2016-12-07 Wed

■ #2781. 宗教改革と古英語研究 [reformation][emode][oe][history_of_linguistics][anglo-saxon]

イングランドにおいて本格的な古英語研究が始まったのは,近代に入ってからである.中英語期には,古英語への関心はほとんどなかったといってよい.では,なぜ近代というタイミングで,具体的には16世紀になってから,古英語が突如として研究すべき対象となったのだろうか.

16世紀は宗教改革の時代である.Henry VIII がローマ教会と絶縁し,自ら英国国教会を設立したのが,1534年.このとき改革派は,英国国教会とその教義の独自性および歴史的継続性を主張する必要があった.そこで持ち出されたのが,言語的伝統,すなわち英語の歴史であった.イングランドという国家と分かち難く結びつけられた英語という言語の伝統が,長きにわたり独自のものであり続けたことを喧伝するのが,改革派にとっては得策と考えられた.また,英語の伝統を遡るという営為は,王権神授説に対抗し,実際的にイングランドの法律や政治的慣行の起源を探るという当時の欲求に適うものでもあった.

古英語文献が印刷に付された最初のものは,Ælfric による復活祭説教集で,1566--67年に A Testimonie of Antiquity として世に出た.それから1世紀の時間をおいて,1659年には William Somner による初の古英語辞書 Dictionarium Saxonico-Latino-Anglicum が出版される.最初の古英語文法も,George Hickes によって1689年に出版されている.そして,1755年にはオックスフォード大学で最初の "Anglo-Saxon" 学の教授職が Richard Rawlinson により設定された(英語史上の1段階としての変種を表わすのに "Old English" ではなく "Anglo-Saxon" という用語が用いられてきたことについては,「#234. 英語史の時代区分の歴史 (3)」 ([2009-12-17-1]),「#236. 英語史の時代区分の歴史 (5)」 ([2009-12-19-1]) を参照).

このように,16--18世紀にかけて古英語研究が勃興ししてきた背景には,純粋に学問的な好奇心というよりは,宗教改革に端を発するすぐれて政治的な思惑があったのである.この経緯について,簡潔には Baugh and Cable (280fn) を,詳しくは武内の「第8章 イングランドのアングロ・サクソン学事始」を参照.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

・ 武内 信一 『英語文化史を知るための15章』 研究社,2009年.

2016-10-17 Mon

■ #2730. palatalisation [palatalisation][assimilation][consonant][phonetics][oe][vowel]

古英語期中に生じた子音変化のなかでも,現在にまで効果残っているものに,口蓋化 (palatalisation) がある.これまでにも,以下の記事を含め,様々な形でこの音韻過程について触れてきた.

・ 「#49. /k/ の口蓋化で生じたペア」 ([2009-06-16-1])

・ 「#168. <c> と <g> の音価」 ([2009-10-12-1])

・ 「#2015. seek と beseech の語尾子音」 ([2014-11-02-1])

・ 「#2054. seek と beseech の語尾子音 (2)」 ([2014-12-11-1])

・ 「#2367. 古英語の <c> から中英語の <k> へ」 ([2015-10-20-1])

英語の姉妹言語である Frisian にも認められる音韻過程であり(「#787. Frisian」 ([2011-06-23-1]) ,それが生じた時期は,英語史においても相応して古い段階のことと考えられている.具体的には,4--5世紀に始まり,11世紀まで進行したといわれる.

起こったことは,軟口蓋閉鎖音 [k], [gg], [g] 音が口蓋前寄りでの調音となり,かつ前者2つについては擦音化したことである.典型的に古英語で <c> で綴られた [k] は,[i, iː, e, eː, æ, æː, ie, iːe, eo, eːo, io, iːo, ea, eːa] のような前母音(を含む2重母音)の前後の位置で,無声口蓋閉鎖音 [c] となり,後に [ʧ] へと発展した.これにより,例えば ċiriċe [ˈcirice] は [ˈʧiriʧe] へ,ċeosan [ˈceozɑn] は [ˈʧeozɑn] へ,benċ [benc] は [benʧ] へと変化した.

[gg] については [k] と同じ環境で,有声口蓋閉鎖音の [ɟɟ] となり,後に擦音化して [ʤ] となった.これにより,brycg [bryɟɟ] は [bryʤ] へ,secg [seɟɟ] は [seʤ] へ, licgan [ˈliɟɟɑn] は [ˈliʤɑn] へと変化した.

[g] の場合も同様の条件で口蓋化して [j] となったが,これは擦音化しなかった.例として,ġift [gift] は [jift] へ, ġeong [geoŋg] は [jeoŋg] へ変化した.

これらの音韻過程の効果は,現代英語の多くの単語に継承されている.以上,寺澤・川崎 (4, 6) を参照した.

・ 寺澤 芳雄,川崎 潔 編 『英語史総合年表?英語史・英語学史・英米文学史・外面史?』 研究社,1993年.

2016-09-12 Mon

■ #2695. 中世英語における分かち書きの空白の量 [punctuation][manuscript][writing][scribe][word][prosody][oe][inscription][distinctiones]

現代の英語の書記では当然視されている分かち書き (distinctiones) が,古い時代には当然ではなく,むしろ続け書き (scriptio continua) が普通だったことについて,「#1903. 分かち書きの歴史」 ([2014-07-13-1]) で述べた.実際,古英語の碑文などでは語の区切りが明示されないものが多いし,古英語や中英語の写本においても現代風の一貫した分かち書きはいまだ達成されていない.

だが,分かち書きという現象そのものがなかったわけではない.「#572. 現存する最古の英文」 ([2010-11-20-1]) でみた最初期のルーン文字碑文ですら,語と語の間に空白ではなくとも小丸が置かれており,一種の分かち書きが行なわれていたことがわかるし,7世紀くらいまでには写本に記された英語にしても,語間の空白挿入は広く行なわれていた.ポイントは,「広く行なわれていた」ことと「現代風に一貫して行なわれていた」こととは異なるということだ.分かち書きへの移行は,古い続け書きの伝統の上に新しい分かち書きの方法が徐々にかぶさってきた過程であり,両方の書き方が共存・混在した期間は長かったのである.英語の句読法 (punctuation) の歴史について一般に言えるように,語間空白の規範は中世期中に定められることはなく,あくまで書き手個人の意志で自由にコントロールしてよい代物だった.

書き手には空白を置く置かないの自由が与えられていただけではなく,空白を置く場合に,どれだけの長さのスペースを取るかという自由も与えられていた.ちょうど現代英語の複合語において,2要素間を離さないで綴るか (flowerpot),ハイフンを挿入するか (flower-pot),離して綴るか (flower pot) が,書き手の判断に委ねられているのと似たような状況である.いや,現代の場合にはこの3つの選択肢しかないが,中世の場合には空白の微妙な量による調整というアナログ的な自由すら与えられていたのである.例えば,語より大きな統語的単位や意味的単位をまとめあげるために長めの空白が置かれたり,形態素レベルの小単位の境を表わすのに僅かな空白が置かれるなど,書き手の言語感覚が写本上に精妙に反映された.

Crystal (11-12) はこの状況を,Ælfric の説教からの例を挙げて説明している.

Very often, some spaces are larger than others, probably reflecting a scribe's sense of the way words relate in meaning to each other. A major sense-break might have a larger space. Words that belong closely together might have a small one. It's difficult to show this in modern print, where word-spaces tend to be the same width, but scribes often seemed to think like this:

we bought a cup of tea in the cafe

The 'little' words, such as prepositions, pronouns, and the definite article, are felt to 'belong' to the following content words. Indeed, so close is this sense of binding that many scribes echo earlier practice and show them with no separation at all. Here's a transcription of two lines from one of Ælfric's sermons, dated around 990.

þærwæronðagesewene twegenenglas onhwitumgẏrelū;

þær wæron ða gesewene twegen englas on hwitum gẏrelū;

'there were then seen two angels in white garments'

Eacswilc onhisacennednẏsse wæronenglasgesewene'.

Eacswilc on his acennednẏsse wæron englas gesewene'.

'similarly at his birth were angels seen'

The word-strings, separated by spaces, reflect the grammatical structure and units of sense within the sentence.

話し言葉では,休止 (pause) や抑揚 (intonation) の調整などを含む各種の韻律的な手段でこれと似たような機能を果たすことが可能だが,書き言葉でその方法が与えられていたというのは,むしろ現代には見られない中世の特徴というべきである.関連して「#1910. 休止」 ([2014-07-20-1]) も参照.

・ Crystal, David. Making a Point: The Pernickety Story of English Punctuation. London: Profile Books, 2015.

2016-09-02 Fri

■ #2685. イングランドとノルマンディの関係はノルマン征服以前から [norman_conquest][french][oe][monarch][history][family_tree]

「#302. 古英語のフランス借用語」 ([2010-02-23-1]) で触れたように,イングランドとノルマンディの接触は,ノルマン人の征服 (norman_conquest) 以前にも存在したことはあまり知られていない.このことは,英語とフランス語の接触もそれ以前から少ないながらも存在したということであり,英語史上の意味がある.

エゼルレッド無策王 (Ethelred the Unready) の妻はノルマンディ人のエマ (Emma) であり,彼女はヴァイキング系の初代ノルマンディ公ロロ (Rollo) の血を引く.エゼルレッドの義兄弟の孫が,実にギヨーム2世 (Guillaume II),後のウィリアム征服王 (William the Conqueror) その人である.別の観点からいうと,ウィリアム征服王は,エゼルレッドとエマから生まれた後のエドワード聖証王 (Edward the Confessor) にとって,従兄弟の息子という立場である.

今一度ロロの時代にまで遡ろう.ロロ (860?--932?) は,後にノルマン人と呼ばれるようになったデーン人の首領であり,一族ともに9世紀末までに北フランスのセーヌ川河口付近に定住し,911年にはキリスト教化した.このときに,ロロは初代ノルマンディ公として西フランク王シャルル3世 (Charles III) に臣下として受けいれられた.それ以降,歴代ノルマンディ公は婚姻を通じてフランス,イングランドの王家と結びつき,一大勢力として台頭した.

さて,その3代目リシャール1世 (Richard I) の娘エマは「ノルマンの宝石」と呼ばれるほどの美女であり,エゼルレッド無策王 (968--1016) と結婚することになった.2人から生まれたエドワードは,母エマの後の再婚相手カヌート (Canute) を嫌って母の郷里ノルマンディに引き下がり,そこで教育を受けたために,すっかりノルマン好みになっていた.そして,イングランドでデーン王朝が崩壊すると,このエドワードがノルマンディから戻ってきてエドワード聖証王として即位したのである.

このような背景により,イングランドとノルマンディのつながりは,案外早く1000年前後から見られたのである.

ロロに端を発するノルマン人の系統を中心に家系図を描いておこう.関連して,アングロサクソン王朝の系図については「#2620. アングロサクソン王朝の系図」 ([2016-06-29-1]) と「#2547. 歴代イングランド君主と統治年代の一覧」 ([2016-04-17-1]) で確認できる.

ロロ

│

│

ギヨームI世(長剣公)

│

│

リシャールI世(豪胆公)

│

│

┌─────────┴──────────┐

│ │

│ │

クヌート===エマ===エゼルレッド無策王 リシャールII世

│ │

│ │

┌────┴────┐ │

│ │ │

│ │ │

エドワード聖証王 アルフレッド │

│

┌──────────────────┘

│

┌────┴────┐

│ │

│ │

リシャールIII世 ロベールI世(悪魔公)===アルレヴァ

│

│

ギヨームII世(ウィリアム征服王)

2016-08-26 Fri

■ #2678. Beowulf から kenning の例を追加 [kenning][oe][compounding][metonymy][metaphor]

昨日の記事「#2677. Beowulf にみられる「王」を表わす数々の類義語」 ([2016-08-25-1]) で,古英詩の文体的技巧としての kenning に触れた.kenning の具体例は「#472. kenning」 ([2010-08-12-1]) で挙げたが,今回は Beowulf と少なくとももう1つの詩に現われる kenning の例をいくつか追加したい (Baker 136) .伏せ字をクリックすると意味が現われる.

| kenning | literal sense | meaning |

|---|---|---|

| bāncofa, masc. | "bone-chamber" | body |

| bānfæt, neut. | "bone-container" | body |

| bānhūs, neut. | "bone-house" | body |

| bānloca, neut. | "locked bone-enclosure" | body |

| brēosthord, neut. | "breast-hoard" | feeling, thought, character |

| frumgār, masc. | "first spear" | chieftain |

| hronrād, fem. | "whale-road" | sea |

| merestrǣt, fem. | "sea-street" | the way over the sea |

| nihthelm, masc. | "night-helmet" | cover of night |

| sāwoldrēor, masc. or neut. | "soul-blood" | life-blood |

| sundwudu, masc. | "sea-wood" | ship |

| wordhord, neut. | "word-hoard" | capacity for speech |

これらの kenning は現代人にとって新鮮でロマンチックに響くが,古英語ではすでに慣用表現として定着していたものもある.しかし,詩人が独自の kenning を自由に作り出し,用いることができたことも事実であり,Beowulf 詩人も確かに独創的な表現を生み出してきたのである.

なお,kenning には,メタファー (metaphor) が関与するものと,メトニミー (metonymy) が関与するものがある.例えば,bāncofa ほか bān- の複合語はメタファーであり,sundwudu はメトニミーの例である.また,hronrād ではメタファーとメトニミーの両方が関与しており,意味論的には複雑な kenning の例といえるだろう (cf. 「#472. kenning」 ([2010-08-12-1])) .

・ Baker, Peter S. Introduction to Old English. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

2016-08-25 Thu

■ #2677. Beowulf にみられる「王」を表わす数々の類義語 [synonym][oe][lexicology][compounding][kenning][beowulf][metonymy]

古英語は複合 (compounding) による語形成が非常に得意な言語だった.これは「#1148. 古英語の豊かな語形成力」 ([2012-06-18-1]) でも確認済みだが,複合語はとりわけ韻文において最大限に活用された.実際 Beowulf に代表される古英詩においては「王」「勇士」「戦い」「海」などの頻出する概念に対して,様々な類義語 (synonym) が用いられた.これは,単調さを避けるためでもあったし,昨日の記事「#2676. 古英詩の頭韻」 ([2016-08-24-1]) で取り上げた頭韻の規則に沿うために種々の表現が必要だったからでもあった.

以下,Baker (137) より,Beowulf (及びその他の詩)に現われる「王,主君」を表わす類義語を列挙しよう(複合語が多いが,単形態素の語も含まれている).

bēagġyfa, masc. ring-giver.

bealdor, masc. lord.

brego, masc. lord.

folcāgend, masc. possessor of the people.

folccyning, masc. king of the people.

folctoga, masc. leader of the people.

frēa, masc. lord.

frēadrihten, masc. lord-lord.

frumgār, masc. first spear.

godlgġyfa, masc. gold-giver.

goldwine, masc. gold-friend.

gūðcyning, masc. war-king.

herewīsa, masc. leader of an army.

hildfruma, masc. battle-first.

hlēo, masc. cover, shelter.

lēodfruma, masc. first of a people.

lēodġebyrġea, masc. protector of a people.

mondryhten, masc. lord of men.

rǣswa, masc. counsellor.

siġedryhten, masc. lord of victory.

sincġifa, masc. treasure giver.

sinfrēa, masc. great lord.

þenġel, masc. prince.

þēodcyning, masc. people-king.

þēoden, masc. chief, lord.

wilġeofa, masc. joy-giver.

wine, masc. friend.

winedryhten, masc. friend-lord.

wīsa, masc. guide.

woroldcyning, masc. worldly king.

ここには詩にしか現われない複合語も多く含まれており,詩的複合語 (poetic compound) と呼ばれている.第1要素が第2要素を修飾する folccyning (people-king) のような例もあれば,両要素がほぼ同義で冗長な frēadrihten (lord-lord) のような例もある.さらに,メトニミーを用いた謎かけ・言葉遊び風の bēagġyfa (ring-giver) もある.最後に挙げた類いの比喩的複合語は kenning と呼ばれ,古英詩における大きな特徴となっている(「#472. kenning」 ([2010-08-12-1]) を参照).

・ Baker, Peter S. Introduction to Old English. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

2016-08-24 Wed

■ #2676. 古英詩の頭韻 [alliteration][oe][consonant][stress][prosody][germanic]

英語には,主に語頭の子音を合わせて調子を作り出す頭韻 (alliteration) の伝統がある.本ブログでは,「#943. 頭韻の歴史と役割」 ([2011-11-26-1]) をはじめ,alliteration の各記事で,主に現代英語に残る頭韻の現象を扱ってきた.

しかし,英語史で「頭韻」といえば,なによりも古英詩における韻律規則としての頭韻が思い出される.頭韻は,古英語のみならず,古アイスランド語,古サクソン語,古高地ドイツ語などゲルマン諸語の韻文を特徴づける韻律上の手段であり,ラテン語・ロマンス諸語の脚韻 (rhyme) と際立った対比をなす.すぐれてゲルマン的なこの韻律手段について,古英詩においていかに使用されたかを,Baker (124--26) に拠って概説したい.

古英詩の1行 (line) は2つの半行 (verse) からなっており,前半行を on-verse (or a-verse),後半行を off-verse (or b-verse) と呼ぶ.その間には統語上の行間休止 (caesura) が挟まっており,現代の印刷では長めの空白で表わされるのが慣例である.各半行には2つの強勢音節(それぞれを lift と呼ぶ)が含まれており,その周囲には弱音節 (drop) が配置される.このように構成される詩行において,on-verse の2つの lifts の片方あるいは両方の語頭音と,off-verse の最初の lift の語頭音は,同じものとなる.これが古英詩の頭韻である.

頭韻の基本は語頭子音によるものだが,実際には語頭母音によるものもある.母音による頭韻では母音の音価は問わないので,例えば e と i でも押韻できる.また,子音による頭韻については,sc, sp, st の子音群に限って,その子音群自身と押韻しなければならず,例えば stān と sāriġ は押韻できない (see 「#2080. /sp/, /st/, /sk/ 子音群の特異性」 ([2015-01-06-1])) .一方,g と ġ,c と ċ は音価こそ異なれ,通常,互いに韻を踏むことができる.

頭韻が行に配置されるパターンには,いくつかのヴァリエーションがある.基本は以下の3種類である.

・ xa|ay: þæt biþ in eorle indryhten þēaw

・ ax|ay: þæt hē his ferðlocan fæste binde.

・ aa|ax: ne se hrēo hyġe helpe ġefremman

時々,以下のような ab|ab の型 (transverse alliteration) や ab|ba の型 (crossed alliteration) も見られるが,特別に修辞的な響きをもっていたと考えられる.

・ ab|ab: Þær æt hȳðe stōd hringedestefna

・ ab|ba: brūnfāgne helm, hringde byrnan

古英語頭韻詩の詩行は,上記の構造を基本として,その上で様々な細則に沿って構成されている.関連して,「#1897. "futhorc" の acrostic」 ([2014-07-07-1]),「#1560. Chaucer における頭韻の伝統」 ([2013-08-04-1]) も参照.

・ Baker, Peter S. Introduction to Old English. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

2016-08-02 Tue

■ #2654. a six-foot man や a ten-mile drive に残る(残っていない?)古英語の複数属格形 [inflection][genitive][plural][case][adjective][oe][dative]

現代英語には,標題のように数詞と単位が結ばれて複合形容詞となる表現がある.「#1766. a three-hour(s)-and-a-half flight」 ([2014-02-26-1]) でみたように,典型的には単位に相当する名詞は複数形をとらない.例外もあるが,普通には *a six-feet man や *a ten-miles drive とならない.なぜ複数形にならないのだろうか.

実は,この形は歴史的には複数属格の名残である.したがって,元来,当然ながら複数形だった.ところが,後に音韻形態変化が生じ,結果的に単数と同じ形に落ち着いてしまったというのが,事の次第である.

古英語では,このような表現において単位を表わす名詞は複数属格に屈折し,それが主要部を構成する名詞を修飾していた.fōt と mīl の場合には,このままの単数主格の形態ではなく,複数属格の形態に屈折させて fōta, mīla とした.ところが,中英語にかけて複数属格を表わす語尾 -a は /ə/ へと水平化し,さらに後には完全に消失した.結果として,形態としては何も痕跡を残すことなく立ち消えたのだが,複数属格の機能を帯びた語法そのものは型として受け継がれ,現在に至っている.現代英語で予想される複数形 *six-feet や *ten-miles になっておらず,一見すると不規則な文法にみえるが,これは古英語の文法項目の生き霊なのである.

古英語の名詞の格屈折の形態が,このように生き霊となって現代英語に残っている例は,著しく少ない.例えば,「#380. often の <t> ではなく <n> こそがおもしろい」 ([2010-05-12-1]) で触れた whilom, seldom, often の語末の「母音+鼻音」の韻に,かつての複数与格語尾 -um の変形したものを見ることができる.また,alive などには,古英語の前置詞句 on līfe に規則的にみられた単数与格語尾の -e が,少なくとも綴字上に生き残っている.ほかには,Lady Chapel や ladybird の第1要素 lady は無語尾のようにみえるが,かつては単数属格語尾 -e が付されていた.それが後に水平化・消失したために,形態的には痕跡を残していないだけである.

以上,Algeo and Pyles (105) を参考にして執筆した.

・ Algeo, John, and Thomas Pyles. The Origins and Development of the English Language. 5th ed. Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

2016-06-29 Wed

■ #2620. アングロサクソン王朝の系図 [family_tree][oe][monarch][history][anglo-saxon]

「#2547. 歴代イングランド君主と統治年代の一覧」 ([2016-04-17-1]) で挙げた一覧から,アングロサクソン王朝(古英語期)の系図,Egbert から William I (the Conqueror) までの系統図を参照用に掲げておきたい.

Egbert (829--39) [King of Wessex (802--39)]

│

│

Ethelwulf (839--56)

│

│

┌────┴──────┬──────────┬────────────┐

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ │

Ethelbald (856--60) Ethelbert (860--66) Ethelred I (866--71) Alfred the Great (871--99)

│

│

Edward the Elder (899--924)

│

│

┌────────────┬─────────────┤

│ │ │

│ │ │ ┌────────┐

Athelstan (924--40) Edmund I the Elder (945--46) Edred (946--55) ???HOUSE OF DENMARK???

│ │ └────────┘

│ │

Edwy (955--59) Edgar (959--75) Sweyn Forkbeard (1013--14)

│ │

│ │

┌────────────┤ │

│ │ │

│ │ │

Edward the Martyr (975--79) Ethelred II the Unready (979--1013, 1014--16) === Emma (--1052) === Canute (1016--35)

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ └─────┐

│ │ │ │

│ │ Hardicanute (1040--42) │

│ │ │

│ │ │

Edmund II Ironside (1016. 4--11) Edward the Confessor (1042--66) Harold I Harefoot (1035--40)

│

│

│ ┌─────────┐ ┌────────┐

Edward Atheling (--1057) ???HOUSE OF NORMANDY ??? ???HOUSE OF GODWIN ???

│ └─────────┘ └────────┘

│

│

Edgar Atheling (1066. 10--12) William the Conqueror (1066--87) Harold II (1066. 1--10)

2016-06-28 Tue

■ #2619. 古英語弱変化第2類動詞屈折に現われる -i- の中英語での消失傾向 [inflection][verb][oe][eme][conjugation][morphology][owl_and_nightingale][speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][3sp][3pp]

古英語の弱変化第2類に属する動詞では,屈折表のいくつかの箇所で "medial -i-" が現われる (「#2112. なぜ3単現の -s がつくのか?」 ([2015-02-07-1]) の古英語 lufian の屈折表を参照) .この -i- は中英語以降に失われていくが,消失のタイミングやスピードは方言,時期,テキストなどによって異なっていた.方言分布の一般論としては,保守的な南部では -i- が遅くまで保たれ,革新的な北部では早くに失われた.

古英語の弱変化第2類では直説法3人称単数現在の屈折語尾は -i- が不在の -aþ となるが,対応する(3人称)複数では -i- が現われ -iaþ となる.したがって,中英語以降に -i- の消失が進むと,屈折語尾によって3人称の単数と複数を区別することができなくなった.

消失傾向が進行していた初期中英語の過渡期には,一種の混乱もあったのではないかと疑われる.例えば,The Owl and the Nightingale の ll. 229--32 を見てみよう(Cartlidge 版より).

Vor eurich þing þat schuniet riȝt,

Hit luueþ þuster & hatiet liȝt;

& eurich þing þat is lof misdede,

Hit luueþ þuster to his dede.

赤で記した動詞形はいずれも古英語の弱変化第2類に由来し,3人称単数の主語を取っている.したがって,本来 -i- が現われないはずだが,schuniet と hatiet では -i- が現われている.なお,上記は C 写本での形態を反映しているが,J 写本での対応する形態はそれぞれ schonyeþ, luuyeþ, hateþ, luueþ となっており,-i- の分布がここでもまちまちである.

schuniet については,先行詞主語の eurich þing が意味上複数として解釈された,あるいは本来は alle þing などの真正な複数主語だったのではないかという可能性が指摘されてきたが,Cartlidge の注 (Owl 113) では,"it seems more sensible to regard these lines as an example of the Middle English breakdown of distinctions made between different forms of Old English Class 2 weak verbs" との見解が示されている.

Cartlidge は別の論文で,このテキストにおける -i- について述べているので,その箇所を引用しておこう.

In both C and J, the infinitives of verbs descended from Old English Class 2 weak verbs in -ian always retain an -i- (either -i, -y, -ye, -ie, -ien or -yen). However, for the third person plural of the indicative, J writes -yeþ five times, as against nine cases of -eþ or -þ; while C writes -ieþ or -iet seven times, as against seven cases of -eþ, -ed, or -et. In the present participle, both C and J have medial -i- twice beside eleven non-conservative forms. The retention of -i in some endings also occurs in many later medieval texts, at least in the south, and its significance may be as much regional as diachronic. (Cartlidge, "Date" 238)

ここには,-i- の消失の傾向は方言・時代によって異なっていたばかりでなく,屈折表のスロットによってもタイミングやスピードが異なっていた可能性が示唆されており,言語変化のスケジュール (schedule_of_language_change) の観点から興味深い.

・ Cartlidge, Neil, ed. The Owl and the Nightingale. Exeter: U of Exeter P, 2001.

・ Cartlidge, Neil. "The Date of The Owl and the Nightingale." Medium Aevum 65 (1996): 230--47.

2016-06-10 Fri

■ #2601. なぜ If I WERE a bird なのか? [be][verb][subjunctive][preterite][conjugation][inflection][oe][sobokunagimon]

現代英文法の「仮定法過去」においては,条件の if 節のなかで動詞の過去形が用いられるのが規則である.その過去形とは,基本的には直説法の過去形と同形のものを用いればよいが,1つだけ例外がある.標題のように主語が1人称単数が主語の場合,あるいは3人称単数の場合には,直説法で was を用いるところに,仮定法では were を用いなければならない(現代英語の口語においては was が用いられることもあるが,規範文法では were が規則である).これはなぜだろうか.

もっとも簡単に答えるのであれば,それが古英語において接続法過去の1・3人称単数の屈折形だったからである(現代の「仮定法」に相当するものを古英語では「接続法」 (subjunctive) と呼ぶ).

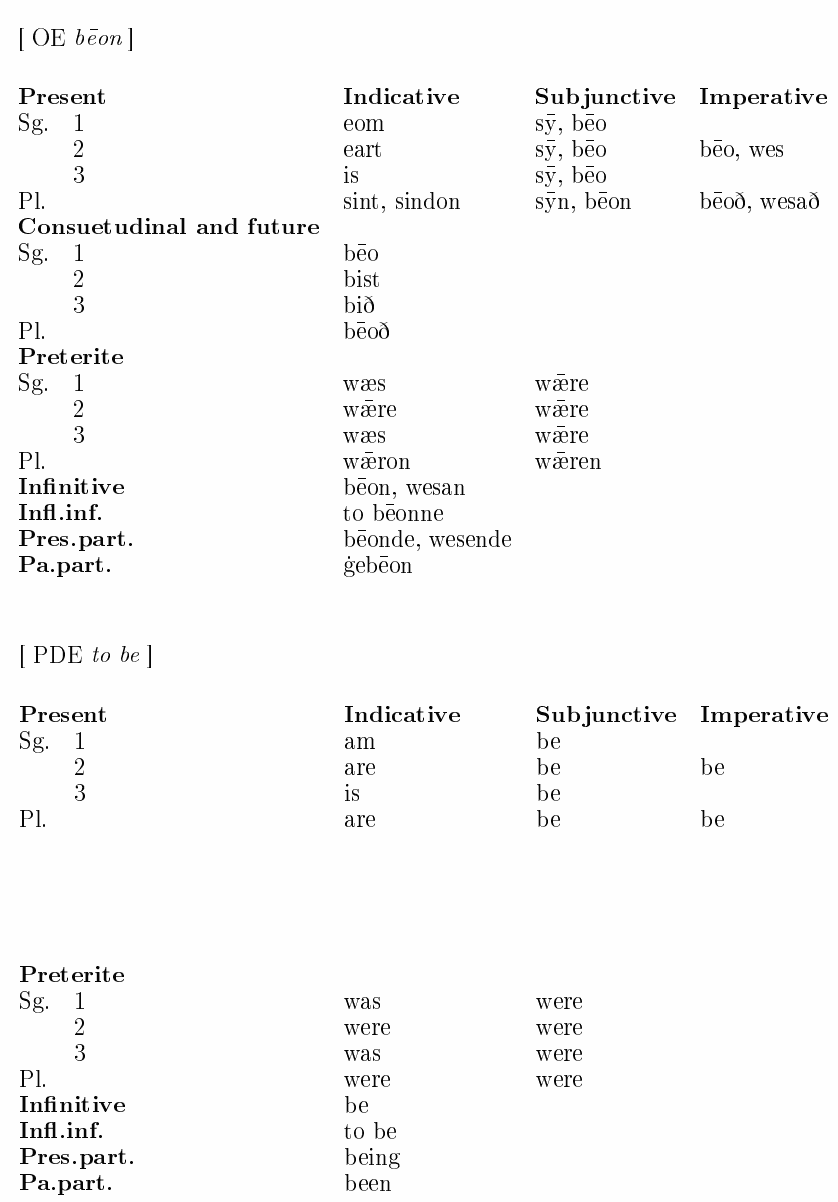

昨日の記事「#2600. 古英語の be 動詞の屈折」 ([2016-06-09-1]) で掲げた古英語 bēon の屈折表で,Subjunctive Preterite の欄を見てみると,単数系列では人称にかかわらず wǣre が用いられている.つまり,古英語で ġif ic wǣre . . . などと言っていた,だからこそ現代英語でも if I were . . . なのである.

現代英語では,ほとんどの場合,仮定法過去の形態として,上述のように直説法過去の形態をそのまま用いればよいために,特に意識して仮定法過去の屈折形や屈折表を直説法過去と区別して覚える必要がない.しかし,歴史的には直説法(過去)と仮定法(過去)は機能的にも形態的にも明確に区別されるべき異なる体系であり,各々の動詞に関して法に応じた異なる屈折形と屈折表が用意されていた.ところが,後の歴史のなかで屈折語尾の水平化や形態的な類推が作用し,be 動詞以外のすべての動詞に関して接続法過去形は直説法過去形と同一となった.唯一かつての形態的な区別を保持して生き延びてきたのが be だったということである.残存の主たる理由は,be があまりに高頻度であることだろう.

標題の「なぜ If I WERE a bird なのか?」という問いは,現代英語の共時的な観点からは自然で素朴な疑問といえる.しかし,英語史の観点から問いを立て直すのであれば,「なぜ,いかにして be 動詞以外のすべての動詞において接続法過去形と直説法過去形が同一となったのか」こそが問われるべきである.

2016-06-09 Thu

■ #2600. 古英語の be 動詞の屈折 [suppletion][be][verb][conjugation][inflection][oe][paradigm][indo-european][etymology]

現代英語で最も複雑な屈折を示す動詞といえば,be 動詞である.屈折がおおいに衰退している現代英語にあって,いまだ相当の複雑さを保っている唯一の動詞だ.あまりに頻度が高すぎて,不規則さながらのパラダイムが生き残ってしまったのだろう.

しかし,古英語においても,当時の屈折の水準を考慮したとしても,be 動詞の屈折はやはり複雑だった.以下に,古英語 bēon と現代英語 be の屈折表を掲げよう (Hogg and Fulk 309) .

明らかに異なる語根に由来する種々の形態が集まって,屈折表を構成していることがわかる.換言すれば,be 動詞の屈折表は補充法 (suppletion) の最たる例である.be は,印欧語比較言語学的には "athematic verb" と呼ばれる動詞の1つであり,そのなかでも最も複雑な歴史をたどってきた.Hogg and Fulk (309--10) によれば,古英語 bēon の諸形態はおそらく4つの語根に遡る.

1つ目は,PIE *Hes- に由来するもので,古英語の母音あるいは s で始まる形態に反映されている(s で始まるものは,ゼロ階梯の *Hs- に由来する; cf. ラテン語 sum).

2つ目は,PIE *bhew(H)- に由来し,古英語では b で始まる形態に反映される(cf. ラテン語 fuī 'I have been').古英語では,この系列は習慣的あるいは未来の含意を伴うことが多かった.

3つ目は,PIE *wes- に遡り,古英語(そして現代英語に至るまで)ではもっぱら過去系列の形態として用いられる.元来は強変化第5類の動詞であり,現在形も備わっていたが,古英語期までに過去系列に限定された.

4つ目は,古英語の直説法現在2人称単数の eart を説明すべく,起源として PIE *er- が想定されている(cf. ラテン語 orior 'I rise' と同語根).

be 動詞のパラダイムは,古英語以来ある程度は簡略化されてきたものの,今なお,長い歴史のなかで培われた複雑さは健在である.

・ Hogg, Richard M. and R. D. Fulk. A Grammar of Old English. Vol. 2. Morphology. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2016-05-18 Wed

■ #2578. ケルト語を通じて英語へ借用された一握りのラテン単語 [loan_word][latin][celtic][oe][borrowing][statistics]

ブリテン島が紀元43年から410年までのあいだローマの支配化に置かれ,島内である程度ラテン語が話されていたという事実から,この時期に用いられていたラテン単語が,後に島内の主たる言語となる英語にも,相当数残っているはずではないかと想像されるかもしれない.当時のラテン単語の多くが,ケルト語話者が媒介となって,後に英語にも伝えられたのではないかと.しかし,実際にはそのような状況は起こらなかった.Baugh and Cable (77) によると,

It would be hardly too much to say that not five words outside of a few elements found in place-names can be really proved to owe their presence in English to the Roman occupation of Britain. It is probable that the use of Latin as a spoken language did not long survive the end of Roman rule in the island and that such vestiges as remained for a time were lost in the disorders that accompanied the Germanic invasions. There was thus no opportunity for direct contact between Latin and Old English in England, and such Latin words as could have found their way into English would have had to come in through Celtic transmission. The Celts, indeed, had adopted a considerable number of Latin words---more than 600 have been identified--- but the relations between the Celts and the English were such . . . that these words were not passed on.

当時のケルト語には600語近くラテン単語が入っていたというのは,知らなかった.さて,古英語に入ったのはきっかり5語にすぎないといっているが,Baugh and Cable (77--78) が挙げているのは,ceaster (< L castra "camp"), port (< L portus, porta "harbor, gate, town"), munt (< L mōns, montem "mountain"), torr (L turris "tower, rock"), wīc (< L vīcus "village") である.これですら語源に異説のあるものもあり,ケルト語経由で古英語に入ったラテン借用語の確実な例とはならないかもしれない.その他,地名要素としての street, wall, wine などが加えられているが,いずれにせよそのようなルートで古英語に入ったラテン借用語一握りしかない.

「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1]),「#1437. 古英語期以前に借用されたラテン語の例」 ([2013-04-03-1]),「#1945. 古英語期以前のラテン語借用の時代別分類」 ([2014-08-24-1]) などで触れたように,英語史においてラテン単語の借用の波と経路は何度かあったが,この Baugh and Cable の呼ぶところのラテン単語借用の第1期に関しては,見るべきものが特に少ないと言っていいだろう.Baugh and Cable (78) の結論を引こう.

At best . . . the Latin influence of the First Period remains much the slightest of all the influences that Old English owed to contact with Roman civilization.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-04-30 Sat

■ #2560. 古英語の形容詞強変化屈折は名詞と代名詞の混合パラダイム [adjective][ilame][terminology][morphology][inflection][oe][germanic][paradigm][personal_pronoun][noun]

古英語の形容詞の強変化・弱変化の区別については,ゲルマン語派の顕著な特徴として「#182. ゲルマン語派の特徴」 ([2009-10-26-1]),「#785. ゲルマン度を測るための10項目」 ([2011-06-21-1]),「#687. ゲルマン語派の形容詞の強変化と弱変化」 ([2011-03-15-1]) で取り上げ,中英語における屈折の衰退については ilame の各記事で話題にした.

強変化と弱変化の区別は古英語では名詞にもみられた.弱変化形容詞の強・弱屈折は名詞のそれと形態的におよそ平行しているといってよいが,若干の差異がある.ことに形容詞の強変化屈折では,対応する名詞の強変化屈折と異なる語尾が何カ所かに見られる.歴史的には,その違いのある箇所には名詞ではなく人称代名詞 (personal_pronoun) の屈折語尾が入り込んでいる.つまり,古英語の形容詞強変化屈折は,名詞屈折と代名詞屈折が混合したようなものとなっている.この経緯について,Hogg and Fulk (146) の説明に耳を傾けよう.

As in other Gmc languages, adjectives in OE have a double declension which is syntactically determined. When an adjective occurs attributively within a noun phrase which is made definite by the presence of a demonstrative, possessive pronoun or possessive noun, then it follows one set of declensional patterns, but when an adjective is in any other noun phrase or occurs predicatively, it follows a different set of patterns . . . . The set of patterns assumed by an adjective in a definite context broadly follows the set of inflexions for the n-stem nouns, whilst the set of patterns taken in other indefinite contexts broadly follows the set of inflexions for a- and ō-stem nouns. For this reason, when adjectives take the first set of inflexions they are traditionally called weak adjectives, and when they take the second set of inflexions they are traditionally called strong adjectives. Such practice, although practically universal, has less to recommend it than may seem to be the case, both historically and synchronically. Historically, . . . some adjectival inflexions derive from pronominal rather than nominal forms; synchronically, the adjectives underwent restructuring at an even swifter pace than the nouns, so that the terminology 'strong' or 'vocalic' versus 'weak' or 'consonantal' becomes misleading. For this reason the two declensions of the adjective are here called 'indefinite' and 'definite' . . . .

具体的に強変化屈折のどこが起源的に名詞的ではなく代名詞的かというと,acc.sg.masc (-ne), dat.sg.masc.neut. (-um), gen.dat.sg.fem (-re), nom.acc.pl.masc. (-e), gen.pl. for all genders (-ra) である (Hogg and Fulk 150) .

強変化・弱変化という形態に基づく,ゲルマン語比較言語学の伝統的な区分と用語は,古英語の形容詞については何とか有効だが,中英語以降にはほとんど無意味となっていくのであり,通時的にはより一貫した統語・意味・語用的な機能に着目した不定 (definiteness) と定 (definiteness) という区別のほうが妥当かもしれない.

・ Hogg, Richard M. and R. D. Fulk. A Grammar of Old English. Vol. 2. Morphology. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2016-04-26 Tue

■ #2556. 現代英語に受け継がれた古英語語彙はどのくらいあるか (2) [oe][pde][lexicology][statistics]

どのくらいの割合の古英語語彙が現代にまで残存しているかという問題について,「#450. 現代英語に受け継がれた古英語の語彙はどのくらいあるか」 ([2010-07-21-1]),「#384. 語彙数とゲルマン語彙比率で古英語と現代英語の語彙を比較する」 ([2010-05-16-1]),「#45. 英語語彙にまつわる数値」 ([2009-06-12-1]) でいくつかの数値をみてきた.最後に挙げた記事に追記したように,Gelderen (73) によれば,古英語にあった本来語の8割が失われた可能性があるという.

同じ問題について,Baugh and Cable (52) は約85%という数字を提示している.関係する箇所を引用しよう.

The vocabulary of Old English is almost purely Germanic. A large part of this vocabulary, moreover, has disappeared from the language. When the Norman Conquest brought French into England as the language of the higher classes, much of the Old English vocabulary appropriate to literature and learning died out and was replaced later by words borrowed from French and Latin. An examination of the words in an Old English dictionary shows that about 85 percent of them are no longer in use. Those that survive, to be sure, are basic elements of our vocabulary and by the frequency with which they recur make up a large part of any English sentence.

「#450. 現代英語に受け継がれた古英語の語彙はどのくらいあるか」 ([2010-07-21-1]) で解説したように,このような統計の背後には様々な前提がある.何を語と認めるか,何を辞書の見出しに採用するかという根本的な問題もあれば,現代までの音韻形態的な連続性に注目するのと意味的な連続性に注目するのとでは観点が異なってくる.だが,古英語を読んでいる実感としては,現代英語の語彙の知識だけでは太刀打ちできない尺度として,このくらい高い数値が出てもおかしくはないとは思われる.年度の始めで古英語入門を始めている学生もいると思われるが,この数値はちょっとした驚き情報ではないだろうか.

・ Gelderen, Elly van. A History of the English Language. Amsterdam, John Benjamins, 2006.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-03-27 Sun

■ #2526. 古英語と中英語の文学史年表 [literature][chronology][timeline][me][oe][history]

中世英文学の主要作品と年表について「#1433. 10世紀以前の古英語テキストの分布」 ([2013-03-30-1]),「#1044. 中英語作品,Chaucer,Shakespeare,聖書の略記一覧」 ([2012-03-06-1]),「#2323 中英語の方言ごとの主要作品」 ([2015-09-06-1]),「#2503. 中英語文学」 ([2016-03-04-1]) で見てきたが,もう少し一覧性の高いものが欲しいと思い,Treharne の中世英文学作品集の pp. xvi--xvii に掲げられている年表を再現することにした.政治史と連動した文学史の年表となっている.

| Historical events | Literary landmarks |

|---|---|

| From c. 449: Anglo-Saxon settlements | |

| 597: St Augustine arrives to convert Anglo-Saxons | |

| 664: Synod of Whitby | |

| c. 670? Cædmon's Hymn | |

| 731: Bede finishes Ecclesiastical History | |

| 735: Death of Bede | |

| 793: Vikings raid Lindisfarne | |

| 869: Vikings kill King Edmund of East Anglia | |

| 879--99: Alfred reigns as king of Wessex | from c. 890: Anglo-Saxon Chronicle |

| Alfredian translations of Bede's Ecclesiastical History; Gregory's Pastoral Care; Orosius; Boethius's Consolation of Philosophy; Augustine's Soliloquies | |

| 937: Battle of Brunanburh | |

| from c. 950: Benedictine reform | |

| c. 970: Exeter Book copied | |

| 959--75: King Edgar reigns | c. 975: Vercelli Book copied |

| 978--1016: Æthelred 'the Unready' reigns | 990s: Ælfric's Catholic Homilies and Lives of Saints |

| c. 1010: death of Ælfric | c. 1010?: Junius manuscript copied |

| c. 1014: Wulfstan's sermo Lupi ad Anglos | |

| 1016--35: Cnut, king of England | |

| 1023: death of Wulfstan | |

| 1042--66: Edward the confessor reigns | Apollonius of Tyre |

| 1066: Battle of Hastings | |

| 1066--87: William the Conqueror reigns | |

| 1135: Stephen becomes king | Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae |

| 1135--54: civil war between King Stephen and Empress Matilda | Peterborough Chronicle continuations |

| 1154--89: Henry II reigns | 1155: Wace's Roman de Brut |

| 1170--90: Chrétien de Troyes's Romances | |

| c. 1170s: The Orrmulum | |

| Poema Morale | |

| 1180s: Marie de France's Lais | |

| 1189--99: Richard I reigns | c. 1190--1200? Trinity Homilies |

| 1199--1216: John reigns | c. 1200? Hali Meiðhad |

| 1204: loss of Normandy | |

| 1215: Magna Carta | |

| 1215: fourth Lateran Council | |

| 1216--72: Henry III reigns | c. 1220 Laȝamon's Brut |

| 1224: Franciscan friars arrive in England | c. 1225: Ancrene Wisse |

| c. 1225: King Horn | |

| 1272--1307: Edward I reigns | Manuscript Digby 86 copied |

| Manuscript Jesus 29 copied | |

| Manuscript Cotton Caligula A. ix copied | |

| Manuscript Arundel 292 copied | |

| Manuscript Trinity 323 copied | |

| South English Legendary composed | |

| c. 1300: Cursor Mundi | |

| 1303: Robert Mannyng of Brunne begins Handlyng Synne | |

| 1307--27: Edward II reigns | |

| 1327--77: Edward III reigns | Auchinleck Manuscript copied |

| Manuscript Harley 2253 copied | |

| 1337(--1454): Hundred Years' War with France | |

| 1338: Robert Mannyng of Brunne's Chronicle | |

| 1340: Ayenbite of Inwit | |

| c. 1343: Geoffrey Chaucer born | |

| Ywain and Gawain translated | |

| 1349: Black Death comes to England | |

| 1349: Richard Rolle dies | |

| 1355--80: Athelston | |

| Wynnere and Wastoure written | |

| 1360s--1390s: Piers Plowman | |

| 1362: English displaces French as language of lawcourts and Parliament | |

| 1370s--1400: Canterbury Tales | |

| 1377: Richard II accedes to throne | 1370s: Julian of Norwich's Vision |

| 1381: Peasants' Revolt breaks out | |

| 1399: Richard II deposed | |

| 1399: Henry IV accedes to the throne | |

| c. 1400: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight | |

| c. 1400: Chaucer dies | |

| c. 1410--30: Book of Margery Kempe |

・ Treharne, Elaine, ed. Old and Middle English c. 890--c. 1450: An Anthology. 3rd ed. Malden, Mass.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

2015-09-28 Mon

■ #2345. 古英語の diglossia と中英語の triglossia [diglossia][sociolinguistics][bilingualism][oe][me][latin][french]

社会言語学の話題として取り上げられる diglossia は,しばしば英語史にも適用されてきた.これについては,本ブログでも以下の記事などで取り上げてきた.

・ 「#661. 12世紀後期イングランド人の話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-02-17-1])

・ 「#1203. 中世イングランドにおける英仏語の使い分けの社会化」 ([2012-08-12-1])

・ 「#1486. diglossia を破った Chaucer」 ([2013-05-22-1])

・ 「#1488. -glossia のダイナミズム」 ([2013-05-24-1])

・ 「#1489. Ferguson の diglossia 論文と中世イングランドの triglossia」 ([2013-05-25-1])

・ 「#2148. 中英語期の diglossia 描写と bilingualism 擁護」 ([2015-03-15-1])

・ 「#2328. 中英語の多言語使用」 ([2015-09-11-1])

単純化して述べれば,古英語は diglossia の時代,中英語は triglossia の時代である.アングロサクソン時代の初期には,ラテン語の役割はいまだ大きくなかったが,キリスト教が根付いてゆくにつれ,その社会的な重要性は増し,アングロサクソン社会は diglossia となった.Nevalainen and Tieken-Boon van Ostade (272) によれば,

. . . Anglo-Saxon England became a diglossic society, in that one language came to be used in one set of circumstances, i.e. Latin as the language of religion, scholarship and education, while another language, English, was used in an entirely different set of circumstances, namely in all those contexts in which Latin was not used. In other words, Latin became the High language and English, in its many different dialects, the Low language.

しかし,重要なのは,英語は当時のヨーロッパでは例外的に,法律や文学という典型的に High variety の使用がふさわしいとされる分野においても用いられたことである.古英語の diglossia は,この点でやや変則的である.

中英語期に入ると,イングランド社会における言語使用は複雑化する.再び Nevalainen and Tieken-Boon van Ostade (272--73) から引用する.

This diglossic situation was complicated by the coming of the Normans in 1066, when the High functions of the English language which had evolved were suddenly taken over by French. Because the situation as regards Latin did not change --- Latin continued to be primarily the language of religion, scholarship and education --- we now have what might be referred to as a triglossic situation, with English once more reduced to a Low language, and the High functions of the language shared by Latin and French. At the same time, a social distinction was introduced within the spoken medium, in that the Low language was used by the common people while one of the High languages, French, became the language of the aristocracy. The use of the other High language, Latin, at first remained strictly defined as the medium of the church, though eventually it would be adopted for administrative purposes as well. . . . [T]he functional division of the three languages in use in England after the Norman Conquest neatly corresponds to the traditional medieval division of society into the three estates: those who normally fought used French, those who worked, English, and those who prayed, Latin.

このあと後期中英語にかけてフランス語の使用が減り,近代英語期中にはラテン語の使用分野もずっと限られるようになり,結果としてイングランドは monoglossia 社会へ移行した.以降,英語はむしろ世界各地の diglossia や triglossia に, High variety として関与していくのである.

・ Nevalainen, Terttu and Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade. "Standardisation." Chapter 5 of A History of the English Language. Ed. Richard Hogg and David Denison. Cambridge: CUP, 2006. 271--311.

2015-08-18 Tue

■ #2304. 古英語の hundseofontig (seventy), hundeahtatig (eighty), etc. (2) [numeral][oe][germanic][bibliography][indo-european][comparative_linguistics]

「#2286. 古英語の hundseofontig (seventy), hundeahtatig (eighty), etc.」 ([2015-07-31-1]) で,70から120までの10の倍数表現について,古英語では hund- (hundred) を接頭辞風に付加するということを見た.背景には,本来のゲルマン語の伝統的な12進法と,キリスト教とともにもたらされたと考えられる10進法との衝突という事情があったのではないかとされるが,いかなる衝突があり,その衝突がゲルマン諸語の数詞体系にどのような結果を及ぼしたのかについて,具体的なところがわからない.

もう少し詳しく調査してみようと立ち上がりかけたところで,この問題についてかなりの先行研究,あるいは少なくとも何らかの言及があることを知った.印欧語あるいはゲルマン語の比較言語学の立場からの論考が多いようだ.以下は主として Hogg and Fulk (189) に挙げられている文献だが,何点か他書からのものも含めてある.

・ Bosworth, Joseph, T. Northcote Toller and Alistair Campbell, eds. An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Vol. 2: Supplement by T. N. Toller; Vol. 3: Enlarged Addenda and Corrigenda by A. Campbell to the Supplement by T. N. Toller. Oxford: OUP, 1882--98, 1908--21, 1972. (sv hund-)

・ Hogg, Richard M. and R. D. Fulk. A Grammar of Old English. Vol. 2. Morphology. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

・ Lühr, R. "Die Dekaden '70--120' im Germanischen." Münchener Studien zur Sprachwissenschaft 36 (1977). 59--71.

・ Mengden, F. von. "How Myths Persist: Jacob Grimm, the Long Hundred and Duodecimal Counting." Englische Sprachwissenschaft und Mediävistik: Standpunkte, Perspectiven, neue Wege. Ed. G. Knappe. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2005. 201--21.

・ Mengden, F. von. "The Peculiarities of the Old English Numeral System." Medieval English and Its Heritage: Structure, Meaning and Mechanisms of Change. Ed. N. Ritt, H. Schendl, C. Dalton-Puffer, and D. Kastovsky. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2006. 125--45.

・ Mengden, F. von. 2010. Cardinal Numbers: Old English from a Cross-Linguistic Perspective. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. (see pp. 87--94.)

・ Nielsen, H. F. "The Old English and Germanic Decades." Nordic Conference for English Studies 4. Ed. G. Caie. 2 vols. Copenhagen: Department of English, University of Copenhagen, I, 1990. 105--17.

・ Voyles, Joseph B. Early Germanic Grammar: Pre-, Proto-, and Post-Germanic Languages. Bingley: Emerald, 2008. (see pp. 245--47.)

Nielsen の論文は,研究史をよくまとめているようであり,印欧語比較言語学の大家 Szemerényi が Studies in the Indo-European Systems of Numerals (1960) で唱えた純粋に音韻論的な説明を擁護しているという.

すぐに入手できる文献が少なかったので,今回は書誌を挙げるにとどめておきたい.

2015-07-31 Fri

■ #2286. 古英語の hundseofontig (seventy), hundeahtatig (eighty), etc. [numeral][oe][germanic]

昨日の記事「#2285. hundred は "great ten"」 ([2015-07-30-1]) で hundred の語源を話題にしたが,古英語 hund に関してもう1つ興味深い事実がある.古英語では,10の倍数を表わすのに,現代英語で9までの数詞に -ty を付加するのと同様に,-tiġ を付加した (Campbell 284--85) .twēntiġ, þrītiġ, fēowertiġ, fīftiġ, siextiġ の如くである.ところが,70以上になると,語頭に hund が接頭辞のように付加するのだ.しかも,その方法が100,110,120まで続くのである:hundseofontiġ, hundeahtatiġ, hundnigontiġ, hundtēontiġ, hundændlæftiġ, hundtwelftiġ.この語頭の hund- は無強勢に発音され,方言によっては -un となったり,消失するなど,古英語でも早くから弱化してはいたようだ.

「100」については,この回りくどい複合形 hundtēontiġ のほかに,当然ながら単純形 hund(red) も用いられていた.これは,ゲルマン民族では本来12進法が用いられていたことと関係するようだ.古いゲルマン諸語では「100」を hundtēontiġ のように複合語として表現するのが習慣であり,単純形 hund(red) に相当する語はむしろ「120」を表わしていた (cf. long [great] hundred) .この方式を遅くまで残していたのは古ノルド語で,そこでは「100」は tīu tigir (= *tenty),「120」は hundrað,「1200」は þūsund と表現されていた.『英語語源辞典』によると,ゲルマン民族は,後におそらくキリスト教の影響で10進法へと転向したのだろうとされる.

さて,古英語の hundseofontiġ, hundeahtatiġ などの表現に戻るが,60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 110, 120 において hund- が付加するということは,やはりゲルマン民族の元来の12進法との関連を疑わざるを得ない.背後にどのような理屈があって付加されているのかについては様々な議論があるようだ.

OED より †hund, n. (and adj.) の第2語義を再現しておこう.

2. The element hund- was also prefixed in Old English to the numerals from 70 to 120, in Old English hund-seofontig, hund-eahtatig, hund-nigontig, hund-téontig, hund-endlyftig (-ælleftig), hund-twelftig, some of which are also found in early Middle English.

[No certain explanation can be offered of this hund-, which appears in Old Saxon as ant-, Dutch t- in tachtig, and may be compared with -hund in Gothic sibuntê-hund, etc., and Greek -κοντα.]

・ Campbell, A. Old English Grammar. Oxford: OUP, 1959.

2015-07-29 Wed

■ #2284. eye の発音の歴史 [pronunciation][oe][phonetics][vowel][spelling][gvs][palatalisation][diphthong][three-letter_rule]

eye について,その複数形の歴史的多様性を「#219. eyes を表す172通りの綴字」 ([2009-12-02-1]) で示した.この語は,発音に関しても歴史的に複雑な過程を経てきている.今回は,eye の音変化の歴史を略述しよう.

古英語の後期ウェストサクソン方言では,この語は <eage> と綴られた.発音としては,[æːɑɣe] のように,長2重母音に [g] の摩擦音化した音が続き,語尾に短母音が続く音形だった.まず,古英語期中に語頭の2重母音が滑化して [æːɣe] となった.さらにこの母音は上げの過程を経て,中英語期にかけて [eːɣe] という音形へと発達した.

一方,有声軟口蓋摩擦音は前に寄り,摩擦も弱まり,さらに語尾母音は曖昧化して /eːjə/ が出力された.語中の子音は半母音化し,最終的には高母音 [ɪ] となった.次いで,先行する母音 [e] はこの [ɪ] と融合して,さらなる上げを経て,[iː] となるに至る.語末の曖昧母音も消失し,結果として後期中英語には語全体として [iː] として発音されるようになった.

ここからは,後期中英語の I [iː] などの語とともに残りの歴史を歩む.高い長母音 [iː] は,大母音推移 (gvs) を経て2重母音化し,まず [əɪ] へ,次いで [aɪ] へと発達した.標準変種以外では,途中段階で発達が止まったり,異なった発達を遂げたものもあるだろうが,標準変種では以上の長い過程を経てきた.以下に発達の歴史をまとめて示そう.

| /æːɑɣe/ |

| ↓ |

| /æːɣe/ |

| ↓ |

| /eːɣe/ |

| ↓ |

| /eːjə/ |

| ↓ |

| /eɪə/ |

| ↓ |

| /iːə/ |

| ↓ |

| /iː/ |

| ↓ |

| /əɪ/ |

| ↓ |

| /aɪ/ |

なお,現在の標準的な綴字 <eye> は古英語 <eage> の面影を伝えるが,共時的には「#2235. 3文字規則」 ([2015-06-10-1]) を遵守しているかのような綴字となっている.場合によっては *<ey> あるいは *<y> のみでも用を足しうるが,ダミーの <e> を活用して3文字に届かせている.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow