2016-07-22 Fri

■ #2643. 英語語彙の三層構造の神話? [loan_word][french][latin][lexicology][register][lexical_stratification][language_myth]

rise -- mount -- ascend や ask -- question -- interrogate などの英語語彙における三層構造については,「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]) を始め,lexical_stratification の各記事で扱ってきた.低層の本来語,中層のフランス語,高層のラテン語という分布を示す例は確かに観察されるし,歴史的にもイングランドにおける中世以来の3言語の社会的地位ときれいに連動しているために,英語史では外せないトピックとして話題に上る.

しかし,いつでもこのようにきれいな分布が観察されるとは限らず,上記の三層構造はあくまで傾向としてとらえておくべきである.すでに「#2279. 英語語彙の逆転二層構造」 ([2015-07-24-1]) でも示したように,本来語とフランス借用語を並べたときに,最も「普通」で「日常的」に用いられるのがフランス借用語のほうであるようなケースも散見される.Baugh and Cable (182) は,英語語彙の記述において三層構造が理想的に描かれすぎている現状に警鐘を鳴らしている.

. . . such contrasts [between the English element and the Latin and French element] ignore the many hundreds of words from French that are equally simple and as capable of conveying a vivid image, idea, or emotion---nouns like bar, beak, cell, cry, fool, frown, fury, glory, guile, gullet, horror, humor, isle, pity, river, rock, ruin, stain, stuff, touch, and wreck, or adjectives such as calm, clear, cruel, eager, fierce, gay, mean, rude, safe, and tender, to take examples almost at random. The truth is that many of the most vivid and forceful words in English are French, and even where the French and Latin words are more literary or learned, as indeed they often are, they are no less valuable and important. . . . The difference in tone between the English and the French words is often slight; the Latin word is generally more bookish. However, it is more important to recognize the distinctive uses of each than to form prejudices in favor of one group above another.

三層構造の「神話」とまで言ってしまうと言い過ぎのきらいがあるが,特にフランス借用語がしばしば本来語と同じくらい「低い」層に位置づけられる事実は知っておいてよいだろう.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-07-04 Mon

■ #2625. 古ノルド語からの借用語の日常性 [old_norse][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology]

古ノルド語からの借用語には,基礎的で日常的な語彙が多く含まれていることはよく知られている.「#340. 古ノルド語が英語に与えた影響の Jespersen 評」 ([2010-04-02-1]) では,この事実を印象的に表現する Jespersen の文章を引用した.

今回は,現代英語の基礎語彙を構成しているとみなすことのできる古ノルド語からの借用語を列挙しよう.ただし,ここでいう「基礎語彙」とは,Durkin (213) が "we can identify fairly impressionistically the following items as belonging to contemporary everyday vocabulary, familiar to the average speaker of modern English" と述べているように,英語母語話者が直感的に基礎的と認識している語彙のことである.

・ pronouns: they, them, their

・ other function words: both, though, (probably) till; (archaic or regional) fro, (regional) mun

・ verbs that realize very basic meanings: die, get, give, hit, seem, take, want

・ other familiar items of everyday vocabulary (impressionistically assessed): anger, awe, awkward, axle, bait, bank (of earth), bask, bleak, bloom, bond, boon, booth, boulder, bound (for), brink, bulk, cake, calf (of the leg), call, cast, clip (= cut), club (= stick), cog, crawl, dank, daze, dirt, down (= feathers), dregs, droop, dump, egg, to egg (on), fellow, flat, flaw, fling, flit, gap, gape, gasp, gaze, gear, gift, gill, glitter, grime, guest, guild, hail (= greet), husband, ill, kettle, kid, law, leg, lift, link, loan, loose, low, lug, meek, mire, muck, odd, race (= rush, running), raft, rag, raise, ransack, rift, root, rotten, rug, rump, same, scab, scalp, scant, scare, score, scowl, scrap, scrape, scuffle, seat, sister, skill, skin, skirt, skulk, skull, sky, slant, slug, sly, snare, stack, steak, thrive, thrust, (perhaps) Thursday, thwart, ugly, wand, weak, whisk, window, wing, wisp, (perhaps) wrong.

なお,この一覧を掲げた Durkin (213) の断わり書きも付しておこう."Of course, it must be remembered that in many of these cases it is probable that a native cognate has been directly replaced by a very similar-sounding Scandinavian form and we may only wish to see this as lexical borrowing in a rather limited sense."

古ノルド語からの借用語の日常性は,しばしば英語と古ノルド語の言語接触の顕著な特異性を示すものとして紹介されるが,言語接触の類型論の立場からは,いわれるほど特異ではないとする議論もある.後者については,「#1182. 古ノルド語との言語接触はたいした事件ではない?」 ([2012-07-22-1]),「#1183. 古ノルド語の影響の正当な評価を目指して」 ([2012-07-23-1]),「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2016-06-30 Thu

■ #2621. ドイツ語の英語への本格的貢献は19世紀から [loan_word][borrowing][statistics][german]

「#2164. 英語史であまり目立たないドイツ語からの借用」 ([2015-03-31-1]) で触れたように,ドイツ語の英語への語彙的影響は案外少ない.安井・久保田 (20) は次のように述べている.

ドイツ語が1824年に至るまで,英国人に,ほとんどまったくといってよいくらい,顧みられなかったのも,驚くべきことである.ドイツ語からの借用語は16世紀からあるにはあるが,フランス語,オランダ語,スカンジナヴィア語などよりの借用語に比べると,じつに少ないのである.20世紀に入ってからでも,英国人のドイツ語に関する知識は満足すべき段階に達していない.

なお,引用中の1824年とは,Thomas Carlyle (1795--1881) が Göthe の Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship を翻訳出版した年である.

OED3 により借用語を研究した Durkin (362) によると,19世紀より前にはドイツ借用語は目立っていなかったが,19世紀前半に一気に伸張したという.19世紀後半にはその勢いがピークに達し,20世紀前半に半減した後,20世紀後半にかけて下火となるに至る. *

ドイツ借用語は全体として専門用語が多く,それが一般に目立たない理由だろう.Durkin (361) は Pfeffer and Cannon の先行研究を参照しながら,ドイツ語借用の性質と時期について次のように要約している.

Pfeffer and Cannon provide a broad analysis of their data into subject areas; those with the highest numbers of items are (in descending order) mineralogy, chemistry, biology, geology, botany; only after these do we find two areas not belonging to the natural sciences: politics and music. The remaining areas that have more than a hundred items each (including semantic borrowings) are medicine, biochemistry, philosophy, psychology, the military, zoology, food, physics, and linguistics. Nearly all of these semantic areas reflect the importance of German as a language of culture and knowledge, especially in the latter part of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century.

英語はゲルマン系 (Germanic) の言語であり,ドイツ語 (German) と「系統」関係にあるとは言えるが,上に見たように両言語は歴史的に(近現代に至ってすら)接触の機会が意外と乏しかったために,「影響」関係は僅少である.たまに「英語はドイツ語の影響を受けている」と言う人がいるが,これは系統関係と影響関係を取り違えているか,あるいは Germanic と German を同一視しているか,いずれにせよ誤解に基づいている.この誤解については「#369. 言語における系統と影響」 ([2010-05-01-1]),「#1136. 異なる言語の間で類似した語がある場合」 ([2012-06-06-1]),「#1930. 系統と影響を考慮に入れた西インドヨーロッパ語族の関係図」 ([2014-08-09-1]) を参照.

・ 安井 稔・久保田 正人 『知っておきたい英語の歴史』 開拓社,2014年.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2016-06-24 Fri

■ #2615. 英語語彙の世界性 [lexicology][loan_word][borrowing][statistics][link]

英語語彙は世界的 (cosmopolitan) である.350以上の言語から語彙を借用してきた歴史をもち,現在もなお借用し続けている.英語語彙の世界性とその歴史について,以下に本ブログ (http://user.keio.ac.jp/~rhotta/hellog/) 上の関連する記事にリンクを張った.英語語彙史に関連するリンク集としてどうぞ.

1 数でみる英語語彙

1.1 語彙の規模の大きさ (#45)

1.2 語彙の種類の豊富さ (##756,309,202,429,845,1202,110,201,384)

2 語彙借用とは?

2.1 なぜ語彙を借用するのか? (##46,1794)

2.2 借用の5W1H:いつ,どこで,何を,誰から,どのように,なぜ借りたのか? (#37)

3 英語の語彙借用の歴史 (#1526)

3.1 大陸時代 (--449)

3.1.1 ラテン語 (#1437)

3.2 古英語期 (449--1100)

3.2.1 ケルト語 (##1216,2443)

3.2.2 ラテン語 (#32)

3.2.3 古ノルド語 (##340,818)

3.3 中英語期 (1100--1500)

3.3.1 フランス語 (##117,1210)

3.3.2 ラテン語 (#120)

3.4 初期近代英語期 (1500--1700)

3.4.1 ラテン語 (##114,478)

3.4.2 ギリシア語 (#516)

3.4.3 ロマンス諸語 (#2385)

3.5 後期近代英語期 (1700--1900) と現代英語期 (1900--)

3.5.1 世界の諸言語 (##874,2165)

4 現代の英語語彙にみられる歴史の遺産

4.1 フランス語とラテン語からの借用語 (#2162)

4.2 動物と肉を表わす単語 (##331,754)

4.3 語彙の3層構造 (##334,1296,335)

4.4 日英語の語彙の共通点 (##1526,296,1630,1067)

5 現在そして未来の英語語彙

5.1 借用以外の新語の源泉 (##873,875)

5.2 語彙は時代を映し出す (##625,631,876,889)

[ 参考文献 ]

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2016-06-07 Tue

■ #2598. 古ノルド語の影響力と伝播を探る研究において留意すべき中英語コーパスの抱える問題点 [old_norse][loan_word][me_dialect][representativeness][geography][lexical_diffusion][lexicology][methodology][laeme][corpus]

「#1917. numb」 ([2014-07-27-1]) の記事で,中英語における本来語 nimen と古ノルド語借用語 taken の競合について調査した Rynell の研究に触れた.一般に古ノルド語借用語が中英語期中いかにして英語諸方言に浸透していったかを論じる際には,時期の観点と地域方言の観点から考慮される.当然のことながら,言語項の浸透にはある程度の時間がかかるので,初期よりも後期のほうが浸透の度合いは顕著となるだろう.また,古ノルド語の影響は the Danelaw と呼ばれるイングランド北部・東部において最も強烈であり,イングランド南部・西部へは,その衝撃がいくぶん弱まりながら伝播していったと考えるのが自然である.

このように古ノルド語の言語的影響の強さについては,時期と地域方言の間に密接な相互関係があり,その分布は明確であるとされる.実際に「#818. イングランドに残る古ノルド語地名」 ([2011-07-24-1]) や「#1937. 連結形 -son による父称は古ノルド語由来」 ([2014-08-16-1]) に示した語の分布図は,きわめて明確な分布を示す.古英語本来語と古ノルド語借用語が競合するケースでは,一般に上記の分布が確認されることが多いようだ.Rynell (359) 曰く,"The Scn words so far dealt with have this in common that they prevail in the East Midlands, the North, and the North West Midlands, or in one or two of these districts, while their native synonyms hold the field in the South West Midlands and the South."

しかし,事情は一見するほど単純ではないことにも留意する必要がある.Rynell (359--60) は上の文に続けて,次のように但し書きを付け加えている.

This is obviously not tantamount to saying that the native words are wanting in the former parts of the country and, inversely, that the Scn words are all absent from the latter. Instead, the native words are by no means infrequent in the East Midlands, the North, and the North West Midlands, or at least in parts of these districts, and not a few Scn loan-words turn up in the South West Midlands and the South, particularly near the East Midland border in Essex, once the southernmost country of the Danelaw. Moreover, some Scn words seem to have been more generally accepted down there at a surprisingly early stage, in some cases even at the expense of their native equivalents.

加えて注意すべきは,現存する中英語テキストの分布が偏っている点である.言い方をかえれば,中英語コーパスが,時期と地域方言に関して代表性 (representativeness) を欠いているという問題だ.Rynell (358) によれば,

A survey of the entire material above collected, which suffers from the weakness that the texts from the North and the North (and Central) West Midlands are all comparatively late and those from the South West Midlands nearly all early, while the East Midland and Southern texts, particularly the former, represent various periods, shows that in a number of cases the Scn words do prevail in the East Midlands, the North, and the North (and sometimes Central) West Midlands and the South, exclusive of Chaucer's London . . . .

古ノルド語の言語的影響は,中英語の早い時期に北部・東部方言で,遅い時期には南部・西部方言で観察される,ということは概論として述べることはできるものの,それが中英語コーパスの時期・方言の分布と見事に一致している事実を見逃してはならない.つまり,上記の概論的分布は,たまたま現存するテキストの時間・空間的な分布と平行しているために,ことによると不当に強調されているかもしれないのだ.見えやすいものがますます見えやすくなり,見えにくいものが隠れたままにされる構造的な問題が,ここにある.

この問題は,古ノルド語の言語的影響にとどまらず,中英語期に北・東部から南・西部へ伝播した言語変化一般を観察する際にも関与する問題である (see 「#941. 中英語の言語変化はなぜ北から南へ伝播したのか」 ([2011-11-24-1]),「#1843. conservative radicalism」 ([2014-05-14-1])) .

関連して,初期中英語コーパス A Linguistic Atlas of Early Middle English (LAEME) の代表性について「#1262. The LAEME Corpus の代表性 (1)」 ([2012-10-10-1]),「#1263. The LAEME Corpus の代表性 (2)」 ([2012-10-11-1]) も参照.

・ Rynell, Alarik. The Rivalry of Scandinavian and Native Synonyms in Middle English Especially taken and nimen. Lund: Håkan Ohlssons, 1948.

2016-06-04 Sat

■ #2595. 英語の曜日名にみられるローマ名の「借用」の仕方 [latin][etymology][borrowing][loan_word][loan_translation][mythology][calendar]

現代英語の曜日の名前は,よく知られているように,太陽系の主要な天体あるいは神話上それと結びつけられた神の名前を反映している.いずれも,ラテン単語の反映であり,ある意味で「借用」といってよいが,その借用の仕方に3つのパターンがみられる.

Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday については,各々の複合語の第1要素として,ローマ神 Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus に対応するゲルマン神の名前が与えられている.これは,ローマ神話の神々をゲルマン神話の神々で体系的に差し替えたという点で,"loan rendition" と呼ぶのがふさわしいだろう.(Wednesday については「#1261. Wednesday の発音,綴字,語源」 ([2012-10-09-1]) を参照.)

一方,Sunday, Monday の第1要素については,それぞれ太陽と月という天体の名前をラテン語から英語へ翻訳したものと考えられる.差し替えというよりは,形態素レベルの翻訳 "loan translation" とみなしたいところだ.

最後に Saturday の第1要素は,ローマ神話の Saturnus というラテン単語の形態をそのまま第1要素へ借用してきたので,第1要素のみに限定すれば,ここで生じたことは通常の借用 ("loan") である(複合語全体として考える場合には,第1要素が借用,第2要素が本来語なので "loanblend" の例となる;see 「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1])).

英語の曜日名に,上記のように「借用」のいくつかのパターンがみられることについて,Durkin (106) が次のように紹介しているので,引用しておきたい.

The modern English names of six of the days of the week reflect Old English or (probably) earlier loan renditions of classical or post-classical Latin names; the seventh, Saturday, shows a borrowed first element. In the cases of Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday there is substitution of the names of roughly equivalent pagan Germanic deities for the Roman ones, with the names of Tiw, Woden, Thunder or Thor, and Frig substituted for Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, and Venus respectively; in the cases of Monday and Sunday the vernacular names of the celestial bodies Moon and Sun are substituted for the Latin ones. The first element of Saturday (found in Old English in the form types Sæternesdæġ, Sæterndæġ, Sætresdæġ, and Sæterdæġ) uniquely shows borrowing of the Latin name of the Roman deity, in this case Saturn.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2016-05-18 Wed

■ #2578. ケルト語を通じて英語へ借用された一握りのラテン単語 [loan_word][latin][celtic][oe][borrowing][statistics]

ブリテン島が紀元43年から410年までのあいだローマの支配化に置かれ,島内である程度ラテン語が話されていたという事実から,この時期に用いられていたラテン単語が,後に島内の主たる言語となる英語にも,相当数残っているはずではないかと想像されるかもしれない.当時のラテン単語の多くが,ケルト語話者が媒介となって,後に英語にも伝えられたのではないかと.しかし,実際にはそのような状況は起こらなかった.Baugh and Cable (77) によると,

It would be hardly too much to say that not five words outside of a few elements found in place-names can be really proved to owe their presence in English to the Roman occupation of Britain. It is probable that the use of Latin as a spoken language did not long survive the end of Roman rule in the island and that such vestiges as remained for a time were lost in the disorders that accompanied the Germanic invasions. There was thus no opportunity for direct contact between Latin and Old English in England, and such Latin words as could have found their way into English would have had to come in through Celtic transmission. The Celts, indeed, had adopted a considerable number of Latin words---more than 600 have been identified--- but the relations between the Celts and the English were such . . . that these words were not passed on.

当時のケルト語には600語近くラテン単語が入っていたというのは,知らなかった.さて,古英語に入ったのはきっかり5語にすぎないといっているが,Baugh and Cable (77--78) が挙げているのは,ceaster (< L castra "camp"), port (< L portus, porta "harbor, gate, town"), munt (< L mōns, montem "mountain"), torr (L turris "tower, rock"), wīc (< L vīcus "village") である.これですら語源に異説のあるものもあり,ケルト語経由で古英語に入ったラテン借用語の確実な例とはならないかもしれない.その他,地名要素としての street, wall, wine などが加えられているが,いずれにせよそのようなルートで古英語に入ったラテン借用語一握りしかない.

「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1]),「#1437. 古英語期以前に借用されたラテン語の例」 ([2013-04-03-1]),「#1945. 古英語期以前のラテン語借用の時代別分類」 ([2014-08-24-1]) などで触れたように,英語史においてラテン単語の借用の波と経路は何度かあったが,この Baugh and Cable の呼ぶところのラテン単語借用の第1期に関しては,見るべきものが特に少ないと言っていいだろう.Baugh and Cable (78) の結論を引こう.

At best . . . the Latin influence of the First Period remains much the slightest of all the influences that Old English owed to contact with Roman civilization.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-03-05 Sat

■ #2504. Simon Horobin の "A history of English . . . in five words" [link][hel_education][anglo-saxon][french][loan_word][lexicology][lexicography][johnson]

2月23日付けで,オックスフォード大学の英語史学者 Simon Horobin による A history of English . . . in five words と題する記事がウェブ上にアップされた.英語に現われた年代順に English, beef, dictionary, tea, emoji という5単語を取り上げ,英語史的な観点からエッセー風にコメントしている.ハイパーリンクされた語句や引用のいずれも,英語にまつわる歴史や文化の知識を増やしてくれる良質の教材である.こういう記事を書きたいものだ.

以下,5単語の各々について,本ブログ内の関連する記事にもリンクを張っておきたい.

1. English or Anglo-Saxon

・ 「#33. ジュート人の名誉のために」 ([2009-05-31-1])

・ 「#389. Angles, Saxons, and Jutes の故地と移住先」 ([2010-05-21-1])

・ 「#1013. アングロサクソン人はどこからブリテン島へ渡ったか」 ([2012-02-04-1])

・ 「#1145. English と England の名称」 ([2012-06-15-1])

・ 「#1436. English と England の名称 (2)」 ([2013-04-02-1])

・ 「#2353. なぜアングロサクソン人はイングランドをかくも素早く征服し得たのか」 ([2015-10-06-1])

・ 「#2493. アングル人は押し入って,サクソン人は引き寄せられた?」 ([2016-02-23-1])

2. beef

・ 「#331. 動物とその肉を表す英単語」 ([2010-03-24-1])

・ 「#332. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」の神話」 ([2010-03-25-1])

・ 「#1583. swine vs pork の社会言語学的意義」 ([2013-08-27-1])

・ 「#1603. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」を最初に指摘した人」 ([2013-09-16-1])

・ 「#1604. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」を次に指摘した人たち」 ([2013-09-17-1])

・ 「#1966. 段々おいしくなってきた英語の飲食物メニュー」 ([2014-09-14-1])

・ 「#1967. 料理に関するフランス借用語」 ([2014-09-15-1])

・ 「#2352. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」の神話 (2)」 ([2015-10-05-1])

3. dictionary

・ 「#603. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (1)」 ([2010-12-21-1])

・ 「#604. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (2)」 ([2010-12-22-1])

・ 「#609. 難語辞書の17世紀」 ([2010-12-27-1])

・ 「#610. 脱難語辞書の18世紀」 ([2010-12-28-1])

・ 「#726. 現代でも使えるかもしれない教育的な Cawdrey の辞書」 ([2011-04-23-1])

・ 「#1420. Johnson's Dictionary の特徴と概要」 ([2013-03-17-1])

・ 「#1421. Johnson の言語観」 ([2013-03-18-1])

・ 「#1609. Cawdrey の辞書をデータベース化」 ([2013-09-22-1])

4. tea

・ 「#756. 世界からの借用語」 ([2011-05-23-1])

・ 「#1966. 段々おいしくなってきた英語の飲食物メニュー」 ([2014-09-14-1])

5. emoji

・ 「#808. smileys or emoticons」 ([2011-07-14-1])

・ 「#1664. CMC (computer-mediated communication)」 ([2013-11-16-1])

英語語彙全般については,「#756. 世界からの借用語」 ([2011-05-23-1]), 「#1526. 英語と日本語の語彙史対照表」 ([2013-07-01-1]) をはじめとして,lexicology や loan_word などの記事を参照.

2016-01-29 Fri

■ #2468. 「英語は語彙的にはもはや英語ではない」の評価 [lexicology][loan_word][borrowing][japanese][style][register]

英語の語彙の大部分が諸言語からの借用語から成っていること,つまり世界的 (cosmopolitan) であることは,つとに指摘されてきた.そこから,英語は語彙的にはもはや英語とはいえない,と論じることも十分に可能であるように思われる.英語は,もはや借用語彙なしでは十分に機能しえないのではないか,と.

しかし,Algeo and Pyles (293--94) は,英語における語彙借用の著しさを適切に例証したうえで,なお "English remains English" たることを独自に主張している.少々長いが,意味深い文章なのでそのまま引用する.

Enough has been written to indicate the cosmopolitanism of the present English vocabulary. Yet English remains English in every essential respect: the words that all of us use over and over again, the grammatical structures in which we couch our observations upon practically everything under the sun remain as distinctively English as they were in the days of Alfred the Great. What has been acquired from other languages has not always been particularly worth gaining: no one could prove by any set of objective standards that army is a "better" word than dright or here., which it displaced, or that advice is any better than the similarly displaced rede, or that to contend is any better than to flite. Those who think that manual is a better, or more beautiful, or more intellectual word than English handbook are, of course, entitled to their opinion. But such esthetic preferences are purely matters of style and have nothing to do with the subtle patternings that make one language different from another. The words we choose are nonetheless of tremendous interest in themselves, and they throw a good deal of light upon our cultural history.

But with all its manifold new words from other tongues, English could never have become anything but English. And as such it has sent out to the world, among many other things, some of the best books the world has ever known. It is not unlikely, in the light of writings by English speakers in earlier times, that this could have been so even if we had never taken any words from outside the word hoard that has come down to us from those times. It is true that what we have borrowed has brought greater wealth to our word stock, but the true Englishness of our mother tongue has in no way been lessened by such loans, as those who speak and write it lovingly will always keep in mind.

It is highly unlikely that many readers will have noted that the preceding paragraph contains not a single word of foreign origin. It was perhaps not worth the slight effort involved to write it so; it does show, however, that English would not be quite so impoverished as some commentators suppose it would be without its many accretions from other languages.

英語と同様に大量の借用語からなる日本語の語彙についても,ほぼ同じことが言えるのではないか.漢語やカタカナ語があふれていても,日本語はそれゆえに日本語性を減じているわけではなく,日本語であることは決してやめていないのだ,と.

現在,日本では大和言葉がちょっとしたブームである.これは,1つには日本らしさを発見しようという昨今の潮流の言語的な現われといってよいだろう.ここには,消極的にいえば氾濫するカタカナ語への反発,積極的にいえばカタカナ語を鏡としての和語の再評価という意味合いも含まれているだろう.また,コミュニケーションの希薄化した現代社会において,人付き合いを円滑に進める潤滑油として和語からなる表現を評価する向きが広がってきているともいえる.いずれにせよ,日本語における語彙階層や語彙の文体的・位相的差違を省察する,またとない機会となっている.この機会をとらえ,日本語のみならず英語の語彙について改めて論じる契機ともしたいものである.

関連して,以下の記事も参照されたい.

・ 「#153. Cosmopolitan Vocabulary は Asset か?」 ([2009-09-27-1])

・ 「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1])

・ 「#335. 日本語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-28-1])

・ 「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1])

・ 「#1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造」 ([2014-09-08-1])

・ 「#2072. 英語語彙の三層構造の是非」 ([2014-12-29-1])

・ 「#756. 世界からの借用語」 ([2011-05-23-1])

・ 「#390. Cosmopolitan Vocabulary は Asset か? (2)」 ([2010-05-22-1])

・ 「#2359. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由 (3)」 ([2015-10-12-1])

・ Algeo, John, and Thomas Pyles. The Origins and Development of the English Language. 5th ed. Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

2016-01-28 Thu

■ #2467. ルサンチマン, ressentiment, resentment [french][loan_word][latin][semantic_change][etymology]

日本語の「ルサンチマン」は,フランス語 ressentiment からの借用語である.手元にあった『現代用語の基礎知識』 (2004) によれば,「恨み.憤慨.腹立しく思って憎むこと.貧しい人の富める者に対する,恨み.被差別者の差別者に対する,被支配者の支配者に対する怨念.」とある.ニーチェが『道徳の系譜』 (1887) で用い,その後 Max Scheler や Max Weber が発展させた概念だ.

フランス語 ressentiment には「恨み,怨恨,遺恨」のほかに,古風であるが「感じ取ること;苦痛;感謝の念」ともあるから,古くは必ずしもネガティヴな感情のみに結びつけられたわけではなさそうだ.もとになった動詞 ressentir の基本的な語義も「強く感じ取る」であり,ressentir de l'amitié pour qn. (?に友情を覚える)など,ポジティヴな共起を示す例がある.

このフランス単語は,英語の resent(ment) に対応する.現在,後者の基本的な語義は「不快に思う,憤慨する,恨む」ほどであり,通常,ポジティヴな表現と共起することはない.しかし,語源的には re- + sentir と分解され,その原義は「繰り返し感じる;強く感じ取る」であるから,ネガティヴな語義への限定は後発のはずである.実際,17世紀に名詞 resentment がフランス語から英語へ借用されてたときから18--19世紀に至るまで,ポジティヴな感じ方としての「感謝」の語義も行なわれていた.伝道師が resenting God's favours (神の恩寵に対して感謝の意を抱くこと)について語っていたとおりであり,また OED では resentment, n. の語義5(廃義)として "Grateful appreciation or acknowledgement (of a service, kindness, etc.); a feeling or expression of gratitude. Obs." が確認される.

しかし,やがて語義がネガティヴな方向へ偏っていき,現在の「憤慨」の語義が通常のものとして定着した.シップリー (533) は,この語の意味の悪化 (semantic pejoration) について「人間は悪いことを記憶する傾向を本性的にもつもので「感じる」でも特に「不快に感じる」を意味するようになった」としている.シップリーは同様の例として retaliate を挙げている.ラテン語 talis (似た)を含んでいることから,原義は「似たようなことをする,同じものを返す」だったが,負の感情と行動(「目には目を」)を表わす「報復する,仕返しする」へと特化した.

・ ジョーゼフ T. シップリー 著,梅田 修・眞方 忠道・穴吹 章子 訳 『シップリー英語語源辞典』 大修館,2009年.

2016-01-04 Mon

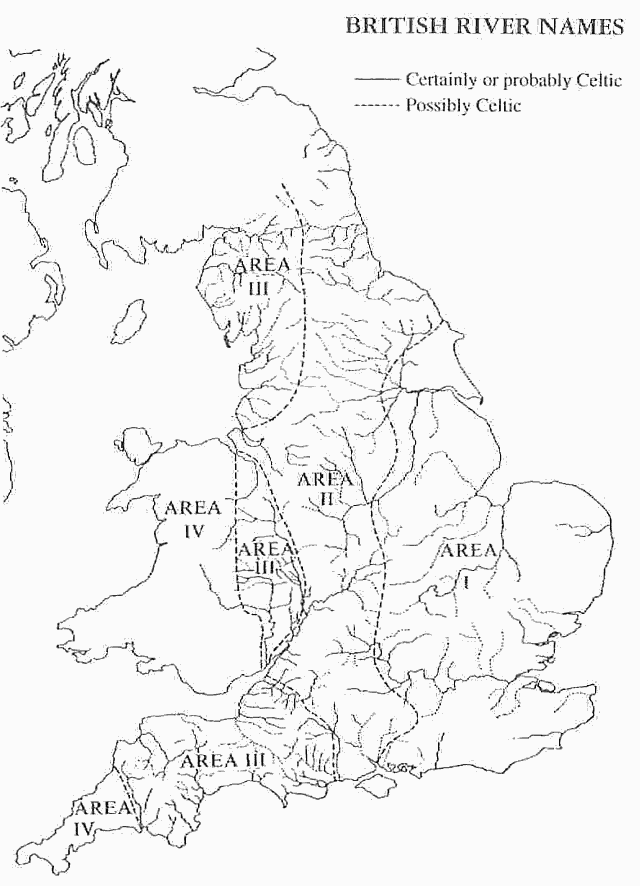

■ #2443. イングランドにおけるケルト語地名の分布 [celtic][toponymy][onomastics][geography][anglo-saxon][loan_word][history][map][hydronymy]

英語国の地名の話題については,toponymy の各記事で取り上げてきた.今回は樋口による「イングランドにおけるケルト語系地名について」 (pp. 191--209) に基づいて,イングランドのケルト語地名の分布について紹介する.

5世紀前半より,西ゲルマンのアングル人,サクソン人,ジュート人が相次いでブリテン島を襲い,先住のケルト系諸民族を西や北へ追いやり,後にイングランドと呼ばれる領域を占拠した経緯は,よく知られている (「#33. ジュート人の名誉のために」 ([2009-05-31-1]),「#389. Angles, Saxons, and Jutes の故地と移住先」 ([2010-05-21-1]),「#1013. アングロサクソン人はどこからブリテン島へ渡ったか」 ([2012-02-04-1]),「#2353. なぜアングロサクソン人はイングランドをかくも素早く征服し得たのか」 ([2015-10-06-1])) .また,征服者の英語が被征服者のケルト語からほとんど目立った語彙借用を行わなかったことも,よく知られている.ところが,「#1216. 古英語期のケルト借用語」 ([2012-08-25-1]) や「#1736. イギリス州名の由来」 ([2014-01-27-1]) でみたように,地名については例外というべきであり,ケルト語要素をとどめるイングランド地名は少なくない.とりわけイングランドの河川については,多くケルト語系の名前が与えられていることが,伝統的に指摘されてきた (cf. 「#1188. イングランドの河川名 Thames, Humber, Stour」 ([2012-07-28-1])) .

西ゲルマンの諸民族の征服・定住は,数世紀の時間をかけて,イングランドの東から西へ進行したと考えられるが,これはケルト語系地名の分布ともよく合致する.以下の地図(樋口,p. 199)は,ケルト語系の河川名の分布によりイングランド及びウェールズを4つの領域に区分したものである.東半分を占める Area I から,西半分と北部を含む Area II,そしてさらに西に連接する Area III から,最も周辺的なウェールズやコーンウォールからなる Area IV まで,漸次,ケルト語系の河川名及び地名の密度が濃くなる.

征服・定住の歴史とケルト語系地名の濃淡を関連づけると,次のようになろう.Area I は,5--6世紀にアングル人やサクソン人がブリテン島に渡来し,本拠地とした領域であり,予想されるようにここには確実にケルト語系といえる地名は極めて少ない.隣接する Area II へは,サクソン人が西方へ6世紀後半に,アングル人が北方へ7世紀に進出した.この領域では,Area I に比べれば川,丘,森林などの名前にケルト語系の地名が多く見られるが,英語系地名とは比較にならないくらい少数である.次に,7--8世紀にかけて,アングロサクソン人は,さらに西側,すなわち Devonshire, Somerset, Dorset; Worcestershire, Shropshire; Lancashire, Westmoreland, Cumberland などの占める Area III へと展開した.この領域では,川,丘,森林のほか,村落,農場,地理的条件を特徴づける語にケルト語系要素がずっと多く観察される.アングロサクソン人の Area III への進出は,Area I に比べれば2世紀ほども遅れたが,この時間の差がケルト語系地名要素の濃淡の差によく現われている.最後に,Cornwall, Wales, Monmouthshire, Herefordshire 南西部からなる Area IV は,ケルト系先住民が最後まで踏みとどまった領域であり,当然ながら,ケルト語系地名が圧倒的に多い.

このように軍事・政治の歴史が地名要素にきれいに反映している事例は少なくない.もう1つの事例として,「#818. イングランドに残る古ノルド語地名」 ([2011-07-24-1]) を参照されたい.

・ 樋口 時弘 『言語学者列伝 ?近代言語学史を飾った天才・異才たちの実像?』 朝日出版社,2010年.

2015-12-18 Fri

■ #2426. York Memorandum Book にみられる英仏羅語の多種多様な混合 [code-switching][borrowing][loan_word][french][anglo-norman][latin][bilingualism][hybrid][lexicology]

後期中英語の code-switching や macaronic な文書について,「#1470. macaronic lyric」 ([2013-05-06-1]),「#1625. 中英語期の書き言葉における code-switching」 ([2013-10-08-1]),「#1941. macaronic code-switching としての語源的綴字?」 ([2014-08-20-1]),「#2271. 後期中英語の macaronic な会計文書」 ([2015-07-16-1]),「#2348. 英語史における code-switching 研究」 ([2015-10-01-1]) などで取り上げてきた.関連して,英仏羅語の混在する15世紀の経営・商業の記録文書を調査した Rothwell の論文を読んだので,その内容を紹介する.

調査対象となった文書は York Memorandum Book と呼ばれるもので,これは次のような文書である (Rothwell 213) .

The two substantial volumes of the York Memorandum Book provide some five hundred pages of records detailing the administrative and commercial life of the second city in England over the years between 1376 and 1493, setting down in full charters, ordinances of the various trade associations, legal cases involving citizens and so on.

York Memorandum Book には,英仏羅語の混在が見られるが,混在の種類も様々である.Rothwell の分類によれば,11種類の混在のさせ方がある.Rothwell (215--16) の文章より抜き出して,箇条書きで整理すると

(i) "English words inserted without modification into a Latin text"

(ii) "English words similarly introduced into a French text"

(iii) "French words used without modification into a Latin text"

(iv) "French words similarly used in an English text"

(v) "English words dressed up as Latin in a Latin text"

(vi) "English words dressed up as French in a French text"

(vii) "French words dressed up as Latin in a Latin text"

(viii) "French words are used in a specifically Anglo-French sense in a French text"

(ix) "French words may be found in a Latin text dressed up as Latin, but with an English meaning"

(x) "On occasion, a single word may be made up of parts taken from different languages . . . or a new word may be created by attaching a suffix to an existing word, either from the same language or from one language or another""

(xi) "Outside the area of word-formation there is also the question of grammatical endings to be considered"

3つもの言語が関わり,その上で "dressed up" の有無や意味の往来なども考慮すると,このようにきめ細かな分類が得られるということも頷ける.(x) はいわゆる混種語 (hybrid) に関わる問題である (see 「#96. 英語とフランス語の素材を活かした 混種語 ( hybrid )」 ([2009-08-01-1])) .このように見ると,語彙借用,その影響による新たな語形成の発達,意味の交換,code-switching などの諸過程がいかに互いに密接に関連しているか,切り分けがいかに困難かが察せられる.

Rothwell は結論として,当時のこの種の英仏羅語の混在は,無知な写字生による偶然の産物というよりは "recognised policy" (230) だったとみなすべきだと主張している.また,14--15世紀には,業種や交易の拡大により経営・商業の記録文書で扱う内容が多様化し,それに伴って専門的な語彙も拡大していた状況において,書き手は互いの言語の単語を貸し借りする必要に迫られたに違いないとも述べている.Rothwell (230) 曰く,

Before condemning the scribes of late medieval England for their ignorance, account must be taken of the situation in which they found themselves. On the one hand the recording of administrative documents steadily increasing in number and diversity called for an ever wider lexis, whilst on the other hand the conventions of the time demanded that such documents be couched in Latin or French. No one has ever remotely approached complete mastery of the lexis of his own language, let alone that of any other language, either in medieval or modern times.

Rothwell という研究者については「#1212. 中世イングランドにおける英語による教育の始まり (2)」 ([2012-08-21-1]),「#2348. 英語史における code-switching 研究」 ([2015-10-01-1]),「#2349. 英語の復権期にフランス借用語が爆発したのはなぜか (2)」 ([2015-10-02-1]),「#2350. Prioress の Anglo-French の地位はそれほど低くなかった」 ([2015-10-03-1]),「#2374. Anglo-French という補助線 (1)」 ([2015-10-27-1]),「#2375. Anglo-French という補助線 (2)」 ([2015-10-28-1]) でも触れてきたので,そちらも参照.

・ Rothwell, William. "Aspects of Lexical and Morphosyntactical Mixing in the Languages of Medieval England." Multilingualism in Later Medieval Britain. Ed. D. A. Trotter. D. S. Brewer, 2000. 213--32.

2015-12-11 Fri

■ #2419. ギリシア・ラテン借用語における <ae> [etymological_respelling][spelling][latin][greek][loan_word][diphthong][spelling_pronunciation_gap][digraph]

昨日の記事「#2418. ギリシア・ラテン借用語における <oe>」 ([2015-12-10-1]) に引き続き,今回は <ae> の綴字について,Upward and Davidson (219--20) を参照しつつ取り上げる.

ギリシア語 <oi> が古典期ラテン語までに <oe> として取り入れられるようになっていたのと同様に,ギリシア語 <ai> はラテン語へは <ae> として取り入れられた (ex. G aigis > L aegis) .この二重字 (digraph) で表わされた2重母音は古典期以降のラテン語で滑化したため,綴字上も <ae> に代わり <e> 単体で表わされるようになった.したがって,英語では,古典期以降のラテン語やフランス語などから入った語においては <e> を示すが,古典ラテン語を直接参照しての借用語や綴り直しにおいては <ae> を示すようになった.だが,単語によっては,ギリシア語のオリジナルの <oi> と合わせて,3種の綴字の可能性が現代にも残っている例がある (ex. daimon, daemon, demon; cainozoic, caenozoic, cenozoic) .

近代英語では <ae> で綴られることもあったが,後に <e> へと単純化して定着した語も少なくない.(a)enigma, (a)ether, h(a)eresy, hy(a)ena, ph(a)enomenon, sph(a)ere などである.一方,いまだに根強く <ae> を保持しているのは,イギリス綴字における専門語彙である.aegis, aeon, aesthetic, aetiology, anaemia, archaeology, gynaecology, haemorrhage, orthopaedic, palaeography, paediatrics などがその例となるが,アメリカ綴字では <e> へ単純化することが多い.Michael という人名も,<ae> を保守している.

なお,20世紀までは,<oe> が合字 (ligature) <œ> として印刷されることが普通だったのと同様に,<ae> も通常 <æ> として印刷されていた.また,aerial が合字 <æ> や単字 <e> で綴られることがないのは,これがギリシア語の aerios に遡るものであり,2重字 <ai> に由来するものではなく,あくまで個別文字の組み合わせ <a> + <e> に由来するものだからである.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2015-12-10 Thu

■ #2418. ギリシア・ラテン借用語における <oe> [etymological_respelling][spelling][latin][greek][french][loan_word][diphthong][spelling_pronunciation_gap][digraph]

現代英語の <amoeba>, <Oedipus>, <onomatopoeia> などの綴字に見られる二重字 () の傾向により従来の <e> の代わりに <oe> が採用されたり,後者が再び廃用となるなど,単語によっても揺れがあったようだ.例えば Phoebus, Phoenician, phoenix などは語源的綴字を反映しており,現代まで定着しているが,<comoedy>, <tragoedy> などは定着しなかった.

現代英語の綴字 <oe> の採用の動機づけが,近代以降に借用されたラテン・ギリシア語彙や語源的綴字の傾向にあるとすれば,なぜそれが特定の種類の語彙に偏って観察されるかが説明される.まず,<oe> は,古典語に由来する固有名詞に典型的に見いだされる.Oedipus, Euboea, Phoebe の類いだ.ギリシア・ローマの古典上の事物・概念を表わす語も,当然 <oe> を保持しやすい (ex. oecist, poecile) .科学用語などの専門語彙も,<oe> を例証する典型的な語類である (ex. amoeba, oenothera, oestrus dioecious, diarrhoea, homoeostasis, pharmacopoeia, onomatopoeic) .

なお,<oe> は16世紀以降の印刷において,合字 (ligature) <œ> として表記されることが普通だった.<oe> の発音については,イギリス英語では /iː/ に対応し,アメリカ英語では /i/ あるいは稀に /ɛ/ に対応することを指摘しておこう.また,数は少ないが,フランス借用語に由来する <oe> もあることを言い添えておきたい (ex. oeil-de-boeuf, oeillade, oeuvre) .

以上 OED の o の項からの記述と Upward and Davidson (221--22) を参照して執筆した.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2015-11-07 Sat

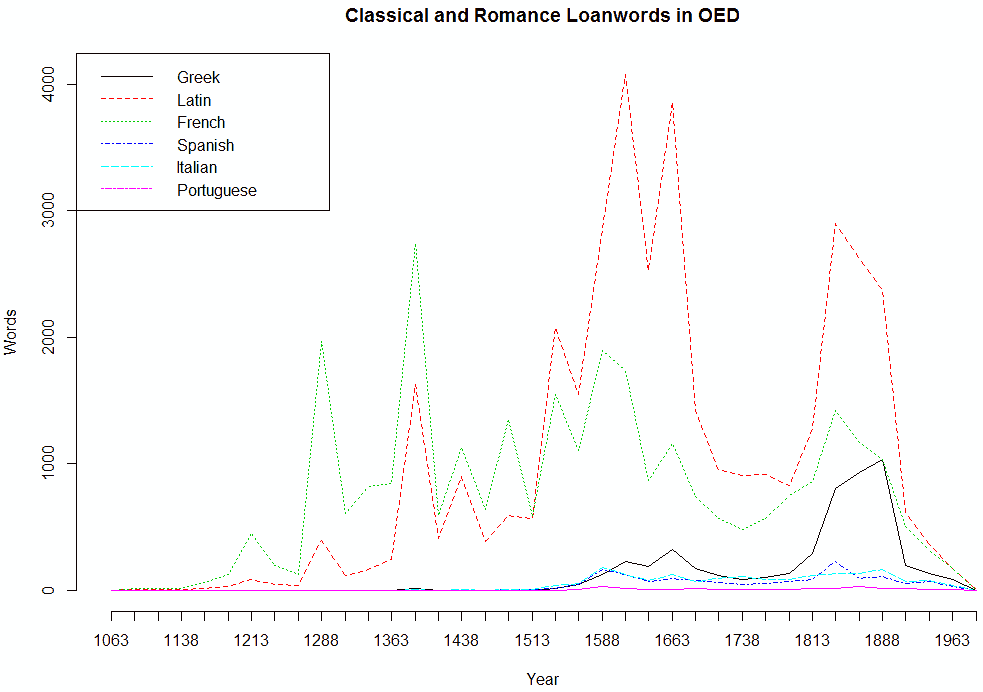

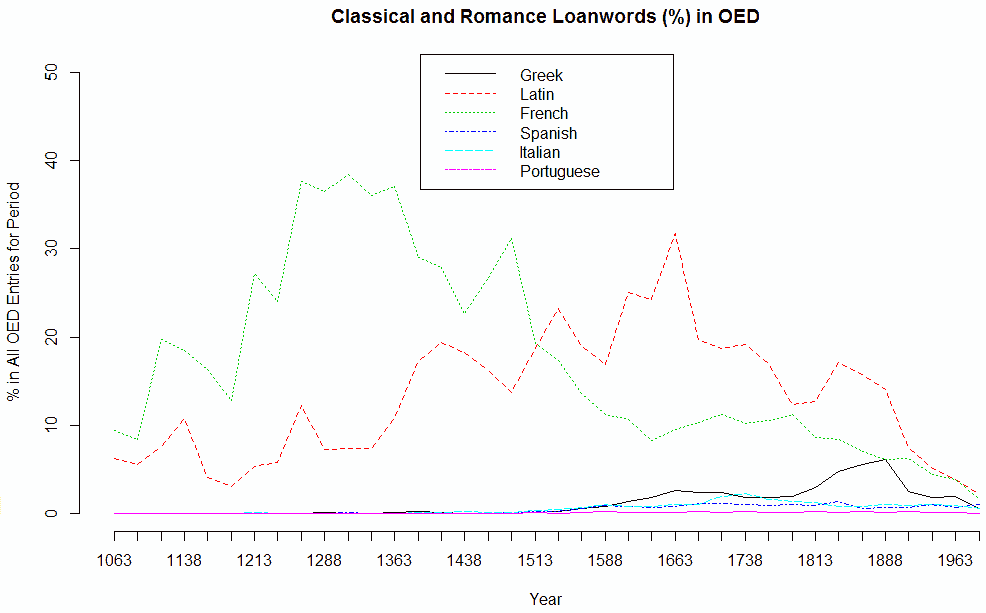

■ #2385. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計 (2) [oed][statistics][lexicology][loan_word][borrowing][latin][greek][french][italian][spanish][portuguese][romancisation]

「#2357. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計」 ([2015-10-10-1]),「#2369. 英語史におけるイタリア語,スペイン語,ポルトガル語からの語彙借用の歴史」 ([2015-10-22-1]) で,Culpeper and Clapham (218) による OED ベースのロマンス系借用語の統計を紹介した.論文の巻末に,具体的な数値が表の形で掲載されているので,これを基にして2つグラフを作成した(データは,ソースHTMLを参照).1つめは4半世紀ごとの各言語からの借用語数,2つめはそれと同じものを,各時期の見出し語全体における百分率で示したものである.

関連する語彙統計として,「#2162. OED によるフランス語・ラテン語からの借用語の推移」 ([2015-03-29-1]) で触れた Wordorigins.org の "Where Do English Words Come From?" も参照.

・ Culpeper Jonathan and Phoebe Clapham. "The Borrowing of Classical and Romance Words into English: A Study Based on the Electronic Oxford English Dictionary." International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 1.2 (1996): 199--218.

2015-10-23 Fri

■ #2370. ポルトガル語からの語彙借用 [portuguese][loan_word][borrowing][japanese]

昨日の記事「#2369. 英語史におけるイタリア語,スペイン語,ポルトガル語からの語彙借用の歴史」 ([2015-10-22-1]) に関連して,今回はとりわけポルトガル語からの借用語に焦点を当てよう.ポルトガルが海洋国家として世界に華々しく存在感を示した16世紀以降を中心として,以下のような借用語が英語へ入った (Strang 125, 宇賀治 113) .ルーツの世界性を感じることができる.

・ 新大陸より: coco(-nut) (ココヤシの木(の実)), macaw (コンゴウインコ), molasses (糖蜜[砂糖の精製過程に生じる黒色のシロップ]), sargasso (ホンダワラ類の海藻)

・ アフリカより: assagai/assegai ([南アフリカ先住民の]細身の投げ槍), guinea (ギニー(金貨)[1663--1813年間イギリスで鋳造された金貨;21 shillings に相当;本来アフリカ西部 Guinea 産の金でつくった]), madeira (マデイラワイン[ポルトガル領 Madeira 島原産の強く甘口の白ワイン]), palaver (口論;論議), yam (ヤマイモ)

・ インドより: buffalo (スイギュウ), cast(e) (カースト[インドの世襲階級制度]), emu (ヒクイドリ), joss (神像), tank ((貯水)タンク), typhoo (台風;後にギリシア語の影響で変形), verandah (ベランダ)

・ 中国より: mandarin ((中国清朝時代 (1616--1912) の)高級官吏), pagoda (パゴダ)

・ 日本より: bonze (坊主,僧)

ポルトガル本土に由来する借用語には moidore (モイドール[ポルトガル・スペインの昔の金貨;18世紀英国で通用]), port (ポート(ワイン))などがあるが,むしろ少数である.関連して「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1]) や「#756. 世界からの借用語」 ([2011-05-23-1]) で挙げた例も参照.

なお,日本語からポルトガル語を経由して英語に入った bonze は16世紀末の借用語だが,同じ時期に,ポルトガル語から日本語への語彙借用も起こっていたことに注意したい.借用語例は「#1896. 日本語に入った西洋語」 ([2014-07-06-1]) で挙げたとおりである.いずれも,当時のポルトガルの世界的な活動を映し出す鏡である.

2015-10-22 Thu

■ #2369. 英語史におけるイタリア語,スペイン語,ポルトガル語からの語彙借用の歴史 [italian][spanish][portuguese][loan_word][borrowing][statistics][lexicology]

「#2357. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計」 ([2015-10-10-1]) で少々触れたように,英語史上,フランス語に比して他の3つのロマンス諸語からの語彙借用は影が薄い.イタリア語,スペイン語,ポルトガル語の各言語からの借用語の例は,主に近代以降について「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1]) や「#756. 世界からの借用語」 ([2011-05-23-1]) で触れた.中英語にも,およそフランス語経由ではあるが,イタリア語やポルトガル語に起源をもつ語の借用があった (「#2329. 中英語の借用元言語」 ([2015-09-12-1])) .

Culpeper and Clapham (210) は,比較的マイナーなこれらのロマンス諸語からの語彙借用の歴史について,OED による語彙統計をもとに,次のように端的にまとめている.

The effect of Italian borrowing can be seen from the 15th century onwards. Italy was, and still is, famous for style in architecture and dress. It was also perceived an authority in matters to do with etiquette. Travellers to Italy --- often young sons dispatched to acquire some manners --- inevitably brought back Italian words. Italian borrowing is strongest in the 18th century (1.7% of recorded vocabulary), and is mostly related to musical terminology. Spanish and Portuguese borrowing commences in the 16th century, reflecting warfare, commerce, and colonisation, but at no point exceeds 1% of vocabulary recorded within a particular period.

まず,イタリア語からの借用語がある程度著しくなるのは,15世紀からである.「#1530. イングランド紙幣に表記されている Compa」 ([2013-07-05-1]) で言及したように,13世紀後半以降,16世紀まで,イタリアの先進的な商業・金融はイングランド経済に大きな影響を与えてきた.それが言語的余波となって顕われてきたのが,15世紀辺りからと解釈することができる.その後,イタリア借用語は18世紀の音楽用語の流入によってピークを迎えた.

一方,スペイン語とポルトガル語は,イタリア語よりもさらに目立たず,そのなかで比較的著しいといえるのは16世紀に限定される.当時,海洋国家として名を馳せた両雄の言語的な現われといえるだろう.

各言語からの語彙借用の様子は,統計的にみれば以上の通りだが,質的な違いを要約すると次の通りになる (Strang 124--26) .

(1) イタリア人は世界を開拓したり植民したりする冒険者ではなく,あくまでヨーロッパ内の旅人であった.したがって,イタリア語が提供した語彙も,ヨーロッパ的なものに限定されるといってよい.ルネサンスの発祥地ということもあり,芸術,音楽,文学,思想の分野の語彙を多く提供したことはいうまでもないが,文物を通してというよりは広い意味での旅人の口を経由して,それらの語彙が英語へ流入したとみるべきだろう.語形としては,あたかもフランス語を経由したような形態を取っていることが多い.

(2) 一方,スペイン語の流入は,イングランド女王 Mary とスペイン王 Philip II の結婚による両国の密な関係に負うところが多く,スペイン本土のみならず,新大陸に由来する語彙の少なくないことも特徴である.

(3) スペイン語以上に世界的な借用語を提供したのは,15--16世紀に航海術を発達させ,世界へと展開したポルトガルの言語である.ポルトガル語は,新大陸のみならず,アフリカやアジアからも多くの語彙をヨーロッパに持ち帰り,それが結果として英語にもたらされた.

具体的な借用語の例は,「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Culpeper Jonathan and Phoebe Clapham. "The Borrowing of Classical and Romance Words into English: A Study Based on the Electronic Oxford English Dictionary." International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 1.2 (1996): 199--218.

・ Strang, Barbara M. H. A History of English. London: Methuen, 1970.

2015-10-13 Tue

■ #2360. 20世紀のフランス借用語 [french][loan_word][borrowing][statistics][norman_french][creole][oed]

英語のフランス語との付き合いは古英語最末期より途切れることなく続いている.フランス語彙借用のピークは「#2357. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計」 ([2015-10-10-1]) や「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1]) で見たように1251--1375年だが,その後も,規模こそ縮小しながらも,借用は連綿と続いてきている.中英語以降の各時代のフランス語彙の借用については,「#1210. 中英語のフランス借用語の一覧」 ([2012-08-19-1]),「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1]),「#594. 近代英語以降のフランス借用語の特徴」 ([2010-12-12-1]), 「#678. 汎ヨーロッパ的な18世紀のフランス借用語」 ([2011-03-06-1]) を参照されたい.

今回は,現代英語におけるフランス借用語の話題を取り上げたい.Schultz は,OED Online を利用して,1900年以降に英語に入ってきたフランス語彙を調査した.Schultz がフランス借用語として取り出し,認定したのは,1677語である.Schultz の論文では,それらを14個の意味分野(とさらなる下位区分)ごとに整理し,サンプル語を列挙しているが,ここでは12分野それぞれに属する語の数と割合のみを示そう (Shultz 4--6) .

(1) Anthropology (11 borrowings, i.e. 0.7%)

(2) Metapsychics and parapsychology (11 borrowings, i.e. 0.7%)

(3) Archaeology (30 borrowings, i.e. 1.8%)

(4) Miscellaneous (46 borrowings, i.e. 2.7%)

(5) Technology (62 borrowings, i.e. 3.7%)

(6) La Francophonie (63 borrowings, i.e. 3.8%)

(7) Fashion and lifestyle (77 borrowings, i.e. 4.6%)

(8) Entertainment and leisure activities (86 borrowings, i.e. 5.1%)

(9) Mathematics and the humanities (92 borrowings, i.e. 5.5%)

(10) People and everyday life (154 borrowings, i.e. 9.2%)

(11) Civilization and politics (156 borrowings, i.e. 9.3%)

(12) Gastronomy (179 borrowings, i.e. 10.7%)

(13) Fine arts and crafts (260 borrowings, i.e. 15.5%)

(14) The natural sciences (450 borrowings, i.e. 26.8%)

20世紀のフランス借用語の特徴は何だろうか.1つは,Schultz が "the vocabulary recently adopted from French is characterized by its great variety, ranging from words related to everyday matters to highly specific terms in technology and science" (8) とまとめているように,意味分野の幅広さが挙げられる.食,芸術,自然科学が相対的に強いが,全体としてはマルチジャンルといってよい.ただし,マルチジャンルであることは中英語期のフランス借用語の特徴にも当てはまることから,これは英語史におけるフランス語彙借用に汎時的にみられる特徴といってもよいかもしれない.

注目すべきは,借用語のソースとして,標準フランス語のみならず,フランス語の諸変種やクレオール語なども含まれていることだ.カリブ諸島,カナダ,ルイジアナ,アフリカなどのフランス語変種からの借用語が少なくない.中英語期にも,中央フランス語のみならず,とりわけ初期にノルマン・フランス語 (norman_french) からも語彙が流入していたが,近代以降「フランス語」の指す範囲が拡がるとともに,借用元変種も多様化してきたということだろう.

現代世界の借用元言語としての英語を考えてみても,従来はイギリス標準英語やアメリカ標準英語がほぼ唯一の借用元変種だったかもしれないが,現在ではピジン語やクレオール語も含めた各種の英語変種が借用元変種となっている事実がある.それと同じことが,フランス語についても言えるということなのではないか.

・ Schultz, Julia. "Twentieth-Century Borrowings from french into English --- An Overview." English Today 28.2 (2012): 3--9.

2015-10-12 Mon

■ #2359. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由 (3) [history][loan_word][lexicology][borrowing][linguistic_imperialism][language_myth][purism]

標題と関連して,「#134. 英語が民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2009-09-08-1]),「#1366. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2013-01-22-1]),「#1845. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由 (2)」 ([2014-05-16-1]) で様々な見解を紹介してきた.今回は,主として英語が歴史的に他言語から多くの語彙を借用してきた事実に照らして,英語の民主性・非民主性について考えてみたい.

英語が多くの言語からおびただしい語彙を借用してきたことは,言語的純粋主義 (purism) の立場からの批判が皆無ではないにせよ,普通は好意的に語られる.英語の語彙借用好きは,ほとんどすべての英語史記述でも強調される特徴であり,これを指して "cosmopolitan vocabulary" などと持ち上げられることが多い.続けて,英語,そして英語国民は,柔軟にして鷹揚,外に対して開かれており,多様性を重んじる伝統を有すると解釈されることが多い.歴史的に英語国では言語を統制するアカデミーが設立されにくかったこともこの肯定的な議論に一役買っているだろう.また,もう1つの国際語であるフランス語が上記の点で英語と反対の特徴を示すことからも,相対的に英語の「民主性」が浮き彫りになる.

しかし,英語の民主性に関する肯定的なイメージはそれ自体が作られたイメージであり,語彙借用のある側面を反映していないという.Bailey (91) によれば,植民地帝国主義時代の英国人は,その人種的優越感ゆえに,諸言語からの語彙をやみくもに受け入れたわけではなく,むしろすでに他のヨーロッパ人が受け入れていた語彙についてのみ自らの言語へ受け入れることを許したという.これが事実だとすれば,英語(国民)はむしろ非民主的であると言えるかもしれない.

Far from its conventional image as a language congenial to borrowing from remote languages, English displays a tendency to accept exotic loanwords mainly when they have first been adopted by other European languages or when presented with marginal social practices or trivial objects. Anglophones who have ventured abroad have done so confident of the superiority of their culture and persuaded of their capacity for adaptation, usually without accepting the obligations of adapting. Extensive linguistic borrowing and language mixing arise only when there is some degree of equality between or among languages (and their speakers) in a multilingual setting. For the English abroad, this sense of equality was rare. Whether it is a language more "friendly to change than other languages" has hardly been questioned; those who embrace the language are convinced that English is a capacious, cosmopolitan language superior to all others.

Bailey によれば,「開かれた民主的な英語」のイメージは,それ自体が植民地主義の産物であり,植民地主義時代の語彙借用の事実に反するということになる.

ただし,Bailey の植民地主義と語彙借用の議論は,主として近代以降の歴史に関する議論であり,英語が同じくらい頻繁に語彙借用を行ってきたそれ以前の時代の議論には直接触れていないことに注意すべきだろう.中英語以前は,英語はラテン語やフランス語から多くの語彙を借り入れなければならない,社会的に下位の言語だったのであり,民主的も非民主的も論ずるまでもない言語だったのだから.

・ Bailey, R. Images of English. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1991.

2015-10-10 Sat

■ #2357. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計 [oed][statistics][lexicology][loan_word][borrowing][latin][greek][french][italian][spanish][portuguese][romancisation]

標題に関する,OED2 の CD-ROM 版を用いた本格的な量的研究を発見した.Culpeper and Clapham によるもので,調査方法を見るかぎり,語源欄検索の機能を駆使し,なるべく雑音の混じらないように腐心したようだ.OED などを利用した量的研究の例は少なくないが,方法論の厳密さに鑑みて,従来の調査よりも信頼のおける結果として受け入れてよいのではないかと考える.もっとも,筆者たち自身が OED を用いて語彙統計を得ることの意義や陥穽について慎重に論じており,結果もそれに応じて慎重に解釈しなければいけないことを力説している.したがって,以下の記述も,その但し書きを十分に意識しつつ解釈されたい.

Culpeper and Clapham の扱った古典語およびロマンス諸語とは,具体的にはラテン語,ギリシア語,フランス語,イタリア語,スペイン語,ポルトガル語を中心とする言語である.数値としてある程度の大きさになるのは,最初の4言語ほどである.筆者たちは,OED 掲載の2,314,82の見出し語から,これらの言語を直近の源とする借用語を77,335語取り出した.これを時代別,言語別に整理し,タイプ数というよりも,主として当該時代に初出する全語彙におけるそれらの借用語の割合を重視して,各種の語彙統計値を算出した.

一つひとつの数値が示唆的であり,それぞれ吟味・解釈していくのもおもしろいのだが,ここでは Culpeper and Clapham (215) が論文の最後で要約している主たる発見7点を引用しよう.

(1) Latin and French have had a profound effect on the English lexicon, and Latin has had a much greater effect than French.

(2) Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese are of relatively minor importance, although Italian experienced a small boost in the 18th century.

(3) The general trend is one of decline in borrowing from Classical and Romance languages. In the 17th century, 39.3% of recorded vocabulary came from Classical and Romance languages, whereas today the figure is 15%.

(4) Latin borrowing peaked in 1600--1675, and Latin contributed approximately 7000 words to the English lexicon during the 16th century.

(5) Greek, coming after Latin and French in terms of overall quantity, peaked in the 19th century.

(6) French borrowing peaked in 1251--1375, fell below the level of Latin borrowing around 1525, and thereafter declined except for a small upturn in the 18th century. French contributed over 11000 words to the English lexicon during the Middle English period.

(7) Today, borrowing from Latin may have a slight lead on borrowing from French.

この7点だけをとっても,従来の研究では曖昧だった調査結果が,今回は数値として具体化されており,わかりやすい.(1) は,フランス語とラテン語で,どちらが量的に多くの借用語彙を英語にもたらしてきたかという問いに端的に答えるものであり,ラテン語の貢献のほうが「ずっと大きい」ことを明示している.(7) によれば,そのラテン語の優位は,若干の差ながらも,現代英語についても言えるようだ.関連して,(6) から,最大の貢献言語がフランス語からラテン語へ切り替わったのが16世紀前半であることが判明するし,(4) から,ラテン語のピークは16世紀というよりも17世紀であることがわかる.

(3) では,近代以降,新語における借用語の比率が下がってきていることが示されているが,これは「#879. Algeo の新語ソース調査から示唆される通時的傾向」([2011-09-23-1]) でみたことと符合する.(2) と (5) では,ラテン語とフランス語以外の諸言語からの影響は,全体として僅少か,あるいは特定の時代にやや顕著となったことがある程度であることもわかる.

英語史における借用語彙統計については,cat:lexicology statistics loan_word の各記事を参照されたい.本記事と関連して,特に「#2162. OED によるフランス語・ラテン語からの借用語の推移」 ([2015-03-29-1]) を参照.

・ Culpeper Jonathan and Phoebe Clapham. "The Borrowing of Classical and Romance Words into English: A Study Based on the Electronic Oxford English Dictionary." International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 1.2 (1996): 199--218.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow