2016-10-12 Wed

■ #2725. ghost word [lexicography][word_formation][folk_etymology][ghost_word][terminology]

ghost word (幽霊語),あるいは ghost form (幽霊形)と呼ばれるものがある.「#912. 語の定義がなぜ難しいか (3)」 ([2011-10-26-1]) で簡単に触れた程度の話題だが,今回はもう少し詳しく取り上げたい.

『英語学要語辞典』によれば,"ghost word" とは「誤記や誤解がもとで生じた本来あるべからざる語」と定義づけられている.転訛 (corruption),民間語源 (folk_etymology),類推 (analogy),非語源的綴字 (unetymological spelling) などとも関連が深い.たいていは単発的で孤立した例にとどまるが,なかには嘘から出た誠のように一般に用いられるようになったものもある.例えば,aghast は ghost, ghastly からの類推で <h> が挿入されて定着しているし,short-lived は本来は /-laɪvd/ の発音だが,/-lɪvd/ とも発音されるようになっている.

しかし,幽霊語として知られている有名な語といえば,derring-do (勇敢な行為)だろう.Chaucer の Troilus and Criseyde (l. 837) の In durryng don that longeth to a knyght (= in daring to do what is proper for a knight) の durryng don を,Spenser が名詞句と誤解し,さらにそれを Scott が継承して定着したものといわれる.

別の例として,Shakespeare は Hamlet 3: 1: 79--81 より,The undiscovered country, from whose bourne No traveller returns という表現において,bourne は本来「境界」の意味だが,Keats が文脈から「王国」と取り違え,fiery realm and airy bourne と言ったとき,bourne は幽霊語(あるいは幽霊語彙素)として用いられたことになる.このように,幽霊語は,特殊なケースではあるが,1種の語形成の産物としてとらえることができる.

なお,ghost word という用語は Skeat の造語であり (Transactions of the Philological Society, 1885--87, II. 350--51) ,その論文 ("Fourteenth Address of the President to the Philological Society") には多数の幽霊語の例が掲載されている.以下は,Skeat のことば.

1886 Skeat in Trans. Philol. Soc. (1885--7) II. 350--1 Report upon 'Ghost-words', or Words which have no real Existence..We should jealously guard against all chances of giving any undeserved record of words which had never any real existence, being mere coinages due to the blunders of printers or scribes, or to the perfervid imaginations of ignorant or blundering editors.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編)『英語学要語辞典』,研究社,2002年.298--99頁.

2016-08-11 Thu

■ #2663. 「オープン借用」と「むっつり借用」 (1) [borrowing][loan_word][semantic_borrowing][loan_translation][terminology][contact][sign]

標題は私の勝手に作った用語だが,言語項(特に語彙項目)の借用には大きく分けて「オープン借用」と「むっつり借用」の2種類があると考えている.

議論を簡単にするために,言語接触に際して最もよく観察される単語レベルの借用に限定して考えよう.通常,他言語から単語を借りてくるというときに起こることは,供給側の言語の単語という記号 (sign) が,多少の変更はあるにせよ,およそそのまま自言語にコピーされ,語彙項目として定着することである.記号とは,端的に言えば語義 (signifié) と語形 (signifiant) のセットであるから,このセットがそのままコピーされてくるということになる (「記号」については「#2213. ソシュールの記号,シニフィエ,シニフィアン」 ([2015-05-19-1]) を参照) .例えば,中英語はフランス語から uncle =「おじ」という語義と語形のセットを借りたし,中世後期の日本語はポルトガル語から tabaco (タバコ)=「煙草」のセットを借りた.

確かに,記号を語義と語形のセットで借り入れるのが最も普通の借用と考えられるが,語形は借りずに語義のみ借りてくる意味借用 (semantic_borrowing) や翻訳借用 (loan_translation) という過程もしばしば見受けられる.例えば,古英語 god は元来「ゲルマンの神」を意味したが,キリスト教に触れるに及び,対応するラテン語 deus のもっていた「キリスト教の神」の意味を借り入れ,自らに新たな語義を付け加えた.deus というラテン語の記号から借りたのは,語義のみであり,語形は本来語の god を用い続けたわけである(「#2149. 意味借用」 ([2015-03-16-1]),「#1619. なぜ deus が借用されず God が保たれたのか」 ([2013-10-02-1]) を参照).これは意味借用の例といえる.また,古英語がラテン語 trinitas を本来語要素からなる Þrines "three-ness" へと「翻訳」して取り入れたときも,ラテン語からは語義だけを拝借し,語形としてはラテン語をまるで感じさせないような具合に受け入れたのである.

ごく普通の借用と意味借用や翻訳借用などのやや特殊な借用との間で共通しているのは,少なくとも語義は相手言語から借り入れているということである.見栄えは相手言語風かもしれないし自言語風かもしれないが,いずれにせよ内容は相手言語から借りているのである.「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]) でも注意を喚起した通り,この点は重要である.いずれにせよ内容は他人から借りているという点で,等しくスケベである.ただ違うのは,相手言語の語形を伴う借用(通常の借用)では借用(スケベ)であることが一目瞭然だが,相手言語の語形を伴わない借用(意味借用や翻訳借用)では借用(スケベ)であることが表面的には分からないことである.ここから,前者を「オープン借用」,後者を「むっつり借用」と呼ぶ.

はたして,どちらがよりスケベでしょうか.そして皆さんはどちらのタイプのスケベがお好みでしょうか.

2016-08-07 Sun

■ #2659. glottochronology と lexicostatistics [glottochronology][lexicology][statistics][terminology][speed_of_change][frequency]

言語学の分野としての言語年代学 (glottochronology) と語彙統計学 (lexicostatistics) は,しばしば同義に用いられてきた.だが,glottochronology の創始者である Swadesh は,両用語を使い分けている.私自身も「#1128. glottochronology」 ([2012-05-29-1]) の記事で,両者は異なるとの前提に立ち,「glottochronology (言語年代学)は,アメリカの言語学者 Morris Swadesh (1909--67) および Robert Lees (1922--65) によって1940年代に開かれた通時言語学の1分野である.その手法は lexicostatistics (語彙統計学)と呼ばれる.」と述べた.今回は,この用語の問題について考えてみたい.

人類言語学者・社会言語学者の Hymes (4) は Swadesh に依拠しながら,両用語の区別を次のように理解している.

The terms "glottochronology" and "lexicostatistics" have often been used interchangeably. Recently several writers have proposed some sort of distinction between them . . . . I shall now distinguish them according to a suggestion by Swadesh.

Glottochronology is the study of rate of change in language, and the use of the rate for historical inference, especially for the estimation of time depths and the use of such time depths to provide a pattern of internal relationships within a language family. Lexicostatistics is the study of vocabulary statistically for historical inference. The contribution that has given rise to both terms is a glottochronologic method which is also lexicostatistic. Glottochronology based on rate of change in sectors of language other than vocabulary is conceivable, and lexicostatistic methods that do not involve rates of change or time exist . . . .

Lexicostatistics and glottochronology are thus best conceived as intersecting fields.

つまり,glottochronology と lexicostatistics は本来別物だが,両者の重なる部分,すなわち語彙統計により言語の年代を測定する部門が,いずれの分野にとっても最もよく知られた部分であるから,両者が事実上同義となっているということだ.ただし,Swadesh から80年近く経った現在では,lexicostatistics は,電子コーパスの発展により言語の年代測定とは無関係の諸問題をも扱う分野となっており,その守備範囲は広がっているといえるだろう.

上で引用した Hymes の論文は,言語における "basic vocabulary" とは何か,という根源的かつ物議を醸す問題について深く検討を加えており,一読の価値がある."basic vocabulary" は,commonness (or frequency), universality (of semantic reference), (historical) persistence のいずれかの属性,あるいはその組み合わせに基づくものと概ね受け取られているが,同論文はこの辺りの議論についても詳しい.基本語彙の問題については,「#1128. glottochronology」 ([2012-05-29-1]) や「#1965. 普遍的な語彙素」 ([2014-09-13-1]) の記事で直接に扱ったほか,「#308. 現代英語の最頻英単語リスト」 ([2010-03-01-1]),「#1089. 情報理論と言語の余剰性」 ([2012-04-20-1]),「#1091. 言語の余剰性,頻度,費用」 ([2012-04-22-1]),「#1101. Zipf's law」 ([2012-05-02-1]),「#1497. taboo が言語学的な話題となる理由 (2)」 ([2013-06-02-1]),「#1874. 高頻度語の語義の保守性」 ([2014-06-14-1]),「#1961. 基本レベル範疇」 ([2014-09-09-1]),「#1970. 多義性と頻度の相関関係」 ([2014-09-18-1]) なの記事で関与する問題に触れてきたので,そちらも参照されたい.

・ Hymes, D. H. "Lexicostatistics So Far." Current Anthropology 1 (1960): 3--44.

2016-08-01 Mon

■ #2653. 形態論を構成する部門 [terminology][morphology][morpheme][compound][derivation][inflection]

形態論 (morphology) という部門は,屈折形態論 (inflectional morphology) と派生形態論 (derivational morphology) に分けられるのが慣例である.この2分法は,「#456. 比較の -er, -est は屈折か否か」 ([2010-07-27-1]),「#1761. 屈折形態論と派生形態論の枠を取っ払う「高さ」と「高み」」 ([2014-02-21-1]) で触れたように,理論的な問題もなしではないが,現代言語学では広く前提とされている.

この2分法を基準にさらに細分化してゆくことができるが,Bauer (33) が基本的な用語群を導入しつつ形態論を構成する部門や区分を概説してくれているので,それを引用しよう.ここには,昨日の記事「#2652. 複合名詞の意味的分類」 ([2016-07-31-1]) で紹介した区分も盛り込まれている.

Morphology deals with the internal structure of word-forms. In morphology, the analyst divides word-forms into their component formatives (most of which are morphs realizing roots or affixes), and attempts to account for the occurrence of each formative. Morphology can be divided into two main branches, inflectional morphology and word-formation (also called lexical morphology). Inflectional morphology deals with the various forms of lexemes, while word-formation deals with the formation of new lexemes from given bases. Word-formation can, in turn, be subdivided into derivation and compounding (or composition). Derivation is concerned with the formation of new lexemes by affixation, compounding with the formation of new lexemes from two (or more) potential stems. Derivation is sometimes also subdivided into class-maintaining derivation and class-changing derivation. Class-maintaining derivation is the derivation of new lexemes which are of the same form class ('part of speech') as the base from which they are formed, whereas class-changing derivation produces lexemes which belong to different form classes from their bases. Compounding is usually subdivided according to the form class of the resultant compound: that is, into compound nouns, compound adjectives, etc. It may also be subdivided according to the semantic criteria . . . into exocentric, endocentric, appositional and dvandva compounds.

上の文章で説明されている形態論の分類のうち,主要な諸部門について図示しよう(Bauer (34) を少々改変して示した).

[ The Basic Divisions of Morphology ]

┌─── INFLECTIONAL

│ (deals with forms ┌─── CLASS-MAINTAINING

│ of individual lexemes) │

MORPHOLOGY ───┤ ┌─── DERIVATION ───┤

│ │ (affixation) │

│ │ └─── CLASS-CHANGING

└─── WORD-FORMATION ─────┤

(deals with │ ┌─── COMPOUND NOUNS

formation of │ │

new lexemes) └─── COMPOUNDING ───┼─── COMPOUND VERBS

(more than one │

root) └─── COMPOUND ADJECTIVES

形態論に関連する重要な術語については,「#700. 語,形態素,接辞,語根,語幹,複合語,基体」 ([2011-03-28-1]) も参照.

・ Bauer, Laurie. English Word-Formation. Cambridge: CUP, 1983.

2016-07-31 Sun

■ #2652. 複合名詞の意味的分類 [compound][word_formation][morphology][terminology][semantics][hyponymy][metonymy][metaphor][linguistics]

「#924. 複合語の分類」 ([2011-11-07-1]) で複合語 (compound) の分類を示したが,複合名詞に限り,かつ意味の観点から分類すると,(1) endocentric, (2) exocentric, (3) appositional, (4) dvandva の4種類に分けられる.Bauer (30--31) に依拠し,各々を概説しよう.

(1) endocentric compound nouns: beehive, armchair のように,複合名詞がその文法的な主要部 (hive, chair) の下位語 (hyponym) となっている例.beehive は hive の一種であり,armchair は chair の一種である.

(2) exocentric compound nouns: redskin, highbrow のような例.(1) ように複合名詞がその文法的な主要部の下位語になっているわけではない.redskin は skin の一種ではないし,highbrow は brow の一種ではない.むしろ,表現されていない意味的な主要部(この例では "person" ほど)の下位語となっているのが特徴である.したがって,metaphor や metonymy が関与するのが普通である.このタイプは,Sanskrit の文法用語をとって,bahuvrihi compound とも呼ばれる.

(3) appositional compound nouns: maidservant の類い.複合名詞は,第1要素の下位語でもあり,第2要素の下位語でもある.maidservant は maid の一種であり,servant の一種でもある.

(4) dvandva: Alsace-Lorraine, Rank-Hovis の類い.いずれが文法的な主要語が判然とせず,2つが合わさった全体を指示するもの.複合名詞は,いずれの要素の下位語であるともいえない.dvandva という名称は Sanskrit の文法用語から来ているが,英語では 'copulative compound と呼ばれることもある.

・ Bauer, Laurie. English Word-Formation. Cambridge: CUP, 1983.

2016-07-21 Thu

■ #2642. 言語変化の種類と仕組みの峻別 [terminology][language_change][causation][phonemicisation][phoneme][how_and_why]

連日 Hockett の歴史言語学用語に関する論文を引用・参照しているが,今回も同じ論文から変化の種類 (kinds) と仕組み (mechanism) の区別について Hockett の見解を要約したい.

具体的な言語変化の事例として,[f] と [v] の対立の音素化を取り上げよう.古英語では両音は1つの音素 /f/ の異音にすぎなかったが,中英語では語頭などに [v] をもつフランス単語の借用などを通じて /f/ と /v/ が音素としての対立を示すようになった.

この変化について,どのように生じたかという具体的な過程には一切触れずに,その前後の事実を比べれば,これは「音韻の変化」であると表現できる.形態の変化でもなければ,統語の変化や語彙の変化でもなく,音韻の変化であるといえる.これは,変化の種類 (kind) についての言明といえるだろう.音韻,形態,統語,語彙などの部門を区別する1つの言語理論に基づいた種類分けであるから,この言明は理論に依存する営みといってよい.前提とする理論が変われば,それに応じて変化の種類分けも変わることになる.

一方,言語変化の仕組み (mechanism) とは,[v] の音素化の例でいえば,具体的にどのような過程が生じて,異音 [v] が /f/ と対立する /v/ の音素の地位を得たのかという過程の詳細のことである.ノルマン征服が起こって,英語が [v] を語頭などにもつフランス単語と接触し,それを取り入れるに及んで,語頭に [f] をもつ語との最小対が成立し,[v] の音素化が成立した云々ということである(この音素化の実際の詳細については,「#1222. フランス語が英語の音素に与えた小さな影響」 ([2012-08-31-1]),「#2219. vane, vat, vixen」 ([2015-05-25-1]) などの記事を参照).仕組みにも様々なものが区別されるが,例えば音変化 (sound change),類推 (analogy),借用 (borrowing) の3つの区別を設定するとき,今回のケースで主として関与している仕組みは,借用となるだろう.いくつの仕組みを設定するかについても理論的に多様な立場がありうるので,こちらも理論依存の営みではある.

言語変化の種類と仕組みを区別すべきであるという Hockett の主張は,言語変化のビフォーとアフターの2端点の関係を種類へ分類することと,2端点の間で作用したメカニズムを明らかにすることとが,異なる営みであるということだ.各々の営みについて一組の概念や用語のセットが完備されているべきであり,2つのものを混同してはならない.Hockett (72) 曰く,

My last terminological recommendation, then, is that any individual scholar who has occasion to talk about historical linguistics, be it in an elementary class or textbook or in a more advanced class or book about some specific language, distinguish clearly between kinds and mechanisms. We must allow for differences of opinion as to how many kinds there are, and as to how many mechanisms there are---this is an issue which will work itself out in the future. But we can at least insist on the main point made here.

関連して,Hockett (73) は,言語変化の仕組み (mechanism) と原因 (cause) という用語についても,注意を喚起している.

'Mechanism' and 'cause' should not be confused. The term 'cause' is perhaps best used of specific sequences of historical events; a mechanism is then, so to speak, a kind of cause. One might wish to say that the 'cause' of the phonologization of the voiced-voiceless opposition for English spirants was the Norman invasion, or the failure of the British to repel it, or the drives which led the Normans to invade, or the like. We can speak with some sureness about the mechanism called borrowing; discussion of causes is fraught with peril.

Hockett の議論は,言語変化の what (= kind) と how (= mechanism) と why (= cause) の用語遣いについて改めて考えさせてくれる機会となった.

・ Hockett, Charles F. "The Terminology of Historical Linguistics." Studies in Linguistics 12.3--4 (1957): 57--73.

2016-07-19 Tue

■ #2640. 英語史の時代区分が招く誤解 [terminology][periodisation][language_myth][speed_of_change][language_change][hel_education][historiography][punctuated_equilibrium][evolution]

「#2628. Hockett による英語の書き言葉と話し言葉の関係を表わす直線」 ([2016-07-07-1]) (及び補足的に「#2629. Curzan による英語の書き言葉と話し言葉の関係の歴史」 ([2016-07-08-1]))の記事で,Hockett (65) の "Timeline of Written and Spoken English" の図を Curzan 経由で再現して,その意味を考えた.その後,Hockett の原典で該当する箇所に当たってみると,Hockett 自身の力点は,書き言葉と話し言葉の距離の問題にあるというよりも,むしろ話し言葉において変化が常に生じているという事実にあったことを確認した.そして,Hockett が何のためにその事実を強調したかったかというと,人為的に設けられた英語史上の時代区分 (periodisation) が招く諸問題に注意喚起するためだったのである.

古英語,中英語,近代英語などの時代区分を前提として英語史を論じ始めると,初学者は,あたかも区切られた各時代の内部では言語変化が(少なくとも著しくは)生じていないかのように誤解する.古英語は数世紀にわたって変化の乏しい一様の言語であり,それが11世紀に急激に変化に特徴づけられる「移行期」を経ると,再び落ち着いた安定期に入り中英語と呼ばれるようになる,等々.

しかし,これは誤解に満ちた言語変化観である.実際には,古英語期の内部でも,「移行期」でも,中英語期の内部でも,言語変化は滔々と流れる大河の如く,それほど大差ない速度で常に続いている.このように,およそ一定の速度で変化していることを表わす直線(先の Hockett の図でいうところの右肩下がりの直線)の何地点かにおいて,人為的に時代を区切る垂直の境界線を引いてしまうと,初学者の頭のなかでは真正の直線イメージが歪められ,安定期と変化期が繰り返される階段型のイメージに置き換えられてしまう恐れがある.

Hockett (62--63) 自身の言葉で,時代区分の危険性について語ってもらおう.

Once upon a time there was a language which we call Old English. It was spoken for a certain number of centuries, including Alfred's times. It was a consistent and coherent language, which survived essentially unchanged for its period. After a while, though, the language began to disintegrate, or to decay, or to break up---or, at the very least, to change. This period of relatively rapid change led in due time to the emergence of a new well-rounded and coherent language, which we label Middle English; Middle English differed from Old English precisely by virtue of the extensive restructuring which had taken place during the period of transition. Middle English, in its turn, endured for several centuries, but finally it also was broken up and reorganized, the eventual result being Modern English, which is what we still speak.

One can ring various changes on this misunderstanding; for example, the periods of stability can be pictured as relatively short and the periods of transition relatively long, or the other way round. It does not occur to the layman, however, to doubt that in general a period of stability and a period of transition can be distinguished; it does not occur to him that every stage in the history of a language is perhaps at one and the same time one of stability and also one of transition. We find the contrast between relative stability and relatively rapid transition in the history of other social institutions---one need only think of the political and cultural history of our own country. It is very hard for the layman to accept the notion that in linguistic history we are not at all sure that the distinction can be made.

Hockett は,言語史における時代区分には参照の便よりほかに有用性はないと断じながら,参照の便ということならばむしろ Alfred, Ælfric, Chaucer, Caxton などの名を冠した時代名を設定するほうが記憶のためにもよいと述べている.従来の区分や用語をすぐに廃することは難しいが,私も原則として時代区分の意義はおよそ参照の便に存するにすぎないだろうと考えている.それでも誤解に陥りそうになったら,常に Hockett の図の右肩下がりの直線を思い出すようにしたい.

時代区分の問題については periodisation の各記事を,言語変化の速度については speed_of_change の各記事を参照されたい.とりわけ安定期と変化期の分布という問題については,「#1397. 断続平衡モデル」 ([2013-02-22-1]),「#1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード」 ([2014-02-09-1]),「#1755. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード (2)」 ([2014-02-15-1]) の議論を参照.

・ Hockett, Charles F. "The Terminology of Historical Linguistics." Studies in Linguistics 12.3--4 (1957): 57--73.

・ Curzan, Anne. Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History. Cambridge: CUP, 2014.

2016-07-06 Wed

■ #2627. アクセントの分類 [typology][prosody][stress][terminology]

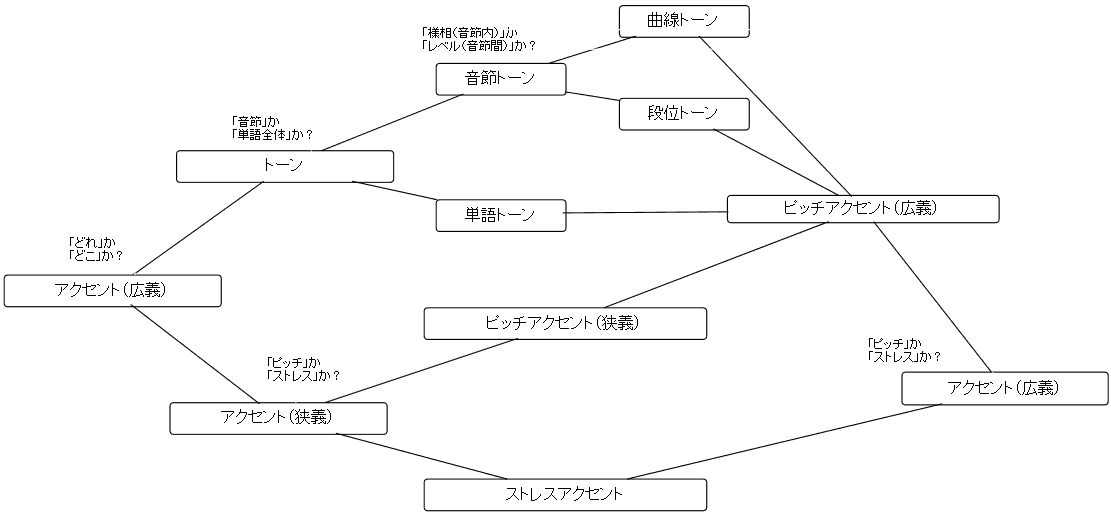

言語におけるアクセント(強勢)について,一般言語学的な立場から,「#926. 強勢の本来的機能」 ([2011-11-09-1]) や「#1647. 言語における韻律的特徴の種類と機能」 ([2013-10-30-1]) で概説した.関連して,斉藤 (109) がアクセントの類型論を与えているので,それを参照した以下の分類図を作成した.

図の左から右へと見ていくと,広義の「アクセント」は,有限のいくつかのパターンから「どれ」を選ぶかという「トーン」系列と,「どこ」を卓越させるかに関する狭義のいわゆる「アクセント」系列に2分される.「トーン」系列は,パターンの適用される単位が音節単位か単語単位かによって分けられ,さらに細分化することもできるが,全体としては広い意味で「ピッチアクセント」に属する.

一方,図の下方の「アクセント」系列は,高低を基準とする「ピッチアクセント」(狭義)と強弱を基準とする「ストレスアクセント」に分かれる.それぞれは大きな分類としては「ピッチアクセント」と「アクセント」に属する.

用語と分類に若干ややこしいところがあるが,これをアクセントの類型論の見取り図として押さえておきたい.

・ 斉藤 純男 『日本語音声学入門』改訂版 三省堂,2013年.

2016-06-12 Sun

■ #2603. 「母語」の問題,再び [sociolinguistics][terminology][linguistic_ideology]

「#1537. 「母語」にまつわる3つの問題」 ([2013-07-12-1]),「#1926. 日本人≠日本語母語話者」 ([2014-08-05-1]) で「母語」という用語のもつ問題点を論じた.

母語 (mother tongue) とネイティブ・スピーカー (native speaker) は1対1で分かちがたく結びつけられるという前提があり,近代言語学でも当然視されてきたが,実はこの前提は1つのイデオロギーにすぎない.クルマス (180--81) の議論に耳を傾けよう.

母語とネイティブ・スピーカーを結びつけることは,さまざまな形で批判されてきた.それはこうした概念が,現実に即していない,理想化された二つの考えに基づいているからである.①言語とは,不変であり,明確な境界をもつシステムであり,②人は一つの言語にのみネイティブ・スピーカーになることが可能であるというものである.

こうした思想は,書記法が人々に広く普及し,実用言語がラテン語,ギリシア語,ヘブライ語といった伝統的な書き言葉から,その土地固有の話し言葉に移行した,初期ルネサンスのヨーロッパにおいて顕著だ.このときこそ「言語」文脈において,母のイメージが初めて現われたときである.フランス革命後の数世紀,義務教育の普及は母語を学校教育における教科として,そして政治的案件へと変えた.かつて無意識のうちに獲得すると考えられていた母語を話す技能は,意図的で,意識的な学習となったのだ.生来の能力であるものを学ばなければならないという,明らかな矛盾をはらみながら,完全な母語能力は生来の話者にしか到達し得ないという排他意識が強化されたのは,国民国家の世紀である19世紀であった.

それは言語,帰属意識,領土,国民間を結ぶイデオロギーが,国語イデオロギーに統合されたためである.学校教育が普及するに伴い,ドイツの哲学者 J. G. ヘルダーが提唱した,言語は国民精神の宝庫であるという考えに多くの国が賛同した.ヘルダーは,子供が母語を学ぶのは,いわば自分の祖先の精神の仕組みを受け継ぐことであると論じている.ヘルダーの思想の流れに続くロマン的な思想は,国語と見立てることで母語を,生まれつきでないと精通できない,あるいはできにくいシステムであると神話化した.言語のナショナリズムは個別言語を,排他的なものとしてとらえる傾向を強めた.明治時代,このイデオロギーは日本でも定着した.多くのヨーロッパ諸国と同様,日本も国民の単一言語主義を理想的なものとして支持した.

近代の始まりにヨーロッパで国家の統合のために使われた,排他的な母語のイデオロギー構成概念が,こうしたものとは違った伝統をもつ,つまり多言語が普通である土地の言語学者によって批判的に脱構築されたのは不思議なことではない.だからインドの言語学者 D. P. パッタナヤックは,人は実際に話すことができなくても,ある言語に帰属意識を感じる事が可能な一方,他方でそれが家庭で使われている言語であるかに係わらず,一番よくできる言語を母語として選べると指摘した.

多言語社会の人間にとって,安らぎ,かつ自分をきちんと表現できる第一言語は必ずしも一つである必要はない.多言語社会では,言語獲得の多種多様なパターンが存在する.「母語は自然に身につく」というヘルダーの単一言語の安定性を重視するイデオロギーに対し,二つまたはそれ以上の言語システムが存在する社会では,母語能力とネイティブ・スピーカーを単純にむすぶイデオロギーも覆されることになる.

ここでクルマスが示唆しているのは,「母語」とは相対的な概念であり,用語であるということだ.話者によって,社会によって「母語」に込められた意味は異なっており,その込められた意味とは1つの言語イデオロギーにほかならない.母語とネイティブ・スピーカーは必ずしも1対1の関係ではないのだ.

私も,日常用語として,また言語についての学術的な言説において「母語」や「ネイティブ・スピーカー」という表現を多用しているが,その背後には,あまり語られることのない,しかしきわめて重大な前提が隠れている可能性に気づいておく必要がある.

・ クルマス,フロリアン 「母語」 『世界民族百科事典』 国立民族学博物館(編),丸善出版,2014年.180--81頁.

2016-06-11 Sat

■ #2602. Baugh and Cable の英語史からの設問 --- Chapters 9 to 11 [hel_education][terminology]

「#2588. Baugh and Cable の英語史からの設問 --- Chapters 1 to 4」 ([2016-05-28-1]),「#2594. Baugh and Cable の英語史からの設問 --- Chapters 5 to 8」 ([2016-06-03-1]) に続き,最終編として9--11章の設問を提示する.

[ Chapter 9: The Appeal to Authority, 1650--1800 ]

1. Explain why the following people are important in historical discussions of the English language:

John Dryden

Jonathan Swift

Samuel Johnson

Joseph Priestley

Robert Lowth

Lindley Murray

John Wilkins

James Harris

Thomas Sheridan

George Campbell

2. How were the intellectual tendencies of the eighteenth century reflected in attitudes toward the English language?

3. What did eighteenth-century writers mean by ascertainment of the English language? What means did they have in mind?

4. What kinds of "corruptions" in the English language did Swift object to? Do you find them objectionable? Can you think of similar objections made by commentators today?

5. What had been accomplished in Italy and France during the seventeenth century to serve as an inspiration for those in England who were concerned with the English language?

6. Who were among the supporters of an English Academy? When did the movement reach its culmination?

7. Why did an English Academy fail to materialize? What served as substitutes for an academy in England?

8. What did Johnson hope for his Dictionary to accomplish?

9. What were the aims of the eighteenth-century prescriptive grammarians?

10. How would you characterize the difference in attitude between Robert Lowth's Short Introduction to English Grammar (1762) and Joseph Priestley's Rudiments of English Grammar (1761)? Which was more influential?

11. How did prescriptive grammarians such as Lowth arrive at their rules?

12. What were some of the weaknesses of the early grammarians?

13. Which foreign language contributed the most words to English during the eighteenth century?

14. In tracing the growth of progressive verb forms since the eighteenth century, what earlier patterns are especially important?

15. Give an example of the progressive passive. From what period can we date its development?

[ Chapter 10: The Nineteenth Century and After ]

1. Explain why the following people are important in historical discussions of the English Language:

Sir James A. H. Murray

Henry Bradley

Sir William A. Craigie

C. T. Onions

2. Define the following terms and for each provide examples of words or meanings that have entered the English language since 1800:

Borrowing

Self-explaining compound

Compound formed from Greek or Latin elements

Prefix

Suffix

Coinage

Common word from proper name

Old word with new meaning

Extension of meaning

Narrowing of meaning

Degeneration of meaning

Regeneration of meaning

Slang

Verb-adverb combination

3. What distinction has been drawn between cultural levels and functional varieties of English? Do you find the distinction valid?

4. What are the principal regional dialects of English in the British Isles? What are some of the characteristics of these dialects?

5. What are the main national and areal varieties of English that have developed in countries that were once part of the British Empire?

6. Summarize the main efforts at spelling reform in England and the United States during the past century. Do you think that movement for spelling reform will succeed in the future?

7. How long did it take to produce the Oxford English Dictionary? By what name was it originally known?

8. What changes have occurred in English grammatical forms and conventions during the past two centuries?

[ Chapter 11: The English Language in America ]

1. Explain why the following people are important in historical discussions of the English language:

Noah Webster

Benjamin Franklin

James Russell Lowell

H. L. Mencken

Hans Kurath

Leonard Bloomfield

Noam Chomsky

William Labov

2. Define, identify, or explain briefly:

Old Northwest Territory

An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828)

The American Spelling Book

"Flat a"

African American Vernacular English

Pidgin

Creole

Gullah

Americanism

Linguistic Atlas of the United States and Canada

Phoneme

Allophone

Generative grammar

3. What three great periods of European immigration can be distinguished in the peopling of the United States?

4. What groups settled the Middle Atlantic States? How do the origins of these settlers contrast with the origins of the settlers in New England and the South Atlantic states?

5. What accounts for the high degree of uniformity of American English?

6. Is American English more or less conservative than British English? In trying to answer the question, what geographical divisions must one recognize in both the United States and Britain? Does the answer that applies to pronunciation apply also to vocabulary?

7. What considerations moved Noah Webster to advocate distinctly American form of English?

8. In what features of American pronunciation is it possible to find Webster's influence?

9. What are the most noticeable differences in pronunciation between British and American English?

10. What three main dialects in American English have been distinguished by dialectologists associated with the Linguistic Atlas of the United States and Canada? What three dialects had traditionally been distinguished?

11. According to Baugh and Cable, what eight American dialects are prominent enough to warrant individual characterization?

12. What is the Creole hypothesis regarding African American Vernacular English?

13. To what may one attribute certain similarities between the speech of New England and that of the South?

14. To what may one attribute the preservation of r in American English?

15. To what extent are attitudes which were expressed in the nineteenth-century "controversy over Americanisms" still alive today? How pervasive now is the "purist attitude"?

16. What are the main historical dictionaries of American English?

・ Cable, Thomas. A Companion to History of the English Language. 3rd ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2016-06-03 Fri

■ #2594. Baugh and Cable の英語史からの設問 --- Chapters 5 to 8 [hel_education][terminology]

「#2588. Baugh and Cable の英語史からの設問 --- Chapters 1 to 4」 ([2016-05-28-1]) に続いて,5--8章の設問を提示する.Baugh and Cable の復習のお供にどうぞ.

[ Chapter 5: The Norman Conquest and the Subjection of English, 1066--1200 ]

1. Explain why the following people are important in historical discussions of the English language:

Æthelred

Edward the Confessor

Godwin

Harold

William, duke of Normandy

Henry I

Henry II

2. How would the English language probably have been different if the Norman Conquest had never occurred?

3. From what settlers does Normandy derive its name? When did they come to France?

4. Why did William consider that he had claim on the English throne?

5. What was the decisive battle between the Normans and the English? How did the Normans win it?

6. When was William crowned king of England? How long did it take him to complete his conquest of England and gain complete recognition? In what parts of the country did he face rebellions?

7. What happened to Englishmen in positions of church and state under William's rule?

8. For how long after the Norman Conquest did French remain the principal language of the upper classes in England?

9. How did William divide his lands at his death?

10. What was the extent of the lands ruled by Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine?

11. What was generally the attitude of the French kings and upper classes to the English language?

12. What does the literature written under the patronage of the English court indicate about French culture and language in England during this period?

13. How complete was the fusion or the French and English peoples in England?

14. In general, which parts of the population spoke English, and which French?

15. To what extent did the upper classes learn English? What can one infer concerning Henry II's knowledge of English?

16. How far down in the social scale was knowledge of French at all general?

[ Chapter 6: The Reestablishment of English, 1200--1500 ]

1. Explain why the following are important in historical discussions of the English language:

King John

Philip, king of France

Henry III

The Hundred Years' War

The Black Death

The Peasants' Revolt

Statute of Pleading

Layamon

Geoffrey Chaucer

John Wycliffe

2. In what year did England lose Normandy? What events brought about the loss?

3. What effect did the loss of Normandy have upon the nobility of France and England and consequently upon the English language?

4. Despite the loss of Normandy, what circumstances encouraged the French to continue coming to England during the long reign of Henry III (1216--1272)?

5. The arrival of foreigners during Henry III's reign undoubtedly delayed the spread of English among the upper classes. In what ways did these events actually benefit the English language?

6. What was the status of French throughout Europe in the thirteenth century?

7. What explains the fact that the borrowing of French words begins to assume large proportions during the second half of the thirteenth century, as the importance of the French language in England is declining?

8. What general conclusions can one draw about the position of English at the end of the thirteenth century?

9. What can one conclude about the use of French in the church and the universities by the fourteenth century?

10. What kind of French was spoken in England, and how was it regarded?

11. In what way did the Hundred Years' War probably contribute to the decline of French in England?

12. According to Baugh and Cable, the Black Death reduced the numbers of the lower classes disproportionately and yet indirectly increased the importance of the language that they spoke. Why was this so?

13. What specifically can one say about changing conditions for the middle class in England during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries? What effect did these changes have upon the English language?

14. In what year was Parliament first opened with a speech in English?

15. What statute marks the official recognition of the English language in England?

16. When did English begin to be used in the schools?

17. What was the status of the French language in England by the end of the fifteenth century?

18. About when did English become generally adopted for the records of towns and the central government?

19. What does English literature between 1150 and 1350 tell us about the changing fortunes of the English language?

20. What do the literary accomplishments of the period between 1350 and 1400 imply about the status of English?

[ Chapter 7: Middle English ]

1. Define:

Leveling

Analogy

Anglo-Norman

Central French

Hybrid forms

Latin influence of the Third Period

Aureate diction

Standard English

2. What phonetic changes brought about the leveling of inflectional endings in Middle English?

3. What accounts for the -e in Modern English stone, the Old English form of which was stān in the nominative and accusative singular?

4. Generally what happened to inflectional endings of nouns in Middle English?

5. What two methods of indicating the plural of nouns remained common in early Middle English?

6. Which form of the adjective became the form for all cases by the close of the Middle English period?

7. What happened to the demonstratives sē, sēo, þæt and þēs, þēos, þis in Middle English?

8. Why were the losses not so great in the personal pronouns? What distinction did the personal pronouns lose?

9. What is the origin of the th- forms of the personal pronoun in the third person plural?

10. What were the principal changes in the verb during the Middle English period?

11. Name five strong verbs that were becoming weak during the thirteenth century.

12. Name five strong post participles that have remained in use after the verb became weak.

13. How many of the Old English strong verbs remain in the language today?

14. What effect did the decay of inflections have upon grammatical gender in Middle English?

15. To what extent did the Norman Conquest affect the grammar of English?

16. In the borrowing of French words into English, how is the period before 1250 distinguished from the period after?

17. Into what general classes do borrowings of French vocabulary fall?

18. What accounts for the difference in pronunciation between words introduced into English after the Norman Conquest and the corresponding words in Modem French?

19. Why are the French words borrowed during the fifteenth century of a bookish quality?

20. What is the period of the greatest borrowing of French words? Altogether about how many French words were adopted during the Middle English period?

21. What principle is illustrated by the pairs ox/beef, sheep/mutton, swine/pork, and calf/veal?

22. What generally happened to the Old English prefixes and suffixes in Middle English?

23. Despite the changes in the English language brought about by the Norman Conquest, in what ways was the language still English?

24. What was the main source of Latin borrowings during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries?

25. In which Middle English writers is aureate diction most evident?

26. What tendency may be observed in the following sets of synonyms: rise--mount--ascend, ask--question--interrogate, goodness--virtue--probity?

27. What kind of contact did the English have with speakers of Flemish, Dutch, and Low German during the late Middle Ages?

28. What are the five principal dialects of Middle English?

29. Which dialect of Middle English became the basis for Standard English? What causes contributed to the establishment of this dialect?

30. Why did the speech of London have special importance during the late Middle Ages?

[ Chapter 8: The Renaissance, 1500--1650 ]

1. Explain why the following people are important in historical discussions of the English language:

Richard Mulcaster

John Hart

William Bullokar

Sir John Cheke

Thomas Wilson

Sir Thomas Elyot

Sir Thomas More

Edmund Spenser

Robert Cawdrey

Nathaniel Bailey

2. Define:

Inkhorn terms

Oversea language

Chaucerisms

Latin influence of the Fourth Period

Great Vowel Shift

His-genitive

Group possessive

Orthography

3. What new forces began to affect the English language in the Modern English period? Why may it be said that these forces were both radical and conservative?

4. What problems did the modern European languages face in the sixteenth century?

5. Why did English have to be defended as language of scholarship? How did the scholarly recognition of English come about?

6. Who were among the defenders of borrowing foreign words?

7. What was the general attitude toward inkhorn terms by the end of Elizabeth's reign?

8. What were some of the ways in which Latin words changed their form as they entered the English language?

9. Why were some words in Renaissance English rejected while others survived?

10. What classes of strange words did sixteenth-century purists object to?

11. When was the first English dictionary published? What was the main purpose of English dictionaries throughout the seventeenth century?

12. From the discussions in Baugh and Cable 則177 and below, summarize the principal features in which Shakespeare's pronunciation differs from your own.

13. Why is vowel length important in discussing sound changes in the history of the English language?

14. Why is the Great Vowel Shift responsible for the anomalous use of the vowel symbols in English spelling?

15. How does the spelling of unstressed syllables in English fail to represent accurately the pronunciation?

16. What nouns with the old weak plural in -n can be found in Shakespeare?

17. Why do Modern English nouns have an apostrophe in the possessive?

18. When did the group possessive become common in England?

19. How did Shakespeare's usage in adjectives differ from current usage?

20. What distinctions, at different periods, were made by the forms thou, thy, thee? When did the forms fall out of general use?

21. How consistently were the nominative ye and the objective you distinguished during the Renaissance?

22. What is the origin of the form its?

23. When did who begin to be used as relative pronoun? What are the sources of the form?

24. What forms for the the third person singular of the verb does one find in Shakespeare? What happened to these forms during the seventeenth century?

25. How would cultivated speakers of Elizabethan times have regarded Shakespeare's use of the double negative in "Thou hast spoken no word all this time---nor understood none neither"?

・ Cable, Thomas. A Companion to History of the English Language. 3rd ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2016-05-28 Sat

■ #2588. Baugh and Cable の英語史からの設問 --- Chapters 1 to 4 [hel_education][terminology]

今期,大学の演習で,英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable の A History of the English Language の第6版を読んでいる.この英語史概説書について,本ブログでは「#2089. Baugh and Cable の英語史概説書の目次」 ([2015-01-15-1]),「#2182. Baugh and Cable の英語史第6版」 ([2015-04-18-1]),「#2488. 専門科目かつ教養科目としての英語史」 ([2016-02-18-1]) でレビューしてきたし,その他の多くの記事でも参照・引用してきた.

この英語史書には,演習問題集がコンパニオンとして出版されている.5版に対するコンパニオンなので,細かく見ると6版と対応しない部分もあるが,各章の内容が理解できているかどうかの確認としては十分に利用できる.今回は,1章から4章の設問を集めてみた.一覧すると,一種の英語史用語集としても使える.

[ Chapter 1: English Present and Future ]

1. Define the following terms, which appear in Chapter 1 of Baugh and Cable, History of the English Language (5th ed.):

Analogy

Borrowing

Inflection

Natural gender

Grammatical gender

Idiom

Lingua franca

2. Upon what does the importance of language depend?

3. About how many people speak English as native language?

4. Which language of the world has the largest number of speakers?

5. What are the six largest European languages after English?

6. Why is English so widely used as second language?

7. Which languages are likely to grow most rapidly in the foreseeable future? Why?

8. What are the official languages of the United Nations?

9. For speaker of another language learning English, what are three assets of the language?

10. What difficulties does the non-native speaker of English encounter?

[ Chapter 2: The Indo-European Family of Languages ]

1. Explain why the following people are important in studies of the Indo-European family of languages:

Panini

Ulfilas

Jacob Grimm

Karl Verner

Ferdinand de Saussure

2. Define, identify, or explain briefly:

Family of languages

Indo-European

Rig-veda

Koiné

Langue d'oïl, langue d'oc

Vulgar Latin

Proto-Germanic

Second Sound Shift

West Germanic

Hittites

Laryngeals

Object-Verb structure

Centum and satem languages

Kurgans

3. What is Sanskrit? Why is it important in the reconstruction of Indo-European?

4. When did the sound change described by Grimm's Law occur? In what year did Grimm formulate the law?

5. Name the eleven principal groups in the Indo-European family.

6. Approximately what date can be assigned to the oldest texts of Vedic Sanskrit?

7. From what non-Indo-European language has modern Persian borrowed much vocabulary?

8. Which of the dialects of ancient Greece was the most important? In what centuries did its literature flourish?

9. Why are the Romance languages so called? Name the modern Romance languages.

10. What were the important dialects of French in the Middle Ages? Which became the basis for standard French?

11. For the student of Indo-European, what is especially interesting about Lithuanian?

12. Name the Slavic languages. With what other group does Slavic form branch of the Indo-European tree?

13. Into what three groups is the Germanic branch divided? For which of the Germanic languages do we have the earliest texts?

14. From what period do our texts of Scandinavian languages date?

15. Why is Old English classified as Low German language?

16. Name the two branches of the Celtic family and the modern representative of each.

17. Where are the Celtic languages now spoken? What is happening to these languages?

18. What two languages of importance to Indo-European studies were discovered in this century?

19. Why have the words for beech and bee in the various Indo-European languages been important in establishing the location of the Indo-European homeland?

20. What light have recent archaeological discoveries thrown on the Indo-European homeland?

[ Chapter 3: Old English ]

1. Explain why the following are important in historical discussions of the English language:

Claudius

Vortigern

The Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy

Beowulf

Alfred the Great

Ecclesiastical History of the English People

2. Define the following terms:

Synthetic language

Analytic language

Vowel declension

Consonant declension

Grammatical gender

Dual number

Paleolithic Age

Neolithic Age

3. Who were the first people in England about whose language we have definite knowledge?

4. When did the Romans conquer England, and when did they withdraw?

5. At approximately what date did the invasion of England by the Germanic tribes begin?

6. Where were the homes of the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes?

7. Where does the name English come from?

8. What characteristics does English share with other Germanic languages?

9. To which branch of Germanic docs English belong?

10. What are the dates of Old English, Middle English, and Modern English?

11. What are the four dialects of Old English?

12. About what percentage of the Old English vocabulary is no longer in use?

13. Explain the difference between strong and weak declensions of adjectives.

14. How does the Old English definite article differ from the definite article of Modern English?

15. Explain the difference between weak and strong verbs.

16. How many classes of strong verbs were there in Old English?

17. In what ways was the Old English vocabulary expanded?

[ Chapter 4: Foreign Influences on Old English ]

1. Explain why the following people and events are important in historical discussions of the English language:

St Augustine

Bede

Alcuin

Dunstan

Ælfric

Cnut

Treaty of Wedmore

Battle of Maldon

2. Define the following terms:

i-Umlaut

Palatal diphthongization

The Danelaw

3. How extensive was the Celtic influence on Old English?

4. What accounts for the difference between the influence of Celtic and that of Latin upon the English language?

5. During what three periods did Old English borrow from Latin?

6. What event, according to Bede, inspired the mission of St Augustine? In what year did die mission begin?

7. What were the three periods of Viking attacks on England?

8. What are some of the characteristic endings of place-names borrowed from Danish?

9. About how many Scandinavian place-names have been counted in England?

10. Approximately how many Scandinavian words appeared in Old English?

11. From what language has English acquired the pronouns they, their, them, and the present plural are of the verb to be? What were the equivalent Old English words?

12. What inflectional elements have been attributed to Scandinavian influence?

13. What influence did Christianity have on Old English?

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

・ Cable, Thomas. A Companion to History of the English Language. 3rd ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2016-05-09 Mon

■ #2569. dead metaphor (2) [metaphor][conceptual_metaphor][rhetoric][cognitive_linguistics][terminology]

昨日の記事 ([2016-05-08-1]) に引き続き,dead metaphor について.dead metaphor とは,かつては metaphor だったものが,やがて使い古されて比喩力・暗示力を失ってしまった表現を指すものであると説明した.しかし,メタファーと認知の密接な関係を論じた Lakoff and Johnson (55) は,dead metaphor をもう少し広い枠組みのなかでとらえている.the foot of the mountain の例を引きながら,なぜこの表現が "dead" metaphor なのかを丁寧に説明している.

Examples like the foot of the mountain are idiosyncratic, unsystematic, and isolated. They do not interact with other metaphors, play no particularly interesting role in our conceptual system, and hence are not metaphors that we live by. . . . If any metaphorical expressions deserve to be called "dead," it is these, though they do have a bare spark of life, in that they are understood partly in terms of marginal metaphorical concepts like A MOUNTAIN IS A PERSON.

It is important to distinguish these isolated and unsystematic cases from the systematic metaphorical expressions we have been discussing. Expressions like wasting time, attacking positions, going our separate ways, etc., are reflections of systematic metaphorical concepts that structure our actions and thoughts. They are "alive" in the most fundamental sense: they are metaphors we live by. The fact that they are conventionally fixed within the lexicon of English makes them no less alive.

「死んでいる」のは,the foot of the mountain という句のメタファーや,そのなかの foot という語義におけるメタファーにとどまらない.むしろ,表現の背後にある "A MOUNTAIN IS A PERSON" という概念メタファー (conceptual metaphor) そのものが「死んでいる」のであり,だからこそ,これを拡張して *the shoulder of the mountain や *the head of the mountain などとは一般的に言えないのだ.Metaphors We Live By という題の本を著わし,比喩が生きているか死んでいるか,話者の認識において活性化されているか否かを追究した Lakoff and Johnson にとって,the foot of the mountain が「死んでいる」というのは,共時的にこの表現のなかに比喩性が感じられないという局所的な事実を指しているのではなく,話者の認知や行動の基盤として "A MOUNTAIN IS A PERSON" という概念メタファーがほとんど機能していないことを指しているのである.引用の最後で述べられている通り,表現が慣習的に固定化しているかどうか,つまり常套句であるかどうかは,必ずしもそれが「死んでいる」ことを意味しないという点を理解しておくことは重要である.

・ Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1980.

2016-05-08 Sun

■ #2568. dead metaphor (1) [metaphor][rhetoric][cognitive_linguistics][terminology][semantics][semantic_change][etymology]

metaphor として始まったが,後に使い古されて常套語句となり,もはや metaphor として感じられなくなったような表現は,"dead metaphor" (死んだメタファー)と呼ばれる.「机の脚」や「台風の目」というときの「脚」や「目」は,本来の人間(あるいは動物)の体の部位を指すものからの転用であるという感覚は希薄である.共時的には,本来的な語義からほぼ独立した別の語義として理解されていると思われる.英語の the legs of a table や the foot of the mountain も同様だ.かつては生き生きとした metaphor として機能していたものが,時とともに衰退 (fading) あるいは脱メタファー化 (demetaphorization) を経て,化石化したものといえる(前田,p. 127).

しかし,上のメタファーの例は完全に「死んでいる」わけではない.後付けかもしれないが,机の脚と人間の脚とはイメージとして容易につなげることはできるからだ.もっと「死んでいる」例として,pupil の派生語義がある.この語の元来の語義は「生徒,学童」だが,相手の瞳に映る自分の像が小さい子供のように見えるところから転じて「瞳」の語義を得た.しかし,この意味的なつながりは現在では語源学者でない限り,意識にはのぼらず,共時的には別の単語として理解されている.件の比喩は,すでにほぼ「死んでいる」といってよい.

「死んでいる」程度の差はあれ,この種の dead metaphor は言語に満ちている.「#2187. あらゆる語の意味がメタファーである」 ([2015-04-23-1]) で列挙したように,語という単位で考えても,その語源をひもとけば,非常に多数の語の意味が dead metaphor として存在していることがわかる.advert, comprehend など,そこであげた多くのラテン語由来の語は,英語への借用がなされた時点で,すでに共時的に dead metaphor であり,「死んだメタファーの輸入品」(前田,p. 127)と呼ぶべきものである.

・ 前田 満 「意味変化」『意味論』(中野弘三(編)) 朝倉書店,2012年,106--33頁.

・ 谷口 一美 『学びのエクササイズ 認知言語学』 ひつじ書房,2006年.

2016-05-04 Wed

■ #2564. variety と lect [variety][terminology][style][register][dialect][sociolinguistics][lexical_diffusion][speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change]

社会言語学では variety (変種)という用語をよく用いるが,ときに似たような使い方で lect という用語も聞かれる.これは dialect や sociolect の lect を取り出したものだが,用語上の使い分けがあるのか疑問に思い,Trudgill の用語集を繰ってみた.それぞれの項目を引用する.

variety A neutral term used to refer to any kind of language --- a dialect, accent, sociolect, style or register --- that a linguist happens to want to discuss as a separate entity for some particular purpose. Such a variety can be very general, such as 'American English', or very specific, such as 'the lower working-class dialect of the Lower East Side of New York City'. See also lect

lect Another term for variety or 'kind of language' which is neutral with respect to whether the variety is a sociolect or a (geographical) dialect. The term was coined by the American linguist Charles-James Bailey who, as part of his work in variation theory, has been particularly interested in the arrangement of lects in implicational tables, and the diffusion of linguistic changes from one linguistic environment to another and one lect to another. He has also been particularly concerned to define lects in terms of their linguistic characteristics rather than their geographical or social origins.

案の定,両語とも "a kind of language" ほどでほぼ同義のようだが,variety のほうが一般的に用いられるとはいってよいだろう.ただし,lect は言語変化においてある言語項が lect A から lect B へと分布を広げていく過程などを論じる際に使われることが多いようだ.つまり,lect は語彙拡散 (lexical_diffusion) の理論と相性がよいということになる.

なお,上の lect の項で参照されている Charles-James Bailey は,「#1906. 言語変化のスケジュールは言語学的環境ごとに異なるか」 ([2014-07-16-1]) で引用したように,確かに語彙拡散や言語変化のスケジュール (schedule_of_language_change) の問題について理論的に扱っている社会言語学者である.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2016-05-03 Tue

■ #2563. 通時言語学,共時言語学という用語を巡って [saussure][terminology][diachrony][methodology][history_of_linguistics][evolution]

「#2555. ソシュールによる言語の共時態と通時態」 ([2016-04-25-1]) で,共時態と通時態の区別について話題にした.ところで,Saussure (116--17) は Cours で,通時態と共時態の峻別を説いた段落の直後に,標題の2つの言語学の呼称について次のように論じている.

Voilà pourquoi nous distinguons deux linguistiques. Comment les désignerons-nous? Les termes qui s'offrent ne sont pas tous également propres à marquer cette distinction. Ainsi histoire et «linguistique historique» ne sont pas utilisables, car ils appellent des idées trop vagues; comme l'histoire politique comprend la description des époques aussi bien que la narration des événements, on pourrait s'imaginer qu'en décrivant des états de la langue succesifs on étudie la langue selon l'axe du temps; pour cela, il faudrait envisager séparément les phénomènes qui font passer la langue d'un état à un autre. Les termes d'évolution et de linguistique évolutive sont plus précis, et nous les emploierons souvent; par opposition on peut parler de la science des états de langue ou linguistique statique.

Mais pour mieux marquer cette opposition et ce croisement de deux ordres de phénomènes relatifs au même objet, nous préfèrons parler de linguistique synchronique et de linguistique diachronique. Est synchronique tout ce qui se rapporte à l'aspect statique de notre science, diachronique tout ce qui a trait aux évolutions. De même synchronie et diachronie désigneront respectivement un état de langue et une phase d'évolution.

ここで Saussure は用語へのこだわりを見せている.Saussure が「歴史」言語学 (linguistique historique) では曖昧だというのは,時間軸上の異なる点における状態を次々と記述することも「歴史」であれば,ある共時的体系から別の共時的体系へと時間軸に沿って進ませている現象について語ることも「歴史」であるからだ.後者の意味を表わすためには「歴史」だけでは不正確であるということだろう.そこで後者に特化した用語として "linguistic historique" の代わりに "linguistique évolutive" (対して "linguistic statique")を用いることを選んだ.さらに,2つの軸の対立を用語上で目立たせるために,"linguistique diachronique" (対して "linguistic synchronique") を採用したのである.

このような経緯で通時態と共時態の用語上の対立が確立してきたわけが,進化言語学 ("linguistique évolutive") と静態言語学 ("linguistic statique") という呼称も,個人的にはすこぶる直感的で捨てがたい気がする.

・ Saussure, Ferdinand de. Cours de linguistique générale. Ed. Tullio de Mauro. Paris: Payot & Rivages, 2005.

2016-04-30 Sat

■ #2560. 古英語の形容詞強変化屈折は名詞と代名詞の混合パラダイム [adjective][ilame][terminology][morphology][inflection][oe][germanic][paradigm][personal_pronoun][noun]

古英語の形容詞の強変化・弱変化の区別については,ゲルマン語派の顕著な特徴として「#182. ゲルマン語派の特徴」 ([2009-10-26-1]),「#785. ゲルマン度を測るための10項目」 ([2011-06-21-1]),「#687. ゲルマン語派の形容詞の強変化と弱変化」 ([2011-03-15-1]) で取り上げ,中英語における屈折の衰退については ilame の各記事で話題にした.

強変化と弱変化の区別は古英語では名詞にもみられた.弱変化形容詞の強・弱屈折は名詞のそれと形態的におよそ平行しているといってよいが,若干の差異がある.ことに形容詞の強変化屈折では,対応する名詞の強変化屈折と異なる語尾が何カ所かに見られる.歴史的には,その違いのある箇所には名詞ではなく人称代名詞 (personal_pronoun) の屈折語尾が入り込んでいる.つまり,古英語の形容詞強変化屈折は,名詞屈折と代名詞屈折が混合したようなものとなっている.この経緯について,Hogg and Fulk (146) の説明に耳を傾けよう.

As in other Gmc languages, adjectives in OE have a double declension which is syntactically determined. When an adjective occurs attributively within a noun phrase which is made definite by the presence of a demonstrative, possessive pronoun or possessive noun, then it follows one set of declensional patterns, but when an adjective is in any other noun phrase or occurs predicatively, it follows a different set of patterns . . . . The set of patterns assumed by an adjective in a definite context broadly follows the set of inflexions for the n-stem nouns, whilst the set of patterns taken in other indefinite contexts broadly follows the set of inflexions for a- and ō-stem nouns. For this reason, when adjectives take the first set of inflexions they are traditionally called weak adjectives, and when they take the second set of inflexions they are traditionally called strong adjectives. Such practice, although practically universal, has less to recommend it than may seem to be the case, both historically and synchronically. Historically, . . . some adjectival inflexions derive from pronominal rather than nominal forms; synchronically, the adjectives underwent restructuring at an even swifter pace than the nouns, so that the terminology 'strong' or 'vocalic' versus 'weak' or 'consonantal' becomes misleading. For this reason the two declensions of the adjective are here called 'indefinite' and 'definite' . . . .

具体的に強変化屈折のどこが起源的に名詞的ではなく代名詞的かというと,acc.sg.masc (-ne), dat.sg.masc.neut. (-um), gen.dat.sg.fem (-re), nom.acc.pl.masc. (-e), gen.pl. for all genders (-ra) である (Hogg and Fulk 150) .

強変化・弱変化という形態に基づく,ゲルマン語比較言語学の伝統的な区分と用語は,古英語の形容詞については何とか有効だが,中英語以降にはほとんど無意味となっていくのであり,通時的にはより一貫した統語・意味・語用的な機能に着目した不定 (definiteness) と定 (definiteness) という区別のほうが妥当かもしれない.

・ Hogg, Richard M. and R. D. Fulk. A Grammar of Old English. Vol. 2. Morphology. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2016-04-25 Mon

■ #2555. ソシュールによる言語の共時態と通時態 [saussure][diachrony][methodology][terminology][linguistics]

ソシュール以来,言語を考察する視点として異なる2つの角度が区別されてきた.共時態 (synchrony) と通時態 (diachrony) である.本ブログではこの2分法を前提とした上で,それに依拠したり,あるいは懐疑的に議論したりしてきた.この有名な2分法について,言語学用語辞典などを参照して,あらためて確認しておこう.

まず,丸山のソシュール用語解説 (309--10) には次のようにある.

synchronie/diachronie [共時態/通時態]

ある科学の対象が価値体系 (système de valeurs) として捉えられるとき,時間の軸上の一定の面における状態 (état) を共時態と呼び,その静態的事実を,時間 (temps) の作用を一応無視して記述する研究を共時言語学 (linguistique synchronique) という.これはあくまでも方法論上の視点であって,現実には,体系は刻々と移り変わるばかりか,複数の体系が重なり合って共存していることを忘れてはならない.〔中略〕これに対して,時代の移り変わるさまざまな段階で記述された共時的断面と断面を比較し,体系総体の変化を辿ろうとする研究が,通時言語学 (linguistique diachronique) であり,そこで対象とされる価値の変動 (déplacement) が通時態である.

同じく丸山 (73--74) では,ソシュールの考えを次のように解説している.

「言語学には二つの異なった科学がある.静態または共時言語学と,動態または通時言語学がそれである」.この二つの区別は,およそ価値体系を対象とする学問であれば必ずなされるべきであって,たとえば経済学と経済史が同一科学のなかでもはっきりと分かれた二分野を構成するのと同時に,言語学においても二つの領域を峻別すべきであるというのが彼〔ソシュール〕の考えであった.ソシュールはある一定時期の言語の記述を共時言語学 (linguistique synchronique),時代とともに変化する言語の記述を通時言語学 (linguistique diachronique) と呼んでいる.

Crystal の用語辞典では,pp. 469, 142 にそれぞれ見出しが立てられている.

synchronic (adj.) One of the two main temporal dimensions of LINGUISTIC investigation introduced by Ferdinand de Saussure, the other being DIACHRONIC. In synchronic linguistics, languages are studied at a theoretical point in time: one describes a 'state' of the language, disregarding whatever changes might be taking place. For example, one could carry out a synchronic description of the language of Chaucer, or of the sixteenth century, or of modern-day English. Most synchronic descriptions are of contemporary language states, but their importance as a preliminary to diachronic study has been stressed since Saussure. Linguistic investigations, unless specified to the contrary, are assumed to be synchronic; they display synchronicity.

diachronic (adj.) One of the two main temporal dimensions of LINGUISTIC investigation introduced by Ferdinand de Saussure, the other being SYNCHRONIC. In diachronic linguistics (sometimes called linguistic diachrony), LANGUAGES are studied from the point of view of their historical development --- for example, the changes which have taken place between Old and Modern English could be described in phonological, grammatical and semantic terms ('diachronic PHONOLOGY/SYNTAX/SEMANTICS'). An alternative term is HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS. The earlier study of language in historical terms, known as COMPARATIVE PHILOLOGY, does not differ from diachronic linguistics in subject-matter, but in aims and method. More attention is paid in the latter to the use of synchronic description as a preliminary to historical study, and to the implications of historical work for linguistic theory in general.

・ 丸山 圭三郎 『ソシュール小事典』 大修館,1985年.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2016-04-24 Sun

■ #2554. 固有屈折と文脈屈折 [terminology][inflection][morphology][syntax][derivation][compound][word_formation][category][ilame]

屈折 (inflection) には,より語彙的な含蓄をもつ固有屈折 (inherent inflection) と,より統語的な含蓄をもつ文脈屈折 (contextual inflection) の2種類があるという議論がある.Booij (1) によると,

Inherent inflection is the kind of inflection that is not required by the syntactic context, although it may have syntactic relevance. Examples are the category number for nouns, comparative and superlative degree of the adjective, and tense and aspect for verbs. Other examples of inherent verbal inflection are infinitives and participles. Contextual inflection, on the other hand, is that kind of inflection that is dictated by syntax, such as person and number markers on verbs that agree with subjects and/or objects, agreement markers for adjectives, and structural case markers on nouns.

このような屈折の2タイプの区別は,これまでの研究でも指摘されることはあった.ラテン語の単数形 urbs と複数形 urbes の違いは,統語上の数の一致にも関与することはするが,主として意味上の数において異なる違いであり,固有屈折が関係している.一方,主格形 urbs と対格形 urbem の違いは,意味的な違いも関与しているが,主として統語的に要求される差異であるという点で,統語の関与が一層強いと判断される.したがって,ここでは文脈屈折が関係しているといえるだろう.

英語について考えても,名詞の数などに関わる固有屈折は,意味的・語彙的な側面をもっている.対応する複数形のない名詞,対応する単数形のない名詞(pluralia tantum),単数形と複数形で中核的な意味が異なる(すなわち異なる2語である)例をみれば,このことは首肯できるだろう.動詞の不定形と分詞の間にも類似の関係がみられる.これらは,基体と派生語・複合語の関係に近いだろう.

一方,文脈屈折がより深く統語に関わっていることは,その標識が固有屈折の標識よりも外側に付加されることと関与しているようだ.Booij (12) 曰く,"[C]ontextual inflection tends to be peripheral with respect to inherent inflection. For instance, case is usually external to number, and person and number affixes on verbs are external to tense and aspect morphemes".

言語習得の観点からも,固有屈折と文脈屈折の区別,特に前者が後者を優越するという説は支持されるようだ.固有屈折は独自の意味をもつために直接に文の生成に貢献するが,文脈屈折は独立した情報をもたず,あくまで統語的に間接的な意義をもつにすぎないからだろう.

では,言語変化の事例において,上で提起されたような固有屈折と文脈屈折の区別,さらにいえば前者の後者に対する優越は,どのように表現され得るのだろうか.英語史でもみられるように,種々の文法的機能をもった名詞,形容詞,動詞などの屈折語尾が消失していったときに,いずれの機能から,いずれの屈折語尾の部分から順に消失していったか,その順序が明らかになれば,それと上記2つの屈折タイプとの連動性や相関関係を調べることができるだろう.もしかすると,中英語期に生じた形容詞屈折の事例が,この理論的な問題に,何らかの洞察をもたらしてくれるのではないかと感じている.中英語期の形容詞屈折の問題については,ilame の各記事を参照されたい.

・ Booij, Geert. "Inherent versus Contextual Inflection and the Split Morphology Hypothesis." Yearbook of Morphology 1995. Ed. Geert Booij and Jaap van Marle. Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1996. 1--16.

2016-04-23 Sat

■ #2553. 構造的メタファーと方向的メタファーの違い (2) [conceptual_metaphor][metaphor][metonymy][synaesthesia][cognitive_linguistics][terminology]

昨日の記事 ([2016-04-22-1]) の続き.構造的メタファーはあるドメインの構造を類似的に別のドメインに移すものと理解してよいが,方向的メタファーは単純に類似性 (similarity) に基づいたドメインからドメインへの移転として捉えてよいだろうか.例えば,

・ MORE IS UP

・ HEALTH IS UP

・ CONTROL or POWER IS UP

という一連の方向的メタファーは,互いに「上(下)」に関する類似性に基づいて成り立っているというよりは,「多いこと」「健康であること」「支配・権力をもっていること」が物理的・身体的な「上」と共起することにより成り立っていると考えることもできないだろうか.共起性とは隣接性 (contiguity) とも言い換えられるから,結局のところ方向的メタファーは「メタファー」 (metaphor) といいながらも,実は「メトニミー」 (metonymy) なのではないかという疑問がわく.この2つの修辞法は,「#2496. metaphor と metonymy」 ([2016-02-26-1]) や 「#2406. metonymy」 ([2015-11-28-1]) で解説した通り,しばしば対置されてきたが,「#2196. マグリットの絵画における metaphor と metonymy の同居」 ([2015-05-02-1]) でも見たように,対立ではなく融和することがある.この観点から概念「メタファー」 (conceptual_metaphor) を,谷口 (79) を参照して改めて定義づけると,以下のようになる.

・ 概念メタファーは,2つの異なる概念 A, B の間を,「類似性」または「共起性」によって "A is B" と結びつけ,

・ 具体的な概念で抽象的な概念を特徴づけ理解するはたらきをもつ

概念メタファーとは,共起性や隣接性に基づくメトニミーをも含み込んでいるものとも解釈できるのだ.概念「メタファー」の議論として始まったにもかかわらず「メトニミー」が関与してくるあたり,両者の関係は一般に言われるほど相対するものではなく,相補うものととらえたほうがよいのかもしれない.

なお,このように2つの概念を類似性や共起性によって結びつけることをメタファー写像 (metaphorical mapping) と呼ぶ.共感覚表現 (synaesthesia) などは,共起性を利用したメタファー写像の適用である.

・ 谷口 一美 『学びのエクササイズ 認知言語学』 ひつじ書房,2006年.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow