2019-09-11 Wed

■ #3789. 古英語語彙におけるラテン借用語比率は1.75% [latin][loan_word][borrowing][oe][lexicology][statistics]

英語語源学の第一人者 Durkin によれば,古英語期までに英語に借用されたラテン単語の数は,少なくとも600語はあるという.650年辺りを境に,前期に300語ほど,後期に300語ほどという見立てである.この600という数字を古英語語彙全体から眺めてみると,1.75%という割合がはじき出される.しかし,これらのラテン借用語単体ではなく,それに基づいて作られた合成語や派生語までを考慮に入れると,古英語語彙における割合は4.5%に跳ね上がる.Durkin (100) の解説を引用しよう.

If we take an estimate of at least 600 words borrowed (immediately) from Latin, and a total of around 34,000 words in Old English, then, conservatively, around 1.75% of the total are borrowed from Latin. If we include all compounds and derivatives formed on Latin loanwords in Old English, then the total of Latin-derived vocabulary probably comes closer to 4.5% . . . , although this figure may be a little too high, since estimates of the total size of the Old English vocabulary (native and borrowed) probably rather underestimate the numbers of compounds and derivatives.

この数値をどう評価するかは視点の取り方次第である.後の歴史における英語の語彙借用の規模とその影響を考えれば,この段階でのラテン借用語の割合など,取るに足りない数字にみえるだろう.一方,これこそが英語の語彙借用の歴史の第一歩であるとみるならば,いわば0%から出発した借用語の比率が,すでに古英語期中に1.75%(あるいは4.5%)に達しているというのは,ある程度著しい現象であるといえなくもない.さらにいえば,その多くが千数百年を隔てた現代英語にも残っており,日常語として用いられているものも目立つのである(昨日の記事「#3788. 古英語期以前のラテン借用語の意外な日常性」 ([2019-09-10-1]) を参照).

古英語のラテン借用語については英語史研究においてもさほど注目されてきたわけではないが,見方を変えれば十分に魅力的なトピックになりそうだ.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-10 Tue

■ #3788. 古英語期以前のラテン借用語の意外な日常性 [latin][loan_word][oe][lexicology][lexical_stratification][statistics][borrowing]

昨日の記事「#3787. 650年辺りを境とする,その前後のラテン借用語の特質」 ([2019-09-09-1]) で触れたように,古英語期以前,とりわけ650年より前に入ってきた最初期のラテン借用語には,現在でも日常的に用いられているものが多い.「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]) などで見てきたように,ラテン借用語にはレベルの高い単語が多いのは事実だが,古英語期以前の借用語に関していえば,そのステレオタイプは必ずしも事実を表わしていない.

Durkin (138--39) による興味深い数値がある.Durkin は,「#3400. 英語の中核語彙に借用語がどれだけ入り込んでいるか?」 ([2018-08-18-1]) でも示したとおり,"Leipzig-Jakarta list of basic vocabulary" と呼ばれる通言語的に最も基本的な意味を担う100語を現代英語から取り出し,そのなかにどれほど借用語が含まれているかを調査してみた.結果としては,ラテン借用語についていえば,そこには1語も含まれていなかった.

しかし,別途 "the WOLD survey" による1,460個の基本的な意味項目からなる日常語リストで調査してみると,137語ほど(およそ10%)が古英語期以前に借用されたラテン借用語と認定されるものだった.しかも,それらの単語は,24個設けられている意味のカテゴリーのうち,"Kinship", "Quantity", "Miscellaneous function words" を除く21個のカテゴリーにわたって見出されるという.つまり,英語史上,最初期に入ってきたラテン借用語は,広い分野にわたり日常的に用いられる英語の語彙の少なからぬ部分を構成しているというわけだ.古英語の形で具体例をいくつか挙げておこう.

・ butere "butter"

・ ele "oil"

・ cyċene "kitchen"

・ ċȳse, ċēse "cheese"

・ wīn "wine" (and its compounds)

・ sæterndæġ "Saturday"

・ mūl "mule"

・ ancor "anchor"

・ līn "line, continuous length"

・ mylen (and its compounds) "mill"

・ scōl, sċolu (and the compound leornungscōl) "school"

・ weall "wall"

・ pīpe "pipe, tube"

・ pīle "mortar"

・ disċ "plate/platter/bowel/dish"

・ candel "lamp, lantern, candle"

・ torr "tower"

・ prēost and sācerd "priest"

・ port "harbour"

・ munt "mountain or hill"

このようにラテン借用語のなかには意外と多く「基本語彙」もあることを銘記しておきたい.関連して,基本語彙の各記事も参照.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-09 Mon

■ #3787. 650年辺りを境とする,その前後のラテン借用語の特質 [latin][loan_word][oe][chronology][lexicology][borrowing][link]

英語史におけるラテン借用語といえば,古英語期のキリスト教用語,初期近代英語期のルネサンス絡みの語彙(あるいは「インク壺用語」 (inkhorn_term)),近現代の専門用語を中心とする新古典主義複合語などのイメージが強い.要するに「堅い語彙」というステレオタイプだ.本ブログでも,それぞれ以下の記事で取り上げてきた.

・ 「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1])

・ 「#296. 外来宗教が英語と日本語に与えた言語的影響」 ([2010-02-17-1])

・ 「#1895. 古英語のラテン借用語の綴字と借用の類型論」 ([2014-07-05-1])

・ 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1])

・ 「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1])

・ 「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1])

・ 「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1])

・ 「#1615. インク壺語を統合する試み,2種」 ([2013-09-28-1])

・ 「#3157. 華麗なる splendid の同根類義語」 ([2017-12-18-1])

・ 「#3438. なぜ初期近代英語のラテン借用語は増殖したのか?」 ([2018-09-25-1])

・ 「#3013. 19世紀に非難された新古典主義的複合語」 ([2017-07-27-1])

・ 「#3179. 「新古典主義的複合語」か「英製羅語」か」 ([2018-01-09-1])

俯瞰的にいえば,このステレオタイプは決して間違いではないが,日常的で卑近ともいえるラテン借用語も存在するという事実を忘れてはならない.大雑把にいえば紀元650年辺りより前,つまり大陸時代から初期古英語期にかけて英語(あるいはゲルマン諸語)に入ってきたラテン単語の多くは,意外なことに,よそよそしい語彙ではなく,日々の生活になくてはならない語彙を構成しているのである.この事実は「ラテン語=威信と教養の言語」という等式の背後に隠されているので,よく確認しておくことが必要である.

650年というのはおよその年代だが,この前後の時代に入ってきたラテン借用語のタイプは異なっている.単純化していえば,それ以前は「親しみのある」日常語,それ以降は「お高い」宗教と学問の用語が入ってきた.Durkin (103) の要約文を引用しよう.

The context for most of the later borrowings is certain: they are nearly all words connected with the religious world or with learning, which were largely overlapping categories in the Anglo-Saxon world. Many of them are only very lightly assimilated into Old English, if at all. In fact it is debatable whether some of them should even be regarded as borrowed words, or instead as single-word switches to Latin in an Old English document, since it is not uncommon for words only ever to occur with their Latin case endings.

The earlier borrowings include many more words that are of reasonably common occurrence in Old English and later, for instance names of some common plants and foodstuffs, as well as some very basic words to do with the religious life.

では,具体的に前期・後期のラテン借用語とはどのような単語なのか.それについては今後の記事で紹介していく予定である.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-08-29 Thu

■ #3776. 機能語の強音と弱音 (2) [phonetics][lexicology][syntax]

「#3713. 機能語の強音と弱音」 ([2019-06-27-1]) でみたように,機能語には単音節で強形と弱形をもっているものが多い.各々がどのような場合に用いられるかは,主としてその統語的な役割に応じて決定される.具体的にいえば,単体で用いられるときや文末に起こるときには強形が,それ以外の場合には弱形が用いられるのが原則である.ここから,弱形が頻度として圧倒的に勝っていることがわかるだろう.典型的な用例を菅原 (121) から挙げよう.

| 単体 | 文末 | 文中 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| am | [æm] | Indeed I am [æm]. | I am [əm/m] leaving today. |

| is | [ɪz] | I think she is [ɪz]. | The grass is [əz/z] wet. |

| do | [duː] | You earn more than I do [duː]. | What do [də] they know? |

| will | [wɪl] | No more than you will [wɪl]. | That will [wəl/wl̩/əl/l̩] do. |

| can | [kæn] | But you can [kæn]. | George can [kən/kn̩] go. |

| at | [æt] | Who're you looking at [æt]? | Look at [ət] that. |

| for | [fɔr] | What did you do it for [fɔr]? | They did it for [fər/fr̩] fun. |

| to | [tuː] | The one we are talking to [tuː]. | They're going to [tə] Spain. |

| of | [ɑːv] | What are you thinking of [ɑːv]? | a lot of [əv/ə] apples |

文末というのは統語的には厳密ではない.正確にいえば,直後に空範疇 (empty category) がある場合である.したがって,"Readyi I am ___i [æm] to help you." や "I left the meetingi she stayed at [æt] ___i till then." においては強形が現われることになる.

・ 菅原 真理子 「第3章 句レベルの音韻論」菅原 真理子(編)『音韻論』朝倉日英対照言語学シリーズ 3 朝倉書店,2014年.106--32頁.

2019-08-09 Fri

■ #3756. アイルランド語からの借用語の年代別分布 [loan_word][irish][celtic][statistics][lexicology]

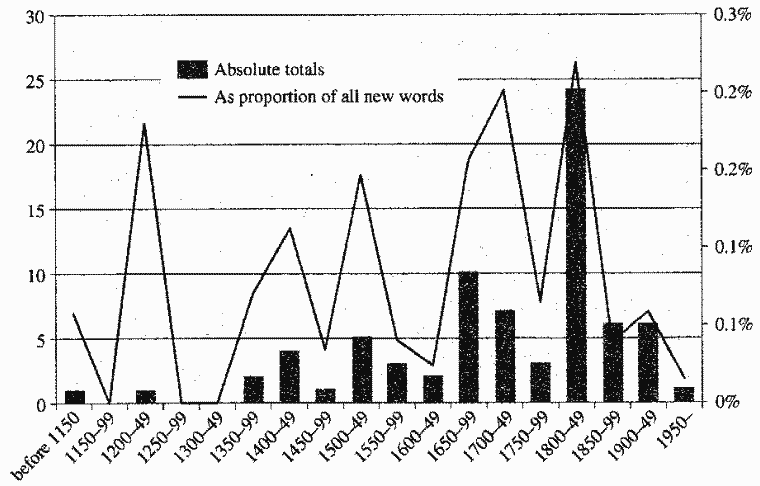

連日ケルト関係の話題を続けているが,「#3740. ケルト諸語からの借用語」 ([2019-07-24-1]),「#3750. ケルト諸語からの借用語 (2)」 ([2019-08-03-1]),「#3749. ケルト諸語からの借用語に関連する語源学の難しさ」 ([2019-08-02-1]),「#3753. 英仏語におけるケルト借用語の比較・対照」 ([2019-08-06-1]) に引き続き借用語の話題.

Durkin の OED3 を用いた調査によれば,英語に少なからぬ語彙的影響を与えた上位25位の言語のなかで,ケルト系諸語としてはアイルランド語のみがランクインするという.そこで,借用元言語としてアイルランド語にターゲットを絞って,借用語数を年代別にプロットしたのが次のグラフである (Durkin 94) .OED3 の A--ALZ, M--RZ の部分のみを対象とした調査である.

19世紀前半に借用語数のピークが来ているが,同時期の全借用語における割合でみれば0.2%を越える程度であり,著しいわけではない.多少のデコボコはあるにせよ,アイルランド借用語は常に目立たない存在であったことがわかる.考察範囲をケルト諸語全体に広げてみても,事情は変わらないだろう.関連して他の言語からの借用語の分布も比べてもらいたい.

・ 「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1])

・ 「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1])

・ 「#874. 現代英語の新語におけるソース言語の分布」 ([2011-09-18-1])

・ 「#2162. OED によるフランス語・ラテン語からの借用語の推移」 ([2015-03-29-1])

・ 「#2164. 英語史であまり目立たないドイツ語からの借用」 ([2015-03-31-1])

・ 「#2165. 20世紀後半の借用語ソース」 ([2015-04-01-1])

・ 「#2369. 英語史におけるイタリア語,スペイン語,ポルトガル語からの語彙借用の歴史」 ([2015-10-22-1])

・ 「#2385. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計 (2)」 ([2015-11-07-1])

・ 「#2646. オランダ借用語に関する統計」 ([2016-07-25-1])

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-08-06 Tue

■ #3753. 英仏語におけるケルト借用語の比較・対照 [french][celtic][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology][etymology][gaulish][language_shift][diglossia][sociolinguistics][contrastive_language_history]

昨日の記事「#3752. フランス語のケルト借用語」 ([2019-08-05-1]) で,フランス語におけるケルト借用語を概観した.今回はそれと英語のケルト借用語とを比較・対照しよう.

英語のケルト借用語の数がほんの一握りであることは,「#3740. ケルト諸語からの借用語」 ([2019-07-24-1]),「#3750. ケルト諸語からの借用語 (2)」 ([2019-08-03-1]) で見てきた.一方,フランス語では昨日の記事で見たように,少なくとも100を越えるケルト単語が借用されてきた.量的には英仏語の間に差があるともいえそうだが,絶対的にみれば,さほど大きな数ではない.文字通り,五十歩百歩といってよいだろう.いずれの社会においても,ケルト語は社会的に威信の低い言語だったということである.

しかし,ケルト借用語の質的な差異には注目すべきものがある.英語に入ってきた単語には日常語というべきものはほとんどないといってよいが,フランス語のケルト借用語には,Durkin (85) の指摘する通り,以下のように高頻度語も一定数含まれている(さらに,そのいくつかを英語はフランス語から借用している).

. . . changer is quite a high-frequency word, as are pièce and chemin (and its derivatives). If admitted to the list, petit belongs to a very basic level of the vocabulary. The meanings 'beaver', 'beer', 'boundary', 'change', 'fear' (albeit as noun), 'to flow', 'he-goat', 'oak', 'piece', 'plough' (albeit as verb), 'road', 'rock', 'sheep', 'small', and 'sow' all figure in the list of 1,460 basic meanings . . . . Ultimately, through borrowing from French, the impact is also visible in a number of high-frequency words in the vocabulary of modern English . . . beak, carpentry, change, cream, drape, piece, quay, vassal, and (ultimately reflecting the same borrowing as French char 'chariot') carry and car.

この質的な差異は何によるものなのだろうか.伝統的な見解にしたがえば,ブリテン島のブリトン人はアングロサクソン人の侵入により比較的短い期間で駆逐され,英語への言語交代 (language_shift) も急速に進行したと考えられている.一方,ガリアのゴール人は,ラテン語・ロマンス祖語の話者たちに圧力をかけられたとはいえ,長期間にわたり共存する歴史を歩んできた.都市ではラテン語化が進んだとしても,地方ではゴール語が話し続けられ,diglossia の状況が長く続いた.言語交代はあくまでゆっくりと進行していたのである.その後,フランス語史にはゲルマン語も参入してくるが,そこでも劇的な言語交代はなかったとされる.どうやら,英仏語におけるケルト借用語の質の差異は言語接触 (contact) と言語交代の社会的条件の違いに帰せられるようだ.この点について,Durkin (86) が次のように述べている.

. . . whereas in Gaul the Germanic conquerors arrived with relatively little disruption to the existing linguistic situation, in Britain we find a complete disruption, with English becoming the language in general use in (it seems) all contexts. Thus Gaul shows a very gradual switch from Gaulish to Latin/Romance, with some subsequent Germanic input, while Britain seems to show a much more rapid switch to English from Celtic and (maybe) Latin (that is, if Latin retained any vitality in Britain at the time of the Anglo-Saxon settlement).

この英仏語における差異からは,言語接触の類型論でいうところの,借用 (borrowing) と接触による干渉 (shift-induced interference) の区別が想起される (see 「#1985. 借用と接触による干渉の狭間」 ([2014-10-03-1]), 「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1])) .ブリテン島では borrowing の過程が,ガリアでは shift-induced interference の過程が,各々関与していたとみることはできないだろうか.

フランス語史の光を当てると,英語史のケルト借用語の特徴も鮮やかに浮かび上がってくる.これこそ対照言語史の魅力である.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-08-05 Mon

■ #3752. フランス語のケルト借用語 [french][celtic][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology][etymology][gaulish][hybrid][hfl]

連日英語におけるケルト諸語からの借用語を話題にしているが,観点をかえてフランス語におけるケルト借用語の状況を,Durkin (83--87) に依拠してみていこう.

ローマ時代のフランス(ガリア)では,ラテン語と並んで土着のゴール語 (Gaulish) も長いあいだ用いられていた.都市部ではラテン語や(ロマンス祖語というべき)フランス語の前身が主として話されていたが,地方ではゴール語も粘り強く残っていたようだ.この長期にわたる接触の結果として,後のフランス語には,英語の場合よりも多くのケルト借用語が取り込まれてきた.とはいっても,100語を越える程度ではある(見方によって50--500語までの開きがある).ただし,「#3749. ケルト諸語からの借用語に関連する語源学の難しさ」 ([2019-08-02-1]) で英語の場合について議論を展開したように,借用の時期やルートの特定は容易ではないようだ.この数には,ラテン語時代に借用されたものや,いくつもの言語の仲介を経て間接的に借用されたものなども含まれており,フランス語話者とゴール語話者の直接の接触に帰せられるべきものばかりではない.

上記の問題点に注意しつつ,以下に意味・分野別のケルト借用語リストの一部を挙げよう (Durkin 84) .

・ 動物:bièvre "beaver", blaireau "badger", bouc "billy goat", mouton "sheep", vautre "type of hunting dog"; chamois "chamois", palefroi "palfrey", truie "sow" (最後の3つは混種語)

・ 鳥:alouette "lark", chat-huant "tawny owl"

・ 魚:alose "shad", loche "loach", lotte "burbot", tanche "tench", vandoise "dace", brochet "pike"; limande "dab" (ケルト接頭辞を示す)

これらの「フランス単語」のうち,後に英語に借用されたものもある.mutton, palfrey, loach, tench, chamois などの英単語は,実はケルト語起源だったということだ.しかし,英単語 buck, beaver などは事情が異なり,フランス語の bièvre, bouc との類似は借用によるものではなく,ともに印欧祖語にさかのぼるからだろう.brasserie (ビール醸造)や cervoise (古代の大麦ビール)などは,ゴール人の得意分野を示しているようでおもしろい.

フランス語におけるケルト借用語のその他の候補をアルファベット順に挙げてみよう (Durkin 84) .

| arpent | 'measure of land' |

| bec | 'beak' |

| béret | 'beret' |

| borne | 'boundary (marker)' |

| boue | 'mud' |

| bouge | 'hovel, dive' (earlier 'bag') |

| bruyère | 'heather, briar-root' |

| changer | 'to change' |

| char | 'chariot' (reflecting a borrowing which had occurred already in classical Latin, whence also charrue 'plough') |

| charpente | 'framework' (originally the name of a type of chariot) |

| chemin | 'road, way' |

| chêne | 'oak' |

| craindre (partly) | 'to fear' |

| crème | 'cream' |

| drap | 'sheet, cloth' |

| javelot | 'javelin' |

| lieue | 'league (measure of distance)' |

| marne | 'marl' (earlier marle, hence English marl) |

| pièce | 'piece' |

| ruche | 'beehive' |

| sillon | 'furrow' |

| soc | 'ploughshare' |

| suie | 'soot' |

| vassal | 'vassal' |

| barre | 'bar' |

| jaillir | 'to gush, spring, shoot out' |

| quai | 'quay' |

英仏語におけるケルト借用語の傾向の差異という話題については,明日の記事で.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-08-03 Sat

■ #3750. ケルト諸語からの借用語 (2) [celtic][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology][etymology][toponymy][onomastics][irish]

昨日の記事「#3749. ケルト諸語からの借用語に関連する語源学の難しさ」 ([2019-08-02-1]) で論じたように,英語におけるケルト借用語の特定は様々な理由で難しいとされる.今回は,「#3740. ケルト諸語からの借用語」 ([2019-07-24-1]) のリストと部分的に重なるものの,改めて専門家による批評を経た上で,確かなケルト借用語とみなされるものを挙げていきたい.その専門家とは,英語語源学の第1人者 Durkin である.

Durkin (77--81) は,古英語期のあいだ(具体的にその時期のいつかについては詳らかにしないが)に借用されたとされる Brythonic 系のケルト借用語をいくつかを挙げている.まず,brock "badger" (OE brocc) は手堅いケルト借用語といってよい.これは,「アナグマ」を表わす語として,初期近代英語期に badger にその主たる地位を奪われるまで,最も普通の語だった.

「かいばおけ」をはじめめとする容器を指す bin (OE binn) も早い借用とされ,場合によっては大陸時代に借りられたものかもしれない.

coomb "valley" (OE cumb) も確実なケルト借用語で,古英語からみられるが主として地名に現われた.地名要素としての古いケルト借用語は多く,古英語ではほかに luh "lake", torr "rock, hill", funta "fountain", pen "hill, promontory" なども挙げられる.

The Downs に残る古英語の dūn "hill" も,しばしばケルト借用語と認められている.「#1395. up and down」 ([2013-02-20-1]) で見たとおり,私たちにもなじみ深い副詞・前置詞 down も同一語なのだが,もしケルト借用語だとすると,ずいぶん日常的な語が借りられてきたものである.他の西ゲルマン諸語にもみられることから,大陸時代の借用と推定される.

「ごつごつした岩」を意味する crag は初例が中英語期だが,母音の発達について問題は残るものの,ケルト借用語とされている.coble 「平底小型漁船」も同様である.

hog (OE hogg) はケルト語由来といわれることも多いが,形態的には怪しい語のようだ.

次に,ケルト起源説が若干疑わしいとされる語をいくつか挙げよう.古英語の形態で bannuc "bit", becca "fork", bratt "cloak", carr "rock", dunn "dun, dull or dingy brown", gafeluc "spear", mattuc "mattock", toroc "bung", assen/assa "ass", stǣr/stær "history", stōr "incense", cæfester "halter" などが挙がる.専門的な見解によると,gafeluc は古アイルランド語起源ではないかとされている.

古アイルランド語起源といえば,ほかにも drȳ "magician", bratt "cloak", ancra/ancor "anchorite", cursung "cursing", clugge "bell", æstel "bookmark", ċine/ċīne "sheet of parchment folded in four", mind "a type of head ornament" なども指摘されている.この類いとされるもう1つの重要な語 cross "cross" も挙げておこう.

最近の研究でケルト借用語の可能性が高いと判明したものとしては,wan "pale" (OE wann), jilt, twig がある.古英語の trum "strong", dēor "fierce, bold", syrce/syrc/serce "coat of mail" もここに加えられるかもしれない.

さらに雑多だが重要な候補語として,rich, baby, gull, trousers, clan も挙げておきたい (Durkin 91) .

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-08-02 Fri

■ #3749. ケルト諸語からの借用語に関連する語源学の難しさ [celtic][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology][contact][etymology][hydronymy]

「#3740. ケルト諸語からの借用語」 ([2019-07-24-1]) を受け,より専門的な語源学の知見を参照しながら英語へのケルト借用語について考えておきたい.主として参照するのは,Durkin の第5章 "Old English in Contact with Celtic" (76--95) である.

ケルト諸語から英語への借用語が少ないという事実は疑いようがないが,ケルト借用語とされている個々の単語については,語源や語史の詳細が必ずしも明らかになっていないものも多い.先の記事で挙げたような,一般の英語史書でしばしば取り上げられる一連の単語は比較的「手堅い」ものが多いが,その中にももしかすると怪しいものがあるかもしれない.本当にケルト語からの借用語なのかという本質的な問題から,どの時代に借用されたのか,あるいはいずれのケルト語から入ってきたのかといった問題まで,様々だ.

背景には,英語の歴史とケルト諸語の語源の両方に詳しい専門家が少ないという現実的な事情もある.また,ケルト語源学やケルト語比較言語学そのものも,発展の余地をおおいに残しているという側面もある.たとえば,河川名などの地名に関して「#1188. イングランドの河川名 Thames, Humber, Stour」 ([2012-07-28-1]) でみたように,ケルト語源を疑う見解もあるのだ.

さらに,時期の特定の問題も難しい.英語話者とケルト諸語の話者との接触は,前者が大陸にいた時代から現代に至るまで,ある意味では途切れることなく続いている.問題の語が,大陸時代にゲルマン語に借用されたケルト単語なのか,アングロサクソン人のブリテン島への渡来の折に入ってきたものなのか,その後の中世から近代にかけてのある時点において流入したものなのか,判然としないケースもある.

いずれのケルト語から入ってきたかという問題については,その特定に際して,「#778. P-Celtic と Q-Celtic」 ([2011-06-14-1]) で触れた音韻的な特徴がおおいに参考になる.しかし,この音韻差の発達は紀元1千年紀中に比較的急速に起こったとされ,ちょうどアングロサクソン人の渡来と前後する時期なので,語源の特定にも微妙な問題を投げかける.

今後ケルト言語学が発展していけば,上記の問題にも答えられる日が来るのだろう.今後の見通しについては,Durkin (80--81) の所見を参考にされたい.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-07-24 Wed

■ #3740. ケルト諸語からの借用語 [celtic][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology][welsh][scottish_gaelic][irish]

歴史的に,アングロサクソン人とケルト人の関係は征服者と被征服者の関係である.通常,水が下から上に流れることがないように,原則としてケルト語から英語への語彙の流入もなかった.小規模な語彙の流入があったとしても,あくまで例外的とみるべきである.

「#1216. 古英語期のケルト借用語」 ([2012-08-25-1]) で示したものと重なるが,大槻・大槻 (58) より,アングロサクソン時代に英語に借用され,かつ現在まで生き残っているものを挙げると,bin (basket), dun (gray), ass (ass < Latin asinus) 程度のものである.また,ケルトのキリスト教を経由して英語に入ってきたものとしては clugge (bell), drȳ (magician) などがある.

中英語期以降にも散発的にケルト諸語からの借用がみられた.以下,世紀別にいくつか挙げてみよう(W = Welsh, G = Scottish Gaelic, Ir = Irish) .質も量も地味である.

・ 14世紀: crag 絶壁 (G/Ir), flannel フランネル (W), loch 湖 (G).

・ 15世紀: bard 吟遊詩人 (G), brog 小錐 (Ir), clan 氏族 (G), glen 峡谷 (G).

・ 16世紀: brogue 地方訛り (Ir/G), caber 丸太棒 (G), cairn ケルン (G), coracle かご船 (W), gillie 高地族長の従者 (G), plaid 格子縞の肩掛け (G), shamrock シロツメクサ (Ir), slogan スローガン (G), whisky ウィスキー (G), usquebaugh ウィスキー.

・ 17世紀: dun こげ茶の (G/Ir), tory トーリー党 (Ir), leprechaun レプレホーン (Ir).

・ 18世紀: claymore 諸刃の剣 (G).

・ 19世紀: colleen 少女 (Ir), ceilidh 集い (Ir/G), hooligan ちんぴら(Ir).

・ 20世紀: corgi コーギー犬 (W).

(W).

以上,大槻・大槻 (58--59) に拠った.関連して「#2443. イングランドにおけるケルト語地名の分布」 ([2016-01-04-1]),「#2578. ケルト語を通じて英語へ借用された一握りのラテン単語」 ([2016-05-18-1]) を参照.

・ 大槻 博,大槻 きょう子 『英語史概説』 燃焼社,2007年.

2019-07-23 Tue

■ #3739. 素朴な疑問を何点か [sobokunagimon][link][y][do-periphrasis][verb][lexicology][phrasal_verb]

今期の理論言語学講座「史的言語学」(すでに終了)の講座を受講されていた方より,素朴な疑問をいくつかいただいていました.既存のブログ記事へ差し向ける回答が多いのですが,せっかくですのでその回答をこちらにオープンにしておきます.

[ 1.英語の Y/N 疑問文はどうして作り方が違うのですか? (be 動詞があると be 動詞が先頭に来て,ないと do や does が先頭にくる) ]

[ 2. 上記の do はどうしてこのように使うようになったのですか?(do はどこからやってきたのですか?) ]

この2つの素朴な疑問については,来月8月14日に発売予定の大修館『英語教育』9月号に,ズバリこの話題で記事を寄稿していますので,ご期待ください(連載については「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ」を参照).hellog 記事としては,「#486. 迂言的 do の発達」 ([2010-08-26-1]),「#491. Stuart 朝に衰退した肯定平叙文における迂言的 do」 ([2010-08-31-1]) をご覧ください.

[ 3. アルファベットの Y は何故ワイと読むのですか? ]

いくつか説があるようですが,とりあえず「#1830. Y の名称」 ([2014-05-01-1]) を参照ください.

[ 4. 不規則動詞はどうして不規則のままで今使われているのですか? ]

[ 5. どうして動詞には規則変化動詞と不規則変化動詞があるのですか? ]

この2つの素朴な疑問については,「#3670.『英語教育』の連載第3回「なぜ不規則な動詞活用があるのか」」 ([2019-05-15-1]) の記事で紹介したリンク先の記事や,『英語教育』の雑誌記事(拙著)をご参照ください.

[ 6. 同じような意味で複数の単語があるのはどうしてですか?(require と need とか) ]

英語語彙には「階層」があります.典型的に3層構造をなしますが,これについては「#2977. 連載第6回「なぜ英語語彙に3層構造があるのか? --- ルネサンス期のラテン語かぶれとインク壺語論争」」 ([2017-06-21-1]) を始めとして,そこにリンクを張っている記事をご参照ください.require はフランス語からの借用語,need は本来の英単語となります.

[ 7. 動詞と前置詞の組み合わせで表す表現はどうして使われ始めたのですか? 動詞1語で使う単語と2語以上に組み合わせた単語はどちらが先に出てきたのですか? ]

いわゆる「句動詞」 (phrasal_verb) の存在についての質問かと思います.「#2351. フランス語からの句動詞の借用」 ([2015-10-04-1]) で紹介したように,中英語期にフランス語の句動詞を翻訳借用 (loan_translation) したということもありますが,「#3606. 講座「北欧ヴァイキングと英語」」 ([2019-03-12-1]) の 14. 句動詞への影響 でみたように,ヴァイキングの母語(古ノルド語)の影響によるところも大きいと考えられます.もっと調べる必要がありそうです.

[ 8. 第3文型と第4文型は薑き換えが可能ですが,どうして2つのパターンが生じたのですか? ]

これは本ブログでも取り上げたことのない問いです.難しい(とても良い)問いですね・・・.今後,考えていきたいと思います.

ということで,不十分ながらも回答してみました.素朴な疑問,改めてありがとうございました.

2019-07-09 Tue

■ #3725. 語彙力診断テストや語彙関連ツールなど [lexicology][bnc][coca][corpus][webservice][link]

以前「#833. 語彙力診断テスト」 ([2011-08-08-1]) を紹介したが,今回は中田(著)『英単語学習の科学』 (12) で取り上げられていた別の語彙診断力テスト Test Your Vocabulary Online With VocabularySize.com を紹介しよう.140問の4択問題をクリックしながら解き進めていくことで,word family ベースでの語彙力が判定できる.母語を日本語に設定して診断する.また,英語での出題のみとなるが,同じ語彙セットを用いた100問からなる語彙診断テストの改訂版もある.

関連して中田 (13) では,英単語の頻度レベルを調べるツールとして,Compleat Lexical Tutor の VocabProfilers が便利だとも紹介されている.BNC や COCA などを利用して,入力した単語(群)の頻度を1000語レベル,2000語レベルなどと千語単位で教えてくれる.ある程度の長さの英文を放り込むと,各単語を語彙レベルごとに色づけしてくれたり,分布の統計を返してくれる優れものだ.ただし,インターフェースがややゴチャゴチャしていて分かりにくい.

日本人の英語学習者にとっては,「標準語彙水準 SVL 12000」などに基づいて英文の語彙レベルを判定してくれる Word Level Checker も便利である.単語ごとにレベルを返してくれるわけではなく,入力した英文内の語彙レベルとその分布を返してくれるというツールである.

英文を入力すると,単語の語注をアルファベット順に自動作成してくれる Apps 4 EFL の Text to Flash というツールも便利だ.さらにこれの応用版で,単語をクリックすると意味がポップアップ表示される英文読解ページを簡単に作れる Pop Translation なるツールもある.世の中,便利になったものだなあ.

・ 中田 達也 『英単語学習の科学』 研究社,2019年.

2019-07-08 Mon

■ #3724. 日本語語彙を作り上げてきた歴史的な言語層 [japanese][lexicology][substratum_theory][contact][borrowing]

沖森(編著)『日本語史概説』の4章「語彙史」に,日本語のルーツの問題に踏み込んだ「日本語語彙の層」に関する話題が提供されている.安本美典と大野晋の各々による「基礎語彙四階層」の説が紹介されており,表の形式でまとめられているので,そちらを掲げよう.

┌───┬────────────────┬──────┐ │ │ 安本美典 │ 大野 晋 │ ├───┼────────────────┼──────┤ │第一層│古極東アジア語の層 │タミル語 │ │ │ │ │ │ │(朝鮮語・アイヌ語・日本語) │(南まわり)│ │ │ │ │ │ │文法的・音韻的骨格 │縄文時代 │ ├───┼────────────────┼──────┤ │第二層│インドネシア・カンボジア語の層 │タミル語 │ │ │ │ │ │ │(基礎語彙) │(北回り) │ ├───┼────────────────┼──────┤ │第三層│ビルマ系江南語の層 │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │(身体語・数詞・代名詞・植物名)│漢語の層 │ │ │ │ │ │ │列島語の統一 │ │ ├───┼────────────────┤ │ │第四層│中国語の層 │ │ │ │ ├………………┤ │ │(文化的語彙) │印欧語の層 │ └───┴────────────────┴──────┘

安本は第一層を「北方由来説」に立脚して古極東アジア語の層とみている.続いて,第二層を「南方由来」に従って基礎語彙の層ととらえている.第三層にはビルマ系江南語の層を据え,これにより列島日本語が完成したとみなしている.そして,第四層が中国語から借用された文化語彙の層であるという立場だ.

一方,大野は論争の的になったタミル語説を提唱しながら,第一層は南まわり,第二層は北まわりでタミル語彙が供給されたと論じている(安本説と北方・南方の順序が異なることに注意).その後,第三層として文化語彙を構成する漢語の層を認め,さらに近世以降の西洋諸語からの借用語を念頭に,印欧語の層を設定している.

日本語語彙を作り上げてきた歴史的な言語層に関する二つの説を眺めていて,英語の場合はどうだろうかと関心が湧いた.およそ古い層から順に,印欧祖語,ゲルマン語,ラテン語,ケルト語,古ノルド語,フランス語,ギリシア語,その他の諸言語といったところだろうか.曲がりなりにも日本語と英語の語彙史を比較できてしまう点がおもしろい.語彙史に関しては,両言語はある程度似ているといえるのだ.関連して「#1526. 英語と日本語の語彙史対照表」 ([2013-07-01-1]) も参照.

・ 沖森 卓也(編著),陳 力衛・肥爪 周二・山本 真吾(著) 『日本語史概説』 朝倉書店,2010年.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2019-06-27 Thu

■ #3713. 機能語の強音と弱音 [phonetics][lexicology]

英語の語彙を統語・形態・音韻・意味・語用など様々な側面を考慮に入れて2分する方法に,内容語 (content word) と機能語 (function word) への分類がある.意味的な基準にもとづいて大雑把にいえば,内容語は意味内容や情報量が十分な語であり,機能語はそれが不十分な語である.品詞との関わりでいえば,それぞれ次のような分布となる(福島,p. 92).

・ 内容語:名詞,動詞,形容詞,副詞,指示代名詞,感嘆詞,否定詞

・ 機能語:冠詞,助動詞,be 動詞,前置詞,人称代名詞,接続詞,関係代名詞/副詞

機能語の音韻的特徴を1つ挙げておこう.それは,特に1音節の機能語に関して,文中での音韻的役割に応じて,強形と弱形の2つの音形が認められることである.以下,福島 (93--94) より代表例を挙げよう.

| 機能語 | 強形 | 弱形 |

| 冠詞 | ||

| a | /eɪ/ | /ə/ |

| an | /æn/ | /ən, n/ |

| the | /ðiː/ | /ði, ðə/ |

| 助動詞 | ||

| can | /kæn/ | /kən/ |

| could | /kʊd/ | /kəd/ |

| must | /mʌst/ | /məst/ |

| shall | /ʃæl/ | /ʃəl, ʃl/ |

| should | /ʃʊd/ | /ʃəd/ |

| will | /wɪl/ | /wəl, əl/ |

| would | /wʊd/ | /wəd, əd/ |

| be 動詞 | ||

| am | /æm/ | /əm, m/ |

| are | /ɑːr/ | /ər/ |

| is | /ɪz/ | /z, s/ |

| was | /wɑːz/ | /wəz/ |

| were | /wɜːr/ | /wər/ |

| been | /biːn/ | /bɪn/ |

| 前置詞 | ||

| at | /æt/ | /ət/ |

| for | /fɔːr/ | /fər/ |

| from | /frʌm, frɑːm/ | /frəm/ |

| to | /tuː/ | /tə/ |

| upon | /əˈpɑːn, əˈpɔːn/ | /əpən/ |

| 人称代名詞 | ||

| my | /maɪ/ | /mi, mə/ |

| me | /miː/ | /mi, mɪ/ |

| you | /juː/ | /jʊ, ju/ |

| your | /jʊər/ | /jər/ |

| he | /hiː/ | /hi, hɪ, i, ɪ/ |

| his | /hɪz/ | /ɪz/ |

| him | /hɪm/ | /ɪm/ |

| she | /ʃiː/ | /ʃi/ |

| her | /hɜːr/ | /hər, əːr/ |

| we | /wiː/ | /wi/ |

| our | /ˈaʊər/ | /ɑːr/ |

| us | /ʌs/ | /əs/ |

| they | /ðeɪ/ | /ðe/ |

| their | /ðeər/ | /ðer/ |

| them | /ðem/ | /ðəm, əm, m/ |

| 接続詞 | ||

| and | /ænd/ | /ənd, nd, ən, n/ |

| as | /æz/ | /əz/ |

| but | /bʌt/ | /bət/ |

| or | /ɔːr/ | /ər/ |

| than | /ðæn/ | /ðən, ðn/ |

| that | /ðæt/ | /ðət/ |

| 関係代名詞/副詞 | ||

| who | /huː/ | /hu, u/ |

| whose | /huːz/ | /huz, uz/ |

| whom | /huːm/ | /hum, um/ |

| that | /ðæt/ | /ðət/ |

これらの機能語には上記のように弱形と強形の2パターンがあり得るが,圧倒的に頻度の高いのは弱形であることを付け加えておく.

・ 福島 彰利 「第5章 強勢・アクセント・リズム」服部 義弘(編)『音声学』朝倉日英対照言語学シリーズ 2 朝倉書店,2012年.84--103頁.

2019-06-25 Tue

■ #3711. 印欧祖語とゲルマン祖語にさかのぼる基本英単語のサンプル [indo-european][germanic][lexicology][etymology]

『英語語源辞典』によると,印欧語比較言語学の成果により,1,000から2,000ほどの印欧語根が想定されている.そのおよそ半数が現代英語の語彙にも反映されているといわれるが,主に基本語彙として受け継がれているものを列挙しよう(寺澤,p. 1656;カッコは借用語を表わす).

| 身体 | arm, brow, ear, eye, foot, heart, knee, lip, nail, navel, tooth |

| 家族 | father, mother, brother, sister, son, daughter, nephew, widow |

| ?????? | beaver, cow, ewe, goat, goose, hare, hart, hound, mouse, sow, wolf; bee, wasp; louse, nit; crane, ern(e), raven, starling; fish, (lax) |

| 罎???? | alder, ash, asp(en), beech, birch, fir, hazel, tree, withy |

| 飲食物 | bean, mead, salt, water, (wine) |

| 天体・自然現象 | moon, star, sun; snow |

| 数詞 | one, two, ..., ten, hundred |

| 代名詞 | I, me, thou, ye, it, that, who, what |

| 動詞 | be, bear, come, do, eat, know, lie, murmur, ride, seek, sew, sing, stand, weave |

| 形容詞 | full, light, middle, naked, new, sweet, young |

| その他 | acre, ax(e), furrow, month, name, night, summer, wheel, word, work, year, yoke |

一方,ゲルマン祖語にさかのぼる,ゲルマン語に特有の基本英単語を挙げてみよう(寺澤,p. 1657).眺めてみると,印欧祖語の時代に比べ「社会生活の進歩,環境の変化がうかがわれ」「とくに,農耕・牧畜関係の語の充実とともに,航海・漁業関係の語が豊富であり,戦争・宗教関係の語も目立つ」(寺澤,p. 1657)ことが確認できる.

| 身体 | bone, hand, toe |

| 穀物・食物 | berry, broth, knead, loaf, wheat |

| 動物 | bear, lamb, sheep, †hengest (G Hangst), roe, seal, weasel |

| 鳥類 | dove, hawk, hen, rave, stork |

| 海洋 | cliff, east, west, north, south, ebb, sail, sea, ship, steer, keel, haven, sound, strand, swim, net, tackle, stem |

| 戦争 | bow, helm, shield, sword, weapon |

| 絎???? | god, ghost, heaven, hell, holy, soul, weird, werewolf |

| 住居 | bed, bench, hall |

| 社会 | atheling, earl, king, knight, lord, lady, knave, wife, borough |

| 経済 | buy, ware, worth |

| その他 | winter, rain, ground steel, tin |

「基本語彙」を巡る議論については,(基本語彙) の各記事を参照.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2019-06-12 Wed

■ #3698. 語源学習法のすゝめ [etymology][lexicology][academic_word_list][asacul][notice]

過去2日間の記事で,語源を活用した学習法を紹介してきた(「#3696. ボキャビルのための「最も役に立つ25の語のパーツ」」 ([2019-06-10-1]) と「#3697. 印欧語根 *spek- に由来する英単語を探る」 ([2019-06-11-1]) ).中田氏による近著『英単語学習の科学』の第11章「語源で覚える英単語」でも「語源学習法」の効用が説かれている.

英単語は出現頻度によって,(1) 高頻度語,(2) 中頻度語,(3) 低頻度語の3つのグループに分類できます.中頻度語と低頻度語は,リーディングやリスニングにおける出現頻度があまり高くないため,文脈から自然に習得することは困難であり,意図的に学習することが欠かせません.中頻度語と低頻度語を覚えるには,その多く(約3分の2)がラテン語・ギリシア語起源であるため「語源学習法」が有効です.また,学術分野で頻度が高い英単語を集めた Academic Word List (Coxhead, 2000) の約90%もラテン語・ギリシア語起源なので,語源学習法が役に立ちます.(73)

特に中級以上の英語学習者にとって,語源学習法が有効である理由が説得力をもって示されている.中田は,章末において語源学習法のポイントを次のようにまとめている.

・ 英単語をパーツに分解し,パーツの意味を組み立ててその単語の意味を理解する学習法を「語源学習法」と呼ぶ.語源学習法は特に,中頻度語・低頻度語および学術的な英単語の学習に効果的である.

・ 語源学習法には,(1) 単語の長期的な記憶保持が可能になる,(2) 未知語の意味を推測するヒントになる,(3) 単語の体系的・効率的な学習が可能になる,といった利点がある.

・ 既知語やカタカナ語を手がかりにして,数多くの語のパーツを効率的に学習できる.特に,「最も役に立つ25の語のパーツ」は重要.

中田はさらに別の箇所で「無味乾燥になりがちな単語学習を,興味深い発見の連続に変えてくれる」 (75--76) とも述べている.

さらにもう2点ほど地味な利点を付け加えておきたい.1つは,語種の判別ができるようになることだ.主としてラテン語・ギリシア語からなる「パーツ」を多数学ぶことによって,初見の単語でも,ラテン語・ギリシア語のみならずフランス語,スペイン語,イタリア語などを含めたロマンス系諸語からの借用語であるのか,あるいはゲルマン系の本来語であるのか,ある程度判別できるようになる.借用語か本来語かという違いは,語感の形式・略式の差異ともおよそ連動するし,強勢位置に関する規則とも関係してくるので,語種を大雑把にでも判別できることには実用的な意味がある.

もう1つは,借用元の言語も当然ながら学びやすくなるということだ.とりわけ第2外国語としてフランス語なりスペイン語なりのロマンス系諸語を学んでいるのであれば,英語学習と合わせて一石二鳥の成果を得られる.

最近では,語源学習法に基づいた英単語集として,清水健二・すずきひろし(著)『英単語の語源図鑑』(かんき出版,2018年)が広く読まれているようだ.なお,私もこの7月より朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて「英語の歴史と語源」と題するシリーズ講座を開始する予定(cf. 「#3687. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」が始まります」 ([2019-06-01-1])).こちらはボキャビルそのものを主たる目標としているわけではないものの,その知識は当然ながらボキャビルのためにも役立つはずである.

なお,上の第1引用にある Academic Word List については,「#612. Academic Word List」 ([2010-12-30-1]) と「#613. Academic Word List に含まれる本来語の割合」 ([2010-12-31-1]) も参照.

・ 中田 達也 『英単語学習の科学』 研究社,2019年.

2019-06-11 Tue

■ #3697. 印欧語根 *spek- に由来する英単語を探る [etymology][indo-european][latin][greek][metathesis][word_family][lexicology]

昨日の記事「#3696. ボキャビルのための「最も役に立つ25の語のパーツ」」 ([2019-06-10-1]) で取り上げたなかでも最上位に挙げられている spec(t) という連結形 (combining_form) について,今回はさらに詳しくみてみよう.

この連結形は印欧語根 *spek- にさかのぼる.『英語語源辞典』の巻末にある「印欧語根表」より,この項を引用しよう.

spek- to observe. 《Gmc》[その他] espionage, spy. 《L》 aspect, auspice, conspicuous, despicable, despise, especial, expect, frontispiece, haruspex, inspect, perspective, prospect, respect, respite, species, specimen, specious, spectacle, speculate, suspect. 《Gk》 bishop, episcopal, horoscope, sceptic, scope, -scope, -scopy, telescope.

また,語源の取り扱いの詳しい The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language の巻末には,"Indo-European Roots" なる小辞典が付随している.この小辞典から spek- の項目を再現すると,次のようになる.

spek- To observe. Oldest form *spek̂-, becoming *spek- in centum languages.

▲ Derivatives include espionage, spectrum, despise, suspect, despicable, bishop, and telescope.

I. Basic form *spek-. 1a. ESPY, SPY, from Old French espier, to watch; b. ESPIONAGE, from Old Italian spione, spy, from Germanic derivative *speh-ōn-, watcher. Both a and b from Germanic *spehōn. 2. Suffixed form *spek-yo-, SPECIMEN, SPECTACLE, SPECTRUM, SPECULATE, SPECULUM, SPICE; ASPECT, CIRCUMSPECT, CONSPICUOUS, DESPISE, EXPECT, FRONTISPIECE, INSPECT, INTROSPECT, PERSPECTIVE, PERSPICACIOUS, PROSPECT, RESPECT, RESPITE, RETROSPECT, SPIEGELEISEN, SUSPECT, TRANSPICUOUS, from Latin specere, to look at. 3. SPECIES, SPECIOUS; ESPECIAL, from Latin speciēs, a seeing, sight, form. 4. Suffixed form *spek-s, "he who sees," in Latin compounds. a. Latin haruspex . . . ; b. Latin auspex . . . . 5. Suffixed form *spek-ā-. DESPICABLE, from Latin (denominative) dēspicārī, to despise, look down on (dē-), down . . .). 6. Suffixed metathetical form *skep-yo-. SKEPTIC, from Greek skeptesthai, to examine, consider.

II. Extended o-grade form *spoko-. SCOPE, -SCOPE, -SCOPY; BISHOP, EPISCOPAL, HOROSCOPE, TELESCOPE, from metathesized Greek skopos, on who watches, also object of attention, goal, and its denominative skopein (< *skop-eyo-), to see. . . .

2つの辞典を紹介したが,語源を活用した(超)上級者向け英語ボキャビルのためのレファレンスとしてどうぞ.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

・ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. 4th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006.

2019-06-10 Mon

■ #3696. ボキャビルのための「最も役に立つ25の語のパーツ」 [elt][latin][greek][etymology][prefix][combining_form][lexicology]

中田(著)『英単語学習の科学』に,先行研究に基づいた「最も役に立つ25の語のパーツ」が提示されている (76--77) .これは,3000?1万語レベルの英単語を分析した結果,とりわけ多くの語に含まれるパーツを取り出したものである.パーツのほとんどが,ラテン語やギリシア語の接頭字 (prefix) や連結形 (combining_form) である.

| 語のパーツとその意味 | 具体例 |

| spec(t) = 見る | spectacle(見せ物),spectator(観客),inspect(検査する),perspective(視点),retrospect(回顧) |

| posit, pos = 置く | impose(負わせる,課す),opposite(反対の),dispose(配置する,処分する),compose(校正する,作る),expose(さらす) |

| vers, vert = 回す | versus(対),adverse(反対の,不利な),diverse(多様な),divert(転換する),extrovert(外交的な) |

| ven(t) = 来る | convention(大会,しきたり,慣習),prevent(妨げる,予防する),avenue(通り),revenue(歳入),venue(場所) |

| ceive/ceipt, cept = とる(こと) | accept(受け入れる,容認する),exception(例外),concept(概念),perceive(知覚する),receipt(レシート,受け取ること) |

| super- = 越えて | superb(すばらしい),supervise(感得する),superior(上級の),superintendent(監督者),supernatural(超自然の,神秘的な) |

| nam, nom, nym = 名前 | surname(苗字),nominate(指名する),denomination(命名,単位),anonymous(匿名の),synonym(同義語) |

| sens, sent = 感じる | sensible(分別のある),sensitive(敏感な),sensor(センサー),sensation(感覚),consent(同意,同意する) |

| sta(n), stat = 立つ | stable(安定した),status(地位),distant(離れた),circumstance(状況),obstacle(障害) |

| mis, mit = 送る | permit(許可する),transmit(送る),submit(提出する),emit(放射する),missile(ミサイル) |

| med(i), mid(i) = 真ん中 | intermediate(中級の),Mediterranean(地中海),mediocre(並みの),mediate(仲裁する),middle(中央,中間の) |

| pre, pris = つかむ | prison(刑務所),enterprise(事業),comprise(構成する),apprehend(捕らえる,理解する),predatory(捕食性の,食い物にする) |

| dictate, dict = 言う | dictate(書き取らせる,命じる),dedicate(捧げる),predict(予言する),contradict(否定する,矛盾する),verdict(評決) |

| ces(s) = 行く | access(アクセス,接近),excess(超過),recess(休憩),ancestor(先祖),predecessor(前任者) |

| form = 形 | formal(形式的な),transform(変形する),uniform(同形の,制服),format(形式),conform(一致する) |

| tract = 引く | extract(抜粋,抜粋する),distract(気をそらす),abstract(要約,抽象的な),subtract(引く),tractor(トラクター,牽引車) |

| graph = 書く | telegraph(電報),biography(伝記),autograph(サイン),graph(グラフ),geography(地理) |

| gen = 生む | genuine(本物の),gene(遺伝子),genius(天才),indigenous(土着の,固有の),ingenuity(工夫) |

| duce, duct = 導く | conduct(導く),produce(生み出す),reduce(減らす),induce(引き起こす,誘発する),seduce(誘惑する) |

| voca, vok = 声 | advocate(主張する,唱道者),vocabulary(語彙),vocal(声の,ボーカル),invoke(祈る),equivocal(あいまいな) |

| cis, cid = 切る | precise(正確な),excise(削除する),scissors(はさみ),suicide(自殺),pesticide(殺虫剤) |

| pla = 平らな | plain(明白な,平原),plane(平面,平らな),plate(皿),plateau(高原,高原状態) |

| sec, sequ = 後に続く | consequence(結果),sequence(連続),subsequent(その次の),consecutive(連続した),sequel(続編) |

| for(t) = 強い | fortress(要塞),effort(努力),enforce(実施する,強いる),reinforce(強化する),forte(長所) |

| vis = 見る | visible(目に見える),envisage(心に描く),revise(改訂する),visual(視覚の,映像),vision(視力,ビジョン) |

本ブログでも,必ずしもボキャビルを目的とした記事ではないが,接頭辞,接尾辞,連結形について多々取り上げてきた.prefix, suffix, combining_form などの記事をご覧ください.

・ 中田 達也 『英単語学習の科学』 研究社,2019年.

2019-04-14 Sun

■ #3639. retronym [synonym][retronym][terminology][lexicology][semantic_change][magna_carta]

昨日4月13日の朝日新聞朝刊の「ことばサプリ」という欄にレトロニムの紹介があった.レトロニムとは「新語と区別するため,呼び名をつけ直された言葉」のことで,たとえば古い「喫茶」に対する新しい「純喫茶」,同じく「服」に対する「和服」,「電話」に対する「固定電話」,「カメラ」に対する「フィルムカメラ」などの例だ.携帯電話がなかったころは電話といえば固定式の電話だけだったわけだが,携帯電話が普及してきたとき,従来の電話は「固定電話」と呼び直されることになった.時計の世界でも,新しく「デジタル時計」が現われたとき,従来の時計は「アナログ時計」と呼ばれることになった.レトロニム (retronym) とは retro- + synonym というつもりの造語だろう,これ自体がなかなかうまい呼称だし,印象に残る術語だ.

英語にもレトロニムはみられる.例えば,e-mail が現われたことによって,従来の郵便は snail mail と呼ばれることになった.acoustic guitar, manual typewriter, silent movie, landline phone なども,同様に技術革新によって生まれたレトロニムといえる.ほかに whole milk, snow skiing なども.

コンピュータ関係の世界では,技術の発展が著しいからだろう,周辺でレトロニムがとりわけ多く生まれていることが知られている.plaintext, natural language, impact printer, eyeball search, biological virus など.

歴史的な例としては,「#734. panda と Britain」 ([2011-05-01-1]),「#772. Magna Carta」 ([2011-06-08-1]) でみたように,lesser panda, Great Britain, Magna Carta などを挙げておこう.これらも一言でいえば「レトロニム」だったわけだ.術語というのは便利なものである.

2019-02-23 Sat

■ #3589. 「インク壺語」に対する Ben Jonson の風刺 [inkhorn_term][lexicology][hapax_legomenon][renaissance][emode][borrowing][latin][loan_word]

ルネサンス期のラテン・ギリシア語熱に浮かされたかのような「インク壺語」 (inkhorn_term) について,本ブログでも様々に取り上げてきた(とりわけ「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]),「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1]),「#1409. 生き残ったインク壺語,消えたインク壺語」 ([2013-03-06-1]),「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1]),「#2479. 初期近代英語の語彙借用に対する反動としての言語純粋主義はどこまで本気だったか?」 ([2016-02-09-1]),「#3438. なぜ初期近代英語のラテン借用語は増殖したのか?」 ([2018-09-25-1]) を参照).

インク壺語は同時代からしばしば批判や風刺の対象とされてきたが,劇作家 Ben Jonson も,1601年に初上演された The Poetaster のなかでチクリと突いている.Crispinus という登場人物が催吐剤を与えられ,小難しい単語を「吐く」というくだりである.吐かれた順にリストしていくと,次のようになる (Johnson 192; †は現代英語で廃語) .

retrograde, reciprocall, incubus, †glibbery, †lubricall, defunct, †magnificate, spurious, †snotteries, chilblaind, clumsie, barmy, froth, puffy, inflate, †turgidous, ventosity, oblatrant, †obcaecate, furibund, fatuate, strenuous, conscious, prorumped, clutch, tropological, anagogical, loquacious, pinnosity, †obstupefact

OED では,pinnosity を除くすべての単語が見出し語として立てられている.しかし,このなかには Jonson の劇でしか使われていない1回きりの単語も含まれている.現代でも普通に通用するものもあるにはあるが,確かに立て続けに吐かれてはかなわない単語ばかりである.典型的なインク壺語のリストとして使えそうだ.

・ Johnson, Keith. The History of Early English: An Activity-Based Approach. Abingdon: Routledge, 2016.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow