2021-08-27 Fri

■ #4505. 「世界語」としてのラテン語と英語とで,何が同じで何が異なるか? [future_of_english][latin][lingua_franca][history][world_englishes][diglossia]

昨日の記事「#4504. ラテン語の来し方と英語の行く末」 ([2021-08-26-1]) に引き続き,「世界語」としての両者がたどってきた歴史を比べることにより英語の未来を占うことができるだろうか,という問題について.

ラテン語と英語をめぐる歴史社会言語学的な状況について,共通点と相違点を思いつくままにブレストしてみた.

[ 共通点 ]

・ 話し言葉としては様々な(しばしば互いに通じない)言語変種へ分裂したが,書き言葉としては1つの標準的変種におよそ収束している

・ 潜在的に非標準変種も norm-producing の役割を果たし得る(近代国家においてロマンス諸語は各々規範をもつに至ったし,同じく各国家の「○○英語」が規範的となりつつある状況がある)

・ ラテン語は多言語のひしめくヨーロッパにあってリンガ・フランカとして機能した.英語も他言語のひしめく世界にあってリンガ・フランカとして機能している.

[ 相違点 ]

・ ラテン語は死語であり変化し得ないが,英語は現役の言語であり変化し続ける

・ ラテン語の規範は不変的・固定的だが,英語の規範は可変的・流動的

・ ラテン語は書き言葉と話し言葉の隔たりが大きく,前者を日常的に用いる人はいない(ダイグロシア的).しかし,英語については,標準英語話者に関する限りではあるが,書き言葉と話し言葉の隔たりは比較的小さく,前者に近い変種を日常的に用いる人もいる(非ダイグロシア的)

・ ラテン語は地理的にヨーロッパのみに閉じていたが,英語は世界を覆っている

・ ラテン語には中世以降母語話者がいなかったが,英語には母語話者がいる

・ ラテン語は学術・宗教を中心とした限られた(文化的程度の高い)分野において主として書き言葉として用いられたが,英語は分野においても媒体においても広く用いられる

・ ラテン語の規範を定めたのは使用者人口の一部である社会的に高い階層の人々.英語の規範を定めたのも,18世紀を参照する限り,使用者人口の一部である社会的に高い階層の人々であり,その点では似ているといえるが,21世紀の英語の規範を作っている主体はおそらくかつてと異なるのではないか.一般の英語使用者が集団的に規範制定に関与しているのでは?

時代も状況も異なるので,当然のことながら相違点はもっと挙げることができる.例えば,関わってくる話者人口などを比較すれば,2桁も3桁も異なるだろう.一方,共通項をくくり出すには高度に抽象的な思考が必要で,そう簡単にはアイディアが浮かばない.皆さん,いかがでしょうか.

英語の未来を考える上で,英語史はさほど役に立たないと思っています.しかし,人間の言語の未来を考える上で,英語史は役に立つだろうと思って日々英語史の研究を続けています.

2021-08-26 Thu

■ #4504. ラテン語の来し方と英語の行く末 [future_of_english][latin][lingua_franca][history][world_englishes]

かつてヨーロッパではリンガ・フランカ (lingua_franca) としてラテン語が長らく栄華を誇ったが,やがて各地で様々なロマンス諸語へ分裂していき,近代期中に衰退するに至った.この歴史上の事実は,英語の未来を考える上で必ず参照されるポイントである.英語は現代世界でリンガ・フランカの役割を担うに至ったが,一方で諸英語変種 (World Englishes) へと分裂しているのも事実もあり,将来求心力を維持できるのだろうか,と議論される.ある論者はラテン語と同じ足跡をたどることは間違いないという予想を立て,別の論者はラテン語と英語では歴史的状況が異なり単純には比較できないとみる.

両言語の比較に基づいた議論をする場合,当然ながら,歴史的事実を正確につかんでおくことが重要である.しかし,とりわけラテン語に関して,大きな誤解が広まっているのではないか.ラテン語がロマンス諸語へ分裂したと表現する場合,前提とされているのは,ラテン語がそれ以前には一枚岩だったということである.ところが,話し言葉に関する限り,ラテン語はロマンス諸語へ分裂する以前から各地で地方方言が用いられていたのであり,ある意味では「ロマンス諸語への分裂」は常に起こっていたことになる.ラテン語が一枚岩であるというのは,あくまで書き言葉に関する言説なのである.McArthur (9--10) は,"The Latin fallacy" という1節でこの誤解に対して注意を促している.

Between a thousand and two thousand years ago the language of the Romans was certainly central in the development of the entities we now call 'the Romance languages'. In some important sense, Latin drifted among the Lusitani into 'Portuguese', among the Dacians into 'Romanian', among the Gauls and Franks into 'French', and so on. It is certainly seductive, therefore, to wonder whether American English might become simply 'American', and be, as Burchfield has suggested, an entirely distinct language in a century's time from British English.

There is only one problem. The language used as a communicative bond among the citizens of the Roman Empire was not the Latin recorded in the scrolls and codices of the time. The masses used 'popular' (or 'vulgar') Latin, and were apparently extremely diverse in their use of it, intermingled with a wide range of other vernaculars. The Romance languages derive, not from the gracious tongue of such literati as Cicero and Virgil, but from the multifarious usages of a population most of whom were illiterati.

'Classical' Latin had quite a different history from the people's Latin. It did not break up at all, but as a language standardized by manuscript evolved in a fairly stately fashion into the ecclesiastical and technical medium of the Middle Ages, sometimes known as 'Neo-Latin'. As Walter Ong has pointed out in Orality and Literacy (1982), this 'Learned Latin' survived as a monolith through sheer necessity, because Europe was 'a morass of hundreds of languages and dialects, most of them never written to this day'. Learned Latin derived its power and authority from not being an ordinary language. 'Devoid of baby talk' and 'a first language to none of its users', it was 'pronounced across Europe in often mutually unintelligible ways but always written the same way' (my italics).

The Latin analogy as a basis for predicting one possible future for English is not therefore very useful, if the assumption is that once upon a time Latin was a mighty monolith that cracked because people did not take proper care of it. That is fallacious. Interestingly enough, however, a Latin analogy might serve us quite well if we develop the idea of a people's Latin that was never at any time particularly homogeneous, together with a text-bound learned Latin that became and remained something of a monolith because European society needed it that way.

引用の最後にもある通り,この「ラテン語に関する誤謬」に陥らないように注意した上で,改めてラテン語の来し方と英語の行く末を比較してみるとき,両言語を取り巻く歴史社会言語学的状況にはやはり共通点があるように思われる.英語の未来を予想しようとする際の不確定要素の1つは,世界がリンガ・フランカとしての英語をどれくらい求めているかである.その欲求が強く存在している限り,少なくとも書き言葉においては,ラテン語がそうだったように,共通語的な役割を維持していくのではないか.

・ McArthur, Tom. "The English Languages?" English Today 11 (1987): 9--11.

2021-08-03 Tue

■ #4481. 英語史上,2度借用された語の位置づけ [lexicography][lexicology][borrowing][loan_word][latin][lexeme]

英語史上,2度借用された語というものがある.ある時代にあるラテン語単語などが借用された後,別の時代にその同じ語があらためて借用されるというものである.1度目と2度目では意味(および少し形態も)が異なっていることが多い.

例えば,ラテン語 magister は,古英語の早い段階で借用され,若干英語化した綴字 mægester で用いられていたが,10世紀にあらためて magister として原語綴字のまま受け入れられた (cf. 「#1895. 古英語のラテン借用語の綴字と借用の類型論」 ([2014-07-05-1])).

中英語期と初期近代英語期からも似たような事例がみられる.fastidious というラテン語単語は1440年に「傲岸不遜な」の語義で借用されたが,その1世紀後には「いやな,不快な」の語義で用いられている(後者は現代の「気難しい,潔癖な」の語義に連なる).また,Chaucer は artificial, declination, hemisphere を天文学用語として導入したが,これらの語の現在の非専門的な語義は,16世紀の再借用時の語義に基づく.この中英語期からの例については,Baugh and Cable (222--23) が次のような説明を加えている.

A word when introduced a second time often carries a different meaning, and in estimating the importance of the Latin and other loanwords of the Renaissance, it is just as essential to consider new meanings as new words. Indeed, the fact that a word had been borrowed once before and used in a different sense is of less significance than its reintroduction in a sense that has continued or been productive of new ones. Thus the word fastidious is found once in 1440 with the significance 'proud, scornful,' but this is of less importance than the fact that both More and Elyot use it a century later in its more usual Latin sense of 'distasteful, disgusting.' From this, it was possible for the modern meaning to develop, aided no doubt by the frequent use of the word in Latin with the force of 'easily disgusted, hard to please, over nice.' Chaucer uses the words artificial, declination, and hemisphere in astronomical sense but their present use is due to the sixteenth century; and the word abject, although found earlier in the sense of 'cast off, rejected,' was reintroduced in its present meaning in the Renaissance.

もちろん見方によっては,上記のケースでは,同一単語が2度借用されたというよりは,既存の借用語に対して英語側で意味の変更を加えたというほうが適切ではないかという意見はあるだろう.新旧間の連続性を前提とすれば「既存語への変更」となり,非連続性を前提とすれば「2度の借用」となる.しかし,Baugh and Cable も引用中で指摘しているように,語源的には同一のラテン語単語にさかのぼるとしても,英語史の観点からは,実質的には異なる時代に異なる借用語を受け入れたとみるほうが適切である.

OED のような歴史的原則に基づいた辞書の編纂を念頭におくと,fastidious なり artificial なりに対して,1つの見出し語を立て,その下に語義1(旧語義)と語義2(新語義)などを配置するのが常識的だろうが,各時代の話者の共時的な感覚に忠実であろうとするならば,むしろ fastidious1 と fastidious2 のように見出し語を別に立ててもよいくらいのものではないだろうか.後者の見方を取るならば,後の歴史のなかで旧語義が廃れていった場合,これは廃義 (dead sense) というよりは廃語 (dead word) というべきケースとなる.いな,より正確には廃語彙項目 (dead lexical item; dead lexeme) と呼ぶべきだろうか.

この問題と関連して「#3830. 古英語のラテン借用語は現代まで地続きか否か」 ([2019-10-22-1]) も参照.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2021-07-28 Wed

■ #4475. Love's Labour's Lost より語源的綴字の議論のくだり [shakespeare][mulcaster][etymological_respelling][popular_passage][inkhorn_term][latin][loan_word][spelling_pronunciation][silent_letter][orthography]

なぜ doubt の綴字には発音しない <b> があるのか,というのは英語の綴字に関する素朴な疑問の定番である.これまでも多くの記事で取り上げてきたが,主要なものをいくつか挙げておこう.

・ 「#1943. Holofernes --- 語源的綴字の礼賛者」 ([2014-08-22-1])

・ 「#3333. なぜ doubt の綴字には発音しない b があるのか?」 ([2018-06-12-1])

・ 「#3227. 講座「スペリングでたどる英語の歴史」の第4回「doubt の <b>--- 近代英語のスペリング」」 ([2018-02-26-1])

・ 「圧倒的腹落ち感!英語の発音と綴りが一致しない理由を専門家に聞きに行ったら,犯人は中世から近代にかけての「見栄」と「惰性」だった.」(DMM英会話ブログさんによるインタビュー)

doubt の <b> の問題については,16世紀末からの有名な言及がある.Shakespeare による初期の喜劇 Love's Labour's Lost のなかで,登場人物の1人,衒学者の Holofernes (一説には実在の Richard Mulcaster をモデルとしたとされる)が <b> を発音すべきだと主張するくだりがある.この喜劇は1593--94年に書かれたとされるが,当時まさに世の中で inkhorn_term を巡る論争が繰り広げられていたのだった(cf. 「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1])).この時代背景を念頭に Holofernes の台詞を読むと,味わいが変わってくる.その核心部分は「#1943. Holofernes --- 語源的綴字の礼賛者」 ([2014-08-22-1]) で引用したが,もう少し長めに,かつ1623年の第1フォリオから改めて引用したい(Smith 版の pp. 195--96 より).

Actus Quartus.

Enter the Pedant, Curate and Dull.

Ped. Satis quid sufficit.

Cur. I praise God for you sir, your reasons at dinner haue beene sharpe & sententious: pleasant without scurrillity, witty without affection, audacious without impudency, learned without opinion, and strange without heresie: I did conuerse this quondam day with a companion of the Kings, who is intituled, nominated, or called, Dom Adriano de Armatha.

Ped. Noui hominum tanquam te, His humour is lofty, his discourse peremptorie: his tongue filed, his eye ambitious, his gate maiesticall, and his generall behauiour vaine, ridiculous, and thrasonical. He is too picked, too spruce, to affected, too odde, as it were, too peregrinat, as I may call it.

Cur. A most singular and choise Epithat,

Draw out his Table-booke,

Ped. He draweth out the thred of his verbositie, finer than the staple of his argument. I abhor such phnaticall phantasims, such insociable and poynt deuise companions, such rackers of ortagriphie, as to speake dout fine, when he should say doubt; det, when he shold pronounce debt; d e b t, not det: he clepeth a Calf, Caufe: halfe, hawfe; neighbour vocatur nebour; neigh abreuiated ne: this is abhominable, which he would call abhominable: it insinuateth me of infamie: ne inteligis domine, to make franticke, lunaticke?

Cur. Laus deo, bene intelligo.

Ped. Bome boon for boon prescian, a little scratched, 'twill serue.

第1フォリオそのものからの引用なので,読むのは難しいかもしれないが,全体として Holofernes (= Ped.) の衒学振りが,ラテン語使用(というよりも乱用)からもよく伝わるだろう.当時実際になされていた論争をデフォルメして描いたものと思われるが,それから400年以上たった現在もなお「なぜ doubt の綴字には発音しない <b> があるのか?」という素朴な疑問の形で議論され続けているというのは,なんとも息の長い話題である.

・ Smith, Jeremy J. Essentials of Early English. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2005.

2021-05-16 Sun

■ #4402. 進行形の起源と発達 [verb][participle][gerund][syntax][aspect][contact][latin][french][celtic][khelf_hel_intro_2021]

目下開催中の「英語史導入企画2021」より今日紹介するコンテンツは,昨日学部生より公表された「先生,進行形の ing って現在分詞なの?動名詞なの?」です.動詞の進行形の歴史をひもとき,形式上は現在分詞の構文の流れを汲んでいるが,機能上は動名詞の構文の流れを汲んでいることを指摘したコンテンツです.

be + -ing として表現される進行形 (progressive form) の起源と発達については,英語史上多くの議論がなされてきました.諸説紛々としており,今なお定説と呼べるものがあるかどうかも怪しい状況です.研究史については Mustanoja (584--90) によくまとまっています.以下,それに依拠して概略を述べましょう.

古英語には,現代英語の be + -ing の前駆体というべき構文として wesan/beon + -ende がありました.当時の現在分詞は -ende という形態を取っており,後に込み入った事情で -ing に置き換えられたという経緯があります(cf. 「#2421. 現在分詞と動名詞の協働的発達」 ([2015-12-13-1]),「#2422. 初期中英語における動名詞,現在分詞,不定詞の語尾の音韻形態的混同」 ([2015-12-14-1])).古英語の wesan/beon + -ende は,確かに継続を含意する文脈で用いられることもありましたが,そうでないことも多く,機能的には後世の進行形に直接つながるものかどうかは不確かです.また,起源としてはラテン語の対応する構文の模倣であるとも言われています.中英語期に入ると,この構文はむしろ目立たなくなります.方言によっても生起頻度に偏りがみられました.しかし,中英語後期にかけて着実に成長し始め,近現代英語の進行形に連なる流れを作り出しました.典型的に継続を表わす現代的な用法が発達し確立したのは,16世紀以降のことです.

進行形の起源と発達をざっと概観しましたが,その詳細は実に複雑で,英語史研究上,喧喧諤諤の議論が繰り広げられてきました.古英語の対応構文からの地続きの発達であるという説もあれば,後世の「on + 動名詞」の構文からの派生であるという説もあります.この2つの説を組み合わせた穏当な第3の説も提案されており,これが今広く受け入れられている説となっているようです.

他言語からの影響による発達という議論も多々あります.上述の通り,古英語の wesan/beon + -ende はラテン語の対応構文を模倣したものであるというのが有力な説です.中英語期での使用については,古フランス語の対応構文の影響も疑われています.さらに,ケルト語影響説まで提案されています(cf. 「#3754. ケルト語からの構造的借用,いわゆる「ケルト語仮説」について」 ([2019-08-07-1])).

進行形は,このように英語史研究の魅力的な題材であり続けています.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2021-05-15 Sat

■ #4401. 「英語語彙の三層構造」の神話と脱神話化 [loan_word][french][latin][lexicology][lexical_stratification][language_myth][khelf_hel_intro_2021][hellog_entry_set][etymological_respelling]

「英語史導入企画2021」のために昨日公表されたコンテンツは,大学院生による「Synonyms at Three Levels」でした.これは何のことかというと「英語語彙の三層構造」の話題です.「恐れ,恐怖」を意味する英単語として fear -- terror -- trepidation などがありますが,これらの類義語のセットにはパターンがあります.fear は易しい英語本来語で,terror はやや難しいフランス語からの借用語,trepidation は人を寄せ付けない高尚な響きをもつラテン語からの借用語です.英語の歴史を通じて,このような類義語が異なる時代に異なる言語から供給され語彙のなかに蓄積していった結果が,三層構造というわけです.上記コンテンツのほか,「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]) や「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1]) より具体例を覗いてみてください.

さて,「英語語彙の三層構造」は英語史では定番の話題です.定番すぎて神話化しているといっても過言ではありません.そこで本記事では,あえてその脱神話化を図ろうと思います.以下は英語史上級編の話題になりますのでご注意ください.すでに「#2643. 英語語彙の三層構造の神話?」 ([2016-07-22-1]) や「#2279. 英語語彙の逆転二層構造」 ([2015-07-24-1]) でも部分的に取り上げてきた話題ですが,今回は上記コンテンツに依拠しながら fear -- terror -- trepidation という3語1組 (triset) に焦点を当てて議論してみます.

(1) コンテンツ内では,この triset のような「類例は枚挙に遑がない」と述べられています.私自身も英語史概説書や様々な記事で同趣旨の文章をたびたび書いてきたのですが,実は「遑」はかなりあるのではないかと考えています.「類例をひたすら挙げてみて」と言われてもたいした数が挙がらないのが現実です.しかも「きれい」な例を挙げなさいと言われると,これは相当に難問です.

(2) 今回の fear - terror - trepidation はかなり「きれい」な例のようにみえます.しかしどこまで本当に「きれい」かというのが私の問題意識です.一般の英語辞書の語源欄では確かに terror はフランス語から,trepidation はラテン語から入ったとされています.おおもとは両語ともラテン語にさかのぼり,前者は terrōrem,後者は trepidātiō が語源形となります(ちなみに,ともに印欧語根は *ter- にさかのぼり共通です).terror はもともとラテン語の単語だったけれどもフランス語を経由して英語に入ってきたという意味において「フランス語からの借用語」と表現することは,語源記述の慣習に沿ったもので,まったく問題はありません.

ところが,OED の terror の語源記述をみると "Of multiple origins. Partly a borrowing from French. Partly a borrowing from Latin." とあります.「フランス語からの借用語である」とは断定していないのです.語源学的にいって,この種の単語はフランス語から入ったのかラテン語から入ったのか曖昧なケースが多く,研究史上多くの議論がなされてきました.この議論に関心のある方はこちらの記事セットをご覧ください.

難しい問題ですが,私としては terror をひとまずフランス借用語と解釈してよいだろうとは考えています.その根拠の1つは,中英語での初期の優勢な綴字がフランス語風の <terrour> だったことです.ラテン語風であれば <terror> となるはずです.逆にいえば,現代英語の綴字 <terror> は,後にラテン語綴字を参照した語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の例ということになります.要するに,現代の terror は,後からラテン語風味を吹き込まれたフランス借用語ということではないかと考えています.

この terror の出自の曖昧さを考慮に入れると,問題の triset は典型的な「英語 -- フランス語 -- ラテン語」の型にがっちりはまる例ではないことになります.少なくとも例としての「きれいさ」は,100%から80%くらいまでに目減りしたように思います.

(3) 次に trepidation についてですが,OED によればラテン語から直接借用されたものとあります.一方,研究社の『英語語源辞典』は,フランス語 trépidation あるいはラテン語 trepidātiō(n)- に由来するものとし,慎重な姿勢をとっています.なお,この単語の英語での初出は1605年ですが,OED 第2版の情報によると,フランス語ではすでに15世紀に trépidation が文証されているということです.terror に続き trepidation の出自にも曖昧なところが出てきました.問題の triset の「きれいさ」は,80%からさらに70%くらいまで下がった感じがします.

(4) コンテンツ内でも触れられているように,三層構造の中層を占めるフランス借用語層は,実際には下層を占める英語本来語層とも融合していることが多いです (ex. clear, cry, fool, humour, safe) .きれいな三層構造を構成しているというよりは,英仏語の層をひっくるめたり,仏羅語の層をひっくるめたりして,二層構造に近くなるという側面があります.

さらに「逆転二層構造」と呼ぶべき典型的でない例も散見されます.例えば,同じ「谷」でも中層を担うはずのフランス借用語 valley は日常的な響きをもちますが,下層を担うはずの英語本来語 dale はかえって文学的で高尚な響きをもつともいえます.action/deed, enemy/foe, reward/meed も類例です(cf. 「#2279. 英語語彙の逆転二層構造」 ([2015-07-24-1])).英語語彙の三層構造は,本当のところは評判ほど「きれい」でもないのです.

以上,「英語語彙の三層構造」の脱神話化を図ってみました.私も全体論としての「英語語彙の三層構造」を否定する気はまったくありません.私自身いろいろなところで書いてきましたし,今後も書いてゆくつもりです.ただし,そこに必ずしも「きれい」ではない側面があることには留意しておきたいと思うのです.

英語語彙の三層構造の諸側面に関心をもった方はこちらの記事セットをどうぞ.

2021-05-11 Tue

■ #4397. star で英語史 [lexical_stratification][latin][lexicology][astrology][sound_change][vowel][etymology][loan_word][hellog_entry_set][khelf_hel_intro_2021]

年度初めから5月末まで開催中の「英語史導入企画2021」も後半戦に入ってきました.昨日大学院生より公表されたコンテンツは「ことばの中にひそむ「星」」です.star や astrology (占星術)を中心とする英単語の語源・語誌エッセーで,本企画の趣旨にピッタリです.まさかの展開で,話しが disaster, consider, desire, influenza, disposition にまで及んでいきます.きっと英単語の語源に興味がわくことと思います.

星好きの私も,星(座)に関係する話題をいくつか書いてきましたので紹介します.まず,上記コンテンツの関心と重なる star の語源について「#1602. star の語根ネットワーク」 ([2013-09-15-1]) をどうぞ.

英語 star とラテン語 stella (cf. フランス語 etoile)を比べると r と l の違いがありますが,これはどういうことかと疑問に思ったら「#1597. star と stella」 ([2013-09-10-1]) をご覧ください.

次に star の形態についてです.古英語では steorra,中英語では sterre などの綴字で現われるのが普通で,母音は /a/ ではなく /e/ だったと考えられます.なぜこれが /a/ へと変化し,語の綴字としてもそれを反映して star とされたのでしょうか.実は,現代英語の heart, clerk, Derby, sergeant などの発音と綴字の問題にも関わるおもしろいトピックです.「#2274. heart の綴字と発音」 ([2015-07-19-1]) をどうぞ.

占星術といえば黄道十二宮や星座の名前が関連してきます.ここに,英語史を通じて育まれてきた語彙階層 (lexical_stratification) の具体例を観察することができます.「うお座」は the Fish ですが,学術的に「双魚宮」という場合には Pisces となりますね.ぜひ「#3846. 黄道十二宮・星座名の語彙階層」 ([2019-11-07-1]) をお読みください.また,英語での星座名の一覧は「#3707. 88星座」 ([2019-06-21-1]) より.

star 周りの素材のみを用いて英語史することが十分に可能です.以上すべてをひっくるめて読みたい場合は,こちらの記事セットを.

2021-05-08 Sat

■ #4394. 「疑いの2」の英語史 [khelf_hel_intro_2021][etymology][comparative_linguistics][indo-european][oe][lexicology][loan_word][germanic][italic][latin][french][edd][grimms_law][etymological_respelling][lexicology][semantic_field]

印欧語族では「疑い」と「2」は密接な関係にあります.日本語でも「二心をいだく」(=不忠な心,疑心をもつ)というように,真偽2つの間で揺れ動く心理を表現する際に「2」が関わってくるというのは理解できる気がします.しかし,印欧諸語では両者の関係ははるかに濃密で,語形成・語彙のレベルで体系的に顕在化されているのです.

昨日「英語史導入企画2021」のために大学院生より公開された「疑いはいつも 2 つ!」は,この事実について比較言語学の観点から詳細に解説したコンテンツです.印欧語比較言語学や語源の話題に関心のある読者にとって,おおいに楽しめる内容となっています.

上記コンテンツを読めば,印欧諸語の語彙のなかに「疑い」と「2」の濃密な関係を見出すことができます.しかし,ここで疑問が湧きます.なぜ印欧語族の一員である英語の語彙には,このような関係がほとんど見られないのでしょうか.コンテンツの注1に,次のようにありました.

現代の標準的な英語にはゲルマン語の「2」由来の「疑い」を意味する単語は残っていないが,English Dialect Dictionary Online によればイングランド中西部のスタッフォードシャーや西隣のシュロップシャーの方言で tweag/tweagle 「疑い・当惑」という単語が生き残っている.

最後の「生き残っている」にヒントがあります.コンテンツ内でも触れられているとおり,古くは英語にもドイツ語や他のゲルマン語のように "two" にもとづく「疑い」の関連語が普通に存在したのです.古英語辞書を開くと,ざっと次のような見出し語を見つけることができました.

・ twēo "doubt, ambiguity"

・ twēogende "doubting"

・ twēogendlic "doubtful, uncertain"

・ twēolic "doubtful, ambiguous, equivocal"

・ twēon "to doubt, hesitate"

・ twēonian "to doubt, be uncertain, hesitate"

・ twēonigend, twēoniendlic "doubtful, expressing doubt"

・ twēonigendlīce "perhaps"

・ twēonol "doubtful"

・ twīendlīce "doubtingly"

これらのいくつかは初期中英語期まで用いられていましたが,その後,すべて事実上廃用となっていきました.その理由は,1066年のノルマン征服の余波で,これらと究極的には同根語であるラテン語やフランス語からの借用語に,すっかり置き換えられてしまったからです.ゲルマン的な "two" 系列からイタリック的な "duo" 系列へ,きれいさっぱり引っ越ししたというわけです(/t/ と /d/ の関係についてはグリムの法則 (grimms_law) を参照).現代英語で「疑いの2」を示す語例を挙げてみると,

doubt, doubtable, doubtful, doubting, doubtingly, dubiety, dubious, dubitate, dubitation, dubitative, indubitably

など,見事にすべて /d/ で始まるイタリック系借用語です.このなかに dubious のように綴字 <b> を普通に /b/ と発音するケースと,doubt のように <b> を発音しないケース(いわゆる語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling))が混在しているのも英語史的にはおもしろい話題です (cf. 「#3333. なぜ doubt の綴字には発音しない b があるのか?」 ([2018-06-12-1])).

このようにゲルマン系の古英語単語が中英語期以降にイタリック系の借用語に置き換えられたというのは,英語史上はありふれた現象です.しかし,今回のケースがおもしろいのは,単発での置き換えではなく,関連語がこぞって置き換えられたという点です.語彙論的にはたいへん興味深い現象だと考えています (cf. 「#648. 古英語の語彙と廃語」 ([2011-02-04-1])).

こうして現代英語では "two" 系列で「疑いの2」を表わす語はほとんど見られなくなったのですが,最後に1つだけ,その心を受け継ぐ表現として be in/of two minds about sb/sth (= to be unable to decide what you think about sb/sth, or whether to do sth or not) を紹介しておきましょう.例文として I was in two minds about the book. (= I didn't know if I liked it or not) など.

2021-04-24 Sat

■ #4380. 英語のルーツはラテン語でもドイツ語でもない [indo-european][language_family][language_myth][latin][german][germanic][comparative_linguistics][khelf_hel_intro_2021]

新年度初めのイベントとして立ち上げた「英語史導入企画2021」では,日々学生から英語史に関するコンテンツがアップされてくる.昨日は院生による「英語 --- English --- とは」が公表された.英語のルーツが印欧祖語にさかのぼることを紹介する,まさに英語史導入コンテンツである.

本ブログを訪れている読者の多くにとっては当前のことと思われるが,英語はゲルマン語派に属する1言語である.しかし,一般には英語がラテン語(イタリック語派の1言語)から生まれたとする誤った理解が蔓延しているのも事実である.ラテン語は近代以降すっかり衰退してきたとはいえ,一種の歴史用語として抜群の知名度を誇っており,同じ西洋の言語として英語と関連があるにちがいないと思われているからだろう.

一方,少し英語史をかじると,英語にはラテン語からの借用語がやたら多いということも聞かされるので,両言語の語彙には共通のものが多い,すなわち共通のルーツをもつのだろう,という実はまったく論理的でない推論が幅を利かせることにもなりやすい.

英語はゲルマン系の言語であるということを聞いたことがあると,もう1つ別の誤解も生じやすい.英語はドイツ語から生まれたという誤解だ.英語でドイツ語を表わす German とゲルマン語を表わす Germanic が同根であることも,この誤解に拍車をかける.

本ブログの読者の多くにとって,上記のような誤解が蔓延していることは信じられないことにちがいない.では,そのような誤解を抱いている人を見つけたら,どのようにその誤解を解いてあげればよいのか.簡単なのは,上記コンテンツでも示してくれたように印欧語系統図を提示して説明することだ.

しかし,誤解の持ち主から,そのような系統図は誰が何の根拠に基づいて作ったものなのかと逆質問されたら,どう答えればよいだろうか.これは実のところ学術的に相当な難問なのである.19世紀の比較言語学者たちが再建 (reconstruction) という手段に訴えて作ったものだ,と仮に答えることはできるだろう.しかし,再建形が正しいという根拠はどこにあるかという理論上の真剣な議論となると,もう普通の研究者の手には負えない.一種の学術上の信念に近いものでもあるからだ.であるならば,「英語のルーツは○○語でなくて△△語だ」という主張そのものも,存立基盤が危ういということにならないだろうか.突き詰めると,けっこう恐い問いなのだ.

「英語史導入企画2021」のキャンペーン中だというのに,小難しい話しをしてしまった.むしろこちらの方に興味が湧いたという方は,以下の記事などをどうぞ.

・ 「#369. 言語における系統と影響」 ([2010-05-01-1])

・ 「#371. 系統と影響は必ずしも峻別できない」 ([2010-05-03-1])

・ 「#862. 再建形は実在したか否か (1)」 ([2011-09-06-1])

・ 「#863. 再建形は実在したか否か (2)」 ([2011-09-07-1])

・ 「#2308. 再建形は実在したか否か (3)」 ([2015-08-22-1])

・ 「#864. 再建された言語の名前の問題」 ([2011-09-08-1])

・ 「#2120. 再建形は虚数である」 ([2015-02-15-1])

・ 「#3146. 言語における「遺伝的関係」とは何か? (1)」 ([2017-12-07-1])

・ 「#3147. 言語における「遺伝的関係」とは何か? (2)」 ([2017-12-08-1])

・ 「#3148. 言語における「遺伝的関係」の基本単位は個体か種か?」 ([2017-12-09-1])

・ 「#3149. なぜ言語を遺伝的に分類するのか?」 ([2017-12-10-1])

・ 「#3020. 帝国主義の申し子としての比較言語学 (1)」 ([2017-08-03-1])

・ 「#3021. 帝国主義の申し子としての比較言語学 (2)」 ([2017-08-04-1])

2021-04-20 Tue

■ #4376. 現代日本で英語と向き合っている生徒・学生と17世紀イングランドでラテン語と向き合っていた庶民 [renaissance][emode][loan_word][borrowing][latin][japanaese][contrastive_linguistics][inkhorn_term][khelf_hel_intro_2021]

4月5日にスタートした「英語史導入企画2021」も,3週目に突入しました.学部・院のゼミ生を総動員しての,5月末まで続く少々息の長い企画なのですが,本ブログ読者の皆さんにも懲りずにお付き合いのほどよろしくお願い申し上げます.毎日,コンテンツを提供する学生のガッツを感じながら,私自身がおおいにインスピレーションをゲットしています.年度初めとして,なかなかフレッシュでナイスなオープニングです.

さて,上の段落では,いやらしいほどにカタカナ語を使い倒してみました.英語が嫌いな人,横文字が嫌いな人には,ケッと吐いて捨てたくなるような文章だろうと思います(うーむ,我ながら軽薄な文章).昨日,本企画ために院生よりアップされたコンテンツは「英語嫌いな人のための英語史」と題する,このカタカナ語嫌いに寄り添った考察です.その冒頭の2つの段落の出だしが,何とも歯切れよく心地よいですね.

「一生英語を使わなくてもいい環境で暮らしてやる」……このような恨みつらみのこもった台詞は,英語嫌いの人間ならば一度は発したことがあるだろう.そして,何を隠そう,十年ほど前,中学生・高校生だったころの筆者自身が毎日のようにこぼしていた言葉でもあった.

英語嫌いの人間が辟易するのは,まずもって,世の中に氾濫している横文字の多さであるだろう.レガシー,コミット,アカウンタビリティ……なぜそこで英語を(あるいは英語由来の和製英語を)使わなければならないのかと,ニュースなどを見ながら突っ込みたくなる日々である.

これは読みたくなるコンテンツではないでしょうか.内容としては,現代日本で英語と向き合っている生徒・学生と,17世紀イングランドでラテン語と向き合っていた庶民とを,空間・時間を超えて比較した英語史の好コンテンツとなっています.

現代日本語におけるカタカナ語とルネサンス期イングランドのラテン借用語を巡る比較対照は,対照言語史 (contrastive_language_history) の観点から興味の尽きないテーマです.一般に2つのものを比較しようとする際には,共通点だけでなく相違点に留意することも重要です.上記コンテンツでは,意図的に両者の共通点を拾い出して近づけて見せているわけですが,あえて相違点に注目することで,先の共通点の意義を浮かび上がらせることができます.以下に2点指摘しておきましょう.

1点目.現代日本で英語と向き合っている生徒・学生,とりわけ「英語なんて嫌い」と吐き捨てるタイプと,17世紀イングランドでラテン語と向き合っていた庶民とでは,各言語に対する思いがかなり異なります.「英語なんて嫌い」の背景には,逆説的に英語に対する「憧れ」があるのではないかというコンテンツでの指摘は当たっていると私も思います.しかし,17世紀イングランドの庶民はラテン語を「嫌い」と吐き捨ててはいなかったでしょう.ラテン語は,もっと純粋な「憧れ」,手に届かないところにいる「スター」に近いものではなかったでしょうか.

両者の違いは,端的にいえば,むりやり学ばされているか否かにあります.現代日本では,たとえ英語が「憧れ」だったとしても,義務教育で強制的に学ばされるという意味では,現実の学習上の「苦労」がセットになっています.学校で学ぶべき「科目」となっていては,好きなものも好きではなくなるはずです.17世紀イングランドでは,庶民にとってラテン語学習はおろか教育の機会そのものがまだ高嶺の花であり,現実の学習上の「苦労」とは無縁なために,「憧れ」は純然たる憧れとして生き延び得たのです.

2点目は,17世紀イングランドではラテン借用語が inkhorn_term として批判されたというのは事実ですが,批判の主は,若い生徒・学生でもなければ庶民でもなく,バリバリの知識人でした.Sir John Cheke (1514--57) のようなケンブリッジ大学の古典語教授が,借用語を批判していたほどなのです.この状況は,どう控えめにみても,日本の英語嫌いの生徒・学生がカタカナ語に悪態をついているのとは比較できないように思われます.

もちろん,2つのものを比較対照するときに,共通点を重視して「比較」の議論にもっていくか,相違点を重視して「対照」の議論にもっていくかは,論者の方針次第でもあり,言ってしまえばレトリックの問題でもあります.いずれにしても比較する場合には相違点に,対照する場合には共通点に注意しておくと考察が深まる,ということを述べておきましょう.

関連する話題は,本ブログとしては「#1999. Chuo Online の記事「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」」 ([2014-10-17-1]),「#2977. 連載第6回「なぜ英語語彙に3層構造があるのか? --- ルネサンス期のラテン語かぶれとインク壺語論争」」 ([2017-06-21-1]) その他の記事で扱ってきました.いろいろとリンクを張っているので,是非そちらをどうぞ.

2021-04-18 Sun

■ #4374. No. 1 を "number one" と読むのは英語における「訓読み」の例である [abbreviation][latin][spelling][japanese][kanji][sobokunagimon][grammatology][khelf_hel_intro_2021]

英語の話題を扱うのに,日本語的な「訓読み」(や「音読み」)という用語を持ち出すのは奇異な印象を与えるかもしれないが,実は英語にも音訓の区別がある.そのように理解されていないだけで,現象としては普通に存在するのだ.表記のように No. 1 という表記を,英語で "number one" と読み下すのは,れっきとした訓読みの例である.

議論を進める前に,そもそもなぜ "number one" が No. 1 と表記されるのだろうか.多くの人が不思議に思う,この素朴な疑問については,「英語史導入企画2021」の昨日のコンテンツ「Number の略語が nu.ではなく, no.である理由」に詳しいので,ぜひ訪問を.本ブログでも「#750. number の省略表記がなぜ no. になるか」 ([2011-05-17-1]) や「#4185. なぜ number の省略表記は no. となるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版」 ([2020-10-11-1]) で取り上げてきたので,こちらも確認していただきたい.

さて,上記のコンテンツより,No. 1 という表記がラテン語の奪格形 numerō の省略表記に由来することが確認できたことと思う.英語にとって外国語であるラテン語の慣習的な表記が英語に持ち越されたという意味で,No. 1 は見映えとしては完全によそ者である.しかし,その意味を取って自言語である英語に引きつけ,"number one" と読み下しているのだから,この読みは「訓読み」ということになる.

これは「昨日」「今日」「明日」という漢語(外国語である中国語の複合語)をそのまま日本語表記にも用いながらも,それぞれ「きのう」「きょう」「あした」と日本語に引きつけて読み下すのと同じである.日本語ではこれらの表記に対してフォーマルな使用域で「さくじつ」「こんにち」「みょうにち」という音読みも行なわれるが,英語では No. 1 をラテン語ばりに "numero unus" などと「音読み」することは決してない.この点においては英日語の比較が成り立たないことは認めておこう.

しかし,原理的には No. 1 を "number one" と読むのは,「明日」を「あした」と読むのと同じことであり,要するに「訓読み」なのである.この事実を文字論の観点からみれば,No. も 1 も,ここでは表音文字ではなく表語文字として,つまり漢字のようなものとして機能している,と言えばよいだろうか.漢字の音訓に慣れた日本語使用者にとって,No. 1 問題はまったく驚くべき問題ではないのである.

関連して「#1042. 英語における音読みと訓読み」 ([2012-03-04-1]) も参照.

2021-04-08 Thu

■ #4364. 綴字も発音も意味もややこしい desert, dessert, dissert [latin][french][prefix][etymology][diatone][khelf_hel_intro_2021]

標題は,その派生語も含め,頭が混乱してくる単語群です.綴字はややこしく似ているし,その割には発音は同じだったり異なっていたりする.意味も似ているような,そうでないような.こういう単語は学習する上で実に困ります.このややこしさは語源を遡ってもたいして解消しないのですが,新年度の英語史導入キャンペーン期間中ということもあり,歴史的にみてみたいと思います(cf. 「#4357. 新年度の英語史導入キャンペーンを開始します」 ([2021-04-01-1])).

まずは,もっとも問題がなさそうで,知らなくてもよいレベルの単語である dissert v. /dɪˈsəːt/ から行きましょう.「論じる」を意味する動詞で,辞書では《古風》とのレーベルが貼られています.この単語のように綴字で <s> が重複する場合には,原則として無声音の /s/ となります(しかし,以下に述べるように,すぐに例外が現われます).この動詞から派生した名詞 dissertation 「学術論文(特に博士論文)」は知っておいてもよい単語ですね.

語源としては,ラテン語で「論じる」を意味する動詞 dissertāre に遡ります.強意の接頭辞 dis- に,語幹 serere (言葉をつなぐ,作文する)から派生した反復形をつなげたもので,「しっかり言葉をつなぎあわせる」ほどが原義です(cf. 同語幹より series も).

次に「デザート」を意味する dessert /dɪˈzəːt/も馴染み深い名詞だと思います.<ss> の綴字ですが,上記の早速の例外で,有声音 /z/ で発音されます.この単語は,フランス語の動詞 desservir (供した食事を片付ける)の過去分詞形に由来します.つまり「膳を下げられた」後に出されるもの,まさに「食後のデザート」なわけです.フランス語の除去の接頭辞 des- に servir (英語にも serve として入り「食事を出す」の意)という語形成なので,納得です.

さらに次に進みます.「デザート」の dessert とまったく同じ発音ながらも,<s> が1つの desert なる厄介な単語があります.複雑な事情を整理するために,以下では,起源の異なる desert 1 と desert 2 の2種類を区別していきます.最初に desert 1 から話しましょう.desert 1 は「捨てる,放棄する」を意味する動詞です.例文として,She was deserted by her husband. (彼女は夫に捨てられた.)を挙げておきます.この動詞の語源はフランス語 déserter で,さらに遡るとラテン語 dēserere の反復形に行き着きます.語根は serere なので,上述の dissert とも共通ですが,今回の単語についている接頭辞は dis- ではなく de- です.つなげる (serere) ことを止める (de) という発想で「捨てる,見捨てる」というわけです.

そして,この動詞 desert 1 が,そのままの形態で形容詞化し,さらに名詞化したのが「捨てられた(地)」としての「砂漠」です.英語では名前動後 (diatone) の傾向により,「砂漠」としての desert の発音は,強勢が第1音節に移って /ˈdɛzət/ となるので要注意です.

desert 2 /dɪˈzəːt/ に移りましょう.こちらは名詞で「当然受けるべき賞罰」を意味します.上記のこれまでの語とはまったく異なる雰囲気ですが,これは別語源の deserve /dɪˈzəːv/ (?に値する)という動詞の過去分詞形に由来する名詞形だからです.当然のごとく値するべき物事,それが賞罰ということです.この元の deserve なる動詞はフランス語 deservir からの借用で,これ自身はラテン語 dēservīre に遡ります.今回の接頭辞 dē- は強意,語幹 servīre は「仕える」の意味で,後者は後に serve として英語に取り込まれました.「?に仕えることができるほどに相応しい」→「?に値する」といった意味の発展と考えられます.

さて,混乱しやすい単語群の語源を遡ることで,かえって混乱したかもしれません(悪しからず).なお,最後に取り上げた動詞 deserve は,なかなか使い方の難しい動詞でもあります.The report deserves careful consideration., He deserves to be locked up for ever for what he did., Several other points deserve mentioning. など取り得る補文のヴァリエーションも豊富です.意味的な観点から探ってもおもしろい動詞だと思います.意味的な観点から,昨日「英語史導入企画2021」にて大学院生によるコンテンツ「"You deserve it." と「自業自得」」が公表されました.こちらもご一読ください.

2021-03-06 Sat

■ #4331. Johnson の辞書の名詞を示す略号 n.s. [johnson][dictionary][lexicography][noun][adjective][verb][latin][terminology]

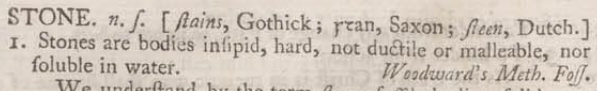

Samuel Johnson の辞書 A Dictionary of the English Language (1755) には,名詞を示す略号として,現在見慣れている n. ではなく n.s. が用いられている.名詞 stone の項目の冒頭をみてみよう.

見出し語に続いて,イタリック体で n. ʃ. が見える.(当時の小文字 <s> はいわゆる long <s> と呼ばれるもので,現在のものと異なるので注意.long <s> については,「#584. long <s> と graphemics」 ([2010-12-02-1]),「#2997. 1800年を境に印刷から消えた long <s>」 ([2017-07-11-1]),「#3869. ヨーロッパ諸言語が初期近代英語の書き言葉に及ぼした影響」 ([2019-11-30-1]),「#3875. 手書きでは19世紀末までかろうじて生き残っていた long <s>」 ([2019-12-06-1]) などを参照.)

n.s. は,伝統的に名詞を指した noun substantive の省略である.現在の感覚からはむしろ冗長な名前のように思われるかもしれないが,ラテン語文法の用語遣いからすると正当だ.ラテン語文法の伝統では,格により屈折する語類,すなわち名詞と形容詞をひっくるめて "noun" とみなしていた.後になって名詞と形容詞を別物とする見方が生まれ,前者は "noun substantive",後者は "noun adjective" と呼ばれることになったが,いずれもまだ "noun" が含まれている点では,以前からの伝統を引き継いでいるともいえる.Dixon (97) から関連する説明を引用しよう.

Early Latin grammars used the term 'noun' for all words which inflect for case. At a later stage, this class was divided into two: 'noun substantive' (for words referring to substance) and 'noun adjective' (for those relating to quality). Johnson had shortened the latter to just 'adjective' but retained 'noun substantive', hence his abbreviation n.s.

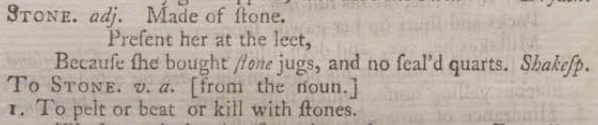

引用にもある通り,形容詞のほうは n.a. ではなく現代風に adj. としているので,一貫していないといえばその通りだ.形容詞 stone の項目をみてみよう.

ちなみに,ここには動詞 to stone の見出しも見えるが,品詞の略号 v.a. は,verb active を表わす.今でいう他動詞 (transitive verb) をそう呼んでいたのである.一方,自動詞 (intransitive verb) は,v.n. (= verb neuter) だった.

文法用語を巡る歴史的な問題については,「#1257. なぜ「対格」が "accusative case" なのか」 ([2012-10-05-1]),「#1258. なぜ「他動詞」が "transitive verb" なのか」 ([2012-10-06-1]),「#1520. なぜ受動態の「態」が voice なのか」 ([2013-06-25-1]),「#3307. 文法用語としての participle 「分詞」」 ([2018-05-17-1]),「#3983. 言語学でいう法 (mood) とは何ですか? (1)」 ([2020-03-23-1]),「#3984. 言語学でいう法 (mood) とは何ですか? (2)」 ([2020-03-24-1]),「#3985. 言語学でいう法 (mood) とは何ですか? (3)」 ([2020-03-25-1]),「#4317. なぜ「格」が "case" なのか」 ([2021-02-20-1]) などを参照.

・ Dixon, R. M. W. The Unmasking of English Dictionaries. Cambridge: CUP, 2018.

2021-03-02 Tue

■ #4327. 羅英辞書から英英辞書への流れ [latin][loan_word][coote][cawdrey][bullokar][lexicography][dictionary]

連日の記事で,英語史上の最初の英英辞書の誕生とその周辺について Dixon に拠りながら考察している (cf. 「#4324. 最初の英英辞書は Coote の The English Schoole-maister?」 ([2021-02-27-1]),「#4325. 最初の英英辞書へとつなげた Coote の意義」 ([2021-02-28-1]),「#4326. 最初期の英英辞書のラインは Coote -- Cawdrey -- Bullokar」 ([2021-03-01-1])) .英英辞書の草創期を形成するラインとして Mulcaster -- Coote -- Cawdrey -- Bullokar という系統をたどることができると示唆してきたが,Mulcaster 以前の前史にも注意を払う必要がある.Mulcaster 以前と以後も,辞書史的には連続体を構成しているからだ.

概略的に述べれば,確かに Mulcaster より前は bilingual な羅英辞書の時代であり,以後は monolingual な英英辞書の時代であるので,一見すると Mulcaster を境に辞書史的な飛躍があるように見えるかもしれない.しかし,後者を monolingual な英英辞書とは称しているものの,実態としては「難語辞書」であり,見出し語はラテン語からの借用語が圧倒的に多かったという点が肝心である.つまり,ラテン語の形態そのものではなくとも少々英語化した程度の「なんちゃってラテン単語」が見出しに立てられているわけであり,Coote -- Cawdrey -- Bullokar ラインの monolingual 辞書は,いずれも実態としては "1.5-lingual" 辞書とでもいうべきものだったのだ.つまり,Mulcaster 以後の英英辞書の流れも,それ以前からの羅英辞書の系統に連なるということである.

Dixon (42) に従い,15--16世紀の羅英辞書の系統を簡単に示そう.よく知られているのは,1430年辺りの部分的な写本版が残っている Hortus Vocabulorum である.1500年に出版され,27,000語ものラテン単語が意味別に掲載されている.英羅辞書については,1440年の写本版が知られている Promptorium Parvalorum sive Clericum が,1499年に出版され,以後1528年まで改訂されることとなった.

16世紀前半に存在感を示した羅英辞書は,The Dictionary of Sir Thomas Elyot knight (1538) である(タイトルが英語であるこに注意).これは先行する Hortus Vocabulorum の影響をほとんど受けておらず,むしろ Ambrogio Calepino の羅羅辞書をベースにしている (Dixon 43) .世紀の半ばの1565年に Bishop Thomas Cooper による羅英辞書 Thesaurus Linguae Romanae & Britannicae が出版され一世を風靡したが,世紀後半の1587年に Thomas Thomas により出版された羅英辞書 Dictionarium Linguae Latinae et Anglicanae にその地位を奪われていくことになった.そして,この Thomas Thomas の羅英辞書こそが,Mulcaster より後の Coote -- Cawdrey -- Bullokar ラインの英英辞書 --- すなわち英語史上初の英英辞書群 --- の源泉だったという事実を指摘しておきたい (Dixon 48) .

関連して,「#3544. 英語辞書史の略年表」 ([2019-01-09-1]),「#603. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (1)」 ([2010-12-21-1]),「#604. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (2)」 ([2010-12-22-1]) を参照.

・ Dixon, R. M. W. The Unmasking of English Dictionaries. Cambridge: CUP, 2018.

2021-02-20 Sat

■ #4317. なぜ「格」が "case" なのか [terminology][case][grammar][history_of_linguistics][etymology][dionysius_thrax][sobokunagimon][latin][greek][vocative]

本ブログでは種々の文法用語の由来について「#1257. なぜ「対格」が "accusative case" なのか」 ([2012-10-05-1]),「#1258. なぜ「他動詞」が "transitive verb" なのか」 ([2012-10-06-1]),「#1520. なぜ受動態の「態」が voice なのか」 ([2013-06-25-1]),「#3307. 文法用語としての participle 「分詞」」 ([2018-05-17-1]),「#3983. 言語学でいう法 (mood) とは何ですか? (1)」 ([2020-03-23-1]),「#3984. 言語学でいう法 (mood) とは何ですか? (2)」 ([2020-03-24-1]),「#3985. 言語学でいう法 (mood) とは何ですか? (3)」 ([2020-03-25-1]) などで取り上げてきた.今回は「格」がなぜ "case" と呼ばれるのかについて,連日参照・引用している Blake (19--20) より概要を引用する.

The term case is from Latin cāsus, which is in turn a translation of the Greek ptōsis 'fall'. The term originally referred to verbs as well as nouns and the idea seems to have been of falling away from an assumed standard form, a notion also reflected in the term 'declension' used with reference to inflectional classes. It is from dēclīnātiō, literally a 'bending down or aside'. With nouns the nominative was taken to be basic, with verbs the first person singular of the present indicative. For Aristotle the notion of ptōsis extended to adverbial derivations as well as inflections, e.g. dikaiōs 'justly' from the adjective dikaios 'just'. With the Stoics (third century BC) the term became confined to nominal inflection . . . .

The nominative was referred to as the orthē 'straight', 'upright' or eutheia onomastikē 'nominative case'. Here ptōsis takes on the meaning of case as we know it, not just of a falling away from a standard. In other words it came to cover all cases not just the non-nominative cases, which in Ancient Greek were called collectively ptōseis plagiai 'slanting' or 'oblique cases' and for the early Greek grammarians comprised genikē 'genitive', dotikē 'dative' and aitiatikē 'accusative'. The vocative which also occurred in Ancient Greek, was not recognised until Dionysius Thrax (c. 100 BC) admitted it, which is understandable in light of the fact that it does not mark the relation of a nominal dependent to a head . . . . The received case labels are the Latin translations of the Greek ones with the addition of ablative, a case found in Latin but not Greek. The naming of this case has been attributed to Julius Caesar . . . . The label accusative is a mistranslation of the Greek aitiatikē ptōsis which refers to the patient of an action caused to happen (aitia 'cause'). Varro (116 BC--27? BC) is responsible for the term and he appears to have been influenced by the other meaning of aitia, namely 'accusation' . . . .

この文章を読んで,いろいろと合点がいった.英語学を含む印欧言語学で基本的なタームとなっている case (格)にせよ declension (語形変化)にせよ inflection (屈折)にせよ,私はその名付けの本質がいまいち呑み込めていなかったのだ.だが,今回よく分かった.印欧語の形態変化の根底には,まずイデア的な理想形があり,それが現世的に実現するためには,理想形からそれて「落ちた」あるいは「曲がった」形態へと堕する必要がある,というネガティヴな発想があるのだ.まず最初に「正しい」形態が設定されており,現実の発話のなかで実現するのは「崩れた」形である,というのが基本的な捉え方なのだろうと思う.

日本語の動詞についていわれる「活用」という用語は,それに比べればポジティヴ(少なくともニュートラル)である.動詞についてイデア的な原形は想定されているが,実際に文の中に現われるのは「堕落」した形ではなく,あくまでプラグマティックに「活用」した形である,という発想がある.

この違いは,言語思想的にも非常におもしろい.洋の東西の規範文法や正書法の考え方の異同とも,もしかすると関係するかもしれない.今後考えていきたい問題である.

・ Blake, Barry J. Case. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2001.

2021-02-16 Tue

■ #4313. 呼格,主格,対格の関係について一考 [greetings][interjection][formula][syntax][exclamation][pragmatics][syncretism][latin][case]

昨日の記事「#4312. 「呼格」を認めるか否か」 ([2021-02-15-1]) で話題にしたように,呼格 (vocative) は,伝統的な印欧語比較言語学では1つの独立した格として認められてきた.しかし,ラテン語などの古典語ですら,第2活用の -us で終わる単数にのみ独立した呼格形が認められるにすぎず,それ以外では形態的に主格に融合 (syncretism) している.「呼格」というよりも「主格の呼びかけ用法」と考えたほうがスッキリするというのも事実である.

このように呼格が形態的に主格に融合してきたことを認める一方で,語用的機能の観点から「呼びかけ」と近い関係にあるとおぼしき「感嘆」 (exclamation) においては,むしろ対格に由来する形態を用いることが多いという印欧諸語の特徴に関心を抱いている.Poor me! や Lucky you! のような表現である.

細江 (157--58) より,統語的に何らかの省略が関わる7つの感嘆文の例を挙げたい.各文の名詞句は形式的には通格というべきだが,機能的にしいていうならば,主格だろうか対格だろうか.続けて,細江の解説も引用する.

How unlike their Belgic sires of old!---Goldsmith.

Wonderful civility this!---Charlotte Brontë.

A lively lad that!---Lord Lytton.

A theatrical people, the French?---Galsworthy.

Strange institution, the English club.---Albington.

This wish I have, then ten times happy me!---Shakespeare.

この最後の me は元来文の主語であるべきものを表わすものであるが,一人称単数の代名詞は感動文では主格の代わりに対格を用いることがあるので,これには種々の理由があるらしい(§130参照)が,ラテン語の語法をまねたことも一原因であったと見られる.たとえば,

Me miserable!---Milton, Paradise Lost, IV. 73.

は全くラテン語の Me miserum! (Ovid, Heroides, V. 149) と一致する.

引用最後のラテン語 me miserum と関連して,Blake の格に関する理論解説書より "ungoverned case" と題する1節も引用しておこう (9) .

In case languages one sometimes encounters phrases in an oblique case used as interjections, i.e. apart from sentence constructions. Mel'cuk (1986: 46) gives a Russian example Aristokratov na fonar! 'Aristocrats on the street-lamps!' where Aristokratov is accusative. One would guess that some expressions of this type have developed from governed expressions, but that the governor has been lost. A standard Latin example is mē miserum (1SG.ACC miserable.ACC) 'Oh, unhappy me!' As the translation illustrates, English uses the oblique form of pronouns in exclamations, and outside constructions generally.

さらに議論を挨拶のような決り文句にも引っかけていきたい.「#4284. 決り文句はほとんど無冠詞」 ([2021-01-18-1]) でみたように,挨拶の多くは,歴史的には主語と動詞が省略され,対格の名詞句からなっているのだ.

語用的機能の観点で関連するとおぼしき呼びかけ,感嘆,挨拶という類似グループが一方であり,歴史形態的に区別される呼格,主格,対格という相対するグループが他方である.この辺りの関係が複雑にして,おもしろい.

・ 細江 逸記 『英文法汎論』3版 泰文堂,1926年.

・ Blake, Barry J. Case. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2001.

2021-02-15 Mon

■ #4312. 「呼格」を認めるか否か [vocative][case][latin][pragmatics][terminology][title][term_of_endearment]

印欧語言語学では,伝統的に格 (case) の1つとして呼格 (vocative) が認められてきた.例えば,ギリシア語やラテン語において呼格は主格などと異なる特別な形態をとる場合があり (ex. Quō vādis, domine? の domine など),その点で呼格という格を独立させて立てる意義は理解できる.

しかし,昨日の記事「#4311. 格とは何か?」 ([2021-02-14-1]) で掲げた格の定義を振り返れば,"Case is a system of marking dependent nouns for the type of relationship they bear to their heads." である.いわゆる呼格というものは,文の構成要素としては独立し遊離した存在であり,別の要素に依存しているわけではないのだから,依存関係が存在することを前提とする格体系の内側に属しているというのは矛盾である.呼格は依存関係の非存在を標示するのだ,というレトリックも可能かもしれないが,必ずしもすべての言語学者を満足させるには至っていない.構造主義的厳密性をもって主張する言語学者 Hjelmslev は格として認めていないし,英語学者 Jespersen も同様だ.英語学者の Curme も,主格の1機能と位置づけているにすぎない.

しかし,いわゆる呼格の機能である「呼びかけ」には,統語上の独立性のみならず音調上の特色がある.言語学的には,何らかの方法で他の要素と区別しておく必要があるのも確かである.言い換えれば,形態的な観点から格としてみなすかどうかは別にしても,機能や用法の観点からはカテゴリー化しておくのがよさそうだ.

「呼格」には限られた特殊な語句が用いられる傾向があるということも指摘しておきたい.名前,代名詞 you,親族名称,称号,役職名が典型だが,そのほかにも (my) darling, dear, honey, love, (my) sweet; old man, fellow; young man; sir, madam; ladies and gentlemen などが挙げられる.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2021-01-03 Sun

■ #4269. なぜ digital transformation を略すと DX となるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版 [hellog-radio][sobokunagimon][abbreviation][grammatology][prefix][word_game][x][information_theory][preposition][latin]

本年も引き続き,大学や企業など多くの組織で多かれ少なかれ「オンライン」が推奨されることになるかと思います.コロナ禍に1年ほど先立つ2018年12月に,すでに経済産業省が「デジタルトランスフォーメーションを推進するためのガイドライン(DX推進ガイドライン)」 (PDF) を発表しており,この DX 路線が昨今の状況によりますます押し進められていくものと予想されます.

ですが,digital transformation の略が,なぜ *DT ではなく DX なのか,疑問に思いませんか? DX のほうが明らかに近未来的で格好よい見映えですが,この X はいったいどこから来ているのでしょうか.

実は,これは一種の言葉遊びであり文字遊びなのです.音声解説をお聴きください

trans- というのはラテン語の接頭辞で,英語における through や across に相当します.across に翻訳できるというところがポイントです.trans- → across → cross → 十字架 → X という,語源と字形に引っかけた一種の言葉遊びにより,接頭辞 trans- が X で表記されるようになったのです.実は DX = digital transformation というのはまだ生やさしいほうで,XMIT, X-ing, XREF, Xmas, Xian, XTAL などの略記もあります.それぞれ何の略記か分かるでしょうか.

このような X に関する言葉遊び,文字遊びの話題に関心をもった方は,ぜひ##4219,4189,4220の記事セットをご参照ください.X は実におもしろい文字です.

2020-12-06 Sun

■ #4241. なぜ語頭や語末に en をつけると動詞になるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版 [hellog-radio][sobokunagimon][suffix][prefix][verb][latin][loan_word]

英語の動詞には接頭辞 en- をもつものが多くあります.encourage, enable, enrich, empower, entangle などです.一方,接尾辞 -en をもつ動詞も少なくありません.strengthen, deepen, soften, harden, fasten などです.さらに,語頭と語末の両方に en の付いた enlighten, embolden, engladden のような動詞すらあります.接頭辞にも接尾辞にもなる,この en とはいったい何者なのでしょうか.では,音声の解説をどうぞ.

意外や意外,接頭辞 en- と接尾辞 -en はまったく別語源なのですね.接頭辞 en- は,ラテン語の接頭辞 in- に由来し,フランス語を経由して少しだけ変形しつつ,英語に入ってきたものです.究極的には英語の前置詞 in と同語源で,意味は「中へ」です.この接頭辞を付けると「中へ入る」「中へ入れる」という運動が感じられるので,動詞を形成する能力を得たのでしょう.名詞や形容詞,すでに動詞である基体に付いて,数々の新たな動詞を生み出してきました.

一方,接尾辞 -en はラテン語由来ではなく本来の英語的要素です.古英語で他動詞を作る接尾辞として -nian がありましたが,その最初の n の部分が現代の接尾辞 -en の起源です.形容詞や名詞の基体に付いて新たな動詞を作りました.

このように接頭辞 en- と接尾辞 -en は語源的には無関係なのですが,形式の点でも,動詞を作る機能の点でも,明らかに類似しており,関係づけたくなるのが人情です.比較的珍しいものの,enlighten のように頭とお尻の両方に en の付く動詞があるのも分かるような気がします.

英語史や英単語の語源を学習していると,一見関係するようにみえる2つのものが,実はまったくの別物だったと分かり目から鱗が落ちる経験をすることが多々あります.今回の話題は,その典型例ですね.

今回取り上げた接頭辞 en- と接尾辞 -en について,詳しくは##1877,3510の記事セットをご覧ください.

2020-11-17 Tue

■ #4222. 行為者接尾辞 -eer [suffix][agentive_suffix][loan_word][french][latin][register][stress][conversion]

ゼミ生からのインスピレーションで,標記の行為者接尾辞 (agentive_suffix) に関心を抱いた.この接尾辞をもつ語はフランス語由来のものがほとんどであり,その来歴を反映して,語末音節を構成する接尾辞自身に強勢が落ちるという特徴がみられる.つまり語末の発音は /ˈɪə(r)/ となる.engineer, pioneer, volunteer をはじめとして,auctioneer, electioneer, gazetteer, mountaineer, profiteer などが挙がる.語源的には -ier もその兄弟というべきであり,cachier, cavalier, chevalier, cuirassier, financier, gondolier なども -eer 語と同じ特徴を有する.いずれもフランス語らしい振る舞いを示し,なぜ英語においてこのフランス語風の形式(発音と綴字)が定着したのだろうかという点で興味深い(cf. 「#594. 近代英語以降のフランス借用語の特徴」 ([2010-12-12-1]),「#1291. フランス借用語の借用時期の差」 ([2012-11-08-1])).

Jespersen (§15.51; 243) より,-eer, -ier に関する解説を引用する.

15.51 Words in -eer, -ier (stressed) -[ˈɪə] are mostly originally F words in -ier (generally from L -arius). Most of the OF words in -ier were adopted in ME with -er, and the stress was shifted to the first syllable . . . , as also in a few in which the i was kept . . . .

A few words borrowed in ME times kept the final stress, and so did nearly all the later loans (many from the 16th and 17th c.). The established spelling of most of these, and of nearly all words coined on English soil, is -eer, as in auctioneer, cannoneer, charioteer (Keats 46), gazetteer, jargoneer (NED from 1913), mountaineer, muffineer, 'small castor for sprinkling salt or sugar on muffins' (NED 1806), muleteer [mjuˑliˈtiə], musketeer, pioneer, pistoleer (Carlyle Essays 251), routineer (Shaw D 54), and volunteer, but many of them preserved the F spelling, e.g. cavalier and chevalier, cuirassier, and finanicier.

The recent motorneer, is coined on the pattern of engineer.

Sh in some cases has initial-stressed -er-forms instead of -eer, e.g. ˈenginer, ˈmutiner (Cor I. 1.244), and ˈpioner.

この解説に従えば,-eer は私たちもよく知る行為者接尾辞 -er の一風変わった兄弟としてとらえてよさそうだ.

しかし, -eer には意味論的,語形成的に注目すべき点がある.まず,形成された行為者名詞は,軽蔑的な意味を帯びることが多いという事実がある.crotcheteer, garreteer, pamphleteer, patrioteer, privateer, profiteer, pulpiteer, racketeer, sonneteer などである.

もう1つは,行為者名詞がそのまま動詞へ品詞転換 (conversion) する例がみられることだ.electioneer, engineer, pamphleteer, profiteer, pioneer, volunteer などである.これは上記の軽蔑的な語義とも密接に関係してくるかもしれない.なお,commandeer は,動詞としてしか用いられないという妙な -eer 語である.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow