2023-08-20 Sun

■ #5228. 古英語の人名の愛称には2重子音が目立つ [oe][anglo-saxon][onomastics][name_project][personal_name][consonant][phonetics][shortening][hypocorism][germanic][sound_symbolism]

古英語の人名の愛称 (hypocorism) の特徴は何か,という好奇心をくするぐる問いに対して,Clark (459--60) が先行研究を参考にしつつ,おもしろいヒントを与えてくれている.主に音形に関する指摘だが,重子音 (geminate) が目立つのだという.

Clearly documented hypocoristics often show modified consonant-patterns . . . . Thus, the familiar form Saba (variant: Sæba) by which the sons of the early-seventh-century King Sǣbeorht (Saberctus) of Essex called their father showed the first element of the full name extended by the initial consonant of the second, in a way perhaps implying that medial consonants following a stressed syllable may have been ambisyllabic . . . . In the Germanic languages generally, a consonant-cluster formed at the element-junction of a compound name was often simplified in the hypocoristic form to a geminate, Old English examples including the masc. Totta < Torhthelm, the fem. Cille < Cēolswīð, and also the masc. Beoffa apparently derived from Beornfrið . . . .

重子音化や子音群の単純化といえば,日本語の「さっちゃん」「よっちゃん」「もっくん」「まっさん」等々を想起させる.日本語の音韻論では重子音(促音)そのものの生起が比較的限定されているといってよいが,名前やその愛称などにはとりわけ多く用いられているような印象がある.音象徴 (sound_symbolism) の観点から,何らかの普遍的な説明は可能なのだろうか.

・ Clark, Cecily. "Onomastics." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 1. Ed. Richard M. Hogg. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 452--89.

2023-08-19 Sat

■ #5227. 古英語の名前研究のための原資料 [oe][anglo-saxon][onomastics][evidence][philology][methodology][name_project][domesday_book]

連日の記事「#5225. アングロサクソン人名の構成要素 (2)」 ([2023-08-17-1]),「#5226. アングロサクソン人名の名付けの背景にある2つの動機づけ」 ([2023-08-18-1]) で引用・参照してきた Clark (453) より,そもそも古英語の名前研究 (onomastics) の原資料 (source-materials) にはどのようなものがあるのかを確認しておきたい.

The sources for early name-forms, of people and of places alike, are, in terms of the conventional disciplines, ones more often associated with 'History' than with 'English Studies': they range from chronicles through Latinised administrative records to inscriptions, monumental and other. Not only that: the aims and therefore also the findings of name-study are at least as often oriented towards socio-cultural or politico-economic history as towards linguistics. This all goes to emphasise how artificial the conventional distinctions are between the various fields of study.

Thus, onomastic sources for the OE period include: chronicles, Latin and vernacular; libri vitae; inscriptions and coin-legends; charters, wills, writs and other business-records; and above all Domesday Book. Not only each type of source but each individual piece demands separate evaluation.

伝統的な古英語の文献学的研究とは少々異なる視点が認められ,興味深い.とはいえ,文献学的研究から大きく外れているわけでもない.文献学でも引用内で列挙されている原資料はいずれも重要なものだし,引用の最後にあるように "each individual piece" の価値を探るという点も共通する.ただし,固有名は一般の単語よりも同定が難しいため,余計に慎重を要するという事情はありそうだ.

原資料をめぐる問題については以下の記事を参照.

・ 「#1264. 歴史言語学の限界と,その克服への道」 ([2012-10-12-1])

・ 「#2865. 生き残りやすい言語証拠,消えやすい言語証拠――化石生成学からのヒント」 ([2017-03-01-1])

・ 「#1051. 英語史研究の対象となる資料 (1)」 ([2012-03-13-1])

・ 「#1052. 英語史研究の対象となる資料 (2)」 ([2012-03-14-1])

・ Clark, Cecily. "Onomastics." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 1. Ed. Richard M. Hogg. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 452--89.

2023-08-18 Fri

■ #5226. アングロサクソン人名の名付けの背景にある2つの動機づけ [name_project][onomastics][personal_name][anglo-saxon][oe][bede][beowulf]

昨日の記事「#5225. アングロサクソン人名の構成要素 (2)」 ([2023-08-17-1]) で,Clark を参照して Bede にみられる古英語人名の傾向を確認した.そこでの人名を構成する "themes" に対応する語彙は,古英詩 Beowulf でもよく用いられている単語群であり,古英語における文化的キーワードを表わすものといえるかもしれない.

一方で,名付けの実際に当たっては,それぞれの themes の意味が,古英語期に共時的に理解されていたかどうかは分からない.当初は名前に込められていた「意味」が形骸化するのはよくあることだし,Beowulf の語彙は詩の語彙であり,古英語当時ですら古風だったことは,よく指摘されきたことである.アングロサクソンの文化的キーワードというよりも文化遺産的キーワードといったほうがよいようにも思われる.

この点について,Clark も慎重な見解を示している (457--58) .

Name themes thus largely parallel the diction of heroic verse . . . . Kindred elements in the diction of Beowulf include common items such as beorht, cēne, cūð, poetic ones such as brego and torht, and also, more strikingly, compounds like frēawine 'lord and friend', gārcēne 'bold with spear', gūðbeorn 'battle-warrior', heaðomǣre 'renowned in battle', hildebill 'battle-blade', wīgsigor 'victorious in battle' . . . . Parallels must not be pressed; for rules of formation differed and, more crucially, such 'meaning' as name-compounds possessed was not in practice etymological. Name-themes might, besides, long out-live related items of daily, even literary, vocabulary: non-onomastic Old English usage shows no cognate of the feminine deuterotheme -flǣd 'beauty' and, as cognates of Tond- 'fire', only the mutated derivatives ontendan 'kindle' and tynder 'kindling wood'. Resemblances between naming and heroic diction nonetheless suggest motivations behind the original Germanic styles: hopes and wishes appropriate to a warrior society, and perhaps belief in onomastic magic . . . .

引用の最後にあるように,Clark はアングロサクソン人名の名付けの背景にある2つの動機づけとして (1) 戦士社会にふさわしい望みと願い,(2) 名前の魔法への信仰,を挙げている.アングロサクソン特有という見方もできるが,一歩引いて見ればある意味で名付けの普遍的動機づけともとらえられそうだ.

上で少し触れた名前における「意味」をめぐる問題については,以下も参照.

・ hellog 「#2212. 固有名詞はシニフィエなきシニフィアンである」 ([2015-05-18-1])

・ hellog 「#5197. 固有名に意味はあるのか,ないのか?」 ([2023-07-20-1])

・ heldio 「#665. 固有名詞には指示対象はあるけれども意味はないですよネ」(2023年3月27日)

・ Clark, Cecily. "Onomastics." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 1. Ed. Richard M. Hogg. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 452--89.

2023-08-17 Thu

■ #5225. アングロサクソン人名の構成要素 (2) [name_project][onomastics][personal_name][anglo-saxon][oe][bede]

「#4539. アングロサクソン人名の構成要素」 ([2021-09-30-1]) に引き続き,古英語の人名について Clark による記述をみてみたい.

Clark は,Bede による Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (= Ecclesiastical History of the English People) に現われる215の人名(主に貴人の人名)について種類や数字を挙げている.2/3ほどの人名が2つの要素(第1要素,第2要素をそれぞれ "prototheme","deuterotheme" と呼ぶ)の組み合わせからなっており,その "themes" (あるいは "name lemmas" と呼んでもよいか)の種類を数え上げると,85--90ほどが区別される(識別しにくいものもあるという).うち50種類以上はもっぱら第1要素として,20種類はもっぱら第2要素として用いられており,第1要素にも第2要素にも用いられているものが12種類ある.古英語人名についての一般論として,第1要素に用いられる themes のほうが多様だという.

古英語の人名の themes は,通常の名詞・形容詞としても用いられるありふれた語であることが特徴である.つまり,現代の John や Mary のように人名に特化した語を用いていたわけではない.Bede に現われる90種類ほどの themes についていえば,70種類以上が西ゲルマン語的な要素であり,その2/3ほどが北ゲルマン語にもみられる要素である.ゲルマン語の系統を色濃く受け継いだ themes ということだ.

コーパスを Bede に限っても,人名を眺めてみると,そこに繰り返し現われる概念が顕著になってくる.Clark (457) より列挙する.

Recurrent concepts and typical Bedan name-themes include: nobility and renown --- Æðel- 'noble', Beorht-/-beorht 'radiant', Brego- 'prince', Cūð- 'renowned', Cyne- 'royal', -frēa 'lord', -mǣr 'renowned', Torht- 'radiant'; national pride --- Peoht- 'Pict', Swǣf- 'Swabian', Þēod- 'nation', Wealh-/-wealh 'Celt' and probably Seax- if meaning 'Saxon'; religion --- ælf- 'supernatural being', Ealh- 'temple', Ōs- 'deity'; strength and valour --- Beald-/-beald 'brave', Cēn- 'brave', Hwæt- 'brave', Nōð- 'boldness', Swīð-/-swīð fem. 'strong', Þrȳð-/-þrȳð fem. 'power', Weald-/-weald 'power'; warriors and weapons --- Beorn- 'warrior', -bill 'sword', -brord 'spear', Dryht- 'army', Ecg- 'sword', -gār 'spear', Here-/-here 'army', Wulf-/-wulf 'wolf; warrior', and perhaps Swax- if meaning 'dagger'; battle --- Beadu-, Gūð-/-gūð fem., Heaðu-, Hild-/-hild fem., Wīg-, and also Sige- 'victory' (limitations of function apply only to the Bedan evidence). Peace (-frið), prudence (Rǣd-/-rǣd 'counsel'), and defence (Bōt- 'remedy', Burg-/-burg fem. 'protection', -helm 'protection' and -mund 'protection') are more sparingly invoked. In compound names, protothemes appear in stem-form. Inflections are added only to the deuterothemes; when not Latinised, masc. names follow the a-stems and fem. ones the ō-stems.

関連して以下の記事も参照.

・ 「#4539. アングロサクソン人名の構成要素」 ([2021-09-30-1])

・ 「#3902. 純アングロサクソン名の Edward, Edgar, Edmond, Edwin」 ([2020-01-02-1])

・ 「#3903. ゲルマン名の atheling, edelweiss, Heidi, Alice」 ([2020-01-03-1])

・ 「#5195. 名前レンマ (name lemma)」 ([2023-07-18-1])

・ Clark, Cecily. "Onomastics." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 1. Ed. Richard M. Hogg. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 452--89.

2023-08-08 Tue

■ #5216. Beowulf について専門家にアレコレ尋ねてみました [beowulf][oe][literature][voicy][heldio][manuscript][rhetoric]

先日の hellog 「#5206. Beowulf の冒頭11行を音読」 ([2023-07-29-1]) や Voicy heldio 「#783. 古英詩の傑作『ベオウルフ』 (Beowulf) --- 唐澤一友さん,和田忍さん,小河舜さんと飲みながらご紹介」を通じて,古英語で書かれた代表的な英雄詩 Beowulf に関心をもたれた方もいるかと思います.

前回に引き続き,古英語を専門とする唐澤一友氏(立教大学),和田忍氏(駿河台大学),小河舜氏(フェリス女学院大学ほか)の3名と,酒を交わしながら Beowulf 談義を繰り広げました.とりわけこの作品の専門家である唐澤氏に,Beowulf はいかにして現代に伝わってきたのか,その言葉遣いの特徴は何か,その物語はいつ成立したのか等の質問を投げかけ,回答をいただきました.

本編のみで40分ほどの長尺となっており(しかも終わりの方は少々荒れてい)ますが,時間のあるときにお聴きいただければ.

・ heldio 「#797. 唐澤一友さんに Beowulf のことを何でも質問してみました with 和田忍さん and 小河舜さん」

この作品に関心を抱いた方は,本ブログの beowulf の各記事もご覧下さい.

2023-07-30 Sun

■ #5207. 朝カルのシリーズ講座「文字と綴字の英語史」の第2回「古英語の綴字 --- ローマ字の手なずけ」を終えました [asacul][writing][grammatology][alphabet][notice][spelling][oe][literature][beowulf][runic][christianity][latin][alliteration][distinctiones][punctuation][standardisation][voicy][heldio]

先日「#5194. 7月29日(土),朝カルのシリーズ講座「文字と綴字の英語史」の第2回「古英語の綴字 --- ローマ字の手なずけ」」 ([2023-07-17-1]) でご案内した通り,昨日,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にてシリーズ講座「文字と綴字の英語史」の第2回となる「古英語の綴字 --- ローマ字の手なずけ」を開講しました.多くの方々に対面あるいはオンラインで参加いただきまして感謝申し上げます.ありがとうございました.

古英語期中に,いかにして英語話者たちがゲルマン民族に伝わっていたルーン文字を捨て,ローマ字を受容したのか.そして,いかにしてローマ字で英語を表記する方法について時間をかけて模索していったのかを議論しました.ローマ字導入の前史,ローマ字の手なずけ,ラテン借用語の綴字,後期古英語期の綴字の標準化 (standardisation) ,古英詩 Beowulf にみられる文字と綴字について,3時間お話ししました.

昨日の回をもって全4回シリーズの前半2回が終了したことになります.次回の第3回は少し先のことになりますが,10月7日(土)の 15:00~18:45 に「中英語の綴字 --- 標準なき繁栄」として開講する予定です.中英語期には,古英語期中に発達してきた綴字習慣が,1066年のノルマン征服によって崩壊するするという劇的な変化が生じました.この大打撃により,その後の英語の綴字はカオス化の道をたどることになります.

講座「文字と綴字の英語史」はシリーズとはいえ,各回は関連しつつも独立した内容となっています.次回以降の回も引き続きよろしくお願いいたします.日時の都合が付かない場合でも,参加申込いただけますと後日アーカイブ動画(1週間限定配信)にアクセスできるようになりますので,そちらの利用もご検討ください.

本シリーズと関連して,以下の hellog 記事をお読みください.

・ hellog 「#5088. 朝カル講座の新シリーズ「文字と綴字の英語史」が4月29日より始まります」 ([2023-04-02-1])

・ hellog 「#5194. 7月29日(土),朝カルのシリーズ講座「文字と綴字の英語史」の第2回「古英語の綴字 --- ローマ字の手なずけ」」 ([2023-07-17-1])

同様に,シリーズと関連づけた Voicy heldio 配信回もお聴きいただければと.

・ heldio 「#668. 朝カル講座の新シリーズ「文字と綴字の英語史」が4月29日より始まります」(2023年3月30日)

・ heldio 「#778. 古英語の文字 --- 7月29日(土)の朝カルのシリーズ講座第2回に向けて」(2023年7月18日)

2023-07-29 Sat

■ #5206. Beowulf の冒頭11行を音読 [voicy][heldio][beowulf][oe][literature][oe_text][popular_passage][manuscript]

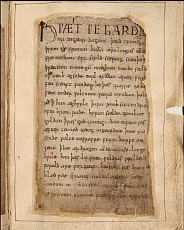

「#2893. Beowulf の冒頭11行」 ([2017-03-29-1]) と「#2915. Beowulf の冒頭52行」 ([2017-04-20-1]) で,古英詩の傑作 Beowulf の冒頭を異なるエディションより紹介しました.今回は Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」と連動させ,この詩の冒頭11行を Jack 版から読み上げてみたので,ぜひ聴いていただければと思います.「#789. 古英詩の傑作『ベオウルフ』の冒頭11行を音読」です.以下に,Jack 版と忍足による日本語訳のテキスト,および写本画像を掲げておきます.

1 Hwæt, wē Gār-Dena in geārdagum, いざ聴き給え,そのかみの槍の誉れ高きデネ人の勲,民の王たる人々の武名は, 2 þēodcyninga þrym gefrūnon, 貴人らが天晴れ勇武の振舞をなせし次第は, 3 hū ðā æþelingas ellen fremedon. 語り継がれてわれらが耳に及ぶところとなった. 4 Oft Scyld Scēfing sceaþena þrēatum, シェーフの子シュルドは,初めに寄る辺なき身にて 5 monegum mǣgþum meodosetla oftēah, 見出されて後,しばしば敵の軍勢より, 6 egsode eorl[as], syððan ǣrest wearð 数多の民より,蜜酒の席を奪い取り,軍人らの心胆を 7 fēasceaft funden; hē þæs frōfre gebād, 寒からしめた.彼はやがてかつての不幸への慰めを見出した. 8 wēox under wolcnum, weorðmyndum þāh, すなわち,天が下に栄え,栄光に充ちて時めき, 9 oðþæt him ǣghwylc þ[ǣr] ymbsittendra 遂には四隣のなべての民が 10 ofer hronrāde hȳran scolde, 鯨の泳ぐあたりを越えて彼に靡き, 11 gomban gyldan. Þæt wæs gōd cyning! 貢を献ずるに至ったのである.げに優れたる君王ではあった.

Beowulf については,本ブログでも beowulf の各記事で取り上げてきました.また,この作品については,先日 Voicy heldio で専門家との対談を収録・配信したので,そちらもお聴き下さい.「#783. 古英詩の傑作『ベオウルフ』 (Beowulf) --- 唐澤一友さん,和田忍さん,小河舜さんと飲みながらご紹介」です.

古英語の響きに関心を持った方は,ぜひ Voicy heldio より以下もお聴きいただければ.

・ 「#326. どうして古英語の発音がわかるのですか?」

・ 「#321. 古英語をちょっとだけ音読 マタイ伝「岩の上に家を建てる」寓話より」

・ 「#735. 古英語音読 --- マタイ伝「種をまく人の寓話」より毒麦の話」

・ 「#766. 古英語をちょっとだけ音読 「キャドモンの賛歌」」

・ Jack, George, ed. Beowulf: A Student Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1994.

・ 忍足 欣四郎(訳) 『ベーオウルフ』 岩波書店,1990年.

2023-07-24 Mon

■ #5201. 古英語で書かれた英雄詩 Beowulf 『ベオウルフ』 [voicy][heldio][oe][literature][link]

昨日,Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」で「#783. 古英詩の傑作『ベオウルフ』 (Beowulf) --- 唐澤一友さん,和田忍さん,小河舜さんと飲みながらご紹介」を配信しました(27分ほどの尺となっています)

出演者の皆さんが Beowulf の専門家といってもよいですが,とりわけ唐澤先生にとってはストライクの話題です,唐澤先生とは一度 heldio で対談しています.そのときには古英語と無関係の「#314. 唐澤一友先生との対談 今なぜ世界英語への関心が高まっているのか?」という話題でお届けしましたが,本来のご専門は古英語とその文学です.

Beowulf の概要については上記の配信よりお聴きいただければと思いますが,ここでも簡単に紹介しておきます.Beowulf は古英語文学の最高傑作とされる英雄詩であり,ヨーロッパにおいて最も早くヴァナキュラーで著わされた叙事詩です.紀元1000年頃のものと推定される唯一写本 Cotton Vitellius A XV に納められたテキストだが,物語としては6世紀初頭の出来事を扱っており,作られたのは8世紀前半と考えられています.テキストの存在は近代まで広く知られることはなく,ようやく19世紀前半に印刷されることになりました.

物語は主人公ベオウルフの冒険と生涯を軸に進んでいきますが,この人物が歴史的存在であるという証拠はありません.ただし,物語の登場人物,場所,出来事のなかには,歴史的に確認できるものが含まれています.

形式,文体,主題の観点からは,Beowulf はゲルマン英雄詩の伝統に乗った作品といえます.主人公が怪物の腕を引き裂く場面や湖に潜る場面を含め多くのエピソードが民間伝承に基づくものです.倫理的価値観としては運命・忠誠心・復讐など明らかにゲルマン的な要素が濃い一方で,キリスト教的な精神も強く,実際にキリスト教の寓意詩であるとの評価も一般的に受け入れられています.

現代英語訳や和訳もあり,映画化もされている古英語文学の至宝です.ぜひ関心をもっていただければ.hellog でも beowulf の各記事で取り上げてきたので,ご覧ください.

今回の heldio 出演者の HP 等へリンクを張っておきます.

・ 唐澤一友先生(立教大学)

・ 和田忍先生(駿河台大学)

・ 小河舜先生(フェリス女学院大学ほか)

2023-07-17 Mon

■ #5194. 7月29日(土),朝カルのシリーズ講座「文字と綴字の英語史」の第2回「古英語の綴字 --- ローマ字の手なずけ」 [asacul][notice][writing][spelling][orthography][oe][link][voicy][heldio]

来週末7月29日(土)の 15:30--18:45 に,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にてシリーズ講座「文字と綴字の英語史」の第2回となる「古英語の綴字 --- ローマ字の手なずけ」が開講されます.

シリーズ初回は「文字の起源と発達 --- アルファベットの拡がり」と題して3ヶ月前の4月29日(土)に開講しました.それを受けて第2回は,ローマ字が英語に入ってきて本格的に用いられ始めた古英語期に焦点を当てます.古英語話者たちは,ローマ字をいかにして受容し,格闘しながらも自らの道具として手なずけていったのか,その道筋をたどります.実際にローマ字で書かれた古英語のテキストの読解にも挑戦してみたいと思います.

ご関心のある方はぜひご参加ください.講座紹介および参加お申し込みはこちらからどうぞ.対面のほかオンラインでの参加も可能です.また,参加登録された方には,後日アーカイヴ動画(1週間限定配信)のリンクも送られる予定です.ご都合のよい方法でご参加ください.全4回のシリーズものではありますが,各回の内容は独立していますので,単発のご参加も歓迎です.

シリーズ全4回のタイトルは以下の通りとなります.

・ 第1回 文字の起源と発達 --- アルファベットの拡がり(春・4月29日)

・ 第2回 古英語の綴字 --- ローマ字の手なずけ(夏・7月29日)

・ 第3回 中英語の綴字 --- 標準なき繁栄(秋・未定)

・ 第4回 近代英語の綴字 --- 標準化を目指して(冬・未定)

本シリーズと関連して,以下の hellog 記事,および Voicy heldio 配信回もご参照下さい.

・ hellog 「#5088. 朝カル講座の新シリーズ「文字と綴字の英語史」が4月29日より始まります」 ([2023-04-02-1])

・ heldio 「#668. 朝カル講座の新シリーズ「文字と綴字の英語史」が4月29日より始まります」(2023年3月30日)

・ (2023/07/18(Tue) 後記)heldio 「#778. 古英語の文字 --- 7月29日(土)の朝カルのシリーズ講座第2回に向けて」(2023年7月18日)

2023-07-13 Thu

■ #5190. 小河舜さんとの heldio 対談と YouTube 共演 [ogawashun][voicy][heldio][youtube][wulfstan][oe][old_norse][history][anglo-saxon][literature][toponymy][onomastics]

昨日「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」の最新回がアップされました.「#144. イギリスの地名にヴァイキングの足跡 --- ゲスト・小河舜さん」です.小河舜さんを招いての全4回シリーズの第1弾となります.

小河さんの研究テーマは後期古英語期の説教師・政治家 Wulfstan とその言語です.立教大学の博士論文として "Wulfstan as an Evolving Stylist: A Chronological Study on His Vocabulary and Style." を提出し,学位授与されています.Wulfstan については本ブログより「#5176. 後期古英語の聖職者 Wulfstan とは何者か? --- 小河舜さんとの heldio 対談」 ([2023-06-29-1]) をご覧ください.また,小河さんは今回の YouTube の話題のように,イギリスの地名(特に古ノルド語要素を含む地名)にも関心をお持ちです.

小河さんとは,今回の YouTube 共演以前にも,Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」で複数回にわたり対談し,その様子を配信してきました.実際,今朝の heldio 最新回でも小河さんとの対談を配信しています.これまでの対談回を一覧にまとめましたので,ぜひお時間のあるときにお聴きいただければ.

・ 「#759. Wulfstan て誰? --- 小河舜さんとの対談【第1弾】」(6月29日配信)

・ 「#761. Wulfstan の生きたヴァイキング時代のイングランド --- 小河舜さんとの対談【第2弾】」(7月1日配信)

・ 「#763. Wulfstan がもたらした超重要単語 "law" --- 小河舜さんとの対談【第3弾】」(7月3日配信)

・ 「#765. Wulfstan のキャリアとレトリックの変化 --- 小河舜さんとの対談【第4弾】」(7月5日配信)

・ 「#767. Wulfstan と小河さんのキャリアをご紹介 --- 小河舜さんとの対談【第5弾】」(7月7日配信)

・ 「#770. 大学での英語史講義を語る --- 小河舜さんとの対談【第6弾】」(7月10日配信)

・ 「#773. 小河舜さんとの新シリーズの立ち上げなるか!?」(本日7月13日配信)

小河さんの今後の英語史活動(hel活)にも期待しています!

(以下は,2023/08/02(Wed) 付で加えた後記です)

・ YouTube 小河舜さんシリーズ第1弾:「#144. イギリスの地名にヴァイキングの足跡 --- ゲスト・小河舜さん」です

・ YouTube 小河舜さんシリーズ第2弾:「#146. イングランド人説教師 Wulfstan のバイキングたちへの説教は歴史的異言語接触!」

・ YouTube 小河舜さんシリーズ第3弾:「#148. 天才説教師司教は詩的にヴァイキングに訴えかける!?」

・ YouTube 小河舜さんシリーズ第4弾:「#150. 宮崎県西米良村が生んだ英語学者(philologist)でピアニスト小河舜さん第4回」

2023-06-29 Thu

■ #5176. 後期古英語の聖職者 Wulfstan とは何者か? --- 小河舜さんとの heldio 対談 [ogawashun][voicy][heldio][wulfstan][oe][old_norse][history][anglo-saxon][literature]

今朝の Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」で,「#759. Wulfstan て誰? --- 小河舜さんとの対談【第1弾】」を配信しました.対談相手の小河舜さんは,この Wulfstan とその著作の言語(古英語)を研究し,博士号(立教大学)を取得されています.対談の第1弾と銘打っている通り,今後,第2弾以降も順次お届けしていく予定です.

Wulfstan は,996--1002年にロンドン司教,1002--1023年にヨーク大司教,そして1002--1016年にウースター司教を務めた聖職者で,Lupus (狼)の仮名で古英語の説教,論文,法典を多く著わしました.ベネディクト改革を受けて現われた,当時の宗教界・政治界の重要人物です.司教になる前の経歴は不明です.

Wulfstan の文体は独特なものとして知られており,作品の正典はおおよそ確立されています.1008年から Æthelred と Canute の2人の王の顧問を務め,法律を起草しました.Wulfstan は,Canute にキリスト教の王として統治するよう促し,アングロサクソン文化を破壊から救った人物としても評価されています.Wulfstan は政治や社会のあり方に関心をもち,Institutes of Polity を著わしています.そこでは,王を含むすべての階級の責任を記述し,教会と国家の関係について論じています.

Wulfstan は教会改革にも深く関わっており,教会法の文献を研究しました.また,Ælfric に2通の牧会書簡を書くように依頼し,自身も The Canons of Edgar として知られるテキストを書いています.

Wulfstan の最も有名な作品は,Æthelred がデンマークの Sweyn 王に追放された後に,同胞に改悛と改革を呼びかけた情熱的な Sermo Lupi ad Anglos (1014) です.

Wulfstan は,アングロサクソン人にとってきわめて多難な時代に,政治の舵取りを任された人物でした.彼にとって,レトリックはこの難局を克服するための重要な手段だったはずです.悩める Wulfstan の活躍した時代背景やそのレトリックについて,小河さんとの今後の対談にご期待ください.

2023-06-05 Mon

■ #5152. 古英語聖書より「種をまく人の寓話」 --- 毒麦の話 [oe][popular_passage][bible][literature][oe_text][hel_education][voicy][heldio]

古英語テキストを原文で読むシリーズ.新約聖書のマタイ伝より13章の「種をまく人の寓話」より24--30節の毒麦の話を,古英語版で味わってみよう.以下,Sweet's Anglo-Saxon Primer (9th ed.) の校訂版より引用する.あわせて,1611年の The Authorised Version (The King James Version [KJV]) の近代英語訳と日本語口語訳も添えておく.

[ 古英語 ]

Heofona rīċe is ġe·worden þǣm menn ġe·līċ þe sēow gōd sǣd on his æcere. Sōþlīċe, þā þā menn slēpon, þā cōm his fēonda sum, and ofer·sēow hit mid coccele on·middan þǣm hwǣte, and fērde þanon. Sōþlīċe, þā sēo wyrt wēox, and þone wæstm brōhte, þā æt·īewde se coccel hine. Þā ēodon þæs hlāfordes þēowas and cwǣdon: 'Hlāford, hū, ne sēowe þū gōd sǣd on þīnum æcere? Hwanon hæfde hē coccel?' Þā cwæþ hē; 'Þæt dyde unhold mann.' Þā cwǣdon þā þēowas 'Wilt þū, wē gāþ and gadriaþ hīe?' Þā cwæþ hē: 'Nese: þȳ·lǣs ġē þone hwǣte ā·wyrtwalien, þonne ġē þone coccel gadriaþ. Lǣtaþ ǣġþer weaxan oþ rīp-tīman; and on þǣm rīptīman iċ secge þǣm rīperum: "Gadriaþ ǣrest þone coccel, and bindaþ scēaf-mǣlum tō for·bærnenne; and gadriaþ þone hwǣte in-tō mīnum berne."'

[ 近代英語 ]

[24] . . . The kingdom of heaven is likened unto a man which sowed good seed in his field: [25] But while men slept, his enemy came and sowed tares among the wheat, and went his way. [26] But when the blade was sprung up, and brought forth fruit, then appeared the tares also. [27] So the servants of the householder came and said unto him, Sir, didst not thou sow good seed in thy field? from whence then hath it tares? [28] He said unto them, An enemy hath done this. The servants said unto him, Wilt thou then that we go and gather them up? [29] But he said, Nay; lest while ye gather up the tares, ye root up also the wheat with them. [30] Let both grow together until the harvest: and in the time of harvest I will say to the reapers, Gather ye together first the tares, and bind them in bundles to burn them: but gather the wheat into my barn.

[ 日本語口語訳 ]

[24] ………「天国は,良い種を自分の畑にまいておいた人のようなものである.[25] 人々が眠っている間に敵がきて,麦の中に毒麦をまいて立ち去った.[26] 芽がはえ出て実を結ぶと,同時に毒麦もあらわれてきた.[27] 僕たちがきて,家の主人に言った,『ご主人様,畑におまきになったのは,良い種ではありませんでしたか.どうして毒麦がはえてきたのですか』.[28] 主人は言った,『それは敵のしわざだ』.すると僕たちが言った『では行って,それを抜き集めましょうか』.[29] 彼は言った,『いや,毒麦を集めようとして,麦も一緒に抜くかも知れない.[30] 収穫まで,両方とも育つままにしておけ.収穫の時になったら,刈る者に,まず毒麦を集めて束にして焼き,麦の方は集めて倉に入れてくれ,と言いつけよう』」.

今回は Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」との連動企画として,上記の古英語テキストを「#735. 古英語音読 --- マタイ伝「種をまく人の寓話」より毒麦の話」で読み上げています.ぜひお聴きください.

加えて,マタイ伝の同章の少し前の箇所,3--8節のくだりについて,関連する「#2906. 古英語聖書より「種をまく人の寓話」」 ([2017-04-11-1]) も参照.ほかに古英語聖書のテキストとしては「#2895. 古英語聖書より「岩の上に家を建てる」」 ([2017-03-31-1]),「#1803. Lord's Prayer」 ([2014-04-04-1]),「#1870. 「創世記」2:18--25 を7ヴァージョンで読み比べ」 ([2014-06-10-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Davis, Norman. Sweet's Anglo-Saxon Primer. 9th ed. Oxford: Clarendon, 1953.

2023-04-01 Sat

■ #5087. 「英語史クイズ with まさにゃん」 in Voicy heldio とクイズ問題の関連記事 [masanyan][helquiz][link][silent_letter][etymological_respelling][kenning][oe][metonymy][metaphor][gender][german][capitalisation][punctuation][trademark][alliteration][sound_symbolism][goshosan][voicy][heldio]

新年度の始まりの日です.学びの意欲が沸き立つこの時期,皆さんもますます英語史の学びに力を入れていただければと思います.私も「hel活」に力を入れていきます.

実はすでに新年度の「hel活」は始まっています.昨日と今日とで年度をまたいではいますが,Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」にて「英語史クイズ」 (helquiz) の様子を配信中です.出題者は khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)会長のまさにゃん (masanyan),そして回答者はリスナー代表(?)の五所万実さん(目白大学; goshosan)と私です.ワイワイガヤガヤと賑やかにやっています.

・ 「#669. 英語史クイズ with まさにゃん」

・ 「#670. 英語史クイズ with まさにゃん(続編)」

実際,コメント欄を覗いてみると分かる通り,昨日中より反響をたくさんいただいています.お聴きの方々には,おおいに楽しんでいただいているようです.出演者のお二人にもコメントに参戦していただいており,場外でもおしゃべりが続いている状況です.こんなふうに英語史を楽しく学べる機会はあまりないと思いますので,ぜひ hellog 読者の皆さんにも聴いて参加いただければと思います.

以下,出題されたクイズに関連する話題を扱った hellog 記事へのリンクを張っておきます.クイズから始めて,ぜひ深い学びへ!

[ 黙字 (silent_letter) と語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) ]

・ 「#116. 語源かぶれの綴り字 --- etymological respelling」 ([2009-08-21-1])

・ 「#192. etymological respelling (2)」 ([2009-11-05-1])

・ 「#1187. etymological respelling の具体例」 ([2012-07-27-1])

・ 「#580. island --- なぜこの綴字と発音か」 ([2010-11-28-1])

・ 「#1290. 黙字と黙字をもたらした音韻消失等の一覧」 ([2012-11-07-1])

[ 古英語のケニング (kenning) ]

・ 「#472. kenning」 ([2010-08-12-1])

・ 「#2677. Beowulf にみられる「王」を表わす数々の類義語」 ([2016-08-25-1])

・ 「#2678. Beowulf から kenning の例を追加」 ([2016-08-26-1])

・ 「#1148. 古英語の豊かな語形成力」 ([2012-06-18-1])

・ 「#3818. 古英語における「自明の複合語」」 ([2019-10-10-1])

[ 文法性 (grammatical gender) ]

・ 「#4039. 言語における性とはフェチである」 ([2020-05-18-1])

・ 「#3647. 船や国名を受ける she は古英語にあった文法性の名残ですか?」 ([2019-04-22-1])

・ 「#4182. 「言語と性」のテーマの広さ」 ([2020-10-08-1])

[ 大文字化 (capitalisation) ]

・ 「#583. ドイツ語式の名詞語頭の大文字使用は英語にもあった」 ([2010-12-01-1])

・ 「#1844. ドイツ語式の名詞語頭の大文字使用は英語にもあった (2)」 ([2014-05-15-1])

・ 「#1310. 現代英語の大文字使用の慣例」 ([2012-11-27-1])

・ 「#2540. 視覚の大文字化と意味の大文字化」 ([2016-04-10-1])

[ 頭韻 (alliteration) ]

・ 「#943. 頭韻の歴史と役割」 ([2011-11-26-1])

・ 「#953. 頭韻を踏む2項イディオム」 ([2011-12-06-1])

・ 「#970. Money makes the mare to go.」 ([2011-12-23-1])

・ 「#2676. 古英詩の頭韻」 ([2016-08-24-1])

2023-02-25 Sat

■ #5052. none は単数扱いか複数扱いか? [sobokunagimon][pronoun][indefinite_pronoun][number][agreement][negative][proverb][shakespeare][oe][singular_they][link]

不定人称代名詞 (indefinite_pronoun) の none は「誰も~ない」を意味するが,動詞とは単数にも複数にも一致し得る.None but the brave deserve(s) the fair. 「勇者以外は美人を得るに値せず」の諺では,動詞は3単現の -s を取ることもできるし,ゼロでも可である.規範的には単数扱いすべしと言われることが多いが,実際にはむしろ複数として扱われることが多い (cf. 「#301. 誤用とされる英語の語法 Top 10」 ([2010-02-22-1])) .

none は語源的には no one の約まった形であり one を内包するが,数としてはゼロである.分かち書きされた no one は同義で常に単数扱いだから,none も数の一致に関して同様に振る舞うかと思いきや,そうでもないのが不思議である.

しかし,American Heritage の注によると,none の複数一致は9世紀からみられ,King James Bible, Shakespeare, Dryden, Burke などに連綿と文証されてきた.現代では,どちらの数に一致するかは文法的な問題というよりは文体的な問題といってよさそうだ.

Visser (I, § 86; pp. 75--76) には,古英語から近代英語に至るまでの複数一致と単数一致の各々の例が多く挙げられている.最古のものから Shakespeare 辺りまででいくつか拾い出してみよう.

86---None Plural.

Ælfred, Boeth. xxvii §1, þæt þær nane oðre an ne sæton buton þa weorðestan. | c1200 Trin. Coll. Hom. 31, Ne doð hit none swa ofte se þe hodede. | a1300 Curs. M. 11396, bi-yond þam ar wonnand nan. | 1534 St. Th. More (Wks) 1279 F10, none of them go to hell. | 1557 North, Gueuaia's Diall. Pr. 4, None of these two were as yet feftene yeares olde (OED). | 1588 Shakesp., L.L.L. IV, iii, 126, none offend where all alike do dote. | Idem V, ii, 69, none are so surely caught . . ., as wit turn'd fool. . . .

Singular.

Ælfric, Hom. i, 284, i, Ne nan heora an nis na læsse ðonne eall seo þrynnys. | Ælfred, Boeth. 33. 4, Nan mihtigra ðe nis ne nan ðin gelica. | Charter 41, in: O. E. Texts 448, ȝif þæt ȝesele . . . ðæt ðer ðeara nan ne sie ðe londes weorðe sie. | a1122 O. E. Chron. (Laud Ms) an. 1066, He dyde swa mycel to gode . . . swa nefre nan oðre ne dyde toforen him. | a1175 Cott. Hom. 217, ȝif non of him ne spece, non hine ne lufede (OED). | c1250 Gen. & Ex. 223, Ne was ðor non lik adam. | c1450 St. Cuthbert (Surtees) 4981, Nane of þair bodys . . . Was neuir after sene. | c1489 Caxton, Blanchardyn xxxix, 148, Noon was there, . . . that myghte recomforte her. | 1588 A. King, tr. Canisius' Catch., App., To defende the pure mans cause, quhen thair is nan to take it in hadn by him (OED). | 1592 Shakesp., Venus 970, That every present sorrow seemeth chief, But none is best.

none の音韻,形態,語源,意味などについては以下の記事も参照.

・ 「#1297. does, done の母音」 ([2012-11-14-1])

・ 「#1904. 形容詞の no と副詞の no は異なる語源」 ([2014-07-14-1])

・ 「#2723. 前置詞 on における n の脱落」 ([2016-10-10-1])

・ 「#2697. few と a few の意味の差」 ([2016-09-14-1])

・ 「#3536. one, once, none, nothing の第1音節母音の問題」 ([2019-01-01-1])

・ 「#4227. なぜ否定を表わす語には n- で始まるものが多いのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版」 ([2020-11-22-1])

また,数の不一致についても,これまで何度か取り上げてきた.英語史的には singular_they の問題も関与してくる.

・ 「#1144. 現代英語における数の不一致の例」 ([2012-06-14-1])

・ 「#1334. 中英語における名詞と動詞の数の不一致」 ([2012-12-21-1])

・ 「#1355. 20世紀イギリス英語で集合名詞の単数一致は増加したか?」 ([2013-01-11-1])

・ 「#1356. 20世紀イギリス英語での government の数の一致」 ([2013-01-12-1])

・ Visser, F. Th. An Historical Syntax of the English Language. 3 vols. Leiden: Brill, 1963--1973.

2022-10-06 Thu

■ #4910. 中英語と古英語の違い3点 --- 借用語の増加,標準の不在,屈折語尾の水平化 [oe][me][loan_word][standardisation][inflection][synthesis_to_analysis]

古い Wardale の中英語入門書の復刻版を手に取っている.中英語 (Middle English) は古英語 (Old English or Anglo-Saxon) と何がどう異なるのか.Wardale (2--3) が明快に3点を挙げている.

(a) One of these marked differences is that whereas the latter contained very little foreign element, only a limited number of Latin words and a very few from Celtic and other sources being found, the vocabulary of Middle English has been enormously enriched, especially from Old Norse and French.

(b) Another point of distinction is that whereas in the O.E. period the West Saxon dialect under Ælfred's encouragement of learning had come to be the standard literary dialect, the others being relegated chiefly to colloquial use, in M.E. times no such state of affairs existed. In them all dialects were used for literary purposes and only towards the end of the period do we find that of Chaucer beginning to assume its position as the leading literary language.

(c) But more important than these external points of difference, if perhaps less obvious, and more essential because inherent in the language itself, is the modification which gradually made itself seen in that language. English, like all Germanic tongues, has at all times been governed by what is known as the Germanic accent law, that is by the system of stem accentuation. By this law, except in a few cases, the chief emphasis of the word was thrown on the stem syllable, all others remaining less stressed or entirely unaccented. . . . But by [the M.E. period] all vowels in unaccented syllables have been levelled under one uniform sound e . . .

つまり,古英語と比べたときの中英語の際立ちは3点ある.豊富な借用語,標準変種の不在,無強勢母音の水平化だ.とりわけ,3点目が言語内的で本質的な特徴であり,それは2つの重大な結果をもたらしたと,Wardale (3--4) は議論する.

The consequences of this levelling of all unaccented vowels under one are twofold.

(a) Since many inflectional endings had by this means lost their distinctive value, as when a nominative singular caru, care, an a nominative plural cara both gave a M.E. care, or a nominative plural limu, limbs, and a genitive plural lima both gave a M.E. lime, those few endings which did remain distinctive, such as the -es, of the nominative plural of most masculine nouns, were for convenience' sake gradually taken for general use and the regularly developed plurals care and lime were replaced by cares and limes. In the same way and for the same reason the -es of genitive singular ending of most masculine and neuter nouns came gradually to be used in other declensions as when for an O.E. lāre, lore's we find a M.E. lǫres

(b) The second consequence follows as naturally. The older method of indicating the relationship between words in a sentence having thus become inadequate, it was necessary to fin another, and pronouns, prepositions, and conjunctions came more and more into use. Thus an O.E. bōca full, which would have normally given a M.E. bōke full was replaced by the phrase full of bōkes, and an O.E. subjunctive hie 'riden, which in M.E. would have been indistinguishable from the indicative riden from an O.E. ridon, by the phrase if hi riden. In short, English from having been a synthetic language, became one which was analytic.

1つめの結果は,明確に区別される -es のような優勢な屈折語尾が一般化したということだ.2つめは,語と語の関係を標示するのに屈折に頼ることができなくなったために,代名詞,前置詞,接続詞といった語類に依存する度合が増し,総合的な言語から分析的な言語へ移行したことだ.

以上,中英語と古英語の違いについて要を得た説明だったので紹介した.

・ Wardale, E. E. An Introduction to Middle English. Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1937. 2016. Abingdon: Routledge, 2016.

2022-07-30 Sat

■ #4842. 英語は歴史の始まりからすでに混種言語だった? [variety][dialect][germanic][oe][jute][history][oe_dialect][anglo-saxon][dialect_contact][dialect_mixture]

1860年代に出版された Marsh による英語史講義録をパラパラめくっている.Marsh によれば,アングロサクソン語,すなわち古英語は,大陸からブリテン島に持ち込まれた諸方言の混合体であり,その意味においてブリテン島に "aboriginal" な言語とは言えないものの "indigenous" な言語ではあると述べている.言語としては混合体ならではの "diversity" を示し,"obscure", "confused", "imperfect", "anomalous", "irregular" であるという.以下,関連する箇所を引用する.

§15. It has been already shown that the Anglo-Saxon conquerors consisted of several tribes. The border land of the Scandinavian and Teutonic races, whence the Anglo-Saxon invaders emigrated, has always been remarkable for the number of its local dialects. The Friesian, which bears a closer resemblance than any other linguistic group to the English, differs so much in different localities, that the dialects of Friesian parishes, separated only by a narrow arm of the sea, are often quite unintelligible to the inhabitants of each other. Moreover, the Anglo-Saxon language itself supplies internal evidence that there was a great commingling of nations in the invaders of our island. This language, in its obscure etymology, its confused and imperfect inflexions, and its anomalous and irregular syntax, appears to me to furnish abundant proof of a diversity, not of a unity, of origin. It has not what is considered the distinctive character of a modern, so much as of a mixed and ill-assimilated speech, and its relations to the various ingredients of which it is composed are just those of the present English to its own heterogeneous sources. It borrowed roots, and dropped endings, appropriated syntactical combinations without the inflexions which made them logical, and had not yet acquired a consistent and harmonious structure when the Norman conquest arrested its development, and imposed upon it, or, perhaps we should say, gave a new stimulus to, the tendencies which have resulted in the formation of modern English. There is no proof that Anglo-Saxon was ever spoken anywhere but on the soil of Great Britain; for the 'Heliand,' and other remains of old Saxon, are not Anglo-Saxon, and I think it must be regarded, not as a language which the colonists, or any of them, brought with them from the Continent, but as a new speech resulting from the fusion of many separate elements. It is, therefore, indigenous, if not aboriginal, and as exclusively local and national in its character as English itself.

古英語の生成に関する Marsh のこの洞察は優れていると思う.しかし,評価するにあたり,この講義録がイギリス帝国の絶頂期に出版されたという時代背景は念頭に置いておくべきだろう.引用の最後にある "exclusively local and national in its character as English itself" も,その文脈で解釈する必要があるように思われる.

古英語の生成については「#389. Angles, Saxons, and Jutes の故地と移住先」 ([2010-05-21-1]),「#2868. いかにして古英語諸方言が生まれたか」 ([2017-03-04-1]),「#4439. 古英語は混合方言として始まった?」 ([2021-06-22-1]) の記事も参照.

・ Marsh, George Perkins. Lectures on the English Language: Edited with Additional Lectures and Notes. Ed. William Smith. 4th ed. London: John Murray, 1866. Rpt. HardPress, 2012.

2022-06-03 Fri

■ #4785. It is ... that ... の強調構文の古英語からの例 [syntax][cleft_sentence][personal_pronoun][oe]

学校文法で「強調構文」と呼ばれる統語構造は,英語学では「分裂文」 (cleft_sentence) と称されることが多い.分裂文の起源と発達については「#2442. 強調構文の発達 --- 統語的現象から語用的機能へ」 ([2016-01-03-1]),「#3754. ケルト語からの構造的借用,いわゆる「ケルト語仮説」について」 ([2019-08-07-1]),「#4595. 強調構文に関する「ケルト語仮説」」 ([2021-11-25-1]) などで取り上げてきた.

歴史的事実としては,使用例は古英語からみられる.ただし,古英語では,it はほとんど用いられず,省略されるか,あるいは þæt が用いられた.Visser (§63) より,いくつか例を示そう.

63---g. The type 'It is father who did it.'

This periphrastic construction is used to bring a part of a syntactical unit into prominence; it is especially employed when contrast has to be expressed: 'It is father (not mother) who did it'. In Old English hit is omitted (e.g. O. E. Gosp., John VI, 63, 'Gast is se þe geliffæst'; O. E. Homl. ii, 234, 'min fæder is þe me wuldrað') or its place is taken by þæt (e.g. Ælfred, Boeth. 34, II, 'is þæt for mycel gcynd þæt urum lichoman cymð eall his mægen of þam mete þe we þicgaþ'; Wulfstan, Polity (Jost) p. 127 則183, þæt is laðlic lif, þæt hi swa maciað; O. E. Chron. an. 1052, 'þæt wæs on þone monandæg ... þæt Godwine mid his scipum to suðgeweorce becom'). This pronoun þæt is still so used in: Orm 8465, 'þætt wass þe lond off Galileo þætt himm wass bedenn sekenn'.

中英語以降は it がよく使用されるようになったようだ.

名詞(句)ではなく時間や場所を表わす副詞(句)が強調される例も,上記にある通りすでに古英語からみられるが,それに対する Visser (§63) の解釈が注目に値する.そのような場合の is は意味的に happens に近いという.

When it was, it is has an adverbial adjunct of time or place as a complement, (as e.g. in 'It was on the first of May that I saw him first'), to be is not a copula, but the notional to be with the sense 'to happen', 'to take place' that also occurs in constructions of a different pattern, such as are found in e.g. C1350 Will. Palerne 1930, 'Manly on þe morwe þat mariage schuld bene; 1947 H. Eustis, The Horizontal Man (Penguin) 41, 'Keep your trap shut when you don't know what you're talking about, which is usually'; Pres. D. Eng.: 'The flower-show was last week' (OED).

分裂文の起源と発達は,英語統語史上の重要な課題である.

・ Visser, F. Th. An Historical Syntax of the English Language. 3 vols. Leiden: Brill, 1963--1973.

2022-05-31 Tue

■ #4782. cleanse に痕跡を残す動詞形成接尾辞 -(e)sian [suffix][etymology][oe][verb][word_formation][derivation][vowel][shortening][shocc]

昨日の記事「#4781. open と warn の -(e)n も動詞形成接尾辞」 ([2022-05-30-1]) で,古英語の動詞形成接尾辞 -(e)nian を取り上げた.古英語にはほかに -(e)sian という動詞形成接尾辞もあった.やはり弱変化動詞第2類が派生される.

昨日と同様に,Lass と Hogg and Fulk から引用する形で,-(e)sian についての解説と単語例を示したい.

(i) -s-ian. Many class II weak verbs have an /-s-/ formative: e.g. clǣn-s-ian 'cleanse' (clǣne 'clean', rīc-s-ian 'rule' (rīce 'kingdom'), milt-s-ian 'take pity on' (mild 'mild'). The source of the /-s-/ is not entirely clear, but it may well reflect the IE */-s-/ formative that appears in the s-aorist (L dic-ō 'I say', dīxī 'I said' = /di:k-s-i:/). Alternants with /-s-/ in a non-aspectual function do however appear in the ancient dialects (Skr bhā-s-ati 'it shines' ~ bhā-ti), and even within the same paradigm in the same category (GR aléks-ō 'I protect', infinitive all-alk-ein). (Lass 203)

(iii) verbs in -(e)sian, including blētsian 'bless', blīðsian, blissian 'rejoice', ġītsian 'covet', grimsian 'rage', behrēowsian 'reprent', WS mǣrsian 'glorify', miltsian 'pity', rīcsian, rīxian 'rule', unrōtsian 'worry', untrēowsian 'disbelieve', yrsian 'rage'. (Hogg and Fulk 289)

古英語としてはよく見かける動詞が多いのだが,残念ながら昨日の -(e)nian と同様に,現在まで残っている動詞は稀である.その1語が cleanse である.形容詞 clean /kliːn/ に対応する動詞 cleanse /klɛnz/ だ.母音が短くなったことについては「#3960. 子音群前位置短化の事例」 ([2020-02-29-1]) を参照.

2022-05-30 Mon

■ #4781. open と warn の -(e)n も動詞形成接尾辞 [suffix][etymology][oe][verb][word_formation][derivation]

昨日の記事「#4780. weaken に対して strengthen, shorten に対して lengthen」 ([2022-05-29-1]) で,動詞を形成する接尾辞 -en に触れた.この接尾辞 (suffix) については「#1877. 動詞を作る接頭辞 en- と接尾辞 -en」 ([2014-06-17-1]),「#3987. 古ノルド語の影響があり得る言語項目 (2)」 ([2020-03-27-1]) の記事などでも取り上げてきた.

この接尾辞は古英語の -(e)nian に由来し,さらにゲルマン語にもさかのぼる古い動詞形成要素である.古英語では,名詞あるいは形容詞から動詞を派生させるのに特に用いられ,その動詞は弱変化動詞第2類に属する.古英語からの例を Lass (203) より解説とともに引用する.

(iii) -n-. An /-n-/ formative, reflecting an extended suffix */-in-o:n/, appears in a number of class II weak verbs, especially denominal and deadjectival: fæst-n-ian 'fasten' (fæst), for-set-n-ian 'beset' (for-settan 'hedge in, obstruct'), lāc-n-ian 'heal, cure' (lǣce 'physician'). The type is widespread in Germanic: cf. Go lēki-n-ōn, OHG lāhhi-n-ōn, OS lāk-n-ōn.

同じく Hogg and Fulk (289) からも挙げておこう.

(ii) verbs in -(e)nian, including ġedafenian 'befit' (cf. ġedēfe 'fitting'), fæġ(e)-nian 'rejoice' (cf. fæġe 'popular'), fæstnian 'fasten' (cf. fæst 'firm'), hafenian 'hold' (cf. habban 'have'), lācnian 'heal' (cf. lǣċe 'doctor'), op(e)nian 'open' (cf. upp 'up'), war(e)nian 'warn' (cf. warian 'beware'), wilnian 'desire' (cf. willa 'desire'), wītnian 'punish' (cf. wīte 'punishment') . . . .

現在まで存続している動詞は多くないが,例えば open, warn の -(e)n にその痕跡を認めることができる.現在の多くの -en 動詞は,古英語にさかのぼるわけではなく,中英語期以降の新しい語形成である.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

・ Hogg, Richard M. and R. D. Fulk. A Grammar of Old English. Vol. 2. Morphology. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2022-05-20 Fri

■ #4771. 古英語の3人称単数女性代名詞の対格 hie が与格 hire に飲み込まれた時期 [case][personal_pronoun][oe][inflection][paradigm][eme][laeme]

she の語源説について,連日 Laing and Lass の論文を取り上げてきた(cf. 「#4769. she の語源説 --- Laing and Lass による "Yod Epenthesis" 説の紹介」 ([2022-05-18-1]),「#4770. she の語源説 --- Laing and Lass による "Yod Epenthesis" 説の評価」 ([2022-05-19-1])) .

同論文の主な関心は3人称単数女性代名詞主格の形態についてだが,対格と与格の形態についても触れている.古英語の標準的なパラダイムによれば,対格は hīe,与格は hire の形態を取ったが,後の歴史をみれば明らかな通り,与格形が対格形を飲み込む形で「目的格 her」が生じることになった.この点でいえば,他の3人称代名詞でも同じことが起こっている.単数男性与格の him が対格 hine を飲み込み,複数与格の him が対格 hīe を飲み込んだ(後にそれ自身が them に置換されたが).

3人称代名詞に関して与格が対格を飲み込んだというこの現象(与格方向への対格の水平化)はあまり注目されず,およそいつ頃のことだったのだろうかと疑問が生じるが,単数女性に関しては Laing and Lass (209) による丁寧な説明があった.

By the time ME proper begins to emerge, and to survive in the written record in the mid to late twelfth century, the new 'she' type for the subject pronoun already begins to be found. For the object pronoun the levelling of the 'her/hir' type from the OE DAT/GEN variants is also already the majority for direct object function. For the fem sg personal pronoun used as direct object ($/P13OdF), LAEME CTT has 60 tokens of the 'heo/hi(e)' type across only 7 texts. If one includes hi(e) spellings for IT ($/P13OdI) showing survival of feminine grammatical gender in inanimates, the total rises to 77 tokens across 14 texts. Only 2 texts (with 3 tokens between them) have 'heo/hie' exclusively in direct object function for HER. The other 5 texts show 'her/hir' types beside 'heo/hie' types. Against this are 494 tokens of the 'her/hir' type for HER found across 51 texts. Or, if one includes 'her/hir' type spellings for IT showing the survival of grammatical gender, the total rises to 590 across 58 texts.

要するに,対格の与格方向への水平化は,意外と早く初期中英語期の段階ですでに相当に進んでいたということになる.おそらく単数男性や複数でも似たような状況だったと想像されるが,これについては別に裏を取る必要がある.

この問題と関連して関連して,「#155. 古英語の人称代名詞の屈折」 ([2009-09-29-1]),「#975. 3人称代名詞の斜格形ではあまり作用しなかった異化」 ([2011-12-28-1]),「#4080. なぜ she の所有格と目的格は her で同じ形になるのですか?」 ([2020-06-28-1]) を参照.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow