2018-01-05 Fri

■ #3175. group thinking と tree thinking [history_of_linguistics][family_tree][methodology][metaphor][metonymy][diachrony][causation][language_change][comparative_linguistics][linguistic_area][contact][borrowing][variation][terminology][how_and_why][abduction]

「#3162. 古因学」 ([2017-12-23-1]) や「#3172. シュライヒャーの系統図的発想はダーウィンからではなく比較文献学から」 ([2018-01-02-1]) で参照してきた三中によれば,人間の行なう物事の分類法は「分類思考」 (group thinking) と「系統樹思考」 (tree thinking) に大別されるという.横軸の類似性をもとに分類するやり方と縦軸の系統関係をもとに分類するものだ.三中 (107) はそれぞれに基づく科学を「分類科学」と「古因科学」と呼び,両者を次のように比較対照している.

| 分類科学 | 分類思考 | メタファー | 集合/要素 | 認知カテゴリー化 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 古因科学 | 系統樹思考 | メトニミー | 全体/部分 | 比較法(アブダクション) |

上の表の最後に触れられているアブダクションについては「#784. 歴史言語学は abductive discipline」 ([2011-06-20-1]) を参照.

三中は生物分類学の専門家だが,その分野では,たとえモデル化された図像が同じようなツリーだったとしても,観念論的に解釈された場合と系統学的に解釈された場合とではメッセージが異なりうるという.前者が分類思考に,後者が系統樹思考に対応すると思われるが,これについても上記と似たような比較対照表「観念論的な体系学とその系統学的解釈の対応関係」が著書の p. 172 に挙げられているので示そう(ただし,この表のもとになっているのは別の研究者のもの).

| 観念論的解釈 | 系統学的解釈 | |

|---|---|---|

| 体系学 (Systematik) | ← | 系統学 (Phylogenetik) |

| 形態類縁性 (Formverwandtschaft) | ← | 血縁関係 (Blutsverwandtschaft) |

| 変容 (Metamorphose) | ← | 系統発生 (Stammesentwicklung) |

| 体系学的段階系列 (systematischen Stufenreihen) | ← | 祖先系列 (Ahnenreihen) |

| 型 (Typus) | ← | 幹形 (Stammform) |

| 型状態 (typischen Zuständen) | ← | 原始的状態 (ursprüngliche Zuständen) |

| 非型的状態 (atypischen Zuständen) | ← | 派生的状態 (abgeänderte Zuständen) |

このような group thinking と tree thinking の対照関係を言語学にも当てはめてみれば,多くの対立する用語が並ぶことになるだろう.思いつく限り自由に挙げてみた.

| 分類科学 | 古因科学 |

|---|---|

| 構造主義言語学 (structural linguistics) | 比較言語学 (comparative linguistics) |

| 類型論 (typology) | 歴史言語学 (historical linguistics) |

| 言語圏 (linguistic area) | 語族 (language family) |

| 接触・借用 (contact, borrowing) | 系統 (inheritance) |

| 空間 (space) | 時間 (time) |

| 共時態 (synchrony) | 通時態 (diachrony) |

| 範列関係 (paradigm) | 連辞関係 (syntagm) |

| パターン (pattern) | プロセス (process) |

| 紊???? (variation) | 紊???? (change) |

| タイプ (type) | トークン (token) |

| メタファー (metaphor) | メトニミー (metonymy) |

| How | Why |

最後に挙げた How と Why の対立については,三中 (238) が生物学に即して以下のように述べているところからのインスピレーションである.

進化思考をあえて看板として高く掲げるためには,私たちは分類思考に対抗する力をもつもう一つの思考枠としてアピールする必要がある.たとえば,目の前にいる生きものたちが「どのように」生きているのか(至近要因)に関する疑問は実際の生命プロセスを解明する分子生物学や生理学の問題とみなされる.これに対して,それらの生きものが「なぜ」そのような生き方をするにいたったのか(究極要因)に関する疑問は進化生物学が取り組むべき問題だろう.

言語変化の「どのように」と「なぜ」の問題 (how_and_why) については,「#2123. 言語変化の切り口」 ([2015-02-18-1]),「#2255. 言語変化の原因を追究する価値について」 ([2015-06-30-1]),「#2642. 言語変化の種類と仕組みの峻別」 ([2016-07-21-1]),「#3133. 言語変化の "how" と "why"」 ([2017-11-24-1]) で扱ってきたが,生物学からの知見により新たな発想が得られた感がある.

・ 三中 信宏 『進化思考の世界 ヒトは森羅万象をどう体系化するか』 NHK出版,2010年.

2017-12-14 Thu

■ #3153. 英語史における基本色彩語の発展 [bct][semantic_change][lexicology][terminology]

「#2103. Basic Color Terms」 ([2015-01-29-1]) で取り上げたように,言語における色彩語の発展には,およそ普遍的といえる道筋があると考えられている.英語の色彩語も,歴史を通じてその道筋をたどったことが確認されている.まず,この問題を論じる上で基本的な用語である basic colour terms (BCTs) と basic colour categories (BCCs) の定義を確認しておこう.Christian and Allan の巻末の用語集より引用する (178) .

basic colour categories (BCCs) are the principal divisions of the colour space which underlie the basic colour terms (BCTs) of a particular speech community. A BCC is an abstract concept which operates independently of things described by terms such as green or yellow. BCCs are presented in small capital letters, for example GREEN.

basic colour terms (BCTs) are the words which languages use to name basic colour categories. A BCT, such as green or yellow, is known to all members of a speech community and is used in a wide range of contexts. Other colour words in a language are called non-basic terms, for example sapphire, scarlet or auburn.

Biggam の要約によると,英語の BCCs の発達は以下の通りである.

OE: (1) WHITE/BRIGHT, (2) BLACK/DARK, (3) RED+ (4) YELLOW, (5) GREEN, (6) GREY

ME: (1) WHITE, (2) BLACK, (3) RED+, (4) YELLOW, (5) GREEN, (6) GREY, (7) BLUE, (8) BROWN

ModE: (1) WHITE, (2) BLACK, (3) RED, (4) YELLOW, (5) GREEN, (6) GREY, (7) BLUE, (8) BROWN, (9) PURPLE, (10) ORANGE, (11) PINK

一方,BCTs の発達は以下の通り.

OE: hwit, blæc/(sweart), read, geolu, grene, græg

ME: whit, blak, red yelwe, grene, grei, bleu, broun

ModE: white, black, red, yellow, green, grey, blue, brown, purple, orange, pink

BCTs の種類は,古英語の6から中英語の8を経由して,近代英語の11へと増えてきたことになる.その経路は,[2015-01-29-1]の図で示した「普遍的な」経路とほぼ重なっている.

・ Kay, Christian and Kathryn Allan. English Historical Semantics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015.

・ Biggam, C. P. "English Colour Terms: A Case Study." Chapter 7 of English Historical Semantics. Christian Kay and Kathryn Allan. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015. 113--31.

2017-12-08 Fri

■ #3147. 言語における「遺伝的関係」とは何か? (2) [terminology][comparative_linguistics][family_tree][methodology][linguistics][wave_theory][creole][contact][sobokunagimon]

昨日の記事 ([2017-12-07-1]) に引き続いての話題.言語間の「遺伝的関係」を語るとき,そこにはいかなる前提が隠されているのだろうか.

その前提は実は論者によって様々であり,すべての言語学者が同意している前提というものはない.しかし,Noonan (50) は「遺伝的関係」が語られる前提として,大きく3種類の態度が区別されるとしている.

(1) the generational transmission approach.大多数の言語学者が受け入れている,理解しやすい前提であり,それゆえに明示的に指摘されることが最も少ない考え方でもある.この立場にあっては,言語間の遺伝的関係とは,言語的伝統が代々受け継がれてきた歴史と同義である.親が習得したのとほぼ同じ言語体系を子供が習得し,それを次の世代の子供が習得するというサイクルが代々繰り返されることによって,同一の言語が継承されていくという考え方だ.このサイクルに断絶がない限り,時とともに多かれ少なかれ変化が生じたとしても,遺伝的には同一の言語が受け継がれているとみなすのが常識的である.現代英語の話者は,世代を遡っていけば断絶なく古英語の話者へ遡ることができるし,比較言語学の力を借りてではあるが,ゲルマン祖語の話者,そして印欧祖語の話者へも遡ることができる(と少なくとも議論はできる).したがって,現代英語と印欧祖語には,連綿と保持されてきた遺伝的関係があるといえる.

(2) the essentialist approach.話者の連続的な世代交代ではなく,言語項の継承に焦点を当てる立場である.直接的に遺伝関係のある言語間では,ある種の文法的な形態素や形態統語的特徴が引き継がれるはずであるという前提に立つ.逆にいえば,そのような言語特徴が,母言語と目される言語から娘言語と目される言語へと引き継がれていれば,それは正真正銘「母娘」の関係にある,つまり遺伝的関係にあるとみなすことができる,とする.(1) と (2) の立場は,しばしば同じ分析結果を示し,ともに比較言語学の方法と調和するという共通点もあるが,前提の拠って立つ点が,(1) では話者による言語伝統の継承,(2) ではある種の言語項の継承であるという違いに注意する必要がある.

(3) the hybrid approach.(1), (2) 以外の様々な考え方を様々な方法で取り入れた立場で,ここでは便宜的に "the hybrid approach" として1つのラベルの下にまとめている.波状理論,現代の比較言語学,クレオール論などがここに含まれる.これらの論の共通点は,少なくともいくつかの状況においては,複数の言語が混合し得るのを認めていることである(上記 (1), (2) の立場は言語の遺伝的混合という概念を認めず,たとえ "mixed language" の存在を認めるにせよ,それを「遺伝関係」の外に置く方針をとる).比較言語学の方法を排除するわけではないが,その方法がすべての事例に適用されるとは考えていない.また,言語は言語項の集合体であるとの見方を取っている.この立場の内部でも様々なニュアンスの違いがあり,まったく一枚岩ではない.

このように歴史言語学の言説で日常的に用いられる「遺伝的関係」の背後には,実は多くの論点を含んだイデオロギーの対立が隠されているのである.関連して,「#1578. 言語は何に喩えられてきたか」 ([2013-08-22-1]) を参照.混成語の例については,「#1717. dual-source の混成語」 ([2014-01-08-1]) を参照.

・ Noonan, Michael. "Genetic Classification and Language Contact." The Handbook of Language Contact. Ed. Raymond Hickey. 2010. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. 48--65.

2017-12-07 Thu

■ #3146. 言語における「遺伝的関係」とは何か? (1) [terminology][comparative_linguistics][family_tree][methodology][typology][borrowing][linguistics][sobokunagimon]

歴史言語学において,共通祖語をもつ言語間の発生・発達関係は "genetic relationship" と呼ばれる.本来生物学に属する "genetics" という用語を言語に転用することは広く行なわれ,当然のものとして受け入れられてきた.しかし,真剣に考え出すと,それが何を意味するかは,まったく自明ではない.この用語遣いの背景には様々な前提が隠されており,しかもその前提は論者によって著しく異なっている.この問題について,Noonan (48--49) が比較的詳しく論じているので,参照してみた.今回の記事では,言語における遺伝的関係とは何かというよりも,何ではないかということを明らかにしたい.

まず力説すべきは,言語の遺伝的関係とは,その話者集団の生物学的な遺伝的関係とは無縁ということである.現代の主流派言語学では,人種などの遺伝学的,生物学的な分類と言語の分類とは無関係であることが前提とされている.個人は,どの人種のもとに生まれたとしても,いかなる言語をも習得することができる.個人の習得する言語は,その遺伝的特徴により決定されるわけではなく,あくまで生育した社会の言語環境により決定される.したがって,言語の遺伝的関係の議論に,話者の生物学的な遺伝の話題が入り込む余地はない.

また,言語類型論 (linguistic typology) は,言語間における言語項の類似点・相違点を探り,何らかの関係を見出そうとする分野ではあるが,それはあくまで共時的な関係の追求であり,遺伝的関係について何かを述べようとしているわけではない.ある2言語のあいだの遺伝的関係が深ければ,言語が構造的に類似しているという可能性は確かにあるが,そうでないケースも多々ある.逆に,構造的に類似している2つの言語が,異なる系統に属するということはいくらでもあり得る.そもそも言語項の借用 (borrowing) は,いかなる言語間にあっても可能であり,借用を通じて共時的見栄えが類似しているにすぎないという例は,古今東西,数多く見つけることができる.

では,言語における遺伝的関係とは,話者集団の生物学的な遺伝的関係のことではなく,言語類型論が指摘するような共時的類似性に基づく関係のことでもないとすれば,いったい何のことを指すのだろうか.この問いは,歴史言語学においてもほとんど明示的に問われたことがないのではないか.それにもかかわらず日常的にこの用語が使われ続けてきたのだとすれば,何かが暗黙のうちに前提とされてきたことになる.英語は遺伝的にはゲルマン語派に属するとか,日本語には遺伝的関係のある仲間言語がないなどと言うとき,そこにはいかなる言語学上の前提が含まれているのか.これについて,明日の記事で考えたい.

・ Noonan, Michael. "Genetic Classification and Language Contact." The Handbook of Language Contact. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. 2013. 48--65.

2017-10-20 Fri

■ #3098. 綴字と発音の交渉 [phonetics][pronunciation][spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][terminology]

equation は <-tion> の綴字をもつにもかかわらず,/-ʃən/ よりも /-ʒən/ で発音されることのほうが多い.この問題については,「#1634. 「エキシビジョン」と equation」 ([2013-10-17-1]),「#1635. -sion と -tion」 ([2013-10-18-1]) で取りあげた.ほかに「#2519. transition の発音」 ([2016-03-20-1]) でも,問題の歯茎硬口蓋摩擦音が有声で発音されることに言及した.また,大名氏のツイートによれば,<-tion> の事例ではないが,coercion でもアメリカ発音で /ʃ/ と並んで /ʒ/ が聞かれ,Kashmir(i) でも同様だという.現代英語の標準綴字体系としては,<-tion>, <-cion>, <sh> の綴字中の歯茎硬口蓋摩擦音は無声というのが規則だが,このような稀な例外も見出されるのである(Carney (242) は equation について "A very curious correspondence of /ʒ/≡<ti> occurs for many speakers in equation. Among the large number of words ending in <-ation>, this appears to be a single exception." と述べている).

equation, transition, coercion の例を考えてみると,なぜこのようなことが起こりうるかという背景については言えることがありそうだ.「#2519. transition の発音」 ([2016-03-20-1]) で述べたように,「/-ʃən/ と /-ʒən/ の揺れは <-sion> や <-sian> ではよく見られるので,それが類推的に <-tion> にも拡大したものと考えられる」ということだ.これを別の角度からみると,(1) 綴字と発音の対応関係,および (2) 発音どうし,あるいは綴字どうしの類推関係の2種類の関係が,順次発展していったものととらえることができる.もっと凝縮した表現として,綴字と発音の「交渉」 (negotiation) という呼称を提案したい.

以下の図を参照して「交渉」の進展する様を見てみよう.

| --- 第1段階 --- | --- 第2段階 --- | --- 第3段階 --- | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [ 綴字の世界 ] | [ 発音の世界 ] | [ 綴字の世界 ] | [ 発音の世界 ] | [ 綴字の世界 ] | [ 発音の世界 ] | |||||

| <-sion>, <-sian> | = | /-ʃən/ or /-ʒən/ | <-sion>, <-sian> | = | /-ʃən/ or /-ʒən/ | <-sion>, <-sian> | = | /-ʃən/ or /-ʒən/ | ||

| || | || | |||||||||

| <-tion>, <-cion> | = | /-ʃən/ | <-tion>, <-cion> | = | /-ʃən/ | <-tion>, <-cion> | = | /-ʃən/ or /-ʒən/ | ||

| --- 第4段階 --- | --- 第5段階 --- | --- 第6段階 --- | ||||||||

| [ 綴字の世界 ] | [ 発音の世界 ] | [ 綴字の世界 ] | [ 発音の世界 ] | [ 綴字の世界 ] | [ 発音の世界 ] | |||||

| <-sion>, <-sian> | = | /-ʃən/ or /-ʒən/ | <-sion>, <-sian> | = | /-ʃən/ or /-ʒən/ | <-sion>, <-sian>, <-tion>, <-cion> | = | /-ʃən/ or /-ʒən/ | ||

| || | ||||||||||

| <-tion>, <-cion> | = | <-tion>, <-cion> | = | |||||||

まず,第1段階では,独立した2つの綴字と発音の対応関係が存在している.これは,図には描かれていないが,先立つ第0段階の交渉作用を通じて,現在までに「対応規則」として確立してきた盤石な綴字と発音の関係を表わしている.

第2段階では,上下2つの対応関係が,発音の世界においてともに /-ʃən/ を含んでいることが引き金となり,上が下へ交渉を働きかける.つまり,上の /-ʃən/ or /-ʒən/ が,下の /-ʃən/ に働きかけて,自分と同じように振る舞えと圧力をかける.

その結果,第3段階では,下の発音が上の発音と同様の /-ʃən/ or /-ʒən/ となり,無声・有声のヴァリエーションを許容するようになる.現代標準英語は,この第3段階まで進んでいるようにみえる.ただし,それも equation や transition などのごく少数の単語に及んでいるにすぎず,第3段階の初期段階と考えることができるように思われる.

第4段階では,上下の発音の世界が合一したことが示されている.

第5段階では,発音の世界の上下合一の圧力が,左側の綴字の世界へも及んでいき,新たな交渉を迫る.結果として,綴字の世界においても,<-sion>, <-sian>, <-tion>, <-cion> が無差別に結びつけられるようになる.その連係が完成した際には,最後の第6段階の構図に至るだろう.

以上は,あくまで綴字と発音をめぐる交渉を図式的に説明するためのものであり,そもそも第4段階以降は,将来到達するかもしれない領域についての想像の産物にすぎない.しかも,これは綴字と発音をめぐる複雑な関係の通時的変化のメカニズムを一般的に説明しようとするモデルにすぎず,なぜ equation や transition という特定の単語が,現在第3段階にあって,交渉を受けているのかという個別の問題には何も答えてくれない.

綴字と発音のあいだに複雑な関係が発達するということは,通時的には至極ありふれた現象である.「交渉」という用語・概念や上の段階図も,大仰ではあるが,その卑近な事実を反映したものにすぎない.

なお,この「交渉」と呼んだ現象については,去る6月24日に青山学院大学で開かれた近代英語協会第34回大会でのシンポジウム「英語音変化研究の課題と展望」にて,「英語史における音・書記の相互作用 --- 中英語から近代英語にかけての事例から ---」と題する発表で取りあげた.シノプシスはこちらのPDFからどうぞ.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2017-07-22 Sat

■ #3008. 「借用とは参考にした上での造語である」 [borrowing][neolinguistics][terminology]

先日大学の授業で,言語における借用 borrowing とは何かという問題について,特に借用語 (loan_word) を念頭に置きつつディスカッションしてみた.以前にも同じようなディスカッションをしたことがあり,本ブログでも「#44. 「借用」にみる言語の性質」 ([2009-06-11-1]),「#2010. 借用は言語項の複製か模倣か」 ([2014-10-28-1]) などで論じてきた.今回あらためて受講生の知恵を借りて考えたところ,新しい洞察が得られたので報告したい.

語の借用を考えるとき,そこで起こっていることは厳密にいえば「借りる」過程ではなく,したがって「借用」という表現はふさわしくない,ということはよく知られていた.そこで,以前の記事では「複製」 (copying),「模倣」 (imitation),「再創造」 (re-creation) 等の別の概念を持ち出して,現実と用語のギャップを埋めようとした.今回のディスカッションで学生から飛び出した洞察は,これらを上手く組み合わせた「参考にした上での造語」という見解である.単純に借りるわけでも,コピーするわけでも,模倣するわけでもない.相手言語におけるモデルを参考にした上で,自言語において新たに造語する,という見方だ.これは言語使用者の主体的で積極的な言語活動を重んじる,新言語学派 (neolinguistics) の路線に沿った言語観を表わしている.

主体性や積極性というのは,もちろん程度の問題である.それがゼロに近ければ事実上の「複製」や「模倣」とみなせるだろうし,最大限に発揮されれば「造語」や「創造」と表現すべきだろう.用語や概念は包括的なほうが便利なので「参考にした上での造語」という「借用」の定義は適切だと思うが,説明的で長いのが,若干玉に瑕である.

いずれにせよ非常に有益なディスカッションだった.

2017-06-18 Sun

■ #2974. 2重目的語構文から to 構文へ [synthesis_to_analysis][eme][french][contact][syntax][inflection][case][dative][syncretism][word_order][terminology][ditransitive_verb]

昨日の記事「#2973. 格の貧富の差」 ([2017-06-17-1]) に引き続き,Allen の論考より話題を提供したい.

2重目的語構文が,前置詞 to を用いる構文へ置き換わっていくのは,初期中英語期である.古英語期から後者も見られたが,可能な動詞の種類が限られるなどの特徴があった.初期中英語期になると,頻度が増えてくるばかりか,動詞の制限も取り払われるようになる.タイミングとしては格屈折の衰退の時期と重なり,因果関係を疑いたくなるが,Allen は,関係があるだろうとはしながらも慎重な議論を展開している.特定のテキストにおいては,すでに分析的な構文が定着していたフランス語の影響すらあり得ることも示唆しており,単純な「分析から総合へ」 (synthesis_to_analysis) という説明に対して待ったをかけている.Allen (214) を引用する.

It can be noted . . . that we do not require deflexion as an explanation for the rapid increase in to-datives in ME. The influence of French, in which the marking of the IO by a preposition was already well advanced, appears to be the best way to explain such text-specific facts as the surprisingly high incidence of to-datives in the Aȝenbite of Inwit. . . . [T]he dative/accusative distinction was well preserved in the Aȝenbite, which might lead us to expect that the to-dative would be infrequent because it was not needed to mark Case, but in fact we find that this work has a significantly higher frequency of this construction than do many texts in which the dative/accusative distinction has disappeared in overt morphology. The puzzle is explained, however, when we realize that the Aȝenbite was a rather slavish translation from French and shows some unmistakable signs of the influence of its French exemplar in its syntax. It is, of course, uncertain how important French influence was in the spoken language, but contact with French would surely have encouraged the use of the to-dative. It should also be remembered that an innovation such as the to-dative typically follows an S-curve, starting slowly and then rapidly increasing, so that no sudden change in another part of the grammar is required to explain the sudden increase of the to-dative.

Allen は屈折の衰退という現象を deflexion と表現しているが,私はこの辺りを専門としていながらも,この術語を使ったことがなかった.便利な用語だ.1つ疑問として湧いたのは,引用の最後のところで,to-dative への移行について語彙拡散のS字曲線ということが言及されているが,この観点から具体的に記述された研究はあるのだろうか,ということだ.屈折の衰退と語順の固定化という英語文法史上の大きな問題も,まだまだ掘り下げようがありそうだ.

・ Allen, Cynthia L. "Case Syncretism and Word Order Change." Chapter 9 of The Handbook of the History of English. Ed. Ans van Kemenade and Bettelou Los. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006. 201--23.

2017-05-15 Mon

■ #2940. ideophone [phonaesthesia][sound_symbolism][terminology]

ideophone, ideophonic という言語事象がある.「表意音(の)」と訳されるが,あまり馴染みがなかったので調べてみた.OED によると,2つの語義がある.

Linguistics (a) a term used by A. J. Ellis (in contradistinction to ideograph) for a sound or group of sounds denoting an idea, i.e. a spoken word; (b) an onomatopoeic or sound-symbolic word, especially one belonging to particular classes in Bantu languages.

1つ目は,ideograph (表意文字)に対応するもので,実際的には,音声上の有意味単位である形態素や語のことを指すのだろう.たいてい言語学で用いられるのは2つ目の語義においてであり,こちらは特にアフリカの諸言語にみられる擬音的で有意味な要素を指す.つまり,より知られている用語でいえば,音象徴 (sound_symbolism),音感覚性 (phonaesthesia),オノマトペ (onomatopoeia) といった現象と重なる.

生産的な ideophone の存在は,多くの言語で確認される.例えば,アメリカ原住民によって話される Yuman 語群の Kiliwa 語では,n, l, r の3子音が,意味的な基準で,強度や規模の程度によって,交替するのだという.n が「小」,l が「中」,r が「大」に対応する.例えば,「小さな丸」は tyin,「中丸」は tyil,「大丸」は tyir と言い,「ぬるい」は pan,「熱い」は pal,「極度に熱い」は par を表わすという.

同様に,Lakota (Siouan) 語 では種々の歯擦音の間で交替を示し,「一時的に荒れた表面」が waza で,「永久に荒れた表面」は waž, さらに荒れて「ねじられた,曲がった」は baxa で表わされるという.

上の例では,音列と意味によって構成されるある種の「体系」が感じられ,各子音に何らかの「意味」が伴っていると評価してもよさそうに思われる.しかし,その「意味」は抽象的で,的確には定義しがたい.明確な意味を有さない「音素」よりは有意味だが,明確な意味を有する「形態素」よりは無意味であるという点で,構造言語学の隙を突くような単位とみなすことができるだろう.何とも名付けがたい単位だが,このような単位は,実は古今東西の言語にかなり普遍的に存在するだろうと思っている.

方法論的な課題としては,このような話題が,構造言語学の枠内においては,実に曖昧な単位であるがゆえに扱いにくいということである.これを言語学として,まともに真面目に扱いうる良いアイディアはないものだろうか.

関連して,「#1269. 言語学における音象徴の位置づけ」 ([2012-10-17-1]),「#2222. 言語学における音象徴の位置づけ (2)」 ([2015-05-28-1]),「#2605. 言語学における音象徴の位置づけ (3)」 ([2016-06-14-1]) などの記事を参照.

・ Campbell, Lyle and Mauricio J. Mixco, eds. A Glossary of Historical Linguistics. Salt Lake City: U of Utah P, 2007.

2017-04-22 Sat

■ #2917.「英語の第二公用語化」とは妙な表現 [hispanification][official_language][terminology]

我が国の言語政策の提案として英語の第二公用語化という議論があるが,よく考えるとこの名称はおかしい.日本には,正確な意味での第一公用語はないからだ.鈴木 (23) のことばを引く.

日本人にとっては日本で日本語を使うのはあたりまえのことなのです.したがって法律的にわざわざ日本語を公用語と規定する必要はない.それがないところへもってきて,突然に第二公用語と言い出すのは,軽率というか不勉強だと思います.

公用語というのは,このように日本やアメリカを見てもわかるように,必要に迫られない場合には決めないものなのです.スイスやシンガポールやインドといった,よく例に出る国の場合は,国の中が複数の言語,場合によっては多言語になっている.そこでいくつもある言語を法的に位置づけることが必要になる.たとえば学校教育だとか,政治,公の文書とか,法律や裁判をどの言語で行うか,というふうな問題が出てくるからです.

ここで分かりやすく述べられているように,公用語 (official_language) とは社会的な必要に迫られて,国により法的に定められるものである.日本における日本語,イギリスにおける英語などは「公用語」化する必要が感じられないくらい,社会的な地位が安定している.したがって,「公用語」は日本にもイギリスにも必要がなく,存在しないものである.そこへもってきて,日本で英語を「第二」公用語にすべき,あるいはすべきでないと論じることは,それ自体がおかしな話である.

上の引用にはアメリカの国名も含まれているが,連邦レベルでは英語が公用語とされていないものの,州によっては英語公用語化が進められている.この件については,「#256. 米国の Hispanification」 ([2010-01-08-1]),「#1657. アメリカの英語公用語化運動」 ([2013-11-09-1]),「#2610. ラテンアメリカ系英語変種」 ([2016-06-19-1]) で関連する話題に触れたが,背後にはアメリカ国内で増加するスペイン語話者の存在,hispanification という社会現象がある.最も国際的な言語である英語が,まさにその母語話者数において最大を誇るアメリカという国のなかで,圧力を受けているのである.

「公用語」とは,何らかのプレッシャーの存在を前提とする概念であり用語である.

・ 鈴木 孝夫 『あなたは英語で戦えますか』 冨山房インターナショナル,2011年.

2017-02-28 Tue

■ #2864. 分類学における系統と段階 [family_tree][anthropology][homo_sapiens][diachrony][terminology][linguistic_area][typology][methodology][world_languages][evolution]

世界の言語を分類する際の2つの基準である「系統」と「影響」は,言語どうしの関係の仕方を決定づける基準でもある.この話題については,本ブログでも以下の記事を始めとして,あちらこちらで論じてきた (see 「#369. 言語における系統と影響」 ([2010-05-01-1]),「#807. 言語系統図と生物系統図の類似点と相違点」 ([2011-07-13-1]),「#371. 系統と影響は必ずしも峻別できない」 ([2010-05-03-1]),「#1136. 異なる言語の間で類似した語がある場合」 ([2012-06-06-1]),「#1236. 木と波」 ([2012-09-14-1]),「#1930. 系統と影響を考慮に入れた西インドヨーロッパ語族の関係図」 ([2014-08-09-1])) .

系統と影響は,それぞれ通時態と共時態の関係にも通じるところがある.系統とは時間軸に沿った歴史の縦軸を指し,影響とは主に地理的な隣接関係にある横軸を指す.言語における「系統」と「影響」という視点の対立は,生物分類学でいうところの「系統」と「段階」の対立に相似する.

分岐分類学 (cladistics) では,時間軸に沿った種分化の歴史を基盤とする「系統」の視点から,種どうしの関係づけがなされる.系統としての関係が互いに近ければ,形態特徴もそれだけ似ているのは自然だろう.だが,形態特徴が似ていれば即ち系統関係が近いかといえば,必ずしもそうならない.系統としては異なるが,環境の類似性などに応じて似たような形態が発達すること(収斂進化)があり得る.このような系統とは無関係の類似を,成因的相同 (homoplasy) という.系統的な近さではなく,成因的相同に基づいて集団をくくる分類の仕方は,「段階」 (grade) による区分と呼ばれる.

ウッド (70) を参考にして,現生高等霊長類を分類する方法を取り上げよう.「系統」の視点によれば,以下のように分類される.

ヒト族 チンパンジー族 ゴリラ族 オランウータン族 \ / / / \ / / / \ / / / \/ / / \ / / \ / / \ / / \ / \ / \ / \/ \ \ \

一方,「段階」の視点によれば,以下のように「ヒト科」と「オランウータン科」の2つに分類される.

ヒト科 オランウータン科 │ ┌─────────┼───────┐ │ │ │ ヒト族 チンパンジー族 ゴリラ族 オランウータン族

「段階」の区分法は,言語学でいえば,類型論 (typology) や言語圏 (linguistic_area) に基づく分類と似ているといえる.ただし,生物においても言語においても「段階」という用語とその含意には十分に気をつけておく必要がありそうだ.というのは,それは現時点における歴史的発達の「段階」によって区分するという考え方を喚起しやすいからだ.つまり,「段階」の上下や優劣という概念を生み出しやすい.「段階」の区分法は,あくまで共時的類似性あるいは成因的相同に基づく分類である,という点に留意しておきたい.

・ バーナード・ウッド(著),馬場 悠男(訳) 『人類の進化――拡散と絶滅の歴史を探る』 丸善出版,2014年.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2017-01-17 Tue

■ #2822. cross-linguistic influence [world_englishes][variety][language_contact][sla][terminology][sociolinguistics][language_contact]

「英語が○○語から影響を受けた」あるいは「英語が○○語に影響を与えた」という話題は,英語史でもよく話題とされる.しかし,「英語」も様々な変種の集合体であり,かつ「○○語」も1言語に限定されるわけではなく,無数の言語を指すと考えると,その影響関係は極めて複雑なネットワークとなるだろう.Baugh and Cable によると,このような影響関係は "cross-linguistic influence" (400) と呼ばれる.その実体は多角的で動的であるため,あまり研究も進んでいないようだが,今後の世界の言語状況,特に言語学習を巡る状況を理解する上で,非常に重要な概念となっていくのではないか.Baugh and Cable (400) は,これからの領域として注目している.

In projections of the future status of global languages, there has been little discussion of the reciprocal reinforcement that some of the major languages of the world give to each other---or what is known as "cross-linguistic influence." Spanish and Portuguese in Latin America, for example, indirectly boost the fortunes of English, or at least of English as a proficiently acquired foreign language, in comparison to languages that are less closely related to these Indo-European languages historically and typologically. Similarly, in the opposite direction there is a cross-linguistic influence of English on the learning of Spanish in the United States: knowledge of Spanish is diffused among many native English speakers in Texas in a way that Chinese in Northern California is not. One reason that research and discussion are lacking is that, until recently, most of the scholarship in foreign-language learning has concentrated on the differences between two languages rather than the similarities, with an emphasis on "interference."

この辺りは,第2言語習得の研究と広い意味での英語史(あるいは歴史社会英語学)と接点となる可能性が高い.もちろん,ほかにも code-switching や借用の研究などの言語接触論や,広く英語教育の議論にも関連してくると思われる.

英語史の名著の第6版にて,Baugh and Cable が最後に近い節で上のような "cross-linguistic influence" に言及していることは示唆的である.英語史は,21世紀の新しい英語学(より広く「英語の学」)を下から支える,頼りになる土台として,重要なポジションにある.

上の引用にあるラテン・アメリカにおける英語については,「#2610. ラテンアメリカ系英語変種」 ([2016-06-19-1]) も要参照.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2017-01-06 Fri

■ #2811. 部分語と全体語 [hyponymy][meronymy][lexicology][semantics][semantic_field][terminology]

「#1962. 概念階層」 ([2014-09-10-1]) や「#1961. 基本レベル範疇」 ([2014-09-09-1]) でみた概念階層 (conceptual hierarchy) あるいは包摂関係 (hyponymy) においては,例えば「家具」という上位語 (hypernym) の配下に「机」という下位語 (hyponym) があり,さらにその「机」が上位語となって,その下に「勉強机」や「作業机」という下位語が位置づけられる.ここでは,包摂という関係に基づいて,全体が階層構造をなしているのが特徴的である.

このような hyponymy と類似しているが区別すべき語彙的関係として,meronymy (部分と全体の関係)と呼ばれるものがある.例えば,「車輪」と「自転車」は部分と全体の関係にあり,「車輪」は「自転車」の meronym (部分語),「自転車」は「車輪」の holonym (全体語)と称される.meronymy においても hyponymy の場合と同様に,その関係は相対的なものであり,例えば「車輪」は「自転車」にとっては meronym だが,車輪を構成する「輻(スポーク)」にとっては holonym である.Cruse (105--06) からの meronymy の説明を示そう.

meronymy This is the 'part-whole' relation, exemplified by finger: hand, nose: face, spoke: wheel, blade: knife, harddisk: computer, page: book, and so on. The word referring to the part is called the 'meronym' and the word referring to the whole is called the 'holonym'. The names of sister parts of the same whole is called 'co-meronyms'. Notice that this is a relational notion: a word may be a meronym in relation to a second word, but a holonym in relation to a third. Thus finger is a meronym of hand, but a holonym of knuckle and fingernail. (Meronymy must not be confused with by hyponymy, although some of their properties are similar: for instance, both involve a type of 'inclusion', co-meronyms and co-taxonyms have a mutually exclusive relation, and both are important in lexical hierarchies. However, they are distinct: a dog is a kind of animal, but not a part of an animal; a finger is a part of a hand, but not a kind of hand.

meronymy と hyponymy は,いずれも「包摂」と「階層構造」を示す点で共通しているが,上の説明の最後にあるように,前者は part,後者は kind に対応するものであるという差異が確認される.また,meronymy では,部分と全体が互いにどのくらい必須であるかについて,hyponymy の場合よりも基準が明確でないことが多い.「顔」と「目」の関係はほぼ必須と考えられるが,「シャツ」と「襟」,「家」と「地下室」はどうだろうか.

さらに,hyponymy と meronymy は移行性 (transitivity) の点でも異なる振る舞いを示す.hyponymy では移行性が確保されているが,meronymy では必ずしもそうではない.例えば,「手」と「指」と「爪」は互いに meronymy の関係にあり,「手には指がある」と言えるだけでなく,「手には爪がある」とも言えるので,この関係は transitive とみなせる.しかし,「部屋」と「窓」と「窓ガラス」は互いに meronymy の関係にあるが,「部屋に窓がある」とは言えても「部屋に窓ガラスがある」とは言えないので,transitive ではない.

・ Cruse, Alan. A Glossary of Semantics and Pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2006.

2016-12-30 Fri

■ #2804. アイルランドにみえる母語と母国語のねじれ現象 [irish][terminology][linguistic_ideology]

「母語」という用語を巡る問題について「#1537. 「母語」にまつわる3つの問題」 ([2013-07-12-1]),「#1926. 日本人≠日本語母語話者」 ([2014-08-05-1]),「#2603. 「母語」の問題,再び」 ([2016-06-12-1]) の記事で考えてきた.「母語」と「母国語」とは本質的に異なる概念である.「母語」 (one's mother tongue) とは,個人が最初に習得し,自らの日常的な使用言語であるとみなしている言語のことであり,きわめて私的なものである.一方,「母国語」 (one's national language) とは「母国」である国家が公的に採用している言語を指し,定義上,公的なものである.それぞれの用語の前提にある態度が正反対であることに注意したい.

典型的な日本に生まれ育った日本人の場合,ほとんどのケースで「母語=母国語=日本語」の等式が成り立つだろう.したがって,日常の言説では,いちいち「母語」と「母国語」の用語を使い分ける必要性がほとんど感じられず,たいてい「母国語」で用を足している人が多いのではないか.しかし,古今東西,このような等式が成立しないケースは珍しくないどころか,普通といってよい.世界を見渡せば,多くの人々にとって「母語≠母国語」という状況がある.

母語と母国語のねじれた関係が,およそ国家単位で見られるという興味深い例が,昨日の記事「#2803. アイルランド語の話者人口と使用地域」 ([2016-12-29-1]) でも取り上げたアイルランドに見られる.嶋田著『英語という選択 アイルランドの今』を読むまで知らなかったのだが,アイルランド人は,アイルランド語を流ちょうに使えずとも,ときにその言語を「私たちの母国語」ではなく「私たちの母語」と表現することがあるという.ここには上に述べた用語の混乱という問題が含まれているが,むしろ,人々がこの用語のもつ曖昧さに訴えて,アイルランド語に対する自らの思いの丈を表明しているのだと解釈するほうが妥当だろう.つまり,「私たちの母なることば」というニュアンスに近い意味で「私たちの母語」と呼んでいるのだと.

嶋田 (25--26) は,1999年に行なったアンケート調査の自由記述欄から,アイルランド語を言い表す表現を集めた.

・ our true language

・ our national tongue

・ our native language

・ our native tongue

・ our own language

・ OUR language

・ our mother tongue

・ our original native language

口から発せられている言葉と口から発せられるべきと信じている言葉が異なっているというチグハグ感.用語遣いにみる「ねじれ現象」を前に,何とも表現しがたいが,悲哀を禁じ得ない.

・ 嶋田 珠巳 『英語という選択 アイルランドの今』 岩波書店,2016年.

2016-12-28 Wed

■ #2802. John Witherspoon --- Americanism の生みの親 [ame][americanism][terminology][webster][lexicography][witherspoon]

「アメリカ語法」を表わす Americanism という語を初めて用いたのは,初期のプリンストン大学の学長 John Witherspoon (1723--94) である.Witherspoon はスコットランド出身で,アメリカにて聖職者・教育者として活躍しただけでなく,独立宣言の署名者の1人でもある.

この語が造られた経緯について Baugh and Cable (380--81) に詳しいが,Witherspoon は1781年に Pennsylvania Journal 9 May 1/2 において Americanism という語を初めて用いたという.彼がこの表現に与えた定義は "an use of phrases or terms, or a construction of sentences, even among persons of rank and education, different from the use of the same terms or phrases, or the construction of similar sentences in Great-Britain." である.定義に続けて,Witherspoon は,"The word Americanism, which I have coined for the purpose, is exactly similar in its formation and signification to the word Scotticism." と述べている.実際,Scotticism という語は,OED によると時代的には1世紀半近く遡った1648年の Mercurius Censorius No. 1. 4 に,"It seemes you are resolved to..entertain those things which..ye have all this while fought against, the Scotticismes, of the Presbyteriall government and the Covenant." として初出している.

Witherspoon は Americanism という語を最初に用いたとき,そこに結びつけられがちな「卑しいアメリカ語法」という含意を込めてはいなかった.彼曰く,"It does not follow, from a man's using these, that he is ignorant, or his discourse upon the whole inelegant; nay, it does not follow in every case, that the terms or phrases used are worse in themselves, but merely that they are of American and not of English growth." ここには,イギリス(英語)に対して決して卑下しない,独立宣言の署名者らしい独立心を読み取ることができる.

タイトルに Americanism の語こそ含まれていなかったが,最初のアメリカ語法辞書が著わされたのは,造語から35年後の1816年のことである.John Pickering による A Vocabulary, or Collection of Words and Phrases which have been supposed to be Peculiar to the United States of America である.しかし,この辞書はむしろイギリス(英語)寄りの立場を取っており,アメリカ語法が正統なイギリス英語から逸脱していることを示すために用意されたとも思えるものである.同じアメリカ人ではあるが愛国主義者だった Noah Webster が,Pickering の態度に業を煮やしたことはいうまでもない.この Pickering と Webster の立場の違いは,後世に続く Americanism を巡る議論の対立を予感させるものだったといえる.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-11-09 Wed

■ #2753. dialect に対する language という用語について [dialect][terminology][sociolinguistics][language_or_dialect]

昨日の記事「#2752. dialect という用語について」 ([2016-11-08-1]) に引き続き Haugen (923) を参照しながら,dialect という用語と対比しつつ language という用語について考える.両用語が問題を呈するのは,それが記述的・共時的な用語であると同時に,歴史的・通時的な用語でもあるからだ.Haugen (923) 曰く,

In a descriptive, synchronic sense "language" can refer either to a single linguistic norm, or to a group of related norms. In a historical, diachronic sense "language" can either be a common language on its way to dissolution, or a common language resulting from unification. A "dialect" is then any one of the related norms comprised under the general name "language," historically the result of either divergence or convergence.

共時的には,"language" とは,1つの規範をもった変種を称する場合もあれば,関連する規範をもった複数の変種の集合体に貼りつけられたラベルである場合もある.一方,通時的には,"language" とは,これからちりぢりに分裂していこうとする元の共通祖語につけられた名前である場合もあれば,逆に諸変種が統合していこうとする先の標準変種の呼称である場合もある.

通時的に単純に図式化すれば「language → dialects → language → dialects → . . . 」となるが,"language" の前後の矢印の段階を輪切りにして共時的にみれば,そこには "language" を頂点として,その配下に "dialects" が位置づけられる図式が立ち現れてくるだろう.一方,"language" の段階では,"language" が唯一孤高の存在であり,配下に "dialects" なるものは存在しない.ここから,"language" には多義性が生じるのである.Haugen (923) は,この用語遣いの複雑さを次のように表現している.

"Language" as the superordinate term can be used without reference to dialects, but "dialect" is meaningless unless it is implied that there are other dialects and a language to which they can be said to "belong." Hence every dialect is a language, but not every language is a dialect.

最後の「すべての方言は言語だが,すべての言語が方言とはかぎらない」とは,言い得て妙である.

・ Haugen, Einar. "Dialect, Language, Nation." American Anthropologist. 68 (1966): 922--35.

2016-11-08 Tue

■ #2752. dialect という用語について [greek][terminology][dialect][standardisation][koine][literature][register][language_or_dialect][dialect_levelling]

Haugen (922--23) によれば,dialect という英単語は,ルネサンス期にギリシア語から学術用語として借用された語である.OED の「方言」の語義での初例は1566年となっており,そこでは英語を含む土着語の「方言」を表わす語として用いられている.フランス語へはそれに先立つ16年ほど前に入ったようで,そこではギリシア語を評して abondante en dialectes と表現されている.1577年の英語での例は,"Certeyne Hebrue dialectes" と古典語に関するものであり,1614年の Sir Walter Raleigh の The History of the World では,ギリシア語の "Æeolic Dialect" が言及されている.英語での当初の使い方としては,このように古典語の「方言」を指して dialect という用語が使われることが多かったようだ.そこから,近代当時の土着語において対応する変種の単位にも応用されるようになったのだろう.

ギリシア語に話を戻すと,古典期には統一した標準ギリシア語なるものはなく,標準的な諸「方言」の集合体があるのみだった.だが,注意すべきは,これらの「方言」は,話し言葉としての方言に対してではなく,書き言葉としての方言に対して与えられた名前だったことである.確かにこれらの方言の名前は地方名にあやかったものではあったが,実際上は,ジャンルによって使い分けられる書き言葉の区分を表わすものだった.例えば,歴史書には Ionic,聖歌歌詞には Doric,悲劇には Attic などといった風である (see 「#1454. ギリシャ語派(印欧語族)」 ([2013-04-20-1])) .

これらのギリシア語の書き言葉の諸方言は,元来は,各地方の話し言葉の諸方言に基盤をもっていたに違いない.後者は,比較言語学的に再建できる古い段階の "Common Greek" が枝分かれした結果の諸方言である.古典期を過ぎると,これらの話し言葉の諸方言は消え去り,本質的にアテネの方言であり,ある程度の統一性をもった koiné によって置き換えられていった (= koinéization; see 「#1671. dialect contact, dialect mixture, dialect levelling, koineization」 ([2013-11-23-1])) .そして,これがギリシア語そのもの (the Greek language) と認識されるようになった.

つまり,古典期からの歴史をまとめると,"several Greek dialects" → "the Greek language" と推移したことになる.諸「方言」の違いを解消して,覇権的に統一したもの,それが「言語」なのである.本来この歴史的な意味で理解されるべき dialect (と language)という用語が,近代の土着語に応用される及び,用語遣いの複雑さをもたらすことになった.その複雑さについては,明日の記事で.

・ Haugen, Einar. "Dialect, Language, Nation." American Anthropologist. 68 (1966): 922--35.

2016-11-01 Tue

■ #2745. Haugen の言語標準化の4段階 (2) [standardisation][sociolinguistics][terminology][register][style][language_planning]

[2016-10-29-1]の記事に引き続き,標準化 (standardisation) の過程に認められる4段階について,Haugen を参照する.標準化は,時系列に (1) Selection, (2) Codification, (3) Elaboration, (4) Acceptance の順で進行するとされるが,この4つの過程と順序は,社会と言語,および形式と機能という2つの軸で整理することができる (下図は Haugen 933 をもとに作成).

| Form | Function | ||

| Society | (1) Selection | (4) Acceptance | |

| ↓ | ↑ | ||

| Language | (2) Codification | → | (3) Elaboration |

まずは,規範となる変種を選択 (Selection) することから始まる.ここでは,社会的に威信ある優勢な変種がすでに存在しているのであれば,それを選択することになるだろうし,そうでなければ既存の変種を混合するなり,新たに策定するなどして,標準変種の候補を作った上で,それを選択することになろう.

第2段階は成文化 (Codification) であり,典型的には,選択された言語変種に関する辞書と文法書を編むことに相当する.標準的となる語彙項目や文法項目を具体的に定め,それを成文化して公開する段階である.ここでは,"minimum variation in form" が目指されることになる.

第3段階の精巧化 (Elaboration) においては,その変種が社会の様々な場面,すなわち使用域 (register) や文体 (style) で用いられるよう,諸策が講じられる.ここでは,"maximum variation in function" が目指されることになる.

最後の受容 (Acceptance) の段階では,定められた変種が社会に広く受け入れられ,使用者数が増加する.これにより,標準化の全過程が終了する.

社会・言語,および形式・機能という2つの軸からなるマトリックスにより,標準化の4段階が体系としても時系列としてもきれいに整理されてしまうのが見事である.この見事さもあって,Haugen の理論は,現在に至るまで標準化の議論の土台を提供している.

・ Haugen, Einar. "Dialect, Language, Nation." American Anthropologist. 68 (1966): 922--35.

2016-10-29 Sat

■ #2742. Haugen の言語標準化の4段階 [standardisation][sociolinguistics][terminology][language_or_dialect][language_planning]

昨日の記事「#2741. ascertaining, refining, fixing」 ([2016-10-28-1]) で,17世紀までの英語標準化から18世紀にかけての英語規範化へと続く時代の流れを見た.

一言で「標準化」 (standardisation) といっても,その過程にはいくつかの局面が認められる.Haugen の影響力の強い論文によれば,ある言語変種が標準化するとき,典型的には4つの段階を経るとされる.Hudson (33) による社会言語学の教科書からの引用を通じて,この4段階を要約しよう.

(1) Selection --- somehow or other a particular variety must have been selected as the one to be developed into a standard language. It may be an existing variety, such as the one used in an important political or commercial centre, but it could be an amalgam of various varieties. The choice is a matter of great social and political importance, as the chosen variety necessarily gains prestige and so the people who already speak it share in this prestige. However, in some cases the chosen variety has been one with no native speakers at all --- for instance, Classical Hebrew in Israel and the two modern standards for Norwegian . . . .

(2) Codification --- some agency such as an academy must have written dictionaries and grammar books to 'fix' the variety, so that everyone agrees on what is correct. Once codification has taken place, it becomes necessary for any ambitious citizen to learn the correct forms and not to use in writing any 'incorrect' forms that may exist in their native variety.

(3) Elaboration of function --- it must be possible to use the selected variety in all the functions associated with central government and with writing: for example, in parliament and law courts, in bureaucratic, educational and scientific documents of all kinds and, of course, in various forms of literature. This may require extra linguistic items to be added to the variety, especially technical words, but it is also necessary to develop new conventions for using existing forms --- how to formulate examination questions, how to write formal letters and so on.

(4) Acceptance --- the variety has to be accepted by the relevant population as the variety of the community --- usually, in fact, as the national language. Once this has happened, the standard language serves as a strong unifying force for the state, as a symbol of its independence of other states (assuming that its standard is unique and not shared with others), and as a marker of its difference from other states. It is precisely this symbolic function that makes states go to some lengths to develop one.

当然ながら,いずれの段階においても,多かれ少なかれ,社会による意図的で意識的な関与が含まれる.標準語の出来方はすぐれて社会的な問題であり,常に人工的,政治的な匂いがまとわりついている.「社会による意図的な介入」の結果としての標準語という見解については,上の引用に先立つ部分に,次のように述べられている (Hudson 32) .

Whereas one thinks of normal language development as taking place in a rather haphazard way, largely below the threshold of consciousness of the speakers, standard languages are the result of a direct and deliberate intervention by society. This intervention, called 'standardisation', produces a standard language where before there were just 'dialects' . . . .

関連して,「#1522. autonomy と heteronomy」 ([2013-06-27-1]) を参照.

・ Haugen, Einar. "Dialect, Language, Nation." American Anthropologist. 68 (1966): 922--35.

・ Hudson, R. A. Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 1996.

2016-10-24 Mon

■ #2737. 現代イギリス英語における所有代名詞 hern の方言分布 [map][personal_pronoun][suffix][dialect][terminology]

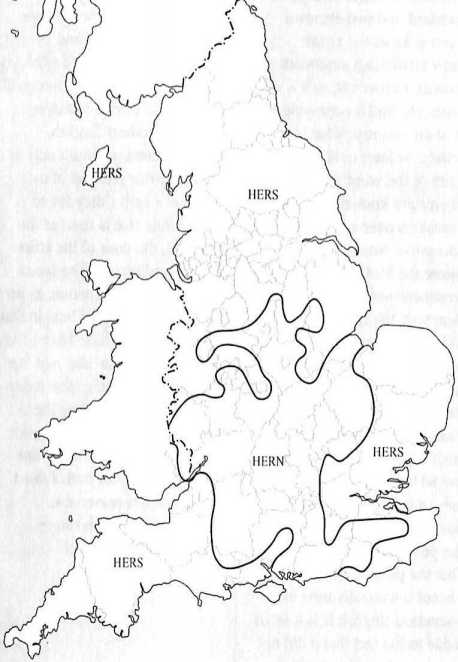

「#2734. 所有代名詞 hers, his, ours, yours, theirs の -s」 ([2016-10-21-1]) の記事で,-s の代わりに -n をもつ,hern, hisn, ourn, yourn, theirn などの歴史的な所有代名詞に触れた.これらの形態は標準英語には残らなかったが,方言では今も現役である.Upton and Widdowson (82) による,hern の方言分布を以下に示そう.イングランド南半分の中央部に,わりと広く分布していることが分かるだろう.

-n 形については,Wright (para. 413) でも触れられており,19世紀中にも中部,東部,南部,南西部の諸州で広く用いられていたことが知られる.

-n 形は,非標準的ではあるが,実は体系的一貫性に貢献している.mine, thine も含めて,独立用法の所有代名詞が一貫して [-n] で終わることになるからだ.むしろ,[-n] と [-z] が混在している標準英語の体系は,その分一貫性を欠いているともいえる.

なお,my と mine のような用法の違いは,Upton and Widdowson (83) によれば,限定所有代名詞 (attributive possessive pronoun) と叙述所有代名詞 (predicative possessive pronoun) という用語によって区別されている.あるいは,conjunctive possessive pronoun と disjunctive possessive pronoun という用語も使われている.

・ Upton, Clive and J. D. A. Widdowson. An Atlas of English Dialects. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge, 2006.

・ Wright, Joseph. The English Dialect Grammar. Oxford: OUP, 1905. Repr. 1968.

2016-10-15 Sat

■ #2728. steganography [steganography][cryptology][terminology]

cryptology (クリプトグラフィ)とは異なるが,広い意味で暗号作成法の1つとみなせるものに,steganography (ステガノグラフィ)がある.ギリシア語の stégeín (to cover) と grápheín (to write) に基づく連結形からなり,いわば「覆い書き,隠し書き」である (cf. stegosaur は「よろいで覆われた恐竜」の意;英語 thatch も印欧祖語の同根 *steg- に遡る).クリプトグラフィが,誰でも暗号であると見てすぐに分かるような典型的な暗号を指すのに対して,ステガノグラフィはそれを見ても,そもそも暗号があるとは気づかないタイプを指す.例えば,乾くと消える明礬水などで紙にメッセージを書き,火であぶれば文字が浮き出す「あぶり出し」が,ステガノグラフィの1つの典型である.メッセージそのものに手を加えて言語的に解釈するのを難しくするのではなく,メッセージはいじらずに,暗号者と復号者の間に回路が開いていること自体を悟られないようにする秘匿法である(ただし,両者を組み合わせて秘匿の度合いを高めるという場合もある).

ステガノグラフィの種類を分類すると,以下のようになる(詳しくは,リクソン(著)『暗号解読事典』の4章「ステガノグラフィ」 (pp. 398--431) を参照).

┌─── 物理的隠匿 │ ステガノグラフィ ───┤ ┌─── セマグラム │ │ └─── 言語的隠匿 ───┤ │ └─── その他

物理的秘匿とは,上の「あぶり出し」(隠顕)を始めとして,スパイ小説などでお馴染みのように,隠された仕切り・ポケット・くりぬいた本・傘の柄などにメッセージを埋め込んだりする手法や,頭髪を剃り落として頭皮にメッセージを書いた上で髪を伸ばして隠す方法,蜜蝋を塗って文字を隠した書字板など,各種の方法がある.極小の字を書き込んで,文字の存在自体を悟られないようにするのも,この一種だろう.

言語的隠匿は,一歩,クリプトグラフィに近い.まず「セマグラム」と呼ばれる方法がある.リクソン (408) によると,「ドミノの点,予め決めておいた意味をお伝えるような位置に置いた写真の中の被写体,あるいは絵の中で,木の短い枝と長い枝がモールス符号のトンツーを表すようにしておくのである.第三者にとっては,そこに情報が隠されているとは判らない」.要するに,一見何の変哲もない絵や図のなかに,関与者にしかわからない形で(代替)言語的メッセージを埋め込んでおくものである.

その他の言語的隠匿法として,何の変哲もない自然な文章のなかに,密かに秘密のメッセージを隠す種々のやり方がある.怪しくない普通の文章の各単語の頭文字だけを拾っていくと重要なキーワードになっていたり (cf. 「#1875. acrostic と折句」 ([2014-06-15-1])),特定の文字の字体を微妙に変えて合図したり,部分的に穴の空いた金属板(=グリル)を文章の上に重ねて,穴の部分のみを読むとメッセージになっていたり,ある語句の存在・不在が何らかのコードとなっているものなど,様々なものがある.

ステガノグラフィは気づかれてしまったら最後という弱点があるし,作成に時間がかかるなどの理由で,秘匿メッセージが日常的に大量にやりとりされる戦時中などにはさほど用いられなかった.暗号の歴史を通じて,主流はステガノグラフィではなくクリプトグラフィだったのである.つまり,秘匿メッセージであること,秘匿メッセージをやりとりしていること,秘匿方法(アルゴリズム)の種類をむしろ公開してしまい,ある意味で堂々と復号者に挑戦状をたたきつけるような方法が主流となってきたのである.通常の言語コミュニケーションで喩えれば,「コソコソした内緒話し」ではなく「堂々と翻訳で勝負」が主流となってきた,というところか.

・ フレッド・B・リクソン(著),松田 和也(訳) 『暗号解読事典』 創元社,2013年.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow