2025-11-17 Mon

■ #6048. 大学ジャーゴン --- オタゴ大学の大学案内より [university_of_otago][slang][register][sociolinguistics][abbreviation]

オタゴ大学の図書館に,新入生のための案内のパンフレットがあり,ふと手に取ってみた.そのなかに,UNIVERSITY JARGON と題するコラムがあった.大学での修学の仕方を手短かに教える内容だ.

UNIVERSITY JARGON

Starting to research your study options and already feeling lost in the jargon? Here are some common terms you're likely to come across.

A DEGREE is the qualification you complete at university. This is your overall PROGRAMME. Your degree will have an abbreviation such as BA, BSc or BCom. That's code for Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Science, or Bachelor of Commerce, and so on.

Some PROGRAMMES, such as Health Sciences First Year (HSFY), will lead on to many other degrees.

The SUBJECT you specialise in within your degree is called your Major. When you start your first year at university, choose three or four subjects you'd like to try. One will become your major.

In many degrees you can choose to have a MINOR as well. This is a subject you have stuided at each level, but not in as much depth as your major.

Each subject has LEVELS (100, 200, 300). The first courses youtake are called 100-level papers or beginner papers.

Each subject is divided into PAPERS. They are like topics within each subject --- the building blocks of your degree. They have codes like HIST 104, PSYC 201 and MART 304. The papers you choose each year are your course of study.

When you pass each paper, you get POINTS towards your degree. Papers are generally worth 18 points and a three-year degree needs 360 points. This usually consists of 20 papers, an average of 7 papers per year.

A DOUBLE DEGREE is when you study two degrees at the same time. There are also options to combine two majors from different degrees in a single four-year degree. These COMBINED DEGREES include Arts and Business, Arts and Science, and Business Science.

かなり複雑な履修システムをコンパクトに解説している文章だと思うが,新入生にとって初見で理解するのは容易ではないだろう.読み手の私は大学のシステムを理解しているので,これだけで分かるのだが,実際には凝縮しすぎているように思われる.たとえば major と specialise という jargons の意味は,相互に規定されるものであるから,同じ文に共起することによって,一方でともに理解しやすくなるという事情もあるかもしれないが,他方でいずれもチンプンカンプンとなってしまう恐れがある.

この文章は,個々の jargon を新入生のために解説している文章として読むのが普通だろうが,実は新入生に jargon とは何かを教える文章となっているのではないかとも解釈でき,おもしろい.つまり,ここで新入生を意味不明な jargon の羅列にさらすことによって,大学という特有の世界に誘い,仲間意識を醸成しようとしているのだ,と.

jargon の役割は,その意味が一見して自明ではないところに存する.jargons の羅列やその語彙体系は,独特で魅惑的な世界をちらつかせ,そこに引き寄せられる者のみに入会を許可する社会言語学的な機能をもっている.

関連して「#2410. slang, cant, argot, jargon, antilanguage」 ([2015-12-02-1]) を参照.

2025-10-04 Sat

■ #6004. slang の役割について凝縮した読ませる文章で教えてくれる章 --- HEL in 100 Places より [100_places][helgrim][helkatsu][slang][dictionary][lexicology][lexicography]

目下,New Zealand に来ている.持参した書籍の1つが,本ブログでも最近たびたび取り上げている A History of the English Language in 100 Places である.

NZ 関係の記述としては「#5974. New Zealand English のメイキング」 ([2025-09-04-1]) で紹介した第52節があったが,意外なところにもう1節あった.それは第66節 "GISBORNE --- English slang (1894)" である.

Gisborne は NZ 北島東岸の港町である.この町で英語辞書編纂界の巨人 Eric Partridge (1894--1979) が生まれたという理由で,この節にて英語の slang の話しが展開されることになるのだ.Partridge の業績のなかでもとりわけ名高いのが,A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (1937) である.この初版以来,現在まで改版が続いている影響力のある英語俗語辞書だ.

1ページ半ほどの短い節だが,ここに slang の捉えどころのなさ,怪しさ,魅力が詰め込まれている.slang の役割についての記述も,さりげなくではありながらも本質を突いている.ここでは最後の1節を引こう.

The aim of people using and creating slang is to make up words that are not in the dictionary in order to shock, delight, amaze, intrigue and mystify. Friends and enemies alike can be the objects of this verbal gaming, but slang users have to contend with the online glossaries that are being constantly updated. The best of these is Urban Dictionary; it boasts over 6 million definitions. Hard copy slang dictionaries are far behind; the Oxford Dictionary of Slang (2003) can boast no more than 10,000 slang words and phrases. Moreover, as a word moves from speech to print and from print to dictionary, its slanginess must steadily decrease.

今後,英語の slang 辞書編纂は,一般の辞書編纂に比べても,はるかに早く紙から遠ざかっていくだろうことが確信される.紙の辞書に捕捉された時点で,slang はその本質的な性質を半ば失っているということになるからだ.語彙変化や意味変化の領域における slang の影響力は思いのほか大きい.slang は言語変化の現場である.

・ Lucas, Bill and Christopher Mulvey. A History of the English Language in 100 Places. London: Robert Hale, 2013.

2024-10-01 Tue

■ #5636. 9月下旬,Mond で10件の疑問に回答しました [mond][sobokunagimon][hel_education][notice][link][helkatsu][adjective][slang][derivation][demonym][perfect][grammaticalisation][h][word_order][syntax][final_e][subjectification][intersubjectification][personal_pronoun][gender]

10月が始まりました.大学の新学期も開始しましたので,改めて「hel活」 (helkatsu) に精を出していきたいと思います.9月下旬には,知識共有サービス Mond にて10件の英語に関する質問に回答してきました.今回は,英語史に関する素朴な疑問 (sobokunagimon) にとどまらず進学相談なども寄せられました.新しいものから遡ってリンクを張り,回答の要約も付します.

(1) なぜ英語にはポジティブな形容詞は多いのにネガティヴな形容詞が少ないの?

回答:英語にはポジティヴな形容詞もネガティヴな形容詞も豊富にありますが,教育的配慮や社会的な要因により,一般的な英語学習ではポジティヴな形容詞に触れる機会が多くなる傾向がありそうです.実際の言語使用,特にスラングや口語表現では,ネガティヴな形容詞も数多く存在します.

(2) 地名と形容詞の関係について,Germany → German のように語尾を削る物がありますが?

回答:国名,民族名,言語名などの関係は複雑で,どちらが基体でどちらが派生語かは場合によって異なります.歴史的な変化や自称・他称の違いなども影響し,一般的な傾向を指摘するのは困難です.

(3) 現在完了の I have been to に対応する現在形 *I am to がないのはなぜ?

回答:have been to は18世紀に登場した比較的新しい表現で,対応する現在形は元々存在しませんでした.be 動詞の状態性と前置詞 to の動作性の不一致も理由の一つです.「現在完了」自体は文法化を通じて発展してきました.

(4) 読まない語頭以外の h についての研究史は?

回答:語中・語末の h の歴史的変遷,2重字の第2要素としてのhの役割,<wh> に対応する方言の発音,現代英語における /h/ の分布拡大など,様々な観点から研究が進められています.h の不安定さが英語の発音や綴字の発展に寄与してきた点に注目です.

(5) 言語による情報配置順序の特徴と変化について

回答:言語によって言語要素の配置順序に特有の傾向があり,これは語順,形態構造,音韻構造など様々な側面に現われます.ただし,これらの特徴は絶対的なものではなく,歴史的に変化することもあります.例えば英語やゲルマン語の基本語順は SOV から SVO へと長い時間をかけて変化してきました.

(6) なぜ come や some には "magic e" のルールが適用されないの?

回答:come,some などの単語は,"magic e" のルールとは無関係の歴史を歩んできました.これらの単語の綴字は,縦棒を減らして読みやすくするための便法から生まれたものです.英語の綴字には多数のルールが存在し,"magic e" はそのうちの1つに過ぎません.

(7) Let's にみられる us → s の省略の類例はある? また,意味が変化した理由は?

回答:us の省略形としての -'s の類例としては,shall's (shall us の約まったもの)がありました.let's は形式的には us の弱化から生まれましたが,機能的には「許可の依頼」から「勧誘」へと発展し,さらに「なだめて促す」機能を獲得しました.これは言語の主観化,間主観化の例といえます.

(8) 英語にも日本語の「拙~」のような1人称をぼかす表現はある?

回答:英語にも謙譲表現はありますが,日本語ほど体系的ではありません.例えば in my humble opinion や my modest prediction などの表現,その他の許可を求める表現,著者を指示する the present author などの表現があります.しかし,これらは特定の語句や慣用表現にとどまり,日本語のような体系的な待遇表現システムは存在しません.

(9) 英語史研究者を目指す大学4年生からの相談

回答:大学卒業後に社会経験を積んでから大学院に進学するキャリアパスは珍しくありません.教育現場での経験は研究にユニークな視点をもたらす可能性があります.研究者になれるかどうかの不安は多くの人が抱くものですが,最も重要なのは持続する関心と探究心,すなわち情熱です.研究会やセミナーへの参加を続け,学びのモチベーションを保ってください.

(10) 英語の人称代名詞における性別区分の理由と新しい代名詞の可能性は?

回答:1人称・2人称代名詞は会話の現場で性別が判断できるため共性的ですが,3人称単数代名詞は会話の現場にいない人を指すため,明示的に性別情報が付されていると便利です.現代では性の多様性への認識から,新しい共性の3人称単数代名詞が提案されていますが,広く受け入れられているのは singular they です.今後も要注目の話題です.

以上です.10月も Mond より,英語(史)に関する素朴な疑問をお寄せください.

2021-09-16 Thu

■ #4525. 「性交」を表わす語を上から下まで [taboo][euphemism][swearing][slang][thesaurus]

古今東西の言語で,性に関する語句はタブー (taboo) となりやすく,様々な婉曲表現 (euphemism) が発達するのが通例である.英語でも「性交」を意味する語句は枚挙にいとまがない.公的に用いても問題ない「上」の語句から,俗語 (slang) として日陰でしか使われない「下」の語句まで,実に幅広い.Hughes (242) がその氷山の一角として,次のように挙げている.

reproduction

generation

copulation

coition

intercourse

congress

intimacy

carnal knowledge

coupling

pairing

mating

at roughly which point the line is drawn, below which are found:

shagging

banging

bonking

fucking

上下を2分するおよその線が下から5行目に引かれているが,本当は下のクラスに属する語句の方が圧倒的に多い.書き切れないし書くのも憚られるものが多いので,あえて省略しているということだろう.憚られるものをいくつか小声で紹介すれば beast with two backs, bum dancing, bottom wetting, a squirt and a squeeze など.この目的で俗語辞典をめくってみれば,数百件はくだらない(大多数が下のクラス).

上下を分ける線の位置については,そもそも絶対的に定めることはできない.判断は個人によっても異なるし,時代によっても変化してきた.おそらく世代間でも線引きの仕方や認識はいくらか異なるだろう.調べてみれば,興味深い通時的研究になりそうだ.

・ Hughes, Geoffrey. Swearing: A Social History of Foul Language, Oaths and Profanity in English. London: Penguin, 1998.

2021-07-22 Thu

■ #4469. God に対する数々の歴史的婉曲表現 [taboo][euphemism][swearing][slang][metonymy][htoed]

英語の歴史において,God (神)はタブー性 (taboo) の強い語であり概念である.「#4457. 英語の罵り言葉の潮流」 ([2021-07-10-1]) でみたように,現代のタブー性の中心は宗教的というよりもむしろ性的あるいは人種的なものとなっているが,「神」周りのタブーは常に存在してきた.これほど根深く強烈なタブーであるから,その分だけ対応する婉曲表現 (euphemism) も豊富に開発されてきた.Hughes (13) が時系列に多数の婉曲表現を並べているので,再現してみよう.

| Term | Date | Euphemism |

|---|---|---|

| God | 1350s | gog |

| 1386 | cokk | |

| 1569 | cod | |

| 1570 | Jove | |

| 1598 | 'sblood | |

| 1598 | 'slid (God's eyelid) | |

| 1598 | 'slight | |

| 1599 | 'snails (God's nails) | |

| 1600 | zounds (God's wounds) | |

| 1601 | 'sbody | |

| 1602 | sfoot (God's foot) | |

| 1602 | gods bodykins | |

| 1611 | gad | |

| 1621 | odsbobs | |

| 1650s | gadzooks (God's hooks) | |

| 1672 | godsookers | |

| 1673 | egad | |

| 1695 | od | |

| 1695 | odso | |

| 1706 | ounds | |

| 1709 | odsbodikins (God's little body) | |

| 1728 | agad | |

| 1733 | ecod | |

| 1734 | goles | |

| 1743 | gosh | |

| 1743 | golly | |

| 1749 | odrabbit it | |

| 1760s | gracious | |

| 1820s | ye gods! | |

| 1842 | by George | |

| 1842 | s'elpe me Bob | |

| 1844 | Drat! (God rot!) | |

| 1851 | Doggone (God-damn) | |

| 1884 | Great Scott | |

| 1900 | Good grief | |

| 1909 | by Godfrey! |

「#469. euphemism の作り方」 ([2010-08-09-1]) でみたように,様々な方法で God の婉曲表現が作られてきたことが分かる.中世から初期近代に至るまでは,「神」それ自身ではなく,体の部位を指して間接的に指示するメトニミー (metonymy) によるものが目立つ.一方,近現代には音韻的変形に訴えかけるものが多い. rhyming slang による1884年の Great Scott もある(cf. 「#1459. Cockney rhyming slang」 ([2013-04-25-1])).HTOED などを探れば,まだまだ例が挙がってくるものと思われる.

「#1338. タブーの逆説」 ([2012-12-25-1]) でも述べたように「タブーは,毒々しければ毒々しいほど,むしろ長く生き続けるのである」.最近の関連記事としては「#4399. 間投詞 My word!」 ([2021-05-13-1]) もどうぞ.

・ Hughes, Geoffrey. Swearing: A Social History of Foul Language, Oaths and Profanity in English. London: Penguin, 1998.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2021-07-10 Sat

■ #4457. 英語の罵り言葉の潮流 [swearing][slang][asseveration][lexicology][semantic_change][taboo][euphemism][pc][sociolinguistics][pragmatics]

英語史における罵り言葉 (swearing) を取り上げた著名な研究に Hughes がある.英語の罵り言葉も,他の言葉遣いと異ならず,各時代の社会や思想を反映しつつ変化してきたこと,つまり流行の一種であることが鮮やかに描かれている.終章の冒頭に,Swift からの印象的な2つの引用が挙げられている (236) .

For, now-a-days, Men change their Oaths,

As often as they change their Cloaths.

Swift

Oaths are the Children of Fashion.

Swift

英語の罵り言葉の歴史には,いくつかの大きな潮流が観察される.Hughes (237--40) に依拠して,何点か指摘しておきたい.およそ中世から近現代にかけての変化ととらえてよい.

(1) 「神(の○○)にかけて」のような by や to などの前置詞を用いた誓言 (asseveration) は減少してきた.

(2) 罵り言葉のタイプについて,宗教的なものから性的・身体的なものへの交代がみられる.

(3) C. S. Lewis が "the moralisation of status word" と指摘したように,階級を表わす語が道徳的な意味合いを帯びる過程が観察される.例えば churl, knave, cad, blackguard, guttersnipe, varlet などはもともと階級や身分の名前だったが,道徳的な「悪さ」を含意するようになり,罵り言葉化してきた.

(4) 「労働倫理」と関連して,vagabond, beggar, tramp, bum, skiver などが罵り言葉化した.この傾向は,浮浪者問題を抱えていたエリザベス朝に特徴的にみられた.

(5) 罵り言葉と密接な関係をもつタブー (taboo) について,近年,性的なタイプから人種的なタイプへの交代がみられる.

英語の罵り言葉の潮流を追いかける研究は「英語歴史社会語彙論」の領域というべきだが,そこには実に様々な論題が含まれている.例えば,上記にある通り,タブーやそれと関連する婉曲語法 (euphemism) の発展との関連が知りたくなってくる.また,典型的な語義変化のタイプといわれる良化 (amelioration) や悪化 (pejoration) の問題にも密接に関係するだろう.さらに,近年の political correctness (= pc) 語法との関連も気になるところだ.slang の歴史とも重なり,社会言語学的および語用論的な考察の対象にもなる.改めて懐の深い領域だと思う.

・ Hughes, Geoffrey. Swearing: A Social History of Foul Language, Oaths and Profanity in English. London: Penguin, 1998.

2021-05-30 Sun

■ #4416. トイレの英語文化史 --- 英語史語彙論研究入門 [taboo][euphemism][khelf_hel_intro_2021][thesaurus][dictionary][lexicology][htoed][semantics][synonym][slang][hel_education][bibliography][link]

4月5日より始まっていた「英語史導入企画2021」のコンテンツ紹介記事は,今回で最終回となります.話題は「office, john, House of Lords --- トイレの呼び方」です.トリを飾るに相応しいテーマですね! トイレの英語文化史あるいは英語文化誌というべき内容で,Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary (= HTOED) を用いてこんなにおもしろい調査ができるのかと教えてくれるコンテンツです.コンテンツ内の図と点線を追っていくだけで,トイレの悠久の旅を楽しむことができます.

タブー (taboo),婉曲表現 (euphemism),類義語 (synonym) といった語彙論 (lexicology) 上の問題は,英語史の卒業論文研究などでも人気のテーマです.英語史語彙論研究に関心をもったら,これらのタグの付いた hellog の記事群を読んでみてください.また,以下に今回のコンテンツと緩く関連した記事も紹介しておきます.

・ 「#470. toilet の豊富な婉曲表現」 ([2010-08-10-1])

・ 「#471. toilet の豊富な婉曲表現を WordNet と Visuwords でみる」 ([2010-08-11-1])

・ 「#992. 強意語と「限界効用逓減の法則」」 ([2012-01-14-1])

・ 「#1219. 強意語はなぜ種類が豊富か」 ([2012-08-28-1])

・ 「#3885. 『英語教育』の連載第10回「なぜ英語には類義語が多いのか」」 ([2019-12-16-1])

・ 「#3392. 同義語と類義語」 ([2018-08-10-1])

・ 「#469. euphemism の作り方」 ([2010-08-09-1])

・ 「#4395. 英語の類義語について調べたいと思ったら」 ([2021-05-09-1])

・ 「#3159. HTOED」 ([2017-12-20-1])

・ 「#847. Oxford Learner's Thesaurus」 ([2011-08-22-1])

・ 「#4334. 婉曲語法 (euphemism) についての書誌」 ([2021-03-09-1])

・ 「#1270. 類義語ネットワークの可視化ツールと類義語辞書」 ([2012-10-18-1])

・ 「#1432. もう1つの類義語ネットワーク「instaGrok」と連想語列挙ツール」 ([2013-03-29-1])

・ 「#4092. shit, ordure, excrement --- 語彙の3層構造の最強例」 ([2020-07-10-1])

・ 「#4041. 「言語におけるタブー」の記事セット」 ([2020-05-20-1])

2021-05-29 Sat

■ #4415. as mad as a hatter --- 強意的・俚諺的直喩の言葉遊び [alliteration][rhyme][metaphor][cockney][slang][word_play][eebo][clmet][khelf_hel_intro_2021]

「英語史導入企画2021」より本日紹介するコンテンツは,院生による「発狂する帽子屋 as mad as a hatter の謎」です.なぜ帽子屋なのでしょうか.文化と言語の歴史をたどった好コンテンツです.

コンテンツ内でも触れられている通り,同種の表現としては /m/ で頭韻を踏む as mad as a March hare のほうが古いようです.この種の表現は俚諺的直喩 (proverbial simile) や強意的直喩 (intensifying simile) と呼ばれます.「#943. 頭韻の歴史と役割」 ([2011-11-26-1]) で取り上げたように,特に頭韻を踏む as cool as a cucumber, as dead as a door-nail, as bold as brass の類いがよく知られています.ただし,今回の as mad as a hatter のように頭韻を踏まないものもあります.韻律上の口調に基づいていなくとも,何らかの「故事」(今回のケースでは帽子屋と水銀の関係)に由来するなど,結果としてユーモラスな文彩を放つ喩えであれば,広く受け入れられるものかもしれません.

それでも今回のコンテンツで EEBO から引き出された類義表現を眺めているうちに,やはり多くの表現に何かしら韻律上の要因が関与しているのではないかと思いつきました.あくまで speculation にすぎませんが,述べてみたいと思います.

as mad as a March hare は初期近代英語に初出した比較的古い表現で,頭韻を踏んでいます.それと対比して,19世紀前半に現われた as mad as a hatter は頭韻を踏んでいません.しかし,hare と hatter は /h/ で頭韻を踏んでいます.古い表現が広く知られて陳腐になると,新しい表現が作られることになりますが,そのような場合,よく知られた古い表現に何らかの形で「引っかける」ことも少なくないのではないかと思いました.この場合には,hare の /h/ と引っかけて hatter を採用したのではないかと疑われます(もちろん帽子屋と水銀の故事は前提としつつ).as mad as a March hare のような通常の頭韻を "syntagmatic alliteration" と呼ぶのであれば,hare と hatter のような関係の頭韻は "paradigmatic alliteration" と呼べるかもしれません.いわば「裏」の韻律的引っかかりのことですね.

そうすると,as mad as a hart なども,hare との "paradigmatic alliteration" からインスピレーションを得た表現かもしれないということになります.また,as mad as a bear という表現もあったようですが,これなどは hare と脚韻で引っかかっているので "paradigmatic rhyme" の例と呼べるかもしれません.ベースとなる表現がしっかり定着していればいるほど,それをもじって新しい表現を作り出すこともしやすくなるのではないでしょうか.後期近代英語のコーパス CLMET3.0 からは mad as a herring や as mad as Marshal Stair といったユーモラスな例が見つかりましたが,同種のもじりとみたいところです.

俚諺的直喩も一種の言葉遊びですし,「裏」の韻律的引っかかりが関与しているのではないかと考えてみた次第です.関連して「#1459. Cockney rhyming slang」 ([2013-04-25-1]) のことが思い浮かびました.

2021-03-09 Tue

■ #4334. 婉曲語法 (euphemism) についての書誌 [euphemism][bibliography][semantics][lexicology][taboo][slang][swearing][sociolinguistics][thesaurus][terminology][hel_education]

英語の語彙や意味の問題として,婉曲語法 (euphemism) は学生にも常に人気のあるテーマである.隣接領域として taboo, swearing, slang のテーマとも関わり,社会言語学寄りの語彙の問題として広く興味を引くもののようだ.

そもそも euphemism とは何か.まずは Cruse の用語辞典より解説を与えよう (57--58) .

euphemism An expression that refers to something that people hesitate to mention lest it cause offence, but which lessens the offensiveness by referring indirectly in some way. The most common topics for which we use euphemisms are sexual activity and sex organs, and bodily functions such as defecation and urination, but euphemisms can also be found in reference to death, aspects of religion and money. The main strategies of indirectness are metonymy, generalisation, metaphor and phonological deformation.

Sex:

intercourse go to bed with (metonymy), do it (generalisation)

penis His member was clearly visible (generalisation)

Bodily function:

defecate go to the toilet (metonymy), use the toilet (generalisation)

Death:

die pass away (metaphor), He's no longer with us (generalisation)

Religion:

God gosh, golly (phonological deformation)

Jesus gee whiz (phonological deformation)

Hell heck (phonological deformation)

この種の問題に関心をもったら,まずは本ブログより「#469. euphemism の作り方」 ([2010-08-09-1]),「#470. toilet の豊富な婉曲表現」 ([2010-08-10-1]),「#992. 強意語と「限界効用逓減の法則」」 ([2012-01-14-1]) を始めとして (euphemism) の記事群,それから taboo の記事群にも広く目を通してもらいたい.

その後,以下の概説書の該当部分に当たるとよい.

・ Williams, Joseph M. Origins of the English Language: A Social and Linguistic History. New York: Free P, 1975. pp. 198--203.

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000. pp. 43--49.

・ Brinton, Laurel J. and Leslie K. Arnovick. The English Language: A Linguistic History. Oxford: OUP, 2006. pp. 80--81.

書籍レベルとしては,Bussmann (157) と McArthur (387) の参考文献リストより,以下を掲げる.

・ Allan, K. and K. Burridge. Euphemism and Dysphemism: Language Used as a Shield and Weapon. New York: OUP, 1991.

・ Ayto, J. Euphemisms: Over 3,000 Ways to Avoid Being Rude or Giving Offence. London: 1993.

・ Enright, D. J., ed. Fair of Speech: The Uses of Euphemism. Oxford: OUP, 1985.

・ Holder, R. W. A Dictionary of American and British Euphemisms: The Language of Evasion, Hypocrisy, Prudery and Deceit. Rev. ed. London: 1989. Bath: Bath UP, 1985.

・ Lawrence, J. Unmentionable and Other Euphemisms. London: 1973.

・ Rawson, Hugh. A Dictionary of Euphemisms & Other Doubletalk. New York: Crown, 1981.

具体的な語の調査にあたっては,もちろん OED,各種の類義語辞典 (thesaurus),Room の語の意味変化の辞典などをおおいに活用してもらいたい.

・ Cruse, Alan. A Glossary of Semantics and Pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2006.

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

・ Room, Adrian, ed. NTC's Dictionary of Changes in Meanings. Lincolnwood: NTC, 1991.

2020-10-26 Mon

■ #4200. Hoosier --- インディアナ州民のニックネーム [onomastics][personal_name][ame][slang][etymology][oed][etymology][pc][coha]

本年度の後期もオンライン授業が続いているが,先月のゼミ合宿で行なった即興英語史コンテンツ作成のイベント(cf. 「#4162. taboo --- 南太平洋発,人類史上最強のパスワード」 ([2020-09-18-1]))が苦しくも楽しかったので,学生と一緒にもう一度やってみた.その場で英単語を1つランダムに割り当てられ,それについて OED を用いて90分間で「何か」を書くという苦行.今回は,標題の未知の単語を振られ,見た瞬間に茫然自失.死にものぐるいの90分だった.その成果を,こちらに掲載.

古今東西,ある国や地域の住民に軽蔑(ときに愛情)をこめたニックネームを付けるということは,広く行なわれてきた.とりわけ付き合いの多い近隣の者たちが,茶化して名前を付けるケースが多い.しかし,たとえ当初は侮蔑的なニュアンスを伴うネーミングだったとしても,言われた側も反骨と寛容とユーモアの精神でそれを受け入れ,自他ともに用いる呼称として定着することも少なくない.

最も有名なのはアメリカ人を指す Yankee だろう.語源は諸説あるが,John に相当するオランダ語に指小辞を付した Janke が起源ではではないかといわれている.ニューヨーク(かつてオランダ植民地で「ニューアムステルダム」と称された)のオランダ移民たちが,コネチカットのイギリス移民を「ジョン坊主」と呼んで嘲ったことにちなむという説だ.

Yankee ほど有名でもなく,由来もはっきりしない類例の1つとして,米国インディアナ州の住民につけられたニックネームがある.標題の Hoosier だ.OED によると,Hoosier, n. /huːʒiə/ と見出しが立てられており,(予想される通り)アメリカ英語で使用される名詞である.語義が2つみつかる.いくつかの例文とともに示そう.

1. A nickname for: a native or inhabitant of the state of Indiana.

・ 1826 in Chicago Tribune (1949) 2 June 20/3 The Indiana hoosiers that came out last fall is settled from 2 to 4 milds of us.

・ 1834 Knickerbocker 3 441 They smiled at my inquiry, and said it was among the 'hoosiers' of Indiana.

・ . . . .

2. An inexperienced, awkward, or unsophisticated person.

・ 1846 J. Gregg Diary 22 Aug. (1941) I. 212 Old King is one of the most perfect samples of a Hoosier Texan I have met with. Fat, chubby, ignorant, and loquacious as Sancho Panza..we could believe nothing he said.

・ 1857 E. L. Godkin in R. Ogden Life & Lett. E. L. Godkin (1907) I. 157 The mere 'cracker' or 'hoosier', as the poor [southern] whites are termed.

・ . . . .

第1語義は「インディアナ州の住民」,第2語義は「世間知らずの垢抜けない田舎者」ほどである.上述の通り,軽蔑の色彩のこもった小馬鹿にするような呼称であることが感じられるだろう.初出は19世紀の前半とみられる.

語源に関しては OED に "Origin unknown" (語源不詳)とあり,残念な限りなのだが,ここで諦めるわけにはいかない.米国のことであれば,OED よりも情報量の豊富なはずの,百科辞典的な特色を備える The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language に頼ればよい.早速当たってみると,しめしめ,1つの説が紹介されていた.その概要を解説しよう.

語源は闇に包まれているが,イングランドのカンバーランド方言で19世紀に「とてつもなく大きいもの」を意味する hoozer という訛語が文証される.これが変形した形で米国に持ち込まれたのが Hoosier ではないかという説だ.一方,後者の初出年である1826年よりも後のことではあるが,Dictionary of Americanisms には "a big, burly, uncouth specimen or individual; a frontiersman, countryman, rustic",要するに「田舎者の大男」の語義で現われていることが確認され,OED の第2語義にぴったり通じる.

実際,19世紀前半は Hoosier を含め米国各州の住民に次々と侮蔑的なニックネームがつけられた時代である.インディアナ州についても,おそらく近隣州の住民などが名付けの奇想を練っていたのだろう.詳しいルートこそ分からないが,そこへ Hoosier (田舎者の大男)がスルッと入り込んだようだ.テキサス州民の Beetheads (ビート頭),アラバマ州民の Lizards (トカゲ),ネブラスカ州民の Bugeaters (虫食い野郎),そしてミズーリ州民の Pukes (へど)などの名(迷)悪言が生まれたが,これらに比べれば Hoosier はひどい方ではない.

昨今は PC (= political correctness) の時代である.特定の国であれ地域であれ,そこの住民を侮蔑的なニュアンスを帯びた名前で呼ぶ慣習は,下火になりつつある.地域のスポーツチームのニックネームとして,ノースカロライナ州の Tarheels (ヤニの踵)やオハイオ州の Buckeyes (トチノキ)などに残る以外には用いられなくなってきている.

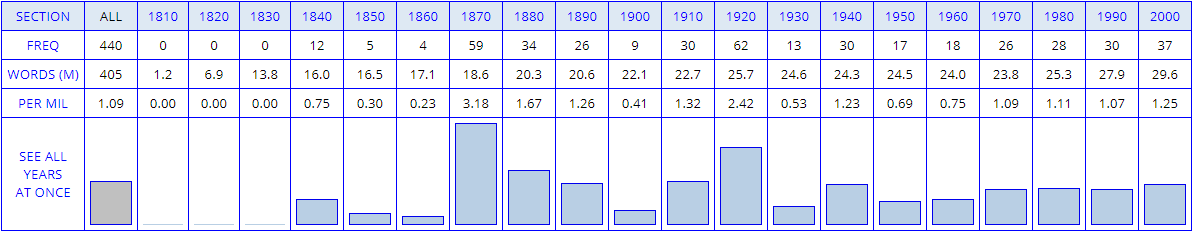

試しに Corpus of Historical American English により "[Hoosier]" として検索してみると,1870年代から1920年代にかけて浮き沈みはありつつも相対的に多く用いられていたようだが,20世紀後半にかけては低調である.

ただし,国民・地域住民への侮蔑的なあだ名が忌避されるようになってきているとはいえ,「公には」という限定つきである.実際には,そこいらの街角で,日々のおしゃべりのなかで,からかいの言葉は使われ続けるものである.憎まれっ子が世にはばかるように,憎まれ語も実はアンダーグラウンドで世にはばかっているのである.

・ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. 4th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006.

・ Corpus of Historical American English. Available online at https://www.english-corpora.org/coha/. Accessed 20 October 2020.

・ The Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020. Available online at http://www.oed.com/. Accessed 20 October 2020.

2020-10-08 Thu

■ #4182. 「言語と性」のテーマの広さ [sociolinguistics][hellog_entry_set][political_correctness][personal_pronoun][gender][gender_difference][taboo][slang][personification]

いよいよ始まった今学期の社会言語学の授業では「言語と性」という抜き差しならぬテーマを扱う.このテーマから連想される話題は多岐にわたる.あまりに広い範囲を覆っているために,一望するのが困難なほどである.実際に,授業の履修生に連想される話題を箇条書きで挙げてもらったところ,のべ1,000件を優に超える話題が集まった.重複するものも多く,整理すればぐんと減るとは思われるが,それにしても凄い数だ(←皆さん,協力ありがとう).その一部を覗いてみよう.

・ (英語を除く)主要な印欧諸語にみられる文法性 (grammatical gender)

・ 代名詞にみられる性差

・ 職業名や称号を巡るポリティカル・コレクトネス (political_correctness)

・ LGBTQ と言語

・ 擬人化された名詞の性

・ 人名における性

・ 「男言葉」と「女言葉」

・ 性に関するスラングやタブー語

・ 性別によるコミュニケーションの取り方の違い

・ イントネーションの性差

そもそも,古今東西すべての言語で,「男」 (man) と「女」 (woman) という2つの単語が区別されて用いられている点からして,もう言語における性の話しは始まっているのである.最先端の関心事である LGBTQ やポリティカル・コレクトネスの問題に迫る以前に,すでに性は言語に深く刻まれている.

最先端の話題ということでいえば,10月2日の読売新聞朝刊で,JAL が乗客に対する「レディース・アンド・ジェントルメン」の呼びかけをやめ「オール・パッセンジャーズ」へ切り替える決定をしたとの記事を読んだ.人間の関心事としては最重要なものの1つとして認識される性,それが人間に特有の言語という体系に埋め込まれていないわけがないのである.

「言語と性」のテーマの広さを味わうところから議論を始めたいと思っている.こちらの hellog 記事セットをどうぞ.

2020-07-10 Fri

■ #4092. shit, ordure, excrement --- 語彙の3層構造の最強例 [lexicology][synonym][loan_word][borrowing][french][latin][lexical_stratification][swearing][taboo][slang][euphemism]

いかがでしょう.汚いですが,英語の3層構造を有便雄弁に物語る最強例の1つではないかと思っています.日本語の語感としては「クソ」「糞尿」「排泄物」ほどでしょうか.

英語語彙の3層構造については,本ブログでも「#3885. 『英語教育』の連載第10回「なぜ英語には類義語が多いのか」」 ([2019-12-16-1]) やそこに張ったリンク先の記事,また (lexical_stratification) などで,繰り返し論じてきました.具体的な例も「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]),「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1]) で挙げてきました.

もっと挙げてみよと言われてもなかなか難しく,典型的な ask, question, interrogate や help, aid, assistance などを挙げて済ませてしまうのですが,決して満足はしておらず,日々あっと言わせる魅力的な例を探し求めいました.そこで,ついに標題に出くわしたのです.Walker の swearing に関する記述を読んでいたときでした (32) .

A few taboo words describing body parts started out as the 'normal' forms in Old English; one of the markers of the status difference between Anglo-Norman and Old English is the way the 'English' version became unacceptable, while the 'French' version became the polite or scientific term. The Old English 'scitte' gave way to the Anglo-Norman 'ordure' and later the Latin-via-French 'excrement'.

これに出会ったときは,(鼻をつまんで)はっと息を呑み,目を輝かせてしまいました.

shit は古英語 scitte にさかのぼる本来語ですが,古英語での意味は「(家畜の)下痢」でした. 動詞としては接頭辞つきで bescītan (汚す)のように長母音を示していましたが,後に名詞からの影響もあって短化し,中英語期に s(c)hite(n) (糞をする)が現われています.名詞の「糞」の語義としては意外と新しく,初期近代英語期の初出です.

ordure は,古フランス語 ordure から中英語期に入ったもので,「汚物」「卑猥な言葉」「糞」を意味しました.語根は horrid (恐ろしい)とも共通します.

excrement は初期近代英語期にラテン語 excrēmentum (あるいは対応するフランス語 excrément)から借用されました.

現在では本来語の shit は俗語・タブー的な「匂い」をもち,その婉曲表現としては「匂い」が少し緩和されたフランス語 ordure が用いられます.ラテン語 excrement は,さらに形式張った学術的な響きをもちますが,ほとんど「匂い」ません.

以上,失礼しました.

・ Walker, Julian. Evolving English Explored. London: The British Library, 2010.

2019-06-22 Sat

■ #3708. 省略・短縮は形態上のみならず機能上の問題解決法である [abbreviation][shortening][slang]

授業でディスカッションなどをしていると,ときに学生から驚くような発想が飛び出し,感じ入ることがある.先日,造語法としての省略 (abbreviation) や短縮 (shortening) という話題を取り上げ,話者は何のために語を切り詰めたがるのだろうかということを議論した.

授業では,話者には頻用する表現を短く楽に発音したいといった実際的な欲求があり,省略・短縮という形態的手段を通じて,その欲求を満たすのだろうという議論をしようと思っていた.つまり,話者は純粋に形態的な簡便さを目指して言語行動を行なうことがしばしばある,ということを論じようと考えていた.

ところが,ある学生が思ってもみない方面からコメントをくれた.省略・短縮はそのような形態的な問題であるばかりではなく,それ自体が独自の機能をもっているのではないかというのだ.たとえば,「コンビニ」は「コンビニエンスストア」を簡単に短く言うために作られた省略語であるという議論は確かに受け入れられるが,一方でそれが単なるコンビニエンスストア(=便利店)にとどまらず,独自の店舗形態と個性をもった「コンビニ」という固有の存在であることを明示するために,あえて「コンビニエンスストア」とは異なる形態,この場合には縮約された形態を取っているのではないかと.つまり,省略・短縮には機能的な役割があるという指摘だ.

確かに元の表現をベースにしながらも,それとは異なる表現を作り出すことは,機能的独立を目指す造語行為といえる.そのような造語法には借用,派生,合成,転換を含めて様々な形態的手段があり得るが,最も手近で実用的な方法の1つに省略・短縮があるだろう.発音も楽になるし,元の表現とは似ていながらも一応異なる形態になるという点では,省略・短縮は複合的なニーズを満たしてくれる語形成上の優等生といえそうだ.

俗語,隠語などの生成動機の問題にもつながる重要な視点である.素晴らしい.

2019-02-12 Tue

■ #3578. 黒人英語 (= AAVE) の言語的特徴 --- 語彙,語法,その他 [aave][variation][variety][slang][lexicon][ame]

「#3576. 黒人英語 (= AAVE) の言語的特徴 --- 発音」 ([2019-02-10-1]),「#3577. 黒人英語 (= AAVE) の言語的特徴 --- 文法」 ([2019-02-11-1]) に続き,McArthur より AAVE の言語的特徴を紹介する.今回は語彙,語法,その他について.

(1) goober (peanut), yam (sweet potato), tote (to carry), buckra (white man) などは西アフリカの語彙に遡る.

(2) 内集団で homeboy / homegirl (自分の近所出身の囚人),homies (homegirls) などが用いられる.

(3) ある集団を軽蔑して呼ぶ名称として honkie / whitey (白人),redneck / peckerwood (田舎の貧しい(南部の)白人)などが用いられる.

(4) 俗語として bad / cool / hot (良い),crib (家,住居),short / ride (車)などが用いられる.

(5) 日常的な語法として,stepped-to ((喧嘩で)有利な),upside the head (頭のところで(殴られる)),ashy ((皮膚が)脱色して)などが用いられる.

(6) 多くの AAVE 表現が,アメリカ英語の口語にも拡がっている.hip / hep (ポピュラーカルチャーに通じている人),dude (男)

(7) アフリカの口頭伝統に由来する様々な表現が,やはりアメリカ英語の口語に拡がっている.the dozens (相手の母親に対する侮辱発言),rapping (雄弁で巧みな言葉遣い),shucking / jiving (白人を言葉巧みにからかったり,だましたりすること),sounding (言葉による対決)など.

とりわけ語彙や表現の領域で顕著なのは,上にも述べたように,一般のアメリカ英語の口語・俗語にも多く入り込んでいることだ.アメリカ英語を論じる上で(ということは,ある程度は標準英語を論じる上でも),AAVE は無視できないくらいの存在感をもっているのである.とりわけ AAVE のポップカルチャーの言語への影響力は大きい.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

2018-10-18 Thu

■ #3461. 警官 bobby [prime_minister][etymology][personal_name][eponym][slang][history]

昨日の記事「#3460. 紅茶ブランド Earl Grey」 ([2018-10-17-1]) で,イギリス首相に由来する(といわれる)紅茶の名前について触れた.同じくイギリス首相に由来する,もう1つの表現を紹介しよう.イギリスで警官のことを俗語で bobby と呼ぶが,これは首都警察の編成に尽力した首相・内務大臣を歴任した Sir Robert Peel (1788--1850) の愛称,Bobby に由来するといわれる.

Peel は,19世紀前半,四半世紀にわたってイギリス政治を牽引した政界の重鎮である.初期の業績としては,Metropolitan Police Act を1828年に通過させ,翌1829年,首都警察を設置したことが挙げられる.その後,bobby が警官の意の俗語となっていった.いつ頃からの用法かは正確にはわからないが,OED の初例は1844年のものである.

1844 Sessions' Paper June 341 I heard her say..'a bobby'..it was a signal to let them know a policeman was coming.

首都警察の設置と同じ1829年には「カトリック教徒解放法案」も成立させており,著しい敏腕振りを発揮している.Peel は党利党略ではなく国家の利益を第一に考えた(この点では,昨日取り上げた Earl Grey も同じだった).Peel はもともと地主貴族階級の砦であった「穀物法」を切り崩すことを目論んでいたが,1845年のアイルランドのジャガイモ飢饉を機に,穀物法廃止に踏み切る決断を下した.そして,翌年に廃止を実現した.19世紀の大改革を次々と成し遂げた首相だった.

なお,同じく俗語の「警官」として実に peeler という単語もあるので付け加えておきたい.

2018-02-23 Fri

■ #3224. Thomas Harman, A Caveat or Warening for Common Cursetors (1567) [dictionary][slang][lexicology][lexicography][renaissance][register]

昨日の記事「#3223. George Andrews, A Dictionary of the Slang and Cant language (1809)」 ([2018-02-22-1]) で,英語史上初の俗語・隠語の用語集,Thomas Harman の A Caveat or Warening for Common Cursetors (1567) に言及した.英語史上初の英英辞書,Robert Cawdrey の A Table Alphabeticall に30年以上も先駆けて出版されたというのは驚くべきことに思われるかもしれない.普通の英英辞書よりも,裏世界の用語集のほうが早いというのは,何だかおもしろい.

しかし,ルネサンス期以前のイングランドにおける辞書編纂の経緯を振り返ってみると,むしろこの流れは自然である.まず,ある言語について最初に作られる辞書・用語集は,ほぼ間違いなく外国語辞書,つまり bilingual dictionaries/glossaries である.実際,羅英辞書,仏英辞書,伊英辞書などが英語史上,先に現われている.このことは,考えてみれば当然である.何といっても,理解できない言語の単語を母語の単語で教えてくれるのが,辞書の第1の役割である.すでによく知っている母語の単語を母語で言い換えたり説明したりする monolingual dictionaries/glossaries は,現代でこそ価値あるものと了解されているが,近代初期にあっては,いまだその意義は人々にピンとこなかったろう.

そして,外国語辞書に準ずるものとして,次に裏世界の俗語・隠語 (canting language) の用語集が編まれることになった.善良な一般市民にとって,canting language は外国語も同然である.したがって,A Caviat もある種の bilingual glossary だったと言ってよいのである.

続けて,1604年に英語史上初の「普通の英英辞書」と先ほど言及した A Table Alphabeticall が出版されたが,実際には「普通」の英単語を集めたものではなく,主としてラテン借用語などからなる「難語」を集めたものだった.これも見方によっては bilingual dictionary とも言えるものである.その後,17世紀を通じて英語に関する辞書がたくさん出版されたが,いずれも難語辞書であり,bilingual dictionaries の域を出てはいなかったとも考えられる(cf. 「#609. 難語辞書の17世紀」 ([2010-12-27-1])).

上記の経緯を勘案すると,いたずらぽい見方をして,英語史上初の英英辞書・用語集は A Caviat であると宣言することもできるかもしれないのだ.この点について,Blank (231) を引用したい.

In fact the original English-English dictionaries, long preceding those produced in the seventeenth century, were glossaries of the canting language. As Thomas Harman and his followers often noted, cant was otherwise known in the period as 'pedlar's French', a term which again reinforced notions of its 'foreign' nature. Harman's popular pamphlet A Caveat or Warening for Common Cursetors (1567) describes the underworld language as a 'leud, lousey language of these lewtering Luskes and lasy Lorrels . . . a vnknowen toung onely, but to these bold, beastly, bawdy Beggers, and vaine Vacabondes'. As a measure of social precaution, he included a glossary intended to expose the 'vnknowen toung', thereby translating the 'leud, lousey' language into 'common' English:

Nab, a pratling chete, quaromes, a head. a tounge. a body. Nabchet, Crashing chetes, prat, a hat or cap. teeth. a buttocke.

and so on through a list that includes 120 terms.

・ Blank, Paula. "The Babel of Renaissance English." Chapter 8 of The Oxford History of English. Ed. Lynda Mugglestone. Oxford: OUP, 2006. 212--39.

2018-02-22 Thu

■ #3223. George Andrews, A Dictionary of the Slang and Cant language (1809) [lexicology][lexicography][slang][register]

19世紀前半には数十の俗語辞書が編纂されたが,その目的の1つに,ハイカルチャーな語彙しか収録しなかった Johnson の辞書を補完するという狙いがあったろう.しかし,今回取り上げる George Andrews による A Dictionary of the Slang and Cant language (1809) には,もっと「啓蒙的」な役割があった.それは,泥棒の俗語・隠語を世に広く知らしめることにより,犯罪抑止を狙うというものだった.ある種の社会正義を目指した書といってよいかもしれない.Crystal (68) によると,この辞書の売り文句として,次のような宣伝が書かれていたという.

One great misfortune to which the Public are liable, is, that Thieves have a Language of their own; by which means they associate together in the streets, without fear of being over-heard or understood.

The principal end I had in view in publishing this DICTIONARY, was, to expose the Cant Terms of their Language, in order to the more easy detection of their crimes; and I flatter myself, by the perusal of this Work, the Public will become acquainted with their mysterious Phrases; and be better able to frustrate their designs.

Crystal (68) に再掲されている,いくつかの見出し語と定義を以下に挙げよう.19世紀初頭の泥棒の隠語だが,おそらく現在の泥棒には通じないのだろうなあ・・・.

| Adam Tylers | pickpockets' accomplices |

| badgers | hawkers |

| bullies, bully-huffs, bully-rooks | hired ruffians |

| bloods | roisterers |

| buffers | horse killers (for the skins) |

| beau-traps | well-dressed sharpers |

| cloak-twitchers | cloak-snatchers (from off people's shoulders) |

| clapperdogeons (also spelled clapperdudgeon) | beggars |

| coiners | counterfeiters |

| cadgers | beggars |

| duffers | hawkers |

| divers | pickpockets |

| dragsmen | vehicle thieves |

| filers | coin-filers |

| fencers | receivers of stolen goods |

| footpads | highwaymen who rob on foot |

| gammoners | pickpockets' accomplices |

| ginglers (also jinglers) | horse-dealers |

| kencrackers | housebreakers |

| knackers | tricksters |

| lully-priggers | linen-thieves |

| millers | housebreakers |

| priggers | thieves |

| rum-padders | highwaymen |

| strollers | pedlars |

| sweeteners | cheats, decoys |

| spicers | footpads |

| smashers | counterfeiters |

| swadlers (also swadders) | pedlars |

| whidlers (also whiddlers) | informers |

| water-pads | robbers of ships |

なお,英語史上の俗語・隠語辞書の走りは,1567年の Thomas Harman による用語集 A Caveat or Warening for Common Cursetors とされる.通常の英語辞書の嚆矢が Robert Cawdrey による1604年の「#603. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (1)」 ([2010-12-21-1]) であることを考えると,辞書編纂業においても暗黒世界は先進的(?)だったのかと感じ入る次第である.

slang, cant, argot, jargon などの用語については「#2410. slang, cant, argot, jargon, antilanguage」 ([2015-12-02-1]) を参照.また,隠語の性質については「#2166. argot (隠語)の他律性」 ([2015-04-02-1]),「#3076. 隠語,タブー,暗号」 ([2017-09-28-1]) もどうぞ.

・ Crystal, David. Evolving English: One Language, Many Voices. London: The British Library, 2010.

2015-12-02 Wed

■ #2410. slang, cant, argot, jargon, antilanguage [slang][register][terminology][variety][sociolinguistics]

標題の術語は,特殊な register (使用域,位相)に属する語句を表わす.互いに重なる部分が多いのだが,厳密な定義は難しい.まずは,Williams (203--04) による各用語についての説明を引用しよう.

Cant (related to chant, and originally the whining pleas of beggars) is often used to refer particularly to the language of thieves, gypsies, and such. But it has also been used to refer to the specialized language of any occupation, particularly to the mechanical and mindless repetition of special words and phrases.

Argot (a French word of unknown etymology), usually refers to the secret language of the underworld, though it too has also been used to refer to any specialized occupational vocabulary---the argot of the racetrack, for example. Jargon (once meaning the warbling of birds) is usually used by someone unfamiliar with a particular technical language to characterize his annoyed and puzzled response to it. Thus one man's technical vocabulary is another's jargon. Feature, shift, transfer, artifactual, narrowing, acronym, blend, clip, drift---all these words belong to the vocabulary of semantic change and word formation, the vocabulary of historical linguistics. But for anyone ignorant of the subject and unfamiliar with the terms, such words would make up its jargon. Thus cant, argot, and jargon are words that categorize both by classing and by judging.

Slang (of obscure origin) has many of the same associations. It has often been used as a word to condemn "bad" words that might pollute "good" English---even destroy the mind. . . . / But . . . slang is a technical terms like the terms grammatical and ungrammatical---a neutral term that categorizes a group of novel words and word meanings used in generally casual circumstances by a cohesive group, usually among its members, not necessarily to hide their meanings but to signal their group membership.

Trudgill の用語辞典にエントリーのある,slang, argot, jargon, antilanguage についても解説を引用する.

slang Vocabulary which is associated with very informal or colloquial styles, such as English batty (mad) or ace (excellent). Some items of slang, like ace, may be only temporarily fashionable, and thus come to be associated with particular age-groups in a society. Other slang words and phrases may stay in the language for generation. Formerly slang vocabulary can acquire more formal stylistic status, such as modern French tête (head) from Latin testa (pot) and English bus, originally an abbreviation of omnibus. Slang should not be confused with non-standard dialect. . . . Slang vocabulary in English has a number of different sources, including Angloromani, Shelta and Yiddish, together with devices such as rhyming slang and back slang as well as abbreviation (as in bus) and metaphor, such as hot meaning 'stolen' or 'attractive'.

argot /argou/ A term sometimes used to refer to the kinds of antilanguage whose slang vocabulary is typically associated with criminal groups.

jargon . . . . A non-technical term used of the register associated with a particular activity by outsiders who do not participate in this activity. The use of this term implies that one considers the vocabulary of the register in question to be unnecessarily difficult and obscure. The register of law may be referred to as 'legal jargon' by non-lawyers.

antilanguage A term coined by Michael Halliday to refer to a variety of a language, usually spoken on particular occasions by members of certain relatively powerless or marginal groups in a society, which is intended to be incomprehensible to other speakers of the language or otherwise to exclude them. Examples of groups employing forms of antilanguage include criminals. Exclusivity is maintained through the use of slang vocabulary, sometimes known as argot, not known to other groups, including vocabulary derived from other languages. European examples include the antilanguages Polari and Angloromany.

それぞれの用語の指す位相は,それぞれ重なり合いながらも,独自の要素をもっている.これは,各々が英語の歴史文化において区別される役割を担ってきたことの証左だろう.こうした用語使いそのものが英語の歴史性と社会性をもっており,したがって用語の翻訳は難しい.

・ Williams, Joseph M. Origins of the English Language: A Social and Linguistic History. New York: Free P, 1975.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2014-09-04 Thu

■ #1956. Hughes の英語史略年表 [timeline][lexicology][lexicography][register][slang][hel][historiography]

Hughes (xvii--viii) は,著書 A History of English Words で,語彙史と辞書史を念頭に置いた,外面史を重視した英語史年表を与えている.略年表ではあるが,とりわけ語彙史,辞書との関連が前面に押し出されている点で,著者の狙いが透けて見える年表である.

| 410 | Departure of the Roman legions |

| c.449 | The Invasion of the Angles, Saxons, Jutes and Frisians |

| 597 | The Coming of Christianity |

| 731 | Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People |

| 787 | The first recorded Scandinavian raids |

| 871--99 | Alfred King of Wessex |

| 900--1000 | Approximate date of Anglo-Saxon poetry collections |

| 1016--42 | Canute King of England, Scotland and Denmark |

| 1066 | The Norman Conquest |

| c.1150 | Earliest Middle English texts |

| 1204 | Loss of Calais |

| 1362 | English restored as language of Parliament and the law |

| 1370--1400 | The works of Chaucer, Langland and the Gawain poet |

| 1384 | Wycliffite translation of the Bible |

| 1476 | Caxton sets up his press at Westminster |

| 1525 | Tyndale's translation of the Bible |

| 1549 | The Book of Common Prayer |

| 1552 | Early canting dictionaries |

| 1584 | Roanoke settlement of America (abortive) |

| 1590--16610 | Shakespeare's main creative period |

| 1603 | Act of Union between England and Scotland |

| 1604 | Robert Cawdrey's Table Alphabeticall |

| 1607 | Jamestown settlement in America |

| 1609 | English settlement of Jamaica |

| 1611 | Authorized Version of the Bible |

| 1619 | First Arrival of slaves in America |

| 1620 | Arrival of Pilgrim fathers in America |

| 1623 | Shakespeare's First Folio published |

| 1649--60 | Puritan Commonwealth: closure of the theatres |

| 1660 | Restoration of the monarchy |

| 1667 | Milton's Paradise Lost |

| 1721 | Nathaniel Bailey's Universal Etymological English Dictionary |

| 1755 | Samuel Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language |

| 1762--94 | Grammars published by Lowth, Murray, etc. |

| 1765 | Beginning of the English Raj in India |

| 1776 | Declaration of American Independence |

| 1788 | Establishment of the first penal colony in Australia |

| 1828 | Noah Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language |

| 1884--1928 | Publication of the Oxford English Dictionary |

| 1903 | Daily Mirror published as the first tabloid |

| 1922 | Establishment of the BBC |

| 1947 | Independence of India |

| 1957--72 | Independence of various African, Asian and Caribbean states |

| 1961 | Third edition of Webster's Dictionary |

| 1968 | Abolition of the post of Lord Chancellor |

| 1989 | Second edition of the Oxford English Dictionary |

著書を読んだ後に振り返ると,著者の英語史記述に対する姿勢,英語史観がよくわかる.年表というのは1つの歴史観の表現であるなと,つくづく思う.これまで timeline の各記事で,英語史という同一対象に対して異なる年表を飽きもせずに掲げてきたのは,その作者の英語史観を探りたいがためだった.いろいろな年表を眺めてみてください.

・Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-08-27 Wed

■ #1948. Addison の clipping 批判 [clipping][shortening][slang][prescriptive_grammar][shortening][clipping][swift][genitive][clitic][complaint_tradition]

昨日の記事では「#1947. Swift の clipping 批判」([2014-08-26-1]) について見たが,Swift の同時代人である Joseph Addison (1672--1719) も,皮肉交じりにほぼ同じ言語論を繰り広げている.

Joseph Addison launched an attack on monosyllables in the Spectator (135, 4 August 1711):

The English Language . . . abound[s] in monosyllables, which gives an Opportunity of delivering our Thoughts in few Sounds. This indeed takes off from the Elegance of our Tongue, but at the same time expresses our Ideas in the readiest manner.

He observes that some past-tense forms --- e.g. drown'd, walk'd, arriv'd --- in which the -ed had formerly been pronounced as a separate syllable (as we still do in the adjectives blessed and aged) had become monosyllables. A similar situation is found in the case of drowns, walks, arrives, 'which in the Pronunciation of our Forefathers were drowneth, walketh, arriveth'. He objects to the genitive 's, which he incorrectly assumes to be a reduction of his and her, and for which he in any case gives no examples. He asserts that the contractions mayn't, can't, sha'n't, wo'n't have 'much untuned our Language, and clogged it with Consonants'. He dismisses abbreviations such as mob., rep., pos., incog. as ridiculous, and complains about the use of short nicknames such as Nick and Jack.

動詞の -ed 語尾に加えて -es 語尾の非音節化,所有格の 's,否定接辞 n't もやり玉に挙がっている.愛称 Nick や Jack にまで非難の矛先が及んでいるから,これはもはや正気の言語論といえるのかという問題になってくる.

Addison にとっては不幸なことに,ここで非難されている項目の多くは後に標準英語で確立されることになる.しかし,Addison にせよ Swift にせよ切株や単音節語化をどこまで本気で嫌っていたのかはわからない.むしろ,世にはびこる「英語の堕落」を防ぐべく,アカデミーを設立するための口実として,やり玉に挙げるのに単音節語化やその他の些細な項目を選んだということなのかもしれない.もしそうだとすると,言語上の問題ではあるものの,本質的な動機は政治的だったということになろう.規範主義的な言語論は,たいていあるところまでは理屈で押すが,あるところからその理屈は破綻する運命である.言語論は,論者当人が気づいているか否かは別として,より大きな目的のための手段として利用されることが多いように思われる (cf. 「#468. アメリカ語を作ろうとした Webster」 ([2010-08-08-1])) .

なお,所有格の 's が his の省略形であるという Addison の指摘については,英語史の立場からは興味深い.これに関して,「#819. his 属格」 ([2011-07-25-1]),「#1417. 群属格の発達」 ([2013-03-14-1]),「#1479. his 属格の衰退」 ([2013-05-15-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Knowles, Gerry. A Cultural History of the English Language. London: Arnold, 1997.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow