2019-06-29 Sat

■ #3715. 音節構造に Rhyme という単位を認める根拠 [syllable][phonetics][phonology][terminology]

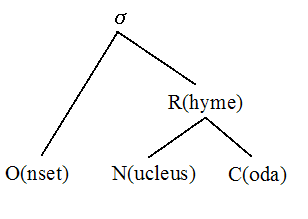

「#1563. 音節構造」 ([2013-08-07-1]) で論じたように,音韻論的には英語の音節構造として「右枝分かれ構造」 (right-branching structure) を想定することが多い.図式的に表現すれば,以下のようにまず音節 (syllable = σ) が頭子音 (onset) と韻 (rhyme) に分かれ,後者がさらに核 (nucleus) と尾子音 (coda) に分かれる構造である.

ところで,なぜこのような構造を想定するのが理論的に好都合なのだろうか.先の記事でも多少論じたが,今回は服部 (66) に従って,音声学・音韻論の観点からもう少し具体的に根拠を示そう.

英語の母音には,音節末に生起可能な開放母音と不可能な抑止母音の2種類が区別される.原則として,他の条件が同じであれば,抑止母音よりも開放母音のほうが長く発音される.また,開放母音に関しては,尾子音が後続しない場合に最も長く,次に有声尾子音が続くとき,そして無声尾子音が続くときという順序で母音の長さが短くなっていく.具体的な単語例で示せば,母音の短い順に bit < bid, beet < bead < bee と並べられることになる.

この事実を尾子音の種類に着目して言い換えれば,無声子音は有声子音よりも長く発音されるということになる.つまり,無声子音は比較的長い発音をもっているから,先行する母音はその分短く発音され,逆に有声子音は比較的短い発音をもっているから,先行する母音はその分長く発音されると解釈することができる.

このように考えると,核の母音と尾子音は長さに関して相補的・代償的な関係にあるといえる.同様の関係は頭子音と核の間には確認されないことから,上のような構造を想定するのが妥当だという結論に至るのである.

主として英語の韻文における伝統的な技巧として脚韻 (rhyme) が存在することは,それ自体では上の構造を想定する強力な根拠とはならないが,同構造が妥当であることの傍証にはなるだろう.

・ 服部 義弘 「第4章 音節・音連鎖・連続音制過程」服部 義弘(編)『音声学』朝倉日英対照言語学シリーズ 2 朝倉書店,2012年.64--83頁.

2019-04-14 Sun

■ #3639. retronym [synonym][retronym][terminology][lexicology][semantic_change][magna_carta]

昨日4月13日の朝日新聞朝刊の「ことばサプリ」という欄にレトロニムの紹介があった.レトロニムとは「新語と区別するため,呼び名をつけ直された言葉」のことで,たとえば古い「喫茶」に対する新しい「純喫茶」,同じく「服」に対する「和服」,「電話」に対する「固定電話」,「カメラ」に対する「フィルムカメラ」などの例だ.携帯電話がなかったころは電話といえば固定式の電話だけだったわけだが,携帯電話が普及してきたとき,従来の電話は「固定電話」と呼び直されることになった.時計の世界でも,新しく「デジタル時計」が現われたとき,従来の時計は「アナログ時計」と呼ばれることになった.レトロニム (retronym) とは retro- + synonym というつもりの造語だろう,これ自体がなかなかうまい呼称だし,印象に残る術語だ.

英語にもレトロニムはみられる.例えば,e-mail が現われたことによって,従来の郵便は snail mail と呼ばれることになった.acoustic guitar, manual typewriter, silent movie, landline phone なども,同様に技術革新によって生まれたレトロニムといえる.ほかに whole milk, snow skiing なども.

コンピュータ関係の世界では,技術の発展が著しいからだろう,周辺でレトロニムがとりわけ多く生まれていることが知られている.plaintext, natural language, impact printer, eyeball search, biological virus など.

歴史的な例としては,「#734. panda と Britain」 ([2011-05-01-1]),「#772. Magna Carta」 ([2011-06-08-1]) でみたように,lesser panda, Great Britain, Magna Carta などを挙げておこう.これらも一言でいえば「レトロニム」だったわけだ.術語というのは便利なものである.

2019-02-26 Tue

■ #3592. 文化の拡散を巡る migrationism と diffusionism [history][archaeology][comparative_linguistics][terminology][contact][indo-european]

印欧祖語の故地と年代を巡る論争と,祖語から派生した諸言語がいかに東西南北へ拡散していったかという論争は,連動している.比較的広く受け入れられており,伝統的な説となっているの,Gimbutas によるクルガン文化仮説である(cf. 「#637. クルガン文化と印欧祖語」 ([2011-01-24-1])).大雑把にいえば,印欧祖語は紀元前4000年頃の南ロシアのステップ地帯に起源をもち,その後,各地への移住と征服により,先行する言語を次々と置き換えていったというシナリオである.

一方,Renfrew の仮説は,Gimbutas のものとは著しく異なる.印欧祖語は先の仮説よりも数千年ほど古く(分岐開始を紀元前6000--7500年とみている),故地はアナトリアであるという.そして,派生言語の拡散は,征服によるものというよりは,新しく開発された農業技術とともにあくまで文化的に伝播したと考えている(cf. 「#1117. 印欧祖語の故地は Anatolia か?」 ([2012-05-18-1]),「#1129. 印欧祖語の分岐は紀元前5800--7800年?」 ([2012-05-30-1])).

2つの仮説について派生言語の拡散様式の対立に注目すると,前者は migrationism,後者は diffusionism の立場をとっているとみなせる.これは,言語にかぎらず広く文化の拡散について考えられ得る2つの様式である.Oppenheimer (521, 15) より,それぞれの定義をみておこう.

migrationism

The view that major cultural changes in the past were caused by movements of people from one region to another carrying their culture with them. It has displaced the earlier and more warlike term invasionism, but is itself out of archaeological favour.

diffusionism

Cultural diffusion is the movement of cultural ideas and artefacts among societies . . . . The view that major cultural innovations in the past were initiated at a single time and place (e.g. Egypt), diffusing from one society to all others, is an extreme version of the general diffusionist view --- which is that, in general, diffusion of ideas such as farming is more likely than multiple independent innovations.

印欧諸語の拡散様式ついて上記の論争があるのと同様に,アングロサクソンのイングランド征服についても似たような論争がある.一般的にいわれる,アングロサクソンの征服によって先住民族ケルト人が(ほぼ完全に)征服されたという説を巡っての論争だ.これについては明日の記事で.

・ Oppenheimer, Stephen. The Origins of the British. 2006. London: Robinson, 2007.

2019-02-19 Tue

■ #3585. aureate の例文を OED より [oed][lydgate][style][latin][aureate_diction][literature][terminology][rhetoric]

連日話題にしている "aureate termes" (あるいは aureate_diction)と関連して,OED で aureate, adj. の項を引いてみた.まず語義1として原義に近い "Golden, gold-coloured." との定義が示され,c1450からの初例が示されている.続いて語義2に,お目当ての文学・修辞学で用いられる比喩的な語義が掲載されている.

2. fig. Brilliant or splendid as gold, esp. in literary or rhetorical skill; spec. designating or characteristic of a highly ornamental literary style or diction (see quotes.).

1430 Lydgate tr. Hist. Troy Prol. And of my penne the traces to correcte Whiche barrayne is of aureat lycoure.

1508 W. Dunbar Goldyn Targe (Chepman & Myllar) in Poems (1998) I. 186 Your [Homer and Cicero's] aureate tongis both bene all to lyte For to compile that paradise complete.

1625 S. Purchas Pilgrimes ii. 1847 If I erre, I will beg indulgence of the Pope's aureat magnificence.

1819 T. Campbell Specimens Brit. Poets I. ii. 93 The prevailing fault of English diction, in the fifteenth century, is redundant ornament, and an affectation of anglicising Latin words. In this pedantry and use of 'aureate terms', the Scottish versifiers went even beyond their brethren of the south.

1908 G. G. Smith in Cambr. Hist. Eng. Lit. II. iv. 93 The chief effort was to transform the simpler word and phrase into 'aureate' mannerism, to 'illumine' the vernacular.

1919 J. C. Mendenhall Aureate Terms i. 7 Such long and supposedly elegant words have been dubbed ???aureate terms???, because..they represent a kind of verbal gilding of literary style. The phrase may be traced back..in the sense of long Latinical words of learned aspect, used to express a comparatively simple idea.

1936 C. S. Lewis Allegory of Love vi. 252 This peculiar brightness..is the final cause of the whole aureate style.

1819年, 1908年の批評的な例文からは,areate terms を虚飾的とするネガティヴな評価がうかがわれる.また,1919年の Mendenhall からの例文は,areate terms のもう1つの定義を表わしている.

遅ればせながら,この単語の語源はラテン語の aureāus (decorated with gold) である.なお,「桂冠詩人」を表わす poet laureate は aureate と脚韻を踏むが,この表現も1429年の Lydgate が初出である(ただし laureat poete の形ではより早く Chaucer に現われている).

2019-02-18 Mon

■ #3584. "The dulcet speche" としての aureate terms [lydgate][style][latin][aureate_diction][literature][terminology][rhetoric]

昨日の記事「#3583. "halff chongyd Latyne" としての aureate terms」 ([2019-02-17-1]) に引き続き,Lydgate の発展させた aureate terms という華美な文体が,同時代の批評家にどのように受け取られていたかを考えてみたい.厳密にいえば Lydgate の次世代の時代に属するが,Henry VII に仕えたイングランド詩人 Stephen Hawes (fl. 1502--21) が,The Pastime of Pleasure (1506年に完成,1509年に出版)のなかで,aureate terms のことを次のように説明している (Cap. xi, st. 2; 以下,Nichols 521fn より再引用) .

So that Elocucyon doth ryght well claryfy

The dulcet speche from the language rude,

Tellynge the tale in termes eloquent:

The barbry tongue it doth ferre exclude,

Electynge words which are expedyent,

In Latin or in Englyshe, after the entente,

Encensyng out the aromatyke fume,

Our langage rude to exyle and consume.

Hawes によれば,それは "The dulcet speche" であり,"the aromatyke fume" であり,"the language rude" の対極にあるものだったのだである.

これはラテン語風英語に対する16世紀初頭の評価だが,数十年おいて同世紀の後半になると,さらに本格的なラテン借用語の流入 --- もはや「ラテン語かぶれ」というほどの熱狂 --- が始まることになる.文体史的にも英語史的にも,Chaucer 以来続く1つの大きな流れを認めないわけにはいかない.

関連して,「#292. aureate diction」 ([2010-02-13-1]),「#1463. euphuism」 ([2013-04-29-1]) を参照.

・ Nichols, Pierrepont H. "Lydgate's Influence on the Aureate Terms of the Scottish Chaucerians." PMLA 47 (1932): 516--22.

2019-02-17 Sun

■ #3583. "halff chongyd Latyne" としての aureate terms [lydgate][chaucer][style][latin][aureate_diction][literature][terminology][rhetoric]

標題は "aureate diction" とも称される,主に15世紀に Lydgate などが発展させたラテン語の単語や語法を多用した「金ぴかな」文体である.この語法と John Lydgate (1370?--1450?) の貢献については「#292. aureate diction」 ([2010-02-13-1]),「#2657. 英語史上の Lydgate の役割」 ([2016-08-05-1]) で取り上げたことがあった.今回は "aureate terms" の定義と,それに対する同時代の反応について見てみたい.

J. C. Mendenhall は,Areate Terms: A Study in the Literary Diction of the Fifteenth Century (Thesis, U of Pennsylvania, 1919) のなかで,"those new words, chiefly Romance or Latinical in origin, continually sought under authority of criticism and the best writers, for a rich and expressive style in English, from about 1350 to about 1530" (12) と定義している.Mendenhall は,Chaucer をこの新語法の走りとみなしているが,15世紀の Chaucer の追随者,とりわけスコットランドの Robert Henryson や William Dunbar がそれを受け継いで発展させたとしている.

しかし,後に Nichols が明らかにしたように,aureate terms を大成させた最大の功労者は Lydgate といってよい.そもそも aureat(e) という形容詞を英語に導入した人物が Lydgate であるし,この形容詞自体が1つの aureate term なのである.さらに,MED の aurēāt (adj.) を引くと,驚くことに,挙げられている20例すべてが Lydgate の諸作品から取られている.

この語法が Lydgate と強く結びつけられていたことは,同時代の詩人 John Metham の批評からもわかる.Metham は,1448--49年の Romance of Amoryus and Cleopes のエピローグのなかで,詩人としての Chaucer と Lydgate を次のように評価している(以下,Nichols 520 より再引用).

(314)

And yff I the trwthe schuld here wryght,

As gret a style I schuld make in euery degre

As Chauncerys off qwene Eleyne, or Cresseyd, doth endyght;

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

(316)

For thei that greyheryd be, affter folkys estymacion,

Nedys must be more cunne, be kendly nature,

Than he that late begynnyth, as be demonstration,

My mastyr Chauncerys, I mene, that long dyd endure

In practyk off rymyng;---qwerffore proffoundely

With many prouerbys hys bokys rymyd naturally.

(317)

Eke Ion Lydgate, sumtyme monke off Byry,

Hys bokys endyted with termys off retoryk

And halff chongyd Latyne, with conseytys fantastyk,

But eke hys qwyght her schewyd, and hys late werk,

How that hys contynwaunz made hym both a poyet and a clerk.

端的にいえば,Metham は Chaucer は脚韻の詩人だが,Lydgate は aureate terms の詩人だと評しているのである.そして,引用の終わりにかけての箇所に "termys off retoryk / And halff chongyd Latyne, with conseytys fantastyk" とあるが,これはまさに areate terms の同時代的な定義といってよい.それにしても "halff chongyd Latyne" とは言い得て妙である.「#3071. Pig Latin」 ([2017-09-23-1]) を想起せずにいられない.

・ Nichols, Pierrepont H. "Lydgate's Influence on the Aureate Terms of the Scottish Chaucerians." PMLA 47 (1932): 516--22.

2019-01-08 Tue

■ #3543. 『現代英文法辞典』より optative (mood) の解説 [terminology][mood][optative][subjunctive][speech_act][auxiliary_verb]

目下 may 祈願文と関連して optative (mood) 一般について調査中だが,備忘のために荒木・安井(編)『現代英文法辞典』 (963--64) より,同用語の解説記事を引用しておきたい

optative (mood) (願望法,祈願法) インドヨーロッパ語において認められる法 (MOOD) の1つ.ギリシャ語には独自の屈折語尾を持つ願望法があるが,ラテン語やゲルマン語はでは願望法は仮定法 (SUBJUNCTIVE MOOD) と合流して1つとなった.ゲルマン語派に属する英語においては,OE以来形態的に独立した願望法はない.

願望法が表す祈願・願望の意味は英語では通例いわゆる仮定法または法助動詞 (MODAL AUXILIARY) による迂言形によって表される: God bless you! (あたなに神のみ恵みがありますように)/ May she rest in peace! (彼女の冥福を祈る)/ O were he only here. (彼がここにいてくれさえしたらよいのに).多分このため,Trnka (1930, pp. 64, 67--74) は 'subjunctive' という用語の代わりに 'optative' を用いる.Kruisinga (Handbook, II. §1531) は動詞の語幹 (STEM) の用法の1つに願望用法があることを認め,この用法の語幹を願望語幹 (optative stem) と呼ぶ: Suffice it to say .... (...と言えば十分であろう).さらに,Quirk et al. (1985, §11.39) は仮定法の一種として願望仮定法 (optative subjunctive) を認め,願望仮定法は願望を表わす少数のかなり固定した表現に使われると述べている: Far be it from me to spoil the fun. (楽しみを台無しにしようなどという気は私にはまったくない)/ God save the Queen! (女王陛下万歳!)

言語化された願望・祈願を適切に位置づけようとすると,必ず形式と機能の複雑な関係が問題となる上に,通時態と共時態の観点の違いも相俟って,非常に難しい課題となる.今ひとつの観点は,語用論的な立場から願望・祈願を発話行為 (speech_act) とみなして,この言語現象に対して何らかの位置づけを行なうことだろう.だが,語用論的な観点から行為としての願望あるいは祈願とは何なのかと問い始めると,容易に人類学的,社会学的,哲学的,宗教学的な問題へと発展してしまう.手強いテーマだ.

関連して「#3538. 英語の subjunctive 形態は印欧祖語の optative 形態から」 ([2019-01-03-1]),「#3541. 英語の法の種類 --- Jespersen による形式的な区分」 ([2019-01-06-1]),「#3540. 願望文と勧奨文の微妙な関係」 ([2019-01-05-1]) も参照.

・ 荒木 一雄,安井 稔 編 『現代英文法辞典』 三省堂,1992年.

2019-01-05 Sat

■ #3540. 願望文と勧奨文の微妙な関係 [optative][hortative][mood][terminology][subjunctive]

「#3514. 言語における「祈願」の諸相」 ([2018-12-10-1]) でも触れたように,祈願 (optative) と勧奨 (hortative) の境目は曖昧である.

寺澤 (540) によると,Poutsma の分類に基づくと,文には (1) 平叙文 (declarative sentence),(2) 疑問文 (interrogative sentence),(3) 命令文 (imperative sentence) の3つがあり,そのうち (1) の平叙文の特別なものとして (a) 感嘆文 (exclamative sentence),(b) 願望文 (optative sentence),(c) 勧奨文 (hortative sentence) が挙げられている.(1c) の勧奨文の典型例として次のようなものがある.

・ Part we (= Let us part) in friendship from your land!---W. Scott (あなたの国から仲よく別れましょう)

・ So be it! (それはそれでよい)

・ Suffice it to say . . . ((. . . といえば)十分だ)

・ Be it known! (そのことを知っておきましょう)

・ Be it understood! (そのことを理解しておきましょう)

そして,「#948. Be it never so humble, there's no place like home.」 (1)」 ([2011-12-01-1]) などで取り上げた be it ever so humble (いかに質素であろうと)も起源的には,これらの勧奨文に由来するという.現在では,上記のように仮定法現在を用いるのは定型文に限られ,let による迂言法のほうが一般的である.

しかし,予想されるところだが,願望文との区別は現実的には微妙である.形式上区別がつけやすいのは,Let's . . . . は典型的に勧奨文であり,Let us . . . . は命令文あるいは願望文であるというケースくらいだろうか.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編)『英語学要語辞典』,研究社,2002年.298--99頁.

2019-01-03 Thu

■ #3538. 英語の subjunctive 形態は印欧祖語の optative 形態から [subjunctive][indo-european][optative][mood][terminology]

古い英語における接続法 (subjunctive) の祈願用法 (optative) について印欧比較言語学の脈絡で考えようとする際に気をつけなければならないのは,印欧祖語とゲルマン語派の間にちょっとした用語の乗り入れ(と混乱)があることだ.

印欧祖語では,命令の機能を担当した "imperative", おそらく未来時制の機能を担当した "subjunctive", 祈願の機能を担当した "optative" の間で形態が区別されていた.その後,ゲルマン語派へ枝分かれしていくなかで,印欧祖語の "optative" の形態が,娘言語における接続法 (subjunctive) として受け継がれた.つまり,形態に関する限り,印欧祖語の "subjunctive" と英語を含むゲルマン諸語の "subjunctive" とは,同名を与えられているにもかかわらず無関係であるということだ.ゲルマン祖語(とそれ以下の諸言語)で "subjunctive" と呼ばれるカテゴリーは,形態的にいえば印欧祖語の "optative" を受け継いだものなのである(ややこしい!).したがって,古い英語の接続法の形式が祈願の機能を有するのは,印欧祖語からの伝統として不思議でも何でもないということになる.

ただし別の語派では事情は異なる.例えばバルト・スラヴ語派においては,印欧祖語の "optative" は「命令法」や「許可法」として継承されているようで,ますます混乱する.

では,印欧祖語のもともとの "subjunctive" はどうなってしまったかというと,ゲルマン語には継承されていないようだ.インド・イラン語派,ギリシア語,そして部分的にケルト語派では,「未来」として継承されているという.形式と機能を分けて各用語を理解しておかないと混乱は必至である.

さらに厄介なのは,何せ印欧語比較言語学のこと,Hittite などの証拠に基づき,そもそも印欧祖語には "optative" も "subjunctive" も存在しなかったのではないかという説も唱えられている (Szemerényi 337) .いやはや.

・ Fortson IV, Benjamin W. "An Approach to Semantic Change." Chapter 21 of The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Ed. Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Blackwell, 2003. 648--66.

・ Szemerényi, Oswald J. L. Introduction to Indo-European Linguistics. Trans. from Einführung in die vergleichende Sprachwissenschaft. 4th ed. 1990. Oxford: OUP, 1996.

2018-12-22 Sat

■ #3526. イディオムとは? [idiom][terminology]

イディオム (idiom) とは何か? 複数の語からなる単位で,全体の意味が各構成要素の意味の総和とはならないもの,というのが基本的な理解だろう.しかし,イディオムには他にも様々な特質がある.Chafe を引いている秋元 (38) に拠り,4つの特質を挙げてみよう.

1. イディオムの意味は各成分の意味の総和からは出てこない. ([T]he meaning of an idiom is not some kind of amalgamation of the meanings of the parts of that structure.)

2. イディオムの多くは変形操作を許さない. ([M]ost if not all idioms exhibit certain transformational deficiencies.)

3. イディオムの中には非統語的構造を持つものがある. ([T]here are some idioms which are not syntactically well-formed.)

4. イディオムがイディオム的意味と文字通りの意味を持っている場合,テキスト頻度上,前者の方が通常多い. ([A]n idiom which is well-formed will have a literal counterpart, but the text frequency of the latter is usually much lower than that of the corresponding idiom.)

2 でいわれる「変形操作」について説明しておこう.leave no legal stone unturned のように修飾語句を加えたり,touch a couple of nerves のように数量化したり,Those strings, he wouldn't pull for you のように話題化のために倒置したり,We thought tabs were being kept on us, but they weren't, のように代名詞指示できるなどの統語的操作のことである.ただし,変形操作をどの程度拒否・許容するかは個々のイディオムによって異なり,イディオムの特質とはいえ程度問題である.変形操作の許容度が低いものから高いものへ,次の3種類のイディオムがある(秋元,p. 39).

I. Fixed idioms: eat one's words, kick the bucket, make a fool of, . . .

II. Mobile idioms: break the ice, spill the beans, make much of, . . .

III. Metaphors: add fuel to the fire, make headway, pay attention, . . .

・ 秋元 実治 「第2章 文法化と意味変化」『文法化 --- 新たな展開 ---』秋元 実治・保坂 道雄(編) 英潮社,2005年.27--58頁.

・ Chafe, Wallace. "Idiomaticity as an Anomaly in the Chomskyan Paradigm". Foundations of Language 4 (1968): 107--27.

2018-12-19 Wed

■ #3523. 構文文法における構文とは? [construction_grammar][terminology][grammar][lexicon]

構文文法 (Construction Grammar) における構文 (construction) とは,その他の学派や一般でいわれる構文とは異なる独特の概念・用語である.Goldberg (4) によれば,次のように定義される.

C is a CONSTRUCTION iffdef C is a form-meaning pair <Fi, Si> such that some aspect of Fi or some aspect of Si is not strictly predictable from C's component parts or from other previously established constructions.

Goldberg (4) は次のように続ける.

Constructions are taken to be the basic units of language. Phrasal patterns are considered constructions if something about their form or meaning is not strictly predictable from the properties of their component parts or from other constructions. That is, a construction is posited in the grammar if it can be shown that its meaning and/or its form is not compositionally derived from other constructions existing in the language . . . .

要するに,形式と機能において,その言語の既存の諸要素から合成的に派生されているとみなせなければ,すべて構文であるということになる.ということは,Goldberg (4) が続けるように,次のような結論に帰着する.

In addition, expanding the pretheoretical notion of construction somewhat, morphemes are clear instances of constructions in that they are pairings of meaning and form that are not predictable from anything else . . . . It is a consequence of this definition that the lexicon is not neatly differentiated from the rest of grammar.

この定義によれば,形態素も,形態素の合成からなる語の多くも,確かに各構成要素からその形式や機能を予測できないのだから,構文ということになる.このように構文文法の特徴の1つは,生成文法などと異なり,語彙 (lexicon) と文法 (grammar) を明確に分けない点にある.

・ Goldberg, Adele E. Constructions: A Construction Grammar Approach to Argument Structure. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1995.

2018-12-16 Sun

■ #3520. 「外適応」を巡る懐疑論 [exaptation][terminology][language_change]

「#2152. Lass による外適応」 ([2015-03-19-1]) やその他の記事で紹介してきたように,近年の言語変化論では外適応 (exaptation) という用語・概念がしばしば聞かれる.Lass が進化生物学から言語学に取り込んだタームだが,その定義や有用性を巡って,賛否両論さまざまな意見が交わされてきた.Lass は屈折形態論における変化を説明するために外適応を持ち出したのだが,その考えが広まるにつれて,統語変化への適用可能性も指摘されるようになってきた.しかし,外適応の言語学への応用に懐疑的な論者も多い.Velde and Norde (1) によれば,懐疑派の論点は3つある.

まず,進化生物学の概念を言語学に応用するのは,一般的にいって賢明ではないという立場がある.生物進化と言語変化の間には相当に深い溝があり,やすやすと比較すべきではないという考え方だ.これは,言語学者のなかには,Schleicher の言語有機体に代表される19世紀の「言語=生物」という言語観へと回帰してしまうのではないかと不安を覚える者がいることを示唆しているかもしれない.

次に,そもそも進化生物学の領域においてすら,外適応は有効な概念ではないという意見がある.Lass は進化生物学をよく理解しないままに,拙速に概念を言語学に応用してしまったのではないかという批判である.

3つめに,外適応の事例とされる言語変化は,すでに他の用語や概念で十分にカバーできるものであり,新しいタームを導入する必要性はないという批判がある.例えば,古くから提案されてきたものや比較的最近のものを含めて関係の深い用語を挙げれば,regrammaticalization, degrammaticalization, functional renewal, hypoanalysis, renovation, morphologization/grammaticalization-from-below, lateral shift, refunctionalization and adfunctionalization, demorphologization, morphosyntactic emancipation, regrammation, secretion などキリがない (Velde and Norde 10--11) .ここに新たにタームを加えて混乱させるのは,いかがなものか,という意見だ.

言語変化論にとって外適応はどのように位置づけられるべきか.関心のある向きは,Norde and Velde によって編まれた外適応を巡る諸問題を論じた本格的な論文集があるので,そちらを参照されたい.

・ Velde, Freek Van de and Muriel Norde. "Exaptation: Taking Stock of a Controversial Notion in Linguistics." Exaptation and Language Change. Ed. Muriel Norde and Freek Van de Velde. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2016. 1--35.

2018-12-04 Tue

■ #3508. ソシュールの対立概念,3種 [saussure][terminology][langue][diachrony]

構造主義言語学の父というべきソシュール (Ferdinand de Saussure; 1857--1913) は,言語(研究)に関する様々な対立概念を提示した.その中でもとりわけ重要な3種の対立について,表の形でまとめておきたい(高橋・西原の pp. 3--4 より).

(1) ラング (langue) とパロール (parole) の対立

| ラング | パロル |

|---|---|

| 体系的 (systematic) | 非体系的 (not systematic) |

| 同質的 (homogeneous) | 異質的 (heterogeneous) |

| 規則支配的 (rule-governed) | 非規則支配的 (not rule-governed) |

| 社会的 (social) | 個人的 (individual) |

| 慣習的 (conventional) | 非慣習的 (not conventional) |

| 不変的 (invariable) | 変異的 (variable) |

| 無意識的 (unconscious) | 意識的 (conscious) |

(2) 形式 (form) と実体 (substance) の対立

| 形式 | 実体 |

|---|---|

| 体系 (system) | 無体系 (no system) |

| 不連続的 (discrete) | 連続的 (continuous) |

| ?????? (static) | ?????? (dynamic) |

(3) 共時性 (synchrony) と通時性 (diachrony) の対立

| 共時性 | 通時性 |

|---|---|

| 無歴史的 (ahistorical) | 歴史的 (historical) |

| ?????? (internal) | 紊???? (external) |

| 不変化的 (unchanging) | 変化的 (changing) |

| 一定の (invariable) | 変わりやすい (variable) |

| 共存的 (coexistent) | 継続的 (successive) |

ソシュールは,これらの対立を提示しながら,言語研究においては左列の諸側面を優先すべきだと考えた.つまり,ラング,形式,共時性を重視すべしと訴えたのである.

(1) の対立については「#2202. langue と parole の対比」 ([2015-05-08-1]) を,(2) については「#1074. Hjelmslev の言理学」 ([2012-04-05-1]) を参照.(3) に関しては「#3326. 通時的説明と共時的説明」 ([2018-06-05-1]) に張ったリンク先の記事をどうぞ.諸対立から不思議と立ち現れる「#3264. Saussurian Paradox」 ([2018-04-04-1]) もおもしろい.

・ 高橋 潔・西原 哲雄 「序章 言語学とは何か」西原 哲雄(編)『言語学入門』朝倉日英対照言語学シリーズ 3 朝倉書店,2012年.1--8頁.

2018-11-29 Thu

■ #3503. Gramley の英語史用語集 [terminology][hel_education]

Gramley (364--91) の英語史概説書の巻末に用語解説の "Glossary" が付いている.用語の見出しのみを抜き出したものだが簡易「英語史用語集」として使えそうなので,列挙しておく.アルファベット順でしめて400用語.Gramley の英語史は社会言語学な視点からの記述なので,その方面の用語が豊富である.テキストファイルでのアクセスはこちらからどうぞ.

abduction

ablaut

accent

accommodation

acrolect

acronym

adjective

adstrate

adverb

affricate

Afrikaans

agreement

Aitken's Law

allophone

alphabet

American Indian English (AIE)

American Indian Pidgin English

American language, the

American Vernacular

American Vulgate

Antilles, Greater

Appalachians

a-prefixing

articles

aspect

aspiration

assimilation

attrition

autochthonous language

auxiliary do

auxiliary verbs

baby-talk

back-formation

backing

basilect

bidialectalism

bilingualism

binomials

bioprogram

bleaching out

bleeding

blend

blending

borrowing

calque

Cameroon Pidgin English (CPE)

Canadian raising

case

case leveling

chain shifts

Chancery English

Chicano English (CE)

child-directed language

class

clipping

CLOTH-NORTH split

code-mixing

code-switching

codification

Colonial English

communication accommodation theory

comparative method, the

comparing pronunciation

complementizers

compounding

concord

consonant clusters

contact language

continuum

conversion

copula deletion

copular verb

core vocabulary

correctness, attitudes toward

count vs. mass

covert norm

creolization

cultural-institutional vocabulary

declension

deictic system

deixis

demonstrative

derivation

determiners

dialect

dictionaries

diglossia

diphthong

diphthongization

discourse structure

discourse particles

divergence

domain

do-periphrasis

double modals

double negation

doublets

dual

Dutch

East Africa

education

emblematic markers

English as a Foreign Language (EFL)

English as a Lingua Franca (ELF)

English as a Native Language (ENL)

English as a Second Language (ESL)

English creole languages

English pidgins

Estuary English

ethnic varieties

ethnicity

exclusive pronouns

eye dialect

face

false friends

family model

feeding

field

First Germanic Sound Shift, the

folk etymology

FOOT-STRUT Split

foreigner-talk

French

fricative

fronting

futhorc, the

gender

General American (GenAm)

General English (GenE)

generation model

Germanic languages

Germanic Sound Shifts

grammars

grammatical categories

grammaticalization

Great Vowel Shift (GVS)

Grimm's Law

Gullah

H-dropping

habitual (aspect)

hard words

Hiri Motu

historical reconstruction

hot-news perfect (aspect)

hybrid language

hypercorrection

idiom

implication relationship

inclusive pronouns

indefinite determiners

indefinite pronouns

indicator

indirect (imperative) speech acts

Indo-European language family

inflection in English

Ingvæonish

inkhorn terms

interference

interlanguage

interrogative determiners

interrogative pronouns

intersectionality

intrusive-r

invariant be

IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet)

irrealis

isogloss

iterative

jargon

kinship terms

koiné

koinéization

L-vocalization

L1

language and nation

language attitudes

language community

language contact

language death

language imposition

language loss

language planning and policy

language retention

language shift

lax

learner's language

lexeme

lexical gaps

lexical sets

lexicalization

lexifier

life-cycle theory

lingua franca

linguicism

linguistic drift

linguistic imperialism

linking-r

loan translation

loan word

London Jamaican

loss of /h/

Low Back Merger

Low Dutch

mandative subjunctive

manuals of usage

marginal language

Maritimes

marker

mass nouns

mergers

meronymy

mesolects

metathesis

middle passage

Midlands

minimal pair

modal auxiliary

modality

modes of address

monogenesis

monophthongization

monophthong

mood

morpheme

morphology

motherese

multidimensionality

multiple negation

nasal

national variety

native language

Native Speaker Englishes

nautical jargons

negative face

New England

Newfoundland

NICE

nominative you

non-rhotic

non-rhoticity

non-standard GenE

Norman French

North Sea Germanic

Northern

Northern Cities Shift

Northern Subject Rule

number

number of speakers

NURSE Merger

obstruent

OED (Oxford English Dictionary)

Old Southwest

Open-Syllable Lengthening

origins of language

orthography

overt norm

palatalization

parts of speech

past

perfect(ive) aspect

periphrastic be going to

periphrastic do

personal pronouns (, systems of)

phonemicization

phonetic symbols

phonotactics

phrasal verb

pidginization

pied piping

place-names

Plantation Creole

pleonastic subject

plosive

plural

plural {-s} and {-th}

politeness

political-social change

polygenesis

polyglossia

portmanteau word

positive face

possessive adjectives

possessive pronouns

post-nasal T-Loss

pragmatic idiom

pragmatics

pre-verbal markers

prepositions

prescriptivism

present tense {-s}

pretentious language

preterite-present verbs

primary language

principal parts

principles of vowel change

progressive (aspect)

pronoun

pronoun exchange

pronunciation change

Proto-Germanic

proto-language

punctual (aspect)

reanalysis

reduced language

reduction of strong verb forms

reduplication

reference accents

reflexive pronouns

regionalization

register

relative pronouns

relexification

rhoticity

Romance languages

RP (Received Pronunciation)

runes

runic alphabet

schwa

Scots

second person pronoun usage

semantic shift

semantic change

semi-modals

semi-rhoticity

Sheng

shibboleth

shift

shortening

Singlish

singular

solidarity and power

sound shift

South Asia

Southeast Asia

Southern Africa

Southern English

Southern shift

Southwest (England)

Spanish

specifier

speech community

spelling

spelling reform

splits

Sranan

stable, extended pidgin

Standard English (StE)

standardization

stative (aspect)

stereotype

stop

stranding

strong verbs

style

subjunctive

substrate languages

superstrate

syntax

T-flapping

tag questions

tense

tertiary hybridization

thematic roles

thematic structure

THOUGHT-NORTH-FORCE Merger

TMA

Tok Pisin

topic

topicalization

toponyms

trade language

traditional dialects

TRAP-BATH Split

trial

triglossia

typology of language]

unidimensionality

universal grammatical categories

verb classes of OE

vernacular

vernacular universals

Verner's Law

vocabulary

voicing

vowel gradation

vowel systems

wave theory

weak adjective endings

weak nouns

weak verbs

West Africa

word class

word form

word formation (processes)

word order

word stress

World Englishes

yod-dropping

zero copula

zero derivation

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

2018-11-25 Sun

■ #3499. "Standard English" と "General English" [standardisation][koine][sociolinguistics][terminology][writing][speech]

昨日の記事「#3498. hybrid Englishes」 ([2018-11-24-1]) で触れたが,"Standard English" と "General English" という2つの用語を区別すると便利なケースがあるように思われる.両者は必ずしも明確に区別できるわけではないが,概念としては対立するものと理解しておきたい.Gramley (129) は,初期近代英語期のロンドンで展開した英語の標準化 (standardisation) や共通化 (koinéisation) の動きと関連して,この2つの用語に言及している.

Although the written standard differed from the spoken language of the capital, the two together provided two national models, a highly prescriptive one, Standard English (StE), for writing and a colloquial one, which may be called General English (GenE) (cf. Wells 1982: 2ff), which is considerably less rigid. The latter was not the overt, publicly recognized standard, but the covert norm of group solidarity. It was GenE which would evolve into a supra-regional, nationwide covert standard. Both it and StE would eventually also be valid for Scotland, then Ireland, and then the English-using world beyond the British Isles.

両者の対比を整理すると以下のようになるだろうか.

| Standard English | General English | |

|---|---|---|

| Norms | overt | covert |

| Media | writing | speech |

| Prescription | more rigid | less rigid |

| Fixing/focusing | fixed | focused |

| Related process | standardisation | koinéisation |

標準化に関連する各種の用語については,「#3207. 標準英語と言語の標準化に関するいくつかの術語」 ([2018-02-06-1]) を参照.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

・ Wells, J. C. Accents of English. Vol. 1. An Introduction. Cambridge: CUP, 1982.

2018-11-24 Sat

■ #3498. hybrid Englishes [world_englishes][new_englishes][variety][sociolinguistics][terminology]

現在,世界中で現地化した○○英語が用いられており,これらは総称して "Englishes" と呼ばれている.Franglais, Singlish, Taglish などの名前で知られているものも多く,"nativized Englishes" あるいは "hybrid Englishes" とも言われる.しかし,"nativized Englishes" と "hybrid Englishes" という2つの呼称の間には,微妙なニュアンスの違いがある.Gramley (360) は "hybrid Englishes" について,次のように解説している.

Hybrid Englishes are forms of the language noticeably influenced by a non-English language. Examples include Franglais (French with English additions), Spanglish (ditto for Spanish), Singlish (Singapore English --- with substrate enrichment), TexMex (English with Spanish elements), Mix-Mix (Tagalog/Pilipino English), which may be more English (Engalog) or more Tagalog (Taglish). Such Englishes do not have the extreme structural change typical of pidgins and creoles. Rather, the non-English aspect of these hybrids depends on local systems of pronunciation and vocabulary. Marginally, they will also include structural change. The are likely, in any case, to be difficult for people to understand who are unfamiliar with both languages. In essence hybrid forms are not really different from the nativized Englishes . . .; the justification for a separate term may best be seen in the fact that hybrids are the result of covert norms while nativized Englishes are potentially to be seen on a par with StE.

"nativized Englishes" と "hybrid Englishes" は本質的には同じものを指すと考えてよいが,前者は当該社会において標準英語と同じ,あるいはそれに準ずる価値をもつとみなされている変種を含意するのに対して,後者はそのような価値をもたない変種を含意する.「#1255. "New Englishes" のライフサイクル」 ([2012-10-03-1]) や「#2472. アフリカの英語圏」 ([2016-02-02-1]) で使った用語でいえば,前者は endonormative な変種を,後者は exonormative な変種を指すといってよい.あるいは,前者は威信と結びつけられる overt norms の結果であり,後者は団結と結びつけられる covert norms の結果であるともいえる.また,この差異は,書き言葉標準英語(いわゆる Standard English) と話し言葉標準英語(いわゆる General English) の違いとも平行的であるように思われる.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

2018-11-21 Wed

■ #3495. Jespersen による滲出の例 [terminology][personal_pronoun][article]

「#3480. 膠着と滲出」 ([2018-11-14-1]) で,burger の「滲出」の例をみた.「滲出」を形態論上の問題として論じた Jespersen (384) は,次のように定義している.

By secretion I understand the phenomenon that one integral portion of a word comes to acquire a grammatical signification which it had not at first, and is then felt as something added to the word itself. Secretion thus is a consequence of a 'metanalysis' . . .; it shows its full force when the element thus secreted comes to be added to other words not originally possessing this element.

Jespersen は「滲出」の例として文法的なケースを念頭においていたようで,理解するのは意外と難しい.「滲出」の "a clear instance" として,所有代名詞 mine から n が滲出したケースを挙げているので,それを以下に解説する.

古英語では min, þin の n は語の一部であり,それ自体は特に有意味な単位ではなかった.しかし,中英語になると,後続音との関係で n の脱落する例が現われてきた.つまり,子音の前位置では n が保たれたものの,母音の前位置で n が消失する事例が増えてきた.一方,単独で「?のもの」を意味する所有代名詞として用いられる場合には,語源的な n は消えずに mine, thine などとして存続した.この段階になって,純粋に音韻的だった対立が機能的な対立へと転化され,現代的な my と mine, thy と thine の使い分けが発達することになった(関連して,不定冠詞 a と an の分化を扱った「#831. Why "an apple"?」 ([2011-08-06-1]) も参照).

さて,my, thy は上記の通り,歴史的には mine, thine の語の一部である n が脱落した結果の形ではあるが,my, thy がデフォルトの所有格と理解されるに及び,むしろそれに n を付加したものが mine, thine であるととらえられるようになった.つまり,n がどこからともなく,ある種の機能を帯びた音韻・形態として切り取られることになったのである.いったんこのような「有意味な」 n が切り取られて独立すると,これが他の数・人称・性の代名詞の所有格にも付加され,新たな所有代名詞 hisn, hern, ourn, yourn, theirn (ただし現代では非標準的)が生み出されることになった.これらは,明らかに n が「滲出」した証拠と理解することができる.

これらの -n を語尾にもつ所有代名詞については,「#2734. 所有代名詞 hers, his, ours, yours, theirs の -s」 ([2016-10-21-1]),「#2737. 現代イギリス英語における所有代名詞 hern の方言分布」 ([2016-10-24-1]) を参照.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Language: Its Nature, Development, and Origin. 1922. London: Routledge, 2007.

2018-11-14 Wed

■ #3488. 膠着と滲出 [terminology][morphology][morpheme][suffix][metanalysis][neologism][word_formation]

通時的現象としての標題の術語群について理解を深めたい.いずれも,拘束形態素 (bound morpheme) と自由形態素 (free morpheme) の間の行き来に関する用語・概念である.輿石 (111--12) より引用する.

膠着 [通時現象として] (agglutination) とは,独立した語が弱化し独立性を失って他の要素に付加する接辞になる過程を指す.たとえば,英語の friendly の接尾辞 -ly の起源は独立した名詞の līc 「体,死体」であった.

一方,この逆の過程が Jespersen (1922: 284) の滲出(しんしゅつ)(secretion) であり,元来形態論的に分析されない単位が異分析 (metanalysis) の結果,形態論的な地位を得て,接辞のような要素が創造されていく.英語では,「?製のハンバーガー」を意味する -burger,「醜聞」を意味する -gate などの要素がこの過程で生まれ,それぞれ cheeseburger, baconburger 等や Koreagate, Irangate 等の新語が形成されている.

注意したいのは,「膠着」という用語は共時形態論において,とりわけ言語類型論の分類において,別の概念を表わすことだ(「#522. 形態論による言語類型」 ([2010-10-01-1]) を参照).今回取り上げるのは,通時的な現象(言語変化)に関して用いられる「膠着」である.例として挙げられている līc → -ly は,語として独立していた自由形態素が,拘束形態素化して接尾辞となったケースである.

「滲出」も「膠着」と同じ拘束形態素化の1種だが,ソースが自由形態素ではなく,もともといかなる有意味な単位でもなかったものである点に特徴がある.例に挙げられている burger は,もともと Hamburg + er である hamburger から異分析 (metanalysis) の結果「誤って」切り出されたものだが,それが拘束形態素として定着してしまった例である.もっとも,burger は hamburger の短縮形としても用いられるので,拘束形態素からさらに進んで自由形態素化した例としても挙げることができる (cf. hamburger) .

形態素に関係する共時的術語群については「#700. 語,形態素,接辞,語根,語幹,複合語,基体」 ([2011-03-28-1]) も参照されたい.また,上で膠着の例として触れた接尾辞 -ly については「#40. 接尾辞 -ly は副詞語尾か?」 ([2009-06-07-1]),「#1032. -e の衰退と -ly の発達」,「#1036. 「姿形」と -ly」 ([2012-02-27-1]) も参考までに.滲出の他の例としては,「#97. 借用接尾辞「チック」」 ([2009-08-02-1]),「#98. 「リック」や「ニック」ではなく「チック」で切り出した理由」 ([2009-08-03-1]),「#105. 日本語に入った「チック」語」 ([2009-08-10-1]),「#538. monokini と trikini」 ([2010-10-17-1]) などを参照.

・ 輿石 哲哉 「第6章 形態変化・語彙の変遷」服部 義弘・児馬 修(編)『歴史言語学』朝倉日英対照言語学シリーズ[発展編]3 朝倉書店,2018年.106--30頁.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Language: Its Nature, Development, and Origin. 1922. London: Routledge, 2007.

2018-11-03 Sat

■ #3477. 2種類の音変化 --- 強化と弱化 [phonetics][phonology][sound_change][consonant][vowel][terminology][sonority]

音変化には,互いに逆向きの2種類のタイプがある.強化 (fortition, strengthening) と弱化 (lenition, weakening) である.各々について服部 (49) の記述を引用する.

[ 強化 ] 知覚上の観点から聞き手が理解しやすいように,隣接する分節音との対立を強めたり,個々の分節音の際立った特性を強めることをいう.発話に際し,調音エネルギーの付加を伴う.たとえば,異化 (dissimilation),長母音化 (vowel lengthening),二重母音化 (diphthongization),音添加 (addition),音節化 (syllabification),無声化 (devoicing),帯気音化 (aspiration) などがこれに含まれる.一般的に,調音時の口腔内の狭窄をせばめる方向に向かうため,子音的特性を強めることになる.

[ 弱化 ] 話し手による調音をより容易にすることをいう.強化に比べ,調音エネルギーは少なくて済む.同化 (assimilation),短母音化 (vowel shortening),単一母音化 (monophthongization),非音節化 (desyllabification),音消失 (debuccalization),有声化 (voicing),鼻音化 (nasalization),無気音化 (deaspiration),重複子音削除 (degemination) などを含む.強化とは逆に,子音性を弱め,母音性を高めることになる.

調音上の負担を少なくするという「話し手に優しい」弱化に対して,知覚上の聞き取りやすさを高めるという「聞き手に優しい」強化というペアである.会話が話し手と聞き手の役割交替によって進行し,互いに釣り合いが取れているのと平行して,音変化も弱化と強化のバランスが保たれるようになっている.どちらかのタイプ一辺倒になることはない.

服部 (49) は2種類の音変化が生じる動機づけについて「リズム構造に合わせる形で生じる」とも述べている.これについては「#3466. 古英語は母音の音量を,中英語以降は母音の音質を重視した」 ([2018-10-23-1]) を参照.

・ 服部 義弘 「第3章 音変化」 服部 義弘・児馬 修(編)『歴史言語学』朝倉日英対照言語学シリーズ[発展編]3 朝倉書店,2018年.47--70頁.

2018-08-29 Wed

■ #3411. 話し言葉,書き言葉,口語(体),文語(体) [terminology][japanese][style][speech][writing][medium][genbunicchi]

標題は,意外と混乱を招きやすい用語群である.すでに,野村に基づいて「#3314. 英語史における「言文一致運動」」 ([2018-05-24-1]) でも取り上げたが,改めて整理しておきたい.

まず,「話し言葉」と「書き言葉」の対立について.これについては多言を要しないだろう.ことばを表わす手段,すなわち媒体 (medium) の違いに注目している用語であり,音声を用いて口頭でなされるのが「話し言葉」であり,文字を用いて書記でなされるのが「書き言葉」である.それぞれの媒体に特有の事情があり,これについては,以下の各記事で扱ってきた.

・ 「#230. 話しことばと書きことばの対立は絶対的か?」 ([2009-12-13-1])

・ 「#748. 話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-05-15-1])

・ 「#849. 話し言葉と書き言葉 (2)」 ([2011-08-24-1])

・ 「#1001. 話しことばと書きことば (3)」 ([2012-01-23-1])

・ 「#1665. 話しことばと書きことば (4)」 ([2013-11-17-1])

・ 「#1829. 書き言葉テクストの3つの機能」 ([2014-04-30-1])

・ 「#2301. 話し言葉と書き言葉をつなぐスペクトル」 ([2015-08-15-1])

・ 「#3274. 話し言葉と書き言葉 (5)」 ([2018-04-14-1])

誤解を招きやすいのは「口語体」と「文語体」の対立である.それぞれ「体」を省略して「口語」「文語」と言われることも多く,これもまた誤解の種となりうる.「口語」=「話し言葉」とする用法もないではないが,基本的には「口語(体)」も「文語(体)」も書き言葉に属する概念である.書き言葉において採用される2つの異なる文体と理解するのがよい.「口語(体)」は「口語的文体の書き言葉」,「文語(体)」は「文語的文体の書き言葉」ということである.

では,「口語的文体の書き言葉」「文語的文体の書き言葉」とは何か.前者は,文法,音韻,基礎語彙からなる言語の基層について,現在日常的に話し言葉で用いられているものに基づいて書かれた言葉である(基層については「#3312. 言語における基層と表層」 ([2018-05-22-1]) を参照).私たちは現在,日常的に現代日本語の文法,音韻,基礎語彙に基づいて話している.この同じ文法,音韻,基礎語彙に基づいて日本語を表記すれば,それは「口語的文体の書き言葉」となる.それは当然のことながら「話し言葉」とそれなりに近いものにはなるが,完全に同じものではない.「話し言葉」と「書き言葉」は根本的に性質が異なるものであり,同じ基層に乗っているとはいえ,同一の出力とはならない.「話すように書く」や「書くように話す」などというが,これはあくまで比喩的な言い方であり,両者の間にはそれなりのギャップがあるものである.

一方,「文語的文体の書き言葉」とは,文法,音韻,基礎語彙などの基層として,現在常用されている言語のそれではなく,かつて常用されていた言語であるとか,威信のある他言語であるとかのそれを採用して書かれたものである.日本語の書き手は,中世以降,近代に至るまで,平安時代の日本語の基層に基づいて文章を書いてきたが,これが「文語的文体の書き言葉」である.中世の西洋諸国では,書き手の多くは,威信ある,しかし非母語であるラテン語で文章を書いた.これが西洋中世でいうところの「文語的文体の書き言葉」である.

以上をまとめれば次のようになる.

┌── (1) 話し言葉 言葉 ──┤ │ ┌── (3) 口語(体) └── (2) 書き言葉 ──┤ └── (4) 文語(体)

(1) と (2, 3, 4) は媒体の対立である.(3) と (4) は書き言葉であるという共通点をもった上での文体の対立.(1, 3) と (4) は,拠って立つ基層が,同時代の常用語のそれか否かの対立である.この辺りの問題について,詳しくは野村 (4--13) を参照されたい.

・ 野村 剛史 『話し言葉の日本史』 吉川弘文館,2011年.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow