2020-04-03 Fri

■ #3994. 古英語の与格形の起源 [oe][dative][germanic][indo-european][case][syncretism][instrumental][suppletion][exaptation]

昨日の記事「#3993. 印欧語では動詞カテゴリーの再編成は名詞よりも起こりやすかった」 ([2020-04-02-1]) で,古英語の名詞の与格 (dative) の起源に触れた.前代の与格,奪格,具格,位格という,緩くいえば場所に関わる4つの格が融合 (syncretism) して,新たな「与格」として生まれ変わったということだった.これについて,Lass (Old English 128--29) による解説を聞いてみよう.

The transition from late IE to PGmc involved a collapse and reformation of the case system; nominative, genitive and accusative remained more or less intact, but all the locational/movement cases merged into a single 'fourth case', which is conventionally called 'dative', but in fact often represents an IE locative or instrumental. This codes pretty much all the functions of the original dative, locative, ablative and instrumental. A few WGmc dialects do still have a distinct instrumental sg for some noun classes, e.g. OS dag-u, OHG tag-u for 'day' vs. dat sg dag-e, tag-e; OE has collapsed both into dative (along with locative, instrumental and ablative), though some traces of an instrumental remain in the pronouns . . .

格の融合の話しがややこしくなりがちなのは,融合する前に区別されていた複数の格のうちの1つの名前が選ばれて,融合後に1つとなったものに割り当てられる傾向があるからだ.古英語の場合にも,前代の与格,奪格,具格,位格が融合して1つになったというのは分かるが,なぜ新たな格は「与格」と名付けられることになったのだろうか.形態的にいえば,新たな与格形は古い与格形を部分的には受け継いでいるが,むしろ具格形の痕跡が色濃い.

具体的にいえば,与格複数の典型的な屈折語尾 -um は前代の具格複数形に由来する.与格単数については,ゲルマン諸語を眺めてみると,名詞のクラスによって起源問題は複雑な様相を呈していが,確かに前代の与格形にさかのぼるものもあれば,具格形や位格形にさかのぼるものもある.古英語の与格単数についていえば,およそ前代の与格形にさかのぼると考えてよさそうだが,それにしても起源問題は非常に込み入っている.

Lass は別の論考で新しい与格は "local" ("Data" 398) とでも呼んだほうがよいと提起しつつ,ゲルマン祖語以後の複雑な経緯をざっと説明してくれている ("Data" 399).

. . . all the dialects have generalized an old instrumental in */-m-/ for 'dative' plural (Gothic -am/-om/-im, OE -um, etc. . . ). But the 'dative' singular is a different matter: traces of dative, locative and instrumental morphology remain scattered throughout the existing materials.

要するに,古英語やゲルマン諸語の与格は,形態の出身を探るならば「寄せ集め所帯」といってもよい代物である.寄せ集め所帯ということであれば「#2600. 古英語の be 動詞の屈折」 ([2016-06-09-1]) で解説した be 動詞の状況と異ならない.be 動詞の様々な形態も,4つの異なる語根から取られたものだからだ.また,各種の補充法 (suppletion) の例も同様である.言語は pure でも purist でもない.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

・ Lass, Roger. "On Data and 'Datives': Ruthwell Cross rodi Again." Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 92 (1991): 395--403.

2020-03-25 Wed

■ #3985. 言語学でいう法 (mood) とは何ですか? (3) [mood][verb][terminology][inflection][conjugation][subjunctive][morphology][category][indo-european][sobokunagimon][latin]

2日間の記事 ([2020-03-23-1], [2020-03-24-1]) に引き続き,標題の疑問について議論します.ラテン語の文法用語 modus について調べてみると,おやと思うことがあります.OED の mode, n. の語源記事に次のような言及があります.

In grammar (see sense 2), classical Latin modus is used (by Quintilian, 1st cent. a.d.) for grammatical 'voice' (active or passive; Hellenistic Greek διάθεσις ), post-classical Latin modus (by 4th-5th-cent. grammarians) for 'mood' (Hellenistic Greek ἔγκλισις ). Compare Middle French, French mode grammatical 'mood' (feminine 1550, masculine 1611).

つまり,modus は古典時代後のラテン語でこそ現代的な「法」の意味で用いられていたものの,古典ラテン語ではむしろ別の動詞の文法カテゴリーである「態」 (voice) の意味で用いられていたということになります.文法カテゴリーを表わす用語群が混同しているかのように見えます.これはどう理解すればよいでしょうか.

実は voice という用語自体にも似たような事情がありました.「#1520. なぜ受動態の「態」が voice なのか」 ([2013-06-25-1]) で触れたように,英語において,voice は現代的な「態」の意味で用いられる以前に,別の動詞の文法カテゴリーである「人称」 (person) を表わすこともありましたし,名詞の文法カテゴリーである「格」 (case) を表わすこともありました.さらにラテン語の用語事情を見てみますと,「態」を表わした用語の1つに genus がありましたが,この語は後に gender に発展し,名詞の文法カテゴリーである「性」 (gender) を意味する語となっています.

以上から見えてくるのは,この辺りの用語群の混同は歴史的にはざらだったということです.考えてみれば,現在でも動詞や名詞の文法カテゴリーを表わす用語を列挙してみると,法 (mood),相 (aspect),態 (voice),性 (gender),格 (case) など,いずれも初見では意味が判然としませんし,なぜそのような用語(日本語でも英語でも)が割り当てられているのかも不明なものが多いことに気付きます.比較的分かりやすいのは時制 (tense),(number),人称 (person) くらいではないでしょうか.

英語の mood/mode, aspect, voice, gender, case や日本語の「法」「相」「態」「性」「格」などは,いずれも言葉(を発する際)の「方法」「側面」「種類」程度を意味する,意味的にはかなり空疎な形式名詞といってよく,kind, type, class,「種」「型」「類」などと言い換えてもよい代物です.ということは,これらはあくまで便宜的な分類名にすぎず,そこに何らかの積極的な意味が最初から読み込まれていたわけではなかったという可能性が示唆されます.

議論をまとめましょう.2日間の記事で「法」を「気分」あるいは「モード」とみる解釈を示してきました.しかし,この解釈は,用語の起源という観点からいえば必ずしも当を得ていません.mode は語源としては「方法」程度を意味する形式名詞にすぎず,当初はそこに積極的な意味はさほど含まれていなかったと考えられるからです.しかし,今述べたことはあくまで用語の起源という観点からの議論であって,後付けであるにせよ,私たちがそこに「気分」や「モード」という積極的な意味を読み込んで解釈しようとすること自体に問題があるわけではありません.実際のところ,共時的にいえば「法」=「気分」「モード」という解釈はかなり奏功しているのではないかと,私自身も思っています.

2020-03-24 Tue

■ #3984. 言語学でいう法 (mood) とは何ですか? (2) [mood][verb][terminology][inflection][conjugation][subjunctive][morphology][category][indo-european][sobokunagimon][etymology]

昨日の記事 ([2020-03-23-1]) に引き続き,言語の法 (mood) についてです.昨日の記事からは,mood と mode はいずれも「法」の意味で用いられ,法とは「気分」でも「モード」でもあるからそれも合点が行く,と考えられそうに思います.しかし,実際には,この両単語は語源が異なります.昨日「mood は mode にも通じ」るとは述べましたが,語源が同一とは言いませんでした.ここには少し事情があります.

mode から考えましょう.この単語はラテン語 modus に遡ります.ラテン語では "manner, mode, way, method; rule, rhythm, beat, measure, size; bound, limit" など様々な意味を表わしました.さらに遡れば印欧祖語 *med- (to take appropriate measures) にたどりつき,原義は「手段・方法(を講じる)」ほどだったようです.このラテン単語はその後フランス語で mode となり,それが後期中英語に mode として借用されてきました.英語では1400年頃に音楽用語として「メロディ,曲の一節」の意味で初出しますが,1450年頃には言語学の「法」の意味でも用いられ,術語として定着しました.その初例は OED によると以下の通りです.moode という綴字で用いられていることに注意してください.

mode, n.

. . . .

2.

a. Grammar. = mood n.2 1.

Now chiefly with reference to languages in which mood is not marked by the use of inflectional forms.

c1450 in D. Thomson Middle Eng. Grammatical Texts (1984) 38 A verbe..is declined wyth moode and tyme wtoute case, as 'I love the for I am loued of the' ... How many thyngys falleth to a verbe? Seuene, videlicet moode, coniugacion, gendyr, noumbre, figure, tyme, and person. How many moodes bu ther? V... Indicatyf, imperatyf, optatyf, coniunctyf, and infinityf.

次に mood の語源をひもといてみましょう.現在「気分,ムード」を意味するこの英単語は借用語ではなく古英語本来語です.古英語 mōd (心,精神,気分,ムード)は当時の頻出語といってよく,「#1148. 古英語の豊かな語形成力」 ([2012-06-18-1]) でみたように数々の複合語や派生語の構成要素として用いられていました.さらに遡れば印欧祖語 *mē- (certain qualities of mind) にたどりつき,先の mode とは起源を異にしていることが分かると思います.

さて,この mood が英語で「法」の意味で用いられたのは,OED によれば1450年頃のことで,以下の通りです.

mood, n.2

. . . .

1. Grammar.

a. A form or set of forms of a verb in an inflected language, serving to indicate whether the verb expresses fact, command, wish, conditionality, etc.; the quality of a verb as represented or distinguished by a particular mood. Cf. aspect n. 9b, tense n. 2a.

The principal moods are known as indicative (expressing fact), imperative (command), interrogative (question), optative (wish), and subjunctive (conditionality).

c1450 in D. Thomson Middle Eng. Grammatical Texts (1984) 38 A verbe..is declined wyth moode and tyme wtoute case.

気づいたでしょうか,c1450の初出の例文が,先に挙げた mode のものと同一です.つまり,ラテン語由来の mode と英語本来語の mood が,形態上の類似(引用中の綴字 moode が象徴的)によって,文法用語として英語で使われ出したこのタイミングで,ごちゃ混ぜになってしまったようなのです.OED は実のところ「心」の mood, n.1 と「法」の mood, n.2 を別見出しとして立てているのですが,後者の語源解説に "Originally a variant of mode n., perhaps reinforced by association with mood n.1." とあるように,結局はごちゃ混ぜと解釈しています.意味的には「気分」「モード」辺りを接点として,両単語が結びついたと考えられます.したがって,「法」を「気分」「モード」と解釈する見方は,ある種の語源的混同が関与しているものの,一応のところ1450年頃以来の歴史があるわけです.由緒が正しいともいえるし,正しくないともいえる微妙な事情ですね.昨日の記事で「法」を「気分」あるいは「モード」とみる解釈が「なかなかうまくできてはいるものの,実は取って付けたような解釈だ」と述べたのは,このような背景があったからです.

では,標題の疑問に対する本当の答えは何なのでしょうか.大本に戻って,ラテン語で文法用語としての modus がどのような意味合いで使われていたのかが分かれば,「法」 (mood, mode) の真の理解につながりそうです.それは明日の記事で.

2020-03-23 Mon

■ #3983. 言語学でいう法 (mood) とは何ですか? (1) [mood][verb][terminology][inflection][conjugation][subjunctive][morphology][category][indo-european][sobokunagimon]

印欧語言語学では「法」 (mood) と呼ばれる動詞の文法カテゴリー (category) が重要な話題となります.その他の動詞の文法カテゴリーとしては時制 (tense),相 (aspect),態 (voice) がありますし,統語的に関係するところでは名詞句の文法カテゴリーである数 (number) や人称 (person) もあります.これら種々のカテゴリーが協働して,動詞の形態が定まるというのが印欧諸語の特徴です.この作用は,動詞の活用 (conjugation),あるいはより一般的には動詞の屈折 (inflection) と呼ばれています.

印欧祖語の法としては,「#3331. 印欧祖語からゲルマン祖語への動詞の文法範疇の再編成」 ([2018-06-10-1]) でみたように直説法 (indicative mood),接続法 (subjunctive mood),命令法 (imperative mood),祈願法 (optative mood) の4種が区別されていました.しかし,ずっと後の北西ゲルマン語派では最初の3種に縮減し,さらに古英語までには最初の2種へと集約されていました(現代における命令法の扱いについては「#3620. 「命令法」を認めず「原形の命令用法」とすればよい? (1)」 ([2019-03-26-1]),「#3621. 「命令法」を認めず「原形の命令用法」とすればよい? (2)」 ([2019-03-27-1]) を参照).さらに,古英語以降,接続法は衰退の一途を辿り,現代までに非現実的な仮定を表わす特定の表現を除いてはあまり用いられなくなってきました.そのような事情から,現代の英文法では歴史的な「接続法」という呼び方を続けるよりも,「仮定法」と称するのが一般的となっています(あるいは「叙想法」という呼び名を好む文法家もいます).

さて,現代英語の法としては,直説法 (indicative mood) と仮定法 (subjunctive mood) の2種の区別がみられることになりますが,この対立の本質は何でしょうか.一般には,機能的にデフォルトの直説法に対して,仮定法は話者の命題に対する何らかの心的態度がコード化されたものだといわれます.何らかの心的態度というのも曖昧な言い方ですが,先に触れた例でいうならば「非現実的な仮定」が典型です.If I were a bird, I would fly to you. における仮定法過去形の were は,話者が「私は鳥である」という非現実的な仮定の心的態度に入っていることを示します.言ってみれば,妄想ワールドに入っていることの標識です.

同様に,仮定法現在形 go を用いた I suggest that she go alone. という文においても,話者の頭のなかで希望として描いているにすぎない「彼女が一人でいく」という命題,まだ起こっていないし,これからも確実に起こるかどうかわからない命題であることが,その動詞形態によって示されています.先の例ほどインパクトは強くないものの,これも一種の妄想ワールドの標識です.

「法」という用語も「心的態度」という説明も何とも思わせぶりな表現ですが,英語としては mood ですから,話者の「気分」であるととらえるのもある程度は有効な解釈です.つまり,法とは話者がある命題をどのような「気分」で述べているのか(たいていは「妄想的な気分」)を標示するものである,という見方です.あるいは mood は mode 「モード,様態」にも通じ,実際に両単語とも言語学用語としての法の意味で用いられますので,話者の「モード」と言い換えてもよさそうです.仮定法は,妄想モードを標示するものということです.

法については上記のような「気分」あるいは「モード」という解釈で大きく間違いはないと思います.ただし,この解釈は,用語の歴史を振り返ってみると,なかなかうまくできてはいるものの,実は取って付けたような解釈だということも分かってきます.それについては明日の記事で.

2020-02-11 Tue

■ #3942. 印欧祖語からゲルマン祖語への主要な母音変化 [vowel][indo-european][germanic][sound_change][centralisation]

標題は,印欧祖語の形態から英単語の語源を導こうとする上で重要な知識である.上級者は,語源辞書や OED の語源欄を読む上で,これを知っているだけでも有用.Minkova (68--69) より.

| a | ──┐ | PIE *al- 'grow', Lat. aliment, Gmc *alda 'old' | |

| ├── | a | ||

| o | ──┘ | PIE *ghos-ti- 'guest', Lat. hostis, Goth. gasts | |

| ā | ──┐ | PIE *māter, Lat. māter, OE mōder 'mother' | |

| ├── | ō | ||

| ō | ──┘ | PIE *plōrare 'weep', OE flōd 'flood' | |

| i | ──┐ | PIE *tit/kit 'tickle', Lat. titillate, ME kittle | |

| ├── | i | ||

| e | ──┘ | Lat. ventus, OE wind 'wind', Lat. sedeo, Gmc *sitjan 'sit' |

たとえば,印欧祖語で *māter "mother" は ā の長母音をもっていたが,これがゲルマン祖語までに ō に化けていることに注意.実際,古英語でも mōdor として現われている.この長母音が後に o へと短化し,さらに一段上がって u となり,最終的に中舌化するに至って現代の /ʌ/ にたどりついた.英語の母音は,5,6千年の昔から,概ね規則正しく変化し続けて現行のものになっているのである.

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2020-01-29 Wed

■ #3929. なぜギリシアとローマは続け書きを採用したか? (1) [alphabet][distinctiones][punctuation][reading][writing][latin][greek][indo-european][word]

アルファベットの分かち書き (distinctiones) と続け書き (scriptura continua) の問題については,最近では「#3926. 分かち書き,表語性,黙読習慣」 ([2020-01-26-1]) で,それ以前にも distinctiones の各記事で取り上げてきた.

Saenger (9) によると,アルファベットに母音表記の慣習が持ち込まれる以前の地中海世界では,スペースによるか点によるかの違いこそあれ,分かち書きが普通に行なわれていた.ところが,ギリシア語において母音表記が可能となるに及び,続け書きが生まれたという.これを時系列で整理すると次のようになる.

まず,アルファベット使用の初期から分かち書きは普通にあった.ところが,ギリシア・ローマ時代にそれが廃用となり,代わって続け書きが一般化した.ローマ帝国が崩壊し,中世後期の8世紀頃になると分かち書きが改めて導入され,その後徐々に一般化して現代に至る.

分かち書きは現在では当然視されているが,母音表記を享受し始めた古典時代の間に,その慣習が一度廃れた経緯があるということだ.では,なぜ母音表記の導入により,私たちにとって明らかに便利に思われる分かち書きが廃用となり,むしろ読みにくいと思われる続け書きが発達したのだろうか.Saenger (9--10) によれば,母音表記と続け書きの間には密接な関係があるという.

The uninterrupted writing of ancient scriptura continua was possible only in the context of a writing system that had a complete set of signs for the unambiguous transcription of pronounced speech. This occurred for the first time in Indo-European languages when the Greeks adapted the Phoenician alphabet by adding symbols for vowels. The Greco-Latin alphabetical scripts, which employed vowels with varying degrees of modification, were used for the transcription of the old forms of the Romance, Germanic, Slavic, and Hindu tongues, all members of the Indo-European language group, in which words were polysyllabic and inflected. For an oral reading of these Indo-European languages, the reader's immediate identification of words was not essential, but a reasonably swift identification and parsing of syllables was fundamental. Vowels as necessary and sufficient codes for sounds permitted the reader to identify syllables swiftly within rows of uninterrupted letters. Before the introduction of vowels to the Phoenician alphabet, all the ancient languages of the Mediterranean world---syllabic or alphabetical, Semitic or Indo-European---were written with word separation by either space, points, or both in conjunction. After the introduction of vowels, word separation was no longer necessary to eliminate an unacceptable level of ambiguity.

Throughout the antique Mediterranean world, the adoption of vowels and of scriptura continua went hand in hand. The ancient writings of Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, and Israel did not employ vowels, so separation between words was retained. Had the space between words been deleted and the signs been written in scriptura continua, the resulting visual presentation of the text would have been analogous to a modern lexogrammatic puzzle. Such written languages might have been decipherable, given their clearly defined conventions for word order and contextual clues, but only after protracted cognitive activity that would have made fluent reading as we know it impractical. While the very earliest Greek inscriptions were written with separation by interpuncts, points placed at midlevel between words, Greece soon thereafter became the first ancient civilization to employ scriptura continua. The Romans, who borrowed their letter forms and vowels from the Greeks, maintained the earlier Mediterranean tradition of separating words by points far longer than the Greeks, but they, too, after a scantily documented period of six centuries, discarded word separation as superfluous and substituted scriptura continua for interpunct-separated script in the second century A.D.

ここで展開されている議論について,私はよく理解できていない.母音表記の導入の結果,音節が同定しやすくなったという理屈がよくわからない.また,仮にそれが本当だったとして,文字の読み手が従来の分かち書きではなく続け書きにシフトしたとしても何とか解読できる,という点までは理解できるが,なぜ続け書きに積極的にシフトしたのかは不明である.上の議論は,消極的な説明づけにすぎないように思われる.

母音文字を発明してアルファベットを便利にしたギリシア人が,読みにくい続け書きにシフトしたというのは,何か矛盾しているように感じられる.実際,この問題は多くの論者を悩ませ続けてきたようだ (Saenger 10)

ギリシア人による母音文字の導入という文字史上の画期的な出来事については,「#423. アルファベットの歴史」 ([2010-06-24-1]) や「#2092. アルファベットは母音を直接表わすのが苦手」 ([2015-01-18-1]) を参照.

・ Saenger, P. Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 1997.

2020-01-19 Sun

■ #3919. Chibanian (チバニアン,千葉時代)の接尾辞 -ian (2) [suffix][word_formation][adjective][participle][indo-european][etymology]

昨日の記事 ([2020-01-18-1]) に引き続き,話題の Chibanian の接尾辞 -ian について.この英語の接尾辞は,ラテン語で形容詞を作る接尾辞 -(i)ānus にさかのぼることを説明したが,さらに印欧祖語までさかのぼると *-no- という接尾辞に行き着く.語幹母音に *-ā- が含まれるものに後続すると,*-āno- となり,これ全体が新たな接尾辞として切り出されたということだ.ここから派生した -ian, -an, -ean が各々英語に取り込まれ,生産的な語形成を展開してきたことは,昨日挙げた多くの例で示される通りである.

さて,印欧祖語の *-no- は,ゲルマン語派のルートを通じて,英語の意外な部分に受け継がれてきた.強変化動詞の過去分詞形に現われる -en と素材を表わす名詞に付されて形容詞を作る -en である.前者は broken, driven, shown, taken, written などの -en を指し,後者は brazen, earthen, golden, wheaten, wooden, woolen などの -en を指す (cf. 後者について「#1471. golden を生み出した音韻・形態変化」 ([2013-05-07-1]) も参照).いずれも形容詞以外から形容詞を作るという点で共通の機能を果たしている.

つまり,Chibanian の -ian と golden の -en は,現代英語に至るまでの経路は各々まったく異なるものの,さかのぼってみれば同一ということになる.

2019-10-28 Mon

■ #3836. フランス語史の年表 [timeline][hfl][french][anthropology][indo-european][hfl]

フランス語史は専門ではないものの,英語史を掘り下げて理解するためには是非ともフランス語史の知識がほしい.ということで,少なからぬ関心を寄せている.今回は Perret (179--81) よりフランス語史の年表 "Chronologie" を掲げよう.イタリックの行は,仮説的な年代・記述という意味である.

[ Préhistoire des langues du monde ]

Il y a 4 ou 5 millions d'années: apparition de l'australopithèque en Afrique.

Il y a 1,6 million d'années: homo erectus colonise l'Eurpope et l'Asie.

Il y a 850 000 ans: premiers hominidés en Europe.

Avant - 100 000: Homo sapiens en Europe (Neandertal) et en Asie (Solo).

- 100 000: un petit groupd d'Homo sapiens vivant en Afrique (ou au Moyen-Orient) se met en marche et recolonise la planète. Les autres Homo sapiens se seraient éteints. (Hypothèse de certains généticiens, les équipes de Cavalli-Sforza et de Langaney, dite thèse du «goulot d'étranglement»).

- 40 000: première apparition du langage?

[ Préhistoire des Indo-Européens ]

- 10000: civilisation magdalénienne en Dordogne. Premier homme en Amérique.

- 7000: les premières langues indo-européennes naissent en Anatolie (hypothèse Renfrew).

Entre - 65000 et - 5500: les Indo-Européens commencent leur migration par vagues (hypothèse Renfrew).

- 4500: les Indo-Européens occupent l'ouest de l'Europe (hypothèse Renfrew).

- 4000 ou - 3000: les Indo-Européens commencent à se disperser (hypothèse dominante).

- 3500: civilisation dite des Kourganes (tumuluss funéraires), débuts de son expansion.

- 3000: écriture cunéiforme en Perse, écriture en Inde. Première domestication du cheval en Russie? (- 2000, premières représentations de cavaliers).

[ Préhistoire du français ]

- 4000 ou - 3000: la civilisation des constructeurs de mégalithes apparaît en Bretagne.

- 3000: la présence des Celtes est attestée en Bohème et Bavière.

- 2500: début de l'emploi du bronze.

- 600: premiers témoignages sur les Ligure et les Ibères.

- 600: des marins phocéens s'installent sur la cõte méditerranéenne.

- 500: une invasion celte (précédée d'infiltrations?): les Gaulois.

[ Histoire du français ]

- 1500: conquête de la Provence par les Romains et infiltrations dans la région narbonnaise.

- 59 à - 51: conquête de la Gaule par les Romains.

212: édit de Caracalla accordant la citoyenneté à tous les hommes libres de l'Empire.

257: incursions d'Alamans et de Francs jusqu'en Italie et Espagne.

275: invasion générale de la Gaule par les Germains.

312: Constantin fait du christianisme la religion officielle de l'Empire.

Vers 400: traduction en latin de la Bible (la Vulgate) par saint Jérôme.

450--650: émigration celte en Bretagne (à partir de Grande-Bretagne): réimplantation du celte en Bretagne.

476: prise de Rome et destitution de l'empereur d'Occident.

486--534: les Francs occupent la totalité du territoire de la Galue (496, Clovis adopted le christianisme).

750--780: le latin cesse d'être compris par les auditoires populaires dans le nord du pays.

800: sacre de Charlemagne.

813: concile de Tours: les sermons doivent être faits dans les langues vernaculaires.

814: mort de Charlemagne.

842: les Serments de Strasbourg, premier document officiel en proto-français.

800 à 900: incursions des Vikings.

800--850: on cesse de comprendre le latin en pays de langues d'oc.

880: Cantilène de sainte Eulalie, première elaboration littéraire en proto-français.

911: les Vikings sédentarisés en Normandie.

957: Hugues Capet, premier roi de France à ignorer le germanique.

1063: conquête de l'Italie du Sud et de la Sicile par des Normands.

1066: bataille de Hastings: une dynastie normande s'installe en Angleterre où on parlera français jusqu'à la guerre de Cent Ans.

1086: la Chanson de Roland.

1099: prise de Jérusalem par les croisés: début d'une présence du français et du provençal en Moyen-Orient.

1252: fondation de la Sorbonne (enseignement en latin).

1254: dernière croisade.

1260: Brunetto Latini, florentin, compose son Trésor en français.

1265: Charles d'Anjou se fait couronner roi des deux Siciles, on parlera français à la cour de Naples jusqu'au XIVe siècle.

1271: réunion du Comté de Toulouse, de langue d'oc, au royaume de France.

1476--1482: Louis XI rattache la Bourgogne, la Picardie, l'Artois, le Maine, l'Anjou et la Provence au royaume de France.

1477: l'imprimerie. Accélération de la standardisation et de l'oficialisation du français, premières «inventions» orthographiques.

1515: le Consistori del Gai Saber devient Collège de rhétorique: fin de la littérature officielle de langue d'oc.

1523--1541: instauration du français dans le culte protestant.

1529: fondation du Collège de France (rares enseignements en fançais).

1530: Esclarcissment de la langue française, de Palsgrave, la plus connue des grammaires du français qui parassient à l'époque en Angleterre.

1534: Jacques Cartier prent possession du Canada au nom du roi de France.

1539: ordonnace de Villers-Cotterêts, le français devient langue officielle.

1552: la Bretagne est rattachée au royaume de France.

1559: la Lorraine est rattachée au royaume de France.

1600: la Cour quitte les bords de Loire pour Parsi.

1635: Richelieu officialise l'Académie française.

1637: Descartes écrit en français Le Discours de la méthode.

1647: Remarques sur la langue française de Vaugelas: la norme de la Cour prise comme modèle du bon usage.

1660: Grammaire raisonnée de Port-Royal.

1680: première traduction catholique de la Bible en français.

1685: révocation de l'édit de Nantes: un million de protestants quittent la France pour les pays protestants d'Europe, mais aussi pour l'Afrique et l'Amérique.

1694: première parution du Dictionnaire de l'Académie.

1700: début d'un véritable enseignement élémentaire sans latin, avec les frères des écoles chrétiennes de Jean-Baptiste de la Salle.

1714: traité de Rastadt, le français se substitue au latin comme languge de la diplomatie en Europe.

1730: traité d'Utrecht: la France perd l'Acadie.

1739: mise en place d'un enseignment entièrement en français dans le collège de Sorèze (Tarn).

1757: apparition des premiers textes en créole.

1762: explusion des jésuites, fervents partisans dans leur collèges de l'enseignement entièrement en latin; une réorganisation des collèges fait plus de place au français.

1763: traité de Paris, la France perd son empire colonial: le Canada, les Indes, cinq îles des Antilles, le Sénégal et la Lousinane.

1783: la France recouvre le Sénégal, la Lousiane et trois Antilles.

1787: W. Jones reconnaît l'existence d'une famille de langues regroupant latin, grec, persan, langues germaniques, langues celte et sanscrit.

1794: rapport Barrère sur les idiomes suspect (8 pluviôse an II); rapport Grégoire sur l'utilité de détruire les patois (16 prairial an II).

1794--1795: la Républic s'aliène les sympathies par des lois interdisant l'usage de toute autre langue que le français dans les pays occupée.

1797: tentative d'introduire le français dans le culte (abbé Grégoire).

1803: Bonaparte vend la Louisiane aux Anglais.

1817: la France administre le Sénégal.

1827: Préface de Cromwell, V. Hugo, revendication de tous les registres lexicaux pour la langue littéraire.

1830: début de la conquête de l'Algérie.

1835: la sixième édition du Dictionnaire de l'Académie accepte enfin la graphie -ais, -ait pour les imparfiat.

1879: invention du phonographe.

1881: Camille Sée crée un enseignment public à l'usage des jeunes fille.

1882: lois Jules Ferry: enseignement primaire obligatoire, laïquie et gratuie (en français).

1885: l'administration du Congo (dit ensuite de Belge) est confiée au roi des Belges.

1901: arrêté proposant une certaine tolérance dans les règles orthographiques du français.

1902: l'enseignement secondaire moderne sans latin ni grec est reconnu comme égal à la filière classique.

1902--1907: publication de l'Atlas linguistique de la France par régions de Gilliéron et Edmont.

1950: autorisation de soutenir des thèses en français.

1919: traité de Versalles, le français perd son statue de langue unique de la diplomatic en Europe.

1921: début de la diffusion de la radio.

1935: invention de la télévision.

1951: loi Deixiome permet l'enseignement de certaines langues régionales dans le second cycle.

1954--1962: les anciennes colonies de la France deviennent des états indépendents.

1962--1965: concile de Vatican II: la célébration do la messe, principal office du culte catholique, ne se fait plus en latin.

1987: un créole devient langue officielle en Haïti.

1990: un «rapport sur les rectifications de l'orthographe» propose la régularisation des pluriels de mots composés et la suppression de l'accent circonflexe.

1994: première création d'un organism de soutien à la francophonie.

・ Perret, Michèle. Introduction à l'histoire de la langue française. 3rd ed. Paris: Colin, 2008.

2019-07-29 Mon

■ #3745. 頭子音 s が出没する印欧語根 [indo-european][reconstruction][consonant][terminology][syllable]

印欧祖語の語根には,あるときには頭子音として s が現われ,別ときには現われないという種類の語根がある.s の出没のパターンが予測できないために "s mobile root" と呼ばれる.印欧語根辞典などでは *(s)ker-, *(s)pek-, *(s)tenə- のように,s がカッコにくくられていることが多い.

例として *(s)teg- (to cover) を挙げよう.ギリシア語の反映形 stégō (I cover) では s が現われているが,同根にさかのぼるラテン語 toga (トーガ《古代ローマ市民の外衣》)では s がない.英語への借用語で考えてみれば,ギリシア語からの stegosaur (剣竜,ステゴサウルス)では s が見えるが,ラテン語からの派生語群 detect, protect, tectorial, tegument, tile では s が見えない.ゲルマン単語としては thatch や deck も同根にさかのぼるが,s が現われない.

一見すると各言語において印欧祖語 *s に関する音韻的振る舞いが異なっていたようにもみえるが,実際のところ1つの言語の内部を眺めてみても s の揺れは観察され,予測できないかたちで単語ごとに s の有無がきまっているようだ.したがって,印欧語根そのものにカッコ付きで s を示す慣習となっている.

s で始まる頭子音群の振る舞いは,この印欧祖語における問題とは別に,英語音韻史においても問題が多い.関連して「#2080. /sp/, /st/, /sk/ 子音群の特異性」 ([2015-01-06-1]),「#2676. 古英詩の頭韻」 ([2016-08-24-1]) も参照されたい.

2019-07-22 Mon

■ #3738. 印欧祖語の5つの階梯 --- *sed- の場合 [indo-european][reconstruction][gradation][vowel][terminology]

印欧祖語の語幹の母音には,デフォルトで *e が想定されている.音韻形態上,これが様々な母音に化けていくことになるのだが,印欧語比較言語学においてこのデフォルトの *e は "e-grade" あるいは "full grade" (完全階梯)と呼ばれている.この *e は,必ずしも合理的に説明されない事情により口舌母音の *o に化けることがある.これを "o-grade" (o 階梯)と呼ぶ.*e なり *o なりは,それぞれ長母音化することもあり,それぞれ "lengthened e-grade" (e 延長階梯), "lengthened o-grade" (o 延長階梯)と呼ばれる.さらに,*e の母音の実現されない "zero-grade" (ゼロ階梯)というものもあった.

結果として,印欧語幹には典型的に5つの母音階梯が存在し得ることになる.この変異する母音階梯のことを,印欧語比較言語学では gradation, ablaut, apophony などと呼んでいる.どの母音になればどのような意味・機能になるといった明確な対応はなく,事実上,形式的な変異ととらえるよりほかない.

印欧祖語で「座る」 (to sit) を意味した *sed- に関して,各階梯を体現する語形と,それが派生言語においてどのように実現されているかを示す実例を示そう (Fortson 73) .

| e-grade (full grade) | *sed- | Lat. sed-ēre 'to sit', Gk. héd-ra, Eng. sit (i from earlier *e) |

| o-grade | *sod- | Eng. sat (a from earlier *o) |

| zero-grade | *sd- | *ni-sd-o- 'where [the bird] sits down = nest' > Eng. nest |

| lengthened e-grade | *sēd- | Lat. sēdēs 'seat', Eng. seat |

| lengthened o-grade | *sōd- | OE sōt > Eng. soot (*'accumulated stuff that sits on surfaces') |

不規則動詞(歴史的な強変化動詞)の母音変異も,動詞と名詞など品詞違いの語形にみられる母音交替の関係も,いずれも印欧祖語の「階梯」差にさかのぼる.非常に重要な音韻形態的現象である.

・ Fortson IV, Benjamin W. "An Approach to Semantic Change." Chapter 21 of The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Ed. Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Blackwell, 2003. 648--66.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2019-07-21 Sun

■ #3737. 「今日の不規則は昨日の規則」 --- 歴史形態論の原則 [morphology][language_change][reconstruction][comparative_linguistics][indo-european][sobokunagimon][3ps][plural][conjugation]

標題は,英語の歴史形態論においても基本的な考え方である.現代英語で「不規則」と称される形態的な現象の多くは,かつては「規則」の1種だったということである.しばしば逆もまた真なりで,「今日の規則は昨日の不規則」ということも多い.規則 (regular) か不規則 (irregular) かという問題は,共時的には互いの分布により明らかに区別できることが多いので絶対的とはいえるが,歴史的にいえばポジションが入れ替わることも多いという点で相対的な区別である.

この原則を裏から述べているのが,次の Fortson (69--70) の引用である.比較言語学 (comparative_linguistics) の再建 (reconstruction) の手法との関連で,教訓的な謂いとなっている.

A guiding principle in historical morphology is that one should reconstruct morphology based on the irregular and exceptional forms, for these are most likely to be archaic and to preserve older patterns. Regular or predictable forms (like the Eng. 3rd singular present takes or the past tense thawed) are generated using the productive morphological rules of the language, and have no claim to being old; but irregular forms (like Eng. is, sang) must be memorized, generation after generation, and have a much greater chance of harking back to an earlier stage of a language's history. (The forms is and sang, in fact, directly continue forms in PIE itself.

英語において不規則な現象を認識したら「かつてはむしろ規則的だったのかもしれない」と問うてみるとよい.たいてい歴史的にはその通りである.逆に,普段は何の疑問も湧かない規則的な現象に思いを馳せてみてほしい.場合によっては,それはかつての不規則な現象が,どういうわけか歴史の過程で一般化し,広く受け入れられるようになっただけかもしれないと.ここに歴史言語学的発想の極意がある.もちろん,この原則は英語にも,日本語にも,他のどの言語にもよく当てはまる.

「今日の不規則は昨日の規則」の例は,枚挙にいとまがない.上でも触れた例について,英語の歴史から次の話題を参照.

・ 「不規則」な名詞の複数形 (ex. feet, geese, lice, men, mice, teeth, women) (cf. 「#3638.『英語教育』の連載第2回「なぜ不規則な複数形があるのか」」 ([2019-04-13-1]))

・ 「不規則」な動詞の活用 (ex. sing -- sang -- sung) (cf. 「#3670.『英語教育』の連載第3回「なぜ不規則な動詞活用があるのか」」 ([2019-05-15-1]))

・ 3単現の -s (cf. 英語史連載第2回「なぜ3単現に -s を付けるのか?」)

・ Fortson IV, Benjamin W. "An Approach to Semantic Change." Chapter 21 of The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Ed. Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Blackwell, 2003. 648--66.

2019-07-20 Sat

■ #3736. Yamna culture --- 印欧祖語の担い手の有力候補 [indo-european][map]

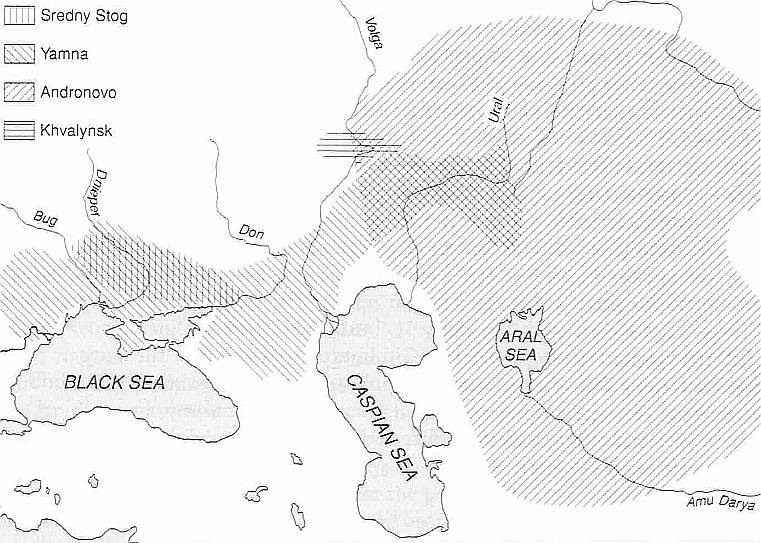

昨日の記事「#3735. 印欧語族諸族の大移動」 ([2019-07-19-1]) で,印欧祖語の分化の年代としておよそ紀元前3300年が提案されていることをみた.「#637. クルガン文化と印欧祖語」 ([2011-01-24-1]) で紹介した Gimbutas の有力な説によると,印欧祖語の話者はクルガン文化の担い手と同一の集団ではないかとされる.

しかし,考古学的な観点からもっと精密にみると,後期新石器時代から金石併用時代にかけて黒海およびカスピ海の北部ステップ地帯 (Pontic-Caspian steppes) で生活を営んでいた人々の存在が浮かび上がってくる.とりわけ紀元前3500年頃にはこの地域に "Yamna(ya) culture" という文化が栄えており,乗馬が行なわれていた可能性もあったという.また,Yamna は,後に分化していくインド=イラン語派と関連づけられる,東方に位置する "Andronovo culture" とも考古学的な関係が近いという.とすると,Yamna の担い手は,インド=イラン人の原型,あるいはインド=ヨーロッパ人そのものであるという可能性が開けてくる.年代的にも大きな齟齬はない.

一方,Yamna 自身は,部分的に黒海北部に展開していた "Sredny Stog culture" (紀元前4500--3500)や,その東に位置する "Khvalynsk culture" から発展したものともされ,Khvalynsk こそが真の印欧祖語の故地であるとする見方もある.

以上,Fortson (41--43) の記述に拠った.参考までに,Fortson (42) の地図を掲載しておく.

・ Fortson IV, Benjamin W. "An Approach to Semantic Change." Chapter 21 of The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Ed. Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Blackwell, 2003. 648--66.

2019-07-19 Fri

■ #3735. 印欧語族諸族の大移動 [indo-european][map][archaeology][comparative_linguistics]

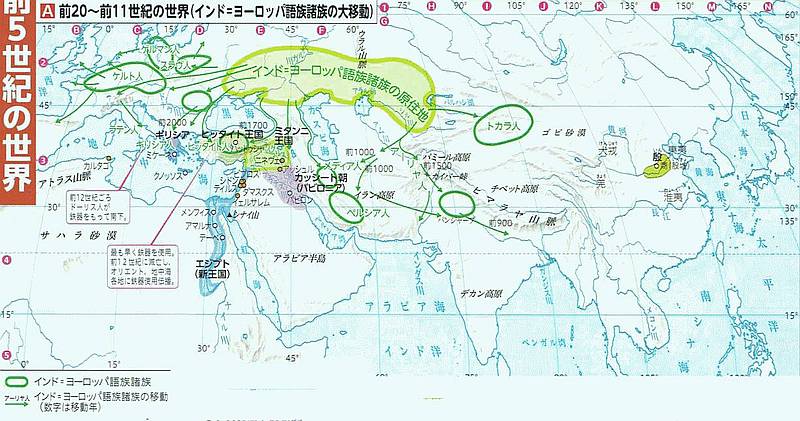

おそらく紀元前3300年以降のある段階で,ウクライナやカザフスタンのステップ地帯に住まっていた印欧祖語の話し手たちの一部が,その故地を離れ,ユーラシア大陸の広い領域へと移動を開始した.彼らは数千年の時間をかけて,東方へは現在の中国の新疆ウイグル自治区まで,南方へはイランやインドまで,西方へはヨーロッパ,そして北大西洋の島まで,広く散っていくことになった.動きがとりわけ活発化したのは紀元前2千年紀のことと考えられ,以降,歴史的に同定される諸民族や諸国家の名前がユーラシア大陸のあちらこちらで確認されるようになる.トカラ人,アーリア人,ペルシア人,メディア人,ミタンニ王国,ヒッタイト王国,ギリシア人,ケルト人,ゲルマン人,スラヴ人等々.

『最新世界史図説 タペストリー』の p.4 より「前20?前11世紀の世界(インド=ヨーロッパ語族諸族の大移動)」と題する地図が,とても分かりやすい(関連して「#637. クルガン文化と印欧祖語」 ([2011-01-24-1]) の地図も参照).

上で挙げた紀元前3300年という大移動開始に関係する年代は,印欧祖語に再建される農業や牧畜に関する語彙と,そのような産業の考古学的な証拠とのすり合わせから,およそはじき出される年代である.とりわけ重要なキーワードは「車輪」である.というのは,こちらのスライドや「#166. cyclone とグリムの法則」 ([2009-10-10-1]),「#1217. wheel と reduplication」 ([2012-08-26-1]) でみたように「車輪」を表わす印欧祖語が確かに再建されており,また車輪そのものの出現が考古学的に紀元前4千年紀の後期とされていることから,印欧祖語の分化の上限が決定されるからだ.Fortson (38) がこう述べている.

Based on the available archaeological evidence, the addition of wheeled vehicles to this picture allows us to narrow the range to the mid- or late forth millennium: the earliest wheeled vehicles yet found are from c. 3300--3200 BC. If one adds a century or two on that figure (on the assumption that the actual invention of wheeled vehicles predates the earliest extant remains), that means the latest stage of common PIE (the state directly reachable by reconstruction and before any of the future branches separated) cannot have been earlier than around 3400 BC.

比較言語学と考古学のコラボにより,太古の昔の言語分化と民族大移動の年代が明らかにされ得るというエキサイティングな話題である.

・ 川北 稔・桃木 至朗(監修) 帝国書院編集部(編) 『最新世界史図説 タペストリー』16訂版,帝国書院,2018年.

・ Fortson IV, Benjamin W. Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004.

2019-07-15 Mon

■ #3731. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第1回「インドヨーロッパ祖語の故郷」を終えました [asacul][notice][slide][indo-european][link]

「#3687. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」が始まります」 ([2019-06-01-1]) で紹介しましたが,一昨日の7月13日(土),朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にて,講座「英語の歴史と語源」の初回「インドヨーロッパ祖語の故郷」が開講されました.これまでの講座では受講者は多くて10数名というところでしたが,今回は予想外に大勢の(30名を越える)受講者の方々に参加いただきました.おかげさまで後半には多くの質問やコメントも出て,活発な会となりました.ありがとうございます.英語史のおもしろさを伝えるためのシリーズですので,初回として関心をもってもらえたならば幸いです. *

初回はインド=ヨーロッパ語族の話しが中心でしたが,同語族のなかでの英語の位置づけを確認し,英語のなかに印欧祖語の遺産を多く見出すことができたかと思います.講座で使用したスライド資料をこちらに置いておきますので,復習等にご活用ください.

1. 英語の歴史と語源・1 「インドヨーロッパ祖語の故郷」

2. シリーズ「英語の歴史と語源」の趣旨

3. 第1回 インドヨーロッパ祖語の故郷

4. 要点

5. 目次

6. 1. インド=ヨーロッパ語としての英語

7. 印欧祖語の故郷

8. 印欧語族の系統図

9. 語派の分布図

10. 印欧語族の10語派

11. ゲルマン語派の系統図と分布図

12. 2. 印欧語比較言語学

13. 再建 (reconstruction)

14. 再建の例 (1): *ped- "foot"

15. 再建の例 (2): *snusós "daughter-in-law"

16. 比較言語学の精密さ

17. 印欧祖語のその他の特徴

18. 3. 英語にみられる印欧祖語の遺産

19. ゲルマン祖語までにしか遡れない単語

20. 車輪クルクル,回るサイクル

21. 車輪 (wheel) があれば荷車 (wagon) もあった

22. guest と host

23. 4. サラダボウルな英語語彙

24. 英語語彙の規模と種類の豊富さ

25. 英語語彙にまつわる数値

26. 英語と周辺の印欧諸語の関係

27. 英語語彙の3層構造

28. (参考)日本語語彙の3層構造

29. 日英語彙史比較

30. まとめ

31. シリーズの今後

32. 推薦図書

33. 参考文献(辞典類)

34. 参考文献(その他)

2019-06-25 Tue

■ #3711. 印欧祖語とゲルマン祖語にさかのぼる基本英単語のサンプル [indo-european][germanic][lexicology][etymology]

『英語語源辞典』によると,印欧語比較言語学の成果により,1,000から2,000ほどの印欧語根が想定されている.そのおよそ半数が現代英語の語彙にも反映されているといわれるが,主に基本語彙として受け継がれているものを列挙しよう(寺澤,p. 1656;カッコは借用語を表わす).

| 身体 | arm, brow, ear, eye, foot, heart, knee, lip, nail, navel, tooth |

| 家族 | father, mother, brother, sister, son, daughter, nephew, widow |

| ?????? | beaver, cow, ewe, goat, goose, hare, hart, hound, mouse, sow, wolf; bee, wasp; louse, nit; crane, ern(e), raven, starling; fish, (lax) |

| 罎???? | alder, ash, asp(en), beech, birch, fir, hazel, tree, withy |

| 飲食物 | bean, mead, salt, water, (wine) |

| 天体・自然現象 | moon, star, sun; snow |

| 数詞 | one, two, ..., ten, hundred |

| 代名詞 | I, me, thou, ye, it, that, who, what |

| 動詞 | be, bear, come, do, eat, know, lie, murmur, ride, seek, sew, sing, stand, weave |

| 形容詞 | full, light, middle, naked, new, sweet, young |

| その他 | acre, ax(e), furrow, month, name, night, summer, wheel, word, work, year, yoke |

一方,ゲルマン祖語にさかのぼる,ゲルマン語に特有の基本英単語を挙げてみよう(寺澤,p. 1657).眺めてみると,印欧祖語の時代に比べ「社会生活の進歩,環境の変化がうかがわれ」「とくに,農耕・牧畜関係の語の充実とともに,航海・漁業関係の語が豊富であり,戦争・宗教関係の語も目立つ」(寺澤,p. 1657)ことが確認できる.

| 身体 | bone, hand, toe |

| 穀物・食物 | berry, broth, knead, loaf, wheat |

| 動物 | bear, lamb, sheep, †hengest (G Hangst), roe, seal, weasel |

| 鳥類 | dove, hawk, hen, rave, stork |

| 海洋 | cliff, east, west, north, south, ebb, sail, sea, ship, steer, keel, haven, sound, strand, swim, net, tackle, stem |

| 戦争 | bow, helm, shield, sword, weapon |

| 絎???? | god, ghost, heaven, hell, holy, soul, weird, werewolf |

| 住居 | bed, bench, hall |

| 社会 | atheling, earl, king, knight, lord, lady, knave, wife, borough |

| 経済 | buy, ware, worth |

| その他 | winter, rain, ground steel, tin |

「基本語彙」を巡る議論については,(基本語彙) の各記事を参照.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2019-06-24 Mon

■ #3710. 印欧祖語の帯気有声閉鎖音はラテン語ではおよそ f となる [indo-european][latin][sound_change][consonant][grimms_law][labiovelar][italic][greek][phonetics]

英語のボキャビルのために「グリムの法則」 (grimms_law) を学んでおくことが役に立つということを,「なぜ「グリムの法則」が英語史上重要なのか」などで論じてきたが,それと関連して時折質問される事項について解説しておきたい.印欧祖語の帯気有声閉鎖音は,英語とラテン語・フランス語では各々どのような音へ発展したかという問題である.

印欧祖語の帯気有声閉鎖音 *bh, *dh, *gh, *gwh は,ゲルマン語派に属する英語においては,「グリムの法則」の効果により,各々原則として b, d, g, g/w に対応する.

一方,イタリック語派に属するラテン語は,問題の帯気有声閉鎖音は,各々 f, f, h, f に対応する(cf. 「#1147. 印欧諸語の音韻対応表」 ([2012-06-17-1])).一見すると妙な対応だが,要するにイタリック語派では原則として帯気有声閉鎖音は調音点にかかわらず f に近い子音へと収斂してしまったと考えればよい.

実はイタリック語派のなかでもラテン語は,共時的にややイレギュラーな対応を示す.語頭以外の位置では上の対応を示さず,むしろ「グリムの法則」の音変化をくぐったような *bh > b, *dh > d, *gh > g を示すのである.ちなみにギリシア語派のギリシア語では,各々無声化した ph, th, kh となることに注意.

結果として,印欧祖語,ギリシア語,(ゲルマン祖語),英語における帯気有声閉鎖音3音の音対応は次のようになる(寺澤,p. 1660--61).

| IE | Gk | L | Gmc | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bh | phāgós | fāgus | ƀ, b | book |

| dh | thúrā | forēs (pl.) | ð, d | door |

| gh | khḗn | anser (< *hanser) | ʒ, g | goose |

この点に関してイタリック語派のなかでラテン語が特異なことは,Fortson でも触れられているので,2点を引用しておこう.

The characteristic look of the Italic languages is due partly to the widespread presence of the voiceless fricative f, which developed from the voiced aspirate[ stops]. Broadly speaking, f is the outcome of all the voiced aspirated except in Latin; there, f is just the word-initial outcome, and several other reflexes are found word-internally. (248)

The main hallmark of Latin consonantism that sets it apart from its sister Italic languages, including the closely related Faliscan, is the outcome of the PIE voiced aspirated in word-internal position. In the other Italic dialects, these simply show up written as f. In Latin, that is the usually outcome word-initially, but word-internally the outcome is typically a voiced stop, as in nebula 'cloud' < *nebh-oleh2, medius 'middle' < *medh(i)i̯o-, angustus 'narrow' < *anĝhos, and ninguit < *sni-n-gwh-eti)

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

・ Fortson IV, Benjamin W. Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004.

2019-06-11 Tue

■ #3697. 印欧語根 *spek- に由来する英単語を探る [etymology][indo-european][latin][greek][metathesis][word_family][lexicology]

昨日の記事「#3696. ボキャビルのための「最も役に立つ25の語のパーツ」」 ([2019-06-10-1]) で取り上げたなかでも最上位に挙げられている spec(t) という連結形 (combining_form) について,今回はさらに詳しくみてみよう.

この連結形は印欧語根 *spek- にさかのぼる.『英語語源辞典』の巻末にある「印欧語根表」より,この項を引用しよう.

spek- to observe. 《Gmc》[その他] espionage, spy. 《L》 aspect, auspice, conspicuous, despicable, despise, especial, expect, frontispiece, haruspex, inspect, perspective, prospect, respect, respite, species, specimen, specious, spectacle, speculate, suspect. 《Gk》 bishop, episcopal, horoscope, sceptic, scope, -scope, -scopy, telescope.

また,語源の取り扱いの詳しい The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language の巻末には,"Indo-European Roots" なる小辞典が付随している.この小辞典から spek- の項目を再現すると,次のようになる.

spek- To observe. Oldest form *spek̂-, becoming *spek- in centum languages.

▲ Derivatives include espionage, spectrum, despise, suspect, despicable, bishop, and telescope.

I. Basic form *spek-. 1a. ESPY, SPY, from Old French espier, to watch; b. ESPIONAGE, from Old Italian spione, spy, from Germanic derivative *speh-ōn-, watcher. Both a and b from Germanic *spehōn. 2. Suffixed form *spek-yo-, SPECIMEN, SPECTACLE, SPECTRUM, SPECULATE, SPECULUM, SPICE; ASPECT, CIRCUMSPECT, CONSPICUOUS, DESPISE, EXPECT, FRONTISPIECE, INSPECT, INTROSPECT, PERSPECTIVE, PERSPICACIOUS, PROSPECT, RESPECT, RESPITE, RETROSPECT, SPIEGELEISEN, SUSPECT, TRANSPICUOUS, from Latin specere, to look at. 3. SPECIES, SPECIOUS; ESPECIAL, from Latin speciēs, a seeing, sight, form. 4. Suffixed form *spek-s, "he who sees," in Latin compounds. a. Latin haruspex . . . ; b. Latin auspex . . . . 5. Suffixed form *spek-ā-. DESPICABLE, from Latin (denominative) dēspicārī, to despise, look down on (dē-), down . . .). 6. Suffixed metathetical form *skep-yo-. SKEPTIC, from Greek skeptesthai, to examine, consider.

II. Extended o-grade form *spoko-. SCOPE, -SCOPE, -SCOPY; BISHOP, EPISCOPAL, HOROSCOPE, TELESCOPE, from metathesized Greek skopos, on who watches, also object of attention, goal, and its denominative skopein (< *skop-eyo-), to see. . . .

2つの辞典を紹介したが,語源を活用した(超)上級者向け英語ボキャビルのためのレファレンスとしてどうぞ.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

・ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. 4th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006.

2019-03-05 Tue

■ #3599. 言語と人種 (2) [comparative_linguistics][indo-european][family_tree][biology][race][language_myth]

「#1871. 言語と人種」 ([2014-06-11-1]) の続編.先の記事では「言語=人種」という「俗説」に光を当てた.言語と人種を同一視することはできないと主張したわけだが,もっと正確にいえば,両者を「常に」同一視することはできない,というべきだろう.常に同一視する見方に警鐘を鳴らしたのであって,イコール関係が成り立つ場合もあるし,実際には決して少なくないと思われる.少なくないからこそ,一般化され俗説へと発展しやすいのだろう.

近年の遺伝学や人類学の発展により,ホモ・サピエンスの数万年にわたるヨーロッパなどでの移動の様子がつかめるようになってきたが,それと関係づける形で印欧語の派生や展開を解釈しようという動きも出てきた.このような研究は,上記のような俗説に警鐘を鳴らす陣営からは批判の的となるが,言語と人種をペアで考えてもよい事例をたくさん挙げることにより,この批判をそらそうとしている.

McMahon and McMahon (19--20) もそのような論客である.一般的にいって,遺伝子と言語の間に相関関係がないと考えるほうが不自然ではないかという議論だ.

. . . since we are talking here about the histories of populations, which consist of people who both carry genes and use languages, it might be more surprising if there were no correlations between genetic and linguistic configurations. The observation of this correlation, like so many others, goes back to Darwin . . . , who suggested that, 'If we possessed a perfect pedigree of mankind, a genealogical arrangement of the races of man would afford the best classification of the various languages now spoken throughout the world'. The norm today is to accept a slight tempering of this hypothesis, such that, 'The correlation between genes and languages cannot be perfect . . .', because both languages and genes can be replaced independently, but, 'Nevertheless . . . remains positive and statistically significant' . . . . This correlation is supported by a range of recent studies. For instance, Barbujani . . . reports that, 'In Europe, for example, . . . several inheritable diseases differ, in their incidence, between geographically close but linguistically distant populations', while Poloni et al. . . . show that a group of individuals fell into four non-overlapping classes on the basis of their genetic characteristics and whether they spoke an Indo-European, Khoisan, Niger-Congo or Afro-Asiatic language. In other words, there is a general and telling statistical correlation between genetic and linguistic features, which reflects interesting and investigable parallelism rather than determinism. Genetic and linguistic commonality now therefore suggests ancestral identity at an earlier stage: as Barbujani . . . observes, 'Population admixture and linguistic assimilation should have weakened the correspondence between patterns of genetic and linguistic diversity. The fact that such patterns are, on the contrary, well correlated at the allele-frequency level . . . suggests that parallel linguistic and allele-frequency change were not the exception, but the rule.

McMahon and McMahon とて,言語と人種の相関係数が1であるとはまったく述べていない.0というわけはない,そこそこ高い値と考えるのが自然なのではないか,というほどのスタンスだろう.それはそれで間違っていないと思うが,「常に言語=人種」の俗説たることを押さえた上での上級者向けの議論ととらえる必要があるだろう.

・ McMahon, April and Robert McMahon. "Finding Families: Quantitative Methods in Language Classification." Transactions of the Philological Society 101 (2003): 7--55.

2019-02-26 Tue

■ #3592. 文化の拡散を巡る migrationism と diffusionism [history][archaeology][comparative_linguistics][terminology][contact][indo-european]

印欧祖語の故地と年代を巡る論争と,祖語から派生した諸言語がいかに東西南北へ拡散していったかという論争は,連動している.比較的広く受け入れられており,伝統的な説となっているの,Gimbutas によるクルガン文化仮説である(cf. 「#637. クルガン文化と印欧祖語」 ([2011-01-24-1])).大雑把にいえば,印欧祖語は紀元前4000年頃の南ロシアのステップ地帯に起源をもち,その後,各地への移住と征服により,先行する言語を次々と置き換えていったというシナリオである.

一方,Renfrew の仮説は,Gimbutas のものとは著しく異なる.印欧祖語は先の仮説よりも数千年ほど古く(分岐開始を紀元前6000--7500年とみている),故地はアナトリアであるという.そして,派生言語の拡散は,征服によるものというよりは,新しく開発された農業技術とともにあくまで文化的に伝播したと考えている(cf. 「#1117. 印欧祖語の故地は Anatolia か?」 ([2012-05-18-1]),「#1129. 印欧祖語の分岐は紀元前5800--7800年?」 ([2012-05-30-1])).

2つの仮説について派生言語の拡散様式の対立に注目すると,前者は migrationism,後者は diffusionism の立場をとっているとみなせる.これは,言語にかぎらず広く文化の拡散について考えられ得る2つの様式である.Oppenheimer (521, 15) より,それぞれの定義をみておこう.

migrationism

The view that major cultural changes in the past were caused by movements of people from one region to another carrying their culture with them. It has displaced the earlier and more warlike term invasionism, but is itself out of archaeological favour.

diffusionism

Cultural diffusion is the movement of cultural ideas and artefacts among societies . . . . The view that major cultural innovations in the past were initiated at a single time and place (e.g. Egypt), diffusing from one society to all others, is an extreme version of the general diffusionist view --- which is that, in general, diffusion of ideas such as farming is more likely than multiple independent innovations.

印欧諸語の拡散様式ついて上記の論争があるのと同様に,アングロサクソンのイングランド征服についても似たような論争がある.一般的にいわれる,アングロサクソンの征服によって先住民族ケルト人が(ほぼ完全に)征服されたという説を巡っての論争だ.これについては明日の記事で.

・ Oppenheimer, Stephen. The Origins of the British. 2006. London: Robinson, 2007.

2019-01-03 Thu

■ #3538. 英語の subjunctive 形態は印欧祖語の optative 形態から [subjunctive][indo-european][optative][mood][terminology]

古い英語における接続法 (subjunctive) の祈願用法 (optative) について印欧比較言語学の脈絡で考えようとする際に気をつけなければならないのは,印欧祖語とゲルマン語派の間にちょっとした用語の乗り入れ(と混乱)があることだ.

印欧祖語では,命令の機能を担当した "imperative", おそらく未来時制の機能を担当した "subjunctive", 祈願の機能を担当した "optative" の間で形態が区別されていた.その後,ゲルマン語派へ枝分かれしていくなかで,印欧祖語の "optative" の形態が,娘言語における接続法 (subjunctive) として受け継がれた.つまり,形態に関する限り,印欧祖語の "subjunctive" と英語を含むゲルマン諸語の "subjunctive" とは,同名を与えられているにもかかわらず無関係であるということだ.ゲルマン祖語(とそれ以下の諸言語)で "subjunctive" と呼ばれるカテゴリーは,形態的にいえば印欧祖語の "optative" を受け継いだものなのである(ややこしい!).したがって,古い英語の接続法の形式が祈願の機能を有するのは,印欧祖語からの伝統として不思議でも何でもないということになる.

ただし別の語派では事情は異なる.例えばバルト・スラヴ語派においては,印欧祖語の "optative" は「命令法」や「許可法」として継承されているようで,ますます混乱する.

では,印欧祖語のもともとの "subjunctive" はどうなってしまったかというと,ゲルマン語には継承されていないようだ.インド・イラン語派,ギリシア語,そして部分的にケルト語派では,「未来」として継承されているという.形式と機能を分けて各用語を理解しておかないと混乱は必至である.

さらに厄介なのは,何せ印欧語比較言語学のこと,Hittite などの証拠に基づき,そもそも印欧祖語には "optative" も "subjunctive" も存在しなかったのではないかという説も唱えられている (Szemerényi 337) .いやはや.

・ Fortson IV, Benjamin W. "An Approach to Semantic Change." Chapter 21 of The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Ed. Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Blackwell, 2003. 648--66.

・ Szemerényi, Oswald J. L. Introduction to Indo-European Linguistics. Trans. from Einführung in die vergleichende Sprachwissenschaft. 4th ed. 1990. Oxford: OUP, 1996.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow