2016-03-04 Fri

■ #2503. 中英語文学 [me][literature][chaucer][norman_conquest][romance][reestablishment_of_english][wycliffe][bible][langland][sggk][pearl][lydgate]

中英語期の英語で書かれた文学について,主として Baugh and Cable の110節 "Middle English Literature" (149--51) に依拠し,英語史に関連する範囲内で大雑把に概括したい.

中英語が社会言語的にたどった運命と,中英語文学は密接にリンクしている.ノルマン征服により,フランス語を話す上流階級の文学的嗜好は,当然ながらフランス語で書かれた書物へ向かっており,英語で書かれたものにパトロンが付く可能性は皆無だった.しかし,英語で物する者がいたことは確かであり,彼らは別の目的で書くという行為を行なっていたのである.それは,英語しか解さない一般庶民にキリスト教を布教しようという情熱に駆られた宗教者たちだった.したがって,1150--1250年に相当する初期中英語期に英語で書かれたものは,ほぼすべてが宗教的・説諭的な文学である.Ancrene Riwle や Ormulum (c. 1200) のような聖書の福音書の解釈本や,古英語に由来する聖者伝や説教集の焼き直しが,この時代の英語文学だった.例外的に Layamon's Brut (c. 1200) や The Owl and the Nightingale (c. 1195) のような非宗教的な文学も出たが,例外と言ってよい.この時代は,原則として "Period of Religious Record" と呼べるだろう.

次の100年間は,フランス語に対して英語が徐々に復権の兆しを示し初め,英語がより広く文学として表わされるようになってきた.フランス語で書かれた文学が翻訳されるなどして,14世紀にかけて英語の文学は勢いを増してきた.具体的には,非宗教的なロマンス (romance) というジャンルが英語という媒体に乗せられるようになった.1250--1350年の英語文学の時代は,"Period of Religious and Secular Literature" と呼ぶことができるだろう.

14世紀の後半までには,イングランドにおいて英語はほぼ完全な復活 (reestablishment_of_english) を果たし,この時期は中世英語文学史における華を体現することになる.Canterbury Tales や Troilus and Criseyde といった大著を残した Geoffrey Chaucer (1340--1400) を初めとして,社会的寓話 Piers Plowman (1362--87) を著わした William Langland,聖書翻訳で物議をかもした John Wycliffe (d. 1384),Sir Gawain and the Green Knight ほか3つの寓意的・宗教的な珠玉の詩を残した詩人が現われ,まさに "Period of Great Individual Writers" と言ってよいだろう.

15世紀は,Chaucer などの偉大な先人の影響下で,英語文学史上,影が薄い時期となっており,"Imitative Period",あるいは初期近代の Shakespeare までのつなぎの時期という意味で "Transition Period" などと呼ばれている.文学史的には相対的に過小評価されてきたきらいがあるが,Lydgate, Hoccleve, Skelton, Hawes などの傑物が現われている.スコットランドでも,Henryson, Dunbar, Gawin Douglas, Lindsay などが著しい活躍をなした.世紀末には Malory や Caxton が現われるが,この15世紀の語学や文学はもっと真剣に扱われてしかるべきである.この最後の時代の語学・文学的事情については,「#292. aureate diction」 ([2010-02-13-1]) および「#1719. Scotland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-10-1]) も要参照.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2015-10-01 Thu

■ #2348. 英語史における code-switching 研究 [code-switching][me][emode][bilingualism][contact][latin][french][literature][borrowing][genre][historical_pragmatics][discourse_analysis]

本ブログでは code-switching (CS) に関していくつかの記事を書いてきた.とりわけ英語史の視点からは,「#1470. macaronic lyric」 ([2013-05-06-1]),「#1625. 中英語期の書き言葉における code-switching」 ([2013-10-08-1]),「#1941. macaronic code-switching としての語源的綴字?」 ([2014-08-20-1]),「#2271. 後期中英語の macaronic な会計文書」 ([2015-07-16-1]) で論じてきた.現代語の CS に関わる研究の発展に後押しされる形で,また歴史語用論 (historical_pragmatics) の流行にも支えられる形で,歴史的資料における CS の研究も少しずつ伸びてきているようであり,英語史においてもいくつか論文集が出されるようになった.

しかし,歴史英語における CS の実態は,まだまだ解明されていないことが多い.そもそも,CS が観察される歴史テキストはどの程度残っているのだろうか.Schendl は,中英語から初期近代英語にかけて,複数言語が混在するテキストは決して少なくないと述べている.

There is a considerable number of mixed-language texts from the ME and the EModE periods, many of which show CS in mid-sentence. The phenomenon occurs across genres and text types, both literary and non-literary, verse and prose; and the languages involved mirror the above-mentioned multilingual situation. In most cases Latin as the 'High' language is one of the languages, with one or both of the vernaculars English and French as the second partner, though switching between the two vernaculars is also attested. (79)

CS in written texts was clearly not an exception but a widespread specific mode of discourse over much of the attested history of English. It occurs across domains, genres and text types --- business, religious, legal and scientific texts, as well as literary ones. (92)

ジャンルを問わず,様々なテキストに CS が見られるようだ.文学テキストとしては,具体的には "(i) sermons; (ii) other religious prose texts; (iii) letters; (iv) business accounts; (v) legal texts; (vi) medical texts" が挙げられており,非文学テキストとしては "(i) mixed or 'macaronic' poems; (ii) longer verse pieces; (iii) drama; (iv) various prose texts" などがあるとされる (Schendl 80) .

英語史あるいは歴史言語学において CS (を含むテキスト)を研究する意義は少なくとも3点ある.1つは,過去の2言語使用と言語接触の状況の解明に資する点だ.2つめは,CS と借用の境目を巡る問題に関係する.語彙借用の多い英語の歴史にとって,借用の過程を明らかにすることは,理論的にも実際的にも極めて重要である (see 「#1661. 借用と code-switching の狭間」 ([2013-11-13-1]),「#1985. 借用と接触による干渉の狭間」 ([2014-10-03-1]),「#1988. 借用語研究の to-do list (2)」 ([2014-10-06-1]),「#2009. 言語学における接触,干渉,2言語使用,借用」 ([2014-10-27-1])) .3つめに,共時的な CS 研究に通時的な次元を与えることにより,理論を深化させることである.

・ Schendl, Herbert. "Linguistic Aspects of Code-Switching in Medieval English Texts." Multilingualism in Later Medieval Britain. Ed. D. A. Trotter. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000. 77--92.

2015-09-28 Mon

■ #2345. 古英語の diglossia と中英語の triglossia [diglossia][sociolinguistics][bilingualism][oe][me][latin][french]

社会言語学の話題として取り上げられる diglossia は,しばしば英語史にも適用されてきた.これについては,本ブログでも以下の記事などで取り上げてきた.

・ 「#661. 12世紀後期イングランド人の話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-02-17-1])

・ 「#1203. 中世イングランドにおける英仏語の使い分けの社会化」 ([2012-08-12-1])

・ 「#1486. diglossia を破った Chaucer」 ([2013-05-22-1])

・ 「#1488. -glossia のダイナミズム」 ([2013-05-24-1])

・ 「#1489. Ferguson の diglossia 論文と中世イングランドの triglossia」 ([2013-05-25-1])

・ 「#2148. 中英語期の diglossia 描写と bilingualism 擁護」 ([2015-03-15-1])

・ 「#2328. 中英語の多言語使用」 ([2015-09-11-1])

単純化して述べれば,古英語は diglossia の時代,中英語は triglossia の時代である.アングロサクソン時代の初期には,ラテン語の役割はいまだ大きくなかったが,キリスト教が根付いてゆくにつれ,その社会的な重要性は増し,アングロサクソン社会は diglossia となった.Nevalainen and Tieken-Boon van Ostade (272) によれば,

. . . Anglo-Saxon England became a diglossic society, in that one language came to be used in one set of circumstances, i.e. Latin as the language of religion, scholarship and education, while another language, English, was used in an entirely different set of circumstances, namely in all those contexts in which Latin was not used. In other words, Latin became the High language and English, in its many different dialects, the Low language.

しかし,重要なのは,英語は当時のヨーロッパでは例外的に,法律や文学という典型的に High variety の使用がふさわしいとされる分野においても用いられたことである.古英語の diglossia は,この点でやや変則的である.

中英語期に入ると,イングランド社会における言語使用は複雑化する.再び Nevalainen and Tieken-Boon van Ostade (272--73) から引用する.

This diglossic situation was complicated by the coming of the Normans in 1066, when the High functions of the English language which had evolved were suddenly taken over by French. Because the situation as regards Latin did not change --- Latin continued to be primarily the language of religion, scholarship and education --- we now have what might be referred to as a triglossic situation, with English once more reduced to a Low language, and the High functions of the language shared by Latin and French. At the same time, a social distinction was introduced within the spoken medium, in that the Low language was used by the common people while one of the High languages, French, became the language of the aristocracy. The use of the other High language, Latin, at first remained strictly defined as the medium of the church, though eventually it would be adopted for administrative purposes as well. . . . [T]he functional division of the three languages in use in England after the Norman Conquest neatly corresponds to the traditional medieval division of society into the three estates: those who normally fought used French, those who worked, English, and those who prayed, Latin.

このあと後期中英語にかけてフランス語の使用が減り,近代英語期中にはラテン語の使用分野もずっと限られるようになり,結果としてイングランドは monoglossia 社会へ移行した.以降,英語はむしろ世界各地の diglossia や triglossia に, High variety として関与していくのである.

・ Nevalainen, Terttu and Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade. "Standardisation." Chapter 5 of A History of the English Language. Ed. Richard Hogg and David Denison. Cambridge: CUP, 2006. 271--311.

2015-09-12 Sat

■ #2329. 中英語の借用元言語 [borrowing][loan_word][me][lexicology][contact][latin][french][greek][italian][spanish][portuguese][welsh][cornish][dutch][german][bilingualism]

中英語の語彙借用といえば,まずフランス語が思い浮かび (「#1210. 中英語のフランス借用語の一覧」 ([2012-08-19-1])),次にラテン語が挙がる (「#120. 意外と多かった中英語期のラテン借用語」 ([2009-08-25-1]), 「#1211. 中英語のラテン借用語の一覧」 ([2012-08-20-1])) .その次に低地ゲルマン語,古ノルド語などの言語名が挙げられるが,フランス語,ラテン語の陰でそれほど著しくは感じられない.

しかし,実際のところ,中英語は上記以外の多くの言語とも接触していた.確かにその他の言語からの借用語の数は多くはなかったし,ほとんどが直接ではなく,主としてフランス語を経由して間接的に入ってきた借用語である.しかし,多言語使用 (multilingualism) という用語を広い意味で取れば,中英語イングランド社会は確かに多言語使用社会だったといえるのである.中英語における借用元言語を一覧すると,次のようになる (Crespo (28) の表を再掲) .

| LANGUAGES | Direct Introduction | Indirect Introduction |

| Latin | --- | |

| French | --- | |

| Scandinavian | --- | |

| Low German | --- | |

| High German | --- | |

| Italian | through French | |

| Spanish | through French | |

| Irish | --- | |

| Scottish Gaelic | --- | |

| Welsh | --- | |

| Cornish | --- | |

| Other Celtic languages in Europe | through French | |

| Portuguese | through French | |

| Arabic | through French and Spanish | |

| Persian | through French, Greek and Latin | |

| Turkish | through French | |

| Hebrew | through French and Latin | |

| Greek | through French by way of Latin |

「#392. antidisestablishmentarianism にみる英語のロマンス語化」 ([2010-05-24-1]) で引用した通り,"French acted as the Trojan horse of Latinity in English" という謂いは事実だが,フランス語は中英語期には,ラテン語のみならず,もっとずっと多くの言語からの借用の「窓口」として機能してきたのである.

関連して,「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1]),「#516. 直接のギリシア語借用は15世紀から」 ([2010-09-25-1]),「#2164. 英語史であまり目立たないドイツ語からの借用」 ([2015-03-31-1]) も参照.

・ Crespo, Begoña. "Historical Background of Multilingualism and Its Impact." Multilingualism in Later Medieval Britain. Ed. D. A. Trotter. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000. 23--35.

2015-09-11 Fri

■ #2328. 中英語の多言語使用 [me][bilingualism][french][latin][contact][sociolinguistics][writing][diglossia][register]

中英語における,英語,フランス語,ラテン語の3言語使用を巡る社会的・言語的状況については,これまでの記事でも多く取り上げてきた.例えば,以下を参照.

・ 「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1])

・ 「#661. 12世紀後期イングランド人の話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-02-17-1])

・ 「#1488. -glossia のダイナミズム」 ([2013-05-24-1])

・ 「#1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造」 ([2014-09-08-1])

・ 「#2025. イングランドは常に多言語国だった」 ([2014-11-12-1])

Crespo (24) は,中英語期における各言語の社会的な位置づけ,具体的には使用域,使用媒体,地位を,すごぶる図式ではあるが,以下のようにまとめている.

| LANGUAGE | Register | Medium | Status |

| Latin | Formal-Official | Written | High |

| French | Formal-Official | Written/Spoken | High |

| English | Informal-Colloquial | Spoken | Low |

Crespo (25) はまた,3言語使用 (trilingualism) が時間とともに2言語使用 (bilingualism) へ,そして最終的に1言語使用 (monolingualism) へと解消されていく段階を,次のように図式的に示している.

| ENGLAND | Languages | Linguistic situation |

| Early Middle Ages | Latin--French--English | TRILINGUAL |

| 14th--15th centuries | French--English | BILINGUAL |

| 15th--16th c. onwards | English | MONOLINGUAL |

実際には,3言語使用や2言語使用を実践していた個人の数は全体から見れば限られていたことに注意すべきである.Crespo (25) も2つ目の表について述べている通り,"The initial trilingual situation (amongst at least certain groups) developed into oral bilingualism (though not universal) which in turn gradually resulted in vernacular monolingualism" ということである.だが,いずれの表も,中英語期のマクロ社会言語学的状況の一面をうまく表現している図ではある.

・ Crespo, Begoña. "Historical Background of Multilingualism and Its Impact." Multilingualism in Later Medieval Britain. Ed. D. A. Trotter. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000. 23--35.

2015-09-06 Sun

■ #2323 中英語の方言ごとの主要作品 [me][literature][me_dialect][dialect]

古英語の主要作品とその方言分布・年代について「#1433. 10世紀以前の古英語テキストの分布」 ([2013-03-30-1]) で一覧した.中英語の作品については,「#1044. 中英語作品,Chaucer,Shakespeare,聖書の略記一覧」 ([2012-03-06-1]) で名前の略号とともに列挙したのみで,方言分布などを示していなかった.

今回は,中英語の主要作品について,宇賀治 (57--59) による一覧を掲げよう.制作年は原則として Kurath et al. (1954) によるものだが,OED を参照したものもあるとのこと.中英語方言文学のおともに.

| 1. 南東方言 | |

|---|---|

| c1275 | Kentish Sermons |

| 1340 | Dan Michel's Ayenbite of Inwyt (= D.M.'s Remorse of conscience) |

| 2. 南西方言 | |

| ?a1200 | Ancrene Wisse (Corp-C) (= The English Text of the Ancrene Riwle (= Nuns' Rule)) |

| ?a1200 | Laȝamon's Brute, or Chronicle of Britain |

| ?c1200 | Sawles Warde (= Soul's Guardian) |

| a1225--a1300 | Poema Morale (= Moral Ode) |

| ?c1225 | King Horn |

| c1250 | Floriz and Blauncheflur |

| c1250 | The Owl and the Nightingale |

| a1376--?a1387 | William Langland, Piers Plowman A-, B-, C-Versions |

| a1387 | John de Trevisa's Translation of Higden's Polychronicon (= H.'s History of many Ages) |

| 3. 東中部方言 | |

| a1121--1160 | The Peterborough Chronicle |

| ?c1200 | The Ormulum |

| a1250 | Bestiary |

| c1250 | The Story of Genesis and Exodus |

| 1258 | Proclamation of Henry III |

| c1300 | Havelock the Dane |

| 1382; 1388 | Wycliffite Bible |

| c1375--a1400 | Geoffrey Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales |

| a1393 | John Gower, Confessio Amantis |

| c1400 | Mandeville's Travels (Tit) |

| 1425--1520 | Paston Letters and Papers |

| a1438 | The Book of Margery Kempe |

| 4. 西中部方言 | |

| ?c1380 | Patience |

| ?c1380 | Pearl |

| ?c1390 | Sir Gawain and the Green Knight |

| 5. 北部方言 | |

| a1325 | Cursor Mundi (= The Runner of the World) |

| ?c1343--?a1349 | Richard Rolle, Prose and Verse |

| ?a1400 | Morte Arthure or The Death of Arthur |

・ 宇賀治 正朋 『英語史』 開拓社,2000年.

2015-07-16 Thu

■ #2271. 後期中英語の macaronic な会計文書 [code-switching][me][bilingualism][latin][register][pragmatics]

中英語期の英羅仏の混在型文書,いわゆる macaronic writing については,「#1470. macaronic lyric」 ([2013-05-06-1]),「#1625. 中英語期の書き言葉における code-switching」 ([2013-10-08-1]) で話題にし,それを応用した議論として初期近代英語期の語源的綴字について「#1941. macaronic code-switching としての語源的綴字?」 ([2014-08-20-1]) の記事を書いた.文書のなかで言語を切り替える動機づけは,ランダムなのか,あるいは社会的・談話語用的な意味合いがあるのか議論してきた.

この分野で活発に研究している Wright (768--69) は,中英語の文書,とりわけ彼女の調査したロンドンの会計文書に現われる英羅語の code-switching には,社会的・談話語用的な動機づけがあったのではないかと論じている

I am led to suggest that macaronic writing should not be taken simply as a reflection of growing ignorance of Latin, nor be explained merely as some kind of partial bilingualism into which users naturally fell because they had been exposed to Latin in their profession. Rather I conclude that macaronic writing formed a deliberate, formal register; with systemic rules for the formation of words and sentences, which underwent temporal change as does any language structure. At this early stage of investigation, I venture to suggest that macaronic writing may be associable with a specific social group (in this case, accountants) whose professional status was defined at least in part by a facility in both languages, and whose emerging position may itself have been marked by the hybrid usage of macaronic writing as a formal register in professional contexts.

会計文書における英羅語の混在がランダムな code-switching ではないということ,両言語をまともに解さない半言語使用 (semilingualism) に基づくものではないということについて,Wright (769fn) はピジン語と対比しながら次のように述べている.

. . . pidgins develop due to the inability of the interlocutors to understand each other's language, whereas macaronic writing appears to show the ability of the composer to understand both Latin and English. Pidgins depend upon the spoken form as a primary medium for their development, whereas there is no evidence that material so stylistically sophisticated as macaronic sermons or administrative records were first transmitted as speech.

macaronic writing は商用文書のほかに聖歌や説教にも見られるが,いずれの使用域においても何らかの社会的・語用的な動機づけがあるのではないかという議論である.商用文書に関しては,実用を目的とする上で英羅語混在が有利な何らかの理由があったのかもしれないし,聖歌や説教では使用言語によって,聞き手の宗教心に訴えかける効果が異なっていたということなのかもしれない.いずれにせよ,code-switching に動機づけがあったとして,それが具体的に何だったのかが問題である.

・ Wright, Laura. "Macaronic Writing in a London Archive, 1380--1480." History of Englishes: New Methods and Interpretations in Historical Linguistics. Ed. Matti Rissanen, Ossi Ihalainen, Terttu Nevalainen, and Irma Taavitsainen. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1992. 762--71.

2015-05-10 Sun

■ #2204. d と th の交替・変化 [consonant][verners_law][phonetics][me]

標記の話題は,「#481. father に起こった摩擦音化」 ([2010-08-21-1]) で部分的に取り上げた.英語史では,ð > d あるいはその逆の d > th を経た語が散見されるが,神山 (157) は関連する22語を収集して示している.有益なリストなので,以下に記しておこう(先の記事で挙げた例も参照).

| OE ð [ð] | ModE. d [d] | OE d [d] | ModE. th [ð] |

| byrðen | burden | fæder | father |

| cūðe | could | gad(e)rian | gather |

| Cūð(wi)nes dūn | Cuddesdon | ġeard | garth[θ] (? yard) |

| fiðele | fiddle | hider | hither |

| ġeforðian | afford | hwider | whither |

| morðor | murder | mōdor | mother |

| nǣðl | needle | sweard | swarth [θ] (? sward) |

| rōðor | rudder | ME teder | tether |

| spīðra | spider | tōgæd(e)re | together |

| staðol | staddle | þider | thither |

| swæðel | swaddle | weder | weather |

Skeat による従来の説によれば,このような d と ð の間の揺れは,かつての verners_law の結果としてもたらされた共時的混乱であるとされた.しかし,神山は,上記の変化が中英語以降に生じた現象であることから,その千年以上前に生じた Verner's Law (とその余波)が関与していると考えることには無理があるし,もし Verner's Law の潜伏的な関与があったとするならば, (PIE *t >) d/ð のみならず,(PIE *p >) [v]/[b], (PIE *k >) [x]/[ɣ], (PIE *s >) [z]/[r] にも揺れが見られるはずだが実際には見られないことを指摘して,Skeat 説は受け入れることができないとしている.神山は,中英語期の d と ð を巡る一連の状況は,むしろ特定の音環境における音変化として説明できると論じる.特定の音環境のもとでの音変化であるという考え方は,Jespersen や Jordan によって唱えられてはいたが,神山 (161) は彼らの規定した音環境が精確さを欠いているとし,その改訂版を提示する形で論文を結んでいる.具体的には,以下の通り.

・ 12世紀頃,鳴音が隣接する場合に [ð] は [d] に転じる傾向を示した

・ 15世紀頃,成節の流音と鼻音に先行する [d] は [ð] に転じる傾向を示した

上記のように音環境を規定すると,ほとんどすべての関与する例がうまく説明できるという.この2つの過程は時代も異なっており,互いに関与しない独立した音変化である,と.

・ 神山 孝夫 「OE byrðen "burden" vs. fæder "father" ―英語史に散発的に見られる [d] と [ð] の交替について―」 『言葉のしんそう(深層・真相) ―大庭幸男教授退職記念論文集―』 英宝社,2015年,155--66頁.

2015-03-14 Sat

■ #2147. 中英語期のフランス借用語批判 [purism][loan_word][french][inkhorn_term][me][lexicology]

16世紀には,ラテン借用語をはじめとしてロマンス諸語などからの借用語がおびただしく英語へ流入した(「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1]) や「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1]) を参照).日本語でも明治以降,大量の漢語が作られ,昭和以降は無数のカタカナ語が流入した(「#1617. 日本語における外来語の氾濫」 ([2013-09-30-1]) 及び「#1630. インク壺語,カタカナ語,チンプン漢語」 ([2013-10-13-1]) を参照).これらの時代の各々において,純粋主義 (purism) の立場からの借用語批判が聞かれた.借用語をむやみやたらに使用するのは控えて,本来語をもっと多く使うべし,という議論である.

英語史においてあまり聞かないのは,中英語期に怒濤のように押し寄せたフランス借用語に対する批判である.「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1]) で見たとおり,英語はノルマン・コンクェスト後の数世紀間で,歴史上初めて数千語という規模での大量語彙借用を経験してきたが,そのフランス借用語への批判はなかったのだろうか.

確かにルネサンス期のインク壺語批判ほどは目立たないが,中英語におけるフランス借用語批判がまったくなかったわけではない.Ranulph Higden (c. 1280--1364) によるラテン語の Polychronicon を1387年に英訳した John of Trevisa (1326--1402) は,ある一節で,古ノルド語とともにフランス語からの借用語の無分別な使用について苦情を呈している.Crystal (186) からの引用を再現しよう.

by commyxstion and mellyng, furst wiþ Danes and afterward wiþ Normans, in menye þe contray longage ys apeyred, and som vseþ strange wlaffyng, chyteryng, harryng, and garryng grisbittyng.

同様に,Richard Rolle of Hampole (1290?--1349.) による Psalter (a1350) でも,"seke no strange Inglis" (見知らぬ英語は使わない)とフランス借用語に対して暗に不快感を示しているし,15世紀に Polychronicon を英訳した Osbern Bokenham (1393?--1447?) も,フランス語が英語を野蛮にしたと非難している (Crystal 186) .しかし,彼らとて,自らの著書のなかで,洗練されたフランス借用語を用いていたことはいうまでもない.

このように中英語期のフランス借用語への純粋主義的な非難はいくつか確認されるが,後世の激しいインク壺語批判に比べれば単発的であり,特に大きな潮流を形成しなかったようだ.英語自体がまだ一国の言語としておぼつかない地位にあって,英語の本来語への思慕や借用語の嫌悪という純粋主義的な態度が世の注目を浴びるには,まだ時代が早かったものと思われる.それでも,この中英語期の早熟な純粋主義的批判は,後世の苛烈な批判の前段階として,確かに英語史上に位置づけられるものではあるだろう.

・ Crystal, David. The Stories of English. London: Penguin, 2005.

2015-03-09 Mon

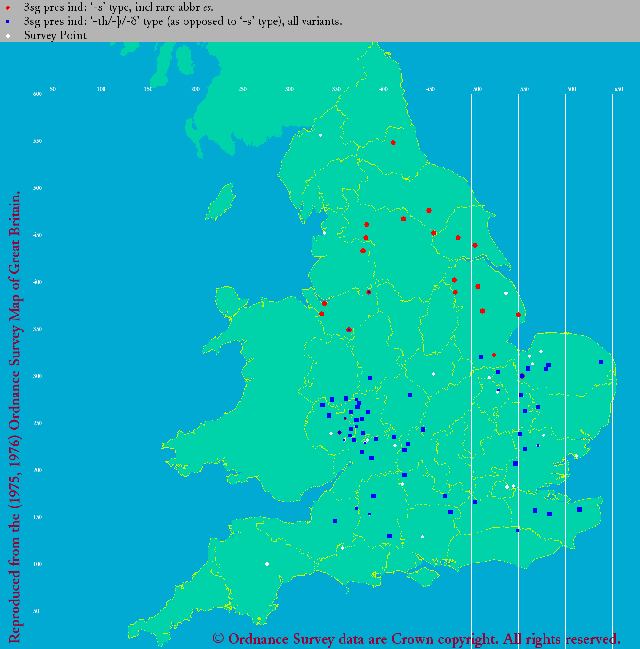

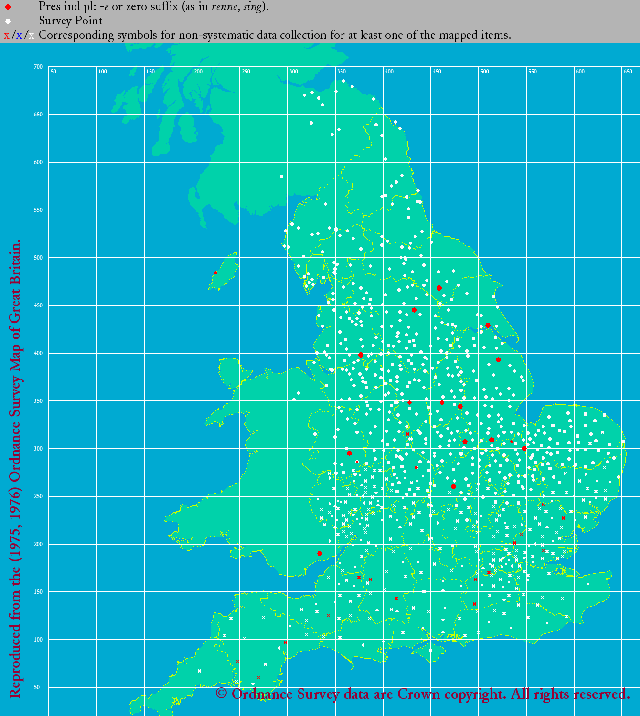

■ #2142. 中英語における3単現および複現の語尾の方言分布 [map][laeme][lalme][me_dialect][me][3sp][3pp][verb][conjugation][nptr]

標題の問いに手っ取り早く答えるには,次の表で事足りる(Görlach (68) による表の一部より).

| South | Midland | North | ||

| Present Indicative | 3sg. | -(e)þ | -(e)þ | -(e)s |

| pl. | -(e)þ | -(e)n | -(e)s | |

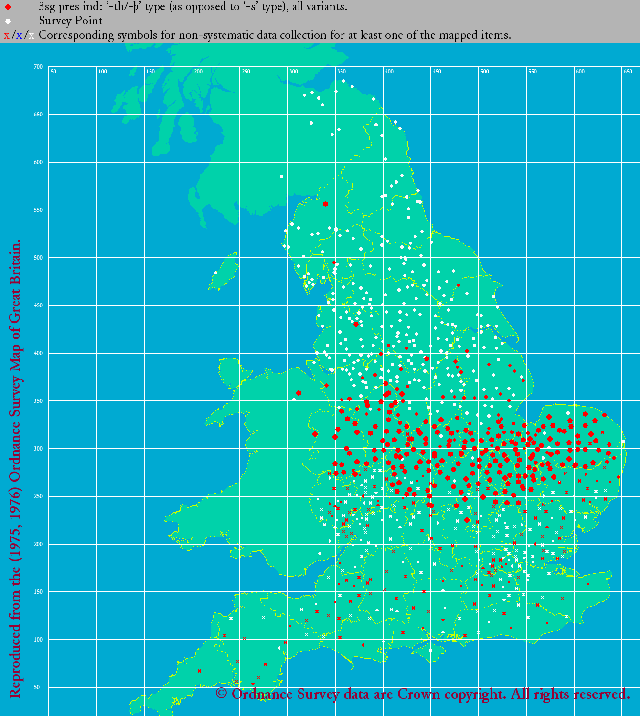

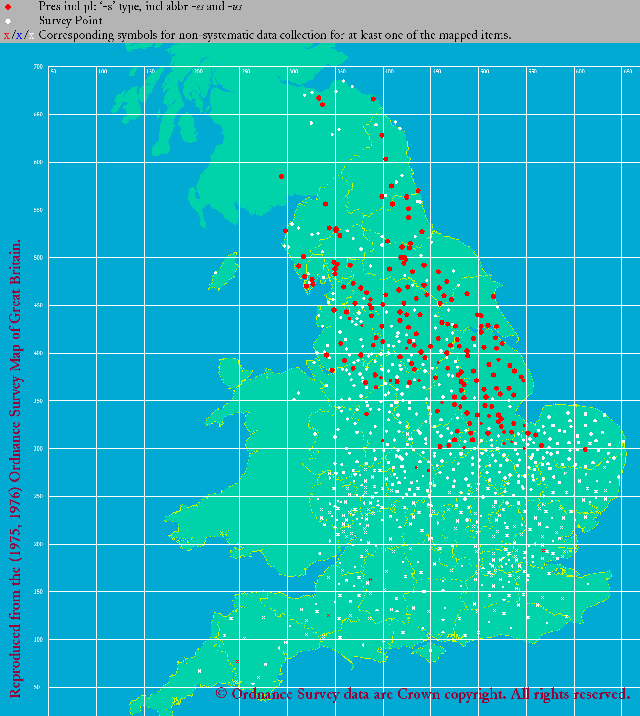

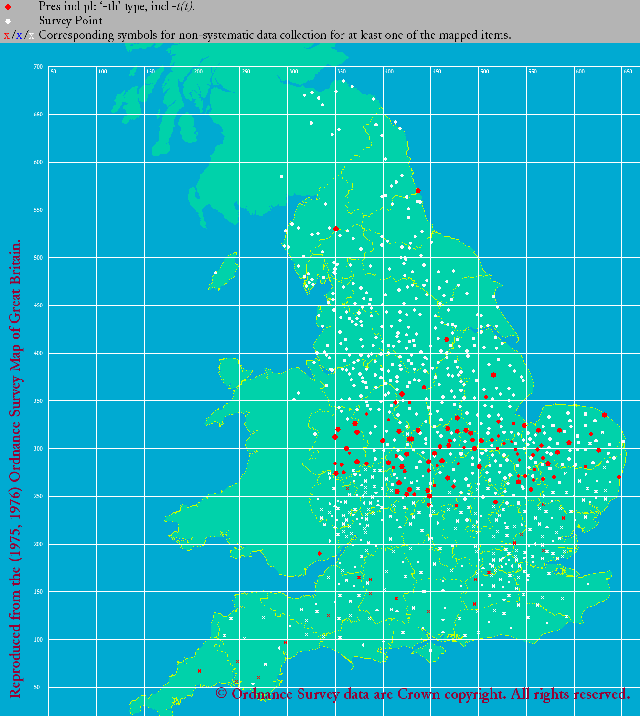

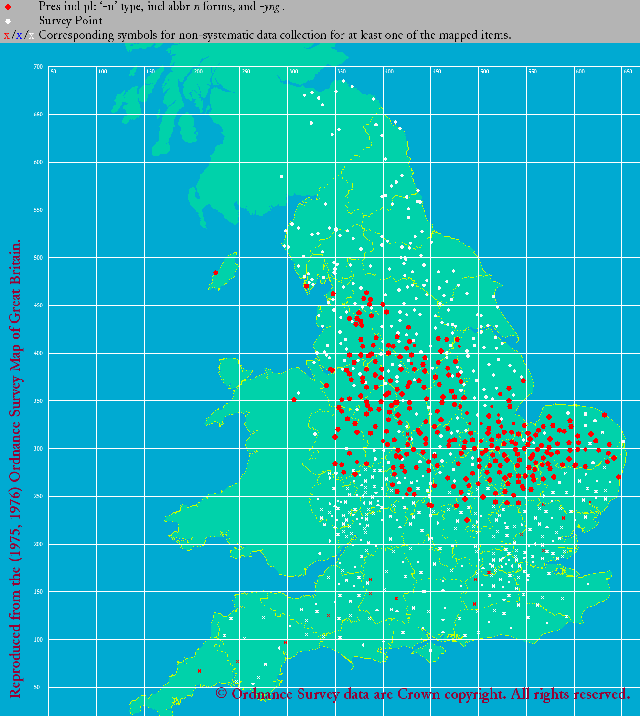

これを地図上に示すと「#790. 中英語方言における動詞屈折語尾の分布」 ([2011-06-26-1]) の通りとなるが,より詳しい分布を得たいときには LAEME (初期中英語)と eLALME (後期中英語)を参照するのが便利である (cf. 「#1622. eLALME」 ([2013-10-05-1])) .以下では,両アトラスより得られた地図の画像を貼り付けよう(クリックするとより大きく綺麗な画像が得られる).まずは,1150--1325年をカバーする LAEME より,3単現(左)と複現(右)の語尾の分布をそれぞれ示す.

|

|

| LAEME: 3sp 's' and 'th' | LAEME: pp 's', 'th', 'n', 'e', and zero |

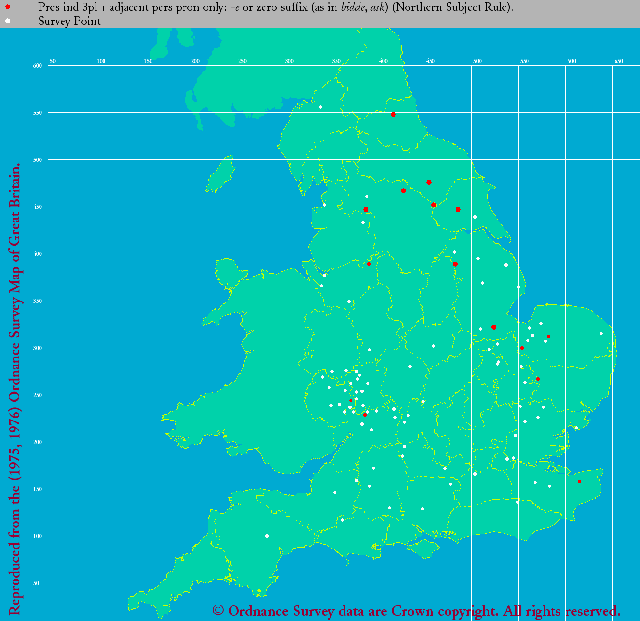

両地図で北部に集まる赤丸が -s を,南部に集まる青四角が -th を表す.右の複現の語尾では東中部その他に黒三角が散在しているが,これは -n 語尾を表す.次に,複数代名詞と接する動詞の現在形が -e またはゼロの語尾をとる "Northern Present Tense Rule" (NPTR; cf. 「#689. Northern Personal Pronoun Rule と英文法におけるケルト語の影響」 ([2011-03-17-1]),nptr) の分布図を見よう.

|

| LAEME: NPTR pp 'e' and zero |

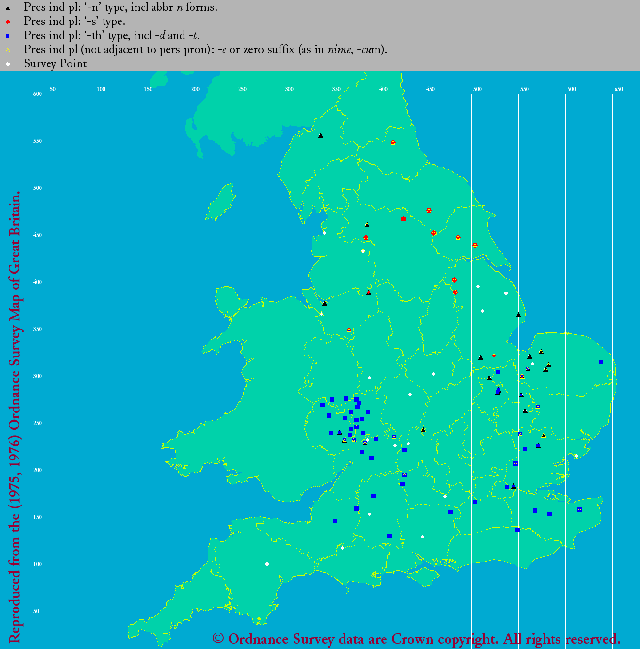

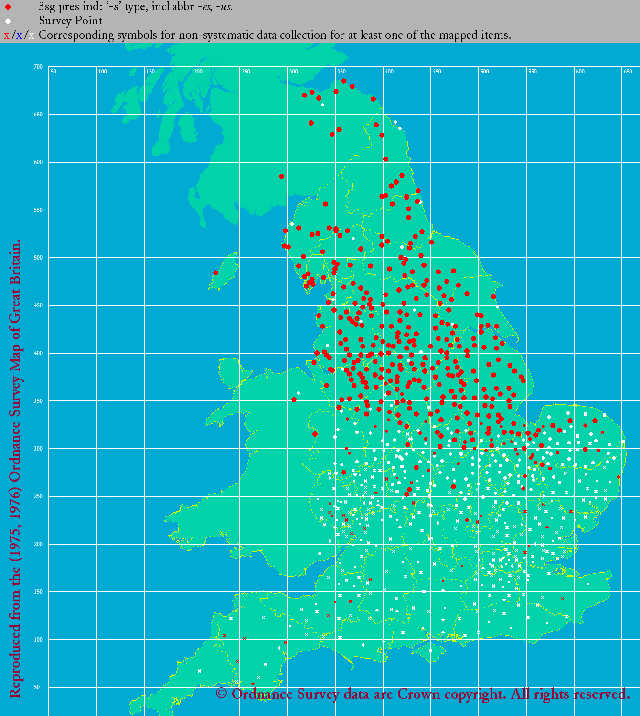

では次に後期中英語の分布に移る.eLALME では,語尾の種類ごとに別々の地図を作成した.まずは3単現から.

|

|

| eLALME: 3sp 's' | eLALME: 3sp 'th' |

前時代の分布をよく受け継いでおり,左図の通り -s が北部に,右図の通り -th が中部以南に分布しているのがわかる.複現については,-s, -th, -n, -e (or zero) の4種類について各々の地図を見てみよう.

|

|

| eLALME: pp 's' | eLALME: pp 'th' |

|

|

| eLALME: pp 'n' | eLALME: pp 'e' or zero |

こちらも前時代の分布をよく受け継いでおり,北部で -s (左上図),中部以南で -th (右上図)が優勢だが,中部で -n (左下図)が前時代よりも著しく拡張していることが見て取れる.全体的に,初期中英語と後期中英語の分布間で量的な差は見られるが,質的には大きな変化はないといってよいだろう. *

・ Görlach, Manfred. The Linguistic History of English. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2014-04-22 Tue

■ #1821. フランス語の復権と英語の復権 [french][latin][reestablishment_of_english][me][history][hfl]

中英語後期の,フランス語に対する英語の復権について,本ブログでは reestablishment_of_english の各記事で話題にしてきた.同じ頃,お隣のフランスでは,ラテン語に対するフランス語の復権が起こっていた.つまり,中世末期,イングランドとフランスの両国(のみならず実際にはヨーロッパ各国)で,相手にする言語こそ異なれ,大衆の言語 (vernacular) が台頭してきたのである.

中世後期のフランスで,フランス語がいかに市民権を得てきたか,行政・司法に用いられる言語という観点から概説しよう.中世フランスでは,行政・司法の言語としてラテン語が一般的であったことは間違いないが,13世紀中からフランス語の使用も始まっていた.特に Charles IV の治世 (1322--28) において行政・司法におけるフランス語の使用は,安定したものとはならなかったものの,進展した.その後14世紀末からは,フランス王国のアイデンティティと結びついた国語として,フランス語の存在感が確かに認められるようになってゆく.そして,ついに1539年8月15日,行政・司法におけるフランス語に,決定的なお墨付きが与えられることとなった.フランス語史上に名高いヴィレ・コトレの勅令 (l'ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts) である.「#653. 中英語におけるフランス借用語とラテン借用語の区別」 ([2011-02-09-1]) で触れたように,それまで法曹界はラテン語とフランス語の2言語制で回っていたが,フランソワ1世 (Francis I; 1494--1547) が行政・司法でのラテン語使用を廃止したのである.Perret (47) より,勅令の関係する箇所を引こう.

L'ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts (1539) Articles 110 et 111

«Et afain qu'il n'y ait cause de douter sur l'intelligence desdits arrests, nous voulons et ordonnons qu'ils soient faits et escrits si clairement, qu'il n'y ait ne puisse avoir aucune ambiguïté ou incertitude, ne lieu à demander interprétation.

Et pour ce que de telles choses sont souvent advenues sur l'intelligence des mots latins contenus esdits arrests, ensemble toutes autres procédures, [...] soient prononcez, enregistrez et delivrez aux parties en langaige maternel françois et non autrement.»

この勅令は,ラテン語を扱えない官吏の業務負担を減らすためという実際的な目的もあったが,フランス語をフランスの国語として制定するという意味合いがあった.その後の歴史において,フランスは他言語や非標準方言を退け,標準フランス語の普及と拡大に突き進んでゆくが,その最初の決定的な一撃が1539年に与えられたことになる.実際に,17世紀中にこの勅令の内容は拡大し,フランス革命後も堅持されたことはいうまでもない.

一方,イングランドにおける英語の復権は,「#131. 英語の復権」 ([2009-09-05-1]) や「#706. 14世紀,英語の復権は徐ろに」 ([2011-04-03-1]) で示したように,あくまで徐々に進んでいった.確かに,「#324. 議会と法廷で英語使用が公認された年」 ([2010-03-17-1]) である1362年のような,英語の復権を象徴する契機はあるにはあるが,ヴィレ・コトレの勅令のような1つの決定的な出来事に相当するものはない.

近代ではイングランド,フランスともに標準語を巡る問題,規範の議論が持ち上がったが,諸問題への対処法や言語政策は両国間で大きく異なっていた.その差異の起源は,すでに中世後期における土着語の復権の仕方そのものにあったように思われる.

・ Perret, Michèle. Introduction à l'histoire de la langue française. 3rd ed. Paris: Colin, 2008.

2014-03-05 Wed

■ #1773. ich, everich, -lich から語尾の ch が消えた時期 [me][corpus][hc][phonetics][personal_pronoun][consonant][-ly]

「#1198. ic → I」 ([2012-08-07-1]) の記事で,古英語から中英語にかけて用いられた1人称単数代名詞の主格 ich が,語末の子音を消失させて近代英語の I へと発展した経緯について論じた.そこでは,純粋な音韻変化というよりは,機能語に見られる強形と弱形の競合が関わっているのではないかと提案した.

しかし,音韻的な要因が皆無というわけではなさそうだ.Schlüter によれば,後続する語頭の音に種類によって,従来の長形 ich か刷新的な短形 i かのいずれかが選ばれやすいという事実が,確かにある.

Schlüter は,Helsinki Corpus を用いて中英語期内で時代ごとに,そして後続音の種類別に,ich, everich, -lich それぞれの変異形の分布を調査した.以下に,Schlüter (224, 227, 226) に掲載されている,各々の分布表を示そう.

| I | 1150--1250 (ME I) | 1250--1350 (ME II) | 1350--1420 (ME III) | 1420--1500 (ME IV) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tokens | % | tokens | % | tokens | % | tokens | % | ||

| before V | ich | 169 | 100 | 121 | 95 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| I | 0 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 135 | 97 | 253 | 100 | |

| before <h> | ich | 171 | 100 | 105 | 97 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| I | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 156 | 98 | 316 | 100 | |

| before C | ich | 513 | 94 | 363 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I | 33 | 6 | 494 | 58 | 1106 | 100 | 2043 | 100 | |

| EVERY | 1150--1250 (ME I) | 1250--1350 (ME II) | 1350--1420 (ME III) | 1420--1500 (ME IV) | |||||

| tokens | % | tokens | % | tokens | % | tokens | % | ||

| before V | everich | - | 6 | 86 | 7 | 64 | 9 | 39 | |

| everiche | - | 1 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| every | - | 0 | 0 | 4 | 36 | 14 | 61 | ||

| before <h> | everich | - | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | - | ||

| everiche | - | 1 | 100 | 1 | 20 | - | |||

| every | - | 0 | 0 | 3 | 60 | - | |||

| before C | everich | - | 6 | 29 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| everiche | - | 10 | 48 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| every | - | 5 | 24 | 105 | 96 | 138 | 100 | ||

| -LY | 1150--1250 (ME I) | 1250--1350 (ME II) | 1350--1420 (ME III) | 1420--1500 (ME IV) | |||||

| tokens | % | tokens | % | tokens | % | tokens | % | ||

| before V | -lich | 23 | 12 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| -liche | 162 | 87 | 51 | 77 | 23 | 8 | 21 | 5 | |

| -ly | 1 | 1 | 7 | 11 | 251 | 88 | 421 | 95 | |

| before <h> | -lich | 13 | 18 | 7 | 21 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| -liche | 59 | 82 | 24 | 73 | 8 | 14 | 0 | 0 | |

| -ly | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 49 | 84 | 76 | 100 | |

| before C | -lich | 70 | 13 | 18 | 15 | 18 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| -liche | 468 | 85 | 93 | 77 | 39 | 5 | 23 | 2 | |

| -ly | 11 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 788 | 93 | 947 | 97 | |

3つの表で,とりわけ子音の前位置 (before C) で ch の脱落した短形のパーセンテージを通時的に追ってもらいたい.短形の拡大の速度に多少の違いはあるが,ME II と ME III の境である1350年の前後で,明らかな拡大が観察される.14世紀半ばに,ich → I, everich → every, -lich → -ly の変化が著しく生じたことが読み取れる.

もう少し細かくいえば,問題の3項目を比べる限り,ich, everich, -lich の順で,語尾の ch が,とりわけ子音の前位置において脱落していったことがわかる.この変化に関して重要なのは,音節境界における音韻的な要因は確かに作用しているものの,そこに語彙的な要因がかぶさるように作用しているらしいことである.Schlüter (228) の調査のまとめ部分を引用しよう.

. . . the affricate [ʧ] in final position has turned out to constitute another weak segment whose disappearance is codetermined by syllable structure constraints militating against the adjacency of two Cs or Vs across word boundaries. . . . [T]he three studies have shown that the demise of final [ʧ] proceeds at different speeds depending on the item concerned: it is given up fastest in the personal pronoun, not much later in the quantifier, and most hesitantly in the suffix. In other words, the phonetic erosion is overshadowed by lexical distinctions. Relics of the obsolescent long variants are typically found in high-frequency collocations like ich am or everichone, where the affricate is protected from erosion by the ideal phonotactic constellation it ensures.

関連して,「#40. 接尾辞 -ly は副詞語尾か?」 ([2009-06-07-1]) 及び「#832. every と each」 ([2011-08-07-1]) も参照.

・ Schlüter, Julia. "Weak Segments and Syllable Structure in ME." Phonological Weakness in English: From Old to Present-Day English. Ed. Donka Minkova. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. 199--236.

2013-12-28 Sat

■ #1706. 中英語の one the most [syntax][me][superlative][sggk]

中世の英語ロマンスの傑作 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight で,緑の騎士が登場する場面 (ll. 135--56) で,標記の「one the + 最上級」の表現が現れる(引用は Andrew and Waldron 版より).

Þer hales in at þe halle dor an aghlich mayster,

On þe most on þe molde on mesure hyghe;

ここで On þe most は,"the very biggest (one)" ほどの強調された意味をもち,"one of the very biggest (ones)" とは区別されることに注意されたい.最上級を強める働きをする one の用法である.中英語では非常に頻繁に現れる用法で,MED でも ōn (pron.) の語義 7b のもとに,多くの例が挙げられている.OED では,one, adj., n., and pron. の見出し語とのもとで C. pron. †3a に当該の用法の記述がある.

Mustanoja (297) によると,「the + 最上級」の代わりに「the + 原級」が使われる例が Trin. Hom. 185 に1つあるという.

þat is þat bihotene lond, þar is on þe wunsume bureh and on þe hevenliche wunienge þar alle englen inne wunien

しかし,「the + 最上級」のほうが普通であり,この用法は11世紀より文証される.ane þa mæstan synne, on þe fairest toun, oon the grettest remedye, oon the unworthieste, oon the beste knyght, on þe sellokest swyn など枚挙にいとまがない.この用法は16世紀にはまれとなり,Spenser や Shakespeare がほぼ最後の使用者となる.まさに,中英語に華々しく咲いて散った強意の表現だったといえる.

Middle High German, Early Modern High German, Middle Low German, Middle Dutch, Old Norse,Swedish など他のゲルマン諸語にも対応表現が文証され,ギリシア語 μóνος やラテン語 unus の強調用法にも通じるところがあり,またフランス語の une dame la plus belle にも比較されるので,英語の one the most の型にはこれらの関与があるのではないかと疑う向きもあるが,Mustanoja (298--99) は英語独自の発達と見ている.

There is every reason to look upon the types one the good man and one the best man as natural outgrowths of the organic structural pattern of native linguistic usage. They offer striking parallels to the common OE type min se leofa (leofesta) freond. The characteristic feature in constructions of this kind is the isolation of an attribute or other defining word from the noun or noun-group by means of an intervening element (called a Gelenkspartikel and particule d'articulation by German and French Romance scholars). This isolation has the effect of bringing out into relief the idea expressed by the attribute, i.e., of making this word and the whole group more emphatic.

one と the + 最上級とを隔離することによって統語的及び意味的に際立たせるという点に関して,Mustanoja (299) は次のような表現との関連も指摘している.

This peculiar rhythmic arrangement, which probably has counterparts in most languages of the world, is responsible for such common types as all the world, both the(se) boys, half a bottle, too long a story, what a night, etc.

half a bottle のような表現の語順については,「#788. half an hour」 ([2011-06-24-1]) で韻律的な要因を議論したが,Mustanoja のいうように意味的,機能的な要因も考慮する必要があろう.

one the most の型が中英語に咲いて散った表現ということであれば,その前後の時代を含めた通時的な調査も必要となる.

・ Andrew, Malcolm and Ronald Waldron, eds. The Poems of the Pearl Manuscript. 3rd ed. Exeter: U of Exeter P, 2002.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2013-12-03 Tue

■ #1681. 中英語は "creole" ではなく "creoloid" [creole][pidgin][me][old_norse][contact][terminology][creoloid]

「#1223. 中英語はクレオール語か?」 ([2012-09-01-1]),「#1249. 中英語はクレオール語か? (2)」 ([2012-09-27-1]),「#1250. 中英語はクレオール語か? (3)」 ([2012-09-28-1]),「#1251. 中英語=クレオール語説の背景」 ([2012-09-29-1]) を受けて,もう少し議論の材料を提示したい.直接この問題に迫るというよりは,2言語の混合という過程とピジン化 (pidginisation) という過程とをどのように区別するかという問題を考察したい.

混合の前後に連続性が見られず,"the drastic break" (Görlach 341) があると判断される場合にはピジン化といってよいと考えるが,Trudgill (181--82) も Afrikaans を取り上げて同趣旨の議論を展開している.

Interestingly, there are some languages in the world which look like post-creoles, but which are not. These are varieties which, compared to some source, show a certain degree of simplification and admixture. We do not, however, call these languages creoles, because the extent of the simplification and admixture is not very great. And we do not call them post-creoles because they have never been creoles --- which is in turn because they have never been pidgins! Afrikaans, the other major language of the white community in South Africa alongside English, used to be considered a dialect of Dutch . . . . During the course of the twentieth century, however, it achieved autonomy . . . and now has its own literature, dictionaries, grammar books, and so on. Compared to Dutch, Afrikaans shows significant amounts of regularization in the grammar, and a significant amount of admixture from Malay, Portuguese and other languages. It still remains mutually intelligible with Dutch, however. The crucial feature of Afrikaans is that, although it is now spoken by some South Africans who are the descendants of people who spoke it as a non-native language --- hence the influence from Portuguese, Malay and so on --- and who undoubtedly therefore spoke a pidginized form of Dutch/Afrikaans, the language was at no time a pidgin. In the transition from Dutch to Afrikaans, the native-speaker tradition was maintained throughout. The language was passed down from one generation of native speakers to another; it was used for all social functions and was therefore never subjected to reduction. Such a language, which demonstrates a certain amount of simplification and admixture, relative to some source language, but which has never been a pidgin or a creole in the sense that it has always had speakers who spoke a variety which was not subject to reduction, we can call a creoloid.

標準オランダ語に比べれば,Afrikaans には確かに単純化や規則化がみられる.また,マレー語,ポルトガル語などから言語項目の著しい借用がみられる.しかし,だからといって pidgin だとか creole だとか呼ぶわけにはいかない.というのは,Afrikaans には間違いなく歴史的な連続性があるからだ.各世代の話者は,単純化や接触を経験しながらも,途切れることなくこの言語変種を用いてきたし,接触言語と合わせて即席の便宜的な言語を作り出したという痕跡もない."the drastic change" はなかったのである.では,この言語を何と呼ぶのか.Trudgill は,新しい用語として "creoloid" が適切ではないかと主張する.

この "creoloid" という用語は,中英語にもそのまま当てはめられるだろう.古英語と古ノルド語との接触は,creole を生み出したわけではなく,あくまで creoloid を生み出したにすぎなかったといえる.なぜならば,古ノルド語との接触は古英語以来の言語変化の速度を速めたが,あくまで自然な路線の延長であり,連続性があったからだ.同趣旨の議論として,「#1224. 英語,デンマーク語,アフリカーンス語に共通してみられる言語接触の効果」 ([2012-09-02-1]) も参照.

・ Görlach, Manfred. "Middle English --- a Creole?" Linguistics across Historical and Geographical Boundaries. Ed. D. Kastovsky and A. Szwedek. Berlin: Gruyter, 1986. 329--44.

・ Trudgill, Peter. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin, 2000.

2013-10-08 Tue

■ #1625. 中英語期の書き言葉における code-switching [code-switching][me][bilingualism]

「#1470. macaronic lyric」 ([2013-05-06-1]) で紹介したとおり,中英語期には,複数の言語が切り替わる詩作がみられた.一見するところ,第1言語と第2言語との稚拙な混合のように思えるが,その文体的効果を吟味すれば意図的な code-switching であったことがわかる.中英語期における体系的ともいえるこのような code-switching は,叙情詩のみならず,散文を含めたほとんどのジャンルに観察される.例えば,Wright は,"medical writings, other scientific texts, legal texts, administrative texts, sermons, other religious prose texts, literary prose, poems, drama, accounts, inventories, rule-books and letters" (148) を挙げている.Wright (148--49) は散文からの具体例として以下の2つを挙げている.

1. Religious prose text in English and Latin: sermon (early fifteenth century)

Domini gouernouris most eciam be merciful in punchyng. Oportet ipsos attendere quod of stakis and stodis qui deberent stare in ista vinea quedam sunt smoþe and lightlich wul boo, quedam sunt so stif and so ful of warris quod homo schal to-cleue hom cicium quam planare.

(The lord's governors must also be merciful in punishing. They should take notice of the stakes and supports that should stand in this vineyard, some are smooth and will easily bend, others are so stiff and so full of obstinacy that a man will split them sooner than straighten them out.)

2. Letter in English and Anglo-Norman: from R. Kingston to King Henry IV (1403)

Tresexcellent, trespuissant, et tresredoute Seignour, autrement say a present nieez. Jeo prie a la benoit trinite que vous ottroie bone vie ove tresentier sauntee a treslonge durre, and sende yowe sone to ows in helþ and prosperitee; for in god fey, I hope to almighty god that, yef ye come youre owne persone, ye schulle haue the victorie of alle youre enemyes.

(Most excellent, mighty and revered Sir, otherwise I know nothing at present. I pray to the blessed trinity to grant you a good life with the fullest health of the longest duration, and send you soon to us in health and prosperity; for in good faith, I hope to almighty God that, if you come yourself, you shall have a victory over all your enemies.)

code-switching 研究では,話し手(書き手)は言語を切り替えることにより,社会言語学的あるいは語用論的な効果を意図しているということが話題にされる.Wright (149) 曰く,

It has often been assumed that texts which show code-switching are indicative of an ill-educated scribe, who did not know the other languages fully. However, studies on present-day code-switching show that, on the contrary, the speakers usually have a full grasp of both languages, but choose to switch for social and discourse-pragmatic reasons. Similarly, it can frequently be demonstrated that the scribe of a code-switched text did in fact command the grammar and vocabulary of all the languages used, but that he chose to combine them. At present, we are not fully sensitive to the discourse-pragmatic reasons for medieval code-switching, and it is one of the things to which the present-day reader of a medieval text is deaf. (149)

上記のように古い時代の書き言葉に現れる code-switching の意図を読み取ることは困難を極めるが,これらの場合において "social and discourse-pragmatic reasons" がはたして何だったのか,現代語の code-switching 研究により,何かヒントが見いだせるかもしれない.

・ Wright, Laura. "The Languages of Medieval Britain." A Companion to Medieval English Literature and Culture: c.1350--c.1500. Ed. Peter Brown. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2007. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. 143--58.

2013-05-25 Sat

■ #1489. Ferguson の diglossia 論文と中世イングランドの triglossia [diglossia][latin][french][me][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology]

過去3日間の記事 ([2013-05-22-1], [2013-05-23-1], [2013-05-24-1]) で,Ferguson の提唱した diglossia を取り上げてきた.diglossia という社会言語学的状況の定義と評価について多くの論争が繰り広げられてきたが,その議論は全体として,中世イングランドのダイナミックな言語状況を考える上で,数々の重要な観点を与えてくれたのではないか.

前の記事で触れた通り,Ferguson 自身はその画期的な論文で diglossia を同一言語の2変種の併用状況と狭く定義した.異なる2言語については扱わないと,以下のように明記している.

. . . no attempt is made in this paper to examine the analogous situation where two distinct (related or unrelated) languages are used side by side throughout a speech community, each with a clearly defined role. (325, fn. 2)

しかし,2言語(あるいはそれ以上の言語)の間にも "the analogous situation" は確かに見られ,Ferguson の論点の多くは当てはまる.ここで念頭に置いているのは,もちろん,中世イングランドにおける英語,フランス語,ラテン語の triglossia である.以下では,Ferguson の diglossia 論文に依拠して中世イングランドの triglossia を理解しようとする際に考慮すべき2つの点を指摘したい.1つは「#1486. diglossia に対する批判」 ([2013-05-23-1]) でも触れた diglossia の静と動を巡る問題,もう1つは,高位変種 (H) から低位変種 (L) へ流れ込む借用語の問題である.

Ferguson は,原則として diglossia を静的な,安定した状況ととらえた.

It might be supposed that diglossia is highly unstable, tending to change into a more stable language situation. This is not so. Diglossia typically persists at least several centuries, and evidence in some cases seems to show that it can last well over a thousand years. (332)

この静的な認識が後に批判のもととなったのだが,Ferguson が diglossia がどのように生じ,どのように解体されうるかという動的な側面を完全に無視していたわけではないことは指摘しておく必要がある.

Diglossia is likely to come into being when the following three conditions hold in a given speech community: (1) There is a sizable body of literature in a language closely related to (or even identical with) the natural language of the community, and this literature embodies, whether as source (e.g. divine revelation) or reinforcement, some of the fundamental values of the community. (2) Literacy in the community is limited to a small elite. (3) A suitable period of time, on the order of several centuries, passes from the establishment of (1) and (2). (338)

Diglossia seems to be accepted and not regarded as a "problem" by the community in which it is in force, until certain trends appear in the community. These include trends toward (a) more widespread literacy (whether for economic, ideological or other reasons), (b) broader communication among different regional and social segments of the community (e.g. for economic, administrative, military, or ideological reasons), (c) desire for a full-fledged standard "national" language as an attribute of autonomy or of sovereignty. (338)

. . . we must remind ourselves that the situation may remain stable for long periods of time. But if the trends mentioned above do appear and become strong, change may take place. (339)

上の第1の引用の3点は,中世イングランドにおいて,いかにラテン語やフランス語が英語より上位の変種として定着したかという triglossia の生成過程についての説明と解することができる.一方,第2の引用の3点は,中英語後期にかけて,(ラテン語は別として)英語とフランス語の diglossia が徐々に解体してゆく過程と条件に言及していると読める.

次に,中英語における借用語の問題との関連では,Ferguson 論文から示唆的な引用を2つ挙げよう.

. . . a striking feature of diglossia is the existence of many paired items, one H one L, referring to fairly common concepts frequently used in both H and L, where the range of meaning of the two items is roughly the same, and the use of one or the other immediately stamps the utterance or written sequence as H or L. (334)

. . . the formal-informal dimension in languages like English is a continuum in which the boundary between the two items in different pairs may not come at the same point, e.g. illumination, purchase, and children are not fully parallel in their formal-informal range of use. (334)

2つの引用を合わせて読むと,借用(語)に関する興味深い問題が生じる.diglossia の理論によれば,上位変種(フランス語)と下位変種(英語)は,社会的には潮の目のように明確に区別される.これは,原則として,潮の目を連続した一本の線として引くことができるということである.ところが,diglossia という社会言語学的状況が語彙借用という手段を経由して英語語彙のなかに内化されると,illumination ? light や purchase ? buy などの register における上下関係は確かに持ち越されこそするが,その潮の目の高低は個々の対立ペアによって異なる.英仏対立ペアをなす語彙の全体を横に並べたとき,register の上下関係を表わす潮の目の線は,社会的 diglossia の潮の目ほど明確に一本の線をなすわけではないだろう.このことは,diglossia が monoglossia へと解体してゆくとき,diglossia に存在した社会的な上下関係が,monoglossia の語彙の中にもっぱら比喩的に内化・残存するということを意味するのではないか.

・ Ferguson, C. A. "Diglossia." Word 15 (1959): 325--40.

2013-05-22 Wed

■ #1486. diglossia を破った Chaucer [sociolinguistics][bilingualism][me][terminology][chaucer][reestablishment_of_english][diglossia]

「#661. 12世紀後期イングランド人の話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-02-17-1]) で,初期中英語のイングランドにおける言語状況を diglossia として言及した.上層の書き言葉にラテン語やフランス語が,下層の話し言葉に英語が用いられるという,言語の使い分けが明確な言語状況である.3言語が関わっているので triglossia と呼ぶのが正確かもしれない.

diglossia という概念と用語を最初に導入したのは,社会言語学者 Ferguson である.Ferguson (336) による定義を引用しよう.

DIGLOSSIA is a relatively stable language situation in which, in addition to the primary dialects of the language (which may include a standard or regional standards), there is a very divergent, highly codified (often grammatically more complex) superposed variety, the vehicle of a large and respected body of written literature, either of an earlier period or in another speech community, which is learned largely by formal education and is used for most written and formal spoken purposes but is not used by any sector of the community for ordinary conversation.

定義にあるとおり,Ferguson は diglossia を1言語の2変種からなる上下関係と位置づけていた.例として,古典アラビア語と方言アラビア語,標準ドイツ語とスイス・ドイツ語,純粋ギリシア語と民衆ギリシア語 ([2013-04-20-1]の記事「#1454. ギリシャ語派(印欧語族)」を参照),フランス語とハイチ・クレオール語の4例を挙げた.

diglossia の概念は成功を収めた.後に,1言語の2変種からなる上下関係にとどまらず,異なる2言語からなる上下関係をも含む diglossia の拡大モデルが Fishman によって示されると,あわせて広く受け入れられるようになった.初期中英語のイングランドにおける diglossia は,この拡大版 diglossia の例ということになる.

さて,典型的な diglossia 状況においては,説教,講義,演説,メディア,文学において上位変種 (high variety) が用いられ,労働者や召使いへの指示出し,家庭での会話,民衆的なラジオ番組,風刺漫画,民俗文学において下位変種 (low variety) が用いられるとされる.もし話者がこの使い分けを守らず,ふさわしくない状況でふさわしくない変種を用いると,そこには違和感のみならず,場合によっては危険すら生じうる.中世イングランドにおいてこの危険をあえて冒した急先鋒が,Chaucer だった.下位変種である英語で,従来は上位変種の領分だった文学を書いたのである.Wardhaugh (86) は,Chaucer の diglossia 破りについて次のように述べている.

You do not use an H variety in circumstances calling for an L variety, e.g., for addressing a servant; nor do you usually use an L variety when an H is called for, e.g., for writing a 'serious' work of literature. You may indeed do the latter, but it may be a risky endeavor; it is the kind of thing that Chaucer did for the English of his day, and it requires a certain willingness, on the part of both the writer and others, to break away from a diglossic situation by extending the L variety into functions normally associated only with the H. For about three centuries after the Norman Conquest of 1066, English and Norman French coexisted in England in a diglossic situation with Norman French the H variety and English the L. However, gradually the L variety assumed more and more functions associated with the H so that by Chaucer's time it had become possible to use the L variety for a major literary work.

正確には Chaucer が独力で diglossia を破ったというよりは,Chaucer の時代までに,diglossia が破られうるまでに英語が市民権を回復しつつあったと理解するのが妥当だろう.

なお,diglossia に関しては,1960--90年にかけて3000件もの論文や著書が著わされたというから学界としては画期的な概念だったといえるだろう(カルヴェ,p. 31).

・ Wardhaugh, Ronald. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 6th ed. Malden: Blackwell, 2010.

・ Ferguson, C. A. "Diglossia." Word 15 (1959): 325--40.

・ ルイ=ジャン・カルヴェ(著),西山 教行(訳) 『言語政策とは何か』 白水社,2000年.

2013-05-06 Mon

■ #1470. macaronic lyric [me][literature][style][bilingualism][register][latin][french][code-switching]

中英語期の叙情詩には,"macaronic lyric" と呼ばれるものがある.macaronic とは,OALD7 の定義を借りれば "(technical) relating to language, especially in poetry, that includes words and expressions from another language" とあり,「各種言語の混じった;雅俗混交体の」などを意味する.macaronic lyric は,当時のイングランドにおいて日常的には英語が,宮廷ではフランス語が,教会ではラテン語が平行的に行なわれていた多言語使用の状況をみごとに映し出す文学作品である.例として,Greentree (396) に引用されている聖母マリアへの賛美歌の1節を挙げる(校訂は Brown 26--27 に基づく).これは,英語とラテン語が交替する13世紀の macaronic lyric である.

Of on that is so fayr and bright

velud maris stella

Brighter than the day-is light

parens & puella

Ic crie to the, thou se to me,

Leuedy, preye thi sone for me

tam pia,

that ic mote come to the

maria

一見すると単なる羅英混在のへぼ詩にも見えるが,Greentree はこれを聖母マリアへの親密な愛着(英語による)と厳格な信仰(ラテン語による)との絶妙のバランスを反映するものとして評価する.気取らない英語と儀礼的なラテン語の交替は,そのまま13世紀の聖母信仰に特徴的な親密と敬意の混合を表わすという.社会言語学や bilingual 研究で論じられる code-switching の文学への応用といえるだろう.

次の2例は,Greentree (395--96) に引用されている De amico ad amicam と名付けられたラブレターの往信と,Responcio と名付けられたそれへの復信である.英語,フランス語,ラテン語が目まぐるしく交替する.

A celuy que pluys eyme en mounde

Of alle tho that I have found

Carissima

Saluz ottreye amour,

With grace and joye alle honoure

Dulcissima

A soun treschere et special

Fer and her and overal

In mundo,

Que soy ou saltz et gré

With mouth, word and herte free

Jocundo

ここでは,英語で嘘偽りのない愛情が表現され,フランス語で慣習的で儀礼的な挨拶が述べられ,ラテン語で警句風の簡潔にして巧みなフレーズが差し込まれている.

私自身には,これらの macaronic lyric の独特な効果を適切に味わうこともできないし,ふざけ半分の言葉遊びと高い文学性との区別をつけることもできない.bilingual ではない者が code-switching の機微を理解しにくいのと同じようなものかもしれない.だが,例えば日本語でひらがな,カタカナ,漢字,ローマ字などを織り交ぜることで雰囲気の違いを表わす詩を想像してみると,中英語の macaronic lyric に少しだけ接近できそうな気もする.Greentree (396) は次のように評価して締めくくっている.

Fluent harmony is an enjoyable and consistent characteristic of the macaronic lyrics. They seem paradoxically unforced, moving easily between languages in common use, to exploit particular characteristics for effect.

なお,後に中世後期より発展することになる「#292. aureate diction」 ([2010-02-13-1]) は,ある意味では macaronic lyric と同じような羅英混合体だが,むしろラテン語かぶれの文体と表現するほうが適切かもしれない.

・ Greentree, Rosemary. "Lyric." A Companion to Medieval English Literature and Culture: c.1350--c.1500. Ed. Peter Brown. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2007. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. 387--405.

・ Brown, Carleton, ed. English Lyrics of the XIIIth Century. Oxford: Clarendon, 1832.

2012-09-29 Sat

■ #1251. 中英語=クレオール語説の背景 [creole][me][family_tree][history_of_linguistics][evolution][sociolinguistics][historiography][language_equality]

##1223,1249,1250 の記事で,中英語=クレオール語とする仮説を批判的に見てきた.およそ議論の決着はついているのだが,議論それ以上に関心を寄せているのは,なぜこの仮説が現われ,複数の研究者に支持されたのかという背景である.

Baily and Maroldt が論争を開いた1970年代以降,クレオール語研究が盛んになり,とりわけ言語進化論や社会言語学へ大きな刺激を与えてきたという状況は,間違いなく関与している.

言語進化論との関係でいえば,Baily and Maroldt は,言語と生物の比喩を強烈に押し出している.

One of the authors has for more than a half-dozen years been contending that internal language-change will result only in new subsystems, while creolization is required for the creation of a new system, i.e. a new node on a family tree. Each node on a family tree therefore has to have, like humans, at least two parents. (22)

これは,比較言語学の打ち立てた the family tree model の肯定でもあり,同時に否定のもう一つの形でもある.この発想自体が議論の的なのだが,いずれにせよクレオール研究の副産物であることは疑い得ない.

次に,解放の言語学ともいえる社会言語学の発展との関係では,世界語の座に最も近い,威信のある言語である英語を,社会的には長らく,そして現在も根強く劣等イメージの付されたクレオール語と同一視させることによって,論者は言語的平等性を主張することができるのではないか.特定の言語に付された優勢あるいは劣勢のイメージは,あくまで社会的な価値観の反映であり,言語それ自体に優劣はなく平等なのだ,というメッセージを,論者はこの仮説を通じて暗に伝えているのではないか.

私は,このような解放のイデオロギーとでもいうような動機が背景にあるのではないかと想定しながら Bailey and Maroldt を読んでいた.そのように想定しないと,[2012-09-27-1]の記事「#1249. 中英語はクレオール語か? (2)」でも言及したように,論者が英語をどうしても creolisation の産物に仕立て上げたいらしい理由がわからないからだ.支離滅裂な議論を持ち出しながらも,「英語=クレオール語」を推したいという想いの背景には,ある意味で良心的,解放的なイデオロギーがあるのではないか,と.

ところが,論文の最後の段落で,この想定は見事に裏切られた.むしろ,逆だったのだ.creolisation の議論を手段とした世界語としての英語の賛歌だったのである.これには愕然とした.読みが甘かったか・・・.

A closing word on the value of creolization will not be amiss. Just as the evolution of plants and animals became vastly more adaptive, once sexual reproduction became a reality --- because then the propagation of mutations through crossing of strains became feasible --- so creolization enables languages to adapt themselves to new communicative needs in a much less restricted way than is otherwise open to most languages. Thus creolization has the same adaptive and survival value for languages as sexual cross-breeding has for the world of plants or animals. The flexibility and adaptability which have made English so valuable as a world-wide medium of communication are no doubt due to its long history of creolization. (53)

[2012-04-14-1]の記事「#1083. なぜ英語は世界語となったか (2)」で取り上げた Bragg の英語史観も参照.

・ Bailey, Charles James N. and Karl Maroldt. "The French Lineage of English." Langues en contact --- Pidgins --- Creoles --- Languages in contact. Ed. Jürgen M. Meisel. Tübingen: Narr, 1977. 21--51.

2012-09-28 Fri

■ #1250. 中英語はクレオール語か? (3) [creole][me][french][old_norse][contact][historiography]

「#1223. 中英語はクレオール語か?」 ([2012-09-01-1]) 及び「#1249. 中英語はクレオール語か? (2)」 ([2012-09-27-1]) に引き続いての話題.

論争のきっかけとなった Bailey and Maroldt は,英語とフランス語との混交によるクレオール語化の説を唱えたが,多くの批判を浴びてきた.私も読んでみたが,突っ込みどころが満載で,論文が真っ赤になった.当該の学説はほぼ否定されているといってよいし,改めて逐一批判する必要もないが,珍説ともいえる議論が随所に繰り広げられており,それはそれでおもしろいのでいくつかピックアップする.

(1) 中英語は,語彙,統語・意味 ("semantax"!),音声・音韻 ("phonetology"!),形態のいずれの部門においても,少なくとも40%は混合物である (21) .(語彙はよいとしても統語・意味や形態の混合度はどのように測るのだろうか?)

(2) "In the instability created by the second, or minor, French creolization is to be seen the origin of the Great Vowel Shift, which, more than anything else, created modern English" (31). (同論文中に関連する言及がほかにないので,この文が何を意味しているのかほとんど不明である.)

(3) "The Anglo-Saxon suffix -līċe (ME -ly), which has a functional counterpart in French -ment, is hardly an example of the reduction of inflections! This is in accord with the assumption of creolization" (33). (第1文内の論理と,第1文と第2文の因果関係が不明.)

(4) 英語とフランス語の名詞の屈折体系は似ており,容易に融和され得た.([2011-11-29-1]の記事「#946. 名詞複数形の歴史の概要」でも触れた通り,複数接尾辞の -es に関する限り,私は両言語の直接的な関係はないと考えている.Hotta 154, 268 [Note 66] を参照.)

(5) 論文全体を通して,英語とフランス語との間に平行関係が観察される言語項目 (pp. 51--52) を,同系統であるがゆえの遺産でもなく,独立平行発達でもなく,個々の借用でもなく,ひっくるめて英仏語のクレオール化として片付けてしまっている.説明としては手っ取り早いだろうが,それでは地道になされてきた個々の研究が泣く.

説明としての手っ取り早さということでいえば,連想するのが大野晋の日本語・タミール語クレオール説だ.大野は両言語間の比較言語学に基づく系統関係の樹立に失敗し,代わりに両言語のクレオール説を唱えた.後者では厳密な音韻対応は必要とされず,大まかな混交ということで片付けられるからだ.

クレオール化説の雑でいい加減な印象を減じるためには,クレオールの研究自体がもっと成熟する必要がある.それから改めてクレオール化説を提起したらどうだろうか.

・ Bailey, Charles James N. and Karl Maroldt. "The French Lineage of English." Langues en contact --- Pidgins --- Creoles --- Languages in contact. Ed. Jürgen M. Meisel. Tübingen: Narr, 1977. 21--51.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi. The Development of the Nominal Plural Forms in Early Middle English. Hituzi Linguistics in English 10. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo, 2009.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow