2025-08-15 Fri

■ #5954. 「子供」を意味する古英語 bearn,現代スコットランド方言の bairn について --- ykagata さんのブログ記事より [hee][german][dialectology][oe][scots_english][germanic]

ヘルメイトの ykagata さんが,HatenaBlog 上で展開しているブログ 「blog.heartyfluid --- 勉強したることども」にて,「『英語語源ハンドブック』にこじつけて学ぶドイツ語」と題する魅力的なシリーズを始められている.昨日までに『英語語源ハンドブック』より a/an, baby, cake, dad/daddy, each を取り上げた5つの記事が公開されており,A to Z にかける野心が感じられる.(応援しています!)

8月11日に投稿されたシリーズ第2弾「『英語語源ハンドブック』にこじつけて学ぶドイツ語 #2 baby」より,英単語 baby の他言語への展開の様子をおもしろく読んでいたが,「余談:ゲルマン祖語 *barną 「赤ちゃん」について」の1節に目が留まった.「赤ちゃん」から転じて「子供」を意味するようになった単語として,*barną 系列のものは,現代標準ドイツ語では残っていないという.そこでは,むしろ *kinþą 系の Kind が早くから一般化したとのことだ.ところが,南ドイツ・オーストリア・スイスの一部方言では,*barną 系列の Bua (少年)や Bar/Bärn (子)が用いられているという.

英語史を学んでいると,ここでピンとくる.古英語で「子供;子孫」を意味する頻出語で中性名詞の bearn のことだ.OED によると,この語は中英語では主に barn として存続した(この語形には古ノルド語の同根語が関与している可能性がある)が,後の標準英語にはほとんど残らなかった.しかし,スコットランドでは bairn の形で歴史を通じて使用され続け,現代でも普通に用いられている.標準英語でも1700年以来,文学語として bairn がときに見られるが,これはスコットランド語法の借用と解釈するのがよさそうだ.

ドイツ語においても英語においても,「子供」を意味する類義語間の選択が,方言に応じて割れているというのがおもしろい.動物語や遊びの言葉など,子供が日常的に好むものの名前には方言差が出やすいとされるが,「子供」という語そのものにも類似した傾向があるのだろうか.

2025-07-14 Mon

■ #5922. 「主の祈りで味わう古英語の文体」 --- 小河舜さんによる力の入った Helvillian コンテンツ [helvillian][notice][heldio][oe][wulfstan][aelfric][stylistics][bible][ogawashun]

先日,Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」の「#1501. 「主の祈り」で味わう古英語の文体 --- Helvillian 7月号掲載,小河舜さんによる渾身の記事」でも語りましたが,これは改めて hellog 記事としても広く紹介しなければならないと思い,筆を執っています.hellog/heldio ではすっかりお馴染みで,先日刊行された『英語語源ハンドブック』でも校閲協力者として多大な貢献をしてくださった,上智大学の小河舜さんが,驚くべきコンテンツを公にしてくれました.

Helvillian は,heldio リスナーの有志によって制作・運営されているウェブマガジンで,先月末の6月28日に最新号となる7月号が公開されています(「#5911. ウェブ月刊誌 Helvillian の7月号が公開されました」 ([2025-07-03-1]) を参照).その特集は「古英語を嗜もう」という,英語史ファンには実に魅力的なお題でした.この特集にあたり,編集部が古英語研究を専門とする小河さんに白羽の矢を立てたのは,しごく当然のことだったと想像します.そして,その期待に小河さんは120%で答えてくれました.寄稿された記事「主の祈りで味わう古英語の文体」は,まさしく専門家の手による圧巻のコンテンツです.

この記事は,聖書の中でも最も有名な祈祷文である Lord's Prayer 「主の祈り」を題材としています.しかし,単に古英語訳を紹介し,文法的な解説を施すといった入門的な内容にとどまるものではありません.古英語後期を代表する2人の偉大な散文作家,Ælfric と Wulfstan が残した「主の祈り」のヴァージョンを丹念に比較し,そこから両者の文体,ひいては思想や個性の違いまでをも鮮やかに炙り出すという,極めて専門的かつスリリングな論考となっています.これこそ英語史や英語文献学の研究のコンテンツです.

Ælfric と Wulfstan は,同時代に活躍しながらも,その文体は対照的でした.Ælfric は,明晰で整然とした,いわば「教育的」な文章を得意としていました.一方,小河さんが注目している Wulfstan は,頭韻 (alliteration) や同義語の反復を多用し,畳みかけるようなリズムで聴衆の感情に直接訴えかける,情熱的な説教で知られています.小河さんの記事の白眉は,この2人の文体の差異が,「主の祈り」というごく短い定型文の翻訳にさえ,いかに色濃く反映されているかを具体的に解き明かしている点にあります.特に Wulfstan のテキストにみられる畳語法や強調表現の分析は,小河さんの研究の真骨頂であり,読んでいて知的な興奮を禁じ得ません.

この記事のさらに驚くべき点を指摘したいと思います.専門性の高さにもかかわらず,徹頭徹尾 heldio リスナーを中心とする英語史の学習者を読者として強く意識し,非常に平易で分かりやすい言葉で書かれている点です.導入として日本語訳や近代英語訳から説き起こし,巧みな構成で読者を古英語の世界へと誘っています.途中,古英語LINEスタンプに言及するような遊び心も忘れていません.

上記の heldio 配信では「90分,いや180分の大学講義に匹敵する価値がある」と述べましたが,決して誇張ではありません.これほどの質の高いコンテンツが,誰でもアクセスできる形で公開されているというのは,望外の幸運といってよいです.(誰も信じてくれないかもしれませんが)信じられないことです.

Helvillian は私が直接関わっているウェブマガジンではありませんが,趣旨に賛同し,応援している雑誌です.その意味で,小河さんの Helvillian への今回のご寄稿を,本当に嬉しく思います.ありがとうございました!

2025-07-03 Thu

■ #5911. ウェブ月刊誌 Helvillian の7月号が公開されました [helwa][heldio][notice][helmate][helkatsu][helvillian][link][ogawashun][oe][hee]

月に1度のお祭りのお知らせです.先日6月28日,『月刊 Helvillian 〜ハロー!英語史』の2025年7月号(第9号)がウェブ公開されました.hellog 読者の方々にはもうお馴染みのことと思います.helwa のメンバー有志が毎月 note 上で制作している hel活 (helkatsu) の月刊ウェブマガジンです.創刊からあっという間に9号を数えることになりました.今回も質,量ともに充実のラインナップです.ゆっくりお読みいただき,じっくりお楽しみください.

今回の表紙を飾るのは,camin さんこと片山幹生さんがご提供くださったアイルランドの美しい写真です.静かなアイルランドの風景から,ヘルメイトの皆さんの熱い思いが伝わってきます.

今号の特集は「古英語を嗜む」です.古英語と聞くと,とっつきにくいと感じる方もいるかもしれません.現代英語とは異なる文字や文法をもつ言語ですから,それも当然です.しかし,今号の特集記事群を読めば,その奥深さと魅力が分かると思います.古英語の世界に足を踏み入れる良い機会になるはずです.

とりわけ注目していただきたいのは,heldio/helwa でもお馴染みの小河舜氏(上智大学)による特別寄稿です.「「主の祈り」で味わう古英語の文体」と題する書き下ろしの1編.古英語の専門家による古英語紹介ですので,たいへん貴重です.

また,「新企画 英語語源ハンドブック」も要注目です.『英語語源ハンドブック』の発売は6月18日のことでしたが,これに先だって,ヘルメイトの間では「ハンドブックにはあれこれの説明があるかもしれない,ないかもしれない」という予想遊びが繰り広げられていました.その遊びに関する記事をとりまとめたのが,この新企画のセクションです.

そのほか,今号には多彩な記事や寄稿文が満載です.ここですべてを紹介することはできませんが,寄稿者のお名前を列挙しておきましょう.ari さん,umisio さん,camin さん,川上さん,Grace さん,こじこじ先生,しーさん,ぷりっつさん,みさとさん,mozhi gengo さん,Taku さん(金田拓さん),lacolaco さん,り~みんさん,Lilimi さんです.

月刊 Helvillian は,helwa の活発なコミュニティ活動の賜物であり,「英語史をお茶の間に」届けるという目標を力強く推し進めてくれる存在です.helwa に参加している皆さんの活動の様子については,ぜひ Voicy プレミアムリスナー限定配信チャンネル「英語史の輪 (helwa)」のメンバーになり,とくとお聴きいただければ.

Helvillian のバックナンバーはこちらのページにまとまっています.hellog の helvillian タグのついた各記事もお薦めです.

この夏は hel活も熱いです.hellog 読者の皆さんには,ぜひ最新号の Helvillian を広めていただければと思います.

Helvillian 7月号については,Voicy heldio でもご紹介しています.「#1494. Helvillian 7月号が公開! --- 古英語を嗜もう」もお聴きください.

2025-05-12 Mon

■ #5859. 「AI古英語家庭教師」の衝撃 --- ぷりっつさんの古英語独学シリーズを読んで [heldio][helwa][oe][ai][hel_education][kochushoho]

heldio/helwa のコアリスナーであるぷりっつさんが,1週間ほど前から note 上で公開されている「Gemini 君と古英語を読む」シリーズは,私にとって衝撃的でした.最新のAI技術(今回は Gemini)が,これまで人間の先生による手ほどきが不可欠と思われてきた古英語学習のあり方を根底から覆しつつある現実を,まざまざと見せつけられたからです.

記事を拝読し,まず驚かされたのは,AIの精度の高さです.画像として取り込まれた古英語のテキスト(『古英語・中英語初歩』第2版)に含まれる æ や þ といった特殊文字を,AIが難なくテキスト化し,それをもとに,ぷりっつさんが次々とAIに問いかけながら疑問を解消していく様子は,まさに圧巻でした.ぷりっつさんの「AIとなら読めるかも」という直感が的中しました.このようなことが,ここまで早い段階で現実のものとなるとは,正直なところ,思いも寄りませんでした.

ぷりっつさんの,新しい技術に対する開かれた姿勢にも感銘を受けました.未知の領域である古英語の世界に,AIを積極的に活用しながら飛び込んでいく探究心は,研究者の私にとっても大いに刺激となりました.AIとの対話を通じて名詞の格変化や動詞の活用といった古英語の厄介な文法事項の理解を深めていっている様子が,記事のあちらこちらから伝わってきました.特に複合語 ġedæġhwāmlīcan の構造をAIと共に解き明かしていく過程には,私も引き込まれました.

今回のぷりっつさんの note 記事は,英語史を専門とする私自身の立ち位置についても深く考えさせられました.これまで英語史や古英語の研究者は,その専門的な知識や経験を活かして,当該分野の奥深さや魅力を伝えてきたという自負がありました.しかし,AIがこれほどの精度で学習者の疑問に答え,理解を助けることができるのであれば,研究者の役割は今後どのようになっていくのでしょうか.

ぷりっつさんの古英語学習体験談を読むにつけ,AIはもはや単なるツールではなく,すでに学習者のペースに合わせて知識を提供できる優秀な家庭教師であるといっても過言ではありません.もちろん,歴史・文化的背景など,現在のAIの知識だけでは捉えきれない側面も存在するでしょう.しかし,基本的な文法事項の習得といった初歩的な段階に関する限り,AIがきわめて効果的な助っ人となり得ることが明らかになりました.

学習,教育,研究において,何らかの形でAIの力を借りずにいくという選択肢は,早晩なくなるでしょう.重要なのは,AIの潜在的な価値を最大限に引き出し,より深く効率的な学びを実現する方法を模索することだと考えます.

ぷりっつさんの「Gemini 君と古英語を読む」シリーズは,まさにその可能性を示唆するものであり,今後の英語史の学習・教育・研究のあり方を考える上で,非常に重要な気づきとなりました.私もまた,この技術革新の波に乗り遅れることなく,AIとの新たな協働の方法を探求していきたいと考えています.AIという新たな道具を手にした私たちが,これからどのような地平を切り開いていくのか,今から楽しみです.

(以下,後記:2025/05/29(Thu))

後日,同趣旨で heldio 配信回もお届けしました.ぷりっつさんにも出演していただいての対談回です.「「#1460. 『古英語・中英語初歩』をめぐる雑談対談 --- 皐月収録回@三田より」」よりお聴きください.

・ 市河 三喜,松浪 有 『古英語・中英語初歩』第2版 研究社,1986年.

2025-05-11 Sun

■ #5858. 言語において変わるものと変わらないもの --- 「いのほた言語学チャンネル」より [inohota][youtube][language_change][historical_linguistics][notice][christianity][oe][loan_word][borrowing]

同僚の井上逸兵さん(慶應義塾大学)と運営している YouTube 「いのほた言語学チャンネル」は,原則として毎週水曜日と日曜日の午後6時に最新回が配信されています.多くの方にご覧いただいています.ありがとうございます.おかげさまで言語学系のチャンネルとして少しずつ知られるようになってきました(チャンネル登録者は目下1.42万人).

1週間前に配信された「#333. 変化したことより変化してないことの方がおもしろい!?新しい歴史言語学」が,思いのほかよく視聴されています.20分ほどの動画です.ぜひご視聴いただければ.

この回のテーマは,本ブログでも中心的に取り上げてきた言語変化 (language_change) です.言語は常に揺れ動き,時代とともにその姿を変えていきますが,その一方で,変化しない要素も存在します.今回の動画では,この言語変化のダイナミズムと,その陰に潜む不変性に焦点を当てました.

まず言語変化研究の現状を概観し,歴史言語学 (historical_linguistics) における伝統的な視点を紹介しています.一般的に,歴史言語学は,ある言語に注目し,その変遷の歴史を追う学問と捉えられています.しかし,言語の歴史を捉える上で重要なのは,変化した事象だけでなく,連綿と受け継がれてきた,つまり変わらなかった事象にも目を向けることであると論じました.

社会や文化が大きく変動する際に,言語もまた影響を受け,発音が変容したり,新しい語彙が生まれたり,既存の語の意味が変わったり,あるいは文法が変化したりします.しかし,その一方で,社会の変化にもかかわらず,従来の形式を保持し続ける言語項目も存在します.動画では,この「不変化」の重要性について,具体的な例を挙げながら議論を展開しました.

特に興味深い例として簡単に触れたのが,英語における God という単語です.古英語期,イングランドにキリスト教が浸透する過程で,多くのキリスト教関連用語がラテン語から導入されました.しかし,「神」という最も根源的な概念を表わす単語は,対応するラテン語の deus を借りるなどではなく,ゲルマン語起源の god が生き残りました.なぜ,他の多くの用語がラテン語によって置き換えられたにもかかわらず,この単語については現代に至るまでその形を保ち続けているのでしょうか.この問いを探ることは,単なる語源研究にとどまりません.言語共同体の文化や歴史に迫ろうとする試みでもあります.以下に関連する過去記事を挙げておきます.

・ 「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1])

・ 「#865. 借用語を受容しにくい語彙領域は何か」 ([2011-09-09-1])

・ 「#1619. なぜ deus が借用されず God が保たれたのか」 ([2013-10-02-1]),

・ 「#2663. 「オープン借用」と「むっつり借用」 (1)」 ([2016-08-11-1])

・ 「#3382. 神様を「大日」,マリアを「観音」,パライソを「極楽」と訳したアンジロー」 ([2018-07-31-1])

動画では,この他にも,言語(不)変化の背後にある力学について触れています.言語は,川の流れのように常に変化していきます.しかし,その川底には,時を超えて変わらない岩盤のような要素も存在しているのです.言語変化という現象を多角的に捉える視点を提供できたのであれば幸いです.

2025-05-08 Thu

■ #5855. ギリシア語由来の否定の接頭辞 a(n)- と英語の不定冠詞 a(n) の平行性 [senbonknock][sobokunagimon][heldio][article][greek][prefix][consonant][ogawashun][khelf][negative][oe]

5月28日に,khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)の協賛のもと,heldio にて小河舜さん(上智大学;X アカウント @scunogawa)とともに「英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック」をライヴでお届けしました.その様子をアーカイヴとしてすでに YouTube 版で公開していることは,先日の記事「#5851. 「英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック --- GW回 with 小河舜さん」のアーカイヴを YouTube で配信しました」 ([2025-05-04-1]) でお伝えした通りですが,数日遅れで heldio のアーカイヴとしても配信しました.音声だけで十分という方,ながら聴きしたいという方は,「#1439. 英語に関する素朴な疑問 千本ノック --- GW回 with 小河舜さん」よりご聴取ください.本編は65分ほどの長さです.

今回の千本ノックで取り上げた素朴な疑問は15件ありましたが,その5件目(本編の26分18秒辺りから)に注目します.質問の趣旨としては「不定冠詞 an/a の使い分け(an apple vs. a pen)の現象は,ギリシア語由来の否定の接頭辞 an-/a- の現象と同じですか?」というものでした.質問者からのこの高度な指摘にむしろ勉強になった旨,小河さんとライヴでも触れた通りです.

調べてみると,確かに両者において,an- が歴史的には本来の形態素ですが,後ろに母音(あるいは h)で始まる要素が後続する場合には,音便により当該形態素より n が脱落し,a- という異形態が用いられています.きれいに平行的といえます.

Webster の辞書の第3版に所収の A Dictionary of Prefixes, Suffixes, and Combining Forms によると,ギリシア語由来の否定の接頭辞 a-, an- について次のように記述があります.

2a- or an- prefix [L & Gk; L a-, an-, fr. Gk --- more at UN-]: not: without <achromatic> <asexual> --- used chiefly with words of Gk or L origin; a- before consonants other than h and sometimes even before h, an- before vowels and usu. before h <ahistorical> <anesthesia> <anhydrous>

このなかで示唆されている通り,このギリシア語由来の否定の接頭辞は,英語本来の否定の接頭辞 un- とも同根である.ついでに同辞典より un- の項目も覗いておこう.

1un- prefix [ME, fr. OE; akin to OHG un- un-, ON ō, ū-, Goth un-, L in-, Gk a-, an-, Skt a-, an- un-, OE ne not]

古英語の否定辞 ne もこれらと同根であるから,つまるところ not, never, no などとも通じることになる.

寄せていただいた素朴な疑問からの展開でした.たいへん勉強になりました!

2025-05-06 Tue

■ #5853. wange (cheek) --- 古英語のもう1つの中性弱変化名詞 [oe][neuter][noun][inflection][kochushoho]

昨日紹介した古い英語の入門書として名高い『古英語・中英語初歩』(第2版)の p. 12 に「弱変化の中性名詞は ēage 'eye' と ēare 'ear' の2語だけである」と触れられており,ēage の屈折表が次のように挙げられている.

| ēage (n.) 'eye' | ||

| 単数 | 複数 | |

| 主・対格 | ēage (-e) | ēagan (-an) |

| 属格 | ēagan (-an) | ēagena (-ena) |

| 与格 | ēagan (-an) | ēagum (-um) |

確かに古英語の中性弱変化名詞は一般にはこの2語のみとされる.しかし,細かく見れば,もう1つ顔の部位「頬」を表わす名詞 wange もこのタイプである.ただし,wange については強変化名詞としての側面もある,というのが先の2語とは異なるところだ.Campbell (§618) に次のようにある.

The only invariably weak neuters are ēage eye, ēare ear; wange, cheek (also þunwange), can be weak, but has also strong forms partly masc., partly fem.: g.s. wonges, d.s. -wange, n.p. wangas, -wonge, -wonga, g.p. -wonga; so (þun)wenġe, a strong form, has weak inflexion, d.s. -wenġan.

古英語の中性弱変化名詞は,正確には「目」と「耳」と「片頬」の3語といったところか.

・ 市河 三喜,松浪 有 『古英語・中英語初歩』第2版 研究社,1986年.

・ Campbell, A. Old English Grammar. Oxford: OUP, 1959.

2025-05-05 Mon

■ #5852. 市河三喜・松浪有(著)『古英語・中英語初歩』第2版(研究社,1986年) [review][oe][me][hel_education][heldio][toc][kochushoho]

日本語で書かれた古英語・中英語の教本として伝説的に著名な本です.本ブログでもたびたび本書を参照・引用してきました.絶版となっていますので古書店や図書館でしか入手できません.初版は1955年ですが,上の写真は第2版の1986年のものです.

1955年の「はしがき」 (vi) で,市河先生は次のように書かれています.

わたくしは日本人としてはどこまでも現代英語の研究に重きを置くべきであり,古代及び中世英語の研究は労多くして効少いものであると信ずる者であるが,しかし学問的立場においては古い時代の英語の正確な基礎的研究は必要なものであるから,出來るだけ一般の英語研究者にも参考になるように書いたつもりである.

本当に関心のある人だけ手に取って欲しい,というようなメッセージと読めます.なお,大先生の「労多くして効少い」とのお言葉については,僭越ながら「効少ない」ことはないと,私は考えています(「労多くして」は同意)!

古い英語の入門書としていまだに読み継がれている本と思われるので,以下に目次を記しておきます (vii--viii) .

はしがき

はしがき(第2版)

古英語初歩

I. 綴りと発音

II. 語形

II. 統語法

IV. 古英詩について

TEXTS

I. From the Gospels of St. Matthew

II. Early Britain

III. The Coming of the English

IV. Alfred's War with the Danes

V. Orpheus and Eurydice

VI. Pope Gregory

VII. Apollonius of tyre

VIII. Beowulf

XI. The Riddles

X. Deor

中英語初歩

I. 中英語の方言

II. 中英語の音韻

II. 語形変化

TEXTS

I. Peterborough Chronicle

II. The Ormulum

III. Ancrene Wisse

IV. The Owl and the Nightingale

V. Havelok the Dane

VI. Richard Rolle of Hampole

VII. The Bruce

VIII. The Pearl

XI. Piers the Plowman

X. Geoffrey Chaucer

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

GLOSSARY TO THE TEXTS

(1) OE

(2) OE

ちなみに,なぜこのタイミングで本書を紹介することになったのか? これについては1週間前の heldio 配信回「#1429. 古英語・中英語を学びたくなりますよね? --- 市河三喜・松浪有(著)『古英語・中英語初歩』第2版(研究社,1986年)」をお聴きいただければ.

・ 市河 三喜,松浪 有 『古英語・中英語初歩』第2版 研究社,1986年.

2025-04-15 Tue

■ #5832. なぜ古英語の語順規則は緩かったのか? --- 語順の2つの原理から考える [word_order][oe][pde][japanese][linearity][syntax][information_structure][article][cleft_sentence][passive][voice][discourse]

1週間前の火曜日に heldio にて「#1413. なぜ古英語の語順規則は緩かったのか?(年度初めの生配信のアーカイヴ)」を生配信し,土曜日にそれをアーカイヴとして配信しました.語順 (word_order) という,言語において一般的な話題なので,関心をもたれたのでしょうか,おかげさまでこの回は平均よりも多く聴取されています.ありがとうございます.

英語史の分野で「語順」といえば,現代英語では語順規則が厳しいのに,古英語では語順が比較的緩かったという対比が話題になります.当然ながら「それはなぜ?」という素朴な疑問が湧いてくるのではないでしょうか.今回の話題は,この疑問に直接答えるものではなく斜めからのアプローチではありますが,語順とは何かという根本的な問題には真正面から取り組んでいると思います.

以下に文章で要旨を示しますが,ぜひ臨場感のあるオリジナルの音声配信にてお聴きいただければと思います.

1. そもそも「語順」とは何か? --- 言語の線状性 (linearity)

私たちは,外国語学習,特に英語学習を通じて,語順の重要性を学びます.現代英語は SVO が基本であり,これを崩すと意味が変わったり,非文法的になったりすると教わってきました.例えば I eat a banana. が標準的であり,*Eat I a banana. や *A banana I eat. は通常許容されません(強調などの特殊な文脈は除きます).

一方,日本語では「私はバナナを食べる」 (SOV) が自然ですが,「バナナを私は食べる」 (OSV) や「食べる,私はバナナを」 (VSO) なども,不自然さはあるにせよ,文法的に間違いとは言い切れません.

では,なぜ言語には語順というものが存在するのでしょうか.それは,言語が音声(あるいは文字)を時間軸に沿って直線的に並べることによって成立しているからです.これを言語の線状性と呼びます.私たちの発音器官(とりわけ声帯)は基本的に1つしかないので,複数の単語を同時に発することはできません.したがって,単語を順番に並べるしかないのです.これは言語における避けられない制約であり,物理学における重力に相当するものと捉えることができます.

While the dog is running in the yard, the cat is sleeping on the hot carpet. (犬が庭で走っている間,猫はホットカーペットの上で寝ている)という文は,本来同時に起こっている出来事を表わしていますが,言語の線状性の制約から,どちらかの節を先に言わざるを得ません.もし仮に人間が2つの声帯をもち,同時に2つの単語を発することができたなら,言語の構造は全く異なっていたことでしょう.

2. 語順規則の2つの原理

単語を順番に並べなければならないという,語順の存在理由は分かりました.しかし,問題は「どのように並べるか」という語順規則です.世界の言語を見渡すと,この語順規則の背後には,大きく分けて2つの異なる原理が存在するように思われます.

(1) 文法上の語順規則

・ 文(センテンス)内部の要素(主語,動詞,目的語など)の配置を固定する原理

・ 要素の文法的な機能(主語なのか目的語なのか)を語順によって示す傾向が強い

・ 典型例:現代英語 (SVO),中国語 (SVO) など

・ 文法的な関係性が語順によって明確になる反面,語順の自由度は低い

(2) 文脈上の語順規則

・ 文(センテンス)よりも広い文脈(談話)における情報の流れを重視する原理.

・ 多くの場合,主題・テーマ・旧情報を先に提示し,それに続く形で叙述・レーマ・新情報を配置する傾向がある

・ 典型例:日本語,古英語

・ 情報の流れが自然になる一方,文内部の語順は比較的自由で「緩い」と見なされやすい.

日本語の「昔々あるところに,おじいさんとおばあさんがいました.おじいさんは山へ芝刈りに・・・」という語り出しを考えてみましょう.最初の文では,舞台設定の後,新情報である「おじいさんとおばあさん」が「が」を伴って現れます.次の文では,既知となった「おじいさん」が「は」(主題)を伴って文頭に来て,新しい情報(山へ芝刈りに行ったこと)が続きます.このように,日本語は文脈上の情報の流れ(主題→叙述,テーマ→レーマ,旧情報→新情報)を語順や助詞によって表現することを好む言語なのです.

3. 古英語は日本語型だった?

さて,ここで古英語に注目してみましょう.なぜ古英語の語順規則は緩かったのか? 答えは,古英語が現代英語のような「文法上の語順規則」を第1原理とする言語ではなく,むしろ日本語に近い「文脈上の語順規則」を重視する言語だったからです.

古英語では,文脈に応じて,主題や旧情報と見なされる要素を文頭に置き,新情報を後に続けるという語順が好まれました.そのため,文の内部構造だけを見ると,SVO も SOV も VSO も可能であり,現代英語話者の視点から見ると,語順が固定されておらず緩い,と感じられるわけです.しかし,それは「規則がない」わけではなく,異なる種類の原理に基づいているものと理解すべきものなのです.

4. 語順原理の転換と英語史上の変化

英語の歴史は,この「文脈上の語順規則」を重視するタイプから「文法上の語順規則」を重視するタイプへと,言語の基本的な性格が大きく転換した歴史であると捉えることができます.この転換は,中英語期に顕著になり,近代英語期にかけて固定化していきます.この大きな原理の転換は,単に語順だけでなく,英語の他の様々な文法項目にも連鎖的な影響を及ぼしました.

・ 冠詞 (article) の発達:古英語にも冠詞の萌芽はありましたが,現代英語ほど体系的なカテゴリーではありませんでした.旧情報を示す定冠詞 the や,新情報を示す不定冠詞 a/an が発達してきたのは,まさに情報構造 (information_structure) を語順以外の方法で示す必要性が高まったことと関連していると考えられます.

・ 強調構文 (cleft_sentence) の発達:古英語では,強調したい要素を比較的自由に文頭に移動させることが可能でした.しかし,語順が固定化されると,そのような移動が制限されます.その代わりとして,It is ... that ... のような強調構文が発達し,特定の要素を際立たせる機能をもつようになりました.

・ 受動態 (passive) の多用:古英語にも受動態は存在しましたが,使用頻度は現代英語ほど高くありませんでした.語順が固定化される中で,本来目的語となる要素(新情報になりやすい要素)を主題として文頭に置きたい場合に,受動態が便利な装置として頻繁に用いられるようになってきたものと考えられます.例えば,目的語を文頭に置く OSV の語順が使いにくくなった代わりに,目的語を主語にして文頭に置く受動態が好まれるようになった,という見方です.

5. まとめ

古英語の語順が現代英語から見て「緩い」のは,語順規則がなかったからではなく,現代英語とは異なる「文脈上の語順規則」という原理をより重視していたためです.この原理は,くしくも日本語と共通する部分が多くあります.英語の歴史は,この基本原理が大きく転換したダイナミックな過程であり,その影響は英文法の様々な側面に及んでいるのです.

古英語を学ぶ際には,現代英語の固定的な語順観から一旦離れ,「情報の流れ」という視点をもつことが,かえって理解の助けになるかもしれません.日本語母語話者にとっては,むしろ馴染みやすい側面もあるといえるでしょう.語順という切り口から,英語の奥深い歴史を探求してみるのも,おもしろいのではないでしょうか.

2025-03-04 Tue

■ #5790. 品詞とは何か? --- OED の "part of speech" を読む [oed][pos][terminology][linguistics][category][morphology][inflection][loan_translation][latin][oe][aelfric]

英語で「品詞」を表わす語句 part of speech (pos) は,どのように定義されているのか,そしていつ初出したのか.OED では part (NOUN1) の I.1.c. に part of speech が立項されている.それを引用しよう.

I.1.c. part of speech noun

Each of the categories to which words are traditionally assigned according to their grammatical and semantic functions. Cf. part of reason n. at sense I.1b.

In English there are traditionally considered to be eight parts of speech, i.e. noun, adjective, pronoun, verb, adverb, preposition, conjunction, interjection; sometimes nine, the article being distinguished from the adjective, or, formerly, the participle often being considered a distinct part of speech. Modern grammars often distinguish lexical and grammatical classes, the lexical including in particular nouns, adjectives, full verbs, and adverbs; the grammatical variously subdivided, often distinguishing classes such as auxiliary verbs, coordinators and subordinators, determiners, numerals, etc. See also word class n.

In quot. c1450 showing similar use of party of speech (compare party n. I).

[c1450 Aduerbe: A party of spech þat ys vndeclynyt, þe wych ys cast to a verbe to declare and fulfyll þe sygnificion [read sygnificacion] of þe verbe. (in D. Thomson, Middle English Grammatical Texts (1984) 6 (Middle English Dictionary))

c1475 How many partes of spech be ther? (in D. Thomson, Middle English Grammatical Texts (1984) 61 (Middle English Dictionary))

1517 For as moche as there be Viii. partes of speche, I wolde knowe ryght fayne What a nowne substantyue, is in his degre. (S. Hawes, Pastime of Pleasure (1928) v. 27)

. . . .

ここでは,品詞が文法的・意味的な機能によって分類されていること,英語では伝統的に8つ(場合によっては9つ)の品詞が認められてきたこと,品詞分類に準じて語類 (word class) という区分法があり語彙的クラスと文法的クラスなどに分けられることなどが記述されている.

最初例の例文は1450年頃からのものとなっているが,そこでは party of spech の語形であることに注意すべきである.さらにそれと関連して party of reason や part of reason という類義語も OED に採録されており,いずれも上に見える1450年頃の同じソース D. Thomson, Middle English Grammatical Texts より例文がとられていることも指摘しておこう.

また,part 単体として「品詞」を意味する用法があり,ラテン語表現のなぞりという色彩が濃いが,なんと早くも古英語期に文証されている(Ælfric の文法書).

OE Þry eacan synd met, pte, ce, þe man eacnað on ledenspræce to sumum casum þises partes. (Ælfric, Grammar (St. John's Oxford MS.) 107)

OE Þes part mæg beon gehaten dælnimend. (Ælfric, Grammar (St. John's Oxford MS.) 242)

part of speech という英語の語句は,古英語期に確認されるラテン文法の伝統的な用語遣いにあやかりつつ,中英語末期に現われ,その後盛んに用いられるようになったタームということになる.

品詞考については pos の関連記事,とりわけ以下の記事群を参照.

・ 「#5762. 品詞とは何か? --- 日本語の「品詞」を辞典・事典で調べる」 ([2025-02-04-1])

・ 「#5763. 品詞とは何か? --- ただの「語類」と呼んではダメか」 ([2025-02-05-1])

・ 「#5765. 品詞とは何か? --- Bloomfield の見解」 ([2025-02-07-1])

・ 「#5771. 品詞とは何か? --- 分類基準の問題」 ([2025-02-13-1])

・ 「#5772. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に意味を基準にした分類は可能か」 ([2025-02-14-1])

・ 「#5773. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に機能を基準にした分類の試み」 ([2025-02-15-1])

・ 「#5782. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に形態を基準にして分類するとどうなるか」 ([2025-02-24-1])

2025-01-10 Fri

■ #5737. 語源,etymology, veriloquium [etymology][terminology][greek][latin][oe][aelfric]

下宮忠雄(著)『歴史比較言語学入門』(開拓社,1999年)の第9章は「語源学」と題されている.『スタンダード英語語源辞典』の編者の1人でもあるし,思い入れの強い章かと想像される.下宮 (131) は第9章の冒頭でこう書いている.

言語学概論の1年間の授業が終わったあとで,何が印象に残っているか,何が面白かったかを試験問題の最後に問うと,語源と意味論という返事が圧倒的に多い.言語の研究は古代ギリシアに始まるが,そこでは,文法 (grammar) と語源 (etymology) が言語研究の2つの柱だった.

単語は一つ一つが歴史を持っている.語源 (etymology) は単語の本来の意味(これをギリシア語では etymon という)を探り,その歴史を記述する.したがって,意味論とも大いに関係をもっている.Cicero (キケロー)はギリシア語の etymologia を vēriloquium (vērum 「真実」,loquium 「語ること,ことば」)とラテン語に訳したが,修辞学者 Quintilianus [クウィンティリアーヌス]が etymologia にもどし,これが西欧諸国に伝わって今日にいたっている.grammar も etymology も2千年以上も前のギリシア人が創造した用語である.

「語源」を意味する語が,西洋語の歴史において変遷してきたというのは知らなかった.ギリシア語由来の etymology の響きは高尚で好きだが,キケローのラテン語 vēriloquium も味わいがある.いずれも英語本来語でいえば true word ほどである.そこに日本語あるいは漢語の「語源」に含まれる「みなもと」の意味要素が(少なくとも明示的には)含まれていない点がおもしろい.

ちなみに,ギリシア語由来ながらもラテン語に取り込まれていた ethymologia の単語は,古英語でも術語として受容されていたようで,OED によると Ælfric, Grammar (St. John's Oxford MS.) 293 に文証される.

Sum þæra [sc. divisions of the art of grammar] hatte ETHIMOLOGIA, þæ is namena ordfruma and gescead, hwi hi swa gehatene sind.

この時点ではあくまでラテン単語としての受容にすぎなかったとはいえ,英語文化において etymology は相当に長い歴史をもっているといえる.

(以下,後記:2025/01/12(Sun))

・ heltalk 「ラテン語で「語源」を意味する veriloquium もカッコいいですね」 (2025/01/10)

・ heldio 「#1322. word-lore 「語誌」っていいですよね」 (2025/01/11)

・ 下宮 忠雄 『歴史比較言語学入門』 開拓社,1999年.

・ 下宮 忠雄・金子 貞雄・家村 睦夫(編) 『スタンダード英語語源辞典』 大修館,1989年.

2024-12-23 Mon

■ #5719. ギリシア語が英語に影響を与えた3つの型 [greek][latin][borrowing][loan_word][lexicology][word_formation][derivation][compounding][oe][prestige][combining_form][morphology][scientific_name][scientific_english][link]

ギリシア語が英語に与えた語彙的影響は,ラテン語やフランス語のそれに比べると見劣りするように思われるかもしれないが,実際にはきわめて大きい.語彙そのものというより,むしろ語形成 (word_formation) に与えた影響が大きい,といったほうが適切かもしれない.とりわけ連結形 (combining_form) を用いた科学系の複合語の形成は,ギリシア語の偉大な貢献である.

Durkin (231) は,英語史におけるギリシア語の影響について,広い視野から次のように述べている.

Between C5 and C8-9, the Greek liberal arts education was revived, first by the Ostrogoths, later by the Carolingians, and Greek gained special prestige. Writers liberally sprinkled their woks with Greek words, many of which found their way into other languages of Europe, including Old English. Particularly noteworthy are the glossarial poems from Canterbury with words like apoplexis, liturgia, spasmus. Since then, Greek medical doctrine and the terms associated with it became the major part of English medical lexis . . . . More general scientific vocabulary from Greek has mushroomed since C18 . . . .

. . . .

Greek influence on English, then, is restricted to the lexicon, (limited) derivation, and compounding. Words entered English initially through Roman borrowings, then through direct borrowing from Ancient Greek writers, more recently through word formation (combining roots and affixes) in English.

ギリシア語の英語への影響には,3パターンあるいは3段階があったとまとめてよいだろう.

(1) ラテン語を経由して(中世から)

(2) 直接ギリシア語から(近代以降)

(3) ギリシア語「要素」を用いた英語内での造語(近代以降,特に18世紀以降;「科学用語新古典主義的複合語」 (neo-classical compounds) あるいは「英製希語」と呼んでもよいか)

いずれのパターンについても,ギリシア語に付された威信 (prestige) を反映して学術用語の造語が圧倒的である.関連する話題として,以下の hellog 記事も参照.

・ 「#516. 直接のギリシア語借用は15世紀から」 ([2010-09-25-1])

・ 「#552. combining form」 ([2010-10-31-1])

・ 「#616. 近代英語期の科学語彙の爆発」 ([2011-01-03-1])

・ 「#617. 近代英語期以前の専門5分野の語彙の通時分布」 ([2011-01-04-1])

・ 「#1694. 科学語彙においてギリシア語要素が繁栄した理由」 ([2013-12-16-1])

・ 「#3014. 英語史におけるギリシア語の真の存在感は19世紀から」 ([2017-07-28-1])

・ 「#3013. 19世紀に非難された新古典主義的複合語」 ([2017-07-27-1])

・ 「#3166. 英製希羅語としての科学用語」 ([2017-12-27-1])

・ 「#3179. 「新古典主義的複合語」か「英製羅語」か」 ([2018-01-09-1])

・ 「#3368. 「ラテン語系」語彙借用の時代と経路」 ([2018-07-17-1])

・ 「#4191. 科学用語の意味の諸言語への伝播について」 ([2020-10-17-1])

・ 「#4449. ギリシア語の英語語形成へのインパクト」 ([2021-07-02-1])

・ 「#5718. ギリシア語由来の主な接尾辞,接頭辞,連結形」 ([2024-12-22-1])

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2024-12-08 Sun

■ #5704. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第8回「英語,オランダ語と交流する」をマインドマップ化してみました [asacul][oe][dutch][mindmap][notice][kdee][etymology][hel_education][lexicology][vocabulary][heldio][link]

11月30日に,今年度の朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室でのシリーズ講座の第8回が開講されました.今回は「英語,オランダ語と交流する」と題して,英語史ではあまり注目されることのないオランダ語との言語接触について論じました.企画時には90分の講義に値するテーマかどうか自問していましたが,資料を準備する段になって,それが杞憂であることがわかりました.対面およびオンラインで,多くの方々にご参加いただき,ありがとうございました.

講座の内容を,markmap というウェブツールによりマインドマップ化して整理してみました(画像としてはこちらからどうぞ).受講された方は復習用に,そうでない方は講座内容を垣間見る機会としてご活用ください.

今回のシリーズ第8回については hellog と heldio の過去回でも取り上げていますので,ご参照ください.

・ hellog 「#5689. 11月30日(土)の朝カルのシリーズ講座第8回「英語,オランダ語と交流する」のご案内」 ([2024-11-23-1])

・ heldio 「#1277. 11月30日(土)の朝カル講座「英語,オランダ語と交流する」に向けて」 (2024/11/27)

また,シリーズ過去回のマインドマップについては,以下もご参照ください.

・ 「#5625. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第1回「英語語源辞典を楽しむ」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-09-20-1])

・ 「#5629. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第2回「英語語彙の歴史を概観する」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-09-24-1])

・ 「#5631. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第3回「英単語と「グリムの法則」」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-09-26-1])

・ 「#5639. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第4回「現代の英語に残る古英語の痕跡」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-10-04-1])

・ 「#5646. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第5回「英語,ラテン語と出会う」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-10-11-1])

・ 「#5650. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第6回「英語,ヴァイキングの言語と交わる」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-10-15-1])

・ 「#5669. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第7回「英語,フランス語に侵される」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-11-03-1])

次回の朝カル講座は.12月21日(土)17:30--19:00に開講予定です.第9回「英語,ラテン・ギリシア語に憧れる」と題して,主に初期近代英語期の古典語からの語彙借用に注目します.ご関心のある方は,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室の「語源辞典でたどる英語史」のページよりお申し込みください.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

2024-12-06 Fri

■ #5702. 古英語単語の意味変化 [oe][semantic_change][christianity][latin][metaphor][semantic_borrowing][contact]

いずれの言語においても,語彙の意味変化 (semantic_change) はきわめてありふれたタイプの言語変化であり,常に起こっている.このことは「#1955. 意味変化の一般的傾向と日常性」 ([2014-09-03-1]) でも論じた通りである.古英語の単語にも,多くの意味変化が起こっていたことだろう.

しかし,たくさんあったであろう古英語単語の意味変化を,文献学的に文証できるかどうかは別問題である.そもそも古英語の現存する資料は少ないため,ある単語の意味変化が古英語期中に起こったのかどうかを確かめるのに十分な情報が得られないことも多い.また,意味変化が確かに起こったと言えるためには,変化前と変化後の語義の各々の出典となるテキストが,時間的に前後していることを確言できなければならない.しかし,これにはテキスト年代や写本年代をめぐる諸問題がつきまとう.

このような事情で古英語期の単語の意味変化を論じるには困難が生じるのだが,それでもある程度言えることはある.アングロサクソン事典の "semantic change" の項目 (p. 415) より関連する箇所を引用する.

One area of vocabulary in which semantic change clearly took place during the Old English period is religious terminology. God 'God', heofon 'heaven', and helle 'hell', for example, necessarily adopted new meanings when they were applied to Christian rather than pagan concepts. Semantic change can also take the form of the development of a metaphorical meaning. In Old English this sometimes took place under the influence of Latin. Examples include tunge 'tongue', which was extended to mean 'language', possibly modelled on Latin lingua, and wit(e)ga 'wise man', used for 'prophet', perhaps influenced by Latin propheta. After the establishment of the Danelaw, OE terms also underwent semantic development under the influence of their Old Norse cognates. Modern English bloom 'flower' takes its form from either Old English bloma 'ingot of iron' or Old Norse blom 'flower', but its sense is clearly from Old Norse. In Old English, plog (ModE plough) was used for the measure of land which a yoke of oxen could plough in a day; its use with reference to an agricultural implement developed under the influence of Old Norse plogr. Similarly, Old English eorl 'man, warrior' (ModE earl) developed the sense 'chief, ruler of a shire' under the influence of Old Norse jarl.

ラテン語のキリスト教用語の影響による意味変化や古ノルド語の対応語の影響による意味変化が取り上げられているが,これは歴史言語学では意味借用 (semantic_borrowing) として言及されることの多いタイプのものである.他言語における当該の単語の意味が分かっており,かつ言語接触の時期などが特定できれば,このような意味変化の議論も可能になるということだ.歴史言語学や文献学の方法論上のトピックとしてもおもしろい.

・ Lapidge, Michael, John Blair, Simon Keynes, and Donald Scragg, eds. The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1999.

2024-12-02 Mon

■ #5698. royal we の起源と古英語・中英語 [greek][latin][royal_we][monarch][sociolinguistics][oe][me]

昨日の記事「#5697. royal we は「君主の we」ではなく「社会的不平等の複数形」?」 ([2024-12-01-1]) に引き続き「君主の we」 (royal_we) に注目する.術語としては "plural of majesty", "plural of inequality" なども用いられているが,いずれも1人称複数代名詞の同じ用法を指している.

Mustanoja (124) は,"plural of majesty" という用語を使いながら,ラテン語どころかギリシア語にまでさかのぼる用例の起源を示唆している.その上で,英語史における古い典型例として,中英語より「ヘンリー3世の宣言」での用例に言及していることに注目したい.

PLURAL OF MAJESTY. --- Another variety of the sociative plural (pluralis societatis) exists as the plural of majesty (pluralis majestatis), likewise characterised by the use of the pronoun of the first person plural for the first person singular. The plural of majesty originates in a living sovereign's habit of thinking of himself as an embodiment of the whole community. As the use of the plural becomes a mere convention, the original significance of this plurality tends to disappear. The plural of majesty is found in the imperial decrees of the later Roman Empire and in the letters of the early Roman bishops, but it can be traced to even earlier times, to Greek syntactical usage (cf. H. Zilliacus, Selbstgefühl und Servilität: Studien zum unregelmâssigen Numerusgebrauch im Griechischen, SSF-GHL XVIII, 3, Helsinki 1953). The plural of majesty is extensively used in medieval Latin. In OE it does not seem to be attested. OE royal charters, for example, have the singular (ic Offa þurh Cristes gyfe Myrcena kining; ic Æþelbald cincg, etc.). The plural of majesty begins to be used in ME. A typical ME example is the following quotation from the English proclamation of Henry III (18 Oct., 1258), a characteristic beginning of a royal charter: --- Henry, thurȝ Gode fultume king of Engleneloande, Lhoaverd on Yrloande, Duk on Normandi, on Aquitaine, and Eorl on Anjow, send igretinge to alle hise holde, ilærde ond ileawede, on Huntendoneschire: thæt witen ȝe alle þæt we willen and unnen þæt . . ..

引用中の "the English proclamation of Henry III (18 Oct., 1258)" (「ヘンリー3世の宣言」)での用例について,ナルホドと思いはする.しかし「#5696. royal we の古英語からの例?」 ([2024-11-30-1]) の最後の方で触れたように,この例ですら確実な royal we の用法かどうかは怪しいのである.この宣言の原文については「#2561. The Proclamation of Henry III」 ([2016-05-01-1]) を参照.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2024-12-01 Sun

■ #5697. royal we は「君主の we」ではなく「社会的不平等の複数形」? [terminology][oe][me][royal_we][monarch][personal_pronoun][pronoun][sociolinguistics][politeness][t/v_distinction][honorific][number][shakespeare]

数日間,「君主の we」 (royal_we) 周辺の問題について調べている.Jespersen に当たってみると「君主の we」ならぬ「社会的不平等の複数形」 ("the plural of social inequality") という用語が挙げられていた.2人称代名詞における,いわゆる "T/V distinction" (t/v_distinction) と関連づけて we を議論する際には,確かに便利な用語かもしれない.

4.13. Third, we have what might be called the plural of social inequality, by which one person either speaks of himself or addresses another person in the plural. We thus have in the first person the 'plural of majesty', by which kings and similarly exalted persons say we instead of I. The verbal form used with this we is the plural, but in the 'emphatic' pronoun with self a distinction is made between the normal plural ourselves and the half-singular ourself. Thus frequently in Sh, e.g. Hml I. 2.122 Be as our selfe in Denmarke | Mcb III. 1.46 We will keepe our selfe till supper time alone. (In R2 III. 2.127, where modern editions have ourselves, the folio has our selfe; but in R2 I. 1,16, F1 has our selues). Outside the plural of majesty, Sh has twice our selfe (Meas. II. 2.126, LL IV. 3.314) 'in general maxims' (Sh-lex.).

. . . .

In the second person the plural of social inequality becomes a plural of politeness or deference: ye, you instead of thou, thee; this has now become universal without regard to social position . . . .

The use of us instead of me in Scotland and Ireland (Murray D 188, Joyce Ir 81) and also in familiar speech elsewhere may have some connexion with the plural of social inequality, though its origin is not clear to me.

ベストな用語ではないかもしれないが,社会的不平等における「上」の方を指すのに「敬複数」 ("polite plural") などの術語はいかがだろうか.あるいは,これではやや綺麗すぎるかもしれないので,もっと身も蓋もなく「上位複数」など? いや,一回りして,もっとも身も蓋もない術語として「君主複数」でよいのかもしれない.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 2. Vol. 1. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: C. Winter's Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1922.

2024-11-30 Sat

■ #5696. royal we の古英語からの例? [oe][me][royal_we][monarch][personal_pronoun][pronoun][beowulf][aelfric][philology][historical_pragmatics][number]

「君主の we」 (royal_we) について「#5284. 単数の we --- royal we, authorial we, editorial we」 ([2023-10-15-1]) や「#5692. royal we --- 君主は自身を I ではなく we と呼ぶ?」 ([2024-11-26-1]) の記事で取り上げてきた.

OED の記述によると,古英語に royal we の古い例とおぼしきものが散見されるが,いずれも真正な例かどうかの判断が難しいとされる.Mitchell の OES (§252) への参照があったので,そちらを当たってみた.

§252. There are also places where a single individual other than an author seems to use the first person plural. But in some of these at any rate the reference may be to more than one. Thus GK and OED take we in Beo 958 We þæt ellenweorc estum miclum, || feohtan fremedon as referring to Beowulf alone---the so-called 'plural of majesty'. But it is more probably a genuine plural; as Klaeber has it 'Beowulf generously includes his men.' Such examples as ÆCHom i. 418. 31 Witodlice we beorgað ðinre ylde: gehyrsuma urum bebodum . . . and ÆCHom i. 428. 20 Awurp ðone truwan ðines drycræftes, and gerece us ðine mægðe (where the Emperor Decius addresses Sixtus and St. Laurence respectively) may perhaps also have a plural reference; note that Decius uses the singular in ÆCHom i. 426. 4 Ic geseo . . . me . . . ic sweige . . . ic and that in § ii. 128. 6 Gehyrsumiað eadmodlice on eallum ðingum Augustine, þone ðe we eow to ealdre gesetton. . . . Se Ælmihtiga God þurh his gife eow gescylde and geunne me þæt ic mote eoweres geswinces wæstm on ðam ecan eðele geseon . . . , where Pope Gregory changes from we to ic, we may include his advisers. If any of these are accepted as examples of the 'plural of majesty', they pre-date that from the proclamation of Henry II (sic) quoted by Bøgholm (Jespersen Gram. Misc., p. 219). But in this too we may include advisers: þæt witen ge wel alle, þæt we willen and unnen þæt þæt ure ræadesmen alle, oþer þe moare dæl of heom þæt beoþ ichosen þurg us and þurg þæt loandes folk, on ure kyneriche, habbeþ idon . . . beo stedefæst.

ここでは royal we らしく解せる古英語の例がいくつか挙げられているが,確かにいずれも1人称複数の用例として解釈することも可能である.最後に付言されている初期中英語からの例にしても,royal we の用例だと確言できるわけではない.素直な1人称複数とも解釈し得るのだ.いつの間にか,文献学と社会歴史語用論の沼に誘われてしまった感がある.

ちなみに,上記引用中の "the proclamation of Henry II" は "the proclamation of Henry III" の誤りである.英語史上とても重要な「#2561. The Proclamation of Henry III」 ([2016-05-01-1]) を参照.

・ Mitchell, Bruce. Old English Syntax. 2 vols. New York: OUP, 1985.

2024-11-22 Fri

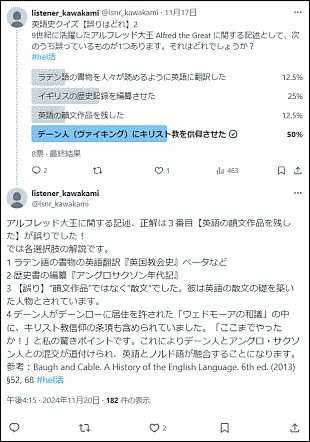

■ #5688. イングランドに定住したヴァイキングのキリスト教化 [helquiz][christianity][anglo-saxon][oe][old_norse][history][alfred][notice][link]

heldio/helwa リスナーの川上さんが,ご自身の X アカウントにて「英語史クイズ」を展開し始めています.第2問は(すでに解答と解説も公開されていますが)なかなか難しいこちらのクイズでした.

アルフレッド大王に関する記述として誤ったものを選んでください,という4択問題でした.その4つめの選択肢として「デーン人(ヴァイキング)にキリスト教を信仰させた」がありました.この選択肢は多くの回答者に選ばれていたのですが,解説を読めば分かる通り,これは正解ではないのです.つまり「デーン人(ヴァイキング)にキリスト教を信仰させた」は事実なのです.

厳密にいえば,この辺りの事情については複雑で不明なことも多いのですが,概ね事実であると考えてよい根拠や推論を,『ヴァイキングからノルマン人へ』より2カ所を引用したいと思います.まず第2章「ヴァイキング」の pp. 86--87 より.

しかしながらこのプロセス([引用者注]ヴァイキングのイングランド定住のプロセス)は,ヴァイキングをイングランド人にとっての単なる襲撃者から共生する隣人へと変えるにあたって特筆すべき意味をもっていた.移動を繰り返している段階のデーン人は,現地集団に敗北したときに,現地社会から課されるべき道徳上や商業上の慣習を受けいれることはできなかったであろう.しかしいったん彼らが土地を与えられて定住し,軍隊秩序ではなく現地の政治秩序にしたがって生活せざるをえなくなると,ある種の強制を受けいれることになる.宗教的強制はその最たるものであり,改宗がアルフレッド大王の主たる目的の一つであったことは明白である.彼ら異教を奉ずる厄介者が,洗礼を受け入れキリスト教的行動様式という道徳コードーー神と王への恭順ならびに隣人を愛する責務ーーを学んだのであれば,やがて平和な共生が実現することになるだろう.

私たちはすでに,アルフレッド王がガスルムに洗礼を受け入れるようにいかに要求したのかを知っている.彼は十数年後に同様の改宗をヘステンにも試みたが,うまくはいかなかった.ただしヘステンの息子たちは,アルフレッド王と〔王の娘婿でマーシアの主人〕エアルドールマン・エセルレッドが後押しすることによって改宗を受け入れた.このようにしてキリスト教徒となった指導者たちは,異教を打ち捨てるように彼らの部下たちにすすんで強制したかもしれない.それでは彼らは実際に実行したのだろうか.そしてこのような改宗プログラムを推し進める試みは,どれほどの成功を収めたのだろうか.キリスト教を受け入れるプロセスに関して,イングランド東部にはほとんど何の証拠もない.しかしキリスト教がスカンディナヴィア人にどのような影響を与えたのかを測る基準がないわけではない.第一の証拠は墓地である.異教の墓地が確認される範囲は限られており,イングルビーとレプトンを別にすれば南部と東部には皆無に近かった.そのため,八七〇年代にその地域に定住したものですら異教の埋葬慣行を維持することができなかったことがわかる.第二の証拠は銭貨である.イースト・アングリアには九〇〇年以前に聖エドマンドの銭貨が出現するが,それはおそらくデーン人支配者の一人の手になるものである.この事実は,エドマンド崇敬が彼の死から一世代もたたないうちに盛んになっていたという事実を伝えると同時に,「大軍勢」の指導者の子孫のあいだにもキリスト教の殉教者に対する尊崇の念が現れていたことを教えてくれる.そしてデーンローでも,一〇世紀半ばまでには教会組織が復活し機能していたと考えられる.この事実は,一〇世紀の前半にアルフレッド王の後継者たちがデーンローを征服することにより,デーン人系の新参の定住者がキリスト教信仰とその慣習を受容し現地社会に急速に同化することになったという説明の裏付けともなるだろう.

続いて,古英語期のキリスト教の浸透を論じる5章の p. 213 より引用します.

ヴァイキングたちがなぜ,どのようにキリスト教を受け入れたのかはよくわかっていない.政治的に強制されたから,というのが一つの答えではある.ガスルム〔「大軍勢」の王,八九〇年死去〕とその配下の主だった者たちは,八七八年の敗戦の後,アルフレッド王との間の和平の条件の一つとして洗礼を受けた.ダブリンとヨークを断続的に支配したオーラフ(アムリーブ)・クアラーン(九八一年死去)は,九四三年にイングランドで,エドマンド王を代父として洗礼を受けた.そして,オークニー伯シガードは,改宗したばかりのノルウェー王オーラフ・トリュッグヴァソンにより九九五年に洗礼を受けることを強制された.これら政治的リーダーたちの改宗は,彼らに従う者たちがそれに倣って改宗するという点で重要ではあった.しかしながら,定住者のあるコミュニティ全体に対して司牧を行うためには,その定住者たちに洗礼を施す司祭が必要であり,したがって教会の存在が必要であった.つまり,ヴァイキングの改宗は,それを可能にした教会組織の存在を暗示しているかに見える,ということである.しかしながら,逆説的に,ダブリンのようなアイルランドのスカンディナヴィア人飛び領地よりも,デーンロー地域東部の方が,改宗はより迅速に行われたのである.後者の教会組織の方が,アイルランド(ダブリン近郊も含む)のそれよりも,明らかにより混乱していたにもかかわらず,である.このことは,デーンロー地域では,司教座教会やミンスターが途絶や移転の憂き目を見た後も地方教会が存続しており,その司祭らが伝道活動を行った,ということを示すのかもしれない.またあるいは,ウェセックスから聖職者が送り込まれて,伝道活動を行ったのかもしれない.対照的に,アイルランドの聖職者たちには(そしてまた,ヴァイキングと同盟を結ぶことに何の痛痒も感じていなかったアイルランドの王たちにも),異教の「よそ者たち」を改宗させようという気がおそらくなかった.ノーサンブリアや,マーシア東部,そしてイースト・アングリアと比べて,それら「よそ者」の定住地域ははるかに狭く,その数も少なかったのである.加えるに,改宗時期の違いは,ヴァイキングたちが異教とキリスト教とのせめぎあいに対して,グループごとに異なった対応をしたのだということを示している,ということも言えよう.

アルフレッド大王が,ヴァイキングたち全体の改宗にどれだけ直接の影響を及ぼしたかを正確に測ることは難しいものの,相当なインパクトがあったことは確かのようです.今後の川上さんの英語史クイズにも注目していきましょう!

・ デイヴィス,ウェンディ(編)・鶴島 博和(日本語版監修・監訳) 『ヴァイキングからノルマン人へ』 オックスフォード ブリテン諸島の歴史 第3巻.慶應義塾大学出版会,2025年.

2024-11-03 Sun

■ #5669. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第7回「英語,フランス語に侵される」をマインドマップ化してみました [asacul][oe][french][norman_conquest][mindmap][notice][kdee][etymology][hel_education][lexicology][vocabulary][heldio][link]

1週間ほど前の10月26日に,今年度の朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室でのシリーズ講座の第7回が開講されました.今回は「英語,フランス語に侵される」と題して,主に中英語期の英仏語の言語接触に注目しました.90分の講義では足りないほど,話題が盛りだくさんでした.対面およびオンラインで,多くの方々にご参加いただき,ありがとうございました.

その盛りだくさんの内容を,markmap というウェブツールによりマインドマップ化して整理してみました(画像としてはこちらからどうぞ).受講された方は復習用に,そうでない方は講座内容を垣間見る機会としてご活用ください.