2020-07-04 Sat

■ #4086. 中英語研究における LAEME の役割 [laeme][lalme][me_dialect][dialectology][eme][manuscript][scribe]

昨日の記事「#4085. 中英語研究における LALME の役割」 ([2020-07-03-1]) に引き続き,LALME の姉妹版である初期中英語の方言地図 LAEME についても,研究史上の重要な位置づけを紹介しておこう.

LAEME は,時代としては LALME よりも古い時代を扱うが,プロジェクトとしてはそのの後継として開始されたために「後発の利点」を活かしうる立場にあった.とはいえ,編者の1人 Laing は,初期中英語の呈する特殊事情ゆえに深い悩みを抱えていた.後期中英語よりもテキストの量がずっと少なく,分布も偏っており,そもそも方言同定の最初の頼みとなる "anchor texts" が得にくい.とりわけ初期のテキストは,古英語の West-Saxon Schriftsprache に影響されたものが多く,そのスペリングを方言同定のために利用することはできない.しかし,Laing はテキスト産出に貢献した写字生を丁寧に選り分け,どの写字生の関わったどの部分のスペリングがその写字生の出所を示している可能性が高いか,等の知見を粘り強く蓄積していった.結果として,何とか少数の "anchor texts" を得ることに成功し,それをもとに LALME 以来洗練されてきた "fit-technique" を適用して,他のテキストを地図上にプロットしていった --- 今回はデジタルの力を借りて --- のである.

LAEME の新機軸は,LALME に付随する積年の問題だった質問項目 (questionnaire) の設定を放棄したことにあった.語彙・文法的タグを付しながらテキストを電子コーパス化し,即席の質問項目に対応できるように準備したのである.もっとも,対象としたテキストの全文に対して完全なるタグ付けを行なったわけではなく,時に写字(生)に関する込み入った事情ゆえに不完全にとどまるなど困難な経緯もあったようだ.プロジェクトの時間上の制約もあり,最終的には初期中英語の網羅的なコーパスとはならなかったものの,タグ付けされた65万語からなる,堂々たる研究ツールに仕上がった.とりわけ同時代の英語の正書法,音韻論,形態論のためには,なくてはならない必須ツールである.

研究ツールとしての LAEME の最大の長所は,テキストが徹頭徹尾 "diplomatic" であることだ.デジタルでありながら写本の綴字に限りなく忠実であろうとする,この原文に対する "diplomatic" な態度は,他ではほとんど例を見出すことができない.私自身も博士論文研究で大変お世話になった,ありがたいツールである.以上,Lowe (1126) に依拠して執筆した.

・ Lowe, Kathryn A. "Resources: Early Textual Resources." Chapter 71 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1119--31.

2020-07-03 Fri

■ #4085. 中英語研究における LALME の役割 [lalme][me_dialect][dialectology]

30年以上にわたり,LALME は中英語研究に甚大な役割を果たしてきた.そこから派生した他の研究プロジェクトも合わせて,この分野を決定づけ,牽引する役割を演じてきたといってよい.直接的には中英語方言学への貢献を目指したものだったが,結果としていえば LALME が対象とした中英語テキストの一覧は,最大にして包括的な中英語写本のリストともなったし,その効果は綴字や音声の研究を超えて語彙や文法の研究へも波及している.

LALME は,35年間の歳月をかけ,ICT技術に頼らずに千を超える写本の分析を施した成果物である,事実上 McIntosh と Samuels の2人の手になる快挙だ.しかし,このような制作背景を考えれば,少なからぬ不備が指摘されるのも無理からぬことである.

たとえば,南部(とりわけ Wash 南部)では,プロジェクトの時間上の都合で,精度がよくないとされる.調査が進むとともに,質問項目 (questionnaire) も変化や補足を加えられていったため,南部における掲載情報に不均衡がもたらされることになったという事情もある.しかし,2007--10年に公開された LALME をデジタル化した eLALME では,これらの問題への配慮もなされた(cf. 「#1622. eLALME」 ([2013-10-05-1])).

方法論上の問題も多々ある.先にも触れた質問項目については,Gilliéron の言葉で知られているように "L'établissement du questionnaire [...] pour être sensiblement meilleur, aurait dû être fait après l'enquête" という頭の痛い難問が常に待ち構えている.ほかには,テキストの種類によっては文証されない言語項があるという,やはり現実的には見過ごせない問題もある.たとえば,物語では動詞の現在形を多く得ることは難しいし,逆に使用説明書からは過去形を拾い出すことはできなさそうである.短いテキストや特別なジャンルのテキストからは,広範囲の語彙の使用は期待できないだろう.

そのような問題はあれ,やはり LALME の影響力は大きかったし,いまだに大きい.ある中英語テキストの方言を同定するのに,LALME の280のチェックリストはいまだに繰り返し使われているし,いまだ現役選手である.

本ブログでの LALME の使用例や関係する話題については,lalme の各記事を参照されたい.以上,Lowe (1127) に依拠して執筆した.

・ LALME = McIntosh, Angus, Michael Samuels, and Michael Benskin, with Margaret Laing and Keith Williamson. A Linguistic Atlas of Late Mediaeval English (LALME). Aberdeen: Aberdeen UP, 1986. Available online as eLALME at http://www.lel.ed.ac.uk/ihd/elalme/elalme_frames.html .

・ Gilliéron, Jules. Pathologie et thérapeutique verbales. Bern: Beerstecher, 1915.

・ Lowe, Kathryn A. "Resources: Early Textual Resources." Chapter 71 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1119--31.

2020-05-30 Sat

■ #4051. 中英語方言における bury の綴字の方言地図 --- LAEME より [laeme][me_dialect][dialectology][vowel][map][isogloss][eme][lalme]

中英語方言学でよく知られている方言間の母音変異の事例として,北部・東部方言の <i> = [i(ː)],中西部方言の <u> = [y(ː)],南東部方言の <e> = [e(ː)] というものがある.これは,古英語ウェストサクソン方言において典型的に <y> で綴られた母音(初期には [y(ː)],後期には [i(ː)] だったとされる)が,中英語の諸方言でどのような対応形を示しているかを図式的に整理したものである.

現代英語の単語でいえば busy, merry などが典型的に上記の方言分布と関連している. 関連する話題は以下の記事で扱ってきた.

・ 「#562. busy の綴字と発音」 ([2010-11-10-1])

・ 「#563. Chaucer の merry」 ([2010-11-11-1])

・ 「#570. bury の母音の方言分布」 ([2010-11-18-1])

・ 「#1341. 中英語方言を区分する8つの弁別的な形態」 ([2012-12-28-1])

・ 「#1434. left および hemlock は Kentish 方言形か」 ([2013-03-31-1])

・ 「#4048. much, shut, such, trust の母音と中英語方言学」 ([2020-05-27-1])

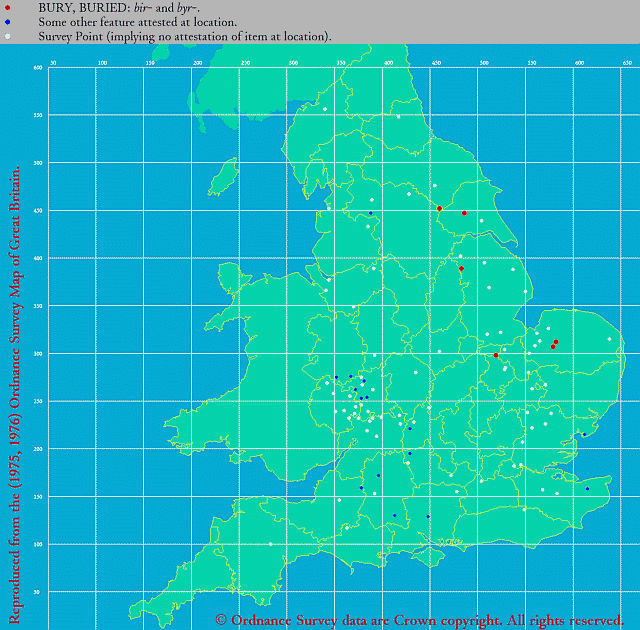

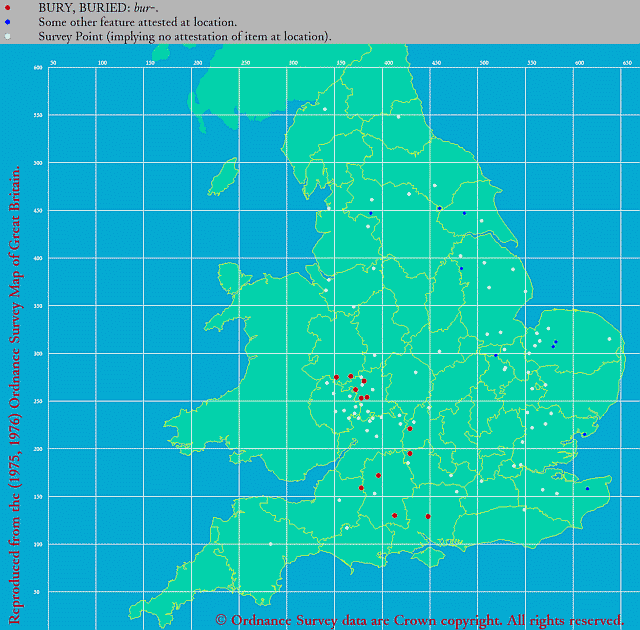

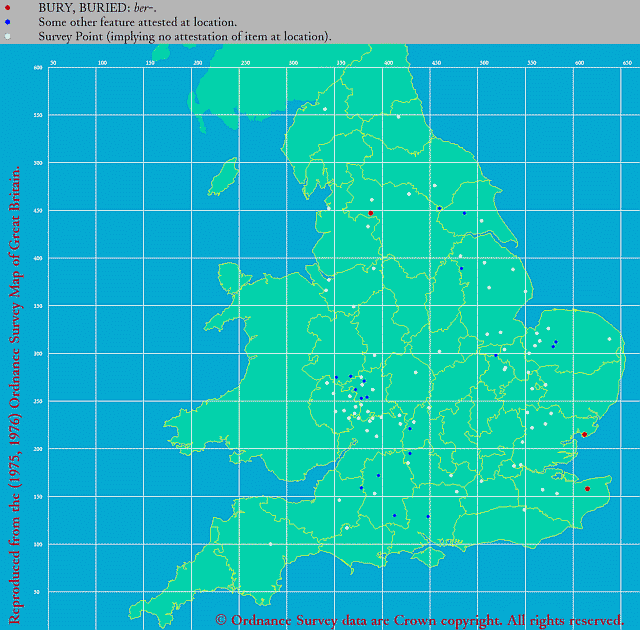

今回はとりわけ bury に焦点を当て,初期中英語の諸方言における第1母音(字)の変異を LAEME の Dot Map により示したい.この問題は,上の 「#562. busy の綴字と発音」 ([2010-11-10-1]) や「#570. bury の母音の方言分布」 ([2010-11-18-1]) でも扱ってきたが,今回は専門的なツールを用いて信頼に足る証拠を示すことに重点を置く.以下,当該母音(字)として <i, y> を用いる分布図の Dot Map を最初に挙げ,続いて2つ目に <u>,3つ目に <e> に関する Dot Map を示す.

(1) BURY, BURIED: bir- and byr-. (Map No. 16255502)

(2) BURY, BURIED: bur-. (Map No. 16255503)

(3) BURY, BURIED: ber-. (Map No. 16255501)

「#1262. The LAEME Corpus の代表性 (1)」 ([2012-10-10-1]),「#1263. The LAEME Corpus の代表性 (2)」 ([2012-10-11-1]) でみたように,LAEME の扱う(および初期中英語期一般についていえる)テキスト分布の事情により,全体として調査点 (dots) の数は多くはないものの,本記事の冒頭に示した伝統的な図式は,上の3つの地図により概ね支持されているといえよう.

なお,続く後期中英語における状況は,LAEME の姉妹版 LALME の Dot Map で確認できるが,後期には諸方言形が互いに激しく「乗り入れ」しており,初期ほど明確な分布は現われない.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2020-05-27 Wed

■ #4048. much, shut, such, trust の母音と中英語方言学 [vowel][me_dialect][dialectology][centralisation]

中英語方言学では,よく知られた母音の変異がある.古英語ウェストサクソン方言で <y> と綴られた母音(古英語初期では [y(ː)],後期では [i(ː)] とされる)の中英語での対応形が,典型的に北部・東部方言では <i> = [i(ː)] として,中西部方言では <u> = [y(ː)] として,南東部方言では <e> = [e(ː)] として現われるというものである.これについては,以下の記事で話題にしてきた.

・ 「#562. busy の綴字と発音」 ([2010-11-10-1])

・ 「#563. Chaucer の merry」 ([2010-11-11-1])

・ 「#570. bury の母音の方言分布」 ([2010-11-18-1])

・ 「#1341. 中英語方言を区分する8つの弁別的な形態」 ([2012-12-28-1])

・ 「#1434. left および hemlock は Kentish 方言形か」 ([2013-03-31-1])

この母音変異は,中英語方言を大きく3区分してくれる分かりやすい指標として重宝されてきたが,中西部における <u> = [y(ː)] (特に短母音)については,関係する語群のすべてが,その伝統的な区分法できれいに説明できるわけではないということが指摘されている.Lass and Laing の研究を参照した Minkova (194--95) によれば,中西部の <u> = [y] は必ずしも水を漏らさぬ公式というわけではないようだ.

中西部方言の [y] は,従来の解釈によれば,やがて非円唇化して北部・東部方言と同様に [i] へ発達したとされる.しかし,実際には非円唇化せず,むしろ後舌化して [u] となったとおぼしき語が一定数観察される.この後舌化した [u] は,さらに後の近代英語期に中舌化を経て現代標準英語の [ʌ] になったため,現代標準英語の <u> = [ʌ] の対応で考えると分かりやすい.具体的にいえば,blush, church, churn, clutch, crutch, cudgel, dung, furze, hurdle, much, shut, shuttle, such, sundry, thrush, thud, trust 等である.これらの語における [ʌ] 音は,古英語や中英語の中西部方言の [y] を入力とし,おそらく中英語期中に後舌化して [u] となったものが,さらに近代英語期に中舌化したものと考えるほかない.

ただし,上で想定されている中英語期の後舌化は短母音 [y] に起こりこそすれ,原則として長母音 [y(ː)] には起こっていないのである.少なくとも中英語から近現代英語にかけて予想される [yː] → [uː] → [əʊ] の発達を示す語は存在しない.

標題の語はいずれも日常語だが,歴史的には謎の多い方言に由来する謎の母音を含んでいるのである.

母音の中舌化については,「#1297. does, done の母音」 ([2012-11-14-1]) と「#1866. put と but の母音」 ([2014-06-06-1]) の記事を参照.

・ Lass, Roger and Margaret Laing. "Are Front Rounded Vowels Retained in West Midlands Middle English?" Rethinking Middle English: Linguistic and Literary Approaches. Ed. Nikolaus Ritt and Herbert Schendl. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2005. 280--90.

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

2019-12-01 Sun

■ #3870. 中英語の北部方言における wh- ならぬ q- の綴字 [spelling][me_dialect][labiovelar][lalme][laeme][map]

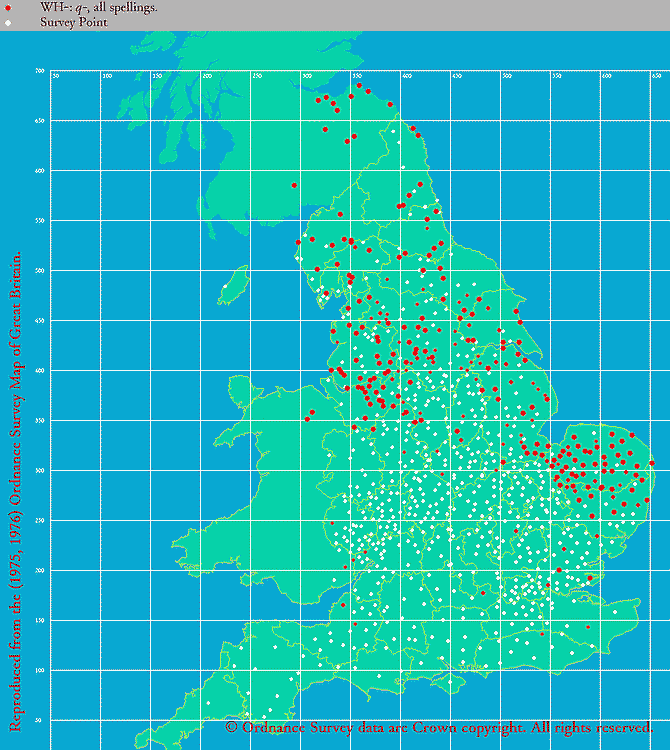

中英語方言学ではよく知られているが,イングランドの北部や東部の方言では,疑問詞に典型的に現われる軟口蓋唇音 (labiovelar) が,一般的な wh- などの綴字ではなく,quh-, qvh, qwh, qh などの綴字で現われることが多い.たとえば what に対応する綴字をいくつか挙げてみると,qwhat, qwat, quat, quad, qhat のごとくである.これは問題の子音の調音が北部系方言と南部系方言の間で異なっていたことを示唆するが,具体的にどのような違いだったのかについては議論がある.(なお,北部系方言においては wh- などの綴字も普通に使われており,それと平行して q- もよく使われていたということである.)

後期中英語における q- の地理的な分布は,実にきれいである.eLALME の Item 44 として取り上げられている,"WH-: q-, all spellings." と題された Dot Map を以下に再掲しよう.

少しさかのぼって初期近代英語においても,LAEME の Map 28285405 の Dot Map を見るとわかるように,数こそ少ないが,やはり北部と東部に分布している.

当時,イングランド北部と地続きのスコットランドでも quh- などの綴字が一般的に用いられていた.しかし,16世紀以降になると,イングランドの標準的綴字の影響により,スコットランド英語でも quh- の立場は弱まっていった.そのくだりについては明日の記事で.

2019-10-14 Mon

■ #3822. 『英語教育』の連載第8回「なぜ bus, bull, busy, bury の母音は互いに異なるのか」 [rensai][notice][vowel][spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][me_dialect][sound_change][phonetics][standardisation][sobokunagimon][link]

10月12日に,『英語教育』(大修館書店)の11月号が発売されました.英語史連載「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ」の第8回となる今回の話題は「なぜ bus, bull, busy, bury の母音は互いに異なるのか」です.

英語はスペリングと発音の関係がストレートではないといわれますが,それはとりわけ母音について当てはまります.たとえば,mat と mate では同じ <a> のスペリングを用いていながら,前者は /æ/,後者は /eɪ/ と発音されるように,1つのスペリングに対して2つの発音が対応している例はざらにあります.逆に同じ発音でも異なるスペリングで綴られることは,meat, meet, mete などの同音異綴語を思い起こせばわかります.

今回の記事では <u> の母音字に注目し,それがどんな母音に対応し得るかを考えてみました.具体的には bus /bʌs/, bull /bʊl/, busy /ˈbɪzi/, bury /ˈbɛri/ という単語を例にとり,いかにしてそのような「理不尽な」スペリングと発音の対応が生じてきてしまったのかを,英語史の観点から解説します.記事にも書いたように「現在のスペリングは,異なる時代に異なる要因が作用し,秩序が継続的に崩壊してきた結果の姿」です.背景には,あっと驚く理由がありました.その謎解きをお楽しみください.

今回の連載記事と関連して,本ブログの以下の記事もご覧ください.

・ 「#1866. put と but の母音」 ([2014-06-06-1])

・ 「#562. busy の綴字と発音」 ([2010-11-10-1])

・ 「#570. bury の母音の方言分布」 ([2010-11-18-1])

・ 「#1297. does, done の母音」 ([2012-11-14-1])

・ 「#563. Chaucer の merry」 ([2010-11-11-1])

・ 堀田 隆一 「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ 第8回 なぜ bus, bull, busy, bury の母音はそれぞれ異なるのか」『英語教育』2019年11月号,大修館書店,2019年10月12日.62--63頁.

2019-09-02 Mon

■ #3780. Foley による「標準英語の発展」の記述 [standardisation][hel_education][demography][me_dialect][black_death][printing][caxton]

私たちが普段学び,用いている標準英語 (Standard English) が,歴史上いかに発展してきたかという話題は,英語史の最重要テーマの1つであり,本ブログでも standardisation の記事を中心に様々に取り上げてきた(とりわけ「#3231. 標準語に軸足をおいた Blake の英語史時代区分」 ([2018-03-02-1]),「#3234. 「言語と人間」研究会 (HLC) の春期セミナーで標準英語の発達について話しました」 ([2018-03-05-1]) を参照).

英語の標準化の歴史は,どの英語史の概説書でも必ず取り上げられる話題だが,人類言語学の概説書を著わした Foley の書いている "The Development of Standard English" という1節が,すこぶるよい文章である.要点を押さえながら,教科書的な標準英語の発展を非常に上手にまとめている.3ページ弱にわたるので,引用するのにも決して短くはないが,授業の講読の題材としても使えそうなので,PDFでこちらに用意しておく.

この記述がすぐれている点の1つは,標準英語のベースとなるロンドン英語が諸方言の混合物であることについて,歴史的経緯を分かりやすく説明してくれていることだ.もともと南部方言的な要素を多分に含んでいたロンドンの英語が,14--15世紀のあいだに,経済的に繁栄していた中東部からの人口流入を受けて中部方言的な要素を獲得した.ここには,14世紀後半からの黒死病に起因する人口流動性の高まりも相俟っていたろう.さらに,15世紀中には,羊毛製品で経済的に潤った北部方言の話者も,多くロンドンの上流層へ流れ込み,結果として,諸方言の混合としてのロンドン英語が成立した.そして,これが後の標準英語の母体となっていったのである.

もう1つ注目すべきは,英語史に限定されない一般的な立場から,言語の標準化の3つの条件を提示して議論を締めくくっている点である.1つは,経済的・政治的に有力な地域の言語・方言が標準語の土台となるということ.もう1つは,その言語・方言がエリート集団のものであること.最後に,文学伝統をもった言語・方言が標準語の土台となりやすいことだ.この下りだけでも,以下に直接引用しておきたい.

To summarize, the rise of Standard English . . . exhibits a number of important general points about the how and whys of language standardization: first, if economic and political power is centralized in a particular area, the language of that area has a strong likelihood of being the basis of the standard, as the center imposes its hold upon the periphery (Standard French based on the Parisian dialect is another example of this); second, the standard is likely to be based on the speech of economically and politically powerful social groups, the elite, as their speech becomes imposed upon or diffused to lower status groups; ability to speak this dialect now becomes emblematic of higher social standing and thus a desirable skill, a kind of symbolic resource further empowering the elite, who may control access to the dialect through the education system, as is clearly the case in most modern nation-states; and third, a language or dialect which is the basis of literate forms and other cultural activities is a strong candidate for an imposed standard (Standard Italian based on the Tuscany dialect of Dante exemplifies this). (Foley 403)

・ Foley, William A. Anthropological Linguistics: An Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1997.

2019-08-21 Wed

■ #3768. 「漢字は多様な音をみえなくさせる,『抑制』の手段」 [standardisation][japanese][writing][alphabet][grammatology][kanji][romaji][me_dialect]

昨日の記事「#3767. 日本の帝国主義,アイヌ,拓殖博覧会」 ([2019-08-20-1]) に引き続き,金田一京助の言語観について.金田一は,日本語表記のローマ字化の運動には与していなかった.ヘボン式か日本式かという論争にも首を突っ込まなかったようだ.同郷の歌人で『ローマ字日記』を書いた石川啄木が関心を寄せた社会主義にはぞっとしなかったと回想しているが(安田,p. 176--77),ローマ字化と社会主義化を関連づけて考えていた節がある.アイヌ語をローマ字やカタカナで書き取っていた金田一にとって,日本語をそれと同一にしたくないという思いがあったのかもしれない.

安田 (177) は,金田一のローマ字観や仮名観,およびその裏返しとしての漢字観について,次のように引用し,説明している.

「方言は保存すべきか」(一九四八)で,「今後世の中が表音式仮名遣となつて行き,またローマ字書きとなつて行つて,方言がそのまゝ書き出されたら,日本の言語がどういふことになるであらうか」とも述べている.発音をそのままに書くようにすると,そこにもたらされるのは混乱と分裂でしかない,という認識をとりだすことができる.社会主義のイメージとも連動しているのではないだろうか.漢字は金田一にとっては「圧制」というよりも多様な音をみえなくさせる,「抑制」の手段だったのかもしれない」

古今東西の言語の歴史において,いかなる権力をもってしても,人々の話し言葉の多様性を完全に抑え込むことができたためしはない.しかし,書き言葉において,そのような話し言葉の多様性を形式上みえなくさせることはできる.実際,文字をもつ近代社会の多くでは,書き言葉の標準化の名のもとに,まさにそのことを行なってきたのである.その際に,表語文字を用いたほうが,発音上の多様性をみえなくさせやすいことはいうまでもない.表音文字は,その定義通り発音をストレートに表わしてしまうために,発音上の多様性を覆い隠すことが難しい.一般的にいえば,表語文字と表音文字とでは,前者のほうが標準化に向いているということかもしれない.多様性を抑制する手段としての表語文字,というとらえ方は的を射ていると思う.

上に述べられている「発音をそのままに書くようにすると,そこにもたらされるのは混乱と分裂でしかない,という認識」は,私たちにも共感しやすいのではないだろうか.しかし,英語史をみれば,中英語期がまさにそのような混乱と分裂の時代だったのである.ただ,その後期にかけては標準的な綴字が発達していくことになる.「#929. 中英語後期,イングランド中部方言が標準語の基盤となった理由」 ([2011-11-12-1]),「#1311. 綴字の標準化はなぜ必要か」 ([2012-11-28-1]),「#1450. 中英語の綴字の多様性はやはり不便である」 ([2013-04-16-1]) をはじめ me_dialect の各記事を参照.

・ 安田 敏朗 『金田一京助と日本語の近代』 平凡社〈平凡社新書〉,2008年.

2019-06-16 Sun

■ #3702. 中英語の3人称複数対格代名詞 es はオランダ語からの借用か? (2) [personal_pronoun][laeme][lalme][me_dialect][clitic][map][dutch]

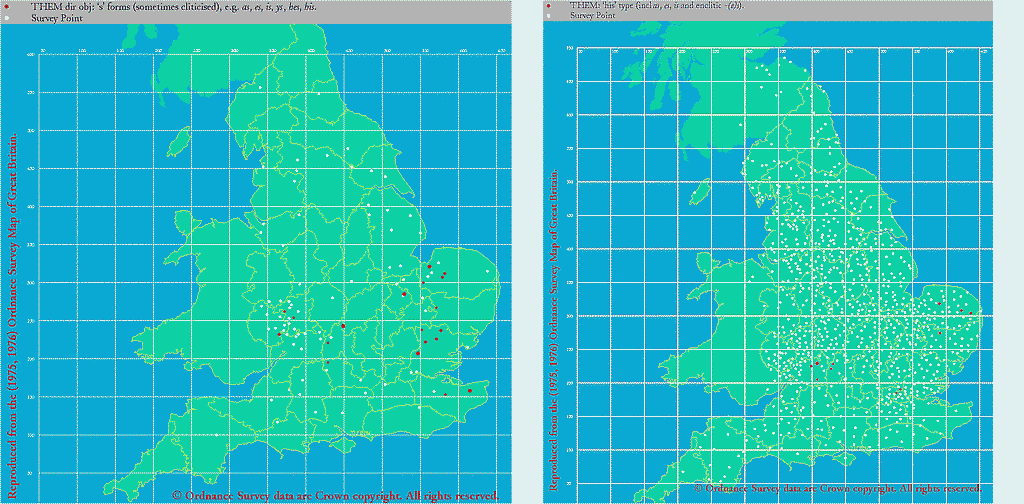

昨日の記事 ([2019-06-15-1]) に引き続き,中英語の them の代わりに用いられる es という人称代名詞形態について.Bennett and Smithers の注を引用して,およそ "SE or EMidl" に使用が偏っていると述べたが,LAEME と eLALME を用いて,初期・後期中英語における状況を確認しておこう.

LAEME では Map No. 00064420 として "THEM dir obj: 's' forms (sometimes cliticised), e.g. as, es, is, ys, hes, his." が挙げられており(下左図),eLALME では Item 8 として "THEM: 'his' type (incl as, es, is and enclitic -(e)s)." が挙げられている(下右図).ここでは縮小して掲げているので,詳しくはクリックして拡大を.

全体として例が多いわけではないが,中英語期を通じて East Midland と Southeastern を中心として,部分的には内陸の West Midland にも散見されるといった分布を示していることが分かる.

オランダ語との関連を議論するためには,当時のオランダ語話者集団のイングランドへの移民状況などの歴史社会言語学的な背景を調べる必要がある.一般的にいえば,「#3435. 英語史において低地諸語からの影響は過小評価されてきた」 ([2018-09-22-1]) でみたように,14世紀辺りには毛織物貿易の発展によりフランドルと東イングランドの関係は緊密になったことから,East Midland における es や類似形態の分布に関しては,オランダ語影響説を論じ始めることができるかもしれない.しかし,West Midland の散発的な事例については,別に考えなければならないだろう.

・ Bennett, J. A. W. and G. V. Smithers, eds. Early Middle English Verse and Prose. 2nd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1968.

2019-06-15 Sat

■ #3701. 中英語の3人称複数対格代名詞 es はオランダ語からの借用か? (1) [personal_pronoun][me_dialect][dutch][borrowing][havelok][clitic]

Bennett and Smithers 版で14世紀初頭の作品といわれる Havelok を読んでいる.East Midland 方言で書かれており,古ノルド語からの借用語を多く含んでいることが知られているが,East Midland はオランダ語からの影響も取り沙汰される地域である.

Havelok より ll. 45--52 のくだりを引用しよう.

Þanne he com þenne he were bliþe,

For hom he brouthe fele siþe

Wastels, simenels with þe horn,

Hise pokes fulle of mele an korn,

Netes flesh, shepes, and swines,

And hemp to maken of gode lines,

And stronge ropes to hise netes

(In þe se-weres he ofte setes).

最後の行は he often set them in the sea-weir を意味し,setes の -es は前行の hise netes (= "his nets") を指示する接語化された3人称複数対格の代名詞と解釈できる.要するに "them" として用いられる -es というわけだが,この形態について Bennett and Smithers (293) は注で次のように解説している.

setes: i.e. sette es 'placed them'. Es, is (ys in Hav. 1174), hes, his, hise are first recorded in England c. 1200, as the acc.pl. or fem. sg. of the pronoun of the third person, and (apart from 'Robt. of Gloucester's' Chronicle are restricted to SE or EMidl texts. This pronoun is best explained as an adoption of the comparable MDu pronoun se, which is likewise used enclitically in the reduced form -s; for a pronoun (as an essential and prominent element in the grammatical machinery of a language) would hardly have escaped record till 1200 if it had been a native word.

つまり,問題の -es は中期オランダ語の対応する形態を借用したものだということである.この説を評価するに当たっては関連する事項を慎重に調査していく必要があるが,英語史においてオランダ語の影響が過小評価されてきたことを考えると,魅力的な問題ではある.

英語史とオランダ語の関わりについては,「#3435. 英語史において低地諸語からの影響は過小評価されてきた」 ([2018-09-22-1]),「#3436. イングランドと低地帯との接触の歴史」 ([2018-09-23-1]),「#126. 7言語による英語への影響の比較」 ([2009-08-31-1]),「#2645. オランダ語から借用された馴染みのある英単語」 ([2016-07-24-1]),「#2646. オランダ借用語に関する統計」 ([2016-07-25-1]),「#140. オランダ・フラマン語から借用した指小辞 -kin」 ([2009-09-14-1]) を含め dutch の記事を参照

・ Bennett, J. A. W. and G. V. Smithers, eds. Early Middle English Verse and Prose. 2nd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1968.

2019-03-14 Thu

■ #3608. 中英語における <u> の <o> による代用 (4) [spelling][orthography][minim][vowel][spelling_pronunciation_gap][eme][me_dialect][lexical_diffusion]

昨日の記事 ([2019-03-13-1]) に引き続いての話題.中英語における <u> と <o> の分布を111のテキストにより調査した Wełna (317) は,結論として以下のように述べている.

. . . the examination of the above corpus data has shown a lack of any consistent universal rule replacing <u> with <o> in the graphically obscure contexts of the postvocalic graphemes <m, n>. Even words with identical roots, like the forms of the lemmas SUN (OE sunne), SUMMER (OE sumor) and SON (OE sunu), SOME (OE sum) which showed a similar distribution of <u/o> spellings in most Middle English dialects, eventually (and unpredictably) have retained either the original spelling <u> (sun) or the modified spelling <o> (son). In brief, each word under discussion modified its spelling at a different time and in different regions in a development which closely resembles the circumstances of lexical diffusion.

このように奥歯に物が挟まったような結論なのだが,Wełna は時代と方言の観点から次の傾向を指摘している.

. . . o-spellings first emerged in the latter half of the 12th century in the (South-)West (honi "honey" . . .). Later, a tendency to use the new spelling <o> is best documented in London and in the North.

Wełna 本人も述べているように,調査の対象としたレンマは HUNDRED, HUNGER, HONEY, NUN, SOME, SUMMER, SUN, SON の8つにすぎず,ここから一般的な結論を引き出すのは難しいのかもしれない.さらなる研究が必要のようだ.

・ Wełna, Jerzy. "<U> or <O>: A Dilemma of the Middle English Scribal Practice." Contact, Variation, and Change in the History of English. Ed. Simone E. Pfenninger, Olga Timofeeva, Anne-Christine Gardner, Alpo Honkapohja, Marianne Hundt and Daniel Schreier. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins, 2014. 305--23.

2018-10-10 Wed

■ #3453. ノルマン征服がイングランドの地名に与えた影響 [toponymy][onomastics][norman_conquest][me_dialect]

デイヴィスとレヴィット (168--69) は,ノルマン征服 (norman_conquest) が地名(史)に及ぼしたインパクトについて次のように述べている.

英語圏内にみられる様々な方言への分岐が加速されたことであった.このため,英語は統治のための手段ではなくなり,全国どこでも通じる意志〔ママ〕伝達の均一の手段ではなくなってしまった.また,以前とは違って,教育や文学のための言語でもなくなった.その結果,どんな言語にでも常に息づいている,方言として周囲に拡散する傾向が自由を得て,これまで英語に存在していた保守的な勢力が消滅していった.従って,英語は豊かな方言形式を発達させ,方言は地名に大きな影響を与えた.地名の成立にではなく,時代を経ての地名継承のあり方に大きな影響を及ぼした.

この点はなるほどと思った.標準語が存在する言語においては,一般語彙に関して,広く通用する「標準形」と各地で行なわれる種々の「方言形」がありうる.しかし,地名語彙には,通常「標準形」と「方言形」という区別はない.地名は広く参照される語なので,機能的には標準的でなければならないが,形式的には標準的とされるものが採用される必要はない.それは,地名が何かを意味している必要はなく,その場所を参照していればよいという記号論的に特殊な性質を持ち合わせていることと関係しているだろう(この点については,「#2212. 固有名詞はシニフィエなきシニフィアンである」 ([2015-05-18-1]),「#2397. 固有名詞の性質と人名・地名」 ([2015-11-19-1]) を参照).

中英語期の方言分化と地名の関係がよく見える形で表われている例の1つが,hill や mill の母音の変異である.「#1812. 6単語の変異で見る中英語方言」 ([2014-04-13-1]) でみたように,この母音は南東部では e として,西部では u として,それ以外では i として実現される.それぞれの分布について,デイヴィッドとレヴィット (216--17) に次のように記述がある.

e を用いていた地域(主にケント)からはヘルステッド (Helsted),ワームズヒル(Wormshill, 1232年の記録では Wodnesell, 意味はおそらく Woden's Hill 「ウォドンの丘」),ミルトン (Milton, カンタベリーの近く.tun by a mill 「粉引き場の近くの町」の意味で,1242年の記録では Meleton).

u を用いていた地域からはスタッフォードシャーのペンクハル (Penkhull, ブリトン語の人名 Pencet に英語の hill が付け加えられている),グロスターシャーのラッジ(Rudge, ridge 「山の尾根」),ランカシャーのハルトン (Hulton, tun on a hill 「丘の上にある町」),スタッフォードシャーのミルトン (Milton) は以前 (1227年)は Mulneton だった.

i を用いていた地域からの例は多数あり,最初期の頃にしばしば u が用いられ,その起源はイースト・ミッドランド及び北部の方言形 i が別個に発展する以前に遡る.

地名学,方言学,音変化の研究は,ともに手を携えて進むべき仲間である.

・ デイヴィス,C. S.・J. レヴィット(著),三輪 伸春(監訳),福元 広二・松元 浩一(訳) 『英語史でわかるイギリスの地名』 英光社,2005年.

2018-08-16 Thu

■ #3398. 中英語期の such のワースト綴字 [spelling][eme][lme][me_dialect][levenshtein_distance]

昨日の記事「#3397. 後期中英語期の through のワースト綴字」 ([2018-08-15-1]) に引き続き,今回は such の異綴字について.「#2520. 後期中英語の134種類の "such" の異綴字」 ([2016-03-21-1]),「#2521. 初期中英語の113種類の "such" の異綴字」 ([2016-03-22-1]) で見たように,私の調べた限り,中英語全体では such を表記する異綴字が212種類ほど確認される.そのうちの208種について,昨日と同じ方法で現代標準綴字の such にどれだけ類似しているかを計算し,似ている順に列挙してみた.

| Similarity | Spellings |

|---|---|

| 1.0000 | such |

| 0.8889 | sƿuch, shuch, succh, suche, sucht, suech, suich, sulch, suuch, suych, swuch |

| 0.8571 | suc |

| 0.8000 | sƿucch, sƿuche, schuch, scuche, shuche, souche, sucche, suchee, suchet, suchte, sueche, suiche, suilch, sulche, sutche, suuche, suuech, suyche, swuche, swulch |

| 0.7500 | sƿuc, scht, sech, shuc, sich, soch, sueh, suhc, suhe, suic, sulc, suth, suyc, swch, swuh, sych |

| 0.7273 | sƿucche, sƿuchne, sƿulche, schuche, suecche, suueche, suweche |

| 0.6667 | hsƿucche, sƿche, sƿich, sƿucches, sƿulc, schch, schuc, schut, seche, shich, shoch, shych, siche, soche, suicchne, suilc, svche, svich, swche, swech, swich, swlch, swulchen, swych, syche, zuich, zuych |

| 0.6154 | swulchere |

| 0.6000 | asoche, sƿiche, sƿilch, sƿlche, sƿuilc, sƿulce, schech, schute, scoche, scwche, secche, shiche, shoche, sowche, soyche, sqwych, suilce, sviche, sweche, swhych, swiche, swlche, swyche, zuiche, zuyche |

| 0.5714 | sec, sic, sug, swc, syc |

| 0.5455 | aswyche, sƿicche, sƿichne, sƿilche, sƿi~lch, scheche, schiche, schilke, schoche, sewyche, sqwyche, sswiche, swecche, swhiche, swhyche, swichee, swyeche, zuichen |

| 0.5333 | sucheȝ |

| 0.5000 | sƿic, sɩͨh, scli, secc, sick, silc, slic, solchere, sulk, swic, swlc, swlchere, swulcere |

| 0.4444 | sƿilc, sclik, sclyk, suilk, sulke, suylk, swics, swilc |

| 0.4000 | sƿillc, sclike, sclyke, squike, squilk, squylk, suilke, suwilk, suylke, swilce, swlcne, swulke, swulne |

| 0.3636 | sƿilcne, suilkin, swhilke |

| 0.3333 | swisɩͨhe |

| 0.2857 | sik, sli, slk, sly, syk |

| 0.2500 | selk, sike, silk, slik, slyk, swil, swlk, swyk, swyl, syge, syke, sylk |

| 0.2222 | sƿilk, selke, sliik, slike, slilk, slyke, swelk, swilk, swlke, swyke, swylk, sylke |

| 0.2000 | slieke, slkyke, swilke, swylke, swylle |

| 0.1818 | sƿillke, swilkee, swilkes |

これによると,歴史的なワースト綴字は sƿillke, swilkee, swilkes の3つということになる.確かに・・・.

2018-08-15 Wed

■ #3397. 後期中英語期の through のワースト綴字 [spelling][lme][me_dialect][levenshtein_distance][through]

「#53. 後期中英語期の through の綴りは515通り」 ([2009-06-20-1]),「#54. through 異綴りベスト10(ワースト10?)」 ([2009-06-21-1]) で紹介したように,後期中英語の through の綴字は,著しくヴァリエーションが豊富である.そこではのべ515通りの綴字を集めたが,ハイフン(語の一部であるもの),イタリック体(省略符号などを展開したもの),上付き文字,大文字小文字の違いの有無を無視すれば,444通りとなる.この444通りの綴字について,現代の標準綴字 through にどれだけ近似しているかを,String::Similarity という Perl のモジュールを用いて計算させてみた.類似性の程度を求めるアルゴリズムは,文字変換の工程数 (Levenshtein edit distance) に基づくものである.完全に一致していれば 1.0000 の値を取り,まったく異なると 0.0000 を示す.では,「似ている」順に列挙しよう.

| Similarity | Spellings |

|---|---|

| 1.0000 | through |

| 0.9333 | thorough, throughe, throught |

| 0.9231 | throgh, throug, throuh, thrugh, trough |

| 0.8750 | thoroughe, thorought |

| 0.8571 | thorogh, thorouh, thorugh, thourgh, throȝgh, throghe, throght, throwgh, thrughe, thrught |

| 0.8333 | thogh, throu, thrug, thruh, trogh, trugh |

| 0.8000 | thoroghe, thoroght, thorouȝh, thorowgh, thorughe, thorught, thourghe, thourght, throȝghe, throghet, throghte, throighe, throuȝht, throuche, throwght, thrughte |

| 0.7692 | þrough, thorgh, thorou, thoruh, thourh, throȝh, throch, throuȝ, throue, throwg, throwh, thruch, thruth, thrwgh, thrygh, thurgh, thwrgh, troght, trowgh, trughe, trught |

| 0.7500 | thorowghe, thorowght |

| 0.7273 | thro |

| 0.7143 | þorough, þrought, thorȝoh, thorghe, thorght, thorghw, thorgth, thorohe, thorouȝ, thorowg, thorowh, thorrou, thoruȝh, thoruth, thorwgh, thourhe, thourth, thourwg, thowrgh, throȝhe, throcht, throuȝe, throwth, thruȝhe, thrwght, thurgeh, thurghe, thurght, thurgth, thurhgh, trowght, yorough |

| 0.6667 | þorought, þough, þrogh, þroughte, þrouh, þrugh, thorg, thorghwe, thorh, thoro, thorowth, thorowut, thoru, thour, throȝ, throw, thruȝ, thrue, thuht, thurg, thurghte, thurh, thuro, thuru, torgh, yrogh, yrugh |

| 0.6154 | þorogh, þorouh, þorugh, þourgh, þroȝgh, þroghe, þrouȝh, þrouhe, þrouht, þrowgh, þurugh, thorȝh, thorch, thoroo, thorow, thorth, thoruȝ, thorue, thorur, thorwh, thourȝ, thoure, thourr, thourw, thowur, throȝe, throȝt, throve, throwȝ, throwe, throwr, thruȝe, thrvoo, thurȝh, thurch, thurge, thurhe, thurow, thurth, torghe, trghug, yhurgh, yorugh, yourgh |

| 0.5714 | þoroghe, þorouȝh, þorowgh, þorught, þourght, þrouȝth, þrowghe, þurughe, thorowȝ, thorowe, thorrow, thorthe, thourȝe, thourow, thowrow, thrawth, throwȝe, thurȝhg, thurȝth, thurgwe, thurhge, thurowe, thurthe, yhurght, yourghe |

| 0.5455 | þrou, þruh, thow, thrw, thur, trow, yrou |

| 0.5333 | þorowghe, þorrughe, thorowȝt |

| 0.5000 | þorgh, þorou, þorug, þoruh, þourg, þourh, þroȝh, þroth, þrouȝ, þrowh, þurgh, þwrgh, ȝorgh, thorȝ, thorv, thorw, thowe, thowr, threw, thrwe, thurȝ, thurv, thurw, thwrw, trowe, yhorh, yhoru, yhrow, yorgh, yorou, yoruh, yourh, yurgh |

| 0.4615 | þhorow, þorghȝ, þorghe, þorght, þorguh, þorouȝ, þoroue, þorour, þorowh, þoruȝh, þorugȝ, þoruhg, þoruth, þorwgh, þourȝh, þourgȝ, þourth, þroȝth, þrouȝe, þrouȝt, þurgȝh, þurghȝ, þurghe, þurght, þuruch, dorwgh, dourȝh, drowgȝ, durghe, tþourȝ, thorȝe, thorȝt, thorȝw, thorew, thorwȝ, thorwe, thurȝe, thurȝt, thurew, thurwe, yorghe, yoroue, yorour, yourch, yurghe, yurght |

| 0.4286 | þorouȝe, þorouȝt, þorouwȝ, þorowth, þrouȝte, thorȝwe, thorewe, thorffe, thorwȝe, thowffe, trowffe |

| 0.4000 | þro |

| 0.3636 | ðoru, þorg, þorh, þoro, þoru, þouȝ, þour, þroȝ, þrow, þruȝ, þurg, þurh, þuro, þuru, ȝoru, ȝour, torw, twrw, yorh, yoro, yoru, your, yrow, yruȝ, yurg, yurh, yuru |

| 0.3333 | þerow, þerue, þhurȝ, þorȝh, þorch, þoreu, þorgȝ, þoroȝ, þorow, þorth, þoruþ, þoruȝ, þorue, þorwh, þouȝt, þourþ, þourȝ, þourt, þourw, þroȝe, þroȝt, þrowþ, þrowȝ, þrowe, þruȝe, þurȝg, þurȝh, þurch, þureh, þurhg, þurht, þurow, þurru, þurth, þuruȝ, þurut, ȝoruȝ, ȝurch, doruȝ, torwe, yoȝou, yorch, yorow, yoruȝ, yourȝ, yourw, yurch, yurhg, yurht, yurth, yurwh |

| 0.3077 | þorȝhȝ, þorowþ, þorowe, þorrow, þoruȝe, þoruȝt, þorwgȝ, þorwhe, þorwth, þourȝe, þourȝt, þourȝw, þourow, þouruȝ, þourwe, þrorow, þrowȝe, þurȝhg, þurȝth, þurthe, ȝoruȝt, yerowe, yorowe, yurowe, yurthe |

| 0.2857 | þrorowe |

| 0.2000 | þor, þur |

| 0.1818 | þarȝ, þorþ, þorȝ, þore, þorv, þorw, þowr, þurþ, þurȝ, þurf, þurw, ȝorw, ȝowr, dorw, yorȝ, yora, yorw, yowr, yurȝ, yurw |

| 0.1667 | þerew, þorȝe, þorȝt, þoreȝ, þorew, þorwȝ, þorwe, þowre, þurȝe, þurȝt, þureȝ, þurwȝ, þurwe, dorwe, durwe, yorwe, yowrw, yurȝe |

| 0.1538 | þorewȝ, þorewe, þorwȝe, þorwtȝ |

これによると,最も through とは似ていない,とんでもない綴字は,þorewȝ, þorewe, þorwȝe, þorwtȝ の4種類ということになる.そんなに似ていないかなあと思ってしまうのは,中英語のとんでもない綴字に見慣れてしまったせいだろうか・・・.ちなみに,現在アメリカ英語で省略綴字として用いられる thru は,後期中英語には,ありそうでなかったようだ.

2018-02-17 Sat

■ #3218. 講座「スペリングでたどる英語の歴史」の第3回「515通りの through --- 中英語のスペリング」 [slide][spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][norman_conquest][chaucer][manuscript][reestablishment_of_english][timeline][me_dialect][minim][orthography][standardisation][digraph][hel_education][link][asacul]

朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室で開講している講座「スペリングでたどる英語の歴史」も,全5回中の3回を終えました.2月10日(土)に開かれた第3回「515通りの through --- 中英語のスペリング」で用いたスライド資料を,こちらにアップしておきました.

今回は,中英語の乱立する方言スペリングの話題を中心に据え,なぜそのような乱立状態が生じ,どのようにそれが後の時代にかけて解消されていくことになったかを議論しました.ポイントとして以下の3点を指摘しました.

・ ノルマン征服による標準綴字の崩壊 → 方言スペリングの繁栄

・ 主として実用性に基づくスペリングの様々な改変

・ 中英語後期,スペリング再標準化の兆しが

全体として,標準的スペリングや正書法という発想が,きわめて近現代的なものであることが確認できるのではないかと思います.以下,スライドのページごとにリンクを張っておきました.その先からのジャンプも含めて,リンク集としてどうぞ.

1. 講座『スペリングでたどる英語の歴史』第3回 515通りの through--- 中英語のスペリング

2. 要点

3. (1) ノルマン征服と方言スペリング

4. ノルマン征服から英語の復権までの略史

5. 515通りの through (#53, #54), 134通りの such

6. 6単語でみる中英語の方言スペリング

7. busy, bury, merry

8. Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales の冒頭より

9. 第7行目の写本間比較 (#2788)

10. (2) スペリングの様々な改変

11. (3) スペリングの再標準化の兆し

12. まとめ

13. 参考文献

2017-09-06 Wed

■ #3054. 黒死病による社会の流動化と諸方言の水平化 [black_death][reestablishment_of_english][history][demography][me_dialect][sociolinguistics][dialect_levelling]

英語史では中世における英語の復権と関連して,たいてい黒死病のことが触れられる.しかし,簡単に言及されるにとどまり,突っ込んだ説明のないものも多い.そのなかで,一般向けの英語史読本を著わした Gooden (67--68) は,黒死病に対して1節を割くほどの関心を示している.読み物としておもしろいので引用しておこう.なお,引用の第2段落の1部は,Black Death の語源と関連して「#2990. Black Death」 ([2017-07-04-1]) でも取りあげた.

The Black Death had a devastating effect on the British Isles, as on the rest of Europe. The population of England was cut by anything between a third and a half. Probably originating in Asia, the plague arrived in a Dorset port in the West country in 1348, rapidly spreading to Bristol and then to Gloucester, Oxford and London. If a rate of progress were to be allotted to the plague, it was advancing at about one-and-a-half miles a day. The major population centres, linked by trading routes, were the most obviously vulnerable but the epidemic had reached even the remotest areas of western Ireland by the end of the next decade. Symptoms such as swellings (the lumps or buboes that characterize bubonic plague), fever and delirium were almost invariably followed within a few days by death. Ignorance of its cause heightened panic and public fatalism, as well as hampering effectual preventive measures. Although the epidemic petered out in the short term, the disease did not go away, recurring in localized attacks and then major outbreaks during the 17th century which particularly affected London. One of them disrupted the preparations for the coronation of James I in 1603; the last major epidemic killed 70,000 Londoners in 1665.

The term 'Black Death' came into use after the Middle Ages. It was so called either because of the black lumps or because in the Latin phrase atra mors, which means 'terrible death', atra can also carry the sense of 'black'. To the unfortunate victims, it was the plague, or, more often, the pestilence. So Geoffrey Chaucer calls it in The Pardoner's Tale, where he makes it synonymous with death. The words survive in modern English even if with a much diminished force in colloquial use: 'He's a pest.' 'Stop plaguing us!' Curiously, although pest in the sense of 'nuisance' has its roots in pestilence, the word pester comes from a quite different source, the Old French empêtrer ('entangle', 'get in the way of').

The impact of the pestilence on English society was profound. Quite apart from the psychological effects, there were practical consequences. Labour shortages meant a rise in wages and more fluid social structure in which the old feudal bonds began to break down. Geographical mobility would also have helped in dissolving regional distinctions and dialect differences.

黒死病による人口減少により,生き残った労働者の賃金が上がり,彼らの社会的地位が上昇するとともに彼らの母語である英語の社会的地位も上昇した,というのが黒死病の英語史上のインパクトと言われる.しかし,引用の最後にあるように,人々が社会的にも地理的にも流動化したという点にも注目すべきである.これにより,人々がますます混交し,とりわけロンドンのような都会では諸方言が水平化してゆく契機となった (cf. dialect levelling) .黒死病は,確かに英語の行く末に間接的な影響を与えたといえるだろう.

・ Gooden, Philip. The Story of English: How the English Language Conquered the World. London: Quercus, 2009.

2016-10-31 Mon

■ #2744. 大母音推移の社会音韻論的考察 (3) [gvs][sociolinguistics][meosl][me_dialect][contact][vowel][phonetics]

「#2714. 大母音推移の社会音韻論的考察」 ([2016-10-01-1]),「#2724. 大母音推移の社会音韻論的考察 (2)」 ([2016-10-11-1]) に続き,第3弾.第2弾の記事 ([2016-10-11-1]) で,System II の母音体系をもっていたとされる多くの南部・中部方言話者が,権威ある System I のほうへ過剰適応 (hyperadaptation) したことが大母音推移 (gvs) の引き金となった,との説を紹介した.しかし,Smith (106--07) によると,もう1つ GVS の引き金となった母音体系をもった話者集団がいたという.それは,"Easterners" と呼ばれる,おそらく East Anglia 出身の人々である.

East Anglia では,14世紀後半から15世紀にかけてロンドンで進行し始めた大母音推移と類似する推移が,ずっと早くに生じていた.背景として,古英語の Saxon 方言の ǣ に対して Anglia 方言では ē をもっていたこと,/d, t, n, s, l, r/ の前位置で上げ (raising) を経ていたことなどがあった.この推移の結果として,East Anglia の母音体系は,3段階の高さで5つの長母音をもつ /iː, uː, eː, oː, aː/ となっていた.

さて,この Easterners が,15世紀の前半から半ばにかけて都市化の進むロンドンへ移住し,ロンドン英語,特に権威ある System I の話者と接触したときに,もう1つの過剰適応が引き起こされた.3段階の East Anglia の体系が,さらに細かく段階区分された System I と接触したとき,前者は後者の威信ある調音に引かれて,全体として調音位置の調整を迫られることになった.具体的には,Easterners は System I の [æː] を自分たちの /eː/ と知覚して後者として発音し,同様に [eː̝] を /iː/ と知覚して,そのように発音した.3段階しかもたない Easterners にとって,中英語の /eː/ をもつ語と /ɛː/ をもつ語の区別はつけられなかったので,結局いずれも /iː/ として知覚され,発音されることになった.およそ同じことが後舌系列の母音にも起こった.

System III というべき Easterners のこの母音体系は,実は,後に18世紀までに勢力を得て一般化し,現代標準英語の meed, mead, maid, made などに見られる一連の母音の(不)区別を生み出す母体となった.その点でも,英語母音史上,大きな役割を担った母音体系だったといえるだろう.

・ Smith, Jeremy J. An Historical Study of English: Function, Form and Change. London: Routledge, 1996.

2016-10-11 Tue

■ #2724. 大母音推移の社会音韻論的考察 (2) [gvs][sociolinguistics][chaucer][meosl][me_dialect][contact][vowel][diphthong]

「#2714. 大母音推移の社会音韻論的考察」 ([2016-10-01-1]) に引き続き,大母音推移 (gvs) という音韻論上の過程を社会言語学的な観点から説明しようとする試みについて考える.前の記事では1つの見方を概論的に紹介した程度だったが,諸家によって想定される母音の分布や関係する英語変種は若干異なっている.今回は,Smith (101--06) に従って,もう1つの社会音韻論的な説明を覗いてみよう.

Smith は,Chaucer の時代までにロンドンでは2つの異なる母音体系が並存していたと仮定している(Smith (102) からの下図を参照).System I は,Chaucer に代表される上層階級に属する人々のもっていた体系であり,前舌系列が5段階と複雑だが,社会的な威信をもっていたと考えられる.* の付された長母音は,対応する短母音が中英語開音節長化 (Middle English Open Syllable Lengthening; meosl) を経て若干位置を下げながら長化した音である.一方,System II は,それ以外の多くのイングランド南部・中部方言の話者がもっていた体系であり,前舌系列が4段階だったと想定されている.

| System I | System II | |||||||||||||||||

| iː | > | ɪi | uː | > | ʊu | iː | > | əɪ | uː | > | əʊ | |||||||

| eː | > | eː̝ | oː | > | oː̝ | eː | > | iː | oː | > | uː | |||||||

| ɛː̝* | ɔː̝* | ɛː | > | eː | ɔː | > | oː | |||||||||||

| ɛː | ɔː | aː* | > | ɛː, eː | ||||||||||||||

| aː* | > | æː | ||||||||||||||||

このような2つの体系が15世紀初頭のロンドンで接触したときに,結果として System II の話者が社会的上昇志向から System I の方向への「上げ」 (raising) を生じさせることになったのだという.

まず,System II 話者の [ɛː] について考えよう.System II 話者は,System I 話者の [ɛː] と [ɛː̝*] の各々がどの単語に現われるのか区別できないこと,及び System I 話者の [ɛː̝*] に現われるやや高い調音を模倣したいことから,全体として自らの [ɛː] を若干上げ,結果として [eː] と発音するに至る.

次に,System II 話者のもともとの [eː] は,System I 話者の [eː] のやや高い調音(おそらく System I 話者の慣れていたフランス語の緊張した調音の影響を受けたやや高めの異音)を過剰気味 (hyperadaptation) に模倣した結果,[iː] と発音するに至った.

最後に,System II 話者の [aː*] については,少々ややこしい事情があった.System II の [aː*] は a の開音節長化により生じた新しい音だったが,同時代の Essex 方言では古英語 [æː] の発展形としての [aː] が従来行なわれていた関係で,前者が後者と同一視されるに至った.そこで,ロンドンの話者は Essex 方言と同一視されるのを嫌い,社会言語学的な距離 (sociolinguistic distancing) をとるべく,やや上げて [æː] と調音するようになったのだという.その後,この音は17世紀後半に改めて別の上げを経て [eː] へと変化していった.

上記は決して単純な説ではないが,逆に言えば,一見きれいに見える大母音推移も,社会音韻論的に複雑な過程を内包しているということを思い起こさせてくれる説である.

・ Smith, Jeremy J. An Historical Study of English: Function, Form and Change. London: Routledge, 1996.

2016-09-29 Thu

■ #2712. 初期中英語の個性的な綴り手たち [eme][me_dialect][manuscript][orthography][spelling][standardisation][scribe][ormulum][ab_language][spelling_reform]

英語の綴字標準化の歴史は,後期ウェストサクソン方言で標準的なものが現われるが,ノルマン征服後の初期中英語にはそれが無に帰し,後期中英語になって徐々に再標準化の兆しが芽生え,初期近代英語期中に標準化が進み,17--18世紀に標準綴字が確立した,と大雑把に要約できる.この概観によれば,初期中英語期は綴字の標準がまるでなかった時代ということになる.それはそれで間違ってはいないが,綴字標準とはいわずとも,ある程度一貫した綴字慣習ということであれば,この時代にも個人や小集団のレベルで実践されていた形跡が少数見つかる.よく知られているのは,(1) "AB language" の綴字, (2) Ormulum の作者 Orm の綴字,(3) ブリテン史 Brut をアングロ・フレンチ版から翻訳した Laȝamon の綴字である.

(1) "AB language" の名前は,修道女のための指南書 Ancrene Wisse を含む Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 402 という写本 (= A) と,関連する聖女伝や宗教論を含む Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 34 の写本 (=B) に由来する.この2写本(及び関連するいくつかの写本)には,かなり一貫した綴字体系が採用されており,しかも複数の写字生によってそれが用いられていることから,おそらく13世紀前半に,ある南西中部の修道院か写本室が中心となって,標準綴字を作り上げる試みがなされていたのだろうと推測されている.

(2) Orm は,Lincolnshire のアウグスティノ修道士で,1200年頃に,聖書を分かりやすく言い換えた書物 Ormulum を著わした.現存する唯一のテキストは2万行を超す韻文の大作であり,それが驚くほど一貫した綴字で書かれている.Orm は,母音の量にしたがって後続する子音を重ねるなどの合理性を追究した独特な綴字体系を編みだし,それを自分の作品で実践したのである.この Orm の綴字は,他の写本にも類するものが発見されておらず,きわめて個人的な綴字標準化の事例だが,これは後の16世紀の個性的な綴字改革論者の先駆けといってよい.

(3) Laȝamon は,Worcestershire の司祭で,13世紀初頭に韻文の年代記を韻文で英語へ翻訳した.当時すでに古めかしくなっていたとおぼしき頭韻 (alliteration) や,古風な語彙・綴字を復活させ,ノスタルジックな雰囲気をかもすことに成功した.Laȝamon は,実際に古英語にあった綴字かどうかは別として,いかにも古英語風な綴字を意識的に用いた点で特異であり,これをある種の個人的な綴字標準化の試みとみることも可能だろう.

以上,Horobin (98--102) を参照して執筆した.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2016-06-07 Tue

■ #2598. 古ノルド語の影響力と伝播を探る研究において留意すべき中英語コーパスの抱える問題点 [old_norse][loan_word][me_dialect][representativeness][geography][lexical_diffusion][lexicology][methodology][laeme][corpus]

「#1917. numb」 ([2014-07-27-1]) の記事で,中英語における本来語 nimen と古ノルド語借用語 taken の競合について調査した Rynell の研究に触れた.一般に古ノルド語借用語が中英語期中いかにして英語諸方言に浸透していったかを論じる際には,時期の観点と地域方言の観点から考慮される.当然のことながら,言語項の浸透にはある程度の時間がかかるので,初期よりも後期のほうが浸透の度合いは顕著となるだろう.また,古ノルド語の影響は the Danelaw と呼ばれるイングランド北部・東部において最も強烈であり,イングランド南部・西部へは,その衝撃がいくぶん弱まりながら伝播していったと考えるのが自然である.

このように古ノルド語の言語的影響の強さについては,時期と地域方言の間に密接な相互関係があり,その分布は明確であるとされる.実際に「#818. イングランドに残る古ノルド語地名」 ([2011-07-24-1]) や「#1937. 連結形 -son による父称は古ノルド語由来」 ([2014-08-16-1]) に示した語の分布図は,きわめて明確な分布を示す.古英語本来語と古ノルド語借用語が競合するケースでは,一般に上記の分布が確認されることが多いようだ.Rynell (359) 曰く,"The Scn words so far dealt with have this in common that they prevail in the East Midlands, the North, and the North West Midlands, or in one or two of these districts, while their native synonyms hold the field in the South West Midlands and the South."

しかし,事情は一見するほど単純ではないことにも留意する必要がある.Rynell (359--60) は上の文に続けて,次のように但し書きを付け加えている.

This is obviously not tantamount to saying that the native words are wanting in the former parts of the country and, inversely, that the Scn words are all absent from the latter. Instead, the native words are by no means infrequent in the East Midlands, the North, and the North West Midlands, or at least in parts of these districts, and not a few Scn loan-words turn up in the South West Midlands and the South, particularly near the East Midland border in Essex, once the southernmost country of the Danelaw. Moreover, some Scn words seem to have been more generally accepted down there at a surprisingly early stage, in some cases even at the expense of their native equivalents.

加えて注意すべきは,現存する中英語テキストの分布が偏っている点である.言い方をかえれば,中英語コーパスが,時期と地域方言に関して代表性 (representativeness) を欠いているという問題だ.Rynell (358) によれば,

A survey of the entire material above collected, which suffers from the weakness that the texts from the North and the North (and Central) West Midlands are all comparatively late and those from the South West Midlands nearly all early, while the East Midland and Southern texts, particularly the former, represent various periods, shows that in a number of cases the Scn words do prevail in the East Midlands, the North, and the North (and sometimes Central) West Midlands and the South, exclusive of Chaucer's London . . . .

古ノルド語の言語的影響は,中英語の早い時期に北部・東部方言で,遅い時期には南部・西部方言で観察される,ということは概論として述べることはできるものの,それが中英語コーパスの時期・方言の分布と見事に一致している事実を見逃してはならない.つまり,上記の概論的分布は,たまたま現存するテキストの時間・空間的な分布と平行しているために,ことによると不当に強調されているかもしれないのだ.見えやすいものがますます見えやすくなり,見えにくいものが隠れたままにされる構造的な問題が,ここにある.

この問題は,古ノルド語の言語的影響にとどまらず,中英語期に北・東部から南・西部へ伝播した言語変化一般を観察する際にも関与する問題である (see 「#941. 中英語の言語変化はなぜ北から南へ伝播したのか」 ([2011-11-24-1]),「#1843. conservative radicalism」 ([2014-05-14-1])) .

関連して,初期中英語コーパス A Linguistic Atlas of Early Middle English (LAEME) の代表性について「#1262. The LAEME Corpus の代表性 (1)」 ([2012-10-10-1]),「#1263. The LAEME Corpus の代表性 (2)」 ([2012-10-11-1]) も参照.

・ Rynell, Alarik. The Rivalry of Scandinavian and Native Synonyms in Middle English Especially taken and nimen. Lund: Håkan Ohlssons, 1948.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow