2021-07-21 Wed

■ #4468. 現代英語で主語が省略されるケース [syntax][personal_pronoun]

昨日の「英語の語源が身につくラジオ」にて,「昔の英語では主語が必須じゃなかった!」を放送しました.古英語や中英語では主語が現われない文があり得たという衝撃の話題を取り上げましたが,実は現代英語でも口語や定型文句においては,文法や文脈から補うことのできる自明な主語が省略されることは,少なくありません.Quirk (§12.47)より,人称別に主語が省略されるパターンを示しておきます.

[1人称主語の省略]

・ (I) Beg your pardon.

・ (I) Told you so.

・ (I) Wonder what they're doing.

・ (I) Hope he's there.

・ (I) Don't know what to say.

・ (I) Think I'll go now.

[2人称主語の省略]

・ (You) Got back all right?

・ (You) Had a good time, did you?

・ (You) Want a drink?

・ (You) Want a drink, do you?

[3人称主語の省略]

・ (He/She) Doesn't look too well.

・ (He/She/They) Can't play at all.

・ (It) Serves you right.

・ (It) Looks like rain.

・ (It) Doesn't matter.

・ (It) Must be hot in Panama.

・ (It) Seems full.

・ (It) Makes too much noise.

・ (It) Sounds fine to me.

・ (It) Won't be any use.

・ (There) Ought to be some coffee in the pot.

・ (There) Must be somebody waiting for you.

・ (There) May be some children outside.

・ (There) Appears to be a big crowd in the hall.

・ (There) Won't be anything left for supper.

思ったより多種多様な主語省略があるなあ,という印象ではないでしょうか.2人称では疑問文が基本であり,3人称では it や there の例が多いなど,一定の傾向も確認されます.

現代英語では原則として主語が必須である,ということは英語学習・教育でも金科玉条とされています.それでも,このように主語省略の事例は確かにありますし,英語史的にも主語省略は決して稀ではなかったということは,改めてここで述べておきたいと思います.

2021-07-01 Thu

■ #4448. 中英語のイングランド海岸諸方言の人称代名詞 es はオランダ語からの借用か? [personal_pronoun][me_dialect][dutch][borrowing][clitic]

標題は,「#3701. 中英語の3人称複数対格代名詞 es はオランダ語からの借用か? (1)」 ([2019-06-15-1]) および「#3702. 中英語の3人称複数対格代名詞 es はオランダ語からの借用か? (2)」 ([2019-06-16-1]) で取り上げてきた話題である.

一般にオランダ語が英語に及ぼした文法的影響はほとんどないとされるが,その可能性が疑われる稀な言語項目として,中英語のイングランド海岸諸方言で行なわれていた人称代名詞の es が指摘されている(ほかに「#140. オランダ・フラマン語から借用した指小辞 -kin」 ([2009-09-14-1])も参照).

このオランダ語影響説について,Thomason and Kaufman (323) が興奮気味の口調で紹介し解説しているので,引用しよう.

[T]here was a striking grammatical influence of Low Dutch on ME that is little known, because though introduced sometime before 1150, it is found in certain dialects only and disappeared by the end of the fourteenth century . . . .

In the Lindsey (Grimsby?), Norfolk, Essex, Kent (Canterbury and Shoreham), East Wessex (Southampton?), and West Wessex (Bristol?) dialects of ME, attested from just before 1200 down to at least 1375, there occurs a pronoun form that serves as the enclitic/unstressed object form of SHE and THEY. Its normal written shape is <(h)is> or <(h)es>, presumably /əs/; one text occasionally spells <hise>. This pronoun has no origin in OE. It does have one in Low Dutch, where the unstressed object form for SHE and THEY is /sə/, spelled <se> (this is cognate with High German sie). If the ME <h> was ever pronounced it was no doubt on the analogy of all the other third person pronoun forms of English. We do not know whether Low Dutch speakers settled in sizable numbers in all of the dialect areas where this pronoun occurs, but there is one striking correlation: all these dialect areas abut on the sea . . ., and after 1070 the seas near Britain, along with their ports, were the stomping grounds of the Flemings, Hollanders, and Low German traders. These facts should remove all doubt as to whether this pronoun is foreign or indigenous (and just happened not to show up in any OE texts!).

引用の最後で述べられている通り,「疑いがない」というかなり強い立場が表明されている.p. 325 では "this clear instance of structural borrowing from Low Dutch into Middle English" とも述べられている.仮説としてはとてもおもしろいが,先の私の記事でも触れたように,もう少し慎重に論じる必要があると思われる.West Midland の内陸部でも事例が見つかっており,同説を簡単に支持することはできないからだ.連日引用してきた Hendriks (1668) も,Thomason and Kaufman のこの説には懐疑的な立場を取っており,論題として取り上げていないことを付言しておきたい.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey and Terrence Kaufman. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: U of California P, 1988.

・ Hendriks, Jennifer. "English in Contact: German and Dutch." Chapter 105 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1659--70.

2021-05-27 Thu

■ #4413. 動詞の目的語としての無意味な it [personal_pronoun][verb][phrase][conversion][idiom]

「英語史導入企画2021」より本日紹介するコンテンツは,院生による「映画『マトリックス』が英語にのこしたもの」.これだけでは何のことか分からないと思いますが,同映画から生まれた the red pill,the blue pill という口語表現に焦点を当てたコンテンツです.同コンテンツによれば「blue pill とは,世界の真実を知ることなく,自分が信じたいことだけを信じることができることを象徴し,一方,red pill は多少痛みを伴うような,厳しくつらい世の中の真実を知ることの象徴」とのこと.手近の辞書には未掲載でしたので,確かに新語(義)のようです.

さらにこの名詞句が品詞転換により動詞化し,We need to red pill it Canadians. (つらい現実に目を向ける必要があるのだ,カナダ人たちよ.)のように使われるというので,驚きました.to blue pill it もあるようです.つい先日「#4405. ポップな話題としての「句動詞の品詞転換」」 ([2021-05-19-1]) と題する記事にて「句動詞の名詞・形容詞への品詞転換」の事例を取り上げたばかりですが,今回は「名詞句の動詞への品詞転換」という逆の事例ということになります.今回のコンテンツも知らないことばかりで勉強になりました.

to red/blue pill it という新表現を見てふと思ったのですが,口語的な慣用句 (idiom) にしばしば現われる,動詞の目的語としての無意味な it というのは何なのでしょうかね.I made it. とか Take it easy. とか Damn it. とか.今回のケースのように口語的な文脈で新しく動詞化した語の場合には,そのまま裸で使うと落ち着きが悪いので,何となく it を添えて(他)動詞っぽさを出してみた,というような感じでしょうか.

もちろん英語に実質的な意味をもたない it の用法があることはよく知られています.prop/dummy/empty/expletive/introductory/ambient it などと様々に称されていますが,要するに何らかの文法的な機能は果たしているけれども,実質的な指示対象をもたず意味が空っぽ(に近い)というべき it の用法のことです.ただし,そのなかでも to red/blue pill it のような動詞の目的語となる it の無意味さは著しいように思われます.実際,Quirk et al. (§6.17n) ではこの種の it に触れ,「完璧に空っぽ」と表現しています.

Perhaps the best case for a completely empty or 'nonreferring' it can be made with idioms in which it follows a verb and has vague implications of 'life' in general, etc:

At last we've made it. ['achieved success']

have a hard time of it ['to find life difficult']

make a go of it ['to make a success of something']

stick it out ['to hold out, to preserve']

How's it going?

Go it alone.

You're in for it. ['You're going to be in trouble.']

OED の it, pron., adj., and n.1 によると,語義8aのもとで問題の用法が取り上げられています.初出は以下の通り16世紀前半のようです.

8.

a. As a vague or indefinite object of a transitive verb, after a preposition, etc. Also as object of a verb which is predominantly intransitive, giving the same meaning as the intransitive use, and as object of many verbs formed (frequently in an ad hoc way) from nouns meaning 'act the character, use the thing, indicated'.

Through verbs having corresponding nouns of the same form, as to lord, the construction seems to have been extended to other nouns as king, queen, etc. There may have been some influence from do it as a substitute, not only for any transitive verb and its object, but for an intransitive verb of action, as in 'he tried to swim, but could not do it', where it is the action in question.

?1520 J. Rastell Nature .iiii. Element sig. Eviv And I can daunce it gyngerly..And I can kroke it curtesly And I can lepe it lustly And I can torn it trymly And I can fryske it freshly And I can loke it lordly.

. . . .

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2021-04-28 Wed

■ #4384. goodbye と「さようなら」 [interjection][euphemism][subjunctive][optative][etymology][personal_pronoun][abbreviation][khelf_hel_intro_2021]

昨日,学部生よりアップされた「英語史導入企画2021」の20番目のコンテンツは,goodbye の語源を扱った「goodbye の本当の意味」です.

God be with ye (神があなたとともにありますように)という接続法 (subjunctive) を用いた祈願 (optative) の表現に由来するとされます.別れ際によく用いられる挨拶となり,著しく短くなって goodbye となったという次第です.ある意味では「こんにちはです」が「ちーす」になるようなものです.

しかし,ここまでのところだけでも,いろいろと疑問が湧いてきますね.例えば,

・ なぜ God が good になってしまったのか?

・ なぜ be が bye になってしまったのか?

・ なぜ with ye の部分が脱落してしまったのか?

・ そもそも you ではなく ye というのは何なのか?

・ なぜ祝福をもって「さようなら」に相当する別れの挨拶になるのか?

いずれも英語史的にはおもしろいテーマとなり得ます.上記コンテンツでは,このような疑問のすべてが扱われているわけではありませんが,God be with ye から goodbye への変化の道筋について興味をそそる解説が施されていますので,ご一読ください.

とりわけおもしろいのは,別れの挨拶として日本語「さようなら(ば,これにて失礼)」に感じられる「みなまで言うな」文化と,英語 goodbye (< God be with ye) にみられる「祝福」文化の差異を指摘しているところです.

確かに英語では (I wish you) good morning/afternoon/evening/night から bless you まで,祝福の表現が挨拶その他の口上となっている例が多いように思います.高頻度の表現として形態上の縮約を受けやすいという共通点はあるものの,背後にある「発想」は両言語間で異なっていそうです.

2021-03-23 Tue

■ #4348. 人を呼ぶということ [address_term][politeness][pragmatics][historical_pragmatics][anthropology][personal_pronoun][personal_name][onomastics][t/v_distinction][taboo][title][honorific][face]

言語学では「人を呼ぶ」という言語行為は,人類言語学,社会言語学,語用論,人名学など様々な観点から注目されてきた.本ブログの関心領域である英語史の分野でも,人名 (anthroponym),呼称 (address_term),2人称代名詞の t/v_distinction の話題など,「人を呼ぶ」ことに関する考察は多くなされてきた.身近で日常的な行為であるから,誰もが興味を抱くタイプの話題といってよい.

しかし,そもそも「人を呼ぶ」とはどういうことなのか.滝浦 (78--79) より,示唆に富む解説を引用する.

すこし回り道になるが,“人を呼ぶ”ことの根本的な意味を確認しておきたい.文化人類学的に見れば,人を呼ぶことは声で相手に“触れる”ことであり,基本的なタブーに抵触する側面を持つ.そのため,多くの言語文化において,呼ぶことの禁止,あるいはそれに起因する敬避的呼称が発達した.日本語もこのタブーの影響が強く,敬避的呼称の例は,たとえば「僕(=しもべ)」「あなた(=彼方)」「御前(=人物の“前”の場所)」「○○殿(=建物名)」「陛下(=階段の下)」等々,いくらでも挙げることができる.相手を上げ自分を下げ,また,相手の“人”を呼ぶ代わりに方向や場所を呼ぶこうした方式は,呼ぶことで自分と相手が触れてしまうのを避けるために,“なるべく呼ばないようにして呼ぶ”ことが動機づけになっている遠隔化的呼称である.

一方,相手ととくに親しい関係にある場合には,こうしたタブー的な動機づけは反転し,むしろ相手の“人”をじかに呼び,相手の内面に踏み込んでゆくような呼称となる.これは,相手の領域に踏み込んでも人間関係は損なわれない――そのくらい2人の間には隔てがない――という含みの,共感的呼称である.固有名(とくに姓の呼び捨てや下の名で呼ぶこと)による呼称,限られた人しか知らない愛称による呼称が典型だが,代名詞による呼称もその傾きを持つ.

人を呼ぶのは一種のタブー (taboo) であるということ,しかしそれはしばしば破られるべきタブーであり,そのための呼称が多かれ少なかれオープンにされているということが重要である.人を呼んではいけない,しかし呼ばざるをえない,という矛盾のなかで,私たちはその矛盾による問題を最小限に抑えようとしながら,日々言語行為を行なっているのである.

・ 滝浦 真人 『ポライトネス入門』 研究社,2008年.

2021-02-13 Sat

■ #4310. shall's (= shall us = shall we) は初期近代英語期でそこそこ使われていた [eebo][personal_pronoun][speech_act][analogy]

昨日の記事「#4309. shall we の代わりとしての shall's (= shall us)」 ([2021-02-12-1]) で取り上げたように,shall we の代用としての shall's は Shakespeare などにもみられる.関心をもって,初期近代英語の巨大コーパス EEBO corpus により "shall 's" と "shal 's" で検索してみると,135例もヒットした.すべてのコンコーダンスラインを精査したわけではないが,多少のゴミは混じっているものの,大部分は目下問題にしている shall we の代用としての用例とみてよさそうだ.いくつか例を挙げよう(最初の4例は Shakespeare より).

・ if he couetously reserue it, how shall 's get it?

・ where shall 's lay him?

・ shall 's haue a play of this?

・ shal 's to the Capitoll?

・ shall 's daunce?

・ shall 's to th' Taverne?

・ come, shal 's shake hands, sirs?

・ what shall 's do this evening?

・ shall 's to dinner now?

・ come, come, shall 's go drink?

そもそもこの表現は統語的には疑問文であり,発話行為としては勧誘であり,口語的な色彩も強い.おそらく,当時,そのような響きをもったフレーズとして固定化していたものと思われる.機能的にいえば let's に近いと言えるが,この let's 自身も let us をつづめたものである.後者では us が正規の目的格形として用いられており,shall us の破格的な目的格形 us の使用とは一線を画していることは疑いようもないが,もしかすると両者の間に機能的類似に基づく類推 (analogy) が作用していたのかもしれない (cf. 「#1981. 間主観化」 ([2014-09-29-1])) .

なお,省略されていない "shall us" でも検索してみた.こちらでは88例がヒットしたが,us が正規の目的格として用いられている例も多く混じっており,省略版 shall's と比べれば shall we の代用表現としての用例は稀のようだ.

2021-02-12 Fri

■ #4309. shall we の代わりとしての shall's (= shall us) [shakespeare][personal_pronoun]

Shakespeare, Winter's Tale, Act I, Scene 2 にて,Hermione が Leontes に次のように語りかける箇所がある."If you would seek us, We are yours i' the garden: shall's attend you there?" ここでは,shall's (= shall us) が shall we の代わりとして用いられている.主格の us の事例だ.

主格形が用いられるべきところで目的格形が現われるというのは,we/us に限らず人称代名詞全般によくみられる現象である.It's me., He is older than her., what did 'em call it?, Us Scots keep fighting back. のような例が挙げられるし,you に至っては,歴史的に区別されていた主格形と目的格形が後者に集約されてしまったものが標準形となっているほどだ.

「#3502. pronoun exchange」 ([2018-11-28-1]) でみたように,この種の人称代名詞の「格違い」は,現代の諸方言において広く観察される (cf. 「#793. she --- 現代イングランド方言における異形の分布」 ([2011-06-29-1])).歴史的にも,おそらく pronoun exchange は日常茶飯だったろう.

ただし,OED によると,we/us の pronoun exchange に関していえば,あくまで近代以降の現象のようだ.us, pron., n., and adj. の 9b に,問題の用法が挙げられている.以下に,いくつか例を出そう.2つ目がまさに shall us の事例である.

・ 1562 N. Winȝet Certain Tractates (1888) I. 12 And vtheris for not saying this ane word---'My maisteris, vs lufe ȝou and ȝour doctryne' are deposit of thair offices.

・ 1607 T. Dekker & J. Webster Famous Hist. Thomas Wyat sig. Bv Come my Lords, shall vs march.

・ c1860 J. T. Staton Bobby Shuttle iii. 41 Should us tell o'th yung shantledurt?

・ 1880 L. Parr Adam & Eve II. 25 Us'll have down the big Bible and read chapters verse by verse.

以上,慶應義塾大学文学部英米文学専攻の同僚で,Shakespearian の井出新教授よりお尋ねを受けて調べた次第です.(井出先生,英語史的にもおもしろい問いをありがとうございます!)

2020-10-21 Wed

■ #4195. なぜ船や国名は女性代名詞 she で受けられることがあるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版 [hellog-radio][sobokunagimon][hel_education][gender][personal_pronoun][personification][pc]

今でも英文法書などで触れられる機会があるからでしょうか,標題の質問はよく問われます.船や国名は無生物ですから,人称代名詞としては中性の人称代名詞 it で受けるのが適切のように思われますが,ときに女性の人称代名詞 she で受けられます.

・ There were over two thousand people aboard the Titanic when she left England.

・ Look at my sports car. Isn't she a beauty?

・ France increased her exports by 10 per cent.

・ After India became independent, she chose to be a member of the Commonwealth.

英語の歴史を少しかじっている方は,古英語には,フランス語やドイツ語などに現在も存在している文法性 (grammatical gender) があったということを知っているかと思います.古英語ではすべての名詞が男性,女性,中性のいずれかに振り分けられており,しかもその名詞の指示対象の生物学的な性とは必ずしも一致していなかったという,厄介な名詞分類があったのです.すると,船や国家を受ける she も古英語時代の文法性の名残ではないかと疑われるかもしれません.

しかし,そうではありません.「船」についていえば古英語の sċip (ship) は中性名詞でしたし,bāt (boat) も男性名詞でした.つまり,古英語の文法性は無関係です.では,なぜ現代英語では she が用いられることがあるのでしょうか.解説をどうぞ.

古英語で機能していた文法性は,中英語期にかけて崩壊していきます.この中英語期に,大陸の文学・文化の影響を受けて,前時代の文法性とは独立した「擬人性」という別種のジェンダーが発達することになったのです.船を始めとする乗り物や道具,そして国家などは,その舵取り役は歴史を通じて主に男性が担ってきました.船首や為政者である男性は,船や国家を「連れ合い」「愛人」「支配・制御すべきもの」として女性に見立てたということかもしれません.

ただし,近年の英語ではこの慣習は失われてきており,とりわけ公的な言葉使いとしては避けられるようになってきていることは付け加えておきましょう.

ということで,標題の素朴な疑問に対しては,中英語期以降に発達した「擬人性」の伝統を受け継いできたから,と答えておきます.この話題について深く知りたい方は,ぜひ ##3647,852,853,854,1912,1028,1517の記事セット をどうぞ.

2020-10-08 Thu

■ #4182. 「言語と性」のテーマの広さ [sociolinguistics][hellog_entry_set][political_correctness][personal_pronoun][gender][gender_difference][taboo][slang][personification]

いよいよ始まった今学期の社会言語学の授業では「言語と性」という抜き差しならぬテーマを扱う.このテーマから連想される話題は多岐にわたる.あまりに広い範囲を覆っているために,一望するのが困難なほどである.実際に,授業の履修生に連想される話題を箇条書きで挙げてもらったところ,のべ1,000件を優に超える話題が集まった.重複するものも多く,整理すればぐんと減るとは思われるが,それにしても凄い数だ(←皆さん,協力ありがとう).その一部を覗いてみよう.

・ (英語を除く)主要な印欧諸語にみられる文法性 (grammatical gender)

・ 代名詞にみられる性差

・ 職業名や称号を巡るポリティカル・コレクトネス (political_correctness)

・ LGBTQ と言語

・ 擬人化された名詞の性

・ 人名における性

・ 「男言葉」と「女言葉」

・ 性に関するスラングやタブー語

・ 性別によるコミュニケーションの取り方の違い

・ イントネーションの性差

そもそも,古今東西すべての言語で,「男」 (man) と「女」 (woman) という2つの単語が区別されて用いられている点からして,もう言語における性の話しは始まっているのである.最先端の関心事である LGBTQ やポリティカル・コレクトネスの問題に迫る以前に,すでに性は言語に深く刻まれている.

最先端の話題ということでいえば,10月2日の読売新聞朝刊で,JAL が乗客に対する「レディース・アンド・ジェントルメン」の呼びかけをやめ「オール・パッセンジャーズ」へ切り替える決定をしたとの記事を読んだ.人間の関心事としては最重要なものの1つとして認識される性,それが人間に特有の言語という体系に埋め込まれていないわけがないのである.

「言語と性」のテーマの広さを味わうところから議論を始めたいと思っている.こちらの hellog 記事セットをどうぞ.

2020-09-30 Wed

■ #4174. なぜ you は「あなた」でもあり「あなたがた」でもあるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版 [hellog-radio][sobokunagimon][hel_education][personal_pronoun][number][t/v_distinction]

英語という言語は,名詞においてきっちり単数と複数を区別しなければ気の済まない言語なわけですが,その割には重要語である you には単数(あなた)と複数(あなた方)の区別がありません.これは実に奇妙なことに思われます.むしろ,このような重要語でこそ単複の区別があってしかるべきではないかと突っ込まざるを得ません.なぜ2人称代名詞において単複を区別しないのか.この謎は,英語史をひもとくことにより解決できます.以下の解説をお聴きください.

英語でも古くは2人称代名詞にも単複の区別がありました.単数の「あなた」に thou (古英語では þū)という形を用い,複数の「あなた方」に you (古英語では ġē)という異なる系列の語が用いられていました.しかし,中英語期にラテン語やフランス語の特殊な慣用の影響を受け,本来複数形だった you 系列が「あなた様」という丁寧な単数(いわゆる「敬称」)にも用いられるようになったのです.一方,thou は,親しみ,あるいは蔑みをもって単数の相手を指す低位の代名詞(いわゆる「親称」)に成りさがりました.語用論的にはちょっと厄介な状況です.

このちょっと厄介な慣用は現在のヨーロッパの諸言語にそのまま残っているのですが,英語では続く近代英語期に解消されることになりました.その理由については諸説ありますが,結果として英語では敬称 you が親称 thou を呑み込むようにして一般化したのです.結果として,you は古英語以来の複数の「あなた方」の語義は保持しつつ,一方で敬称・親称の区別のない汎用の単数の「あなた」の語義をも獲得したことになります.これが,現在の状況です.

上記の英語史上の経緯と,その現代へのインパクトを語り出せば,10分の解説どころか90分の講義でも足りません.英語史上,きわめて重要かつ魅力的なこの話題については,ぜひ##3099,1126,1127,440,529の記事セットをじっくりご覧ください.とりわけ,英語史連載企画「現代英語を英語史の視点から考える」の第10回の記事「なぜ you は「あなた」でもあり「あなたがた」でもあるのか?」で,この話題について丁寧に記述していますので,そちらをどうぞ.

2020-08-08 Sat

■ #4121. なぜ she の所有格と目的格は her で同じ形になるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版 [hellog-radio][sobokunagimon][hel_education][personal_pronoun][case][germanic]

hellog ラジオ版の第14回は,英語初学者から寄せられた素朴な疑問です.人称代名詞において所有格と目的格はおよそ異なる形態をとりますが,女性単数の she に関してのみ her という同一形態が用いられます.これでは学ぶのに混乱するのではないか,という疑問かと思います.

同一形態でありながら2つ異なる機能を担うというのは,一見すると確かに混乱しそうですが,実際上,それで問題となることはほとんどありません.主格と目的格の形態で考えてみれば,you と it は同一形態をとっていますが,それで混乱したということは聞きません.

しかも,英語の歴史を振り返ってみれば,異なる機能にもかかわらず同一形態をとるようになったという変化は日常茶飯でした.例えば現代の人称代名詞の「目的格」は,もともとは対格と与格という別々の形態・機能を示していたものが,歴史の過程で同一形態に収斂してしまった結果の姿です.また,古い英語では2人称代名詞は単数と複数とで形態が区別されていましたが,近代英語以降に you に合一してしまったという経緯があります(cf. 「#3099. 連載第10回「なぜ you は「あなた」でもあり「あなたがた」でもあるのか?」」 ([2017-10-21-1])).もしこのような変化が本当に深刻な問題だったならば,現代英語は問題だらけの言語ということになってしまいますが,現代英語は目下世界中でまともに運用されているようです.

さらに標準英語から離れて英語の方言に目を移せば,主格 she の代わりに所有格・目的格の形態に対応する er を使用する方言も確認されます(cf. 「#793. she --- 現代イングランド方言における異形の分布」 ([2011-06-29-1]),「#3502. pronoun exchange」 ([2018-11-28-1])).日々そのような方言を用いて何ら問題なく生活している話者が当たり前のようにいるわけです.

物事を構造的にとらえる習慣のついている現代人にとって,言語も体系である以上,機能が異なれば形態も異なるはずだし,形態が異なれば機能も異なるはずだと考えるのは自然です.しかし,言語も歴史のなかで複雑な変化に揉まれつつ現在の姿になっているわけですので,必ずしも表面的にきれいな構造を示していないことも多いのです.

今回の疑問は,実に素朴でありながらも,実は2000年という長い時間軸を念頭にアプローチすべき問題であることを教えてくれる貴重な問いだと思います.

この問題とその周辺については,##4080,3099,793,3502の記事セットをご覧ください.

2020-06-28 Sun

■ #4080. なぜ she の所有格と目的格は her で同じ形になるのですか? [sobokunagimon][personal_pronoun][case][germanic]

英語教育現場より寄せてもらった素朴な疑問です.確かに他の人称代名詞を考えると,すべて所有格と目的格の形態が異なっています.my/me, your/you, his/him, its/it, our/us, their/them のとおりです.名詞についても所有格と目的格(=通格)は boy's/boy, Mary's/Mary のように原則として異なります.つまり,3人称女性単数代名詞 she は,所有格と目的格の形態が同形となる点で,名詞類という広いくくりのなかでみてもユニークな存在なのです.標題の素朴な疑問は,きわめて自然な問いということになります.

この問いに一言で答えるならば,もともとは異なった形態をとっていたものが,後の音変化の結果,たまたま同形に合一してしまった,ということになります.古い時代の音変化のなせるわざということです.

千年以上前に話されていた古英語にさかのぼってみましょう.her は,すでに当時より,所有格(当時の「属格」)と目的格(当時の「与格」)は hi(e)re という同じ形態を示していました.ということは,この素朴な疑問は英語史の枠内にとどまっていては解決できないことになります.

そこで,古英語よりも古い段階の言語の状態を反映しているとされる英語の仲間言語,すなわちゲルマン語派の諸言語の様子を覗いてみましょう.古サクソン語や古高地ドイツ語では,3人称女性単数代名詞の属格は ira,与格は iru であり,微妙ながらも形態が区別されていました.古ノルド語でも属格は hennar, 与格は henne と異なっていましたし,ゴート語でも同様で属格は izōs, 与格は izai でした.

つまり,古英語よりも古い段階では,3人称女性単数代名詞の属格と与格は,他の代名詞の場合と同様に,区別された形態をとっていたと考えられます.しかし,区別されていたとはいえ語尾の僅かな違いによって区別されていたにすぎず,その部分が弱く発音されてしまえば,区別がすぐにでも失われてしまう可能性をはらんでいました.そして,実際にそれが古英語までに起こってしまっていたのです.

このようにみてくると,現代英語の my/me や your/you 辺りも互いに似通っているので,危ういといえば危ういのかもしれません.実際,速い発音では合一していることも多いでしょう.her に関しては,その危険の可能性が他よりも早い段階で現実化してしまったにすぎません.名詞類全体のなかでも特異な,仲間はずれ的な存在となってしまいましたが,歴史の偶然のたまものですから,彼女のことを優しく見守ってあげましょう.

2020-04-26 Sun

■ #4017. なぜ前置詞の後では人称代名詞は目的格を取るのですか? [sobokunagimon][preposition][case][dative][syncretism][inflection][personal_pronoun]

標題は,先日,慶應義塾大学通信教育学部のメディア授業「英語史」の電子掲示板でいただいた素朴な疑問です.

with me, for her, against him, between us, among them など前置詞の後に人称代名詞が来るときには目的格に活用した形が用いられます.なぜ主格(見出し語の形)を用いて各々 *with I, *for she, *against he, *between we, *among they とならないのか,という質問です(星印はその表現が文法上容認されないことを示す記号です).

最も簡単な回答は「前置詞の目的語となるから」です.動詞の目的語が人称代名詞の場合に目的格の形を要求するように,前置詞の目的語も人称代名詞の目的格を必要とするということです.動詞(正確には他動詞)にしても前置詞にしても,それが表わす動作や関係の「対象」となるものが必ず直後に来ます.この「対象」を表わす語句が「目的語」であり,これが主体(主語)と区別される独特な形を取っていれば,文法上の機能が見た目にも区別しやすくなり便利です.

しかし,文中で他動詞や前置詞が特定できれば,その後ろに来るものは必然的に目的語ということになり,独特な形を取る必要はないのではないかという疑問が生じます.実際,文法上はダメだしされる上記の *with I, *for she, *against he, *between we, *among they でも意味はよく理解できます.他動詞の後でも *Do you love I/he/she/we/they? は文法的にダメと言われても,実は意味は通じてしまうわけです.

では,この疑問について英語史の視点から迫ってみましょう.千年ほど前の古英語の時代には,代名詞に限らずすべての名詞が,前置詞の後では典型的に「与格」と呼ばれる形を取ることが求められていました.前置詞の種類によっては「与格」ではなく「対格」や「属格」の形が求められる場合もありましたが,いずれにせよ予め決められた(主格以外の)格の形が要求されていたのです(cf. 「#30. 古英語の前置詞と格」 ([2009-05-28-1])).(ちなみに,現代英語の「目的格」は古英語の「与格」や「対格」を継承したものです.)

名詞に関しては,たいてい主格に -e 語尾を付けたものが与格となっていました.例えば「神は」は God ですが,「神のために」は for Gode といった具合です.しかし,続く中英語の時代にかけて,この与格語尾の -e が弱まって消えていったために,形の上で主格と区別できなくなり for God となりました.したがって,現代英語の for God の God は,解釈の仕方によっては,-e 語尾が隠れているだけで,実は与格なのだと言えないこともないのです.

一方,人称代名詞に関しては,主格と区別された与格の形がよく残りました.古英語で「神」を人称代名詞で受ける場合,「神は」は He で「神のために」は for Him となりましたが,この状況は現代でもまったく変わっていません.人称代名詞は名詞と異なり使用頻度が著しく高く,それゆえに与格を作るのに -e などの語尾をつけるという単純なやり方を採用しなかったため,主格との区別が後々まで保持されやすかったのです.ただし,you と it に関しては,歴史の過程で様々な事情を経て,結局目的格が主格と合一してしまいました.

現代英語では,動詞の目的語にせよ前置詞の目的語にせよ,名詞ならば主格と同じ形を取って済ませるようになっており,それで特に問題はないわけですから,人称代名詞にしても,主格と同じ形を取ったところで問題は起こらなさそうです.しかし,人称代名詞については過去の慣用の惰性により,いまだに with me, for her, against him, between us, among them などと目的格(かつての与格)を用いているのです.要するに,人称代名詞は,名詞が経験してきた「与格の主格との合一」という言語変化のスピードに着いてこられずにいるだけです.しかし,それも時間の問題かもしれません.いつの日か,人称代名詞の与格もついに主格と合一する日がやってくるのではないでしょうか.その時には,星印の取れた with I, for she, against he, between we, among they が聞こえてくるはずです.

2020-04-13 Mon

■ #4004. 古英語の3人称代名詞の語頭の h [h][oe][personal_pronoun][indo-european][germanic][etymology][paradigm][number][gender]

古英語の3人称代名詞の屈折表について「#155. 古英語の人称代名詞の屈折」 ([2009-09-29-1]) でみたとおりだが,単数でも複数でも,そして男性・女性・中性をも問わず,いずれの形態も h- で始まる.共時的にみれば,古英語の h- は3人称代名詞マーカーの機能を果たしていたといってよいだろう.ちょうど現代英語で th- が定的・指示的な語類のマーカーであり,wh- が疑問を表わす語類のマーカーであるのと同じような役割だ.

非常に分かりやすい特徴ではあるが,皮肉なことに,この特徴こそが中英語にかけて3人称代名詞の屈折体系の崩壊と再編成をもたらした元凶なのである.古英語では,h- に続く部分の母音等の違いにより性・数・格をある程度区別していたが,やがて屈折語尾の水平化が生じると,性・数・格の区別が薄れてしまった.たとえば古英語の hē (he), hēo (she), hīe (they) が,中英語では(方言にもよるが)いずれも hi などの形態に収斂してしまった.h- そのものは変化しなかったために,かえって混乱を来たすことになったわけだ.かつては「非常に分かりやすい特徴」だった h- が,むしろ逆効果となってしまったことになる.

そこで,この問題を解決すべく再編成のメカニズムが始動した.h- ではない別の子音を語頭にもつ she が女性単数主格に,やはり異なる子音を語頭にもつ they が複数主格に進出し,後期中英語までに古形を置き換えたのである(これらに関する個別の問題については「#713. "though" と "they" の同音異義衝突」 ([2011-04-10-1]),「#827. she の語源説」 ([2011-08-02-1]),「#974. 3人称代名詞の主格形に作用した異化」 ([2011-12-27-1]),「#975. 3人称代名詞の斜格形ではあまり作用しなかった異化」 ([2011-12-28-1]),「#1843. conservative radicalism」 ([2014-05-14-1]),「#2331. 後期中英語における3人称複数代名詞の段階的な th- 化」 ([2015-09-14-1]) を参照).

さて,古英語における h- は共時的には3人称代名詞マーカーだったと述べたが,通時的にみると,どうやら単数系列の h- と複数系列の h- は起源が異なるようだ.つまり,h- は古英語期までに結果的に「非常に分かりやすい特徴」となったにすぎず,それ以前には両系列は縁がなかったのだという.Lass (141) を参照した Marsh (15) は,単数系列の h- は印欧祖語の直示詞 *k- にさかのぼり,複数系列の h- は印欧祖語の指示代名詞 *ei- ? -i- にさかのぼるという.後者は前者に基づく類推 (analogy) により,後から h- を付け足したということらしい.長期的にみれば,この類推作用は古英語にかけてこそ有用なマーカーとして恩恵をもたらしたが,中英語にかけてはむしろ迷惑な副作用を生じさせた,と解釈できるかもしれない.

なお,上で述べてきたことと矛盾するが「#467. 人称代名詞 it の語頭に /h/ があったか否か」 ([2010-08-07-1]) という議論もあるのでそちらも参照.

・ Marsh, Jeannette K. "Periods: Pre-Old English." Chapter 1 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1--18.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2019-06-16 Sun

■ #3702. 中英語の3人称複数対格代名詞 es はオランダ語からの借用か? (2) [personal_pronoun][laeme][lalme][me_dialect][clitic][map][dutch]

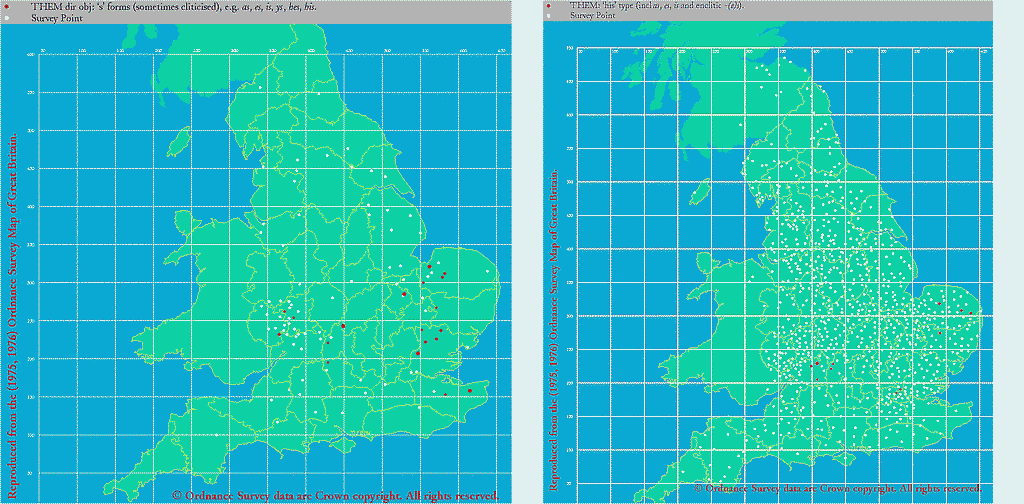

昨日の記事 ([2019-06-15-1]) に引き続き,中英語の them の代わりに用いられる es という人称代名詞形態について.Bennett and Smithers の注を引用して,およそ "SE or EMidl" に使用が偏っていると述べたが,LAEME と eLALME を用いて,初期・後期中英語における状況を確認しておこう.

LAEME では Map No. 00064420 として "THEM dir obj: 's' forms (sometimes cliticised), e.g. as, es, is, ys, hes, his." が挙げられており(下左図),eLALME では Item 8 として "THEM: 'his' type (incl as, es, is and enclitic -(e)s)." が挙げられている(下右図).ここでは縮小して掲げているので,詳しくはクリックして拡大を.

全体として例が多いわけではないが,中英語期を通じて East Midland と Southeastern を中心として,部分的には内陸の West Midland にも散見されるといった分布を示していることが分かる.

オランダ語との関連を議論するためには,当時のオランダ語話者集団のイングランドへの移民状況などの歴史社会言語学的な背景を調べる必要がある.一般的にいえば,「#3435. 英語史において低地諸語からの影響は過小評価されてきた」 ([2018-09-22-1]) でみたように,14世紀辺りには毛織物貿易の発展によりフランドルと東イングランドの関係は緊密になったことから,East Midland における es や類似形態の分布に関しては,オランダ語影響説を論じ始めることができるかもしれない.しかし,West Midland の散発的な事例については,別に考えなければならないだろう.

・ Bennett, J. A. W. and G. V. Smithers, eds. Early Middle English Verse and Prose. 2nd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1968.

2019-06-15 Sat

■ #3701. 中英語の3人称複数対格代名詞 es はオランダ語からの借用か? (1) [personal_pronoun][me_dialect][dutch][borrowing][havelok][clitic]

Bennett and Smithers 版で14世紀初頭の作品といわれる Havelok を読んでいる.East Midland 方言で書かれており,古ノルド語からの借用語を多く含んでいることが知られているが,East Midland はオランダ語からの影響も取り沙汰される地域である.

Havelok より ll. 45--52 のくだりを引用しよう.

Þanne he com þenne he were bliþe,

For hom he brouthe fele siþe

Wastels, simenels with þe horn,

Hise pokes fulle of mele an korn,

Netes flesh, shepes, and swines,

And hemp to maken of gode lines,

And stronge ropes to hise netes

(In þe se-weres he ofte setes).

最後の行は he often set them in the sea-weir を意味し,setes の -es は前行の hise netes (= "his nets") を指示する接語化された3人称複数対格の代名詞と解釈できる.要するに "them" として用いられる -es というわけだが,この形態について Bennett and Smithers (293) は注で次のように解説している.

setes: i.e. sette es 'placed them'. Es, is (ys in Hav. 1174), hes, his, hise are first recorded in England c. 1200, as the acc.pl. or fem. sg. of the pronoun of the third person, and (apart from 'Robt. of Gloucester's' Chronicle are restricted to SE or EMidl texts. This pronoun is best explained as an adoption of the comparable MDu pronoun se, which is likewise used enclitically in the reduced form -s; for a pronoun (as an essential and prominent element in the grammatical machinery of a language) would hardly have escaped record till 1200 if it had been a native word.

つまり,問題の -es は中期オランダ語の対応する形態を借用したものだということである.この説を評価するに当たっては関連する事項を慎重に調査していく必要があるが,英語史においてオランダ語の影響が過小評価されてきたことを考えると,魅力的な問題ではある.

英語史とオランダ語の関わりについては,「#3435. 英語史において低地諸語からの影響は過小評価されてきた」 ([2018-09-22-1]),「#3436. イングランドと低地帯との接触の歴史」 ([2018-09-23-1]),「#126. 7言語による英語への影響の比較」 ([2009-08-31-1]),「#2645. オランダ語から借用された馴染みのある英単語」 ([2016-07-24-1]),「#2646. オランダ借用語に関する統計」 ([2016-07-25-1]),「#140. オランダ・フラマン語から借用した指小辞 -kin」 ([2009-09-14-1]) を含め dutch の記事を参照

・ Bennett, J. A. W. and G. V. Smithers, eds. Early Middle English Verse and Prose. 2nd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1968.

2019-05-24 Fri

■ #3679. 1, 2人称代名詞では区別されない性が3人称代名詞では区別される理由 [gender][person][personal_pronoun][category][sobokunagimon][fetishism]

英語の人称代名詞体系においては,単複ともに1, 2人称では性が区別されない (I, you) が,3人称単数では区別される (he, she, it) .状況は古英語でも同じであり,性の形式上の区別は1, 2人称ではつけられないが,3人称ではつけられた.これはなぜだろうか.18世紀半ばの影響力のある文法家 Lowth (29) は次のように説明している.

The Persons speaking and spoken to, being at the same time the Subjects of the discourse, are supposed to be present; from which and other circumstances their Sex is commonly known, and needs not to be marked by distinction of Gender in their Pronouns; but the third Person or thing spoken of being absent and in many respects unknown, it is necessary that it should be marked by distinction of Gender; at least when some particular Person or thing is spoken of, which ought to be more distinctly marked: accordingly the Pronoun Singular of the Third Person hath the Three Genders, He, She, It.

1, 2人称は会話の現場にいるわけだから性別は見ればわかる.しかし,3人称はたいてい現場にいないわけなので,性別に関する情報を形式に載せるのが理に適っている,という理屈だ.3人称複数で性差がつけられない点については直接言及されていないが,3人称単数のほうが "some particular Person or thing" として性の区別をより強く要求すると言うことだろうか.

Lowth の理屈は分からないでもないが,必ずしも説得力があるわけではない.少なくとも日本語やその他の言語の状況をも説明する普遍的な説明とはなっていない.日本語では,ある意味ではむしろ1, 2人称でこそ性の区別がつけられる傾向があるともいえるからだ.

しかし,日本語と異なり,英語には明確に人称 (person) という文法範疇が認められてきた.1人称=オレ,2人称=オマエ,3人称=その他の一切合切,という1つの世界観のことだ(cf. 「#3463. 人称とは何か?」 ([2018-10-20-1]),「#3468. 人称とは何か? (2)」 ([2018-10-25-1]),「#3480. 人称とは何か? (3)」 ([2018-11-06-1])).この世界観のもとでは,ある人称の場合には,例えば性というような第2の文法範疇がより強く意識される・されないといった傾向が出てくるのは自然といえば自然だろう.そこに何か重要な区別が表わされていると感じられるからこそ,人称という文法範疇が存在しているはずだからだ.

ただし,人称にせよ性にせよ,文法範疇というものは人間の分類フェチの一種にすぎないことに注意する必要がある.フェチに,あまり合理的な説明を求めることはできないのではないかと考えている.「文法範疇=フェチ」という持論については,「#2853. 言語における性と人間の分類フェチ」 ([2017-02-17-1]),「#1868. 英語の様々な「群れ」」 ([2014-06-08-1]),「#1449. 言語における「範疇」」 ([2013-04-15-1]) などを参照.

・ Lowth, Robert. A Short Introduction to English Grammar. 1762. New ed. 1769. (英語文献翻刻シリーズ第13巻,南雲堂,1968年.9--113頁.)

2019-04-22 Mon

■ #3647. 船や国名を受ける she は古英語にあった文法性の名残ですか? [sobokunagimon][gender][personal_pronoun][personification]

新年度の「英語史」の講義が始まりました.毎年度,初回の授業では,何でもよいので英語に関する疑問,とりわけ素朴な疑問を出してくださいと呼びかけています.今回も,おかげさまで,たんまりとブログのネタが集まりました.実際には必ずしも「素朴」でもなく高度だったりするのですが,本格的に英語の先生にこんな問いを投げかけてよいのだろうか,と問うことを躊躇していたような問いでも,とにかく出してくださいと呼びかけての募集だったで,なかなかの良問が出そろいました.向こう数週間,本ブログで,そのような学生からの問いを取り上げていきたいと思います.ということで,まずは標題の疑問.

千年ほど前に話されていた古英語 (Old English) では,フランス語やドイツ語をはじめとする現在のヨーロッパ諸言語にみられる文法上の性(文法性 = grammatical gender)が健在でした.すべての名詞が男性,女性,中性のいずれかに割り振られていたのです.おそらく第2外国語として文法性のある言語を学んだことのある学生が,このことを聞いて「英語にも文法性があったのか」と驚き,そこから標題の問いへと思いを巡らせたのかと思います.確かに,現代の英語には,船を始めとする各種の乗り物や国名を指して女性代名詞 she で受ける言語習慣があります.たとえば,次の通りです.

・ Look at my sports car. Isn't she a beauty?

・ What a lovely ship! What is she called?

・ Hundreds of small boats clustered round the yacht as she sailed into Southampton docks.

・ There were over two thousand people aboard the Titanic when she left England.

・ Iraq has made it plain that she will reject the proposal by the United Nations.

・ France increased her exports by 10 per cent.

・ Britain needs new leadership if she is to help shape Europe's future.

・ After India became independent, she chose to be a member of the Commonwealth.

しかし,これは古英語にあった文法性とは無関係です.乗り物や国名を女性代名詞で受ける英語の慣習は中英語期以降に発生した比較的新しい「擬人性」というべきものであり,古英語にあった「文法性」とは直接的な関係はありません.そもそも「船」を表わす古英語 scip (= ship) は女性名詞ではなく中性名詞でしたし,bāt (= boat) にしても男性名詞でした.古英語期の後に続く中英語期の文化的・文学的な伝統に基づく,新たな種類のジェンダー付与といってよいでしょう.詳しくは,以下の記事をご覧ください.

・ 「#852. 船や国名を受ける代名詞 she (1)」 ([2011-08-27-1])

・ 「#853. 船や国名を受ける代名詞 she (2)」 ([2011-08-28-1])

・ 「#854. 船や国名を受ける代名詞 she (3)」 ([2011-08-29-1])

・ 「#1028. なぜ国名が女性とみなされてきたのか」 ([2012-02-19-1])

・ 「#1912. 船や国名を受ける代名詞 she (4)」 ([2014-07-22-1])

・ 「#1517. 擬人性」 ([2013-06-22-1])

そもそも文法性とは何なのだ,と気になる人も多いと思います.言語学的にもいろいろと議論できるのですが,私は人間の「フェチ」の一種であると考えています.「#2853. 言語における性と人間の分類フェチ」 ([2017-02-17-1]) をご参照ください.

2019-01-16 Wed

■ #3551. 初期近代英語の標準化と an/a, mine/my, in/i, on/o における n の問題 [standardisation][emode][variation][article][preposition][personal_pronoun][prosody]

近代英語期にはゆっくりと英語の標準化 (standardisation) が目指されたが,標準化とは Haugen によれば "maximum variation in function" かつ "minimum variation in form" のことである(「#2745. Haugen の言語標準化の4段階 (2)」 ([2016-11-01-1])).後者は端的にいえば,1つの単語につき1つの形式(発音・綴字)が対応しているべきであり,複数の異形態 (allomorphs) が対応していることは望ましくないという立場である.

標題の機能語のペアは,n をもつ形態が語源的ではあるが,中英語では n を脱落させた異形態も普通に用いられており,特に韻文などでは音韻や韻律の都合で便利に使い分けされる「役に立つ変異」だった.形態的に一本化するよりも,音韻的な都合のために多様な選択肢を残しておくのをよしとする言語設計だったとでも言おうか.

ところが,初期近代英語期に英語の標準化が進んでくると,それ以前とは逆に,音韻的自由を犠牲にして形態的統一を重視する言語設計が頭をもたげてくる.標題の各語は,n の有無の間で自由に揺れることを許されなくなり,いずれかの形態が標準として採用されなければならなくなったのである.n のある形態かない形態か,いずれが選ばれるかは語によって異なっていたが,不定冠詞や1人称所有代名詞のように,用いられる分布が音韻的,文法的に明確に規定されさえすれば両形態が共存することもありえた.このような個々の語の振る舞いの違いこそあれ,基本的な思想としては,自由変異としての異形態の存在を許さず,それぞれの形態に1つの決まった役割を与えるということとなった.

a や my では n のない形態が選ばれ,in や on では n のある形態が選ばれたという違いは,音韻的には説明をつけるのが難しいが,標準化による異形態の整理というより大きな言語設計の観点からは,表面的な違いにすぎないということになるだろう.この鋭い観点を提示した Schlüter (29) より,関連箇所を引用しよう.

Possibly as part of this standardization process, the phonological makeup of many high-frequency words stabilized in one way or the other. While Middle English had been an era characterized by an unprecedented flexibility in terms of the presence or absence of variable segments, Early Modern English had lost these options. A word-final <e> was no longer pronounceable as [ə]; vowel-final and consonant-final forms of the possessives my/mine, thy/thine, and of the negative no/none were increasingly limited to determiner vs. pronoun function, respectively; formerly omissible final consonants of the prepositions of, on, and in became obligatory, and the distribution of final /n/ in verbs was eventually settled (e.g. infinitive see vs. past participle seen). In ME times, this kind of variability had been exploited to optimize syllable contact at word boundaries by avoiding hiatuses and consonant clusters (e.g. my leg but min arm, i þe hous but in an hous, to see me but to seen it). The increasing fixation of word forms in Early Modern English came at the expense of phonotactic adaptability, but reduced the amount of allomorphy; in other words, phonological constraints were increasingly outweighed by morphological ones . . . .

標題の語の n の脱落した異形態については「#831. Why "an apple"?」 ([2011-08-06-1]),「#2723. 前置詞 on における n の脱落」 ([2016-10-10-1]),「#3030. on foot から afoot への文法化と重層化」 ([2017-08-13-1]) などを参照.定冠詞の話題だが,「#907. 母音の前の the の規範的発音」 ([2011-10-21-1]) の問題とも関連しそうな気がする.

・ Schlüter, Julia. "Phonology." Chapter 3 of The History of English. 4th vol. Early Modern English. Ed. Laurel J. Brinton and Alexander Bergs. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2017. 27--46.

2019-01-02 Wed

■ #3537. 17世紀のネガティヴ・ポライトネス化の社会語用論的背景 [address_term][politeness][t/v_distinction][emode][title][sociolinguistics][pragmatics][historical_pragmatics][personal_pronoun]

「#3527. 呼称のポライトネスの通時変化,代名詞はネガティヴへ,名詞はポジティヴへ」 ([2018-12-23-1]) でみたように,近代英語の呼称を用いたポライトネス戦略は,なかなか複雑なものだったようだが,椎名 (66--67) は,呼称を通時的に調べてみると貧弱化や単純化の方向が確認されるという.その社会語用論的な背景についてコメントされている箇所があるので,引用しよう.

通時的に見ると,使用される語彙や意味の変化,修飾語 (modification) の減少による address terms の構造の単純化など,幾つかの変化が見られる.原因としては,識字率の向上・郵便制度の整備・プライバシーの尊重・社会的階層構造の流動化があげられている.簡単に言うと,幅広い階級において識字率が向上すると同時に,郵便制度が完備することにより,上流階級に限られていた手紙を書く習慣が庶民にも広がり,多くの人によって頻繁に書かれるようになったことである.もう片方には,人々の階級の流動性が高まり,人々の敬称が複雑化したことがあげられる.そうした社会的・文化的な諸事情により address terms が単純化していったのである.つまり,人々の階級の変動が多い時代には,礼を失することのない安全策として negative politeness の度合いの高い address terms を使うようになっていったということである.

「安全策として」説は,2人称単数代名詞 thou/you の対立が,近代英語期にネガティヴ・ポライトネスを表わす後者の you の方向へ解消されたのがなぜかを説明するのにも,しばしば引き合いに出される (cf. 「#1336. なぜ thou ではなく you が一般化したか? (2)」 ([2012-12-23-1])).当時の社会背景を汲み取った上で再訪してみたい問題である.

・ 椎名 美智 「第3章 歴史語用論における文法化と語用化」『文法化 --- 新たな展開 ---』秋元 実治・保坂 道雄(編) 英潮社,2005年.59--74頁.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow