2020-10-20 Tue

■ #4194. Meillet による借用語の定義 [loan_word][borrowing][terminology]

言語における借用 (borrowing) について,特に語の借用,すなわち借用語 (loan_word) について,本ブログでは具体例を多々挙げてきた.また,理論的にも様々に考察してきた(例えば「#44. 「借用」にみる言語の性質」 ([2009-06-11-1]),「#900. 借用の定義」 ([2011-10-14-1]),「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]),「#2010. 借用は言語項の複製か模倣か」 ([2014-10-28-1]),「#2663. 「オープン借用」と「むっつり借用」 (1)」 ([2016-08-11-1]),「#2664. 「オープン借用」と「むっつり借用」 (2)」 ([2016-08-12-1]),「#3008. 「借用とは参考にした上での造語である」」 ([2017-07-22-1]),「#3332. Aitchison による借用の4つの特徴」 ([2018-06-11-1]) などを参照.)

最近,借用語のもう1つの異なる見方を Meillet (22--23) から学んだ.ある語が借用語か否かは,よその言語から入ってきたか否かによって決まるわけではなく,その使用が前時代からの継続性に特徴づけられていないかどうかによって決まるという見方だ.例えば,現代標準英語の観点からみれば,ある語の起源こそフランス語やラテン語であっても,それが古英語期や中英語期という古い時代に入ってきたものであれば,以後,近代英語期を通じて現代にまで継続的に用いられてきたわけであるから,これは借用語ではない,ということになる.逆にみれば,古英語や中英語で用いられていた語であっても,歴史の過程で一度廃用となり,何らかの理由で現代英語において復活した語であれば,直前の時代から継続的に用いられてきたわけではないので,借用語ということになる.この借用語の定義によると,問題の単語の起源とされる言語(あるいは方言)が,比較言語学的に同系統であるかどうかは,この際関係ないということになる.

さらにいえば,「前時代」や「起源として参照される言語(あるいは方言)」に関するスケールにも可変性がある.「前時代」を100年前とするのか10年前とするのか,はたまた1年前とするのか.また,「起源として参照される言語(あるいは方言)」も,かなり狭く限定された地域方言,社会方言,レジスターなどを指すこともできる.スケールの取り方次第で,注目している語が借用語か否かが決まってくるという意味では,Meillet の定義はすぐれて相対的な定義といえよう.この相対的な視点こそが驚くほど斬新なのである.少々長いが Meillet (22--23) より核心の部分を引用しておこう.実際には,この後にも Meillet の丁寧な解説や具体例が続く.

Il importe de définir ici ce que l'on entend en linguistique par l'emprunt.

Soit une langue considérée à deux moments successifs de son développement; le vocabulaire de la seconde époque considérée se compose de deux parties, l'une qui continue le vocabulaire de la première ou qui a été constituée sur place dans l'intervalle à l'aide d'éléments compris dans ce vocabulaire, l'autre qui provient de langues étrangères (de même famille ou de familles différentes); s'il arrive que quelque mot soit créé de toutes pièces, ce n'est, semble-t-il, que d'une manière exceptionnelle, et les faits de ce genre entrent à peine en ligne de compte. Soit par exemple le latin à l'époque de la conquête de la Gaule par les Romains et le français (c'est-à-dire la langue de Paris) au commencement de XXe siècle; il y a des mots comme père, chien, lait, etċ, qui continuent simplement des mots latins; il y en a comme noyade ou pendaison qui ont été faits sur sol français avec des éléments d'origine latine, et il y en a d'autres qui sont entrés à des dates diverses: prêtre est un mot qui est entré par le groupe chrétien à l'époque impériale romaine, sous la forme presbyter; guerre, un mot germanique, apporté par les invasions germaniques, et entré dans la langue par le groupe des conquérants qui ont été maîtres du pays, à la suite de ces invasions; camp est un mot italien venu au XVe siècle par les éléments militaires qui ont fait les campagnes d'Italie; siècle est un mot pris dès avant le Xe siècle au latin écrit par les clercs et qui avait disparu de la langue commune; équiper est un terme de la langue des marins normands ou picards; foot-ball est un terme de sport venu de l'anglais il y a peu d'années; mais, par rapport au latin de l'époque de César, tous les mots en question sont également empruntés, car aucun n'est la continuation ininterrompue de mots latins de cette date, ni ne s'explique par des formes qui se soient perpétuées dans la langue sans interruption entre l'époque de César et le commencement du XXe siècle. Il n'importe pas que le mot soit emprunté à une langue non indo-européenne, comme il arrive pour orange, ou à une langue indo-européenne autre que le latin, comme prêtre, guerre, ou au latin écrit comme siècle, cause, ou à un dialecte roman comme camp, camarade, ou même à des parlers français plus ou moins proches du parisien, comme le mot foin, pris à des parlers ruraux, et que sa phonétique dénonce comme n'étant pas parisien; en aucun cas il n'y a eu continuation directe et ininterropmpue du mot latin à Paris depuis l'époque de César jusqu'au début du XXe siècle, et ceci suffit à définir l'emprunt pour la période considérée de l'histoire du français parisien. Donc la notion d'emprunt ne saurait être définie qu'à l'intérieur d'une période strictement délimitée, et pour une population strictement délimitée.

・ Meillet, Antoine. "Comment les mots changent de sens." Année sociologique 9 (1906). 1921 ed. Rpt. Dodo P, 2009.

2020-10-18 Sun

■ #4192. 形容詞 able と接尾辞 -able は別語源だった! --- hellog ラジオ版 [hellog-radio][sobokunagimon][hel_education][etymology][suffix][latin][loan_word][derivation][word_formation][productivity]

今回は,決して「素朴な疑問」としてすら提起されることのない,驚きの事実をお届けします.私もこれを初めて知ったときには,たまげました.英語史・英語学を研究していると,何年かに一度,これまでの長い英語との付き合いにおいて当たり前とみなしていたことが,音を立てて崩れていくという経験をすることがあります.hellog ラジオ版には,そのような目から鱗の落ちる経験を皆さんにもお届けすることにより,あの茫然自失体験を共有しましょう,という狙いもあります.able と -able が無関係とは信じたくない,という方は,ぜひ聴かないないようお願いします.では,こちらの音声をどうぞ.

単体の形容詞 able も接尾辞 -able も,ラテン語の形容詞(語尾)さかのぼるという点では共通していても,成り立ちはまるで異なるのです.端的にいえば,次の通りです.

・ 形容詞 able = 動詞語幹 ab + 形容詞語尾 le

・ 接尾辞 -able = つなぎの母音 a + 形容詞語尾 ble

語源的には以上の通りですが,現代英語のネイティブの共時的な感覚としては(否,ノン・ネイティブにすら),able と -able は明らかに関係があるととらえられています.この共時的な感覚があるからこそ,接尾辞 -able は「?できる」の意で多くの語幹に接続し,豊かな語彙的生産性 (productivity) を示しているのです.この問題と関連して,##4071,4072の記事セットをどうぞ.

2020-10-17 Sat

■ #4191. 科学用語の意味の諸言語への伝播について [scientific_name][scientific_english][lexicology][conceptual_metaphor][lexicology][register][loan_translation][borrowing][loan_word][latin]

科学用語に限らず,宗教的な用語など普遍的・文明的な価値をもつ語彙とその意味は,言語境界を越えて広範囲に伝播する性質をもつ.ある言語から別の言語へと語彙がほぼそのまま借用されることもあれば,翻訳されて取り込まれることもあるが,後者の場合にも翻訳語が帯びる意味は,たいていオリジナルの語と等価である.というのは,言語境界を越えて伝播するのは,語それ自体というよりは,むしろその意味 --- 問題となっている普遍的・文明的な価値 --- だからだ.

さらにいえば,単一の語のみならず関連する語彙がまとまって伝播することが多いという点では,実際に伝播しているのは,一見すると語彙やその意味のようにみえて,実はそれらの背後に潜んでいる概念メタファー (conceptual_metaphor) なのではないかという考え方もできる.

以上は,Meillet (20--21) の著名な意味変化論を読んでいたときに,ふと気付いたことである.その1節を原文で引用しておきたい.

Le fait est particulièrement sensible dans les groupes composés de savants, ou bien où l'élément scientifique tient une place importante. Les savants, opérant sur des idées qui ne sauraient recevoir une existence sensible que parle langage, sont très sujets à créer des vocabulaire spéciaux dont l'usage se répand rapidement dans les pays intéressés. Et comme la science est éminemment internationale, les termes particuliers inventés par les savants sont ou reproduits ou traduits dans des groupes qui parlent les langues communes les plus diverses. L'un des meilleurs exemples de ce fait est fourni par la scholastique dont la langue a eu un caractère éminemment européen, et à laquelle l'Europe doit la plus grande partie de ce que, dans la bigarrure de ses langues, elle a d'unité de vacabulaire et d'unité de sens des mots. Un mot comme le latin conscientia a pris dans la langue de l'école un sens bien défini, et les groupes savants ont employé ce mot même en français } les nécessités de la traduction des textes étrangers et le désir d'exprimer exactement la même idée ont fait rendre la même idée par les savants germaniques au moyen de mith-wissei en, gothique, de gi-wizzani en vieux haut-allemand (allemand moderne gewissen). Souvent les mots techniques de ce genre sont trduits littéralement et n'ont guère de sens dans la langue où ils sont transférés; ainsi le nom de l'homme qui a de la pitié, latin misericors, a été traduit littéralement en gotique arma-hairts (allemand barm-herzig) et a passé du germanique en slave, par example russe milo-serdyj. Ce sont là de pures transcriptions cléricales de mots latins.

英語における科学用語については「#616. 近代英語期の科学語彙の爆発」 ([2011-01-03-1]),「#617. 近代英語期以前の専門5分野の語彙の通時分布」 ([2011-01-04-1]),「#3166. 英製希羅語としての科学用語」 ([2017-12-27-1]) などで取り上げてきたが,今回の話題と関連して,とりわけ「#1694. 科学語彙においてギリシア語要素が繁栄した理由」 ([2013-12-16-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Meillet, Antoine. "Comment les mots changent de sens." Année sociologique 9 (1906). 1921 ed. Rpt. Dodo P, 2009.

2020-10-16 Fri

■ #4190. 借用要素を含む前置詞は少なくない [preposition][french][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology]

昨日の記事「#4189. across は a + cross」 ([2020-10-15-1]) で,across の語源に触れた.cross 自身が初期中英語期に借用された語であり,前置詞を伴った across の原型も同じく初期中英語期に初出している.一般に前置詞は高頻度の機能語として「閉じた語類」 (closed class) といわれるが,そのような語に借用要素が含まれているというのは,一見すると稀な例のように思われるかもしれない.

しかし,英語の歴史において前置詞は「閉じた語類」らしからぬ性質を示してきた.時代とともに種類が増えてきたからである.そのなかには,フランス語やラテン語などからの借用要素を含むものも少なくない.「#947. 現代英語の前置詞一覧」 ([2011-11-30-1]) を眺めてみると,比較的高頻度の前置詞に限っても,先述の across のほか (a)round, concerning, considering, despite, during, except, past などがすぐに挙がる.複合前置詞を考慮に入れれば,according to, apart from, because of, due to, in place of, regardless of なども加えられる.前置詞における借用要素は珍しくない.

歴史的な前置詞の増加は,とりわけ後期中英語から初期近代英語にかけて生じた(cf. 「#1201. 後期中英語から初期近代英語にかけての前置詞の爆発」 ([2012-08-10-1])).これは同時代のフランス語やラテン語からのインプットによるところが大きいことは明らかである.結果として,既存のものを含めた個々の前置詞の使い分けが複雑化することになり,現代の英語学習者を悩ませることにもなっている.そのような潮流の走りというべきものが,中英語の比較的早い時期に初出した across であり,around でもあるのだろう.罪深いといえば罪深い?

2020-09-10 Thu

■ #4154. 借用語要素どうしによる混種語 --- 日本語の例 [japanese][hybrid][shortening][borrowing][loan_word][etymology][word_formation][contact][purism][covid]

先日の記事「#4145. 借用語要素どうしによる混種語」 ([2020-09-01-1]) を受けて,日本語の事例を挙げたい.和語要素を含まない,漢語と外来語からなる混種語を考えてみよう.「オンライン授業」「コロナ禍」「電子レンジ」「テレビ電話」「牛カルビ」「豚カツ」などが思い浮かぶ.ローマ字を用いた「W杯」「IT革命」「PC講習」なども挙げられる.

『新版日本語教育事典』に興味深い指摘があった.

最近では,「どた(んば)キャン(セル)」「デパ(ート)地下(売り場)めぐり」のように,長くなりがちな混種語では,略語が非常に盛んである.略語の側面から多様な混種語の実態を捉えておくことは,日本語教育にとっても重要な課題である. (262)

なるほど混種語は基本的に複合語であるから,語形が長くなりがちである.ということは,略語化も生じやすい理屈だ.これは気づかなかったポイントである.英語でも多かれ少なかれ当てはまるはずだ.実際,英語における借用語要素どうしによる混種語の代表例である television も4音節と短くないから TV と略されるのだと考えることができる.

日本語では,借用語要素どうしによる混種語に限らず,一般に混種語への風当たりはさほど強くないように思われる.『新版日本語教育事典』でも,どちらかというと好意的に扱われている.

混種語の存在は,日本語がその固有要素である和語を基盤にして,外来要素である漢語,外来語を積極的に取り込みながら,さらにそれらを組み合わせることによって造語を行ない,語彙を豊富にしてきた経緯を物語っている. (262)

英語では「#4149. 不純視される現代の混種語」 ([2020-09-05-1]) で触れたように,ときに混種語に対する否定的な態度が見受けられるが,日本語ではその傾向は比較的弱いといえそうだ.

・ 『新版日本語教育事典』 日本語教育学会 編,大修館書店,2005年.

2020-09-05 Sat

■ #4149. 不純視される現代の混種語 [hybrid][etymology][word_formation][combining_form][contact][waseieigo][borrowing][loan_word][waseieigo][purism][complaint_tradition]

「#4145. 借用語要素どうしによる混種語」 ([2020-09-01-1]) で,混種語 (hybrid) の1タイプについてみた.このタイプに限らず混種語は一般に語形成が文字通り混種なため,「不純」な語であるとのレッテルを貼られやすい.とはいっても,フランス語・ラテン語要素と英語要素が結合した古くから存在するタイプ (ex. bemuse, besiege, genuineness, nobleness, readable, breakage, fishery, disbelieve) は十分に英語語彙に同化しているため,非難を受けにくい.

不純視されやすいのは,19,20世紀に形成された現代的な混種語である.たとえば amoral, automation, bi-weekly, bureaucracy, coastal, coloration, dandiacal, flotation, funniment, gullible, impedance, pacifist, speedometer などが,言語純粋主義者によって槍玉に挙げられることがある.この種の語形成はとりわけ20世紀に拡大し,genocide, hydrofoil, hypermarket, megastar, microwave, photo-journalism, Rototiller, Strip-a-gram, volcanology など枚挙にいとまがない (McArthur 490) .

Fowler の hybrid formations の項 (369) では,槍玉に挙げられることの多い混種語がいくつか列挙されているが,その後に続く議論の調子ははすこぶる寛容であり,なかなか読ませる評論となっている.

If such words had been submitted for approval to an absolute monarch of etymology, some perhaps would not have been admitted to the language. But our language is governed not by an absolute monarch, nor by an academy, far less by a European Court of Human Rights, but by a stern reception committee, the users of the language themselves. Homogeneity of language origin comes low in their ranking of priorities; euphony, analogy, a sense of appropriateness, an instinctive belief that a word will settle in if there is a need for it and will disappear if there is not---these are the factors that operate when hybrids (like any other new words) are brought into the language. If the coupling of mixed-language elements seems too gross, some standard speakers write (now fax) severe letters to the newspapers. Attitudes are struck. This is all as it should be in a democratic country. But amoral, bureaucracy, and the other mixed-blood formations persist, and the language has suffered only invisible dents.

なお,混種語は,借用要素を「節操もなく」組み合わせるという点では「和製英語」 (waseieigo) を始めとする「○製△語」に近いと考えられる.不純視される語形成の代表格である点でも,両者は似ている.そして,比較的長い言語接触の歴史をもつ言語においては,極めて自然で普通な語形成である点でも,やはり両者は似ていると思う.最後の点については「#3858. 「和製○語」も「英製△語」も言語として普通の現象」 ([2019-11-19-1]) を参照.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

・ Burchfield, Robert, ed. Fowler's Modern English Usage. Rev. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1998.

2020-09-01 Tue

■ #4145. 借用語要素どうしによる混種語 [hybrid][etymology][word_formation][combining_form][contact][waseieigo][borrowing][loan_word]

語源の異なる要素が組み合わさって形成された複合語や派生語などは混種語 (hybrid) と呼ばれる.その代表例として英語については「#96. 英語とフランス語の素材を活かした混種語 (hybrid)」 ([2009-08-01-1]) で,日本語については「#296. 外来宗教が英語と日本語に与えた言語的影響」 ([2010-02-17-1]) などで挙げてきた.他言語との接触の歴史が濃く長いと,単なる語の借用に飽き足りず,借用要素を用いて自由に造語する慣習が発達するというのは自然である.和製英語を含めた「○製△語」もしかり,今回話題の「混種語」もしかりだ.

混種語を話題にするときには,およそ借用要素と本来要素の組み合わせの例を考えることが多い.例えば,commonly や murderous では赤字斜体部分がフランス語要素,それ以外が英語本来語要素である.日本語の「を(男)餓鬼」においては「餓鬼」が漢語要素,「を」が日本語本来語要素である.

しかし,様々な言語からの借用を繰り返してきた言語にあっては,言語Aからの借用語要素と言語Bからの借用語要素が組み合わさった混種語,つまり本来語要素が含まれないタイプの混種語というのもあり得る.英単語でいえば,television はギリシア語要素の tele- とラテン語要素の vision が組み合わさった,本来語要素が含まれないタイプの混種語である.いずれの要素も借用語要素には違いなく,語源学者でない限りソース言語の違いなど通常は識別できないという事情もあるからだろうか,このタイプの混種語は相対的に注目度が低いように思われる.しかし,このタイプは実際には英語語彙のなかに相当数あるのではないか.ギリシア語やラテン語に由来する連結形 (combining_form)を用いた学術用語や専門用語の例がとりわけ多そうで,これが認知度を低めている要因かもしれない.

そんなことを思ったのは,先日,大学院生が -philia (?愛好症)と -phobia (?恐怖症)というギリシア語に由来する連結形を含む英単語を集め,前置されている第1要素の語種を調べて報告してくれたからだ.いずれの場合も,第1要素の大半は予想されるとおりギリシア語要素だったが,1/3ほどがラテン語要素だったという.「ラテン語要素+ギリシア語要素」となる例をいくつか挙げれば,Anglophilia (イングランド贔屓),canophilia (犬好き),claustrophobia (閉所恐怖症),verbophobia (単語恐怖症)などである.見過ごされやすいタイプの混種語に光が当てられ,とても勉強になった.

なお,『新英語学辞典』 (313) に,このタイプの混種語について次のように記述があったが,やはり扱いは素っ気なく,この程度にとどまっていた.

混種語は本来語と外来語の結合のみとは限らない.外来の語基・接辞についてもみられる: hypercorrect (= overly correct; Gk + L), visualize (< LL visuālis + Gk -ize) .

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2020-08-29 Sat

■ #4142. guest と host は,なんと同語源 --- hellog ラジオ版 [hellog-radio][sobokunagimon][hel_education][grimms_law][indo-european][palatalisation][old_norse][loan_word][semantic_change][doublet][antonym][french][latin][old_norse]

hellog ラジオ版も第20回となりました.今回は素朴な疑問というよりも,ちょっと驚くおもしろ語源の話題です.「客人」を意味する guest と「主人」を意味する host は,完全なる反意語 (antonym) ですが,なんと同語源なのです(2重語 (doublet) といいます).この不思議について,紀元前4千年紀という,英語の究極のご先祖様である印欧祖語 (Proto-Indo-European) の時代にまで遡って解説します.以下の音声をどうぞ.

たかだか2つの英単語を取り上げたにすぎませんが,その背後にはおよそ5千年にわたる壮大な歴史があったのです.登場する言語も,印欧祖語に始まり,ラテン語,フランス語,ゲルマン祖語,古ノルド語(北欧諸語の祖先),そして英語と多彩です.

語源学や歴史言語学の魅力は,このように何でもないようにみえる単語の背後に壮大な歴史が隠れていることです.同一語源語から,長期にわたる音変化や意味変化を通じて,一見すると関係のなさそうな多くの単語が芋づる式に派生してきたという事実も,なんとも興味深いことです.今回の話題について,詳しくは##170,171,1723,1724の記事セットをご覧ください.

2020-08-27 Thu

■ #4140. 英語に借用された日本語の「いつ」と「どのくらい」 [oed][japanese][borrowing][loan_word][lexicology][statistics]

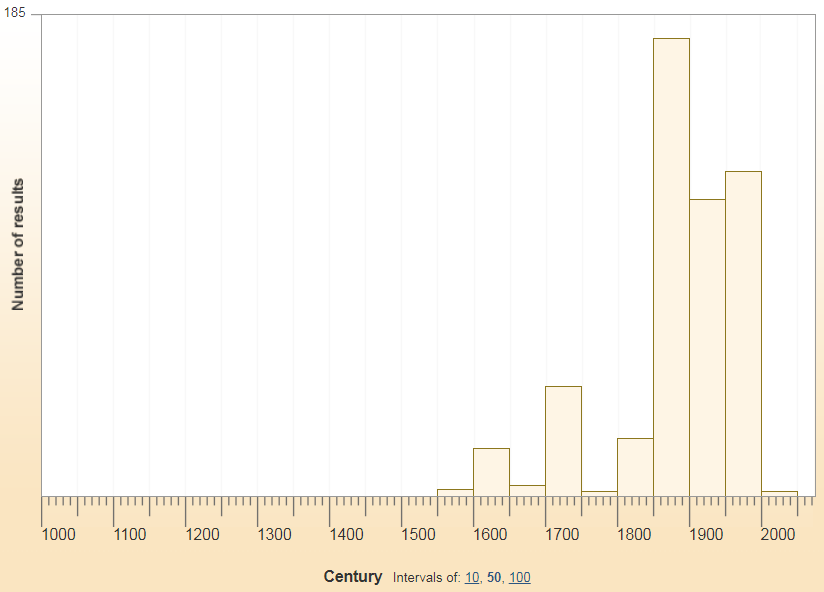

「#3872. 英語に借用された主な日本語の借用年代」 ([2019-12-03-1]),「#142. 英語に借用された日本語の分布」 ([2009-09-16-1]) などの記事で見てきたように,英語には意外と多くの日本語単語が入り込んでいる.両言語の接触は16世紀以降のことであり (cf. 「#4131. イギリスの世界帝国化の歴史を視覚化した "The OED in two minutes"」 ([2020-08-18-1])),日本語単語の借用は英語史の観点からすると比較的新しい現象とはいえるが,そこそこの存在感を示しているといってよい.このことは「#45. 英語語彙にまつわる数値」 ([2009-06-12-1]),「#126. 7言語による英語への影響の比較」 ([2009-08-31-1]),「#2165. 20世紀後半の借用語ソース」 ([2015-04-01-1]) などでも触れてきた.

OED Online には,様々なパラメータにより,どの時代にどのくらいの単語が英語語彙に加わったかを視覚化してくれる "Timelines" という便利な機能がある.たとえば「日本語が語源である単語」を指定すると,日本語からの借用語が「いつ」「どのくらい」英語に流入したのかを即座にグラフ化してくれる.その結果は以下の通り.

数としては19世紀後半から爆発的に増え始め,現代に至ることがわかる.19世紀後半といえば,もちろん我が国が英米を含む西洋諸国との濃密な接触を開始した幕末・明治維新の時代である.

棒グラフをクリックすると,該当する単語のリストも得られる.ここまで簡単な操作でグラフ化してくれるとは本当に便利な世の中になったなあ.

2020-08-25 Tue

■ #4138. フランス借用語のうち中英語期に借りられたものは4割強で,かつ重要語 [oed][french][latin][loan_word][statistics][lexicology][borrowing]

英語語彙史において,フランス借用語の流入のピークが中英語期にあったことはよく知られている.このことは「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1]),「#2162. OED によるフランス語・ラテン語からの借用語の推移」 ([2015-03-29-1]),「#2385. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計 (2)」 ([2015-11-07-1]) などのグラフを見れば,容易に理解できるだろう.

OED が提供している Middle English: an overview の "Borrowing from Latin and/or French" を読んでいたところ,この問題と関連して具体的な数字が挙げられていたので紹介しておきたい.

By 1500, over 40 per cent of all of the words that English has borrowed from French had made a first appearance in the language, including a very high proportion of those French words which have come to play a central part in the vocabulary of modern English. By contrast, the greatest peak of borrowing from Latin was still to come, in the early modern period; by 1500, under 20 per cent of the Latin borrowings found in modern English had yet entered the language.

フランス借用語の流入のピークは中英語期であり,ラテン借用語のピークは近代英語期だったという順序についての指摘はその通りだが,ここで目を引くのは,引用の最初に挙げられている40%強という数字である.現代英語語彙におけるフランス借用語のうち40%強が中英語期の借用であり,しかも現在も中核的な語彙として活躍しているという.言い方をかえれば,この時期に借用されたフランス単語は,古株ながらも現在に至るまで有用性を保ち続けているものが多いということである.残存率が高いと言ってもよい.

それに対するラテン借用語の残存率は,残念ながら数字で表わされていないが,フランス語のそれよりもずっと低いと考えられる.新参者でありながら,現在まで残っていない(あるいは少なくとも有用な語として残っていない)ものが多いのである(cf. 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]),「#1409. 生き残ったインク壺語,消えたインク壺語」 ([2013-03-06-1])).英語史において,このフランス語とラテン語の語彙的影響の差異は興味深い.

今回の話題と関連して,「#3180. 徐々に高頻度語の仲間入りを果たしてきたフランス・ラテン借用語」 ([2018-01-10-1]),「#2667. Chaucer の用いた語彙の10--15%がフランス借用語」 ([2016-08-15-1]),「#2283. Shakespeare のラテン語借用語彙の残存率」 ([2015-07-28-1]) なども参照されたい.

2020-07-26 Sun

■ #4108. boy, join, loiter --- 外来の2重母音の周辺的性格 [diphthong][vowel][phoneme][phonology][loan_word]

標記の単語に含まれる2重母音 /ɔɪ/ は,現代英語ではかなりマイナーな母音である.「#1022. 英語の各音素の生起頻度」 ([2012-02-13-1]) で確認するかぎり,母音音素としては /ʊə/ につぐ最低頻度の音素である.boy, choice, enjoy, join, poison などの日常語に現われるため,あまり実感はないかもしれないが,統計上はマイナーである.

このマイナー性の歴史的背景としては,この音素がそもそも外来のものである点を指摘できる.choice, employ, loin, moist, turmoil, soil, join, poison のようにフランス語に遡るものが圧倒的多数だが,ほかにオランダ語からの buoy, foist, loiter などもある.ギリシア語 hoi polloi,ベンガル語 poisha,中国語 hoisin,それから擬音語 ahoy, boink, oink もある.擬音語の起源にまつわる問題は別として,一般的な本来語にはルーツをたどることのできない音素なのである.

共時的にみても,この音素はマイナーな匂いを放っている.Minkova (270) は,Vachek や Lass に言及しつつ,その周辺性を次のように紹介している.

The incorporation of the new diphthong in boy, join, coin into the English phonological system is commonly described as incomplete. Vachek (1976: 162--7, 265--8) argued that lack of parallelism with the other diphthongs ([eɪ-oʊ], [aɪ-aʊ], but not *[ɛɪ-ɔɪ]) and lack of morphophonemic alternations involving [ɔɪ] in the PDE system, makes [ɔɪ] a 'peripheral' phoneme in SSBE. He hypothesised that the survival of [ɔɪ] is associated with its pragmatic function of differentiating synchronically foreign words from native words, especially polysyllabic words. Lass (1992a: 53) also emphasises the 'foreignness' of [ɔɪ] and its structural isolation, and concludes that it . . . 'has just sat there for its whole history as a kind of non-integrated "excrescence" on the English vowel system'.

一方,確かに周辺的な匂いはするものの,現代英語の体系に取り込まれていることは確かだという議論もある.(1) 他の2重母音と同様に音声実現上の変異を示す (ex. [ɔɪ], [oi], [ui]),(2) 接尾辞 -oid はこの2世紀の間,高い生産性を誇る,(3) 20世紀に入ってからの造語として oik (1917), oink (1935), boing (1952), boink (1963); droid (1952), roid (1978) などが現われてきている,などの事実だ.

いろいろな観点から興味をそそる2重母音音素といえるだろう.

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

・ Vachek, Joseph. Selected Writings in English and General Linguistics. Prague: Academia and the Hague: Mouton, 1976.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 2. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 23--154.

2020-07-24 Fri

■ #4106. gaunt, aunt, lamp, danger --- 歴史的な /a(u)NC/ がたどった4つのルート [sound_change][vowel][diphthong][gvs][phonology][phonetics][anglo-norman][french][loan_word]

歴史的に /a(u)NC/ の音連鎖をもっていた借用語は,標題に例示した通り,現代英語において4種類の発音(と揺れ)を示し得る.[ɔː ? ɑː], [ɑː ? æ(ː)], [æ(ː)], [eɪ] である.4種類間の区別は,音環境により,そしてある程度までは借用のソース方言により説明される.歴史的な /a(u)NC/ 語がたどってきた4つのルートをまとめた Minkova (241) による図表を,多少改変した形で以下に挙げよう.

| Source | Output | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| /aNC/ (AN <-aunC>) | [ɔː ? ɑː] | gaunt, haunt, laundry, saunter |

| /aNC/ (OFr <-anC>) | [ɑː ? æ(ː)] | aunt, grant, slander, sample, dance |

| /aNC#/ | [æ(ː)] | lamp, champ, blank, flank, bland |

| /aNC (palat. obstr.)/ | [eɪ] | danger, change, range, chamber |

gaunt タイプはおよそアングロ・ノルマン語に由来し,aunt タイプは古(中央)フランス語に由来する.lamp タイプは,問題の音連鎖が語末に来る場合に観察される.danger タイプは,典型的には [ʤ] の子音が関わる語にみられ,大母音変化 (gvs) を経て長母音が2重母音変化した結果を示している(中西部から北部にかけての中英語方言の [aː] がベースとなったようだ).

いずれのタイプについても,中英語のスペリングとしては母音部分が <a> のみならず <au> を示すことも多く,当時より母音四辺形の下部において音声実現上の揺れが様々にあったことが窺われる.

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2020-07-17 Fri

■ #4099. sore の意味変化 [cognitive_linguistics][semantic_change][metaphor][metonymy][loan_word][french][prototype][polysemy]

Geeraerts による,英語史と認知言語学 (cognitive_linguistics) のコラボを説く論考より.本来語 sore の歴史的な意味変化 (semantic_change) を題材にして,metaphor, metonymy, prototype などの認知言語学的な用語・概念と具体例が簡潔に導入されている.

現代英語 sore の古英語形である sār は,当時よりすでに多義だった.しかし,古英語における同語の prototypical な語義は,頻度の上からも明らかに "bodily suffering" (肉体的苦しみ)だった.この語義を中心として,それをもたらす原因としての外科的な "bodily injury, wound" (傷)や内科的な "illness" (病気)の語義が,メトニミーにより発達していた.一方,"emotional suffering" (精神的苦しみ)の語義も,肉体から精神へのメタファーを通じて発達していた.このメタファーの背景には,語源的には無関係であるが形態的に類似する sorrow (古英語 sorg)との連想も作用していただろう.

古英語 sār が示す上記の多義性は,以下の各々の語義での例文により示される (Geeraerts 622) .

(1) "bodily suffering"

þisse sylfan wyrte syde to þa sar geliðigað (ca. 1000: Sax.Leechd. I.280)

'With this same herb, the sore [of the teeth] calms widely'

(2) "bodily injury, wound"

Wið wunda & wið cancor genim þas ilcan wyrte, lege to þam sare. Ne geþafað heo þæt sar furður wexe (ca. 1000: Sax.Leechd. I.134)

'For wounds and cancer take the same herb, put it on to the sore. Do not allow the sore to increaase'

(3) "illness"

þa þe on sare seoce lagun (ca. 900: Cynewulf Crist 1356)

'Those who lay sick in sore'

(4) "emotional suffering"

Mið ðæm mæstam sare his modes (ca. 888: K. Ælfred Boeth. vii. 則2)

'With the greatest sore of his spirit

このように,古英語 sār'' は,あくまで (1) "bodily suffering" の語義を prototype としつつ,メトニミーやメタファーによって派生した (2) -- (4) の語義も周辺的に用いられていたという状況だった.ところが,続く初期中英語期の1297年に,まさに "bodily suffering" を意味する pain というフランス単語が借用されてくる.長らく同語義を担当していた本来語の sore は,この新参の pain によって守備範囲を奪われることになった.しかし,死語に追いやられたわけではない.prototypical な語義を (1) "bodily suffering" から (2) "bodily injury, would" へとシフトさせることにより延命したのである.そして,後者の語義こそが,現代英語 sore の prototype となった(他の語義が衰退し,この現代的な状況が明確に確立したのは近代英語期).

・ Geeraerts, Dirk. "Cognitive Linguistics." Chapter 59 of A Companion to the History of the English Language. Ed. Haruko Momma and Michael Matto. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. 618--29.

2020-07-16 Thu

■ #4098. 短母音に対応する <ou> について --- country, double, touch [spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][digraph][french][loan_word][etymological_respelling]

<ou> ≡ /ʌ/ の例は,挙げてみななさいと言われてもなかなか挙がらないのだが,調べてみると標題のように案外と日常的な語が出てくる.country, couple, courage, cousin, double, flourish, nourish, touch, trouble 等,けっこうある.

これらの共通点は,いずれもフランス借用語であることだ.古フランス語から現代フランス語に至るまで,かの言語では <ou> ≡ /uː/ という対応関係が確立していた.英語では中英語期以降にフランス単語が大量に借用されるとともに,この綴字と発音の対応関係も輸入されることになった.中英語の /uː/ は,その後,順当に発展すれば大母音推移 (gvs) により /aʊ/ となるはずであり,実際に現代英語ではたいてい <ou> ≡ /aʊ/ となっている (ex. about, house, noun, round, south) .しかし,中英語の /uː/ が何らかのきっかけで短母音化して /u/ となれば,大母音推移には突入せず,むしろ中舌化 (centralisation) して /ʌ/ となる.その際に綴字が連動して変化しなかった場合に,今回話題となっている <ou> ≡ /ʌ/ の関係が生まれることになった(母音の中舌化については,「#1297. does, done の母音」 ([2012-11-14-1]) と「#1866. put と but の母音」 ([2014-06-06-1]),「#2076. us の発音の歴史」 ([2015-01-02-1]) の記事を参照).

ただし <ou> ≡ /ʌ/ を示す上記の単語群は,中英語では <o> や <u> で綴られることが多く,現代風の <ou> の綴字は少し遅れてから導入されたようだ (Upward and Davidson 146) .このタイミングの背景は定かではないが,もし意識的なフランス語風綴字への回帰だとすれば,一種の語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の例ともなり得る.

なお,本来語でも <ou> ≡ /ʌ/ の事例として southern がある.固有名詞の Blount も付け加えておこう.変わり種としては,アメリカ英語綴字 mustache に対してイギリス英語綴字の moustache の例がおもしろい.Carney (147--48) も参照.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

2020-07-14 Tue

■ #4096. 3重語,4重語,5重語の例をいくつか [doublet][etymology][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology][synonym]

昨日の記事「#4094. 2重語の分類」 ([2020-07-13-1]) で取り上げた2重語 (doublet) の上を行き,3重語,4重語,5重語などの「多重語」の例を,『新英語学辞典』 (344) よりいくつか挙げたい.本ブログ内の関連する記事へのリンクも張っておく.

(a) 3重語 (triplet)

・ hale (< ME hal, hale, hail 〔北部方言〕 < OE hāl), whole (< ME hol, hool, hole 〔南部方言〕 < OE hāl), hail (← ON heill) (cf. 「#3817. hale の語根ネットワーク」 ([2019-10-09-1]))

・ place (← OF place < L platēa), plaza (← Sp. plaza < L platēa), piazza (← It. piazza < L platēa)

・ hotel (← F hôtel < OF hostel < ML hospitāle), hostel (← OF hostel < ML hospitāle), hospital (← ML hospitāle) (cf. 「#171. guest と host (2)」 ([2009-10-15-1]))

・ a, an, one (cf. 「#86. one の発音」 ([2009-07-22-1]))

(b) 4重語 (quadruplet)

・ corpse (← MF corps < OF cors < L corpus), corps (← MF corps < OF cors < L corpus), corpus (← L corpus), corse (← OF cors < L corpus)

(c) 5重語 (quintuplet)

・ palaver (← Port palavra < L parabola), parable (← OF parabole < L parabola), parabola (← L parabola), parley (← OF parlée < L parabola), parole (← F parole < L parabola)

・ discus, disk, dish, desk, dais (cf. 「#569. discus --- 6重語を生み出した驚異の語根」 ([2010-11-17-1]))

・ senior, sire, sir, seigneur, signor

なお,日本語からの4重語の例として,カード,カルタ,カルテ,チャートが挙げられている (cf. 「#1027. コップとカップ」 ([2012-02-18-1])).

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2020-07-13 Mon

■ #4095. 2重語の分類 [doublet][etymology][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology][synonym]

同一語源にさかのぼるが,何らかの理由で形態と意味が異なるに至った1組の語を2重語 (doublet) と呼ぶ.本ブログでも様々な種類の2重語の例を挙げてきた(特に詳細な一覧は「#1723. シップリーによる2重語一覧」 ([2014-01-14-1]) と「#1724. Skeat による2重語一覧」 ([2014-01-15-1]) を参照).2重語にはいくつかのタイプがあるが,『新英語学辞典』 (343--44) に従って,歴史言語学的な観点から分類して示そう.

(1) 借用経路の異なるもの.

・ sure (← OF sur < L sēcūrus), secure (← L sēcūrus)

・ poor(← OF povre, poure < L pauper), pauper (← L pauper)

・ filibuster (← Sp. filibustero ← Du. vrijbuiter), freebooter (← Du. vrijbuiter)

・ caste (← Port. casta < L castus), chaste (← OF chaste < L castus)

・ madam(e) (← OF ma dame < L mea domina), Madonna (← It. ma donna < L mea domina)

(2) 本来語と外来語によるもの.

・ shirt (< OE scyrte < *skurtjōn-), skirt (← ON skyrta < *skurtjōn-)

・ naked (< OE nacod, næcad), nude (← L nūdus)

・ brother (< OE brōðor), friar (← OF frere < L frāter)

・ name (< OE nama), noun (← AN noun < L nōmen)

・ kin (< OE cynn), genus (← L genus)

(3) 同一言語から異なる時期に異なる形態あるいは意味で借用されたもの.

・ cipher (← OF cyfre ← Arab. ṣifr), zero (← F zéro ← It. zero ← Arab. ṣifr)

・ count (← OF conter < L computāre), compute (← MF compoter < L computāre)

・ annoy (← OF anuier, anoier < L in odio), ennui (← F ennui < OF enui < L in odio)

(4) 同一言語の異なる方言からの借用によるもの.(cf. 「#76. Norman French vs Central French」 ([2009-07-13-1]),「#95. まだある! Norman French と Central French の二重語」 ([2009-07-31-1]),「#388. もっとある! Norman French と Central French の二重語」 ([2010-05-20-1]))

・ catch (← ONF cachier), chase (← OF chacier)

・ wage (← ONF wagier), gage (← OF guage)

・ warden (← ONF wardein), guardian (← OF guardien)

・ warrant (← ONF warantir), guarantee (← OF guarantie)

・ treason (← AN treyson < OF traison < L traditionis), traditiion (← OF tradicion < L traditionis) (cf. 「#944. ration と reason」 ([2011-11-27-1]))

(5) 英語史の中で同一語が,各種の形態変化により分裂 (split) し,二つの異なる語になったものがある.本来語にも借用語にも認められる.

・ outermost, uttermost

・ thresh, thrash

・ of, off

・ than, then (cf. 「#1038. then と than」 ([2012-02-29-1]))

・ through, thorough (cf. 「#55. through の語源」 ([2009-06-22-1]))

・ wight, whit

・ worked, wrought (cf. 「#2117. playwright」 ([2015-02-12-1]))

・ later, latter (cf. 「#3616. 語幹母音短化タイプの比較級に由来する latter, last, utter」 ([2019-03-22-1]),「#3622. latter の形態を説明する古英語・中英語の "Pre-Cluster Shortening"」 ([2019-03-28-1]))

・ to, too

・ mead, meadow

・ shade, shadow (cf. 「#194. shadow と shade」 ([2009-11-07-1]))

・ twain, two (cf. 「#1916. 限定用法と叙述用法で異なる形態をもつ形容詞」 ([2014-07-26-1]))

・ fox, vixen

・ acute, cute

・ example, sample (cf. 「#548. example, ensample, sample は3重語」 ([2010-10-27-1]))

・ history, story

・ mode, mood (cf. 「#3984. 言語学でいう法 (mood) とは何ですか? (2)」 ([2020-03-24-1]))

・ parson, person (cf. 「#179. person と parson」 ([2009-10-23-1]))

・ fancy, fantasy

・ van, caravan

・ varsity, university

・ flour, flower (cf. 「#183. flower と flour」 ([2009-10-27-1]))

・ travail, travel

上記の2重語の例のいくつかについては,本ブログでも記事で取り上げたものがあり,リンクを張っておいた.その他の2重語についても両語を検索欄に入れればヒットするかもしれない.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2020-07-10 Fri

■ #4092. shit, ordure, excrement --- 語彙の3層構造の最強例 [lexicology][synonym][loan_word][borrowing][french][latin][lexical_stratification][swearing][taboo][slang][euphemism]

いかがでしょう.汚いですが,英語の3層構造を有便雄弁に物語る最強例の1つではないかと思っています.日本語の語感としては「クソ」「糞尿」「排泄物」ほどでしょうか.

英語語彙の3層構造については,本ブログでも「#3885. 『英語教育』の連載第10回「なぜ英語には類義語が多いのか」」 ([2019-12-16-1]) やそこに張ったリンク先の記事,また (lexical_stratification) などで,繰り返し論じてきました.具体的な例も「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]),「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1]) で挙げてきました.

もっと挙げてみよと言われてもなかなか難しく,典型的な ask, question, interrogate や help, aid, assistance などを挙げて済ませてしまうのですが,決して満足はしておらず,日々あっと言わせる魅力的な例を探し求めいました.そこで,ついに標題に出くわしたのです.Walker の swearing に関する記述を読んでいたときでした (32) .

A few taboo words describing body parts started out as the 'normal' forms in Old English; one of the markers of the status difference between Anglo-Norman and Old English is the way the 'English' version became unacceptable, while the 'French' version became the polite or scientific term. The Old English 'scitte' gave way to the Anglo-Norman 'ordure' and later the Latin-via-French 'excrement'.

これに出会ったときは,(鼻をつまんで)はっと息を呑み,目を輝かせてしまいました.

shit は古英語 scitte にさかのぼる本来語ですが,古英語での意味は「(家畜の)下痢」でした. 動詞としては接頭辞つきで bescītan (汚す)のように長母音を示していましたが,後に名詞からの影響もあって短化し,中英語期に s(c)hite(n) (糞をする)が現われています.名詞の「糞」の語義としては意外と新しく,初期近代英語期の初出です.

ordure は,古フランス語 ordure から中英語期に入ったもので,「汚物」「卑猥な言葉」「糞」を意味しました.語根は horrid (恐ろしい)とも共通します.

excrement は初期近代英語期にラテン語 excrēmentum (あるいは対応するフランス語 excrément)から借用されました.

現在では本来語の shit は俗語・タブー的な「匂い」をもち,その婉曲表現としては「匂い」が少し緩和されたフランス語 ordure が用いられます.ラテン語 excrement は,さらに形式張った学術的な響きをもちますが,ほとんど「匂い」ません.

以上,失礼しました.

・ Walker, Julian. Evolving English Explored. London: The British Library, 2010.

2020-06-30 Tue

■ #4082. chief, piece, believe などにみられる <ie> ≡ /i:/ [spelling][digraph][orthography][vowel][gvs][french][loan_word][etymological_respelling]

英語圏の英語教育でよく知られたスペリングのルールがある."i before e except after c" というものだ.長母音 /iː/ に対応するスペリングについては,「#2205. proceed vs recede」 ([2015-05-11-1]) や「#2515. 母音音素と母音文字素の対応表」 ([2016-03-16-1]) でみたように多種類が確認されるが,そのうちの2つに <ie> と <ei> がある.標題の語のように <ie> のものが多いが,receive, deceive, perceive のように <ei> を示す語もあり,学習上混乱を招きやすい.そこで,上記のルールが唱えられるわけである.実用的なルールではある.

今回は,なぜ標題のような語群で <ie> ≡ /iː/ の対応関係がみられるのか,英語史の観点から追ってみたい.まず,この対応関係を示す語を Carney (331) よりいくつか挙げておこう.リストの後半には固有名詞も含む.

achieve, achievement, belief, believe, besiege, brief, chief, diesel, fief, field, fiend, grief, grieve, hygiene, lief, liege, lien, mien, niece, piece, priest, reprieve, shield, shriek, siege, thief, thieves, wield, yield; Brie,, Fielden, Gielgud, Kiel, Piedmont, Rievaulx, Siegfried, Siemens, Wiesbaden

リストを語源の観点から眺めてみると,believe, field, fiend, shield などの英語本来語も含まれているとはいえ,フランス語やラテン語からの借用語が目立つ.実際,この事実がヒントになる.

brief /briːf/ という語を例に取ろう.これはラテン語で「短い」を意味する語 brevis, brevem に由来する.このラテン単語は後の古フランス語にも継承されたが,比較的初期の中英語に影響を及ぼした Anglo-French では bref という語形が用いられた.中英語はこのスペリングで同単語を受け入れた.中英語当時,この <e> で表わされた音は長母音 /eː/ であり,初期近代英語にかけて生じた大母音推移 (gvs) を経て現代英語の /iː/ に連なる.つまり,発音に関しては,中英語以降,予測される道程をたどったことになる.

しかし,スペリングに関しては,少し込み入った事情があった.古フランス語といっても方言がある.Anglo-French でこそ bref という語形を取っていたが,フランス語の中央方言では brief という語形も取り得た.英語は中英語期にはほぼ Anglo-French 形の bref に従っていたが,16世紀にかけて,フランス語の権威ある中央方言において異形として用いられていた brief という語形に触発されて,スペリングに関して bref から brief へと乗り換えたのである.

一般に初期近代英語期には権威あるスペリングへの憧憬が生じており,その憧れの対象は主としてラテン語やギリシア語だったのだが,場合によってはこのようにフランス語(中央方言)のスペリングへの傾斜という方向性もあった (Upward and Davidson (105)) .

こうして,英語において,長母音に対応する <e> が16世紀にかけて <ie> へと綴り直される気運が生じた.この気運の発端こそフランス語からの借用語だったが,やがて英語本来語を含む上記の語群にも一般的に綴りなおしが適用され,現代に至る.

細かくみれば,上述の経緯にも妙な点はある.Jespersen (77) によれば,フランス語の中央方言では achieve や chief に対応する語形は <ie> ではなく <e> で綴られており,初期近代英語が憧れのモデルと据えるべき <ie> がそこにはなかったはずだからだ(cf. 現代フランス語 achever, chef).

それでも,多くの単語がおよそ同じタイミングで <e> から <ie> へ乗り換えたという事実は重要である.正確にいえば語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の例とは呼びにくい性質を含むが,その変種ととらえることはできるだろう.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. London: Allen and Unwin, 1909.

2020-06-19 Fri

■ #4071. 意外や意外 able と -able は別語源 [etymology][suffix][latin][loan_word][derivation][word_formation][productivity]

標題に驚くのではないでしょうか..形容詞 able と接尾辞 -able は語源的には無関係なのです.スペリングは同一,しかも「?できる」という意味を共有していながら,まさか語源的なつながりがないとは信じがたいことですが,事実です.いずれも起源はラテン語に遡りますが,別語源です.

形容詞 able は,ラテン語 habilem に由来し,これがフランス語 (h)abile, able を経て中英語期に入ってきました.当初より「?できる」「有能な」の語義をもっていました.ラテン語 habilem は,動詞 habēre (もつ,つかむ)に形容詞を作る接尾辞 -ilis を付した派生語に由来します(同接尾辞は英語では -ile として,agile, fragile, juvenile, textile などにみられます).

一方,接尾辞 -able はラテン語の「?できる」を意味する接尾辞 -ābilis に遡ります.これがフランス語を経てやはり中英語期に -able として入ってきました.ラテン語の形式は,ā と bilis から成ります.前者は連結辞にすぎず,形容詞を作る接尾辞として主たる役割を果たしているのは後者です.連結辞とは,基体となるラテン語の動詞の不定詞が -āre である場合(いわゆる第1活用)に,接尾辞 bilis をスムーズに連結させるための「つなぎ」のことです.積極的な意味を担っているというよりは,語形を整えるための形式的な要素と考えてください.なお,基体の動詞がそれ以外のタイプだと連結辞は i となります.英単語でいえば,accessible, permissible, visible などにみられます.

以上をまとめれば,語源的には形容詞 able は ab と le に分解でき,接尾辞 -able は a と ble に分解できるということになります.意外や意外 able と -able は別語源なのでした.当然ながら ability と -ability についても同じことがいえます.

語源的には以上の通りですが,現代英語の共時的な感覚としては(否,おそらく中英語期より),両要素は明らかに関連づけられているといってよいでしょう.むしろ,この関連づけられているという感覚があるからこそ,接尾辞 -able も豊かな生産性 (productivity) を獲得してきたものと思われます.

(後記 2022/10/02(Sun):この話題は 2020/10/18 に hellog-radio にて「#34. 形容詞 able と接頭辞 -able は別語源だった!」として取り上げました.以下よりどうぞ.)

2020-06-10 Wed

■ #4062. ラテン語 spirare (息をする)の語根ネットワーク [word_family][etymology][latin][loan_word][semantic_change][derivation]

「#4060. なぜ「精神」を意味する spirit が「蒸留酒」をも意味するのか?」 ([2020-06-08-1]) と「#4061. sprite か spright か」 ([2020-06-09-1]) の記事で,ラテン語 spīrāre (息をする)や spīritus (息)に由来する語としての spirit, sprite/spright やその派生語に注目してきた.「息(をする)」という基本的な原義を考えれば,メタファーやメトニミーにより,ありとあらゆる方向へ語義が展開し,派生語も生じ得ることは理解しやすいだろう.実際に語根ネットワークは非常に広い.

spiritual, spiritualist, spirituous に始まる接尾辞を付した派生語も多いが,接頭辞を伴う動詞(やそこからの派生名詞)はさらに多い.inspire は「息を吹き込む」が原義である.そこから「霊感を吹き込む」「活気を与える」の語義を発達させた.conspire の原義は「一緒に呼吸する」だが,そこから「共謀する,企む」が生じた.respire は「繰り返し息をする」すなわち「呼吸する」を意味する.perspire は「?を通して呼吸する」の原義から「発汗する;分泌する」の語義を獲得した.transpire は「(植物・体などが皮膚粘膜を通して)水分を発散する」が原義だが,そこから「しみ出す;秘密などが漏れる,知れわたる」となった.aspire は,憧れのものに向かってため息をつくイメージから「熱望する」を発達させた.expire は「(最期の)息を吐き出す」から「終了する;息絶える」となった.最後に suspire は下を向いて息をするイメージで「ため息をつく」だ.

福島や Partridge の語源辞典の該当箇所をたどっていくと,意味の展開や形態の派生の経路がよくわかる.

・ ジョーゼフ T. シップリー 著,梅田 修・眞方 忠道・穴吹 章子 訳 『シップリー英語語源辞典』 大修館,2009年.

・ 福島 治 編 『英語派生語語源辞典』 日本図書ライブ,1992年.

・ Partridge, Eric Honeywood. Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English. 4th ed. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1966. 1st ed. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul; New York: Macmillan, 1958.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow