2015-09-21 Mon

■ #2338. 16世紀,hem, 'em 不在の謎 (2) [personal_pronoun][emode][corpus][eebo][punctuation][apostrophe]

昨日の記事 ([2015-09-20-1]) に引き続いての話題.16世紀に hem, 'em が不在,あるいは非常に低頻度という件について,EEBO (Early English Books Online) のテキストデータベースを利用して,簡易検索してみた.検索結果は,動詞 hem を含め,相当の雑音が混じっており,丁寧に除去する手間は取っていないものの,16世紀からの例は確かに極端に少ないことがわかった.

16世紀前半からの明確な例は,Andrew Boorde, The pryncyples of astronamye (1547) に現われる "doth geue influence to hem the which be borne vnder this signe" の1例のみである.16世紀前半の300万語ほどのサブコーパスのなかで,極めて珍しい.'em に至っては,16世紀後半のサブコーパスも含めても例がない.

16世紀後半のサブコーパスでも,hem の例は少々現われるとはいえ,さして状況は変わらない.F. T., The debate betweene Pride and Lowlines (1577) なるテキストにおいて "for they doon hem blame", "For which hem thinketh they should been aboue" などと生起したり,Joseph Hall, Certaine worthye manuscript poems of great antiquitie reserued long in the studie of a Northfolke gentleman (1597) という当時においても古めかしい詩のなかで何度か現われたりする程度である.

一方,17世紀サブコーパスの検索結果一覧をざっと眺めると,hem の頻度が著しく増えたという印象はないが,'em が見られ始め,ある程度拡張している様子である.後者の 'em の出現は,アポストロフィという句読記号自体の拡大が17世紀にかけて進行したことと関係するだろう (see 「#582. apostrophe」 ([2010-11-30-1])) .

hem, 'em の歴史的継続性という議論については,問題の16世紀にもかろうじて用例が文証されるということから,継続性を認めてよいだろうとは考える.口語ではもっと頻繁に用いられていただろうという推測も,おそらく正しいだろう.しかし,なぜ文章の上にほとんど反映されなかったのかという疑問は残るし,17世紀以降に復活してきた際に,すでに共時的には them の省略形と解釈されていた可能性についてどう考えるかという問題も残る.この話題は,いまだ謎といってよい.

2015-09-20 Sun

■ #2337. 16世紀,hem, 'em 不在の謎 (1) [personal_pronoun][emode][apostrophe]

「#2331. 後期中英語における3人称複数代名詞の段階的な th- 化」 ([2015-09-14-1]) の最後で触れたように,古い3人称複数代名詞の与格に由来する hem あるいはその弱形 'em は,標準英語では1500年頃までに them によりほぼ置換された.しかし,16世紀末以降,口語的な響きをもって再び文献に現われ出す.'em は,現在の口語の I got 'em. にみられるように,いまだその痕跡を残しているといわれるが,古英語や中英語から現代英語にいたる歴史的継続性を主張するためには,16世紀中の証拠の不在が問題となりそうだ.Wyld (327--28) がこの問題に触れている.

The history of hem is rather curious. It survives in constant use among nearly all writers during the fifteenth century, often alongside the th- form. I have not noted any sixteenth-century example of it in the comparatively numerous documents I have examined, until quite at the end of the century. It reappears, however, in Marston and Chapman early in the seventeenth century, and in the form 'em occurs, though sparingly, in the Verney Mem. towards the end of the seventeenth century, where the apostrophe shows that already it was thought to be a weakened form of them. During the eighteenth century 'em becomes fairly frequent in printed books, and it is in common use to-day as [əm]. It is rather difficult to explain the absence of such forms as hem or em in the sixteenth century, since the frequency at a later period seems to show that, at any rate, the weak form without the aspirate must have survived throughout. The explanation must be that em, though commonly used, was felt, as now, to be merely a form of them.

Wyld は,16世紀中も hem, 'em は口語として続いていたはずだが,すでに them の(崩れた)略形として理解されており,文章の上に反映される機会がなかったのだろうという意見だ.

この仮説を裏付ける証拠はある.Wyld は16世紀からの用例が世紀末を除けば皆無としているが,OED の 'em, pron. の歴史的な例文を眺めると,語幹母音の揺れを無視すれば,hem や 'em の類いは,確かに少ないものの,いくつかは文証される.

・ a1525 (a1500) Sc. Troy Bk. (Douce) 143 in C. Horstmann Barbour's Legendensammlung (1882) II. 233 A ferlyfule sowne sodeynly Among heme maide was hydwisly.

・ a1525 Eng. Conquest Ireland (Trin. Dublin) (1896) 28 He bad ham well þorwe that thay sholden yn al manere senden after more of har kyn.

・ c1540 (?a1400) Gest Historiale Destr. Troy (2002) f. 66, Sotly hyt semys not surfetus harde No vnpossibill thys pupull perfourme in dede That fyuetymes fewer before home has done.

・ 1579 Spenser Shepheardes Cal. May 27 Tho to the greene Wood they speeden hem all.

・ 1589 'M. Marprelate' Hay any Worke for Cooper 48 Ile befie em that will say so of me.

しかし,歴史的連続性を主張するのに首の皮が一枚つながったという程度で,16世紀からの用例は確かに著しく少ないようである.口語的な語形として文章に反映される機会がなかったという点についても,もう少し掘り下げて考える必要がありそうだ.

なお,18世紀初めに,Swift が 'em をだらしない語法として非難していることを付け加えておこう.Wyld (329) 曰く,

Note that this form ['em] became so widespread in the early eighteenth-century speech that Swift complains that 'young readers in our churches in the prayer for the Royal Family, say endue'um, enrich'um, prosper'um, and bring'um. Tatler, No. 230 (1710).

・ Wyld, Henry Cecil. A History of Modern Colloquial English. 3rd ed. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1936.

2015-09-14 Mon

■ #2331. 後期中英語における3人称複数代名詞の段階的な th- 化 [personal_pronoun][paradigm][case][ormulum]

3人称複数代名詞が,中英語期中に,本来語の h- 形から古ノルド語由来とされる th- 形へと置き換えられていったことは,英語史では広く知られている.しかし,th- への置換は,格によってタイミングが異なっていた (see 「#975. 3人称代名詞の斜格形ではあまり作用しなかった異化」 ([2011-12-28-1]), 「#1843. conservative radicalism」 ([2014-05-14-1])) .すべての方言で繰り返されたパターンは,まず主格が,次に属格が,最後に斜格(与格と対格の融合したもの)が th- 形へ移行するというパターンだ.例えば,北東中部方言の Ormulum (?c1200) では,すでに早い段階で主格は þeȝȝ 一辺倒になっており,属格でも多少の h- 形を残しながらも大部分は þeȝȝre だが,斜格では逆に多少の þeȝȝm を示しながらも hemm が基本である.

ロンドンで主格に þei が現われるのは14世紀であり,Chaucer では þei / her(e) / hem というパラダイムが用いられている (「#181. Chaucer の人称代名詞体系」 ([2009-10-25-1])) .15世紀になると,属格で their が her(e) と競合するようになり,世紀末には Caxton などで their が事実上の唯一形となる.them の定着は最も遅く,Chaucer の次世代の Lydgate や Hoccleve でもまだ hem のみであり,Caxton では them が現われるものの,いまだ hem のほうが優勢だった.16世紀の初めになって,ようやく them が定着し,現代標準英語の状況に達することになった (Lass 120; Mustanoja 134--35) .

したがって,3人称複数のパラダイムは,いずれの方言においても,絶対年代こそ異なれ,共通して以下の3段階を経たことになる (Lass 121).

| I | II | III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | þei | þei | þei |

| Genitive | her(e) | her(e) ? þeir | þeir |

| Oblique | hem | hem | hem ? þem |

th- に最後まで抵抗していた hem については,後日談がある.hem は上記のように1500年頃までに標準的な英語では them に完全に置換されたといってよいが,口語では18世紀前半まで主として 'em の形で残っていた形跡があり,それは現在の口語における 'em に連なるのである(荒木・宇賀治,p. 181).以下の例を参照.

・ Let 'em enter (Jul. Caes.)

・ let 'em say what they will (Beaumont & Fletcher, The Famous Historie)

・ I designed to carry 'em, name 'em (The Tatler)

・ 't was time to part 'em, reconcile 'em (Swift, A Complete Collection of Genteel and Ingenious Conversation)

・ I laid 'em up (Defoe, Robinson Crusoe)

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 2. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 23--154.

・ 荒木 一雄,宇賀治 正朋 『英語史IIIA』 英語学大系第10巻,大修館書店,1984年.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2015-09-05 Sat

■ #2322. I have no money with me. の me [reflexive_pronoun][personal_pronoun][preposition]

現代英語において,主語と同一の指示対象を指す代名詞は,通常の単純形の代名詞ではなく -self を伴う再帰代名詞の形態をとらなければならないというのが規則である.しかし,ときに単純代名詞と再帰代名詞の選択が任意という場合がある.位置を表わす前置詞の目的語として用いられるケースで,Quirk et al. (359) によれば,次のような例が挙げられる.

・ She's building a wall of Russian BÒOKS about her(self).

・ Holding her new yellow bathrobe around her(self) with both arms, she walked up to him.

・ Mason stepped back, gently closed the door behind him(self), and walked down the corridor.

・ They left the apartment, pulling the spring lock shut behind them(selves).

さらに,主語と同一指示対象でありながら,単純形が任意どころか義務という場合すらある.やはり前置詞の目的語として用いられる場合で,標題の文に代表される.Quirk et al. (360) では,次のような例文が挙げられている.

・ He looked about him.

・ She pushed the cart in front of her.

・ She liked having her grandchildren around her.

・ They carried some food with them.

・ Have you any money on you?

・ We have the whole day before us.

・ She had her fiancé beside her.

歴史的にみれば,これらの単純形も機能的には歴とした再帰代名詞である.歴史的背景を略述すれば,初期近代英語までは,動きや静止を表わす自動詞 (ex. fare, go, run; rest, sit, stay) や感情を表わす他動詞 (ex. doubt, dread, fear, repent) は,単純形の再帰代名詞を伴うのが普通だった.しかし,17世紀にはこの語法は衰退し,単純形の再帰代名詞は廃用となっていった(中尾・児馬,p. 36).関連して,「#578. go him」 ([2010-11-26-1]),「#1392. 与格の再帰代名詞」 ([2013-02-17-1]),「#2185. 再帰代名詞を用いた動詞表現の衰退」 ([2015-04-21-1]) も参照.

このように単純形が衰退するなかで,唯一取り残されて生き延びたのが,上掲の事例である.生き残った理由としては,問題の代名詞に強調や対比の意味がこめられておらず,形態的にも短いものが好まれたということが考えられる.これらの例文において強調されているのは,むしろ前置詞のほうだろう.このことは,"Pat felt a sinking sensation inside (her)." のように,問題の代名詞が省略される場合すらあることからも推測される.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

・ 中尾 俊夫・児馬 修(編著) 『歴史的にさぐる現代の英文法』 大修館,1990年.

2015-09-03 Thu

■ #2320. 17世紀中の thou の衰退 [honorific][politeness][personal_pronoun][t/v_distinction][emode][pragmatics]

英語史における thou と you の使い分け,いわゆる T/V distinction の問題については,「#1126. ヨーロッパの主要言語における T/V distinction の起源」 ([2012-05-27-1]) や「#1127. なぜ thou ではなく you が一般化したか?」 ([2012-05-28-1]),そして t/v_distinction の各記事で取り上げてきた.

2人称複数代名詞の敬称単数としての用法の伝統は,4世紀のローマ皇帝に対する vos の使用に始まり,12世紀の Chrétien de Troyes などによるフランス語を経て,英語へはおそらく13世紀に伝わり,1600年頃には慣用として根付いていた.一方,17世紀中に親称単数の thou は衰退し始め,標準英語では18世紀に廃用となった.Johnson (261) が,上記の歴史的経緯を実に手際よくまとめているので,そのまま引用したい.

IN LATIN THE EMPEROR, representing in his person the power and glory of his predecessors, was addressed with vos in the fourth century A.D. By the fifth century, this pronoun was commonly employed to indicate respect. In French by the time of Chrétien de Troyes, vous was not only given to superiors but was also interchanged by equals. In Latin and French works of twelfth-century England, the plural pronoun had been used as a singular by, for example, Geoffrey of Monmouth, Wace, and Marie de France. The practice of using ye and you (the "you-singular") instead of thou and thee (the "thou-singular") apparently spread to English during the thirteenth century and by about 1600 had become established in polite usage. For some time thereafter, however, the thou-singular continued to appear in emotional or intimate speech and in the discourse of superiors to inferiors and of the members of the lower class to one another. Gradually decreasing in use, it became obsolete in the standard language in the eighteenth century and now appears only in poetry and the address of the deity or among Quakers and those who speak a dialect.

Johnson は,thou の衰退する17世紀に焦点を当て,喜劇の戯曲と大衆フィクションの47作品をコーパスとして,you と thou の分布と頻度を調査した.登場人物を職業別に上流,中流,下流へ分類し,以下のような統計結果を得た (Johnson 265).

| 1600--1649 | You | Thou | You* | Thou* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Class | 5,851 | 2,664 | 64.36 | 35.64 |

| Middle Class | 2,807 | 629 | 81.40 | 18.60 |

| Lower Class | 2,385 | 470 | 83.47 | 16.53 |

| 1650--1699 | ||||

| Upper Class | 10,853 | 2,353 | 81.40 | 18.60 |

| Middle Class | 3,145 | 574 | 81.77 | 18.23 |

| Lower Class | 2,849 | 317 | 88.32 | 11.68 |

| * In percent. |

17世紀前半の上流階級にあっては多少の使い分けが残っているが,他の階級,あるいは少なくとも世紀の後半には thou の使用は目立たなくなっている.この段階で使い分けがなくなったというのは性急であり,伝統的な語用論的な機微がいまだ残っている例も確かに散見されるが,一方で特別な機微の感じられない you や thou の用法もあることから,両者の機能的な対立が解消しつつあったことが推測される.Johnson (266) 曰く,

The historical uses of the you-singular, as in respect or irony, and of the thou-singular, as in emotion or intimacy, to an inferior, or in the exchange of the members of the lower class, are exemplified in the various texts throughout the era. However, further demonstrating the meaninglessness of the distinction between them, you may frequently be found in circumstances where thou might be expected to occur, and, at times, thou where we should expect to find you.

・ Johnson, Anne Carvey. "The Pronoun of Direct Address in Seventeenth-Century English." American Speech 41 (1966): 261--69.

2015-08-27 Thu

■ #2313. 不定人称代名詞としての thou [personal_pronoun][pragmatics][indefinite_pronoun][pronoun][generic]

「#2248. 不定人称代名詞としての you」 ([2015-06-23-1]) で取り上げた話題と関連して,古い2人称代単数代名詞 thou が不定の一般的な人を指示する用法を発達させたのはいつかという問題を取り上げる.先の記事でも触れたように,OED では thou についてそのような語義分類がなされておらず,確かなことは言えないが,MED では様々な例文が列挙されている.最も古い例として挙げられているのは,古英語末期といってもよい次の文である.a1150 (OE) Vsp.D.Hom. (Vsp D.14) 3/18: Þonne þu oðerne mann tæle, þonne geðænc þu þæt nan man nis lehterleas.

ほぼ同じくらい早い例として,?a1160 Peterb. Chron. (LdMisc 636) an. 1137: Hi..brendon alle the tunes ðæt wel þu myhtes faren all a dæis fare sculdest thu neure finden man in tune sittende ne land tiled. が挙げられているが,この例文ついては,古い論文だが Koziol (173) が言及している.

Die Bedeutung des thou in Sprichwörtern und allgemeinen Regeln kommt einem »man« zumindest sehr nahe; es wendet sich nicht an einen bestimmten Menschen, sondern an jeden. Im Neuenglischen ist ja der entsprechende Gebrauch von you (oder they) sehr häufig. Daß früher thou die gleiche allgemeine Bedeutung haben konnte, geht aus Stellen wie der folgenden aus der Sachsenchronik 1137 hervor: hi . . . brendon alle the tunes, đ wel þu myhtes faren al a dæis fare, sculdest thu neure finden man in tune sittende. N. Bøgholm führt außer diesem noch ein Beispiel aus altenglischer Zeit an. Das OED verzeichnet diesen Gebrauch nicht.

上の引用によれば,さらに古英語からの例がありそうだということだが,2人称代名詞への不定一般人称への用法上の拡張は語用論的には突飛ではなく,驚くことではないだろう.同じ拡張が歴史時代以前に起こっていたという可能性すらあり得るだろう.ただし,文献学的には,初例がいつどこで文証されたのかということは問題になる.同用法の起源・発達の問題は残るが,現在も普通に用いられる2人称代名詞の不定人称を表わす用法が,遅く見積もったとしても古英語から中英語にかけての時期にすでに確認されたという事実に,歴史の長さと語用論的な普遍性の一端をみることができる.

・ H. Koziol, "Die Anredeform bei Chaucer." Englische Studien 75 (1942): 170--74.

2015-08-23 Sun

■ #2309. 動詞の人称語尾の起源 [category][person][verb][inflection][personal_pronoun][agreement][linguistic_relativism]

本ブログでは3単現の -s (3sp) や3複現の -s (3pp) ほか,英語史における動詞の人称語尾に関する話題を多く取り上げてきた.人称 (person) という文法範疇 (category) は世界の多くの語族に確認され,英語を含む印欧諸語においても顕著な範疇となっている.しかし,そもそも印欧語において人称が動詞の屈折語尾において標示されるという伝統の起源は何だったのだろうか.主語の人称と動詞が一致しなければならないという制約はどこから来たのだろうか.

この問題について,印欧語比較言語学では様々な議論が繰り広げられているようだ.この分野の世界的大家の1人 Szemerényi (329) によれば,1・2人称語尾については,対応する人称代名詞の形態が埋め込まれていると考えて差し支えないという.

The question of the origin of the personal endings has always aroused much greater interest. Since Bopp's earliest writings, indeed since the eighteenth century, it has been usual to find in the personal endings the personal pronouns. In spite of frequent dissent this theory is universally accepted; it is, however, also valid for the 1st pl., where the original form of the pronoun was *mes . . ., and for the 1st dual, whose ending -we(s) similarly contains the pronoun. And the principle must be expected to operate in the 2nd person also. This is suggest by many other language families. . . .

一方,3人称については,1・2人称と同様の説明を与えることはできず,単数にあっては指示詞 *so/*to に由来し,複数にあっては動作主名詞接尾辞と関係し,やや複雑な事情を呈するという (Szemerényi 330) .これが事実だとすると,太古の印欧祖語の話者は,1・2人称を正当な「人称」とみて,3人称を「非人称」とみていたのかもしれない.ここに反映されている世界観(と屈折語尾の分布)は現代の印欧諸語の多くに痕跡を残しており,屈折語尾の著しく衰退した現代英語にすら,3単現の -s としてかろうじて伝わっている.

では,そもそも印欧語において人称という文法範疇が確たる地位を築いてきたのはなぜか.というのは,他の多くの言語では,人称という文法範疇はたいした意味をもたないからだ.例えば,日本語では形容詞の用法における人称制限などが問題となる程度であり,範疇としての人称の存在基盤は薄い.しかし,人称という術語の指し示すものをもっと卑近に理解すれば,それは話す主体としての「私」と,私の話しを聞いている「あなた」と,話題となりうる「それ以外」の一切の素材とを区別する原理にほかならない.「#1070. Jakobson による言語行動に不可欠な6つの構成要素」 ([2012-04-01-1]) の用語でいえば,話し手(=1人称),聞き手(=2人称),事物・現象(=3人称)という区分である.これらが普遍的な構成要素のうちの3つであるということが真であれば,いかなる言語も,この区分をどの程度確たる文法範疇として標示するかは別として,その基本的な世界観を内包しているはずである.印欧祖語は,それを比較的はっきり標示するタイプの言語だったのだろう.

なお,前段落の議論は,ある種の言語普遍性 (linguistic universal) を前提とした議論である.だが,日本語母語話者としては,人称という文法範疇は直感的によく分からないのも事実であるから,言語相対論 (linguistic_relativism) として理解したい気もする.

・ Szemerényi, Oswald J. L. Introduction to Indo-European Linguistics. Trans. from Einführung in die vergleichende Sprachwissenschaft. 4th ed. 1990. Oxford: OUP, 1996.

2015-06-23 Tue

■ #2248. 不定人称代名詞としての you [personal_pronoun][proverb][register][sobokunagimon][indefinite_pronoun][pronoun][generic]

6月3日付けで寄せられた素朴な疑問.不定人称代名詞として people や one ほどの一般的な指示対象を表わす you の用法は,歴史的にいつどのように発達したものか,という質問である.現代英語の例文をいくつか挙げよう.

・ You learn a language better if you visit the country where it is spoken.

・ It's a friendly place---people come up to you in the street and start talking.

・ You have to be 21 or over to buy alcohol in Florida.

・ On a clear day you can see the mountains from here.

・ I don't like body builders who are so overdeveloped you can see the veins in their bulging muscles.

まずは,OED を見てみよう.you, pron., adj., and n. によれば,you の不定代名詞としての用法は16世紀半ば,初期近代英語に遡る.

8. Used to address any hearer or reader; (hence as an indefinite personal pronoun) any person, one . . . .

c1555 Manifest Detection Diceplay sig. D.iiiiv, The verser who counterfeatith the gentilman commeth stoutly, and sittes at your elbowe, praing you to call him neare.

当時はまだ2人称単数代名詞として thou が生き残っていたので,OED の thou, pron. and n.1 も調べてみたが,そちらでは特に不定人称代名詞としての語義は設けられていなかった.

中英語の状況を当たってみようと Mustanoja を開くと,この件について議論をみつけることができた.Mustanoja (127) は,thou の不定人称的用法が Chaucer にみられることを指摘している.

It has been suggested (H. Koziol, E Studien LXXV, 1942, 170--4) that in a number of cases, especially when he seemingly addresses his reader, Chaucer employs thou for an indefinite person. Thus, for instance, in thou myghtest wene that this Palamon In his fightyng were a wood leon) (CT A Kn. 1655), thou seems to stand rather for an indefinite person and can hardly be interpreted as a real pronoun of address.

さらに本格的な議論が Mustanoja (224--25) で繰り広げられている.上記のように OED の記述からは,この用法の発達が初期近代英語のものかと疑われるところだが,実際には単数形 thou にも複数形 ye にも,中英語からの例が確かに認められるという.初期中英語からの 単数形 thou の例が3つ引かれているが,当時から不定人称的用法は普通だったという (Mustanoja 224--25) .

・ wel þu myhtes faren all a dæis fare, sculdest thu nevre finden man in tune sittende, ne land tiled (OE Chron. an. 1137)

・ no mihtest þu finde (Lawman A 31799)

・ --- and hwat mihte, wenest tu, was icud ine þeos wordes? (Ancr. 33)

中英語期には単数形 thou の用例のほうが多く,複数形 ye あるいは you の用例は,これらが単数形 thou を置換しつつあった中英語末期においても,さほど目立ちはしなかったようだ.しかし,複数形 ye の例も,確かに初期中英語から以下のように文証される (Mustanoja 225) .

・ --- þenne ȝe mawen schulen and repen þat ho er sowen (Poema Mor. 20)

・ --- and how ȝe shal save ȝowself þe Sauter bereth witnesse (PPl. B ii 38)

・ --- ȝe may weile se, thouch nane ȝow tell, How hard a thing that threldome is; For men may weile se, that ar wys, That wedding is the hardest band (Barbour i 264)

なお,MED の thou (pron.) (1g, 2f) でも yē (1b, 2b) でも,不定人称的用法は初期中英語から豊富に文証される.例文を参照されたい.

本来聞き手を指示する2人称代名詞が,不定の一般的な人々を指示する用法を発達させることになったことは,それほど突飛ではない.ことわざ,行儀作法,レシピなどを考えてみるとよい.これらのレジスターでは,発信者は,聞き手あるいは読み手を想定して thou なり ye なりを用いるが,そのような聞き手あるいは読み手は実際には不特定多数の人々である.また,これらのレジスターでは,内容の一般性や普遍性こそが身上であり,とりあえず主語などとして立てた thou や ye が語用論的に指示対象を拡げることは自然の成り行きだろう.例えばこのようなレジスターから出発して,2人称代名詞がより一般的に不定人称的に用いられることになったのではないだろうか.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2015-06-10 Wed

■ #2235. 3文字規則 [spelling][orthography][final_e][personal_pronoun][three-letter_rule]

現代英語の正書法には,「3文字規則」と呼ばれるルールがある.超高頻度の機能語を除き,単語は3文字以上で綴らなければならないというものだ.英語では "the three letter rule" あるいは "the short word rule" といわれる.Jespersen (149) の記述から始めよう.

4.96. Another orthographic rule was the tendency to avoid too short words. Words of one or two letters were not allowed, except a few constantly recurring (chiefly grammatical) words: a . I . am . an . on . at . it . us . is . or . up . if . of . be . he . me . we . ye . do . go . lo . no . so . to . (wo or woe) . by . my.

To all other words that would regularly have been written with two letters, a third was added, either a consonant, as in ebb, add, egg, Ann, inn, err---the only instances of final bb, dd, gg, nn and rr in the language, if we except the echoisms burr, purr, and whirr---or else an e . . .: see . doe . foe . roe . toe . die . lie . tie . vie . rye, (bye, eye) . cue, due, rue, sue.

4.97 In some cases double-writing is used to differentiate words: too to (originally the same word) . bee be . butt but . nett net . buss 'kiss' bus 'omnibus' . inn in.

In the 17th c. a distinction was sometimes made (Milton) between emphatic hee, mee, wee, and unemphatic he, me, we.

2文字となりうるのは機能語がほとんどであるため,この規則を動機づけている要因として,内容語と機能語という語彙の下位区分が関与していることは間違いなさそうだ.

しかし,上の引用の最後で Milton が hee と he を区別していたという事実は,もう1つの動機づけの可能性を示唆する.すなわち,機能語のみが2文字で綴られうるというのは,機能語がたいてい強勢を受けず,発音としても短いということの綴字上の反映ではないかと.これと関連して,off と of が,起源としては同じ語の強形と弱形に由来することも思い出される (cf. 「#55. through の語源」 ([2009-06-22-1]),「#858. Verner's Law と子音の有声化」 ([2011-09-02-1]),「#1775. rob A of B」 ([2014-03-07-1])) .Milton と John Donne から,人称代名詞の強形と弱形が綴字に反映されている例を見てみよう (Carney 132 より引用).

so besides

Mine own that bide upon me, all from mee

Shall with a fierce reflux on mee redound,

On mee as on thir natural center light . . .

Did I request thee, Maker, from my Clay

To mould me Man, did I sollicite thee

From darkness to promote me, or here place

In this delicious Garden?

(Milton Paradise Lost X, 737ff.)

For every man alone thinkes he hath got

To be a Phoenix, and that then can bee

None of that kinde, of which he is, but hee.

(Donne An Anatomie of the World: 216ff.)

Carney (133) は,3文字規則の際だった例外として <ox> を挙げ (cf. <ax> or <axe>),完全無欠の規則ではないことは認めながらも,同規則を次のように公式化している.

Lexical monosyllables are usually spelt with a minimum of three letters by exploiting <e>-marking or vowel digraphs or <C>-doubling where appropriate.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. 1954. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

2015-06-09 Tue

■ #2234. <you> の綴字 [personal_pronoun][spelling][orthography][pronunciation]

「#2227. なぜ <u> で終わる単語がないのか」 ([2015-06-02-1]) では,きわめて例外的な綴字としての <you> について触れた.原則として <u> で終わる語はないのだが,この最重要語は特別のようである.だが,非常に関連の深いもう1つの語も,同じ例外を示す.古い2人称単数代名詞 <thou> である.俄然この問題がおもしろくなってきた.関係する記述を探してみると,Upward and Davidson (188) が,これについて簡単に触れている.

OU and OW have become fixed in spellings mainly according to their position in the word, with OU in initial or medial positions before consonants . . . .

・ OU is nevertheless found word-finally in you and thou, and in some borrowings from or via Fr: chou, bayou, bijou, caribou, etc.

・ The pronunciation of thou arises from a stressed form of the word; hence OE /uː/ has developed to /aʊ/ in the GVS. The pronunciation of you, on the other hand, derives from an unstressed form /jʊ/, from which a stressed form /juː/ later developed.

Upward and Davidson にはこれ以上の記述は特になかったので,さらに詳しく調査する必要がある.共時的にみれば,*<yow> と綴る方法もあるかもしれないが,これは綴字規則に照らすと /jaʊ/ に対応してしまい都合が悪い.<ewe> や <yew> の綴字は,すでに「雌山羊」「イチイ」を意味する語として使われている.ほかに,*<yue> のような綴字はどうなのだろうか,などといろいろ考えてみる.所有格の <your> は語中の <ou> として綴字規則的に許容されるが,綴字規則に則っているのであれば,対応する発音は */jaʊə/ となるはずであり,ここでも問題が生じる.謎は深まるばかりだ.

上の引用でも触れられている you の発音について,より詳しくは「#2077. you の発音の歴史」([2015-01-03-1]) を参照.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2015-05-20 Wed

■ #2214. this, that が単独で人を指しにくい歴史的理由 [gender][deixis][gender][demonstrative][personal_pronoun][semantics]

現代英語では,指示代名詞である this, that, these, those は各々単独で,人を指示することができる.しかし,単数系列にはある特徴がある.単数の this, that が単独で人を指す場合には,原則として軽蔑的な含意がこめられるというのだ(本記事では,This is John. のような人を紹介する文脈での用法は除くものとする).この用法に関心を示した Poussa (401) は,that のこの用法の初例として OED から1905年の例文を引いている.

'Would you like to marry Malcolm?' I asked. 'Fancy being owned by that! Fancy seeing it every day!' (Eleanor Glynn, Vicissitudes of Evangeline: 127).

Poussa は,このような that(や this)の用法を,英語史上,比較的最近になって現われたものとし,社会的直示性を示す "comic-dishonourific" な用法と呼んだ.20世紀初頭ではこの用法はまだほとんど気づかれていなかったようで,例えば Jespersen (406) は,this と that がそもそも単独で人を表わす用法はないと述べている.

While in the adjunctal function the plural forms these and those correspond exactly to the singulars this and that, the same cannot be said with regard to the same forms used as principals, for here this and that can no longer be used in speaking of persons, while these and those can. The sg of those who is not that who (which is not used), but he who (she who); similarly there is no sg that present corresponding to the pl those present

元来 this, that が単独で人を指示することができなかったことと,新しい用法として人を指せるようにはなったものの,そこに否定的な社会的直示性が含意されていることとは,無関係ではないだろう.this, that が単独で人を指すのには,いまだ何らかの抵抗感があるものと思われる.

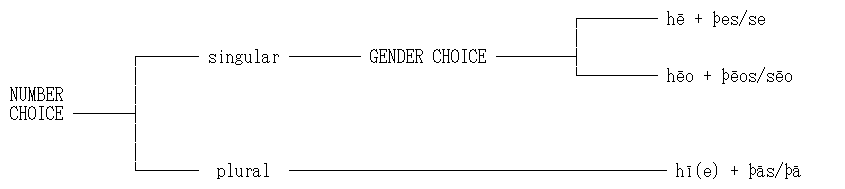

しかし,さらに古く歴史を遡ると,古英語でも中英語でも,this, that は,確かに頻繁ではないものの,複数形の these, those とともに単独で人を指すことができたのである (Jespersen 409--10) .ここで,単独で人を指す this, that のかつての用法が,なぜ現代英語の直前期までに一旦消えることになったのかという,別の問題が持ち上がることになる.

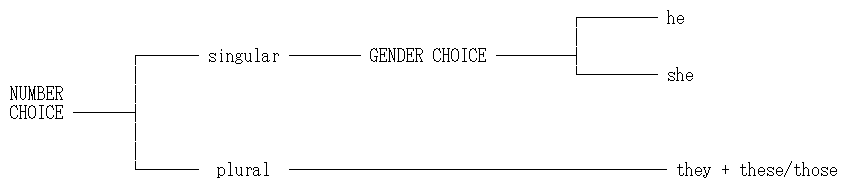

Poussa は,gender という意外な観点を持ち出して,この問題に迫った.3人称代名詞が単数系列では he, she と男女を区別し,複数系列では区別せずに共通して they を用いる事実と,指示代名詞の分布を関係づけたのである.

上の図 (Poussa 405) に示したように,もとより性を区別しない複数系列では,人称代名詞の they はもちろん,指示代名詞 these, those も単独で人を指すことができるが,単数系列では性を区別できる人称代名詞 he, she のみが可能で,性を区別できない指示代名詞 this, that を用いることはできない.単数系列では,this, that は性を区別することができないがゆえに,その生起がブロックされるというわけだ.このことは,文法性として男性と女性を区別していた古英語の分布図 (Poussa 407) と比較すると,より明らかになる.

古英語では,単数系列で指示代名詞が男性と女性を区別しえたために,単独で人を指すことも問題なく許容されたと解釈できる.後世の観点からすると,いまだ [-HUMAN] の意味特性を獲得していないということができる.

Poussa は,近現代英語につらなる "HUMAN" という意味特性の発生は,古英語から中英語にかけての文法性の体系の崩壊と関連して生じたものであり,指示体系の新たな原理の創出の反映であるとみている.初期近代英語における his に代わる its の発展や,関係代名詞 which と who の先行詞選択の発達も,同じ新しい原理に依拠しているといえるだろう (cf. 「#198. its の起源」 ([2009-11-11-1]),「#1418. 17世紀中の its の受容」 ([2013-03-15-1])) .

Poussa の議論を受け入れるとすれば,後期古英語からの音声変化によって文法性の体系が崩れ,中英語期に形態論と統語論を劇的に変化させることとなったが,さらに近代英語期以降に,その余波が意味論や語用論にも及んできたということになる.英語史の壮大なドラマを感じざるを得ない.

・ Poussa, Patricia. "Pragmatics of this and that." History of Englishes: New Methods and Interpretations in Historical Linguistics. Ed. Matti Rissanen, Ossi Ihalainen, Terttu Nevalainen, and Irma Taavitsainen. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1992. 401--17.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 2. Vol. 1. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: C. Winter's Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1922.

2015-05-13 Wed

■ #2207. 再帰代名詞を用いた動詞表現の衰退 (3) [reflexive_pronoun][verb][personal_pronoun][passive][voice]

「#2185. 再帰代名詞を用いた動詞表現の衰退」 ([2015-04-21-1]) と「#2206. 再帰代名詞を用いた動詞表現の衰退 (2)」 ([2015-05-12-1]) に引き続いての話題.近代英語期以降,再帰代名詞を伴う動詞の表現が衰退してきている.この現象を関連表現との競合という観点から調査した研究に,秋元 (118--48) がある.秋元は,content oneself with などの「動詞+再帰代名詞+前置詞」というパターンとその関連表現に的を絞って,OED から1700年以降の用例を収集し,それぞれの分布を取った.

content oneself with でいえば,このパターンは現代英語では減少してきており,代わって各種の競合形,とりわけ be content to V や be content with NP が増えてきているという.be contented with NP や be contented to V という競合形も低頻度ながら用いられており,全体として再帰代名詞を用いた表現は各種の競合形に抑えこまれる形で目立たなくなってきているという.content oneself with のほかにもいくつかの表現が扱われており,例えば apply oneself to もやはり着実に減少してきており,代わって自動詞用法の apply to NP や受動態の be applied to NP が増えてきているようだ.8種類の動詞について用例数を数え挙げた結果は,以下の通りである(秋元,p. 134) .時代別ではなくひっくるめた数値だが,再帰表現ではない競合形が相対的に優勢であることがよくわかる.

| reflexive | passive | intransitive | other rival forms | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | content oneself with | 108 | 30 | 136 | |

| (2) | avail oneself of | 14 | 4 | ||

| (3) | devote oneself to | 70 | 191 | ||

| (4) | apply oneself to | 42 | 653 | 548 | |

| (5) | attach oneself to | 93 | 100 | 171 | |

| (6) | address oneself to | 62 | 207 | 11 | |

| (7) | confine oneself to | 69 | 592 | ||

| (8) | concern oneself with/about/in | 69 | 822 |

概して再帰代名詞を用いた表現は確かに頻度が低くなってきているが,その背後には受動態その他の競合形の躍進というもう一つの言語変化が関与しているということだろう.

・ 秋元 実治 『増補 文法化とイディオム化』 ひつじ書房,2014年.

2015-05-12 Tue

■ #2206. 再帰代名詞を用いた動詞表現の衰退 (2) [reflexive_pronoun][verb][personal_pronoun][voice]

「#2185. 再帰代名詞を用いた動詞表現の衰退」 ([2015-04-21-1]) を受けて,少し調べてみたことを報告する.Jespersen に当たってみたが,前回の記事を書いたときにおぼろげに考えていたことが,Jespersen の発言に裏付けられたような気がした.-self 形の再帰代名詞の音韻形態的な重さという問題に加え,me や him などの単純形再帰代名詞の意味的な軽さ,あるいは "dative of interest" の用法 (cf. 「#980. ethical dative」 ([2012-01-02-1])) としての異分析が関与しているのではないかという説だ.少々長いが,分かりやすい説明なので引用しよう (Jespersen 325) .

Omission of Reflexive Pronouns

16.21. In a great many cases the verb as used intransitively represents an older reflexive verb. The change of construction may have been brought about in two ways. In the older stages of the language the ordinary personal pronoun was used in a reflexive sense, but me in I rest me, originally in the accusative (he hine reste), might easily be felt as representing a 'dative of interest' (cf I buy me a hat, etc.) and thus be discarded as really superfluous. In the second place, after the self-pronouns had come to be generally used, the reflexive object in I dress myself might be taken to be the empathic pronoun in apposition to the nominative (the difference in stress not being always strictly maintained) and thus might easily appear superfluous. The tendency is towards getting rid of the cumbersome self-pronoun whenever no ambiguity is to be feared; thus a modern Englishman or American will say I wash, dress, and shave, where his ancestor would add (me, or) myself in each case. One of the reasons for this evolution is evidently the heaviness of the forms myself, ourselves, etc., while there is not the same inducement in other languages to get rid of the short me, se, mich, sich, migh, sig, sja, etc. Hence also the development of the activo-passive use . . . in many cases where other languages have either the reflexive or the passive forms that have arisen out of the reflexive (Scand. -s, Russian -sja, -s.)

この引用の後で,Jespersen は目的語としての再帰代名詞が省略された動詞表現の用例を近代英語期から数多く挙げていくが,例を眺めていると,いかに多くの動詞が現代英語にかけて「自動詞化」してきたかを確認できる.逆にいえば,現代の感覚からは,この表現もあの表現もかつては再帰代名詞を伴っていたのかと驚くばかりだ.ランダムに再帰代名詞を用いた例を抜き出してみる.

・ we bowed our selves towards him (Bacon A 4.34)

・ may I complain my selfe (Sh R 2 I 2.42)

・ they drew themselves more westerly towards the Red sea (Raleigh)

・ I dress my selfe handsome, till thy returne (Sh H 4 B II.4.302)

・ I though it would make me feel myself a boy again, but . . . I never felt so old as I do to-day (Barrie T 65)

・ Both I do repent me and repent it (Sh)

・ [he] retyr'd himselfe To Italy (Sh R 2 IV 1.96)

・ He . . . hath solne him home to bed (Sh Ro II 1.4)

・ Jesus turned him about (AV Matth. 9.22)

・ yeeld thee, coward (Sh Mcb V 8.23)

再帰代名詞の省略と関連して,相互代名詞 (each other, one another) の省略もパラレルな傾向としてみることができる (Jespersen 332) .現在 we meet, we kiss, we marry のように相互的な意味において自動詞として使われ得るが,元来は目的語として each other を伴っていた.embrace, greet, hug などもこの部類に入る.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part III. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1954.

2015-04-21 Tue

■ #2185. 再帰代名詞を用いた動詞表現の衰退 [reflexive_pronoun][verb][personal_pronoun][voice][middle_voice]

フランス語学習者から質問を受けた.フランス語には代名動詞というカテゴリーがあるが,英語にはないのはなぜかという疑問である.具体的には,Ma mere se lève tôt. (私の母は早く起きる)のような文における,se leve の部分が代名動詞といわれ,「再帰代名詞+動詞」という構造をなしている.英語風になおせば,My mother raises herself early. という表現である.普通の英語では rise や get up などの動詞を用いるところで,フランス語では代名動詞を使うことが確かに多い.また,ドイツ語でも Du hast dich gar nicht verändert. (You haven't changed at all) のように「再帰代名詞+動詞」をよく使用し,代名動詞的な表現が発達しているといえる.

このような表現は起源的には印欧祖語の中間態 (middle_voice) の用法に遡り,したがって印欧諸語には多かれ少なかれ対応物が存在する.実際,英語にも help oneself, behave oneself, pride oneself on など再帰代名詞と動詞が構造をなす慣用表現は多数ある.しかし,英語ではフランス語の代名動詞のように動詞の1カテゴリーとして設けるほどには発達していないというのは事実だろう.ここにあるのは,質の問題というよりも量の問題ということになる.英語で再帰代名詞を用いた動詞表現が目立たないのはなぜだろうか.

この疑問に正確に回答しようとすれば細かく調査する必要があるが,大雑把にいえば,英語でも古くは再帰代名詞を伴う動詞表現がもっと豊富にあったということである.「他動詞+再帰代名詞」のみならず「自動詞+再帰代名詞」の構造も古くはずっと多く,後者の例は「#578. go him」 ([2010-11-26-1]) や「#1392. 与格の再帰代名詞」 ([2013-02-17-1]) で見たとおりである.このような構造をなす動詞群には現代仏独語とも比較されるものが多く,運動や姿勢を表わす動詞 (ex. go, return, run, sit, stand, turn) ,心的状態を表わす動詞 (ex. doubt, dread, fear, remember) ,獲得を表わす動詞 (buy, choose, get, make, procure, seek, seize, steal) ,その他 (bear, bethink, rest, revenge, sport, stay) があった.ところが,このような表現は近代英語期以降に徐々に廃れ,再帰代名詞を脱落させるに至った.

現代英語でも再帰代名詞の脱落の潮流は着々と続いている.例えば,adjust (oneself) to, behave (oneself), dress (oneself), hide (oneself), identify (oneself) with, prepare (oneself) for, prove (oneself) (to be), wash (oneself), worry (oneself) などでは,再帰代名詞のない単純な構造が好まれる傾向がある.Quirk et al. (358) は,このような動詞を "semi-reflexive verb" と呼んでいる.

以上をまとめれば,英語も近代期までは印欧祖語に由来する中間態的な形態をある程度まで保持し,発展させてきたが,以降は非再帰的な形態に置換されてきたといえるだろう.英語においてこの衰退がなぜ生じたのか,とりわけなぜ近代英語期というタイミングで生じたのかについては,さらなる調査が必要である.再帰代名詞の形態が -self を常に要求するようになり,音韻形態的に重くなったということもあるかもしれない(英語史において再帰代名詞が -self を含む固有の形態を生み出したのは中英語以降であり,それ以前もそれ以後の近代英語期でも,-self を含まない一般の人称代名詞をもって再帰代名詞の代わりに用いてきたことに注意.「#1851. 再帰代名詞 oneself の由来についての諸説」 ([2014-05-22-1]) を参照).あるいは,単体の動詞に対する統語意味論的な再分析が生じたということもあろう.複合的な視点から迫るべき問題のように思われる.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2015-02-02 Mon

■ #2107. ドイツ語の T/V distinction の略史 [german][politeness][euphemism][t/v_distinction][personal_pronoun][historical_pragmatics][honorific][face][iconicity][solidarity]

英語史における2人称代名詞に関する語用論的問題,いわゆる T/V distinction の発達と衰退の問題は,t/v_distinction のいくつかの記事で取り上げてきた.今回は,高田に拠ってドイツ語の T/V distinction の盛衰の歴史を垣間見たい.

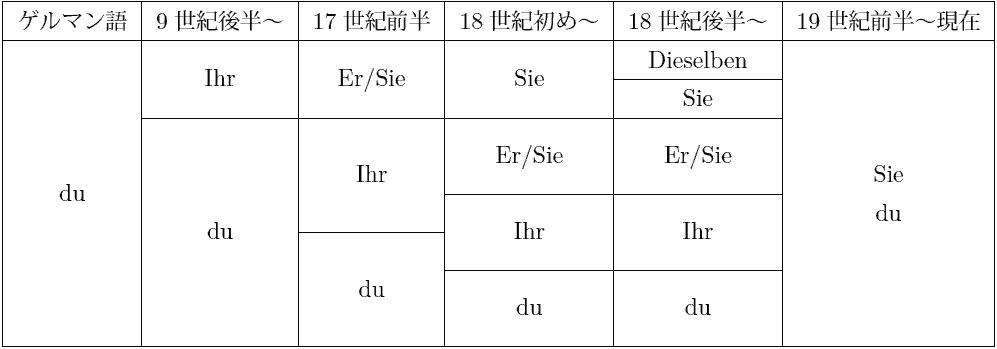

ドイツ語史は,T/V distinction について回る「敬意逓減の法則」の好例を提供してくれる.現代ドイツ語の du/Sie の2分法は,紆余曲折の歴史を経て落ち着いた結果としての2分法であり,ここに至るまでには,とりわけ近代期には複雑な段階を経験してきた.17--18世紀には,人々は相手を指すのにどの表現を使えばよいのか思い悩み,数々の2人称代名詞に「踊らされる」時代が続いていた.社会語用論的に不安定な時代と呼んでよいだろう.以下は,高田 (145) のまとめた「ひとりの相手に対するドイツ語呼称代名詞の史的発達」の表である(少々改変済み).上段にある代名詞ほど,相手の社会的身分が高い,あるいは自分と疎遠な関係にあることを示す.

この表は,ドイツ語史において2人称単数代名詞の敬称がいかに次々と生み出されてきたかを雄弁に物語っている.ゲルマン語の段階では,古英語などと同様に,2人称単数代名詞としてはT系統の形態が1つあるにすぎなかった.古英語の þū に対応する du である.この時代には王に対しても召使いに対しても対等に du のみが用いられていた.

9世紀後半になると,2人称複数代名詞であった Ihr が敬意を表す単数として用いられ始めた.これ自体は,「#1126. ヨーロッパの主要言語における T/V distinction の起源」 ([2012-05-27-1]) や「#1552. T/V distinction と face」 ([2013-07-27-1]) で触れたように,英語史やフランス語史にもみられた現象であり,しばしば権力と複数性との写像性 (iconicity) により説明される.ただし,ドイツ語史では英語史に比べてかなり早くにこの用法が現われたことは注目すべきである.こうして9世紀後半に始まった du/Ihr の2分法は,11世紀までには普及し,社会的な権力や地位,すなわち power というパラメータを軸に16世紀まで存続した.

16世紀になると長期にわたって安定していた du/Ihr の2分法が崩れ始めた.Ihr の敬意が逓減し,社会的な地位の高くない人にまで使われるようになった.その代替手段として der Herr, die Frau といった人物名称が用いられ始めたが,繰り返し使われるにつれて,これらの名詞句を受ける3人称単数代名詞 er や sie それ自体も呼称として用いられるようになった.ここに至って,新たな Er/Sie, Ihr, du の3段階システムができあがった.

18世紀に入ると,ドイツ語の呼称代名詞は「迷路」に迷い込んだ.その頃までには,高位の人に冠する称号として Eure Majestät (陛下)や Eure Ehre (閣下)や Eure Gnaden (閣下)のように,「威厳」「名誉」「恩寵」などの抽象名詞(たいてい女性名詞)を付す呼称が発達していた.これらの女性抽象名詞を前方照応する形で,3人称女性代名詞 sie が用いられていたが,これはたまたま3人称複数代名詞と同音だったために,後者にも敬称の機能が移った.ここに至って,Sie, Er/Sie, Ihr, du の4段階システムが成った.

18世紀後半には,4段階システムにおける最上位の Sie ですら敬意逓減の餌食となり,指示代名詞の複数形 Dieselben が新たな最上位の敬称として生み出され,5段階システムを形成した.ただし,Dieselben は前方の名詞と照応する形でしか用いられなかったし,書き言葉に限定されていたために,一般化することはなかった.

だが,世紀の変わり目に向けて,呼称代名詞をめぐる社会語用論の混乱は収束に向かう.最も古く,最も低位の du に「友情崇拝」 (Freundschaftskult) という社会的な価値が付され,積極的に評価されるようになってきたのだ.du に positive politeness の機能が付されるようになったといってもよいし,社会的階級あるいは power に基づく呼称体系から人間関係あるいは solidarity に基づく呼称体系へと移行したとみることもできる (cf. 「#1059. 権力重視から仲間意識重視へ推移してきた T/V distinction」 ([2012-03-21-1])).19世紀以降,du の役割の相対的な上昇と,細かな上位区分の解消により,現在あるような du/Sie の2分法へと落ち着いてゆき,ドイツ語は近代の社会語用論的な迷路から脱出することに成功した.

ドイツ語史の関連する話題としては「#185. 英語史とドイツ語史における T/V distinction」 ([2009-10-29-1]) と「#1865. 神に対して thou を用いるのはなぜか」 ([2014-06-05-1]) でも触れているので,そちらも参照されたい.

・ 高田 博行 「敬称の笛に踊らされる熊たち 18世紀のドイツ語古称代名詞」『歴史語用論入門 過去のコミュニケーションを復元する』(高田 博行・椎名 美智・小野寺 典子(編著)),大修館,2011年.143--62頁.

2015-01-16 Fri

■ #2090. 補充法だらけの人称代名詞体系 [personal_pronoun][suppletion][etymology][indo-european][paradigm]

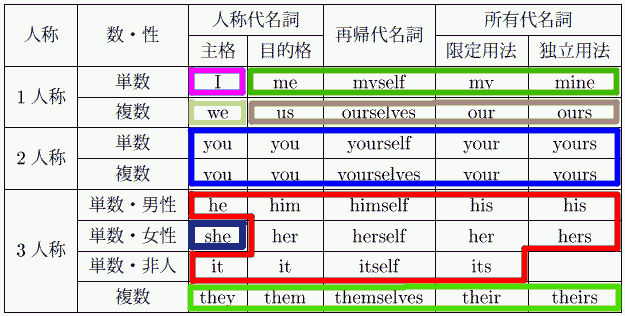

英語における人称代名詞体系の歴史は,それだけで本を書けてしまうほど話題が豊富である.今回は,(現代)英語の人称代名詞の諸形態が複数の印欧語根に遡ること,人称代名詞体系が複数語根の寄せ集め体系であることを示したい.換言すれば,人称代名詞体系が補充法の最たる例であることを指摘したい(安井・久保田, pp. 44--46).

色別にくくった表に示したとおり,8つの異なる語根が関与している.初期近代英語までは,2人称代名詞に単数系列の thou----thee--thyself--thy--thine も存在しており,印欧祖語の *tu- というまた異なる語根に遡るので,これを含めれば9つの語根からなる寄せ集めということになる.

それぞれ印欧祖語の語根を示せば,I は *eg,me 以下は *me-,we は *weis,us 以下は *n̥s に遡る (cf. 「#36. rhotacism」 ([2009-06-03-1])) .you 系列は *yu-,he 系列は *ki- に遡る.it 系列で語頭の /h/ の欠けていることについては,「#467. 人称代名詞 it の語頭に /h/ があったか否か」 ([2010-08-07-1]) を参照.they 系列は古ノルド語形の指示代名詞 þeir (究極的には印欧祖語の指示詞 *so などに遡る)に由来する.she は独立しているが,その語源説については「#827. she の語源説」 ([2011-08-02-1]) を始め she の各記事で取り上げてきたので,そちらを参照されたい.

本来,屈折とは同語根の音を少しく変異させて交替形を作る作用を指すのだから,この表を人称代名詞の「屈折」変化表と呼ぶのは,厳密には正しくない.I と my とは正確にいえば屈折の関係にはないからだ.むしろ単に人称代名詞変化表と呼んでおくほうが正確かもしれない.

パラダイムを史的に比較対照するには「#180. 古英語の人称代名詞の非対称性」 ([2009-10-24-1]),「#181. Chaucer の人称代名詞体系」 ([2009-10-25-1]),「#196. 現代英語の人称代名詞体系」 ([2009-11-09-1]) を順に参照されたい.

・ 安井 稔・久保田 正人 『知っておきたい英語の歴史』 開拓社,2014年.

2015-01-03 Sat

■ #2077. you の発音の歴史 [personal_pronoun][phonetics][diphthong][spelling]

昨日の記事「#2076. us の発音の歴史」 ([2015-01-02-1]) に引き続き,人称代名詞の発音について.2人称代名詞主格・目的格の you は,形態的には古英語の対応する対格・与格の ēow に遡る (cf. 「#180. 古英語の人称代名詞の非対称性」 ([2009-10-24-1])) .古英語の主格は ġe であり,これは ye の形態で近代英語まで主格として普通に用いられてきたが,「#800. you による ye の置換と phonaesthesia」 ([2011-07-06-1]) でみたように,you に主格の座を奪われた.以後,主格・目的格の区別なく you が標準的な形態となり,現在に至る.

しかし,少し考えただけでは古英語 ēow がどのようにして現代英語の /juː/ (強形)へ発達し得たのか判然としない.中尾 (251) により you の音韻史をひもとくと,強勢推移を含む複雑な母音の変化を遂げていることが分かった.古英語の下降2重母音的な /ˈeːou/ は強勢推移により上昇2重母音的な /eˈoːu/ の音形をもつようになり,ここから第1要素に半子音が発達し /joːu/ となった.中英語期には,この2重母音が滑化して /juː/ となった.この /juː/ は現代英語の発音と同じだが,そこに直結しているわけではなく,事情はやや複雑である./juː/ は強形としては16世紀半ばからさらなる変化を遂げて,/jəu?joː/ を発達させたが,これは17世紀には消失した.一方,/juː/ からは弱形として /jʊ, jə/ が生まれ,現在の同音の弱形に連なるが,これが再強化されて強形 /juː/ が復活したものらしい.古英語の属格 ēower も似たような複雑な経路を経て,現代英語 your (強形 /jɔː, jʊə/)を出力した.

人称代名詞の音形が弱化と強化を繰り返すというパターンは,昨日の記事 ([2015-01-02-1]) や「#1198. ic → I」 ([2012-08-07-1]) でも見られた.中尾 (316) がこの点を指摘しながら他の人称代名詞形態についても注を与えているので,引用しておこう.

ModE における文法語の強形,弱形:一般に ModE には強形,弱形が併存したが,後,前者が廃用となり,後者が再強勢を受け強形となりここからまた弱形が発達し PE に至るという経路を普通とるようである.しかし時折,弱形がそのまま強形,弱形同様に用いられることもあった.

① Prn: my [əɪ?ɪ]/me [iː, ɛː?ɪ, ɛ]//we [iː?ɪ]//thou [uː?ʊ]/thee [iː?ɪ]//ye [iː?ɪ, ɛ], 再強勢による [ɛː]/your: (i) uː > (下げ)oː, (ii) uː > (16c 半ば)[əʊ], (iii) [juː] からの弱形 [jʊ] (ここから強形 [juː])の3つが行われていた/ you: ME [juː] から (i) 強形として(16c 半ば)[jəʊ?joː] (17世紀に消失),(ii) 弱形 [jʊ] > (16c) [jə] または再強勢形 [juː] (これが PE で確立した)//he [hiː, hɛː?ɪ]//she [ʃiː?ʃɪ]//it [ɪt?t] ([t] は後消失)//they [ðəɪ?ðɪ]//their [ðɛːr?ðɛr] . . . // who [oː, uː?ɔ, ʊ]

なお,you は綴字上も実に特殊な語である.常用英単語には <u> で終わるものが原則としてないが,この you は極めて稀な例外である(大名,p. 45).

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

・ 大名 力 『英語の文字・綴り・発音のしくみ』 研究社,2014年.

2015-01-02 Fri

■ #2076. us の発音の歴史 [personal_pronoun][phonetics][centralisation][verners_law][compensatory_lengthening]

現代英語の1人称複数代名詞目的格の形態は us である.発音は,LDP によると強形が /ʌs, §ʌz/,弱形が /əs, §əz/ である(語尾子音に /z/ を示すものは "BrE non-RP").古英語では長母音をもつ ūs であり,この長母音が後に短化し,続けて中舌化 (centralisation) したものが,現代の強形であり,さらに曖昧母音化したものが現代の弱形である.と,これまでは単純に考えていた.この発展の軌跡は大筋としては間違っていないと思われるが,直線的にとらえすぎている可能性があると気づいた.

人称代名詞のような語類は,機能上,常に強い形と弱い形を持ち合わせてきた.通常の文脈では旧情報を担う語として無強勢だが,ときに単体で用いられたり対比的に使われるなど強調される機会もあるからだ.強形から新しい弱形が生まれることもあれば,弱形から新しい強形が作り出されることもあり,そのたびに若干異なる音形が誕生してきた.例えば「#1198. ic → I」 ([2012-08-07-1]) の記事でみたように,古英語の1人称単数代名詞主格形態 ic が後に I へ発展したのも,子音脱落とそれに続く代償延長 (compensatory_lengthening) の結果ではなく,機能語にしばしば見られる強形と弱形との競合を反映している可能性が高い.この仮説については,岩崎 (66) も「OE iċ は,ME になって,stress を受けない場合に /ʧ/ が脱落して /i/ となり,この弱形から強形の /íː/ が生じたと考えられる」との見解を示している.

岩崎 (67) は続けて1人称複数代名詞対格・与格形態の発音にも言い及んでいる.古英語 ūs がいかにして現代英語の us の発音へと発達したかについて,ic → I と平行的な考え方を提示している.

OE ūs は,ME になって強形 /ús/ が生じ,これが Mod E /ʌ́s/ になったものであろう.ME /uːs/ は,正常な音変化を辿れば,Great Vowel Shift によって /áus/ になはずのものである.事実,ME /üːr/ は ModE /áuə/ となっている.

まず /uːs/ から短母音化した弱形 us が生じ,そこから曖昧母音化した次なる弱形 /əs/ が生まれた.ここで短母音化した us はおそらく弱形として現われたのだから強勢をおびていないはずであり,そのままでは通常の音変化のルートに乗って /ʌs/ へ発展することはないはずである.というのは,/u/ > /ʌ/ の中舌化は強勢を有する場合にのみ生じたからである.逆にいえば,現代英語の /ʌs/ を得るためには,そのための入力として強勢をもつ /ús/ が先行していなければならない.それは,弱化しきった /əs/ 辺りの形態から改めて強化したものと考えるのが妥当だろう.

したがって,古英語 ūs から現代英語の強形 /əs/ への発展は,直線的なものではなく多少の紆余曲折を経たものと考えたい.なお,現代英語の非標準形 /ʌz, əz/ は有声子音 /z/ を示すが,この有声化も音声的な弱化の現れだろう (cf. 「#858. Verner's Law と子音の有声化」 ([2011-09-02-1])) .

OED に挙げられている us の異形態一覧を眺めれば,強形,弱形,様々な形態が英語史上に行われてきたことがよく理解できる.

留. OE-16 vs, OE- us, eME uss (Ormulum), ME oos, ME os, ME ows, ME vsse, ME vus, ME ws, ME wus, ME-15 ous, 16 vss; Eng. regional 18 as (Yorks.), 18 ehz (Yorks.), 18 ust (Norfolk), 18- az (Yorks.), 18- es (chiefly south-west.), 18- ess (Devon), 18- ez (Yorks. and south-west.), 18- uz (chiefly north. and north midl.), 19 is (north-east.), 19 ous (Yorks.); Sc. pre-17 os, pre-17 us, pre-17 uss, pre-17 usz, pre-17 vs, pre-17 ws, pre-17 wsz, pre-17 17 ous, 17 ows, 18 wes (Orkney), 18 wez (Orkney), 18 wus (Orkney), 18- 'is, 18- iz, 18- wis (Shetland), 18- wiz (Shetland), 19- is, 19- 'iz, 19- oos, 19- uz; Irish English 17 yus (north.), 18 ouse (Wexford), 18- iz (north.); N.E.D. (1926) also records a form 18 ous (regional).

硫. eME hous, ME hus, ME husse, ME hvse, ME hws, 15 huse; Eng. regional 18- hess (Devon), 18- hiz (Cumberland), 18- hus (Northumberland), 18- huz (north. and midl.); Sc. 15 18- his, 17-18 hus, 18 hooz (south.), 18 huzz, 18- hiz, 18- huss, 18- huz, 19- hes, 19- hez; Irish English (north.) 18- hiz, 19- his, 19- hus, 19- huz.

粒. Enclitic (chiefly in let's: cf. LET v.1 14a) 15- -s (now regional and nonstandard), 16- -'s, 18- -'z (chiefly Sc.), 19- -z (chiefly Sc.).

・ 岩崎 春雄 『英語史』第3版,慶應義塾大学通信教育部,2013年.

2014-11-22 Sat

■ #2035. 可算名詞は he,不可算名詞は it で受けるイングランド南西方言 [dialect][personal_pronoun][gender][countability]

Trudgill (94--95) によると,イングランド南西部の伝統方言 (Traditional Dialects),具体的には「#1029. England の現代英語方言区分 (1)」 ([2012-02-20-1]) で示した Western Southwest, Northern Southwest, Eastern Southwest では,他の変種にはみられない独特な人称代名詞の用法がある.無生物を指示するのに標準変種では人称代名詞 it を用いるが,この方言ではその無生物を表わすのが可算名詞 (countable noun) であれば he を,不可算名詞 (uncountable noun or mass noun) であれば it を用いるのが規則となっている.可算・不可算という文法カテゴリーに基づいて人称代名詞を使い分けるという点では,一種の文法性 (grammatical gender) を構成しているとも考えられるかもしれない.

例えば,この方言で "He's a good hammer." というとき,he はある男性を指すのではなく,あくまで可算名詞である無生物を指す(標準変種では it を用いるところ).また,loaf は可算名詞であるから,"Pass the loaf --- he's over there." のように he で受けられる.一方,bread は不可算名詞であるから,"I likes this bread --- it's very tasty." のように it を用いる.次の Dorset 方言詩において,he は直前の可算名詞 dress を指す (Trudgill 95 より再掲) .

Zo I 'ad me 'air done, Lor' what a game!

I thought me 'ead were on vire.

But 'twas worth it, mind, I looked quite zmart ---

I even got a glance vrom the Squire.

I got out me best dress, but he were tight,

Zo I bought meself a corset.

Lor', I never thought I'd breathe agin,

But I looked zo zlim 'twas worth it.

可算名詞と不可算名詞の区別は標準変種でも認められる文法カテゴリーだが,そこでは冠詞の選択(不定冠詞が付きうるか),形態的な制約(複数形の語尾が付きうるか),共起制限(数量の大きさを表わすのに many か much か)などにおいて具現化していた.南西部方言で特異なのは,同じ文法カテゴリーがそれに加えて人称代名詞の選択にも関与するという点においてである.この方言では,同カテゴリーの文法への埋め込みの度合いが他の変種よりもいっそう強いということになる.

・ Trudgill, Peter. The Dialects of England. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-11-11 Tue

■ #2024. 異分析による naunt と nuncle [metanalysis][article][personal_pronoun][dialect]

語境界の n が関与する異分析 metanalysis の英語史からの例を,「#4. 最近は日本でも英語風の単語や発音が普及している?」 ([2009-05-03-1]),「#27. 異分析の例を集めるにはどうすればよいか?」 ([2009-05-25-1]),「#475. That's a whole nother story.」 ([2010-08-15-1]),「#1306. for the nonce」 ([2012-11-23-1]),「#1951. 英語の愛称」 ([2014-08-30-1]) などで取り上げてきた.不定冠詞 an が関わることが多く,数の異分析 (numerical metanalysis) とも称されるが (cf. 「#344. cherry の異分析」 ([2010-04-06-1])) ,所有代名詞の mine, thine が関与する例も少なくない.

今回は,現代英語では方言などに残るにすぎない非標準的な naunt (aunt) と nuncle (uncle) にみられる異分析を取り上げる.MED aunte (n.) や OED naunt, n. によれば,この親族語の n で始まる異形は,a1400 (1325) Cursor Mundi (Vesp.) に þi naunt として初出する.ほかにも þy naunt, my nawnte など所有代名詞とともに現われる例が見られ,異分析の過程を想像することができる.naunt は後に標準語として採用されることはなかったが,Wright の English Dialect Dictionary (cf. EDD Online) によれば,少なくとも19世紀中には n.Cy., Wm., Yks., Lan., Chs., Stf., Der., Wor., Shr., Glo., Oxf., Som. など主としてイングランド西部で行われていた.

同じように nuncle について調べてみると,MED uncle (n.) や OED nuncle, n. に,異分析による n を示す þi nunkle のような例が15世紀に現われる.なお,人名としての Nuncle は1314年に初出するので,異分析の過程そのものは早く生じていたようだ.後期近代英語には,これから分化したと思われる nunky, nunks などの語形も OED に記録されている.EDD によれば,naunt と同じく n.Cy., Yks., Lan., Chs., Der., Lei., Wor., Shr., Glo., Hmp., Wil., Dor., Som., Dev. などの諸方言で広く観察される.

所有代名詞の mine や thine に先行される異分析の例は,OED N, n. に詳述されているが,多くは14--16世紀に生じている.後の標準語として定着しなかったものも多いことと合わせて,これらの異分析形が後期中英語期にいかに受容されていたか,そして当時およびその後の方言分布はどのようなものだったかを明らかにする必要があるだろう.現代標準語に残っている異分析の例に加えて,必ずしも分布を広げなかったこのような「周辺的な」異分析の例を合わせて考慮することで,興味深い記述が可能となるかもしれない.

なお,英語 aunt は,ラテン語 amita から古フランス語 aunte を経由して1300年頃に英語に入ってきたものだが,フランス語ではその後語頭に t を付加した tante が標準化した.『英語語源辞典』はこの t の挿入について,「幼児の使う papa 式の加重形 antante あるいは t'ante thy aunt に由来するなど諸説がある」としている.もし t'ante 説を取るのであれば,フランス語 tante と英語 naunt は音こそ異なれ,同様に異分析の例ということになる.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow