2020-02-29 Sat

■ #3960. 子音群前位置短化の事例 [sound_change][vowel][consonant][phonology][phonetics][shortening][shocc][homorganic_lengthening]

昨日の記事「#3959. Ritt による同器性長化の事例」 ([2020-02-28-1]) に引き続き,後期古英語から初期中英語に生じたもう1つの母音の量の変化として,子音群前位置短化 (Shortening before Consonant Clusters (= SHOCC) or Pre-Cluster Shortening) の事例を,Ritt (98) より初期中英語での形態で紹介しよう.現代英語の形態と比較できるもののみを挙げる.

| kepte | 'kept' |

| brohte | 'brought' |

| sohte | 'sought' |

| þuhte | 'thought' |

| demde | 'deemed' |

| mette | 'met' |

| lædde | 'led' |

| sprædde | 'spread (past)' |

| bledde | 'bled' |

| fedde | 'fed' |

| hydde | 'hid' |

| softe | 'soft' |

| fifta | 'fifth' |

| leoht | 'light' |

| hihþu | 'height' |

| dust | 'dust' |

| blæst | 'blast' |

| breost | 'breast' |

| fyst | 'fist' |

| mist | 'mist' |

| druhþ | 'drought' |

| clænsian | 'cleanse' |

| halja | 'holy (man), saint' |

| mædd | 'mad' |

| fætt | 'fat' |

| wræþþo | 'wrath' |

| cyþþo | 'kin' |

| feoll | 'fell' |

| fiftiȝ | 'fifty' |

| twentiȝ | 'twenty' |

| bledsian | 'bless' |

| wisdom | 'wisdom' |

| wifman | 'woman' |

| hlæfdiȝe | 'lady' |

| ȝosling | 'gosling' |

| ceapman | 'chapman' |

| nehhebur | 'neighbour' |

| siknesse | 'sickness' |

SHOCC の名称通り,2つ以上の子音群の直前にあった長母音が短化する変化である.定式化すれば次のようになる.

V → [-long]/__CCX

where CC is not a homorganic cluster

上の一覧から分かる通り,SHOCC は kept, met, led, bled, fed など語幹が歯茎破裂音で終わる弱変化動詞の過去・過去分詞形に典型的にみられる.また,fifth の例も挙げられているが,これらについては「#1080. なぜ five の序数詞は fifth なのか?」 ([2012-04-11-1]) や「#3622. latter の形態を説明する古英語・中英語の "Pre-Cluster Shortening"」 ([2019-03-28-1]) を参照されたい.一覧にはないが,この観点から against の短母音 /ɛ/ での発音についても考察することができる(cf. 「#543. says や said はなぜ短母音で発音されるか (2)」 ([2010-10-22-1])).

SHOCC は,昨日扱った同器性長化 (homorganic_lengthening) とおよそ同時代に生じており,かつ補完的な関係にある音変化であることに注意しておきたい.以下も参照.

・ 「#2048. 同器音長化,開音節長化,閉音節短化」 ([2014-12-05-1])

・ 「#2052. 英語史における母音の主要な質的・量的変化」 ([2014-12-09-1])

・ 「#2063. 長母音に対する制限強化の歴史」 ([2014-12-20-1])

・ Ritt, Nikolaus. Quantity Adjustment: Vowel Lengthening and Shortening in Early Middle English. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2020-02-28 Fri

■ #3959. Ritt による同器性長化の事例 [homorganic_lengthening][sound_change][vowel][phonology][phonetics][monophthong]

古英語から中英語にかけて生じたとされる,同器性長化 (homorganic_lengthening) と呼ばれる音変化がある.これについては「#2048. 同器音長化,開音節長化,閉音節短化」 ([2014-12-05-1]) で簡単に解説した通りだが,英語史的には2重母音をもつ child と短母音をもつ children の違いを説明する際に引き合いに出される重要な音変化の1つである(cf. 「#145. child と children の母音の長さ」 ([2009-09-19-1]),「#146. child の複数形が children なわけ」 ([2009-09-20-1])).

そうはいっても,child/children の母音の長短を間接的に説明してくれる以外に,他にどのような現代英語の語の音形について説明してくれるのかといえば,実はたいして多くの好例は挙がらない.「#2862. wilderness」 ([2017-02-26-1]) の記事で wild/wilderness の差異に触れたが,このように上手く説明される例は珍しいほうである.Ritt (82) が挙げている同器性長化を経た語の例をいくつか挙げてみよう.

| Pre-HOL | Post-HOL | |

| ld: | cild | cīld |

| feld | fēld | |

| gold | gōld | |

| geldan | gēldan | |

| rd: | word | wōrd |

| sword | swōrd | |

| mb: | climban | clīmban |

| cemban | cēmban | |

| dumb | dūmb | |

| mb: | behindan | behīndan |

| ende | ēnde | |

| hund | hūnd | |

| ng: | singan | sīngan |

| lang | lāng | |

| tunge | tūnge | |

| rl: | eorl | ēorl |

| rn: | stiorne | stīorne |

| georn | gēorn | |

| korn | kōrn | |

| murnan | mūrnan | |

| rð: | eorðe | ēorðe |

| weorðe | wēorðe | |

| wyrðe | wȳrðe | |

| furðor | fūrðor | |

| rs: | earsas | ēarsas |

確かに同器性長化は,なぜ現代英語で climb や behind が2重母音をもつのかを説明してくれる.しかし,この一覧のそれ以外の語についてはあまり啓蒙的ではない.同器性長化により長母音化したものが後の歴史で再び短母音化するなどして現代に至っているため,現代の目線からはその効果があまり感じられないからだ.とはいえ,英語史的には注目すべき母音変化ではある.

・ Ritt, Nikolaus. Quantity Adjustment: Vowel Lengthening and Shortening in Early Middle English. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2020-02-27 Thu

■ #3958. Ritt による中英語開音節長化の公式 [meosl][sound_change][vowel][phonology][phonetics][sonority][neogrammarian][homorganic_lengthening]

昨日の記事「#3957. Ritt による中英語開音節長化の事例と反例」 ([2020-02-26-1]) でみたように,中英語開音節長化 (Middle English Open Syllable Lengthening; meosl) には意外と例外が多い.音環境がほぼ同じに見えても,単語によって問題の母音の長化が起こっていたり起こっていなかったりするのだ.

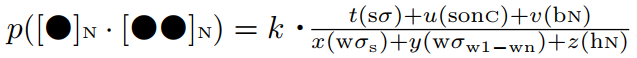

Ritt (75) は MEOSL について,母音の長化か起こるか否かは,音環境の諸条件を考慮した上での確率の問題ととらえている.そして,次のような公式を与えている (75) .

The probability of vowel lenghthening was proportional to

a. the (degree of) stress on it

b. its backness

c. coda sonority

and inversely proportional to

a. its height

b. syllable weight

c. the overall weight of the weak syllables in the foot

In this formula t, u, v, x, y and z are constants. Their values could be provided by the theoretical framework and/or by induction (= trying the formula out on actual data).

これだけでは何を言っているのか分からないだろう.要点を解説すれば以下の通りである.MEOSL が生じる確率は,6つのパラメータの値(および値が未知の定数)の関数として算出される.6つのパラーメタとその効果は以下の通り.

(1) 問題の音節に強勢があれば,その音節の母音の長化が起こりやすい

(2) 問題の母音が後舌母音であれば,長化が起こりやすい

(3) coda (問題の母音に後続する子音)の聞こえ度 (sonority) が高ければ,長化が起こりやすい

(4) 問題の母音の調音点が高いと,長化が起こりにくい

(5) 問題の音節が重いと,長化が起こりにくい

(6) 問題の韻脚中の弱音節が重いと,長化が起こりにくい

算出されるのはあくまで確率であるから,ほぼ同じ音環境にある語であっても,母音の長化が起こるか否かの結果は異なり得るということだ.Ritt のアプローチは,青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) 的な「音韻変化に例外なし」の原則 (Ausnahmslose Lautgesetze) とは一線を画すアプローチである.

なお,この関数は,実は同時期に生じたもう1つの母音長化である同器性長化 (homorganic_lengthening) にもそのまま当てはまることが分かっており,汎用性が高い.同器性長化については明日の記事で.

・ Ritt, Nikolaus. Quantity Adjustment: Vowel Lengthening and Shortening in Early Middle English. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2020-02-26 Wed

■ #3957. Ritt による中英語開音節長化の事例と反例 [meosl][sound_change][vowel][phonology][phonetics][final_e]

中英語開音節長化 (Middle English Open Syllable Lengthening; meosl) は,12--13世紀にかけて生じたとされる重要な母音変化の1つである.典型的に2音節語において,強勢をもつ短母音で終わる開音節のその短母音が長母音化する変化である.「#2048. 同器音長化,開音節長化,閉音節短化」 ([2014-12-05-1]) でみたように,nama → nāma, beran → bēran, ofer → ōfer などの例が典型である.

この音変化が進行していた初期中英語期での語形と現代英語での語形を並べることで,具体的な事例を確認しておこう.以下,Ritt (12) より.

| EME | ModE |

| labor | labour |

| basin | basin |

| barin | bare |

| whal | whale |

| waven | wave |

| waden | wade |

| tale | tale |

| starin | stare |

| stapel | staple |

| stede | steed |

| bleren | blear |

| repen | reap |

| lesen | lease |

| efen | even |

| drepen | drepe |

| derien | dere |

| dene | dean |

| -stoc | stoke (X-) |

| sole | sole |

| mote | mote (of dust) |

| mote | moat |

| hopien | hope |

| cloke | cloak |

| smoke | smoke |

| broke | broke |

| ofer | over |

しかし,実のところ MEOSL には例外が多いことも知られている.Ritt (14) より,先の条件を満たすにもかかわらず長母音化が起こっていない例を掲げよう.

| EME | ModE |

| adlen | addle |

| aler | alder |

| alum | alum |

| anet | anet |

| anis | anise |

| aspen | aspen |

| azür | azure |

| baron | baron |

| barrat | barrat |

| baril | barrel |

| bet(e)r(e) | better |

| besant | bezant |

| brevet | brevet |

| celer | cellar |

| devor | endeavour |

| desert | desert |

| ether | edder |

| edisch | eddish |

| feþer | feather |

| felon | felon |

| bodig | body |

| bonnet | bonnet |

| boþem | bottom |

| broþel | brothel |

| closet | closet |

| koker | cocker |

| cokel | cockle |

| cofin | coffin |

| colar | collar |

| colop | collop |

では,先の条件をさらに精緻化すれば MEOSL の適用の有無を予測できるのだろうか.あるいは,畢竟単語ごとの問題であり,ランダムといわざるを得ないのだろうか.この問題に本格的に取り組んだのが Ritt の研究書である.

MEOSL は,現代英語の正書法における "magic <e>" の起源にも関わるし,「大母音推移」 (gsv) への入力も提供した英語史上非常に重要な音変化ではあるが,意外と問題点は多い.この音変化に関しては「#1402. 英語が千年間,母音を強化し子音を弱化してきた理由」 ([2013-02-27-1]),「#2052. 英語史における母音の主要な質的・量的変化」 ([2014-12-09-1]),「#2497. 古英語から中英語にかけての母音変化」 ([2016-02-27-1]) などの記事を参照.

・ Ritt, Nikolaus. Quantity Adjustment: Vowel Lengthening and Shortening in Early Middle English. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2020-02-16 Sun

■ #3947. 子音群における l の脱落 [l][phonetics][sound_change][etymological_respelling][anglo-norman][french]

「#2027. イングランドで拡がる miuk の発音」 ([2014-11-14-1]) でみたように,目下イングランドで母音が後続しない l の母音化という音変化が進行中である.歴史的にみれば,l がある音環境において軟口蓋化を経た後に脱落していくという変化は繰り返し生じてきており,昨今の変化も l の弱化という一般的な傾向のもう1つの例とみなすことができる.

l の脱落に関する早い例は,初期中英語期より確認される.古英語の hwylc (= "which"), ælc (= "each"), wencel (= "wench"), mycel (= "much") のように破擦音 c が隣り合う環境で l が脱落し,中英語には hwich, ech, wenche, muche として現われている.ほかに古英語 ealswa (= "as") → 中英語 als(o)/as,sceolde (= "should") → shud,wolde (= "would") → wud なども観察され,中英語期中に主に高頻度語において l の脱落が生じていたことがわかる.近代英語期に近づくと,folk や halfpenny など,軟口蓋音や唇音の隣りの位置においても l の脱落が起こった.

このように l の弱化は英語史における一般的な傾向と解釈してよいが,似たような変化が隣のフランス語で早くから生じていた事実には注意しておきたい.Minkova (131) が鋭く指摘している通り,英語史上の l の脱落傾向は,一応は独立した現象とみてよいが,フランス語の同変化から推進力を得ていたという可能性がある.

An important, though often ignored contributing factor in the history of /l/-loss in English is the fact that Old French and Anglo-Norman had undergone an independent vocalisation of /l/. Vocalisation of [ɫC] clusters, similar to [rC] clusters, started in OFr in the ninth century, and although the change in AN seems to have been somewhat delayed ... , the absence of /lC/ in bilingual speakers would undermine the stability of the cluster in ME. Thus we find Pamer (personal name, 1207) < AN palmer, paumer 'palmer, pilgrim', OE palm 'palm' < Lat. palma ? OFr paume, ME sauder, sawder < OFr soud(i)er, saudier 'soldier', sauf 'safe' < Lat. salvus. The retention of the /l/ in some modern forms, as in fault, vault is an Early ModE reversal to the original Latin form, and in some cases we find interesting alternations such as Wat, Watson, Walter.

引用の後半にあるように,フランス語で l が脱落した効果は英語が借用した多くのフランス借用語にも反映されており,それが初期近代英語期の綴字に l を復活させる語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の前提を用意した,という英語史上の流れにも注意したい.一連の流れは,l の子音としての不安定さを実証しているように思われる.

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

2020-02-15 Sat

■ #3946. 古英語の接頭辞 ge- の化石的生き残り [prefix][sound_change][etymology][german]

古英語の語彙には,ge- という接頭辞がやたらと付加している.様々な品詞にまたがって ge- で始まる単語があまりに多いので,典型的な古英語辞書ではそのような語は g の項目には配置されず,ge- に続く語幹部分の頭文字の文字によって配置されるほどだ.現代ドイツ語の ge- /ɡe/ に相当するゲルマン系の古い接頭辞だが,古英語では /ɡe/ ではなく軟音化した /je/ として発音された.現代の初級古英語校訂本では,軟音の <g> を明示するために点を打って ġe- と表記されることも多い.

この接頭辞は,古英語期までにすでに軟音化していたくらいだから,その後も弱化の一途を辿る運命であり,中英語には /je/ から /i/ 程度に弱化し,その後期ともなると広範囲で消失した.近代英語期には,接頭辞がそれとわかる形で残っている例は事実上皆無だったといってよいだろう.

しかし,かつての ge- の痕跡が化石的に生き残っている単語も,実はちらほらと残っている.たとえば enough の語頭の <e> がそれである.古英語の genoh が,音形上ずいぶん薄められながらも,現代まで生き延びてきた例である.

ほかに afford, alike, aware などの語頭の a- も,古英語の接頭辞 ge- に遡る.各々の古英語形は geforþian, gelīc, gewær である.

また,古語といってよいが yclept (?と呼ばれる,?という名前の)という語の語頭の <y> もある.これは,古英語で「呼ぶ」を意味する clipian/cleopian という動詞の過去分詞形に由来する(ex. a giant yclept Barbarossa (赤ひげと呼ばれる巨人)).同じ過去分詞形の例としては,やはり古語だが yclad (= clothed) もある.これらは古英語の動詞の過去分詞に一般的に付加された接頭辞 ge- が生き残った,限りなく稀な例といってよい.

この古英語接頭辞については,「#150. アメリカ英語へのドイツ語の貢献」 ([2009-09-24-1]),「#1253. 古ノルド語の影響があり得る言語項目」 ([2012-10-01-1]),「#1710. of yore」 ([2014-01-01-1]),「#3432. イギリス議会の起源ともいうべきアングロ・サクソンの witenagemot」 ([2018-09-19-1]) の各記事でも触れているので一読を.

2020-02-11 Tue

■ #3942. 印欧祖語からゲルマン祖語への主要な母音変化 [vowel][indo-european][germanic][sound_change][centralisation]

標題は,印欧祖語の形態から英単語の語源を導こうとする上で重要な知識である.上級者は,語源辞書や OED の語源欄を読む上で,これを知っているだけでも有用.Minkova (68--69) より.

| a | ──┐ | PIE *al- 'grow', Lat. aliment, Gmc *alda 'old' | |

| ├── | a | ||

| o | ──┘ | PIE *ghos-ti- 'guest', Lat. hostis, Goth. gasts | |

| ā | ──┐ | PIE *māter, Lat. māter, OE mōder 'mother' | |

| ├── | ō | ||

| ō | ──┘ | PIE *plōrare 'weep', OE flōd 'flood' | |

| i | ──┐ | PIE *tit/kit 'tickle', Lat. titillate, ME kittle | |

| ├── | i | ||

| e | ──┘ | Lat. ventus, OE wind 'wind', Lat. sedeo, Gmc *sitjan 'sit' |

たとえば,印欧祖語で *māter "mother" は ā の長母音をもっていたが,これがゲルマン祖語までに ō に化けていることに注意.実際,古英語でも mōdor として現われている.この長母音が後に o へと短化し,さらに一段上がって u となり,最終的に中舌化するに至って現代の /ʌ/ にたどりついた.英語の母音は,5,6千年の昔から,概ね規則正しく変化し続けて現行のものになっているのである.

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2020-02-07 Fri

■ #3938. 語頭における母音の前の h ばかりが問題視され,子音の前の h は問題にもされなかった [h][sound_change][consonant][aphaeresis][phonotactics]

昨日の記事「#3937. hospital や humble の h も200年前には発音されていなかった?」 ([2020-02-06-1]) で,語頭が <h> で綴られていながら /h/ で発音されない小さな語群があること,またその語群のメンバーも通時的に変化してきたことをみた.そのような例外的な振る舞いを示す語群が,なぜ,どのようにして選ばれてきたのかは不明であり,今のところ恣意的(社会言語学的恣意性とでもいおうか)というよりほかないように思われる.

選択の恣意性ということでいえば,もう1つ関連する現象がある.上記の例外の対象や h-dropping の非難が差し向けられる対象は,主にラテン語,フランス語,ギリシア語からの借用語の語頭における母音の前の h であることだ.換言すれば,h の消失や復活が社会的威信の問題となるかどうかは語源や音環境に依存しているということだ(語源との関連については「#3936. h-dropping 批判とギリシア借用語」 ([2020-02-05-1]) を参照).語源や音環境が異なるケースでは,そもそも h は問題にすらなっていないという事実がある.

具体的にいえば,本来語の語頭において子音の前に現われる h である.古英語では hring (= "ring"), hnappian (= "to nap"), hlot (= "lot"; cf. 「#2333. a lot of」 ([2015-09-16-1])),hwīt (= "white") などの語頭の子音連鎖が音素配列上あり得たが,初期中英語期の11--12世紀に h が弱化・脱落し始めた (Minkova 108--09) .この音変化については「#3386. 英語史上の主要な子音変化」 ([2018-08-04-1]) で少し触れた程度だが,英語史上の母音の前位置での h の消失(あるいは不安定さ)とも無関係ではない.子音連鎖における h の消失は,現代の発音にも綴字にも痕跡を残さないくらいに完遂したが,hw- (後に <wh-> と綴られることになる)のみは例外といえるだろう.これについては「#1795. 方言に生き残る wh の発音」 ([2014-03-27-1]),「#3630. なぜ who はこの綴字でこの発音なのか?」 ([2019-04-05-1]),「#1783. whole の <w>」 ([2014-03-15-1]) を参照されたい.

いずれにせよ,古英語に存在した語頭の「h + 子音」は,近代英語までに完全に消失し,音素配列的にも社会言語学的にも問題とすらなり得なかった.近代英語までに問題となり得るべく残ったのは,それ自身が長い歴史をもつ「h + 母音」における h だった.そこに音素上の問題,そしていかにも近代英語的な懸案事項である語種の問題,および社会言語学的威信の問題が絡まって,現在にまで続く「h を巡る難問」が立ち現われてきたのである.

h を巡る問題は,このように英語史上の原因があるといえばあるのだが,究極的には恣意的と言わざるを得ない.音韻史上の必然的なインプットが,社会言語学的に恣意的なアウトプットに利用された,という風に見えるのである.

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

2020-01-16 Thu

■ #3916. 強弱音節の区別と母音変化の関係 [gvs][stress][vowel][sound_change][drift][metrical_phonology][meosl]

昨日の記事「#3915. 大母音推移と周辺の母音変化の循環的な性質」 ([2020-01-15-1]) の最後に示唆したように,現代の歴史英語音韻論では,強勢の有無やリズムなどの韻律上の性質と母音変化の頻繁さの間には密接な関係があると考えられている.

英語や他のゲルマン諸語では,周知のように,音節の強弱の区別,ひいては母音の強弱の区別が機能的に重視される.これにより,韻律上のリズムにも一定の型が出現することになり,その型に調和する形で母音もその質や量を変化・変異させてきたという議論だ.この見解については「#3387. なぜ英語音韻史には母音変化が多いのか?」 ([2018-08-05-1]),「#3466. 古英語は母音の音量を,中英語以降は母音の音質を重視した」 ([2018-10-23-1]),「#1402. 英語が千年間,母音を強化し子音を弱化してきた理由」 ([2013-02-27-1]) などで紹介してきたが,今回は英語史における主要な長母音変化に関する研究書を著わした Stenbrenden の結論部より,似た趣旨の議論を引用したい (318) .

. . . stressed syllables and vowels behave differently from unstressed syllables and vowels. Since stress in Gmc involves intensity (perceptual loudness and more muscular and respiratory force) in addition to pitch prominence, various articulatory features are a consequence of stress: stressed vowels are longer and usually more peripheral (in terms of the vowel space), fortis plosives have more aspiration, etc. Lack of stress, on the other hand, involves little muscular effort and perceptual 'softness', and often low/level pitch; unstress therefore has articulatory consequences like shorter and more centralised vowels (or at least loss of vowel contrasts . . .), vowel reduction, vowel and consonant elision, and little to no aspiration of fortis plosives, etc. Thus, what is known as the 'syncopation period' in early Gmc may be interpreted as only the beginning of a long process involving the gradual reduction and loss of unstressed vowels and syllables, the last major instance of which is witnessed (in English) in the loss of final schwa. Related to this reduction process are the lOE and ME processes that lengthen vowels in open syllables and shorten vowels in words of two or more syllables. Clearly, metrical considerations play a crucial role here . . . .

この引用の最後で,中英語開音節長化 (Middle English Open Syllable Lengthening; meosl) などに触れており,いわゆる大母音推移 (gvs) にこそ触れていないものの,著者がそれらも含めてゲルマン語の漂流 (drift) を考えていることは間違いない.主要な母音変化の多くが何らかの形で関連しており,その意味ではすべてひっくるめて "chain shift" なのだという考え方である.

・ Stenbrenden, Gjertrud Flermoen. Long-Vowel Shifts in English, c. 1150--1700: Evidence from Spelling. Cambridge: CUP, 2016.

2020-01-15 Wed

■ #3915. 大母音推移と周辺の母音変化の循環的な性質 [gvs][vowel][sound_change][drift][isochrony][prosody]

昨日の記事「#3914. Stenbrenden 曰く「大母音推移は長期の漂流の一部にすぎない」」 ([2020-01-14-1]) で引用した Stenbrenden は,「大母音推移」 (gvs) を長期的な視野から観察し,より大きな母音変化の漂流 (drift) の一部であると再評価した.では,その漂流というのは,いかなる存在なのか.Stenbrenden (316) は,調査対象とした長母音と,それが歴史的にたどってきた変化タイプを以下のように一覧にし,いくつかの変化タイプが繰り返し現われる事実に注目した.

ME and eModE long-vowel shifts

OE vowel, PDE reflex Type of change Date of beginning of change ȳ > ī > /aɪ/ unrounding 950 diphthongisation 1250 ēo > ø̄ > ē > /iː/ monophthongisation 11th century unrounding 12th--15th centuries raising 1250 ā > ō̜ > ō > [ou] > /əʊ/ rounding 11th century raising 16th century diphthongisation 16th century ǣ > e̜ > ē > /iː/ or /eɪ/ raising /ɛː/ 11th c.; /eː/ 15th c.; /iː/ 16th c. (diphthongisation) (16th--17th centuries) ē > /iː/ raising 1225 ō > /uː/ or /ʊ/ ? /ʌ/ raising 1225 shortening; unrounding 14th--15th centuries; NF: ō > [üː] (often fronted in PDE) 15th--16th centuries NF: fronting and raising (late) 13th century ī > /aɪ/ diphthongisation 1250 ū > /aʊ/ diphthongisation 1250

繰り返し現われる変化タイプとは raising, fronting, diphthongisation, monophthongisation などのことを指すが,これらが互いに無関係に生じてきたとは考えにくい.むしろ,ここには "cyclical nature" (循環的な性質)を見出すことができそうだ.さらにいえば,英語のみならず多くのゲルマン諸語にも類似した循環的な母音変化の漂流がみられることから,ゲルマン諸語に通底する性質すら突き止めることができるかもしれない.

ヒントとなるのは,Ritt などの主張する "rhythmic isochrony" の原理,すなわち強い音節と弱い音節が明確に区別され,それらが交互に現われる韻脚の各々が,およそ同じ長さをもって発音されるという韻律上の特徴である.rhythmic isochrony と母音変化の関係については「#1402. 英語が千年間,母音を強化し子音を弱化してきた理由」 ([2013-02-27-1]) を参照.

・ Stenbrenden, Gjertrud Flermoen. Long-Vowel Shifts in English, c. 1150--1700: Evidence from Spelling. Cambridge: CUP, 2016.

2020-01-14 Tue

■ #3914. Stenbrenden 曰く「大母音推移は長期の漂流の一部にすぎない」 [gvs][vowel][sound_change][drift]

大母音推移 (gvs) に関する最新の研究書に Stenbrenden がある.この本については「#3552. 大母音推移の5つの問題」 ([2019-01-17-1]),「#3659. 大母音推移の5つの問題 (2)」 ([2019-05-04-1]) でも簡単に取り上げたが,全体として示唆に富む啓発的な内容の研究書である.

Stenbrenden は,近年の少なからぬ論者と同様に「大母音推移」を有意味な単位とみていない.中英語期から初期近代英語期にかけて展開した体系的な母音変化という含みをもった「大母音推移」は,実のところ,その前後を含めたさらに長い期間に渡る相互に関連した母音変化群の一部をなしているにすぎず,特定の一部分だけを取り上げて「大母音推移」などと名付けるのはミスリーディングである,という立場だ.

具体的にいえば,Stenbrenden (312) は以下のような種々の母音変化を調査し,各々の変化の時期が部分的に重複しながらも,全体としては11世紀から18世紀半ばまでにわたっていたと結論づけている.13--15世紀には多種類の母音変化が集中しているので密度は濃いといえるが,それもあくまでさらに大きな漂流 (drift) の一部だということだ.

| 1000 | 1100 | 1200 | 1300 | 1400 | 1500 | 1600 | 1700 | |

| OE ȳ > [iː] | **** | **** | **** | *** | ||||

| OE ēo > [eː] | ** | **** | **** | **** | *** | |||

| OE ā > [ou] | ** | **** | **** | **** | **** | **** | **** | ** |

| OE ǣ > [iː] | ** | **** | **** | **** | **** | **** | *** | |

| OE ō > [üː] N | *** | **** | *** | |||||

| OE ō > [uː] S | *** | **** | *** | |||||

| OE/ME ē > [iː] | *** | **** | *** | |||||

| OE ū > [au] | *** | **** | **** | **** | **** | ** | ||

| OE ī > [ai] | *** | **** | **** | **** | **** | ** | ||

| lME ā > [ei] | *** | **** | **** | **** | **** | ** |

まとめとして,Stenbrenden (312) から2つほど引用する.

. . . this comprehensive ME long-vowel shift started in the eleventh century at the latest, and did not come to a halt (if indeed it did) until perhaps the mid-eighteenth century.

The findings summarised in 9.1 [= the table above] indicate clearly that the traditional 'GVS' is only one part of some long-term drift in English (and other Gmc languages), and that the conventional definition of the shift is untenable.

・ Stenbrenden, Gjertrud Flermoen. Long-Vowel Shifts in English, c. 1150--1700: Evidence from Spelling. Cambridge: CUP, 2016.

2019-11-28 Thu

■ #3867. Optimality Theory --- 話し手と聞き手のニーズを考慮に入れた音韻理論 [ot][phonology][phonetics][sound_change]

一般に言語変化の主体は話し手と考えられることが多いが,聞き手の役割も実は大きいことが主張されるようになってきた.本ブログでもこの話題についていくつかの記事を書いてきた.

・ 「#1932. 言語変化と monitoring (1)」 ([2014-08-11-1])

・ 「#1933. 言語変化と monitoring (2)」 ([2014-08-12-1])

・ 「#1934. audience design」 ([2014-08-13-1])

・ 「#1935. accommodation theory」 ([2014-08-14-1]))

・ 「#1936. 聞き手主体で生じる言語変化」 ([2014-08-15-1])

・ 「#2150. 音変化における聞き手の役割」 ([2015-03-17-1])

・ 「#2586. 音変化における話し手と聞き手の役割および関係」 ([2016-05-26-1])

・ 「#3378. 音声的偏りを生み出す4要因」 ([2018-07-27-1])

最後の2つの記事のように,とりわけ音変化においては話し手と聞き手の双方の役割が重要視されるようになってきている.話し手は少しでも楽に調音したいという欲求をもっているが,あまりに簡略化した発音では聞き手に理解されない恐れがある.聞き手は話し手に対して間接的に,あまり簡略化してくれるな,むしろ正確に丁寧に調音してくれ,というプレッシャーをかけているのである.双方のニーズは相反しており,それがある程度釣り合っているところで言語が成り立っているといえる.音変化も,この釣り合いが大きく乱れない程度に起こるものと考えられる.

「#3848. ランキングの理論 "Optimality Theory"」 ([2019-11-09-1]) で紹介した最適性理論 (Optimality Theory) は,上記の2つのニーズのバランスを考慮している.OT の基本的な考え方を解説した Carr and Montreuil (258--59) より,関連する解説を引こう.

The basic architecture of the model is straightforward: a set of constraints CON represents the priorities obeyed by the grammar of a language. These constraints are violable, universal and ranked in a hierarchy. A generating function GEN provides the output candidates for a given input and an evaluation function EVAL determines the relative desirability of each output; most critically it determines which of these outputs is the optimal candidate, the 'winner'.

. . . .

OT . . . attempts to explain why outputs may differ from inputs. It does so by encoding markedness directly into the grammar. Most constraints are formulated negatively and penalize the markedness of undesirable results; they point to marked structures or articulations, and their paraphrases read like lists of what not to do; for instance 'avoid (marked) sonority differentials', 'avoid (marked) complex articulations', 'avoid (marked) labial codas'. These markedness constraints make no reference to the input, they simply evaluate the intrinsic desirability of outputs.

Be penalising marked constructs, markedness constraints optimise language towards ease of articulation and simple structures. Assimilations and mergers usually respond to the desire to minimise effort. But this is counterbalanced by the need to keep articulations clear, words distinct and intonations contrastive. Effective communication, and language use in general, attempts to reach a satisfactory equilibrium between the drive to simplify phonetic forms and the need to be understood. In OT, this balance is achieved by pitting against each other markedness constraints and faithfulness constraints.

この観点からすると,最適化理論が目指す「最適」とは,話し手と聞き手の相反するニーズを最大限に調整した結果としての出力を指すとも解釈できる.

・ Carr, Philip and Jean-Pierre Montreuil. Phonology. 2nd ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

2019-11-18 Mon

■ #3857. 『英語教育』の連載第9回「なぜ英語のスペリングには黙字が多いのか」 [rensai][notice][silent_letter][consonant][spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][sound_change][phonetics][etymological_respelling][latin][standardisation][sobokunagimon][link]

11月14日に,『英語教育』(大修館書店)の12月号が発売されました.英語史連載「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ」の第9回となる今回の話題は「なぜ英語のスペリングには黙字が多いのか」です.

黙字 (silent_letter) というのは,climb, night, doubt, listen, psychology, autumn などのように,スペリング上は書かれているのに,対応する発音がないものをいいます.英単語のスペリングをくまなく探すと,実に a から z までのすべての文字について黙字として用いられている例が挙げられるともいわれ,英語学習者にとっては実に身近な問題なのです.

今回の記事では,黙字というものが最初から存在したわけではなく,あくまで歴史のなかで生じてきた現象であること,しかも個々の黙字の事例は異なる時代に異なる要因で生じてきたものであることを易しく紹介しました.

連載記事を読んで黙字の歴史的背景の概観をつかんでおくと,本ブログで書いてきた次のような話題を,英語史のなかに正確に位置づけながら理解することができるはずです.

・ 「#2518. 子音字の黙字」 ([2016-03-19-1])

・ 「#1290. 黙字と黙字をもたらした音韻消失等の一覧」 ([2012-11-07-1])

・ 「#34. thumb の綴りと発音」 ([2009-06-01-1])

・ 「#724. thumb の綴りと発音 (2)」 ([2011-04-21-1])

・ 「#1902. 綴字の標準化における時間上,空間上の皮肉」 ([2014-07-12-1])

・ 「#1195. <gh> = /f/ の対応」 ([2012-08-04-1])

・ 「#2590. <gh> を含む単語についての統計」 ([2016-05-30-1])

・ 「#3333. なぜ doubt の綴字には発音しない b があるのか?」 ([2018-06-12-1])

・ 「#116. 語源かぶれの綴り字 --- etymological respelling」 ([2009-08-21-1])

・ 「#1187. etymological respelling の具体例」 ([2012-07-27-1])

・ 「#579. aisle --- なぜこの綴字と発音か」 ([2010-11-27-1])

・ 「#580. island --- なぜこの綴字と発音か」 ([2010-11-28-1])

・ 「#1156. admiral の <d>」 ([2012-06-26-1])

・ 「#3492. address の <dd> について (1)」 ([2018-11-18-1])

・ 「#3493. address の <dd> について (2)」 ([2018-11-19-1])

・ 堀田 隆一 「なぜ英語のスペリングには黙字が多いのか」『英語教育』2019年12月号,大修館書店,2019年11月14日.62--63頁.

2019-10-19 Sat

■ #3827. lexical set (2) [terminology][lexicology][vowel][sound_change][phonetics][dialectology][lexical_set]

昨日の記事 ([2019-10-18-1]) に引き続き,lexical set という用語について.Swann et al. の用語辞典によると,次の通り.

lexical set A means of enabling comparisons of the vowels of different dialects without having to use any particular dialect as a norm. A lexical set is a group of words whose vowels are uniformly pronounced within a given dialect. Thus bath, brass, ask, dance, sample, calf form a lexical set whose vowel is uniformly [ɑː] in the south of England and uniformly [æː] in most US dialects of English. The phonetician J. C. Wells specified standard lexical sets, each having a keyword intended to be unmistakable, irrespective of the dialect in which it occurs (see Wells, 1982). The above set is thus referred to as 'the BATH vowel'. Wells specified twenty-four such keywords, since modified slightly by Foulkes and Docherty (1999) on the basis of their study of urban British dialects.

第1文にあるように,lexical set という概念の強みは,ある方言を恣意的に取り上げて「基準方言」として据える必要がない点にある.問題の単語群をあくまで相対的にとらえ,客観的に方言間の比較を可能ならしめている点ですぐれた概念である.この用語のおかげで,「'BATH' を典型とする,あの母音を含む単語群」を容易に語れるようになった.

・ Swann, Joan, Ana Deumert, Theresa Lillis, and Rajend Mesthrie, eds. A Dictionary of Sociolinguistics. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 2004.

2019-10-18 Fri

■ #3826. lexical set (1) [terminology][lexicology][vowel][sound_change][phonetics][dialectology][lexical_set]

音声学,方言学,語彙論の分野における重要な概念・用語として,lexical set というものがある.「#3505. THOUGHT-NORTH-FORCE Merger」 ([2018-12-01-1]) などで触れてきたが,きちんと扱ってきたことはなかったので,ここで導入しよう.Trudgill の用語辞典より引用する.

lexical set A set of lexical items --- words --- which have something in common. In discussions of English accents, this 'something' will most usually be a vowel, or a vowel in a certain phonological context. We may therefore talk abut the English 'lexical set of bath', meaning words such as bath, path, pass, last, laugh, daft where an original short a occurs before a front voiceless fricative /f/, /θ/ or /s/. The point of talking about this lexical set, rather than a particular vowel, is that in different accents of English these words have different vowels: /æ/ in the north of England and most of North America, /aː/ in the south of England, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa.

通時的には,ある音変化が,しばしばあるように,限定された音声環境においてのみ生じた場合や,あるいはその他の理由で特定の単語群のみに生じた場合に,それが生じた単語群を,その他のものと区別しつつまとめて呼びたい場合に便利である.共時的には,そのような音変化が生じた変種と生じていない変種を比較・対照する際に,注目すべき語群として取り上げるときに便利である.

要するに,音変化の起こり方には語彙を通じて斑があるものだという事実を認めた上で,同じように振る舞った(あるいは振る舞っている)単語群を束ねたとき,その単語群の単位を "lexical set" と呼ぶわけだ.たいしたことを言っているわけではないのだが,そのような単位名がついただけで,何か実質的なものをとらえられたような気がするから不思議だ.用語というのはすこぶる便利である(たたし,ときに危ういものともなり得る).

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2019-10-17 Thu

■ #3825. quoth の母音 (2) [vowel][verb][preterite][old_norse][phonetics][sound_change][analogy][inflection][spelling_pronunciation]

[2019-10-07-1]の記事で取り上げた話題について,少し調べてみた.中英語から近代英語にかけて,この動詞(過去形)の母音(字)には様々なものが認められたようだが,特に <a> や <o> で綴られたものについて,短音だったのか長音だったのかという問題がある(現代の標準的な quoth /kwoʊθ/ は長音タイプである).

これについて Dobson (II §339) に当たってみた,次の1節を参照.

It is commonly assumed, as by Sweet, New English Grammar, 則1473, that ME quod and quoth are both weak-stressed forms with rounding of ME ă; but they should be distinguished. Quod, which occurs as early as Ancrene Wisse and its group, undoubtedly has ME ŏ < ME ă rounded under weak stress (though its final d is more simply explained from the OE plural stem than, with Sweet, as a special weak-stressed development of OE þ. Quoth, on the other hand, is not a blend-form with a ModE spelling-pronunciation, as Sweet thinks; the various ModE forms (see 則421 below) suggest strongly that the vowel descends from ME, which is to be explained from ON á in the p.t.pl. kváðum. Significantly the ME quoþ form first appears in the plural quoðen in the East Anglian Genesis and Exodus (c. 1250), and next in Cursor Mundi.

この引用を私なりに解釈すると,次の通りとなる.中英語以来,この単語に関して短音と長音の両系列が並存していたが,それが由来するところは,前者については古英語の第1過去形の短母音 (cf. cwæþ) であり,後者については古ノルド語の kváðum である.語末子音(字)が th か d かという問題についても,Dobson は様々な異形態の混合・混同と説明するよりは,歴史的な継続(前者は古英語の第1過去に由来し,後者は第2過去に由来する)として解釈したいという立場のようだ.

・ Dobson, E. J. English Pronunciation 1500--1700. 1st ed. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1957.

2019-10-14 Mon

■ #3822. 『英語教育』の連載第8回「なぜ bus, bull, busy, bury の母音は互いに異なるのか」 [rensai][notice][vowel][spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][me_dialect][sound_change][phonetics][standardisation][sobokunagimon][link]

10月12日に,『英語教育』(大修館書店)の11月号が発売されました.英語史連載「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ」の第8回となる今回の話題は「なぜ bus, bull, busy, bury の母音は互いに異なるのか」です.

英語はスペリングと発音の関係がストレートではないといわれますが,それはとりわけ母音について当てはまります.たとえば,mat と mate では同じ <a> のスペリングを用いていながら,前者は /æ/,後者は /eɪ/ と発音されるように,1つのスペリングに対して2つの発音が対応している例はざらにあります.逆に同じ発音でも異なるスペリングで綴られることは,meat, meet, mete などの同音異綴語を思い起こせばわかります.

今回の記事では <u> の母音字に注目し,それがどんな母音に対応し得るかを考えてみました.具体的には bus /bʌs/, bull /bʊl/, busy /ˈbɪzi/, bury /ˈbɛri/ という単語を例にとり,いかにしてそのような「理不尽な」スペリングと発音の対応が生じてきてしまったのかを,英語史の観点から解説します.記事にも書いたように「現在のスペリングは,異なる時代に異なる要因が作用し,秩序が継続的に崩壊してきた結果の姿」です.背景には,あっと驚く理由がありました.その謎解きをお楽しみください.

今回の連載記事と関連して,本ブログの以下の記事もご覧ください.

・ 「#1866. put と but の母音」 ([2014-06-06-1])

・ 「#562. busy の綴字と発音」 ([2010-11-10-1])

・ 「#570. bury の母音の方言分布」 ([2010-11-18-1])

・ 「#1297. does, done の母音」 ([2012-11-14-1])

・ 「#563. Chaucer の merry」 ([2010-11-11-1])

・ 堀田 隆一 「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ 第8回 なぜ bus, bull, busy, bury の母音はそれぞれ異なるのか」『英語教育』2019年11月号,大修館書店,2019年10月12日.62--63頁.

2019-10-07 Mon

■ #3815. quoth の母音 [vowel][verb][preterite][verners_law][phonetics][sound_change][analogy][inflection][old_norse]

「#2130. "I wonder," said John, "whether I can borrow your bicycle."」 ([2015-02-25-1]),「#2158. "I wonder," said John, "whether I can borrow your bicycle." (2)」 ([2015-03-25-1]) で少し触れたが,quoth /kwoʊθ/ は「?と言った」を意味する古風な語である.1人称単数と3人称単数の直説法過去形のみで,原形などそれ以外の形態は存在しない妙な動詞である.古英語や中英語ではきわめて日常的かつ高頻度の動詞であり,古英語ウェストサクソン方言では強変化5類の動詞として,その4主要形は cweðan -- cwæþ -- cwǣdon -- cweden だった(「#3812. was と were の関係」 ([2019-10-04-1]) を参照).

ウェストサクソン方言の cweðan の語幹母音を基準とすると,その後の音変化により †queath などとなるはずであり,実際にこの形態は16世紀末まで用いられていたが,その後廃用となった(しかし,派生語の bequeath (遺言で譲る)を参照).したがって,現在の quoth の語幹母音は cweðan からの自然の音変化の結果とは考えられない.

OED の quoth, v. と †queath, v. を参照してみると,o の母音は,Northumbrian など非ウェストサクソン方言における後舌円唇母音を示す,同語の異形に由来するとのことだ.その背景には複雑な音変化や類推作用が働いていたようだ.OED は,quoth, v. の下で次の3点を紹介している.

(i) levelling of the rounded vowel resulting from combinative back mutation in Northumbrian Old English (see discussion at queath v.); (ii) rounding of Middle English short a (of the 1st and 3rd singular past indicative) after w; (iii) borrowing of the vowel (represented by Middle English long open ō) of the early Scandinavian plural past indicative forms (compare Old Icelandic kváðum (1st plural past indicative)); both short and long realizations are recorded by 17th-cent. orthoepists (see E. J. Dobson Eng. Pronunc. 1500--1700 (ed. 2, 1968) II. 則則339, 421).

中英語における異形については MED の quēthen v. も参照.スペリングとして hwat など妙なもの(MED は "reverse spelling" としている)も見つかり,興味が尽きない.

2019-08-28 Wed

■ #3775. 英語は開音節を目指して音変化を起こしている [sound_change][phonetics][phonology][r][l][consonant][syllable][vowel][stress][rhythm][prosody]

「#3719. 日本語は開音節言語,英語は閉音節言語」 ([2019-07-03-1]) でみたように,英語は類型論的にいえば有標の音節タイプである閉音節を多くもつ言語であることは事実だが,それでも英語の音変化の潮流を眺めてみると,英語は無標の開音節を志向していると考えられそうである.

安藤・澤田は現代英語にみられる r の弾音化 (flapping; city, data などの t が[ɾ] となる現象),l の咽頭化 (pharyngealization; feel, help などの l が暗い [ɫ] となる現象),子音の脱落(attem(p)t, exac(t)ly, mos(t) people など)といった音韻過程を取り上げ,いずれも音節末の子音が関わっており,その音節を開音節に近づける方向で生じているのではないかと述べている.以下,その解説を引用しよう (70) .

弾音化は,阻害音の /t/ を,より母音的な共鳴音に変える現象であり,これは一種の母音化 (vocalization) と考えられる.非常に早い話し方では,better [bɛ́r] のように,弾音化された /t/ が脱落することもある.また,/l/ の咽頭化では,舌全体を後ろに引く動作が加えられるが,これは本質的に母音的な動作であり,/l/ は日本語の「オ」のような母音に近づく.実際,feel [fíːjo] のように,/l/ が完全に母音になることもある.したがって,/l/ の咽頭化も,共鳴音の /l/ をさらに母音に近づける一種の母音化と考えられる.子音の脱落は,母音化ではないが,閉音節における音節末の子音連鎖を単純化する現象である.

このように,三つの現象は,いずれも,音節末の子音を母音化したり,脱落させることによって,最後が母音で終わる開音節に近づけようとしている現象であり,機能的には共通していることがわかる.〔中略〕本質的に開音節を志向する英語は,さまざまな音声現象を引き起こしながら,閉音節を開音節に近づけようとしていると考えられる.

これは音韻変化の方向性が音節構造のあり方と関連しているという説だが,その音節構造のあり方それ自身は,強勢やリズムといった音律特性によって決定されているともいわれる.これは音変化に関する壮大な仮説である.「#3387. なぜ英語音韻史には母音変化が多いのか?」 ([2018-08-05-1]),「#3466. 古英語は母音の音量を,中英語以降は母音の音質を重視した」 ([2018-10-23-1]) を参照.

・ 安藤 貞雄・澤田 治美 『英語学入門』 開拓社,2001年.

2019-06-24 Mon

■ #3710. 印欧祖語の帯気有声閉鎖音はラテン語ではおよそ f となる [indo-european][latin][sound_change][consonant][grimms_law][labiovelar][italic][greek][phonetics]

英語のボキャビルのために「グリムの法則」 (grimms_law) を学んでおくことが役に立つということを,「なぜ「グリムの法則」が英語史上重要なのか」などで論じてきたが,それと関連して時折質問される事項について解説しておきたい.印欧祖語の帯気有声閉鎖音は,英語とラテン語・フランス語では各々どのような音へ発展したかという問題である.

印欧祖語の帯気有声閉鎖音 *bh, *dh, *gh, *gwh は,ゲルマン語派に属する英語においては,「グリムの法則」の効果により,各々原則として b, d, g, g/w に対応する.

一方,イタリック語派に属するラテン語は,問題の帯気有声閉鎖音は,各々 f, f, h, f に対応する(cf. 「#1147. 印欧諸語の音韻対応表」 ([2012-06-17-1])).一見すると妙な対応だが,要するにイタリック語派では原則として帯気有声閉鎖音は調音点にかかわらず f に近い子音へと収斂してしまったと考えればよい.

実はイタリック語派のなかでもラテン語は,共時的にややイレギュラーな対応を示す.語頭以外の位置では上の対応を示さず,むしろ「グリムの法則」の音変化をくぐったような *bh > b, *dh > d, *gh > g を示すのである.ちなみにギリシア語派のギリシア語では,各々無声化した ph, th, kh となることに注意.

結果として,印欧祖語,ギリシア語,(ゲルマン祖語),英語における帯気有声閉鎖音3音の音対応は次のようになる(寺澤,p. 1660--61).

| IE | Gk | L | Gmc | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bh | phāgós | fāgus | ƀ, b | book |

| dh | thúrā | forēs (pl.) | ð, d | door |

| gh | khḗn | anser (< *hanser) | ʒ, g | goose |

この点に関してイタリック語派のなかでラテン語が特異なことは,Fortson でも触れられているので,2点を引用しておこう.

The characteristic look of the Italic languages is due partly to the widespread presence of the voiceless fricative f, which developed from the voiced aspirate[ stops]. Broadly speaking, f is the outcome of all the voiced aspirated except in Latin; there, f is just the word-initial outcome, and several other reflexes are found word-internally. (248)

The main hallmark of Latin consonantism that sets it apart from its sister Italic languages, including the closely related Faliscan, is the outcome of the PIE voiced aspirated in word-internal position. In the other Italic dialects, these simply show up written as f. In Latin, that is the usually outcome word-initially, but word-internally the outcome is typically a voiced stop, as in nebula 'cloud' < *nebh-oleh2, medius 'middle' < *medh(i)i̯o-, angustus 'narrow' < *anĝhos, and ninguit < *sni-n-gwh-eti)

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

・ Fortson IV, Benjamin W. Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow