2024-04-05 Fri

■ #5457. 主語をめぐる論点 [subject][terminology][semantics][syntax][logic][existential_sentence][construction][agreement][number][expletive]

昨日の記事「#5456. 主語とは何か?」 ([2024-04-04-1]) に引き続き,主語 (subject) についての本質的な疑問に迫りたい.この問題を論じるに際し,まず用語辞典などに当たってみるのが良さそうだ.McArthur の項目を引用しよう.主要な論点が見えてくる.

SUBJECT [13c: from Latin subjectum grammatical subject, from subiectus placed close, ranged under]. A traditional term for a major constituent of the sentence. In a binary analysis derived from logic, the sentence is divided into subject and predicate, as in Alan (subject) has married Nita (predicate). In declarative sentences, the subject typically precedes the verb: Alan (subject) has married (verb) Nita (direct object). In interrogative sentences, it typically follows the first or only part of the verb: Did (verb) Alan (subject) marry (verb) Nita (direct object)? The subject can generally be elicited in response to a question that puts who or what before the verb: Who has married Nita?---Alan. Where concord is relevant, the subject determines the number and person of the verb: The student is complaining/The students are complaining; I am tired/He is tired. Many languages have special case forms for words in the subject, the subject requires a particular form (the subjective) in certain pronouns: I (subject) like her, and she (subject) likes me.

Kinds of subject. A distinction is sometimes made between the grammatical subject (as characterized above), the psychological subject, and the logical subject: (1) The psychological subject is the theme or topic of the sentence, what the sentence is about, and the predicate is what is said about the topic. The grammatical and psychological subjects typically coincide, though the identification of the sentence topic is not always clear: Labour and Conservative MPs clashed angrily yesterday over the poll tax. Is the topic of the sentence the MPs or the poll tax? (2) The logical subject refers to the agent of the action; our children is the logical subject in both these sentences, although it is the grammatical subject in only the first: Our children planted the oak sapling; The oak sapling was planted by our children. Many sentences, however, have no agent: Stanley has back trouble; Sheila is a conscientious student; Jenny likes jazz; There's no alternative; It's raining

Pseudo-subjects. The last sentence also illustrates the absence of a psychological subject, since it is obviously not the topic of the sentence. This so-called 'prop it' is a dummy subject, serving merely to fill a structural need in English for a subject in a sentence. In this respect, English contrasts with languages such as Latin, which can omit the subject, as in Veni, vidi, vici (I came, I saw, I conquered: with no need for the Latin pronoun ego, I). Like prop it, 'existential there' in There's no alternative is the grammatical subject of the sentence, but introduces neither the topic nor (since there is no action) the agent.

Non-typical subjects. Subjects are typically noun phrases, but they may also be finite and non-finite clauses: 'That nobody understands me is obvious'; 'To accuse them of negligence was a serious mistake'; 'Looking after the garden takes me several hours a week in the summer.' In such instances, finite and infinitive clauses are commonly post and anticipatory it takes their place in subject position: 'It is obvious that nobody understands me'; 'It was a serious mistake to accuse them of negligence.' Occasionally, prepositional phrases and adverbs function as subjects: 'After lunch is best for me'; 'Gently does it.'

Subjectless sentences. Subjects are usually omitted in imperatives, as in Come here rather than You come here. They are often absent from non-finite clauses ('Identifying the rioters may take us some time') and from verbless clauses ('New filters will be sent to you when available'), and may be omitted in certain contexts, especially in informal notes (Hope to see you soon) and in coordination (The telescope is 43 ft long, weighs almost 11 tonnes, and is more than six years late).

項目の書き出しは標準的といってよく,おおよそ文法的な観点から主語の概念が導入されている.主部・述部の区別に始まり,主語の統語論的振る舞いや形態論的性質が紹介される.

次の節では,主語が文法的な観点のみならず心理的,論理的な観点からもとらえられるとして,別のアングルが提供される.心理的な観点からは「テーマ,主題」,論理的な観点からは「動作の行為者」に対応するのが主語なのだと説かれる.現実の文に当てはめてみると,3つの観点からの主語が必ずしも互いに一致しないことが示される.

続けて,擬似的な主語,いわゆる形式主語やダミーの主語と呼ばれるものが紹介される.そこでは there is の存在文 (existential_sentence) も言及される.この構文では there はテーマではありえないし,動作の行為者でもないので,あくまで文法形式のために要求されている主語とみなすほかない.

通常,主語は名詞句だが,それ以外の統語カテゴリーも主語として立ちうるという話題が導入されたあと,最後に主語がない(あるいは省略されている)節の例が示される.

ほかにも様々に論点は挙げられそうだが,今回は手始めにここまで.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

2024-04-04 Thu

■ #5456. 主語とは何か? [subject][terminology][semantics][syntax][logic][existential_sentence][inohota][youtube][voicy][heldio][construction][agreement][number][link]

3月31日に配信した YouTube 「いのほた言語学チャンネル」の第219回は,「古い文法・新しい文法 There is 構文まるわかり」と題してお話ししています.本チャンネルとしては,この4日間で視聴回数3100回越えとなり,比較的多く視聴されているようです.ありがとうございます.

There is a book on the desk. のような存在文 (existential_sentence) における there は,意味的には空疎ですが,文法的には主語であるかのような振る舞いを示します.一方,a book は何の役割をはたしているかと問われれば,これこそが主語であると論じることもできます.さらに be 動詞と数の一致を示す点でも,a book のほうが主語らしいのではないかと議論できそうです.

これまで当たり前のように受け入れてきた主語 (subject) とは,いったい何なのでしょうか.考え始めると頭がぐるぐるしてきます.存在文の主語の問題,および「主語」という用語に関しては,heldio でも取り上げてきました.

・ 「#1003. There is an apple on the table. --- 主語はどれ?」

・ 「#1032. なぜ subject が「主語」? --- 「ゆる言語学ラジオ」からのインスピレーション」

もちろんこの hellog でも,存在文に関連する話題は以下の記事で取り上げてきました.

・ 「#1565. existential there の起源 (1)」 ([2013-08-09-1])

・ 「#1566. existential there の起源 (2)」 ([2013-08-10-1])

・ 「#4473. 存在文における形式上の主語と意味上の主語」 ([2021-07-26-1])

主語とは何か? 簡単に解決する問題ではありませんが,ぜひ皆さんにも考えていただければ.

2024-03-19 Tue

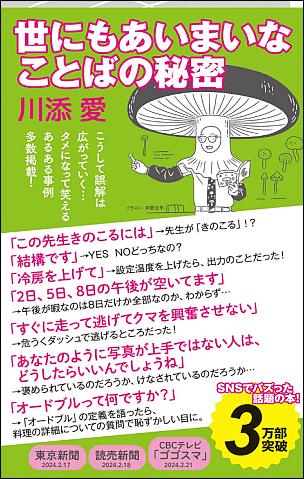

■ #5440. 川添愛(著)『世にもあいまいなことばの秘密』(筑摩書房〈ちくまプリマー新書〉,2023年) [review][toc][syntax][semantics][pragmatics][youtube][inohota][notice]

昨年12月に出版された,川添愛さんによる言葉をおもしろがる新著.表紙と帯を一目見るだけで,読んでみたくなる本です.くすっと笑ってしまう日本語の用例を豊富に挙げながら,ことばの曖昧性に焦点を当てています.読みやすい口調ながらも,実は言語学的な観点から言語学上の諸問題を論じており,(物書きの目線からみても)書けそうで書けないタイプの希有の本となっています.

どのような事例が話題とされているのか,章レベルの見出しを掲げてみましょう.

1. 「シャーク関口ギターソロ教室」 --- 表記の曖昧さ

2. 「OKです」「結構です」 --- 辞書に載っている曖昧さ

3. 「冷房を上げてください」 --- 普通名詞の曖昧さ

4. 「私には双子の妹がいます」 --- 修飾語と名詞の関係

5. 「政府の女性を応援する政策」 --- 構造的な曖昧さ

6. 「二日,五日,八日の午後が空いています」 --- やっかいな並列

7. 「二〇歳未満ではありませんか」 --- 否定文・疑問文の曖昧さ

8. 「自分はそれですね」 --- 代名詞の曖昧さ

9. 「なるはやでお願いします」 --- 言外の意味と不明確性

10. 「曖昧さとうまく付き合うために」

言語学的な観点からは,とりわけ統語構造への注目が際立っています.等位接続詞がつなげている要素は何と何か,否定のスコープはどこまでか,形容詞が何にかかるのか,助詞「の」の多義性,統語的解釈における句読点の役割等々.ほかに語用論的前提や意味論的曖昧性の話題も取り上げられています.

本書は日本語を読み書きする際に注意すべき点をまとめた本としては,実用的な日本語の書き方・話し方マニュアルとして読むこともできると思います.むしろ実用的な関心から本書を手に取ってみたら,言語学的見方のおもしろさがジワジワと分かってきた,というような読まれ方が想定されているのかもしれません.曖昧性の各事例については「問題」と「解答」(巻末)が付されています.

本書のもう1つの読み方は,例に挙げられている日本語の事例を英語にしたらどうなるか,英語だったらどのように表現するだろうか,などと考えながら読み進めることによって,両言語の言語としての行き方の違いに気づくというような読み方です.両言語間の翻訳の練習にもなりそうです.

本書については YouTube 「いのほた言語学チャンネル」にて「#205. 川添愛さん『世にもあいまいなことばの秘密』のご紹介」の回で取り上げています.ぜひご覧ください.

言語の曖昧性については hellog より「#2278. 意味の曖昧性」 ([2015-07-23-1]),「#4913. 両義性にもいろいろある --- 統語的両義性から語彙的両義性まで」 ([2022-10-09-1]) の記事もご一読ください.

・ 川添 愛 『世にもあいまいなことばの秘密』 筑摩書房〈ちくまプリマー新書〉,2023年.

2024-03-18 Mon

■ #5439. 英語辞書から集めた tautology (類語反復,トートロジー)の事例 [tautology][voicy][heldio][rhetoric][logic][pragmatics][semantics][khelf][aokikun][word_play][periphrasis]

今朝の Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」の配信回は「#1022. トートロジー --- khelf 会長,青木くんの研究テーマ」です.言語における tautology とは何か? "A is A" のような一見無意味な形式がなぜ存在し,なぜしばしば有意味となり得るのか? この問題については,khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)会長の青木輝さんとともに今後ゆっくりと検討していく予定ですが,今回はその頭出しという趣旨での配信でした.ぜひお聴きいただければ.

トートロジーについては,hellog では「#4851. tautology」 ([2022-08-08-1]) としてすでに導入しています.今回は英語辞書から英語のトートロジーの事例をいくつか集めてみました.

・ a beginner who has just started

・ free gift

・ He lives alone by himself.

・ hear with one's ears

・ helpful assistance

・ necessary essentials

・ new innovation

・ real truth

・ She is dumb and can not speak.

・ speak all at once together

・ the modern university of today

・ The money should be adequate enough.

・ They spoke in turn, one after the other.

・ This candidate will win or not win.

・ very excellent

・ widow woman

論理,意味,語用,形式などの観点から様々に分類できそうです.ものによっては periphrasis (迂言法),pleonasm (冗語法),redundancy (冗長),repetition (繰り返し)などと呼び変えるほうが適切な事例もありそうです.また,言葉遊び (word_play) とも関係してきそうです.

言語によってトートロジーの種類は異なるのか? 個別言語におけるトートロジーの起源と発達は? トートロジーの言語的機能は? 謎が謎を呼ぶ,深掘りしがいのあるテーマです.

2024-02-23 Fri

■ #5415. 語彙記載項 (lexical entry) には何が記載されているか? [lexicon][lexicography][lexicology][semantics][dictionary][orthography][etymology]

私たちが普段使う英語辞書や日本語辞書などでは,見出し語のもとにどのような情報が記載されているだろうか.見出し語それ自体は,アルファベット順あるいは五十音順に並べられた上で,各語が正書法に則った文字列で掲げられているのが普通だろう.その後に発音(分節音や超分節音)の情報が記載されていることが多い.その後,品詞や各種の文法情報が示され,語義・定義が1つ以上列挙されるのが典型である.エントリーの末尾には,語法,派生語・関連語,語源,その他の注などが付されている辞書もあるだろう.個別の辞書 (dictionary) ごとに,詳細は異なるだろうが,おおよそこのようなレイアウトである.

では,私たち言語話者の頭の中にある辞書 (lexicon) は,どのように整理されており,各語の項目,すなわち語彙記載項 (lexical entry) にはどんな情報が「記載」されているのだろうか.これは,語彙論や意味論の理論的な問題である.

まず,語彙項目の並びがアルファベット順や五十音順ではないだろうことは直感される.また,文字を読み書きできない修学前の子供たちの頭の中の語彙記載項目には,正書法の情報は入っていないだろう.さらに(私などのように)特別に語源に関心のある話者でない限り,頭の中の語彙記載項に「語順欄」のような通時的なコーナーが設定されているとは考えにくい.

しかし,発音,品詞や各種の文法情報,語義については,紙の辞書 (dictionary) とは異なる形かとは予想されるが,何らかのフォーマットで頭の中の辞書にも「記載」されていると考えられる.では,具体的にどんなフォーマットなのだろうか.

これは語彙論や意味論の分野の理論的問題であり.これぞという定説や決定版が提案されているわけではない.直接頭の中を覗いてみるわけにはいかないからだ.ただし,大雑把な合意があることも確かだ.英語の単語で考える限り,例えば,Bauer (192--93) は,Lyons を参照し,他のいくつかの先行研究にも目配りしつつ,次の4項目を挙げている.

(i) stem(s)

(ii) inflectional class

(iii) syntactic properties

(iv) semantic specification(s)

(i) は stem(s) (語幹)とあるが,言わんとしていることは音韻論(分節音・超分節音)の情報のことである.(ii) は形態論的情報,(iii) は統語論的情報,(iv) は意味論的情報である.最後の項目は,多義の場合には「複数行」にわたるだろう.

理論言語学の見地からは,ここに正書法欄や語源欄の入る余地はないのだろう.認めざるを得ないが,文字と語源を愛でる歴史言語学者にとって,ちょっと寂しいところではある.

・ Bauer, Laurie. English Word-Formation. Cambridge: CUP, 1983.

・ Lyons, John. Semantics. Cambridge: CUP, 1977.

2023-10-21 Sat

■ #5290. 名前に意味はあるのか論争の4つの論点 [name_project][onomastics][personal_name][toponymy][semantics]

昨日の記事で取り上げた「#5289. 名前に意味はあるのか?」 ([2023-10-20-1]) について,先日大学院の授業で議論した.その際に,なぜ名前に意味があるのか否かで賛否が分かれ得るのだろうかという点を考察した.4つほど論点があるだろうと思い至ったので,ここに記録しておきたい.

1つめは,議論のベースとした Nyström でも明言されているとおり,"A crucial point is what we mean by meaning" (40) という論点がある.意味とは何かについての認識の違いにより「名前に意味はあるか」の答えも変わり得るという,きわめて自然なポイントだ.そして,これは万人の同意を得るのがきわめて難しい問題でもある(cf. 「#1782. 意味の意味」 ([2014-03-14-1])).

2つめは,上記と平行的だが,「名前とは何か」の認識の違いに関するポイントである.何をもって名前とみなすか,名前らしさとは何かという問いは,「名前プロジェクト」 (name_project) を通じて論じているところでもある.例えば,典型的な人名(本名)には意味がないと論じることができたとしても,ニックネームには明らかに意味のあるケースも多いだろう.すると,本名とニックネームを意味の有無の議論のなかで同列に扱うのは妥当なのだろうか,という疑問が湧く.

3つめは,名前からなる語彙 (onomasticon) と一般語からなる語彙(通常の lexicon)がどの程度重なり合っているかは,言語によって異なるという事情がある.例えば人名で考えると,英語の John, Tom, Mary は onomasticon には登録されているものの,lexicon には登録されていない.一方,日本語の人名の「かける」「わたる」「さくら」などは onomasticon にも lexicon にも登録されている語である.換言すれば,英日語において「名前レンマ」の位置づけが異なっているのである(cf. 「#5195. 名前レンマ (name lemma)」 ([2023-07-18-1])).いずれの言語を母語とするか,いずれに馴染みがあるかによって,「名前に意味はあるのか」への答えが偏ってくるのは自然のことかもしれない.英日語の対照について,さらに一言付け加えれば,音声に依拠するアルファベット文字体系を用いる英語(=ラジオ型言語)と,表語的な性質をもつ漢字を多用する日本語(=テレビ型言語)とでは,名前と意味の関係の捉え方は異なるだろう.

4つめに,名前の通用度,理解される範囲に関する論点がある.家族内でのみ通じるニックネームなどの人名がある一方,全世界で通じる「東京」や「ロンドン」のような地名もある.名前の意味を,その名前を聞いた人が喚起する何かだと解釈するのであれば,(極端な例ではあるが)家族内と全世界という範囲の違いは,そのまま名前の意味の通用度や有効度の差にもなる.ある個人にとっては有意味でも,他のすべての人にとっては無意味というケースがあり得るのである.すると「名前に意味はあるのか」を一般的に問うことは難しくなるだろう.

本記事をお読みの皆さんにも,ぜひ議論を続けていただければ.

・ Nyström, Staffan. "Names and Meaning." Chapter 3 of The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. Ed. Carole Hough. Oxford: OUP, 2016. 39--51.

2023-10-20 Fri

■ #5289. 名前に意味はあるのか? [name_project][onomastics][voicy][heldio][personal_name][toponymy][semantics][pragmatics]

名前学あるいは固有名詞学 (onomastics) の論争の1つに,標題の議論がある.はたして名前に意味があるのかどうか.この問題については,私も長らく考え続けてきた.「#5197. 固有名に意味はあるのか,ないのか?」 ([2023-07-20-1]) を参照されたい.(Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」のプレミアムリスナー限定配信チャンネル「英語史の輪 (helwa)」(有料)では「【英語史の輪 #15】名前に意味があるかないか論争」として議論している.)

Nyström (40--41) は,固有名詞には広い意味での「意味」があるとして,"the maxium meaningfulness thesis" に賛同している (40) .以下に Nyström の議論より,最も重要な節を引きたい.

Do names have meaning or not, that is do they have both meaning and reference or do they only have reference? This question is closely connected to the dichotomy proper name---common noun (or to use another pair of terms name--appellative) and also to the idea of names being more or less 'namelike', showing a lower or higher degree of propriality or 'nameness'. Can a certain name be a more 'namelike' name than another? I believe it can. To support such an assertion one might argue that a name is not a physical, material object. It is an abstract conception. A name is the result of a complex mental process: sometimes (when we hear or see a name) the result of an individual analysis of a string of sounds or letters, sometimes (when we produce a name) the result of a verbalization of a thought. We shall not ask ourselves what a name is but what a name does. To use a name means to start a process in the brain, a process which in turn activates our memories, fantasy, linguistic abilities, emotions, and many other things. With an approach like that, it would be counterproductive to state that names do not have meaning, that names are meaningless.

「名前とは何か」という問いよりも「名前は何をするものか」という名前の役割を問うことが重要なのではないか,というくだりには目から鱗が落ちた.この話題,これからも取り上げていければと.

・ Nyström, Staffan. "Names and Meaning." Chapter 3 of The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. Ed. Carole Hough. Oxford: OUP, 2016. 39--51.

2023-10-13 Fri

■ #5282. Jespersen の「近似複数」の指摘 [plural][number][numeral][personal_pronoun][personal_name][plural_of_approximation][semantics][pragmatics]

昨日の記事「#5281. 近似複数」 ([2023-10-12-1]) で話題にした近似複数 (plural_of_approximation) について,最初に指摘したのは Jespersen (83--85) である.この原典は読み応えがあるので,そのまま引用したい.

Plural of Approximation

4.51 The sixties (cf. 4.12) has two meanings, first the years from 60 to 69 inclusive in any century; thus Seeley E 249 the seventies and the eighties of the eighteenth century | Stedman Oxford 152 in the "Seventies" [i.e. 1870, etc.] | in the early forties = early in the forties. Second it may mean the age of any individual person, when he is sixty, 61, etc., as in Wells U 316 responsible action is begun in the early twenties . . . Men marry before the middle thirties | Children's Birthday Book 182 While I am in the ones, I can frolic all the day; but when I'm in the tens, I must get up with the lark . . . When I'm in the twenties, I'll be like sister Joe . . . When I'm in the thirties, I'll be just like Mama.

4.52. The most important instance of this plural is found in the pronouns of the first and second persons: we = I + one or more not-I's. The pl you (ye) may mean thou + thou + thou (various individuals addressed at the same time), or else thou + one or more other people not addressed at the moment; for the expressions you people, you boys, you all, to supply the want of a separate pl form of you see 2.87.

A 'normal' plural of I is only thinkable, when I is taken as a quotation-word (cf. 8.2), as in Kipl L 66 he told the tale, the I--I--I's flashing through the record as telegraph-poles fly past the traveller; cf. also the philosophical plural egos or me's, rarer I's, and the jocular verse: Here am I, my name is Forbes, Me the Master quite absorbs, Me and many other me's, In his great Thucydides.

4.53. It will be seen that the rule (given for instance in Latin grammars) that when two subjects are of different persons, the verb is in "the first person rather than the second, and in the second rather than the third" 'si tu et Tullia valetis, ego et Cicero valemus, Allen and Greenough, Lat. Gr. §317) is really superfluous, as a self-evidence consequence of the definition that "the first person plural is the first person singular plus some one else, etc." In English grammar the rule is even more superfluous, because no persons are distinguished in the plural of English verbs.

When a body of men, in response to "Who will join me?", answer "We all will", their collective answers may be said to be an ordinary plural (class 1) of I (= many I's), though each individual "we will" means really nothing more than "I will, and B and C . . . will, too" in conformity with the above definition. Similarly in a collective document: "We, the undersigned citizens of the city of . . ."

4.54. The plural we is essentially vague and in no wise indicates whom the speaker wants to include besides himself. Not even the distinction made in a great many African and other languages between one we meaning 'I and my own people, but not you', and another we meaning 'I + you (sg or pl)' is made in our class of languages. But very often the resulting ambiguity is remedied by an appositive addition; the same speaker may according to circumstances say we brothers, we doctors, we Yorkshiremen, we Europeans, we gentlemen, etc. Cf. also GE M 2.201 we people who have not been galloping. --- Cf. for 4.51 ff. PhilGr p. 191 ff.

4.55. Other examples of the pl of approximation are the Vincent Crummleses, etc. 4.42. In other languages we have still other examples, as when Latin patres many mean pater + mater, Italian zii = zio + zia, Span. hermanos = hermano(s) + hermana(s), etc.

複数形といっても,その意味論は複雑であり得る.これは,一見して形態論の話題とみえて,本質的には意味論と語用論の問題なのだと思う.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 2. Vol. 1. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: C. Winter's Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1922.

2023-08-25 Fri

■ #5233. 「言葉の宗教」 --- 『宗教学事典』より [religion][semantics][semantic_change][polysemy][register][kotodama]

「#5230. 「宗教の言葉」 --- 『宗教学事典』より」 ([2023-08-22-1]) で引用した『宗教学事典』の次の部分に,2項を逆転させた「言葉の宗教」という小見出しを掲げている文章がある (347--38) .

●言葉の宗教 他方,神の啓示を絶対的真理として受容しそれに聴従する啓示宗教---宣言型の宗教にほぼ重なる---では,神が啓示した言葉が信仰者に受容され,やがて「聖典・経典」が編纂される.それは何よりも絶対的真理が記された書であり,一切の価値判断の基準が神の絶対性に求められる以上,そこに誤謬はありえない.これが啓典の民が抱く信仰の根本にある.ユダヤ教・キリスト教・イスラームなどの一神教において,こうした聖典無謬性の主張は比較的顕著に窺えるが,ヒンドゥー教などの多神教でも,聖典の聖句に対する神聖視は容易に観察できる.聖典に対する呪物崇拝や解釈上の聖典原理主義が生まれる土壌は,言葉の宗教に本質的に内蔵されているのである.

また,超越的霊威の言葉(神の言,仏説など)が記された聖典・聖書が絶対的真理を含むのみならず,そこに書かれた聖句や聖音が絶対的価値を帯びているとみなされることもある.そのような聖音が母源となって,他の一切の音韻が派生・分岐したとみなされる場合,言葉それ自体が神格化されて,最終的には言葉が宇宙の万物を生み出す想像原理であると主張されることになる.すなわち,言葉を宇宙万物の構成要素と見る「言語宇宙論」である.一見すると,原始心性の中で培養された,理性が未発達ゆえの素朴で稚拙な言語観と受け取られる可能性が高いものである.

最後に出てくる「言語宇宙論」という壮大な言語観について,少し間をおいて次のように文章が続く (348) .

「意思伝達」に焦点を絞る限り,日常言語の働きは,①表出・②訴え・③指示・④述定にある.それは,「①誰かが,②誰かに,③何ものかについて,④何ごとかを語る」という四肢構造の枠組みで考察することができるだろう.実は,こうした「意思伝達」を暗黙の前提にした言語観の認識枠組みには収まり切らない異質な言語理解の観点が,先述の言語宇宙論には含まれている.つまり,そこには言語の主要機能を「意思伝達」ではなく,「宇宙創造」と捉えるような言語観が示されていると理解できるのである.

「言語宇宙論」は,現代言語学では取り扱われることのない言語観ではあるが,1つの言語観ではある.

・ 星野 英紀・池上 良正・氣田 雅子・島薗 進・鶴岡 賀雄(編) 『宗教学事典』 丸善株式会社,2010年.

2023-08-22 Tue

■ #5230. 「宗教の言葉」 --- 『宗教学事典』より [religion][semantics][semantic_change][polysemy][register][kotodama]

「#5221. 「祈り」とは何だろうか? (2)」 ([2023-08-13-1]) で触れた『宗教学事典』をパラパラと読み続けている.「言葉・言霊」の項目下に「宗教の言葉」 (346--47) という小見出しの興味深い解説があった.宗教言語と日常言語は何がどう異なっているのだろうか.

●宗教の言葉 宗教の場において生起する言葉,あるいはそこで使用される言葉の総体は,一般に「宗教言語」と呼ばれている.例えば,「神の愛」や「仏国土」が語られる場合,その神の「愛」や仏「国土」は,日常会話で言われる意味合いとは次元を異にした,人間の概念的把握を超えた一種の絶対性を示すものである.語彙としては日常言語と同じでも,それが宗教の場に現れると,完全に異次元の意味を帯びうるのである.このように,日常言語で流通している意味を遮断し,それとは断絶した超越的次元を指し示す働きが,宗教言語にはある.

宗教の場とは,具体的には,宗教経験が成立する場であり,また儀礼や祭祀が行われる場である.そこでは,「絶対が相対となる」逆説,反対方向から見れば,「相対が絶対となる」逆説が生じている.超越的霊異が言葉として現れるとき,神の言や仏説(仏が説いた教え,仏典)として受容されるが,その言葉は日常生活で使用される言葉と同じ言語体系に属するものである.さもなければ,神の言や仏説は,それとして理解されえない.つまり,宗教の場では,絶対が相対となる現象として,まさに日常の言葉(相対)が絶対性を獲得する事態が生じるのである.超越的次元が開示されたり,超越的次元を指示したりするほどに,言葉が変成を遂げるのである.こうした宗教の場では,何らかの仕方で,日常生活の流れが断ち切られて超越的次元との統一に向かう一方,その統一から再び日常生活に復帰するという不断の往復運動が見られる.この「日常からの超脱→(絶対との統一)→日常への復帰」という逆方向の二重の運動が,宗教経験や宗教儀礼の全振幅をなしている.

ところで,変成した言葉,つまり宗教言語にはいくつかの次元や位相が折り込まれていると想定される.超越的霊異が現れた絶対的真理は,直観・象徴・概念の形で把握されるのが普通である.それゆえ,宗教言語が孕む次元や位相の相違は,それを受け取る側での認識様態の相違として理解することができる.神自身が物語る神話・神託・啓示,仏による法身説法・仏説そのもの(いわば第一次の宗教言語)は,まず直観的に感得され,覚醒や救済の自覚・再認が深められてゆく.次いで,信仰告白や信解の言葉(第二次の宗教言語)が信仰集団に共有され,象徴的な意匠を纏って儀礼の内に取り込まれる.そして,概念的な精錬を経ながら聖典・経典が編纂され,ついには神学・教学など学問的地平で体系的な論議の言葉(第三次の宗教言語)が産出される.

宗教の場において宗教言語が発生するとともに,逆に宗教言語によって宗教の場それ自体が磁化され,根源的な生命力で再構成されるという側面がある.とりわけ,祈りの言葉や瞑想の言葉は,宗教言語の本質的特性が最も凝縮されたものといえる.祈りや冥想において生じるのは,自我意識の我執が否定的に解体されて無となり,そこに絶対の次元が開かれて透入するという事態である.イエスの祈り,ディクル(スーフィーの称名),念仏,題目,マントラ(真言),祝詞,神呪などの祈りや冥想の定型句は,よく知られている.その種の定型句を称えることは,そのつど「日常からの超脱(→絶対との統一)→日常への復帰」が端的に実現されることに他ならない.古来,聖句・聖音の口誦が伝統的に重視され,宗教的行法の一環として組み込まれてきた所以である.

いろいろと疑問が湧いてきた.宗教の場においては「愛」や「国土」の意味が変わるということだが,これは果たして意味論 (semantics) の考察対象になるのだろうか.日常言語と宗教言語の間に,多義性 (polysemy) や意味変化 (semantic_change) が生じていると考えてよいのだろうか.辞書などでは,宗教的な語義に関して【宗教(学)】や【キリスト教】などのレーベルが付加されることもあるだろうから,レジスターの問題としてとらえられているのだろうか.

一方,上の引用では「受け取る側での認識様態の相違」という表現が用いられている.受け取る側で意味を創造したり選択したりしているのだとすれば,意味変化・変異の主体をめぐる問題とも関わってくるだろう.これについては「#1936. 聞き手主体で生じる言語変化」 ([2014-08-15-1]) などを参照.

祈りの言語については「#3908. 「祈り」とは何だろうか?」 ([2020-01-08-1]) と「#5221. 「祈り」とは何だろうか? (2)」 ([2023-08-13-1]) も参照.「#753. なぜ宗教の言語は古めかしいか」 ([2011-05-20-1]) も関係してくるだろう.

・ 星野 英紀・池上 良正・氣田 雅子・島薗 進・鶴岡 賀雄(編) 『宗教学事典』 丸善株式会社,2010年.

2023-08-01 Tue

■ #5209. 他動性 (transitivity) とは何か? (3) [transitivity][termonology][verb][grammar][syntax][construction][semantic_role][semantics]

他動性 (transitivity) について,2回にわたって論じてきた.

・ 「#5202. 他動性 (transitivity) とは何か?」 ([2023-07-25-1])

・ 「#5204. 他動性 (transitivity) とは何か? (2)」 [2023-07-27-1]

今回は Bussmann (494--95) の用語辞典より transitivity の項を引用する.

Valence property of verbs which require a direct object, e.g. read, see, hear. Used more broadly, verbs which govern other objects (e.g. dative, genitive) can also be termed 'transitive'; while only verbs which have no object at all (e.g. sleep, rain) would be intransitive. Hopper and Thompson (1980) introduce other factors of transitivity in the framework of universal grammar, which result in a graduated concept of transitivity. In addition to the selection of a direct object, other semantic roles as well as the properties of adverbials, mood, affirmation vs negation, and aspect play a role. A maximally transitive sentence contains a non-negated resultive verb in the indicative which requires at least a subject and direct object; the verb complements function as agent and affected object, are definite and animate . . . . Using data from various languages, Hopper and Thompson demonstrate that each of the factors listed above as affecting transitivity is important for making transivtivity through case, adpositions, or verbal inflection. Thus in many languages (e.g. Lithuanian, Polish, Middle High German) affirmation vs negation correlates with the selection of case for objects in such a way that in affirmative sentences the object is usually in the accusative, while in negated sentences the object of the same verb occurs in the genitive or in another oblique case.

他動性とは,(1) グラデーションであること,(2) 言語によってその具現化の方法は様々であること,が分かってきた.理論的には,対格目的語を要求する,結果を表わす直説法の肯定動詞が,最大限に "transitive" であるということだ.

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

2023-07-27 Thu

■ #5204. 他動性 (transitivity) とは何か? (2) [transitivity][termonology][verb][grammar][syntax][construction][semantic_role][semantics][philosophy_of_language]

「#5202. 他動性 (transitivity) とは何か?」 ([2023-07-25-1]) ひ引き続き,他動性 (transitivity) について.

Halliday の機能文法によると,他動性を考える際には3つのパラメータが重要となる.過程 (process),参与者 (participant),状況 (circumstance) の3つだ.このうち,とりわけ過程 (process) が支配的なパラメータとなる.

「過程」と称されるものには大きく3つの種類がある.さらに小さくいえば3つの種類が付け足される.それぞれを挙げると,物質的 (material),精神的 (mental),関係的 (relational),そして 行為的 (behavioural), 言語的 (verbal), 存在的 (existential) の6種となる.

Transitivity A term used mainly in systemic functional linguistics to refer to the system of grammatical choices available in language for representing actions, events, experiences and relationships in the world . . . .

There are three components in a transitivity process: the process type (the process or state represented by the verb phrase in a clause), the participant(s) (people, things or concepts involved in a process or experiencing a state) and the circumstance (elements augmenting the clause, providing information about extent, location, manner, cause, contingency and so on). So in the clause 'Mary and Jim ate fish and chips on Friday', the process is represented by 'ate', the participants are 'Mary and Jim' and the circumstances are 'on Friday'.

Halliday and Mtthiesen (2004) identify three main process types, material, mental and relational, and three minor types, behavioural, verbal and existential. Associated with each process are certain kinds of participants. 1) Material processes refer to actions and events. The verb in a material process clause is usually a 'doing' word . . .: Elinor grabbed a fire extinguisher; She kicked Marina. Participants in material processes include actor ('Elinor', 'she') and goal ('a fire extinguisher', 'Marina'). 2) Metal processes refer to states of mind or psychological experiences. The verb in a mental process clause is usually a mental verb: I can't remember his name; Our party believes in choice. Participants in mental processes include senser(s) ('I'; 'our party') and phenomenon ('his name'; 'choice'). 3) Relational processes commonly ascribe an attribute to an entity, or identify it: Something smells awful in here; My name is Scruff. The verb in a relational processes include token ('something', 'my name')) and value ('Scruff', 'awful'). 4) Behavioural processes are concerned with the behaviour of a participant who is a conscious entity. They lie somewhere between material and mental processes. The verb in a behavioural process clause is usually intransitive, and semantically it refers to a process of consciousness or a physiological state: Many survivors are sleeping in the open; The baby cried. The participant in a behavioral process is called a behaver. 5) Verbal processes are processes of verbal action: 'Really?', said Septimus Coffin; He told them a story about a gooseberry in a lift. Participants in verbal processes include sayer ('Septimus Coffin', 'he'), verbiage ('really', 'a story') an recipient ('them'). 6) Existential processes report the existence of someone or something. Only one participant is involved in an existential process: the existent. There are two main grammatical forms for this type of process: existential there as subject + copular verb (There are thousands of examples.); and existent as subject + copular verb (Maureen was at home.)

これらは,言語活動においてとりわけ根源的な意味関係の6種を選び取ったものといってよいだろう.言語哲学的にいえば,これらのパラメータがどこまで根源的な言語カテゴリーを構成するのかは分からない.考え方一つである.

しかし,機能文法的には当面これらを前提として「過程」が定義され,さらにいえば「他動性」の程度も決まってくる,ということになっている.他動性とはすぐれて相対的な概念・用語ではあるが,このような言語観・文法観の枠組みから出てきた発想であることは知っておきたい.

・ Pearce, Michael. The Routledge Dictionary of English Language Studies. Abingdon: Routledge, 2007.

2023-07-20 Thu

■ #5197. 固有名に意味はあるのか,ないのか? [onomastics][semantics][sign][semiotics][lexicon][connotation]

標題の問いについては,多くの議論がなされてきた.例えば人名や地名を考えてみよう.「大谷」や「広島」には,指示対象 (referent) があるだけであり,そこに意味 (meaning) はない,という議論がある.これは「#2212. 固有名詞はシニフィエなきシニフィアンである」 ([2015-05-18-1]) でも前提とした立場だ.

一方,「大谷」は「大きい」「谷」,「広島」は「広い」「島」という語形成であり,各々の要素も,それを組み合わせた合成物も,それぞれ日本語において確かに意味をもつものと考えることができる.さらにいえば,多くの日本語話者にとって多くの場合,「大谷」にはプロ野球界におけるヒーローのイメージが付随しており,「広島」には平和のメッセージが込められている.このようなイメージ性やメッセージ性は,語彙的意味であるとはいえないまでも,別の観点から何らかの意味であるということができそうだ.何をもって「意味」とするかという難しい議論につながっていくことは不可避である.

この問題と関連して,Nyström は5つほどの意味を区別している.私のコメントを付しながら解説する.

(1) 語彙的意味 (lexical meaning):上記の例でいえば「大谷」は「大きい谷」ほどの通常の語彙的意味をもっている.

(2) 固有名的意味 (proprial meaning):「広島」は,日本の本州西部に位置する県あるいは市を指示する固有名詞である.

(3) 範疇的意味 (categorial meaning):「ポチ」は(典型的に)犬というカテゴリーに属するメンバーに付けられる名前である.

(4) 連想的意味 (associative meaning):「大谷」は(多くの人にとって)プロ野球界の希望の星である.

(5) 感情的意味 (emotive meaning):「広島」は(多くの人にとって)原爆被害の強烈な悲惨さ,平和への願いを喚起する.

とりわけ (4) や (5) のような含蓄的意味 (connotation) は,内容も程度も個人によって,あるいは集団にとって異なり得るものであり,語彙的意味や固有名的意味にみられる一般性は必ずしもみられないかもしれない.

・ Nyström, Staffan. "Names and Meaning." Chapter 3 of The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. Ed. Carole Hough. Oxford: OUP, 2016. 39--51.

2023-07-01 Sat

■ #5178. 名義論的変化の2つのタイプ [lexicology][semantic_change][homonymic_clash][semantics][synonym][semiotics][onomasiology]

昨日の記事「#5177. 語義論 (semasiology) と名義論 (onomasiology)」 ([2023-06-30-1]) で取り上げたように,意味変化 (semantic_change or semasiological change) とともに扱われることが多いが,明確に区別すべき過程として名義論的変化 (onomasiological change) というものがある.

Traugott and Dasher (52--53) は,名義論的変化 ("onomasiological changes") について,Bréal の議論を参照する形で,2つのタイプを挙げている.

(i) Specialization: one element "becomes the pre-eminent exponent of the grammatical conception of which it bears the stamp" . . . , for example, the selection of que as the sole complementizer in French . . . .

(ii) Differentiation: two elements which are (near-)synonymous diverge. Paradigm examples include, in English, (a) the specialization, e.g. of hound when dog was borrowed from Scandinavian, and (b) loss of a form when sound change leads to "homonymic clash," e.g. ME let in the sense "prohibit" from OE lett- was lost after OE lætan "allow" also developed into ME let . . . .

Bréal によれば,名義論的変化は,意味変化の話題でないばかりか,単純に名前の変化というわけでもなく,"the proper subject of the 'science of significations'" (95) ということらしい.

正直にいうと,Bréal の説明は込み入っており理解しにくい.

・ Traugott, Elizabeth C. and Richard B. Dasher. Regularity in Semantic Change. Cambridge: CUP, 2005.

・ Bréal, Michel. Semantics: Studies in the Science of Meaning. Trans. Mrs. Henry Cust. New York: Dover, 1964. 1900.

2023-06-30 Fri

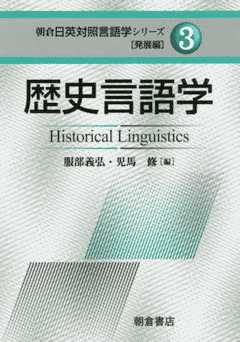

■ #5177. 語義論 (semasiology) と名義論 (onomasiology) [lexicology][semantic_change][semantics][semiotics][onomasiology][terminology]

語の意味変化 (semantic_change) を論じる際に,語義論 (semasiology) と名義論 (onomasiology) を分けて考える必要がある.堀田 (155) より引用する.

語の意味変化を考えるに当たっては,語義論 (semasiology) と名義論 (onomasiology) を区別しておきたい.語を意味と発音の結びついた記号と考えるとき,発音(名前)を固定しておき,その発音に結びつけられる意味が変化していく様式を,語義論的変化と呼ぶ.一方,意味の方を固定しておき,その意味に結びつけられる名前が変化していく様式を名義論的変化と呼ぶ.語の意味変化を,記号の内部における結びつき方の変化として広義に捉えるならば,語義論的な変化のみならず名義論的な変化をも考慮に入れてよいだろう.

要するに,語義論は通常の意味変化,名義論は名前の変化と理解しておけばよい.「#3283. 『歴史言語学』朝倉日英対照言語学シリーズ[発展編]が出版されました」 ([2018-04-23-1]) を参照.

・ 堀田 隆一 「第8章 意味変化・語用論の変化」『歴史言語学』朝倉日英対照言語学シリーズ[発展編]3 服部 義弘・児馬 修(編),朝倉書店,2018年.151--69頁.

2023-06-27 Tue

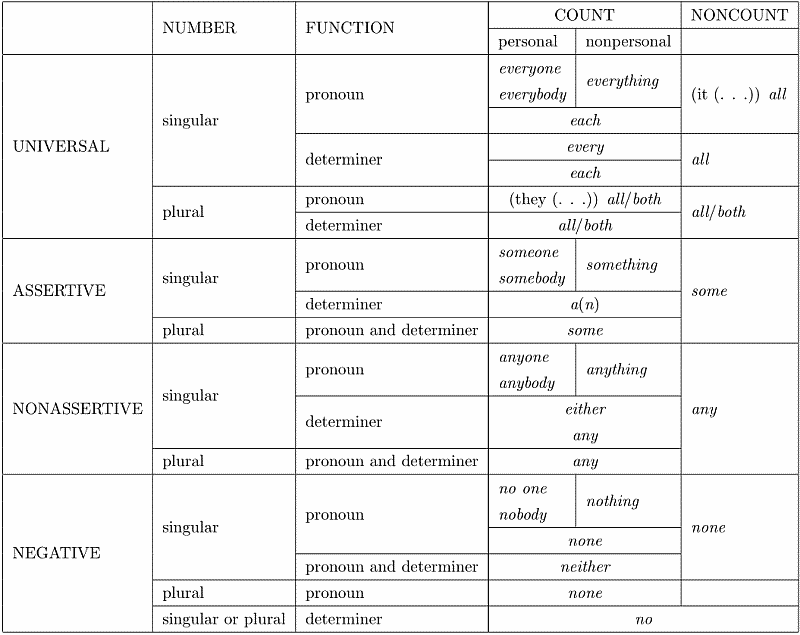

■ #5174. 不定代名詞・決定詞 [pronoun][personal_pronoun][generic][indefinite_pronoun][determiner][assertion][semantics][logic]

現代英語には不定代名詞 (indefinite_pronoun) や不定決定詞 (indefinite determiner) という語類の体系がある.不定 (indefinite) の反対は定 (definite) である.例えば人称代名詞,再帰代名詞,所有代名詞,指示代名詞,そしてときに疑問代名詞にも定的な要素が確認されるが,不定代名詞にはそれがみられない.ただし,不定代名詞・決定詞は,むしろ論理的観点から,量的である (quantitative) ととらえてもよいかもしれない.全称的 (universal) か部分的 (partitive) かという観点である.

Quirk et al. (§6.45) に主要な不定代名詞・決定詞の一覧表がある.こちらを掲載しよう.体系的ではあるが,なかなか複雑な語類であることがわかるだろう.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2023-06-04 Sun

■ #5151. 日本語反対語辞典の「まえがき」より [lexicology][semantics][antonymy][synonym][structuralism][thesaurus][dictionary]

「反対語」「対義語」「対照語」「対応語」などと称される antonym は,語彙意味論においても関心を集めてきた.私も反対語辞典の類いは好きでよく引くのだが,日本語で常用しているものとして『反対語対照語辞典 新装版』がある.

反対語といっても「反対」のあり方は様々で,語彙意味論でもまさにその点が問題となる.上記の辞典の「まえがき」 (i--ii) を読めば,その難しさとおもしろさが理解できるだろう.

単語は一つ一つがばらばらに存在しているのではなく,まとまりをもち,いわばネットワークをなしている.たとえば「父」という単語は,「お父さん」「おやじ」「パパ」などと言い換えることができる.これら四語は,同じものを指している.四語の間には敬意の有無やニュアンスの違いなどがあり,完全に同義であるとはいえないが,同義に近い関係ーー類義の関係ーーにあるということができる.一方,「父」の対として「母」という語がある.そして,「母」にも「お母さん」「おふくろ」「ママ」といったような類義の語が存在する.また,「父」と「母」の両者を包含する語として「親」があり,「親」の対として「子」という語がある.このように,単語は相互に関連して複雑な組織網を形成している.

反対語の定義はきわめて難しい.同義語・類義語には同じものを指すといった基準があるが,反対語の条件は単純ではない.反対語という場合,まず両者の間に共通する意味がなければならない.「母」が「父」の反対語になるのは,両者が<親>という共通の意味をもっているからである.しかし,共通する意味をもっているだけでは,もちろん反対語にはならない.「母」が「父」の反対語になるのは,男性ではなく女性であるということによる.つまり,男性か女性かという基準から見て反対の意味になるのである.反対語の条件は,

(1) 共通する意味をもっていること

(2) その上で,ある基準から見て,反対の意味をもっていること

の二点であるということになるだろう.

もう一つの例をあげよう.「大勝」の反対語には,「大敗」と「辛勝」とがあげられるが,前者は,(1) 大差で勝負がつくという共通点をもち,(2) 勝ち負けという基準から見て反対の意味をもっており,後者,つまり「辛勝」は,(1) 勝つという共通の意味をもち,(2) 勝ち方が大差か小差かという基準から見て反対の意味をもっている.ある語の反対語は,一つとは限らない.基準が変わると,いくつも存在することになる.

以上のように説明すると,反対語の判定は比較的容易なように見えるが,一語一語について具体的に考えていく段になると,反対の意味とは何かということが問題になってきて,判断に苦しむことが多い.

上記で例に挙げられている「大勝」に関する辞典内の図を参照しよう.構造主義的な,きれいなマトリックスとなる.

| <大差> | <小差> | ||

| <勝利> | 圧勝(大勝・快勝) | ←───→ | 辛勝 |

| ↑ | ↑ | ||

| │ | │ | ||

| ↓ | ↓ | ||

| <敗北> | 惨敗(大敗・完敗) | ←───→ | 惜敗 |

しかし,多くの場合,そこまできれいなマトリックスにはならない.反対関係はもっと複雑になることも多い.例えば「水」を中心とした語彙の関係図を示そう.

┌─┐ │油│ └─┘ ┌─┐ ↑ ┌─┐ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ ↓ │ │ │水│←──────→┌─┐ │ │ │ │ ┌─┐ │ │ │ │ │蒸│ │湯│←─→│水│←─→│氷│ │ │ └─┘ │ │ │ │ │気│ └─┘ │ │ │ │ ↑ │ │ │ │←────────┼───→│ │ └─┘ ↓ └─┘ ┌─┐ │火│ └─┘

反対語の意味論については,hellog および heldio より以下を参照.

・ hellog 「#1800. 様々な反対語」 ([2014-04-01-1])

・ hellog 「#1804. gradable antonym の意味論」 ([2014-04-05-1])

・ hellog 「#1968. 語の意味の成分分析」 ([2014-09-16-1])

・ hellog 「#4102. 反意と極性」 ([2020-07-20-1])

・ heldio 「#353. 反対語っていろいろあっておもしろい!」

・ heldio 「#354. long と short は対等な反対語ではない?」

・ 北原 保雄・東郷 吉男(編) 『反対語対照語辞典 新装版』 東京堂出版,2015年.

2023-05-19 Fri

■ #5135. 不定冠詞の発達の一般経路 [grammaticalisation][article][pragmatics][semantics][historical_pragmatics][unidirectionality][numeral]

Heine and Kuteva (92) によると,諸言語において不定冠詞 (indefinite article) が発達してきた経路をたどってみると,しばしばそこには意味論的・語用論的な観点から一連の段階が確認されるという.

1 An item serves as a nominal modifier denoting the numerical value 'one' (numeral).

2 The item introduces a new participant presumed to be unknown to the hearer and this participant is then taken up as definite in subsequent discourse (presentative marker).

3 The item presents a participant known to the speaker but presumed to be unknown to the hearer, irrespective of whether or not the participant is expected to come up as a major discourse participant (specific indefinite marker).

4 The item presents a participant whose referential identity neither the hearer nor the speaker knows (nonspecific indefinite marker).

5 The item can be expected to occur in all contexts and on all types of nouns except for a few contexts involving, for instance, definiteness marking, proper nouns, predicative clauses, etc. (generalized indefinite article).

英語の不定冠詞の発達においても,この一連の段階が見られたのかどうかは,詳細に調査してみなければ分からない.しかし,少なくとも発達の開始に相当する第1段階は的確である.つまり,数詞 one (古英語 ān) から始まったことは疑い得ない.2--5の各段階が実証されれば,文法化 (grammaticalisation) の一方向性 (unidirectionality) を支持する事例として取り上げられることにもなろう.注目すべき時代は,おそらく中英語期から近代英語期にかけてとなるに違いない.

関連して「#2144. 冠詞の発達と機能範疇の創発」 ([2015-03-11-1]) も参照.

・ Heine, Bernd and Tania Kuteva. "Contact and Grammaticalization." Chapter 4 of The Handbook of Language Contact. Ed. Raymond Hickey. 2010. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. 86--107.

2023-05-16 Tue

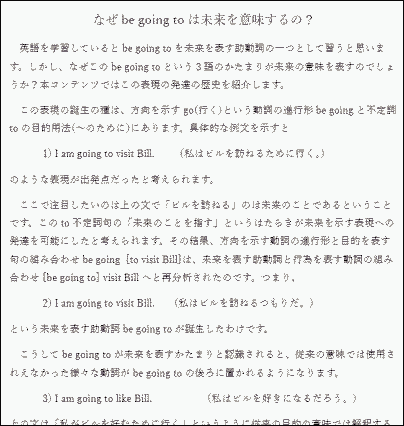

■ #5132. なぜ be going to は未来を意味するの? --- 「文法化」という観点から素朴な疑問に迫る [sobokunagimon][tense][future][grammaticalisation][reanalysis][metanalysis][syntax][semantics][auxiliary_verb][khelf][voicy][heldio][hel_contents_50_2023][notice]

標題は多くの英語学習者が抱いたことのある疑問ではないでしょうか?

目下 khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)では「英語史コンテンツ50」企画が開催されています.4月13日より始めて,休日を除く毎日,khelf メンバーによる英語史コンテンツが1つずつ公開されてきています.コンテンツ公開情報は日々 khelf の公式ツイッターアカウント @khelf_keio からもお知らせしていますので,ぜひフォローいただき,リマインダーとしてご利用ください.

さて,標題の疑問について4月22日に公開されたコンテンツ「#9. なぜ be going to は未来を意味するの?」を紹介します.

さらに,先日このコンテンツの heldio 版を作りました.コンテンツ作成者との対談という形で,この素朴な疑問に迫っています.「#711. なぜ be going to は未来を意味するの?」として配信しています.ぜひお聴きください.

コンテンツでも放送でも触れているように,キーワードは文法化 (grammaticalisation) です.英語史研究でも非常に重要な概念・用語ですので,ぜひ注目してください.本ブログでも多くの記事で取り上げてきたので,いくつか挙げてみます.

・ 「#417. 文法化とは?」 ([2010-06-18-1])

・ 「#1972. Meillet の文法化」([2014-09-20-1])

・ 「#1974. 文法化研究の発展と拡大 (1)」 ([2014-09-22-1])

・ 「#1975. 文法化研究の発展と拡大 (2)」 ([2014-09-23-1])

・ 「#3281. Hopper and Traugott による文法化の定義と本質」 ([2018-04-21-1])

・ 「#5124 Oxford Bibliographies による文法化研究の概要」 ([2023-05-08-1])

とりわけ be going to に関する文法化の議論と関連して,以下を参照.

・ 「#2317. 英語における未来時制の発達」 ([2015-08-31-1])

・ 「#3272. 文法化の2つのメカニズム」 ([2018-04-12-1])

・ 「#4844. 未来表現の発生パターン」 ([2022-08-01-1])

・ 「#3273. Lehman による文法化の尺度,6点」 ([2018-04-13-1])

文法化に関する入門書としては「#2144. 冠詞の発達と機能範疇の創発」 ([2015-03-11-1]) で紹介した保坂道雄著『文法化する英語』(開拓社,2014年)がお薦めです.

・ 保坂 道雄 『文法化する英語』 開拓社,2014年.

2023-04-06 Thu

■ #5092. 商標言語学と英語史・歴史言語学の接点 [trademark][goshosan][youtube][voicy][heldio][link][semantics][semantic_change][metaphor][metonymy][synecdoche][rhetoric][onomastics][personal_name][toponymy][eponym][sound_symbolism][phonaesthesia][capitalisation][linguistic_right][language_planning][semiotics][punctuation]

昨日までに,Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」や YouTube 「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」を通じて,複数回にわたり五所万実さん(目白大学)と商標言語学 (trademark linguistics) について対談してきました.

[ Voicy ]

・ 「#667. 五所万実さんとの対談 --- 商標言語学とは何か?」(3月29日公開)

・ 「#671. 五所万実さんとの対談 --- 商標の記号論的考察」(4月2日公開)

・ 「#674. 五所万実さんとの対談 --- 商標の比喩的用法」(4月5日公開)

[ YouTube ]

・ 「#112. 商標の言語学 --- 五所万実さん登場」(3月22日公開)

・ 「#114. マスクしていること・していないこと・してきたことは何を意味するか --- マスクの社会的意味 --- 五所万実さんの授業」(3月29日公開)

・ 「#116. 一筋縄ではいかない商標の問題を五所万実さんが言語学の切り口でアプローチ」(4月5日公開)

・ 次回 #118 (4月12日公開予定)に続く・・・(後記 2023/04/12(Wed):「#118. 五所万実さんが深掘りする法言語学・商標言語学 --- コーパス法言語学へ」)

商標の言語学というのは私にとっても馴染みが薄かったのですが,実は日常的な話題を扱っていることもあり,関連分野も多く,隣接領域が広そうだということがよく分かりました.私自身の関心は英語史・歴史言語学ですが,その観点から考えても接点は多々あります.思いついたものを箇条書きで挙げてみます.

・ 語の意味変化とそのメカニズム.特に , metonymy, synecdoche など.すると rhetoric とも相性が良い?

・ 固有名詞学 (onomastics) 全般.人名 (personal_name),地名,eponym など.これらがいかにして一般名称化するのかという問題.

・ 言語の意味作用・進化論・獲得に関する仮説としての "Onymic Reference Default Principle" (ORDP) .これについては「#1184. 固有名詞化 (1)」 ([2012-07-24-1]) を参照.

・ 記号論 (semiotics) 一般の諸問題.

・ 音象徴 (sound_symbolism) と音感覚性 (phonaesthesia)

・ 書き言葉における大文字化/小文字化,ローマン体/イタリック体の問題 (cf. capitalisation)

・ 言語は誰がコントロールするのかという言語と支配と権利の社会言語学的諸問題.言語権 (linguistic_right) や言語計画 (language_planning) のテーマ.

細かく挙げていくとキリがなさそうですが,これを機に商標の言語学の存在を念頭に置いていきたいと思います.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow