.

古英語で書かれた世俗的なテキストの1つに「月の満ち欠けと潮の満ち引き」に関するものがある.以下,Marsden (15--16) の版より引用しよう.千年前の地学の教科書を読んでいるかのようだ.

Hēr is sēo endebyrdnes mōnan gonges ond sǣflōdes. On þrēora nihta ealdne mōnan, wanað se sǣflōd oþþæt se mōna bið XI nihta eald oþþe XII. Of XI nihta ealdum mōnan, weaxeð se sǣflōd oþ XVIII nihta ealdum mōnan. Fram XVIII nihta ealdum mōnan, wanaþ se sǣflōd oþ XXVI nihta ealdum mōnan. Of XXVI nihta ealdum mōnan, weaxeð se sǣflōd oþþæt se mōna bið eft ðrēora nihta eald

・ Marsden, Richard, ed. The Cambridge Old English Reader. Cambridge: CUP, 2004.

2017-03-07 Tue

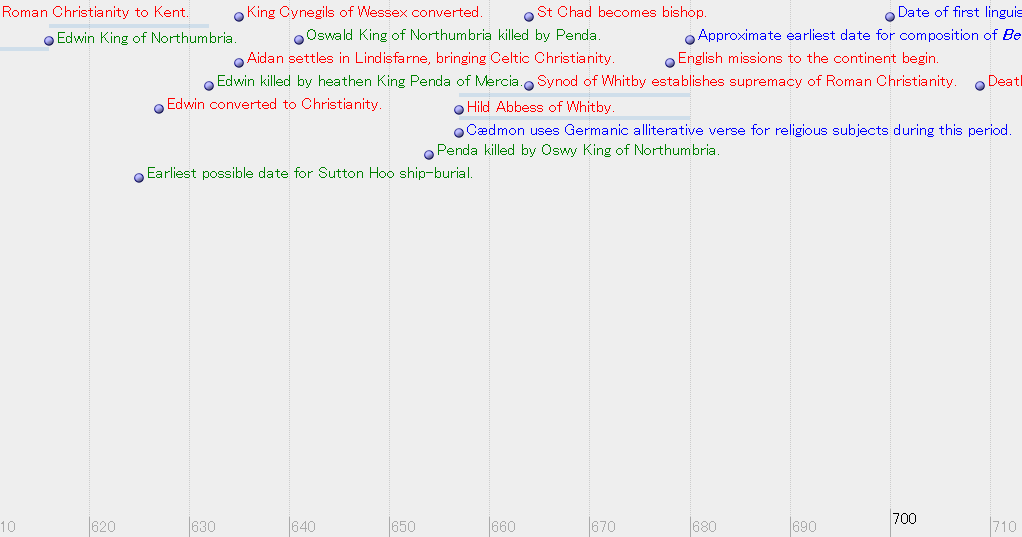

■ #2871. 古英語期のスライド年表 [timeline][web_service][oe][anglo-saxon]

「#2358. スライドできる英語史年表」 ([2015-10-11-1]) にならい,Mitchell (361--64) の古英語期の年表をスライド化してみました.以下の画像をクリックしてご覧ください.スライド年表では,出来事のジャンル別に Lay = 緑,Religious = 赤,Literary = 青で色分けしています.

以下は,スライド年表のベースとした通常の表形式の年表です.参考までに.

| Date | Lay | Religious | Literary |

| 449 | Traditional date of coming of Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. | The legend of Arthur may rest on a British leader who resisted the invaders. | |

| c. 547 | Gildas writes De excidio Britanniæ. | ||

| 560--616 | Æthelbert King of Kent. | ||

| c. 563 | St Columba brings Celtic Christianity to Iona. | ||

| 597 | St Augustine brings Roman Christianity to Kent. | ||

| 616--632 | Edwin King of Northumbria. | ||

| c. 625 | Earliest possible date for Sutton Hoo ship-burial. | ||

| 627 | Edwin converted to Christianity. | ||

| 632 | Edwin killed by heathen King Penda of Mercia. | ||

| 635 | Aidan settles in Lindisfarne, bringing Celtic Christianity. | ||

| 635 | King Cynegils of Wessex converted. | ||

| 641 | Oswald King of Northumbria killed by Penda. | ||

| 654 | Penda killed by Oswy King of Northumbria. | ||

| 664 | Synod of Whitby establishes supremacy of Roman Christianity. | ||

| 664 | St Chad becomes bishop. | ||

| 657--680 | Hild Abbess of Whitby. | Cædmon uses Germanic alliterative verse for religious subjects during this period. | |

| c. 678 | English missions to the continent begin. | ||

| 680 | Approximate earliest date for composition of Beowulf. | ||

| c. 700 | Date of first linguistic records. | ||

| 709 | Death of Aldhelm, Bishop of Sherborne. | ||

| 731 | Bede completes Historia gentis Anglorum ecclesiastica. | ||

| 735 | Death of Bede. | ||

| c. 735 | Birth of Alcuin. | ||

| 757--796 | Offa King of Mercia. | ||

| 782 | Alcuin settles at Charlemagne's court. | ||

| 793 | Viking raids begin. | Sacking of Lindisfarne. | |

| fl. 796 | Nennius, author or reviser of Historia Britonum. | ||

| 800 | Four great kingdoms remain --- Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Wessex. | ||

| 780--850 | Cynewulf probably flourishes some time in this period. | ||

| 804 | Death of Alcuin. | ||

| 851 | Danes' first winter in England. | ||

| 865 | Great Danish Army lands in East Anglia. | ||

| 867 | Battle of York. End of Northumbria as a political power. | ||

| 870 | King Edmund of East Anglia killed by Danes. East Anglia overrun. | ||

| 871 | Alfred becomes King of Wessex. | ||

| 874 | Danes settle in Yorkshire. | ||

| 877 | Danes settle in East Mercia. | ||

| 880 | Guthrum and his men settle in East Anglia. Only Wessex remains of the four Kingdoms. | ||

| ?886 | Boundaries of Danelaw agreed with Guthrum. Alfred occupies London. | The period of the Alfredian translations and the beginning of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. | |

| 892 | Further Danish invasion. | ||

| 896 | Alfred builds a fleet. | ||

| 899 | Death of King Alfred. | ||

| 899--954 | The creation of the English Kingdom. | ||

| c. 909 | Birth of Dunstan. | ||

| 937 | Battle of Brunanburh. | Poem commemorates the battle. | |

| 954 | The extinction of the Scandinavian kingdom of York. | ||

| 959--975 | Edgar reigns. | ||

| 960 | Dunstan Archbishop of Canterbury. The period of the Monastic Revival. | ||

| c. 971 | The Blickling Homilies. | ||

| 978 or 979 | Murder of King Edward. | ||

| 950--1000 | Approximate dates of the poetry codices --- Junius MS, Vercelli Book, Exeter Book, and Beowulf MS. | ||

| 978--1016 | Ethelred reigns. | ||

| 988 | Death of Dunstan. | ||

| 991 | Battle of Maldon. | Poem commemorates the battle. | |

| 990--992 | Ælfric's Catholic Homilies. | ||

| 993--998 | Ælfric's Lives of the Saints. | ||

| 1003--1023 | Wulfstan Archbishop of York. | ||

| c. 1014 | Sermo Lupi ad Anglos. | ||

| 1005--c. 1012 | Ælfric Abbot of Eynsham. | ||

| 1013 | Sweyn acknowledged as King of England. | ||

| 1014 | Sweyn dies. | ||

| 1016 | Edmund Ironside dies. | ||

| 1016--1042 | Canute and his sons reign. | ||

| 1042--1066 | Edward the Confessor. | ||

| 1066 | Harold King. Battle of Stamford Bridge. Battle of Hastings. William I king. |

・ Mitchell, Bruce. An Invitation to Old English and Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell, 1995.

2017-03-05 Sun

■ #2869. 古ノルド語からの借用は古英語期であっても,その文証は中英語期 [old_norse][loan_word][borrowing][oe][eme]

ある言語の話者が別の言語から語を借用するという行為と,その語を常用するという慣習とは,別物である.前者はまさに「借りる」という行為が行なわれているという意味で動的な borrowing の話題であり,後者はそれが語彙体系に納まった後の静的な loan_word 使用の話題である.この2者の違いを証拠 (evidence) という観点から述べれば,文献上,前者の "borrowing" の過程は確認されることはほとんどあり得ず,後者の "loan word" 使用としての状況のみが反映されることになる.

この違いを,英語史の古ノルド語の借用(語)において考えてみよう.英語が古ノルド語の語彙を借用した時期は,両言語が接触した時期であるから,その中心は後期古英語期である.場所によっては多少なりとも初期中英語期まで入り込んでいたとしても,基本は後期古英語期であることは間違いない(「#2591. 古ノルド語はいつまでイングランドで使われていたか」 ([2016-05-31-1])).

しかし,借用という行為が後期古英語期の出来事であったとしても,そのように借用された借用語が,その時期の作とされる写本などの文献に同時代的に反映されているかどうかは別問題である.通常,借用語は社会的にある程度広く認知されるようになってから書き言葉に書き落とされるものであり,借用がなされた時期と借用語が初めて文証される時期の間にはギャップがある.とりわけ現存する後期古英語の文献のほとんどは,地理的に古ノルド語の影響が最も感じられにくい West-Saxon 方言(当時の標準的な英語)で書かれているため,古ノルド語からの借用語の証拠をほとんど示さない.一方,古ノルド語の影響が濃かったイングランド北部や東部の方言は,非標準的な方言として,もとより書き記される機会がなかったので,証拠となり得る文献そのものが残っていない.さらに,ノルマン征服以降,英語は,どの方言であれ,文献上に書き落とされる機会そのものを激減させたため,初期中英語期においてすら古ノルド語からの借用語の使用が確認できる文献資料は必ずしも多くない.したがって,多くの古ノルド語借用語が文献上に動かぬ証拠として確認されるのは,早くても初期中英語,遅ければ後期中英語以降ということになる.古ノルド語の借用(語)を論じる際に,この点はとても重要なので,銘記しておきたい.

Crowley (101) に,この点について端的に説明している箇所があるので,引いておこう.

[T]he Scandinavian influence on English dialects, which began after c. 850 and outside the tradition of writing, does not show up in any significant way in the records of Old English. The substantial pre-1066 texts from the Danelaw areas show either the local Old English dialect without Scandinavian influence or standard Late West Saxon. So, despite the circumstantial evidence and Middle English attestation of a significant Scandinavian influence, not much can be made of it for Old English.

・ Crowley, Joseph P. "The Study of Old English Dialects." English Studies 67 (1986): 97--104.

2016-12-07 Wed

■ #2781. 宗教改革と古英語研究 [reformation][emode][oe][history_of_linguistics][anglo-saxon]

イングランドにおいて本格的な古英語研究が始まったのは,近代に入ってからである.中英語期には,古英語への関心はほとんどなかったといってよい.では,なぜ近代というタイミングで,具体的には16世紀になってから,古英語が突如として研究すべき対象となったのだろうか.

16世紀は宗教改革の時代である.Henry VIII がローマ教会と絶縁し,自ら英国国教会を設立したのが,1534年.このとき改革派は,英国国教会とその教義の独自性および歴史的継続性を主張する必要があった.そこで持ち出されたのが,言語的伝統,すなわち英語の歴史であった.イングランドという国家と分かち難く結びつけられた英語という言語の伝統が,長きにわたり独自のものであり続けたことを喧伝するのが,改革派にとっては得策と考えられた.また,英語の伝統を遡るという営為は,王権神授説に対抗し,実際的にイングランドの法律や政治的慣行の起源を探るという当時の欲求に適うものでもあった.

古英語文献が印刷に付された最初のものは,Ælfric による復活祭説教集で,1566--67年に A Testimonie of Antiquity として世に出た.それから1世紀の時間をおいて,1659年には William Somner による初の古英語辞書 Dictionarium Saxonico-Latino-Anglicum が出版される.最初の古英語文法も,George Hickes によって1689年に出版されている.そして,1755年にはオックスフォード大学で最初の "Anglo-Saxon" 学の教授職が Richard Rawlinson により設定された(英語史上の1段階としての変種を表わすのに "Old English" ではなく "Anglo-Saxon" という用語が用いられてきたことについては,「#234. 英語史の時代区分の歴史 (3)」 ([2009-12-17-1]),「#236. 英語史の時代区分の歴史 (5)」 ([2009-12-19-1]) を参照).

このように,16--18世紀にかけて古英語研究が勃興ししてきた背景には,純粋に学問的な好奇心というよりは,宗教改革に端を発するすぐれて政治的な思惑があったのである.この経緯について,簡潔には Baugh and Cable (280fn) を,詳しくは武内の「第8章 イングランドのアングロ・サクソン学事始」を参照.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

・ 武内 信一 『英語文化史を知るための15章』 研究社,2009年.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow