2014-10-08 Wed

■ #1990. 様々な種類の意味 [semantics][pragmatics][derivation][inflection][word_formation][idiom][suffix]

「#1953. Stern による意味変化の7分類 (2)」 ([2014-09-01-1]) で触れたが,Stern は様々な種類の意味を区別している.いずれも2項対立でわかりやすく,後の意味論に基礎的な視点を提供したものとして評価できる.そのなかでも論理的な基準によるとされる種々の意味の区別を下に要約しよう (Stern 68--87) .

(1) actual vs lexical meaning. 前者は実際の発話のなかに生じる語の意味を,後者は語(や句)が文脈から独立した状態で単体としてもつ意味をさす.後者は辞書的な意味ともいえるだろう.文法書に例文としてあげられる文の意味も,文脈から独立しているという点で,lexical meaning に類する.通常,意味は実際の発話のなかにおいて現われるものであり,単体で現われるのは上記のように辞書や文法書など語学に関する場面をおいてほかにない.actual meaning は定性 (definiteness) をもつが,lexical meaning は不定 (indefinite) である.

(2) general vs particular meaning. 例えば The dog is a domestic animal. の主語は集合的・総称的な意味をもつが,That dog is mad. の主語は個別の意味をもつ.すべての名前は,このように種を表わす総称的な用法と個体を表わす個別的な用法をもつ.名詞とは若干性質は異なるが,形容詞や動詞にも同種の区別がある.

(3) specialised vs referential meaning. ある語の指示対象がいくつかの性質を有するとき,話者はそれらの性質の1つあるいはいくつかに焦点を当てながらその語を用いることがある.例えば He was a man, take him for all in all. という文において man は,ある種の道徳的な性質をもっているものとして理解されている.このような指示の仕方がなされるとき,用いられている語は specialised meaning を有しているとみなされる.一方,He had an army of ten thousand men. というときの men は,各々の個性がかき消されており,あくまで指示的な意味 (referential meaning) を有するにすぎない.厳密には,referential meaning は specialised meaning と対立するというよりは,その特殊な現われ方の1つととらえるべきだろう.前項の particular meaning と 本項の specialised meaning は混同しやすいが,particular meaning は語の指示対象の範囲の限定として,specialised meaning は語の意味範囲の限定としてとらえることができる.

(4) tied vs contingent meaning. 前者は語と言語的文脈により指示対象が決定する場合の意味であり,後者はそれだけでは指示対象が決定せず話者やその他の状況をも考慮に入れなければならない場合の意味である.前者は意味論的な意味,後者は語用論的な意味といってもよい.

(5) basic vs relational meaning. 語が「語幹+接尾辞」から成っている場合,語幹の意味は basic,接尾辞の意味は relational といわれる.例えば,ラテン語 lupi は,狼という基本的意味を有する語幹 lup- と単数属格という統語関係的意味 (syntactical relational meaning) を有する接尾辞 -i からなる.統語関係的意味は接尾辞によって表わされるとは限らず,語幹の母音交替 ( Ablaut or gradation ) によって表わされたり (ex. ring -- rang -- rung) ,語順によって表わされたり (ex. Jack beats Jill. vs Jill beats Jack.) もすれば,何によっても表わされないこともある.一方,派生関係的意味 (derivational relational meaning) は,例えば like -- liken -- likeness のシリーズにみられるような -en や -ness 接尾辞によって表わされている.大雑把にいって,統語関係的意味と派生関係的意味は,それぞれ屈折接辞と派生接辞に対応すると考えることができる.

(6) word- vs phrase-meaning. あらゆる種類の慣用句 (idiom) や慣用的な文 (ex. How do you do?) を思い浮かべればわかるように,句の意味は,しばしばそれを構成する複数の単語の意味の和にはならない.

(7) autosemantic vs synsemantic meaning. 聞き手にイメージを喚起させる意図で発せられる表現(典型的には文や名前)は,autosemantic meaning をもつといわれる.一方,前置詞,接続詞,形容詞,ある種の動詞の形態 (ex. goes, stands, be, doing) ,従属節,斜格の名詞,複合語の各要素は synsemantic meaning をもつといわれる.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

2014-09-21 Sun

■ #1973. Meillet の意味変化の3つの原因 [semantic_change][semantics][register]

昨日の記事「#1972. Meillet の文法化」([2014-09-20-1]) で引用した Meillet は,文法化のみならず語の意味変化についても重要な考察を加えている.「#1109. 意味変化の原因の分類」 ([2012-05-10-1]) で部分的に触れたように,特に意味変化の原因について,まとまった記述を残している.

Meillet によれば,意味変化の一般的原因には,言語的原因,歴史的原因,社会的原因の3種が区別される.これらは互いにほとんど関連するところがないため,明確に区別すべきだと論じている.まずは,適用範囲の狭いといわれる言語的原因から.

Quelques changements, en nombre assez restreint du reste, procèdent de conditions proprement linguistiques : ils proviennent de la structure de certaines phrases, où tel mot paraît jouer un rôle spécial. (239)

ここに属するのは,いわゆる文法化の事例などである.フランス語の homme, chose, pas, rien, personne などにおいて,具体的な意味が抽象的・文法的な意味へと変化した例が挙げられている.2つめは,歴史的原因である.

Un second type de changements de sens est celui où les choses exprimées par les mots viennent à changer. (241)

これは指示対象あるいはモノの歴史的変化に依存する語の意味変化である.「#1953. Stern による意味変化の7分類 (2)」 ([2014-09-01-1]) でいえば,最初に挙げられている代用 (substitution) に相当する.フランス語の plume (ペン)は,かつては鉄筆を指示したが,後に鵞ペンを指示するようになったという例が挙げられている.名前は変わらないが,技術の発展などによりそれが指すモノが変わった場合に典型的にみられる意味変化である.3つめは社会的原因である.

... la répartition des hommes de même langue en groupes distincts: c'est de cette hétérogénéité des hommes de même langue que procèdent le plus grand nombre des changements de sens, et sans doute tous ceux qui ne s'expliquent pas par les causes précitées. (243--44)

Meillet はこの社会的な原因を最も重要な要因であると考えており,紙幅を割いて論じている.1つの言語の異なる変種においては,それぞれの話者集団に特有の register に彩られた言語使用が発達する.一般的な変種においてある意味をもって用いられている語が,特殊化した変種において別の意味をもって用いられることは,ごく普通に見られる.犯罪者集団の隠語,職業集団の俗語,専門集団の術語などである.各変種で発生した新しい語義が変種間の境を越えて往来すれば,結果としてその語の意味は変化(あるいは多義化)したことになる.

意味変化の3種類の原因と多くの例を挙げたうえで,Meillet は次のように締めくくっている.

Ces exemples, où l'on a remarqué seulement les plus gros faits et les plus généraux, permettent de se faire une idée de la manière dont les faits linguistiques, les faits historiques et les faits sociaux s'unissent, agissent et réagissent pour transformer le sens des mots; on voit que, partout, le moment essentiel est le passage d'un mot de la langue générale à une langue particulière, ou le fait inverse, ou tous les deux, et que, par suite, les changements de sens doivent être considérés comme ayant pour condition principale la différenciation des éléments qui constituent les sociétés. (271)

この碩学のすぐれて社会言語学的な立場が表明されている結論といえるだろう.

・ Meillet, Antoine. "Comment les mots changent de sens." Année sociologique 9 (1906). Rpt. in Linguistique historique et linguistique générale. Paris: Champion, 1958. 230--71.

2014-09-17 Wed

■ #1969. 語の意味の成分分析の問題点 [componential_analysis][semantics][semantic_field][pragmatics][cognitive_linguistics][prototype]

昨日の記事「#1968. 語の意味の成分分析」 ([2014-09-16-1]) で導入した componential_analysis には,語彙的関係や統語的・形態的な選択制限をスマートかつ経済的に記述できるという利点があるが,理論的には問題も多い.以下,厳しい批判を加えている Bolinger に主として依拠しながら,問題点を挙げる.

(1) 理想的な成分分析が可能な意味場は限られており,大部分の語彙にはうまく適用できないのではないかという疑問がある.昨日の bachelor, spinster, woman, wife などに関する意味場において相互の概念的関係を表現するには,[MALE], [FEMALE], [UNMARRIED], [MARRIED] (より経済的には [±MALE], [±MARRIED])など比較的少数の成分を用いれば済む.同様に,親族名称 (kinship terms) など閉じられた意味場では,一般に効力を発揮するだろう.しかし,たいていの意味場はもっと開かれているし,そのなかの語彙関係を少数の成分で(否,実際には多数の成分をもってしても)的確に分析するのは極めて困難である.例えば,bird の意味場において,sparrow, penguin, ostrich は,それぞれどのように成分分析すれば互いの関係をスマートに示せるだろうか.上位語の bird に [+CAN FLY] を認めるならば,下位語の penguin はその成分をキャンセルして [-CAN FLY] としなければならないだろう.また,別の下位語 ostrich のために [±CAN RUN FAST] などという成分を認めるべきかなどという問題も生じるかもしれない.

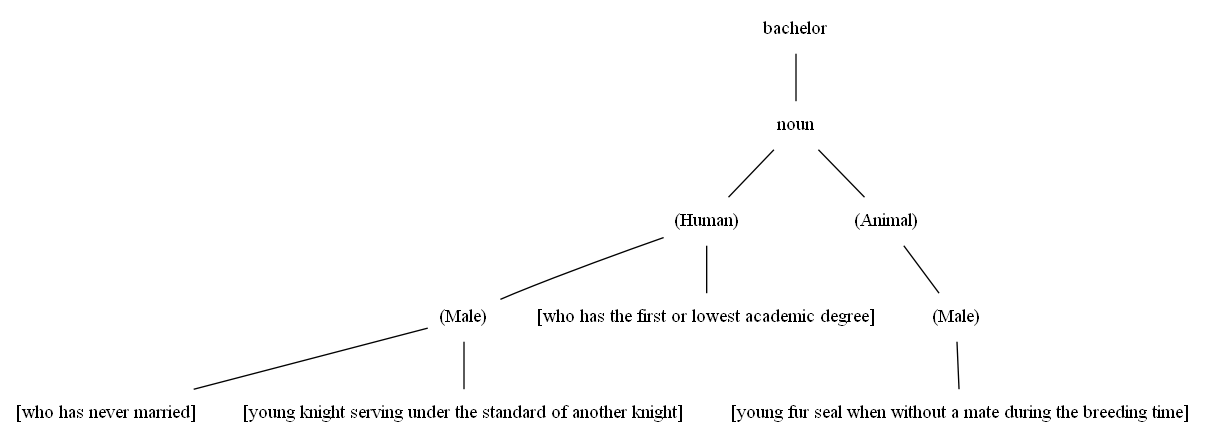

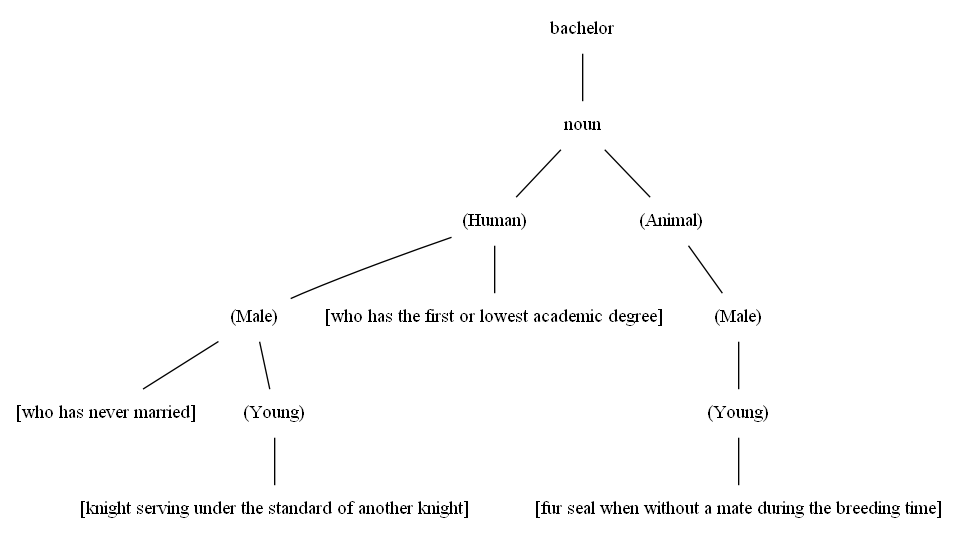

(2) 1つの語の多義をどのように表現するかという問題がある.bachelor には「独身男子」のほかにも,「若い騎士」「学士」「相手のいないオットセイ」の語義もある.これらを統一的に記述する方法はあるだろうか.Bolinger (557) は,Katz and Fodor の分析を引いて示している.

Katz and Fodor は,(Human), (Animal) などのかっこ付きで示される意味成分を "marker" と呼び,[who has never married] などの角かっこ付きで示される,その語義に固有の意味成分を "distinguisher" と呼んで区別した(distinguisher は,固有で特異であるとしてそれ以上分析することのできない要素とされているので,結局のところ,成分分析で押し切ることはできないことを認めてしまっていることになる!).しかし,どのレベルまでが marker で,どのレベルからが distinguisher かについて客観的に定めることは難しい.例えば,「若い騎士」と「相手のいないオットセイ」は,ともに「若い」という意味成分を共有していると考えられるので,(Young) という marker をくくり出すことも可能である.実際,Katz and Fodor は次のような成分分析を新提案として出している (Bolinger 559) .

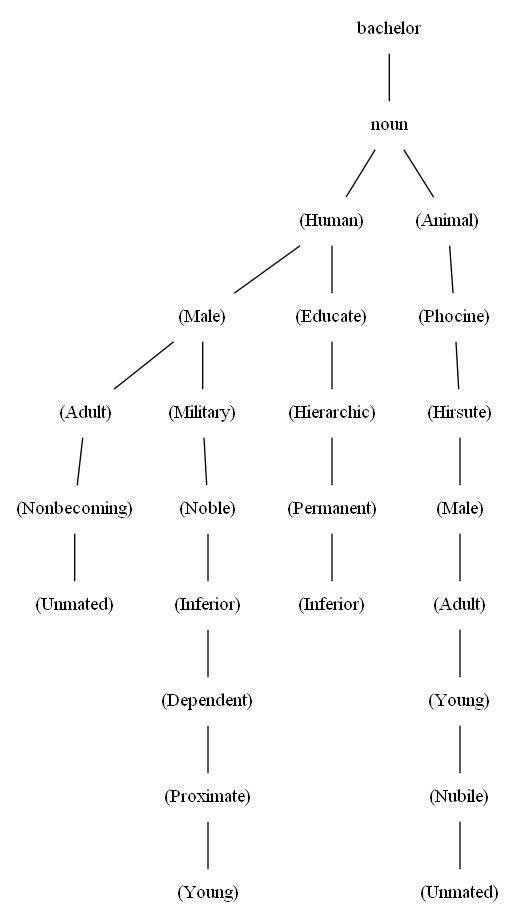

だが,そうなると,どこまでも marker を増やしていき,distinguisher を下へ下へと追いやることも可能となってくる.例えば,「若い騎士」と「学士」はそれぞれ騎士制度と学位制度のなかで「低い階位」の意味成分を共有しているので,(Hierarchic), (Inferior) などの marker を設定することができるともいえる.半ば強引に marker を増やしていくと,例えば Bolinger (563) が批判混じりに示しているように,次のようなばかげた分析が可能となってくる.

distinguisher の領分を広げれば成分分析の手法そのものの価値が問われるし,marker を増やしていけば,このようにばかげた結果になってしまう.

(3) "Henry became a bachelor in 1965." という文の bachelor の語義は「学士」以外にはありえないことを,話者は知っている.「(一度も結婚したことのない)独身男子」になる(ステータスを変える)ことはできないし,1965年には騎士制度はなかったし,Henry は人間だから,他の語義は自動的に排除される.しかし,とりわけ1965年に騎士制度はなかったという百科事典的な知識は,意味成分として埋め込むことは不適当のように思われる.semantics と pragmatics の境目,辞書的知識と百科事典的知識の境目という問題になってくるが,Katz and Fodor など成分分析を支持する生成意味論者はこの問題に正面から取り組んでいない.

(4) 成分分析では,成分の有無,プラスかマイナスかという二項対立を基盤にしており,程度,連続体,中心と周辺,プロトタイプ (prototype) といった概念を取り込むことができない.また,成分分析はあくまで静的な分析なので,比喩など意味生成の動的な過程を扱うことができない.(それなのに,Katz and Fodor は「生成」意味論を標榜することができるのか?)

上記の問題点は,新しく登場した認知意味論によって解決の糸口を与えられてゆく.とはいえ,成分分析のもつ記述のスマートさと経済性は,大きな魅力であり続けている.語の意味のすべてを成分の束として表現することは困難だとしても,特定の意味場において関連する語彙との異同関係を明示するという目的においては,威力を発揮する分析であることは間違いない.

・ Bolinger, D. "The Atomization of Meaning." Language 41 (1965): 555--73.

2014-09-16 Tue

■ #1968. 語の意味の成分分析 [componential_analysis][semantics][antonymy][hyponymy][syntax]

伝統的な意味論では,語の意味を,意味の成分あるいは意味の原子要素 (semantic components or primitives) へと分解する成分分析 (componential_analysis) の手法が採られてきた.これは,音素論における「音素は弁別素性の束である」という考え方を語の意味にも応用したものである.

意味成分は,音素における弁別素性と同様に,角括弧にくくって表現される(しばしば + か - かを付した二項対立として表わされるが,以下の例では符号はつけていない).例として,独身男子を表わす bachelor の成分分析を示そう.

bachelor [MALE] [ADULT] [HUMAN] [UNMARRIED]

ここでは,bachelor の概念的意味が4つの成分の組み合わせとして示されている.ただし,この組み合わせがすなわち bachelor の定義そのものであると解釈するのは早計である.むしろ,この組み合わせによって関連する他の語との語彙的・意味的関係が明確になるという点で,成分分析が有用なのである.例えば,独身女性を表わす spinster は,次のように成分分析されるだろう.

spinster [FEMALE] [ADULT] [HUMAN] [UNMARRIED]

この4つの成分の組み合わせが spinster の定義そのものであるというよりは,bachelor の成分分析と比較したときに相互関係が明確になるという利点が大きい.すなわち,bachelor と spinster はともに [ADULT] [HUMAN] [UNMARRIED] という点では共通するが,[MALE] か [FEMALE] かの1点における違いによって,全体として対義関係となることが明示されている.spinster と関連して,woman と wife の成分分析も示そう.

woman [FEMALE] [ADULT] [HUMAN]

wife [FEMALE] [ADULT] [HUMAN] [MARRIED]

spinster と woman は,後者が [UNMARRIED] という成分が関与しないという1点において異なっており,このことから後者は前者の上位語 (hypernym) であることが判明する.また,spinster と wife の関係については,[UNMARRIED] か [MARRIED] かという1点において対立を示す対義語ということになる.さらに,*The man is a wife. の意味的な矛盾も,主語が [MALE] の成分を含んでいるのに,述語は相容れない [FEMALE] の成分を含んでいることにより説明できる.改めて成分分析の最大の利点を指摘すると,語彙における反対関係 (antonymy),包摂関係 (hyponymy),矛盾関係など各種の関係が明示的に表現できるようになったことである.ほかにも,成分分析は,統語的・形態的な選択制限 (selection restriction) の記述にも力を発揮するなど,有用性が認められている.

Katz や Fodor などの生成意味論者は,成分分析の考え方を発展させて,例えば「#1801. homonymy と polysemy の境」 ([2014-04-02-1]) で覗いたような分析を進めた.どこまでもアリストテレス的な二分法で意味を扱おうとする彼らの成分分析の手法には,疑念と批判が向けられてきたし,理論的に難しい課題が指摘されてもいるが,意味分析の有力な方法の1つとして,いまだに影響力を失っていない.

以上,Saeed (259--66) を参照して執筆した.

・ Saeed, John I. Semantics. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

2014-09-13 Sat

■ #1965. 普遍的な語彙素 [lexicology][glottochronology][semantics][lexeme][componential_analysis]

先日の「#1961. 基本レベル範疇」 ([2014-09-09-1]) の記事で,基本語彙あるいは基礎語彙の話題を取り上げたときに,Swadesh の提案した基礎語彙に言及した.これは「#1128. glottochronology」 ([2012-05-29-1]) で挙げた100語からなる basic vocabulary のことであり,通言語的に普遍的な基礎語彙であると唱えられている.批判も多いが,比較言語学や歴史言語学では core vocabulary に関する影響力のある提案の1つと認識されている.

core vocabulary を同定するもう1つの試みとして,Wierzbicka や Goddard の提案がある.Swadesh の提案が比較言語学を基盤としているのに対し,Wierzbicka らの提案は意味論を基盤としている.意味論には,ちょうど音韻論において普遍的な弁別素性が仮定されるのと同様に,普遍的な意味の原子要素 (semantic primes) があるはずだと考え,それを同定しようとする伝統がある.これは,意味の成分分析 (componential_analysis) の伝統の延長線上にある.決して成功しているとはいえないが,意味のプリミティヴを追求するというこの魅力的な計画には,これまでも多くの研究者が参加してきた.Goddard もこの計画に魅せられた1人であり,使命感をもって次のように述べている(Cliff Goddard ("Lexico-Semantic Universals: A Critical overview." Linguistic Typology 5.1 (2001): 1--65. p. 3) から引用した Saeed (78) より).

Natural Semantic Metalanguage

. . . a 'meaning' of an expression will be regarded as a paraphrase, framed in semantically simpler terms than the original expression, which is substitutable without change of meaning into all contexts in which the original expression can be used . . . The postulate implies the existence, in all languages, of a finite set of indefinable expressions (words, bound morphemes, phrasemes). The meanings of these indefinable expressions, which represent the terminal elements of language-internal semantic analysis, are known as 'semantic primes'.

具体的には,Wierzbicka と Goddard により,次の60語が "universal semantic primes" として提案されている(Saeed 79).諸言語の語彙を比較調査した上でより抜かれた精鋭の語彙素だといわれる.

| Substantives: | I, you, someone/person, something, body |

| Determiners: | this, the same, other |

| Quantifiers: | one, two, some, all, many/much |

| Evaluators: | good, bad |

| Descriptors: | big, small |

| Mental predicates: | think, know, want, feel, see, hear |

| Speech: | say, word, true |

| Actions, events, movement: | do, happen, move, touch |

| Existence and possession: | is, have |

| Life and death: | live, die |

| Time: | when/time, now, before, after, a long time, a short time, for some time, moment |

| Space: | where/place, here, above, below |

| 'Logical' concepts: | not, maybe, can, because, if |

| Intensifier, augmentor: | very, more |

| Taxonomy: | kind (of), part (of) |

| Similarity: | like |

意味の原子要素を同定するということは一種のメタ言語,論理的な言語をもつことにつながるが,Wierzbicka や Goddard はそれをあえて自然言語の語彙素に対応させて示そうとした.できあがった語彙リストは,したがって,基礎語彙のリストというよりは,普遍的な意味の原子要素を反映する語彙素のリストとして提案されたのである.

・ Saeed, John I. Semantics. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

2014-09-10 Wed

■ #1962. 概念階層 [lexicology][semantics][hyponymy][terminology][semantic_field][cognitive_linguistics]

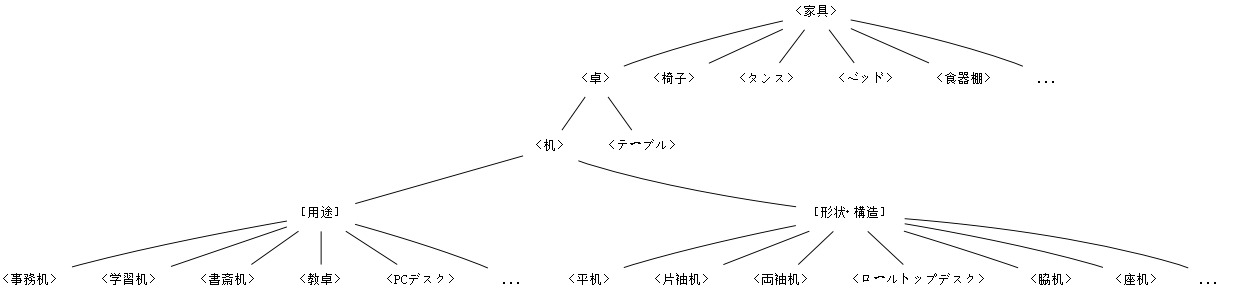

昨日の記事「#1961. 基本レベル範疇」 ([2014-09-09-1]) で,概念階層 (conceptual hierarchy) あるいは包摂関係 (hyponymy) という術語を出した.後者の包摂関係は語彙的な関係を念頭においた見方であり,「家具」と「いす」の例で考えれば,「家具」は「いす」の上位語 (hypernym) であるといわれ,「いす」は「家具」の下位語 (hyponym) であるといわれる.一方,前者の概念階層は概念間の関係を念頭においた見方であり,上位と下位の関係が幾重にも広がり,巨大なネットワークが展開されているととらえる.

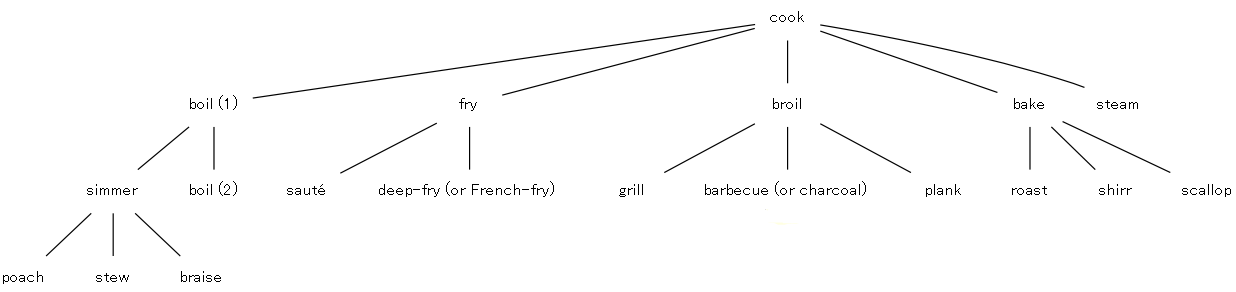

概念階層を理解するは,具体的にある意味場 (semantic_field) を取り上げ,関係を図示してみるのがよい.生物学における界 (kingdom),門 (phylum or division),綱 (class),目 (order),科 (family),属 (genus),種 (species) の分類図はよく知られた概念階層であるし,比較言語学の系統図 (family_tree) もその一種である.以下では中野 (17) に挙げられている日本語「家具」の意味場における概念階層と,英語 COOK(動詞)の意味場における概念階層を示す.

「家具」について[用途]と[形状・構造]というノードがあるが,これはそれ以下の分類が視点に基づいたものであることを示す.意味場に応じてあり得る視点も変わるだろうし,個人によっても異なる可能性があるので,上の図は1つのモデルと考えたい.

すぐに気づくように,概念階層は語彙学習にも役立つ.上記の COOK は動詞の例だが,FURNITURE, FRUIT, VEHICLE, WEAPON, VEGETABLE, TOOL, BIRD, SPORT, TOY, CLOTHING などの名詞の概念階層を描いてみると勉強になりそうだ.

・ 中野 弘三(編)『意味論』 朝倉書店,2012年.

2014-09-09 Tue

■ #1961. 基本レベル範疇 [lexicology][semantics][cognitive_linguistics][prototype][glottochronology][basic_english][hyponymy][terminology][semantic_field]

昨日の記事「#1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造」 ([2014-09-08-1]) の最後で,「語彙階層は,基本性,日常性,文体的威信の低さ,頻度,意味・用法の広さといった諸相と相関関係にある」と述べた.言語学では,しばしば「基本的な語彙」が話題になるが,何をもって基本的とするかについては様々な立場がある.直感的には,基本的な語彙とは,日常的に用いられ,高頻度で,子供にも早期に習得される語彙であると済ませることもできそうだし,確かにそれで大きく外れていないと思う.しかし,どこまでを基本語彙と認めるかという問題や,個別言語ごとに異なるものなのか,あるいは通言語的にある程度は普遍的なものなのかという問題もあり,易しいようで難しいテーマである.例えば,言語学史的には「#1128. glottochronology」 ([2012-05-29-1]) を提唱した Swadesh の綴字した基礎語彙に対して,猛烈な批判が加えられたという事例もあったし,実用的な目的で唱えられた Basic English (cf. 「#960. Basic English」 ([2011-12-13-1]),「#1705. Basic English で書かれたお話し」 ([2013-12-27-1])) とその基本語彙についても,疑念の目が向けられたことがあった.

基本的な語彙ということでもう1つ想起されるのは,認知意味論でしばしば取り上げられる基本レベル範疇 (Basic Level Category) である.語彙的な関係の1つに,概念階層 (conceptual hierarchy) あるいは包摂関係 (hyponymy) というものがある.例えば,「家具」という意味場 (semantic_field) を考えてみる.「家具」という包括的なカテゴリーの下に「いす」や「机」のカテゴリーがあり,それぞれの下に「肘掛けいす」「デッキチェア」や「勉強机」「パソコンデスク」などがある.さらに上にも下にも,そして横にもこのような語彙関係が広がっており,「家具」の意味場に巨大な語彙ネットワークが展開しているというのが,意味論や語彙論の考え方だ.ここで「家具」「いす」「肘掛けいす」という3段階の包摂関係について注目すると,最も普通のレベルは真ん中の「いす」と考えられる.「ちょっと疲れたから,いすに座りたいな」は普通だが,「家具に座りたいな」は抽象的で粗すぎるし,「肘掛けいすに座りたいな」は通常の文脈では不自然に細かすぎる.「いす」というレベルが,抽象的すぎず一般的すぎず,ちょうどよいレベルという感覚がある.ここでは,「いす」が Basic Level Category を形成しているといわれる.

では,この Basic Level Category は何によって決まるのだろうか.Taylor (52) は,プロトタイプ理論の権威 Rosch に依拠しながら,次のような機能主義的な説明を支持している.

Rosch argues that it is the basic level categories that most fully exploit the real-world correlation of attributes. Basic level terms cut up reality into maximally informative categories. The basic level, therefore, is the level in a categorization hierarchy at which the 'best' categories can emerge. More precisely, Rosch hypothesizes that basic level categories both

(a) maximize the number of attributes shared by members of the category;

and

(b) minimize the number of attributes shared with members of other categories.

「いす」は,その配下の様々な種類のいす,例えば「肘掛けいす」や「デッキチェア」と多くの共通の特性をもつ点で (a) にかなう.また,「いす」は,「机」や様々な種類の机,例えば「勉強机」や「パソコンデスク」と共有する特性は少ないので,(b) にかなう.これは「いす」を中心にして考えた場合だが,同じように「家具」あるいは「肘掛けいす」を中心に考えて (a) と (b) にかなうかどうかを検査してみると,いずれも「いす」ほどには両条件を満たさない.

Basic Level Category の語彙は,認知的に重要と考えられている.また,日常的に最もよく使われ,子供によって最初に習得され,大人も最も速く反応することが知られている.ある種の基本性を備えた語彙といえるだろう.

基本語彙の別の見方については,「#308. 現代英語の最頻英単語リスト」 ([2010-03-01-1]),「#1874. 高頻度語の語義の保守性」 ([2014-06-14-1]),「#1101. Zipf's law」 ([2012-05-02-1]) の記事も参照されたい.

・ Taylor, John R. Linguistic Categorization. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 2003.

2014-09-08 Mon

■ #1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造 [register][lexicology][loan_word][latin][french][greek][semantics][polysemy][lexical_stratification]

英語語彙に特徴的な三層構造について,「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]),「#335. 日本語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-28-1]),「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1]) などの記事でみてきた.三層構造という表現が喚起するのは,上下関係と階層のあるビルのような建物のイメージかもしれないが,ビルというよりは,裾野が広く頂点が狭いピラミッドのような形を想像するほうが妥当である.つまり,下から,裾野の広い低階層の本来語彙,やや狭まった中階層のフランス語彙,そして著しく狭い高階層のラテン・ギリシア語彙というイメージだ.

ピラミッドの比喩が適切なのは,1つには,高階層のラテン・ギリシア語彙のもつ特権的な地位と威信がよく示されているからだ.社会言語学的,文体的に他を圧倒するポジションについていることは,ビル型よりもピラミッド型のほうがよく表現できる.

2つ目として,それぞれの語彙の頻度が,ピラミッドにおける各階層の面積として表現できるからである.昨日の記事「#1959. 英文学史と日本文学史における主要な著書・著者の用いた語彙における本来語の割合」 ([2014-09-07-1]) でみたように,話し言葉のみならず書き言葉においても,本来語彙の頻度は他を圧倒している(なお,この分布は,「#1645. 現代日本語の語種分布」 ([2013-10-28-1]) でみたように,現代日本語においても同様だった).対照的に,高階層の語彙は頻度が低い.個々の語については反例もあるだろうが,全体的な傾向としては,各階層の頻度と面積とは対応する.もっとも,各階層の語彙量(異なり語数)ということでいえば,必ずしもそれがピラミッドの面積に対応するわけでない.最頻100語(cf. 「#309. 現代英語の基本語彙100語の起源と割合」 ([2010-03-02-1]) と最頻600語(cf. 「#202. 現代英語の基本語彙600語の起源と割合」 ([2009-11-15-1]))で見る限り,語彙量と面積はおよそ対応しているが,10000語というレベルで調査すると,「#429. 現代英語の最頻語彙10000語の起源と割合」 ([2010-06-30-1]) でみたように,上で前提としてきた3階層の上下関係は崩れる.

ピラミッドの比喩が有効と考えられる3つ目の理由は,ピラミッドにおける各階層の面積が,頻度のみならず,構成語のもつ意味と用法の広さにも対応しているからだ.本来語は相対的に卑近であり頻度も高いが,そればかりでなく,多義であり,用法が多岐にわたる.基本的な語義が同じ「与える」でも,本来語 give は派生的な語義も多く極めて多義だが,ラテン借用語 donate は語義が限定されている.また,give は文型として SVOiOd も SVOd to Oi も取ることができる(すなわち dative shift が可能だ)が,donate は後者の文型しか許容しない.ほかには「#112. フランス・ラテン借用語と仮定法現在」 ([2009-08-17-1]) で示唆したように,語彙階層が統語的な振る舞いに関与していると疑われるケースがある.

この第3の観点から,Hughes (43) は,次のようなピラミッド構造を描いた.

![]()

上記の3点のほかにも,各階層の面積と語の理解しやすさ (comprehensibility) が関係しているという見方もある.結局のところ,語彙階層は,基本性,日常性,文体的威信の低さ,頻度,意味・用法の広さといった諸相と相関関係にあるということだろう.ピラミッドの比喩は巧みである.

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-09-06 Sat

■ #1958. Hughes の語彙星雲 [register][semantics][lexicology][purism][semantic_field]

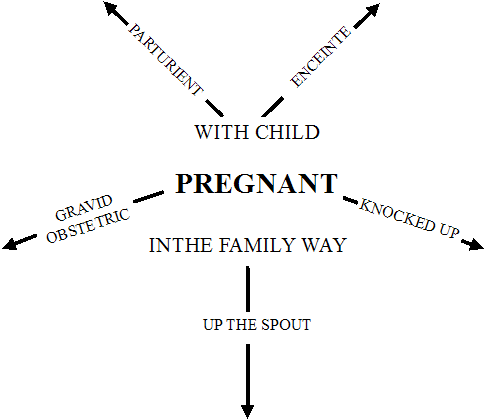

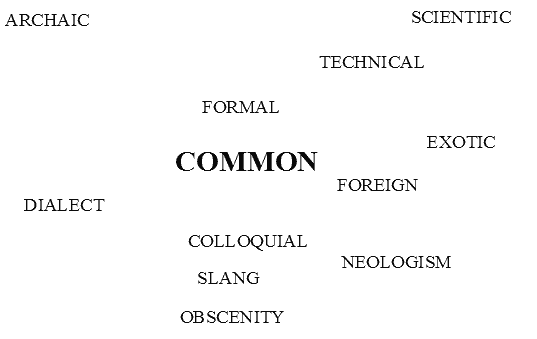

使用域 (register) による語彙と意味の広がりについて,「#611. Murray の語彙星雲」 ([2010-12-29-1]) で見た.そこで図示したように,COMMON (meaning) を中心に,LITERARY, FOREIGN, SCIENTIFIC, TECHNICAL, COLLOQUIAL, SLANG, DIALECTAL へと放射状に語彙と意味が広がっているというのが,Murray の捉え方だ.この図を具体的な語と意味で埋めてみよう.以下の図 (Hughes 5) では,「妊娠した」 (PREGNANT) という意味の場を巡って,種々の語句が然るべき位置を占めていることが示されている.

平面的に描かれがちな意味の場に使用域という次元を加え,語彙的な関係を立体的に描くことを可能とした点で,「語彙星雲」との見方は鋭い洞察だった.しかし,Hughes は語彙星雲のあり方も通時的な変化を免れることはないとし,現代英語の語彙星雲を形作るガス(使用域)は,ますます多岐に及んできていると論じた.Murray から100年たった今,別の図式が必要だと.そして,Murray の語彙星雲を次のように改良し,提示した (372) .

新しいラベルが加えられたり位置が変化したりしているが,Hughes (370--71) によれば,これは現代英語の語彙の特性を反映したものであるという.例えば,現代は借用語に対する純粋主義 (purism) が以前よりも弱まり,他言語から語彙が流入しやすくなってきたという点で,FOREIGN とは区別されるべき,取り込まれた外来要素を示すラベル EXOTIC が必要だろう(ただし,現代英語で全体的に語彙借用が減ってきていることについて,「#879. Algeo の新語ソース調査から示唆される通時的傾向」([2011-09-23-1]) を参照).また,SCIENTIFIC と TECHNICAL の語彙の増大や役割の変化に伴って,両者の位置関係についても再考が必要かもしれない.上記4ラベルが ARCHAIC とともに中心から離れた周辺に位置しているのは,これらの語彙の不透明さを反映している.さらに,現代はLITERARY というラベルの守備範囲が曖昧になってきていることから,そのラベルはなしとし,部分的に FORMAL, ARCHAIC, 場合によっては COLLOQUIAL, SLANG, OBSCENITY その他のラベルで補うのが妥当かもしれない.

この図に反映されていないものとして,他変種からの語彙がある.例えば,イギリス英語の語彙を念頭におくとき,そのなかに多く入り込んでくるようになったアメリカ英語の語彙 (americanism) やその他の変種の語彙はどのように位置づけられるだろうか.FOREIGN や EXOTIC とも違うし,伝統的な地域方言が念頭にある DIALECT とも異なる.

語彙構造も意味構造も時代とともに変化する.現代英語もその例に漏れない.現代英語でも,使用域として貼り付けるラベル,そして語彙星雲の図式が,再考を迫られている.

・Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-09-05 Fri

■ #1957. 伝統的意味論と認知意味論における概念 [cognitive_linguistics][terminology][semantics]

言語の意味とは,その指示対象 (referent) そのものではなく,それが喚起する概念 (concept) であるというのが,現代の意味論では主流の考え方である.しかし,この概念というものが一体どのようなものであるかは,今ひとつはっきりしない.この「意味=概念」説は,大きく2つの立場に分かれる.

「概念」説には2種あり,一つは形式(記号)論理学の流れを汲む伝統的意味論の考え方であり,もう一つは新しい認知言語学の考え方である.伝統的意味論では,概念(=意味)を,言語表現が表わす事物や事象がカテゴリー(類)として持つ特性の集合体と考える.たとえば,「犬」という語の概念(=意味)は,現実に存在する多様な犬がカテゴリーとして持つ特性(哺乳類である,四つ足で尻尾がある,人間によくなつく,など)の束であると考える.伝統的意味論での概念は,このように,それが適用される事物や事象の定義として働く.また,このような考え方の概念は,言語表現の音声形式と同じように,言語使用の場においては既存のものとして扱われ,そのため当の概念がどのような過程を経て形成されるかという概念形成の過程は問題にされない.

これに対し,言語研究において人間の認知能力を重要視する認知言語学では,言語表現が表わす概念は,概念化 (conceptualization) と呼ばれる,言語使用者の外界の捉え方 (construal) を反映した概念形成法によって形成されるものと考えられ,言語使用者から離れて存在する(既存の)ものとはみなされない.概念を固定したものでなく,言語使用者が使用の場に応じて弾力的に形成するものとするこの認知言語学の概念観は,概念(カテゴリー)の可変性や比喩表現に見られる概念の拡張を説明するのに非常に有効である.(中野,p. vii--viii)

伝統的意味論における概念を,もう少し詳しく説明すると,次のようになる(「#1931. 非概念的意味」 ([2014-08-10-1]) も参照).

概念 (concept) とは,事物や出来事をカテゴリー(類)として把握することから生まれる認識で,この認識は事物や出来事の個別的・差異的特徴を排除し,共通的・本質的要素を抽出することによって得られる.(中野,p. 13--14)

このように,伝統的意味論において,言語の意味(=概念)とは客観的,静的で形の定まった固体という風である.一方,新しい認知意味論の立場では,言語の意味(=概念)とは主観的,動的で形の定まらない流体という風である.

この30年ほどの間に急成長してきた認知言語学 (cognitive_linguistics) の分野には,生成文法などの学派には典型的な,これぞという金科玉条があるわけではない.言語(の意味)に関して様々な関心をもった複数の研究者が緩やかに呼応し,徐々に共通の認識を築きあげてきた結果,台頭してきた分野である.その緩やかな共通認識のいくつかとは,谷口 (7) によると,次のものである.

・ ことばは「記号」である.つまり,「形式」と「意味」の結びつきで成り立っている.

・ ことばの「形式」が違えば「意味」も必ず違う.

・ 同じ「形式」に結びつく意味が複数ある場合,その意味は相互に関連性を持ち,1つのまとまりを形成している.

・ ことばの「意味」は,客観的な意味内容だけに限らず,私がちがそれをどのように捉えたかという,認知的な作用も含んでいる.

4つ目で示唆されているように,認知意味論においては,ことばの意味(=概念)はあくまで流動的なものである.

・ 谷口 一美 『学びのエクササイズ 認知言語学』 ひつじ書房,2006年.

・ 中野 弘三(編)『意味論』 朝倉書店,2012年.

2014-09-03 Wed

■ #1955. 意味変化の一般的傾向と日常性 [semantic_change][semantics][synaesthesia][rhetoric][grammaticalisation][prediction_of_language_change][speed_of_change][function_of_language][subjectification]

語の意味変化が予測不可能であることは,他の言語変化と同様である.すでに起こった意味変化を研究することは重要だが,そこからわかることは意味変化の一般的な傾向であり,将来の意味変化を予測させるほどの決定力はない.「#1756. 意味変化の法則,らしきもの?」 ([2014-02-16-1]) で「法則」の名に値するかもしれない意味変化の例を見たが,もしそれが真実だとしても例外中の例外といえるだろう.ほとんどは,「#473. 意味変化の典型的なパターン」 ([2010-08-13-1]) や「#1109. 意味変化の原因の分類」 ([2012-05-10-1]),「#1873. Stern による意味変化の7分類」 ([2014-06-13-1]),「#1953. Stern による意味変化の7分類 (2)」 ([2014-09-01-1]) で示唆されるような意味変化の一般的な傾向である.

Brinton and Arnovick (87) は,次のような傾向を指摘している.

・ 素早く起こる.そのために辞書への登録が追いつかないこともある.ex. desultory (slow, aimlessly, despondently), peruse (to skim or read casually)

・ 具体的な意味から抽象的な意味へ.ex. understand

・ 中立的な意味から非中立的な意味へ.ex. esteem (cf. 「#1099. 記述の形容詞と評価の形容詞」 ([2012-04-30-1]),「#1100. Farsi の形容詞区分の通時的な意味合い」 ([2012-05-01-1]),「#1400. relational adjective から qualitative adjective への意味変化の原動力」 ([2013-02-25-1]))

・ 強い感情的な意味が弱まる傾向.ex. awful

・ 侮辱的な語は動物や下級の人々を表わす表現から.ex. rat, villain

・ 比喩的な表現は日常的な経験に基づく.ex. mouth of a river

・ 文法化 (grammaticalisation) の一方向性

・ 不規則変化は,言語外的な要因にさらされやすい名詞にとりわけ顕著である

もう1つ,意味変化の一般的な傾向というよりは,それ自体の特質と呼ぶべきだが,言語において意味変化が何らかの形でとかく頻繁に生じるということは明言してよい事実だろう.上で参照した Brinton and Arnovick も,"Of all the components of language, lexical meaning is most susceptible to change. Semantics is not rule-governed in the same way that grammar is because the connection between sound and meaning is arbitrary and conventional." (76) と述べている.また,意味変化の日常性について,前田 (106) は以下のように述べている.

とかく口語・俗語では意味の変化が活発である.これに比べると,文法の変化はかなりまれで,おそらく一生のうちでそれと気づくものはわずかだろう.音の変化は,日本語の「ら抜きことば」のように,もう少し気づかれやすいが,それでも意味変化の豊富さに比べれば目立たない.では,なぜ意味変化 (semantic change) はこれほど頻繁に起こるのだろうか.その答えは,おそらく意味変化がディスコース (discourse) における日常的営みから直接生ずるものだからである.

最後の文を言い換えて,前田 (130) は「意味の伝達が日常の言語活動の舞台であるディスコースにおけるコミュニケーション活動の目的と直接結びついているからである」と結論している.

・ Brinton, Laurel J. and Leslie K. Arnovick. The English Language: A Linguistic History. Oxford: OUP, 2006.

・ 前田 満 「意味変化」『意味論』(中野弘三(編)) 朝倉書店,2012年,106--33頁.

2014-09-01 Mon

■ #1953. Stern による意味変化の7分類 (2) [semantic_change][semantics][history_of_linguistics]

「#1873. Stern による意味変化の7分類」 ([2014-06-13-1]) と同じものだが,Stern の著書の解題を執筆した山中 (10) に,意味変化の7分類がずっとわかりやすくまとめられていた.

A 紊????荀????

i 代用 (substitution)

(a) 指示対象の物的変化: house, ship, telephone

(b) 指示対象に関する知識の変化: atom, electricity

(c) 指示対象に対する態度の変化: scholasticism, Home Rule

B 言語的要因

I 表現関係の推移

ii 蕁??ィ (analogy)

(a) 結合上の類推: reversion [reversal とすべきところに]

(b) 相関的類推: red letter day → black letter day

(c) 音韻的類推: bless ? bliss, start naked ? stark naked

iii 縮約 (shortening)

(a) 短縮: pop < popular concert, props < properties

(b) ??????: fall (of the leaf), (sewing) machine

II 指示関係の推移

iv 命名 (nomination)

(a) 命名: Kodak, Tono-Bungay ─┐

(b) 転移: labyrinth [of the ear], crane ├ 意図的

(c) 隠喩: the herring-pond (= the Atlantic) ─┘

v 荵∝Щ (transfer)

(a) 類似性に基づくもの: pyramid, saddle ('鞍部') ─┐

(b) その他の関係に基づくもの: pigtails (= China men) │

III 主観的関係の推移 │

vi 代換 (permutation) ├ 非意図的

(a) 材料から産物へ: copper, nickel │

(b) 容器から内容へ: tub, wardrobe │

(c) 部分から全体へ: bureau, dungeon etc. │

vii 適用 (adequation): horn ('角' → '角製の笛' → 'ホルン') ─┘

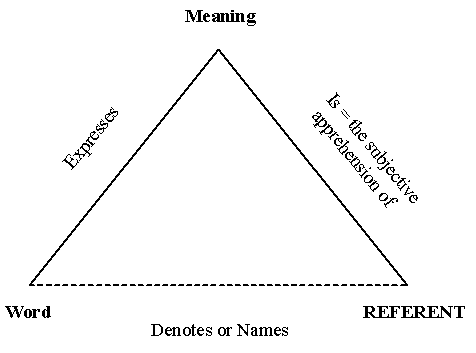

補足までに,Stern の意味論は基本的に Ogden and Richards の意味の三角形 (semiotic triangle; cf. 「#1769. Ogden and Richards の semiotic triangle」 ([2014-03-01-1])) に基づいたものだが,用語を少し改変して次のようにしている(山中,p. 10).

さて,山中 (10) は解題のなかで Stern の通時的意味論をむしろ共時的意味論に多大な貢献をしたものとして評価している.

iv (b)--(c) と,Stern 自身が揺れ (fluctuation) という総称を与えた v--vii は意図的/非意図的という基準一つによって区別され,現象的には同種・同範囲である.別の角度からいえば,彼が「本来の意味変化」とみている「揺れ」は,伝達の場面場面で起こる共時的な転義と本質的に変わりがないということになる.通時的意味論は当初から修辞学への傾斜をみせていたが,Stern の徹底した心理学主義によってその深い理由が明らかになったとみることができる.すべての言語変化は日常の言語活動に根ざしている,別のことばでいえば共時的原理によって説明可能であるという Paul (1880) のことばを,通時的意味論はこの段階ではっきり追認したことになる.

これは,Stern にとっても通時的意味論にとっても皮肉なことに,通時的意味論は共時的な意味の原理に包摂され,それに吸い込まれるようにして自らの意義を消滅させていったという評だ.さらに Stern にとって皮肉なことに,意味の原理を論じている著書の前半部分には,共時的意味論において考慮すべき数々の二項対立が列挙されており,その重要性が今でも色あせていないことだ.そこでは,知的意味/主情的意味,語義/実際的意味,内在的意味/偶有的意味,意味/適用範囲,基本的意味/関係的意味,イメージ/思考,自義/共義などの区別が論じられている.

しかし,Stern に通時的ではなく共時的な貢献を認めて終えるという評価は,やや酷かもしれない.というのは,「#1686. 言語学的意味論の略史」 ([2013-12-08-1]) でみたように,共時的な意味論ですら言語学において独自の領域をもっているかどうかと問われれば,答えは怪しいからだ.意味にせよ意味の変化にせよ,学際的なアプローチで研究されるのが普通になってきた.つまり,言語そのものが学際的なアプローチなしでは研究できなくなってきている.いずれにしても,意味論史における Stern の古典としての価値は否定できない.

・ 山中 桂一,原口 庄輔,今西 典子 (編) 『意味論』 研究社英語学文献解題 第7巻.研究社.2005年.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

2014-08-25 Mon

■ #1946. 機能的な観点からみる短化 [shortening][clipping][word_formation][morphology][function_of_language][style][semantics][semantic_change][euphemism][language_change][slang]

shortening (短化)という過程は,言語において重要かつ頻繁にみられる語形成法の1つである.英語史でみても,とりわけ現代英語で shortening が盛んになってきていることは,「#875. Bauer による現代英語の新語のソースのまとめ」 ([2011-09-19-1]) で確認した.関連して,「#893. shortening の分類 (1)」 ([2011-10-07-1]),「#894. shortening の分類 (2)」 ([2011-10-08-1]) では短化にも様々な種類があることを確認し,「#1091. 言語の余剰性,頻度,費用」 ([2012-04-22-1]),「#1101. Zipf's law」 ([2012-05-02-1]),「#1102. Zipf's law と語の新陳代謝」 ([2012-05-03-1]) では情報伝達の効率という観点から短化を考察した.

上記のように,短化は主として形態論の話題として,あるいは情報理論との関連で語られるのが普通だが,Stern は機能的・意味的な観点から短化の過程に注目している.Stern は,「#1873. Stern による意味変化の7分類」 ([2014-06-13-1]) で示したように,短化を意味変化の分類のなかに含めている.すべての短化が意味の変化を伴うわけではないかもしれないが,例えば private soldier (兵卒)が private と短化したとき,既存の語(形容詞)である private は新たな(名詞の)語義を獲得したことになり,その観点からみれば意味変化が生じたことになる.

しかし,private soldier のように,短化した結果の語形が既存の語と同一となるために意味変化が生じるというケースとは別に,rhinoceros → rhino, advertisement → ad などの clipping (切株)の例のように,結果の語形が新語彙項目となるケースがある.ここでは先の意味での「意味変化」はなく意味論的に語るべきものはないようにも思われるが,rhinoceros と rhino の意味の差,advertisement と ad の意味の差がもしあるとすれば,これらの短化は意味論的な含意をもつ話題ということになる.

Stern (256) は,短化を形態的な過程であるとともに,機能的な観点から重要な過程であるとみている.実際,短化の原因のなかで最重要のものは,機能的な要因であるとまで述べている.Stern (256) の主張を引用する.

Starting with the communicative and symbolic functions, I have already pointed out above . . . that brevity may conduce to a better understanding, and too many words confuse the point at issue; the picking out of a few salient items may give a better idea of the topic than prolonged wallowing in details; the hearer may understand the shortened expression quicker and better.

The expressive function is partly covered by signals, but a shortened expression by itself may, owing to its unusual and perhaps ungrammatical, form, reflect better the speaker's emotional state and make the hearer aware of it. Clippings are very often intended to make the words express sympathy or endearment towards the persons addressed; nursery speech abounds in nighties, tootsies, etc., and clippings of proper names, transforming them into pet names, are often due to a similar desire for emotive effects . . . . The numerous shortenings (clippings) in slang and cant often aim at a humourous effect.

Conciseness and brevity increase vivacity, and thus also the effectiveness of speech; brevity is the soul of wit; the purposive function may consequently be better served by shortened phrases.

形態論や情報理論のいわば機械的な観点から短化をみるにとどまらず,言語使用の目的,表現力,文体といった機能的な側面から短化をとらえる洞察は,Stern の面目躍如たるところである.形態を短化することでむしろ新機能が付加される逆説が興味深い.

引用の文章で言及されている婉曲表現 nighties と関連して,「#908. bra, panties, nightie」 ([2011-10-22-1]) 及び「#469. euphemism の作り方」 ([2010-08-09-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

2014-08-10 Sun

■ #1931. 非概念的意味 [semantics][register][taboo][information_structure]

言語表現の意味には,概念的意味 (conceptual meaning) と非概念的意味が区別される.概念的意味は辞書的意味 (dictionary meaning) とも呼ばれ,事物や出来事をカテゴリーとしてとらえ,それ自身をそれ以外のものから区別するために抽出された共通的・本質的要素の集合からなる.一方,非概念的意味は,文脈や場面,あるいはそれとの連想により概念的意味に付け加えられる意味である.非概念的意味には,いくつかの種類が認められる.Leech を参照して概説している中野 (23--26) に拠って,簡単に解説を施そう.

(1) 内包的意味 (connotative meaning)

語の指示対象から連想される指示対象特有の特性を指す ("what is communicated by virtue of what language refers to") .例えば,英語の mother や日本語の「母」は,その指示対象から連想される優しさ,愛情深さ,慈愛の深さなどのイメージを伴うかもしれない.しかし,これらのイメージは主観的で人によって異なるものであり,言語社会のなかで一定していない.

(2) 社会的意味 (social [stylistic] meaning)

言語使用の背景にある社会的状況について伝えられる内容 ("what is communicated of the social circumstances of language use") .年齢層,性別,社会階層,地域,媒体,堅苦しさ,敬意,文化などの社会的背景を反映したもの.文体的特徴として表出するので,文体的意味とも呼ばれる.英語の father, dad, daddy, pop, papa や日本語の「父」「お父さん」「お父ちゃん」「親父」「パパ」「おとう」などは,それぞれ異なる register に属しており,使用の社会的背景が異なっている.「#839. register」 ([2011-08-14-1]),「#227. 英語変種のモデル」 ([2009-12-10-1]),「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]),「#849. 話し言葉と書き言葉 (2)」 ([2011-08-24-1]) なども参照.

(3) 情緒的意味 (affective meaning)

使用者の感情や態度について伝えられる内容 ("what is communicated of the feelings and attitudes of the speaker/writer") .Stop being so bloody arrogant." や "What a darling little dress!" におえるイタリック部分のように,話し手の愛情や嫌悪が表わされるような場合.

(4) 投影された意味 (reflected meaning)

その表現の別の語義からの連想により生じる意味 ("what is communicated through association with another sense of the same expression") .多義語が用いられる際に生じる重層的な意味を指し,忌詞や禁句 (taboo) に典型的に見られる.例えば,婚礼の際には「切る」「去る」「分かれる」はそれぞれの概念的意味の裏に,離婚を想起させる投影された意味が感じられる.英語の cock, ass なども性的に投影された意味を伴うために,変種によっては避けられる傾向がある.

(5) 連語的意味 (collocative meaning)

連語として共起することが多いために関連づけられる内容 ("what is communicated through association with words which tend to occur in the environment of another word") .例えば,典型的に pretty は女性を表わす語と共起し,handsome は男性を表わす語と共起する.両語の概念的意味は「器量のよい」で一致するが,連語的意味は異なる.連語的意味により,前者はかわいらしさ,後者は端正な顔立ちという特性を含意する.

上記 (1) から (5) は,語がもつ意味であり,まとめて連想的意味 (associative meaning) とも呼ばれる.一方,次の主題的意味は文がもつ意味である.

(6) 主題的意味 (thematic meaning)

語順や強調によって作り出される情報構造 (information structure) に関わる意味 ("what is communicated by the way in which the message is organized in terms of order and emphasis") .例えば,次の各ペアにおいて,1つ目と2つ目の文では,情報の新旧や力点の置き方によって主題的意味が異なる.

(a) John owns the biggest shop in London.

(b) The biggest shop in London belongs to John.

(c) I like Danish cheese best.

(d) Danish cheese, I like best.

(e) Bill uses an electric razor.

(f) The kind of razor that Bill uses is an electric one.

以上の非概念的意味,とりわけ語に属する (1)--(6) の連想的意味は,概念的意味のように固定的ではなく,使用者や使用の背景により変異しうるため,辞書に記載されることはない.例外として,(2) の社会的意味は比較的語彙の中で安定しているので,辞書にレーベルを伴って記載されることも多い.

・ 中野 弘三 「意味とは」『意味論』(中野弘三(編)) 朝倉書店,2012年,1--27頁.

2014-07-19 Sat

■ #1909. 女性を表わす語の意味の悪化 (2) [semantic_change][gender][lexicology][semantics][euphemism][taboo][sapir-whorf_hypothesis]

昨日の記事「#1908. 女性を表わす語の意味の悪化 (1)」 ([2014-07-18-1]) で,英語史を通じて見られる semantic pejoration の一大語群を見た.英語史的には,女性を表わす語の意味の悪化は明らかな傾向であり,その背後には何らかの動機づけがあると考えられる.では,どのような動機づけがあるのだろうか.

1つは,とりわけ「売春婦」を指示する婉曲的な語句 (euphemism) の需要が常に存在したという事情がある.売春婦を意味する語は一種の taboo であり,間接的にやんわりとその指示対象を指示することのできる別の語を常に要求する.ある語に一度ネガティヴな含意がまとわりついてしまうと,それを取り払うのは難しいため,話者は手垢のついていない別の語を用いて指示することを選ぶのである.その方法は,「#469. euphemism の作り方」 ([2010-08-09-1]) でみたように様々あるが,既存の語を取り上げて,その意味を転換(下落)させてしまうというのが簡便なやり方の1つである.日本語の「風俗」「夜鷹」もこの類いである.関連して,女性の下着を表わす語の euphemism について「#908. bra, panties, nightie」 ([2011-10-22-1]) を参照されたい.

しかし,Schulz の主張によれば,最大の動機づけは,男性による女性への偏見,要するに女性蔑視の観念であるという.では,なぜ男性が女性を蔑視するかというと,それは男性が女性を恐れているからだという.恐怖の対象である女性の価値を社会的に(そして言語的にも)下げることによって,男性は恐怖から逃れようとしているのだ,と.さらに,なぜ男性は女性を恐れているのかといえば,根源は男性の "fear of sexual inadequacy" にある,と続く.Schulz (89) は複数の論者に依拠しながら,次のように述べる.

A woman knows the truth about his potency; he cannot lie to her. Yet her own performance remains a secret, a mystery to him. Thus, man's fear of woman is basically sexual, which is perhaps the reason why so many of the derogatory terms for women take on sexual connotations.

うーむ,これは恐ろしい.純粋に歴史言語学的な関心からこの意味変化の話題を取り上げたのだが,こんな議論になってくるとは.最初に予想していたよりもずっと学際的なトピックになり得るらしい.認識の言語への反映という観点からは,サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) にも関わってきそうだ.

・ Schulz, Muriel. "The Semantic Derogation of Woman." Language and Sex: Difference and Dominance. Ed. Barrie Thorne and Nancy Henley. Rowley, MA: Newbury House, 1975. 64--75.

2014-07-18 Fri

■ #1908. 女性を表わす語の意味の悪化 (1) [semantic_change][gender][lexicology][semantics]

「#473. 意味変化の典型的なパターン」 ([2010-08-13-1]) の (3) で示した意味の悪化 (pejoration) は,英語史において例が多い.良い意味,あるいは少なくとも中立的な意味だった語にネガティヴな価値が付される現象である.これまでの記事としては,「#505. silly の意味変化」 ([2010-09-14-1]),「#683. semantic prosody と性悪説」 ([2011-03-11-1] ),「#742. amusing, awful, and artificial」 ([2011-05-09-1]) などで具体例を見てきた.

しかし,英語史における意味の悪化の例としてとりわけよく知られているのは,女性を表わす語彙だろう.英語史を通じて,「女性」を意味する語群は,軒並み侮蔑的な含蓄的意味 (connotation) を獲得していく傾向を示す.「女性」→「性的にだらしない女性」→「娼婦」というのが典型的なパターンである.この話題を正面から扱った Schulz の論文 "The Semantic Derogation of Woman" によると,「女性を表わす語の堕落」がいかに一般的な現象であるかが,これでもかと言わんばかりに示される.3箇所から引用しよう.

Again and again in the history of the language, one finds that a perfectly innocent term designating a girl or woman may begin with totally neutral or even positive connotations, but that gradually it acquires negative implications, at first perhaps only slightly disparaging, but after a period of time becoming abusive and ending as a sexual slur. (82--83)

. . . virtually every originally neutral word for women has at some point in its existence acquired debased connotations or obscene reference, or both. (83)

I have located roughly a thousand words and phrases describing women in sexually derogatory ways. There is nothing approaching this multitude for describing men. Farmer and Henley (1965), for example, have over five hundred terms (in English alone) which are synonyms for prostitute. They have only sixty-five synonyms for whoremonger. (89)

Schulz の論文内には,数多くの例が列挙されている.論文内に現われる99語をアルファベット順に並べてみた.すべてが「性的に堕落した女」「娼婦」にまで意味が悪化したわけではないが,英語史のなかで少なくともある時期に侮蔑的な含意をもって女性を指示し得た単語群である.

abbess, academician, aunt, bag, bat, bawd, beldam, biddy, Biddy, bitch, broad, broadtail, carrion, cat, cleaver, cocktail, courtesan, cousin, cow, crone, dame, daughter, doll, Dolly, dolly, dowager, drab, drap, female, flagger, floozie, frump, game, Gill, girl, governess, guttersnipe, hack, hackney, hag, harlot, harridan, heifer, hussy, jade, jay, Jill, Jude, Jug, Kitty, kitty, lady, laundress, Madam, minx, Miss, Mistress, moonlighter, Mopsy, mother, mutton, natural, needlewoman, niece, nun, nymph, nymphet, omnibus, peach, pig, pinchprick, pirate, plover, Polly, princess, professional, Pug, quean, sister, slattern, slut, sow, spinster, squaw, sweetheart, tail trader, Tart, tickletail, tit, tramp, trollop, trot, twofer, underwear, warhorse, wench, whore, wife, witch

重要なのは,これらに対応する男性を表わす語群は必ずしも意味の悪化を被っていないことだ.spinster (独身女性)に対する bachelor (独身男性),witch (魔女)に対する warlock (男の魔法使い)はネガティヴな含意はないし,どちらかというとポジティヴな評価を付されている.老女性を表わす trot, heifer などは侮蔑的だが,老男性を表わす geezer, codger は少々侮蔑的だとしてもその度合いは小さい.queen (女王)は quean (あばずれ女)と通じ,Byron は "the Queen of queans" などと言葉遊びをしているが,対する king (王)には侮蔑の含意はない.princess と prince も同様に対照的だ.mother, sister, aunt, niece の意味は堕落したことがあったが,対応する father, brother, uncle, nephew にはその気味はない.男性の職業・役割を表わす footman, yeoman, squire は意味の下落を免れるが,abbess, hussy, needlewoman など女性の職業・役割の多くは professional その語が示しているように,容易に「夜の職業」へと転化してゆく.若い男性を表わす語は boy, youth, stripling, lad, fellow, puppy, whelp など中立的だが,doll, girl, nymph は侮蔑的となる.

女性を表わす固有名詞も,しばしば意味の悪化の対象となる.また,男性と女性の両者を指示することができる dog, pig, pirate などの語でも,女性を指示する場合には,ネガティヴな意味が付されるものも少なくない.いやはや,随分と類義語を生み出してきたものである.

・ Schulz, Muriel. "The Semantic Derogation of Woman." Language and Sex: Difference and Dominance. Ed. Barrie Thorne and Nancy Henley. Rowley, MA: Newbury House, 1975. 64--75.

2014-06-27 Fri

■ #1887. 言語における性を考える際の4つの視点 [gender][gender_difference][terminology][sociolinguistics][semantics][singular_they]

「#1883. 言語における性,その問題点の概観」 ([2014-06-23-1]) で,Hellinger and Bussmann の著書を参照した.そこで,言語における性の見方を整理したが,とりわけ感心したのが,性を話題にするときに数種類の性を区別すべきだという知見である.具体的には grammatical gender, lexical gender, referential gender, social gender の4種を区別する必要がある.以下,Hellinger and Bussmann (7--11) を参照しながら概説する.

言語における性という場合に,まず思い浮かぶのは grammatical gender だろう.古英語では男性・女性・中性の3性があり,すべての名詞が原則的にはいずれかの性に割り振られていた.名詞のクラスの一種として,通常は2?3種類ほどが区別され,統語的な一致を伴うなどの特徴がある.The World Atlas of Language Structures Online より Number of Genders, Sex-based and Non-sex-based Gender Systems, Systems of Gender Assignment などで世界の言語の分布を見渡しても,性というカテゴリーは,印欧語族などの特定の語族に限定されず,世界各地に点在している.

次に,lexical gender という区分がある.言語外の属性である自然性や生物学的性を参照するが,本質的には語彙的・意味的に規定される性である.例えば,father と mother は,それぞれ [+male] と [+female] という意味素性をもち,"gender-specific" な語とされる.一方で,citizen, patient, individual などにおいて,lexical gender は "gender-indefinite" あるいは "gender-neutral" とされる.gender-specific な語は,代名詞で受けるときに he あるいは she が意味素性にしたがって選択されるのが普通である.grammatical gender と lexical gender はたいてい一致するが,ドイツ語 Individuum (n), Person (f) のように両者が一致しないものも散見される.このような場合,常にそうというわけではないが,代名詞の選択は grammatical gender によってなされる.

3つ目は,referential gender である.これは,ある語が現実世界で指示する対象の生物学的性である.例えば,先に挙げたドイツ語 Person は grammatical gender は女性,lexical gender は性不定だが,この語が実際の文脈においてある男性を指示していれば,referential gender は男性ということになる.同様に,ドイツ語で Mädchaen für alles "girl for everything" (何でも屋,便利屋)は男性についても用いられるが,その場合 Mädchaen は grammatical gender は中性,lexical gender は女性,referential gender は男性ということになる.これを代名詞で受ける際には,grammatical gender による場合と referential gender による場合がある.

最後に,social gender とは,社会的な役割・特性として負わされる男女の二分法である.人を表わす名詞,特に職業に関わる名詞は,男女いずれかの social gender を負わされていることが多い.例えば英米では,lawyer, surgeon, scientist はしばしば男性であることが期待され,secretary, nurse, schoolteacher は女性であることが期待される.一方,pedestrian, consumer, patient などの一般的な名詞は,代名詞 he で照応することが伝統的な慣習であることから,その social gender は男性であると解釈できる.social gender には,その社会における性のステレオタイプがよく表わされる.

英語史における言語上の性の話題としては,文法性の消失という問題がある.文法性が自然性へ置換されたというような場合に関与するのは,grammatical gender, lexical gender, referential gender の3種だろう.一方,generic 'he' や singular they の問題が関係するのは,lexical gender, referential gender, social gender の3種だろう.ともに「言語の性」にまつわる問題だが,注目する「性」は異なっているということになる.

・ Hellinger, Marlis and Hadumod Bussmann, eds. Gender across Languages: The Linguistic Representation of Women and Men. Vol. 1. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2001.

2014-06-14 Sat

■ #1874. 高頻度語の語義の保守性 [semantics][semantic_change][frequency][speed_of_change]

高頻度語は形態的に保守的だということは,よくいわれる.頻度と変化しやすさとの間に相関関係があるらしいことは,最近でも「#1864. ら抜き言葉と頻度効果」 ([2014-06-04-1]) で取り上げ,その記事の冒頭にもいくつかの記事へのリンクを張った (##694,1091,1239,1242,1243,1265,1286,1287,1864) .高頻度語はたいてい日常的な基礎語でもあることから,この問題は基礎語彙の保守性という問題にも通じる.実際,「#1128. glottochronology」 ([2012-05-29-1]) は,基礎語彙の保守性を前提とした仮説だった.

語という記号 (sign) や形態という記号表現 (signifiant) について頻度と保守性の関係が指摘されるのならば,記号のもう1つの側面である記号内容 (signifié),すなわち意味についても同様の関係が指摘されてもよいはずだ.高頻度の意味であれば,変化しにくいといえるのではないか.Stern (185) は,高頻度語の語義の保守性に触れている.

It is well known that the most common words of a language retain most tenaciously old and otherwise discarded forms and inflections. It is reasonable to assume that a strong tradition has similar effects on meanings. Note, however, that the retention of one or more old meanings is no obstacle to the acquisition of new ones: frequency is only a conservative factor for already established meanings.

高頻度の語義をもつ語はそれ自体が高頻度であり,日常的な基礎語である確率が高く,全体として保守的だろうとは予想される.しかし,なるほど Stern の述べる通り,その高頻度の語義は保守的だとしても,その語に比喩的・派生的な語義が新たに付加されることが妨げられるわけではない.むしろ,多くの場合,基礎語は多義である.

Stern の言うように,形態についても意味についても,高頻度と保守性との相関関係は等しく認められるように思われる.しかし,1つ大きな違いがある.形態の変化を論じる場合には,新形が旧形に取って代わる過程,あるいは少なくとも両形が variants として並び立つ状況が前提とされる.一応のところ 各々の variant は明確に区別される.しかし,意味の変化を論じる場合には,新しい語義が古い語義を必ずしも置き換えるのではなく,その上に累積されてゆくことが多い.新旧 variants の置換や並立というよりは,それらが多義として積み重なっていく過程である.形態の保守性と意味の保守性は,この違いを意識しながら理解しておく必要があるだろう.関連して,「#1692. 意味と形態の関係」 ([2013-12-14-1]) の第3引用を参照されたい.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

2014-06-13 Fri

■ #1873. Stern による意味変化の7分類 [semantics][semantic_change][causation]

「#1756. 意味変化の法則,らしきもの?」 ([2014-02-16-1]),「#1863. Stern による語の意味を決定づける3要素」 ([2014-06-03-1]),「#1862. Stern による言語の4つの機能」 ([2014-06-02-1]) で,意味と意味変化について考察した Stern の見解を紹介してきた.Stern (165--76) は意味変化の分類をも手がけ,7種類の分類を提案した.

A. External Causes Class I. Substitution.

B. Linguistic Causes

I. Shift of Verbal Relation

a. Class II. Analogy.

b. Class III. Shortening.

II. Shift of Referential Relation

a. Class IV. Nomination.

b. Class V. (Regular) Transfer.

III. Shift of Subjective Relation

a. Class VI. Permutation.

b. Class VII. Adequation.

Class I (Substitution) は,外部的,非言語的な要因による意味変化である.しばしば技術や文化の発展が関わっており,例えば ship や to travel は,近代的な乗り物が発明される前と後とでは,指示対象 (referent) が異なっている.意味変化そのものとみなすよりは,指示対象の変化に伴う意味の変更といったほうが適切かもしれない.

Class II (Analogy) は,例えば副詞 fast が「しっかりと」から「速く」へとたどった意味変化が,類推により対応する形容詞 fast へも影響し,形容詞 fast も「速い」の語義を獲得したという事例が挙げられる.意図的,非意図的の両方があり得る.話者主体.

Class III (Shortening) は,private soldier の省略形として private が用いれるようなケースで,結果として private の意味や機能が変化したことになる.意図的,非意図的の両方があり得る.話者主体.

Class IV (Nomination) は,いわゆる暗喩,換喩,提喩などを含む転義だが,とりわけ詩人などが意図的(ときに恣意的)に行う臨時的な転義を指す.話者主体.

Class V ((Regular) Transfer) は,意図的な転義を表わす Nomination に対して,非意図的な転義を指す.しかし,意図の有無が判然としないケースもある.話者主体.

Class VI (Permutation) は,count one's beads という「句」において,元来 beads は祈りを意味したが,祈りの回数を数えるのにロザリオの数珠玉をもってしたことから,beads が数珠玉そのものを意味するようになった.count one's beads は,両義に解釈できるという点で曖昧ではあるが,祈りながら数珠玉を数えている状況全体を指示対象としているという特徴がある.非意図的.聞き手も多く関与する.

Class VII (Adequation) は,元来動物の角を表わす horn という「語」が,(材質を問わない)角笛を意味するようになった例が挙げられる.指示対象自体は変化していないので Substitution ではなく,指示対象の使用目的に関する話者の理解が変化した点が特徴的である.非意図的.聞き手も多く関与する.

Stern の7分類は,(1) 言語外的か内的か,(2) 言語手段,指示対象,主観のいずれに関わるか,(3) 意図的か非意図的か,(4) 主たる参与者か話者のみか聞き手も含むか,といった複数の基準を重ね合わせたものである.1つのモデルとしてとらえておきたい.

関連して,「#473. 意味変化の典型的なパターン」 ([2010-08-13-1]) や「#1109. 意味変化の原因の分類」 ([2012-05-10-1]) も参照.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

2014-06-03 Tue

■ #1863. Stern による語の意味を決定づける3要素 [semantics]

Stern は語の意味を決定づける要素として3つを挙げている.1つ目は "the objective reference", 2つ目は "the subjective apprehension", 3つ目は "the traditional range" である.それぞれ,指示対象そのものの特性,話し手や聞き手がそれをどのように捉えているか,社会慣習としての有効範囲を表わす.別の観点からいえば,昨日の記事「#1862. Stern による言語の4つの機能」 ([2014-06-02-1]) で挙げた Stern の言語の4機能のうちの最初の3つ,symbolic, expressive, communicative の機能にそれぞれ対応するといえる.Stern (43--44) に直接説明してもらおう.

We have found, in the first place, that the objective reference is an indispensable element in any meaning, and that the qualitative characteristics of meaning are conditioned by the actual characteristics of the referent which the word is employed to denote. This factor conditions the symbolic function of the word.

We have found, secondly, that the meaning of a word is determined also by the subject's apprehension of the referent that the word is employed to denote, that is to say, the subject's thoughts and feelings with regard to the referent. This factor conditions the expressive function of the word.

We have found, thirdly, that the traditional range of a word serves to discriminate its meaning from concomitant elements of mental content, or mental context. The meaning of a word in speech normally lies within its range. This factor conditions the communicative function of the word.

語の意味を決定づける3要素というこの提案が魅力的なのは,第1,第2の要素がすぐれて心理学的なものであるのに対して,第3の要素は,伝統や社会慣習など,すぐれて社会言語学的な概念に関係するものである点だ.意味論が,部分的ではあるが心理学から脱却し,自らの居場所を(社会)言語学のなかへ引き戻しているかのような感がある.

続けて Stern (45) は,上記の説を踏まえて,語の意味を次のように定義している.少なくとも作業仮説として評価できる定義である.

The meaning of a word --- in actual speech -- is identical with those elements of the user's (speaker's or hearer's) subjective apprehension of the referent denoted by the word, which he apprehends as expressed by it.

Stern の立場は,Ogden and Richards の立場とそれほど隔たっていないように思われる.後者については,「#1769. Ogden and Richards の semiotic triangle」 ([2014-03-01-1]),「#1777. Ogden and Richards による The Canons of Symbolism」 ([2014-03-09-1]),「#1782. 意味の意味」 ([2014-03-14-1]) を参照.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow