2020-02-14 Fri

■ #3945. "<h> second" の2重字の起源と発達 [digraph][spelling][orthography][latin][greek][consonant][h][exaptation][gh]

英語の正書法には <ch>, <gh>, <ph>, <sh>, <th>, <wh> など,2文字で1つの音を表わす2重字 (digraph) が少なからず存在する.1文字と1音がきれいに対応するのがアルファベットの理想だとすれば,2重字が存在することは理想からの逸脱にほかならない.しかし現実には古英語の昔から現在に至るまで,多種類の2重字が用いられてきたし,それ自体が歴史の栄枯盛衰にさらされてきた.

今回は,上に挙げた2文字目に <h> をもつ2重字を取り上げよう."verb second" の語順問題ならぬ "<h> second" の2重字問題である.これらの "<h> second" の2重字は,原則として単子音に対応する.<ch> ≡ /ʧ/, <ph> ≡ /f/, <sh> ≡ /ʃ/, <th> ≡ /θ, ð/, <wh> ≡ /w, ʍ/ などである.ただし,<gh> については,ときに /f/ などに対応するが,無音に対応することが圧倒的に多いことを付け加えておく(「#2590. <gh> を含む単語についての統計」 ([2016-05-30-1]),「#1195. <gh> = /f/ の対応」 ([2012-08-04-1])).

現代英語にみられる "<h> second" の2重字が英語で使われ始めたのは,およそ中英語期から初期近代英語期のことである.それ以前の古英語や初期中英語では,<ch>, <gh>, <ph>, <th> に相当する子音は各々 <c>, <ȝ>, <f>, <þ, ð> の1文字で綴られていたし,<sh>, <wh> に相当する子音は各々 <sc>, <hw> という別の2重字で綴られるのが普通だった.

<ch> と <th> については,ラテン語の正書法で採用されていたことから中英語の写字生も見慣れていたことだろう.彼らはこれを母語に取り込んだのである.また,<ph> についてはギリシア語(あるいはそれを先に借用していたラテン語)からの借用である.

英語は,ラテン語やギリシア語から借用された上記のような2重字に触発される形で,さらにフランス語でも平行的な2重字の使用がみられたことも相俟って,2文字目に <h> をもつ新たな2重字を自ら発案するに至った.<gh>, <sh>, <wh> などである.

このように,英語の "<h> second" の2重字は,ラテン語にあった2重字から直接・間接に影響を受けて成立したものである.だが,なぜそもそもラテン語では2文字目に <h> を用いる2重字が発展したのだろうか.それは,<h> の文字に対応すると想定される /h/ という子音が,後期ラテン語やロマンス諸語の時代に向けて消失していくことからも分かる通り,比較的不安定な音素だったからだろう.それと連動して <h> の文字も他の文字に比べて存在感が薄かったのだと思われる.<h> という文字は,宙ぶらりんに浮遊しているところを捕らえられ,語の区別や同定といった別の機能をあてがわれたと考えられる.一種の外適応 (exaptation) だ.

実は,英語でも音素としての /h/ 存在は必ずしも安定的ではなく,ある意味ではラテン語と似たり寄ったりの状況だった.そのように考えれば,英語でも,中途半端な存在である <h> を2重字の構成要素として利用できる環境が整っていたと理解できる.(cf. 「#214. 不安定な子音 /h/」 ([2009-11-27-1]),「#459. 不安定な子音 /h/ (2)」 ([2010-07-30-1]),「#1677. 語頭の <h> の歴史についての諸説」 ([2013-11-29-1]),「#1292. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ」 ([2012-11-09-1]),「#1675. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ (2)」 ([2013-11-27-1]),「#1899. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ (3)」 ([2014-07-09-1])).

以上,主として Minkova (111) を参照した.今回の話題と関連して,以下の記事も参照.

・ 「#2423. digraph の問題 (1)」 ([2015-12-15-1])

・ 「#2424. digraph の問題 (2)」 ([2015-12-16-1])

・ 「#3251. <chi> は「チ」か「シ」か「キ」か「ヒ」か?」 ([2018-03-22-1])

・ 「#3337. Mulcaster の語彙リスト "generall table" における語源的綴字 (2)」 ([2018-06-16-1])

・ 「#2049. <sh> とその異綴字の歴史」 ([2014-12-06-1])

・ 「#1795. 方言に生き残る wh の発音」 ([2014-03-27-1])

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

2020-01-30 Thu

■ #3930. なぜギリシアとローマは続け書きを採用したか? (2) [alphabet][distinctiones][punctuation][reading][writing][latin][greek][literacy][word]

昨日の記事 ([2020-01-29-1]) に引き続き,なぜギリシアとローマが,それ以前の地中海世界で普通に行なわれていた分かち書き (distinctiones) を捨て,代わりに続け書き (scriptura continua) を作用したかという問題について.

Saenger によれば,この問題に迫るには,読むという行為に対する現代的な発想を脇に置き,古代の読書習慣とその社会的文脈を理解する必要があるという.端的にいえば,現代人はみな黙読や速読に慣れており,何よりも「読みやすさ」を重視するが,古代ギリシアやローマの限られた人口の読み手にとって,読む行為とは口頭の音読のことであり,現代的な「読みやすさ」を追求する姿勢はなかったのだという.以下,Saenger の解説を聞いてみよう (11--12) .

. . . the ancient world did not possess the desire, characteristic of the modern age, to make reading easier and swifter because the advantages that modern readers perceive as accruing from ease of reading were seldom viewed as advantages by the ancients. These include the effective retrieval of information in reference consultation, the ability to read with minimum difficulty a great many technical logical, and scientific texts, and the greater diffusion of literacy throughout all social strata of the population. We know that the reading habits of the ancient world, which were profoundly oral and rhetorical by physiological necessity as well as by taste, were focused on a limited and intensely scrutinized canon of literature. Because those who read relished the mellifluous metrical and accentual patterns of pronounced text and were not interested in the swift intrusive consultation of books, the absence of interword space in Greek and Latin was not perceived to be an impediment to effective reading, as it would be to the modern reader, who strives to read swiftly. Moreover, oralization, which the ancients savored aesthetically, provided mnemonic compensation (through enhanced short-term aural recall) for the difficulty in gaining access to the meaning of unseparated text. Long-term memory of texts frequently read aloud also compensated for the inherent graphic and grammatical ambiguities of the languages of late antiquity.

Finally, the notion that the greater portion of the population should be autonomous and self-motivated readers was entirely foreign to the elitist literate mentality of the ancient world. For the literate, the reaction to the difficulties of lexical access arising from scriptura continua did not spark the desire to make script easier to decipher, but resulted instead in the delegation of much of the labor of reading and writing to skilled slaves, who acted as professional readers and scribes. It is in the context of a society with an abundant supply of cheap, intellectually skilled labor that ancient attitudes toward reading must be comprehended and the ready and pervasive acceptance of the suppression of word separation throughout the Roman Empire understood.

引用の最後に示唆されているように,古代人は続け書きにシフトすることで,読みにくさをあえて高めようとした,という言い方さえできるのかもしれない.この観点は,中世後期に再び分かち書きへと回帰していく過程を理解する上でも示唆的である.関連して「#1903. 分かち書きの歴史」 ([2014-07-13-1]) も参照.

・ Saenger, P. Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 1997.

2020-01-29 Wed

■ #3929. なぜギリシアとローマは続け書きを採用したか? (1) [alphabet][distinctiones][punctuation][reading][writing][latin][greek][indo-european][word]

アルファベットの分かち書き (distinctiones) と続け書き (scriptura continua) の問題については,最近では「#3926. 分かち書き,表語性,黙読習慣」 ([2020-01-26-1]) で,それ以前にも distinctiones の各記事で取り上げてきた.

Saenger (9) によると,アルファベットに母音表記の慣習が持ち込まれる以前の地中海世界では,スペースによるか点によるかの違いこそあれ,分かち書きが普通に行なわれていた.ところが,ギリシア語において母音表記が可能となるに及び,続け書きが生まれたという.これを時系列で整理すると次のようになる.

まず,アルファベット使用の初期から分かち書きは普通にあった.ところが,ギリシア・ローマ時代にそれが廃用となり,代わって続け書きが一般化した.ローマ帝国が崩壊し,中世後期の8世紀頃になると分かち書きが改めて導入され,その後徐々に一般化して現代に至る.

分かち書きは現在では当然視されているが,母音表記を享受し始めた古典時代の間に,その慣習が一度廃れた経緯があるということだ.では,なぜ母音表記の導入により,私たちにとって明らかに便利に思われる分かち書きが廃用となり,むしろ読みにくいと思われる続け書きが発達したのだろうか.Saenger (9--10) によれば,母音表記と続け書きの間には密接な関係があるという.

The uninterrupted writing of ancient scriptura continua was possible only in the context of a writing system that had a complete set of signs for the unambiguous transcription of pronounced speech. This occurred for the first time in Indo-European languages when the Greeks adapted the Phoenician alphabet by adding symbols for vowels. The Greco-Latin alphabetical scripts, which employed vowels with varying degrees of modification, were used for the transcription of the old forms of the Romance, Germanic, Slavic, and Hindu tongues, all members of the Indo-European language group, in which words were polysyllabic and inflected. For an oral reading of these Indo-European languages, the reader's immediate identification of words was not essential, but a reasonably swift identification and parsing of syllables was fundamental. Vowels as necessary and sufficient codes for sounds permitted the reader to identify syllables swiftly within rows of uninterrupted letters. Before the introduction of vowels to the Phoenician alphabet, all the ancient languages of the Mediterranean world---syllabic or alphabetical, Semitic or Indo-European---were written with word separation by either space, points, or both in conjunction. After the introduction of vowels, word separation was no longer necessary to eliminate an unacceptable level of ambiguity.

Throughout the antique Mediterranean world, the adoption of vowels and of scriptura continua went hand in hand. The ancient writings of Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, and Israel did not employ vowels, so separation between words was retained. Had the space between words been deleted and the signs been written in scriptura continua, the resulting visual presentation of the text would have been analogous to a modern lexogrammatic puzzle. Such written languages might have been decipherable, given their clearly defined conventions for word order and contextual clues, but only after protracted cognitive activity that would have made fluent reading as we know it impractical. While the very earliest Greek inscriptions were written with separation by interpuncts, points placed at midlevel between words, Greece soon thereafter became the first ancient civilization to employ scriptura continua. The Romans, who borrowed their letter forms and vowels from the Greeks, maintained the earlier Mediterranean tradition of separating words by points far longer than the Greeks, but they, too, after a scantily documented period of six centuries, discarded word separation as superfluous and substituted scriptura continua for interpunct-separated script in the second century A.D.

ここで展開されている議論について,私はよく理解できていない.母音表記の導入の結果,音節が同定しやすくなったという理屈がよくわからない.また,仮にそれが本当だったとして,文字の読み手が従来の分かち書きではなく続け書きにシフトしたとしても何とか解読できる,という点までは理解できるが,なぜ続け書きに積極的にシフトしたのかは不明である.上の議論は,消極的な説明づけにすぎないように思われる.

母音文字を発明してアルファベットを便利にしたギリシア人が,読みにくい続け書きにシフトしたというのは,何か矛盾しているように感じられる.実際,この問題は多くの論者を悩ませ続けてきたようだ (Saenger 10)

ギリシア人による母音文字の導入という文字史上の画期的な出来事については,「#423. アルファベットの歴史」 ([2010-06-24-1]) や「#2092. アルファベットは母音を直接表わすのが苦手」 ([2015-01-18-1]) を参照.

・ Saenger, P. Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 1997.

2019-12-30 Mon

■ #3899. ラテン語 domus (家)の語根ネットワーク [word_family][etymology][latin][loan_word]

昨日の記事「#3898. danger, dangerous の意味変化」 ([2019-12-29-1]) で触れたように,danger, dangerous の語源素はラテン語の domus (家,ドーム)である.ラテン語ではきわめて基本的な語であるから,そこから派生した語は多く,英語にも様々な経路で借用されてきた.以下に関連語を一覧してみよう.昨日みたように,「家」「家の主人」「支配者」「支配(力)」「危険」など各種の意味が発展してきた様子が伝わるのではないか.

condominium, dame, Dan, danger, demesne, Dom, domain, dome, domestic, domicile, dominant, dominate, domination, domineering, dominical, dominion, domino, dona, duenna, dungeon, madam, madame, mademoiselle, Madonna, majordomo, predominate

「危険」と関連して「損害」の意味を含む damage, damn, condemn なども,domus と間接的に関わる.これらの語は,直接的にはラテン語の別の語根 damnum "loss, injury" に起源をもち,その後期ラテン語形である damniārium を経由して発展してきたと考えられるが,そこには後者の語形と *dominiāriu(m) "dominion" との混同も関与していたようだ.

ラテン語からさらにさかのぼれば,印欧祖語 *dem(ə)- "house, household" にたどりつく.ここから古英語経由で timber (建築用木材),古ノルド語経由で toft (家屋敷),ギリシア語経由で despot (専制君主)なども英語語彙に加わっている.

2019-12-16 Mon

■ #3885. 『英語教育』の連載第10回「なぜ英語には類義語が多いのか」 [rensai][notice][lexicology][synonym][loan_word][borrowing][french][latin][lexical_stratification][sobokunagimon][link]

12月13日に,『英語教育』(大修館書店)の1月号が発売されました.英語史連載「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ」の第10回となる今回は「なぜ英語には類義語が多いのか」という話題を扱っています.

英語には「上がる」を意味する動詞として rise,mount,ascend などの類義語があります.「活発な」を表わす形容詞にも lively, vivacious, animated などがあります.名詞「人々」についても folk, people, population などが挙がります.これらは「英語語彙の3層構造」の典型例であり,英語がたどってきた言語接触の歴史の遺産というべきものです.本連載記事では,英語語彙に特徴的な豊かな類義語の存在が,1066年のノルマン征服と16世紀のルネサンスのたまものであり,さらに驚くことに,日本語にもちょうど似たような歴史的事情があることを指摘しています.

「英語語彙の3層構造」については,本ブログでも関連する話題を多く取り上げてきました.以下をご覧ください.

・ 「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1])

・ 「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1])

・ 「#1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造」 ([2014-09-08-1])

・ 「#2072. 英語語彙の三層構造の是非」 ([2014-12-29-1])

・ 「#2279. 英語語彙の逆転二層構造」 ([2015-07-24-1])

・ 「#2643. 英語語彙の三層構造の神話?」 ([2016-07-22-1])

・ 「#387. trisociation と triset」 ([2010-05-19-1])

・ 「#2977. 連載第6回「なぜ英語語彙に3層構造があるのか? --- ルネサンス期のラテン語かぶれとインク壺語論争」」 ([2017-06-21-1])

・ 「#3374. 「示相語彙」」 ([2018-07-23-1])

・ 「#335. 日本語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-28-1])

・ 「#3357. 日本語語彙の三層構造 (2)」 ([2018-07-06-1])

・ 「#1630. インク壺語,カタカナ語,チンプン漢語」 ([2013-10-13-1])

・ 「#1526. 英語と日本語の語彙史対照表」 ([2013-07-01-1])

・ 堀田 隆一 「なぜ英語には類義語が多いのか」『英語教育』2020年1月号,大修館書店,2019年12月13日.62--63頁.

2019-11-25 Mon

■ #3864. retard, pulse の派生語にみる近代英語期の語彙問題 [word_formation][latin][french][emode][lexicology][borrowing][loan_word][derivation][word_family]

昨日の記事「#3863. adapt の派生語にみる近代英語期の語彙問題」 ([2019-11-24-1]) に引き続き,Durkin (334) より retard および pulse に関する派生語の乱立状況をのぞいてみよう.

retard (1490) と retardate (1613) の2語が,動詞としてライバル関係にある基体である.ここから派生した語群を年代順に挙げよう(ただし,時間的には逆転しているようにみえるケースもある).retardation (n.) (c.1437), retardance (n.) (1550), retarding (n.) (1585), retardment (n.) (1640), retardant (adj.) (1642), retarder (n.) (1644), retarding (adj.) (1645), retardative (adj.) (1705), retardure (n.) (1751), retardive (adj.) (1787), retardant (n.) (1824), retardatory (adj.) (1843), retardent (adj.) (1858), retardent (n.) (1858), retardency (n.) (1939), retardancy (n.) (1947) となる.

同じように pulse (?a.1425) と pulsate (1674) を動詞の基体として,様々な派生語が生じてきた(やはり時間的には逆転しているようにみえるケースもある).pulsative (n.) (a.1398), pulsatile (adj.) (?a.1425), pulsation (n.) (?a.1425), pulsing (n.) (a.1525), pulsing (adj.) (1559), pulsive (adj.) (1600), pulsatory (adj.) (1613), pulsant (adj.) (1642), pulsating (adj.) (1742), pulsating (n.) (1829) である.

このなかには直接の借用語もあるだろうし,英語内で形成された語もあるだろう.その両方であると解釈するのが妥当な語もあるだろう.混乱,類推,勘違い,浪費,余剰などあらゆるものが詰まった word family である.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-11-24 Sun

■ #3863. adapt の派生語にみる近代英語期の語彙問題 [word_formation][latin][french][emode][lexicology][borrowing][loan_word][derivation][word_family]

初期近代英語期の語彙に関する問題の1つに,同根派生語の乱立がある.「#3157. 華麗なる splendid の同根類義語」 ([2017-12-18-1]),「#3258. 17世紀に作られた動詞派生名詞群の呈する問題 (1)」 ([2018-03-29-1]),「#3259. 17世紀に作られた動詞派生名詞群の呈する問題 (2)」 ([2018-03-30-1]) などで論じてきたが,今回は adapt という基体を出発点にした派生語の乱立をのぞいてみよう.以下,Durkin (332--33) に依拠する.

OED によると,15世紀初期に adapted が現われるが,adapt 単体として出現するのは1531年である.これ自体,ラテン語 adaptāre とフランス語 adapter のいずれが借用されたものなのか,あるいはいずれの形に基づいているものなのか,必ずしも明確ではない.

その後,両形を基体とした様々な派生語が次々に現われる.adaptation (n.) (1597), adapting (n.) (1610), adaption (n.) (1615), adaptate (v.) (1638), adaptness (n.) (1657), adapt (adj.) (1658), adaptability (n.) (1661), adaptable (adj.) (1692), adaptive (adj.) (1734), adaptment (n.) (1739), adapter (n.) (1753), adaptor (1764), adaptative (adj.) (1815), adaptiveness (n.) (1815), adaptableness (n.) (1833), adaptorial (adj.) (1838), adaptational (adj.) (1849), adaptivity (n.) (1840), adaptativeness (n.) (1841), adaptationism (n.) (1889), adaptationalism (n.) (1922) のごとくだ.

いずれの語がいずれの言語からの借用なのかが不明確であるし,そもそも借用などではなく英語内部において造語された語である可能性も高い.後者の場合には「英製羅語」や「英製仏語」ということになる.歴史語彙論的に,このような語群を何と呼んだらよいのか悩むところである.

この問題に関する Durkin (333) の解説を引いておく.

Very few of these words show direct borrowing from Latin or French (probably just adapt verb, adaptate, adaptation, and maybe adapt adjective), but a number of others are best explained as hybrid or analogous formations on Latin stems. The group as a whole illustrates the impact of the borrowing of a handful of key words in giving rise to an extended word family over time, including many full or partial synonyms. In some cases synonyms may have arisen accidentally, as speakers were simply ignorant of the existence of earlier formations; some others could result from misrecollection of earlier words. . . . However, such profligacy and redundancy is typical of such word families in English well into the Later Modern period, well beyond the period in which 'copy' was particularly in vogue in literary style.

ここからキーワードを拾い出せば "hybrid or analogous formations", "ignorant", "misrecollection", "profligacy and redundancy" などとなろうか.

今回の内容と関連する話題として,以下の記事も参照されたい.

・ 「#1493. 和製英語ならぬ英製羅語」 ([2013-05-29-1])

・ 「#1927. 英製仏語」 ([2014-08-06-1])

・ 「#3165. 英製羅語としての conspicuous と external」 ([2017-12-26-1])

・ 「#3166. 英製希羅語としての科学用語」 ([2017-12-27-1])

・ 「#3179. 「新古典主義的複合語」か「英製羅語」か」 ([2018-01-09-1])

・ 「#3348. 初期近代英語期に借用系の接辞・基体が大幅に伸張した」 ([2018-06-27-1])

・ 「#3858. 「和製○語」も「英製△語」も言語として普通の現象」 ([2019-11-19-1])

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-11-18 Mon

■ #3857. 『英語教育』の連載第9回「なぜ英語のスペリングには黙字が多いのか」 [rensai][notice][silent_letter][consonant][spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][sound_change][phonetics][etymological_respelling][latin][standardisation][sobokunagimon][link]

11月14日に,『英語教育』(大修館書店)の12月号が発売されました.英語史連載「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ」の第9回となる今回の話題は「なぜ英語のスペリングには黙字が多いのか」です.

黙字 (silent_letter) というのは,climb, night, doubt, listen, psychology, autumn などのように,スペリング上は書かれているのに,対応する発音がないものをいいます.英単語のスペリングをくまなく探すと,実に a から z までのすべての文字について黙字として用いられている例が挙げられるともいわれ,英語学習者にとっては実に身近な問題なのです.

今回の記事では,黙字というものが最初から存在したわけではなく,あくまで歴史のなかで生じてきた現象であること,しかも個々の黙字の事例は異なる時代に異なる要因で生じてきたものであることを易しく紹介しました.

連載記事を読んで黙字の歴史的背景の概観をつかんでおくと,本ブログで書いてきた次のような話題を,英語史のなかに正確に位置づけながら理解することができるはずです.

・ 「#2518. 子音字の黙字」 ([2016-03-19-1])

・ 「#1290. 黙字と黙字をもたらした音韻消失等の一覧」 ([2012-11-07-1])

・ 「#34. thumb の綴りと発音」 ([2009-06-01-1])

・ 「#724. thumb の綴りと発音 (2)」 ([2011-04-21-1])

・ 「#1902. 綴字の標準化における時間上,空間上の皮肉」 ([2014-07-12-1])

・ 「#1195. <gh> = /f/ の対応」 ([2012-08-04-1])

・ 「#2590. <gh> を含む単語についての統計」 ([2016-05-30-1])

・ 「#3333. なぜ doubt の綴字には発音しない b があるのか?」 ([2018-06-12-1])

・ 「#116. 語源かぶれの綴り字 --- etymological respelling」 ([2009-08-21-1])

・ 「#1187. etymological respelling の具体例」 ([2012-07-27-1])

・ 「#579. aisle --- なぜこの綴字と発音か」 ([2010-11-27-1])

・ 「#580. island --- なぜこの綴字と発音か」 ([2010-11-28-1])

・ 「#1156. admiral の <d>」 ([2012-06-26-1])

・ 「#3492. address の <dd> について (1)」 ([2018-11-18-1])

・ 「#3493. address の <dd> について (2)」 ([2018-11-19-1])

・ 堀田 隆一 「なぜ英語のスペリングには黙字が多いのか」『英語教育』2019年12月号,大修館書店,2019年11月14日.62--63頁.

2019-11-07 Thu

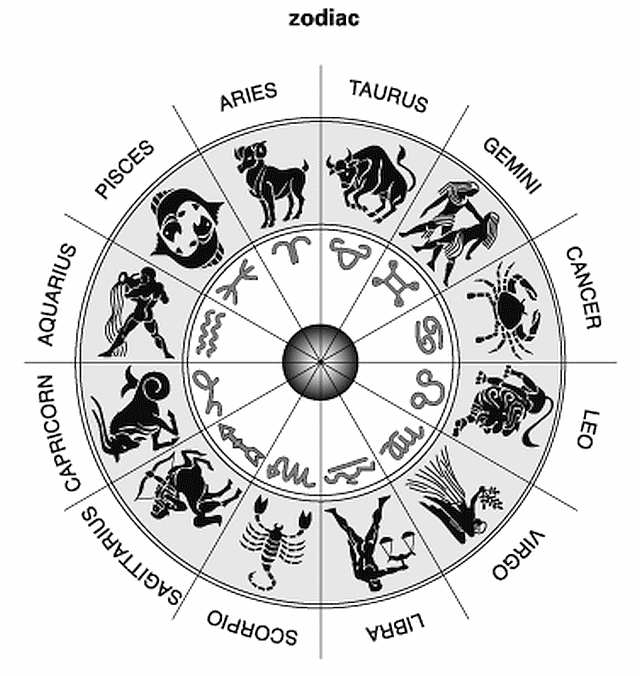

■ #3846. 黄道十二宮・星座名の語彙階層 [lexical_stratification][latin][lexicology][astrology][loan_word][animal]

『英語便利辞典』 (178--79) より,黄道十二宮と星座に関する一覧表を掲げよう(星座名については「#3707. 88星座」 ([2019-06-21-1]) も参照).

| Signs of the Zodiac (黄道十二宮) | |||

| 宮 (house) | 獣帯星座 (zodiacal constellations) | 太陽が通過する期間 | 運勢・性格 |

| spring signs (春の星座宮) | |||

| Aries (白羊宮) | *the Ram (おひつじ座) | 3月21日?4月20日 | energetic, ambitious, generous, aggressive |

| Taurus (金牛宮) | *the Bull (おうし座) | 4月21日?5月22日 | charming, witty, kind, restless |

| Gemini (双子宮) | *the Twins (ふたご座) | 5月23日?6月21日 | strong, loyal, determined, quiet |

| summer signs (夏の星座宮) | |||

| Cancer (巨蟹宮) | *the Crab (かに座) | 6月22日?7月22日 | sensitive, materialistic, careful, humorous |

| Leo (獅子宮) | the Lion (しし座) | 7月23日?8月22日 | dignified, honest, vain |

| Virgo (処女宮) | the Virgin (おとめ座) | 8月23日?9月22日 | perfectionist, dependable, gentle, efficient |

| autumn signs (秋の星座宮) | |||

| Libra (天秤宮) | the Balance [*Scales] (てんびん座) | 9月23日?10月22日 | gracious, harmonious, logical, fair |

| Scorpio (天蠍宮) | the Scorpion (さそり座) | 10月23日?11月21日 | courageous, intense, secretive, intelligent |

| Sagittarius (人馬宮) | the Archer (いて座) | 11月22日?12月22日 | truthful, friendly, optimistic, adventurous |

| winter signs (冬の星座宮) | |||

| Capricorn (磨羯宮) | *the Goat (やぎ座) | 12月23日?1月20日 | hardworking, kind, determined, disciplined |

| Aquarius (宝瓶宮) | *the Water Bearer [Carrier] (みずがめ座) | 1月21日?2月19日 | loyal, wise, creative, aloof |

| Pisces (双魚宮) | *the Fish (うお座) | 2月20日?3月20日 | kind, quiet, romantic, easygoing |

この表から気づくのは,1列目の占星術・天文学上の名称と,2列目の星座を表わす動物・人などの名前とが,しばしば似ていないことだ.Leo/the Lion, Virgo/Virgin, Scorpio/Scorpion は明らかに類似しているが,それ以外はすべて似ていないようにみえる.前者は学問的な用語としてすべてラテン語(さらに遡ってギリシア語)由来だが,後者はすべてとは言わずとも多くが英語本来語の庶民的な単語である.表中で * を付しているものがそれである(Scales については,厳密には英語由来ではなく古ノルド語由来だが,少なくともゲルマン系の単語ではある).* の付されていない2列目の5つの名前については,確かにラテン語かフランス語に由来するものの,古英語期や中英語期など比較的早い段階に借用されており,早々に英語化していた語といってよい.

全体としていえば,1列目はラテン語の威厳を背負った学問用語,2列目は(事実上)英語的な庶民性を帯びた動物・人などの一般名といってよい.これは有名な「動物と肉の語彙」の話題にも比較される.例の ox/beef, swine/pork, sheep/mutton, fowl/poultry, deer/venison, calf/veal の語彙階層の対立である.これについては,以下の記事を参照.

・ 「#331. 動物とその肉を表す英単語」 ([2010-03-24-1])

・ 「#332. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」の神話」 ([2010-03-25-1])

・ 「#1583. swine vs pork の社会言語学的意義」 ([2013-08-27-1])

・ 「#1603. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」を最初に指摘した人」 ([2013-09-16-1])

・ 「#1604. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」を次に指摘した人たち」 ([2013-09-17-1])

・ 「#2352. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」の神話 (2)」 ([2015-10-05-1])

・ 小学館外国語辞典編集部(編) 『英語便利辞典』 小学館,2006年.

2019-11-06 Wed

■ #3845. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第5回「キリスト教の伝来」を終えました [asacul][notice][slide][link][christianity][alphabet][latin][loan_word][bible][religion]

「#3833. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第5回「キリスト教の伝来」のご案内」 ([2019-10-25-1]) で案内した朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室の講座を11月2日(土)に終えました.今回も大勢の方に参加していただき,白熱した質疑応答が繰り広げられました.多岐にわたるご指摘やコメントをいただき,たいへん充実した会となりました.

講座で用いたスライド資料をこちらに置いておきますので,復習等にご利用ください.スライドの各ページへのリンクも張っておきます.

1. 英語の歴史と語源・5 「キリスト教の伝来」

2. 第5回 キリスト教の伝来

3. 目次

4. 1. イングランドのキリスト教化

5. 古英語期まで(?1066年)のキリスト教に関する略年表

6. 2. ローマ字の採用

7. ルーン文字とは?

8. 現存する最古の英文はルーン文字で書かれていた

9. ルーン文字の遺産

10. 古英語のアルファベット

11. 古英語文学の開花

12. 3. ラテン語の借用

13. 古英語語彙におけるラテン借用語比率

14. キリスト教化以前と以後のラテン借用

15. 4. 聖書翻訳の伝統

16. 5. 宗教と言語

17. 外来宗教が英語と日本語に与えた言語的影響の比較

18. 日本語における宗教語彙

19. まとめ

20. 補遺:「主の祈り」の各時代のヴァージョン

21. 参考文献

次回の第6回は少し先の2020年3月21日(土)の15:15?18:30となります.「ヴァイキングの侵攻」と題して英語史上の最大の異変に迫る予定です.

2019-10-22 Tue

■ #3830. 古英語のラテン借用語は現代まで地続きか否か [lexicology][latin][loan_word][oe][borrowing]

古英語に借用されたラテン単語について,以下の記事で取り上げてきた.

・ 「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1])

・ 「#1895. 古英語のラテン借用語の綴字と借用の類型論」 ([2014-07-05-1])

・ 「#3787. 650年辺りを境とする,その前後のラテン借用語の特質」 ([2019-09-09-1])

・ 「#3790. 650年以前のラテン借用語の一覧」 ([2019-09-12-1])

・ 「#3829. 650年以後のラテン借用語の一覧」 ([2019-10-21-1])

これらのラテン借用語に関する1つの問題は,そのうちの少なからぬ数の語が確かに現代英語にもみられるが,それは古英語期から生き残ってきたものなのか,あるいは一度廃れたものが後代に再借用されたものなのかということだ.いずれにせよラテン語源としては共通であるという言い方はできるかもしれないが,前者であれば古英語期の借用語として英語における使用の歴史が長いことになるし,後者であれば中英語期や近代英語期の比較的新しい借用語ということになる.英語は歴史を通じて常にラテン語と接触してきたという事情があり,しばしばいずれのケースかの判断は難しい.前代と後代とで語形や語義が異なっているなどの手がかりがあれば,再借用と認めることができるとはいえ,常にそのような手がかりが得られるわけでもない.

とりわけ650年以後の古英語期のラテン借用語に関して,判断の難しいケースが目立つ.昨日の記事 ([2019-10-21-1]) で眺めたように,一般的なレジスターに入っていなかったとおぼしき専門語な語彙が少なくない.これらの多くは地続きではなく後代の再借用ではないかと疑われる.

Durkin (131) は,650年以前のラテン借用語について,現代まで地続きで生き残ってきた可能性の高いものを次のように一覧している.

abbot; alms; anthem; ass; belt; bin; bishop; box; butter; candle; chalk; cheap; cheese; chervil; chest; cock; cockle (plant name); copper; coulter; cowl; cup; devil; dight; dish; fennel; fever; fork; fuller; inch; kiln; kipper; kirtle; kitchen; line; mallow; mass (= Eucharist); mat; (perhaps) mattock; mile; mill; minster; mint (for coinage); mint (plant name); -monger; monk; mortar; neep (and hence turnip); nun; pail; pall (noun); pan (if borrowed); pear; (probably) peel; pepper; pilch (noun); pile (= stake); pillow; pin; to pine; pipe; pit; pitch (dark substance); (perhaps) to pluck; (perhaps) plum; (perhaps) plume; poppy; post; (perhaps) pot; pound; priest; punt; purple; radish; relic; sack; Saturday; seine; shambles; shrine; shrive (and shrift, Shrove Tuesday); sickle; (perhaps) silk; sock; sponge; (perhaps) stop; street; strop (and hence strap); tile; toll; trivet; trout; tun; to turn; turtle-dove; wall; wine

このリストに,やや可能性は低くなるが,地続きと考え得るものとして次を追加している (131) .

anchor; angel; antiphon; arch-; ark; beet and beetroot; capon; cat; crisp; drake (= dragon, not duck); fan; Latin; lave; master; mussel; (wine-)must; pea; pine (the tree); plant; to plant; port; provost; psalm; scuttle; table; also (where the re-borrowing would be from early Scandinavian) kettle

続いて,650年以後のラテン借用語について,現代まで地続きであると根拠をもっていえる少数の語を次のように挙げている (132) .

aloe; cook; cope (= garment); noon; pole; pope; school; (if borrowed) fiddle; (in some of these cases re-borrowing in very early Middle English could also be possible)

そして,根拠がやや弱くなるが,650年以後のラテン借用語として現代まで地続きの可能性のあるものは次の通り (132) .

altar; canker; cap; clerk; comet; creed; deacon; false; flank; hyssop; lily; martyr; myrrh; to offer; palm (tree); paradise; passion; peony; pigment; prior; purse; rose; sabbath; savine; sot; to spend; stole; verse; also (where the re-borrowing would be from early Scandinavian) cole

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-10-21 Mon

■ #3829. 650年以後のラテン借用語の一覧 [lexicology][latin][loan_word][oe][borrowing]

「#3790. 650年以前のラテン借用語の一覧」 ([2019-09-12-1]) に続き,今回は反対の650年「以後」のラテン借用語を,Durkin (116--19) より列挙しよう.ただし,こちらは先の一覧と異なり網羅的ではない.あくまで一部を示すものなので注意.

650年以前と以後の借用語の傾向について比較すると,後者は学問・宗教と結びつけられる語彙が目立つことがわかるだろう.「#3787. 650年辺りを境とする,その前後のラテン借用語の特質」 ([2019-09-09-1]) も参照.

[ Religion and the Church ]

・ acolitus 'acolyte' [L acoluthus, acolitus]

・ altare, alter 'altar' [L altare]

・ apostrata 'apostate' [L apostata]

・ apostol 'apostle' [L apostrolus]

・ canon 'canon, rule of the Church; canon, cleric living under a canonical rule' [L canon]

・ capitol 'chapter, section; chapter, assembly' [L capitulum]

・ clauster 'monastic cell, cloister, monastery' [L claustrum]

・ cleric, also '(earlier) clīroc 'clerk, clergyman' [L clericus]

・ crēda, crēdo 'creed' [L credo]

・ crisma 'holy oil, chrism; white cloth or garment of the newly baptized; chrismatory or pyx' [L chrisma]

・ crismal 'chrism cloth' [L chrismalis]

・ crūc 'cross' [L cruc-, crux]

・ culpa 'fault, sin' [L culpa]

・ decan 'person who supervises a group of (originally) ten monks or nuns, a dean' [L decanus]

・ dēmōn 'devil, demon' [L aemon]

・ dīacon 'deacon' [L diaconus]

・ discipul 'disciple; follower; pupil' [L discipulus]

・ eretic 'heretic' [L haereticus]

・ graþul 'gradual (antiphon sung between the Epistle and the Gospel at Mass)' [L graduale]

・ īdol 'idol' [L idolum]

・ lētanīa 'litany' [L letania]

・ martir, martyr 'martyr' [L martyr]

・ noctern 'nocturn, night office' [L nocturna]

・ nōn 'ninth hour (approximately 3 p.m.); office said at this time' [L nona (hora)]

・ organ 'canticle, song, melody; musical instrument, especially a wind instrument'

・ orgel- (in orgeldrēam 'instrumental music') [L organum]

・ pāpa 'pope' [L papa]

・ paradīs 'paradise, Garden of Eden, heaven' [L paradisus]

・ passion 'story of the Passion of Christ' [L passion-, passio]

・ prīm 'early morning office of the Church' [L prima]

・ prior 'superior office of a religious house or order, prior' [L prior]

・ sabat 'sabbath' [L sabbata]

・ sācerd 'priest; priestess' [L sacerdos]

・ salm, psalm, sealm 'psalm, sacred song' [L psalma]

・ saltere, sealtere 'psalter, also type of stringed instrument' [L psalterium]

・ sanct 'holy person, saint' [L sanctus]

・ stōl, stōle 'long outer garment; ecclesiastical vestment' [L stola]

・ tempel 'temple' [L templum]

[ Learning and scholarship ]

・ accent 'diacritic mark' [L accentus]

・ bærbære 'barbarous, foreign' [L barbarus]

・ biblioþēce, bibliþēca 'library' [L bibliotheca]

・ cālend 'first day of the month; (in poetry) month' [L calendae]

・ cærte, carte '(leaf or sheet of) vellum; piece of writing, document, charter' [L charta, carta]

・ centaur 'centaur' [L centaurus]

・ circul 'circle, cycle' [L circulums]

・ comēta 'comet' [L cometa]

・ coorte, coorta 'cohort' [L cohort-, cohors]

・ cranic 'chronicle' [L chronicon or chronica]

・ cristalla, cristallum 'crystal; ice' [L crystallum]

・ epistol, epistola, pistol 'letter' [L epistola, epistula]

・ fers, uers 'verse, line of poetry, passage, versicle' [L versus]

・ gīgant 'giant' [L gigant- gigas]

・ grād 'step; degree' [L gradus]

・ grammatic-cræft 'grammar' [L grammatica]

・ legie 'legion' [L legio]

・ meter 'metre' [L metrum]

・ nōt 'note, mark' [L nota]

・ nōtere 'scribe, writer' [L notarius]

・ part 'part (of speech)' [L part-, pars]

・ philosoph 'philosopher' [L philosophus]

・ punct 'quarter of an hour' [L punctum]

・ tītul 'title, superscription' [L titulus]

・ þēater 'theatre' [L theatrum]

[ Plants, fruit, and products of plants ]

・ alwe 'aloe' [L aloe]

・ balsam, balzam 'balsam, balm' [L balsamum]

・ berbēne 'vervain, verbena' [L verbena]

・ cāl, cāul, cāwel (or cawel) 'cabbage' [L caulis]

・ calcatrippe 'caltrops, or another thorny or spiky plant' [L calcatrippa]

・ ceder 'cedar' [L cedrus]

・ coliandre, coriandre 'coriander' [L coliandrum, coriandrum]

・ cucumer 'cucumber' [L cucumer-, cucumis]

・ cypressus 'cypress' [L cypressus]

・ fēferfuge (or feferfuge), fēferfugie (or feferfugie) 'feverfew' [L febrifugia, with substitution of Old English fēfer or fefer for the first element]

・ laur, lāwer 'laurel, bay, laver' [L laurus]

・ lilie 'lily' [L lilium]

・ mōr- (in mōrberie, mōrbēam) 'mulberry' [L morus]

・ murre 'myrrh' [L murra, murrha, mytrrha]

・ nard 'spikenard (name of a plant and of ointment made from it)' [L nardus]

・ palm, palma, pælm 'palm (tree)' [L palma]

・ peonie 'peony' [L paeonia]

・ peruince, perfince 'periwinkle' [L pervinca]

・ petersilie 'parsley' [L ptetrosilenum, petrosilium, petresilium]

・ polente (or perhaps polenta) 'parched corn' [L polenta]

・ pyretre 'pellitory' (a plant) [L pyrethrum]

・ rōse (or rose) 'rose' [L rosa]

・ rōsmarīm, rōsmarīnum 'rosemary' [L rosmarinum]

・ safine 'savine (type of plant)' [L sabina]

・ salfie, sealfie 'sage' [L salvia]

・ spīce, spīca 'aromatic herb, spice, spikenard' [L spica]

・ stōr 'incense, frankincense' [probably L storax]

・ sycomer 'sycamore' [L sycomorus]

・ ysope 'hyssop' [L hyssopus]

[ Animals ]

・ aspide 'asp, viper' [L aspid-, aspis]

・ basilisca 'basilisk' [L basiliscus]

・ camel, camell 'camel' [L camelus]

・ *delfīn 'dolphin' [L delfin]

・ fenix 'phoenic; (in one example) kind of tree' [L phoenix]

・ lēo 'lion' [L leo]

・ lopust 'locust' [L locusta]

・ loppestre, lopystre 'lobster' [probably L locusta]

・ pndher 'panther' [L panther]

・ pard 'panther, leopard' [L pardus]

・ pellican 'name of a bird of the wilderness' [L pellicanus]

・ tiger 'tiger' [L tigris]

・ ultur 'vulture' [L vultur]

[ Medicine ]

・ ātrum, atrum, attrum 'black vitriol; atrament; blackness' [L atramentum]

・ cancer 'ulcerous sore' [L cancer]

・ flanc 'flank' [L *flancum]

・ mamme 'teat' [L mamma]

・ pigment 'drug' [L pigmentum]

・ plaster 'plaster (medical dressing), plaster (building material)' [L plastrum, emplastrum]

・ sċrofell 'scrofula' [L scrofula]

・ tyriaca 'antidote to poison' [L tiriaca, theriaca]

[ Tools and implements ]

・ pāl 'stake, stave, post, pole; spade' [L palus]

・ (perhaps) paper '(probably) wick' [L papirus, papyrus]

・ pīc 'spike, pick, pike' [perhals L *pic-]

・ press 'press (specifically clothes-press)' [L pressa or French presse]

[ Building and construction; settlements ]

・ castel, cæstel 'village, small town; (in late manuscripts) castle' [L castellum]

・ foss 'ditch' [L fossa]

・ marman-, marmel- (in marmanstān, marmelstān 'marble' [L marmor]

[ Receptacles ]

・ purs, burse 'purse' [L bursa]

[ Money; units of measurement ]

・ cubit 'cubit, measure of length' [L cubitum]

・ mancus 'a money of account equivalent to thirty pence, a weight equivalent to thirty pence' [L mancus]

・ talente 'talent (as unit of weight or of money)' [L talentum]

[ Clothing ]

・ cæppe, also (in cantel-cāp 'cloak worn by a cantor') cāp 'cloak, hood, cap' (with uncertain relationship to cōp in the same meaning) [L cappa]

・ tuniċe, tuneċe 'undergarment, tunic, coat, toga' [L tunica]

[ Roles, ranks, and occupations (non-religious or not specifically religious) ]

・ centur, centurio, centurius 'centurion' [L centurion-, centurio]

・ cōc 'cook' [L *cocus, coquus]

・ consul 'consul' [L consul]

・ fiþela 'fiddler' (also fiþelere 'fiddler', fiþelestre '(female) fiddler') [probably L vitula]

[ Warfare ]

・ mīlite 'soldiers' [L milites, plural of miles]

[ Verbs ]

・ acordan 'to reconcile' [perhaps L accordare, although more likely a post-Conquest borrowing from French]

・ acūsan 'to accuse (someone)' [L accusare]

・ ġebrēfan 'to set down briefly in writing' [L breviare]

・ dēclīnian 'to decline or inflect' [L declinare]

・ offrian 'to offer, sacrifice' [L offerre]

・ *platian 'to make or beat into thin plates' (implied by platung 'metal plate' and ġeplatod and aplatod 'beaten into thin plates') [L plata, noun]

・ predician 'to preach' [L predicare, praedicare]

・ prōfian 'to assume to be, to take for' [L probare]

・ rabbian 'to rage' [L rabiare]

・ salletan 'to sing psalms, to play on the harp' [L psallere]

・ sċrūtnian, sċrūdnian 'to examine' [L scrutinare]

・ *spendan 'to spend' (recorded in Old English only in the derivatives spendung, aspendan, forspendan) [L expendere]

・ studdian 'to look after, be careful for' [L studere]

・ temprian 'to modify; to cure, heal; to control' [L temperare]

・ tonian 'to thunder' [L tonare]

[ Adjectives ]

・ fals 'false' [L falsus]

・ mechanisċ 'mechanical' [L mechanicus]

[ Miscellaneous ]

・ fals 'fraud, trickery' [L falsum]

・ rocc (only in stānrocc) 'cliff or crag' [L rocca]

・ sott 'fool', also adjective 'foolish' [L sottus]

・ tabele, tabul, tabule 'tablet, board; writing tablet; gaming table' [L tabula]

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-28 Sat

■ #3806. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第4回「ゲルマン民族の大移動」のご案内 [asacul][notice][latin][roman_britain]

2週間先のことになりますが,10月12日(土)の15:15?18:30に,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて「英語の歴史と語源・4 ゲルマン民族の大移動」と題する講演を行ないます.ご関心のある方は,こちらよりお申し込みください.過去3回ともに大勢の方にご参加いただき,活発な議論の時間をもつことができましたので,今回も楽しみにしています.今回の趣旨は以下の通りです.

紀元449年,ゲルマン民族の大移動の一環として,西ゲルマン語群に属するアングル人,サクソン人,ジュート人がブリテン島に渡来しました.彼らの母語こそが英語であり,この時期をもって英語の歴史も本格的に始動します.イングランドを築いた彼らは,ゲルマン的なアングロサクソン文化を開花させますが,その文化を支えた「古英語」はいまだゲルマン的色彩の濃い言語的特徴を保っていました.今回も本シリーズの趣旨に沿い,現代まで受け継がれてきた古英語の豊かな語彙的遺産を中心に鑑賞していきましょう.

講座では「ゲルマン民族の大移動とアングロ・サクソンの渡来」「古英語の語彙」「現代に残る古英語の語彙的遺産」というラインナップで,英語語彙のコアを形成している本来語の資産について,詳しく論じる予定です.予習として,anglo-saxon や oe の各記事をご覧ください.

2019-09-14 Sat

■ #3792. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第3回「ローマ帝国の植民地」を終えました [asacul][notice][latin][roman_britain][etymology][slide][link]

「#3781. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第3回「ローマ帝国の植民地」のご案内」 ([2019-09-03-1]) で紹介したとおり,9月7日(土)15:15?18:30に朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて「英語の歴史と語源・3 ローマ帝国の植民地」と題する講演を行ないました.過去2回と同様,大勢の方々に参加いただきまして,ありがとうございました.核心を突いた質問も多数飛び出し,私自身もおおいに勉強になりました. *

今回は,(1) ローマン・ブリテンの時代背景を紹介した後,(2) 同時代にはまだ大陸にあった英語とラテン語の「馴れ初め」及びその後の「腐れ縁」について概説し,(3) 最初期のラテン借用語が意外にも日常的な性格を示す点に注目しました.

特に3点目については,従来あまり英語史で注目されてこなかったように思われますので,具体例を挙げながら力説しました.ラテン借用語といえば,語彙の3層構造のトップに君臨する語彙として,お高く,お堅く,近寄りがたいイメージをもってとらえられることが多いのですが,こと最初期に借用されたものには現代でも常用される普通の語が少なくありません.ラテン語に関するステレオタイプが打ち砕かれることと思います.

講座で用いたスライド資料をこちらに置いておきます.本ブログの関連記事へのリンク集にもなっていますので,復習などにお役立てください.

次回の第4回は10月12日(土)15:15?18:30に「英語の歴史と語源・4 ゲルマン民族の大移動」と題して,いよいよ「英語の始まり」についてお話しする予定です.

1. 英語の歴史と語源・3 「ローマ帝国の植民地」

2. 第3回 ローマ帝国の植民地

3. 目次

4. 1. ローマン・ブリテンの時代

5. ローマン・ブリテンの地図

6. ローマン・ブリテンの言語状況 (1) --- 複雑なマルチリンガル社会

7. ローマン・ブリテンの言語状況 (2) --- ガリアとの比較

8. ローマ軍の残した -chester, -caster, -cester の地名

9. 多くのラテン地名が後にアングロ・サクソン人によって捨てられた理由

10. 2. ラテン語との「腐れ縁」とその「馴れ初め」

11. ラテン語との「腐れ縁」の概観

12. 現代英語におけるラテン語の位置づけ

13. 3. 最初期のラテン借用語の意外な日常性

14. 行為者接尾辞 -er と -ster も最初期のラテン借用要素?

15. 古英語語彙におけるラテン借用語比率

16. 借用の経路 --- ラテン語,ケルト語,古英語の関係

17. cheap の由来

18. pound (?) の由来

19. Saturday とその他の曜日名の由来

20. まとめ

21. 参考文献

2019-09-13 Fri

■ #3791. 行為者接尾辞 -er, -ster はラテン語に由来する? [suffix][latin][etymology][productivity][word_formation][agentive_suffix]

標題の2つの行為者接尾辞 (agentive suffix) について,それぞれ「#1748. -er or -or」 ([2014-02-08-1]),「#2188. spinster, youngster などにみられる接尾辞 -ster」 ([2015-04-24-1]) などで取り上げてきた.

-er は古英語では -ere として現われ,ゲルマン諸語にも同根語が確認される.そこからゲルマン祖語 *-ārjaz, *-ǣrijaz が再建されているが,さらに遡ろうとすると起源は判然としない.Durkin (114) によれば,ラテン語 -ārius, -ārium, -āria の借用かとのことだ(このラテン語接尾辞は別途英語に形容詞語尾 -ary として入ってきており,budgetary, discretionary, parliamentary, unitary などにみられる).

一方,もともと女性の行為者を表わす古英語の接尾辞 -estre, -istre も限定的ながらもいくつかのゲルマン諸語にみられ,ゲルマン祖語形 *-strjōn が再建されてはいるが,やはりそれ以前の起源は不明である.Durkin (114) は,こちらもラテン語の -istria に由来するのではないかと疑っている.

もしこれらの行為者接尾辞がラテン語から借用された早期の(おそらく大陸時代の)要素だとすれば,後の英語の歴史において,これほど高い生産性を示すことになったラテン語由来の形態素はないだろう.特に -er についてはそうである.これが真実ならば,「#3788. 古英語期以前のラテン借用語の意外な日常性」 ([2019-09-10-1]) で述べたとおり,最初期のラテン借用要素のもつ日常的な性格を裏書きするもう一つの事例となる.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-12 Thu

■ #3790. 650年以前のラテン借用語の一覧 [lexicology][latin][loan_word][oe][borrowing]

過去3日間の記事(「#3787. 650年辺りを境とする,その前後のラテン借用語の特質」 ([2019-09-09-1]),「#3788. 古英語期以前のラテン借用語の意外な日常性」 ([2019-09-10-1]),「#3789. 古英語語彙におけるラテン借用語比率は1.75%」 ([2019-09-11-1]))でも触れたように,650年辺りより前にラテン語から英語へ流入した単語には,意外と日常的なものが多く含まれている.

これを確認するには,具体的な単語一覧を眺めてみるのが一番だ.Durkin (107--16) を参照して,以下に,意味の分野ごとに,各々の単語について古英語の借用形,現代の対応語(あるいは語義),ラテン語形を示す.先頭に "?" を付している語は,早期の借用語であると強い根拠をもっては認められない語である.

[ Religion and the Church ]

・ abbod, abbot 'abbot' [L abbat-, abbas]

・ abbodesse 'abbess' [L abbatissa]

・ antefn, also (later) antifon, antyfon 'antiphon (type of liturgical chant)' [L antifona, antefona]

・ ælmesse, ælmes 'alms, charity' [L *alimosina, variant of elemosina]

・ bisċeop 'bishop' [probably L episcopus]

・ cristen 'Christian' [L christianus]

・ dēofol, dīofol 'devil' [perhaps Latin diabulus]

・ draca 'dragon, monstrous beast; the devil' [L draco]

・ engel, angel 'angel' [probably L angelus]

・ mæsse, messe 'mass' (the religious ceremony) [L missa]

・ munuc 'monk' [L monachus]

・ mynster 'monastery; importan church' [L monasterium]

・ nunne 'nun' [L nonna]

・ prēost 'priest' [probably L *prebester, presbyter]

・ senoð, seonoð, sinoð, sionoð 'council, synod, assembly' [L synodus]

・ ? ancra, ancor 'anchorite' [L anachoreta, perhaps via Old Irish anchara]

・ ? ærċe-, erċe-, arce- 'arch-' (in titles) [L archi-]

・ ? relic- (in relicgang (probably) 'bearing of relics in a procession') [clipping of L reliquiae or OE reliquias]

・ ? reliquias 'relics' [L reliquiae]

[ Learning and scholarship ]

・ Læden 'Latin; any foreign language', also (later) lātin [L Latina]

・ sċolu, also (later) scōl 'troop, band; school' [L schola]

・ ? græf 'stylus' [L graphium]

・ ? stǣr (or stær) 'history' [probably ultimately L historia, perhaps via Celtic]

・ ? traht 'text, passage, commentary' [L tractus]

・ ? trahtað 'commentary' [L tractatus]

[ Plants, fruit, and products of plants ]

・ bēte 'beet, beetroot' [L beta]

・ billere denoting several water plants [L berula]

・ box 'box tree', later also 'box, receptable' [L buxus]

・ celendre, cellendre 'coriander' [L coliandrum]

・ ċerfille, ċerfelle 'chervil' [L caerefolium]

・ *ċiċeling 'chickpea' [L cicer]

・ ċīpe 'onion' [L cepe]

・ ċiris-(bēam) 'cherry tree' [L *ceresia, cerasium]

・ ċisten-, ċistel-, ċist-(bēam) 'chestnut tree' [L castinea or castanea]

・ coccel 'corn cockle, or other grain-field weed' [L *cocculus < coccum]

・ codd-(æppel) 'quince' [L cydonium, cotoneum, or cotonium]

・ consolde '(perhaps) daisy or comfrey' [L consolida]

・ corn-(trēo) 'cornel tree' [L cornus]

・ cost 'costmary' [L constum]

・ cymen 'cumin' [L cuminum]

・ cyrfet 'gourd' [L cucurbita]

・ earfe plant name, probably vetch [L ervum]

・ elehtre '(probably) lupin' [L electrum]

・ eofole 'dwarf elder, danewor' [L ebulus]

・ eolone, elene 'elecampane' (a plant) [L inula, helenium]

・ finol, finule, finugle 'fennel' [L fenuculum]

・ glædene a plant name (usually for a type of iris) [L gladiola]

・ humele 'hop plant' [L humulus]

・ lāser 'weed, tare' [L laser]

・ leahtric, leahtroc, also (later) lactuce 'lettuce' [L lactuca]

・ *lent 'lentil' [L lent-, lens]

・ lufestiċe 'lovage' [L luvesticum]

・ mealwe 'mallow' [L malva]

・ *mīl 'millet' [L milium]

・ minte, minta 'mint' [L mentha]

・ næp 'turnip' [L napus]

・ nefte 'catmint' [L nepeta]

・ oser or ōser 'osier' [L osaria]

・ persic 'peach' [L persicum]

・ peru 'pear' [L pirum, pera]

・ piċ 'pitch' (the resinous substance) [L pic-, pix]

・ pīn 'pine' [L pinus]

・ pipeneale 'pimpernel' [L pipinella]

・ pipor 'pepper' [L piper]

・ pieir 'pear tree' [L *pirea]

・ pise, *peose 'pea' [L pisum]

・ plūme 'plum; plum tree' and plȳme 'plum; plum tree' [both perhaps L pruna]

・ pollegie 'penny-royal' [L pulegium]

・ popiġ, papiġ 'poppy' [L papaver]

・ porr 'leek' [L porrum]

・ rǣdiċ 'radish' [L radic-, radix]

・ rūde 'rue' [L ruta]

・ syrfe 'service tree' [L *sorbea, sorbus]

・ ynne- (in ynnelēac) 'onion' [L unio]

・ ? æbs 'fir tree' [L abies]

・ ? croh, crog 'saffron; type of dye; saffron colour' [L crocus]

・ ? fīċ 'fig tree, fig' [L ficus]

・ ? plante 'young plant' [L planta]

・ ? sæðerie, satureġe 'savory (plant name)' [L satureia]

・ ? sæppe 'spruce fir' [L sappinus]

・ ? sōlsēċe 'heliotrope' [L solsequium, with substitution of a derivative of OE sēċan 'to seek' for the second element]

[ Animals ]

・ assa 'ass' [L asinum perhaps via Celtic]

・ capun 'capon' [probably L capon-, capo]

・ cat, catte 'cat' [L cattus]

・ cocc 'cock, rooster' [L coccus]

・ *cocc (in sǣcocc) 'cockle' [perhaps L *coccum]

・ culfre 'dove' [perhals L columbra, columbula]

・ cypera 'salmon at the time of spawning' [L cyprinus]

・ elpend, ylpend 'elephant', also shortend to ylp [L elephant-, elephans]

・ eosol, esol 'ass' [L asellus]

・ lempedu, also (later) lamprede 'lamprey' [L lampreda]

・ mūl 'mule' [L mulus]

・ muscelle 'mussel' [L musculus]

・ olfend 'camel' [probably L elephant-, elephans, with the change in meaning arising from semantic confusion]

・ ostre 'oyster' [L ostrea]

・ pēa 'peafowl' [L pavon-, pavo]

・ *pine- (in *pinewincle, as suggested emendation of winewincle) 'wincle' [perhals L pina]

・ rēnġe 'spider' [L aranea]

・ strȳta 'ostrich' [L struthio]

・ trūht 'trout' [L tructa]

・ turtle, turtur 'turtle dove' [L turtur]

[ Food and drink (see also plants and animals) ]

・ ċȳse, ċēse 'cheese' [L caseus]

・ foca 'cake baked on the ashes of the hearth' (only attested with reference to Biblical contexts or antiquity) [L focus]

・ must 'wine must, new wine' [L mustum]

・ seim 'lard, fat' (only attested in figurative use) [L *sagimen, sagina]

・ senap, senep 'mustard' [L sinapis]

・ wīn 'wine' [L vinum]

[ Medicine ]

・ butere 'butter' [L butyrum, buturum]

・ ċeren 'wine reduced by boiling for extra sweetness' [L carenum]

・ eċed 'vinegar' [L acetum]

・ ele 'oil' [L oleum]

・ fēfer or fefer 'fever' [L febris]

・ flȳtme 'lancet' [L fletoma]

[ Transport; riding and horse gear ]

・ ancor, ancra 'anchor (also in figurative use)' [L ancora]

・ cæfester 'muzzle, halter, bit' [L capistrum, perhaps via Celtic]

・ ċæfl 'muzzle, halter, bit' [L capulus]

・ ċearricge (meaning very uncertain, perhaps 'carriage') [perhaps L carruca]

・ punt 'punt' [L ponton-, ponto]

・ sēam 'burden; harness; service which consisted in supplying beasts of burden' [L sauma, sagma]

・ stǣt 'road; paved road, street' [L strata]

[ Tools and implements ]

・ cucler 'spoon' [L coclear]

・ culter 'coulter; (once) dagger' [L culter]

・ fæċele 'torch' [L facula]

・ fann 'winnowing fan' [L vannus]

・ forc, forca 'fork' [L furca]

・ *fossere or fostere 'spade' [L fossorium]

・ inseġel, insiġle 'seal; signet' [L sigillum]

・ līne 'cable, rope, line, cord; series, row, rule, direction' [probably L linea]

・ mattuc, meottuc, mettoc 'mattock' [perhaps L *matteuca]

・ mortere 'mortar' [L mortarium]

・ panne 'pan' [perhaps L panna]

・ pæġel 'wine vessel; liquid measure' [L pagella]

・ pihten part of a loom [L pecten]

・ pīl 'pointed object; dart, shaft, arrow; spike, nail; stake' [L pilum]

・ pīle 'mortar' [L pila]

・ pinn 'pin, peg, pointer; pen' [probably L penna]

・ pīpe 'tube, pipe; pipe (= wind instrument); small stream' [L pipa]

・ pundur 'counterpoise; plumb line' [L ponder-, pondus]

・ seġne 'fishing net' [L sagena]

・ sicol 'sickle' [L *sicula, secul < secare 'to cut']

・ spynġe, also (later) sponge 'sponge' [L spongia, spongea]

・ timple instrument used in weaving [L templa]

・ turl 'ladele' [L trulla]

・ ? stropp 'strap' [L stroppus or struppus]

・ ? trefet 'trivet, tripod' [L tripes]

[ Warware and weapons ]

・ camp 'battle; war; field' [L campus]

・ cocer 'quiver' [perhaps L cucurum]

[ Buildings and parts of buildings; construction; towns and settlements ]

・ ċeafor-(tūn), cafer-(tūn) 'hall, court' [L capreus]

・ ċealc, calc 'chalk, plaster' [L calc-, calx]

・ ċeaster, ċæster 'fortification; city, town (especially one with a wall)' [L castra]

・ ċipp 'rod, stick, beam (especially in various specific contexts)' [probably L cippus]

・ clifa, cleofa, cliofa 'chamber, cell, den, lair' [perhaps L clibanus 'oven']

・ clūse, clause 'lock; confine, enclosure; fortified pass' [L clausa]

・ clūstor 'lock, bolt, bar, prison' [L claustrum]

・ cruft 'crypt, cave' [L crupta]

・ cyċene 'kitchen' [L coquina]

・ cylen 'kiln, oven' [L culina]

・ *cylene 'town' (only as place-name element) [L colonia]

・ mūr 'wall' [L murus]

・ mylen 'mill' [L molina]

・ pearroc 'enclosure; fence that forms an enclosure' [perhaps L parricus]

・ pīsle or pisle 'warm room' [L pensilis]

・ plætse, plæce, plæse 'open place in a town, square, street' [L platea]

・ port 'town with a harbour; harbour, port; town (especially one with a wall or a market)' [L portus]

・ post 'post; doorpost' [L postis]

・ pytt 'hole in the ground; excavated hole; pit; grave; hell' [pherlaps L puteus]

・ sċindel 'roof shingle' [L scindula]

・ solor 'upper room; hall, dwelling; raised platform' [L solarium]

・ tīġle, tīgele, tigele 'earthen vessel; potshert; tile, brick' [L tegula]

・ torr 'tower' [L turris]

・ weall 'wall, rampart, earthwork' [L vallum]

・ wīċ 'dwelling; village; camp, fortress' [L visum]

・ ? port 'gate, gateway' [L porta]

・ ? prtiċ 'porch, portico, vestibule, chapel' [L poorticus]

[ Containers, vessels, and receptacles ]

・ amber 'vessel, dry or liquid measure' [L amphora, ampora]

・ binn, binne 'basket, bin; manger' [L benna]

・ buteruc 'bottle' [perhaps from a derivative of L buttis]

・ byden 'vessel, container; cask, tub; tub-shaped geographical feature' [probably L *butina]

・ bytt 'bottle, flask, cask, wine skin' [L *buttia]

・ ċelċ, cælc, calic 'drinking vessel, cup' [L calic-, calix]

・ ċist, ċest 'chest, box, coffer; reliquary; coffin' [L cista]

・ cuppe 'cup', also copp 'cup, beaker; gloss for Latin spongia sponge' [L cuppa]

・ cȳf 'large jar, vessel, or tub' [L cupia < cupa]

・ cȳfl 'tub, bucket' [L cupellus]

・ cyll, cylle 'leather bottle, leather bag; ladele; oil lamp' [L culleus]

・ disċ 'dish, bowl, plate' [L discus]

・ earc, earce, earca, also arc, arce, arca 'ark (especially Noah's ark or the ark of the covenent), chest, coffer' [L arca]

・ gabote, gafote kind of dish or platter [L gabata]

・ ġellet 'jug, bowl, or basin' [L galleta]

・ læfel, lebil 'spoon, cup, bowl, vessel' [L labellum]

・ orc 'pitcher, crock, cup' [L orca]

・ pott 'pot' [perhaps L pottus]

・ sacc, also sæcc 'sack, bag' [L saccus]

・ sester 'jar, vessel; a measure' [L sextarius]

・ spyrte 'basket' [probably L sporta, *sportea]

・ ? cæpse 'box' [L copsa]

・ ? sċrīn 'chest; shrine' [L scrinium]

・ ? sċutel 'dish, platter' [L scutella]

・ ? tunne 'cask, tun, barrel' [L tunna]

[ Coins, money; wights and measures, units of measurement ]

・ dīner, dīnor type of coin, denarius [L denarius]

・ mīl 'mile' [L milia]

・ mydd 'a measure' [L modius]

・ mynet 'a coin; coinage, money' [L moneta]

・ oma 'a liquid measure' [L ama]

・ pund 'pound (in weight or money); pint' [L pondo]

・ trimes 'unit of weight, a dracm; name of a coin' [L tremissis]

・ ynċe 'inch' [L uncia]

・ yntse 'ounce' [L uncia]

[ Transactions and payments ]

・ ċēap 'perchase, sale, transaction, market, possessions, price' [L cauō or caupōnārī]

・ toll, also toln, tolne 'toll, tribute, rent, duty' [L toloneum]

・ trifet 'tribute' [L tributum]

[ Clothing; fabric ]

・ belt 'belt, girdle' [L balteus]

・ bīsæċċ 'pocket' [L bisaccium]

・ cælis 'foot-covering', also (later) calc 'sandal' [L calceus]

・ ċemes 'shirt, undergarment' [L camisia]

・ ġecorded 'having cords, corded (or perhaps fringed)' [L corda]

・ cugele '(monk's) cowl' [L cuculla]

・ fifele 'broach, clasp' [L fibula]

・ mentel 'cloak' [L mantellum]

・ pæll, pell 'fine or rich cloth; purple cloth; altar cloth rich robe' [L pallium]

・ pyleċe 'fur robe' [L pellicia]

・ seolc 'silk' [perhaps L sericum]

・ sīde 'silk' [L seta]

・ *sīric 'silk' [perhals L sericum]

・ socc 'light shoe' [L soccus]

・ swiftlēre 'slipper' [L subtalaris]

・ ? orel, orl 'robe, garment, veil, mantle' [L orale, orarium]

・ ? purpure, purpur 'deep crimson garment; deep crimson colour (imperial purple)' [L purpura]

・ ? sabon 'sheet' [L sabanum]

・ ? tæpped, teped 'cloth wall or floor covering' [L tapetum, tappetum]

[ Furniture and furnishing ]

・ meatte, matte 'mat; underlay for a bed' [L matta]

・ mēse, mīse 'table' [L mensa]

・ pyle, pylu 'pillow, cushion' [L pulvinus]

・ sċamol, sċemol, sċeomol, sċeamol 'stool, footstool, bench' [L *scamellum]

・ strǣl, strēaġl 'curtain; quilt, matting, bed' [L stragula]

・ strǣt 'bed' [L stratum]

[ Precious stones ]

・ ġimm 'gem, precious stone, jewel; also in figurative use' [L gemma]

・ meregrot 'pearl' [L margarita, but showing folk-etymological alteration after an English word for 'sea' and (probably) an English word for 'fragment, particple']

・ pærl '(very doubtfully) pearl' [perhals L *perla]

[ Roles, ranks, and occupations (non-religious or not specifically religious) ]

・ cāsere 'emperor; ruler' [L caesar]

・ fullere 'fuller' [L fullo]

・ mangere 'merchant, trader' [L mango]

・ mæġester, also (later) māgister or magister 'leader, master, teacher' [L magister]

・ myltestre 'prostitute' [L meretrix, with remodelling of the ending after the Old English feminine agent noun suffix -estre]

・ prafost, also profost 'head, chief, officer' [L praepositus, propositus]

・ sūtere 'shoumaker' [L sutor]

[ Punishment, judgement, codes of behaviour ]

・ pīn 'pain, fortune, anguish, punishment' [L poena]

・ regol, reogol 'rule; principle; code of rules; wooden ruler' [L regula]

・ sċrift 'something decreed as a penalty; penance; absolution; confessor; judge' [L scriptum]

[ Verbs ]

・ *cōfrian 'to recover' (implied by acōfrian in the same meaning) [L recuperare]

・ *cyrtan 'to shorten' (implied by cyrtel 'garment, tunic, cloak, gown' and (probably) ġecyrted 'cut off, shortened') [L curtus, adjective]

・ dīligian 'to erase, rub out; to destroy, obliterate' [L delere]

・ impian 'to graft; to busy oneself with' [L imputare]

・ *mūtian (implied by bemūtian 'to exchange' and mūtung 'exchange') [L mutare]

・ *nēomian 'to sound sweetly' or *nēome 'sound' [L neuma, noun]

・ pinsian 'to weigh, consider, reflect' [L pensare]

・ pīpian 'to play on a pipe' [L pipare]

・ pluccian 'to pluck' [perhaps L *piluccare]

・ *pundrian (implied by apyndrian, apundrian 'to weigh, to adjudge') [L ponderare, if not a derivative of OE punduru]

・ pynġan 'to prick' [L pungere]

・ sċrīfan 'to allot, prescribe, impose; to hear confession; to receive absolution; to have regard to' [L scribere]

・ seġlian 'to seal' [L sigillare]

・ seġnian 'to make the sign of the cross; to consecrate, bless' [L signare, if not < OE seġn]

・ *-stoppian (implied by forstoppian) 'to obstruct, stop up' [perhaps L *stuppare]

・ trifulian 'to break, bruise, stamp' [L tribulare]

・ tyrnan, turnian 'to turn, revolve' [L turnare]

・ ? cystan 'to get the value of, exchange for the worth of' [L constare]

・ ? dihtan, dihtian 'to direct, command, arrange, set forth' [L dictare]

・ ? glēsan 'to gloss, explain' [L glossare (verb) or glossa (noun)]

・ ? lafian 'to pour water on, to bathe, wash' [L lavare]

・ ? *pilian 'to peel, strip, pluck' [L pilare]

・ ? plantian 'to plant' [L plantare, or < OE plante]

・ ? *pyltan 'to pelt' (implied by later pilt, pelt) [perhaps L *pultiare, alteration of pultare]

・ ? sealtian 'to dance' [L saltare]

・ ? trahtian 'to comment on, expound; to interpret' [L tractare, if not < OE traht]

[ Adjectives ]

・ cirps, crisp 'curly, curly haired' [L crispus]

・ cyrten 'beautiful' [perhals L *cortinus]

・ pīs 'heavy' [L pensus]

・ sicor 'sure, certain; secure' [L securus]

・ sȳfre 'clean, pure, sober' [L sobrius]

・ byxen 'of box wood' [probably L buxeus]

・ ? cūsc 'virtuous, chaste' [L conscius, perhaps via Old Saxon kusko]

[ Miscellaneous ]

・ candel, condel 'candle, taper', (in figurative contexts) 'source of light' [L candela]

・ ċēas, ċēast 'quarrel, strife; reproof' [L causa]

・ ċeosol, ċesol 'hut; gullet; belly' [L casula, casella]

・ copor 'copper' [L cuprum]

・ derodine 'scarlet' [probably L dirodinum]

・ munt 'mountain, hill' [L mont-, mons]

・ plūm-, in plmfeðer '(inplural) down, feathers' [L pluma]

・ sælmeriġe 'brine' [L *salmuria]

・ sætern- (in sæterndæġ 'Saturday') [L Saturnus]

・ seġn 'mark, sign, banner' [L signum]

・ tasul, teosol 'dice; small square of stone' [L tessella, *tassellus]

・ tæfl 'piece used in a board game, dice; type of game played on a board, game of dice; board on which this is played' [L tabula]

・ -ere, forming agent nouns [probably L -arius; if so, borrowed early]

・ -estre, forming feminine agent nouns [perhaps L -istria]

・ ? coron-(bēag) 'crown' [L corona]

・ ? diht 'act of directing or arranging; direction, arrangement, command' [L dictum]

・ ? *pill (perhaps shown by pillsāpe soap for removing hair, depilatory) [perhals L pilus 'hair']

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-11 Wed

■ #3789. 古英語語彙におけるラテン借用語比率は1.75% [latin][loan_word][borrowing][oe][lexicology][statistics]

英語語源学の第一人者 Durkin によれば,古英語期までに英語に借用されたラテン単語の数は,少なくとも600語はあるという.650年辺りを境に,前期に300語ほど,後期に300語ほどという見立てである.この600という数字を古英語語彙全体から眺めてみると,1.75%という割合がはじき出される.しかし,これらのラテン借用語単体ではなく,それに基づいて作られた合成語や派生語までを考慮に入れると,古英語語彙における割合は4.5%に跳ね上がる.Durkin (100) の解説を引用しよう.

If we take an estimate of at least 600 words borrowed (immediately) from Latin, and a total of around 34,000 words in Old English, then, conservatively, around 1.75% of the total are borrowed from Latin. If we include all compounds and derivatives formed on Latin loanwords in Old English, then the total of Latin-derived vocabulary probably comes closer to 4.5% . . . , although this figure may be a little too high, since estimates of the total size of the Old English vocabulary (native and borrowed) probably rather underestimate the numbers of compounds and derivatives.

この数値をどう評価するかは視点の取り方次第である.後の歴史における英語の語彙借用の規模とその影響を考えれば,この段階でのラテン借用語の割合など,取るに足りない数字にみえるだろう.一方,これこそが英語の語彙借用の歴史の第一歩であるとみるならば,いわば0%から出発した借用語の比率が,すでに古英語期中に1.75%(あるいは4.5%)に達しているというのは,ある程度著しい現象であるといえなくもない.さらにいえば,その多くが千数百年を隔てた現代英語にも残っており,日常語として用いられているものも目立つのである(昨日の記事「#3788. 古英語期以前のラテン借用語の意外な日常性」 ([2019-09-10-1]) を参照).

古英語のラテン借用語については英語史研究においてもさほど注目されてきたわけではないが,見方を変えれば十分に魅力的なトピックになりそうだ.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-10 Tue

■ #3788. 古英語期以前のラテン借用語の意外な日常性 [latin][loan_word][oe][lexicology][lexical_stratification][statistics][borrowing]

昨日の記事「#3787. 650年辺りを境とする,その前後のラテン借用語の特質」 ([2019-09-09-1]) で触れたように,古英語期以前,とりわけ650年より前に入ってきた最初期のラテン借用語には,現在でも日常的に用いられているものが多い.「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]) などで見てきたように,ラテン借用語にはレベルの高い単語が多いのは事実だが,古英語期以前の借用語に関していえば,そのステレオタイプは必ずしも事実を表わしていない.

Durkin (138--39) による興味深い数値がある.Durkin は,「#3400. 英語の中核語彙に借用語がどれだけ入り込んでいるか?」 ([2018-08-18-1]) でも示したとおり,"Leipzig-Jakarta list of basic vocabulary" と呼ばれる通言語的に最も基本的な意味を担う100語を現代英語から取り出し,そのなかにどれほど借用語が含まれているかを調査してみた.結果としては,ラテン借用語についていえば,そこには1語も含まれていなかった.

しかし,別途 "the WOLD survey" による1,460個の基本的な意味項目からなる日常語リストで調査してみると,137語ほど(およそ10%)が古英語期以前に借用されたラテン借用語と認定されるものだった.しかも,それらの単語は,24個設けられている意味のカテゴリーのうち,"Kinship", "Quantity", "Miscellaneous function words" を除く21個のカテゴリーにわたって見出されるという.つまり,英語史上,最初期に入ってきたラテン借用語は,広い分野にわたり日常的に用いられる英語の語彙の少なからぬ部分を構成しているというわけだ.古英語の形で具体例をいくつか挙げておこう.

・ butere "butter"

・ ele "oil"

・ cyċene "kitchen"

・ ċȳse, ċēse "cheese"

・ wīn "wine" (and its compounds)

・ sæterndæġ "Saturday"

・ mūl "mule"

・ ancor "anchor"

・ līn "line, continuous length"

・ mylen (and its compounds) "mill"

・ scōl, sċolu (and the compound leornungscōl) "school"

・ weall "wall"

・ pīpe "pipe, tube"

・ pīle "mortar"

・ disċ "plate/platter/bowel/dish"

・ candel "lamp, lantern, candle"

・ torr "tower"

・ prēost and sācerd "priest"

・ port "harbour"

・ munt "mountain or hill"

このようにラテン借用語のなかには意外と多く「基本語彙」もあることを銘記しておきたい.関連して,基本語彙の各記事も参照.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-09 Mon

■ #3787. 650年辺りを境とする,その前後のラテン借用語の特質 [latin][loan_word][oe][chronology][lexicology][borrowing][link]

英語史におけるラテン借用語といえば,古英語期のキリスト教用語,初期近代英語期のルネサンス絡みの語彙(あるいは「インク壺用語」 (inkhorn_term)),近現代の専門用語を中心とする新古典主義複合語などのイメージが強い.要するに「堅い語彙」というステレオタイプだ.本ブログでも,それぞれ以下の記事で取り上げてきた.

・ 「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1])

・ 「#296. 外来宗教が英語と日本語に与えた言語的影響」 ([2010-02-17-1])

・ 「#1895. 古英語のラテン借用語の綴字と借用の類型論」 ([2014-07-05-1])

・ 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1])

・ 「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1])

・ 「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1])

・ 「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1])

・ 「#1615. インク壺語を統合する試み,2種」 ([2013-09-28-1])

・ 「#3157. 華麗なる splendid の同根類義語」 ([2017-12-18-1])

・ 「#3438. なぜ初期近代英語のラテン借用語は増殖したのか?」 ([2018-09-25-1])

・ 「#3013. 19世紀に非難された新古典主義的複合語」 ([2017-07-27-1])

・ 「#3179. 「新古典主義的複合語」か「英製羅語」か」 ([2018-01-09-1])

俯瞰的にいえば,このステレオタイプは決して間違いではないが,日常的で卑近ともいえるラテン借用語も存在するという事実を忘れてはならない.大雑把にいえば紀元650年辺りより前,つまり大陸時代から初期古英語期にかけて英語(あるいはゲルマン諸語)に入ってきたラテン単語の多くは,意外なことに,よそよそしい語彙ではなく,日々の生活になくてはならない語彙を構成しているのである.この事実は「ラテン語=威信と教養の言語」という等式の背後に隠されているので,よく確認しておくことが必要である.

650年というのはおよその年代だが,この前後の時代に入ってきたラテン借用語のタイプは異なっている.単純化していえば,それ以前は「親しみのある」日常語,それ以降は「お高い」宗教と学問の用語が入ってきた.Durkin (103) の要約文を引用しよう.

The context for most of the later borrowings is certain: they are nearly all words connected with the religious world or with learning, which were largely overlapping categories in the Anglo-Saxon world. Many of them are only very lightly assimilated into Old English, if at all. In fact it is debatable whether some of them should even be regarded as borrowed words, or instead as single-word switches to Latin in an Old English document, since it is not uncommon for words only ever to occur with their Latin case endings.

The earlier borrowings include many more words that are of reasonably common occurrence in Old English and later, for instance names of some common plants and foodstuffs, as well as some very basic words to do with the religious life.

では,具体的に前期・後期のラテン借用語とはどのような単語なのか.それについては今後の記事で紹介していく予定である.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-09-07 Sat

■ #3785. ローマン・ブリテンの言語状況 (2) [roman_britain][latin][celtic][history][gaulish][contact][language_shift][prestige][sociolinguistics]

昨日の記事に続き,ローマン・ブリテンの言語状況について.Durkin (58) は,ローマ時代のガリアの言語状況と比較しながら,この問題を考察している.

One tantalizing comparison is with Roman Gaul. It is generally thought that under the Empire the linguistic situation was broadly similar in Gaul, with Latin the language of an urbanized elite and Gaulish remaining the language in general use in the population at large. Like Britain, Gaul was subject to Germanic invasions, and northern Gaul eventually took on a new name from its Frankish conquerors. However, France emerged as a Romance-speaking country, with a language that is Latin-derived in grammar and overwhelmingly also in lexis. One possible explanation for the very different outcomes in the two former provinces is that urban life may have remained in much better shape in Gaul than in Britain; Gaul had been Roman for longer than Britain, and urban life was probably much more developed and on a larger scale, and may have proved more resilient when facing economic and political vicissitudes. In Gaul the Franks probably took over at least some functioning urban centres where an existing Latin-speaking elite formed the basis for the future administration of the territory; this, combined with the importance and prestige of Latin as the language of the western Church, probably led ultimately to the emergence of a Romance-speaking nation. In Britain the existing population, whether speaking Latin or Celtic, probably held very little prestige in the eyes of the Anglo-Saxon incomers, and this may have been a key factor in determining that England became a Germanic-speaking territory: the Anglo-Saxons may simply not have had enough incentive to adopt the language(s) of these people.

つまり,ローマ帝国の影響が長続きしなかったブリテン島においては,ラテン語の存在感はさほど著しくなく,先住のケルト人も,後に渡来してきたゲルマン人も,大きな言語的影響を被ることはなかったし,ましてやラテン語へ言語交代 (language_shift) することもなかった.しかし,ガリアにおいては,ローマ帝国の影響が長続きし,ラテン語(そしてロマンス語)との言語接触も持続したために,最終的に基層のケルト語も後発のフランク語も,ラテン語に呑み込まれるようにして消滅していくことになった,というわけだ.

ブリテン島とガリアは,ケルト系言語の基層の上にラテン語がかぶさってきたという点では共通の歴史を有しているようにみえるが,ラテン語との接触の期間や密度という点では差があり,それが各々の地域における後世の言語事情にも重要なインパクトを与えたということだろう.この差は,部分的にはローマからの距離の差やラテン語に対して抱いていた威信の差へも還元できるものかもしれない.

この両地域の社会言語学的な状況の差は,回り回って英語とフランス語におけるケルト借用語の質・量の差にも影響を与えている.これについては,Durkin による「#3753. 英仏語におけるケルト借用語の比較・対照」 ([2019-08-06-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow