2016-05-19 Thu

■ #2579. 最初の英文法書 William Bullokar, Pamphlet for Grammar (1586) [history_of_linguistics][latin][emode][bullokar]

英語史上初の英文法書は,William Bullokar (c. 1530--1609) による Pamphlet for Grammar (1586) である.同じ著者による完全な文法は Grammar at large として世に出たようだが,現在は失われており,その簡略版ともいえる Pamphlet のみが残っている.この小冊子は,序文に書かれているように「英語を素早く解析し,より易しく他言語の文法の知識に至るべく」作られたものである.Bullokar は綴字改革案を提示した人物としても知られるが,実際にこの小冊子も改訂綴字で書かれている.Bullokar は,改革綴字の本や辞書など関連書の出版も企画していたようだが,残念ながら,それについては知られていない (Crystal 39) .

Pamphlet は,1509年に出版された William Lily のラテン語文法の英訳版 Short Introduction of Grammar (1548) に多く依拠している.ラテン語文法を土台とした英文法であるから,統語論については弱く,全体として中世的な文法書といえる.16世紀後半における英文法書の登場がラテン語に対する土着語の台頭を象徴するきわめて近代的な出来事であることを考えると,その内容が中世的,ラテン語的であるということは,一種の矛盾をはらんでいる.これについて,渡部 (68) は次のように論じている.

Bullokar にかぎらず,近世初期の文法一般について言えることであるが,序文と実際の内容の乖離が甚だしい,ということが先ず目につく.序文は当時の国語意識,愛国心などから書いているのできわめて新鮮にひびくけれども内容は中世のシステムにのっかることになっていた.これは逆説的にひびくけれども,英語が「文法」の枠に当てはまるほど立派な言語であることを証明するために,なるべくラテン文法に合わせて見せようとしたからである.文法といえば,学問語として権威のあるラテン語独特の属性と思われていたので,ラテン文法と同じ術語で英語を処理してみせることによって,英語がラテン語と同格になったとしてよろこんだのであった.だから,国民意識が新しければ新しいほど,内容は古くなるという逆説的な状況が起った.

このように,英語史上に名を残す最初の英文法書は,気持ちは近代,実質は中世を反映するという独特の歴史のタイミングで現われたのだった.

・ Crystal, David. Evolving English: One Language, Many Voices. London: The British Library, 2010.

・ 渡部 昇一 『英語学史』 英語学大系第13巻,大修館書店,1975年.

2016-02-09 Tue

■ #2479. 初期近代英語の語彙借用に対する反動としての言語純粋主義はどこまで本気だったか? [purism][lexicology][borrowing][emode][renaissance][inkhorn_term][cheke][aureate_diction]

「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1]) ,「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1]) などの記事で,初期近代英語の大量語彙借用の反動としての言語純粋主義 (purism) に触れた.確かに純粋主義者として Sir John Cheke (1514--57), Roger Ascham (1515?--68), Sir Thomas Chaloner, Thomas Wilson (1528?--81) などの個性の名前が挙がるが,Görlach (163--64) は,英国ルネサンスにおける反動的純粋主義については過大評価されてきたという見解を示している.彼らとて必要な語彙は借用せざるを得ず,実際に借用したのであり,あくまでラテン語やギリシア語の語彙の無駄な借用や濫用を戒めたのである,と.少々長いが,おもしろい議論なので,そのまま引用しよう.

Purism, understood as resistance to foreign words and as awareness of the possibilities of the vernacular, presupposes a certain level of standardization of, and confidence in, the native tongue. It is no surprise that puristic tendencies are unrecorded before the end of the Middle Ages --- wherever native expressions were coined to replace foreign terms, they served a different purpose to help the uneducated understand better, especially sermons and biblical paraphrase. Tyndale's striving for the proper English expression was still motivated by the desire to enable the ploughboy to understand more of the Bible than the learned bishops.

A puristic reaction was, then, provoked by fashionable eloquence, as is evident from aspects of fifteenth-century aureate diction and sixteenth-century inkhornism . . . . The humanists had rediscovered a classical form of Latin instituted by Roman writers who fought against Greek technical terms as well as fashionable Hellenization, but who could not do without terminologies for the disciplines dominated by Greek traditions. Ascham, Wilson and Cheke (all counted among the 'purists' in a loose application of the term) behaved exactly as Cicero had done: they wrote in the vernacular (no obvious choice around 1530--50), avoided fashionable loanwords and fanciful, rare expressions, but did not object to the borrowing of necessary terms.

Cheke was as inconsistent a 'purist' as he was a reformer of EModE spelling . . . . On the one hand, he went further than most of his contemporaries in his efforts to preserve the English language "vnmixt and vnmangeled" . . ., but on the other hand he also borrowed beyond what was necessary and what his own tenets seemed to allow. (The problem of untranslatable terms, as in his renderings of biblical antiquities, was solved by marginal explanations.) The practice (and historical ineffectiveness) of other 'purists', too, who attempted translations of Latin terminologies --- Golding for medicine, Lever for philosophy and Puttenham for rhetoric . . . --- demonstrates that there was no such rigorous puristic movement in sixteenth-century England as there was in many other countries during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The purists' position and their influence on EModE has often been exaggerated; it is more to the point to speak of "different degrees of Latinity" . . . .

Görlach の見解は,通説とは異なる独自の指摘であり,斬新だ.中英語期のフランス借用語批判や,日本語における明治期のチンプン漢語及び戦後のカタカナ語の流入との関係で指摘される言語純粋主義も,この視点から見直してみるのもおもしろいだろう (see 「#2147. 中英語期のフランス借用語批判」 ([2015-03-14-1]),「#1630. インク壺語,カタカナ語,チンプン漢語」 ([2013-10-13-1]),「#1999. Chuo Online の記事「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」」 ([2014-10-17-1])).

・ Görlach, Manfred. Introduction to Early Modern English. Cambridge: CUP, 1991.

2016-02-08 Mon

■ #2478. 祈願の may と勧告の let の発達の類似性 [pragmatics][syntax][word_order][speech_act][emode][subjunctive][auxiliary_verb][optative][hortative][may]

「#1867. May the Queen live long! の語順」 ([2014-06-07-1]) の最後で触れたように,may 祈願文と let 勧告文には類似点がある.いずれも統語的には節の最初に現われるという破格的な性質を示し,直後に3人称主語を取ることができ,語用論的には祈願・勧告というある意味で似通った発話行為を担うことができる.最後の似通っている点に関していえば,いずれの発話行為も,古英語から中英語にかけて典型的に動詞の接続法によって表わし得たという共通点がある.通時的には,may にせよ let にせよ,接続法動詞の代用を務める迂言法を成立させる統語的部品として,キャリアを始めたわけだが,そのうちに使用が固定化し,いわば各々祈願と勧告という発話行為を標示するマーカー,すなわち "pragmatic particle" として機能するに至った.may と let を語用的小辞として同類に扱うという発想は,前の記事で言及した Quirk et al. のみならず,英語歴史統語論を研究している Rissanen (229) によっても示されている(松瀬,p. 82 も参照).

The optative subjunctive is often replaced by a periphrasis with may and the hortative subjunctive with let:

(229) 'A god rewarde you,' quoth this roge; 'and in heauen may you finde it.' ([HC] Harman 39)

(230) Let him love his wife even as himself: That's his Duty. ([HC] Jeremy Taylor 24)

Note the variation between the subjunctive rewarde and the periphrastic may . . . finde in (229).

Of these two periphrases, the one replacing hortative subjunctive seems to develop more rapidly: in Marlow, at the end of the sixteenth century, the hortative periphrasis clearly outnumbers the subjunctive, particularly in the 1 st pers. pl. . ., while the optative periphrasis is less common than the subjunctive.

ここで Rissanen は,may と let を用いた迂言的祈願・勧告の用法の発達を同列に扱っているが,両者が互いに影響し合ったかどうかには踏み込んでいない.しかし,発達時期の差について言及していることから,前者の発達が後者の発達により促進されたとみている可能性はあるし,少なくとも Rissanen を参照している松瀬 (82) はそのように解釈しているようだ.この因果関係や時間関係についてはより詳細な調査が必要だが,一見するとまるで異なる語にみえる may と let を,語用(小辞)化の結晶として見る視点は洞察に富む.

関連して祈願の may については「#2256. 祈願を表わす may の初例」 ([2015-07-01-1]) を,勧告の let's の間主観化については「#1981. 間主観化」 ([2014-09-29-1]) も参照.

・ Rissanen, Matti. Syntax. In The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 187--331.

・ 松瀬 憲司 「"May the Force Be with You!"――英語の may 祈願文について――」『熊本大学教育学部紀要』64巻,2015年.77--84頁.

2015-12-07 Mon

■ #2415. 急進的表音主義の綴字改革者 John Hart による重要な提案 [spelling_reform][spelling][grapheme][alphabet][emode][hart][orthography][j][v]

初期近代英語期の綴字改革者 John Hart (c. 1501--74) について,「#1994. John Hart による語源的綴字への批判」 ([2014-10-12-1]),「#1942. 語源的綴字の初例をめぐって」 ([2014-08-21-1]),「#1940. 16世紀の綴字論者の系譜」 ([2014-08-19-1]),「#1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論」 ([2014-08-18-1]),「#1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題」 ([2013-03-04-1]),「#583. ドイツ語式の名詞語頭の大文字使用は英語にもあった」 ([2010-12-01-1]),「#441. Richard Mulcaster」 ([2010-07-12-1]) の記事で言及してきた.

Hart は,当時,表音主義の立場にたつ綴字改革の急先鋒であり,「1文字=1音」の理想へと邁進していた.しかし,後続の William Bullokar (fl. 1586) とともに,あまりに提案が急進的だったために,当時の人々にまともに取り上げられることはなかった.それでも,Hart の提案のなかで,後に結果として標準綴字に採用された重要な項目が2つある.<u> と <v> の分化,そして <i> と <j> の分化である.それぞれの分化の概要については,「#373. <u> と <v> の分化 (1)」 ([2010-05-05-1]),「#374. <u> と <v> の分化 (2)」 ([2010-05-06-1]),「#1650. 文字素としての j の独立」 ([2013-11-02-1]) で触れた通りだが,これを意図的に強く推進しようとした人物が Hart その人だった.Horobin (120--21) は,この Hart の貢献について,次のように評価している.

In many ways Hart's is a sensible, if slightly over-idealized, view of the spelling system. Some of the reforms introduced by him have in fact been adopted. Before Hart the letter <j> was not a separate letter in its own right; in origin it is simply a variant form of the Roman letter <I>. In Middle English it was used exclusively as a variant of the letter <i> where instances appear written together, as in lijf 'life', and is common in Roman numerals, such as iiij for the number 4. . . . Hart advocated using the letter <j> as a separate consonant to represent the sound /dʒ/, as we still do today. A similar situation surrounds the letters <u> and <v>, which have their origins in the single Roman letter <V>. In the Middle English period they were positional variants, so that <v> appeared at the beginning of words and <u> in the middle of words, irrespective of whether they represented the vowel or consonant sound. Thus we find Middle English spellings like vntil, very, loue, and much. Hart's innovation was to make <u> the vowel and <v> the consonant, so that their appearance was dependent upon use, rather than position in the word.

現代の正書法につらなる2対の文字素の分化について,Hart のみの貢献と断じるわけにはいかない.しかし,彼のラディカルな提案のすべてが水泡に帰したわけではなかったということは銘記してよい.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2015-11-26 Thu

■ #2404. <nacio(u)n> → <nation> の綴字変化 (2) [etymological_respelling][spelling][spelling_reform][consonant][latin][emode]

「#2018. <nacio(u)n> → <nation> の綴字変化」 ([2014-11-05-1]) に引き続いての話題.ただし,nation という1単語にとどまらず,一般にラテン語の -tiō に遡る語尾をもつ語彙の綴字が,中英語の -<cion> から近代英語の -<tion> へと変化した事情に注目する.

先の記事で示唆したように,この <c> → <t> の変化は語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) と考えられる.語源的綴字は,ある程度は類型化できるものの,たいていはいくつかの語において単発的に生じるものであり,体系的な現象ではない.しかし,そのなかでもラテン語 -tiō を参照した <c> → <t> の変化はおよそ規則的に生じたようであり,その程度において意識的だったといえる.規則的で意識的だったということは,見方によればこの変化は綴字改革 (spelling_reform) の成果だったと言えなくもない.英語の綴字改革の歴史において,多少なりとも成功した試みは Noah Webster のものくらいしかない(それとてあくまで部分的)と言われるが,初期近代英語の <c> → <t> はもう1つの例外的な成功例とみることができるかもしれない.

Venezky (38) は,-<tion> のみならず -<tial> も含めて,この変化について以下のように触れている.

. . . a number of graphemic substitutions, introduced mostly between the times of Chaucer and Shakespeare, must be treated separately. One of these is the substitution of t for c in suffixes like tion and tial, e.g., nation, essential (cf. ME, nacion, essenciall). Early Modern English scribes, instilled with the fervor of classical learning, brought about in these substitutions one of the few true spelling reforms in English orthographic history.

・ Venezky, Richard L. The Structure of English Orthography. The Hague: Mouton, 1970.

2015-10-31 Sat

■ #2378. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (2) [final_e][grapheme][spelling][orthography][emode][printing][mulcaster][spelling_reform][diacritical_mark]

昨日に引き続いての話題.Caon (297) によれば,先行する長母音を表わす <e> を最初に提案したのは,昨日述べたように,16世紀後半以降の Mulcaster や同時代の綴字改革者であると信じられてきたが,Salmon を参照した Caon (297) によれば,実はそれよりも半世紀ほど遡る16世紀前半に John Rastell なる人物によって提案されていたという.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries linguists and spelling reformers attempted to set down rules for the use of final -e. Richard Mulcaster is believed to have been the one who first formulated the modern rule for the use of the ending. In The First Part of the Elementarie (1582) he proposed to add final -e in certain environments, that is, after -ld; -nd; -st; -ss; -ff; voiced -c, and -g, and also in words where it signalled a long stem vowel (Scragg 1974:79--80, Brengelman 1980:348). His proposals were reanalysed later and in the eighteenth century only the latter function was standardised (see Modern English hop--hope; bit--bite). However. according to Salmon (1989:294). Mulcaster was not the first one to recommend such a use of final -e; in fact, the sixteenth-century printer John Rastell (c. 1475--1536) had already suggested it in The Boke of the New Cardys (1530). In this book of which only some fragments have survived, Rastell formulated several rules for the correct spelling of English words, recommending the use of final -e to 'prolong' the sound of the preceding vowel.

早速 Salmon の論文を入手して読んでみた.John Rastell (c. 1475--1536) は,法律印刷家,劇作家,劇場建築者,辞書編纂者,音楽印刷家,海外植民地の推進者などを兼ねた多才な人物だったようで,読み書き教育や正書法にも関心を寄せていたという.問題の小冊子は The boke of the new cardys wh<ich> pleyeng at cards one may lerne to know hys lett<ers,> spel [etc.] という題名で書かれており,およそ1530年に Rastell により印刷(そして,おそらく書かれも)されたと考えられている.現存するのは断片のみだが,関与する箇所は Salmon の論文の末尾 (pp. 300--01) に再現されている.

Rastell の綴字への関心は,英訳聖書の異端性と必要性が社会問題となっていた時代背景と無縁ではない.Rastell は,印刷家として,読みやすい綴字を世に提供する必要を感じており,The boke において綴字の理論化を試みたのだろう.Rastell は,Mulcaster などに先駆けて,16世紀前半という早い時期に,すでに正書法 (orthography) という新しい発想をもっていたのである.

Rastell は母音や子音の表記についていくつかの提案を行っているが,標題と関連して,Salmon (294) の次の指摘が重要である."[A]nother proposal which was taken up by his successors was the employment of final <e> (Chapter viii) to 'perform' or 'prolong' the sound of the preceding vowel, a device with which Mulcaster is usually credited (cf. Scragg 1974: 79)."

しかし,この早い時期に正書法に関心を示していたのは Rastell だけでもなかった.同時代の Thomas Poyntz なるイングランド商人が,先行母音の長いことを示す diacritic な <e> を提案している.ただし,Poyntz が提案したのは,Rastell や Mulcaster の提案とは異なり,先行母音に直接 <e> を後続させるという方法だった.すなわち,<saey>, <maey>, <daeys>, <moer>, <coers> の如くである (Salmon 294--95) .Poyntz の用法は後世には伝わらなかったが,いずれにせよ16世紀前半に,学者たちではなく実業家たちが先導する形で英語正書法確立の動きが始められていたことは,銘記しておいてよいだろう.

・ Caon, Louisella. "Final -e and Spelling Habits in the Fifteenth-Century Versions of the Wife of Bath's Prologue." English Studies (2002): 296--310.

・ Salmon, Vivian. "John Rastell and the Normalization of Early Sixteenth-Century Orthography." Essays on English Language in Honour of Bertil Sundby. Ed. L. E. Breivik, A. Hille, and S. Johansson. Oslo: Novus, 1989. 289--301.

2015-10-30 Fri

■ #2377. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (1) [final_e][grapheme][spelling][orthography][emode][mulcaster][spelling_reform][meosl][diacritical_mark]

英語史において,音声上の final /e/ の問題と,綴字上の final <e> の問題は分けて考える必要がある.15世紀に入ると,語尾に綴られる <e> は,対応する母音を完全に失っていたと考えられているが,綴字上はその後も連綿と書き続けられた.現代英語の正書法における発音区別符(号) (diacritical mark; cf. 「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1])) としての <e> の機能については「#979. 現代英語の綴字 <e> の役割」 ([2012-01-01-1]), 「#1289. magic <e>」 ([2012-11-06-1]) で論じ,関係する正書法上の発達については 「#1344. final -e の歴史」 ([2012-12-31-1]), 「#1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論」 ([2014-08-18-1]) で触れてきた.今回は,英語正書法において長母音を表わす <e> がいかに発達してきたか,とりわけその最初期の様子に触れたい.

Scragg (79--80) は,中英語の開音節長化 (meosl) に言い及びながら,問題の <e> の機能の規則化は,16世紀後半の穏健派綴字改革論者 Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) に帰せられるという趣旨で議論を展開している(Mulcaster については,「#441. Richard Mulcaster」 ([2010-07-12-1]) 及び mulcaster の各記事を参照されたい).

One of the most far-reaching changes Mulcaster suggested was for the use of final unpronounced <e> as a marker of vowel length. Of the many orthographic indications of a long vowel in English, the one with the longest history is doubling of the vowel symbol, but this has never been regularly practised. . . . Use of final <e> as a device for denoting vowel length (especially in monosyllabic words such as mate, mete, mite, mote, mute, the stem vowels of which have now usually been diphthongised in Received Pronunciation) has its roots in an eleventh-century sound-change involving the lengthening of short vowels in open syllables of disyllabic words (e.g. /nɑmə/ became /nɑːmə/). When final unstressed /ə/ ceased to be pronounced after the fourteenth century, /nɑːmə/, spelt name, became /nɑːm/, and paved the way for the association of mute final <e> in spelling with a preceding long vowel. After the loss of final /ə/ in speech, writers used final <e> in a quite haphazard way; in printed books of the sixteenth century <e> was added to almost every word which would otherwise end in a single consonant, though the fact that it was then apparently felt necessary to indicate a short stem vowel by doubling the consonant (e.g. bedde, cumme, fludde 'bed, come, flood') shows that writers already felt that final <e> otherwise indicated a long stem vowel. Mulcaster's proposal was for regularisation of this final <e>, and in the seventeenth century its use was gradually restricted to the words in which it still survives.

Brengelman (347) も同様の趣旨で議論しているが,<e> の規則化を Mulcaster のみに帰せずに,Levins や Coote など同時代の正書法に関心をもつ人々の集合的な貢献としてとらえているようだ.

It was already urged in the last quarter of the sixteenth century that final e should be used as a vowel diacritic. Levins, Mulcaster, Coote, and others had urged that final e should be used only to "draw the syllable long." A corollary of the rule, of course, was that e should not be used after short vowels, as it commonly was in words such as egge and hadde. Mulcaster believed it should also be used after consonant groups such as ld, nd, and st, a reasonable suggestion that was followed only in the case of -ast. . . . By the time Blount's dictionary had appeared (1656), the modern rule regarding the use of final e as a vowel diacritic had been generally adopted.

いずれにせよ,16世紀中には(おそらくは15世紀中にも),すでに現実的な綴字使用のなかで <e> のこの役割は知られていたが,意識的に使用し規則化しようとしたのが,Mulcaster を中心とする1600年前後の改革者たちだったということになろう.実際,この改革案は17世紀中に根付いていくことになり,現在の "magic <e>" の規則が完成したのである.

・ Scragg, D. G. A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974.

・ Brengelman, F. H. "Orthoepists, Printers, and the Rationalization of English Spelling." JEGP 79 (1980): 332--54.

2015-10-01 Thu

■ #2348. 英語史における code-switching 研究 [code-switching][me][emode][bilingualism][contact][latin][french][literature][borrowing][genre][historical_pragmatics][discourse_analysis]

本ブログでは code-switching (CS) に関していくつかの記事を書いてきた.とりわけ英語史の視点からは,「#1470. macaronic lyric」 ([2013-05-06-1]),「#1625. 中英語期の書き言葉における code-switching」 ([2013-10-08-1]),「#1941. macaronic code-switching としての語源的綴字?」 ([2014-08-20-1]),「#2271. 後期中英語の macaronic な会計文書」 ([2015-07-16-1]) で論じてきた.現代語の CS に関わる研究の発展に後押しされる形で,また歴史語用論 (historical_pragmatics) の流行にも支えられる形で,歴史的資料における CS の研究も少しずつ伸びてきているようであり,英語史においてもいくつか論文集が出されるようになった.

しかし,歴史英語における CS の実態は,まだまだ解明されていないことが多い.そもそも,CS が観察される歴史テキストはどの程度残っているのだろうか.Schendl は,中英語から初期近代英語にかけて,複数言語が混在するテキストは決して少なくないと述べている.

There is a considerable number of mixed-language texts from the ME and the EModE periods, many of which show CS in mid-sentence. The phenomenon occurs across genres and text types, both literary and non-literary, verse and prose; and the languages involved mirror the above-mentioned multilingual situation. In most cases Latin as the 'High' language is one of the languages, with one or both of the vernaculars English and French as the second partner, though switching between the two vernaculars is also attested. (79)

CS in written texts was clearly not an exception but a widespread specific mode of discourse over much of the attested history of English. It occurs across domains, genres and text types --- business, religious, legal and scientific texts, as well as literary ones. (92)

ジャンルを問わず,様々なテキストに CS が見られるようだ.文学テキストとしては,具体的には "(i) sermons; (ii) other religious prose texts; (iii) letters; (iv) business accounts; (v) legal texts; (vi) medical texts" が挙げられており,非文学テキストとしては "(i) mixed or 'macaronic' poems; (ii) longer verse pieces; (iii) drama; (iv) various prose texts" などがあるとされる (Schendl 80) .

英語史あるいは歴史言語学において CS (を含むテキスト)を研究する意義は少なくとも3点ある.1つは,過去の2言語使用と言語接触の状況の解明に資する点だ.2つめは,CS と借用の境目を巡る問題に関係する.語彙借用の多い英語の歴史にとって,借用の過程を明らかにすることは,理論的にも実際的にも極めて重要である (see 「#1661. 借用と code-switching の狭間」 ([2013-11-13-1]),「#1985. 借用と接触による干渉の狭間」 ([2014-10-03-1]),「#1988. 借用語研究の to-do list (2)」 ([2014-10-06-1]),「#2009. 言語学における接触,干渉,2言語使用,借用」 ([2014-10-27-1])) .3つめに,共時的な CS 研究に通時的な次元を与えることにより,理論を深化させることである.

・ Schendl, Herbert. "Linguistic Aspects of Code-Switching in Medieval English Texts." Multilingualism in Later Medieval Britain. Ed. D. A. Trotter. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000. 77--92.

2015-09-21 Mon

■ #2338. 16世紀,hem, 'em 不在の謎 (2) [personal_pronoun][emode][corpus][eebo][punctuation][apostrophe]

昨日の記事 ([2015-09-20-1]) に引き続いての話題.16世紀に hem, 'em が不在,あるいは非常に低頻度という件について,EEBO (Early English Books Online) のテキストデータベースを利用して,簡易検索してみた.検索結果は,動詞 hem を含め,相当の雑音が混じっており,丁寧に除去する手間は取っていないものの,16世紀からの例は確かに極端に少ないことがわかった.

16世紀前半からの明確な例は,Andrew Boorde, The pryncyples of astronamye (1547) に現われる "doth geue influence to hem the which be borne vnder this signe" の1例のみである.16世紀前半の300万語ほどのサブコーパスのなかで,極めて珍しい.'em に至っては,16世紀後半のサブコーパスも含めても例がない.

16世紀後半のサブコーパスでも,hem の例は少々現われるとはいえ,さして状況は変わらない.F. T., The debate betweene Pride and Lowlines (1577) なるテキストにおいて "for they doon hem blame", "For which hem thinketh they should been aboue" などと生起したり,Joseph Hall, Certaine worthye manuscript poems of great antiquitie reserued long in the studie of a Northfolke gentleman (1597) という当時においても古めかしい詩のなかで何度か現われたりする程度である.

一方,17世紀サブコーパスの検索結果一覧をざっと眺めると,hem の頻度が著しく増えたという印象はないが,'em が見られ始め,ある程度拡張している様子である.後者の 'em の出現は,アポストロフィという句読記号自体の拡大が17世紀にかけて進行したことと関係するだろう (see 「#582. apostrophe」 ([2010-11-30-1])) .

hem, 'em の歴史的継続性という議論については,問題の16世紀にもかろうじて用例が文証されるということから,継続性を認めてよいだろうとは考える.口語ではもっと頻繁に用いられていただろうという推測も,おそらく正しいだろう.しかし,なぜ文章の上にほとんど反映されなかったのかという疑問は残るし,17世紀以降に復活してきた際に,すでに共時的には them の省略形と解釈されていた可能性についてどう考えるかという問題も残る.この話題は,いまだ謎といってよい.

2015-09-20 Sun

■ #2337. 16世紀,hem, 'em 不在の謎 (1) [personal_pronoun][emode][apostrophe]

「#2331. 後期中英語における3人称複数代名詞の段階的な th- 化」 ([2015-09-14-1]) の最後で触れたように,古い3人称複数代名詞の与格に由来する hem あるいはその弱形 'em は,標準英語では1500年頃までに them によりほぼ置換された.しかし,16世紀末以降,口語的な響きをもって再び文献に現われ出す.'em は,現在の口語の I got 'em. にみられるように,いまだその痕跡を残しているといわれるが,古英語や中英語から現代英語にいたる歴史的継続性を主張するためには,16世紀中の証拠の不在が問題となりそうだ.Wyld (327--28) がこの問題に触れている.

The history of hem is rather curious. It survives in constant use among nearly all writers during the fifteenth century, often alongside the th- form. I have not noted any sixteenth-century example of it in the comparatively numerous documents I have examined, until quite at the end of the century. It reappears, however, in Marston and Chapman early in the seventeenth century, and in the form 'em occurs, though sparingly, in the Verney Mem. towards the end of the seventeenth century, where the apostrophe shows that already it was thought to be a weakened form of them. During the eighteenth century 'em becomes fairly frequent in printed books, and it is in common use to-day as [əm]. It is rather difficult to explain the absence of such forms as hem or em in the sixteenth century, since the frequency at a later period seems to show that, at any rate, the weak form without the aspirate must have survived throughout. The explanation must be that em, though commonly used, was felt, as now, to be merely a form of them.

Wyld は,16世紀中も hem, 'em は口語として続いていたはずだが,すでに them の(崩れた)略形として理解されており,文章の上に反映される機会がなかったのだろうという意見だ.

この仮説を裏付ける証拠はある.Wyld は16世紀からの用例が世紀末を除けば皆無としているが,OED の 'em, pron. の歴史的な例文を眺めると,語幹母音の揺れを無視すれば,hem や 'em の類いは,確かに少ないものの,いくつかは文証される.

・ a1525 (a1500) Sc. Troy Bk. (Douce) 143 in C. Horstmann Barbour's Legendensammlung (1882) II. 233 A ferlyfule sowne sodeynly Among heme maide was hydwisly.

・ a1525 Eng. Conquest Ireland (Trin. Dublin) (1896) 28 He bad ham well þorwe that thay sholden yn al manere senden after more of har kyn.

・ c1540 (?a1400) Gest Historiale Destr. Troy (2002) f. 66, Sotly hyt semys not surfetus harde No vnpossibill thys pupull perfourme in dede That fyuetymes fewer before home has done.

・ 1579 Spenser Shepheardes Cal. May 27 Tho to the greene Wood they speeden hem all.

・ 1589 'M. Marprelate' Hay any Worke for Cooper 48 Ile befie em that will say so of me.

しかし,歴史的連続性を主張するのに首の皮が一枚つながったという程度で,16世紀からの用例は確かに著しく少ないようである.口語的な語形として文章に反映される機会がなかったという点についても,もう少し掘り下げて考える必要がありそうだ.

なお,18世紀初めに,Swift が 'em をだらしない語法として非難していることを付け加えておこう.Wyld (329) 曰く,

Note that this form ['em] became so widespread in the early eighteenth-century speech that Swift complains that 'young readers in our churches in the prayer for the Royal Family, say endue'um, enrich'um, prosper'um, and bring'um. Tatler, No. 230 (1710).

・ Wyld, Henry Cecil. A History of Modern Colloquial English. 3rd ed. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1936.

2015-09-15 Tue

■ #2332. EEBO のキーワードを抽出 [eebo][lob][corpus][keyword][text_tool][emode]

コーパスからキーワードを拾うという分析を,「#317. 拙著で自分マイニング(キーワード編)」 ([2010-03-10-1]),「#518. Singapore English のキーワードを抽出」 ([2010-09-27-1]),「#880. いかにもイギリス英語,いかにもアメリカ英語の単語」 ([2011-09-24-1]) で紹介してきた.今回は初期近代英語を中心的に扱うテキスト・データベース EEBO (Early English Books Online) より,キーワードを拾ってみたい.

EEBO から個人的に収集した初期近代英語のテキスト集(全11億語以上)に対し,WordSmith の KeyWords 抽出機能を用いた.参照コーパスとしては,現代イギリス英語を代表するものとして LOB コーパスを指定した.本来は参照コーパスのほうがずっと大規模ではなければならないのだが,EEBO が大きすぎるということで,今回は目をつぶっておきたい.狙いは,現代英語と比べて使用頻度の著しく高い初期近代英語の語を拾い出すということである.当時の社会を特徴づける語彙が集まるはずである.

キーワード性を示す指標の高い順に,500語までのリストがたちどころに得られた.いずれも小文字で示す.

[ Top 100 ]

amp, note, god, and, that, hath, them, christ, shall, haue, thou, they, thy, so, all, our, not, their, upon, doth, vnto, of, unto, his, king, yet, or, hee, eacute, vs, ye, him, lord, thee, which, bee, doe, saith, men, onely, but, vpon, be, nor, de, c, gods, by, faith, holy, great, church, your, o, as, selfe, wee, owne, ad, con, est, things, then, such, therefore, himselfe, may, y, to, sin, grace, cause, tis, us, mr, ther, kings, thereof, let, spirit, man, al, vp, yea, any, this, ac, s, pro, ing, com, thus, e, against, forth, re, shew, whom, l, wherein

[ -- 200 ]

loue, ly, selves, scripture, self, law, st, those, thing, cor, sinne, being, glory, euery, death, good, sonne, true, neuer, whereof, iohn, againe, psal, pope, religion, ed, hym, soule, hast, lib, ex, heaven, agrave, whiche, pray, neither, downe, acirc, tion, quod, my, sed, fore, soul, nature, euen, dayes, is, p, apostles, euer, till, feare, chap, ver, rom, vnder, ma, qui, vse, according, giue, power, ouer, mans, egrave, lesse, se, doctrine, ne, ment, meanes, themselues, shal, d, sins, viz, prince, did, vertue, wicked, honour, earth, ut, blessed, princes, ter, apostle, th, persons, que, thinke, same, others, lords, ought, pag, truth, none, kingdome

[ -- 300 ]

tho, si, cap, goe, if, beene, flesh, et, christs, make, fathers, concerning, reason, body, mercy, selues, enemies, bishops, farre, v, bishop, ar, hearts, wil, likewise, other, rome, name, obedience, en, wise, cum, speake, finde, nay, iesus, we, conscience, manner, non, heart, sinnes, it, yt, hauing, saints, generall, mat, contrary, worke, wit, sayd, whereby, covenant, wherefore, gen, passe, poore, lorde, publick, word, mens, suffer, na, heare, mee, ei, heb, divers, christians, therein, theyr, minde, shalt, bloud, shewed, certaine, vers, un, son, amongst, ibid, ca, jesus, betwixt, quae, scriptures, say, divine, thine, rest, countrey, besides, di, heauen, cannot, qu, therfore, godly, sent

[ -- 400 ]

m, moses, these, christian, called, n, vn, false, should, paul, also, discourse, meane, without, booke, whence, shee, emperour, souls, place, thereby, yeares, tyme, lawes, peace, what, dis, behold, foure, citie, giuen, israel, anno, liberty, thence, gospel, cast, ograve, aboue, souldiers, tooke, sa, priests, gaue, fol, maketh, places, pardon, te, warre, saviour, wayes, saint, thinges, will, themselves, kinde, suche, bene, love, salvation, yeare, towne, spirituall, esse, fa, duke, majesty, brethren, laws, alwayes, workes, ab, lest, for, wrath, wordes, soules, done, sunt, angels, vel, ry, liue, ted, ty, looke, repentance, dr, beare, prayer, keepe, faire, ii, parts, helpe, iudge, no, churches, r

[ -- 500 ]

dy, vsed, prophet, outward, ble, ap, spake, sect, armes, notwithstanding, come, h, naturall, maner, crosse, popes, sayth, pa, papists, whatsoever, gospell, iudgement, writ, noble, hoc, par, sacrifice, dye, worship, ons, af, eternal, leaue, ob, euill, am, sacrament, diuers, both, ghost, quam, lye, yee, comming, secondly, how, iustice, sword, daies, father, vi, before, prayers, bodie, whome, councell, nec, though, faithfull, lawe, humane, aut, wel, mi, hir, iii, worthy, isa, easie, ugrave, nowe, lawfull, ere, seene, priest, glorious, serue, commanded, earle, forme, thither, eternall, prophets, turne, iewes, mo, im, halfe, matth, manifest, wilt, are, words, iust, betweene, affections, ocirc, li, ned, creatures

対象としたのは EEBO から収集した平テキストであり,そこには多くの注記やタグも含まれている.それを除去するなどの特別なテキスト処理は施していないので,雑音も相当混じっていることに注意したい.実際,1位の amp はタグの一部であり,2位の note も注記を表わす記号と考えてよいので,いずれも無視すべきだが,ここではキーワード抽出結果をそのまま提示することにした.

現代でも高頻度語ではあるが,初期近代では綴字が異なる hath, haue, doth, hee, vs, bee などが上位に来ることは理解できるだろう.また,現代では古風となっている2人称単数代名詞 thou, thy, thee の顕著なことも理解できる.

おもしろいのは,現在でも現役ではあるが,それほど顕著ではなくなっている語である.例えば,リストの上位にキリスト教的な語が多いことに気づく.200位以内に限ってざっと拾うだけでも,god, christ, gods, faith, holy, church, grace, spirit, loue, scripture, sinne, glory, death, pope, religion, soule, heaven, pray, soul, apostles, vertue, wicked, honour, blessed, apostle などが挙がる.チューダー朝,スチュアート朝ともに,キリスト教に翻弄され続けた時代だったことも関係するだろう.逆にいえば,現代がいかに世俗化したか,ということでもある.

綴字としては,無音の <e> の自由な付加・脱落,<u> と <v> 及び <i> と <j> の混在,shall の顕著な使用,ye の残存などが挙げられるだろう (see 「#373. <u> と <v> の分化 (1)」 ([2010-05-05-1]),「#374. <u> と <v> の分化 (2)」 ([2010-05-06-1]); 「#1650. 文字素としての j の独立」 ([2013-11-02-1])) .また,現在では堅苦しい機能語も多い (ex. upon, vnto, nor, therefore, thereof, whereof) .

2015-09-04 Fri

■ #2321. 綴字標準化の緩慢な潮流 [emode][spelling][standardisation][printing]

英語の綴字の標準化の潮流は,その端緒が見られる後期中英語から,初期近代英語を経て,1755年の Johnson の Dictionary 出版に至るまで,長々と続いた.中英語におけるフランス語使用の衰退という現象も同様だが,このように数世紀にわたって緩慢と続く歴史的過程というのは,どうも理解しにくい.15世紀ではどの段階なのか,17世紀ではどの辺りかなど,直感的にとらえることが難しいからだ.

私の理解は次の通りだ.14世紀後半,Chaucer の時代辺りに書き言葉標準の芽生えがみられた.15世紀に標準化の流れが緩やかに進んだが,世紀後半の印刷術の導入は,必ずしも一般に信じられているほど劇的に綴字の標準化を推進したわけではない.続く16世紀にかけても,標準化への潮流は緩やかにみられたが,それほど著しい「もがき」は感じられない.しかし,17世紀に入ると,印刷業者というよりはむしろ正音学者や教師の働きにより,標準的綴字が広範囲に展開することになった.1650年頃には事実上の標準化が達せられていたが,より意識的な「理性化」の段階に進んだのは理性の時代たる18世紀のことである.そして,Johnson の Dictionary (1755) が,これにだめ押しを加えた.それぞれ詳しくは,本記事末尾に付したリンク先や cat:spelling standardisation を参照されたい.

この緩慢とした綴字標準化の潮流を理解すべく,安井・久保田 (73) は幅広く先行研究に目を配った.16世紀以降のつづり字改革,印刷の普及,つづり字指南書の出版の歴史などを概観しながら,「?世紀半ば」というチェックポイントを設けつつ,以下のように分かりやすく要約している.

つづり字安定への地盤はすでに16世紀半ばころから見えはじめ,17世紀半ばごろには,確たる標準はなくとも,何か中心的な,つづり字統一への核ともいうべきものが生じはじめており,これが17世紀の末ごろまでにはしだいに純化され固定されて単一化の傾向をたどり,すでに Johnson's Dictionary におけるのとあまり違わないつづり字習慣が行われていたといえるだろう.

この問題を真に理解したと言うためには,チェックポイントとなる各時代の文献に読み慣れ,共時的感覚として標準化の程度を把握できるようでなければならないのだろう.

・ 「#193. 15世紀 Chancery Standard の through の異綴りは14通り」 ([2009-11-06-1])

・ 「#297. 印刷術の導入は英語の標準化を推進したか否か」 ([2010-02-18-1])

・ 「#871. 印刷術の発明がすぐには綴字の固定化に結びつかなかった理由」 ([2011-09-15-1])

・ 「#1312. 印刷術の発明がすぐには綴字の固定化に結びつかなかった理由 (2)」 ([2012-11-29-1])

・ 「#1384. 綴字の標準化に貢献したのは17世紀の理論言語学者と教師」 ([2013-02-09-1])

・ 「#1385. Caxton が綴字標準化に貢献しなかったと考えられる根拠」 ([2013-02-10-1])

・ 安井 稔・久保田 正人 『知っておきたい英語の歴史』 開拓社,2014年.

2015-09-03 Thu

■ #2320. 17世紀中の thou の衰退 [honorific][politeness][personal_pronoun][t/v_distinction][emode][pragmatics]

英語史における thou と you の使い分け,いわゆる T/V distinction の問題については,「#1126. ヨーロッパの主要言語における T/V distinction の起源」 ([2012-05-27-1]) や「#1127. なぜ thou ではなく you が一般化したか?」 ([2012-05-28-1]),そして t/v_distinction の各記事で取り上げてきた.

2人称複数代名詞の敬称単数としての用法の伝統は,4世紀のローマ皇帝に対する vos の使用に始まり,12世紀の Chrétien de Troyes などによるフランス語を経て,英語へはおそらく13世紀に伝わり,1600年頃には慣用として根付いていた.一方,17世紀中に親称単数の thou は衰退し始め,標準英語では18世紀に廃用となった.Johnson (261) が,上記の歴史的経緯を実に手際よくまとめているので,そのまま引用したい.

IN LATIN THE EMPEROR, representing in his person the power and glory of his predecessors, was addressed with vos in the fourth century A.D. By the fifth century, this pronoun was commonly employed to indicate respect. In French by the time of Chrétien de Troyes, vous was not only given to superiors but was also interchanged by equals. In Latin and French works of twelfth-century England, the plural pronoun had been used as a singular by, for example, Geoffrey of Monmouth, Wace, and Marie de France. The practice of using ye and you (the "you-singular") instead of thou and thee (the "thou-singular") apparently spread to English during the thirteenth century and by about 1600 had become established in polite usage. For some time thereafter, however, the thou-singular continued to appear in emotional or intimate speech and in the discourse of superiors to inferiors and of the members of the lower class to one another. Gradually decreasing in use, it became obsolete in the standard language in the eighteenth century and now appears only in poetry and the address of the deity or among Quakers and those who speak a dialect.

Johnson は,thou の衰退する17世紀に焦点を当て,喜劇の戯曲と大衆フィクションの47作品をコーパスとして,you と thou の分布と頻度を調査した.登場人物を職業別に上流,中流,下流へ分類し,以下のような統計結果を得た (Johnson 265).

| 1600--1649 | You | Thou | You* | Thou* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Class | 5,851 | 2,664 | 64.36 | 35.64 |

| Middle Class | 2,807 | 629 | 81.40 | 18.60 |

| Lower Class | 2,385 | 470 | 83.47 | 16.53 |

| 1650--1699 | ||||

| Upper Class | 10,853 | 2,353 | 81.40 | 18.60 |

| Middle Class | 3,145 | 574 | 81.77 | 18.23 |

| Lower Class | 2,849 | 317 | 88.32 | 11.68 |

| * In percent. |

17世紀前半の上流階級にあっては多少の使い分けが残っているが,他の階級,あるいは少なくとも世紀の後半には thou の使用は目立たなくなっている.この段階で使い分けがなくなったというのは性急であり,伝統的な語用論的な機微がいまだ残っている例も確かに散見されるが,一方で特別な機微の感じられない you や thou の用法もあることから,両者の機能的な対立が解消しつつあったことが推測される.Johnson (266) 曰く,

The historical uses of the you-singular, as in respect or irony, and of the thou-singular, as in emotion or intimacy, to an inferior, or in the exchange of the members of the lower class, are exemplified in the various texts throughout the era. However, further demonstrating the meaninglessness of the distinction between them, you may frequently be found in circumstances where thou might be expected to occur, and, at times, thou where we should expect to find you.

・ Johnson, Anne Carvey. "The Pronoun of Direct Address in Seventeenth-Century English." American Speech 41 (1966): 261--69.

2015-08-03 Mon

■ #2289. 命令文に主語が現われない件 [imperative][syntax][pragmatics][sociolinguistics][politeness][historical_pragmatics][emode][speech_act]

標題は,長らく気になっている疑問である.現代英語の命令文では通常,主語代名詞 you が省略される.指示対象を明確にしたり,強調のために you が補われることはあるにせよ,典型的には省略するのがルールである.これは古英語でも中英語でも同じだ.

共時的には様々な考え方があるだろう.命令文で主語代名詞を補うと,平叙文との統語的な区別が失われるということがあるかもしれない.これは,命令形と2人称単数直説法現在形が同じ形態をもつこととも関連する(ただし古英語では2人称単数に対しては,命令形と直説法現在形は異なるのが普通であり,形態的に区別されていた).統語理論ではどのように扱われているのだろうか.残念ながら,私は寡聞にして知らない.

語用論的な議論もあるだろう.例えば,命令する対象は2人称であることは自明であるから,命令文において主語を顕在化する必要がないという説明も可能かもしれない.社会語用論の観点からは,東 (125) は「英語は主語をふつう省略しない言語だが,命令文の時だけは省略する.この主語(そして命令された人も)を省略する文法は,ポライトネス・ストラテジーのあらわれだといえよう」と述べている.関連して,東は,命令文以外でも you ではなく一般人称代名詞 one を用いる方がはるかに丁寧であるとも述べており,命令文での主語省略を negative politeness の観点から説明するのに理論的な一貫性があることは確かである.

しかし,ポライトネスによる説明は,現代英語の共時的な説明にとどまっているとみなすべきかもしれない.というのは,初期近代英語では,主語代名詞を添える命令文のほうがより丁寧だったという指摘があるからだ.Fennell (165) 曰く,". . . in Early Modern English constructions such as Go you, Take thou were possible and appear to have been more polite than imperatives without pronouns."

初期近代英語の命令や依頼という言語行為に関連するポライトネス・ストラテジーとしては,I pray you, Prithee, I do require that, I do beseech you, so please your lordship, I entreat you, If you will give me leave など様々なものが存在し,現代に連なる please も17世紀に誕生した.ポライトネスの意識が様々に反映されたこの時代に,むしろ主語付き命令文がそのストラテジーの1つとして機能した可能性があるということは興味深い.上記の東による説明は,よくても現代英語の主語省略を共時的に説明するにとどまり,通時的な有効性はもたないだろう.

この問題については,今後も考えていきたい.

・ Fennell, Barbara A. A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001.

・ 東 照二 『社会言語学入門 改訂版』,研究社,2009年.

2015-07-28 Tue

■ #2283. Shakespeare のラテン語借用語彙の残存率 [shakespeare][inkhorn_term][loan_word][lexicology][emode][renaissance][latin][greek]

初期近代英語期のラテン語やギリシア語からの語彙借用は,現代から振り返ってみると,ある種の実験だった.「#45. 英語語彙にまつわる数値」 ([2009-06-12-1]) で見た通り,16世紀に限っても13000語ほどが借用され,その半分以上の約7000語がラテン語からである.この時期の語彙借用については,以下の記事やインク壺語 (inkhorn_term) に関連するその他の記事でも再三取り上げてきた.

・ 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1])

・ 「#1409. 生き残ったインク壺語,消えたインク壺語」 ([2013-03-06-1])

・ 「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1])

・ 「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1])

16世紀後半を代表する劇作家といえば Shakespeare だが,Shakespeare の語彙借用は,上記の初期近代英語期の語彙借用の全体的な事情に照らしてどのように位置づけられるだろうか.Crystal (63) は,Shakespeare において初出する語彙について,次のように述べている.

LEXICAL FIRSTS

・ There are many words first recorded in Shakespeare which have survived into Modern English. Some examples:

accommodation, assassination, barefaced, countless, courtship, dislocate, dwindle, eventful, fancy-free, lack-lustre, laughable, premeditated, submerged

・ There are also many words first recorded in Shakespeare which have not survived. About a third of all his Latinate neologisms fall into this category. Some examples:

abruption, appertainments, cadent, exsufflicate, persistive, protractive, questrist, soilure, tortive, ungenitured, unplausive, vastidity

特に上の引用の第2項が注目に値する.Shakespeare の初出ラテン借用語彙に関して,その3分の1が現代英語へ受け継がれなかったという事実が指摘されている.[2010-08-18-1]の記事で触れたように,この時期のラテン借用語彙の半分ほどしか後世に伝わらなかったということが一方で言われているので,対応する Shakespeare のラテン語借用語彙が3分の2の確率で残存したということであれば,Shakespeare は時代の平均値よりも高く現代語彙に貢献していることになる.

しかし,この Shakespeare に関する残存率の相対的な高さは,いったい何を意味するのだろうか.それは,Shakespeare の語彙選択眼について何かを示唆するものなのか.あるいは,時代の平均値との差は,誤差の範囲内なのだろうか.ここには語彙の数え方という方法論上の問題も関わってくるだろうし,作家別,作品別の統計値などと比較する必要もあるだろう.このような統計値は興味深いが,それが何を意味するか慎重に評価しなければならない.

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2015-03-23 Mon

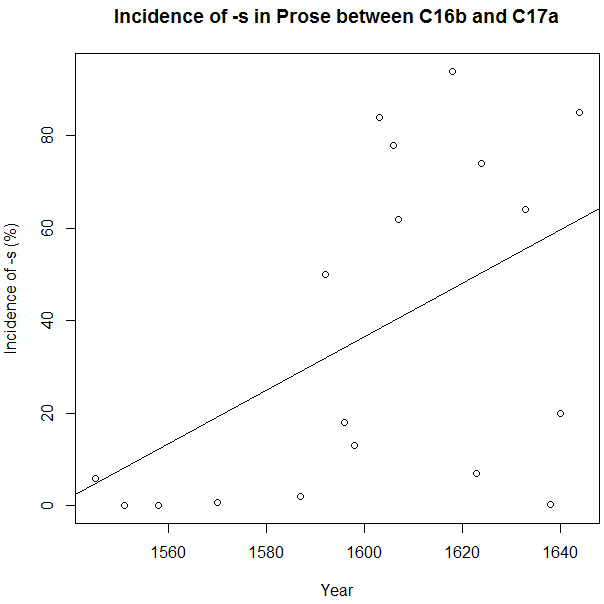

■ #2156. C16b--C17a の3単現の -th → -s の変化 [verb][conjugation][emode][language_change][suffix][inflection][3sp][lexical_diffusion][schedule_of_language_change][speed_of_change][bible]

初期近代英語における動詞現在人称語尾 -th → -s の変化については,「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]),「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]),「#1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力」 ([2014-05-28-1]),「#2141. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の概要」 ([2015-03-08-1]) などで取り上げてきた.今回,この問題に関連して Bambas の論文を読んだ.現在の最新の研究成果を反映しているわけではないかもしれないが,要点が非常によくまとまっている.

英語史では,1600年辺りの状況として The Authorised Version で不自然にも3単現の -s が皆無であることがしばしば話題にされる.Bacon の The New Atlantis (1627) にも -s が見当たらないことが知られている.ここから,当時,文学的散文では -s は口語的にすぎるとして避けられるのが普通だったのではないかという推測が立つ.現に Jespersen (19) はそのような意見である.

Contemporary prose, at any rate in its higher forms, has generally -th'; the s-ending is not at all found in the A[uthorized] V[ersion], nor in Bacon A[tlantis] (though in Bacon E[ssays] there are some s'es). The conclusion with regard to Elizabethan usage as a whole seems to be that the form in s was a colloquialism and as such was allowed in poetry and especially in the drama. This s must, however, be considered a licence wherever it occurs in the higher literature of that period. (qtd in Bambas, p. 183)

しかし,Bambas (183) によれば,エリザベス朝の散文作家のテキストを広く調査してみると,実際には1590年代までには文学的散文においても -s は容認されており,忌避されている様子はない.その後も,個人によって程度の違いは大きいものの,-s が避けられたと考える理由はないという.Jespersen の見解は,-s の過小評価であると.

The fact seems to be that by the 1590's the -s-form was fully acceptable in literary prose usage, and the varying frequency of the occurrence of the new form was thereafter a matter of the individual writer's whim or habit rather than of deliberate selection.

さて,17世紀に入ると -th は -s に取って代わられて稀になっていったと言われる.Wyld (333--34) 曰く,

From the beginning of the seventeenth century the 3rd Singular Present nearly always ends in -s in all kinds of prose writing except in the stateliest and most lofty. Evidently the translators of the Authorized Version of the Bible regarded -s as belonging only to familiar speech, but the exclusive use of -eth here, and in every edition of the Prayer Book, may be partly due to the tradition set by the earlier biblical translations and the early editions of the Prayer Book respectively. Except in liturgical prose, then, -eth becomes more and more uncommon after the beginning of the seventeenth century; it is the survival of this and not the recurrence of -s which is henceforth noteworthy. (qtd in Bambas, p. 185)

だが,Bambas はこれにも異議を唱える.Wyld の見解は,-eth の過小評価であると.つまるところ Bambas は,1600年を挟んだ数十年の間,-s と -th は全般的には前者が後者を置換するという流れではあるが,両者並存の時代とみるのが適切であるという意見だ.この意見を支えるのは,Bambas 自身が行った16世紀半ばから17世紀半ばにかけての散文による調査結果である.Bambas (186) の表を再現しよう.

| Author | Title | Date | Incidence of -s |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascham, Roger | Toxophilus | 1545 | 6% |

| Robynson, Ralph | More's Utopia | 1551 | 0% |

| Knox, John | The First Blast of the Trumpet | 1558 | 0% |

| Ascham, Roger | The Scholmaster | 1570 | 0.7% |

| Underdowne, Thomas | Heriodorus's Anaethiopean Historie | 1587 | 2% |

| Greene, Robert | Groats-Worth of Witte; Repentance of Robert Greene; Blacke Bookes Messenger | 1592 | 50% |

| Nashe, Thomas | Pierce Penilesse | 1592 | 50% |

| Spenser, Edmund | A Veue of the Present State of Ireland | 1596 | 18% |

| Meres, Francis | Poetric | 1598 | 13% |

| Dekker, Thomas | The Wonderfull Yeare 1603 | 1603 | 84% |

| Dekker, Thomas | The Seuen Deadlie Sinns of London | 1606 | 78% |

| Daniel, Samuel | The Defence of Ryme | 1607 | 62% |

| Daniel, Samuel | The Collection of the History of England | 1612--18 | 94% |

| Drummond of Hawlhornden, W. | A Cypress Grove | 1623 | 7% |

| Donne, John | Devotions | 1624 | 74% |

| Donne, John | Ivvenilia | 1633 | 64% |

| Fuller, Thomas | A Historie of the Holy Warre | 1638 | 0.4% |

| Jonson, Ben | The English Grammar | 1640 | 20% |

| Milton, John | Areopagitica | 1644 | 85% |

これをプロットすると,以下の通りになる.

この期間では年間0.5789%の率で上昇していることになる.相関係数は0.49である.全体としては右肩上がりに違いないが,個々のばらつきは相当にある.このことを過小評価も過大評価もすべきではない,というのが Bambas の結論だろう.

・ Bambas, Rudolph C. "Verb Forms in -s and -th in Early Modern English Prose". Journal of English and Germanic Philology 46 (1947): 183--87.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

・ Wyld, Henry Cecil. A History of Modern Colloquial English. 2nd ed. London: Fisher Unwin, 1921.

2015-03-12 Thu

■ #2145. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (6) [verb][conjugation][emode][number][agreement][3pp][nptr]

標題については 3pp の各記事で取り上げてきたが,関連する記述をもう1つ見つけたので,以下に記しておきたい.「#1301. Gramley の英語史概説書のコンパニオンサイト」 ([2012-11-18-1]) と「#2007. Gramley の英語史概説書の目次」 ([2014-10-25-1]) で紹介した Gramley (136--37) からの引用である.

Third person {-s} vs. {-(e)th} is a further inflectional point. This distinction is one of the most noticeable in this period [EModE], and it may be used as evidence of the influence of Northern on Southern English. In ME Northerners used the ending {-s} where Southerners used {-(e)th}. In each case the respective inflection could be used in both the third person singular present tense as well as in the whole of the plural . . . . While zero became normal in the plural, in the third person singular present tense there was no such move, and the two forms were in competition with each other both in colloquial London speech and in the written language.

同英語史書のコンパニオンサイトより,6章のための補足資料 (p. 8) に,さらに詳しい解説が載っており有用である.また,そこでは Northern Subject Rule (= Northern Present Tense Rule; cf. nptr, 「#689. Northern Personal Pronoun Rule と英文法におけるケルト語の影響」 ([2011-03-17-1])) にも触れられており,その関連で Lass (166, 185) と Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg (283, 312) への言及もある.

NPTR が南部において適用された結果と思われる複現の -s の例を挙げておこう.

・ they laugh that wins (F1--3, Q1--3; win F4) (Shakespeare, Othello 4.1.121)

・ whereby they make their pottage fat, and therewith driues out the rest with more content. (Deloney, Jack of Newbury 72)

・ For if neither they can doo that they promise & wantes greatest good (Elizabeth, Boethius 48.11)

・ Well know they what they speak that speaks (F1; speak Q) so wisely (Shakespeare, Troilus 3.2.145)

・ when sorrows comes (F1), they come not single spies. (Shakespeare, Hamlet 4.5.73)

・ As surely as your feet hits (F1) the ground they step on (Shakespeare, Twelfth Night 3.4.265)

Shakespeare では版によって複現の -s が現われたり消えたりする例が見られることから,そこには文体的あるいは通時的な含意がありそうである.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 56--186.

・ Nevalainen, T. and H. Raumolin-Brunberg. "The Changing Role of London on the Linguistic Map of Tudor and Stuart England." The History of English in a Social Context: A Contribution to Historical Sociolinguistics. Ed. D. Kastovsky and A. Mettinger. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2000. 279--337.

2015-03-08 Sun

■ #2141. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の概要 [verb][conjugation][emode][language_change][suffix][inflection][3sp][bible][shakespeare][schedule_of_language_change]

「#1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力」 ([2014-05-28-1]) でみたように,17世紀中に3単現の屈折語尾が -th から -s へと置き換わっていった.今回は,その前の時代から進行していた置換の経緯を少し紹介しよう.

古英語後期より北部方言で行なわれていた3単現の -s を別にすれば,中英語の南部で -s が初めて現われたのは14世紀のロンドンのテキストにおいてである.しかし,当時はまだ稀だった.15世紀中に徐々に頻度を増したが,爆発的に増えたのは16--17世紀にかけてである.とりわけ口語を反映しているようなテキストにおいて,生起頻度が高まっていったようだ.-s は,およそ1600年までに標準となっていたと思われるが,16世紀のテキストには相当の揺れがみられるのも事実である.古い -th は母音を伴って -eth として音節を構成したが,-s は音節を構成しなかったため,両者は韻律上の目的で使い分けられた形跡がある (ex. that hateth thee and hates us all) .例えば,Shakespeare では散文ではほとんど -s が用いられているが,韻文では -th も生起する.とはいえ,両形の相対頻度は,韻律的要因や文体的要因以上に個人または作品の性格に依存することも多く,一概に論じることはできない.ただし,doth や hath など頻度の非常に高い語について,古形がしばらく優勢であり続け,-s 化が大幅に遅れたということは,全体的な特徴の1つとして銘記したい.

Lass (162--65) は,置換のスケジュールについて次のように要約している.

In the earlier sixteenth century {-s} was probably informal, and {-th} neutral and/or elevated; by the 1580s {-s} was most likely the spoken norm, with {-eth} a metrical variant.

宇賀治 (217--18) により作家や作品別に見てみると,The Authorised Version (1611) や Bacon の The New Atlantis (1627) には -s が見当たらないが,反対に Milton (1608--74) では doth と hath を別にすれば -th が見当たらない.Shakespeare では,Julius Caesar (1599) の分布に限ってみると,-s の生起比率が do と have ではそれぞれ 11.76%, 8.11% だが,それ以外の一般の動詞では 95.65% と圧倒している.

とりわけ16--17世紀の証拠に基づいた議論において注意すべきは,「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]) で見たように,表記上 -th とあったとしても,それがすでに [s] と発音されていた可能性があるということである.

置換のスケジュールについては,「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 56--186.

・ 宇賀治 正朋 『英語史』 開拓社,2000年.

2015-01-19 Mon

■ #2093. <gauge> vs <gage> [spelling][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap][eebo][clmet][emode][lmode][coha][ame_bre][spelling_pronunciation]

「#2088. gauge の綴字と発音」 ([2015-01-14-1]) を受けて,<gauge> vs <gage> の異綴字の分布について歴史的に調べてみる.まずは,初期近代英語の揺れの状況を,EEBO (Early English Books Online) に基づいたテキスト・データベースにより見てみよう

| Period (subcorpus size) | <gage> etc. | <gauge> etc. |

|---|---|---|

| 1451--1500 (244,602 words) | 0 wpm (0 times) | 0 wpm (0 times) |

| 1501--1550 (328,7691 words) | 3.35 (11) | 0.00 (0) |

| 1551--1600 (13,166,673 words) | 6.84 (90) | 0.076 (1) |

| 1601--1650 (48,784,537 words) | 3.01 (147) | 0.35 (17) |

| 1651--1700 (83,777,910 words) | 0.060 (5) | 0.19 (5) |

| 1701--1750 (90,945 words) | 0.00 (0) | 0.00 (0) |

17世紀に <gauge> 系が少々生起するくらいで,初期近代英語の基本綴字は <gage> とみてよいだろう.次に,18世紀以後の後期近代英語に関しては,CLMET3.0 を利用して検索した.

| Period (subcorpus size) | <gage> etc. | <gauge> etc. |

|---|---|---|

| 1710--1780 (10,480,431 words) | 5 | 1 |

| 1780--1850 (11,285,587) | 19 | 20 |

| 1850--1920 (12,620,207) | 2 | 49 |

おそらく1800年くらいを境に,それまで非主流派だった <gauge> が <gage> に肉薄し始め,19世紀中には追い抜いていったという流れが想定される.現代英語では BNCweb で調べる限り <gauge> が圧倒しているから,20世紀中もこの流れが推し進められたものと考えられそうだ.

一方,<gage> の使用も多いといわれるアメリカ英語について COHA で調べてみると,実際のところ現代的には <gauge> のほうが圧倒的に優勢であるし,歴史的にも <gauge> が20世紀を通じて堅調に割合を伸ばしてきたことがわかる.あくまで,現代アメリカ英語では <gage> 「も」使われることがあるというのが実態のようだ.この事実は,「#1739. AmE-BrE Diachronic Frequency Comparer」 ([2014-01-30-1]) により "(?-i)\bgau?g(e|es|ed|ings?)\b" として検索をかけて得られる以下の表からも示唆される.いずれの変種でも <gauge> 系は見られるものの,<gage> 系についてはイギリス英語ではゼロ,アメリカ英語では部分的に使用されるという違いがある.

| ID | WORD | 1961 | 1991--92 | ca 2006 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown (AmE) | LOB (BrE) | Frown (AmE) | FLOB (BrE) | AmE06 (AmE) | BE06 (BrE) | ||

| 1 | gage | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | gages | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | gaging | 1 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | gauge | 16 | 15 | 10 | 6 | 16 | 21 |

| 5 | gauged | 2 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 | gauges | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 7 | gauging | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |