2024-12-23 Mon

■ #5719. ギリシア語が英語に影響を与えた3つの型 [greek][latin][borrowing][loan_word][lexicology][word_formation][derivation][compounding][oe][prestige][combining_form][morphology][scientific_name][scientific_english][link]

ギリシア語が英語に与えた語彙的影響は,ラテン語やフランス語のそれに比べると見劣りするように思われるかもしれないが,実際にはきわめて大きい.語彙そのものというより,むしろ語形成 (word_formation) に与えた影響が大きい,といったほうが適切かもしれない.とりわけ連結形 (combining_form) を用いた科学系の複合語の形成は,ギリシア語の偉大な貢献である.

Durkin (231) は,英語史におけるギリシア語の影響について,広い視野から次のように述べている.

Between C5 and C8-9, the Greek liberal arts education was revived, first by the Ostrogoths, later by the Carolingians, and Greek gained special prestige. Writers liberally sprinkled their woks with Greek words, many of which found their way into other languages of Europe, including Old English. Particularly noteworthy are the glossarial poems from Canterbury with words like apoplexis, liturgia, spasmus. Since then, Greek medical doctrine and the terms associated with it became the major part of English medical lexis . . . . More general scientific vocabulary from Greek has mushroomed since C18 . . . .

. . . .

Greek influence on English, then, is restricted to the lexicon, (limited) derivation, and compounding. Words entered English initially through Roman borrowings, then through direct borrowing from Ancient Greek writers, more recently through word formation (combining roots and affixes) in English.

ギリシア語の英語への影響には,3パターンあるいは3段階があったとまとめてよいだろう.

(1) ラテン語を経由して(中世から)

(2) 直接ギリシア語から(近代以降)

(3) ギリシア語「要素」を用いた英語内での造語(近代以降,特に18世紀以降;「科学用語新古典主義的複合語」 (neo-classical compounds) あるいは「英製希語」と呼んでもよいか)

いずれのパターンについても,ギリシア語に付された威信 (prestige) を反映して学術用語の造語が圧倒的である.関連する話題として,以下の hellog 記事も参照.

・ 「#516. 直接のギリシア語借用は15世紀から」 ([2010-09-25-1])

・ 「#552. combining form」 ([2010-10-31-1])

・ 「#616. 近代英語期の科学語彙の爆発」 ([2011-01-03-1])

・ 「#617. 近代英語期以前の専門5分野の語彙の通時分布」 ([2011-01-04-1])

・ 「#1694. 科学語彙においてギリシア語要素が繁栄した理由」 ([2013-12-16-1])

・ 「#3014. 英語史におけるギリシア語の真の存在感は19世紀から」 ([2017-07-28-1])

・ 「#3013. 19世紀に非難された新古典主義的複合語」 ([2017-07-27-1])

・ 「#3166. 英製希羅語としての科学用語」 ([2017-12-27-1])

・ 「#3179. 「新古典主義的複合語」か「英製羅語」か」 ([2018-01-09-1])

・ 「#3368. 「ラテン語系」語彙借用の時代と経路」 ([2018-07-17-1])

・ 「#4191. 科学用語の意味の諸言語への伝播について」 ([2020-10-17-1])

・ 「#4449. ギリシア語の英語語形成へのインパクト」 ([2021-07-02-1])

・ 「#5718. ギリシア語由来の主な接尾辞,接頭辞,連結形」 ([2024-12-22-1])

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2024-12-22 Sun

■ #5718. ギリシア語由来の主な接尾辞,接頭辞,連結形 [greek][suffix][prefix][lexicology][word_formation][combining_form][morphology][latin][french][loan_word][borrowing]

Durkin (216--19) にかけて,英語に入ったギリシア語由来の要素が列挙されている.接尾辞 (suffix),接頭辞 (prefix),連結形 (combining_form) に分けて,主たるものを列挙しよう.ラテン語やフランス語からの借用語のなかに混じっている要素もあり,究極的にはギリシア語由来であることが気づかれていないものも含まれているのではないか.

[ 接尾辞 ]

-on (plural -a), -ter, -terion, -ma/-mat- (adj. -matic), the family of -ize/-ise (-ist/-ast, -ism, -asm), -ite, -ess, -oid, -isk, -(t)ic, -istic(al), -astic(al)

[ 接頭辞 ]

a(n)-, amph(i)-, an(a)-, anti-, ap(o)-, cat(a)-/kat(a)-, di(a)-, dys-, a(n)-, end(o)-, exo-, ep(i)-, hyper-, hyp(o)-, met(a)-, par(a)-, peri-, pro-, pros-, syn-/sys-

[ 連結形 ]

acro- "high; of the extremities", agath(o)- "good", all(o)- "other, alternate, distinct", arch- "chief; original", argyr(o)- "silver", aut(o)- "self(-induced); spontaneous", bary-/bar(o)- "heavy; low; internal", brachy- "short", brady- "slow", cac(o)- "bad", chlor(o)- "green; chlorine", chrys(o)- "gold; golden-yellow", cry(o)- "freezing; low-temperature", crypt(o)- "secret; concealed", cyan(o)- "blue", dipl(o)- "twofold, double", dolich(o)- "long", erythr(o)- "red", eu- "good, well", glauc(o)- "bluish-green, grey", gluc(o)- "glucose"/glyc(o)- "sugar; glycerol"/glycy- "sweet", gymn(o)- "naked, bare", heter(o)- "other, different", hol(o)- "whole, entire", homeo- "similar; equal", hom(o)- "same", leuc/k(o)- "white", macro- "(abnormally) large", mega- "huge; very large", megal(o)- "large; grandiose" and -megaly "abnormal enlargement", melan(o)- "black; dark-colored; pigmented", mes(o)- "middle", micr(o)- "(very) small", nano- "one thousand-millionth; extremely small", necr(o)- "dead; death", ne(o)- "new; modified; follower", olig(o)- "few; diminished; retardation", orth(o)- "upright; straight; correct", oxy- "sharp, pointed; keen", pachy- "thick", pan(to)- "all", picr(o)- "bitter", platy- "broad, flat", poikil(o)- "variegated; variable", poly- "much, many", proto- "first", pseud(o)- "false", scler(o)- "hard", soph(o)- and -sophy "skilled; wise", tachy- "swift", tel(e)- "(operating) at a distance", tele(o)- "complete; completely developed", therm(o)- "warm, hot", trachy- "rough"

英語ボキャビルのおともにどうぞ.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2024-12-14 Sat

■ #5710. 12月21日(土)の朝カルのシリーズ講座第9回「英語,ラテン・ギリシア語に憧れる」のご案内 [asacul][notice][kdee][etymology][hel_education][helkatsu][link][lexicology][vocabulary][latin][greek][renaissance][emode][voicy][heldio]

・ 日時:12月21日(土) 17:30--19:00

・ 場所:朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室

・ 形式:対面・オンラインのハイブリッド形式(1週間の見逃し配信あり)

・ お申し込み:朝日カルチャーセンターウェブサイトより

今年度の朝カルシリーズ講座「語源辞典でたどる英語史」が,月に一度のペースで順調に進んでいます.主に『英語語源辞典』(研究社)を参照しながら,英語語彙史をたどっていくシリーズです.

1週間後に開講される第9回では主に初期近代英語期におけるラテン語およびギリシア語の語彙的影響を評価します.16--17世紀の初期近代英語期は英国ルネサンスの時代に当たり,古典語への傾倒が顕著でした.知識が増大し学問も発展したために新しい語彙が大量に必要となり,そのニーズに応えるべくラテン語やギリシア語の単語や要素が持ち出されたのです.結果として,古典語に基づく借用語や新語がおびただしく導入され,英語語彙は空前の拡張を遂げることになります.

今回の講座では,古典語からの借用語に主に注目し,この時期の語彙拡大の悲喜劇を観察してみたいと思います.ぜひ皆さんもこの時代にもたらされたラテン・ギリシア語系のオモシロ単語を探してみてください.

本シリーズ講座の各回は独立していますので,過去回への参加・不参加にかかわらず,今回からご参加いただくこともできます.過去8回分については,各々概要をマインドマップにまとめていますので,以下の記事をご覧ください.

・ 「#5625. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第1回「英語語源辞典を楽しむ」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-09-20-1])

・ 「#5629. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第2回「英語語彙の歴史を概観する」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-09-24-1])

・ 「#5631. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第3回「英単語と「グリムの法則」」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-09-26-1])

・ 「#5639. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第4回「現代の英語に残る古英語の痕跡」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-10-04-1])

・ 「#5646. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第5回「英語,ラテン語と出会う」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-10-11-1])

・ 「#5650. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第6回「英語,ヴァイキングの言語と交わる」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-10-15-1])

・ 「#5669. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第7回「英語,フランス語に侵される」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-11-03-1])

・ 「#5704. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第8回「英語,オランダ語と交流する」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-12-08-1])

本講座の詳細とお申し込みはこちらよりどうぞ.『英語語源辞典』(研究社)をお持ちの方は,ぜひ傍らに置きつつ受講いただければと存じます(関連資料を配付しますので,辞典がなくとも受講には問題ありません).

(以下,後記:2024/12/17(Tue))

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

2024-12-02 Mon

■ #5698. royal we の起源と古英語・中英語 [greek][latin][royal_we][monarch][sociolinguistics][oe][me]

昨日の記事「#5697. royal we は「君主の we」ではなく「社会的不平等の複数形」?」 ([2024-12-01-1]) に引き続き「君主の we」 (royal_we) に注目する.術語としては "plural of majesty", "plural of inequality" なども用いられているが,いずれも1人称複数代名詞の同じ用法を指している.

Mustanoja (124) は,"plural of majesty" という用語を使いながら,ラテン語どころかギリシア語にまでさかのぼる用例の起源を示唆している.その上で,英語史における古い典型例として,中英語より「ヘンリー3世の宣言」での用例に言及していることに注目したい.

PLURAL OF MAJESTY. --- Another variety of the sociative plural (pluralis societatis) exists as the plural of majesty (pluralis majestatis), likewise characterised by the use of the pronoun of the first person plural for the first person singular. The plural of majesty originates in a living sovereign's habit of thinking of himself as an embodiment of the whole community. As the use of the plural becomes a mere convention, the original significance of this plurality tends to disappear. The plural of majesty is found in the imperial decrees of the later Roman Empire and in the letters of the early Roman bishops, but it can be traced to even earlier times, to Greek syntactical usage (cf. H. Zilliacus, Selbstgefühl und Servilität: Studien zum unregelmâssigen Numerusgebrauch im Griechischen, SSF-GHL XVIII, 3, Helsinki 1953). The plural of majesty is extensively used in medieval Latin. In OE it does not seem to be attested. OE royal charters, for example, have the singular (ic Offa þurh Cristes gyfe Myrcena kining; ic Æþelbald cincg, etc.). The plural of majesty begins to be used in ME. A typical ME example is the following quotation from the English proclamation of Henry III (18 Oct., 1258), a characteristic beginning of a royal charter: --- Henry, thurȝ Gode fultume king of Engleneloande, Lhoaverd on Yrloande, Duk on Normandi, on Aquitaine, and Eorl on Anjow, send igretinge to alle hise holde, ilærde ond ileawede, on Huntendoneschire: thæt witen ȝe alle þæt we willen and unnen þæt . . ..

引用中の "the English proclamation of Henry III (18 Oct., 1258)" (「ヘンリー3世の宣言」)での用例について,ナルホドと思いはする.しかし「#5696. royal we の古英語からの例?」 ([2024-11-30-1]) の最後の方で触れたように,この例ですら確実な royal we の用法かどうかは怪しいのである.この宣言の原文については「#2561. The Proclamation of Henry III」 ([2016-05-01-1]) を参照.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2024-11-11 Mon

■ #5677. 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』の接辞リスト(129種) [etymology][prefix][suffix][vocabulary][hel_education][lexicology][word_formation][derivation][derivative][morphology][latin][greek][review]

昨日の記事「#5676. 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』の300語根」 ([2024-11-10-1]) に引き続き,同書の付録 (344--52) に掲載されている主要な接辞のリストを挙げたいと思います.接頭辞 (prefix) と接尾辞 (suffix) を合わせて129種の接辞が紹介されています.

【 主な接頭辞 】

| a-, an- | ない (without) |

| ab-, abs- | 離れて,話して (away) |

| ad-, a-, ac-, af-, ag-, al-, an-, ap-, ar-, as-, at- | …に (to) |

| ambi- | 周りに (around) |

| anti-, ant- | 反… (against) |

| bene- | よい (good) |

| bi- | 2つ (two) |

| co- | 共に (together) |

| com-, con-, col-, cor- | 共に (together);完全に (wholly) |

| contra-, counter- | 反対の (against) |

| de- | 下に (down);離れて (away);完全に (wholly) |

| di- | 2つ (two) |

| dia- | 横切って (across) |

| dis-, di-, dif- | ない (not);離れて,別々に (apart) |

| dou-, du- | 2つ (two) |

| en-, em- | …の中に (into);…にする (make) |

| ex-, e-, ec-, ef- | 外に (out) |

| extra- | …の外に (outside) |

| fore- | 前もって (before) |

| in-, im-, il-, ir-, i- | ない,不,無,非 (not) |

| in-, im- | 中に,…に (in);…の上に (on) |

| inter- | …の間に (between) |

| intro- | 中に (in) |

| mega- | 巨大な (large) |

| micro- | 小さい (small) |

| mil- | 1000 (thousand) |

| mis- | 誤って (wrongly);悪く (badly) |

| mono- | 1つ (one) |

| multi- | 多くの (many) |

| ne-, neg- | しない (not) |

| non- | 無,非 (not) |

| ob-, oc-, of-, op- | …に対して,…に向かって (against) |

| out- | 外に (out) |

| over- | 越えて (over) |

| para- | わきに (beside) |

| per- | …を通して (through);完全に (wholly) |

| post- | 後の (after) |

| pre- | 前に (before) |

| pro- | 前に (forward) |

| re- | 元に (back);再び (again);強く (strongly) |

| se- | 別々に (apart) |

| semi- | 半分 (half) |

| sub-, suc-, suf-, sum-, sug-, sup-, sus- | 下に (down),下で (under) |

| super-, sur- | 上に,越えて (over) |

| syn-, sym- | 共に (together) |

| tele- | 遠い (distant) |

| trans- | 越えて (over) |

| tri- | 3つ (three) |

| un- | ない (not);元に戻して (back) |

| under- | 下に (down) |

| uni- | 1つ (one) |

【 名詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -age | 状態,こと,もの |

| -al | こと |

| -ance | こと |

| -ancy | 状態,もの |

| -ant | 人,もの |

| -ar | 人 |

| -ary | こと,もの |

| -ation | すること,こと |

| -cle | もの,小さいもの |

| -cracy | 統治 |

| -ee | される人 |

| -eer | 人 |

| -ence | 状態,こと |

| -ency | 状態,もの |

| -ent | 人,もの |

| -er, -ier | 人,もの |

| -ery | 状態,こと,もの;類,術;所 |

| -ess | 女性 |

| -hood | 状態,性質,期間 |

| -ian | 人 |

| -ics | 学,術 |

| -ion, -sion, -tion | こと,状態,もの |

| -ism | 主義 |

| -ist | 人 |

| -ity, -ty | 状態,こと,もの |

| -le | もの,小さいもの |

| -let | もの,小さいもの |

| -logy | 学,論 |

| -ment | 状態,こと,もの |

| -meter | 計 |

| -ness | 状態,こと |

| -nomy | 法,学 |

| -on, -oon | 大きなもの |

| -or | 人,もの |

| -ory | 所 |

| -scope | 見るもの |

| -ship | 状態 |

| -ster | 人 |

| -tude | 状態 |

| -ure | こと,もの |

| -y | こと,集団 |

【 形容詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -able | できる,しやすい |

| -al | …の,…に関する |

| -an | …の,…に関する |

| -ant | …の,…の性質の |

| -ary | …の,…に関する |

| -ate | …の,…のある |

| -ative | …的な |

| -ed | …にした,した |

| -ent | している |

| -ful | …に満ちた |

| -ible | できる,しがちな |

| -ic | …の,…のような |

| -ical | …の,…に関する |

| -id | …状態の,している |

| -ile | できる,しがちな |

| -ine | …の,…に関する |

| -ior | もっと… |

| -ish | ・・・のような |

| -ive | ・・・の,・・・の性質の |

| -less | ・・・のない |

| -like | ・・・のような |

| -ly | ・・・のような;・・・ごとの |

| -ory | ・・・のような |

| -ous | ・・・に満ちた |

| -some | ・・・に適した,しがちな |

| -wide | ・・・にわたる |

【 動詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -ate | ・・・にする,させる |

| -en | ・・・にする |

| -er | 繰り返し・・・する |

| -fy, -ify | ・・・にする |

| -ish | ・・・にする |

| -ize | ・・・にする |

| -le | 繰り返し・・・する |

【 副詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -ly | ・・・ように |

| -ward | ・・・の方へ |

| -wise | ・・・ように |

・ 池田 和夫 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』 研究社,2019年.

2024-11-10 Sun

■ #5676. 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』の300語根 [etymology][prefix][suffix][vocabulary][hel_education][lexicology][word_formation][derivation][derivative][morphology][latin][greek][review]

英語ボキャビルのための本を紹介します.研究社から出版されている『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』です.300の語根を取り上げ,語根と意味ベースで派生語2500語を学習できるように構成されています.研究社の伝統ある『ライトハウス英和辞典』『カレッジライトハウス英和辞典』『ルミナス英和辞典』『コンパスローズ英和辞典』の辞書シリーズを通じて引き継がれてきた語根コラムがもとになっています.

選ばれた300個の語根は,ボキャビル以外にも,英語史研究において何かと役に立つリストとなっています.目次に従って,以下に一覧します.

cess (行く)

ceed (行く)

cede (行く)

gress (進む)

vent (来る)

verse (向く)

vert (向ける)

cur (走る)

pass (通る)

sta (立つ)

sist (立つ)

sti (立つ)

stitute (立てた)

stant (立っている)

stance (立っていること)

struct (築く)

fact (作る,なす)

fic (作る)

fect (作った)

gen (生まれ)

nat (生まれる)

crease (成長する)

tain (保つ)

ward (守る)

serve (仕える)

ceive (取る)

cept (取る)

sume (取る)

cap (つかむ)

mote (動かす)

move (動く)

gest (運ぶ)

fer (運ぶ)

port (運ぶ)

mit (送る)

mis (送られる)

duce (導く)

duct (導く)

secute (追う)

press (押す)

tract (引く)

ject (投げる)

pose (置く)

pend (ぶら下がる)

tend (広げる)

ple (満たす)

cide (切る)

cise (切る)

vary (変わる)

alter (他の)

gno (知る)

sent (感じる)

sense (感じる)

cure (注意)

path (苦しむ)

spect (見る)

vis (見る)

view (見る)

pear (見える)

speci (見える)

pha (現われる)

sent (存在する)

viv (生きる)

act (行動する)

lect (選ぶ)

pet (求める)

quest (求める)

quire (求める)

use (使用する)

exper (試みる)

dict (言う)

log (話す)

spond (応じる)

scribe (書く)

graph (書くこと)

gram (書いたもの)

test (証言する)

prove (証明する)

count (数える)

qua (どのような)

mini (小さい)

plain (平らな)

liber (自由な)

vac (空の)

rupt (破れた)

equ (等しい)

ident (同じ)

term (限界)

fin (終わり,限界)

neg (ない)

rect (真っすぐな)

prin (1位)

grade (段階)

part (部分)

found (基礎)

cap (頭)

medi (中間)

popul (人々)

ment (心)

cord (心)

hand (手)

manu (手)

mand (命じる)

fort (強い)

form (形,形作る)

mode (型)

sign (印)

voc (声)

litera (文字)

ju (法)

labor (労働)

tempo (時)

uni (1つ)

dou (2つ)

cent (100)

fare (行く)

it (行く)

vade (行く)

migrate (移動する)

sess (座る)

sid (座る)

man (とどまる)

anim (息をする)

spire (息をする)

fa (話す)

fess (話す)

cite (呼ぶ)

claim (叫ぶ)

plore (叫ぶ)

doc (教える)

nounce (報じる)

mon (警告する)

audi (聴く)

pute (考える)

tempt (試みる)

opt (選ぶ)

cri (決定する)

don (与える)

trad (引き渡す)

pare (用意する)

imper (命令する)

rat (数える)

numer (数)

solve (解く)

sci (知る)

wit (知っている)

memor (記憶)

fid (信じる)

cred (信じる)

mir (驚く)

pel (追い立てる)

venge (復讐する)

pone (置く)

ten (保持する)

tin (保つ)

hibit (持つ)

habit (持っている)

auc (増す)

ori (昇る)

divid (分ける)

cret (分ける)

dur (続く)

cline (傾く)

flu (流れる)

cas (落ちる)

cid (落ちる)

cease (やめる)

close (閉じる)

clude (閉じる)

draw (引く)

trai (引っ張る)

bat (打つ)

fend (打つ)

puls (打つ)

cast (投げる)

guard (守る)

medic (治す)

nur (養う)

cult (耕す)

ly (結びつける)

nect (結びつける)

pac (縛る)

strain (縛る)

strict (縛られた)

here (くっつく)

ple (折りたたむ)

plic (折りたたむ)

ploy (折りたたむ)

ply (折りたたむ)

tribute (割り当てる)

tail (切る)

sect (切る)

sting (刺す)

tort (ねじる)

frag (壊れる)

fuse (注ぐ)

mens (測る)

pens (重さを量る)

merge (浸す)

velop (包む)

veil (覆い)

cover (覆う;覆い)

gli (輝く)

prise (つかむ)

cert (確かな)

sure (確かな)

firm (確実な)

clar (明白な)

apt (適した)

due (支払うべき)

par (等しい)

human (人間の)

common (共有の)

commun (共有の)

semble (一緒に)

simil (同じ)

auto (自ら)

proper (自分自身の)

potent (できる)

maj (大きい)

nov (新しい)

lev (軽い)

hum (低い)

cand (白い)

plat (平らな)

minent (突き出た)

sane (健康な)

soph (賢い)

sacr (神聖な)

vict (征服した)

text (織られた)

soci (仲間)

demo (民衆)

civ (市民)

polic (都市)

host (客)

femin (女性)

patr (父)

arch (長)

bio (命,生活,生物)

psycho (精神)

corp (体)

face (顔)

head (頭)

chief (頭)

ped (足)

valu (価値)

delic (魅力)

grat (喜び)

hor (恐怖)

terr (恐れさせる)

fortune (運)

hap (偶然)

mort (死)

art (技術)

custom (習慣)

centr (中心)

eco (環境)

circ (円,環)

sphere (球)

rol (回転;巻いたもの)

tour (回る)

volve (回る)

base (基礎)

norm (標準)

ord (順序)

range (列)

int (内部の)

front (前面)

mark (境界)

limin (敷居)

point (点)

punct (突き刺す)

phys (自然)

di (日)

hydro (水)

riv (川)

mari (海)

sal (塩)

aster (星)

camp (野原)

mount (山)

insula (島)

vi (道)

loc (場所)

geo (土地)

terr (土地)

dom (家)

court (宮廷)

cave (穴)

bar (棒)

board (板)

cart (紙)

arm (武装,武装する)

car (車)

leg (法律)

reg (支配する)

her (相続)

gage (抵当)

merc (取引)

・ 池田 和夫 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』 研究社,2019年.

2024-11-04 Mon

■ #5670. Grassmann's law --- 「グラスマンの法則」 [grassmanns_law][grimms_law][sound_change][sanskrit][greek][indo-european][dissimilation][verners_law][aspiration][phonetics][consonant]

著名なグリムの法則 (grimms_law) には,提案された当時より,様々な例外があることが気づかれていた.最も有名なのはヴェルネルの法則 (verners_law) に関する例外だが,もう1つグラスマンの法則 (grassmanns_law) というものがある.『新英語学辞典』 '(209--300) より,該当の解説を引く.

次に発見された例外は,通常グラスマンの法則 (Grassmann's law) と呼ばれるものである.ある系列の印欧語の対応は Grimm が設定した型に合致せず,説明が困難であったが,Herman Grassmann (1809--77) はギリシア語やサンスクリットのデータを調べ,これらの言語では例外的に不規則な対応を発達させたことを明らかにした.例えば

Goth. Skt -biudan 'offer' bódhāmi 'notice' dauhtar 'daughter' duhitā' gagg 'street' jánghā 'leg'

等の対応において,グリムの法則によればゲルマン語の b, d, g に対応するサンスクリットの語頭は帯気音 (bh, dh, gh) でなければならないのに非帯気音である.Grassmann は,これはギリシア語およびサンスクリットにおいて,二つの隣接する音節で帯気音が続いたとき,どちらか一つは異化 (DISSIMILATION) によって非帯気音になる現象のせいであることを発見した.ここにおいて言語学者は,単音の特徴や音声環境だけでなく,相接する音節との関係にも注意しなければならないことを知ったのである.

Bussmann の用語辞典からも引いておこう (198--99) .

Grassmann's law (also dissimilation of aspirates)

Discovered by Grassmann (1863), sound change occurring independently in Sanskrit and Greek which consistently results in a dissimilation of aspirated stops. If at least two aspirated stops occur in a single word, then only the last stop retains its aspiration, all preceding aspirates are deaspirated; cf. IE *bhebhoṷdhe > Skt bubodha 'had awakened,' IE *dhidhēhmi > Grk títhēmi 'I set, I put.' This law, which was discovered through internal reconstruction, turned a putative 'exception' to the Germanic sound shift (⇒ 'Grimm's law). . . into a law.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics''. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

2024-10-14 Mon

■ #5649. いつ <l> の綴字を重ねるか? [spelling][orthography][latin][greek][french][prefix][etymology][l]

昨日の記事「#5648. <l> の綴字を重ねるか否かの問題」 ([2024-10-13-1]) に続き,<ll> の話題.今回はイギリス英語では <ll> と重ね,アメリカ英語では <l> と1つのみ,という既知の傾向は別として,どのような単語において <ll> が現われるか,その分布をみてみたい.

昨日,次のように述べた.

<ll> はもともと古典語にゆかりのある綴字だったが,そこへ非古典語であるフランス語が混乱要因として参入してきた.フランス語は古典語由来の重ねた <ll> をそのまま受け継がず,1重化した <l> で継承することがしばしばあったために,それらが混在している英語語彙は正書法上 <l> を重ねるか否かについての厄介な問題を抱え込むことになったのだ.

<ll> の分布について,Carney (250) の説明と単語例の列挙を引用しよう.

Normally, <l> would double after a short vowel in a monosyllable (bell, cell, doll, mill, etc.), but there are some exceptions. There are all marginal in various ways, usually by abbreviation: technical loan col ('gap between hills' < French); gal (< girl), pal (< Romany); technical abbreviations bet (< the name '(A. G.) Bell', = 'unit of power comparison'), cel (< celluloid . . .), gel (< gelatine), mel ('perpetual unit of pitch'), mil (< millimetre), nil (contraction of Latin nihil); short names Hal (< Henry), Sal (< Sally) . . . .

Examples of <-ll-> with prefixes . . .:

- (reduced vowel): alleviate, alliteration, allude, allusion, ally (v.); collate, collateral, collect (v.), collide, collision.

- (unreduced vowel): Allocate, ally (n.); collect (n.), colleague, college, collimate, colloquy; illegal, illegible, illicit, illimitable, illuminate, illusion, illustrate; pellucid.

There are quite a few words which resemble the above and in which the <-ll-> is not covered by other doubling conventions: allegory, allergy, alligator. There is some etymological uncertainty about allot, allow, and allure. Allay has come to have a §Latinate appearance in spite of its Old English origin (a + lecgan). To the average reader these spellings must seem to belong with the §Latinate prefixes.

A good many words . . . have <-ll-> in the third syllable from the end of a free-form after a stressed short vowel. The ending <-ion> seems to require this spelling, but not in all instances: billion, bullion, galleon, million, mullion, pillion, postillion, stallion, but also battalion, pavilion, verlion. Compare doubled and single <r> in carrion--clarion.

Other examples of <-ll-> unaccounted for are: ballerina, ballistic, balloon, bellicose, brilliant, bulletin, calligraphy, calliopsis, camellia, colliery, ebullient, ellipse, embellish, fallacious, fallacy, fallible, gallery, gallium, halleluja, hallucinate, hellebore, intellect, intelligent, mellifluous, miscellany, palliate, pallium, parallel, pollute, shallot, shillelagh, tellurium.

Pseudo-compounds are: ballyhoo, bulldozer, hullaballoo, lollipop, scallywag.

<ll> をめぐる少々の傾向と諸々の混沌がつかめるのではないか.英語の正書法はかくも複雑である.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

2024-10-13 Sun

■ #5648. <l> の綴字を重ねるか否かの問題 [spelling][orthography][ame_bre][latin][greek][french][l]

英語の正書法では,<l> を重ねるかどうかが問題となるケースが少なからずある.

まず思い浮かぶのは traveler か traveller かの違いである.「#240. 綴字の英米差は大きいか小さいか?」 ([2009-12-23-1]) でみたように,典型的にアメリカ綴字では <l> は1つにとどまるが,イギリス綴字では <l> を重ねるのが規則である.しかし,そうかと思えば,アメリカ綴字の fulfill はむしろ <l> を重ね,イギリス綴字の fulfil は重ねないので,気が狂いそうになる.

<l> を重ねるか否かの綴字のヴァリエーションは古英語期よりあるといえばあり,問題としては歴史も深いし根も深いといってよいだろう.綴字として <l> が1つでも2つでも,結果として周囲の発音には影響を与えないので,役割不明であるという点においてたちが悪い.

私自身は,重ねた <ll> の綴字の本質は,直前の母音が「歴史的に」短母音であることを積極的に示すことにあると考えているが,現実にはそれほどたやすく片付けられる話題ではなさそうだ.現代英語の正書法を精査した Carney (250) は,"Distribution of <ll>" と題する1節にて,この問題を論じている.その節の冒頭部分を引用する.

There is more difficulty in accounting for the occurrence of double <-ll-> than for the double spelling of any other consonant. This is partly due to the frequency of <-ll-> in Latin and Greek stems and partly because §Latinate words borrowed by way of French may no longer have recognizable constituents.

<ll> はもともと古典語にゆかりのある綴字だったが,そこへ非古典語であるフランス語が混乱要因として参入してきた.フランス語は古典語由来の重ねた <ll> をそのまま受け継がず,1重化した <l> で継承することがしばしばあったために,それらが混在している英語語彙は正書法上 <l> を重ねるか否かについての厄介な問題を抱え込むことになったのだ.なるほど,英語らしいといえば英語らしい結果といってよい.残念でもありながら面白くもある.

ただし,現代英語の正書法の原則としていうならば,おおよそ次の規則が成立するのも確かである (Carney 251fn) .

In the Hanna (1966) spelling rules, <l> is the default spelling and:

1 <ll> word-final accented after /ɔː/ or a short vowel (tall, mill, bell, pull, hull).

<ll> の話題については,Voicy heldio で取り上げたことがある.「#456. -l なのか -ll なのか問題 ー till/until, travel(l)er, distil(l)」をお聴きいただければ.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

2024-05-28 Tue

■ #5510. 哲学から迫るか,文学から迫るか --- 言語学史を貫く対立軸 [history_of_linguistics][greek]

Robins による言語学史概説の第2章では古代ギリシアの言語学が論じられる.そこでの主要な論争としては,naturalist vs. conventionalist,そして analogist vs. anomalist の2種類があり,これについては「#1315. analogist and anomalist controversy (1)」 ([2012-12-02-1]) および「#1316. analogist and anomalist controversy (2)」 ([2012-12-03-1]) で紹介した.

上記2種類の対立は,互いに絡み合う複雑な論点を経つつ,新たな対立へと発展していった.言語を哲学的な角度からみるか,あるいは文学的な角度からみるか,の対立だ.この新生の対立軸は,古代から中世にかけての言語学史に通底するテーマとなったし,ある意味で近現代にまで持ち越されている.Robins (28) を引用する.

Linguistics, like other sciences in Antiquity, lay under the general influence of Aristotelian scientific method, but in the contrasting tendencies of the Stoic philosophers and the Alexandrian literary critics one sees the opposition between philosophical and literary considerations as the determining factors in the development of linguistics. With the later full development of Greek grammar, literary interests predominated, but throughout Antiquity and the Middle Ages this conflict of principle, now tacit, now explicitly argued, can be observed as a recurrent feature of the history of linguistic thought and practice.

確かに言語学上の議論の多くは,規則か例外か,規範か記述か,創造か慣習か,ラングかパロールかといった2項対立を軸に展開していくことが多い.このような議論の伝統の淵源は,古代ギリシアに求められるということか.

・ Robins, R. H. A Short History of Linguistics. 4th ed. Longman: London and New York, 1997.

2024-05-23 Thu

■ #5505. 古代ギリシアの方言観 [greek][dialect][dialectology][hellenic][koine][lingua_franca]

よく知られているように,古代ギリシア人はギリシア語以外の言語・民族については「バルバロイ」と蔑視する姿勢を示したが,ギリシア語諸方言についてはどのように見ていたのだろうか.Robins (15) に,古代ギリシアの他言語に対する態度やギリシア語内部の諸方言への眼差しを解説している箇所がある.特に後者を扱っている箇所を引用しよう.

. . . . the Greek designation of alien speakers as bárbaroi (βάρβαροι, whence our word barbarian), i.e. people who speak a language other than Greek, is probably indicative of their attitude.

Quite different was the Greek awareness of their own dialectal divisions. The Greek language in Antiquity was more markedly divided into fairly sharply differentiated dialects than many other languages were. This was due both to the settlement of the Greek-speaking areas by successive waves of invaders, and to the separation into relatively small and independent communities that the mountainous configuration of much of the Greek mainland and the scattered islands of the adjoining seas forced on them. But that these dialects were dialects of a single language and that the possession of this language united the Greeks as a whole people, despite the almost incessant wars waged between the different 'city states' of the Greek world, is attested by at least one historian: Herodotus, in his account of the major achievement of a temporarily united Greece against the invading Persians at the beginning of the fifth century B.C., puts into the mouths of the Greek delegates a statement that among the bonds of unity among the Greeks in resisting the barbarians was 'the whole Greek community, being of one blood and one tongue'.

引用最後のヘロドトス (8.114.2) への言及が興味深い.おそらく古代ギリシア人たちは明確に分かれていたギリシア語諸方言の存在を互いに認識していた.そして,それらを異なる方言とこそ捉えてはいたが,異なる言語とは捉えていなかった.諸方言からなるギリシア語は,ギリシア民族を(ペルシアに対抗して)まとめ上げる役割を果たしていたということだ.

考えてみれば,ギリシア語は dialect という単語を生み出した母体であり,諸方言間を平準化した共通語 (koine) を誇った言語でもあった.関連して,以下の記事も参照されたい.

・ 「#1454. ギリシャ語派(印欧語族)」 ([2013-04-20-1])

・ 「#2752. dialect という用語について」 ([2016-11-08-1])

・ 「#1671. dialect contact, dialect mixture, dialect levelling, koineization」 ([2013-11-23-1])

・ 「#1391. lingua franca (4)」 ([2013-02-16-1])

・ Robins, R. H. A Short History of Linguistics. 4th ed. Longman: London and New York, 1997.

2024-04-28 Sun

■ #5480. 2022年の日本歴史言語学会のシンポジウム「日中英独仏・対照言語史ー語彙の近代化をめぐってー」の概要が公開されました [notice][jshl][symposium][historical_linguistics][lexicology][standardisation][emode][japanese][contrastive_language_history][german][french][chinese][latin][greek][renaissance]

1年半ほど前のことになりますが,2022年12月10日に日本歴史言語学会にてシンポジウム「日中英独仏・対照言語史ー語彙の近代化をめぐって」が開かれました(こちらのプログラムを参照).学習院大学でのハイブリッド開催でした.同年に出版された,高田 博行・田中 牧郎・堀田 隆一(編著)『言語の標準化を考える --- 日中英独仏「対照言語史」の試み』(大修館,2022年)が J-STAGE 上で公開されました.PDF形式で自由にダウンロードできますので,ぜひお読みいただければと思います.セクションごとに分かれていますので,以下にタイトルとともに抄録へのリンクを張っておきます.

・ 趣旨説明 「日中英独仏・対照言語史 --- 語彙の近代化をめぐって」(高田博行,学習院大学)

・ 講演1 「日本語語彙の近代化における外来要素の受容と調整」(田中牧郎,明治大学)

・ 講演2 「中国語の語彙近代化の生態言語学的考察 --- 新語の群生と「適者生存」のメカニズム」(彭国躍,神奈川大学)

・ 講演3 「初期近代英語における語彙借用 --- 日英対照言語史的視点から」(堀田隆一,慶應義塾大学)

・ 講演4 「ドイツ語の語彙拡充の歴史 --- 造語言語としてのアイデンティティー ---」(高田博行,学習院大学)

・ 講演5 「アカデミーフランセーズの辞書によるフランス語の標準化と語彙の近代化 ---フランス語の標準化への歩み」(西山教行,京都大学)

・ ディスカッション 「まとめと議論」

講演3を担当した私の抄録は次の通りです.

初期近代英語期(1500--1700年)は英国ルネサンスの時代を含み,同時代特有の 古典語への傾倒に伴い,ラテン語やギリシア語からの借用語が大量に英語に流れ込んだ.一方,同時代の近隣ヴァナキュラー言語であるフランス語,イタリア語,スペイン語,ポルトガル語などからの語彙の借用も盛んだった.これらの借用語は,元言語から直接英語に入ってきたものもあれば,他言語,典型的にはフランス語を窓口として,間接的に英語に入ってきたものも多い.さらには,借用要素を自前で組み合わせて造語することもしばしば行なわれた.つまり,初期近代英語における語彙の近代化・拡充は,様々な経路・方法を通じて複合的に実現されてきたのである.このような初期近代英語期の語彙事情は,実のところ,いくつかの点において明治期の日本語の語彙事情と類似している.本論では,英語と日本語について対照言語史的な視点を取りつつ,語彙の近代化の方法と帰結について議論する.

先に触れた編著書『言語の標準化を考える』で初めて対照言語史 (contrastive_language_history) というアプローチを導入しましたが,今回の論考はそのアプローチによる新たな挑戦として理解していただければと思います.

・ 高田 博行・田中 牧郎・彭 国躍・堀田 隆一・西山 教行 「日中英独仏・対照言語史ー語彙の近代化をめぐってー」『歴史言語学』第12号(日本歴史言語学会編),2024年.89--182頁.

・ 高田 博行・田中 牧郎・堀田 隆一(編著)『言語の標準化を考える --- 日中英独仏「対照言語史」の試み』 大修館,2022年.

2024-02-15 Thu

■ #5407. 言語学史は古代ギリシアから始まる? [greek][history_of_linguistics]

Robins による言語学史の入門書は,予想される通り古代ギリシアの伝統から始まる.西洋人の著わした言語学史として標準的な始め方であり,ことさらに「言い訳」する必要もないかと思われるのだが,Robins は言い訳をする.古代ギリシアの偉業を,念のために振り返っているのだろう.Robins (12) の1節を読んでみる.

For the reasons given in the preceding chapter, it is sensible to begin the history of linguistic studies with the achievements of the ancient Greeks. This has to do, primarily, not with the merits of their work, which are very considerable, nor with the deficiencies in it that latter-day scholars looking back from the privileged standpoint of those at the far end of a long tradition, may justifiably point out. It is simply that the Greek thinkers on language, and on the problems raised by linguistic investigations, initiated in Europe the studies that we can call linguistic science in its widest sense, and that this science was a continuing focus of interest from Ancient Greece until the present day in an unbroken succession of scholarship, wherein each worker was conscious of and in some way reacting to the work of his predecessors.

古代ギリシアの言語論が,現代にまで続く西洋の言語論の源泉になっているということを確認しているものと読むことができる.なるほど,かつての言語論に非はあったとしても,現代までに訂正や補足を繰り返して,連続してきたことが重要だという主張なのだろう.これは西洋の言語学のみならず西洋の哲学の伝統などでもそうだが,認めてよいと思う.続いてきたものは強い.

・ Robins, R. H. A Short History of Linguistics. 4th ed. Longman: London and New York, 1997.

2024-02-06 Tue

■ #5398. ヘロドトスにみる言語の創成 [origin_of_language][greek][phrygian][herodotus][history_of_linguistics][popular_passage][bible][language_myth][heldio][voicy]

「歴史の父」こと古代ギリシア歴史家ヘロドトス (Herodotus, B.C. 485?--425?) の手になる著『歴史』に,言語創成 (origin_of_language) に関する有名な話が記されている.古代エジプト第26王朝の初代の王であるプサンメティコス1世 (Psammetichus [Psamtik], B.C. 664--610) が,最も古い言語は何かを明らかにするために,新生児を用いてある実験をした,という言い伝えである.これについて,Perseus Digital Library のテキストコレクションより,Herodotus, The Histories (ed. A. D. Godley) の第2巻の第2章(英訳版)を引用する.

Now before Psammetichus became king of Egypt, the Egyptians believed that they were the oldest people on earth. But ever since Psammetichus became king and wished to find out which people were the oldest, they have believed that the Phrygians were older than they, and they than everybody else. Psammetichus, when he was in no way able to learn by inquiry which people had first come into being, devised a plan by which he took two newborn children of the common people and gave them to a shepherd to bring up among his flocks. He gave instructions that no one was to speak a word in their hearing; they were to stay by themselves in a lonely hut, and in due time the shepherd was to bring goats and give the children their milk and do everything else necessary. Psammetichus did this, and gave these instructions, because he wanted to hear what speech would first come from the children, when they were past the age of indistinct babbling. And he had his wish; for one day, when the shepherd had done as he was told for two years, both children ran to him stretching out their hands and calling "Bekos!" as he opened the door and entered. When he first heard this, he kept quiet about it; but when, coming often and paying careful attention, he kept hearing this same word, he told his master at last and brought the children into the king's presence as required. Psammetichus then heard them himself, and asked to what language the word "Bekos" belonged; he found it to be a Phrygian word, signifying bread. Reasoning from this, the Egyptians acknowledged that the Phrygians were older than they. This is the story which I heard from the priests of Hephaestus' temple at Memphis; the Greeks say among many foolish things that Psammetichus had the children reared by women whose tongues he had cut out.

現代の観点からは1つの逸話にすぎないように思われるかもしれないが,言語の創成についてはいまだに分からないことが多いという事実は踏まえておく必要がある.もっと有名なもう1つの言い伝えは,言わずとしれた聖書の記述である.これについては「#2946. 聖書にみる言語の創成と拡散」 ([2017-05-21-1]) を参照.

関連して「#4612. 言語の起源と発達を巡る諸問題」 ([2021-12-12-1]),「#4614. 言語の起源と発達を巡る諸説の昔と今」 ([2021-12-14-1]) も挙げておきたい.

ちなみに,昨日の Voicy heldio にて関連する話題を取り上げた.「#980. 赤ちゃんは無言語状態で育てられても言語を習得できるのか? --- 目白大学の学生から寄せてもらった素朴な疑問」をお聴きいただければ.

2023-11-15 Wed

■ #5315. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (3) [terminology][diglossia][bilingualism][sociolinguistics][hel_education][greek]

「#5306. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (1)」 ([2023-11-06-1]),「#5311. 用語辞典でみる diglossia (2)」 ([2023-11-11-1]) に引き続き,diglossia (二言語変種使い分け)を考える.今回は Crystal の用語辞典より当該項目の解説を引く.

diglossia (n.) A term used in SOCIOLINGUISTICS to refer to a situation where two very different VARIETIES of a LANGUAGE CO-OCCUR throughout a SPEECH community, each with a distinct range of social function. Both varieties are STANDARDIZED to some degree, are felt to be alternatives by NATIVE-SPEAKERS and usually have special names. Sociolinguists usually talk in terms of a high (H) variety and a low (L) variety, corresponding broadly to a difference in FORMALITY: the high variety is learnt in school and tends to be used in church, on radio programmes, in serious literature, etc., and as a consequence has greater social prestige; the low variety tends to be used in family conversations, and other relatively informal settings. Diglossic situations may be found, for example, in Greek (High: Katharevousa; Low: Dhimotiki), Arabic (High: Classical; Low: Colloquial), and some varieties of German (H: Hochdeutsch; L: Schweizerdeutsch, in Switzerland). A situation where three varieties or languages are used with distinct functions within a community is called triglossia. An example of a triglossic situation is the use of French, Classical Arabic and Colloquial Tunisian Arabic in Tunisia, the first two being rated H and the Last L.

典型的な事例としてアラビア語や(スイス)ドイツ語に加えて,ギリシア語の Katharevusa (古代ギリシャ語に範を取った文語体)と Dhimotiki (自然発達した通俗体)を挙げているのは貴重である(cf. 「#1454. ギリシャ語派(印欧語族)」 ([2013-04-20-1])).

複数の用語辞典の記述を比べると,その用語・概念について何が広く共有されている中核的な情報なのかを確認できるし,逆に特定の辞典にしか挙げられていない事例や学説を集めていくことによって,周辺知識をもれなく拾うことができる.辞典も辞書も複数引くことを原則としたい.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2023-10-24 Tue

■ #5293. ギリシア語派の解説 --- heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズ [voicy][heldio][hel_education][link][notice][bchel][hellenic][greek][khelf][indo-european]

一昨日の hellog 記事「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) でもお伝えしましたが,目下 Voicy heldio によるオンライン読書会シリーズに力を入れているところです.ウェブ時代の新スタイルの読書会・勉強会として,とてもおもしろい試みになっているという実感があります.参加者は今のところ20名程度ですが,読んでいる本のサイズを考えると理屈上は向こう数年間にわたって続いていくシリーズ企画ということもあり,これからメンバーがゆっくりと少しずつでも増えていくと楽しそうだなと夢想しています.毎回200円の有料配信ですが,第1チャプターは試聴可能となっています.

最新回は,昨日アップされた上記の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (19) Hellenic」です.毎週1,2回,指定の英語史書をゆっくりと1節ずつ読み進めていくという企画で,7月に開始したばかりなので,昨日ようやく第19節にたどり着いたところです.英語史といえど,まだ英語の歴史に本格的に入る前の段階で,印欧語族を構成する各語派を概説しているところです.その1つがギリシア語派ということになります.

今回はテキストに沿ってあくまで印欧語族のなかのギリシア語派を紹介しているのですが,この語派(とりわけギリシア語そのもの)の英語史上の意義については,さほどお話ししていません.ギリシア語については本ブログで greek の記事群にて多く取り上げてきましたが,ギリシア語の英語史上のエッセンスを箇条書きすれば,次の4点となるでしょうか.

・ 古典ギリシア語は『新訳聖書』の言語である.

・ ギリシア語とギリシア文明は,現代まで続く西洋文明の基礎を形成する.そこから,英語自体が拠って立つのも究極的にはギリシア語とギリシア文明といってよい側面がある.

・ ギリシア語は,ラテン語に多大な影響を与え,ラテン語はフランス語に影響を与え,フランス語は英語に影響を与えてきた.ギリシア語が英語史上重要であるのはこのような事情による.

・ ギリシア語は古代・中世・近現代を通じて,上記の歴史的経緯により汎ヨーロッパ的な威信言語とみなされてきた.現代でもとりわけ学術の分野では,国際的な学名や学術用語は,しばしばギリシア語要素によって作られる (cf. 新古典主義的複合語 (neo-classical compounds)).現代の最たる国際語である英語も,その伝統と要素を多分に受け継いでいる.

ギリシア語に関連した Voicy heldio の配信回としては 「#137. 英語とギリシア語の関係って?」もお聴きください.

なお,今晩19:30~20:00の間に,こちらの Voicy heldio にてゲストを招いての生放送を配信する予定です.その内容は,テキストの次の節「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (20) Albanian」を題材とした初の「オンライン読書会生実況中継」(?)となる予定です.今回に関しましては,放送回の概要欄などにテキストも添付しますのでライヴあるいはアーカイヴにてお気軽にお聴きいただければ.

このように一風変わったオンライン読書回シリーズですが,関心のある方はぜひ覗いていただければ.精読しているテキストは,こちらの Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013. です.名著であることは保証します.

2023-10-10 Tue

■ #5279. Z の推し活 [notice][z][alphabet][ame_bre][greek][latin][french][academy][shakespeare][consonant][youtube][grapheme][link][spelling][helsta]

一昨日配信した YouTube の「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」の最新回は「#169. なぜ Z はアルファベットの最後に追いやられたのか? --- 時代に翻弄された日陰者 Z の物語」です.歴史的に「日陰者 Z」と称されてきたかわいそうな文字にスポットライトを当て,12分ほど集中して語りました.これで Z が多少なりとも汚名返上できればよいのですが.

z の文字については,この hellog,および Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」等の媒体でも,様々に取り上げてきました.Z の汚名返上のために助力してきた次第ですが,さすがに Z に関する話題はこれ以上見つからなくなってきましたので,ネタとしてはいったん打ち切りになりそうです.

これまでの Z の推し活の履歴を列挙します.

[ hellog ]

・ 「#305. -ise か -ize か」 ([2010-02-26-1])

・ 「#314. -ise か -ize か (2)」 ([2010-03-07-1])

・ 「#446. しぶとく生き残ってきた <z>」 ([2010-07-17-1])

・ 「#447. Dalziel, MacKenzie, Menzies の <z>」 ([2010-07-18-1])

・ 「#799. 海賊複数の <z>」 ([2011-07-05-1])

・ 「#964. z の文字の発音 (1)」 ([2011-12-17-1])

・ 「#965. z の文字の発音 (2)」 ([2011-12-18-1])

・ 「#1914. <g> の仲間たち」 ([2014-07-24-1])

・ 「#2916. 連載第4回「イギリス英語の autumn とアメリカ英語の fall --- 複線的思考のすすめ」」 ([2017-04-21-1])

・ 「#2925. autumn vs fall, zed vs zee」 ([2017-04-30-1])

・ 「#4990. 動詞を作る -ize/-ise 接尾辞の歴史」 ([2022-12-25-1])

・ 「#4991. -ise か -ize か問題 --- 2つの論点」 ([2022-12-26-1])

・ 「#5042. 『中高生の基礎英語 in English』の連載第24回(最終回)「アルファベット最後の文字 Z のミステリー」」 ([2023-02-15-1])

[ heldio (Voicy) ]

・ 「#171. z と r の発音は意外と似ていた!」 (2021/11/18)

・ 「#540. Z について語ります」 (2022/11/22)

・ 「#541. Z は zee か zed か問題」 (2022/11/23)

[ helsta (stand.fm) ←数日前に始めました ]

・ 「#3. 動詞を作る接尾辞 -ize の裏話」 (2023/10/08)

ただし,いずれ Z に関する新ネタを仕込むことができれば,もちろん Z の汚名返上活動に速やかに戻るつもりです.皆様,これからも Z にはぜひとも優しく接してあげてくださいね.

2023-07-19 Wed

■ #5196. 「ゆる言語学ラジオ」出演第4回 --- 『英単語ターゲット』より英単語語源を語る回 [yurugengogakuradio][notice][youtube][etymology][indo-european][germanic][latin][french][greek]

「ゆる言語学ラジオ」からこちらの「hellog~英語史ブログ」に飛んでこられた皆さん,ぜひ

(1) 本ブログのアクセス・ランキングのトップ500記事,および

(2) note 記事,Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」の人気放送回50選

(3) note 記事,「ゆる言井堀コラボ ー 「ゆる言語学ラジオ」×「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」×「Voicy 英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」」

(4) 「ゆる言語学ラジオ」に関係するこちらの記事群

をご覧ください.

昨日7月18日(火)に,YouTube/Podcast チャンネル「ゆる言語学ラジオ」の最新回がアップされました.これまで3回ゲストとして出演させていただきまして,今回は第4回目となります.「英単語帳の語源を全部知るために,研究者を呼びました【ターゲット1900 with 堀田先生】#247」です.どうぞご覧ください.

最後のほうでも力説しているように,「英語史」は決して狭い学問領域ではなく,英語を学ぶ皆が英語に抱く疑問のほとんどについて,何か言うべきことをもっている頼もしい存在です.ぜひこの機会に英語史の存在を(再)認識していただければ.

過去の3回の出演回も合わせてご視聴ください.

・ 第1弾 「#227. 歴史言語学者が語源について語ったら,喜怒哀楽が爆発した【喜怒哀楽単語1】」(5月6日)

・ 第2弾 「#228. 「英語史の専門家が through の綴りを数えたら515通りあった話【喜怒哀楽単語2】」(5月9日)

・ 第3弾:「#234. 英語史の専門家と辞書を読んだらすべての疑問が一瞬で解決した」(5月30日)

2023-04-29 Sat

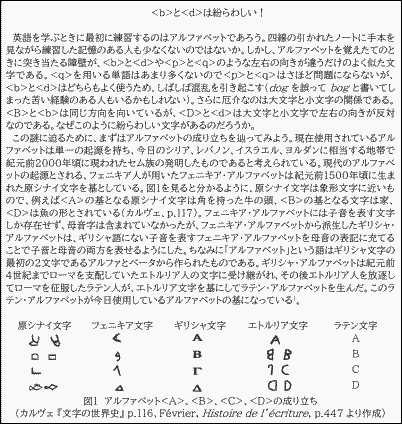

■ #5115. アルファベットの起源と発達についての2つのコンテンツ [voicy][heldio][start_up_hel_2023][hel_contents_50_2023][alphabet][grammatology][etruscan][greek][latin][history][khelf]

4月も終わりに近づき,GW が始まりました.この新年度,khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)では「英語史スタートアップ」企画 (cat:start_up_hel_2023) の一環として「英語史コンテンツ50」を開催中です.コツコツとコンテンツが積み上がり,すでに14本が公開されています.連休中は休止しますが,これからもまだまだ続きます.

今日はこれまでのストックのなかから,アルファベットの歴史に関する大学院生のコンテンツを紹介しましょう.4月19日に公開された「#6. <b> と <d> は紛らわしい!」です.タイトルからは想像できないかもしれませんが,コンテンツの前半はアルファベットの起源と発達,とりわけローマ字の歴史に焦点が当てられています.

このたび,同コンテンツを作成者との対談という形でラジオ化しました.Voicy [「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」より「#698. 先生,アルファベットの歴史を教えてください! --- 寺澤志帆さんとの対談」として配信していますので,そちらを合わせてお聴きください.

本ブログよりアルファベットの歴史に関する記事としては以下を参照ください.

・ 「#423. アルファベットの歴史」 ([2010-06-24-1])

・ 「#490. アルファベットの起源は North Semitic よりも前に遡る?」 ([2010-08-30-1])

・ 「#2888. 文字史におけるフェニキア文字の重要性」 ([2017-03-24-1])

・ 「#1849. アルファベットの系統図」 ([2014-05-20-1])

2023-02-28 Tue

■ #5055. 英語史における言語接触 --- 厳選8点(+3点) [contact][loan_word][borrowing][latin][celtic][old_norse][french][dutch][greek][japanese][link]

英語が歴史を通じて多くの言語と接触 (contact) してきたことは,英語史の基本的な知識である.各接触の痕跡は,歴史の途中で消えてしまったものもあるが,現在まで残っているものも多い.痕跡のなかで注目されやすいのは借用語彙だが,文法,発音,書記など語彙以外の部門でも言語接触のインパクトがあり得ることは念頭に置いておきたい.

英語の言語接触の歴史を短く要約するのは至難の業だが,Schneider (334) による厳選8点(時代順に並べられている)が参考になる.

・ continental contacts with Latin, even before the settlement of the British Isles (i.e., roughly between the second and fourth centuries AD);

・ contact with Celts who were the resident population when the Germanic tribes crossed the channel (in the fifth century and thereafter);

・ the impact of Latin through Christianization (beginning in the late sixth and seventh centuries);

・ contact with Scandinavian raiders and later settlers (between the seventh and tenth centuries);

・ the strong exposure to French as the language of political power after 1066;

・ the massive exposure to written Latin during the Renaissance;

・ influences from other European languages beginning in the Early Modern English period; and

・ the impact of colonial contacts and borrowings.

よく選ばれている8点だと思うが,私としてはここに3点ほど付け加えたい.1つは,伝統的な英語史では大きく取り上げられないものの,中英語期以降に長期にわたって継続したオランダ語との接触である.これについては「#4445. なぜ英語史において低地諸語からの影響が過小評価されてきたのか?」 ([2021-06-28-1]) やその関連記事を参照されたい.

2つ目は,上記ではルネサンス期の言語接触としてラテン語(書き言葉)のみが挙げられているが,古典ギリシア語(書き言葉)も考慮したい.ラテン語ほど目立たないのは事実だが,ルネサンス期以降,ギリシア語の英語へのインパクトは大きい.「#516. 直接のギリシア語借用は15世紀から」 ([2010-09-25-1]) および「#4449. ギリシア語の英語語形成へのインパクト」 ([2021-07-02-1]) を参照.

最後に日本語母語話者としてのひいき目であることを認めつつも,主に19世紀後半以降,英語が日本語と意外と濃厚に接触してきた事実を考慮に入れたい.これについては「#126. 7言語による英語への影響の比較」 ([2009-08-31-1]),「#2165. 20世紀後半の借用語ソース」 ([2015-04-01-1]),「#3872. 英語に借用された主な日本語の借用年代」 ([2019-12-03-1]),「#4140. 英語に借用された日本語の「いつ」と「どのくらい」」 ([2020-08-27-1]) を参照.

Schneider の8点に,この3点を加え,私家版の厳選11点の完成!

・ Schneider, Edgar W. "Perspectives on Language Contact." Chapter 13 of English Historical Linguistics: Approaches and Perspectives. Ed. Laurel J. Brinton. Cambridge: CUP, 332--59.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow