2026-02-22 Sun

■ #6145. 2月28日(土),朝カル講座の冬期クール第2回「that --- 指示詞から多機能語への大出世」が開講されます [asacul][notice][hel_education][helkatsu][deixis][demonstrative][article][relative_pronoun][conjunction]

今年度は月1回,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室で英語史講座を開いています.シリーズタイトルは「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」です.日常的でありながらも深い歴史やいわくありげな背景をもっている英単語を毎回1つ選び,『英語語源辞典』(研究社)や『英語語源ハンドブック』(研究社)等の記述を参照しながら,その単語の魅力に迫り,同時に英語史のダイナミズムをも感じていただきます

2月28日(土)の講座は冬期クールの第2回となります.今回取り上げるのは,あまりに多義・多機能で正体が何なのかが分からなくなりそうな that という単語に注目します.1音節の小さな語ですが,ある意味で英文法を背負っているかのような八面六臂の活躍.その起源と発展をたどると,この単語の理解が増し,愛着も湧いてくること間違いなしです.

以下,that をめぐってどんな論点があるのか,ブレスト風に書き出してみます.

・ Is that that that that that that refers to? / That that is is that that is not is not is that it it is.

・ that と定冠詞 the の関係は?

・ 指示詞の th- と疑問詞の wh- の関係は?

・ 直示性の単語たち:this, these, that, those

・ this 単独では人を指せるけれど,that 単独だと失礼になるのはなぜ?

・ those who などと those 人々を指し得るのはなぜ?

・ I think that . . . . などの that 節はいかにして生まれたか?

・ ゆるい副詞節を導く that

・ 関係代名詞の that は,他の関係代名詞と何が異なるのか?

・ that の「省略」,あるいは虚辞の that について

ほかにも論点は挙がってくるものと思われます.that のすべてを90分で語り尽くすことはできませんが,歴史をたどることで,その魅力をあぶり出したいと思います.

講座への参加方法は,今期もオンライン参加のみとなります.リアルタイムでの受講のほか,2週間の見逃し配信サービスもあります.皆さんのご都合のよい方法でご参加いただければ幸いです.開講時間は 15:30--17:00 となっています.講座と申込みの詳細は朝カルの公式ページよりご確認ください.

なお,冬期クールの第3回は以下の通りの予定です.春に向けて,英語史の学びを盛り上げていきましょう!

・ 第12回:3月28日(土) 15:30?17:00 「be --- 英語の「存在」を支える超不規則動詞」

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

2026-01-06 Tue

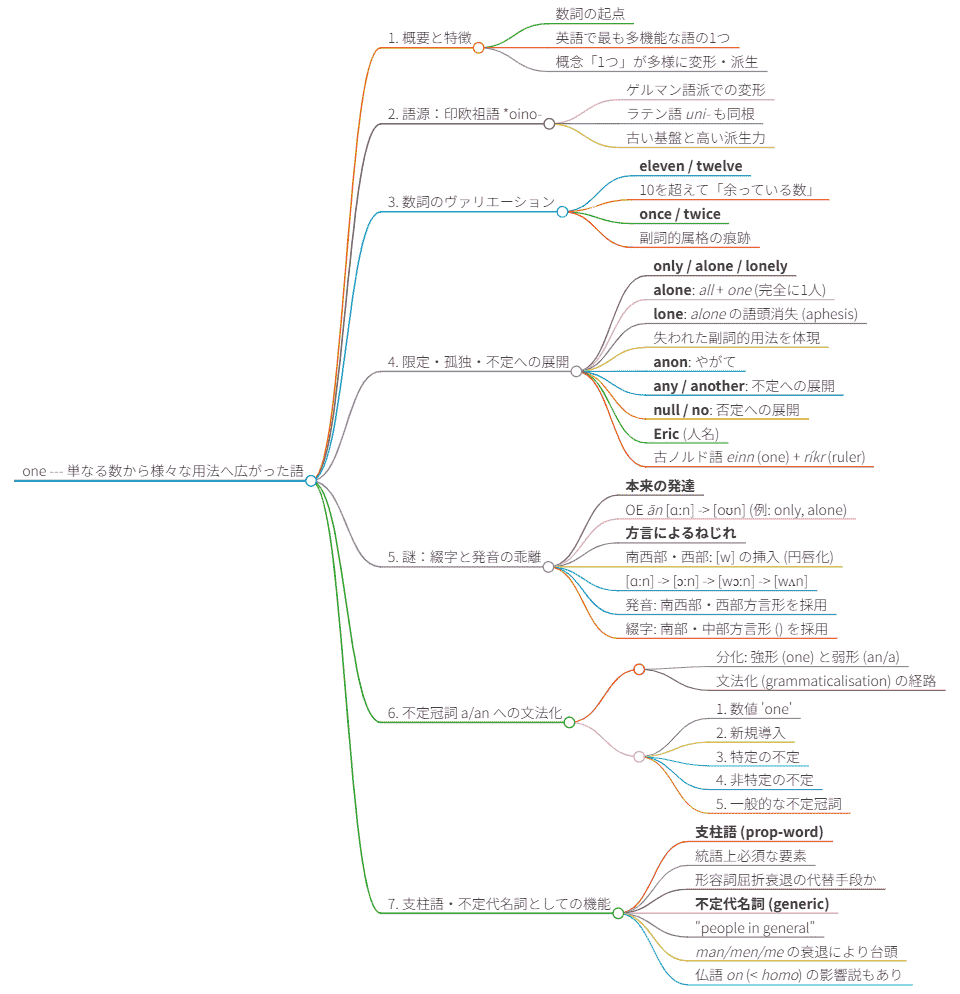

■ #6098. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第9回「one --- 単なる数から様々な用法へ広がった語」をマインドマップ化してみました [asacul][mindmap][notice][etymology][one][numeral][article][link][hel_education][one]

12月20日(土)に,今年度の朝日カルチャーセンターのシリーズ講座「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」の第9回が,秋期クールの第3回として開講されました.テーマは「one --- 単なる数から様々な用法へ広がった語」でした.

あまりに当たり前の単語ですが,英語史的には実に奥の深い語彙項目で,じっくり鑑賞するに値する対象です.いかにして基本的な数詞の役割から,文法化を経て不定冠詞となり,不定代名詞となり,支柱語となったのでしょうか.基本語だけに,そこから語形成を経て生じた関連語も多く,その1つひとつもやはり興味深い歴史をたどっています.実際,講義の90分では語りきれないほどでした.それほど one の世界は深くて広くて深いのです.

この朝カル講座第9回の内容を markmap によりマインドマップ化して整理しました.復習用にご参照いただければ.

なお,この朝カル講座のシリーズの第1回から第8回についてもマインドマップを作成してるので,そちらもご参照ください.

・ 「#5857. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第1回「she --- 語源論争の絶えない代名詞」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-05-10-1])

・ 「#5887. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第2回「through --- あまりに多様な綴字をもつ語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-06-09-1])

・ 「#5915. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第3回「autumn --- 類義語に揉み続けられてきた季節語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-07-07-1])

・ 「#5949. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第4回「but --- きわめつきの多義の接続詞」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-08-10-1])

・ 「#5977. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第5回「guy --- 人名からカラフルな意味変化を遂げた語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-09-07-1])

・ 「#6013. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第6回「English --- 慣れ親しんだ単語をどこまでも深掘りする」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-10-01-1])

・ 「#6041. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第7回「I --- 1人称単数代名詞をめぐる物語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-11-10-1])

・ 「#6076. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第8回「take --- ヴァイキングがもたらした超基本語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-12-15-1])

シリーズは次回より冬期クールに入ります.次回の第10回は新年1月31日(土)に「very --- 「本物」から大混戦の強意語へ」と題して開講されます.開講形式は引き続きオンラインのみで,開講時間は 15:30--17:00 です.ご関心のある方は,ぜひ朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室の公式HPより詳細をご確認の上,お申し込みいただければ幸いです.

2025-12-19 Fri

■ #6080. 中英語における any の不定冠詞的な用法 [article][adjective][comparison][me][oe]

古英語の数詞 ān から不定代名詞や不定冠詞 (indefinite article) が発達したように,その派生語である古英語 ǣniȝ からも不定代名詞や不定形容詞が発達した.a(n) や any は,このように起源と発達において類似点が多いため,意味や用法について互いに乗り入れしていると見受けられる側面がある.

例えば,中英語では特に同等比較の構文において,不定冠詞 a(n) が予想されるところに any が現われるケースがある.不定冠詞としての any の用法だ.Mustanoja (263) より見てみよう.

In second members of comparisons, particularly in comparisons expressing equality, any is not uncommon: --- isliket and imaket as eni gles smeþest (Kath. 1661); --- tristiloker þan ony stel (RMannyng Chron. 4864); --- his berd as any sowe or fox was reed (Ch. CT A Prol. 552); --- as blak he lay as any cole or crowe (Ch. CT A Kn. 2692); --- fair was this younge wyf, and therwithal As any wezele hir body gent and smal (Ch. CT A Mil. 3234); --- his steede . . . Stant . . . as stille as any stoon (Ch. CT F Sq. 171); --- þ maden as mery as any men moȝten (Gaw. & GK 1953; any with a plural noun); --- also red and so ripe . . . As any dom myȝt device of dayntyeȝ oute (Purity 1046). The usage goes back to OE: --- scearpre þonne ænig sweord (Paris Psalter xliv 4).

類似表現は古英語からもあるとのことだ.気になるのは,この場合の any は純粋に a(n) の代用なのだろうか.というのは,現代英語の He is as wise as any man. 「彼はだれにも劣らず賢い」の any の用法を想起させるからだ.単なる不定冠詞を使う場合よりも,any を用いる方がより強調の意味合いが出るということはないのだろうか.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2025-12-17 Wed

■ #6078. an one man --- an 単語が数詞ではなく不定冠詞と分かる例 [article][numeral][grammaticalisation][syntax][me]

歴史的に文法化 (grammaticalisation) を扱う研究をみていると,ある言語項が文法化したといえるのはいつか,どんな例が現われれば確実に文法化したと言い切れるか,という問題に出くわす機会がある.文法化は形式上の問題であると同時に意味の問題でもあるが,意味は研究者が自説に都合よく「読み込む」ことができてしまう.したがって,「この例文では文法化がすでに生じている」と主張するためには,なるべく主観を排して,客観的に確認でき,かつ説得力のある言語学的根拠を示す必要がある.特に形式的な観点から示せるとベストである.

例えば,数詞 one はいつから不定冠詞 (indefinite article) へ文法化したのか,という問題を考えてみる.音韻形態的には古英語 ān が弱まって an や a となったときだと考えたくなるが,中英語期には現代に連なる one を含め,多種多様な強形・弱形が現われており,それぞれが数詞とも不定冠詞とも解釈できる例があり,決着がつかない.1200年前後に書かれた討論詩 The Owl and the Nightingale の ll. 3--4 の "Iherde ich holde grete tale / An hule and one niȝtingale." などを参照されたい.

しかし,統語的な観点から迫る方法がありそうだ.それは標題の an one man のように,2つの "one" が並んで現われるケースだ.この場合,1つめの an が不定冠詞で,2つめの one が数詞である,と結論づけるのは自然であり異論はないだろう.前者は「初出・存在」を標示する文法的な機能を担っているのに対し,後者は「1人・個人」を意味する数詞として機能している語として解釈できる.これは架空の句ではなく,Mustanoja が後期中英語の Gower より引いた実在の表現である.以下に引用する (291) .

For thei be manye, and he [i.e., the king] is on; And rathere schal an one man With fals conseil, for oght he can, From his wisdom be maad to falle (Gower CA vii 4161)

現代英語では「不定冠詞 a + 数詞 one + 名詞」という句は許されないが,中英語にはこれがみられた(もっとも,非常にまれだったことは Mustanoja (291) も述べているが).ちなみに「定冠詞 the + 数詞 one + 名詞」は現代英語でも on the one hand, the one thing, the one exception などと普通にみられる.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2025-12-16 Tue

■ #6077. 「ただ1人・1つ」を意味する副詞的な one [one][adjective][adverb][oe][me][article][numeral]

one について,現代英語では失われてしまった副詞的な用法がある.「ただ1人・1つ;~だけ」を意味する only や alone に近い用法だ.古英語や中英語では普通に見られ,同格的に名詞と結びつく場合には one は統語的に一致して屈折変化を示したので,起源としては形容詞といってよい.しかし,その名詞から遊離した位置に置かれることもあり,その点で副詞的ともいえるのだ.

Mustanoja は "exclusive use" と呼びつつ,この one の用法について詳述している.以下,一部を引用しよう (293--94) .

EXCLUSIVE USE. --- The OE exclusive an, calling attention to an individual as distinct from all others, in the sense 'alone, only, unique,' occurs mostly after the governing noun or pronoun (se ana, þa anan, God ana), but anteposition is not uncommon either (an sunu, seo an sawul, to þæm anum tacne). It has been suggested by L. Bloomfield (see bibliography) that anteposition of the exclusive an is due to the influence of the conventional phraseology of religious Latin writings (unus Deus, solus Deus, etc.). After the governing word the exclusive one is used all through the ME period: --- he is one god over alle godnesse; He is one gleaw over alle glednesse; He is one blisse over alle blissen; He is one monne mildest mayster; He is one folkes fader and frover; He is one rihtwis ('he alone is good . . .' Prov. Alfred 45--55, MS J); --- ȝe . . . ne sculen habben not best bute kat one (Ancr. 190); --- let þe gome one (Gaw. & GK 2118). Reinforced by all, exclusive one develops into alone in earliest ME (cf. German allein and Swedish allena), and this combination, after losing its emphatic character, is in turn occasionally strengthened by all: --- and al alone his wey than hath he nome (Ch. LGW 1777).

引用の最後のくだりでは,現代の alone や all alone の語源に触れられている.要するにこれらは,今はなき副詞的 one の用法を引き継いで残っている表現ということになる.そして,類義の only もまた one の派生語である.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

・ Bloomfield, L. "OHG Eino, OE Ana = Solus." Curme Volume of Linguistic Studies. Language Monograph VII, Linguistic Soc. of America, Philadelphia 1930. 50--59.

2025-12-10 Wed

■ #6071. 「いのほた」で no に関する回が多く視聴されています [inohota][inoueippei][notice][youtube][negative][negation][etymology][article][sobokunagimon]

12月7日(日)の YouTube 「いのほた言語学チャンネル」の話題は「#391. おなじ no でも元々ちがうことば --- no money の no と No, I don't. の no」でした.3週間ほど前の「#387. 英語にはなぜ冠詞があるの?日本語には冠詞がないが,英語の冠詞の役割と似ているのは日本語のあれ」が思いのほか人気回となった(1.45万回視聴)ので,冠詞 (article) の話題の続編というつもりで話しを始めたのですが,地続きのトピックとして no に言及したところ,井上さんがむしろそちらにスポットライトを当て,今回のタイトルとサムネになった次第です.結果として,今回も多くの方々に視聴していただき,良かったです.皆さん,ありがとうございます.

前回の冠詞回でも話したのですが,不定冠詞 a/an は,もともと数詞の one に由来しているので,その本質は存在標示にあるとみなせます.これに対して,否定語の no の本質は,まさに不在標示です.a/an と no は,ある意味で対極にあるものととらえられます.存在するのかしないのか,1か0か,という軸で,不定冠詞と no を眺めてみる視点です.

この観点から見ると,英文法で習う few と a few の意味の違いも理解できます.few は元来 many の対義語であり,「多くない」という否定的な意味合いが強い語です.しかし,これに存在標示の a をつけてみるとどうなるでしょうか.「ないわけではないが,多くはない」という few の否定に傾いた意味に,a が「少ないながらも存在はしている」という肯定的なニュアンスを付け加え,結果として「少しはある」へと意味が調整される,と解釈できるわけです.

さて,この a/an と no の対立構造も奥深いテーマなのですが,今回の動画で視聴者の皆さんが最も驚きをもって受け止めたのは,タイトルにもある通り,2つの no が別語源だった,という事実ではないでしょうか.現代英語では,形容詞として使われる no と,副詞として使われる no が,たまたま同じ綴字・発音になっていますが,実は歴史的なルーツは異なるものなのです.

普段何気なく使っている単語でも,そのルーツをたどると,驚くような歴史が隠されているものです.皆さんもこの不思議な no の歴史を,ぜひ YouTube の動画で確認してみてください.言語学的な知的好奇心を刺激されること請け合いです.また,冠詞や否定というテーマは,情報構造や会話分析にもつながる非常に大きな問題ですので,今後も多角的に掘り下げていきたいと考えています.

2025-11-24 Mon

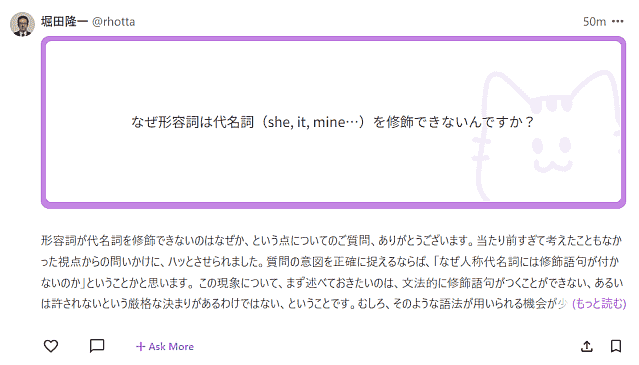

■ #6055. 人称代名詞が修飾されるケース [personal_pronoun][adjective][sobokunagimon][definiteness][determiner][article]

先日,知識共有サービス mond に「なぜ形容詞は代名詞 (she, it, mine…) を修飾できないんですか?」という質問が寄せられました.人称代名詞は「定」 (definiteness) の意味特徴をもち,かつ主たる機能が「指示」であるという観点から回答してみました.今回の回答は,とりわけ多くの方々にお読みいただいているようです.こちらより訪れてみてください.

その回答の最後に Quirk et al. の §6.20 を要参照と述べました.該当する部分を以下に引用しておきます. "Modification and determination of personal pronouns" と題する節の一部です.

In modern English, restrictive modification with personal pronouns is extremely limited. There are, however, a few types of nonrestrictive modifiers and determiners which can precede or follow a personal pronoun. These mostly accompany a 1st or 2nd person pronoun, and tend to have an emotive or rhetorical flavour:

(a) Adjectives:

Silly me!, Good old you!, Poor us! <informal>

(b) Apposition:

we doctors, you people, us foreigners <familiar>

(c) Relative clauses:

we who have pledged allegiance to the flag, . . . <formal>

you, to whom I owe all my happiness, . . . <formal>

(d) Adverbs:

you there, we here

(e) Prepositional phrases:

we of the modern age

us over here <familiar>

you in the raincoat <impolite>

(f) Emphatic reflexive pronouns . . .:

you yourself, we ourselves, he himself

Personal pronouns do not occur with determiners (*the she, *both they), but the universal pronouns all, both, or each may occur after the pronoun head . . .:

We all have our loyalties.

They each took a candle.

You both need help.

さすがに定冠詞を含む決定詞 (determiner) が人称代名詞に付くことはないようですね.人称代名詞がすでに「定」であり,「定」の2重標示になってしまうからでしょうか.人称代名詞の本質的特徴について考えさせられる良問でした.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Grammar of Contemporary English. London: Longman, 1972.

2025-11-23 Sun

■ #6054. turn を自動詞の「変わる」で使うとき,補語にくる名詞は不定冠詞を付けないのはなぜですか? [sobokunagimon][article]

先日,heldio/helwa コアリスナーの umisio さんより質問が寄せられました.

turn を自動詞の「変わる」で使うとき,補語にくる名詞は不定冠詞を付けないのはなぜですか?

確かに「#1347. a lawyer turned teacher」 ([2013-01-03-1]) で取り上げた例を含め,turn の補語には冠詞が付かないのが普通ですね.考えてみれば,なるほど,妙な現象です.a poacher turned gamekeeper 「密猟者転じて猟場番」,turn traitor to ... 「...を裏切る」などの表現が挙がってきます.OED を参照すると,歴史的には不定冠詞の付く例も散見されますが,turn wiseman, turn monster, turn coward などの無冠詞の例が近代英語期に確かに見られます.

他の多くのヨーロッパ諸語とは異なり,英語では補語に立つ可算名詞単数には冠詞を付けるのが普通です.Otani is a baseball player. や Otani is the man. のようにです.しかし,補語(あるいは補語的な同格表現)が唯一無二の役割 (unique role) を帯びている場合には,冠詞が付かないことがあります.Quirk et al. (§5.42) より例を挙げてみます.

Maureen is (the) captain of the team.

John F. Kennedy was (the) President of the United States in 1961.

As (the) chairman of the committee, I declare this meeting closed.

They've appointed Fred (the) treasurer, and no doubt he will soon become (the) secretary.

Anne Martin, (the) star of the TV series and (the) author of a well-known book on international cuisine, has resigned from her post on the Consumer Council.

なるほど,その通りとは思います.しかし,問題の a lawyer turned teacher や turn traitor の補語が「唯一無二の役割」を表わしているかといえば,そのようには解釈できません.実際,Quirk et al. は同箇所の注 [b] にて,次のように但し書きを付しています.

The complement of turn (cf 16.22) is exceptional in having zero article even where there is no implication of uniqueness:

Jenny started out as a music student before she turned linguist. BUT: . . . before she became a linguist.

turn traitor (to) については,コロケーションとして固定しているからという説明も可能かもしれませんが,それ以外の例については,やはり説明が欲しいところです.turn traitor (to) がモデルとなって,それ以外の表現にも波及した,と考えるならば,それは実証する必要があります.あるいは,OED に1582年の初例として turne Christian が挙げられていることから,補語として形容詞兼名詞が立つケースが契機となって,今回のような不規則な語法が生まれた,とも考えられるかもしれませんが,現段階では思いつきの仮説にすぎません.いまだ謎です.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Grammar of Contemporary English. London: Longman, 1972.

2025-11-21 Fri

■ #6052. 「いのほた」で冠詞に関する回がよく視聴されています [inohota][inoueippei][notice][youtube][article][grammaticalisation][sobokunagimon][demonstrative][information_structure]

11月16日(日)に YouTube 「いのほた言語学チャンネル」にて「#387. 英語にはなぜ冠詞があるの?日本語には冠詞がないが,英語の冠詞の役割と似ているのは日本語のあれ」が公開されました.テーマが「冠詞」 (article) という大物だったからでしょうか,おかげさまでよく視聴されています.今朝の時点で視聴回数が1万回を超えており,コメント欄も活発です.

冠詞 (the, a/an) は英語学習者にとって永遠の課題です.冠詞というものがない日本語を母語とする者にとって,とりわけ習得の難しい項目です.私も,なぜ英語にはこのような厄介なものがあるのだろうか,とずっと思っていました.今思うに,これは根源的な問いなのでした.

なぜ冠詞があるのか.この問いは,英語史の観点から紐解いてみると,まず驚くべき事実から始まります.定冠詞 the に相当する要素は,英語を含む多くのヨーロッパ語において,必ずしも最初から存在していたわけではないのです.歴史の途中で,それも比較的後になってから用いられるようになった「新参者」なのです.

古英語の時代にも,the に相当する形式は確かに存在しました.ただし,それは現代的な確立した用法・品詞として使われていたわけではなく,その前駆体というべき存在にとどまっていました.もともと「あれ」「それ」といった意味を表わす指示詞 (demonstrative) だったものが,徐々にその指示力を失い,単に既知のものであることを標示する文法的な要素へと変化していった結果として生まれたものです.このような,もともとの意味が薄まり,文法的な機能をもつようになる変化を「文法化」 (grammaticalisation) と呼んでいます.これは英語の歴史において非常に重要なテーマであり,本ブログでも度々取り上げてきました.

この歴史的な経緯を知ると,最初の素朴な疑問「なぜ冠詞があるのか」は,「なぜ英語は,わざわざ指示詞を冠詞に文法化させる必要があったのか」という,より深い問いへと昇華します.なぜなら,冠詞のない日本語話者は,冠詞のない世界が不便だとは感じていないからです.

この問いに対する1つの鍵となるのが,日本語の助詞「が」と「は」です.動画では,この「が」「は」の使い分けが,英語の冠詞の役割と似ている側面があることを指摘し,情報構造 (information_structure) の観点から議論を展開しました.

冠詞の最も基本的な役割は,話し手と聞き手の間ですでに共有されている情報(=旧情報)か,そうでない新しい情報(新情報)かを区別することにあります.この機能は,日本語の「が」「は」が担う役割と見事にパラレルなのです.日本の昔話を例にとってみましょう.

昔々あるところに,おじいさん(=新情報)とおばあさん(=新情報)がいました.おじいさん(旧情報)は山へ芝刈りに,おばあさん(=旧情報)は川へ洗濯に行きました.

英語にすると,第1文では不定冠詞が,第2文では定冠詞が用いられるはずです.それぞれ日本語の助詞「が」「は」に対応します.

この日本語の「が」「は」の使い分けにみられる新旧情報の区別をしたいというニーズは,言語共同体にとって普遍的なものです.しかし,そのニーズを満たすための手段は,言語ごとに異なっている可能性が常にあります.日本語はすでに発達していた助詞というリソースを選び,英語はたまたま手近にあった指示詞の文法化という道を選んだ,というわけです.

この事実は,英語の冠詞の習得に苦労する私たちに,ある洞察を与えてくれます.英語の冠詞の使い分けを理解するには,その背景にある情報の流れ,すなわち情報構造を理解する必要がある,ということです.英語の冠詞の感覚は,日本語母語話者が無意識のうちに「が」「は」を使い分けている,あの感覚と繋がっているのです.

言語は,その話者たちのコミュニケーションのニーズと,その時代に利用可能な言語資源が複雑に絡み合って形作られていきます.ある意味では実に人間くさい代物なのです.ぜひこの議論を動画でもおさらいください.

2025-11-06 Thu

■ #6037. New Zealand English における冠詞の実現形 [new_zealand_english][article][glottal_stop][consonant][vowel][phonetics][allomorph][phonetics][pronunciation]

冠詞 (article) (定冠詞と不定冠詞)の実現形は,英語の変種によっても,話者個人によっても,状況によっても様々である.典型的な機能語として強形と弱形の variants をもっているという事情もあり,状況はますます複雑となる(cf. 「#3713. 機能語の強音と弱音」 ([2019-06-27-1])).さらに,後続語が子音で始まるか母音で始まるかによっても変異するので,厄介だ.

とりわけ定冠詞の実現形については,過去記事「#906. the の異なる発音」 ([2011-10-20-1]),「#907. 母音の前の the の規範的発音」 ([2011-10-21-1]),「#2236. 母音の前の the の発音について再考」 ([2015-06-11-1]) などを参照されたい.

さて,地域変種によっても実現形はまちまちのようだが,New Zealand English の状況を見てみよう.Bauer (391) によると,後続音によらず定冠詞は /ðə/ ,不定冠詞は /ə/ と発音される傾向があるという.ただし,母音が後続する場合にはたいてい声門閉鎖音がつなぎとして挿入される.

As in South African English . . . , the and a do not always have the same range of allomorphs in New Zealand English that they have in standard English. Rather, they are realised as /ðə/ and /ə/ independent of the following sound. Where the following sound is a vowel, a [ʔ] is usually inserted.

目下ニュージーランド滞在中で NZE を耳にしているが,そもそも冠詞は弱く発音されることが多く,どの変種でも variants が多々あることを前提としてもっていたので,さほどマークしていなかった.今後は意識して聞き耳を立てていきたい.

別途 LPD で the を引いてみると,次のようにある.

the strong form ðiː, weak forms ði, ðə --- The English as a foreign language learner is advised to use ðə before a consonant sound (the boy, the house), ði before a vowel sound (the egg, the hour). Native speakers, however, sometimes ignore this distribution, in particular by using ðə before a vowel (which in turn is usually reinforced by a preceding [ʔ]), or by using ðiː in any environment, though especially before a hesitation pause. Furthermore, some speakers use stressed ðə as a strong form, rather than the usual ðiː.

NZE に限らず,他の変種においても実現形は多様と考えてよいだろう.また,つなぎの声門閉鎖音の挿入も,ある程度一般的といってよさそうだ.

・ Bauer L. "English in New Zealand." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 5. Ed. Burchfield R. Cambridge: CUP, 1994. 382--429.

・ Wells, J C. ed. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2008.

2025-06-06 Fri

■ #5884. YouTube 「文藝春秋PLUS」にて英語史の魅力を語りました(後編) --- なぜ英語は世界のコトバになったのか? [notice][youtube][word_order][article][plural][prescriptive_grammar][sociolinguistics][helkatsu][hel_education][sobokunagimon]

昨日の記事に引き続き,5月30日(金)に YouTube 「文藝春秋PLUS 公式チャンネル」で公開された英語史トークの後編(26分ほど)をご紹介します.タイトルは「【ややこしい英語が世界的言語になるまで】文法が確立したのはたった250年前|an appleのanは「発音しやすくするため」ではない|なぜ複数形はsばかりなのか|言語の"伝播"=権力」です.以下,動画を観る時間がない方のために,文章としても掲載します.

後編では,さらに踏み込んで,文法の変化や,英語が今日の「世界語」としての地位を築くに至った背景など,より大きなテーマについてお話ししています.

まず,文法の変化についてです.現代英語の大きな特徴の一つに,語順が厳格に定まっている点が挙げられます.「主語+動詞+目的語」 (SVO) という型が基本であり,これを崩すと文の意味が通じなくなったり,非文法的になったりします.しかし,1000年前の古英語の時代に遡ると,語順はもっと自由でした.名詞の格変化が豊かだったため,語順を入れ替えても文の骨格が崩れにくかったのです.この点では,現代日本語と比較できるタイプだったのです.

現代英語のような固定語順の文法が確立したのは,歴史的にみれば比較的最近のことです.18世紀半ば,いわゆる規範文法の時代に,ロバート・ラウス (Robert Lowth) などの文法学者が「正しい」英語のルールを定め,それが教育を通じて社会に広まっていきました.それ以前は,互いに意味が通じればそれでよい,というような,より自然発生的で流動的な文法が主流だったのです.

次に,名詞の複数形の歴史も興味深いテーマです.現代英語では,名詞の複数形は99%近くが語尾に -s をつけることで作られます.これは非常に規則的で,学習者にとってはありがたい点かもしれません.しかし,これもまた歴史の産物です.古英語では,複数形の作り方は一様ではなく,現代ドイツ語のように,名詞の性や格変化の種類によって様々なパターンがありました.

その名残が,現代英語に不規則複数形として生き残っている単語群です.例えば,ox/oxen のように -n で複数形を作るタイプ,foot/feet や man/men のように語幹の母音を変化させるタイプ,そして child/children のように古英語の名詞複数語尾 -ru に由来する -r- を含むタイプなどです.これらの単語がなぜ現代まで不規則なまま残っているのかというと,きわめて基本的な日常語彙であり,使用頻度が高かったために,-s をつけるという新しい規則の波に飲み込まれずに抵抗し得たからです.

トークでは,不定冠詞 a/an の使い分けについても,学校文法で習う説明とは逆の歴史を明らかにしました.私たちは「次にくる単語が母音で始まるときには,発音の便宜上 an を使う」と学びます.しかし,歴史の真実はその逆です.もともと不定冠詞は,数字の one が弱まった an という形しかありませんでした.つまり,an apple こそがデフォルトの形だったのです.そして,an book のように次に子音が続く場合に,/n/ と /b/ という子音が連続して発音しにくいために,n のほうが脱落して a book という形が生まれたのです.まさに目から鱗が落ちるような事実ではありませんか.

そして最後に,最も大きな問い「なぜ英語は世界語になったのか?」についてお話ししました.この問いに対する答えは,言語そのものの性質 --- たとえば文法が単純だからとか,語彙が豊富だからとか --- とは,ほとんど無関係です.ある言語が国際的な地位を得るかどうかは,ひとえに,その言語を話す人々の社会がもつつ「力」,すなわち政治力,軍事力,経済力,技術力といったパワーに依存します.

英語の場合,18世紀以降のイギリス帝国の世界展開と,20世紀以降のアメリカ合衆国の圧倒的な国力が,その言語を世界中へ押し広げる原動力となりました.これは歴史上,漢文を国際語たらしめた古代中国の力や,ラテン語をヨーロッパの公用語としたローマ帝国の力と,まったく同じ原理です.言語の影響力は,常に社会的な力の勾配に沿って,上から下へと流れるのです.

このように,英語の歴史を学ぶことは,単なる暗記ではなく,現代英語の姿の背後にあるダイナミックな変化の過程と,その背景にある人々の社会や文化を理解する営みです.「言葉の乱れ」を嘆く声も,長い歴史のスケールで見れば,言語が生きている証としての自然な変化の1コマに過ぎないことが見えてきます.

トーク前編と合わせてご覧いただくことで,英語という言語の立体的な姿を感じていただけることと思います.

2025-05-08 Thu

■ #5855. ギリシア語由来の否定の接頭辞 a(n)- と英語の不定冠詞 a(n) の平行性 [senbonknock][sobokunagimon][heldio][article][greek][prefix][consonant][ogawashun][khelf][negative][oe]

5月28日に,khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)の協賛のもと,heldio にて小河舜さん(上智大学;X アカウント @scunogawa)とともに「英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック」をライヴでお届けしました.その様子をアーカイヴとしてすでに YouTube 版で公開していることは,先日の記事「#5851. 「英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック --- GW回 with 小河舜さん」のアーカイヴを YouTube で配信しました」 ([2025-05-04-1]) でお伝えした通りですが,数日遅れで heldio のアーカイヴとしても配信しました.音声だけで十分という方,ながら聴きしたいという方は,「#1439. 英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック --- GW回 with 小河舜さん」よりご聴取ください.本編は65分ほどの長さです.

今回の千本ノックで取り上げた素朴な疑問は15件ありましたが,その5件目(本編の26分18秒辺りから)に注目します.質問の趣旨としては「不定冠詞 an/a の使い分け(an apple vs. a pen)の現象は,ギリシア語由来の否定の接頭辞 an-/a- の現象と同じですか?」というものでした.質問者からのこの高度な指摘にむしろ勉強になった旨,小河さんとライヴでも触れた通りです.

調べてみると,確かに両者において,an- が歴史的には本来の形態素ですが,後ろに母音(あるいは h)で始まる要素が後続する場合には,音便により当該形態素より n が脱落し,a- という異形態が用いられています.きれいに平行的といえます.

Webster の辞書の第3版に所収の A Dictionary of Prefixes, Suffixes, and Combining Forms によると,ギリシア語由来の否定の接頭辞 a-, an- について次のように記述があります.

2a- or an- prefix [L & Gk; L a-, an-, fr. Gk --- more at UN-]: not: without <achromatic> <asexual> --- used chiefly with words of Gk or L origin; a- before consonants other than h and sometimes even before h, an- before vowels and usu. before h <ahistorical> <anesthesia> <anhydrous>

このなかで示唆されている通り,このギリシア語由来の否定の接頭辞は,英語本来の否定の接頭辞 un- とも同根である.ついでに同辞典より un- の項目も覗いておこう.

1un- prefix [ME, fr. OE; akin to OHG un- un-, ON ō, ū-, Goth un-, L in-, Gk a-, an-, Skt a-, an- un-, OE ne not]

古英語の否定辞 ne もこれらと同根であるから,つまるところ not, never, no などとも通じることになる.

寄せていただいた素朴な疑問からの展開でした.たいへん勉強になりました!

2025-04-15 Tue

■ #5832. なぜ古英語の語順規則は緩かったのか? --- 語順の2つの原理から考える [word_order][oe][pde][japanese][linearity][syntax][information_structure][article][cleft_sentence][passive][voice][discourse]

1週間前の火曜日に heldio にて「#1413. なぜ古英語の語順規則は緩かったのか?(年度初めの生配信のアーカイヴ)」を生配信し,土曜日にそれをアーカイヴとして配信しました.語順 (word_order) という,言語において一般的な話題なので,関心をもたれたのでしょうか,おかげさまでこの回は平均よりも多く聴取されています.ありがとうございます.

英語史の分野で「語順」といえば,現代英語では語順規則が厳しいのに,古英語では語順が比較的緩かったという対比が話題になります.当然ながら「それはなぜ?」という素朴な疑問が湧いてくるのではないでしょうか.今回の話題は,この疑問に直接答えるものではなく斜めからのアプローチではありますが,語順とは何かという根本的な問題には真正面から取り組んでいると思います.

以下に文章で要旨を示しますが,ぜひ臨場感のあるオリジナルの音声配信にてお聴きいただければと思います.

1. そもそも「語順」とは何か? --- 言語の線状性 (linearity)

私たちは,外国語学習,特に英語学習を通じて,語順の重要性を学びます.現代英語は SVO が基本であり,これを崩すと意味が変わったり,非文法的になったりすると教わってきました.例えば I eat a banana. が標準的であり,*Eat I a banana. や *A banana I eat. は通常許容されません(強調などの特殊な文脈は除きます).

一方,日本語では「私はバナナを食べる」 (SOV) が自然ですが,「バナナを私は食べる」 (OSV) や「食べる,私はバナナを」 (VSO) なども,不自然さはあるにせよ,文法的に間違いとは言い切れません.

では,なぜ言語には語順というものが存在するのでしょうか.それは,言語が音声(あるいは文字)を時間軸に沿って直線的に並べることによって成立しているからです.これを言語の線状性と呼びます.私たちの発音器官(とりわけ声帯)は基本的に1つしかないので,複数の単語を同時に発することはできません.したがって,単語を順番に並べるしかないのです.これは言語における避けられない制約であり,物理学における重力に相当するものと捉えることができます.

While the dog is running in the yard, the cat is sleeping on the hot carpet. (犬が庭で走っている間,猫はホットカーペットの上で寝ている)という文は,本来同時に起こっている出来事を表わしていますが,言語の線状性の制約から,どちらかの節を先に言わざるを得ません.もし仮に人間が2つの声帯をもち,同時に2つの単語を発することができたなら,言語の構造は全く異なっていたことでしょう.

2. 語順規則の2つの原理

単語を順番に並べなければならないという,語順の存在理由は分かりました.しかし,問題は「どのように並べるか」という語順規則です.世界の言語を見渡すと,この語順規則の背後には,大きく分けて2つの異なる原理が存在するように思われます.

(1) 文法上の語順規則

・ 文(センテンス)内部の要素(主語,動詞,目的語など)の配置を固定する原理

・ 要素の文法的な機能(主語なのか目的語なのか)を語順によって示す傾向が強い

・ 典型例:現代英語 (SVO),中国語 (SVO) など

・ 文法的な関係性が語順によって明確になる反面,語順の自由度は低い

(2) 文脈上の語順規則

・ 文(センテンス)よりも広い文脈(談話)における情報の流れを重視する原理.

・ 多くの場合,主題・テーマ・旧情報を先に提示し,それに続く形で叙述・レーマ・新情報を配置する傾向がある

・ 典型例:日本語,古英語

・ 情報の流れが自然になる一方,文内部の語順は比較的自由で「緩い」と見なされやすい.

日本語の「昔々あるところに,おじいさんとおばあさんがいました.おじいさんは山へ芝刈りに・・・」という語り出しを考えてみましょう.最初の文では,舞台設定の後,新情報である「おじいさんとおばあさん」が「が」を伴って現れます.次の文では,既知となった「おじいさん」が「は」(主題)を伴って文頭に来て,新しい情報(山へ芝刈りに行ったこと)が続きます.このように,日本語は文脈上の情報の流れ(主題→叙述,テーマ→レーマ,旧情報→新情報)を語順や助詞によって表現することを好む言語なのです.

3. 古英語は日本語型だった?

さて,ここで古英語に注目してみましょう.なぜ古英語の語順規則は緩かったのか? 答えは,古英語が現代英語のような「文法上の語順規則」を第1原理とする言語ではなく,むしろ日本語に近い「文脈上の語順規則」を重視する言語だったからです.

古英語では,文脈に応じて,主題や旧情報と見なされる要素を文頭に置き,新情報を後に続けるという語順が好まれました.そのため,文の内部構造だけを見ると,SVO も SOV も VSO も可能であり,現代英語話者の視点から見ると,語順が固定されておらず緩い,と感じられるわけです.しかし,それは「規則がない」わけではなく,異なる種類の原理に基づいているものと理解すべきものなのです.

4. 語順原理の転換と英語史上の変化

英語の歴史は,この「文脈上の語順規則」を重視するタイプから「文法上の語順規則」を重視するタイプへと,言語の基本的な性格が大きく転換した歴史であると捉えることができます.この転換は,中英語期に顕著になり,近代英語期にかけて固定化していきます.この大きな原理の転換は,単に語順だけでなく,英語の他の様々な文法項目にも連鎖的な影響を及ぼしました.

・ 冠詞 (article) の発達:古英語にも冠詞の萌芽はありましたが,現代英語ほど体系的なカテゴリーではありませんでした.旧情報を示す定冠詞 the や,新情報を示す不定冠詞 a/an が発達してきたのは,まさに情報構造 (information_structure) を語順以外の方法で示す必要性が高まったことと関連していると考えられます.

・ 強調構文 (cleft_sentence) の発達:古英語では,強調したい要素を比較的自由に文頭に移動させることが可能でした.しかし,語順が固定化されると,そのような移動が制限されます.その代わりとして,It is ... that ... のような強調構文が発達し,特定の要素を際立たせる機能をもつようになりました.

・ 受動態 (passive) の多用:古英語にも受動態は存在しましたが,使用頻度は現代英語ほど高くありませんでした.語順が固定化される中で,本来目的語となる要素(新情報になりやすい要素)を主題として文頭に置きたい場合に,受動態が便利な装置として頻繁に用いられるようになってきたものと考えられます.例えば,目的語を文頭に置く OSV の語順が使いにくくなった代わりに,目的語を主語にして文頭に置く受動態が好まれるようになった,という見方です.

5. まとめ

古英語の語順が現代英語から見て「緩い」のは,語順規則がなかったからではなく,現代英語とは異なる「文脈上の語順規則」という原理をより重視していたためです.この原理は,くしくも日本語と共通する部分が多くあります.英語の歴史は,この基本原理が大きく転換したダイナミックな過程であり,その影響は英文法の様々な側面に及んでいるのです.

古英語を学ぶ際には,現代英語の固定的な語順観から一旦離れ,「情報の流れ」という視点をもつことが,かえって理解の助けになるかもしれません.日本語母語話者にとっては,むしろ馴染みやすい側面もあるといえるでしょう.語順という切り口から,英語の奥深い歴史を探求してみるのも,おもしろいのではないでしょうか.

2024-12-20 Fri

■ #5716. 保坂先生との heldio 対談シリーズ --- 冠詞と do の文法化について [voicy][heldio][grammaticalisation][article][do-periphrasis][review][notice]

先日,保坂道雄先生(日本大学)と Voicy heldio にて文法化にまつわる対談を2回にわたってお届けしました.開拓社より2014年に出版されたご著書『文法化する英語』を参照しながら,英語史における文法化の具体的な事例について,著者じきじきに解説していただくという贅沢な企画です.2回の配信を以下に挙げておきます.

・ 「#1290. 冠詞の文法化 --- 保坂先生との対談」(2024年12月10日配信)

・ 「#1293. 助動詞 do の文法化 --- 保坂先生との対談」(2024年12月13日配信)

英語史上,きわめて重要な文法化の2つの事例,冠詞の創発と do 迂言法の発展について丁寧に解説していただきました.これらの問題に関心をもった方は,本ブログより article や do-periphrasis のタグの付された記事群を読んでいただければと思います.

上記配信内でも触れていますが,保坂先生との文法化をめぐる heldio 対談回は,以前にも1度配信しています.本ブログより「#5674. 保坂道雄先生との対談 --- ご著書『文法化する英語』(開拓社,2014年)より」 ([2024-11-08-1]) を,あるいは直接 heldio 「#1245. 保坂道雄先生との「文法化入門」対談 --- 「英語史ライヴ2024」より」をご参照ください.

おまけとして,今回の保坂先生との対談にあたって「#1298. 保坂先生とのアフタートークでコメント返し」(2024年12月18日配信)も収録しています.こちらは肩の凝らないおしゃべり回ですので,ぜひお聴きいただければ.

・ 保坂 道雄 『文法化する英語』 開拓社,2014年.

2024-12-13 Fri

■ #5709. 名詞句内部の修飾語句の並び順 [syntax][word_order][noun][adjective][determiner][article]

名詞句 (noun phrase) は,ときに修飾語句が多く付加され,非常に長くなることがある.例えば,やや極端にでっち上げた例ではあるが,all the other potentially lethal doses of poison that may be administered to humans は文法的である.

このように様々な修飾語句が付加される場合には,名詞句内での並び順が決まっている.適当に配置してはいけないのが英語統語論の規則だ.Fischer (79) の "Element order within the NP in PDE" と題する表を掲載しよう.

| Predeterminer | Determiner | Postdeterminer | Premodifier | Modifier | Head | Postmodifier |

| quantifiers | articles, | quantifiers, | adverbials, | adjectives, | noun, proper name, | prepositional |

| quantifiers, | numerals, specialized | some adjectives | adjuncts | pronoun | phrase, relative | |

| genitives, | adjectives | clause (some | ||||

| demonstratives, | adjectives) | |||||

| possessive/ | (quantifiers?) | |||||

| interrogative/ | ||||||

| relative pronouns | ||||||

| half | the | usual | price | |||

| any | other | potentially | embarrassing | details | ||

| a | pretty | unpleasant | encounter | |||

| both | our | meetings | with the | |||

| chairman | ||||||

| a | decibel | level | that made your | |||

| ears ache | ||||||

| these | two | criminal | activities |

主要部 (head) となる名詞を左右から取り囲むように様々なラベルの張られた修飾語句が配置されるが,全体としては主要部の左側への配置(すなわち前置)が優勢である.ここから,英語の名詞句内の語順は原則として「修飾語句+主要部名詞」であり,その逆ではないことが分かる.

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2024-07-29 Mon

■ #5572. 歴史的な動名詞の統語パターン --- Visser の目次より [syntax][gerund][word_order][case][genitive][article]

「#5565. 中英語期,目的語を従える動名詞の構造6種」 ([2024-07-22-1]) で取り上げたように,動名詞の統語論については,発達過程において様々な語順やパターンがあり得た.

今回は Visser を参照し,-ing 形に意味上の主語が明示される場合と,意味上の目的語が明示される場合について,歴史的な統語パターンを挙げたい.各パターンについて,Visser が節を立てているので,その目次 (Vol. 2, xiii--xiv) を掲げるのが早い.ただし,Visser が取り上げているのは -ing 形に関する事例であり,動名詞のみならず現在分詞の例も含まれていることに注意が必要である.

THE SUBJECT OF THE FORM IN -ING

Type 'They doubted the truth of the boy's being dead'

Type 'It's a curious thing your saying that'

Type 'From the arysing of the sonne'

Type 'At the sun rising'

Type 'I hope it's all right me coming in'

Type 'Everybody was talking about you going over there'

Type 'They knew about it being so serious'

Type 'Don't talk of there being no one to help'

THE OBJECT OF THE FORM IN -ING

A. Object before the form in -ing

Type 'Thou desirest the kynges mordryng'

Type 'Excuse his throwing into the water'

Type 'Restrayne yow of vengeance taking'

Type 'To þi broþur burieng fare''

Type 'Hope-giving phrases'; 'his heart-percing dart'

Type 'The maner of þis arke-making'

Type 'His love-making struck us as unconvincing'

Type 'To be present at the iudgement geuing'

Type 'In dyteys-making she bare the pryse'

B. Object after the form in -ing

Type 'A daye was limited for justifying of the bill'

Type 'Wenches sitt in the shade syngyng of ballads'

Type 'He went prechynge cristes lay'

Type 'I slow Sampsoun in shakynge the piler'

'The reading the book' versus 'the reading of the book'

動名詞の統語論と関連して,先日の Voicy heldio の配信回2つも参照.

・ 「#1150. 動名詞の統語論とその歴史 --- His/Him speaking Japanese surprised us all.」

・ 「#1151. 動名詞の統語論はさまざまだった」

・ Visser, F. Th. An Historical Syntax of the English Language. 3 vols. Leiden: Brill, 1963--1973.

2024-07-22 Mon

■ #5565. 中英語期,目的語を従える動名詞の構造6種 [syntax][gerund][me][preposition][word_order][case][genitive][article]

標記について,宇賀治 (274) により,Tajima (1985) を参照して整理した6種の構造が現代英語化した綴字とともに一覧されている.

I 属格目的語+動名詞,例: at the king's crowning (王に王冠を頂かせるとき)

II 目的語+動名詞,例: other penance doing (ほかの告解をすること)

III 動名詞+of+名詞,例: choosing of war (戦いを選択すること)

IV 決定詞+動名詞+of+名詞,例: the burying of his bold knights (彼の勇敢な騎士を埋葬すること)

V 動名詞+目的語,例: saving their lives (彼らの命を助けること)

VI 決定詞+動名詞+目的語,例: the withholding you from it (お前たちをそこから遠ざけること)

目的語が動名詞に対して前置されることもあれば後置されることもあった点,後者の場合には前置詞 of を伴う構造もあった点が興味深い.また,動名詞の主語が属格(後の所有格)をとる場合と通格(後の目的格)をとる場合の両方が混在していたのも注目すべきである.さらに,動名詞句全体が定冠詞 the を取り得たかどうかという問題も,統語論史上の重要なポイントである.

・ Tajima, Matsuji. The Syntactic Development of the Gerund in Middle English. Tokyo: Nan'un-Do, 1985.

・ 宇賀治 正朋 『英語史』 開拓社,2000年.

2024-07-02 Tue

■ #5545. 古英語の定冠詞・疑問詞の具格 [oe][article][determiner][interrogative_pronoun][case][instrumental][inflection][etymology][comparative_linguistics][germanic]

昨日の記事「#5544. 古英語の具格の機能,3種」 ([2024-07-01-1]) に引き続き,具格 (instrumental) について.古英語の定冠詞(あるいは決定詞) (definite article or determiner) の屈折表を「#154. 古英語の決定詞 se の屈折」 ([2009-09-28-1]) で示した.それによると,þȳ, þon といった独自の形態をとる具格形があったことがわかる.同様に疑問(代名)詞 (interrogative_pronoun) についても,その屈折表を「#51. 「5W1H」ならぬ「6H」」 ([2009-06-18-1]) に示した.そこには hwȳ という具格形が見られる.

Lass (144) によると,これらの具格形は比較言語学的にも,直系でより古い形に遡るのが難しいという.純粋な語源形が突きとめにくいようだ.この辺りの事情を,直接 Lass に語ってもらおう.

There are remains of what is usually called an 'instrumental' in the masculine and neuter sg; this term as Campbell remarks 'is traditional, but reflects neither their origin nor their prevailing use' (1959: §708n). The two forms are þon, þȳ, neither of which is historically transparent. In use they are most frequent in comparatives, e.g. þȳ mā 'the more' (cf. ModE the more, the merrier), and as alternatives to the dative in expressions like þȳ gēare '(in) this year'. There is probably some relation to the 'instrumental' interrogative hwȳ 'why?', which in sense is a real one (= 'through/by what?'), but the /y:/ is a problem; hwȳ has an alternative form hwī, which is 'legitimate' in that it can be traced back to the interrogative base */kw-/ + deictic */ei/.

比較言語学の手に掛かっても,すべての語源を追いかけて明らかにすることは至難の業のようだ.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

・ Campbell, A. Old English Grammar. Oxford: OUP, 1959.

2024-07-01 Mon

■ #5544. 古英語の具格の機能,3種 [oe][noun][pronoun][adjective][article][demonstrative][determiner][case][inflection][instrumental][dative][comparative_linguistics]

古英語には名詞,代名詞,形容詞などの実詞 (substantive) の格 (case) として具格 (instrumental) がかろうじて残っていた.中英語までにほぼ完全に消失してしまうが,古英語ではまだ使用が散見される.

具格の基本的な機能は3つある.(1) 手段や方法を表わす用法,(2) その他,副詞としての用法,(3) 時間を表わす用法,である.Sweet's Anglo-Saxon Primer (47) より,簡易説明を引用しよう.

Instrumental

88. The instrumental denotes means or manner: Gāius se cāsere, ōþre naman Iūlius 'the emperor Gaius, (called) Julius by another name'. It is used to form adverbs, as micle 'much, by far', þȳ 'therefore'.

It often expresses time when: ǣlċe ȝēare 'every year'; þȳ ilcan dæȝe 'on the same day'.

具格はすでに古英語期までに衰退してきていたために,古英語でも出現頻度は高くない.形式的には与格 (dative) の屈折形に置き換えられることが多く,残っている例も副詞としてなかば語彙化したものが少なくないように思われる.比較言語学的な観点からの具格の振る舞いについては「#3994. 古英語の与格形の起源」 ([2020-04-03-1]) を参照されたい.ほかに具格の話題としては「#811. the + 比較級 + for/because」 ([2011-07-17-1]) と「#812. The sooner the better」 ([2011-07-18-1]) も参照.

・ Davis, Norman. Sweet's Anglo-Saxon Primer. 9th ed. Oxford: Clarendon, 1953.

2024-04-26 Fri

■ #5478. 中英語における職業を表わす by-name とともに現われる定冠詞や前置詞とその脱落 [article][preposition][onomastics][personal_name][name_project][methodology][eme][by-name][latin][french][evidence][translation][me_dialect][sobokunagimon][occupational_term]

英語の姓には,原則として定冠詞 the の付くものがない.また,前置詞 of を含む名前もほとんどない.この点で,他のいくつかのヨーロッパ諸語とは異なった振る舞いを示す.

しかし歴史を振り返ると,中英語期には,職業名などの一般名詞に由来する姓は一般名詞として用いられていた頃からの惰性で定冠詞が付く例も皆無ではなかったし,of などの前置詞付きの名前なども普通にあった.中英語期の姓は,しばしばフランス語の姓の慣用に従ったこともあり,それほど特別な振る舞いを示していたわけでもなかったのだ.

ところが,中英語期の中盤から後半にかけて,地域差もあるようだが,この定冠詞や前置詞が姓から切り落とされるようになってきたという.Fransson (25) の説明を読んでみよう.

Surnames of occupation and nicknames are usually preceded by the definite article, le (masc.) or la (fem.); the two forms are regularly kept apart in the earlier rolls, but in the 15th century they are often confused. Those names in this book that are preceded by the have all been taken from rolls translated into English, and the has been inserted by the editor instead of le or la. The case is that the hardly ever occurs in the manuscripts; cf the following instances, which show the custom in reality: Rose the regratere 1377 (Langland: Piers Plowman 226). Lucia ye Aukereswoman 1275 1.RH 413 (L. la Aukereswomman ib. 426).

Sometimes de occurs instead of le; this is due to an error made either by the scribe or the editor. The case is that de has an extensive use in local surnames, e.g. Thom. de Selby. Other prepositions (in, atte, of etc.) are not so common, especially not in early rolls.

The article, however, is often left out; this is rare in the 12th and 13th centuries, but becomes common in the middle of the 14th century. There is an obvious difference between different parts of England: in the South the article precedes the surname almost regularly during the present period, while in the North it is very often omitted. The final disappearance of le takes place in the latter half of the 14th century; in most counties one rarely finds it after c1375, but in some cases, e.g. in Lancashire, le occurs fairly often as late as c1400. De is often retained some 50 years longer than le: in York it disappears in the early 15th century, in Lancashire it sometimes occurs c1450, while in the South it is regularly dropped at the end of the 14th century.

歴史的な過程は理解できたが,なぜ定冠詞や前置詞が切り落とされることになったのかには触れられていない.検討すべき素朴な疑問が1つ増えた.名前における前置詞については「#2366. なぜ英語人名の順序は「名+姓」なのか」 ([2015-10-19-1]) で少しく触れたことがある.そちらも参照されたい.

・ Fransson, G. Middle English Surnames of Occupation 1100--1350, with an Excursus on Toponymical Surnames. Lund Studies in English 3. Lund: Gleerup, 1935.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow