2015-10-19 Mon

■ #2366. なぜ英語人名の順序は「名+姓」なのか [onomastics][personal_name][word_order][syntax][metonymy][genitive][preposition][sobokunagimon]

標題は「姓+名」の語順を当然視している日本語母語話者にとって,しごく素朴な疑問である.日本語では「鈴木一郎」,英語では John Smith となるのはなぜだろうか.

端的にいえば,両言語における修飾語句と被修飾語句の語順配列の差異が,その理由である.最も単純な「形容詞+名詞」という語順に関しては日英語で共通しているが,修飾する部分が句や節など長いものになると,日本語では「修飾語句+被修飾語句」となるのに対して,英語では前置詞句や関係詞句の例を思い浮かべればわかるように「被修飾語句+修飾語句」の語順となる.「鈴木家の一郎」は日本語では「鈴木(の)一郎」と約められるが,「スミス家のジョン」を英語で約めようとすると John (of) Smith となる.だが,「の」であれば,*Smith's John のように所有格(古くは属格)を用いれば,日本語風に「修飾語句+被修飾語句」とする手段もあったのではないかという疑問が生じる.なぜ,この手段は避けられたのだろうか.

昨日の記事「#2365. ノルマン征服後の英語人名の姓の採用」 ([2015-10-18-1]) でみたように,姓 (surname) を採用するようになった理由の1つは,名 (first name) のみでは人物を特定できない可能性が高まったからである.政府当局としては税金管理のうえでも人民統治のためにも人物の特定は重要だし,ローカルなレベルでもどこの John なのかを区別する必要はあったろう.そこで,メトニミーの原理で地名や職業名などを適当な識別詞として用いて,「○○のジョン」などと呼ぶようになった.この際の英語での語順は,特に地名などを用いる場合には,X's John ではなく John of X が普通だった.通常 England's king とは言わず the king of England と言う通りである.原型たる「鈴木の一郎」から助詞「の」が省略されて「鈴木一郎」となったと想定されるのと同様に,原型たる John of Smith から前置詞 of が省略されて John Smith となったと考えることができる.(関連して,屈折属格と迂言属格の通時的分布については,「#1214. 属格名詞の位置の固定化の歴史」 ([2012-08-23-1]),「#1215. 属格名詞の衰退と of 迂言形の発達」 ([2012-08-24-1]) を参照.)

原型にあったと想定される前置詞が脱落したという説を支持する根拠としては,of ではないとしても,Uppiby (up in the village), Atwell, Bysouth, atten Oak などの前置詞込みの姓が早い時期から観察されることが挙げられる.「#2364. ノルマン征服後の英語人名のフランス語かぶれ」 ([2015-10-17-1]) に照らしても,イングランドにおけるフランス語の姓 de Lacy などの例はきわめて普通であった.このパターンによる姓が納税者たる土地所有階級の人名に多かったことは多言を要しないだろう.しかし,後の時代に,これらの前置詞はおよそ消失していくことになる.

英語の外を見渡すと,フランス語の de や,対応するドイツ語 von, オランダ語 van などは,しばしば人名に残っている.問題の「つなぎ」の前置詞の振る舞いは,言語ごとに異なるようだ.

2015-09-26 Sat

■ #2343. 19世紀における a lot of の爆発 [clmet][corpus][lmode][agreement][3pp][syntax][reanalysis]

「#2333. a lot of」 ([2015-09-16-1]) で,現代英語で極めて頻度の高いこの句限定詞 (phrasal determiner) の歴史が,たかだか200年余であることをみた.19世紀に入るまでは,この句における lot は「一山,一組;集団,一群」ほどの語義で用いられており,その後,ようやく「多数;多量」の語義が生じたということだった.そこで,後期近代英語期における a lot of と lots of の例を確認すべく,CLMET3.0 で例文を拾ってみた.(検索結果のテキストファイルはこちら.)

第1期 (1710--1780) のサブコーパス(10,480,431語)からは4例がヒットしたが,いずれも「多数の?」を意味する句としては用いられていない.a lot of my own drawing では「多数」ではなく「一山」の語義として用いられており,"Annuities for lives have occasionally been granted in two different ways; either upon separate lives, or upon lots of lives" では明らかに「集団」の語義だろう.しかし,最初の例などでは,語義が「多数」へと発展していきそうな雰囲気は感じられる.

第2期 (1780--1850) のサブコーパス(11,285,587語)からは22例が得られた.予想通り,問題の用法で使われているものがちらほらと現われ出す.いくつかの例文を挙げよう.

・ You know when a lot of servants gets together they like to talk about their betters; and some, for a bit of swagger, likes to make it appear as though they knew more than they do, and to throw out hints and things just to astonish the others. (Anne Brontë, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848))

・ There’ll be lots to speak for her! (ibid.)

・ . . . there's a high fender, and an iron safe, and some cards about ships that are going to sail, and an almanack, and some desks and stools, and an inkbottle, and some books, and some boxes, and a lot of cobwebs, . . . (Charles Dickens, Dombey and Son (1844))

・ . . . I ran on through a lot of alleys and back-slums, until I got somewhere in St. Giles's, and here I took a cab. (Punch, Vol. 1 (1841))

a lot of の数の一致が判断できる例文は少なかったが,上の第1の例文が興味深い.主語の a lot of servants に対して gets と受けているが,この動詞の -s 語尾は,後続する some . . . likes から判断しても,複数主語に一致する複数現在の -s と考えるのが妥当だろう(複現の -s については 3pp の各記事を参照).

第3期 (1850--1920) のサブコーパス(12,620,207語)からは,表現の頻度自体が大幅に増え,384例がヒットした.lot(s) が旧来の語義で用いられている例も少々みられるが,基本的には現代英語並と疑われるほど普通に「多数の?」の意味で用いられている.1800年前後に初出し,その後数十年で一気に広まった流行語法であることがわかる.

2015-09-16 Wed

■ #2333. a lot of [semantic_change][grammaticalisation][etymology][agreement][determiner][reanalysis][syntax]

9月14日付けで,a lot of がどうして「多くの」を意味するようになったのかという質問をいただいた.これは,英語史や歴史言語学の観点からは,意味変化や文法化の話題としてとらえることができる.以下,核となる名詞 lot の語義と統語的振る舞いの通時的変化を略述しよう.

OED や語源辞典によると,現代英語の lot の「くじ;くじ引き」の語義は,古英語 hlot (allotment, choice, share) にさかのぼる.これ自体はゲルマン祖語 *χlutam にさかのぼり,究極的には印欧祖語の語幹 *kleu- (hook) に起源をもつ.他のゲルマン諸語にも同根語が広くみられ,ロマンス諸語へも借用されている.元来「(くじのための)小枝」を意味したと考えられ,ラテン語 clāvis (key), clāvus (nail) との関連も指摘されている.

さて,古英語の「くじ;くじ引き」の語義に始まり,くじ引きによって決められる戦利品や財産の「分配」,そして「割り当て;一部」の語義が生じた.現代英語の parking lot (駐車場)は,土地の割り当てということである.くじ引きであるから「運,運命」の語義が中英語期に生じたのも首肯できる.

近代英語期に入って16世紀半ばには,くじ引きの「景品」の語義が発達した(ただし,後にこの語義は廃用となる).景品といえば,現在,ティッシュペーパー1年分や栄養ドリンク半年分など,商品の一山が当たることから推測できるように,同じものの「一山,一組」という語義が17世紀半ばに生じた.現在でも,競売に出される品物を指して Lot 46: six chairs などの表現が用いられる.ここから同じ物や人の「集団,一群」 (group, set) ほどの語義が発展し,現在 The first lot of visitors has/have arrived. / I have several lots of essays to mark this weekend. / What do you lot want? (informal) などの用例が認められる.

古い「割り当て;一部」の語義にせよ,新しい「集団,一群」の語義にせよ,a lot of [noun] の形で用いられることが多かったことは自然である.また,lot の前に(特に軽蔑の意味をこめた)様々な形容詞が添えられ,an interesting lot of people や a lazy lot (of people) のような表現が現われてきた.1800年前後には,a great lot of や a large lot of など数量の大きさを表わす形容詞がつくケースが現われ,おそらくこれが契機となって,19世紀初めには形容詞なしの a lot of あるいは lots of が単体で「多数の,多量の」を表わす語法を発達させた.現在「多くの」の意味で極めて卑近な a lot of は,この通り,かなり新しい表現である.

a lot of [noun] や lots of [noun] の主要部は,元来,統語的には lot(s) のはずだが,初期の用例における数の一致から判断するに,早くから [noun] が主要部ととらえられていたようだ.現在では,a lot of も lots of も many や much と同様に限定詞 (determiner) あるいは数量詞 (quantifier) と解釈されている (Quirk et al. 264) .このことは,ときに alot of と綴られたり,a が省略されて lot of などと表記されることからも確認できる.

同じように,部分を表わす of を含む句が限定詞として再分析され,文法化 (grammaticalisation) してきた例として,a number of や a majority of などがある.a [noun_1] of [noun_2] の型を示す数量表現において,主要部が [noun_1] から [noun_2] へと移行する統語変化が,共通して生じてきていることがわかる (Denison 121) .

上記 lot の意味変化については,Room (169) も参照されたい.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

・ Denison, David. "Syntax." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 4. Ed. Suzanne Romaine. Cambridge: CUP, 1998.

・ Room, Adrian, ed. NTC's Dictionary of Changes in Meanings. Lincolnwood: NTC, 1991.

2015-09-01 Tue

■ #2318. 英語史における他動詞の増加 [verb][syntax][case][reanalysis][impersonal_verb][passive][reflexive_pronoun]

英語史には,大規模な他動詞化 (transitivization) の潮流が確認される.古英語では相対的に他動詞(として用いられる動詞)は自動詞よりも少なかったが,中英語にかけて,そしてとりわけ初期近代英語にかけて,その数が増加した.他動詞化という過程は,動詞の意味・用法にかかわることだが,むしろ形式的な要因が大きく関与している.中尾・児馬 (100) によれば,3種類の要因が想定される.

1つは,中英語期に屈折語尾の衰退が進行し,名詞や代名詞において格の形態的な区別がつかなくなったことがある.これにより,古英語では与格目的語や属格目的語をとっていた自動詞が,それらの格と形態上融合した歴史的な対格をとることになった.つまり,目的語はすべて対格であると分析され,動詞そのものも他動詞であると認識されるようになったのである.1200年頃から与格を主語とする受動態構文が現われるようになることも,この再分析と密接な関係にあると考えられる.

2点目として,古英語の動詞にしばしば付加された ġe- などの接頭辞が,中英語までに消失したことがある.古英語では,例えば自動詞 restan (休む),grōwan (生じる)に対して,接頭辞を付加した ġerestan (休ませる),ġegrōwan (生み出す)が他動詞として機能するなど,接辞によって自他を切り替える場合があった.接頭辞が消失し両語の形態的区別が失われると,元来の自動詞の形態に他動詞の機能が付け加わることになった.

3点目に,古英語の動詞には語幹の母音変異によって自他用法を区別するものがあった.brinnan / bærnan (burn), springan / sprengan (spring), stincan / stencan (stink) などがその例である.しかし,その後の変化により両語が形態的に一致するに及んで,後に伝わった唯一の語形が自他の両用法を担うようになった.

上記は,いずれも形式的な変化が原因で,2次的に動詞の意味・用法が変化したというシナリオだが,もちろん動詞自体が内的に意味・用法を変化させたという直接的なシナリオがあった可能性も否定できない.むしろ,形式と機能の両側からの圧力によって,動詞の他動性が強化してきたと考えるほうが無理はないように思われる.līcian のような非人称動詞 (impersonal_verb) の人称化なども,動詞の他動詞化という潮流のなかに位置づけることができそうだが,これは音韻,形態,統語,意味,語用のすべてに関わる現象であり,いずれの要因が変化の引き金となり,推進力となったのかを区別することは容易ではない.また,「#995. The rose smells sweet. と The rose smells sweetly.」 ([2012-01-17-1]) で触れた英語史における linking verb の拡大という問題も,動詞をとりまく統語変化と意味変化とが融合したような様相を呈する.

いずれにせよ,他動詞化の潮流は中英語期に諸要因が集中していたことは言えそうだ.

動詞の自他の転換については,受動態 (passive) の発達や再帰動詞 (reflexive_pronoun) の振る舞いも関連してくるだろう.後者については,「#2185. 再帰代名詞を用いた動詞表現の衰退」 ([2015-04-21-1]),「#2206. 再帰代名詞を用いた動詞表現の衰退 (2)」 ([2015-05-12-1]),「#2207. 再帰代名詞を用いた動詞表現の衰退 (3)」 ([2015-05-13-1]) も参照.また,他動詞という用語については,「#1258. なぜ「他動詞」が "transitive verb" なのか」 ([2012-10-06-1]) を参照されたい.

・ 中尾 俊夫・児馬 修(編著) 『歴史的にさぐる現代の英文法』 大修館,1990年.

2015-08-29 Sat

■ #2315. 前出の接続詞が繰り返される際に代用される that [conjunction][syntax]

昨日の記事「#2314. 従属接続詞を作る虚辞的な that」 ([2015-08-28-1]) と関連した話題.現在では稀あるいは古風な用法だが,if, though, when などの従属接続詞によって導かれる節が,and などにより繰り返される場合に,2度目の接続詞として that がいわば代接続詞風に用いられるというものがある.OED の that, conj. の語義8によれば,"8. Used (like French que) as a substitute instead of repeating a previous conjunction, or conjunctive adverb or phrase. Now rare or arch." とある.初出は,以下のとおり中英語の最初期である.

c1175 Lamb. Hom. 17 Þenne were þu wel his freond..Gif þu hine iseȝe þet he wulle asottie to þes deofles hond..þet þu hine lettest, and wiðstewest.

MED でも that (conj.) の語義 14(a) がこの用法に該当し,"Used as substitute for a conj. or conjunctive phrase in preceding subordinate clause such as if, though, whanne, etc.; -- freq. with and or or" と説明がある.後期中英語からの例としては,例えば Chaucer から次のようなものがある.

・ (c1380) Chaucer CT.SN. (Manly-Rickert) G.314: Men sholde hym brennen in a fyr so reed If he were founde or that men myghte him spye.

・ c1450(c1380) Chaucer HF (Benson-Robinson) 1099: Appollo..make hyt sumwhat agreable, Though som vers fayle in a sillable, And that I do no diligence To shewe craft.

近代に入ってからもこの用法は健在である.

・ 1535 Bible (Coverdale) Esther ii. C, She must come vnto the kynge nomore, excepte it pleased the kynge, and that he caused her to be called by name.

・ 1600 Shakespeare Merchant of Venice iv. i. 8 Since he stands obdurate, And that no lawfull meanes can carry me out of his enuies reach. [Also 27 other examples.]

・ 1611 Bible (King James) 1 Chron. xiii. 2 If it seeme good vnto you, and that it be of the Lord our God, let vs send abroad vnto our brethren. [ Coverd. Yf..yf...]

この用法については,細江 (448) が「古いころには,同類の句が2個以上続くときには,しばしばその2番目以下の文句では,同じ連結をくり返す代わりに,that を用いた」と触れており,やはり Shakespeare から例文を引いている.

that の代接続詞的な用法の発達は不思議ではない.昨日の記事でみたように,中英語では that は虚辞的に他の接続詞に後続し,when that や if that などと用いられ,その接続詞が従属接続詞であることを明示する機能をもっていた.いわば汎用の従属節マーカーだったわけだ.同種の従属節が繰り返される際には,2度目の接続詞は機能的にも形式的にも特別な強調は必要とされないため,that 程度の軽いものが選ばれたのだろう.

OED にも言及があるように,フランス語 que が同じ用法を発達させており,従属接続詞 comme, quand, lorsque, puisque, si, comme si, afin que, après que, avant que, bien que, pour que, quoique などの代用として普通に現われる.以下の例文を参照.

・ Comme il était tard et qu'elle était fatiguée, elle a renoncé à sortir.

・ Si tu le rencontres et qu'il soit de bonne humeur, annonce-lui cette nouvelle.

・ 細江 逸記 『英文法汎論』3版 泰文堂,1926年.

2015-08-28 Fri

■ #2314. 従属接続詞を作る虚辞としての that [conjunction][syntax][relative_pronoun][interrogative_pronoun][expletive]

中英語で著しく発達した統語法の1つに,標題の機能をもった "expletive that" (or "pleonastic that") がある.いわば汎用の従属節マーカーとして機能した that の用法であり,単体で従属接続詞として機能しうる語にも付加したし,単体ではそのように機能できなかった副詞や前置詞などに付加してそれを従属接続詞化する働きももっていた.具体的には,after that, as that, because that, by that, ere that, for that, forto that, if that, lest that, now that, only that, though that, till that, until that, when that, where that, whether that, while that 等々である.

古英語でも小辞 þe が対応する機能を示していたが,上記のように多くの語に付加して爆発的な生産性を示したのは,中英語におけるその後継ともいうべき that である.MED では,他用法の that と区別されて that (particle) として見出しに立てられており,様々な種類の語と結合した用例がおびただしく挙げられている.ここでは例を挙げることはせず,The Canterbury Tales の The General Prologue の冒頭の1行 "Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote" に触れておくにとどめたい.

さて,虚辞の that と呼んだが,それは多分に現代の視点からの呼称である.if や when など本来的な従属接続詞に関しては,付加された that は中英語でも確かに虚辞とみなすことができただろう.しかし,歴史的には従属節マーカーとしての that が付加してはじめて従属節として機能するようになった ere that や while that などにおいては,当初 that は虚辞などではなく本来の統語的な機能を完全に果たしていたことになる.その後,ere や while が単独で従属接続詞として用いられるようになるに及んで,that が虚辞として再解釈されたと考えるべきだろう.現在,前置詞との結合で15世紀に生じた in that が,この that の本来の価値を残している.

上で取り上げたのはいずれも副詞節の例だが (Mustanoja 423--24) ,13--15世紀には that が疑問詞や関係詞と組み合わさった例も頻繁に見られる."what man þat þe wedde schal . . . Loke þu him bowe and love" (Good Wife 23, cited from Mustanoja 193) や "Euery wyght wheche þat to rome wente." (Chaucer Troilus & Criseyde ii. Prol. 36, cited from OED) の類いである.

中英語におけるこの虚辞の that については,Mustanoja (192--93, 423--24) 及び OED より that, conj. の語義6--7を参照されたい.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2015-08-03 Mon

■ #2289. 命令文に主語が現われない件 [imperative][syntax][pragmatics][sociolinguistics][politeness][historical_pragmatics][emode][speech_act]

標題は,長らく気になっている疑問である.現代英語の命令文では通常,主語代名詞 you が省略される.指示対象を明確にしたり,強調のために you が補われることはあるにせよ,典型的には省略するのがルールである.これは古英語でも中英語でも同じだ.

共時的には様々な考え方があるだろう.命令文で主語代名詞を補うと,平叙文との統語的な区別が失われるということがあるかもしれない.これは,命令形と2人称単数直説法現在形が同じ形態をもつこととも関連する(ただし古英語では2人称単数に対しては,命令形と直説法現在形は異なるのが普通であり,形態的に区別されていた).統語理論ではどのように扱われているのだろうか.残念ながら,私は寡聞にして知らない.

語用論的な議論もあるだろう.例えば,命令する対象は2人称であることは自明であるから,命令文において主語を顕在化する必要がないという説明も可能かもしれない.社会語用論の観点からは,東 (125) は「英語は主語をふつう省略しない言語だが,命令文の時だけは省略する.この主語(そして命令された人も)を省略する文法は,ポライトネス・ストラテジーのあらわれだといえよう」と述べている.関連して,東は,命令文以外でも you ではなく一般人称代名詞 one を用いる方がはるかに丁寧であるとも述べており,命令文での主語省略を negative politeness の観点から説明するのに理論的な一貫性があることは確かである.

しかし,ポライトネスによる説明は,現代英語の共時的な説明にとどまっているとみなすべきかもしれない.というのは,初期近代英語では,主語代名詞を添える命令文のほうがより丁寧だったという指摘があるからだ.Fennell (165) 曰く,". . . in Early Modern English constructions such as Go you, Take thou were possible and appear to have been more polite than imperatives without pronouns."

初期近代英語の命令や依頼という言語行為に関連するポライトネス・ストラテジーとしては,I pray you, Prithee, I do require that, I do beseech you, so please your lordship, I entreat you, If you will give me leave など様々なものが存在し,現代に連なる please も17世紀に誕生した.ポライトネスの意識が様々に反映されたこの時代に,むしろ主語付き命令文がそのストラテジーの1つとして機能した可能性があるということは興味深い.上記の東による説明は,よくても現代英語の主語省略を共時的に説明するにとどまり,通時的な有効性はもたないだろう.

この問題については,今後も考えていきたい.

・ Fennell, Barbara A. A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001.

・ 東 照二 『社会言語学入門 改訂版』,研究社,2009年.

2015-07-17 Fri

■ #2272. 歴史的な and の従属接続詞的(独立分詞構文的)用法 [conjunction][participle][syntax][contact][celtic][hc][substratum_theory]

一言で言い表しにくい歴史的な統語構造がある.伝統英文法の用語でいえば,「独立分詞構文の直前に and が挿入される構造」と説明すればよいだろうか.中英語から近代英語にかけて用いられ,現在でもアイルランド英語やスコットランド英語に見られる独特な統語構造だ.Kremola and Filppula が Helsinki Corpus を用いてこの構造の歴史について論じているのだが,比較的理解しやすい例文を以下に再掲することにしよう.

・ And thei herynge these thingis, wenten awei oon aftir anothir, and thei bigunnen fro the eldre men; and Jhesus dwelte aloone, and the womman stondynge in the myddil. (Wyclif, John 8, 9, circa 1380)

・ For we have dwelt ay with hir still And was neuer fro hir day nor nyght. Hir kepars haue we bene And sho ay in oure sight. (York Plays, 120, circa 1459)

・ & ȝif it is founde þat he be of good name & able þat þe companye may be worscheped by him, he schal be resceyued, & elles nouȝht; & he to make an oþ with his gode wil to fulfille þe poyntes in þe paper, þer whiles god ȝiueþ hym grace of estat & of power (Book of London English, 54, 1389)

・ . . . and presently fixing mine eyes vpon a Gentleman-like object, I looked on him, as if I would suruay something through him, and make him my perspectiue: and hee much musing at my gazing, and I much gazing at his musing, at las he crost the way . . . (All the Workes of John Taylor the Water Poet, 1630)

・ . . . and I say, of seventy or eighty Carps, [I] only found five or six in the said pond, and those very sick and lean, and . . . (The Compleat Angler, 1653--1676)

・ Which would be hard on us, and me a widow. (Mar. Edgeworth, Absentee, xi, 1812) (←感嘆的用法)

これらの and の導く節には定動詞が欠けており,代わりに不定詞,現在分詞,過去分詞,形容詞,名詞,前置詞句などが現われるのが特徴である.統語的には主節の前にも後にも出現することができ,機能的には独立分詞構文と同様に同時性や付帯状況を表わす.この構文の頻度は中英語では稀で,近代英語で少し増えたとはいえ,常に周辺的な統語構造であったには違いない.Kremola and Filppula (311, 315) は,統語的に独立分詞構文と酷似しているが,それとは直接には関係しない発達であり,したがってラテン語の絶対奪格構文ともなおさら関係しないと考えている.

それでは,この構造の起源はどこにあるのか.Kremola and Filppula (315) は,不定詞が用いられているケースについては,ラテン語の対格付き不定詞構文の関与もあるかもしれないと譲歩しているものの,それ以外のケースについてはケルト諸語の対応する構造からの影響を示唆している.

The infinitival type, which at least in its non-exclamatory use is closer to coordination than the other types, may well derive from the Latin accusative with the infinitive . . . But the non-infinitival constructions (and the exclamatory infinitival patterns), although they too are often considered to have their origins in the Latin absolute constructions, could also stem from another source, viz. Celtic languages. Whereas the Latin models typically lack the overt subordinator, subordinating and-structures closely equivalent to the ones met in Middle English and Early Modern English are a well-attested feature of the neighbouring Celtic languages from their earliest stages on.

私自身はケルト系言語を理解しないので,Kremola and Filppula (315--16) に挙げられている古アイルランド語,中ウェールズ語,現代アイルランド語からの類似した文例を適切に評価できない.しかし,彼らは,先にも述べたように,現代でもこの構造がアイルランド英語やスコットランド英語に普通に見られることを指摘している.

なお,Filppula は,英語の統語論にケルト諸語の基層的影響 (substratum_theory) を認めようとする論客である.「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1]) の議論も参照されたい.

・ Kremola, Juhani and Markku Filppula. "Subordinating Uses of and in the History of English." History of Englishes: New Methods and Interpretations in Historical Linguistics. Ed. Matti Rissanen, Ossi Ihalainen, Terttu Nevalainen, and Irma Taavitsainen. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1992. 762--71.

2015-07-03 Fri

■ #2258. 諢溷??逍大撫譁? [interrogative][exclamation][tag_question][syntax][word_order][negative]

Hasn't she grown! のような,疑問文の体裁をしているが発話内の力 (illocutionary force) としては感嘆を示す文について考える機会があり,現代英語における感嘆疑問文 (exclamatory question) について調べてみた.以下に Quirk et al. (825) の記述をまとめる.

典型的には,Hasn't she GRÒWN! や Wasn't it a marvellous CÒNcert! のように否定の yes-no 疑問文の形を取り,下降調のイントネーションで発話される(アメリカ英語では上昇調も可).意味的には非常に強い肯定の感嘆を示し,下降調の付加疑問と同様に,聞き手に対して回答というよりは同意を期待している.

否定 yes-no 疑問文ほど頻繁ではないが,肯定 yes-no 疑問文でも,やはり下降調に発話されて,同様の感嘆を示すことができる(アメリカ英語では上昇調も可).ˈAm ˈI HÙNGry!, ˈ Did ˈhe look anNÒYED!, ˈHas ˈshe GRÒWN! の如くである.

統語的には否定であっても肯定であっても,意味としては肯定の感嘆になるというのがおもしろい.統語的な極性が意味的にあたかも中和するかのような例の1つである (cf. 「#950. Be it never so humble, there's no place like home. (3)」 ([2011-12-03-1])) .しかし,Has she grown! と Hasn't she grown! の間には若干の違いがある.否定版は明らかに聞き手に同意や確認を求めるものだが,肯定版は命題を自明のものとみなしており聞き手の同意や確認を求めているわけではないという点である.したがって,自らのことを述べる Am I hungry! などにおいては,同意や確認を求める必要がないために,統語的に肯定版が選ばれる.否定版と肯定版の微妙な差異は,次のようなパラフレーズを通じてつかむことができるだろう.

・ Wasn't it a marvelous CÒNcert! = 'What a marvelous CÒNcert it was!'

・ Has she GRÒWN! = 'She HÀS grown!'

否定版と肯定版とで,発話に際する話者の前提 (presupposition) が関わってくるということである.語用論的にも興味深い統語現象だ.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2015-07-01 Wed

■ #2256. 祈願を表わす may の初例 [word_order][syntax][auxiliary_verb][subjunctive][optative][may]

祈願を表わす助動詞 may の発達過程について「#1867. May the Queen live long! の語順」 ([2014-06-07-1]) で考察した.そこで触れたように,OED によると初例は16世紀初頭のものだが,Visser (1785--86) によれば,稀ながらも,それ以前の中英語期にも例は見つかる.これらの最初期の例では,いずれも may が文頭に来ていないことに注意されたい.

・ c1250 Gen. & Ex. 3283, wel hem mai ben ðe god beð hold!

・ c1425 Chester Whitsun Plays; Antichrist (in: Manly, Spec. I) p. 176, 140, Nowe goo we forthe all at a brayde! from dyssese he may us saue.

・ 1450 Miroure of Oure Ladye (EETS) p. 34, 34, Sonet vox tua in auribus meis, that ys, Thy voyce may sounde in mine eres.

上の最初の例のように,非人称的に用いられる例は後の時代でも珍しくなく,"Wo may you be that laughe now!", "Much good may do you with your note, madam!", そして現代の "Much good may it do you!" などへ続く.

前の記事では,祈願を表わす may の発展の背景には,願望を表わす動詞の接続法の用法と,hope などの動詞に続く従属節のなかでの may の使用があるのではないかと指摘したが,もう1つの伏流として,Visser (1785, 1795) の述べる通り,中英語の助動詞 mote の祈願の用法がある.用例は初期中英語から挙がる,Visser は後期古英語に遡りうると考えている.

・ c1275 Passion Our Lord, in O. E. Misc. 39 Iblessed mote he beo þe comeþ on godes nome

・ c1380 Pearl 397, Blysse mote þe bytyde!

この mote の用法は,MED の mōten (v.(2)) の 7c(b) にも例が挙げられているが,中英語では普通に見られるものである.これが,後に may に取って代わられたということだろう.

なお,過去形 might にも同じ祈願の用法が中英語より見られ,mote と並んで might ももう1つの考慮すべき要因をなすと思われる.MED の mouen (v.(3)) の 4(c) に ai mighte he liven や crist him mighte blessen などの例が挙げられている.

現代英語の may の祈願用法の発達を調査するに当たっては,まず中英語(以前)の mote の同用法の発達を追わなければならない.

・ Visser, F. Th. An Historical Syntax of the English Language. 3 vols. Leiden: Brill, 1963--1973.

2015-06-08 Mon

■ #2233. 統語的な橋渡しとしての I not say. [negative][syntax][word_order][do-periphrasis][negative_cycle][numeral]

英語史では,否定の統語的変化が時代とともに以下のように移り変わってきたことがよく知られている.Jespersen が示した有名な経路を,Ukaji (453) から引こう.

(1) ic ne secge.

(2) I ne seye not.

(3) I say not.

(4) I do not say.

(5) I don't say.

(1) 古英語では,否定副詞 ne を定動詞の前に置いた.(2) 中英語では定動詞の後に補助的な not を加え,2つの否定辞で挟み込むようにして否定文を形成するのが典型的だった.(3) 15--17世紀の間に ne が弱化・消失した.この段階は動詞によっては18世紀まで存続した.(4) 別途,15世紀前半に do-periphrasis による否定が始まった (cf. 「#486. 迂言的 do の発達」 ([2010-08-26-1]),「#1596. 分極の仮説」 ([2013-09-09-1])) .(5) 1600年頃に,縮約形 don't が生じた.

(2) 以下の段階では,いずれも否定副詞が定動詞の後に置かれてきたという共通点がある.ところが,稀ではあるが,後期中英語から近代英語にかけて,この伝統的な特徴を逸脱した I not say. のような構文が生起した.Ukaji (454) の引いている例をいくつか挙げよう.

・ I Not holde agaynes luste al vttirly. (circa 1412 Hoccleve The Regement of Princes) [Visser]

・ I seyd I cowde not tellyn that I not herd, (Paston Letters (705.51--52)

・ There is no need of any such redress, Or if there were, it not belongs to you. (Sh. 2H4 IV.i.95--96)

・ I not repent me of my late disguise. (Jonson Volp. II.iv.27)

・ They ... possessed the island, but not enjoyed it. (1740 Johnson Life Drake; Wks. IV.419) [OED]

従来,この奇妙な否定の語順は,古英語以来の韻文の伝統を反映したものであるとか,強調であるとか,(1) の段階の継続であるとか,様々に説明されてきたが,Ukaji は (3) と (4) の段階をつなぐ "bridge phenomenon" として生じたものと論じた.(3) と (4) の間に,(3') として I not say を挟み込むというアイディアだ.

これは,いかにも自然といえば自然である.(3') I not say は,do を伴わない点で (3) I say not と共通しており,一方,not が意味を担う動詞(この場合 say)の前に置かれている点で (4) I do not say と共通している.(3) と (4) のあいだに統語上の大きな飛躍があるように感じられるが,(3') を仮定すれば,橋渡しはスムーズだ.

しかし,Ukaji 論文をよく読んでみると,この橋渡しという考え方は,時系列に (3) → (3') → (4) と段階が直線的に発展したことを意味するわけではないようだ.Ukaji は,(3) から (4) への移行は,やはりひとっ飛びに生じたと考えている.しかし,事後的に,それを橋渡しするような,飛躍のショックを和らげるようなかたちで,(3') が発生したという考えだ.したがって,発生の時間的順序としては,むしろ (3) → (4) → (3') を想定している.このように解釈する根拠として,Ukaji (456) は,(4) の段階に達していない have や be などの動詞は (3') も示さないことなどを挙げている.(3) から (4) への移行が完了すれば,橋渡しとしての (3') も不要となり,消えていくことになった.と.

英語史における橋渡しのもう1つの例として,Ukaji (456--59) は "compound numeral" の例を挙げている.(1) 古英語から初期近代英語まで一般的だった twa 7 twentig のような表現が,(2) 16世紀初頭に一般化した twenty-three などの表現に移行したとき,橋渡しと想定される (1') twenty and nine が15世紀末を中心にそれなりの頻度で用いられていたという.(1) から (2) への移行が完了したとき,橋渡しとしての (1') も不要となり,消えていった.と.

2つの例から一般化するのは早急かもしれないが,Ukaji (459) は統語変化の興味深い仮説を提案しながら,次のように論文を結んでいる.

I conclude with the hypothesis that syntactic change tends to be facilitated via a bridge sharing in part the properties of the two chronological constructions involved in the change. The bridge characteristically falls into disuse once the transition from the old to the new construction is completed.

・ Ukaji, Masatomo. "'I not say': Bridge Phenomenon in Syntactic Change." History of Englishes: New Methods and Interpretations in Historical Linguistics. Ed. Matti Rissanen, Ossi Ihalainen, Terttu Nevalainen, and Irma Taavitsainen. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1992. 453--62.

2015-04-08 Wed

■ #2172. 古英語の副詞節を導く接続詞 [oe][conjunction][preposition][syntax][case]

Mitchell and Robinson (83--86) より.副詞節を導く接続詞を列挙する.Non-prepositional conjunctions と Prepositional conjunctions に分けられる.まずは前者から.

[ Non-prepositional conjunctions ]

| ǣr | "before" |

| būtan | "but, except that, unless" |

| gif | "if" |

| hwonne | "when" |

| nefne, nemne | "unless" |

| nū | "now that" |

| oð | "until" |

| sam . . . sam | "whether . . . or" |

| siþþan | "after, since" |

| swā þæt | "so that" |

| swelce | "such as" |

| þā | "when" |

| þā hwīle þe | "as long as, while" |

| þanon | "whence" |

| þǣr | "where" |

| þæs | "after" |

| þæt | "that, so that" |

| þēah | "although" |

| þenden | "while'' |

| þider | "whither" |

| þonne | "whenever, when, then" |

| þȳlǣs (þe) | "lest" |

次に Prepositional conjunctions の一覧.これらは,前置詞の後に þæt の適切な格形が続いて(さらに不変化の subordinating particle þe あるいは不変化の þæt が続くこともある),句全体で接続詞として機能するものである.for を例にとれば,for þǣm, for þam, for þan, for þon, for þy, for þi, for þæm þe, forþan þæt など,諸形が用いられる.

[Prepositional conjunctions]

| æfter + dat., inst. | Adv. and conj. "after". |

| ǣr + dat., inst. | Adv. and conj. "before". |

| betweox + dat., inst. | Conj. "while". |

| for + dat., inst. | Adv. "therefore" and Conj. "because, for". For alone as a conj. is late. |

| mid + dat., inst. | Conj. "while, when". |

| oþ + acc. | Conj. "up to, until, as far as" defining the temporal or local limit. It appears as oþþe, oþþæt, and oð ðone fyrst ðe "up to the time at which". |

| tō + dat., inst. | Conj. "to this end, that" introducing clauses of purpose with subj. and of result with ind. |

| tō + gen. | Conj. "to the extent that, so that". |

| wiþ + dat., inst. | Conj. lit. "against this, that". It can be translated "so that", "provided that", or "on condition that". |

関連して,後続古英語の前置詞について「#30. 古英語の前置詞と格」 ([2009-05-28-1]) を参照.

・ Mitchell, Bruce and Fred C. Robinson. A Guide to Old English. 8th ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2015-03-25 Wed

■ #2158. "I wonder," said John, "whether I can borrow your bicycle." (2) [syntax][word_order][verb][agreement][register]

標題のように said John など伝達動詞が主語の前に置かれる語順について,[2015-02-25-1]の記事の続編を送る.現代英語のこの語順について,Biber et al. (922) は,Quirk et al. の記述と多く重なるが,次のような統語的条件を与えている.

Subject-verb order is virtually the rule where one or more of the following three conditions apply:

The subject is an unstressed pronoun:

"The safety record at Stansted is first class," he said. (NEWS)

The verb phrase is complex (containing auxiliary plus main verb):

"Konrad Schneider is the only one who matters," Reinhold had answered. (FICT)

The verb is followed by a specification of the addressee:

There's so much to living that I did not know before, Jackie had told her happily. (FICT)

LGSWE Corpus での調査によると,被引用文句の後位置では SV も VS も全体的におよそ同じくらいの頻度だというが,FICTIONでは SV がやや多く,NEWSでは VS が強く好まれるなど,傾向が分かれるという.ジャンルとの関係でいえば,前回の記事で触れたように,journalistic writing やおどけた場面では被引用文句の前でも VS が起こることがあるという.この問題は使用域や文体との関連が強そうだ.

伝達動詞であるという語彙・意味的制限,上掲の統語的条件,使用域や文体の関与,これらの要因が複雑に絡み合って said John か John said が決定されるとすれば,この問題は多面的に検討しなければならないことになる.ほかにも語用論的な要因が関与している可能性もありそうだし,他の引用文句を導入する表現や手段との比較も必要だろう.通時的な観点からは,諸条件の絡み合いがいかにして生じてきたのか,また書き言葉における引用符の発達などとの関係があるかどうかなど,興味が尽きない.(後者については,「#2004. ICEHL18 に参加して気づいた学界の潮流など」 ([2014-10-22-1]) で紹介した ICEHL18 の学会で,引用符の発達と quoth の衰退とが関与している可能性があるという趣旨の Colette Moore の口頭発表を聴いたことがある.The ICEHL18 Book of Abstracts (PDF) の pp. 170--71 を参照.)

・ Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey Leech, Susan Conrad, and Edward Finegan. Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Harlow: Pearson Education, 1999.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2015-03-13 Fri

■ #2146. 英語史の統語変化は,語彙投射構造の機能投射構造への外適応である [exaptation][grammaticalisation][syntax][generative_grammar][unidirectionality][drift][reanalysis][evolution][systemic_regulation][teleology][language_change][invisible_hand][functionalism]

「#2144. 冠詞の発達と機能範疇の創発」 ([2015-03-11-1]) でみたように,英語史で生じてきた主要な統語変化はいずれも「機能範疇の創発」として捉えることができるが,これは「機能投射構造の外適応」と換言することもできる.古英語以来,屈折語尾の衰退に伴って語彙投射構造 (Lexical Projection) が機能投射構造 (Functional Projection) へと再分析されるにしたがい,語彙範疇を中心とする構造が機能範疇を中心とする構造へと外適応されていった,というものだ.

文法化の議論では,生物進化の分野で専門的に用いられる外適応 (exaptation) という概念が応用されるようになってきた.保坂 (151) のわかりやすい説明を引こう.

外適応とは,たとえば,生物進化の側面では,もともと体温保持のために存在していた羽毛が滑空の役に立ち,それが生存の適応価を上げる効果となり,鳥類への進化につながったという考え方です〔中略〕.Lass (1990) はこの概念を言語変化に応用し,助動詞 DO の発達も一種の外適応(もともと使役の動詞だったものが,意味を無くした存在となり,別の用途に活用された)と説明しています.本書では,その考えを一歩進め,構造もまた外適応したと主張したいと思います.〔中略〕機能範疇はもともと一つの FP (Functional Projection) と考えられ,外適応の結果,さまざまな構造として具現化するというわけです.英語はその通時的変化の過程の中で,名詞や動詞の屈折形態の消失と共に,語彙範疇中心の構造から機能範疇中心の構造へと移行してきたと考えられ,その結果,冠詞,助動詞,受動態,完了形,進行形等の多様な分布を獲得したと言えるわけです.

このような言語変化観は,畢竟,言語の進化という考え方につながる.ヒトに特有の言語の発生と進化を「言語の大進化」と呼ぶとすれば,上記のような言語の変化は「言語の小進化」とみることができ,ともに歩調を合わせながら「進化」の枠組みで研究がなされている.

保坂 (158) は,言語の自己組織化の作用に触れながら,著書の最後を次のように締めくくっている.

こうした言語自体が生き残る道を探る姿は,いわゆる自己組織化(自発的秩序形成とも言われます)と見なすことが可能です.自己組織化とは雪の結晶やシマウマのゼブラ模様等が有名ですが,物理的および生物的側面ばかりでなく,たとえば,渡り鳥が作り出す飛行形態(一定の間隔で飛ぶ姿),気象現象,経済システムや社会秩序の成立などにも及びます.言語の小進化もまさにこの一例として考えられ,言語を常に動的に適応変化するメカニズムを内在する存在として説明でき,それこそ,ことばの進化を導く「見えざる手」と言えるのではないでしょうか.英語における文法化の現象はまさにその好例であり,言語変化の研究がそうした複雑な体系を科学する一つの手段になり得ることを示してくれているのです.

言語変化の大きな1つの仮説である.

・ 保坂 道雄 『文法化する英語』 開拓社,2014年.

2015-03-11 Wed

■ #2144. 冠詞の発達と機能範疇の創発 [article][determiner][syntax][generative_grammar][language_change][grammaticalisation][reanalysis][definiteness]

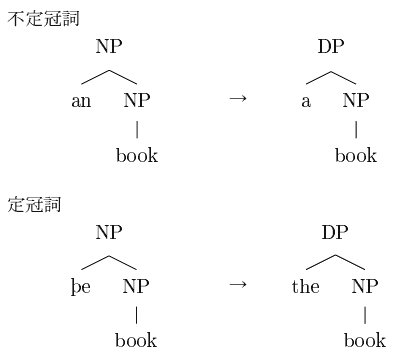

現代英語の不定冠詞 a(n) と冠詞 the は,歴史的にはそれぞれ古英語の数詞 (OE ān) と決定詞 (OE se) から発達したものである.現在では可算名詞の単数ではいずれかの付加が必須となっており,それ以外の名詞や複数形でも定・不定の文法カテゴリーを標示するものとして情報構造上重要な役割を担っているが,古英語や初期中英語ではいまだ任意の要素にすぎなかった.中英語以降,これが必須の文法項目となっていった(すなわち文法化 (grammaticalisation) していった)が,生成文法の立場からみると,冠詞の文法化は新たな DP (Determiner Phrase) という機能範疇の創発として捉えることができる.保坂 (16) を参照して,不定冠詞と定冠詞の構造変化を統語ツリーで表現すると次の通りとなる.

an にしても þe にしても,古英語では,名詞にいわば形容詞として任意に添えられて,より大きな NP (Noun Phrase) を作るだけの役割だったが,中英語になって全体が NP ではなく DP という機能範疇の構造として再解釈されるようになった.これを,DP の創発と呼ぶことができる.件の構造が DP と解釈されるということは,いまや a や the がその主要部となり,補部に名詞句を擁し,全体として定・不定の情報を示す文法機能を発達させたことを意味する.NP のように語彙的な意味を有する語彙範疇から,DP のように文法機能を担う機能範疇へ再解釈されたという点で,この構造変化は文法化の一種と見ることができる.

英語史において機能範疇の創発として説明できる統語変化は多数あり,保坂では次のような項目を機能範疇 DP, CP, IP への再分析の結果の例として取り扱っている.

・ 冠詞の構造変化

不定冠詞,定冠詞

・ 虚辞 there の構造変化

・ 所有格標識 -'s の構造変化

・ 接続詞の構造変化

now, when, while, after, that

・ 関係代名詞の構造変化

that, who

・ 再帰代名詞の構造変化

・ 助動詞 DO の構造変化

・ 法助動詞の構造変化

may, can ,will

・ to 不定詞の構造変化

不定詞標識の to, be going to, have to

・ 進行構文の構造変化

・ 完了構文の構造変化

・ 受動構文のの構造変化

・ 虚辞 it 構文の構造変化

連結詞 BE 構文,it 付き非人称構文

・ 保坂 道雄 『文法化する英語』 開拓社,2014年.

2015-03-03 Tue

■ #2136. 3単現の -s の生成文法による分析 [generative_grammar][syntax][agreement][3sp][verb][inflection][agreement][conjugation]

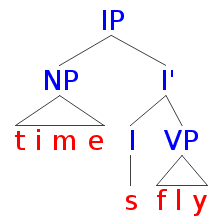

「#2112. なぜ3単現の -s がつくのか?」 ([2015-02-07-1]) で,生成文法による分析を批判的に取り上げた.だが,それはなぜという問いには答えられていないという批判であり,共時的な分析として批判しているわけではない.むしろ,それは主語と動詞の一致 (agreement) を動詞の屈折によって標示する言語に一般的に適用できる,共時的にすぐれた分析だろう.Time flies. という単純な文に生成文法の統語分析を加えると,以下の構文木が得られる(ただし,生成文法でも立場によって機能範疇のラベルや細部の処理が異なる可能性はある).

最上部は文全体に相当する IP (=Inflectional Phrase) であり,主要部に I (=Inflection),指定部に主語となる NP (=Noun Phrase),補部に述語動詞となる VP (=Verb Phrase) をもつ.NP の time と I の s は統率 (government) し合う関係にあるといわれ,この統率関係が上述の一致と深く関連している.NP の time には,[+ 3RD PERSON] と [+ SINGULAR] という素性が付与されており,I に内包される [+ PRESENT] と共鳴して,s という屈折辞が選ばれる.

上の図ではそこまでしか描かれていないが,このあと接辞移動 (affix-hopping) という規則が適用されて,s が VP の fly の末尾に移動し,最後に音韻部門で音形が調えられて time flies という実現形が得られるとされる.要するに,統率関係にある NP と I のもとで,人称・数・時制の各素性の値が照合され,すべて一致すると屈折辞 s が選択されるというルールだ(実際には,3・単・現のほか,直説法であることも必須条件だが,ここでは省略する).このルールを1つ決めておくと,既存の他の統語規則も活用して,関連する応用的な文である否定文 "Time doesn't fly." や疑問文 "Does time fly?" なども正しく生成することができるようになる.

この分析は標準現代英語の3単現の -s にまつわる統語と形態を一貫したやりかたで説明できるという利点はあるが,なぜそのような現象があるのかということは説明しない.生成文法は「何」や「どのように」の問いに答えるのは得意だが,「なぜ」の問いに答えるには,やはり歴史的な視点を採用するほかないだろう.

2015-02-25 Wed

■ #2130. "I wonder," said John, "whether I can borrow your bicycle." [syntax][word_order][verb][agreement]

主語と動詞が倒置される例に,標題のような直接引用を導く said John などの表現がある.引用される文句の後または中間に来るときに,現在形あるいは過去形の伝達動詞が主語に前置される場合である.このような位置で I said, I replied, I thought などの通常の語順を取る場合もあるが,quoth の場合には倒置されるのが規則である.細江 (163--64) から例を挙げよう.

・ "Can I have a light, sir?" said I.---Stevenson.

・ "My very dog," sighed poor Rip, "has forgotten me!"---Irving.

・ But where, thought I, is the crew?---Irving.

・ There was no getting away from these verities, thought Constance.---Bennett.

・ "The swine turned Normans to my comfort!" quoth Gurth.---Scott.

・ Quoth I: "But have you no prison at all now?"---William Morris.

・ "Well," quoth I, "I have always been told that a woman is as old as she looks."---ibid.

引用される文句の後または中間の位置では quoth を除き,SVもVSもいずれも可能ということだが,主語が代名詞か名詞によっても分布は異なる.Quirk et al. (1022) によると,主語が名詞の場合の John said や said John はいずれも普通だが,主語が代名詞の場合は he said が普通で,said he は珍しいか古風だという.古い英語では said he などもごく普通に見られたが,現代までに分布を狭めたらしい.

一方,引用される文句の前に置かれるときに通常倒置は起こらない.しかし,特殊な環境においては起こりうる.細江 (165fn) によると,

もっともややこっけい味を帯びた文または人の発言によって事件の推移の急であるときには,Said she, "Tom, it was middling warm in school, warn't it?"---Mark Twain; Said I: "How do you manage with politics?"---William Morris のようなものもある.すべて,上記の場合にも後に来るものに重点がある.したがって主語が名詞である場合に転置が多く,代名詞のときには常位置が多い.ゆえに代名詞の主語が動詞よりも後に来たときには,特にそれが強く示されているものと見てよい.反対に主語が名詞で,それが動詞より前にあったら,動詞に重点がおかれているものと解すべきである.Cp. "Mr. Sherlock Holms, I believe," said she.---Doyle (これはよもや知るまいと思っていた女が,ちゃんと知っていたから,she が強調された場合); Barbara looked enchanting to-day, Basil thought.---Alfred Noyes (これは Basil の思いに注意が向けられている場合).

また,journalistic writing でも,引用文句の前でときにVSとなる場合がある (ex. "Declared tall, nineteen-year-old Napier: 'The show will go on'." (Quirk et al. 1024fn)) .

ほかに変わったところでは,くだけた会話において行儀の悪い言い返しとして,-s 語尾をつけた says you や says he などが聞かれることがある.A: I'm going to win this game., B: Says you! の如くであり,ここでBが意味しているのは "That's what you say." ほどである.

通時的な関心としては,被引用文句の後や中間において said he のタイプが減少してきた経緯と理由が気になる.歴史統語論や歴史語用論の観点からある程度研究されているのではないかと思われるが,今後調べてみたい.

以下に,直接引用を導く典型的な伝達動詞を一覧していおこう (Quirk et al. 1024)

add, admit, announce, answer, argue, assert, ask, beg, boast, claim, comment, conclude, confess, cry (out), declare, exclaim, explain, insist, maintain, note, object, observe, order, promise, protest, recall, remark, repeat, reply, report, say, shout (out), state, tell, think, urge, warn, whisper, wonder, write

・ 細江 逸記 『英文法汎論』3版 泰文堂,1926年.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2015-01-09 Fri

■ #2083. She'll make a good wife. の構文 [syntax][verb]

現代英語で半ば化石化した構文として知られているものに,標記の構文がある.この make の意味・機能は become に近く,学校文法でいえば主格補語を要求する不完全自動詞であるといわれ,その構文は5文型の枠組みいえば SVC とされる.一方,「彼にとって」の意味を加えて She'll make him a good wife. と表現することもでき,him ≠ a good wife であるから,この構文は SVOO と解釈できる.ここで両構文が関係しているものと解するならば,もとの She'll make a good wife. はむしろ SVO 構文と分析したくなる.このような事情で,標記の構文は SVC とも SVO ともつかない,両方の特性を兼ね備えた不思議な構文ということになる.解釈の仕方は,統語理論によってもまちまちである.

この構文はときに再帰代名詞の省略と説明されることがあるが,その説明には,共時的にも通時的にも確たる裏付けがない.共時的には,She'll make herself a good wife. は文法上もちろん可能だが,標記の構文の代用として現われることはあまりない.また,通時的にも,代名詞を含む構文が原型としてあり,そこから再帰代名詞が省略されてこの構文ができたという歴史的過程を確認することはできない.むしろ,歴史的には make の「作る」という原義と目的語を要求する原用法から発展してきた構文の1つにすぎない.OED (語義24)によると,この構文で用いられる make の語義は,"Of a person: to become by development or training. Also, with object a noun modified by good, bad, or other adjective of praise or the contrary: to perform well (ill, etc.) the part or function of." と記述される.主語の表わす人が発展や訓練を経てあるものへと化ける,というほどの意味を表わし,前者に後者となるための素質が備わっていることが含意されている点で become とは異なる.素材と産物の関係とでもいおうか.この用法が,素材と産物の関係を示す make の他の用法からの派生物であることは,現代英語の次のような例から分かる.

・ Northern Spies make the best apple pie.

・ The platycodon makes a fine pot plant for a cool greenhouse.

・ The Morello Cherry, and other deepe coloured pleasant Cherries, no doubt would make a speciall good wine.

・ Hydrogen and oxygen make water.

・ The clothes don't make the gentleman.

このような素材と産物を表現する make の用法は,OED の例文をみる限りおよそ中英語に起源をもつようだ.もっとも語義は連続体なので,ものによっては古英語に遡るともいえる.OED の語義24に関する限り,その初出例文は中英語末期の "a1470 Malory Morte Darthur (Winch. Coll. 13) (1990) I. 295, I undirtake he is a vylayne borne, and never woll make man." であり,案外と新しい.近現代英語からの例文をいくつか挙げておこう.

・ 1572 H. Middlemore in H. Ellis Orig. Lett. Eng. Hist. (1827) 2nd Ser. III. 8, I think he [sc. the Duke of Anjou] will make as rare a prince as any is in Christendome.[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

・ a1616 Shakespeare Henry VI, Pt. 1 (1623) iv. vii. 44 Doubtlesse he would haue made a noble Knight.

・ 1741 Pope Thoughts on Var. Subj. in Wks. II. 311 For a King to make an amiable character, he needs only to be a man of common honesty, well advised.

・ 1870 E. Peacock Ralf Skirlaugh III. 25 As the times then went, Mr. Earl made a very fair pastor.

・ 1934 H. Roth Call it Sleep i. ix. 63 My, what a tyrant you'll make when you're married!

2015-01-08 Thu

■ #2082. 定着しなかった二重属格 *the knight of his [genitive][article][syntax][do-periphrasis][timeline][synthesis_to_analysis][double_genitive]

英語史には,ある変化A→Bが起きた後B→Aという変化によってまた元に戻る現象が見られることがあり,故中尾俊夫先生はしばしばそうした現象をマザーグースの一節になぞらえて「ヨークの殿様」 (Duke of York) と呼ばれた.ヨークの殿様は大勢の兵隊を一度山の上に上げて,それから下ろす.結果を見れば事情は何も変わっていない.しかし,一見無意味に見えるその行動にも何か理由があったはずで,「英語史にそのような変化が見られるときにはその背後にどんな意味があるのか考えなさい.大きな真実が隠れていることがある.」というのが中尾先生の教えであった.

定冠詞を伴う二重属格構造に関する論文の出だしで,宮前 (179) が以上のように述べている.英語史のなかの "Duke of York" の典型例は,「#486. 迂言的 do の発達」 ([2010-08-26-1]) や「#491. Stuart 朝に衰退した肯定平叙文における迂言的 do」 ([2010-08-31-1]) でみた肯定平叙文での do 迂言法の発達と衰退である.16世紀に一度は発達しかけたが17世紀には衰退し,結局,定着するに至らなかった.ほかには,「#819. his 属格」 ([2011-07-25-1]) や「#1479. his 属格の衰退」 ([2013-05-15-1]) の例も挙げられる.

宮前が扱っている二重属格とは a knight of his や this hat of mine のような構造である.現代英語では *a his knight や *this my hat のように冠詞・指示詞と所有格代名詞を隣接させることができず,迂言的な二重属格構造がその代用として機能する.この構造の起源と成立については諸説あるが,a his knight という原型からスタートし,後期中英語に属格代名詞 his が後置され of とともに現われるようになったという説が有力である(宮前,p. 183).通常,古英語から中英語にかけての属格構造の発達では,属格代名詞が後置されるか of 迂言形に置換されるかのいずれかだったが,二重属格の場合には,その両方が起こってしまったということだ.

二重属格の発達は,14世紀半ばに a man of þair (a man of theirs) のタイプから始まり,名詞の所有者を示す an officer Of the prefectes へも広がった.100年後には,指示詞を伴う this stede of myne のタイプと定冠詞を伴う the fellys of Thomas Bettsons のタイプが現われた.しかし,この4者のうち最後の定冠詞を伴うもののみが衰退し,17世紀中に消えていった.

宮前は,この最後のタイプに関する "Duke of York" の現象を,Dという機能範疇の創発と確立によって一時的に可能となったものの,最終的には「意味的に定冠詞 the をもつ必然性がない」 (192) ために不可能となったものとして分析する.Dという機能範疇の創発と確立は,「#1406. 束となって急速に生じる文法変化」 ([2013-03-03-1]) で触れたように,属格とその代替構造の発達全体に有機的に関わる現象と考えられ,二重属格の発達もその大きな枠組みのなかで捉えるべきだという主張にもつながるだろう(cf. 「#1417. 群属格の発達」 ([2013-03-14-1])). *

一方,定冠詞タイプの衰退について,宮前は意味的な必然性と説明しているが,これは構文の余剰性と言い換えてもよいかもしれない.your car と端的に表現できるところをわざわざ迂言的に the car of yours と表現する必要はない,という理屈だ(宮前,p. 193).

"Duke of York" の背後にある大きな真実を探るというのは,確かに英語史の大きな魅力の1つである.

・ 宮前 和代 「英語史のなかの "Duke of York"」『生成言語研究の現在』(池内正幸・郷路拓也(編著)) ひつじ書房,2013年.179--96頁.

2014-09-19 Fri

■ #1971. 文法化は歴史の付帯現象か? [drift][grammaticalisation][generative_grammar][syntax][auxiliary_verb][teleology][language_change][unidirectionality][causation][diachrony]

Lightfoot は,言語の歴史における 文法化 (grammaticalisation) は言語変化の原理あるいは説明でなく,結果の記述にすぎないとみている."Grammaticalisation, challenging as a phenomenon, is not an explanatory force" (106) と,にべもなく一蹴だ.文法化の一方向性を,"mystical" な drift (駆流)の方向性になぞらえて,その目的論 (teleology) 的な言語変化観を批判している.

Lightfoot は,一見したところ文法化とみられる言語変化も,共時的な "local cause" によって説明できるとし,その例として彼お得意の法助動詞化 (auxiliary_verb) の問題を取り上げている.本ブログでも「#1670. 法助動詞の発達と V-to-I movement」 ([2013-11-22-1]) や「#1406. 束となって急速に生じる文法変化」 ([2013-03-03-1]) で紹介した通り,Lightfoot は生成文法の枠組みで,子供の言語習得,UG (Universal Grammar),PLD (Primary Linguistic Data) の関数として,can や may など歴史的な動詞の法助動詞化を説明する.この「文法化」とみられる変化のそれぞれの段階において変化を駆動する local cause が存在することを指摘し,この変化が全体として mystical でもなければ teleological でもないことを示そうとした.非歴史的な立場から local cause を究明しようという Lightfoot の共時的な態度は,その口から発せられる主張を聞けば,Saussure よりも Chomsky よりも苛烈なもののように思える.そこには共時態至上主義の極致がある.

Time plays no role. St Augustine held that time comes from the future, which doesn't exist; the present has no duration and moves on to the past which no longer exists. Therefore there is no time, only eternity. Physicists take time to be 'quantum foam' and the orderly flow of events may really be as illusory as the flickering frames of a movie. Julian Barbour (2000) has argued that even the apparent sequence of the flickers is an illusion and that time is nothing more than a sort of cosmic parlor trick. So perhaps linguists are better off without time. (107)

So we take a synchronic approach to history. Historical change is a kind of finite-state Markov process: changes have only local causes and, if there is no local cause, there is no change, regardless of the state of the grammar or the language some time previously. . . . Under this synchronic approach to change, there are no principles of history; history is an epiphenomenon and time is immaterial. (121)

Lightfoot の方法論としての共時態至上主義の立場はわかる.また,local cause の究明が必要だという主張にも同意する.drift (駆流)と同様に,文法化も "mystical" な現象にとどまらせておくわけにはいかない以上,共時的な説明は是非とも必要である.しかし,Lightfoot の非歴史的な説明の提案は,例外はあるにせよ文法化の著しい傾向が多くの言語の歴史においてみられるという事実,そしてその理由については何も語ってくれない.もちろん Lightfoot は文法化は歴史の付帯現象にすぎないという立場であるから,語る必要もないと考えているのだろう.だが,文法化を歴史的な流れ,drift の一種としてではなく,言語変化を駆動する共時的な力としてみることはできないのだろうか.

・ Lightfoot, David. "Grammaticalisation: Cause or Effect." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 99--123.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow