2017-12-12 Tue

■ #3151. 言語接触により言語が単純化する機会は先史時代にはあまりなかった [contact][history][anthropology][sociolinguistics][simplification]

昨日の記事「#3150. 言語接触は言語を単純にするか複雑にするか?」 ([2017-12-11-1]) で,言語接触の結果,言語は単純化するのか複雑化するのかという問題を取り上げた.Trudgill の結論としては,単純化に至るのは "high-contact, short-term post-critical threshold contact situations" の場合に多いということだが,このような状況は,人類史上あまりなかったことであり,新石器時代以降の比較的新しい出来事ではないかという.つまり,異なる言語の成人話者どうしが短期間の濃密な接触を経験するという事態は,先史時代には決して普通のことではなかったのではないか.Trudgill (313) 曰く,

I have argued . . . that we have become so familiar with this type of simplification in linguistic change --- in Germanic, Romance, Semitic --- that we may have been tempted to regard it as normal --- as a diachronic universal. However, it is probable that

widespread adult-only language contact is a mainly a post-neolithic and indeed a mainly modern phenomenon associated with the last 2,000 years, and if the development of large, fluid communities is also a post-neolithic and indeed mainly modern phenomenon, then according to this thesis the dominant standard modern languages in the world today are likely to be seriously atypical of how languages have been for nearly all of human history. (Trudgill 2000)

逆に言えば,おそらく先史時代の言語接触に関する常態は,昨日示した類型でいえば 1 か 3 のタイプだったということになるだろう.すなわち,言語接触は互いの言語の複雑性を保持し,助長することが多かったのではないかと.何やら先史時代の平和的共存と歴史時代の戦闘的融和とおぼしき対立を感じさせる仮説である.

・ Trudgill, Peter. "Contact and Sociolinguistic Typology." The Handbook of Language Contact. Ed. Raymond Hickey. 2010. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. 299--319.

・ Trudgill, Peter. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin, 2000.

2017-12-01 Fri

■ #3140. 16世紀イングランドではラテン語ではなく英語が印刷・出版された [printing][history]

「#3120. 貴族に英語の印刷物を売ることにした Caxton」 ([2017-11-11-1]) の記事で,Caxton がラテン語ではなく英語で書かれたものを印刷する方針を固めた経緯を紹介した.実際,Caxton の俗語印刷を重視する傾向は,続く16世紀中にも受け継がれ,その点でイングランドはヨーロッパのなかでも特異な印刷事情を示していた.前の記事でも述べたように,「16世紀の末にかけてイングランドで出版された書物のうち,英語以外の言語のものはわずか1割ほどだった」のである.

ペティグリー (559) に「1450--1600年にヨーロッパ全域で生産された印刷物の概要」と題する表がある.イングランドの俗語印刷偏重が際立っていることが分かるだろう.

俗語のもの ラテン語の学術書 フランス 40,500 35,000 イタリア 48,400 39,600 ドイツ 37,600 56,400 スイス 2,530 8,470 低地諸国 17,896 14,021 小計 146,926 153,491 全体に占める割合 81.99% 92.48% イングランド 13,463 1,664 スペイン 12,960 5,040 スカンジナヴィア 873 793 ヨーロッパ東部 4,980 4,980 小計 32,276 12,477 全体に占める割合 18.01% 7.52% 総計 179,202 165,968

当時のヨーロッパの中枢はフランス,イタリア,ドイツにあり,そこから外れる周辺部では概して俗語の印刷が多かったとはいえるが,その中でもイングランドは俗語比率が飛び抜けて高い.この状況は,端的にいえば島国根性とまとめられるかもしれない.しかし,そこには印刷・出版業界と政府の思惑が一致ししていたという社会的な要因もあったようだ.ペティグリー (411--12) を引用する.

イングランドは多くの点において,ヨーロッパでもっとも特異な書籍市場を形成していた.ざっと二〇〇万から三〇〇万というその総人口は,相当規模の英語の読者層を生み出した.国家としても成熟しており,スムーズに機能する統治組織を備えていた.ロンドンはヨーロッパでも有数の大都市であったし,オクスフォードとケンブリッジは最も古い大学に数えられた.それでもこの国の印刷産業は小規模なままであった.十六世紀にイングランドで出版された書物の総数はおよそ一万五〇〇〇点だが,この数字は低地諸国の半分である.またイングランドにおける出版業はほぼロンドンに限定されており,刷られる書物はほとんどが英語のものであった.ロンドンの出版業者たちが刊行するラテン語の書物は,ポーランドやボヘミアよりも少なかったのである.

このようなイングランドの出版産業の奇妙な特徴は,たがいに密接に関連していた.取引は政治の府たるロンドンにもっぱら限定されていたため,厳重な管理下におかれていた.生産物をコントロールすることも,さして難しくはなかった.ひとつには,業界が政府の介入に協力的であったせいでもある.イングランドの出版産業は,ロンドン書籍出版業組合によって支配されていた(一地方同業組合がこの種の国家的な統制機能を果たした唯一の事例である).ロンドンで営業する印刷所は比較的少数であったため,生活も保障されていた.したがってロンドンであれ田の場所であれ,非認可で営業する印刷企業を駆逐しようという政府の手助けをすることは,ロンドン書籍出版業組合の利益にかなってもいたのだ.産業構造は保守的であり,確実に売れるとわかっている書物を増刷して利益を上げることで満足していた.購入者の側もそんな状況に異を唱えるはずがなかった.というのもほしい本が国内で生産されなくても,アントウェルペンやフランスやドイツから,簡単に入手できてしまったからだ.こうした国際的な書籍取引を通じて,イングランドの読者は膨大な規模の学術書籍を集めた堂々たる蔵書を築き上げることができた.けれどもイングランドの出版業者たちはこの儲かる取引においては,ほとんど重要な役割を果たしていなかったのである.

馴れ合いで国内に閉じこもる島国根性が発揮された例といえそうだが,一方でこのことは,俗語たる英語が話し言葉としても書き言葉としても成長し,徐々に威信を高めるのに貢献したともいえる.

・ ペティグリー,アンドルー(著),桑木 幸司(訳) 『印刷という革命 ルネサンスの本と日常生活』 白水社,2015年.

2017-11-12 Sun

■ #3121. 「印刷術の発明と英語」のまとめ [slide][printing][history][link][hel_education][emode][reformation][caxton][latin][standardisation][spelling][orthography][asacul]

英語史における印刷術の発明の意義について,スライド (HTML) にまとめてみました.こちらからどうぞ.結論は以下の通りです.

1. グーテンベルクによる印刷術の「改良」(「発明」ではなく)

2. 印刷術は,宗教改革と二人三脚で近代国語としての英語の台頭を後押しした

3. 印刷術は,綴字標準化にも一定の影響を与えた

詳細は各々のページをご覧ください.本ブログの記事や各種画像へのリンクも豊富に張っています.

1. 印刷術の発明と英語

2. 要点

3. (1) 印刷術の「発明」

4. 印刷術(と製紙法)の前史

5. 関連年表

6. Johannes Gutenberg (1400?--68)

7. William Caxton (1422?--91)

8. (2) 近代国語としての英語の誕生

9. 宗教改革と印刷術の二人三脚

10. 近代国語意識の芽生え

11. (3) 綴字標準化への貢献

12. 「印刷術の導入が綴字標準化を推進した」説への疑義

13. 綴字標準化はあくまで緩慢に進行した

14. まとめ

15. 参考文献

16. 補遺: Prologue to Eneydos (#337)

他の「まとめスライド」として,「#3058. 「英語史における黒死病の意義」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-09-10-1]),「#3068. 「宗教改革と英語史」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-09-20-1]),「#3089. 「アメリカ独立戦争と英語」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-10-11-1]),「#3102. 「キリスト教伝来と英語」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-10-24-1]),「#3107. 「ノルマン征服と英語」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-10-29-1]) もどうぞ.

2017-11-10 Fri

■ #3119. 宗教改革,絶対王政,近代国語の形成,大航海時代を支えた印刷術 [printing][history][reformation][age_of_discovery]

16世紀初頭に印刷術が果たした文化的役割は計りしれない.『クロニック世界全史』 (431) は,標題にあるように,宗教改革,絶対王政,近代国語の形成,大航海時代を支えた技術としての印刷術に注目している.

印刷術が普及するにともない,パンフレット類にとどまらず宗教改革者の著作にも,ラテン語ではなく自国語が使われるようになった.ルターの場合,1518?21年の4年間にドイツ語の著作は56%だったが,22?26年の5年間には87%へと急増している.

さらに版数で比較すると,ドイツ語の著作の割合はそれぞれ74%と93%になり,ドイツ語版の需要がますます高まっていたことがわかる.儲けを考えた印刷業者も,わかりやすいドイツ語による出版を推進したことは明らかである.とくにルターの翻訳したドイツ語聖書は,近代ドイツ語を生みだすもとになったといわれる.

近代国語の誕生は,この時期ちょうど中央集権体制を築こうとしていた絶対君主にも好都合だった.一つの法典を制定し,それがどこの土地でも理解され,同一の裁決が下されることは,支配を有効にするため欠かすことができなかったからである.

こうして印刷術は大航海時代の動きにのって世界各地に広がり,支配の手段や文化伝達のために利用されるようになった.日本には1590年,天正遣欧使節を伴って帰国したイエズス会巡察師ヴァリニャーノによって印刷機が伝えられ,布教活動に力を発揮した.さらにこれらキリシタン版といわれる種々の印刷物は,当時の日本語の読みや意味を現代に伝える役割もはたしている.

近代国家の国語に基づく統治方式について,引用の第3段落にあるように「支配を有効にするために欠かすことができなかった」という点は重要だろう.「#2858. 1492年,スペインの栄光」 ([2017-02-22-1]) でも触れたように,近代国家(帝国)にとって「言語は帝国の武器」だったのである.印刷術が,言語や宗教などの文化面はもちろん,絶対王政や帝国主義といった政治面にも相当の波及効果をもたらしたことは否定できない.

関連して,「#2927. 宗教改革,印刷術,英語の地位の向上」 ([2017-05-02-1]),「#2937. 宗教改革,印刷術,英語の地位の向上 (2)」 ([2017-05-12-1]),「#3066. 宗教改革と識字率」 ([2017-09-18-1]),「#3100. イングランド宗教改革による英語の地位の向上の負の側面」 ([2017-10-22-1]) を参照.

・ 樺山 紘一,木村靖二,窪添 慶文,湯川 武(編) 『クロニック世界全史』 講談社,1994年.

2017-11-09 Thu

■ #3118. (無)文字社会と歴史叙述 [writing][history][anthropology][literacy]

『クロニック世界全史』 (246--47) に「無文字文化と文字文化」と題する興味深いコラムがあった.文化人類学では一般に,言語社会を文字社会と無文字社会に分類することが行なわれているが,この分類は単純にすぎるのではないかという.もう1つの軸として「歴史を必要とする」か否か,歴史叙述の意志をもつか否かというパラメータがあるのではないかと.以下,p. 247より長めに引用する.

歴史との関連でいえば,文字記録は歴史資料としてきわめて重要なものだが,人類史全体での文字使用の範囲からいっても,文字記録がのこっている度合いからいっても,文字記録のみによって探索できる歴史は限られている.考古学や民族〔原文ノママ〕学(物質文化・慣習・伝説や地名をはじめとする口頭伝承などの比較や民族植物学的研究)などの非文字資料にもとづく研究が求められる.文字を発明しあるいは採り入れて,出来事を文字によって記録することを必要とした,あるいはその意志をもった社会と,そうでなかった社会とは,歴史の相においてどのような違いを示すかが考えられなければならない.

出来事を文字を用いて記録する行為は,直接の経験をことばと文字をとおして意識化し,固定して,のちの時代に伝える意志をもつことを意味する.文字記録が,口頭伝承をはじめ生きた人間によって世代から世代へ受けつがれていく伝承と著しく異なるのは,出来事を外在化し固定する行為においてであるといえる.文字が図像のなかでも特別の意味をもっているのは,言語をとおして高度に分節化されたメッセージを「しるす」ことができるからである.

出来事を文字に「しるす」社会が,時の流れのなかに変化を刻み,変化がもたらすものを蓄積していこうとする意志をもっているのにたいし,伝承的社会,つまり集合的な仕来りを重んじる社会は,新しく起こった出来事も仕来りのなかに包みこみ,変化を極小化する傾向をもつといえる.このような伝承的社会は,日本をはじめいわゆる文字社会のなかでも無も時的な層としてひろく存在しており,これまで民俗学者の研究対象となってきた.

従来,多くの歴史学者が出来事の文字記録の誕生に歴史の発生を結びあわせ,アフリカ,オセアニアなど文字記録を生まなかった社会を「歴史のない」社会とみなしてきたのも,経験を意識化し,過去を対象化する意志に歴史意識の発生をみたからだろう.しかしこのような見方は,正しさを含んではいるが,あまりに一面的である.文字記録のない社会でも,王制をもつ社会のように,口頭伝承や太鼓による王朝史などの歴史語りを生んできた社会は,それなりに「歴史を必要とした」社会である.そして,そのような権力者が現在との関係で過去を意識化し,正当化して広報する必要のある社会では,王宮付きの伝承者や太鼓ことばを打つ楽師によって,文字記録に比べられる長い歴史語りの「テキスト」が作られ,伝えられてきた.

そのような過去との緊張ある対話を必要としない社会,つまり熱帯アフリカのピグミー(ムブティなど)や極北のエスキモー(イヌイットなど)のように,平等な小集団で狩猟・採集の遊動的な生活を営んできた社会は,無文字社会のなかでもまた「歴史を必要としなかった」社会ということができる.

このようにみてくると,文字社会,無文字社会という区別は絶対的なものではないことがわかる.いわゆる文字社会のなかにも無文字的な層があるのと同時に,無文字社会にも「歴史を必要とする」という限りで,文字社会と共通する部分があるのだから.このような二つの層,ないし部分は,時代とともに,すべてが文字性の側に吸収されていくのが望ましいとはいえない.人間のうちで,歴史とのつながりでいえば出来事を意識化して変化を生むことを志向する,文字性に発する部分と,「今までやってきたこと」のくりかえしに安定した価値を見いだす,無文字性に根ざす部分とは,あい補う関係で人類の社会をかたちづくってきたし,これからもかたちづくっていくだろう.

ここで述べられている,文字社会・無文字社会の区別と,歴史叙述の意志の有無という区別をかけ合わせると,次のような図式になるだろう.

| 「歴史を必要とする」社会 | 「歴史を必要としない」社会 | |

|---|---|---|

| 文字社会 | (1) 従来の「文字社会」 | (2) 歴史を記さない文字社会 |

| 無文字社会 | (3) 口頭のみの歴史伝承をもつ社会 | (4) 従来の「無文字社会」 |

従来の見方によれば,文字社会は (1) と同一視され,無文字社会は (4) と同一視されてきた.しかし,文字社会であっても歴史を記さない (2) のようなケースもあり得るし,無文字社会であっても歴史を伝える (3) のようなケースもある.切り口を1つ増やすことによって,従来の単純な二分法を批評できるようになる例だ.

無文字言語と関連して,「#748. 話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-05-15-1]),「#1277. 文字をもたない言語の数は?」 ([2012-10-25-1]),「#2618. 文字をもたない言語の数は? (2)」 ([2016-06-27-1]),「#2447. 言語の数と文字体系の数」 ([2016-01-08-1]),「#1685. 口頭言語のもつ規範と威信」 ([2013-12-07-1]) を参照.

・ 樺山 紘一,木村靖二,窪添 慶文,湯川 武(編) 『クロニック世界全史』 講談社,1994年.

2017-11-07 Tue

■ #3116. 巻物から冊子へ,パピルスから羊皮紙へ [history][writing][medium]

3--4世紀,書記の歴史において重大な2つの事件が起こった.巻物 (scroll) に代わって冊子 (codex) が,パピルス (papyrus) に代わって羊皮紙 (parchment) が現われたことである.書写材料とその使い方において劇的な変化がもたらされた.まず,「巻物→冊子」の重要性について,『印刷という革命』の著者ペティグリー (19--20) は次のように述べている.

巻物が冊子へと変わってゆくプロセスは段階的なものだったが,その変化がもたらしたインパクトたるや,数世紀後の印刷術の発明に勝るとも劣らぬほど大きなものであった.冊子が人気を博したのは,便利だったからである.紙の裏面にも書き込めるから,巻物より場所を取らない.それに破損しにくいし,もし傷ついた箇所があっても,簡単にページの差し替えができた.また蔵書は積み上げるか棚に並べるかして保管できるので,どの巻かすぐに見分けがついた.このように冊子状の本は,巻物と比べると,はるかに図書館(室)での収蔵と管理が容易だったのである.さらに冊子は,筆写のために分割もできたし,逆にさまざまなテクストを好みの順番で一冊にまとめることも,簡単にばらばらにして順番を入れ替えることもできた.要するに柔軟性と耐久性に富んでいたのである.

冊子は実用的であったばかりではない.巻物よりも,はるかに洗練された知的アプローチが可能だった.なにより,多様な読み方ができた.巻物だと,最初から順を追って読んでゆくよりほかないが,冊子ならぱらぱらとめくって拾い読みができる.読者はテクストのある箇所から別の箇所へと,望むままに移動してゆけるから,深い思索を展開できる.冊子は,物語ばかりでなく,知的な手段も提供したのである.

続けて,「パピルス→羊皮紙」についても言及している (20--21) .

冊子形式の本が成功した理由には,もろくて摩滅しやすいパピルスに替えて,より耐性のある記録媒体を採用したこともあった.パピルスの代わりに,徐々に羊皮紙が用いられるようになった.〔中略〕

羊皮紙はまた強度が高く,耐久性にも優れていたため,分量の多いテクストや,豊かな装飾を施した文章に用いることができた.

このような技術的革新により,書くこと,読むことの意義が変わっていった.また,古文書が朽ちずに現在まで存続することにもなった.まさに,歴史を可能ならしめた革新だったといえよう.

書写材料の話題については,「#2456. 書写材料と書写道具 (1)」 ([2016-01-17-1]) と「#2457. 書写材料と書写道具 (2)」 ([2016-01-18-1]) ,「#2465. 書写材料としての紙の歴史と特性」 ([2016-01-26-1]),「#2931. 新しきは古きを排除するのではなく選択肢を増やす」 ([2017-05-06-1]),「#2933. 紙の歴史年表」 ([2017-05-08-1]) も参照されたい.

・ ペティグリー,アンドルー(著),桑木 幸司(訳) 『印刷という革命 ルネサンスの本と日常生活』 白水社,2015年.

2017-11-04 Sat

■ #3113. アングロサクソン人は本当にイングランドを素早く征服したのか? [anglo-saxon][celtic][history][sociolinguistics][toponymy]

標記は,近年のブリテン島の古代史における論争の的となっている話題である.伝統的な歴史記述によれば,アングロサクソン人は5世紀半ばにイングランドを侵略し,原住民のブリトン人を根絶やしにするか,ブリテン島の周辺部へ追いやるかし,いわばアングロサクソン人の電撃的な圧勝だったという.しかし,近年はこの従来の説に対して修正的な見方が現われており,「電撃的な圧勝」ではなかったという説を見聞きする機会が増えた.

現実はアングロサクソン人によるもう少し穏やかな移住だったのではないかという見解については,ケルト研究の第1人者である原 (219) も,イングランドの考古学や地名学などの成果を参照するなどして,以下のように支持している.

従来,アングロサクソン人の侵入は,比較的短期間での大規模な組織的移住と考えられてきたが,現実はそうではなく,かなり長期にわたる,独立の小戦士団による来寇だった.五?六世紀の墳墓や葬制に関する考古学調査でうかがえるのは,小戦士団による主要なローマ街道沿いの,戦略的要地での点在的な定住地の形成であり,ついで河川に沿った内陸への広い拡大である.地名学の研究成果でも,たとえば「ハエスティンガス(ヘイスティングズ)」は,従来考えられてきたように「ハエストの一族,子孫たち」ではなく,「ハエストに従う人々」であり,「レアディンガス(レディング)」も「レアダに従う人々」である.つまり,アングロサクソンの初期集落に特徴的な「インガス語尾」の地名は,部族集団に由来するのではなく,小戦士団にもとづいているのである.

これも移住と伝播という歴史の基本的問題となるが,ローマに比べるとアングロサクソンの文化的権威は決して高くはなかった.したがってサクソン人の文化,その後の英語がブリテン島の支配的言語となっていくことについては,権威が拮抗的だとすれば,支配関係がキーポイントになる.つまり,サクソン人が支配権を握ることで,文化的にも覇権を獲得していくことになるのである.これはその後の歴史資料,物語でも確認される.

ここで,「文化的権威」と「支配関係」とを異なる社会言語学的パラメータと考えている点が注目に値する.この例において具体的にいえば,「文化的権威」とは技術,経済,学問,宗教などに関わる威信を指し,「支配関係」といえば政治や軍事などにかかわる優勢を指すとみなせるだろうか.文化軸と政治軸は,ともに社会的なパラメータではあるが,分けて考えることで見えてくることもありそうだ.

アングロサクソンのブリテン島の侵攻については,「#33. ジュート人の名誉のために」 ([2009-05-31-1]),「#389. Angles, Saxons, and Jutes の故地と移住先」 ([2010-05-21-1]),「#1013. アングロサクソン人はどこからブリテン島へ渡ったか」 ([2012-02-04-1]),「#2353. なぜアングロサクソン人はイングランドをかくも素早く征服し得たのか」 ([2015-10-06-1]),「#2443. イングランドにおけるケルト語地名の分布」 ([2016-01-04-1]),「#2493. アングル人は押し入って,サクソン人は引き寄せられた?」 ([2016-02-23-1]),「#2900. 449年,アングロサクソン人によるブリテン島侵略」 ([2017-04-05-1]),「#3094. 449年以前にもゲルマン人はイングランドに存在した」 ([2017-10-16-1]) を参照.

・ 原 聖 『ケルトの水脈』 講談社,2007年.

2017-10-30 Mon

■ #3108. ノルマン征服がなかったら,英語は・・・? [hel_education][history][loan_word][spelling][stress][rsr][gsr][rhyme][alliteration][gender][inflection][norman_conquest]

「#119. 英語を世界語にしたのはクマネズミか!?」 ([2009-08-24-1]) や「#3097. ヤツメウナギがいなかったら英語の復権は遅くなっていたか,早くなっていたか」 ([2017-10-19-1]) に続き,歴史の if を語る妄想シリーズ.ノルマン征服がなかったら,英語はどうなっていただろうか.

まず,語彙についていえば,フランス借用語(句)はずっと少なく,概ね現在のドイツ語のようにゲルマン系の語彙が多く残存していただろう.関連して,語形成もゲルマン語的な要素をもとにした複合や派生が主流であり続けたに違いない.フランス語ではなくとも諸言語からの語彙借用はそれなりになされたかもしれないが,現代英語の語彙が示すほどの多種多様な語種分布にはなっていなかった可能性が高い.

綴字についていえば,古英語ばりの hus (house) などが存続していた可能性があるし,その他 cild (child), cwic (quick), lufu (love) などの綴字も保たれていたかもしれない.書き言葉における見栄えは,現在のものと大きく異なっていただろうと想像される.<þ, ð, ƿ> などの古英語の文字も,近現代まで廃れずに残っていたのではないか (cf. 「#1329. 英語史における eth, thorn, <th> の盛衰」 ([2012-12-16-1]) や「#1330. 初期中英語における eth, thorn, <th> の盛衰」 ([2012-12-17-1])) .

発音については,音韻体系そのものが様変わりしたかどうかは疑わしいが,強勢パターンは現在と相当に異なっていたものになっていたろう.具体的にいえば,ゲルマン的な強勢パターン (Germanic Stress Rule; gsr) が幅広く保たれ,対するロマンス的な強勢パターン (Romance Stress Rule; rsr) はさほど展開しなかったろうと想像される.詩における脚韻 (rhyme) も一般化せず,古英語からの頭韻 (alliteration) が今なお幅を利かせていただろう.

文法に関しては,ノルマン征服とそれに伴うフランス語の影響がなかったら,英語は屈折に依拠する総合的な言語の性格を今ほど失ってはいなかったろう.古英語のような複雑な屈折を純粋に保ち続けていたとは考えられないが,少なくとも屈折の衰退は,現実よりも緩やかなものとなっていた可能性が高い.古英語にあった文法性は,いずれにせよ消滅していた可能性は高いが,その進行具合はやはり現実よりも緩やかだったに違いない.また,強変化動詞を含めた古英語的な「不規則な語形変化」も,ずっと広範に生き残っていたろう.これらは,ノルマン征服後のイングランド社会においてフランス語が上位の言語となり,英語が下位の言語となったことで,英語に遠心力が働き,言語の変化と多様化がほとんど阻害されることなく進行したという事実を裏からとらえた際の想像である.ノルマン征服がなかったら,英語はさほど自由に既定の言語変化の路線をたどることができなかったのではないか.

以上,「ノルマン征服がなかったら,英語は・・・?」を妄想してみた.実は,これは先週大学の演習において受講生みんなで行なった妄想である.遊び心から始めてみたのだが,歴史の因果関係を確認・整理するのに意外と有効な方法だとわかった.歴史の if は,むしろ思考を促してくれる.

2017-10-29 Sun

■ #3107. 「ノルマン征服と英語」のまとめスライド [slide][norman_conquest][history][french][loan_word][link][hel_education][asacul]

英語史におけるノルマン征服の意義について,スライド (HTML) にまとめてみました.こちらからどうぞ.

これまでも「#2047. ノルマン征服の英語史上の意義」 ([2014-12-04-1]) を始め,norman_conquest の記事で同じ問題について考えてきましたが,当面の一般的な結論として,以下のようにまとめました.

1. ノルマン征服は(英国史のみならず)英語史における一大事件.

2. 以降,英語は語彙を中心にフランス語から多大な言語的影響を受け,

3. フランス語のくびきの下にあって,かえって生き生きと変化し,多様化することができた

詳細は各々のページをご覧ください.本ブログ内のリンクも豊富に張っていますので,適宜ジャンプしながら閲覧すると,全体としてちょっとした読み物になると思います.また,フランス語が英語に及ぼした(社会)言語学的影響の概観ともなっています.

1. ノルマン征服と英語

2. 要点

3. (1) ノルマン征服 (Norman Conquest)

4. ノルマン人の起源

5. 1066年

6. ノルマン人の流入とイングランドの言語状況

7. (2) 英語への言語的影響

8. 語彙への影響

9. 英語語彙におけるフランス借用語の位置づけ (#1210)

10. 語形成への影響 (#96)

11. 綴字への影響

12. 発音への影響

13. 文法への影響

14. (3) 英語への社会的影響 (#2047)

15. 文法への影響について再考

16. まとめ

17. 参考文献

18. 補遺1: 1300年頃の Robert of Gloucester による年代記 (ll. 7538--47) の記述 (#2148)

19. 補遺2: フランス借用語(句)の例 (#1210)

他の「まとめスライド」として,「#3058. 「英語史における黒死病の意義」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-09-10-1]),「#3068. 「宗教改革と英語史」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-09-20-1]),「#3089. 「アメリカ独立戦争と英語」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-10-11-1]),「#3102. 「キリスト教伝来と英語」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-10-24-1]) もご覧ください.

2017-10-27 Fri

■ #3105. tithe と tenth [numeral][doublet][history][reformation]

標題の2語は,いずれも「10分の1」が原義であり,「十分の一税」の語義を発展させた.語源的には密接な関係にある2重語 (doublet) である(「#1724. Skeat による2重語一覧」 ([2014-01-15-1]) の記事,および American Heritage Dictionary より tithe の蘊蓄を参照).

昨日の記事「#3104. なぜ「ninth(ナインス)に e はないんす」かね?」 ([2017-10-26-1]) で,ninth に相当する古英語の語形が,2つ目の n の脱落した nigoða という形であると述べた.tenth に関しても同様であり,基数詞 tīen(e) (West-Saxon), tēn(e) (Anglian)に対して序数詞では n が落ちて tēoþa (West-Saxon), tēogoþa (Anglian) などと用いられた.後者 Anglia 方言の tēogoþa が後に音過程を経て tithe となり,近代英語以降に受け継がれた(MED より tīthe (n.(2)) を参照).

一方,tenth は,初期中英語で基数詞の形態をもとに規則的に形成された新たな形態である(MED より tenth(e を参照).

tithe は「十分の一税」を意味する名詞としては,1200年ころに初出する.中世ヨーロッパでは,5世紀以降,キリスト教会が信徒に収入の十分の一の納税を要求するようになっていたが,8世紀からはフランク王国で全キリスト教徒に課せられる税となった.教会が教区の農民から収穫物の十分の一を強制的に徴収するようになったのである.9世紀以降,その徴収権は教会からしばしば世俗領主へと渡り,18--19世紀に廃止されるまで続いた.

ややこしいことに,イングランドでは,ローマ・カトリック教会の聖職者がローマ教皇に対する上納金も「十分の一税」(しかし今度は tenth)と呼ばれていたが,宗教改革の過程で,Henry VII は教皇にではなく国王に納めさせるように要求し,制度として定着した.さらに,都市部に課される議会課税も tenth (十分の一税)と呼ばれたので,一層ややこしい(水井,p. 16).

我が国の消費税も10%になるということであれば,これは tithe と呼ぶべきか tenth と呼ぶべきか・・・.

・ 水井 万里子 『図説 テューダー朝の歴史』 河出書房,2011年.

2017-10-24 Tue

■ #3102. 「キリスト教伝来と英語」のまとめスライド [slide][christianity][history][bible][runic][alphabet][latin][loan_word][link][hel_education][asacul]

英語史におけるキリスト教伝来の意義について,まとめスライド (HTML) を作ったので公開する.こちらからどうぞ.大きな話題ですが,キリスト教伝来は英語に (1) ローマン・アルファベットによる本格的な文字文化を導入し,(2) ラテン語からの借用語を多くもたらし,(3) 聖書翻訳の伝統を開始した,という3つの点において,英語史上に計り知れない意義をもつと結論づけました.

1. キリスト教伝来と英語

2. 要点

3. ブリテン諸島へのキリスト教伝来 (#2871)

4. 1. ローマン・アルファベットの導入

5. ルーン文字とは?

6. 現存する最古の英文はルーン文字で書かれていた

7. 古英語アルファベット

8. 古英語の文学 (#2526)

9. 2. ラテン語の英語語彙への影響

10. 外来宗教が英語と日本語に与えた言語的影響の比較 (#206)

11. 3. 聖書翻訳の伝統の開始

12. 多数の慣用表現

13. まとめ

14. 参考文献

15. 補遺1: Beowulf の冒頭の11行 (#2893)

16. 補遺2:「主の祈り」の各時代のヴァージョン (#1803)

他の「まとめスライド」として,「#3058. 「英語史における黒死病の意義」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-09-10-1]),「#3068. 「宗教改革と英語史」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-09-20-1]),「#3089. 「アメリカ独立戦争と英語」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-10-11-1]) もご覧ください.

2017-10-19 Thu

■ #3097. ヤツメウナギがいなかったら英語の復権は遅くなっていたか,早くなっていたか [reestablishment_of_english][monarch][history][norman_conquest][hundred_years_war]

昨日の記事「#3096. 中英語期,英語の復権は徐ろに」 ([2017-10-18-1]) に引き続き,英語の復権のスピードについての話題.

William I が1066年のノルマン征服で開いたノルマン朝は,英語とフランス語の接触をもたらした.続いて,Henry I から Stephen の時代の政治的混乱を経た後に,1154年に Henry II が開いたプランタジネット朝は,イングランド全体とフランスの広大な部分からなるアンジュー帝国を出現させた.英仏海峡をまたいで両側に領土をもつという複雑な統治形態により,イングランドの言語を巡る状況も複雑化した.それ以降,英語は,フランス語と密接な関係を持ち続けずに存在することがもはやできなくなったといえるからだ.その後も14--15世紀の百年戦争に至るまで厄介な英仏関係が続いたが,関係の泥沼化がこのように進んでいなければ,英語とフランス語の関係も,そしてイングランドにおける英語の復権も,別のコースをたどっていた可能性が高い.

このようなことを考えていたところに,Henry I と Stephen の息子 Eustace がヤツメウナギ (lamprey) を食して亡くなったという逸話を読んだ(石井,p. 41).歴史の if の妄想ということで,ツイッターで独りごちた.以下,ツイッター口調で(実際にツイートなので)再現してみたい.

同じ食用魚でもヤツメウナギ (lamprey) とウナギ (eel) は生物学的にはまったくの無関係.名前や姿形でだまされてはいけない.

ヤツメウナギ (lamprey) を食し,中毒でポックリ逝ったノルマン朝の King Henry I と,King Stephen の息子 Eustace の2人.ノルマン朝の王族って,そんなにヤツメウナギ好きだったの?

ヤツメウナギ (lamprey) で Eustace がやられなかったら,Henry II に王位が渡らず,プランタジネット朝が開かれなかったかも.すると,イングランドはフランスとさほど摩擦せず,国内の英語の復権はもっと早かったかも.その後の英語史はどうなっていたことか?

プランタジネット朝の開祖 Henry II のフランスの領土保有により,フランスとの泥沼の関係が持続したわけで,それで国内の英語の復権が遅くなった.後に,英語はその遅れの焦りによる「火事場の馬鹿力」的な瞬発力で国内での復権を一気になしとげ,さらに国外へ飛躍できたと考えられる.

結論として,ヤツメウナギがいなかったら,むしろ英語はもう少し長く停滞していたかも!? そして,後に世界語となる機会を逸していたかも!!?? 以上.

「ヤツメウナギが英語を世界語にした」張りの「ハッタリの英語史?歴史の if シリーズ(仮称)」より,「#119. 英語を世界語にしたのはクマネズミか!?」 ([2009-08-24-1]) もどうぞ.

Henry II は医者の再三の注意を無視してヤツメウナギを大量に食べ続けたというから,相当の好物だったのだろう.歴史は,たやすく偶然に左右されるものかもしれない.

こちらからツイッターもどうぞ.フォローは\@chariderryu のツイッターをフォロー.

・ 石井 美樹子 『図説 イギリスの王室』 河出書房,2007年.

2017-10-18 Wed

■ #3096. 中英語期,英語の復権は徐ろに [reestablishment_of_english][history][toc][hundred_years_war]

似たようなタイトルの記事「#706. 14世紀,英語の復権は徐ろに」 ([2011-04-03-1]) を以前に本ブログで書いているが,「14世紀」を今回のタイトルのように「中英語期」(1100--1500年)と入れ替えても,さして問題はない.「#131. 英語の復権」 ([2009-09-05-1]) で示した年表や,その他の reestablishment_of_english の記事で論じてきたように,イングランドにおける英語の地位の回復は,3世紀ほどのスパンでとらえるべき長々とした過程だった.

Baugh and Cable の英語史概説書の第6章は "The Reestablishment of English, 1200--1500" と題されており,この長々とした過程を扱っているのだが,最初にこの箇所を初めて読んだときに,なんてダラダラとして読みにくい章かと思ったものである.1200--1500年のイングランドにおける英語とフランス語を巡る言語事情とその変化が説明されていくのだが,英語の復権がようやく2歩ほど進んだかと思えば,フランス語のしぶとい権威保持のもとで今度は1歩下がるといった,複雑な記述が続くのだ.英語の復権とフランス語の権威保持という2つの相反する流れが並行して走っており,実にわかりづらい.

改めて Baugh and Cable の第6章を読みなおしたところ,結局のところ同章の冒頭に近い文章が,この時代の内容を最もよくとらえているということが分かった.

As long as England held its continental territory and the nobility of England were united to the continent by ties of property and kindred, a real reason existed for the continued use of French among the governing class in the island. If the English had permanently retained control over the two-thirds of France that they once held, French might have remained permanently in use in England. But shortly after 1200, conditions changed. England lost an important part of its possessions abroad. The nobility gradually relinquished their continental estates. A feeling of rivalry developed between the two countries, accompanied by an antiforeign movement in England and culminating in the Hundred Years' War. During the century and a half following the Norman Conquest, French had been not only natural but also more or less necessary to the English upper class; in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, its maintenance became increasingly artificial. For a time, certain new factors helped it to hold its ground, socially and officially. Meanwhile, however, social and economic changes affecting the English-speaking part of the population were taking place, and in the end numbers told. In the fourteenth century, English won its way back into universal use, and in the fifteenth century, French all but disappeared. (122)

先に,この時代の英語の復権は2歩進んで1歩下がるかのようだと表現したが,Baugh and Cable の第6章を構成する第93--110節のいくつかのタイトルを「英語の復権を後押しした要因」と「フランス語の権威を保持した要因」とに粗く,緩く2分すると,次のようになる.

[ 英語の復権を後押しした要因 ]

94. The Loss of Normandy

95. Separation of the French and English Nobility

97. The Reaction against Foreigners and the Growth of National Feeling

101. Provincial Character of French in England

102. The Hundred Years' War

103. The Rise of the Middle Class

104. General Adoption of English in the Fourteenth Century

105. English in the Law Courts

106. English in the Schools

107. Increasing Ignorance of French in the Fifteenth Century

109. The Use of English in Writing

[ フランス語の権威を保持した要因 ]

96. French Reinforcements

98. French Cultural Ascendancy in Europe

100. Attempts to Arrest the Decline of French

108. French as a Language of Culture and Fashion

節の数の比からいえば,英語の復権は3歩進んで1歩下がるほどのスピードで推移したことになろうか.

Baugh and Cable の目次については,「#2089. Baugh and Cable の英語史概説書の目次」 ([2015-01-15-1]),「#3091. Baugh and Cable の英語史概説書の目次よりランダムにクイズを作成」 ([2017-10-13-1]) を参照.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2017-10-16 Mon

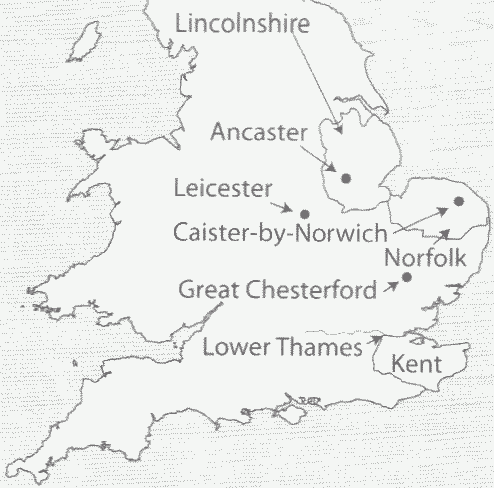

■ #3094. 449年以前にもゲルマン人はイングランドに存在した [anglo-saxon][history][archaeology][map]

標題について,「#2493. アングル人は押し入って,サクソン人は引き寄せられた?」 ([2016-02-23-1]) で, Gramley (16) の "Pre-Conquest Germanic cemeteries" と題する地図を示した(以下に再掲).

5世紀初め,そしておそらくもっと古くから,ゲルマン人がイングランドにいたことが考古学的な証拠から示唆されるが,この辺りの事情について,Gramley (16--17) の説明を引用しておきたい.

The earliest evidence we have of Germanic settlement in Britain consists of the Anglo-Saxon cemeteries and settlements in the region between the Lower Thames and Norfolk. Others possibly lay in Lincolnshire and Kent. In Caister-by-Norwich there was a large cremation cemetery outside the town dating from about 400. Similar settlements were found near Leicester, Ancaster, and Great Chesterford. One of the most likely explanations for these settlements, virtually always outside the city walls, was that the Germanic invaders were invited there to protect the British settlements, especially after the Romans withdrew. Much as in other western provinces, the Empire relied on barbarian troops and officers from the late third century on.

The formal end of Roman rule by 410 did not mean the end of all efforts to protect Britain from external attacks, the most serious of which came from the Scots and the Picts . . . to the north and the sea-borne Saxons among others. It may well have been that the British leaders continued to use Germanic troops after 410 and perhaps even to increase their numbers. For the Germanic newcomers it was probably of no importance who recruited them. They were simply doing what their fathers before them had done. However, without any central power to coordinate defenses the Germanic forces would soon have realized they had a free hand to do as they wished. Soon more would be coming from the Continental coast near the Elbe and Weser estuaries (the Saxons), from Schleswig-Holstein, especially the region of Angeln (the Angels (sic)), from northern Holland (the Frisians), and probably from Jutland (the Jutes).

伝説によれば,449年に Hengist と Horsa というジュート人の兄弟が,ブリトン人に呼ばれる形でイングランドに足を踏み入れたとされるが,実際にはすでにゲルマン人はその数十年も前からイングランドに存在しており,5世紀半ばには,大陸から仲間を呼び寄せるのに,ある意味で準備万端であったとも言えるのである.ゲルマン人のイングランドへの侵攻は,伝説が示すほど電撃的なものではなかったと考えられる.

関連して,「#33. ジュート人の名誉のために」 ([2009-05-31-1]),「#389. Angles, Saxons, and Jutes の故地と移住先」 ([2010-05-21-1]),「#1013. アングロサクソン人はどこからブリテン島へ渡ったか」 ([2012-02-04-1]),「#2353. なぜアングロサクソン人はイングランドをかくも素早く征服し得たのか」 ([2015-10-06-1]) の記事も参照されたい.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

2017-10-11 Wed

■ #3089. 「アメリカ独立戦争と英語」のまとめスライド [slide][ame][ame_bre][history][link][hel_education][asacul]

(アメリカ)英語史におけるアメリカ独立戦争の意義について,まとめスライド (HTML) を作ったので公開する.こちらからどうぞ.

1. アメリカ独立戦争と英語

2. 要点

3. アメリカ英語の言語学的特徴

4. アメリカ英語の社会言語学的特徴

5. アメリカの歴史(猿谷の目次より)

6. 「アメリカ革命」 (American Revolution)

7. アメリカ英語の時代区分 (#158)

8. 独立戦争とアメリカ英語

9. ノア・ウェブスター(肖像画; #3087)

10. ウェブスター語録

11. ウェブスターの綴字改革

12. まとめ

13. 参考文献

他の「まとめスライド」として,「#3058. 「英語史における黒死病の意義」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-09-10-1]),「#3068. 「宗教改革と英語史」のまとめスライド」 ([2017-09-20-1]) もご覧ください.

2017-10-09 Mon

■ #3087. Noah Webster [biography][webster][ame][spelling_reform][american_revolution][history][lexicography][dictionary]

象徴的な意味でアメリカ英語を作った Noah Webster (1758--1843) について,主として『英語学人名辞典』 (376--77) に拠り,伝記的に紹介する. *

Noah Webster は,1758年,Connecticut 州は West Hartford で生まれた.学校時代に学業で頭角を表わし,1778年,Yale 大学へ進学する.在学中に独立戦争が勃発し,新生国家への愛国精神を育んだ.

大学卒業後,教員そして弁護士となったが,教員として務めていたときに,従来の Dilworth による英語綴字教本に物足りなさを感じ,自ら教本を執筆するに至った.A Grammatical Institute of the English Language と題された教本は,第1部が綴字,第2部が文法,第3部が読本からなるもので,この種の教材としては合衆国初のものだった.全体として愛国的な内容となっており,国内のほぼすべての学校で採用された.第1部の綴字教本は,後に The American Spelling Book として独立し,100年間で8000万部売れたというから大ベストセラーである.表紙が青かったので "Blue-Backed Speller" と俗称された.この本からの収入だけで,Webster は一生の生計を支えられたという.

Webster は,言論を通じて政治にも関与した.1793年,New York で日刊新聞 American Minerva (後の Commercial Advertiser)および半週刊誌 Herald (後の New York Spectator)を発刊し,Washington 大統領の政策を支えた.後半生は,Connecticut 州の New Haven と Massachusetts 州の Amherst で過ごした.

言語方面では,1806年に A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language を著わし,1807年に A Philosophical and Practical Grammar of the English Language を著わした.Compendious Dictionary では,すでに綴字の簡易化が実践されており,favor, honor, savior; logic, music, physic; cat-cal, etiquet, farewel, foretel; ax, disciplin, examin, libertin; benum, crum, thum (v.) / ake, checker, kalender, skreen; croop, soop, troop; fether, lether, wether; cloke, mold, wo; spunge, tun, tung などが見出しとして立てられている.

1807年からは大辞典の編纂に着手し,途中,作業のはかどらない時期はあったものの,1828年についに約7万項目からなる2巻ものの大辞典 An American Dictionary of the English Language が出版された.これは,Johnson の辞書の1818年の改訂版よりも約1万2千項目も多いものだった.Compendious Dictionary に採用されていた簡易化綴字の多くは,今回は不採用となったが,いくつかは残っており,それらは現代にまで続くアメリカ綴字となった.語源記述に関しては,Webster は当時ヨーロッパで勃興していた比較言語学にインスピレーションを受け,多くの単語に独自の語源説を与えたが,実際には比較言語学をよく理解しておらず,同辞典を無価値な記述で満たすことになった.

性格としては傲岸不遜な一面があり,人々に慕われる人物ではなかったようだが,アメリカ合衆国の独立を支えるべく「アメリカ語」の独立に一生を捧げた人生であった.

以下,Webster の主要な英語関係の著作を挙げておく.

・ A Grammatical Institute of the English Language: Part I (1783) [and its later editions: The American Spelling Book (1788) aka "Blue-Backed Speller"; The Elementary Spelling Book (1843)]: 綴字教本

・ A Grammatical Institute of the English Language: Part II (1784): 文法教本

・ A Grammatical Institute of the English Language: Part III (1785): 読本

・ Dissertations on the English Language, with Notes Historical and Critical (1789): 綴字改革の実行可能性と必要性を説く

・ A Collection of Essays and Fugitive Writings (1790): 独自の新綴字法で書かれた

・ A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (1806): 独自の新綴字法で書かれた

・ A Philosophical and Practical Grammar of the English Language (1807)

・ An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (1828)

・ An Improved Grammar of the English Language (1831)

・ Mistakes and Corrections (1837)

その他,Webster については webster の各記事,とりわけ「#468. アメリカ語を作ろうとした Webster」 ([2010-08-08-1]) と「#3086. アメリカの独立とアメリカ英語への思い」 ([2017-10-08-1]) を参照されたい.

・ 佐々木 達,木原 研三 編 『英語学人名辞典』 研究社,1995年.

・ Kendall, Joshua. The Forgotten Founding Father. New York: Berkeley, 2012.

2017-10-08 Sun

■ #3086. アメリカの独立とアメリカ英語への思い [ame][witherspoon][academy][webster][american_revolution][history]

アメリカの独立前後から,アメリカ人による「アメリカ語」の国語意識が現われてきた.自分たちの英語はイギリスの英語とは異なるものであり,独自の標準をもつべき理由がある,という多分に愛国的な意見である.昨日の記事でも引用した John Witherspoon は,アメリカ独立期に次のように述べている.

Being entirely separated from Britain, we shall find some centre or standard of our own, and not be subject to the inhabitants of that island, either in receiving new ways of speaking or rejecting the old. (qtd. in Baugh and Cable 354)

次の例として,1774年1月の Royal American Magazine に掲載された,匿名の「アメリカ人」によるアメリカ英語アカデミー設立の提案を取り挙げよう.

I beg leave to propose a plan for perfecting the English language in America, thro' every future period of its existence; viz. That a society, for this purpose should be formed, consisting of members in each university and seminary, who shall be stiled, Fellows of the American Society of Language: That the society, when established, from time to time elect new members, & thereby be made perpetual. And that the society annually publish some observations upon the language and from year to year, correct, enrich and refine it, until perfection stops their progress and ends their labour.

I conceive that such a society might easily be established, and that great advantages would thereby accrue to science, and consequently America would make swifter advances to the summit of learning. It is perhaps impossible for us to form an idea of the perfection, the beauty, the grandeur, & sublimity, to which our language may arrive in the progress of time, passing through the improving tongues of our rising posterity; whose aspiring minds, fired by our example, and ardour for glory, may far surpass all the sons of science who have shone in past ages, & may light up the world with new ideas bright as the sun. (qtd. in Baugh and Cable 354)

「#2791. John Adams のアメリカ英語にかけた並々ならぬ期待」 ([2016-12-17-1]) でみたように,後のアメリカ第2代大統領 John Adams が1780年にアカデミー設立を提案していることから,上の文章も Adams のものではないかと疑われる.

そして,愛国意識といえば Noah Webster を挙げないわけにはいかない.「#468. アメリカ語を作ろうとした Webster」 ([2010-08-08-1]) で有名な1節を引いたが,今回は別の箇所をいくつか引用しよう.

The author wishes to promote the honour and prosperity of the confederated republics of America; and cheerfully throws his mite into the common treasure of patriotic exertions. This country must in some future time, be as distinguished by the superiority of her literary improvements, as she is already by the liberality of her civil and ecclesiastical constitutions. Europe is grown old in folly, corruption and tyranny....For America in her infancy to adopt the present maxims of the old world, would be to stamp the wrinkles of decrepid age upon the bloom of youth and to plant the seeds of decay in a vigorous constitution. (Webster, Preface to A Grammatical Institute of the English Language: Part I (1783) as qtd. in Baugh and Cable 357)

As an independent nation, our honor requires us to have a system of our own, in language as well as government. Great Britain, whose children we are, should no longer be our standard; for the taste of her writers is already corrupted, and her language on the decline. But if it were not so, she is at too great a distance to be our model, and to instruct us in the principles of our own tongue. (Webster, Dissertations on the English Language, with Notes Historical and Critical (1789) as qtd. in Baugh and Cable 357)

It is not only important, but, in a degree necessary, that the people of this country, should have an American Dictionary of the English Language; for, although the body of the language is the same as in England, and it is desirable to perpetuate that sameness, yet some difference must exist. Language is the expression of ideas; and if the people of our country cannot preserve an identity of ideas, they cannot retain an identity of language. Now an identity of ideas depends materially upon a sameness of things or objects with which the people of the two countries are conversant. But in no two portions of the earth, remote from each other, can such identity be found. Even physical objects must be different. But the principal differences between the people of this country and of all others, arise from different forms of government, different laws, institutions and customs...the institutions in this country which are new and peculiar, give rise to new terms, unknown to the people of England...No person in this country will be satisfied with the English definitions of the words congress, senate and assembly, court, &c. for although these are words used in England, yet they are applied in this country to express ideas which they do not express in that country. (Webster, Preface to An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828) as qtd. in Baugh and Cable 358)

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2017-10-04 Wed

■ #3082. "spelling bee" の起源と発達 [spelling][ame][history][webster][word_play][spelling_bee]

Simon Horobin 著 Does Spelling Matter? (堀田による邦訳『スペリングの英語史』も参照)で,いろいろな形で取り上げられているが,アメリカでは伝統的にスペリング競技会 "spelling bee" が人気である.

スペリング競技会の起こりはエリザベス朝のイングランドにあるが,注目される行事へと発展したのは,独立後のアメリカにおいてであった.Webster のスペリング教本 "Blue-Backed Speller" のヒットに支えられ,アメリカの国民的イベントへと成長した.Webster の伝記を著した Kendall (106--07) が,スペリング競技会の歴史について次のように述べている.

Webster's speller also gave rise to America's first national pastime, the spelling bee. Before there was baseball or college football or even horse racing, there was the spectator sport that Webster put on the map. Though "the spelling match" first became a popular community event shortly after Webster's textbook became a runaway best seller, its origins date back to the classroom in Elizabethan England. In his speller, The English Schoole-Maister, published in 1596, the British pedagogue Edmund Coote described a method of "how the teacher shall direct his schollers to oppose one another" in spelling competitions. A century and a half later, in his essay, "Idea of the English School," Benjamin Franklin wrote of putting "two of those [scholars] nearest equal in their spelling" and "let[ting] these strive for victory each propounding ten words every day to the other to be spelt." Webster's speller transformed these "wars of words" from classroom skirmishes into community events. By 1800, evening "spelldowns" in New England were common. As one early twentieth-century historian has observed:

The spelling-bee was not a mere drill to impress certain facts upon the plastic memory of youth. It was also one of the recreations of adult life, if recreation be the right word for what was taken so seriously by every one. [We had t]he spectacle of a school trustee standing with a blue-backed Webster open in his hand while gray-haired men and women, one row being captained by the schoolmaster and the other team by the minister, spelled each other down.

綴字と発音の乖離がみられる英単語のスペリング競技会で勝つためには,並外れた暗記力と語源的な知識が試される.ある意味で,英語らしいイベントといえるだろう.

・ Kendall, Joshua. The Forgotten Founding Father. New York: Berkeley, 2012.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ サイモン・ホロビン(著),堀田 隆一(訳) 『スペリングの英語史』 早川書房,2017年.

2017-10-01 Sun

■ #3079. 拙訳『スペリングの英語史』が出版されました [notice][spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][history][hel_education][toc][link]

9月20日付で,拙訳『スペリングの英語史』が早川書房より出版されました.原著は本ブログで何度も参照・引用している Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013. です.本ブログを読まれている方,そして英語スペリングの諸問題に関心をもっているすべての方に,おもしろく読んでもらえる内容です.

|

| サイモン・ホロビン(著),堀田隆一(訳) 『スペリングの英語史』 早川書房,2017年.302頁.ISBN: 978-4152097040.定価2700円(税別). |

「本書をただのスペリングの本だと思ったら大間違いである.ここには,英語史,英文学をはじめ,英語の教養がぎっしりと詰まっている」との推薦文を,東大の斎藤兆史先生より寄せていただきました.また,本書の帯に「オックスフォード大学英語学教授による,スペリングの謎に切り込む名解説」という売り文句がありますが,訳者も英語のスペリングに関する読ませる本としては最高のものであると確信しています(もう1冊の読ませるスペリング本として,Crystal, David. Spell It Out: The Singular Story of English Spelling. London: Profile Books, 2012. も薦めます).

本書には,このスペリングやあのスペリングの背景にこんな歴史的な事件が関与していたのか,と驚くエピソードが満載です.例えば・・・

・ 合衆国副大統領の政治生命の懸かった,potato のスペリングをめぐる醜聞

・ 『指輪物語』のトールキンは,独自のアルファベット体系を考案し,それで日記をつけていた

・ 最古の英文はローマ字ではなくルーン文字で書かれていた

・ 中英語期には such の異なるスペリングが500種類もあった

・ ルネサンス期のラテン語かぶれの知識人が,doubt の <b> のような妙なスペリングの癖を生み出した

・ シェイクスピア『リア王』で語られる,英語における <z> の文字の冷遇

・ Smith さんか,Smythe さんか,はたまた Psmith さんか --- 名前のスペリングへのこだわり

・ みずからの遺産を理想的なアルファベット考案の賞金にあてた劇作家バーナード・ショー

・ ウェブスターがアメリカ式スペリングの改革に成功したのは,独立の愛国心とベストセラー『スペリング教本』の商業的成功ゆえ

・ 電子メールに溢れる省略スペリングは,英語の堕落の現われか,言語的創造力のたまものか

本書の目次は,以下の通りとなっています.

日本版への序文

図一覧

発音記号

1 序章

2 種々の書記体系

3 起源

4 侵略と改正

5 ルネサンスと改革

6 スペリングの固定化

7 アメリカ式スペリング

8 スペリングの現在と未来

読書案内

参考文献

訳者あとがき

語句索引

原著の著者ついて,簡単に紹介しておきます.サイモン・ホロビン氏はオックスフォード大学モードリン・カレッジ・フェローの英語学教授です.英語史・中世英語英文学を専門としており,以下のような主要著書を世に送り出してきました.まさに気鋭の英語史研究者です.

・ Horobin, Simon and Jeremy Smith. An Introduction to Middle English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2002.

・ Horobin, Simon. The Language of the Chaucer Tradition. Cambridge: Brewer, 2003.

・ Horobin, Simon. Chaucer's Language. 1st ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 2nd ed. 2012.

・ Horobin, Simon. Studying the History of Early English. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

・ Horobin, Simon. How English Became English: A Short History of a Global Language. Oxford: OUP, 2016.

また,最近はあまり更新されていないようですが,著者は2012年から Spelling Trouble という英語のスペリングの話題を提供するブログで,いくつかの記事を書いています.

ちなみに個人的なことをいえば,訳者はグラスゴー大学に留学し2005年に博士号を取得しましたが,当時,著者はグラスゴー大学で教鞭を執っており,訳者の学位審査官の1人でもありました.あのときもお世話になり,このたびもお世話になり,という経緯です.さらに,2年前の2014年12月には,本書にインスピレーションを受けて開催したシンポジウムに著者を招き,英語のスペリングについて一緒に議論する機会をもつことができました(cf. 「#2053. 日本中世英語英文学会第30回大会のシンポジウム "Does Spelling Matter in Pre-Standardised Middle English?" を終えて」 ([2014-12-10-1])).

間違いなく英語のスペリングがよく分かるようになります.『スペリングの英語史』を是非ご一読ください.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ サイモン・ホロビン(著),堀田 隆一(訳) 『スペリングの英語史』 早川書房,2017年.

2017-09-22 Fri

■ #3070. 暗号として用いられた普通語 [cryptology][history]

「#2699. 暗号学と言語学」 ([2016-09-16-1]),「#2729. あらゆる言語は暗号として用いられる」 ([2016-10-16-1]) でみたように,通常の言語であっても使用者の少ない言語であれば,そのまま暗号として用いられうる.第2次世界大戦のナヴァホ族のコード・トーカーがよく知られているが,長田(著)『暗号大全』によると,ほかにも歴史上の「普通語」使用の事例はある (33--35) .

例えば,中世ヨーロッパでは一般的だったように,ラテン語は聖職者を初めとする知識人しか使いこなすことができなかった.それゆえ,聖職者どうしが意識的に庶民に知られたくないコミュニケーションを取ろうと思えば,ラテン語でやりとりすればよいのだった.

紀元前まで遡ると,シーザーがガリア遠征(紀元前54年)の軍事暗号として,ギリシア語を用いたことが知られている.ガリアの種族はギリシア語を解さなかったので,普通語であるギリシア語を用いるだけで,そのまま事実上の暗号となったのである.

19世紀末に話しは飛ぶが,南アフリカで繰り広げられたボーア戦争において,イギリス軍の将校は,ボーア人の知らないラテン語で命令や報告の伝達を行なっていた.

1960年,ベルギー軍がコンゴ共和国の首都レオポルドビルに侵入したとき,これに対して派遣された国連軍のなかにアイルランド兵がいた.彼らは無線電話で母語のゲール語を用いて伝達情報を秘匿した.当時の国連軍司令官は「これこそ,最良の暗号だ」と激賛したという.

最後に,我が国で,昭和46年の新聞に「朝鮮語,非行少女の間で流行」という記事があったもという.

長田 (35) は,この種の「暗号」は上記のように有効性を示した局面もあったが,「第三者のコトバに関する無知に依存しているわけだから」本質的には消極的な暗号であるとしている.考えてみれば,自分ともう1人以外には日本語を解する人がいないと思われる国際的な会話の場面で,あえて2人の間で日本語を符丁として用いるという状況はあるが,実は周囲の誰かが日本語を解するという可能性はゼロではない.確実に情報を秘匿したいときに使えるワザではない,というのは確かだろう.

・ 長田 順行 『暗号大全 原理とその世界』 講談社,2017年.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow