2018-05-14 Mon

■ #3304. 規範主義が18世紀に成長した背景,2点 [language_myth][prescriptive_grammar][sociolinguistics][johnson][latin]

18世紀のイギリスに規範主義が急成長した背景について,「#1244. なぜ規範主義が18世紀に急成長したか」 ([2012-09-22-1]) をはじめとして prescriptive_grammar の記事で取り上げてきた. Aitchison は,2つの強力な社会的要因が背景にあり,規範主義がある種の宗教的な教義にまで持ち上げられたのだと考えている.その2つとは,"The first was a long-standing admiration for Latin, and the second was powerful class snobbery" (10) である.

まず,ラテン語への憧憬について.西洋においてラテン語の威信がすこぶる高かったのは,中世においてキリスト教会の言語であったこと,そして近代のルネサンス以降に学問の言語となったことによる.すでにラテン語は誰の母語でもなかったにもかかわらず,キケロのように正しく書くことが理想とされ,ラテン語教育が盛んに行なわれてきた.Ben Jonson をして "queen of tongues" と言わしめたほどであり,実際,俗語の文法が記述される際には,常にラテン語文法がモデルとされた.

このラテン語の圧倒的な威信ゆえに,俗語に対して3つの態度が生じることになった.1つは,言語には固定された正しい語法があるものだという考え方である.もう1つには,ラテン語が専ら書き言葉だったために,話し言葉に対する書き言葉の優越という見方が生じた.最後に,ラテン語が豊富な屈折を示す言語であるために,屈折を大幅に失った英語のような言語は堕落した言語であるという神話が生まれた.

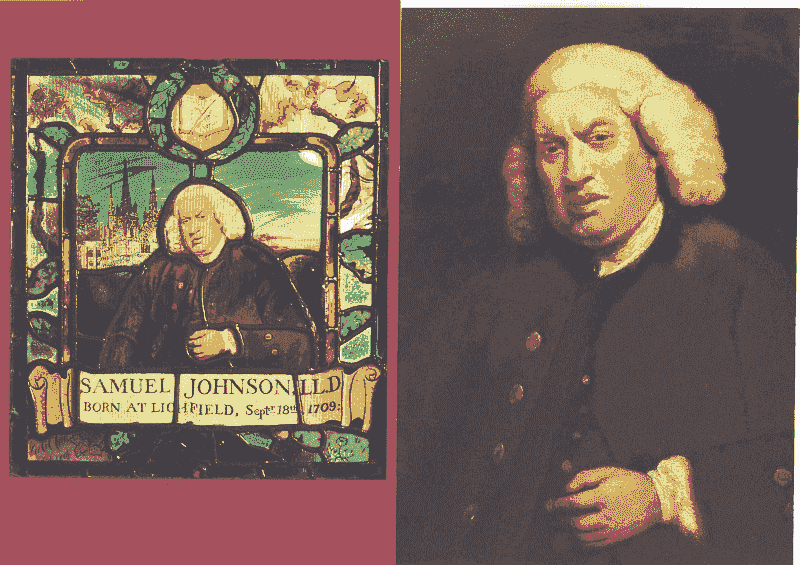

規範主義が18世紀に成長した2点目の要因は,上流崇拝である.Samuel Johnson がその典型である.Johnson は Dictionary を編纂する際に,上流階級や最良の著者が書き言葉で用いる語(法)を選んで採用し,逆に下層の人々の話し言葉についてはこき下ろした.

このような時代背景のなかで発展した規範主義と規範文法は,その後の19世紀,20世紀,21世紀にも受け継がれ,いまなお健在である.一つの神話の誕生と成長といってよいだろう.

・ Aitchison, Jean. Language Change: Progress or Decay. 4th ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2013.

2018-02-27 Tue

■ #3228. enough と enow [inflection][spelling][pronunciation][adjective][johnson][ilame]

enough の語幹は印欧祖語に遡り,ゲルマン諸語に同根語が認められる.ゲルマン祖語 *ȝanōȝaz から派生した各言語の語形は,オランダ語 genoeg, ドイツ語 genug, 古ノルド語 gnógr,ゴート語 ganōhs,そして古英語 ġenōh, ġenōg などである.

古英語後期には,語末の g は長母音の後で無声音化することが多く,/x/ と発音されるようになったと考えられる.その後,16世紀までに唇音化して /f/ となったものが,現在の enough の標準発音に連なる発音である.

一方,(語末ではなく)語中の g は上記の経路をたどらなかった.この点は重要である.というのは,形容詞としてこの語が用いられるとき,古英語と中英語においては,性・数・格に応じた屈折語尾を付加する必要があり,問題の g はたいてい語末ではなく語中に生起することになるからだ.例えば,古英語において,複数主格・対格では -e 語尾が付加されて,ġenōge という形態を取った.この形態にあっては,問題の子音は後の時代に半母音化し,さらに上げや大母音推移などの音変化を経て,近代英語までに現在の /ɪˈnaʊ/ に近い発音になっていた.enow の綴字は,こちらの発音を反映するものである.

このように,enough と enow の区別は歴史的には単数形と複数形の違いと考えることができるが,単数に enow,複数に enough を用いるような両者の混乱はすでに中英語期からあったようである.enow を退けての enough の一般化は,歴史的な区別を明確につけていた Milton のような書き手もいたものの,17世紀には確立していたとみられる (Jespersen §2.75) .

ところが,おもしろいことに1755年に出版された Johnson の辞書では,enow が enough と別の見出しで挙げられており,"The plural of enough. In a sufficient number." とある.ただし,例文として与えられているのは Sydney, Milton, Dryden, Addison などのやや古めの文献からであり,辞書出版当時に enow と enought が日常的に区別されていた証拠とするわけにはいかないだろう.

現在の辞書では,enow は《古風》というレーベルを貼られて enough の代用とされているが,上記のように,歴史的には enough の複数形に起源をもつという事実は押さえておきたい.なお,現代英語でも方言を見渡せば,enow のほうを一般化させて日常的に使用しているケースも多いことを付言しておこう.

ちなみに,enough/enow の問題と平行的に論じられる例として,plough/plow を挙げることができる.こちらについては「#1195. <gh> = /f/ の対応」 ([2012-08-04-1]) を参照.関連して,blond/blonde に見られる性による「屈折」を取りあげた「#504. 現代英語に存在する唯一の屈折する形容詞」 ([2010-09-13-1]) もどうぞ.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 2. Vol. 1. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: C. Winter's Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1922.

2018-01-27 Sat

■ #3197. 初期近代英語期の主要な出来事の年表 [timeline][history][emode][chronology][monarch][caxton][reformation][book_of_common_prayer][bible][renaissance][shakespeare][johnson]

Algeo and Pyles の英語史年表シリーズの第3弾は初期近代英語期 (153--55) .著者らは初期近代英語期を1500--1800年として区切っていることに注意.「#3193. 古英語期の主要な出来事の年表」 ([2018-01-23-1]) と「#3196. 中英語期の主要な出来事の年表」 ([2018-01-26-1]) も参照.

| 1476 | William Caxton brought printing to England, thus both serving and promoting a growing body of literate persons. Before that time, literacy was confined to the clergy and a handful of others. Within the next two centuries, most of the gentry and merchants became literate, as well as half the yeomen and some of the husbandmen. |

| 1485 | Henry Tudor ascended the throne, ending the civil strife called the War of the Roses and introducing 118 years of the Tudor dynasty, which oversaw vast changes in England. |

| 1497 | John Cabot went on a voyage of exploration for a Northwest Passage to China, in which he discovered Nova Scotia and so foreshadowed English territorial expansion overseas. |

| 1534 | The Act of Supremacy established Henry VIII as "Supreme Head of the Church of England," and thus officially put civil authority above Church authority in England. |

| 1549 | The first Book of Common Prayer was adopted and became an influence on English literary style. |

| 1558 | At the age of 25, Elizabeth I became queen of England and, as a woman with a Renaissance education and a skill for leadership, began a forty-five-year reign that promoted statecraft, literature, science, exploration, and commerce. |

| 1577--80 | Sir Francis Drake circumnavigated the globe, the first Englishman to do so, and participated in the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, removing an obstacle to English expansion overseas. |

| 1590--1611 | William Shakespeare wrote the bulk of his plays, from Henry VI to The Tempest. |

| 1600 | The East India Company was chartered to promote trade with Asia, leading eventually to the establishment of the British Raj in India. |

| 1604 | Robert Cawdrey published the first English dictionary, A Table Alphabeticall. |

| 1607 | Jamestown, Virginia, was established as the first permanent English settlement in America. |

| 1611 | The Authorized or King James Version of the Bible was produced by a committee of scholars and became, with the Prayer Book and the works of Shakespeare, one of the major examples of and influences on English literary style. |

| 1619 | The first African slaves in North America arrived in Virginia. |

| 1642--48 | The English Civil War or Puritan Revolution overthrew the monarchy and resulted in the beheading of King Charles I in 1649 and the establishment of a military dictatorship called the Commonwealth and (under Oliver Cromwell) the Protectorate, which lasted until the Restoration of King Charles II in 1660. |

| 1660 | The Royal Society was founded as the first English organization devoted to the promotion of scientific knowledge and research. |

| 1670 | The Hudson's Bay Company was chartered for promoting trade and settlement in Canada. |

| ca. 1680 | The political parties---Whigs (named perhaps from a Scots term for 'horse drivers' but used for supporters of reform and parliamentary power) and Tories (named from an Irish term for 'outlaws' but used for supporters of conservatism and royal authority), both terms being originally contemptuous---became political forces, thus introducing party politics as a central factor in government. |

| 1688 | The Glorious Revolution was a bloodless coup in which members of Parliament invited the Dutch prince William of Orange and his wife, Mary (daughter of the reigning English king, James II), to assume the English throne, resulting in the establishment of Parliament's power over that of the monarchy. |

| 1702 | The first daily newspaper was published in London, followed by an extension of such publications throughout England and the expansion of the influence of the press in disseminating information and forming public opinion. |

| 1719 | Daniel Defoe published Robinson Crusoe, sometimes identified as the first modern novel in English, although the evolution of the genre was gradual and other works have a claim to that title. |

| 1755 | Samuels Johnson published his Dictionary of the English Language, a model of comprehensive dictionaries of English |

| 1775--83 | The American Revolution resulted in the foundation of the first independent nation of English speakers outside the British Isles. Large numbers of British loyalists left the former American colonies for Canada and Nova Scotia, introducing a large number of new English speakers there. |

| 1788 | The English first settled Australia near modern Sydney. |

初期近代英語期は,外面史的には英語の世界展開の種が蒔かれた時代であり,社会言語学的には種々の機能的な標準化が進んだ時代だったとまとめられるだろう.

・ Algeo, John, and Thomas Pyles. The Origins and Development of the English Language. 5th ed. Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

2017-12-16 Sat

■ #3155. Charles Richardson の A New Dictionary of the English Language (1836--37) [lexicography][dictionary][oed][johnson]

近代英語期の著名な辞書といえば,Johnson (1755), Webster (1828), OED (1928) が挙がるが,これらの狭間にあって埋没している感のあるのが標題の辞書である.しかし,英語辞書編纂史の観点からは,一定の評価が与えられるべきである.

Charles Richardson (1775--1865) は,ロンドンに生まれ法律を学んだが,後に語学・文学へ転向し,文献学を重視しつつ私塾で教育に携わった.Johnson の辞書に対して批判的な立場を取り,自ら辞書編纂に取り組んだ.Encyclopædia Metropolitana にて連載を開始した後,1835年より分冊の形で出版し始め,最終的には上巻 (1836) と下巻 (1837) からなる A New Dictionary of the English Language を完成させた.1839年には簡約版も出版している.

この辞書の最大の特徴は,単語の意味の歴史的発展を,定義によってではなく歴史的な引用文を用いて跡づけようとしたことである.「歴史的原則」(historical principle) にほかならない.用例採集の範囲を中英語の Robert of Gloucester, Robert Mannyng of Brunne まで遡らせ,歴史的原則の新たな地平を開いたといってよい.そして,後にこの原則を採用し,徹底させたのが OED だったわけだ.

Richardson は Webster には酷評されたという.また,"a word has one meaning, and one only" という極端な原理を信奉したために,様々な箇所に無理が生じ,語源の取り扱いに等にもみるべきものがなかった.しかし,Johnson と Webster という大辞書の後を受け,来るべき OED へのつなぎの役割を果たした存在として,英語史上記憶されるべき辞書(編纂家)ではあろう.

Knowles (141) は,Richardson の OED への辞書編纂史上の貢献を次のように述べている.

The Oxford dictionary was an outstanding work of historical scholarship, but it was not the first historical dictionary. This was Charles Richardson's A new dictionary of the English language, which appeared in 1836--7, and which attempted to trace the historical development of the meanings of words using historical quotations rather than definitions. The original intention of the Philological Society in 1857 was simply to produce a supplement to the dictionaries of Johnson and Richardson, but it was soon clear that a complete new work was required.

以上,『英語学人名辞典』 (288--89) の Charles Richardson の項を参照して執筆した.

・ Knowles, Gerry. A Cultural History of the English Language. London: Arnold, 1997.

・ 佐々木 達,木原 研三 編 『英語学人名辞典』 研究社,1995年.

2017-09-01 Fri

■ #3049. 近代英語期でもアルファベットはまだ26文字ではなかった? [alphabet][johnson]

「#3038. 古英語アルファベットは27文字」 ([2017-08-21-1]) で触れたように,英語のアルファベットは昔から変わらず26文字だったわけではないこと,歴史のなかで多少の増減を繰り返してきたものであることを述べた.では,現代の26文字となったのはいつか.答えは,近代英語期といってよい.

Johnson は,影響力のある Dictionary (1755) の序文に続く "A Grammar of the English Tongue" のなかで,英語アルファベットが24文字あるいは26文字からなっていると述べている.

Our letters are commonly reckoned twenty-four, because anciently i and j, as well as u and v, were expressed by the same character; but as those letters, which had always different powers, have now different forms, our alphabet may be properly said to consist of twenty-six letters.

Johnson の時代には,アルファベットが一般的には伝統に従って24文字のセットと考えられていたことがわかる.しかし,i/j と u/v の分化がすでに受け入れられているわけだから,それを認定してアルファベット26文字とみなすのがよい,というのが Johnson の意見だ.だが,そもそも何をもって「アルファベットの文字セット」と呼ぶべきなのか,文字形で数えるのか,文字素で数えるのか,などの細かい基準については定められているわけでもないので,文字セットの問題はあくまで緩く考えておく必要があるだろう.

Johnson は上のように理屈のうえでは26文字としながらも,Dictionary の配列では,i/j とマージしているし,u/v についても同様である.配列レベルでは,これらを計4文字と数えずに計2文字と数えていることになる.例えば,inwreathe の見出し後に job が続くし,vizier の後に ulcer が続いている.この配列法はその後の辞書でもしばらく踏襲されたが,1820年代にようやく現代人が慣れ親しんでいる26文字のフォーマットで配列されるようになる (Crystal 191) .英語アルファベットはどのように数えても26文字という認識が定着したのは,つい200年ほど前のことである.

・ Crystal, David. Spell It Out: The Singular Story of English Spelling. London: Profile Books, 2012.

2017-07-12 Wed

■ #2998. 18世紀まで印刷と手書きの綴字は異なる世界にあった [spelling][orthography][writing][printing][lmode][johnson]

昨日の記事「#2997. 1800年を境に印刷から消えた long <s>」 ([2017-07-11-1]) の最後に触れたように,十分に現代英語に近いと感じられる18世紀でも(そして部分的に19世紀ですら),印刷と手書きは,文字や綴字の規範に関して,2つの異なる世界を構成していたといってよい.換言すれば,2つの正書法が存在していた(しかも,各々は現代的な意味での水も漏らさぬ強固な規範というわけではなかった).印刷はおよそ「公」であり,手書きは「私」であるから,正書法は公私で使い分けるべき二重基準となっていたのである.

この差異が最も印象的に見られるのは,Johnson の辞書での綴字と,Johnson の私的書簡での綴字である.例えば,Johnson は辞書での綴字とは異なり,書簡では companiable, enervaiting, Fryday, obviateing, occurences, peny, pouns, stiched, chappel, diner, dos (= does) 等の綴字を書いている (Tieken-Boon van Ostade 42) .このような状況は他の作家についても同様に見られることから,Johnson が綴り下手だったとか,自己矛盾を起こしているなどという結論にはならない.むしろ,公的な印刷と私的な手書きとで異なる綴字の基準があり,それが当然視されていた,ということである.

このような状況は,現代の我々にとっては理解しにくいかもしれないが,当時の綴字教育の現状を考えてみれば自然のことである.後期近代英語期には綴字の教科書は多く出版されたが,それは子供たちに印刷されたテキストを読めるようにするための教科書であり,子供たちが自ら綴字を書くことを訓練する教科書ではなかった.印刷テキストの綴字は,印刷業者によって慣習的に定められた正書法が反映されており,子供たちはその体系的な綴字を「読む」訓練こそ受けたが,「書く」訓練は特に受けていなかった.そのような子供たちが手書きで書簡を認める段には,当然ながら印刷テキストに表わされている正書法に則って綴ることはできない.しかし,だからといって単語をまったく綴れないということにはならないし,書簡の受け手に誤解されることもほとんどないだろう.

そして,この状況は,綴字を学んでいる子供たちのみならず,文字を読み書きする大人たちにも一般に当てはまった.印刷と手書きの対立は,公私の対立のみならず,綴字を読む能力と書く能力の対立でもあったのだ.

・ Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. An Introduction to Late Modern English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2009.

2016-11-28 Mon

■ #2772. 標準化と規範化の試みは,語彙→文法→発音の順序で (1) [standardisation][prescriptivism][prescriptive_grammar][emode][pronunciation][orthoepy][dictionary][lexicography][rp][johnson][lowth][orthoepy][orthography][walker]

中英語の末期から近代英語の半ばにかけて起こった英語の標準化と規範化の潮流について,「#1237. 標準英語のイデオロギーと英語の標準化」 ([2012-09-15-1]),「#1244. なぜ規範主義が18世紀に急成長したか」 ([2012-09-22-1]),「#2741. ascertaining, refining, fixing」 ([2016-10-28-1]) を中心として,standardisation や prescriptive_grammar の各記事で話題にしてきた.この流れについて特徴的かつ興味深い点は,時代のオーバーラップはあるにせよ,語彙→文法→発音の順に規範化の試みがなされてきたことだ.

イングランド,そしてイギリスが,国語たる英語の標準化を目指してきた最初の部門は,語彙だった.16世紀後半は語彙を整備していくことに注力し,その後17世紀にかけては,語の綴字の規則化と統一化に焦点が当てられるようになった.語彙とその綴字の問題は,17--18世紀までにはおよそ解決しており,1755年の Johnson の辞書の出版はだめ押しとみてよい.(関連して,「#1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題」 ([2013-03-04-1]),「#2321. 綴字標準化の緩慢な潮流」 ([2015-09-04-1]) を参照).

次に標準化・規範化のターゲットとなったのは,文法である.18世紀には規範文法書の出版が相次ぎ,その中でも「#2583. Robert Lowth, Short Introduction to English Grammar」 ([2016-05-23-1]) や「#2592. Lindley Murray, English Grammar」 ([2016-06-01-1]) が大好評を博した.

そして,やや遅れて18世紀後半から19世紀にかけて,「正しい発音」へのこだわりが感じられるようになる.理論的な正音学 (orthoepy) への関心は,「#571. orthoepy」 ([2010-11-19-1]) で述べたように16世紀から見られるのだが,実践的に「正しい発音」を行なうべきだという風潮が人々の間でにわかに高まってくるのは18世紀後半を待たなければならなかった.この部門で大きな貢献をなしたのは,「#1456. John Walker の A Critical Pronouncing Dictionary (1791)」 ([2013-04-22-1]) である.

「正しい発音」の主張がなされるようになったのが,18世紀後半という比較的遅い時期だったことについて,Baugh and Cable (306) は次のように述べている.

The first century and a half of English lexicography including Johnson's Dictionary of 1755, paid little attention to pronunciation, Johnson marking only the main stress in words. However, during the second half of the eighteenth century and throughout the nineteenth century, a tradition of pronouncing dictionaries flourished, with systems of diacritics indicating the length and quality of vowels and what were considered the proper consonants. Although the ostensible purpose of these guides was to eliminate linguistic bias by making the approved pronunciation available to all, the actual effect was the opposite: "good" and "bad" pronunciations were codified, and speakers of English who were not born into the right families or did not have access to elocutionary instruction suffered linguistic scorn all the more.

では,近現代英語の標準化と規範化の試みが,語彙(綴字を含む)→文法→発音という順序で進んでいったのはなぜだろうか.これについては明日の記事で.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-11-16 Wed

■ #2760. イタリアとフランスのアカデミーと,それに相当する Johnson の力 [prescriptivism][academy][johnson][italian][french][dictionary][lexicography][popular_passage]

昨日の記事「#2759. Swift によるアカデミー設立案が通らなかった理由」 ([2016-11-15-1]) と関連して,英語アカデミー設立案にインスピレーションを与えたイタリアとフランスの先例と,それに匹敵する Johnson の辞書の価値について論じたい.

イギリスが英語アカデミーを設立しようと画策したのは,すでにイタリアとフランスにアカデミーの先例があったから,という理由が大きい.近代ヨーロッパ諸国は国語を「高める」こと (cf. 「#2741. ascertaining, refining, fixing」 ([2016-10-28-1])) に躍起であり,アカデミーという機関を通じてそれを実現しようと考えていた.先鞭をつけたのはイタリアである.イタリアには様々なアカデミーがあったが,最もよく知られているのは1582年に設立された Accademia della Crusca である.この機関は,1612年に Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca という辞書を出版し,何かと物議を醸したが,その後も改訂を重ねて,1691年には3冊分,1729--38年版では6冊分にまで成長した (Baugh and Cable 257) .

フランスでは,1635年に枢機卿 Richelieu がある文学サロンに特許状を与え,その集団(最大40名)は l'Académie française として知られるようになった.この機関は,辞書や文法書を編集することを目的の1つとして掲げており,作業は遅々としていたものの,1694年には辞書が出版されるに至った (Baugh and Cable 257) .

このように,イタリアやフランスでは17世紀中にアカデミーの力により業績が積み上げられていたが,同じ頃,イギリスではアカデミー設立の提案すらなされていなかったのである.その後,1712年に Swift により提案がなされたが,結果として流れた経緯については昨日の記事で述べた.しかし,さらに後の1755年には,アカデミーによらず,Johnson 個人の力で,イタリア語やフランス語の辞書に匹敵する英語の辞書が出版されるに至った.Johnson の知人 David Garrick は,次のエピグラムを残している (Baugh and Cable 267) .

And Johnson, well arm'd like a hero of yore,

Has beat forty French, and will beat forty more.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-11-15 Tue

■ #2759. Swift によるアカデミー設立案が通らなかった理由 [swift][prescriptivism][academy][lowth][johnson]

Swift による A Proposal for Correcting, Improving and Ascertaining the English Tongue (1712) は,英語のアカデミー (academy) 設立に向けて最も近いところまで迫る試みだった.すでに17世紀前半には英語アカデミーを求める声は上がっており,18世紀初頭の Swift の提案においてピークを迎えたにせよ,その後の18世紀中もアカデミー設立の要求はそう簡単には消滅しなかった.しかし,歴史を振り返ってみれば,Swift の提案が通らなかったことにより,アカデミー設立案が永遠に潰えることになった,とは言ってよいだろう.では,なぜ Swift の提案は流れたのだろうか.

そこには,個人的で政治的な論争や Anne 女王の死という事情があった.Baugh and Cable (262) に次のように述べられている.

Apparently the only dissenting voice was that of John Oldmixon, who, in the same year that Swift's Proposal appeared, published Reflections on Dr. Swift's Letter to the Earl of Oxford, about the English Tongue. It was a violent Whig attack inspired by purely political motives. He says, "I do here in the Name of all the Whigs, protest against all and everything done or to be done in it, by him or in his Name." Much in the thirty-five pages is a personal attack on Swift, in which he quotes passages from the Tale of a Tub as examples of vulgar English, to show that Swift was no fit person to suggest standards for the language. And he ridicules the idea that anything can be done to prevent languages from changing. "I should rejoice with him, if a way could be found out to fix our Language for ever, that like the Spanish cloak, it might always be in Fashion." But such a thing is impossible.

Oldmixon's attack was not directed against the idea of an academy. He approves of the design, "which must be own'd to be very good in itself." Yet nothing came of Swift's Proposal. The explanation of its failure in the Dublin edition is probably correct; at least it represented contemporary opinion. "It is well known," it says, "that if the Queen had lived a year or two longer, this proposal would, in all probability, have taken effect. For the Lord Treasurer had already nominated several persons without distinction of quality or party, who were to compose a society for the purposes mentioned by the author; and resolved to use his credit with her majesty, that a fund should be applied to support the expense of a large room, where the society should meet, and for other incidents. But this scheme fell to the ground, partly by the dissensions among the great men at court; but chiefly by the lamented death of that glorious princess."

つまり,Swift の提案の内容それ自体が問題だったというわけではないのである.アカデミー設立は多くの人々の願いでもあったし,事は着々と進んでいた.ただ,政治的な点において Swift に反対する人物が声高に叫び,意見の不一致が生まれたということ,そして何よりも,アカデミー設立に向けて動き出していた Anne 女王が1714年に亡くなったことが,Swift の運の尽きだった.

「上から」の英語アカデミーがついに作られなかったことにより,18世紀からは「下から」の言語規範の策定が進んでいくことになる (see 「#2583. Robert Lowth, Short Introduction to English Grammar」 ([2016-05-23-1]), 「#1421. Johnson の言語観」 ([2013-03-18-1]), 「#141. 18世紀の規範は理性か慣用か」 ([2009-09-15-1])) .イギリスは,アカデミーを作る意志がなかったわけではなく,半ば歴史の偶然で作るに至らなかった,と評価するのが適切だろう.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-10-28 Fri

■ #2741. ascertaining, refining, fixing [prescriptivism][prescriptive_grammar][standardisation][swift][johnson][language_myth][academy]

英語史上有名な Swift による A Proposal for Correcting, Improving and Ascertaining the English Tongue (1712) では,題名に3つの異なる動詞 correct, improve, ascertain が用いられている.英語を「訂正」し,「改善」し,「確定する」ことを狙ったものであることが分かる.「英語の言葉遣いをきっちりと定める」という点では共通しているが,これらの動詞の間にはどのような含意の差があるのだろうか.correct には「誤りを指摘して正しいものに直す」という含意があり,improve には「より良くする」,そして ascertain には古い語義として「確定させる」ほどの意味が感じられる.

この3つの動詞とぴったり重なるわけではないが,Swift の生きた規範主義の時代に,「英語の言葉遣いをきっちりと定める」ほどの意味でよく用いられた,もう1揃いの3動詞がある.ascertain, refine, fix の3つだ.Baugh and Cable (251) によれば,それぞれは次のような意味で用いられる.

・ ascertain: "to reduce the language to rule and set up a standard of correct usage"

・ refine: "to refine it--- that is, to remove supposed defects and introduce certain improvements"

・ fix: "to fix it permanently in the desired form"

「英語の言葉遣いをきっちりと定める」点で共通しているように見えるが,注目している側面は異なる.ascertain はいわゆる理性的で正しい標準語の策定を狙ったもので,Johnson は ascertainment を "a settled rule; an established standard" と定義づけている.具体的にいえば,決定版となる辞書や文法書を出版することを指した.

次に,refine はいわばより美しい言葉遣いを目指したものである.当時の知識人の間には Chaucer の時代やエリザベス朝の英語こそが優雅で権威ある英語であるというノスタルジックな英語観があり,当代の英語は随分と堕落してしまったという感覚があったのである.ここには,「#1947. Swift の clipping 批判」([2014-08-26-1]) や「#1948. Addison の clipping 批判」 ([2014-08-27-1]) も含まれるだろう.

最後に,fix は一度確定した言葉遣いを永遠に凍結しようとしたもの,ととらえておけばよい.Swift を始めとする18世紀前半の書き手たちは,自らの書いた文章が永遠に凍結されることを本気で願っていたのである.今から考えれば,まったく現実味のない願いではある (cf. 「#1421. Johnson の言語観」 ([2013-03-18-1])) .

18世紀の規範主義者の間には,どの側面に力点を置いて持論を展開しているのかについて違いが見られるので,これらの動詞とその意味は区別しておく必要がある.

最近「美しい日本語」が声高に叫ばれているが,これは日本語について ascertain, refine, fix のいずれの側面に対応するものなのだろうか.あるいは,3つのいずれでもないその他の側面なのだろうか.よく分からないところではある.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-07-29 Fri

■ #2650. 17世紀末の質素好みから18世紀半ばの華美好みへ [rhetoric][style][johnson]

文学史・文体論史では,17世紀終わりから18世紀終わりの Augustan Period において,特にその前半は,質素な文体が好まれたといわれる.しかし,18世紀前半から,地味な文体に飽き足りず,少しずつ派手好みの文体に挑戦する文筆家が現われていた.ラテン語の華美な魅力に耐えられず,派手さを喧伝する書き手が現われたのだ.その新しい方針を採った文豪の1人が Samuels Johnson である.彼こそが18世紀半ばの華美好みの書き手の代表者となったということから,この文体の潮流の変化は "Johnson's Latinate Revival" ともいわれる.

18世紀中に文体や使用する語種に変化があったことは,明らかである.Knowles (137) によれば,

The typical prose style of the period following the Restoration of the monarchy . . . was essentially unadorned. This plainness of style was a reaction to the taste of the preceding period. Early in the eighteenth century taste began to change again, and there are suggestions that ordinary language is not really sufficient for high literature. Addison in the Spectator (no. 285) argues: 'many an elegant phrase becomes improper for a poet or an orator, when it has been debased by common use.' By the middle of the century, Lord Chesterfield argues for a style raised from the ordinary; in a letter to his son he writes: 'Style is the dress of thoughts, and let them be ever so just, if your style is homely, coarse, and vulgar, they will appear to as much disadvantage, and be as ill-received as your person, though ever so well proportioned, would, if dressed in rags, dirt and tatters.' At this time, Johnson's dictionary appeared, followed by Lowth's grammar and Sheridan's lectures on elocution. By the 1760s, at the beginning of the reign of George III, the elevated style was back in fashion.

The new style is associated among others with Samuel Johnson. Johnson echoes Addison and Chesterfield: 'Language is the dress of thought . . . and the most splendid ideas drop their magnificence, if they are conveyed by words used commonly upon low and trivial occasions, debased by vulgar mouths, and contaminated by inelegant applications' . . . . This gives rise to the belief that the language of important texts must be elevated above normal language use. Whereas in the medieval period Latin was used as the language of record, in the late eighteenth century Latinate English was used for much the same purpose.

ここで述べられているように,Augustan Period の前半は社会は保守的であり,その余波は言語的にも明らかである.例えば,OED でも他の時代に比べて新語があまり現われていない(cf. 「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1]),「#203. 1500--1900年における英語語彙の増加」 ([2009-11-16-1])).しかし,Augustan periods の後半,18世紀後半には前時代からの反動で,Johnson に代表される華美な語法が流行となるに至る.その2世紀前に "aureate diction" (cf. 「#292. aureate diction」 ([2010-02-13-1])) があったのと同様に,もう1度同種の流行がはびこったのである.

文体や語彙借用に関する限り,英語史においてこの繰り返しは何度となく起こっている.これは,例えば日本における漢字を重視する傾向のリバイバルなどと似たような事情でなないだろうか.

・ Knowles, Gerry. A Cultural History of the English Language. London: Arnold, 1997.

2016-03-11 Fri

■ #2510. Johnson の導入した2種類の単語・綴字の(非)区別 [johnson][spelling][orthography][lexicography][doublet][latin][french][etymology]

Samuel Johnson (1709--84) の A Dictionary of the English Language (1755) は,英語史上の語彙や綴字の問題に関する話題の宝庫といってよい.その辞書とこの大物辞書編纂者については,「#1420. Johnson's Dictionary の特徴と概要」 ([2013-03-17-1]),「#1421. Johnson の言語観」 ([2013-03-18-1]) ほか,johnson の記事ほかで話題を提供してきた.今回は,現代英語の書き手にとって厄介な practice (名詞)と practise (動詞)のような2種類の単語・綴字の区別について,Johnson が関与していることに触れたい.

Horobin (148) によれば,中英語では practice も practise も互いに交換可能なものとして用いられていたが,Johnson の辞書の出版により現代の区別が確立したとしている.Johnson は見出し語として名詞には practice を,動詞には practise を立てており,意識的に区別をつけている.ところが,Johnson 自身が辞書の別の部分では品詞にかかわらず practice の綴字を好んだ形跡がある.例えば,To Cipher の定義のなかに "To practice arithmetick" とあるし,Coinage の定義として "The act or practice of coining money" がみられる.

Johnson が導入した区別のもう1つの例として,council と counsel が挙げられる.この2語は究極的には語源的なつながりはなく,各々はラテン語 concilium (集会)と consilium (助言)に由来する.しかし,中英語では意味的にも綴字上も混同されており,交換可能といってよかった.ところが,語源主義の Johnson は,ラテン語まで遡って両者を区別することをよしとしたのである (Horobin 149) .

さらにもう1つ関連する例を挙げれば,現代英語では非常に紛らわしい2つの形容詞 discreet (思慮のある)と discrete (分離した)の区別がある.両語は語源的には同一であり,2重語 (doublet) を形成するが,中英語にはいずれの語義においても,フランス語形 discret を反映した discrete の綴字のほうがより普通だった.ところが,16世紀までに discreet の綴字が追い抜いて優勢となり,とりわけ「思慮深い」の語義においてはその傾向が顕著となった.この2つの形容詞については,Johnson が直に区別を導入したというわけではなかったが,辞書を通じてこの区別を広め確立することに貢献はしただろう (Horobin 149) .

このように Johnson は語源主義的なポリシーを遺憾なく発揮し,現代にまで続く厄介な語のペアをいくつか導入あるいは定着させたが,妙なことに,現代ではつけられている区別が Johnson では明確には区別されていないという逆の例もみられるのだ.「#2440. flower と flour (2)」 ([2016-01-01-1]) で取り上げた語のペアがその1例だが,ほかにも現代の licence (名詞)と license (動詞)の区別に関するものがある.Johnson はこの2語をまったく分けておらず,いずれの品詞にも license の綴字で見出しを立てている.Johnson 自身が指摘しているように名詞はフランス語 licence に,動詞はフランス語 licencier に由来するということであれば,語源主義的には,いずれの品詞でも <c> をもつ綴字のほうがふさわしいはずだと思われるが,Johnson が採ったのは,なぜか逆のほうの <s> である (Horobin 148) .Johnson は,時々このような妙なことをする.なお,defence という名詞の場合にも,Johnson は起源がラテン語 defensio であることを正しく認めていたにもかかわらず,<c> の綴字を採用しているから,同じように妙である (Horobin 149) .Johnson といえども,人の子ということだろう.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2016-03-05 Sat

■ #2504. Simon Horobin の "A history of English . . . in five words" [link][hel_education][anglo-saxon][french][loan_word][lexicology][lexicography][johnson]

2月23日付けで,オックスフォード大学の英語史学者 Simon Horobin による A history of English . . . in five words と題する記事がウェブ上にアップされた.英語に現われた年代順に English, beef, dictionary, tea, emoji という5単語を取り上げ,英語史的な観点からエッセー風にコメントしている.ハイパーリンクされた語句や引用のいずれも,英語にまつわる歴史や文化の知識を増やしてくれる良質の教材である.こういう記事を書きたいものだ.

以下,5単語の各々について,本ブログ内の関連する記事にもリンクを張っておきたい.

1. English or Anglo-Saxon

・ 「#33. ジュート人の名誉のために」 ([2009-05-31-1])

・ 「#389. Angles, Saxons, and Jutes の故地と移住先」 ([2010-05-21-1])

・ 「#1013. アングロサクソン人はどこからブリテン島へ渡ったか」 ([2012-02-04-1])

・ 「#1145. English と England の名称」 ([2012-06-15-1])

・ 「#1436. English と England の名称 (2)」 ([2013-04-02-1])

・ 「#2353. なぜアングロサクソン人はイングランドをかくも素早く征服し得たのか」 ([2015-10-06-1])

・ 「#2493. アングル人は押し入って,サクソン人は引き寄せられた?」 ([2016-02-23-1])

2. beef

・ 「#331. 動物とその肉を表す英単語」 ([2010-03-24-1])

・ 「#332. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」の神話」 ([2010-03-25-1])

・ 「#1583. swine vs pork の社会言語学的意義」 ([2013-08-27-1])

・ 「#1603. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」を最初に指摘した人」 ([2013-09-16-1])

・ 「#1604. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」を次に指摘した人たち」 ([2013-09-17-1])

・ 「#1966. 段々おいしくなってきた英語の飲食物メニュー」 ([2014-09-14-1])

・ 「#1967. 料理に関するフランス借用語」 ([2014-09-15-1])

・ 「#2352. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」の神話 (2)」 ([2015-10-05-1])

3. dictionary

・ 「#603. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (1)」 ([2010-12-21-1])

・ 「#604. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (2)」 ([2010-12-22-1])

・ 「#609. 難語辞書の17世紀」 ([2010-12-27-1])

・ 「#610. 脱難語辞書の18世紀」 ([2010-12-28-1])

・ 「#726. 現代でも使えるかもしれない教育的な Cawdrey の辞書」 ([2011-04-23-1])

・ 「#1420. Johnson's Dictionary の特徴と概要」 ([2013-03-17-1])

・ 「#1421. Johnson の言語観」 ([2013-03-18-1])

・ 「#1609. Cawdrey の辞書をデータベース化」 ([2013-09-22-1])

4. tea

・ 「#756. 世界からの借用語」 ([2011-05-23-1])

・ 「#1966. 段々おいしくなってきた英語の飲食物メニュー」 ([2014-09-14-1])

5. emoji

・ 「#808. smileys or emoticons」 ([2011-07-14-1])

・ 「#1664. CMC (computer-mediated communication)」 ([2013-11-16-1])

英語語彙全般については,「#756. 世界からの借用語」 ([2011-05-23-1]), 「#1526. 英語と日本語の語彙史対照表」 ([2013-07-01-1]) をはじめとして,lexicology や loan_word などの記事を参照.

2016-01-01 Fri

■ #2440. flower と flour (2) [doublet][spelling][shakespeare][johnson][orthography][standardisation]

年が明けました.2016年も hellog を続けます.新年の一発目は,以前にも「#183. flower と flour」 ([2009-10-27-1]) で取り上げた話題でお届けします.

この2つの単語は,先の記事で説明したように,もともと1つの語のなかの2つの異なる語義だった.しかし,おそらく語義が離れすぎてしまったために,多義語としてではなく同音異義語として認識されるようになり,少なくとも綴字上は区別するのがふさわしいと感じられるようになったのだろう,近代英語期には綴り分ける傾向が生じていた.

さて,この語が「花」の意味でフランス語から借用されたのは13世紀初頭のことである.MED の flour (n.(1)) によれば,"c1230(?a1200) *Ancr. (Corp-C 402) 92a: & te treou .. bringeð forð misliche flures .. uertuz beoð .. swote i godes nease, smeallinde flures." が初例である.一方,関連する「小麦粉(=粉のなかの最も上等の「華」)」の意味でも13世紀半ばには英語で初例が現われている.MED の flour (n.(2)) によれば," a1325(c1250) Gen. & Ex. (Corp-C 444) 1013: Kalues fleis and flures bred..hem ðo sondes bed." が初例となっている.見出し語の綴字や例文の綴字を見ればわかるように,当初はいずれの語義においても <flour> や <flur> が普通だった.

その後,近代英語では両語義の関係が不明瞭となり,「花」が「小麦粉」から分化して,中英語以来のマイナーな異綴字であった <flower> を採用するようになった.綴字上の棲み分けは意外と遅く18世紀頃のことだったが,その後も19世紀までは「小麦粉」が <flower> と綴られるなどの混用がみられた.綴り分けるか否かは,個人によっても異なっていたようで,Shakespeare や Cruden の Concordance to the Bible (1738) では現在のような区別が付けられていたが,Johnson の辞書では,いまだ flower という1つの見出しのもとに両語義が収められている.OED の flour, n. の語源欄でも "Johnson 1755 does not separate the words, nor does he recognize the spelling flour." と述べられているが,Horobin (150) が指摘しているように Johnson の辞書の biscotin の定義のなかでは "A confection made of flour, sugar, marmalade, eggs. Etc." のように <flour> が使用されている.綴り分けが定着するには,ある程度の時間がかかったということだろう.標準綴字の定着,正書法の確立は,かくも心許なく緩慢な過程である.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2015-01-25 Sun

■ #2099. fault の l [etymological_respelling][spelling][pronunciation][dialect][johnson]

「#192. etymological respelling (2)」 ([2009-11-05-1]) のリストにあるとおり,現代英語の fault の綴字に l が含まれているのは語源的綴字によるものである.語源的綴字は典型的には初期近代英語期のラテン語熱の高まった時代の所産といわれるが,実はもっと早い例も少なくない.fault も14世紀末の Gower ((a1393) Gower CA (Frf 3) 6.286) に "As I am drunke of that I drinke, So am I ek for falte of drinke." として初出する.実在のラテン単語で直接の起源とされる語はないが,仮説形 *fallitum が立てられている.フランス語でも15--17世紀に faute や faulte の形で現われている.英語で l を含む綴字が標準となったのは17世紀以降だが,発音における /l/ の挙動はその前後で安定しなかった.

OED によると,17--18世紀の Pope や Swift において fault が thought や wrought と脚韻を踏んでいたというし,1855年の Johnson の辞書にも "The l is sometimes sounded, and sometimes mute. In conversation it is generally suppressed." と注意書きがある.fault と似たような環境にある l は,近代の正音学者にとっても問題の種だったようで,その様子を Dobson (Vol. 2, §425. fn. 5) がよく伝えている.

Balm, calm, palm, almond, falcon, salmon, &c. should by etymology have no [l], being from OF baume, &c., and normally are recorded without [l]. But some of them had 'learned' OF forms, adopted directly from Latin, which retained [l] . . ., and others came to be spelt with l partly on etymological grounds and partly on the model of psalm, &c., spelt with but pronounced without l; and from the OF 'learned' variants, and perhaps partly from the spelling in combination with the variation in pronunciation in psalm, &c., there arose pronunciations with ME aul, recorded by Salesbury in calm, Bullokar in almond, balm, and calm, Gil in balm (as a 'learned' variant), and Daines in calm (as a variant). . . .

Variation between pronunciations with and without l in such native words as malt and salt has clearly aided the establishment of the spelling-pronunciations with [l] in fault and vault, in which the orthoepists regularly show the l to be silent, with the following exceptions. Hart once retains l in faults, probably by error; Gil says that most omit the l, but some -pronounce it, and twice gives transcriptions with l elsewhere (in Luick's copy of the 1619 edition a transcription faut is corrected by hand to falt); Tonkis fails to say that the l is silent, and the anonymous reviser (1684) of T. Shelton's Tachygraphy does not omit it (in contrast to this treatment of, for example, balm); and Hodges relegates to his 'near alike' list the paring of fault and fought. Bullokar twice transcribes vault without l, but once retains it.

fault について近代方言に目を移すと,English Dialect Dictionary には,"FAULT, sb. and v. Var. dial. uses in Sc. Irel. Eng. and Amer. Also in forms faut Sc. Ir. n.Yks.2 e.Yks. n.Lin.1 War. Shr.1 2 Som. w.Som.1; faute Sc.; fowt Suf. [folt, fat, f$t, fout.]" と記載されてあり,数多くの方言に l なしの形態が分布していることがわかる.

現代標準英語の発音は /fɔːlt/ で安定しており,通常は何の問題意識も生じないだろうが,標準から目をそらせば,そこには別の物語が広がっている.fault を巡る語源的綴字現象の余波は,始まってから数世紀たった今も,確かに続いているのである.

・ Dobson, E. J. English Pronunciation 1500--1700. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Oxford: OUP, 1968.

2014-12-28 Sun

■ #2071. <dispatch> vs <despatch> [spelling][johnson][corpus][clmet]

標記の語の綴字は,前者の <dispatch> が標準的とされるが,特にイギリス英語では後者の <despatch> も用いられる.辞書では両方記載されているのが普通で,後者が特に非標準的であるという記述はない.しかし,規範家のなかには後者を語源的な観点から非難する向きもあるようだ.この問題について Horobin (230--31) は次のように述べている.

The preference for dispatch over despatch is similarly debatable, given that despatch is recorded as an alternative spelling for dispatch by the OED. The spelling dispatch is certainly to be preferred on etymological grounds, since its prefix derives from Latin dis-; the despatch spelling first appeared by mistake in Johnson's Dictionary. However, since the nineteenth century despatch has been in regular usage and continues to be widely employed today. Given this, why should despatch not be used in The Guardian? In fact, a search of this newspaper's online publication shows that occurrences of despatch do sneak into the paper: while dispatch is clearly the more frequent spelling (almost 14,000 occurrences when I carried out the search), there were almost 2,000 instances of the proscribed spelling despatch.

引用にあるとおり,事の発端は Johnson の辞書の記述らしい.確かに Johnson は見出し語として <despatch> を掲げており,語源欄ではフランス語 depescher を参照している.しかし,この接頭辞の母音はロマンス諸語では <i> か <e> かで揺れていたのであり,Johnson の <e> の採用を語源に照らして "mistake" と呼べるかどうかは疑問である.もともとラテン語ではこの語は文証されていないし,イタリア語では dispaccio,フランス語では despeechier などの綴字が行われていた.英語の綴字を決める際にどの語源形が参照されたかの問題であり,正誤の問題ではない.また,Johnson は辞書以外の自らの著作においては一貫して <dispatch> を用いており,いわば二重基準の綴り手だったことを注記しておきたい.

<despatch> の拡大の背景に Johnson の辞書があったということは,実証することは難しいものの,十分にありそうだ.後期近代英語コーパス CLMET3.0 で70年ごとに区切った3期における両系統の綴字の生起頻度を取ってみると,次のように出た.

| Period (subcorpus size) | <dispatch> etc. | <despatch> etc. |

|---|---|---|

| 1710--1780 (10,480,431 words) | 403 | 354 |

| 1780--1850 (11,285,587) | 145 | 267 |

| 1850--1920 (12,620,207) | 67 | 263 |

この調査結果が示唆するのは,当初は <dispatch> が比較的優勢だったものの,時代が下るにつれ相対的に <despatch> が目立ってくるという流れだ.すでに18世紀中に両綴字は肉薄していたようだが,同世紀半ばの Johnson の辞書が契機となって <despatch> がさらに勢いを得たという可能性は十分にありそうだ.

20世紀の調査はしていないが,おそらく,いかにもラテン語風の接頭辞を示す <dispatch> の綴字を標準的とする規範意識が働き始め,<despatch> の肩身が狭くなってきたという顛末ではないだろうか.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2014-11-03 Mon

■ #2016. 公的な綴字と私的な綴字 [spelling][standardisation][orthography][johnson][printing][writing]

書き言葉には,formality のレベルが存在する.日本語を書くときにも,それが最終的に公的な印刷物に付される予定であれば,例えば漢字に間違いのないよう気をつけるなど,格段の注意を払うのが普通である.一方,電子メールの文章などでは,印刷物よりは格式度が下がることが多く,ビジネスなど比較的公的な性格の強い文章であっても誤字脱字などは決して少なくない.私的なメール文章であれば,なおさら誤字脱字などが目立つことは,誰しも経験しているところである.さらに,自分しか読むことのない備忘録などでは,文法も乱れており,漢字や句読点も適当に使ったりする.もしそれを人に見られ,書き方が誤っていると指摘されたとしても,私たちはそれは誤りではなく,略式な書き方にすぎないと反論したくなるだろう.書き言葉には,正書法の観点からの正誤とは別の軸として,formality の観点からの格式・略式という軸がある.これは現代英語でも同じである.

英語において綴字の標準化と固定化が着々と進行していた17--18世紀にも,状況は同じだった.綴字には,正誤とは別の軸として formality の軸が存在していた.Addison, Dryden, Swift, Johnson など当時の文人は,1つの固定した正しい綴字で英語を書くことを主張し,正書法の規範を確立しようとしたが,それはあくまで公的な文章を書く場合に限定されていた.というのは,彼らも私信などでは,揺れた綴字を頻繁に用いていたからである.Swift は他人の手紙における綴字には厳しかったにもかかわらず,自らも jail/gaol, hear/here/heer, college/colledge などと揺れていたし,Johnson は自ら書いた辞書でこそ綴字の固定化にこだわったが,私的な書き物では complete/compleet, pamphlet/pamflet, dos/do's/does と変異を示した.Johnson ですら,私信においては特に厳しく正書法を守る必要を感じていなかったのである.Horobin (157) は,17--18世紀におけるこの状況について,以下のように述べている.

Rather being a marker of literacy or education, non-standard spellings in private letters seem to have been considered a marker of relative formality. These private spellings do not appear in printed works, which follow the accepted standard spelling conventions.

この状況は,多かれ少なかれ19世紀以降,現在まで続いているといっても過言ではない.書き言葉については,正書法の問題と formality の問題,あるいは公私の問題とを混同してはならないということだろう.

公私ということでいえば,コンピュータ上でものを書くことが多くなってきた昨今,私的なメモを書いているときですら,半ば自動的にスペルチェッカー,漢字変換,文書校正などのチェック機能が作動するようになってきた.かつては植字工や出版・印刷業者が請けおってきた公的なチェック機能が,現在,コンピュータによって私的な書き物の領域にも侵入してきているといえるだろう.正書法を絶対視する規範主義的な立場の人にとっては,このような自動チェック機能の存在は望ましくすら思われるのかもしれないが,正書法の権化ともいえるかの Swift や Johnson ですら,現代のこの規範の押しつけには辟易するのではないだろうか.「正しさ」が是非とも必要になるのは公的な文脈においてであり,私的な文脈でいちいち「正しさ」を説教されるのは息苦しく感じる.半自動で作動するスペルチェッカーや漢字変換の背後に控えている辞書が一体何なのか,規範の正体が半ばブラックボックスとなっている状況で,常に「正しさ」を強要されているということは,考えてみると息苦しいばかりか,危うさすら感じさせる.Swift と Johnson の見せた公私の区別は,案外,常識的な線をいっていたのかもしれない.

書き言葉への植字工の介入という話題については,「#1844. ドイツ語式の名詞語頭の大文字使用は英語にもあった (2)」 ([2014-05-15-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2014-10-01 Wed

■ #1983. -ick or -ic (3) [suffix][corpus][spelling][emode][eebo][johnson]

昨日の記事「#1982. -ick or -ic (2)」 ([2014-09-30-1]) に引き続き,初期近代英語での -ic(k) 語の異綴りの分布(推移)を調査する.使用するコーパスは市販のものではなく,個人的に EEBO (Early English Books Online) からダウンロードして蓄積した巨大テキスト集である.まだコーパス風に整備しておらず,代表性も均衡も保たれていない単なるテキストの集合という体なので,調査結果は仮のものとして解釈しておきたい.時代区分は16世紀と17世紀に大雑把に分け,それぞれコーパスサイズは923,115語,9,637,954語である(コーパスサイズに10倍以上の開きがある不均衡な実態に注意).以下では,100万語当たりの頻度 (wpm) で示してある.

| Spelling pair | Period 1 (1501--1600) (in wpm) | Period 2 (1601--1700) (in wpm) |

|---|---|---|

| angelick / angelic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.45 / 0.21 |

| antick / antic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 2.49 / 0.10 |

| apoplectick / apoplectic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| aquatick / aquatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.00 |

| arabick / arabic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.52 / 0.10 |

| archbishoprick / archbishopric | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.00 |

| arctick / arctic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.42 / 0.00 |

| arithmetick / arithmetic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 3.22 / 0.31 |

| aromatick / aromatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.83 / 0.10 |

| asiatick / asiatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.31 / 0.00 |

| attick / attic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.31 / 0.21 |

| authentick / authentic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 3.94 / 0.42 |

| balsamick / balsamic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.73 / 0.10 |

| baltick / baltic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.93 / 0.00 |

| bishoprick / bishopric | 1.08 / 0.00 | 4.25 / 0.00 |

| bombastick / bombastic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.00 |

| catholick / catholic | 5.42 / 0.00 | 38.39 / 1.97 |

| caustick / caustic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| characteristick / characteristic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.10 |

| cholick / cholic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.93 / 0.00 |

| comick / comic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 1.45 / 0.10 |

| critick / critic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.76 / 1.87 |

| despotick / despotic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.62 / 0.21 |

| domestick / domestic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 8.09 / 0.21 |

| dominick / dominic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 0.62 / 0.42 |

| dramatick / dramatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.83 / 0.10 |

| emetick / emetic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.31 / 0.00 |

| epick / epic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.10 |

| ethick / ethic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.00 / 0.10 |

| exotick / exotic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.73 / 0.10 |

| fabrick / fabric | 0.00 / 0.00 | 8.72 / 0.31 |

| fantastick / fantastic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 3.42 / 0.10 |

| frantick / frantic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 3.94 / 0.00 |

| frolick / frolic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 3.32 / 0.00 |

| gallick / gallic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 3.32 / 0.52 |

| garlick / garlic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 2.28 / 0.00 |

| heretick / heretic | 2.17 / 0.00 | 6.02 / 0.00 |

| heroick / heroic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 16.91 / 1.35 |

| hieroglyphick / hieroglyphic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.31 / 0.00 |

| lethargick / lethargic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.52 / 0.10 |

| logick / logic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 7.06 / 1.04 |

| lunatick / lunatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.66 / 0.00 |

| lyrick / lyric | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.42 / 0.10 |

| magick / magic | 2.17 / 0.00 | 3.32 / 0.10 |

| majestick / majestic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 4.88 / 0.42 |

| mechanick / mechanic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 4.15 / 0.00 |

| metallick / metallic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| metaphysick / metaphysic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.21 |

| mimick / mimic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.42 / 0.00 |

| musick / music | 7.58 / 627.22 | 40.98 / 251.40 |

| mystick / mystic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.45 / 0.10 |

| panegyrick / panegyric | 0.00 / 0.00 | 4.46 / 0.10 |

| panick / panic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.35 / 0.10 |

| paralytick / paralytic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.00 |

| pedantick / pedantic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.93 / 0.00 |

| philosophick / philosophic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.00 / 0.21 |

| physick / physic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 27.39 / 1.56 |

| plastick / plastic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| platonick / platonic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.93 / 0.00 |

| politick / politic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 15.98 / 1.14 |

| prognostick / prognostic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.52 / 0.00 |

| publick / public | 5.42 / 3.25 | 237.39 / 5.71 |

| relick / relic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.52 / 0.00 |

| republick / republic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 3.01 / 0.31 |

| rhetorick / rhetoric | 0.00 / 0.00 | 5.71 / 0.21 |

| rheumatick / rheumatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| romantick / romantic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.83 / 0.00 |

| rustick / rustic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.66 / 0.00 |

| sceptick / sceptic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.10 |

| scholastick / scholastic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.31 / 0.42 |

| stoick / stoic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.93 / 0.00 |

| sympathetick / sympathetic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| topick / topic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.45 / 0.00 |

| traffick / traffic | 3.25 / 0.00 | 8.61 / 0.42 |

| tragick / tragic | 3.25 / 0.00 | 2.91 / 0.00 |

| tropick / tropic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.04 / 0.00 |

全体として眺めると,初期近代英語では -ick のほうが -ic よりも優勢である.-ic が例外的に優勢なのは,16世紀からの music と,17世紀の critic, scholastic くらいである.昨日の結果と合わせて推測すると,1700年以降,おそらく18世紀前半の間に,-ick から -ic への形勢の逆転が比較的急速に進行していたのではないか.個々の語において逆転のスピードは多少異なるようだが,一般的な傾向はつかむことができた.18世紀半ばに -ick を選んだ Johnson は,やはり保守的だったようだ.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2014-09-30 Tue

■ #1982. -ick or -ic (2) [suffix][johnson][webster][corpus][spelling][clmet][lmode]

「#872. -ick or -ic」 ([2011-09-16-1]) の記事で,<public> と <publick> の綴字の分布の通時的変化について,Google Books Ngram Viewer と Google Books: American English を用いて簡易調査した.-ic と -ick の歴史上の変異については,Johnson の A Dictionary of the English Language (1755) では前者が好まれていたが,Webster の The American Dictionary of the English Language (1828) では後者へと舵を切っていたと一般論を述べた.しかし,この一般論は少々訂正が必要のようだ.

「#1637. CLMET3.0 で between と betwixt の分布を調査」 ([2013-10-20-1]) で紹介した CLMET3.0 を用いて,後期近代英語の主たる -ic(k) 語の綴字を調査してみた.1710--1920年の期間を3期に分けて,それぞれの綴字で頻度をとっただけだが,結果を以下に掲げよう.

| Spelling pair | Period 1 (1710--1780) | Period 2 (1780--1850) | Period 3 (1850--1920) |

|---|---|---|---|

| angelick / angelic | 6 / 50 | 0 / 68 | 0 / 50 |

| antick / antic | 4 / 10 | 1 / 6 | 0 / 3 |

| apoplectick / apoplectic | 0 / 10 | 1 / 19 | 0 / 14 |

| aquatick / aquatic | 1 / 2 | 0 / 35 | 0 / 56 |

| arabick / arabic | 2 / 101 | 0 / 45 | 0 / 115 |

| archbishoprick / archbishopric | 4 / 7 | 2 / 2 | 0 / 8 |

| arctick / arctic | 1 / 5 | 0 / 20 | 0 / 93 |

| arithmetick / arithmetic | 9 / 32 | 0 / 77 | 0 / 98 |

| aromatick / aromatic | 4 / 14 | 0 / 29 | 0 / 36 |

| asiatick / asiatic | 1 / 101 | 0 / 48 | 0 / 76 |

| attick / attic | 1 / 32 | 0 / 34 | 0 / 71 |

| authentick / authentic | 4 / 160 | 0 / 79 | 0 / 68 |

| balsamick / balsamic | 1 / 1 | 0 / 5 | 0 / 1 |

| baltick / baltic | 4 / 50 | 0 / 33 | 0 / 43 |

| bishoprick / bishopric | 3 / 28 | 2 / 9 | 0 / 19 |

| bombastick / bombastic | 1 / 2 | 0 / 3 | 0 / 4 |

| cathartick / cathartic | 0 / 1 | 1 / 0 | 0 / 0 |

| catholick / catholic | 7 / 291 | 0 / 342 | 0 / 296 |

| caustick / caustic | 1 / 2 | 0 / 11 | 0 / 20 |

| characteristick / characteristic | 8 / 92 | 0 / 354 | 0 / 687 |

| cholick / cholic | 1 / 13 | 0 / 2 | 0 / 1 |

| comick / comic | 1 / 68 | 0 / 67 | 0 / 165 |

| coptick / coptic | 1 / 11 | 0 / 3 | 0 / 35 |

| critick / critic | 12 / 153 | 0 / 168 | 0 / 155 |

| despotick / despotic | 9 / 66 | 0 / 51 | 0 / 65 |

| dialectick / dialectic | 1 / 0 | 0 / 0 | 0 / 6 |

| didactick / didactic | 0 / 10 | 1 / 20 | 0 / 23 |

| domestick / domestic | 46 / 733 | 0 / 736 | 0 / 488 |

| dominick / dominic | 4 / 11 | 0 / 14 | 1 / 3 |

| dramatick / dramatic | 8 / 214 | 0 / 206 | 0 / 216 |

| elliptick / elliptic | 1 / 1 | 0 / 8 | 0 / 2 |

| emetick / emetic | 4 / 5 | 0 / 7 | 0 / 5 |

| epick / epic | 1 / 68 | 0 / 83 | 1 / 38 |

| ethick / ethic | 1 / 6 | 0 / 0 | 0 / 3 |

| exotick / exotic | 2 / 7 | 0 / 20 | 0 / 38 |

| fabrick / fabric | 15 / 116 | 1 / 84 | 0 / 111 |

| fantastick / fantastic | 9 / 45 | 0 / 157 | 0 / 198 |

| frantick / frantic | 5 / 88 | 2 / 163 | 0 / 124 |

| frolick / frolic | 19 / 44 | 0 / 46 | 0 / 32 |

| gaelick / gaelic | 1 / 1 | 0 / 30 | 0 / 64 |

| gallick / gallic | 1 / 75 | 0 / 11 | 0 / 10 |

| gothick / gothic | 2 / 498 | 0 / 131 | 0 / 66 |

| heretick / heretic | 2 / 31 | 0 / 37 | 0 / 24 |

| heroick / heroic | 17 / 201 | 2 / 224 | 0 / 211 |

| hieroglyphick / hieroglyphic | 2 / 4 | 0 / 7 | 0 / 8 |

| hysterick / hysteric | 1 / 9 | 0 / 10 | 0 / 6 |

| laconick / laconic | 2 / 13 | 0 / 14 | 0 / 7 |

| lethargick / lethargic | 1 / 12 | 0 / 8 | 0 / 14 |

| logick / logic | 4 / 62 | 0 / 361 | 0 / 367 |

| lunatick / lunatic | 2 / 32 | 0 / 34 | 0 / 77 |

| lyrick / lyric | 3 / 15 | 0 / 26 | 0 / 37 |

| magick / magic | 9 / 110 | 0 / 296 | 0 / 292 |

| majestick / majestic | 4 / 73 | 0 / 149 | 1 / 115 |

| mechanick / mechanic | 6 / 79 | 0 / 47 | 0 / 58 |

| metallick / metallic | 1 / 9 | 0 / 79 | 0 / 137 |

| metaphysick / metaphysic | 1 / 2 | 0 / 11 | 0 / 9 |

| mimick / mimic | 2 / 25 | 1 / 46 | 0 / 23 |

| musick / music | 87 / 549 | 3 / 1220 | 3 / 1684 |

| mystick / mystic | 1 / 39 | 0 / 92 | 0 / 167 |

| obstetrick / obstetric | 1 / 2 | 0 / 1 | 0 / 0 |

| panegyrick / panegyric | 19 / 121 | 0 / 43 | 0 / 16 |

| panick / panic | 14 / 58 | 1 / 90 | 0 / 314 |

| paralytick / paralytic | 1 / 15 | 0 / 41 | 0 / 14 |

| pedantick / pedantic | 3 / 31 | 0 / 28 | 0 / 29 |

| philippick / philippic | 2 / 2 | 0 / 3 | 0 / 2 |

| philosophick / philosophic | 1 / 140 | 0 / 80 | 0 / 155 |

| physick / physic | 35 / 157 | 4 / 51 | 3 / 38 |

| plastick / plastic | 1 / 4 | 0 / 19 | 0 / 32 |

| platonick / platonic | 5 / 48 | 0 / 30 | 0 / 22 |

| politick / politic | 8 / 40 | 2 / 37 | 0 / 51 |

| prognostick / prognostic | 2 / 18 | 0 / 5 | 0 / 1 |

| publick / public | 767 / 3350 | 1 / 3171 | 2 / 2606 |

| relick / relic | 1 / 26 | 4 / 56 | 0 / 65 |

| republick / republic | 12 / 515 | 0 / 185 | 0 / 171 |

| rhetorick / rhetoric | 26 / 109 | 2 / 40 | 0 / 65 |

| rheumatick / rheumatic | 1 / 7 | 0 / 33 | 0 / 30 |

| romantick / romantic | 32 / 191 | 0 / 346 | 0 / 322 |

| rustick / rustic | 3 / 102 | 0 / 157 | 0 / 80 |

| sarcastick / sarcastic | 1 / 37 | 0 / 66 | 0 / 60 |

| sceptick / sceptic | 3 / 26 | 0 / 19 | 0 / 26 |

| scholastick / scholastic | 2 / 24 | 0 / 42 | 0 / 46 |

| sciatick / sciatic | 1 / 1 | 0 / 1 | 0 / 3 |

| scientifick / scientific | 2 / 16 | 0 / 451 | 0 / 814 |

| stoick / stoic | 5 / 34 | 1 / 15 | 0 / 26 |

| sympathetick / sympathetic | 3 / 26 | 0 / 70 | 0 / 248 |

| systematick / systematic | 1 / 13 | 0 / 64 | 0 / 104 |

| topick / topic | 12 / 128 | 0 / 177 | 0 / 176 |

| traffick / traffic | 80 / 67 | 1 / 164 | 0 / 203 |

| tragick / tragic | 4 / 65 | 0 / 65 | 0 / 209 |

| tropick / tropic | 12 / 37 | 0 / 7 | 0 / 23 |

第2期以降 (1780--1920) は,すべての語において事実上 -ic のみとなったとみてよいが,18世紀の大半を含む第1期 (1710--1780) については,ここかしこに保守的な -ick が散見される.語によっては <critick>, <frolick>, <heroick>, <musick>, <panegyrick>, <panick>, <physick>, <publick>, <rhetorick>, <romantick>, <tropick> など そこそこの頻度を示すものもあるし,<traffick> ではむしろ -ic 形よりも優勢だ(なお,屈折語尾としての -ic(k) ではないが,garlick/garlic は,第1期 17 / 7, 第2期 1 / 8, 第3期 0 / 11 を数え,最初期に -ick が優勢だったもう1つの例である).しかし,全体として -ick 形は散見されるにすぎず,すでに18世紀より -ic 形が幅を利かせていたことがわかる.つまり,18世紀半ばの Johnson の辞書では,すでに影の薄くなっていた保守的な -ic が,半ば意識的に採用されたという解釈が成り立ちそうだ.Webster の時代ではなく,Johnson の時代にすでに -ic 形は事実上の市民権を得ていたと考えられる.

しかし,CLMET で得られた後期近代英語の趨勢を歴史の中に適切に位置づけて解釈するためには,先行する初期近代英語における異綴字の分布(変化)も押えておく必要があるだろう.それについては明日の記事で.

2014-02-10 Mon

■ #1750. bonfire [etymology][semantic_change][phonetics][folk_etymology][johnson][history][trish]

昨日の記事「#1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード」 ([2014-02-09-1]) で,Aitchison の "language bonfire" の仮説を紹介したが,この bonfire (焚き火)という語の語誌が興味深いので触れておきたい.意味と形態の両方において,変化を遂げてきた語である.

この語の初出は15世紀に遡り,bonnefyre, banefyre などの綴字で現れる.語源としては比較的単純で,bone + fire の複合語である.文字通り骨を集めて野外で火を焚く,おそらくキリスト教以前に遡る行事を指していたようで,「宗教的祭事・祝典・合図などのため野天で焚く大かがり火」を意味した. 黒死病の犠牲者の骨を山のように積んで燃やす火のことでもあり,火あぶりの刑や焚書に用いる火のことでもあった.Onians (268fn) によると,骨は生命の種と考えられており,それを燃やすことで豊饒,多産,幸運が得られると信じられていたともいう.ラテン語 ignis ossium,フランス語 feu d'os などの対応語句がある.初期の例は,MED bōn-fīr を参照.

16世紀からは第1音節がつづまった bonfire の綴字が普及するにつれて bone の原義が忘れられるようになり,一般化した語義「焚き火」「ゴミ焚き」が現れてくる.ただし,スコットランドでは,OED bonfire, n. の語源欄にあるように,元来の綴字と原義が1800年頃まで保たれていたようだ ("In Scotland with the form bane-fire, the memory of the original sense was retained longer; for the annual midsummer 'banefire' or 'bonfire' in the burgh of Hawick, old bones were regularly collected and stored up, down to c1800.") .ほかにも近代の方言形では長母音を示す綴字が残っている (see "bonefire" in EDD Online) .

第1要素の bon が何を表すのか不明になってくると,民間語源風の解釈が行われるようになり,1755年には Johnson の辞書ですら次のような解釈を示した.

BO'NFIRE. n. s. [from bon, good, Fr. and fire.] A fire made for some publick cause of triumph or exultation.

だが,複合語の第1要素がこのように短縮するのは珍しいことではない.もともとの長母音が,複合により語全体が長くなることへの代償として,短母音化するという音韻過程は,gospell (< God + spell), holiday (< holy + day), knowledge (< know + -ledge), Monday (< moon + day) などで普通に見られる.

bonfire といえば,イギリスでは11月5日に行われる民間行事 Bonfire Night あるいは Guy Fawkes Night が有名である.1605年11月5日,カトリック教徒が議会爆破と James I 暗殺をもくろんだ火薬陰謀事件 (Gunpowder Plot) が実行される予定だったが,計画が前日に露見し,実行者とされる Guy Fawkes (1570--1606) が逮捕された.以来,陰謀の露見と国王の無事を祝うべく,街頭で大きなかがり火を燃やし,Guy Fawkes をかたどった人形を燃やし,花火をあげる習俗が行われてきた.

・ Onians, Richard Broxton. The Origins of European Thought about the Body, the Mind, the Soul, the World, Time, and Fate. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 1954.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow