2018-08-10 Fri

■ #3392. 同義語と類義語 [semantics][lexicology][thesaurus]

標題の2つの用語は言語学ではいずれもよく使われるが,はたして同じものなのか,それとも異なるのか.語の意味にまつわる話題であり,案外難しい問題である.実用上は,厳密に定義を与えないままに,両用語を「適当に,常識的に」使用し(分け)ているものと思われる.実際,英語の synonym は「同義語」にも「類義語」にも相当するのだ.

一般的には,語義が完全に一致する「完全同義語」 (absolute synonym) のペアは(ほとんど)ないと言われる (cf. 「#1498. taboo が言語学的な話題となる理由 (3)」 ([2013-06-03-1])) .ということは,synonym という用語が有意味となるためには,「完全同義語」ではなく「不完全同義語」を,すなわち「類義語」ほどを指していることが望ましい.一方,英語には near-synonym あるいはより専門的に plesionym (< Gr. plēsios (近接した) + onoma (名前)) という用語もある.ここから,synonym, near-synonym, plesionym という用語は,それこそ互いに synonymous な関係にあると解釈できそうである.語義の似ている度合いというのは数値化できるわけでもなく,当然ながら微妙な問題になることはやむを得ない.

Cruse (176--77) の意味論の用語辞典の説明を覗いてみよう.

synonymy, synonyms A word is said to be a synonym of another word in the same language if one or more of its senses bears a sufficiently close similarity to one or more of the senses of the other word. It should be noted that complete identity of meaning (absolute synonymy) is very rarely, if ever, encountered. Words would be absolute synonyms if there were no contexts in which substituting one for the other had any semantic effect. However, given that a basic function of words is to be semantically distinctive, it is not surprising that such identical pairs are rare. That being so, the problem of characterising synonymy is one of specifying what kind and degree of semantic difference is permitted. One possibility is to define synonymy as 'propositional synonymy': two words A and B are synonyms if substituting either one for the other in an utterance has no effect on the propositional meaning (i.e. truth conditions) of the utterance. This is the case with, for instance, begin: commence and false: untrue (on the relevant readings):

The concert began/commenced with Beethoven's Egmont Overture.

What he told me was false/untrue.

By this definition, synonyms will typically differ in respect of non-propositional aspects of meaning, such as expressive meaning and evoked meaning. Thus, begin and commence differ in register; the difference between false and untrue (indicating lack of veracity) is rather subtle, but the former is more condemnatory, perhaps because of a stronger presumption of deliberateness. However, while this is a convenient and easily applied way of defining synonymy, it does not capture the way the notion is used by, for instance, lexicographers, in the compilation of dictionaries of synonyms or in the assembly of groups of words for information on 'synonym discrimination'. Certainly, some of the words in such lists are propositional synonyms, but others are not, and for these we need some such notion as 'near-synonymy' ('plesionymy'). This is not easy to define, but roughly speaking, near-synonyms must share the same core meaning and must not have the primary function of contrasting with one another in their most typical contexts. (For instance, collie and spaniel share much of their meaning, but they contrast in their most typical contexts.) Examples of near-synonyms are: murder: execute: assassinate; withhold: detain; joyful: cheerful; heighten: enhance; injure: damage; idle: inert: passive.

synonyms を分析するにあたって,命題的意味 (propositional meaning) と非命題的意味 (non-propositional meaning) を区別するという方法は確かにわかりやすい.これは概念的意味 (conceptual meaning) と非概念的意味 (non-conceptual meaning) の区別にも近いだろう(「#1931. 非概念的意味」 ([2014-08-10-1]) を参照).命題的意味や概念的意味はイコールだが,非命題的意味や非概念的意味が何かしら異なっている場合に,その2語を synonyms と呼ぼう,というわけだ.

しかし,類義語辞典などに挙げられている類義語リストを構成する各単語は,たいていさらに緩い意味で「似ている」単語群にすぎない.最も中心的な意味のみを共有しており,かつ互いに異なる周辺的な意味はあくまで2次的なものとして,当面はうっちゃっておけるほどの関係であれば (near-)synonyms と呼べるということになろうか.ややこしい問題ではある.

・ Cruse, Alan. A Glossary of Semantics and Pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2006.

2018-03-19 Mon

■ #3248. 日本十進分類法 (NDC) 10版 [taxonomy][italic][thesaurus][semantics][htoed]

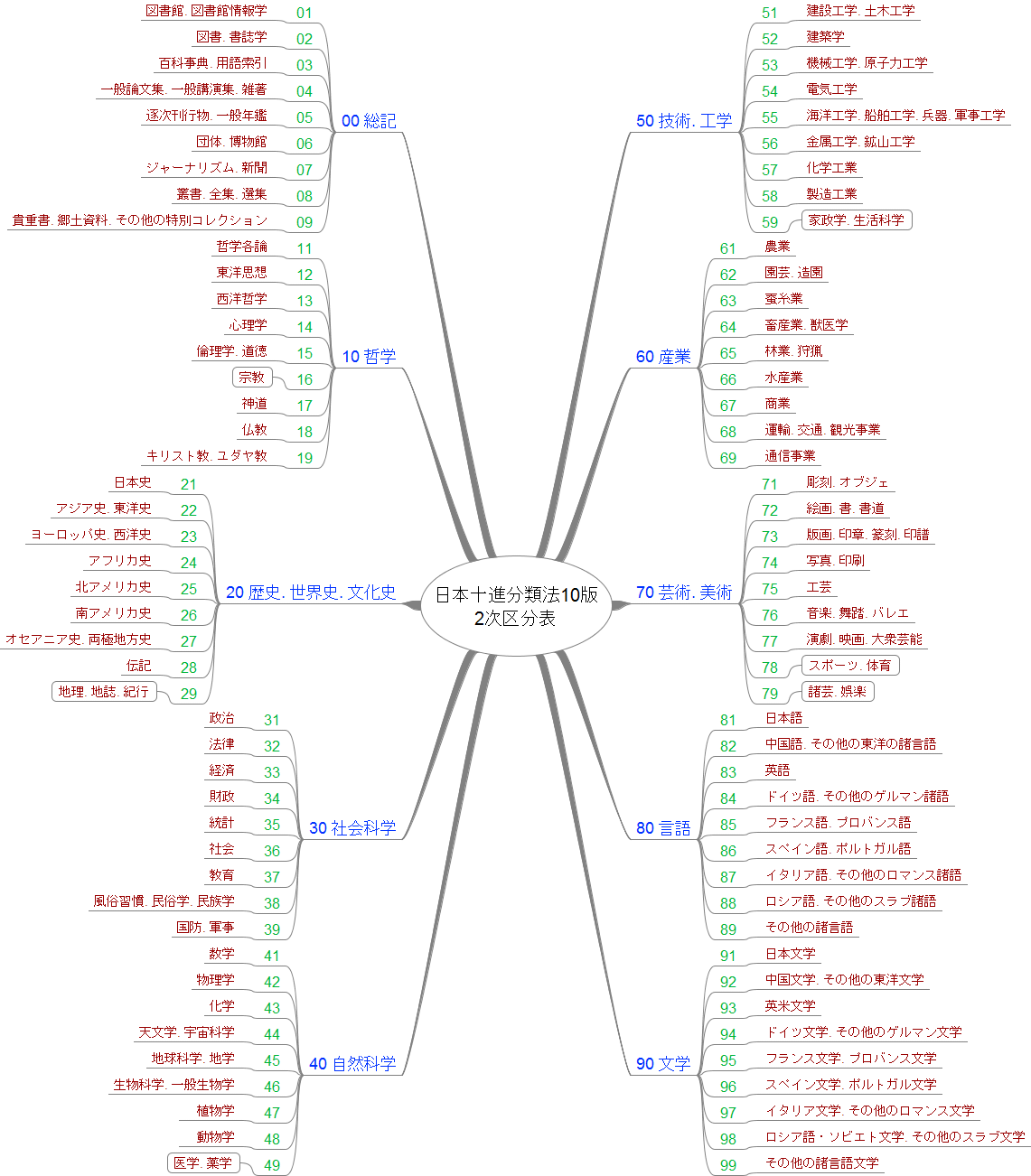

国立国会図書館では,平成29年4月より日本十進分類法 (NDC) の新訂10版が適用されている(こちらの案内を参照).10版の分類基準(2017年1月版)はこちら (PDF). *

9版から10版への内容的な変更はほとんどなく,用語の整備が主である.10版の綱目表(第2次区分表)に基づき,以下のマインドマップを作ってみた(PDF版やSVG版もどうぞ).

私の関心は特に「80 言語」あたりにあるが,9版から少し変わったのは,「84 ドイツ語」だったものが「84 ドイツ語.その他のゲルマン諸語」となったところである.同様に,「85 フランス語」「86 スペイン語」「87 イタリア語」もそれぞれ「85 フランス語.プロバンス語」「86 スペイン語.ポルトガル語」「87 イタリア語.その他のロマンス諸語」と名目上拡充された.「90 文学」の対応する部分にも同様の拡充が施されている.もちろん,このような拡充や細分化は始めればキリがないし,どこまで表記するかは,図書分類上の現実的な問題ともおおいに絡んで決定的な対処法はないだろう.

日本十進分類法は図書に関する分類法 (taxonomy) の1つだが,いわば百科事典的な分類法ともいえる.分類法といえば,意味論や類義語辞典 (thesaurus) 編纂においても意味分類は最も難しい問題だが,これらの諸分野は森羅万象の整理という共通の課題を抱えているとわかる.

英語史との関係でいえば,本格的な歴史的類義語辞典 HTOED の分類表を,「#3159. HTOED」 ([2017-12-20-1]) 経由で参照されたい.

2018-02-20 Tue

■ #3221. 意味変化の不可避性 [semantic_change][semantics][esperanto][artificial_language][onomasiology]

Algeo and Pyles は,語の意味の変化を論じた章の最後で,意味変化の不可避性を再確認している.そこで印象的なのは,Esperanto などの人工言語の話題を持ち出しながら,そのような言語的理想郷と意味変化の不可避性が相容れないことを熱く語っている点だ.少々長いが,"SEMANTIC CHANGE IS INEVITABLE" と題する問題の節を引用しよう (243--44) .

It is a great pity that language cannot be the exact, finely attuned instrument that deep thinkers wish it to be. But the facts are, as we have seen, that the meaning of practically any word is susceptible to change of one sort or another, and some words have so many individual meanings that we cannot really hope to be absolutely certain of the sum of these meanings. But it is probably quite safe to predict that the members of the human race, homines sapientes more or less, will go on making absurd noises with their mouths at one another in what idealists among them will go on considering a deplorably sloppy and inadequate manner, and yet manage to understand one another well enough for their own purposes.

The idealists may, if they wish, settle upon Esperanto, Ido, Ro, Volapük, or any other of the excellent scientific languages that have been laboriously constructed. The game of construction such languages is still going on. Some naively suppose that, should one of these ever become generally used, there would be an end to misunderstanding, followed by an age of universal brotherhood---the assumption being that we always agree with and love those whom we understand, though the fact is that we frequently disagree violently with those whom we understand very well. (Cain doubtless understood Abel well enough.)

But be that as it may, it should be obvious, if such an artificial language were by some miracle ever to be accepted and generally used, it would be susceptible to precisely the kind of changes in meaning that have been our concern in this chapter as well as to such change in structure as have been our concern throughout---the kind of changes undergone by those natural languages that have evolved over the eons. And most of the manifold phenomena of life---hatred, disease, famine, birth, death, sex, war, atoms, isms, and people, to name only a few---would remain as messy and hence as unsatisfactory to those unwilling to accept them as they have always been, no matter what words we use in referring to them.

私の好きなタイプの文章である.なお,引用の最後で "no matter what words we use in referring to them" と述べているのは,onomasiological change/variation に関することだろう.Algeo and Pyles は,semasiological change と onomasiological change を合わせて,広く「意味変化」ととらえていることがわかる.

人工言語の抱える意味論上の問題点については,「#961. 人工言語の抱える問題」 ([2011-12-14-1]) の (4) を参照.関連して「#963. 英語史と人工言語」 ([2011-12-16-1]) もどうぞ.また,「#1955. 意味変化の一般的傾向と日常性」 ([2014-09-03-1]) もご覧ください.

・ Algeo, John, and Thomas Pyles. The Origins and Development of the English Language. 5th ed. Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

2017-12-20 Wed

■ #3159. HTOED [thesaurus][lexicography][dictionary][semantics][semantic_change][link][htoed][taxonomy]

Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary (HTOED) は,英語の類義語辞典 (thesaurus) として最大のものであるだけでなく,「歴史的な」類義語辞典として,諸言語を通じても唯一の本格的なレファレンスである.1965年に Michael Samuels によって編纂プロジェクトののろしが上げられ,初版が完成するまでに約45年の歳月を要した(メイキングの詳細は The Story of the Thesaurus を参照) .

HTOED は,現在3つのバージョンで参照することができる.

(1) 2009年に出版された紙媒体の2巻本.第1巻がシソーラス本体,第2巻が索引である.Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary (HTOED). Ed. Christian Kay, Jane Roberts, Michael Samuels and Irené Wotherspoon. 2 vols. Oxford: OUP, 2009.

(2) グラスゴー大学の提供する (1) のオンライン版.The Historical Thesaurus of English として提供されている.

(3) OED Online に組み込まれたオンライン版.

各バージョン間には注意すべき差異がある.もともと HTOED は OED の第2版に基づいて編纂されたものであるため,第3版に向けて改変された内容を部分的に含む OED Online と連携しているオンライン版との間で,年代や意味範疇などについて違いがみられることがある.また,OED Online 版は,OED の方針に従って1150年以降に伝わっていない古英語単語がすべて省かれているので,古英語単語について中心的に調べる場合には A Thesaurus of Old English (TOE). Ed. Jane Roberts and Christian Kay with Lynne Grundy. Amsterdam: Rodopi, [1995] 2000. Available online at http://oldenglishthesaurus.arts.gla.ac.uk/ . の成果を収録した (1) か (2) の版を利用すべきである.

HTOED で採用されている意味範疇は,235,249項目にまで細分化されており,そこに793,733語が含まれている.分類の詳細は Classification のページを参照.第3階層までの分類表はこちら (PDF) からも参照できる. *

2017-08-12 Sat

■ #3029. 統語論の3つの次元 [syntax][semantics][word_order][generative_grammar][semantic_role]

言語学において統語論 (syntax) とは何か,何を扱う分野なのかという問いに対する答えは,どのような言語理論を念頭においているかによって異なってくる.伝統的な統語観に則って大雑把に言ってしまえば,統語論とは文の内部における語と語の関係の問題を扱う分野であり,典型的には語順の規則を記述したり,句構造を明らかにしたりすることを目標とする.

もう少し抽象的に統語論の課題を提示するのであれば,Los の "Three dimensions of syntax" がそれを上手く要約している.これも1つの統語観にすぎないといえばそうなのだが,読んでなるほどと思ったので記しておきたい (Los 8) .

1. How the information about the relationships between the verb and its semantic roles (AGENT, PATIENT, etc.) is expressed. This is essentially a choice between expressing relational information by endings (inflection), i.e. in the morphology, or by free words, like pronouns and auxiliaries, in the syntax.

2. The expression of the semantic roles themselves (NPs, clauses?), and the syntactic operations languages have at their disposal for giving some roles higher profiles than others (e.g. passivisation).

3. Word order.

Dimension 1 は,動詞を中心として割り振られる意味役割が,屈折などの形態的手段で表わされるのか,語の配置による統語的手段で表わされるのかという問題に関係する.後者の手段が用いられていれば,すなわちそれは統語論上の問題となる.

Dimension 2 は,割り振られた意味役割がいかなる表現によって実現されるのか,そこに関与する生成(や変形)といった操作に焦点を当てる.

Dimension 3 は,結果として実現される語と語の配置に関する問題である.

これら3つの次元は,最も抽象的で深層的な Dimension 1 から,最も具体的で表層的な Dimension 3 という順序で並べられている.生成文法の統語観に基づいたものであるが,よく要約された統語観である.

・ Los, Bettelou. A Historical Syntax of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015.

2017-02-23 Thu

■ #2859. "quolia role" [generative_lexicon][semantics]

語彙意味論のアプローチの1つに,Pustejovsky の生成語彙論 (Generative Lexicon) がある.この理論では,語の意味を分析するのに "quolia role" という考え方が導入される.Cruse (149--50) の用語解説に基づいて要約すると,以下の通りである.

語の概念の特性には "quolia roles" と呼ばれるいくつかのタイプが区別され,文脈によって活性化されるタイプが異なる,という前提に立つ.Pustejovsky によれば,名詞で考えると4つの quolia roles が区別されるという."formal", "constitutive", "telic", "agentive" である(これは,アリストテレスの4原因説を思い起こさせる).

formal: This includes information about an item's position in a taxonomy, what it is a type of, and what sub-types it includes.

constitutive: This includes information about an item's part-whole structure, its physical attributes like size, weight, and what it is made of, and sensory attributes like colour and smell.

telic: This includes information about how an item characteristically interacts with other entities, whether as agent or instrument, in purposeful activities.

agentive: This includes information about an item's 'life-history', how it came into being, and how it will end its existence.

"formal" は語彙・概念上のタイプ,"constitutive" は物理的・認知的なタイプ,"telic" は目的・存在理由に関わるタイプ,"agentive" は出自・来歴に関わるタイプと概略的に示されるだろうか.

Pustejovsky によると,名詞の意味は,これら各々の quolia role に対して詳細が与えられることによって定義づけられる.このように語の意味が独立した quolia roles から構成されると考えることにより,両義性の問題がきれいに説明されるというのが,この理論のセールスポイントだ.

例えば,Pete finished the book yesterday. という文は,本を「読み終えた」のか「書き終えた」のかという2つの解釈が可能である.この両義性は,名詞 book を構成するどの quolia role が活性化されるかに基づくものとして説明される.「読み終えた」という解釈においては,名詞 book の telic role,すなわち「人に読まれるものとしての本」という目的・存在理由に関わる役割が活性化されるが,「書き終えた」という解釈においては,agentive role,すなわち「人に書かれたことによって存在している本」という出自・来歴に関わる特性が活性化されると考えることができる.

・ Cruse, Alan. A Glossary of Semantics and Pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2006.

2017-01-24 Tue

■ #2829. carnage (2) [metonymy][semantics]

昨日の話題の続編.トランプ大統領が carnage という強烈な言葉を使ったことについて,やはりメディアは湧いているようである.

20日の就任演説について,22日の朝日新聞朝刊で,原文と訳と解説が付されていた.問題の "This American carnage stops right here and stops right now." のくだりの解説に,こうあった.

「carnage」は「殺戮の後の惨状」といった意味で,「死屍累々」に近い.線状などの表現に使われる極めて強い言葉.トランプ氏は直前に都市部の貧困や,犯罪・麻薬の蔓延に触れ,「悲惨な状況にある米国」を描いた.今回の演説を象徴する言葉として,米メディアも注目している.

この「死屍累々」という訳語と解釈は,優れていると思う.英和辞典にある並一通りの「殺戮」という訳語ではなく「死屍累々」に近いと解釈したセンスが素晴らしい.

昨日の記事で引いた OED での語義 3a とは別の語義 2a に,次のような定義がある."Carcases collectively: a heap of dead bodies, esp. of men slain in battle. ? Obs.".「殺戮」というよりは,その結果としての「死屍累々」である.同じように,Johnson の辞書でもこの語義は "Heaps of flesh" として定義されている.carnage が,昨日の記事で指摘したようにラテン語で「肉」を意味する carn-, carō からの派生語であることを考えれば,直接的な意味発達としては,行為としての「殺戮」ではなく,「死体(の集合)」を指すとするのが妥当である.英語での初出年代こそ,「殺戮」の語義では1600年,「死体(の集合)」の語義では1667年 ("Milton Paradise Lost x. 268 Such a sent I [sc. Death] draw Of carnage, prey innumerable.") と,前者のほうが早いが,意味発達の自然の順序を考えると,因果関係を「果」→「因」とたどったメトニミー (metonymy) として「死体(の集合)」→「殺戮」のように変化したのではないかと想像される.喩えていうならば,トランプ大統領の carnage は,「殺す」という動詞が現在完了として用いられたかのような「完了・結果」の意味,すなわち「殺戮後の状態」=「死屍累々」を意味するものと捉えるのが適切となる.少なくとも,トランプ大統領(あるいは,その意を汲んだとされる31歳の若きスピーチライター Stephen Miller)は,過去の「殺戮」だけでなく,その結果としての「死屍累々」の現状を指示し,強調したかったはずである.

なお,「戮」という漢字についていえば,これは「ころす.ばらばらに切ってころす.敵を残酷なやり方でころす.また,罪人を残酷なやり方で死刑にする.」を意味する.一方,この漢字は,同じ「リク」という読みの「勠」に当てて「力をあわせる」の意味ももっており,「一致団結」と同義の「戮力協心」なる四字熟語もある.こちらの「戮」であればよいのだが,と淡い期待を抱く.

2017-01-18 Wed

■ #2823. homonymy と polysemy の境 (2) [semantics][homonymy][polysemy]

標題について「#286. homonymy, homophony, homography, polysemy」 ([2010-02-07-1]),「#815. polysemic clash?」 ([2011-07-21-1]),「#1801. homonymy と polysemy の境」 ([2014-04-02-1]),「#2174. 民間語源と意味変化」 ([2015-04-10-1]) などで扱ってきた.今回はもう2つの例を挙げ,同音異義 (homonymy) と多義 (polysemy) の境界の曖昧性について改めて考えてみたい.

意味論の概説書を著わした Saeed (65) が,英語から sole と gay の語を挙げている.sole には,名詞として "bottom of the foot" (足の裏)と "flatfish" (カレイの仲間)の2つの語義がある.両語義は多くの母語話者にとって互いに関係のないものとして理解されており,したがって同音異義語と認識されている.しかし,歴史的にはラテン語 solea "sandal" がフランス語経由で英語に入ったものであり,同根である.確かに,言われてみれば,ともに平べったい「サンダル」である.辞書での扱いもまちまちであり,2つの見出し語を立てているものもあれば,1つの見出し語のもとに2つの語義を分けているものもある.とすると,公正な立場を取るのであれば,歯切れは悪いが,両者の関係は homonymy でもあり polysemy でもあると結論せざるを得ない.

もう1つの例は,形容詞 gay である.この語には "homosexual" (同性愛の)と "lively, light-hearted, bright" (陽気な)という,2つの主たる意味がある.特に若い世代にとって,両語義の関連は,あったとしても薄いものに感じられるようで,その点では homonymy の関係にあると把握されているのではないか.しかし,なかには両語義は相互に関係するととらえている人もいるかもしれないし,実際,通時的には「陽気な」から「同性愛の」への意味変化が生じたものとされている.ここでも,ある人にとっては homonymy,別の人にとっては polysemy という状況が見られる.ある見方をすれば homonymy,別の見方をすれば polysemy と言い換えてもよい.

客観的な意味論の観点から,いずれの関係かを決めることは極めて難しい.homonymy と polysemy の境について,言語学的に理論化するのが困難な理由が分かるだろう.

gay の用法については,American Heritage Dictionary の Usage Note より gay も参照.

・ Saeed, John I. Semantics. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

2017-01-06 Fri

■ #2811. 部分語と全体語 [hyponymy][meronymy][lexicology][semantics][semantic_field][terminology]

「#1962. 概念階層」 ([2014-09-10-1]) や「#1961. 基本レベル範疇」 ([2014-09-09-1]) でみた概念階層 (conceptual hierarchy) あるいは包摂関係 (hyponymy) においては,例えば「家具」という上位語 (hypernym) の配下に「机」という下位語 (hyponym) があり,さらにその「机」が上位語となって,その下に「勉強机」や「作業机」という下位語が位置づけられる.ここでは,包摂という関係に基づいて,全体が階層構造をなしているのが特徴的である.

このような hyponymy と類似しているが区別すべき語彙的関係として,meronymy (部分と全体の関係)と呼ばれるものがある.例えば,「車輪」と「自転車」は部分と全体の関係にあり,「車輪」は「自転車」の meronym (部分語),「自転車」は「車輪」の holonym (全体語)と称される.meronymy においても hyponymy の場合と同様に,その関係は相対的なものであり,例えば「車輪」は「自転車」にとっては meronym だが,車輪を構成する「輻(スポーク)」にとっては holonym である.Cruse (105--06) からの meronymy の説明を示そう.

meronymy This is the 'part-whole' relation, exemplified by finger: hand, nose: face, spoke: wheel, blade: knife, harddisk: computer, page: book, and so on. The word referring to the part is called the 'meronym' and the word referring to the whole is called the 'holonym'. The names of sister parts of the same whole is called 'co-meronyms'. Notice that this is a relational notion: a word may be a meronym in relation to a second word, but a holonym in relation to a third. Thus finger is a meronym of hand, but a holonym of knuckle and fingernail. (Meronymy must not be confused with by hyponymy, although some of their properties are similar: for instance, both involve a type of 'inclusion', co-meronyms and co-taxonyms have a mutually exclusive relation, and both are important in lexical hierarchies. However, they are distinct: a dog is a kind of animal, but not a part of an animal; a finger is a part of a hand, but not a kind of hand.

meronymy と hyponymy は,いずれも「包摂」と「階層構造」を示す点で共通しているが,上の説明の最後にあるように,前者は part,後者は kind に対応するものであるという差異が確認される.また,meronymy では,部分と全体が互いにどのくらい必須であるかについて,hyponymy の場合よりも基準が明確でないことが多い.「顔」と「目」の関係はほぼ必須と考えられるが,「シャツ」と「襟」,「家」と「地下室」はどうだろうか.

さらに,hyponymy と meronymy は移行性 (transitivity) の点でも異なる振る舞いを示す.hyponymy では移行性が確保されているが,meronymy では必ずしもそうではない.例えば,「手」と「指」と「爪」は互いに meronymy の関係にあり,「手には指がある」と言えるだけでなく,「手には爪がある」とも言えるので,この関係は transitive とみなせる.しかし,「部屋」と「窓」と「窓ガラス」は互いに meronymy の関係にあるが,「部屋に窓がある」とは言えても「部屋に窓ガラスがある」とは言えないので,transitive ではない.

・ Cruse, Alan. A Glossary of Semantics and Pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2006.

2017-01-03 Tue

■ #2808. Jackendoff の概念意味論 [semantics][componential_analysis][noun][countability]

Ray Jackendoff の提唱している概念意味論 (conceptual semantics) においては,意味とは人間が頭のなかでコード化した情報構造である.以下の原理は "the Mentalist Postulate" と呼ばれている.

Meaning in natural language is an information structure that is mentally encoded by human beings. (qtd. in Saeed 278)

Jackendoff は,文の意味は構成要素たる各語の意味からなると考えているため,概念意味論では語の意味に特別の注意が払われることになる.名詞の意味の分析を通じて,概念意味論の一端を覗いてみよう.以下,Saeed (283--84) を参照する.

Jackendoff は,名詞の意味特徴として [±BOUNDED] と [±INTERNAL STRUCTURE] を提案している.[±BOUNDED] は,典型的には可算名詞 (count noun) と質量名詞 (mass noun) を区別するのに用いられる.可算名詞は明確な境界をもつ単位を指示する.例えば,a car や a banana の指示対象を物理的に切断したとき,切断された各々のモノはもはや a car や a banana とは呼べない.それに対して,water や oxygen のような質量名詞は,複数の部分に分割したとしても,各々の部分は water や oxygen と呼び続けることができる.したがって,可算名詞は [+b] として,質量名詞は [-b] として記述することができる.

次に [±INTERNAL STRUCTURE] について見てみよう.可算名詞の複数,例えば cars や bananas は,内部に構造があるとみなし,[+i] と表わす.対して,water や oxygen のような質量名詞は内部構造なしとみなし,[-i] となる.

2つの意味特徴 [±BOUNDED], [±INTERNAL STRUCTURE] を掛け合わせると,4通りの組み合わせができるだろう.そして,この4通りの各々に相当する名詞が存在することが期待される.実際,英語にはそれがある.これを図示してみよう.

[ Material Entity ]

│

┌──────────┬────┴────┬─────────┐

│ │ │ │

individuals groups substances aggregates

(count nouns) (collective nouns) (mass nouns) (plural nouns)

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ │

[+b, -i] [+b, +i] [-b, -i] [-b, +i]

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ │

a banana, a government, water, bananas,

a car a committee oxygen cars

可算名詞が [+b, -i],質量名詞が [-b, -i] であることは上の説明から了解されると思われるが,他の2つについては補足説明が必要だろう.a government や a committee のような集合名詞 (collective noun) は,それ自体が1つの単位であり,切断するとアイデンティティを失ってしまうが,複数の構成員からなっているという意味において,内部構造はあると考えられる.したがって,[+b, +i] と記述できるだろう.また,bananas や cars のような可算名詞複数 (plural noun) については,具体的に何個と決まっているのなら別だが,ただ複数形で表わされると,茫漠と「多くのバナナ,車」を意味することになり,境界はぼやけている.しかし,内部構造はあると考えられるので,[-b, +i] と表現されることになる.

この分析は,4種類の名詞を2つの意味特徴でスマートに仕分けできるとともに,各々が主語となるときの動詞の一致など,統語的振る舞いにも関与してくるという点で,有用な分析となっている.

・ Saeed, John I. Semantics. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

2016-12-21 Wed

■ #2795. 「意味=指示対象」説の問題点 [semantics][philosophy_of_language]

表現の意味は,それが指す何らかの対象,すなわち指示対象であるという説は,現代の意味論ではナイーブにすぎるとして受け入れられない.「エヴェレスト山」と「チョモランマ」を例に取ろう.両者は異なる表現形式である.2つは同一の山を指しているには違いないが,だからといって同じ意味をもっていると言い切ることができるだろうか.

例えば,「太郎はチョモランマがエヴェレスト山であることを知らない」という文と,「太郎はエヴェレスト山がエヴェレスト山であることを知らない」という文とは,異なる意味をもっているように感じられる.前者は,チョモランマがエヴェレスト山の別名であることを太郎が知らない場合などに用いられるのに対し,後者は,目の前に見えている山がエヴェレスト山であることに太郎が気づいていない場合などに用いられる.しかし,「エヴェレスト山」と「チョモランマ」が同一の山を指すという点で同一の意味であると考えてしまうと,上に述べた2つの文の意味が異なる理由が説明できなくなる.

この「意味=指示対象」という見解,より正確には「意味は指示対象によって尽くされる」という見解に疑問を投げかけたのが Gottlob Frege (1848--1925) である.服部 (16) より関連する箇所を引用しよう.

フレーゲのアイディアはこうである.語,たとえば「エヴェレスト山」という固有名はある事物,つまりエヴェレスト山そのものを指すが,それはその語の意味を尽くしてはいない.その語の意味には,その語が指すもの――彼はこれに「意味」 (Bedeutung) という名を与えた――とは別に,「意義」 (Sinn) というものがあり,語はその「意義」を通じて「意味」を指すとフレーゲは考えたのである.この場合,二つの表現が同じ「意味」(つまり指示対象)を異なる「意義」を通じて指すということも起こりうる.〔中略〕では,その「意義」とは何なのだろうか.フレーゲによれば,それは「意味」が与えられる様式にほかならない.この「「意味」が与えられる様式」というのがまた曲者で,いささか掴み所がなく,それを明らかにしなければならないのであるが,今はそれを措いておこう.

ここでいう語の「意義」 (Sinn) とは「指示の仕方」と理解しておいてよい.これを文に拡張すれば,文の「意義」とは「文の真理値が与えられる様式」となるだろう.しかし,残念なことにフレーゲは,「指示の仕方」や「文の真理値が与えられる様式」がいかなるものなのか,その核心について明らかにしていない.

いずれにせよ,「意味=指示対象」説が単純に受け入れられるものではないことが分かるだろう.この説の問題点については,「#1769. Ogden and Richards の semiotic triangle」 ([2014-03-01-1]),「#1770. semiotic triangle の底辺が直接につながっているとの誤解」 ([2014-03-02-1]) も参照.

・ 服部 裕幸 『言語哲学入門』 勁草書房,2003年.

2016-12-20 Tue

■ #2794. 「意味=定義」説の問題点 [semantics]

語の意味については,定義を与えればそれで済む,という立場がある.意味が分からなければ,辞書で定義を確認すればよい,というものだ.文の意味については,文を構成する各語の意味がしっかり定義されていさえすれば,その意味をつなぎ合わせたものが文の意味となるのであり,問題はない.この立場は "definitions theory" と言われ,言語学の領域から一歩出れば,非常に広く受け入れられている考え方といってよいだろう.しかし,そうは簡単にいかない,というのが意味論の立場である.Saeed (6--7) にしたがって,"definition theory" の3つの問題点を指摘しよう.

第1に,辞書を想像してみればわかるように,語の意味の定義は,通常,別の語を組み合わせた文で与えられており,それらの各語の意味の定義が分かっていなければ,判明しないことになる.そして,その各語の意味の定義もまた,別の語や文によって定義されるのだ.つまり,定義が言語でなされる以上,永遠に辞書の中でたらい回しにされ,どこまでも行っても終わりがない.ここには,定義の循環の問題 (circularity) が生じざるをえない.定義を与えるためだけに用いられるメタ言語 (metalanguage) を作り出せば,この問題は解決するかもしれないが,はたして客観的に受け入れられるメタ言語なるものはありうるのか.

第2に,与えられた定義が正確なものであるという保証を,いかにして得ることができるのか,という問題がある.意味が母語話者の頭のなかに格納されているものであることを前提とするならば,それは母語話者の知識の1つであるということになる.では,その言語的知識 (linguistic knowledge) は,他の種類の知識,百科辞典的知識 (encyclopaedic knowledge) とは同じものなのか,違うものなのか.例えば,ある人が鯨は魚だと信じており,別の人は鯨はほ乳類だと信じている場合,2人の用いる「鯨」という語の意味は同じものなのか,違うのか.もし違うとしても,両者は「私は鯨に呑み込まれる夢を見た」という文の意味をほぼ完全に共有し,理解できると思われるが,それはなぜなのか.「愛」や「民主主義」についてはどうか.人によってその意味が異なるということは,十分にありそうである.

第3に,ある発話の意味がコンテクスト (context) に依存するという紛れもない事実がある(コンテクストについては,昨日の記事「#2793. コンテクストの種類 (2)」 ([2016-12-19-1]) 及び「#2122. コンテクストの種類」 ([2015-02-17-1]) を参照).Marvellous weather you have here in Ireland. という文の意味は,晴れている日に発話されたのと,雨の日に発話されたのでは,おおいに意味が異なるだろう.意味があくまで定義であるとすれば,その定義はありとあらゆるコンテクストの可能性を加味した定義でなければならないことになるが,そのようなことは可能だろうか.

(1) "circularity", (2) "the question of whether linguistic knowledge is different from general knowledge", (3) "the problem of the contribution of context to meaning" の3つの点から,「意味=定義」とする単純な意味に関する説は受け入れられない.

意味とは何かという本質的な問題については,「#1782. 意味の意味」 ([2014-03-14-1]),「#1931. 非概念的意味」 ([2014-08-10-1]),「#1990. 様々な種類の意味」 ([2014-10-08-1]),「#2199. Bloomfield にとっての意味の意味」 ([2015-05-05-1]) などを参照.

・ Saeed, John I. Semantics. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

2016-11-03 Thu

■ #2747. Reichenbach の時制・相の理論 [tense][aspect][deixis][perfect][preterite][future][semantics]

言語における時制・相を理論化する有名な試みに,Reichenbach のものがある.3つの参照時点を用いることで,主たる時制・相を統一的に説明しようとするものだ.その3つの参照時点とは,以下の通り(Saeed (128) より引用).

S = the speech point, the time of utterance;

R = the reference point, the viewpoint or psychological vantage point adopted by the speaker;

E = event point, the described action's location in time.

この S, R, E の時間軸上の相対的な位置関係を,先行する場合には "<",同時の場合には "=",後続する場合には ">" の記号で表現することにする.例えば,過去の文 "I saw Helen", 過去完了の文 "I had seen Helen",未来の文 "I will see Helen" のそれぞれの時制は,以下のように表わすことができるだろう.

"I saw Helen" ───┴───────┴───>

(R = E < S) R, E S

"I had seen Helen" ───┴───┴───┴───>

(E < R < S) E R S

"I will see Helen" ───┴───────┴───>

(S < R = E) S R, E

この SRE の分析によると,英語の時制体系は以下の7つに区分される (Saeed 132) .

| Simple past | (R = E < S) | "I saw Helen" |

| Present perfect | (E < S = R) | "I have seen Helen" |

| Past perfect | (E < R < S) | "I had seen Helen" |

| Simple present | (S = R = E) | "I see Helen" |

| Simple future | (S < R = E) | "I will see Helen" |

| Proximate future | (S = R < E) | "I'm going to see Helen" |

| Future perfect | (S < E < R) | "I will have seen Helen" |

SRE の3時点の関係は様々だが,S = R となるのが現在完了,単純現在,近接未来の3つの場合のみであることは注目に値する.非英語母語話者には理解しにくい現在完了の「現在への関与」 (relevance to "now") という側面は,Reichenbach の理論では「S = R」として表現されるのである.

・ Reichenbach, Hans. Elements of Symbolic Logic. London: Macmillan, 1947.

・ Saeed, John I. Semantics. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

2016-10-08 Sat

■ #2721. 接頭辞 de- [affixation][prefix][word_formation][derivation][etymology][semantics][polysemy]

10月6日付の朝日新聞に,JICA がミャンマー農業支援のために「除湿機」 を購入すべきところ「加湿機」を購入してしまい,検査院に指摘されたという記事があった.英語表記で,加湿機は humidifier,除湿機は dehumidifier なので,de- の有無が明暗を分けたという事の次第だ.日本語でも,1漢字あるいは1モーラで大違いの状況である.同情の余地もないではないが,そこには260万円という金額が関わっている.

接頭辞 de- は,典型的に動詞の基体に付加して,その意味を反転させたり,除去の含意を加えたりする.もともとはラテン語で "off" ほどに相当する副詞・前置詞 de- に由来し,フランス語を経て英語に入ってきた語もあれば,直接ラテン語から入ってきた語,さらに英語内部で造語されたものも少なくない.起源は外来だが,次第に英語の接頭辞として成長してきたのである.de- の語義は,細分化すれば以下の通りになる (Web3 より).

1. 行為の反転 (ex. decentralize, decode; decalescence)

2. 除去 (ex. dehorn, delouse; dethrone)

3. 減少 (ex. derate)

4. 派生の起源(特に文法用語などに) (ex. decompound, deadjectival, deverbal)

5. 降車 (ex. debus, detrain)

6. 原子の欠如 (ex. dehydro-, deoxy-)

7. 中止 (ex. de-emanate)

ここには挙げられていないが,「#2638. 接頭辞 dis- 」 ([2016-07-17-1]) で触れたように,de- は dis- と混同され,意味的な影響を受けたとも言われている.また,その記事でも触れたが,基体がもともと否定的な意味を含んでいる場合には,de- のような否定的な接頭辞がつくと,その否定性が強調される効果を生むため,「強調」の用法ラベルがふさわしくなることもある.例えば,decline では,cline がもともと「曲がる,折れる」と下向きのややネガティヴな含意をもっているので,de- の用法は「減少」であるというよりは「強調」といえなくもない.denude や derelict の de- も基体の含意がガン愛ネガティヴなので,de- が結果として「強調」用法と解されている例だろう.

問題の dehumidifier の de- を「強調」用法としてかばうことはできそうにないが,接頭辞の多義性には注意しておきたい.

2016-10-05 Wed

■ #2718. 認知言語学の3つの前提 [linguistics][semantics][cognitive_linguistics][history_of_linguistics]

認知言語学 (cognitive_linguistics) は,主として1980年代より発達してきた言語構造と言語行動の研究法である.Cruse の用語集の cognitive linguistics の項によると,この研究法の背景には,いくつかの基本的な前提がある.

(1) 言語は意味を伝達する目的で発展してきたのであり,意味,統語,音韻の別にかかわらず,すべての言語構造はこの機能と関連しているはずである.

(2) 言語能力は,一般的な認知能力に埋め込まれており,それと分かつことはできない.したがって,言語に特化した脳の自律的部位なるものは存在しない.このことが意味論にとってもつ意義は,言語的意味と一般的知識のあいだに,規則的な区別を認めることができないということである.

(3) 意味は本来概念的なものであり,特定の方法で認知的・知覚的な原料を形成し,それに形態を付すことに関与する.

認知言語学者は,真理条件に基づく意味論の方法は意味を適切に説明することができないと主張する.認知言語学は,認知心理学と密接な関係をもっており,とりわけ概念の構造と性質に関する研究に依拠している.認知言語学の発展に特に影響力のある学者を2人挙げるとすれば,Lakoff と Langacker だろう.

認知言語学の前提については,「#1957. 伝統的意味論と認知意味論における概念」 ([2014-09-05-1]) も参照.

・ Cruse, Alan. A Glossary of Semantics and Pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2006.

2016-09-28 Wed

■ #2711. 文化と言語の関係に関するおもしろい例をいくつか [sapir-whorf_hypothesis][linguistic_relativism][bct][category][semantics]

日本語には「雨」の種類を細かく区分して指し示す語彙が豊富にあり,英語には「群れ」を表わす語がその群れているモノの種類に応じて使い分けられる(「#1894. 英語の様々な「群れ」,日本語の様々な「雨」」 ([2014-07-04-1]),「#1868. 英語の様々な「群れ」」 ([2014-06-08-1]) を参照).このような話しは,サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) に関する話題として,広く興味をもたれる.実際には,このような事例が,どの程度同仮説の主張する文化と言語の密接な関係を支持するものなのか,正確に判断することは難しい.このことは,「#364. The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax」 ([2010-04-26-1]),「#1337. 「一単語文化論に要注意」」 ([2012-12-24-1]) などの記事で注意喚起してきた.

それでも,この種の話題は聞けば聞くほどおもしろいというのも事実であり,いくつか良い例を集めておきたいと思っていた.Wardhaugh (234--35) に,古今東西の言語からの事例が列挙されていたので,以下に引用しておきたい.

If language A has a word for a particular concept, then that word makes it easier for speakers of language A to refer to that concept than speakers of language B who lack such a word and are forced to use a circumlocution. Moreover, it is actually easier for speakers of language A to perceive instances of the concept. If a language requires certain distinctions to be made because of its grammatical system, then the speakers of that language become conscious of the kinds of distinctions that must be referred to: for example, gender, time, number, and animacy. These kinds of distinctions may also have an effect on how speakers learn to deal with the world, i.e., they can have consequences for both cognitive and cultural development.

Data such as the following are sometimes cited in support of such claims. The Garo of Assam, India, have dozens of words for different types of baskets, rice, and ants. These are important items in their culture. However, they have no single-word equivalent to the English word ant. Ants are just too important to them to be referred to so casually. German has words like Gemütlichkeit, Weltanschauung, and Weihnachtsbaum; English has no exact equivalent of any one of them, Christmas tree being fairly close in the last case but still lacking the 'magical' German connotations. Both people and bulls have legs in English, but Spanish requires people to have piernas and bulls to have patas. Both people and horse eat in English but in German people essen and horses fressen. Bedouin Arabic has many words for different kinds of camels, just as the Trobriand Islanders of the Pacific have many words for different kinds of yams. Mithun . . . explains how in Yup'ik there is a rich vocabulary for kinds of seals. There are not only distinct words for different species of seals, such as maklak 'bearded seal,' but also terms for particular species at different times of life, such as amirkaq 'young bearded seal,' maklaaq 'bearded seal in its first year,' maklassuk 'bearded seal in its second year,' and qalriq 'large male bearded seal giving its mating call.' There are also terms for seals in different circumstances, such as ugtaq 'seal on an ice-floe' and puga 'surfaced seal.' The Navaho of the Southwest United States, the Shona of Zimbabwe, and the Hanunóo of the Philippines divide the color spectrum differently from each other in the distinctions they make, and English speakers divide it differently again. English has a general cover term animal for various kinds of creatures, but it lacks a term to cover both fruit and nuts; however, Chinese does have such a cover term. French conscience is both English conscience and consciousness. Both German and French have two pronouns corresponding to you, a singular and a plural. Japanese, on the other hand, has an extensive system of honorifics. The equivalent of English stone has a gender in French and German, and the various words must always be either singular or plural in French, German, and English. In Chinese, however, number is expressed only if it is somehow relevant. The Kwakiutl of British Columbia must also indicate whether the stone is visible or not to the speaker at the time of speaking, as well as its position relative to one or another of the speaker, the listener, or possible third party.

諸言語間で語の意味区分の精粗や方法が異なっている例から始まり,人称や数などの文法範疇 (category) の差異の例,そして敬語体系のような社会語用論的な項目に関する例まで挙げられている.サピア=ウォーフの仮説を再考する上での,話しの種になるだろう.

・ Wardhaugh, Ronald. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 6th ed. Malden: Blackwell, 2010.

2016-09-14 Wed

■ #2697. few と a few の意味の差 [semantics][antonymy][article][countability]

9月8日付けで掲示板に標題に関する質問が寄せられた.一般には,不定冠詞のない裸の few は可算名詞について「ほとんどない」と否定的な含意をもって用いられ,不定冠詞付の a few は「少しある」と肯定的な意味を有するとされる.この理解が誤りというわけではないが,日本語になおして理解するよりも,英英辞典における定義を参考にすると理解が深まるように思われる.例えば OALD8 によれば,few は "used with plural nouns and a plural verb to mean 'not many'" とあり, a few は "used with plural nouns and a plural verb to mean 'a small number', 'some'" とある.つまり,few は many の否定・対義としての位置づけ,a few は some と同義としての位置づけである.ここから few が否定的に傾き,a few は肯定的に傾くという傾向が発するのだろうと考えられる.

歴史を遡ってみよう.few という語は,古英語より fēawa, fēawe, fēa などの形で,原則として複数形の形容詞として(また不定代名詞的にも)普通に用いられていた.当時の意味はまさしく many (多い; OE maniġ)の対義語としての「少ない」であり,現代英語の不定冠詞なしの few と同等である.

一方,a few に相当する表現については,古英語では不定冠詞は未発達だったために,そもそも確立していなかった.つまり,現代のような few と a few の対立はまだ存在していなかったのである.中英語に入り,不定冠詞が徐々に発達してくると,ようやく "a small number of" ほどの意味で a few が現われてくる.OED での初例は1297年の "1297 R. Gloucester's Chron. (1724) 18 Þe kyng with a fewe men hym~self flew at þe laste." が挙げられている.

問題は,なぜこのような意味上の区別が生じたかということである.裸の few については,古英語より many の対義語として,つまり "not many" としての位置づけが,以降,現在まで連綿と受け継がれたと考えればよいだろう.一方,a few については,不定冠詞の本来的な「(肯定的)存在」の含意が few に付け加えられたと考えられるのではないか.「#86. one の発音」 ([2009-07-22-1]) でみたように,不定冠詞 a(n) の起源は数詞の ān (one) である.そして,この語に否定辞 ne を付加して否定語を作ったものが,nān (< ne + ān) であり,これが none さらには no へと発達する.つまり,不定冠詞 a(n) は,数詞としての1を積極的に示すというよりは,否定の no に対置されるという点で,肯定や存在の含意が強い.

以上をまとめると,few そのものは many の否定として位置づけられ,もとより否定的な含意をもっているが,a の付加された a few は不定冠詞のもつ肯定・存在の含意を帯びることになった,ということではないか.同じことは,不可算名詞の量を表わす little と a little についても言える.前者は much の否定として,後者はそれに a が付くことで肯定的な含意をもつことになったと考えられる.

参考までに OED の few, adj. の第1語義の定義を挙げておきたい.

1. Not many; amounting to a small number. Often preceded by but, †full, so, too, very, †well.

Without prefixed word, few usually implies antithesis with 'many', while in a few, some few the antithesis is with 'none at all'. Cf. 'few, or perhaps none', 'a few, or perhaps many'.

2016-09-06 Tue

■ #2689. Saeed の意味論概説書の目次 [toc][semantics]

先日の「#2683. Huang の語用論概説書の目次」 ([2016-08-31-1]) に引き続き,今回は,Saeed の意味論のテキストの目次を挙げる.定評のある意味論の概説書で,共時的意味論の広い分野を網羅しており,理論的な基礎を学ぶのに適している.ただし,通時的な意味論の話題はほとんど扱っていない.

Part I Preliminaries

1 Semantics in Linguistics

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Semantics and Semiotics

1.3 Three Challenges in Doing Semantics

1.4 Meeting the Challenges

1.5 Semantics in a Model of Grammar

1.6 Some Important Assumptions

1.7 Summary

2 Meaning, Thought and Reality

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Reference

2.3 Reference as a Theory of Meaning

2.4 Mental Representations

2.5 Words, Concepts and Thinking

2.6 Summary

Part II Semantic Description

3 Word Meaning

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Words and Grammatical Categories

3.3 Words and Lexical Items

3.4 Problems with Pinning Down Word Meaning

3.5 Lexical Relations

3.6 Derivational Relations

3.7 Lexical Universals

3.8 Summary

4 Sentence Relations and Truth

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Logic and Truth

4.3 Necessary Truth, A Priori Truth and Analyticity

4.4 Entailment

4.5 Presupposition

4.6 Summary

5 Sentence Semantics 1: Situations

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Classifying Situations

5.3 Modality and Evidentiality

5.4 Summary

6 Sentence Semantics 2: Participants

6.1 Introduction: Classifying Participants

6.2 Thematic Roles

6.3 Grammatical Relations and Thematic Roles

6.4 Verbs and Thematic Role Grids

6.5 Problems with Thematic Roles

6.6 The Motivation for Identifying Thematic Roles

6.7 Voice

6.8 Classifiers and Noun Classes

6.9 Summary

7 Context and Inference

7.1 Introduction

7.2 Deixis

7.3 Reference and Context

7.4 Knowledge as Context

7.5 Information Structure

7.6 Inference

7.7 Conversational Implicature

7.8 Summary

8 Functions of Language: Speech as Action

8.1 Introduction

8.2 Austin's Speech Act Theory

8.3 Categorizing Speech Acts

8.4 Indirect Speech Acts

8.5 Sentence Types

8.6 Summary

Part III Theoretical Approaches

9 Meaning Components

9.1 Introduction

9.2 Lexical Relations in CA

9.3 Katz's Semantic Theory

9.4 Grammatical Rules and Semantic Components

9.5 Components and Conflation Patterns

9.6 Jackendoff's Conceptual Structure

9.7 Pustejovsky's Generative Lexicon

9.8 Problems with Components of Meaning

9.9 Summary

10 Formal Semantics

10.1 Introduction

10.2 Model-Theoretical Semantics

10.3 Translating English into a Logical Metalanguage

10.4 The Semantics of the Logical Metalanguage

10.5 Checking the Truth-Value of Sentences

10.6 Word Meaning: Meaning Postulates

10.7 Natural Language Quantifiers and Higher Order Logic

10.8 Intensionality

10.9 Dynamic Approaches to Discourse

10.10 Summary

11 Cognitive Semantics

11.1 Introduction

11.2 Metaphor

11.3 Metonymy

11.4 Image Schemas

11.5 Polysemy

11.6 Mental Spaces

11.7 Langacker's Cognitive Grammar

11.8 Summary

・ Saeed, John I. Semantics. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

2016-09-01 Thu

■ #2684. 「嘘」のプロトタイプ意味論 [prototype][semantics]

プロトタイプ (prototype) に基づく意味論では,ある語の意味を,複数の意味特徴の有無を束ねた集合として定義する伝統的な意味論の発想から脱し,各意味特徴に程度の差を認め,意味の定義というよりは意味の典型を与えようと試みる.プロトタイプ理論は,色彩語をはじめ感覚的,物理的な意味をもつ語彙へ適用され,成果をあげてきたが,では心理的,社会的な要素をもつ語彙へも適用できるのだろうか.この問題意識から,Coleman and Kay は,英語の lie (嘘)にプロトタイプ意味論の分析を加えた.

Coleman and Kay (43) の調査の手順と議論の展開は単純かつ明解である.論文の結論部によくまとめられているので,それを引用する.

We have argued that many words, and the word lie in particular, have as their meanings not a list of necessary and sufficient conditions that a thing or event must satisfy to count as a member of the category denoted by the word, but rather a psychological object or process which we have called a PROTOTYPE. In some cases, a prototype can be represented by a list of conditions; but these are not necessary conditions, and the evaluative logic according to which these conditions are found to be satisfied, or not, is in general one of degree rather than of simple truth and falsity. . . .

In particular, we formulated (on the basis of the sort of introspection usual in semantic and syntactic research) a prototype for the word lie, consisting of three elements: falsity, intent to speak falsely, and intent to deceive. Stories were then constructed which described speech acts embodying each of the eight possible combinations of these three elements; these were presented to subjects, to be judged on the extent to which the relevant character in the story could be said to have lied. The pattern of responses confirmed the theory. The stories containing and lacking all three elements received by far the highest and lowest scores respectively. Further, in comparing each pair of stories in which the first contained all the prototype elements of the second plus at least one more, the majority of informants always gave the higher lie-score to the first. Of the nineteen comparisons of this type, each of which turned out as predicted, eighteen produced proportions significant at the .01 level. We then compared each pair of stories which differed in the presence of exactly two elements, to see if these comparisons yielded a consistent pattern with respect to the relative importance of the prototype elements. A consistent pattern was found: falsity of belief is the most important element of the prototype of lie, intended deception is the next most important element, and factual falsity is the least important.

鮮やかに結論が出た.lie が lie であるための最も重要なパラメータ(プロトタイプ要素)は「話者が発話内容を偽と信じている」ことであり,次に「話者が相手を欺こうとしている」ことであり,最後に「発話内容が実際に偽である」ことと続く.この順で点数が加算され,総合得点が高いものほど嘘らしい嘘であり,低いほど嘘っぽくないということになる.どこからが嘘であり,どこからが嘘でないのかの判断は個人によっても場合によっても揺れ動くが,プロトタイプ的な嘘が何であるかの認識と,そこからの逸脱の度合いに関しては,母語話者の間でおよそ感覚が一致するということが突き止められた.

プロトタイプ意味論のエッセンスの詰まった,かつ分かりやすい研究である.

・ Coleman, L. and P. Kay. "Prototype Semantics: The English Word lie." Language 22 (1980): 26--44.

2016-08-06 Sat

■ #2658. the big table と the table that is big の関係 [generative_grammar][syntax][adjective][semantics]

一昔前の変形文法などでは,形容詞が限定用法 (attributive use) として用いられている the big table という句は,叙述用法 (predicative use) として用いられている the table that is big という句から統語的に派生したものと考えられていた.後者の関係詞と連結詞 be を削除し,残った形容詞を名詞の前に移動するという規則だ.確かに多くの実例がそのように説明されるようにも思われるが,この統語的派生による説明は必ずしもうまくいかない.Bolinger が,その理由をいくつか挙げている.

1つ目に,限定用法としてしか用いられない形容詞が多数ある.例えば,the main reason とは言えても *The reason is main. とは言えない.fond, runaway, total ほか,同種の形容詞はたくさんある (see 「#643. 独立した音節として発音される -ed 語尾をもつ過去分詞形容詞」 ([2011-01-30-1]),「#712. 独立した音節として発音される -ed 語尾をもつ過去分詞形容詞 (2)」 ([2011-04-09-1]),「#1916. 限定用法と叙述用法で異なる形態をもつ形容詞」 ([2014-07-26-1])) .反対に,The man is asleep. に対して *the asleep man とは言えないように,叙述用法としてしか用いられない形容詞もある.先の派生関係を想定するならば,なぜ *The reason is main. が非文でありながら,the main reason は適格であり得るのかが説明されないし,もう1つの例については,なぜ The man is asleep. から *the asleep man への派生がうまくいかないのかを別途説明しなければならないだろう.

2つ目に,変形文法の長所は統語上の両義性を解消できる点にあるはずだが,先の派生関係を想定することで,むしろ両義性を作り出してしまっているということだ.The jewels are stolen. と the stolen jewels の例を挙げよう.The jewels are stolen. は,「その宝石は盗まれる」という行為の読みと「その宝石は盗品である」という性質の読みがあり,両義的である.しかし,そこから派生したと想定される the stolen jewels は性質の読みしかなく,両義的ではない.ところで,派生の途中段階にあると考えられる the jewels stolen は性質の読みはありえず,行為の読みとなり,両義的ではない.すると,派生の出発点と途中点と到達点の読みは,それぞれ「±性質」「?性質」「+性質」となり,この順番で派生したとなると,非論理的である.

Bolinger は上記2つ以外にも,派生を前提とする説を受け入れられない理由をほかにも挙げているが,これらの議論を通じて主張しているのは,限定用法が "reference modification" であり,叙述用法が "referent modification" であるということだ.The lawyer is criminal. 「その弁護士は犯罪者だ」において,形容詞 criminal は主語の指示対象である「その弁護士」を修飾している.しかし,the criminal lawyer 「刑事専門弁護士」において,criminal はその弁護士がどのような弁護士なのかという種別を示している.換言すれば,What kind of lawyer? の答えとしての criminal (lawyer) ということだ.

標題の2つの句に戻れば,the big table と the table that is big は,互いに統語操作の派生元と派生先という関係にあるというよりは,意味論的に異なる表現ととらえるべきである.前者はそのテーブルの種類を言い表そうとしているのに対して,後者はそのテーブルを描写している.

実際にはこれほど単純な議論ではないのだが,限定用法と叙述用法の差を考える上で重要なポイントである.

・ Bolinger, Dwight. "Adjectives in English: Attribution and Predication." Lingua 19 (1967): 1--34.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow