2018-05-05 Sat

■ #3295. study の <u> が短母音のわけ [spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][vowel][loan_word][french]

昨日の記事「#3294. occupy は「オカピー」と発音しない」 ([2018-05-04-1]) で,study の綴字と発音の関係について少し触れた.<u> の綴字は,後ろに子音文字 <d> が1つと母音字 <y> が続くので,規則に照らせば /juː/ に対応するはずである.実際,同根の student や studious では /juː/ が現われる.しかし,study では,むしろ短母音 /ʌ/ が現われる.字をもつ *studdy の綴字であれば,そのように発音されるだろうとは理解できるのだが,なぜ study で /ˈstʌdi/ となるのだろうか.

Upward and Davidson (161--62) によれば次の通りである.通常,ラテン語やフランス語に由来する語における短母音字としての <u> はほとんど /ʌ/ に対応する.その場合,2つ以上の子音字,あるいは <x> が続くのが典型である.例えば,ultimate, usher, abundance, discuss, button, public, muscle, luxury, product, adult, result, judge; subject, success, suggest, supplement の如くだ(単音節語では,drug, sum などの例はある).

しかし,まれに問題の <u> の後に1つの子音字のみ(さらにその後ろに母音字)が続くものもある.そのような例外の1つが study だというわけだ.ほかに,bunion, pumice, punish もあり,これらでは綴字上予測されそうな /juː/ が現われないので注意を要する. 最後に挙げた punish と関連して,vanish, finish, abolish などのフランス語由来の -ish 動詞(cf. 現代フランス語の -ir 動詞)でも,直前の音節の母音字は短い母音で読むことになっている.フランス語 -ir 動詞の英語への受容のされ方については,「#346. フランス語 -ir 動詞」 ([2010-04-08-1]) を参照.

母音(字)の長短についての一般論は「#2075. 母音字と母音の長短」 ([2015-01-01-1]) をどうぞ.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2018-04-28 Sat

■ #3288. restaurant の発音の英語化 [french][loan_word][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap]

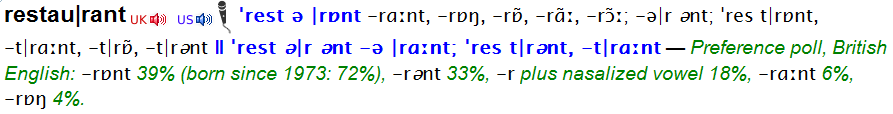

学生から restaurant の <au> 部分が発音されず,2音節となるのはなぜかという質問を受けた.しかし,以下に示すように,この単語には多種多様な発音があり,<au> の部分が曖昧母音 /ə/ として実現される3音節の発音も普通にある.つまり,/ˈrɛstrɒnt/ も /ˈrɛstərɒnt/ もある.

この中間音節の母音は,オリジナルのフランス語では /ɔ/ と明瞭な母音で発音されるが,英語では19世紀初めにこの語が借用された当初から,弱化された /ə/ で発音されていたと思われる.語頭音節と語末音節にそれぞれ第1,第2強勢が置かれるのならば,中間音節は弱音節となり,その母音は弱母音となるはずだからだ.さらに当該音節の弱化が進めば,消失ということになる.

しかし,この語の発音の揺れが激しいのは,実はこの中間音節というよりも,語末音節においてなのである.LPD の発音表記を見てみよう.

母音の質・量の変異もさることながら,鼻音化しているか否か,有声軟口蓋鼻音 /ŋ/ が付随するか否か,/t/ が実現されているか否か等をめぐって,相当な変異が認められる.表記中のコメントにあるように,イギリス英語の1973年生まれ以降では /-rɒnt/ が大多数となってきているようであり,近年のトレンドと解釈することができる.

歴史的にみれば,この語が借用された当初はオリジナルのフランス語発音を真似て /t/ なしの鼻母音で発音されていたが,時とともに英語化した発音へと推移してきたといえる.まず非英語的な鼻母音が,英語的な有声軟口蓋鼻音 /ŋ/ に置き換えられ,次に綴字発音 (spelling_pronunciation) として /t/ をもつ発音も現われてきたのだろう.しかし,前の発音が後の発音に置き換えられたというのは正確ではなく,前の発音も勢力を弱めながら存続し,後の発音が次々とその上に積み重なってきたと理解すべきである.結果として,累積してきた種々の発音が,現在,並立しているというわけだ.

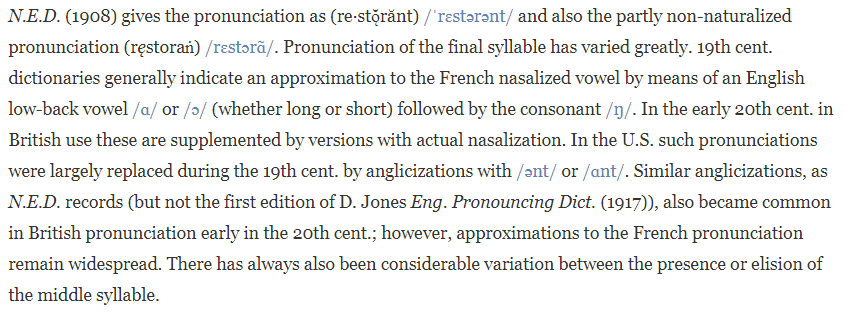

まとめれば,中間音節にせよ語末音節にせよ,いずれもフランス語の原音から次々と英語化する形で変異を増やしてきたということができる.この歴史的な変遷については OED が詳しいので,以下に引用しておこう.

2018-04-25 Wed

■ #3285. chivalry の語頭子音 [pronunciation][french][loan_word][consonant][digraph]

「騎士道」を意味する chivalry は /ˈʃɪvəlri/ のように語頭に無声歯茎硬口蓋摩擦音 /ʃ/ をもって発音される.しかし,これは一見すると理解しがたい発音である.というのは,この単語はフランス語からの借用語であり,1300年頃の Kyng Alysaunder に "He schipeth into Libie, With al his faire chivalrie." (l. 1495) のように現われることから考えて,当時のフランス語の原音に忠実な破擦音 /ʧ/ をもって発音されていたはずだからだ.

確かに現代英語の <ch> は最も典型的には破擦音 /ʧ/ に対応するといいつつも,摩擦音 /ʃ/ への対応も決して珍しくない.しかし,「#2201. 誕生おめでとう! Princess Charlotte」 ([2015-05-07-1]) の記事で触れたように,フランス借用語に関する限り,<ch> がいずれの子音を表わすかは,およそ借用の時期によって決まる.先の記事で,次のように述べた通りである.

現代英語におけるフランス借用語で <ch> と綴られるものが,破擦音 [ʧ] を示すか摩擦音 [ʃ] を示すかという基準は,しばしば借用時期を見極めるのに用いられる.例えば chance, charge, chief, check, chair, charm, chase, cheer, chant はいずれも中英語期に借用されたものであり,champagne, chef, chic, chute, chaise, chicanery, charade, chasseur, chassis はいずれも近代英語期に入ったものである.

つまり,問題は何かといえば,現代英語の chivalry は中英語期に借用された語であるから,当時から現在まで破擦音 /ʧ/ を持ち続けたはずであると予想されるにもかからず,むしろ近代英語期の借用語であるかのような摩擦音 /ʃ/ を示すのが妙だということだ.OED でも,現代で /ʧɪvəlri/ の発音もあり得ると示唆しながらも,"As a Middle English word the proper historical pronunciation is with /ʧ-/; but the more frequent pronunciation at present is with /ʃ-/, as if the word had been received from modern French." と述べられている.

『英語語源辞典』によると次のような事情があったようだ.

この語派1600年以前に一度すたれたが,やがて18C後半のロマンス作家たちがよみがえらせた.〔中略〕ME では OF 同様 /ʧ-/ と発音されたが,今では ModF の影響による /ʃ-/ がふつう(ちなみに OF では ch- は13Cの間に /ʧ/ から /ʃ/ に変化している).

ここで「一度すたれた」とあるが,OED の用例を見渡す限り,完全に途絶えたというわけではなさそうだ.だが,中世の騎士道への懐古的な関心をもちながら近代の語として蘇らせた,あるいは再借用されたという筋書きを想定すれば,現在ふつうである破擦音の謎が解ける.そうだとすれば,chivalry という語は,/ʃ/ を示すがゆえに,近現代的な中世観を体現する語として,現代人にとってロマンチックなほどに中世的な語と言えるのかもしれない.

2重字 <ch> については,「#3251. <chi> は「チ」か「シ」か「キ」か「ヒ」か?」 ([2018-03-22-1]), 「#1893. ヘボン式ローマ字の <sh>, <ch>, <j> はどのくらい英語風か」 ([2014-07-03-1]) の記事も参照.関連して「#2049. <sh> とその異綴字の歴史」 ([2014-12-06-1]) もどうぞ.

2018-04-03 Tue

■ #3263. なぜ古ノルド語からの借用語の多くが中英語期に初出するのか? [sobokunagimon][old_norse][standardisation][loan_word][borrowing][medium][oe][eme]

「#2869. 古ノルド語からの借用は古英語期であっても,その文証は中英語期」 ([2017-03-05-1]) でも取り上げた話題だが,改めてこの問題について考えてみたい.

現代英語の語彙には古ノルド語からの借用語が多数含まれている.その歴史的背景としては,9世紀後半以降に古ノルド語を母語とするヴァイキングがイングランド北部・東部に定住し,そこで英語話者と混じり合ったという経緯がある.しかし,そこで借用されたはずの多くの古ノルド語からの単語が文献上に初めて現われるのは,ヴァイキングの定住が進んだ古英語後期においてではなく,少なからぬ時間を空けた初期中英語期以降,とりわけ13世紀以降のことなのである.歴史的状況から予想される借用年代と実際に文証される年代との間にギャップがあるというこの問題は,英語史でもしばしば取り上げられるが,その理由は一般的に次のように考えられている(Blake, p. 92 より).

It is a feature of the history of the English language that there are a considerable number of Old Norse loans in the language, but the appearance of these loans in writing occurs mainly from the thirteenth century onwards and not from the pre-Conquest period which is when the Viking invasions and settlements occurred. The usual explanation for this is as follows. Most Old English literature which has survived is written in the West Saxon dialect, and the dialect represents those areas of England which were least affected by the Scandinavian invasions and settlements. Hence Scandinavian influence in these areas cannot have been very significant. Even in those areas where the Danes had settled, they continued to live in their own communities and would only gradually have become absorbed among the Anglo-Saxon population. This implies that the new settlers were for a long time regarded as foreigners and no attempt was made to assimilate them. Consequently the introduction of Old Norse words into English was delayed in the Anglian dialects, and their southward drift would be even later than that. It is hardly surprising in this view that words of Scandinavian origin are not found in English in any numbers until the thirteenth century.

つまり,ヴァイキングは確かにイングランド北部・東部にしたが,必ずしもすぐには先住のアングロサクソン人と混じり合ったわけではなく,語彙借用を含めた言語的な融合は案外遅かったというわけだ.また,後期古英語の文献として残っているものの多くはイングランド南西部 West Saxon の方言で書かれているため,ヴァイキングの言語的影響は古英語期中には文証されにくいのだという.

しかし,Blake (93--94) はこの一般的な見解が本当に正しいかどうかは非常に怪しいとみている.

The continuity of West Saxon as Standard Old English would have discouraged the adoption of new words from other varieties and even from other languages. The tenth-century reforms were a continuation of the policies introduced by Alfred, and it is not surprising that the attitude towards standardisation and conservatism should have become more rigid as the standard grew in importance.

Blake の考え方はこうだ.話し言葉のレベルでは,歴史的経緯から自然に予想されるとおり,古ノルド語からの借用語の多くがすでに後期古英語期に入っていた.しかし,標準的で保守的な West Saxon 方言の書き言葉においては,口語的で略式的な響きをもつ当時の新語ともいうべき古ノルド語借用語を使用することはふさわしくないと考えられ,排除されたのではないか.つまり,人々の口からは発せられていたが,文章には反映されなかったということではないか.

書き言葉の保守性はよく知られた事実だが,さらに標準的な書き言葉ともなればますます保守的になるということは,確かに考えられる.

・ Blake, N. F. A History of the English Language. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1996.

2018-04-02 Mon

■ #3262. 後期中英語の標準化における "intensive elaboration" [lme][standardisation][latin][french][register][terminology][lexicology][loan_word][lexical_stratification]

「#2742. Haugen の言語標準化の4段階」 ([2016-10-29-1]) や「#2745. Haugen の言語標準化の4段階 (2)」 ([2016-11-01-1]) で紹介した Haugen の言語標準化 (standardisation) のモデルでは,形式 (form) と機能 (function) の対置において標準化がとらえられている.それによると,標準化とは "maximal variation in function" かつ "minimal variation in form" に特徴づけられる現象である.前者は codification (of form),後者は elaboration (of function) に対応すると考えられる.

しかし,"elaboration" という用語は注意が必要である.Haugen が標準化の議論で意図しているのは,様々な使用域 (register) で広く用いることができるという意味での "elaboration of function" のことだが,一方 "elaboration of form" という別の過程も,後期中英語における標準化と深く関連するからだ.混乱を避けるために,Haugen が使った意味での "elaboration of function" を "extensive elaboration" と呼び,"elaboration of form" のほうを "intensive elaboration" と呼んでもいいだろう (Schaefer 209) .

では,"intensive elaboration" あるいは "elaboration of form" とは何を指すのか.Schaefer (209) によれば,この過程においては "the range of the native linguistic inventory is increased by new forms adding further 'variability and expressiveness'" だという.中英語の後半までは,書き言葉の標準語といえば,英語の何らかの方言ではなく,むしろラテン語やフランス語という外国語だった.後期にかけて英語が復権してくると,英語がそれらの外国語に代わって標準語の地位に就くことになったが,その際に先輩標準語たるラテン語やフランス語から大量の語彙を受け継いだ.英語は本来語彙も多く保ったままに,そこに上乗せして,フランス語の語彙とラテン語の語彙を取り入れ,全体として序列をなす三層構造の語彙を獲得するに至った(この事情については,「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]) や「#2977. 連載第6回「なぜ英語語彙に3層構造があるのか? --- ルネサンス期のラテン語かぶれとインク壺語論争」」 ([2017-06-21-1]) の記事を参照).借用語彙が大量に入り込み,書き言葉上,英語の語彙が序列化され再編成されたとなれば,これは言語標準化を特徴づける "minimal variation in form" というよりは,むしろ "maximal variation in form" へ向かっているような印象すら与える.この種の variation あるいは variability の増加を指して,"intensive elaboration" あるいは "elaboration of form" と呼ぶのである.

つまり,言語標準化には形式上の変異が小さくなる側面もあれば,異なる次元で,形式上の変異が大きくなる側面もありうるということである.この一見矛盾するような標準化のあり方を,Schaefer (220) は次のようにまとめている.

While such standardizing developments reduced variation, the extensive elaboration to achieve a "maximal variation in function" demanded increased variation, or rather variability. This type of standardization, and hence norm-compliance, aimed at the discourse-traditional norms already available in the literary languages French and Latin. Late Middle English was thus re-established in writing with the help of both Latin and French norms rather than merely substituting for these literary languages.

・ Schaefer Ursula. "Standardization." Chapter 11 of The History of English. Vol. 3. Ed. Laurel J. Brinton and Alexander Bergs. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2017. 205--23.

2018-03-30 Fri

■ #3259. 17世紀に作られた動詞派生名詞群の呈する問題 (2) [synonym][loan_word][borrowing][renaissance][inkhorn_term][emode][lexicology][word_formation][suffix][affixation][neologism][derivation][statistics]

昨日の記事 ([2018-03-29-1]) の続編.昨日示した Bauer からの動詞派生名詞のリストでは,-ment や -ure の接尾辞の存在が目立っていた.17世紀の名詞を作る接尾辞にどのような種類のものがあり,それぞれがいくつの名詞を作っていたのだろうか.これについても,Bauer (185) が OED に基づいて統計をとっている.結果は以下の通り.

| Suffix | Number |

| -y | 2 |

| -ery | 8 |

| -ancy | 10 |

| -ency | 10 |

| -ence | 18 |

| -ion | 20 |

| -ance | 49 |

| -al | 56 |

| -ure | 96 |

| -ation | 190 |

| -ment | 258 |

トップ数種類の接尾辞が大半をカバーしていることから,頻度の高い「典型的な」接尾辞があることは確かにわかる.しかし,典型的な接尾辞が少数あるということで,問題が解決することにはならない.これらの典型的な接尾辞を含めた複数種類の接尾辞が,同一の基体に接続し得たということ,そして実際にそのように造語され併用されたという状況こそが,問題だったである.

昨日の記事で触れたように,Bauer はこの問題を新語のニーズに関わる複雑さに帰しているが,それと関連して,生産的な派生に対して非生産的な派生への需要も常に存在するものだという主張を展開している.

. . . there is a constant application of unproductive morphology in order to solve problems provided by productive morphology, so that the language is continually having new words added to it which are not the forms which would be the predicted ones, as well as a number of predicted forms. That is, the processes of history add irregularities (which are available to turn into regularities if enough of them are coined). History, rather than simplifying matters (or rather than merely simplifying matters), reflects a process of building in extra complications.

言語使用者の新語への要求は,必ずしも生産的な派生が与えてくれる手段とその結果だけでは満たされないほどに複雑で精妙なのだろう.そこで,あえて非生産的な派生の手段を用いて,不規則な派生語を作り出すこともあるのかもしれない.現代の歴史言語学者は,過去に生きた言語使用者の,そのような複雑で精妙な造語心理にどこまで迫れるのだろうか.困難ではあるがエキサイティングなテーマである.

・ Bauer, Laurie. "Competition in English Word Formation." Chapter 8 of The Handbook of the History of English. Ed. Ans van Kemenade and Bettelou Los. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006. 177--98.

2018-03-29 Thu

■ #3258. 17世紀に作られた動詞派生名詞群の呈する問題 (1) [synonym][lexical_blocking][loan_word][borrowing][renaissance][inkhorn_term][emode][lexicology][word_formation][suffix][affixation][neologism][derivation][cognate]

英国ルネサンス期の17世紀には,ラテン語やギリシア語を中心とする諸言語から大量の語彙が借用された.この経緯については,これまで「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]),「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1]),「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1]) などの記事で様々な角度から取り上げてきた.この時代には,しばしば「同じ語」が異なった接尾辞を伴って誕生するという現象が見られた.例えば,すでに1586年に discovery が英語語彙に加えられていたところに,17世紀になって同義の discoverance や discoverment も現われ,短期間とはいえ競合・共存したのである(関連して,「#3157. 華麗なる splendid の同根類義語」 ([2017-12-18-1]) も参照).

以下は,Bauer (186) が OED から収集した,17世紀に初出する動詞派生名詞の組である.

| abutment | abuttal | |

| bequeathal | bequeathment | |

| bewitchery | bewitchment | |

| commitment | committal | committance |

| composal | compositure | |

| comprisal | comprisement | comprisure |

| concumbence | concumbency | |

| condolement | condolence | |

| conducence | conducency | |

| contrival | contrivance | |

| depositation | depositure | |

| deprival | deprivement | |

| desistance | desistency | |

| discoverance | discoverment | |

| disfiguration | disfigurement | |

| disproval | disprovement | |

| disquietal | disquietment | |

| dissentation | dissentment | |

| disseveration | disseverment | |

| encompassment | encompassure | |

| engraftment | engrafture | |

| exhaustment | exhausture | |

| exposal | exposement | exposure |

| expugnance | expugnancy | |

| expulsation | expulsure | |

| extendment | extendure | |

| impartment | imparture | |

| imposal | imposement | imposure |

| insistence | insisture | |

| interposal | interposure | |

| pretendence | pretendment | |

| promotement | promoval | |

| proposal | proposure | |

| redamancy | redamation | |

| renewal | renewance | |

| reposance | reposure | |

| reserval | reservancy | |

| resistal | resistment | |

| retrieval | retrievement | |

| returnal | returnment | |

| securance | securement | |

| subdual | subduement | |

| supportment | supporture | |

| surchargement | surchargure |

これらの語のなかには,現在でも標準的なものもあれば,すでに廃語となっているものもある.短期間しか用いられなかったものもあれば,広く受け入れられたものもある.17世紀より前か後に作られた同義の派生名詞と競合したものもあれば,そうでないものもある.この時代の後,現代に至るまでに,これらの2重語や3重語の並存状況が整理されていったケースもあれば,そうでないケースもある.整理のされ方が lexical_blocking の原理により説明できるものもあれば,そうでないものもある.つまり,これらの組について一般化して言えることはあまりないのである.

17世紀に限らないとはいえ,とりわけこの世紀に,互いに意味を違えない派生名詞が複数作られ,競合・共存したという事実は何を物語るのだろうか.ラテン語やギリシア語から湯水のように語を借用した結果ともいえるし,それらから抽出した名詞派生接尾辞を利用して無方針に様々な派生名詞を造語していった結果ともいえる.しかし,Bauer (197) は社会言語学的な観点から,次のように示唆している.

Individual ad hoc decisions on relevant forms may or may not be picked up widely in the community. . . . [I]t is clear from the history which the OED presents that the need of the individual for a particular word is not always matched by the need of the community for the same word, with the result that multiple coinages are possible.

いずれにせよ,この歴史的事情が,現代英語の動詞派生名詞の形態に少なからぬ不統一と混乱をもたらし続けていることは事実である.今後,整理されてゆくとしても,おそらくそれには数世紀という長い時間がかかることだろう.

・ Bauer, Laurie. "Competition in English Word Formation." Chapter 8 of The Handbook of the History of English. Ed. Ans van Kemenade and Bettelou Los. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006. 177--98.

2018-01-10 Wed

■ #3180. 徐々に高頻度語の仲間入りを果たしてきたフランス・ラテン借用語 [french][latin][loan_word][borrowing][frequency][statistics][lexicology][hc][bnc]

英語史では,中英語から初期近代英語にかけて,フランス語とラテン語から大量の語彙借用がなされた.それらのうち現在常用されるものについては,おそらく借用時点からスタートして時間とともに使用頻度が増してきたものと想像される.というのは,借用された当初から高頻度で用いられたとは考えにくく,徐々に英語に同化し,日常化してきたととらえるのが自然だからだ.

この仮説を実証するのにいくつかの方法がありそうだが,Durkin があるやり方で調査を行なっている.中英語,初期近代英語,現代英語のそれぞれにおいてコーパスに基づく最高頻度語リストを作り,そのなかにフランス・ラテン借用語がどのくらいの割合で含まれているかを調べ,その割合の通時的推移を比較するという手法だ.古い時代のコーパスでは綴字の変異という問題が関わるため,厳密に調査しようとすれば単純にはいかないが,Durkin はとりあえずの便法として,中英語と初期近代英語については Helsinki Corpus の 1150--1500年と1500--1710年のセクションを用いて,現代英語については BNC を用いて異綴字ベースで調査した.それぞれ頻度ランキングにして900--1000位ほどまでの単語(綴字)リストを作り,そのなかでフランス・ラテン語借用語が占める割合をはじき出した.

結果は,中英語セクションでは7%ほどだったものが,初期近代英語セクションでは19%まで上昇し,さらに現代英語セクションでは38%までに至っている.粗い調査であることは認めつつも,フランス・ラテン借用語で現在頻用されているものの多くについては,歴史のなかで徐々に頻度を上げてきた結果として,現在の日常的な性格を示すことがよくわかった.

さらにおもしろいことに,初期近代英語のセクション(1500--1710年)に関する数値について,高頻度語リストに含まれるフランス・ラテン借用語のすべてが1500年より前に借用されたものであり,しかもその2/3ほどは確実にフランス借用語であるという事実が確認される (Durkin 338--39) .

また,中英語と初期近代英語の高頻度語リストに含まれるフランス・ラテン借用語の多くが,現代英語の高頻度語リストにも再現されている事実にも触れておこう.古い2期には現われるが現代期からは漏れている語群を眺めると,なんとも時代の変化を感じさせてくれる.例えば,honour, justice, manner, noble, parliament, pray, prince, realm, religion, supper, treason, usury, virtue である (Durkin 340) .

時代によって最頻語リストやキーワードが異なることは当然といえば当然だが,歴史英語コーパスを用いて様々な時代を比較してみるとおもしろそうだ.例えば,初期近代英語コーパスに基づくキーワード・リストについて「#2332. EEBO のキーワードを抽出」 ([2015-09-15-1]) を参照.また,頻度と歴史の問題については「#1243. 語の頻度を考慮する通時的研究のために」 ([2012-09-21-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2018-01-09 Tue

■ #3179. 「新古典主義的複合語」か「英製羅語」か [neo-latin][latin][greek][word_formation][lexicology][loan_word][compounding][derivation][lmode][scientific_english][scientific_name][neologism][waseieigo][terminology][register]

新古典主義的複合語 (neoclassical compounds) とは,aerobiosis, biomorphism, cryogen, nematocide, ophthalmopathy, plasmocyte, proctoscope, rheophyte, technocracy のような語(しばしば科学用語)を指す.Durkin (346--37) によれば,この類いの語彙は早くは1600年前後から確認され,例えば polycracy (1581), pantometer (1597), multinomial (1608) がみられる.しかし,爆発的に量産されるようになったのは,科学が急速に発展した後期近代英語期,とりわけ19世紀になってからのことである(「#616. 近代英語期の科学語彙の爆発」 ([2011-01-03-1]),「#3013. 19世紀に非難された新古典主義的複合語」 ([2017-07-27-1]),「#3014. 英語史におけるギリシア語の真の存在感は19世紀から」 ([2017-07-28-1]),「#3166. 英製希羅語としての科学用語」 ([2017-12-27-1]) を参照).

新古典主義的複合語について強調しておくべきは,それが借用語ではなく,あくまで英語(を始めとするヨーロッパの諸言語)において形成された語であるという点だ.確かにラテン語やギリシア語などの古典語をモデルとしてはいるが,決してそこから借用されたわけではない.その意味では英単語ぽい体裁をしていながらも英単語ではない「和製英語」と比較することができる.新古典主義的複合語の舞台は英語であるから,つまり「英製羅語」といってよい.しかし,英製羅語と和製英語とのきわだった相違点は,前者が主として国際的で科学的な文脈で用いられるが,後者はそうではないという事実にある.すなわち,両者のあいだには使用域において著しい偏向がみられる.Durkin は,新古典主義的複合語について次のように述べている.

. . . these formations typically belong to the international language of science and move freely, often with little or no morphological adaptation, between English, French, German, and other languages of scientific discourse. They are often treated in very different ways in different traditions of lexicography and lexicology; however, those terms that are coined in modern vernacular languages are certainly not loanwords from Latin or Greek, even though they may be formed from elements that originated in such loanwords. (347)

. . . Latin words and word elements have become ubiquitous in modern technical discourse, but frequently in new compound or derivative formations or with new meanings that have seldom if ever been employed in contextual use in actual Latin sentences. (349)

これらの造語を指して「新古典主義的複合語」と呼ぶか「英製羅語」と呼ぶかは,たいした問題ではない.しかし,和製英語の場合には「英語主義的複合語」と呼ばないのはなぜだろうか.この違いは何に起因するのだろうか.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2017-12-31 Sun

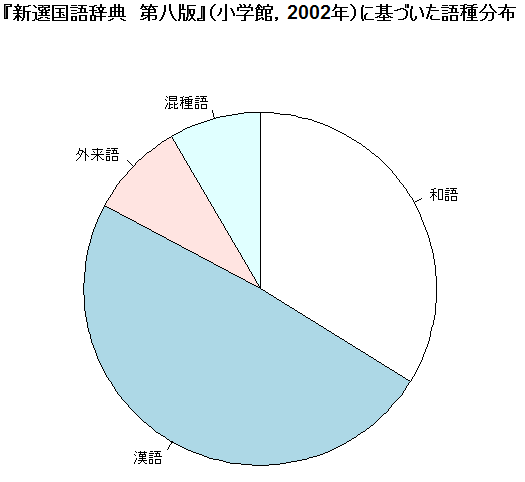

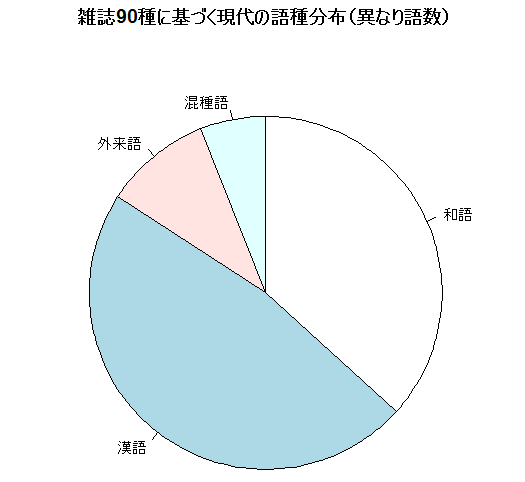

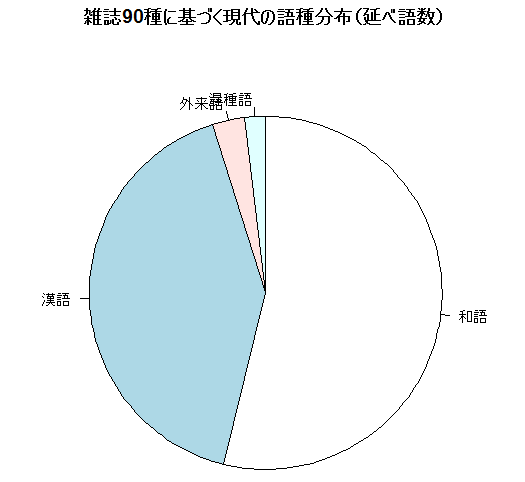

■ #3170. 現代日本語の語種分布 (2) [japanese][lexicology][statistics][etymology][loan_word][lexical_stratification]

「#1645. 現代日本語の語種分布」 ([2013-10-28-1]) の記事で,標題について明治から昭和にかけて出版された国語辞典に基づく数値を示した.今回は平成からの数値を示そう.沖森ほか (71) に掲載されている,『新選国語辞典 第八版』(小学館,2002年)に基づいた語種分布である.

|

|

先の記事 ([2013-10-28-1]) で参照した,国立国語研究所『語彙の研究と教育(上)』(大蔵省印刷局,1984年)の雑誌90種に基づく異なり語数と延べ語数の統計も,改めて円グラフにして示そう(こちらも沖森ほか (79) 経由で).

|

|

|

|

・ 沖森 卓也,木村 義之,陳 力衛,山本 真吾 『図解日本語』 三省堂,2006年.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2017-12-26 Tue

■ #3165. 英製羅語としての conspicuous と external [waseieigo][latin][borrowing][loan_word][derivation][etymology][suffix][adjective][emode][neologism][lexicology][word_formation][shakespeare]

標題と関連する話題は,「#1493. 和製英語ならぬ英製羅語」 ([2013-05-29-1]),「#1927. 英製仏語」 ([2014-08-06-1]),「#2979. Chibanian はラテン語?」 ([2017-06-23-1]) や,waseieigo の各記事で取り上げてきた.

Baugh and Cable (222) で,初期近代期に英語がラテン単語を取り込む際に施した適応 (adaptation) が論じられているが,次のような1文があった.

. . . the Latin ending -us in adjectives was changed to -ous (conspicu-us > conspicuous) or was replaced by -al as in external (L. externus).

これらの英単語は,ある意味では借用された語ともいえるが,ある意味では英語が自ら形成した語ともいえる.「英製羅語」と呼ぶのがふさわしい例ではないだろうか.

OED によれば,conspicuous は,ラテン語 conspicuus に基づき,英語側でやはりラテン語由来の形容詞を作る接尾辞 -ous を付すことによって新たに形成した語である.16世紀半ばに初出している.

1545 T. Raynald tr. E. Roesslin Byrth of Mankynde Hh vij These vaynes doo appeare more conspicuous and notable to the eyes.

実はこの接尾辞を基体(主としてラテン語由来だが,その他の言語の場合もある)に付加して自由に新たな形容詞を作るパターンはロマンス諸語に広く見られたもので,フランス語で -eus を付したものが,14--15世紀を中心として英語にも -ous の形で大量に入ってきた.つまり,まずもって仏製羅語というべきものが作られ,それが英語にも流れ込んできたというわけだ.例として,dangerous, orgulous, adventurous, courageous, grievous, hideous, joyous, riotous, melodious, pompous, rageous, advantageous, gelatinous などが挙げられる(OED の -ous, suffix より).

また,英語でもフランス語に習う形でこのパターンを積極的に利用し,自前で conspicuous のような英製羅語を作るようになってきた.同種の例として,guilous, noyous, beauteous, slumberous, timeous, tyrannous, blusterous, burdenous, murderous, poisonous, thunderous, adiaphorous, leguminous, delirious, felicitous, complicitous, glamorous, pulchritudinous, serendipitous などがある(OED の -ous, suffix より).

標題のもう1つの単語 external も conspicuous とよく似たパターンを示す.この単語は,ラテン語 externus に基づき,英語側でラテン語由来の形容詞を作る接尾辞 -al を付すことによって形成した英製羅語である.初出は Shakespeare.

a1616 Shakespeare Henry VI, Pt. 1 (1623) v. vii. 3 Her vertues graced with externall gifts.

a1616 Shakespeare Antony & Cleopatra (1623) v. ii. 340 If they had swallow'd poyson, 'twould appeare By externall swelling.

反意語の internal も同様の事情かと思いきや,こちらは一応のところ post-classical Latin として internalis が確認されるという.しかし,この語のラテン語としての使用も "14th cent. in a British source" ということなので,やはり英製の匂いはぷんぷんする.英語での初例は,15世紀の Polychronicon.

?a1475 (?a1425) tr. R. Higden Polychron. (Harl. 2261) (1865) I. 53 The begynnenge of the grete see is..at the pyllers of Hercules..; after that hit is diffusede in to sees internalle [a1387 J. Trevisa tr. þe ynnere sees; L. maria interna].

「○製△語」は決して珍しくない.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2017-12-18 Mon

■ #3157. 華麗なる splendid の同根類義語 [cognate][synonym][lexicology][inkhorn_term][emode][borrowing][loan_word][renaissance][thesaurus][htoed]

「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1]) の記事で,ルネサンス期のラテン語かぶれの華美を代表する単語の1つとして splendidious を挙げた.この語は現在では廃用となっているが,その意味は現代でも普通に用いられる splendid と同じ「華麗な,豪華な」である.前者はルネサンス華やかなりし15世紀から用いられており,後者も単語としては17世紀前半には初出している(ただし,語義によって初出年代が異なる).この15--17世紀には,語根も意味も同じくする splendid 系の単語がいくつも現われては消えていったのである.HTOED より splendid の項を覗いてみると,次のようにある.

02.04.05.03 (adj.) Splendid

þurhbeorht OE ・ geatolic OE ・ torht OE ・ torhtlic OE ・ wrætlic OE ・ orgulous/orgillous a1400 ・ splendidious 1432/50--1653 ・ splendiferous c1460--1546 ・ splendent 1509-- ・ splendant 1590-- ・ splendorous 1591-- ・ splendidous 1605--1640 ・ transplendent 1622; 1854 ・ florid 1642--1725 ・ splendious 1654 ・ splendid 1815-- ・ splendescent 1848-- ・ nifty 1868-- ・ ducky 1897-- (colloq.) ・ many-splendoured a1907--

歴史的に splendidious, splendiferous, splendent, splendant, splendorous, splendidous, splendious, splendid, splendescent, splendoured の10語が,互いに比較的近接した時期に現われ,大概は後に消えている(ただし,手持ちの英和辞書では,splendiferous, splendent, splendorous は見出しが立てられていた).

基体(ラテン語あるいはフランス語由来)も意味も同じくする類義語 (synonym) がこのように複数あったところで,害こそあれ利はない.それで多くの語が競合し,自滅していったのだろう.

Kay and Allan (15) も,この語群に言及しつつ次のように述べている.

Sometimes there was a degree of experimentation over the form of a new word. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the OED records the following forms meaning 'splendid': splendant, splendicant, splendidious, splendidous, splendiferous, splendious and splendorous. Splendid itself is first recorded in 1624. Unsurprisingly, most of these forms were short-lived; no language needs quite so many similar words for the same concept.

対応する名詞についても HTOED より抜き出すと,"splendency a1591--1607 ・ splendancy 1591 ・ splendence 1604 ・ splendour 1774-- ・ splendiferousness 1934--" とやはり豊富である.

・ Kay, Christian and Kathryn Allan. English Historical Semantics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015.

2017-12-15 Fri

■ #3154. 英語史上,色彩語が増加してきた理由 [bct][borrowing][lexicology][french][loan_word][sociolinguistics]

「#2103. Basic Color Terms」 ([2015-01-29-1]) および昨日の記事「#3153. 英語史における基本色彩語の発展」 ([2017-12-14-1]) で,基本色彩語 (Basic Colour Terms) の普遍的発展経路の話題に触れた.英語史においても,BCTs の種類は,普遍的発展経路から予想される通りの順序で,古英語から中英語へ,そして中英語から近代英語へと着実に増加してきた.そして,BCTs のみならず non-BCTs も時代とともにその種類を増してきた.これらの色彩語の増加は何がきっかけだったのだろうか.

Biggam (123--24) によれば,古英語から中英語にかけての増加は,ノルマン征服後のフランス借用語に帰せられるという.BCTs に関していえば,中英語で加えられたbleu は確かにフランス語由来だし,brun は古英語期から使われていたものの Anglo-French の brun により使用が強化されたという事情もあったろう.また,色合,濃淡 ,彩度,明度を混合させた古英語の BCCs 基準と異なり,中英語期にとりわけ色合を重視する BCCs 基準が現われてきたのは,ある産業技術上の進歩に起因するのではないかという指摘もある.

The dominance of hue in certain ME terms, especially in BCTs, was at least encouraged by certain cultural innovations of the later Middle Ages such as banners, livery, and the display of heraldry on coats-of-arms, all of which encouraged the development and use of strong dyes and paints. (125)

近代英語期になると,PURPLE, ORANGE, PINK が BCCs に加わり,近現代的な11種類が出そろうことになったが,この時期にはそれ以外にもおびただしい non-BCTs が出現することになった.これも,近代期の社会や文化の変化と連動しているという.

From EModE onwards, the colour vocabulary of English increased enormously, as a glance at the HTOED colour categories reveals. Travellers to the New World discovered dyes such as logwood and some types of cochineal, while Renaissance artists experimented with pigments to introduce new effects to their paintings. Much later, synthetic dyes were introduced, beginning with so-called 'mauveine', a purple shade, in 1856. In the same century, the development of industrial processes capable of producing identical items which could only be distinguished by their colours encouraged the proliferation of colour terms to identify and market such products. The twentieth century saw the rise of the mass fashion industry with its regular announcements of 'this year's colours'. In periods like the 1960s, colour, especially vivid hues, seemed to dominate the cultural scene. All of these factors motivated the coining of new colour terms. The burgeoning of the interior décor industry, which has a never-ending supply of subtle mixes of hues and tones, also brought colour to the forefront of modern minds, resulting in a torrent of new colour words and phrases. It has been estimated that Modern British English has at least 8,000 colour terms . . . . (126)

英語の色彩語の歴史を通じて,ちょっとした英語外面史が描けそうである.

・ Kay, Christian and Kathryn Allan. English Historical Semantics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015.

・ Biggam, C. P. "English Colour Terms: A Case Study." Chapter 7 of English Historical Semantics. Christian Kay and Kathryn Allan. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015. 113--31.

2017-10-30 Mon

■ #3108. ノルマン征服がなかったら,英語は・・・? [hel_education][history][loan_word][spelling][stress][rsr][gsr][rhyme][alliteration][gender][inflection][norman_conquest]

「#119. 英語を世界語にしたのはクマネズミか!?」 ([2009-08-24-1]) や「#3097. ヤツメウナギがいなかったら英語の復権は遅くなっていたか,早くなっていたか」 ([2017-10-19-1]) に続き,歴史の if を語る妄想シリーズ.ノルマン征服がなかったら,英語はどうなっていただろうか.

まず,語彙についていえば,フランス借用語(句)はずっと少なく,概ね現在のドイツ語のようにゲルマン系の語彙が多く残存していただろう.関連して,語形成もゲルマン語的な要素をもとにした複合や派生が主流であり続けたに違いない.フランス語ではなくとも諸言語からの語彙借用はそれなりになされたかもしれないが,現代英語の語彙が示すほどの多種多様な語種分布にはなっていなかった可能性が高い.

綴字についていえば,古英語ばりの hus (house) などが存続していた可能性があるし,その他 cild (child), cwic (quick), lufu (love) などの綴字も保たれていたかもしれない.書き言葉における見栄えは,現在のものと大きく異なっていただろうと想像される.<þ, ð, ƿ> などの古英語の文字も,近現代まで廃れずに残っていたのではないか (cf. 「#1329. 英語史における eth, thorn, <th> の盛衰」 ([2012-12-16-1]) や「#1330. 初期中英語における eth, thorn, <th> の盛衰」 ([2012-12-17-1])) .

発音については,音韻体系そのものが様変わりしたかどうかは疑わしいが,強勢パターンは現在と相当に異なっていたものになっていたろう.具体的にいえば,ゲルマン的な強勢パターン (Germanic Stress Rule; gsr) が幅広く保たれ,対するロマンス的な強勢パターン (Romance Stress Rule; rsr) はさほど展開しなかったろうと想像される.詩における脚韻 (rhyme) も一般化せず,古英語からの頭韻 (alliteration) が今なお幅を利かせていただろう.

文法に関しては,ノルマン征服とそれに伴うフランス語の影響がなかったら,英語は屈折に依拠する総合的な言語の性格を今ほど失ってはいなかったろう.古英語のような複雑な屈折を純粋に保ち続けていたとは考えられないが,少なくとも屈折の衰退は,現実よりも緩やかなものとなっていた可能性が高い.古英語にあった文法性は,いずれにせよ消滅していた可能性は高いが,その進行具合はやはり現実よりも緩やかだったに違いない.また,強変化動詞を含めた古英語的な「不規則な語形変化」も,ずっと広範に生き残っていたろう.これらは,ノルマン征服後のイングランド社会においてフランス語が上位の言語となり,英語が下位の言語となったことで,英語に遠心力が働き,言語の変化と多様化がほとんど阻害されることなく進行したという事実を裏からとらえた際の想像である.ノルマン征服がなかったら,英語はさほど自由に既定の言語変化の路線をたどることができなかったのではないか.

以上,「ノルマン征服がなかったら,英語は・・・?」を妄想してみた.実は,これは先週大学の演習において受講生みんなで行なった妄想である.遊び心から始めてみたのだが,歴史の因果関係を確認・整理するのに意外と有効な方法だとわかった.歴史の if は,むしろ思考を促してくれる.

2017-10-29 Sun

■ #3107. 「ノルマン征服と英語」のまとめスライド [slide][norman_conquest][history][french][loan_word][link][hel_education][asacul]

英語史におけるノルマン征服の意義について,スライド (HTML) にまとめてみました.こちらからどうぞ.

これまでも「#2047. ノルマン征服の英語史上の意義」 ([2014-12-04-1]) を始め,norman_conquest の記事で同じ問題について考えてきましたが,当面の一般的な結論として,以下のようにまとめました.

1. ノルマン征服は(英国史のみならず)英語史における一大事件.

2. 以降,英語は語彙を中心にフランス語から多大な言語的影響を受け,

3. フランス語のくびきの下にあって,かえって生き生きと変化し,多様化することができた

詳細は各々のページをご覧ください.本ブログ内のリンクも豊富に張っていますので,適宜ジャンプしながら閲覧すると,全体としてちょっとした読み物になると思います.また,フランス語が英語に及ぼした(社会)言語学的影響の概観ともなっています.

1. ノルマン征服と英語

2. 要点

3. (1) ノルマン征服 (Norman Conquest)

4. ノルマン人の起源

5. 1066年

6. ノルマン人の流入とイングランドの言語状況

7. (2) 英語への言語的影響

8. 語彙への影響

9. 英語語彙におけるフランス借用語の位置づけ (#1210)

10. 語形成への影響 (#96)

11. 綴字への影響

12. 発音への影響

13. 文法への影響

14. (3) 英語への社会的影響 (#2047)

15. 文法への影響について再考

16. まとめ

17. 参考文献

18. 補遺1: 1300年頃の Robert of Gloucester による年代記 (ll. 7538--47) の記述 (#2148)

19. 補遺2: フランス借用語(句)の例 (#1210)

他の「まとめスライド」として,「#3058. 「英語史における黒死病の意義」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-09-10-1]),「#3068. 「宗教改革と英語史」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-09-20-1]),「#3089. 「アメリカ独立戦争と英語」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-10-11-1]),「#3102. 「キリスト教伝来と英語」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-10-24-1]) もご覧ください.

2017-10-24 Tue

■ #3102. 「キリスト教伝来と英語」のまとめスライド [slide][christianity][history][bible][runic][alphabet][latin][loan_word][link][hel_education][asacul]

英語史におけるキリスト教伝来の意義について,まとめスライド (HTML) を作ったので公開する.こちらからどうぞ.大きな話題ですが,キリスト教伝来は英語に (1) ローマン・アルファベットによる本格的な文字文化を導入し,(2) ラテン語からの借用語を多くもたらし,(3) 聖書翻訳の伝統を開始した,という3つの点において,英語史上に計り知れない意義をもつと結論づけました.

1. キリスト教伝来と英語

2. 要点

3. ブリテン諸島へのキリスト教伝来 (#2871)

4. 1. ローマン・アルファベットの導入

5. ルーン文字とは?

6. 現存する最古の英文はルーン文字で書かれていた

7. 古英語アルファベット

8. 古英語の文学 (#2526)

9. 2. ラテン語の英語語彙への影響

10. 外来宗教が英語と日本語に与えた言語的影響の比較 (#206)

11. 3. 聖書翻訳の伝統の開始

12. 多数の慣用表現

13. まとめ

14. 参考文献

15. 補遺1: Beowulf の冒頭の11行 (#2893)

16. 補遺2:「主の祈り」の各時代のヴァージョン (#1803)

他の「まとめスライド」として,「#3058. 「英語史における黒死病の意義」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-09-10-1]),「#3068. 「宗教改革と英語史」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-09-20-1]),「#3089. 「アメリカ独立戦争と英語」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-10-11-1]) もご覧ください.

2017-10-12 Thu

■ #3090. 英語英文学は南方から滋養をとってきた [literature][borrowing][loan_word]

福原 (33) によれば,英文学がドイツ文学から影響を受け始めたのは,Carlyle の手を経ての19世紀のことであり,それ以前にはほとんどなかった.言語上の接触についても,「#2164. 英語史であまり目立たないドイツ語からの借用」 ([2015-03-31-1]),「#2621. ドイツ語の英語への本格的貢献は19世紀から」 ([2016-06-30-1]) で触れたとおり,英語はドイツ語からの影響を比較的最近まで受けていなかった.英語の文学・言語がドイツの言語・文学と長らく接点をもたなかったことは,一般に英語英文学が,主に北方ではなく南方から滋養をとってきた歴史を反映している.福原 (33--34) は,英文学におけるこの歴史的傾向について次のように述べている.

英文學といふものは,どうも南方から滋養を取つてくるので,北方文學はあまり奮ひません.十九世紀末につてイプセンが來ます.それから,二十世紀になりまして,ロシア文學が入つて参りますけれども,どうも性に合はないらしく,トルストイもドストエフスキーも十分消化されないやうでありました.〔中略〕そんなわけで北よりも南,ことに十九世紀末は,フランスの頽廢派の文學に共鳴した友人達が輩出いたしました〔後略〕.

英語史,とりわけ英語の語彙借用史に照らしても,概ね「南方」の言語(フランス語,ラテン語,ギリシア語など)から滋養をとってきたことは事実である.確かに古ノルド語,低地地方の言語など「北方」のゲルマン諸語からの借用語もあったが,少なくとも量的な観点からみれば明らかに「南方」過多といってよいだろう.

文学にせよ言語にせよ,本来的に北方的な体質をもっていたところに,歴史的に南方的な滋養が入り込んで,現在あるような English ができあがってきた.これは,英文学史と英語史を大きく俯瞰する視点である.

・ 福原 麟太郎 『英文学入門』 河出書房,1951年.

2017-08-31 Thu

■ #3048. kangaroo の語源 [etymology][loan_word][language_myth][folk_etymology]

オーストラリアの有袋類 kangaroo の語源について,多くの人が耳にしたことがあるだろう.それによると,オーストラリアの原住民 (Aborigine) の言語に由来するが,もともとはその動物を指す語ではなかったという.Captain Cook が原住民に動物の名前を尋ねたところ,この語が返ってきたのだが,それは原住民の言語で I don't know. ほどを意味するものだったという.つまり,勘違いが原因で生まれた一種の民間語源 (folk_etymology) とも考えられる例だ.しかし,この語源説は後世の俗説と思われる.このまことしやかな説は広く流布することになり,現在でも再生産され続けている.

では,実際のところはどうだったのか.語源説に絶対的な正解はないといってよいが,I don't know 説よりはずっと信憑性があると考えられる説を紹介しよう.オーストラリア原住民の諸言語のなかに,かの動物のうちでも大型の黒い種類を指して gangaru, gangurru, ganurru などと呼ぶ言語がある(北西部の Guugu Yimidhirr).おそらくこれが kangaroo という形態で西洋の言語へ借用されたのだろう.その後,西洋の言語で確立したこの語が,オーストラリア原住民の他の言語へも広がった.つまり,実は多くの原住民の言語にとって,kangaroo は西洋からの借用語ということである.

Horobin (136--37) がこの過程を説明している.

Sadly, the story that the name of the kangaroo derives from the locals' bemused response, 'I do not know', when asked the name of the animal, appears to be entirely fictional; rather more prosaically, the word kangaroo comes from a native word ganurru. The word and the animal were introduced to the English in an account of Captain Cook's expedition of 1770. Shortly after this, during his tour of the Hebrides, Dr Johnson is reputed to have performed an imitation of the animal, gathering up the tails of his coat to resemble a pouch and bounding across the room. Later voyages to Botany Bay brought English settlers into contact with Aboriginals who knew the kangaroo by the alternative name patagaran, but who subsequently adopted the word kangaroo. Kangaroo, therefore, is an interesting example of a word borrowed into one Aboriginal language from another, via European settlers.

American Heritage Dictionary の Notes より,kangaroo も要参照.

・ Horobin, Simon. How English Became English: A Short History of a Global Language. Oxford: OUP, 2016.

2017-08-22 Tue

■ #3039. 連載第8回「なぜ「グリムの法則」が英語史上重要なのか」 [grimms_law][consonant][loan_word][sound_change][phonetics][french][latin][indo-european][etymology][cognate][germanic][romance][verners_law][sgcs][link][rensai]

昨日付けで,英語史連載企画「現代英語を英語史の視点から考える」の第8回の記事「なぜ「グリムの法則」が英語史上重要なのか」が公開されました.グリムの法則 (grimms_law) について,本ブログでも繰り返し取り上げてきましたが,今回の連載記事では初心者にもなるべくわかりやすくグリムの法則の音変化を説明し,その知識がいかに英語学習に役立つかを解説しました.

連載記事を読んだ後に,「#103. グリムの法則とは何か」 ([2009-08-08-1]) および「#102. hundred とグリムの法則」 ([2009-08-07-1]) を読んでいただくと,復習になると思います.

連載記事では,グリムの法則の「なぜ」については,専門性が高いため触れていませんが,関心がある方は音声学や歴史言語学の観点から論じた「#650. アルメニア語とグリムの法則」 ([2011-02-06-1]) ,「#794. グリムの法則と歯の隙間」 ([2011-06-30-1]),「#1121. Grimm's Law はなぜ生じたか?」 ([2012-05-22-1]) をご参照ください.

グリムの法則を補完するヴェルネルの法則 (verners_law) については,「#104. hundred とヴェルネルの法則」 ([2009-08-09-1]),「#480. father とヴェルネルの法則」 ([2010-08-20-1]),「#858. Verner's Law と子音の有声化」 ([2011-09-02-1]) をご覧ください.また,両法則を合わせて「第1次ゲルマン子音推移」 (First Germanic Consonant Shift) と呼ぶことは連載記事で触れましたが,では「第2次ゲルマン子音推移」があるのだろうかと気になる方は「#405. Second Germanic Consonant Shift」 ([2010-06-06-1]) と「#416. Second Germanic Consonant Shift はなぜ起こったか」 ([2010-06-17-1]) のをお読みください.英語とドイツ語の子音対応について洞察を得ることができます.

2017-07-09 Sun

■ #2995. Augustan Age の語彙的保守性 [lexicology][emode][inkhorn_term][purism][loan_word][latin][greek]

17世紀後半から18世紀にかけて語彙の増加が比較的低迷した時期がある.この事実は「#203. 1500--1900年における英語語彙の増加」 ([2009-11-16-1]),「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1]) のグラフより,一目瞭然だろう.英国史では,一般に1700年に前後する時代は保守的で渋好みの新古典主義時代(Augustan Age) と称されており,その傾向が言語上に新語彙導入の低迷というかたちで反映していると解釈することができる(関連して,「#2650. 17世紀末の質素好みから18世紀半ばの華美好みへ」 ([2016-07-29-1]),「#2782. 18世紀のフランス借用語への「反感」」 ([2016-12-08-1]) を参照).

この時代の語彙的保守性には歴史的背景がある.1つは,先立つ時代,特に16世紀後半から17世紀前半に,ラテン語やギリシア語といった古典語から大量の語彙が流入したという事実がある.「インク壺用語」 (inkhorn_term) と揶揄されるほどの,鼻につくような外国語の洪水に特徴づけられた時代である.このような大量借用は,確かに部分的には必要だった.科学,宗教,医学,哲学などの媒介言語がラテン語から英語へと急激に切り替わる時代にあって,英語は多くの語彙を確かに必要とした.しかし,短期集中で語彙を借用した結果,早々と英語の「語彙の必要」は満たされ,続く時代にはそれ以上借用するものがなくなってきた.Augustan Age で相対的に語彙借用が減ったのは,先立つ時代の「借用しすぎ」によるところも大きかったと思われる.語彙史も,ピークばかりでは疲れてしまうということか.

もう1つの歴史的背景としては,Augustan Age は,前時代の「借用しすぎ」を差し引いても,やはり保守的な言語観に支配されていた時代だったという事実がある.例えば,Jonathan Swift (1667--1745) や Joseph Addison (1672--1719) は当時を代表する保守派の論客であり,英語の堕落を嘆き,その改善・洗練・固定化を目指すために活発な執筆活動を行なっていた.「#1947. Swift の clipping 批判」([2014-08-26-1]) や「#1948. Addison の clipping 批判」 ([2014-08-27-1]),「#2741. ascertaining, refining, fixing」 ([2016-10-28-1]) に見られるように,時代の雰囲気は,華美を避け,質実剛健を求める保守主義だったのである.

Augustan Age の全体的な言語的傾向としては上記の通りだが,個々の年でいえば,例外的に新語彙導入の目立つ年もあった.例えば,1740年代から50年代にかけては,全体として語彙増加が最も低調な時代ではあるが,1753年には Chambers' Cyclopaedia が出版されており,そこに多くの科学用語が含まれていたために,例外的に語彙の生産力が高まった年として記録されている (Beal 21) .具体例を挙げれば,ラテン語およびギリシア語から adarticulation, aeronautics, azalea, ballistics, hydrangea, primula, sphagnum, trifoliate; anthropomorphism, eczema, mnemonic, urology 等が,この年に記録されている.

・ Beal, Joan C. English in Modern Times: 1700--1945. Arnold: OUP, 2004.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow