2016-05-24 Tue

■ #2584. 歴史英語コーパスの代表性 [representativeness][corpus][methodology][hc][register]

コーパスの代表性 (representativeness) や均衡 (balance) の問題については,「#1280. コーパスの代表性」 ([2012-10-28-1]) その他の記事で扱ってきた.古い時代の英語のコーパスを扱う場合には,現代英語コーパスに関する諸問題がそのまま当てはまるのは当然のことながら,それに上乗せしてさらに困難な問題が多く立ちはだかる.

まず,歴史英語コーパスという話題以前の問題として,コーパスの元をなす母集合のテキスト集合体そのものが,歴史の偶然により現存しているものに限られるという制約がある.碑文,写本,印刷本,音声資料などに記されて現在まで生き残り,保存されてきたものが,すべてである.また,これらの資料は存在することはわかっていても,現実的にアクセスできるかどうかは別問題である.現実的には,印刷あるいは電子形態で出版されているかどうかにかかっているだろう.それらの資料がテキストの母集合となり,運よく編纂者の選定にかかったその一部が,コーパス(主として電子形態)へと編纂されることになる.こうして成立した歴史英語コーパスは,数々の制約をかいくぐって,ようやく世に出るのであり,この時点で理想的な代表性が達成されている見込みは,残念ながら薄い.

また,歴史英語とひとくくりに言っても,実際には現代英語と同様に様々な lects や registers が区分され,その区分に応じてコーパスが編纂されるケースが多い.確かに,ある意味で汎用コーパスと呼んでもよい Helsinki Corpus のような通時コーパスや,統語情報に特化しているが異なる時代をまたぐ Penn Parsed Corpora of Historical English もあるし,使い方によっては通時コーパスとしても利用できる OED の引用文検索などがある.しかし,通常は,編纂の目的や手間に応じて,より小さな範囲のテキストに絞って編纂されるコーパスが多い.古英語コーパスや中英語コーパスなど時代によって区切ること (chronolects) もあれば ,イギリス英語やアメリカ英語などの方言別 (dialects) の場合もあるし,Chaucer や Shakespeare など特定の作家別 (idiolects) の場合もあろう.社会方言 (sociolects) 別というケースもあり得るし,使用域 (registers) に応じてコーパスを編纂するということもあり得る.使用域といっても,談話の場(ジャンルや主題),媒体(話し言葉か書き言葉か),スタイル(形式性)などに応じて,下位区分することもできる.一方,分類をあまり細かくしてしまうと,上述のように現存するテキストの量が有限であり,たいてい非常に少なかったり分布が偏っているわけだから,代表性や均衡を保つことがなおのこと困難となる.

時代別 (chronolects) の軸を中心にすえて近年の比較的大規模な歴史英語コーパスの編纂状況を概観してみると,各時代の英語の辞書・文法・方言地図のような参考資料の編纂と関連づけて編纂されたものがいくつかあることがわかる.これらは,各時代の基軸コーパスとして位置づけられるといってよいかもしれない.例えば,Dictionary of Old English Corpus (DOEC), A Linguistic Atlas of Early Middle English (LAEME), Middle English Grammar project (MEG) 等である.近代についてはコーパスというよりはテキスト・データベースというべき EEBO (Early English Books Online) も利用可能となってきているし,アメリカ英語については Corpus of Historical American English (COHA) 等の試みもある.

上に挙げた代表的で著名なもののほか,様々な切り口からの歴史英語コーパス編纂の企画が続々と現われている.その逐一については,「#506. CoRD --- 英語歴史コーパスの情報センター」 ([2010-09-15-1]) で紹介した,Helsinki 大学の VARIENG ( Research Unit for Variation, Contacts and Change in English ) プロジェクトより CoRD ( Corpus Resource Database ) を参照されたい.

ハード的にいえば,上述のように,歴史英語コーパスの代表性を巡る問題を根本的に解決するのは困難ではあるが,一方で個別コーパスの編纂は活況を呈しており,諸制約のなかで進歩感はある.今ひとつはソフト的な側面,使用者側のコーパスに対する態度に関する課題もあるように思われる.電子コーパスの時代が到来する以前にも,歴史英語の研究者は,時間を要する手作業ながらも紙媒体による「コーパス」の編纂,使用,分析を常に行なってきたのである.彼らも,私たちが意識しているほどではなかったものの,ある程度はコーパスの代表性や均衡といった問題を考えてきたのであり,解決に至らないとしても,有益な研究を継続し,知見を蓄積してきた.電子コーパス時代となって代表性や均衡の問題が目立って取り上げられるようになったが,確かにその問題自体は大切で,考え続ける必要はあるものの,明らかにしたい言語現象そのものに焦点を当て,コーパスを便利に使いこなしながらその研究を続けてゆくことがより肝要なのではないか.

2016-05-03 Tue

■ #2563. 通時言語学,共時言語学という用語を巡って [saussure][terminology][diachrony][methodology][history_of_linguistics][evolution]

「#2555. ソシュールによる言語の共時態と通時態」 ([2016-04-25-1]) で,共時態と通時態の区別について話題にした.ところで,Saussure (116--17) は Cours で,通時態と共時態の峻別を説いた段落の直後に,標題の2つの言語学の呼称について次のように論じている.

Voilà pourquoi nous distinguons deux linguistiques. Comment les désignerons-nous? Les termes qui s'offrent ne sont pas tous également propres à marquer cette distinction. Ainsi histoire et «linguistique historique» ne sont pas utilisables, car ils appellent des idées trop vagues; comme l'histoire politique comprend la description des époques aussi bien que la narration des événements, on pourrait s'imaginer qu'en décrivant des états de la langue succesifs on étudie la langue selon l'axe du temps; pour cela, il faudrait envisager séparément les phénomènes qui font passer la langue d'un état à un autre. Les termes d'évolution et de linguistique évolutive sont plus précis, et nous les emploierons souvent; par opposition on peut parler de la science des états de langue ou linguistique statique.

Mais pour mieux marquer cette opposition et ce croisement de deux ordres de phénomènes relatifs au même objet, nous préfèrons parler de linguistique synchronique et de linguistique diachronique. Est synchronique tout ce qui se rapporte à l'aspect statique de notre science, diachronique tout ce qui a trait aux évolutions. De même synchronie et diachronie désigneront respectivement un état de langue et une phase d'évolution.

ここで Saussure は用語へのこだわりを見せている.Saussure が「歴史」言語学 (linguistique historique) では曖昧だというのは,時間軸上の異なる点における状態を次々と記述することも「歴史」であれば,ある共時的体系から別の共時的体系へと時間軸に沿って進ませている現象について語ることも「歴史」であるからだ.後者の意味を表わすためには「歴史」だけでは不正確であるということだろう.そこで後者に特化した用語として "linguistic historique" の代わりに "linguistique évolutive" (対して "linguistic statique")を用いることを選んだ.さらに,2つの軸の対立を用語上で目立たせるために,"linguistique diachronique" (対して "linguistic synchronique") を採用したのである.

このような経緯で通時態と共時態の用語上の対立が確立してきたわけが,進化言語学 ("linguistique évolutive") と静態言語学 ("linguistic statique") という呼称も,個人的にはすこぶる直感的で捨てがたい気がする.

・ Saussure, Ferdinand de. Cours de linguistique générale. Ed. Tullio de Mauro. Paris: Payot & Rivages, 2005.

2016-04-28 Thu

■ #2558. 変化は言語の本質である [language_change][diachrony][saussure][methodology]

20世紀の主流派言語学では,言語は変化しないものと想定されて研究されてきた.とはいっても,言語が過去から現在にかけて変化してきた事実が否認されたたわけではない.19世紀の言語研究で詳細に示された通り,言語は常に変化してきたのであり,今も変化している.しかし,方法論上,変化するという側面――通時態――を見ないことにしていた,あるいは後回しにしていたということである.

言語学者のみならず一般の人々にとっても,言語が常に変化するという本質的な事実はあまり見えていないように思われる.言語が変化するということは確かに知っている.流行語の出現と消失は日々経験しているし,語法の変化(特に言葉遣いに関する「堕落」)はメディアや教育で頻繁に話題にされている.古典に触れれば現在の言語との差をひしひしと感じるし,英語史や日本語史という科目があることも知っている.しかし,多くの人にとって,言語変化はどちらかというと例外的な出来事であり,それが常に起こっているという感覚はないのではないか.

そのような感覚の背後には,現代人の言葉遣いに関する規範意識の強さがあるだろう.効率のよいコミュニケーションのためには,言語は易々と変わってはいけない,言葉遣いの規準は守らなければならない,という意識がある.特に書き言葉は規範的であることが多く,「一様で固定化した言語」という印象を与えやすい.現代社会において権威ある英語のような言語に対しても,多くの人々は固定的な見方をもっているようだ.英語は昔から文法や語彙のしっかり整った言語だったと思い込み,今後も変わらずに繁栄し続けるだろうと信じている.言語は原則として変化しない,あるいは変化しないほうがよいという先入観が,言語が常に変化しているという事実を見えにくくしている.

言語変化に気づきにくい別の理由としては,たいていの言語変化があまりに些細であり,進み方も緩慢であるということがある.日々の言語使用のなかで起こっている変化は,コミュニケーションを阻害しない程度の極めて軽微な逸脱であるため,ほとんど知覚されない.たとえ知覚されたとしても,重要でない逸脱であるため,すぐに意識から流れ去り,忘れてしまう.

しかし,現実には毎回の言語使用が前回の言語使用と微細に異なっているのであり,常に言語を変化させているといえるのだ.

言語学が最終的に言語の本質を明らかにすることを使命とした学問分野である以上,言語は変化するものであるという事実に対して,いつまでも目を閉じているわけにはいかない.何らかの形で,変化を本質にすえた言語学を打ち出さなければならないだろう.言語変化を組み込んだ言語学の必要性については,「#2134. 言語変化は矛盾ではない」 ([2015-03-01-1]),「#2197. ソシュールの共時態と通時態の認識論」 ([2015-05-03-1]),「#2295. 言語変化研究は言語の状態の力学である」 ([2015-08-09-1]) などの記事も参考にされたい.

2016-04-25 Mon

■ #2555. ソシュールによる言語の共時態と通時態 [saussure][diachrony][methodology][terminology][linguistics]

ソシュール以来,言語を考察する視点として異なる2つの角度が区別されてきた.共時態 (synchrony) と通時態 (diachrony) である.本ブログではこの2分法を前提とした上で,それに依拠したり,あるいは懐疑的に議論したりしてきた.この有名な2分法について,言語学用語辞典などを参照して,あらためて確認しておこう.

まず,丸山のソシュール用語解説 (309--10) には次のようにある.

synchronie/diachronie [共時態/通時態]

ある科学の対象が価値体系 (système de valeurs) として捉えられるとき,時間の軸上の一定の面における状態 (état) を共時態と呼び,その静態的事実を,時間 (temps) の作用を一応無視して記述する研究を共時言語学 (linguistique synchronique) という.これはあくまでも方法論上の視点であって,現実には,体系は刻々と移り変わるばかりか,複数の体系が重なり合って共存していることを忘れてはならない.〔中略〕これに対して,時代の移り変わるさまざまな段階で記述された共時的断面と断面を比較し,体系総体の変化を辿ろうとする研究が,通時言語学 (linguistique diachronique) であり,そこで対象とされる価値の変動 (déplacement) が通時態である.

同じく丸山 (73--74) では,ソシュールの考えを次のように解説している.

「言語学には二つの異なった科学がある.静態または共時言語学と,動態または通時言語学がそれである」.この二つの区別は,およそ価値体系を対象とする学問であれば必ずなされるべきであって,たとえば経済学と経済史が同一科学のなかでもはっきりと分かれた二分野を構成するのと同時に,言語学においても二つの領域を峻別すべきであるというのが彼〔ソシュール〕の考えであった.ソシュールはある一定時期の言語の記述を共時言語学 (linguistique synchronique),時代とともに変化する言語の記述を通時言語学 (linguistique diachronique) と呼んでいる.

Crystal の用語辞典では,pp. 469, 142 にそれぞれ見出しが立てられている.

synchronic (adj.) One of the two main temporal dimensions of LINGUISTIC investigation introduced by Ferdinand de Saussure, the other being DIACHRONIC. In synchronic linguistics, languages are studied at a theoretical point in time: one describes a 'state' of the language, disregarding whatever changes might be taking place. For example, one could carry out a synchronic description of the language of Chaucer, or of the sixteenth century, or of modern-day English. Most synchronic descriptions are of contemporary language states, but their importance as a preliminary to diachronic study has been stressed since Saussure. Linguistic investigations, unless specified to the contrary, are assumed to be synchronic; they display synchronicity.

diachronic (adj.) One of the two main temporal dimensions of LINGUISTIC investigation introduced by Ferdinand de Saussure, the other being SYNCHRONIC. In diachronic linguistics (sometimes called linguistic diachrony), LANGUAGES are studied from the point of view of their historical development --- for example, the changes which have taken place between Old and Modern English could be described in phonological, grammatical and semantic terms ('diachronic PHONOLOGY/SYNTAX/SEMANTICS'). An alternative term is HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS. The earlier study of language in historical terms, known as COMPARATIVE PHILOLOGY, does not differ from diachronic linguistics in subject-matter, but in aims and method. More attention is paid in the latter to the use of synchronic description as a preliminary to historical study, and to the implications of historical work for linguistic theory in general.

・ 丸山 圭三郎 『ソシュール小事典』 大修館,1985年.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2015-11-17 Tue

■ #2395. フランス語からの句の借用 [french][loan_translation][borrowing][contact][phraseology][proverb][methodology]

「#2351. フランス語からの句動詞の借用」 ([2015-10-04-1]) の話題と関連して,Prins の論文 "French Influence in English Phrasing" を紹介する.Prins はこの論文で,フランス語の影響が想定される英語の表現が多数あることを,豊富な具体例を挙げながら主張する.Prins の言葉をそのまま借りると,". . . besides the numerous isolated words which English has borrowed from French, there are also a great many cases in which complete phrases and turns of speech, proverbs and proverbial sayings were taken over from French and incorporated in the English language" (28) ということである.

論文の大半は,フランス語と英語の文献から集めた文脈つきの対応表現リストである.本記事では,その一覧を再現するのは控え,Prins が結論として指摘している3点を要約するにとどめたい.1点目は,フランス語由来と目される英語の句・表現が,14世紀にピークを迎えているという事実である.前の記事 ([2015-10-04-1]) で参照した Iglesias-Rábade も述べていたように,単体のフランス借用語のピークと時間的におよそ符合するという事実が重要である.ただし,Iglesias-Rábade は句の借用のピークを14世紀後半とみているのに対して,Prins は14世紀前半とみているという違いがある.Prins (81) が挙げている統計表を再現しておこう.

Period Items N. B. 1000--1100 1 1100--1200 0 1200--1300 13 (3 of which ins S. E. Leg.. c 1290) 1300--1400 29 (during the first half of the century twice as as many as during the second. Brunne comes in for 8, Cursor Mundi for 5, Chaucer for 4 items) 1400--1500 12 (of which 5 in Caxton) 1500--1600 8 1600--1700 3 1700--1800 1 1800--1900 1

次に,上掲の表に示される数の句の多くが,現代まで残っているという事実が指摘されている.現在までに廃用あるいは古風となっているものは15個にすぎず,残りの53個は現役で,"part and parcel of every day speech" (81--82) であるという.残存率は77.9%と確かに高い.

3点目として,借用された句の意味領域に注目すると,様々ではあるが,主たるところを挙げれば戦争関係が17個,騎士道が11個,法律が9個となる.文学史的にはフランス語の散文の文体が英語に恩恵を与えたのは15世紀後半といわれることが多いが,これらの表現の借用も文体的な含みがあることを考えれば,問題の恩恵は実際にはもっと早い時期から始まっていたと考えることができるかもしれない.

問題の多くの句は,フランス語の句の翻訳借用 (loan_translation) として提示されている.つまり,英語側の表現には,フランス借用語ではなく英語本来語の含まれているものが多い.そのような場合には,本当にフランス語からの「なぞり」なのか,あるいは英語で自前で作り上げられた表現なのか,確定するのが難しいケースもままある.単語単体ではなく,複数の単語を組み合わせた句や表現の借用に関する研究は,文法的な借用の研究とともに,方法として難しいところがある.

・ Prins, A. A. "French Influence in English Phrasing." Neophilologus 32 (1948): 28--39, 73--83.

2015-10-28 Wed

■ #2375. Anglo-French という補助線 (2) [semantics][semantic_change][semantic_borrowing][anglo-norman][french][lexicology][false_friend][methodology][borrowing][law_french]

昨日の記事 ([2015-10-27-1]) に引き続き,英語史研究上の Anglo-French の再評価についての話題.Rothwell は,英語語彙や中世英語文化の研究において,Anglo-French の役割をもっと重視しなければならないと力説する.研究道具としての MED の限界にも言い及ぶなど,中世英語の文献学者に意識改革を迫る主張が何度も繰り返される.フランス語彙の「借用」 (borrowing) という概念にも変革を迫っており,傾聴に値する.いくつか文章を引用したい.

The MED reveals on virtually every page the massive and conventional sense and that in literally thousands of cases forms and meanings were adopted (not 'borrowed') into English from Insular, as opposed to Continental, French. The relationship of Anglo-French with Middle English was one of merger, not of borrowing, as a direct result of the bilingualism of the literate classes in mediaeval England. (174)

The linguistic situation in mediaeval England . . . produced . . . a transfer based on the fact that generations of educated Englishmen passed daily from English into French and back again in the course of their work. Very many of the French terms they used had been developing semantically on English soil since 1066, were absorbed quite naturally with all their semantic values into the native English of those who used them and then continued to evolve in their new environment of Middle English. This is a very long way from the traditional idea of 'linguistic borrowing'. (179--80)

[I]n England . . . the social status of French meant that it was used extensively in preference to English for written records of all kinds from the twelfth to the fifteenth century. As a result, given that English was the native language of the majority of those who wrote this form of French, many hundreds of words would have been in daily use in spoken English for generations without necessarily being committed to parchment or paper, the people who used them being bilingual in varying degrees, but using only one of their two vernaculars --- French --- to set down in writing their decisions, judgements, transactions, etc., for posterity. (185)

昨日の記事では bachelor の「独身男性」の語義と apparel の「衣服」の語義の例を挙げた,もう1つ Anglo-French の補助線で解決できる事例として,Rothwell (184) の挙げている rape という語を取り上げよう.MED によると,「強姦」の意味での rāpe (n.(2)) は,英語では1425年の例が初出である.大陸のフランス語ではこの語は見いだされないのだが,Anglo-French では rap としてこの語義において13世紀末から文証される.

[A]s early as c. 1289 rape is defined in the French of the English lawyers as the forcible abduction of a woman; in c. 1292 the law defines it, again in French, as male violence against a woman's body. Therefore, for well over a century before the first attestation of 'rape' in Middle English, the law of England, expressed in French but executed by English justices, had been using these definitions throughout English society. rape is an Anglo-French term not found on the Continent. Admittedly, the Latin rapum is found even earlier than the French, but it was the widespread use of French in the actual pleading and detailed written accounts --- as distinct from the brief formal Latin record --- of cases in the English course of law from the second half of the thirteenth century onwards that has resulted in so very many English legal terms like rape having a French look about them. . . . As far as rape is concerned, there never was, in fact, a 'semantic vacuum' . . . .

Rothwell (184) は,ほかにも larceny を始め多くの法律用語に似たような状況が当てはまるだろうと述べている.中英語の語彙の研究について,まだまだやるべきことが多く残されているようだ.

・ Rothwell, W. "The Missing Link in English Etymology: Anglo-French." Medium Aevum 60 (1991): 173--96.

2015-10-27 Tue

■ #2374. Anglo-French という補助線 (1) [semantics][semantic_change][semantic_borrowing][anglo-norman][french][lexicology][false_friend][methodology]

現代英語で「独身男性」を語義の1つとしてもつ bachelor に関して,意味論上の観点から「#1908. 女性を表わす語の意味の悪化 (1)」 ([2014-07-18-1]),「#1968. 語の意味の成分分析」 ([2014-09-16-1]),「#1969. 語の意味の成分分析の問題点」 ([2014-09-17-1]) で取り上げてきた.13世紀末にフランス語から借用された当初の語義は「若い騎士;若者」だったが,そこから意味が転じて「独身男性」へ発展したとされる.

OED の bachelor, n. の語義4aによると,新しい語義での初出は Chaucer の Merchant's Tale (c1386) であり,l. 34 に "Bacheleris haue often peyne and wo." と見える.しかし,MED の bachelēr (n.) の語義1(b)によると,以下の通り,14世紀初期にまで遡る."c1325(c1300) Glo.Chron.A (Clg A.11) 701: Mi leue doȝter .. Ich þe wole marie wel .. To þe nobloste bachiler þat þin herte wile to stonde.

上記の意味変化は,対応するフランス語の単語 bachelier には生じなかったとされ,現在では英仏語の間で "false friends" (Fr. "faux amis") の関係となっている.このように,この意味変化は伝統的に英語独自の発達と考えられてきた.ところが,Rothwell (175) は,英語独自発達説に,Anglo-French というつなぎ役のキャラクターを登場させて,鋭く切り込んだ.

Chaucer's use of this common Old French term in the Modern English sense of 'unmarried man' has no parallel in literature on the Continent, but is found in Anglo-French by the first quarter of the thirteenth century in The Song of Dermot and the Earl and again in the Liber Custumarum in the early fourteenth century. It is a pointer to the fact that the development of modern English, at least as far as the lexis and syntax are concerned, cannot be adequately researched without taking into account the whole corpus of Anglo-French.

The Anglo-Norman Dictionary を調べてみると,bacheler の語義2として "unmarried man" があり,上記の出典とともに確かに例が挙げられている.英語独自の発達ではなく,ましてや大陸のフランス語の発達でもなく,実は Anglo-French における発達であり,それが英語にも移植されたにすぎないという,なんとも単純ではあるが目から鱗の落ちるような結論である.「衣服」の語義をもつ英語の apparel と,それをもたないフランス語の appareil の false friends も同様に Anglo-French 経由として説明されるという.

Rothwell の論文では,Anglo-French という「補助線」を引くことにより,英語語彙に関わる多くの事実が明らかになり,問題が解決することが力説される.英語史研究でも,フランス語といえばまずパリの標準的なフランス語変種を思い浮かべ,それを基準としてフランス借用語の問題などを論じるのが当たり前だった.しかし,Anglo-French という変種の役割を改めて正当に評価することによって,未解決とされてきた英語史上の多くの問題が解かれる可能性があると,Rothwell は説く.Rothwell のこのスタンスは,「#2349. 英語の復権期にフランス借用語が爆発したのはなぜか (2)」 ([2015-10-02-1]),「#2350. Prioress の Anglo-French の地位はそれほど低くなかった」 ([2015-10-03-1]) で参照した論文でも貫かれており,啓発的である.

・ Rothwell, W. "The Missing Link in English Etymology: Anglo-French." Medium Aevum 60 (1991): 173--96.

2015-08-17 Mon

■ #2303. 言語変化のスケジュールに関する諸問題 [schedule_of_language_change][language_change][lexical_diffusion][speed_of_change][unidirectionality][methodology][linguistics]

歴史言語学や通時言語学など言語変化を扱う領域においても,意外なことにその時間的側面を扱う研究はそれほど発展していない.言語変化は紛れもなく時間軸上に継起する出来事ではあるが,むしろそれゆえに時間という次元は前提として背景化され,それ自体への関心が育たなかったのではないか,と考えている.もちろん,語彙拡散 (lexical_diffusion) のような時間軸をも重視する議論は活発だし,それが対抗している青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) の言語変化論にも長い伝統がある.また「#1872. Constant Rate Hypothesis」 ([2014-06-12-1]) なども,言語変化を時間軸において考察している.それでも,言語変化の時間的側面についての理論化は,いまだ十分に進んでいるとは言えない.

今後の重要な研究テーマとしての言語変化の時間的側面の一切を「言語変化のスケジュール」 (schedule_of_language_change) と呼ぶことにしたい.そこには,actuation, implementation, diffusion に関する諸問題 (see 「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1])) や,言語変化の順序,速度 (speed_of_change),方向,経路,持続時間,完了に関する課題,特にそれらがどのような要因により決定されるのかという問いなどが含まれている.

昨日も引用した De Smet (6) は,言語変化の拡散について理論的に考察し,上に示した「言語変化のスケジュール」の諸問題に関心を寄せている.

. . . it is important to see that the problem of diachronic diffusion has two sides. On the one hand, we have to explain the phasedness of diffusional change---that is, to explain why diffusional change happens in stages with different environments being affected at different times, and what determines the order in which environments are affected. On the other hand, there is the more intractable question of what drives diffusion---that is, why does diffusion seem to go on and on, and what gives it its unidirectionality?

De Smet の指摘する第1の問題は,なぜ言語変化の拡散は段階的に進行し,その段階の順序を決めているものは何なのかというものだ.順序の問題とまとめてもよい.2つめは,そもそも言語変化の拡散を駆動しているものは何なのか,それを一方向に進ませる推進力は何なのかというものだ.駆動力と方向の問題といってよいだろう (see 「#2299. 拡散の駆動力3点」 ([2015-08-13-1]),「#2302. 拡散的変化の一方向性?」 ([2015-08-16-1])) .

De Smet は,段階の順序とも密接に関連する経路の問題にも触れている."diffusion follows a path of least resistance" (6) と述べていることから示唆されるように,言語変化の経路を決める要因の1つとして,共時的体系における抵抗(の多少)を念頭においていることは疑いない.言語変化のスケジュールの諸問題に迫るには,共時態と通時態の対立を乗り越える努力,コセリウのいうような "integrated synchrony" が必要なのではないか.この点については「#2295. 言語変化研究は言語の状態の力学である」 ([2015-08-09-1]) と,そこに張ったリンク先の記事を合わせて参照されたい.

・ De Smet, Hendrik. Spreading Patterns: Diffusional Change in the English System of Complementation. Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2015-08-15 Sat

■ #2301. 話し言葉と書き言葉をつなぐスペクトル [pragmatics][methodology][genre][medium][writing][register]

「#230. 話しことばと書きことばの対立は絶対的か?」 ([2009-12-13-1]) で,Koch and Oesterreicher の有名な「近いことば」と「遠いことば」のモデルを紹介した.これは,言語使用域 (register) に関連して,話し言葉や書き言葉などの談話の媒体 (medium) と,新聞記事,日記,説法,インタビューなどの談話の場 (field of discourse) とが互いにどのように連動しているかを示す1つのモデルである(使用域については「#839. register」 ([2011-08-14-1]) を参照).

また,歴史語用論における証拠の問題と関連して「#2001. 歴史語用論におけるデータ」 ([2014-10-19-1]) でも,談話の媒体と場(あるいはジャンル)の関係を表わすものとして,Jucker による図を示した.

今回はもう1つ参照用に Svartvik and Leech (200) による "A spectrum of usage linking speech with writing" を導入しよう.

'Typical speech'

↑ Face-to face conversation

│ Telephone conversation

│

│ Personal letters

│ Interviews

│ Spontaneous speeches

│

│ Romantic fiction

│ Prepared speeches (such as lectures)

│

│ Mystery and adventure fiction

│ Professional letters

│ News broadcasts

│

│ Science fiction

│ Newspaper editorials

│

│ Biographies

│ Newspaper reporting

│ Academic writing

│

↓ Official documents

'Typical writing'

Koch and Oesterreicher の図のように2次元的でもないし,Jucker の図のように階層的でもない.あくまで単純かつフラットな連続体を表わす図にすぎないので,注意して解釈する必要があるが,参照には簡便だろう.

Halliday 言語学において使用域を構成する談話の媒体,場,スタイルの3種の区分は,それぞれが精緻な連続体をなしており,しかもお互いが複雑に乗り入れをしている.すべてをまともに図示しようとすれば,何重ものスペクトルになるだろう.

話し言葉と書き言葉の問題,媒体の問題については,「#748. 話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-05-15-1]),「#849. 話し言葉と書き言葉 (2)」 ([2011-08-24-1]) ,「#1001. 話しことばと書きことば (3)」 ([2012-01-23-1]),「#1665. 話しことばと書きことば (4)」 ([2013-11-17-1]),「#1829. 書き言葉テクストの3つの機能」 ([2014-04-30-1]),「#1664. CMC (computer-mediated communication)」 ([2013-11-16-1]) をはじめ,medium の各記事を参照されたい.

・ Svartvik, Jan and Geoffrey Leech. English: One Tongue, Many Voices. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 144--49.

2015-08-12 Wed

■ #2298. Language changes, speaker innovates. [language_change][sociolinguistics][causation][invisible_hand][methodology][contact]

本ブログでは,英語史に関する記事と同じくらい言語変化 (language_change) に関する記事を書いてきた.言語変化という用語や概念を当然の前提としてきたが,この前提の背景において理解しておかなければならないことがある.それは,言語変化 (linguistic change) と話者刷新 (speaker-innovation) の区別である (Milroy 77) .言語が変化するのは,話者が言葉遣いを刷新するからである.

話者が言葉遣いを刷新したからといって,それが言語変化に直結するとは限らない.一度きりの繰り返されることのない刷新にすぎないかもしれないし,個人的な変異にとどまるかもしれない.それが言語体系のなかに定着し,言語共同体内に拡がってはじめて,言語変化が生じたといえる.時間順でいえば,話者刷新は言語変化に先行する.また,話者不在の言語変化はありえないということでもある.このことは考えてみれば自明ではあるが,私たちは「言語変化」を論じる際に,しばしば言語体系を自律したものとして扱い,話者を脇に追いやる.意識的にそのような方法論を採っているのであれば問題は少ないと思われるが,言葉遣いの刷新の主体が話者であるという事実は,常に念頭においておく必要がある.

刷新や変化の主体が話者と言語のあいだで容易にすり替わり得るのは,刷新から変化への移行に関するメカニズムがよく解明されていないからでもある.そのメカニズムの1つとして見えざる手 (invisible_hand) が提案されているが,それも含めて,今後の研究課題といってよいだろう.

似たような用語上の懸念として,話者(集団)どうしが接触しているにもかかわらず,しばしば「言語接触」 (language contact) が語られるということがある.言語接触という見方そのものに問題があるわけではないが,それに先だって常に話者接触があるという認識が肝心である.

言語変化と話者刷新の区別や話者不在の言語(変化)論については,以下の記事で話題にしてきたので,参照されたい.

「#546. 言語変化は個人の希望通りに進まない」 ([2010-10-25-1])

「#835. 機能主義的な言語変化観への批判」 ([2011-08-10-1])

「#837. 言語変化における therapy or pathogeny」 ([2011-08-12-1])

「#1168. 言語接触とは話者接触である」 ([2012-07-08-1])

「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」 ([2013-07-24-1])

「#1979. 言語変化の目的論について再考」 ([2014-09-27-1])

「#1992. Milroy による言語外的要因への擁護」 ([2014-10-10-1])

「#2005. 話者不在の言語(変化)論への警鐘」 ([2014-10-23-1])

・ Milroy, James. "A Social Model for the Interpretation of Language Change." History of Englishes. Ed. Matti Rissanen et al. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1992. 72--91.

2015-08-09 Sun

■ #2295. 言語変化研究は言語の状態の力学である [linguistics][language_change][diachrony][methodology][variation]

言語変化とは通時的な変化のことであるから,それは言語研究の通時態部門で研究されるべきものである,というのが普通の理解かもしれない.しかし,通時的な変化と共時的な変異は同一現象の異なる側面であるという解釈や,そもそもソシュールの設けた共時態と通時態の区別は妥当ではないという議論があることを考えると,言語変化研究を通時的研究あるいは歴史的研究として位置づけることも疑わしくなってくる.

言語変化研究は,共時態と通時態の境界を越えた,あるいは境界を積極的に曖昧にさせる研究領域ではないかと考えている.それは,共時態の力学,あるいは「態」という表現をあえて避ければ,状態の力学と呼ぶべきものである.この考え方は,はっきりと表現したことはなかったが,本ブログでも以下の記事などにちりばめてきた.

・ 「#1025. 共時態と通時態の関係」 ([2012-02-16-1])

・ 「#1260. 共時態と通時態の接点を巡る論争」 ([2012-10-08-1])

・ 「#2125. エルゴン,エネルゲイア,内部言語形式」 ([2015-02-20-1])

・ 「#2134. 言語変化は矛盾ではない」 ([2015-03-01-1])

・ 「#2167. "orderly heterogeneity" と diffusion」 ([2015-04-03-1])

・ 「#2197. ソシュールの共時態と通時態の認識論」 ([2015-05-03-1])

「状態の力学」としての言語変化のとらえ方は,少なからぬ論者がしばしば提唱してきたが,決して一般化しているとは言えない.「状態の力学」の謂いを直接に表現している Keller (125) から引用しよう.

. . . does a theory of change belong to the field of synchronic or diachronic linguistics? If we look again at the definition by Bally and Sechehaye, we observe that the answer can be either 'both . . . and' or 'neither . . . nor'. Now, if a question admits two contradictory propositions as answers, we can be sure that something is amiss with the concepts involved. In this case the conclusion is inevitable that the concepts 'synchrony' and 'diachrony' are not suitable for dealing with problems of language change. They are basically concepts which belong to a theory of the history of language, not to a theory of change. The concepts 'state (of being)' and 'history' are very different from those of 'stasis' and 'dynamics'. 'The past is the repository of that which has irrevocably happened and been created'; whatever belongs to history is static, but the place of dynamics is the present. A theory of change is not a theory of history, but a theory of the dynamics of a 'state'. An explanation of this type seems able to fulfil the claim for an 'integrated synchrony' made by Coseriu in 1980 in his article 'Vom Primat der Geschichte'. Its task would be to define the manner in which 'the functioning of language coincides with language change'.

・ Keller, Rudi. On Language Change: The Invisible Hand in Language. Trans. Brigitte Nerlich. London and New York: Routledge, 1994.

2015-06-30 Tue

■ #2255. 言語変化の原因を追究する価値について [causation][language_change][methodology][history]

言語変化研究に限らず,研究対象に関する5W1Hの質問のなかで最も難物なのが Why であることは論を俟たないだろう.一般に,学問研究において,最終的に知りたいのは Why の答えである.しかし,一昨日の記事「#2253. 意味変化の原因を論じるのがなぜ難しいか」 ([2015-06-28-1]) でも話題にしたように,意味変化はもとより言語変化の諸事例の原因を探り,論じるというのは想像以上の困難を伴う.論者によって,「言語変化の原因は原則として multiple causation である」とか,「言語変化に原因などない」いなど様々な立場がある (cf. 「#1986. 言語変化の multiple causation あるいは "synergy"」 ([2014-10-04-1]),「#2143. 言語変化に「原因」はない」 ([2015-03-10-1])).

言語変化の原因の追究に慎重な立場を取る者もいることは了解しているが,いかに難しい問いであろうとも,歴史言語学や言語史において Why という問いかけをやめてしまうことを弁護することはできないと私は考えている.基本的には「#1123. 言語変化の原因と歴史言語学」 ([2012-05-24-1]) で引用した Smith の態度を支持したい.Smith は,音変化に関する著書の前書き (ix--x) でも,Why を問うことの妥当性と必要性を力説している.

Some levels of language, of course, are easier to discuss in 'why?' terms than others. With regard to the lexicon, for instance, it seems fairly undeniable that the presence of French-derived vocabulary in English relates to the geographical proximity of the two languages and to historical events (the Norman Conquest, for instance), while most scholars---not of course all---hold that inflectional loss during the transition from Old to Middle English relates in some way to contact developments such as the interaction between English and Norse. Sound change, as has been acknowledged by many scholars, is perhaps a trickier phenomenon to discuss in 'why?' terms. However, this book argues that it is nevertheless possible to develop historically plausible and worthwhile accounts of the changes which have taken place in the history of English sounds, bearing in mind all necessary caveats about the status of such explanations. After all, historians of politics, economics, religion, etc., have all felt able to ask 'why?' questions: Why did the Roman Empire collapse? Why did the Reformation happen? Why did the Jacobites fail? Why did the French Revolution or the First World War take place? Why did the Russian Revolution happen when it did? Why did the Industrial Revolution take place when and where it did? All these questions are considered entirely legitimate in historiography, even if no final, unequivocal, answers are forthcoming. If historical linguistics is a branch of history---and it is an argument of this book that it is---then it seems rather perverse not to allow historical linguists to address 'why?' questions as well.

まったく同じ趣旨で,私自身も Hotta (2) で,次のように述べたことがあるので,引用しておきたい.

In historical linguistics, the importance of asking not only the "how" but also the "why" of development must be stressed. In my view the question "why" should be a natural step that follows the question of "how," but linguists have long refrained from asking "why" through academic modesty. I believe, however, that it is allowable to speak less ambitiously of conditioning factors, rather than absolute causes, of language change.

おそらく言語変化に "the cause(s)" を求めることはできない."conditioning factors" を求めようとするのが精一杯だろう.後者の追究のことを指して,私は "Why?" や「原因」という表現を用いてきたし,今後も用いていくつもりである.

・ Smith, Jeremy J. Sound Change and the History of English. Oxford: OUP, 2007.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi. "The Development of the Nominal Plural Forms in Early Middle English." PhD thesis, University of Glasgow. Glasgow, November 2005.

2015-06-28 Sun

■ #2253. 意味変化の原因を論じるのがなぜ難しいか [causation][semantic_change][methodology][language_change][history_of_linguistics][language_change][link]

この2日間の記事「#2251. Ullmann による意味変化の分類」 ([2015-06-26-1]),「#2252. Waldron による意味変化の分類」 ([2015-06-28-1]) で引用・参照した Waldron は,Stern と Ullmann などの主要な先行研究を踏まえながら,意味変化の原因についても論じている.原因についての何らかの新しい洞察を付け加えているわけではないが,原因論を巡ることがなぜ難しいのかというメタな問題について,非常に参考になる議論を展開している.

We have now considered a number of factors which may contribute to change of meaning and it is not difficult to see why so many different schemes of semantic change have been proposed over the last 150 years and why there is so little agreement among scholars as to the correct classification of the phenomena. For behind every change of meaning there lies a chain of causation which can be analysed at a number of different levels --- e.g. material, social, psychological, logical --- and at each level we should get a different answer to the question 'Why did this word change its meaning?' The position of a statistician analysing (let us suppose) the causes of death in a certain community would be somewhat similar, unless he decided beforehand what sort of causes he was going to pay attention to. For at one level of analysis, every death might presumably be regarded as a case of heart stopped beating; at different levels of analysis such categories as drowning, overwork, carbon-monoxide poisoning, typhoid, and smoke-polluted atmosphere might all be acceptable as causes; but there would be no guarantee that each death would fit into one and only one aetiological category, unless the causes were all analysed at more or less the same level. The doctor who has to insert a cause of death on a death certificate uses one of a set of terms which classify the causes on a fairly consistent level of medical diagnosis; and in matters of such complexity no system of classification for causes is serviceable unless consistency of level is observed. This, of course, is a consequence of the indeterminateness of our concept of cause: every event has many different causes.

It is quite futile, therefore, for us to attempt to distinguish which sense-changes are due to linguistic causes and which to non-linguistic causes, or which are due to material causes and which to social causes; while it would perhaps be an exaggeration to contend that any change of meaning could be regarded as the consequence, immediate or remote, of any of the recognized causes, the various causal schemes undoubtedly show a good deal of overlapping.

意味変化の原因の研究を,人の死因の究明になぞらえた点が秀逸である.原因の分析のレベルが様々にありうる以上,そこから取り出される原因そのものも多種多様であり,またしばしば互いに重なり合っていることは当然である.必然的に multiple causation を想定せざるをえないことになる.

このことは,意味変化の原因論にとどまらず,言語変化一般の原因論についてもいえるだろう.言語学史においても,言語変化の原因,理由,動機づけ(を探ること)については侃々諤々の議論がある.この問題については,本ブログから cat:language_change causation の各記事を参照されたい.その中でも,とりわけ関係するものとして以下を挙げておく (##442,1123,1173,1282,1549,1582,1584,1986,2123,2143,2151,2161) .

・ 「#442. 言語変化の原因」 ([2010-07-13-1])

・ 「#1123. 言語変化の原因と歴史言語学」 ([2012-05-24-1])

・ 「#1173. 言語変化の必然と偶然」 ([2012-07-13-1])

・ 「#1282. コセリウによる3種類の異なる言語変化の原因」 ([2012-10-30-1])

・ 「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」 ([2013-07-24-1])

・ 「#1582. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (2)」 ([2013-08-26-1])

・ 「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1])

・ 「#1986. 言語変化の multiple causation あるいは "synergy"」 ([2014-10-04-1])

・ 「#2123. 言語変化の切り口」 ([2015-02-18-1])

・ 「#2143. 言語変化に「原因」はない」 ([2015-03-10-1])

・ 「#2151. 言語変化の原因の3層」 ([2015-03-18-1])

・ 「#2161. 社会構造の変化は言語構造に直接は反映しない」 ([2015-03-28-1])

・ Waldron, R. A. Sense and Sense Development. New York: OUP, 1967.

2015-05-26 Tue

■ #2220. 中英語の中部・北部方言で語頭摩擦音有声化が起こらなかった理由 [old_norse][consonant][me_dialect][causation][language_change][methodology]

昨日の記事「#2219. vane, vat, vixen」 ([2015-05-25-1]) で,中英語の南部方言における語頭摩擦音の有声化という音変化を紹介した.中部・北部方言ではこの有声化は生じなかったため,これらの方言が基盤となって後に発達した標準英語にも,その効果は反映されていない.それだけに,南部方言から標準英語へ入った vane, vat, vixen が歴史的には異質なのである.

ある方言では生じたが別の方言では生じなかった変化というのは,音変化に限らず,非常に多く存在する.むしろ,そのような変化の有無を事後的に整理して,方言区分を設けているといったほうが,研究の手順の記述としては正確だろう.したがって,なぜ語頭摩擦音の有声化が南部にだけ生じて,中部・北部には生じなかったのかという問いは,そもそも思いつきもしなかった.あえて問うとしても,通常は,なぜ無声摩擦音が南部で有声化したのかという問題に意識が向くものであり,なぜそれが中部・北部で起こらなかったのかという疑問は生じにくい.

Knowles (41--42) は,後者のありそうにないほうの疑問を抱き,自ら "speculative" としながらも,その理由の候補として,古ノルド語における語頭の有声摩擦音の不在を挙げている.

Danish may also have influenced the pronunciation of an initial <s> or <f> in words such as fox and sing. In the Danelaw, as in North Germanic, these remain unchanged [s, f], but there is widespread evidence of the pronunciation [z, v] in the area controlled by Wessex (Poussa, 1995). The distribution is confirmed by placename evidence (Fisiak, 1994). Similar forms are found on the European mainland: for example, the <s> of German singen is pronounced [z], and the <v> of Dutch viif ('five') is more like an English [v] than [f]. Some [v]-forms have become part of Standard English: for example, vat (cf. German Faß), and vixen alongside fox, but otherwise the [s, f] forms have become general, and [z, v] survive only in isolated pockets.

参考すべき研究として以下のものが挙げられていた.

・ Poussa, P. "Ellis's 'Land of Wee': A Historico-Structural Revaluation." Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 1 (1995: 295--307).

・ Fisiak,J. "The Place-Name Evidence for the Distribution of Early Modern English Dialect Features: The Voicing of Initial /f/." Studies in Early Modern English. Ed. Dieter Kastovsky. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1994. 97--110.

当該の変化が中部・北部で起こらなかったことに関する古ノルド語の関与という可能性と,この説の妥当性は,今ここでは評価できない.しかし,この提案は,言語変化研究において理論上重要なメッセージを含んでいると考える.「#2115. 言語維持と言語変化への抵抗」 ([2015-02-10-1]) で Milroy の言語変化論を紹介したが,なぜ変化したのかと同様になぜ変化しなかったのかという疑問は,もっと問われて然るべきだろう.中英語の中部・北部方言では語頭摩擦音に関して古英語以来の現状が維持されたにすぎず,何も問うことがなさそうに見えるが,なぜ現状が維持されたのかを問う必要があるというのが Milroy 的な発想なのであり,Knowles もそのような問題に光を当てたということになる.もちろん,説の妥当性は別途検討していなければならないが,言語変化に対する逆転の発想がおもしろい.

・ Knowles, Gerry. A Cultural History of the English Language. London: Arnold, 1997.

2015-05-03 Sun

■ #2197. ソシュールの共時態と通時態の認識論 [saussure][diachrony][methodology]

ソシュールによる共時態と通時態の区別と対立については,「#866. 話者の意識に通時的な次元はあるか?」 ([2011-09-10-1]),「#1025. 共時態と通時態の関係」 ([2012-02-16-1]) と「#1076. ソシュールが共時態を通時態に優先させた3つの理由」 ([2012-04-07-1]),「#1040. 通時的変化と共時的変異」 ([2012-03-02-1]),「#1426. 通時的変化と共時的変異 (2)」 ([2013-03-23-1]),「#2134. 言語変化は矛盾ではない」 ([2015-03-01-1]) などの記事で話題にしてきた.「#1260. 共時態と通時態の接点を巡る論争」 ([2012-10-08-1]) の記事でみたように,ヤコブソンはソシュールの2分法に異議を申し立てたが,立川・山田 (42) によればヤコブソンの批判は当を得ていないという.ヤコブソンは言語を現実対象としてとらえており,その立場から,言語には共時的な側面と通時的な側面があり,両者が分かち難く結びついていると論じている.しかし,ソシュールは,言語を現実対象としてではなく認識対象としてとらえた上でこの2分法を提示しているのだ.ヤコブソンは,ソシュールの2分法の前提にある科学認識論を理解していないのだ,と.

では,ソシュールの2分法の前提にある科学認識論とは何か.それは,「語る主体の意識」である.言語について,その中にあるものが共時態,その外にあるものが通時態という認識論である.長い引用となるが,立川・山田 (43--45) のソシュール解釈に耳を傾けよう(原文の傍点は下線に替えてある).

ソシュールによれば,語る主体の意識――より正確には聴く主体の前意識――にとっては,静止した言語状態しか存在していない.言語はいま・ここでも少しずつ変化をつづけているし,ある個人の一生をつうじてもある程度は推移しているわけだが,個人はその変化をまったく意識せずに,自分は一生涯同じ言語を聴き,話していると信じている.このように,〈聴く主体の前意識〉というフィルターをつうじて得られた認識対象が〈共時態〉であり,それを逃れ去るものが〈通時態〉として定義されるのである.したがって,共時態を定義する「同時性」というのは古典物理学的な時間軸上の一点・瞬間としての同時性ではなく,〈聴く主体の前意識〉にとっての同時性,ある不特定の幅をもった主観的同時性とでもいうべきものである.それに対応して,ソシュールが語っている通時態の時間というのも古典物理学的な当質的時間ではなく,主体の共時意識を逃れ去るような,言語システムの変化・運動の原動力,差異化の力なのだ.したがって,ソシュールは根底的に新しい時間概念にもとづいて共時態/通時態の区別をおこない,これらの認識対象を構築したのであって,ヤーコブソンのように古典物理学的な時間概念(等質的な時間)にもとづいてこれを批判するようなことは,まったくのまとはずれであり,批判として成立しえないのである.このような観点からすると,最初にあげた x 軸と y 軸からなる座標のような図は,いささか誤解を与えるものであったかもしれない.じつは,ソシュール自身,おのれの画期的な時間概念をうまく説明することができず,そのような誤解の種をまいているのであって,ほとんどの言語学者はその程度の理解にとどまっている.だが,われわれは,彼の理論の「可能性の中心」を読まなければならない.

再び定義しなおそう.〈共時態〉とは,「語る主体の意識」に問うことによって取り出される言語(ラング)の静止状態のことで,これは恣意的価値のシステムを構成している.恣意的価値のシステムというのは,いいかえれば,否定的な関係体としての記号のシステム,表意的差異(=対立)のシステムということと別のことではない.それにたいして,〈通時態〉とは,「語る主体の意識」を逃れ去り,主体の無意識のうちに,時間のなかで生起する出来事の場である.〈共時態〉が主体の〈意識=前意識〉システムに与えられているのにたいして,〈通時態〉は主体の〈無意識〉システムにのみ与えられているということである.ソシュールは,両者の研究を力学の二部門と比較して,均衡状態にある力としての共時態の研究を静態学,運動しつつある力としての通時態の研究を力動学と定義している.以上から明らかなように,共時態/通時態の区別というのは,よくいわれるような言語研究における方法論上の区別などではけっしてなく,言語と主体の生成プロセスを解明するための認識論的な理論装置にほかならない.つまり,〈意識=前意識〉システムと〈無意識〉システムとに分裂した語る主体と相関的に,言語はまさにこのような《力》の二層として現われるのである

共時態と通時態は,言語という現実対象の2側面ではないし,しばしばそう解釈されているように,言語を観察する際の2つの視点でもない.そうではなく,共時態と通時態とは〈語る主体の意識〉の中にあるか外にあるかという認識の問題なのだ.立川・山田は,このようにソシュールを解釈している.

・ 立川 健二・山田 広昭 『現代言語論』 新曜社,1990年.

2015-03-01 Sun

■ #2134. 言語変化は矛盾ではない [saussure][diachrony][language_change][causation][methodology][linguistics]

最近,言語学者コセリウの言語変化論が新しく邦訳された.言語変化を研究する者にとってコセリウのことばは力強い.著書は冒頭 (19) で「言語変化という逆説」という問題に言及している(以下,傍点を太字に替えてある).

言語変化という問題は,あきらかに一つの根本的な矛盾をかかえている.そもそも,この問題を原因という角度からとりあげて,言語はなぜ変化するのか(まるで変化をしてはならないかのように)と問うこと自体,言語には本来そなわった安定性があるのに,生成発展がそれを乱し,破壊すらしてしまうのだと言いたげである.生成発展は言語の本質に反するのだと.まさにこのことが言語の逆説であるとも言われる.

この矛盾の源が,ソシュールの共時態と通時態の2分法にあることは明らかである.「#1025. 共時態と通時態の関係」 ([2012-02-16-1]) と「#1076. ソシュールが共時態を通時態に優先させた3つの理由」 ([2012-04-07-1]) で触れたとおり,ソシュールは言語研究における共時態を優先し,通時態は自らのうちに目的をもたないと明言した.以来,多くの言語学者がソシュールに従い,言語の本質は静的な体系であり,それを乱す変化というものは言語にとって矛盾以外の何ものでもないと信じてきたし,同時に不思議がってもきた.

コセリウ (22--23) は,この伝統的な言語変化矛盾論に真っ向から対抗する.コセリウによる8点の明解な指摘を引用しよう.

(a) 言語変化について言いふらされているこの逆説なるものは実際には存在せず,根本的には,はっきり言うか言わないかのちがいはあるが,言語(ラング)と「共時的投影」とを同じものと考えてしまう誤りから生ずるにすぎないこと.(b) 言語変化という問題は原因の角度からとりあげることはできないし,またそうすべきでもないこと.(c) 上に引いた主張は確かな直感にもとづいてはいるが,あいまいでどうにもとれるような解釈にゆだねられてしまったために,ただただ研究上の要請でしかないものを対象のせいにしていること.上のような主張をなす著者たちがどうにも避けがたく当面してしまう矛盾はすべてここから生じること.(d) はっきり言えば,共時態―通時態の二律背反は対象のレベルにではなく,研究のレベルに属するものであって,言語そのものにではなく,言語学にかかわるものであること.(e) ソシュールの二律背反を克服するための手がかりは,ソシュール自身のもとに――ことばの現実が,彼の前提にはおかまいなしに,また前提に反してもそこに入りこんでしまっているだけに――それを克服できるような方向で発見することが可能であるということ.(f) そうは言ってもやはり,ソシュールの考え方とそこから派生したもろもろの概念とは,その内にひそむ矛盾の克服を阻む根本的な誤りをかかえていること.(g) 「体系」と「歴史性」との間にはいかなる矛盾もなく,反対に,言語の歴史性はその体系性を含み込んでいるということ.(h) 研究のレベルにおける共時態と通時態との二律背反は,歴史においてのみ,また歴史によってのみ克服できるということ,以上である.

変化すること自体が言語の本質であり,変化することによって言語は言語であり続ける.まったく同感である.「#2123. 言語変化の切り口」 ([2015-02-18-1]) も参照.

・ E. コセリウ(著),田中 克彦(訳) 『言語変化という問題――共時態,通時態,歴史』 岩波書店,2014年.

2015-02-28 Sat

■ #2133. ことばの変化のとらえ方 [language_change][methodology][causation]

昨日の記事「#2132. ら抜き言葉,ar 抜き言葉,eru 付け言葉」 ([2015-02-27-1]) でも紹介した井上は,第8章「ことばの変化のとらえ方」で言語変化の切り口として4つの次元を提案している (196--97) .言語,空間,時間,社会の4つである.

言語の次元とは,言語を文法や語彙などからなる体系としてみる視点をいう.この視点からは,言語変化には言語体系上の原因があるということ,1つの言語変化が別の言語変化を呼びうるということなどが主張される.言語変化における体系的調整 (systemic regulation) も言語の次元の話題である (cf. 「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1])) .

空間の次元は,ことばの地域差や方言差に着目する視点である.方言分布といった静的な視点だけではなく,地方から中央,あるいは逆方向への言語項の流入といった動的な視点も含む.方言間の接触により言語変化が促進されたり伝播したりする現象に着目する.

時間の次元は,短い単位でいえば個人の一生の間での言語変化や世代間の言語差,長い単位でいえば数百年から千年にわたる言語の変化を眺める視点をいう.言語変化とは,定義上時間軸上に展開する現象であるから,時間の次元の考慮は必要不可欠だが,短い単位と長い単位とがつながっており連続体をなしているということは言語変化研究でも気づかれにくい.これらを時間の次元としてくくるというのは,重要な洞察である.

社会の次元は,社会層の間の言語差や文体意識に注目する観点である.使用域 (register) や文体 (style) の差のみならず,言語変異や言語変化そのものをどのように評価するかという視点も含む.ことばの流行,言語の乱れ,純粋主義,規範主義などが,言語変化の発現や伝播にどのような影響を及ぼすのかなども考慮すべき課題である.

井上は言語変化 (language change) をみる視点として上の4つの次元を与えたが,この4つをむしろ言語変異 (language variation) が発生し広がってゆく次元と考えるほうがわかりやすいかもしれない.もっとも,変異の存在は変化の前提であるから,つまるところ4つの次元は言語変化にも関わってくるには相違ないし,その点では言語変化の原因の4つの分類とみることもできる.いずれにせよ,よく選ばれた4つの切り口だと思う.

言語変化のモデルとしては,「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1]),「#1600. Samuels の言語変化モデル」 ([2013-09-13-1]),「#1928. Smith による言語レベルの階層モデルと動的モデル」 ([2014-08-07-1]),「#1997. 言語変化の5つの側面」 ([2014-10-15-1]),「#2012. 言語変化研究で前提とすべき一般原則7点」 ([2014-10-30-1]), 「#2123. 言語変化の切り口」 ([2015-02-18-1]) も参照.

・ 井上 史雄 『日本語ウォッチング』 岩波書店〈岩波新書〉,1999年.

2015-02-18 Wed

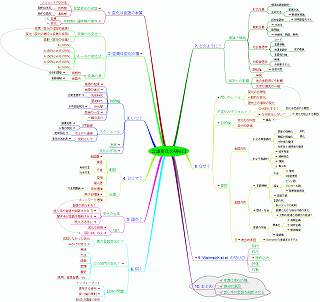

■ #2123. 言語変化の切り口 [language_change][causation][diachrony][linguistics][flash][methodology][mindmap]

言語変化について様々に論じてきたが,言語変化を考察する上での諸々の切り口,研究する上で勘案すべき種々のパラメータを整理してみたい.言語にとって変化が本質的であるならば,言語変化研究こそが言語研究の革新ともいえるはずである.

以下に言語変化の切り口を,本ブログ内へのリンクを張りつつ,10項目立てで整理した.マインドマップ風にまとめた画像,PDF,あるいはノードを開閉できるFLASHもどうぞ.記事末尾の書誌は,最も重要な3点のみに限った.以前の同様の試みとして,「#729. 言語変化のマインドマップ」 ([2011-04-26-1]) も参照.

1. 変化は言語の本質

言語変化の逆説

ソシュールの2分法

共時態

静的な体系

通時態

動的な混沌

共時態と通時態の接点

変異

変化

2. 変異は変化の種

変異から変化へ

変異(変化の潜在的資源)

変化(変化の履行=変異の採用)

拡散(変化の伝播)

A → B の変化は

A (100%)

A (80%) vs B (20%)

A (50%) vs B (50%)

A (20%) vs B (80%)

B (100%)

変異の源

言語内

体系的調整

言語外

言語接触

3. いつ?

時間幅

言語の起源

言語の進化

先史時代

比較言語学

歴史時代

世代間

子供基盤仮説

話者の一生

一瞬の流行

スケジュール

S字曲線

語彙拡散

分極の仮説

右上がり直線

定率仮説

突如として

青年文法学派

速度

変化の予測

4. どこで?

範囲

言語圏

言語

方言

地域方言

社会方言

位相

個人語

伝播

波状理論

方言周圏論

飛び石理論

ネットワーク理論

5. 誰が?

変化の主体

言語が変化する?

話し手が言語を刷新させる

聞き手が言語を刷新させる

「見えざる手」

個人

変化の採用

「弱い絆」の人

6. 何?

真の言語変化か?

成就しなかった変化

みかけの変化

どの部門の変化?

意味

文法

語彙

音韻

書記

語用,言語習慣,etc.

証拠の問題

インフォーマント

現存する資料

斉一論の原則

記述は理論に依存

7. どのように?

理論・領域

形式主義

構造主義言語学

生成文法

普遍文法

最適性理論

機能主義

認知言語学

使用基盤モデル

文法化

語用論

余剰性,頻度,費用

社会言語学

コード

言語接触

地理言語学

波状理論

言語相対論

比較言語学

再建

系統樹モデル

類型論

含意尺度

体系への影響

単発

他の言語項にも影響

大きな潮流の一端

8. なぜ?

問いのレベル

変化の合理性

一般的な変化

歴史上の個別の変化

不変化がデフォルト?

なぜ変化する?

変化を促進する要因

なぜ変化しない?

変化を阻止する要因

目的論

変化の方向性

偏流

変化の評価

要因

言語内的

およそ無意識的

調音の簡略化

同化

聴解の明確化

異化

対称性の確保

効率性と透明性の確保

およそ意識的

綴字発音

過剰修正

類推

異分析

言語外的

言語接触

干渉

借用

2言語使用

混合

ピジン語

クレオール語

基層言語仮説

言語交替

言語の死

歴史・社会

新メディアの発明

語彙における指示対象の変化

文明の発達と従属文の発達?

言語の評価

標準化

規範主義

純粋主義

監視機能

言語権

複合的原因

Samuels の言語変化モデル

9. Weinreich et al. の切り口

制約

移行

埋め込み

評価

作動

10. まとめ

変異は変化の種

複合的原因

話し手が言語を刷新させる

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

・ Smith, Jeremy J. An Historical Study of English: Function, Form and Change. London: Routledge, 1996.

・ Weinreich, Uriel, William Labov, and Marvin I. Herzog. "Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change." Directions for Historical Linguistics. Ed. W. P. Lehmann and Yakov Malkiel. U of Texas P, 1968. 95--188.

2015-02-10 Tue

■ #2115. 言語維持と言語変化への抵抗 [sociolinguistics][methodology][variety][language_change][causation]

言語変化と変異を説明するのに社会的な要因を重視する論客の1人 James Milroy の言語観については,「#1264. 歴史言語学の限界と,その克服への道」 ([2012-10-12-1]),「#1582. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (2)」 ([2013-08-26-1]),「#1992. Milroy による言語外的要因への擁護」 ([2014-10-10-1]) やその他の記事で紹介してきた.私はとりわけ言語変化の要因という問題に関心があり,社会言語学の立場からこの問題について積極的に発言している Milroy には長らく注目してきている.

Milroy は,言語変化を考察する際の3つの原則を掲げている.

Principle 1 As language use (outside of literary modes and laboratory experiments) cannot take place except in social and situational contexts and, when observed, is always observed in these contexts, our analysis --- if it is to be adequate --- must take account of society, situation and the speaker/listener. (5--6)

Principle 2 A full description of the structure of a variety (whether it is 'standard' English, or a dialect, or a style or register) can only be successfully made if quite substantial decisions, or judgements, of a social kind are taken into account in the description. (6)

Principle 3 In order to account for differential patterns of change at particular times and places, we need first to take account of those factors that tend to maintain language states and resist change. (10)

この3原則を私的に解釈すると,原則1は,言語は社会のなか使用されている状況しか観察しえないのだから,社会を考慮しない言語研究などというものはありえないという主張.原則2は,個々の言語や変種は社会言語学的にしか定義できないのだから,すべての言語研究は何らかの社会的な判断に基づいていると認識すべきだという主張.原則3は,言語変化を引き起こす要因だけではなく,言語状態を維持する要因や言語変化に抵抗する要因を探るべしという主張だ.

意外性という点で,とりわけ原則3が注目に値する.個々の言語変化の原因を探る試みは数多いが,変化せずに維持される言語項はなぜ変化しないのか,あるいはなぜ変化に抵抗するのかを問う機会は少ない.暗黙の前提として,現状維持がデフォルトであり,変化が生じたときにはその変化こそが説明されるべきだという考え方がある.しかし,Milroy は,むしろ言語変化のほうがデフォルトであり,現状維持こそが説明されるべき事象であると言わんばかりだ.

Therefore, as a historical linguist, I thought that we might get a better understanding of what linguistic change actually is, and how and why it happens, if we could also come closer to specifying the conditions under which it does not happen --- the conditions under which 'states' and forms of language are maintained and changes resisted. (11--12)

言語学的な観点からは,言語維持と言語変化への抵抗という問題意識は確かに生じにくい.変わることがデフォルトであり,変わらないことが説明を要するのだという社会言語学的な発想の転換は,傾聴すべきだと思う.

関連して,言語変化に抵抗する要因については「#430. 言語変化を阻害する要因」 ([2010-07-01-1]),「#2067. Weinreich による言語干渉の決定要因」 ([2014-12-24-1]),「#2065. 言語と文化の借用尺度 (2)」 ([2014-12-22-1]) などで少し取り上げたので,参照されたい.

・ Milroy, James. Linguistic Variation and Change: On the Historical Sociolinguistics of English. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

2015-02-08 Sun

■ #2113. 文法借用の証明 [methodology][borrowing][contact][french_influence_on_grammar]

言語間の借用といえばまず最初に語彙項目が思い浮かぶが,文法項目の借用も知られていないわけではない.文法借用が比較的まれであることは,「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1]),「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]),「#2011. Moravcsik による借用の制約」 ([2014-10-29-1]) の記事や,「#2067. Weinreich による言語干渉の決定要因」 ([2014-12-24-1]) にリンクを張った他のいくつかの記事でも取り上げてきた通りだが,古今東西の言語を見渡せば文法借用の言及もいろいろと見つかる.英語史に限っても,文法借用の可能性が示唆される事例ということでいえば,ケルト語,ラテン語,古ノルド語,フランス語などから様々な候補が挙げられてきた.

しかし,文法項目の借用は語彙項目の借用よりも同定しにくい.その理由の1つは文法項目が抽象的だからだ.語彙項目のような具体的なものであれば一方の言語から他方の言語へ移ったということが確認しやすいが,言語構造に埋め込まれた抽象的な文法項目の場合には,直接移ったのかどうか確認しにくい.理由の2つ目は,語彙項目が数万という規模で存在するのに対して,文法範疇は通言語的にも種類が比較的少なく,無関係の2つの言語に同じ文法範疇が独立して発生するということもあり得るため,借用の可能性があったとしても慎重に論じざるを得ないことだ.

Thomason (93--94) の説明を要約すると,文法借用あるいは構造的干渉 (structural interference) を証明するには,次の5点を示すことが必要である.

(1) evidence of interference elsewhere in the language's structure

(2) to identify a source language, or at least its relative language(s)

(3) to find shared structural features in the proposed source and receiving language

(4) to show that the shared features were not present in the receiving language before it came into close contact with the source language

(5) to show that the shared features were present in the source language before it came into close contact with the receiving language.

この5つの条件を満たす証拠が得られれば,A言語からB言語へ文法項目が借用されたことを説得力をもって言い切ることができるということだが,とりわけ歴史的な過程としての文法借用を問題にしている場合には,そのような証拠を揃えられる見込みは限りなくゼロに近い.というのは,証拠を揃える以前に,過去の2言語の共時的な記述と両言語をとりまく社会言語学的な状況の記述が詳細になされていなければならないからだ.

それでも,上記の5点のすべてを完全にとはいわずともある程度は満たす稀なケースはある.ただし,そのような場合にも,念のために,当該の文法項目が言語干渉の結果としてではなく,言語内的に独立して発生した可能性も考慮する必要がある.それら種々の要因を秤にかけた上で,文法借用を説明の一部とみなすのが,慎重にして穏当な立場だろう.文法借用は魅力的な話題だが,一方で慎重を要する問題である.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey. Language Contact. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2001.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow