2018-08-23 Thu

■ #3405. esoterogeny と exoterogeny [sociolinguistics][contact][lingua_franca][sociolinguistics][simplification][terminology][accommodation_theory][suppletion]

「#1585. 閉鎖的な共同体の言語は複雑性を増すか」 ([2013-08-29-1]) で "esoterogeny" という概念に触れた.ある言語共同体が,他の共同体に対して排他的な態度をとるようになると,その言語をも内にこもった複雑なものへと,すなわち "esoteric" なものへと変化させるという仮説だ.裏を返せば,他の共同体に対して親密な態度をとるようになれば,言語も開かれた単純なものへと,すなわち "exoteric" なものへと変化するとも想定されるかもしれない.この仮説の真偽については未解決というべきだが,刺激的な考え方ではある.Campbell and Mixco の用語集より,両術語の解説を引用する.

esoterogeny 'A sociolinguistic development in which speakers of a language add linguistic innovations that increase the complexity of their language in order to highlight their distinctiveness from neighboring groups' . . . ; 'esoterogeny arises through a group's desire for exclusiveness' . . . . Through purposeful changes, a particular community language becomes the 'in-group' code which serves to exclude outsiders . . . . A difficulty with this interpretation is that it is not clear how the hypothesized motive for these changes --- conscious (sometimes subconscious) exclusion of outsiders . . . --- could be tested or how changes motivated for this purpose might be distinguished from changes that just happen, with no such motive. The opposite of esoterogeny is exoterogeny. (55)

exoterogeny 'Reduces phonological and morphological irregularity or complexity, and makes the language more regular, more understandable and more learnable' . . . . 'If a community has extensive ties with other communities and their . . . language is also spoken as a contact language by members of those communities, then they will probably value their language for its use across community boundaries . . . it will be an "exoteric" lect [variety]' . . . . Use by a wider range of speakers makes an exoteric lect subject to considerable variability, so that innovations leading to greater simplicity will be preferred.

The claim that the use across communities will lead to simplification of such languages does not appear to hold in numerous known cases (for example, Arabic, Cuzco Qechua, Georgian, Mongolian, Pama-Nyungan, Shoshone etc.). The opposite of exoterogeny is esoterogeny. (59--60)

exoterogeny と esoterogeny という2つの対立する概念は,カルヴェのいう「#1521. 媒介言語と群生言語」 ([2013-06-26-1]) の対立とも響き合う.平たくいえば,「開かれた」言語(社会)と「閉ざされた」言語(社会)の対立といっていいが,これが言語の単純化・複雑化とどう結びつくのかは,慎重な議論を要するところだ.「#1482. なぜ go の過去形が went になるか (2)」 ([2013-05-18-1]) では,私はこの補充法の問題について esoterogeny の考え方を持ち出して説明したことになるし,「#1247. 標準英語は言語類型論的にありそうにない変種である」 ([2012-09-25-1]) で紹介した Hope の議論も,標準英語の偏屈な文法を esoterogeny によって説明したもののように思われる.だが,これも1の仮説の段階にとどまるということは意識しておかなければならない.

そもそも言語の「単純化」 (simplification) とは何を指すのかについて,諸家の間で議論があることを指摘しておこう (cf. 「#928. 屈折の neutralization と simplification」 ([2011-11-11-1]),「#1839. 言語の単純化とは何か」 ([2014-05-10-1]),「#3228. Joseph の言語変化に関する洞察,5点」 ([2018-06-07-1])) .また,どのような場合に単純化が生じるかについても,言語接触 (contact) との関係で様々な考察がある (cf. 「#1788. 超民族語の出現と拡大に関与する状況と要因」 ([2014-03-20-1]),「#3151. 言語接触により言語が単純化する機会は先史時代にはあまりなかった」 ([2017-12-12-1])) .

・ Campbell, Lyle and Mauricio J. Mixco, eds. A Glossary of Historical Linguistics. Salt Lake City: U of Utah P, 2007.

2018-08-11 Sat

■ #3393. コミュニケーションとは? [terminology][communication][information_theory]

コミュニケーション (communication) は,言語学でもよく使われる用語だが,一方で日常的に広く使われる用語でもある.実際,言語学でもかなり緩く用いられている.定義を確かめておこうと思い,Crystal の言語学辞典を引いてみた.それによると,communication とは次の通りである (89--90) .

communication (n.) A fundamental notion in the study of behaviour, which acts as a frame of reference for linguistic and phonetic studies. Communication refers to the transmission and reception of information (as 'message') between a source and a receiver using a signalling system: in linguistic contexts, source and receiver are interpreted in human terms, the system involved is a language, and the notion of response to (or acknowledgement of) the message becomes of crucial importance. In theory, communication is said to have taken place if the information received is the same as that sent: in practice, one has to allow for all kinds of interfering factors, or 'noise', which reduce the efficiency of the transmission (e.g. unintelligibility of articulation, idiosyncratic associations of words). One has also to allow for different levels of control in the transmission of the message: speakers' purposive selection of signals will be accompanied by signals which communicate 'despite themselves', as when voice quality signals the fact that a person has a cold, is tired/old/male, etc. The scientific study of all aspects of communication is sometimes called communication science: the domain includes linguistics and phonetics, their various branches, and relevant applications of associated subjects (e.g. acoustics, anatomy).

Human communication may take place using any of the available sensory modes (hearing, sight, etc.), and the differential study of these modes, as used in communicative activity, is carried on by semiotics. A contrast which is often made, especially by psychologists, is between verbal and non-verbal communication (NVC) to refer to the linguistic v. the non-linguistic features of communication (the latter including facial expressions, gestures, etc., both in humans and animals). However, the ambiguity of the term 'verbal' here, implying that language is basically a matter of 'words', makes this term of limited value to linguistics, and it is not usually used by them in this way.

いろいろと説明されているが,核心部分を端的に解釈すれば,コミュニケーションとは「2者間における信号体系を用いた情報の精確なやりとり」となろう.言語は,このようなコミュニケーションを達成するための手段の1つということになる.しかし,言語はコミュニケーションのためだけに用いられているわけではない.言語は,しばしば上記のコミュニケーションの定義から逸脱するような用いられ方もする.言語の諸機能 (function_of_language) については,以下の記事を参照されたい.「#523. 言語の機能と言語の変化」 ([2010-10-02-1]),「#1071. Jakobson による言語の6つの機能」 ([2012-04-02-1]),「#1862. Stern による言語の4つの機能」 ([2014-06-02-1]),「#1776. Ogden and Richards による言語の5つの機能」 ([2014-03-08-1]) .

もちろん,コミュニケーションの定義に含まれる「情報」 (information) とは何か,という大きな問題が残っている.これも厄介な問題だが,当面は「#1089. 情報理論と言語の余剰性」 ([2012-04-20-1]),「#1098. 情報理論が言語学に与えてくれる示唆を2点」 ([2012-04-29-1]) を含む information_theory の各記事を参照されたい.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2018-07-26 Thu

■ #3377. 音韻変化の原因2種と結果3種 [sound_change][phonetics][phonology][merger][terminology][phoneme][phonemicisation][how_and_why][multiple_causation]

服部 (48) は,音韻変化 (phonological change) の原因として大きく2種を区別している.

(1) 言語内的動機づけによるもの (endogenous or internal motivations): 主として音声学的・音韻論的な要因

(2) 言語外的動機づけによるもの (exogenous or external motivations): 他言語・他方言との接触,社会的・文化的状況などの社会言語学的な要因

きわめて理解しやすい分類である.しかし,従来 (2) の言語外的要因が軽視されてきた事実を指摘しておきたい.非常に多くの音韻変化は,確かに (1) の言語内的要因によってスマートに説明されてきたし,今後もそうだろう.しかし,どちらかというと (1) の説明は,起こった音韻変化の WHY の説明ではなく,HOW の記述にとどまることが多い.当該の音韻変化が特定の時期に特定の場所で起こるのはなぜかという「始動問題」 (actuation problem) には力不足であり,WHY に迫るにはどうしても (2) に頼らざるを得ない.

一方,音韻変化を,変化の結果として音韻体系がどのように影響を受けたかという観点から分類すれば,以下の3種類に分けられる(服部,pp. 47--48).

(1) 融合 (merger): 複数の音素が対立を失い,1つの音素に合体する.

(2) 分裂 (split): 単一の音素が複数の音素に分裂すること.もし分裂した結果の音が他の音素と融合し,音素の総数が変わらない場合には,それを一次分裂 (primary split) と呼ぶ.一方,分裂の結果,新たな音素が生じた場合には,それを二次分裂 (secondary split) と呼ぶ.

(3) 推移 (shift): ある分節音が音質を変化させた結果,音韻体系が不安定となった場合に,それを安定化させるべく別の分節音が連鎖的に音質を変化させること.

ここで注意したいのは,(1) と (2) は音韻体系に影響を与える変化であるが,(3) では変化の前後で音韻体系そのものは変わらず,各音素が語彙全体のなかで再分布される結果になるということだ.椅子取りゲームに喩えれば,(1) と (2) では椅子の種類や数が変わり,(3) では椅子どうしの相対的な位置が変わるだけということになる.

・ 服部 義弘 「第3章 音変化」服部 義弘・児馬 修(編)『歴史言語学』朝倉日英対照言語学シリーズ[発展編]3 朝倉書店,2018年.47--70頁.

2018-06-17 Sun

■ #3338. 最小限の英文法用語一覧 [terminology][hel_education]

若林俊輔(著)『英語の素朴な疑問に答える36章』に,英語教育において用いられるべき最低限の文法用語として,以下のものが掲載されている (198--99) .これは,1984年に財団法人語学教育研究所の研究大会で発表された「中学校・高等学校における文法用語 101」のリストである.* 印は中学校における文法用語,無印は高校で初めて導入される(べき)文法用語である.若林もこのプロジェクト・メンバーの1人だった.

*文 平叙文 肯定文 否定文 *疑問文 付加疑問 *命令文 *感嘆文 *文型 *主語 述語動詞 主部 述部 形式主語 補語 *目的語 形式目的語 SV SVC SVO SVOO SVOC 修飾語句 *品詞 *語 *単語 *語尾 *名詞 *数えられる名詞 *数えられない名詞 *固有名詞 *単数(形) *複数(形) *1人称 *2人称 *3人称 *主格 *所有格 *目的格 *代名詞 人称代名詞 *動詞 *活用 自動詞 他動詞 *be 動詞 知覚動詞 使役動詞 *助動詞 冠詞 *形容詞 *副詞 *前置詞 *接続詞 *疑問詞 間投詞 *関係代名詞 関係副詞 *先行詞 *原形 *現在形 *過去形 未来形 *進行形 *現在進行形 *過去進行形 未来進行形 *完了形 *現在完了形 過去完了形 未来完了形 受動態 能動態 *受身形 不定詞 分詞 現在分詞 *過去分詞 *-ing 形 分詞構文 動名詞 *原級 *比較級 *最上級 仮定法 部分否定 *句 名詞句 形容詞句 副詞句 節 名詞節 形容詞節 副詞節 主節 従属節 *名詞用法 *形容詞用法 *副詞用法 制限用法 非制限用法

若林 (199) も述べている通り,このリストは,「受動態」と「受身形」の混在なども含め,多くの妥協の産物である.用語の選定の難しさについて,若林は次のようにコメントしている (200) .

私は,この表を作成した当時もそうであったのだが,「文法用語」の整理・削減はなかなか困難な仕事であると思っている.それは,英語教師一人一人の「文法用語」の一つ一つへの思い入れがあるからである.楽しく,あるいは,苦しみながら習い覚えた「用語」が懐かしくてしかたがない.ノスタルジアである.

私は,ノルタルジアでは教育はできないと考えている.この種のノスタルジアは,しばしば,マイナス効果しかもたらさない.しばしば,生徒たちの学習を混乱させる.用意であるべき学習を困難なものに変質させる.進歩すべき教授・学習の足を引っ張る.後退させる.

英語学としては用語や概念は多数必要だろう.なかには不要なものもあるとはいえ,言語という複雑なものを研究し,整理するためには様々な切り口が必要であり,それに伴って用語が膨らんでいくのも無理からぬことである.しかし,英語教育ということになれば,学習者のメリットになるように用語を整理(多くの場合,削減)することが必要であることは論を俟たない.とはいえ,である.ノスタルジアというのは,とてもよく分かってしまう表現なのだ.

英語史研究でも同様に,専門的な用語が洪水のように現われるのは致し方ないにせよ,最初の導入の段階では最小限度に収めようとする努力は必要だろうと思う.

・ 若林 俊輔 『英語の素朴な疑問に答える36章』 研究社,2018年.

2018-05-24 Thu

■ #3314. 英語史における「言文一致運動」 [japanese][terminology][medium][writing][emode][latin][style][genbunicchi]

言葉は,媒体の観点から大きく「話し言葉」と「書き言葉」に分かれる.書き言葉はさらに,フォーマリティの観点から「口語体」と「文語体」に分かれる.野村 (5) を参照して図示すると次の通り.

┌── 話し言葉

言葉 ──┤ ┌── 口語体

└── 書き言葉 ──┤

└── 文語体

言語史を考察する場合には,しばしば後者の区分について意識的に理解しておくことが肝心である.現在の日本語でいえば,書き言葉といえば,通常は口語体のことを指す.この記事の文章もうそうだし,新聞でも教科書でも小説でも,日常的に読んでいるもののほとんどが,日常の話し言葉をもとにした口語体である.しかし,明治時代までは漢文や古典日本語に基づいた文語体が普通だった.言文一致運動は,文語体から口語体への移行を狙う運動だったわけだ.

英語史においても,口語体と文語体の区別を意識しておくのがよい.中世から近代初期にかけて,イングランドにおける主たる書き言葉といえばラテン語(およびフランス語)だった.日常的には話し言葉で英語を使っていながら,筆記する際にはそれに基づいた口語体ではなく,外国語であるラテン語を用いていたのである.英語史における文語体とは,すなわち,ラテン語のことである.

日英語における文語体の違いは,日本語では古典日本語に基づいたものであり,英語では外国語に基づいたものであるという点だ.だが,日常的に用いている話し言葉からの乖離が著しい点では一致している.近代初期にかけてのイングランドでは,書き言葉がラテン語から英語へと切り替わったが,この動きはある種の言文一致運動と表現することができる.なお,厳密な表音化を目指す綴字改革 (spelling_reform) も言文一致運動の一種とみなすことができるが,ここでは古典語たるラテン語が俗語たる英語にダイナミックに置き換わっていく過程,すなわち書き言葉の vernacularisation を指して「言文一致運動」と呼んでおきたい.

この英語史における「言文一致運動」については,とりわけ「#1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題」 ([2013-03-04-1]) や「#2580. 初期近代英語の国語意識の段階」 ([2016-05-20-1]),「#2611. 17世紀中に書き言葉で英語が躍進し,ラテン語が衰退していった理由」 ([2016-06-20-1]) を参照されたい.

・ 野村 剛史 『話し言葉の日本史』 吉川弘文館,2011年.

2018-05-22 Tue

■ #3312. 言語における基層と表層 [linguistics][language_acquisition][media][writing][borrowing][terminology]

標題は生成文法を語ろうとしているわけではない.言語を構成する諸部門を大きく2つの層に分けると,それぞれを「基層」「表層」と名付けられるだろうというほどのものだ.しかし,言語学上,この2区分の波及効果は大きい.野村 (12) の説明が明快である.

ある言語(方言で考えてもらってもよい)のさまざまな要素は,おおむねその言語の基層と表層に振り分けられる.文法や音声・音韻や基礎的な語彙は,基層に属する.文化的な(「高級な」)語彙,言い回し・表現法(広義のレトリック),文体などは,表層に属する.ある言語の使い手は,基層に属する部分を子供時代に無意識的に習得してしまう.表層に属する部分は,教育と学習によって徐々に身につける.独創ともなれば,なおさらの努力が必要である.

基層と表層の区別が,言語習得における段階と連動していることはいうまでもない.また,この区別は,話し言葉と書き言葉の区別,あるいは書き言葉のなかでの口語体と文語体の区別とも連動することが,続く野村の文章で触れられている (12) .

書き言葉口語体は,文化語彙,言い回し・表現法,文体などの表層部分では,必ずしも話し言葉には従っていない.しかし,基層に属する文法や音声・音韻,基礎語彙などの面で,話し言葉のそれらに従っている.一方,「文語体」(古典語をもとにした文語体)は,文法,音韻,基礎語彙などの面で,古典語のそれらに従っているのである.

基層と表層の区別はまた,他言語からの借用に対して開かれている程度にも関係するだろう.基層は他言語からの干渉を比較的受けにくいが,表層では受けやすいということはありそうだ.この問題については,「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1]),「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]),「#2011. Moravcsik による借用の制約」 ([2014-10-29-1]) の記事や,「#2067. Weinreich による言語干渉の決定要因」 ([2014-12-24-1]) も参照されたい.

・ 野村 剛史 『話し言葉の日本史』 吉川弘文館,2011年.

2018-05-18 Fri

■ #3308. Cosmopolitan Vocabulary という表現について [pde_characteristic][loan_word][terminology]

Baugh and Cable の掲げる現代英語の特徴の第1番目が,標題の Cosmopolitan Vocabulary,すなわち語彙の世界性である.著者らは,これを "an undoubted asset" として,すなわち間違いなく現代英語の強みであり利点であるとして肯定的に評価している.しかし,私は「#153. Cosmopolitan Vocabulary は Asset か?」 ([2009-09-27-1]),「#390. Cosmopolitan Vocabulary は Asset か? (2)」 ([2010-05-22-1]),「#2359. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由 (3)」 ([2015-10-12-1]) で論じてきたように,この見方に懐疑的である.少なくとも "undoubted" と強調するほどの "asset" かどうかは,はなはだ疑わしいと考えている.ここで議論を繰り返すことはしないが,1つ気づいたことがあったので触れておきたい.そもそも Baugh and Cable が cosmopolitan という表現を用いていること自体が,この現代英語の特徴を肯定的に見ていることの証だという点である.

cosmopolitan は「全世界的な;世界主義的な;(幅広い国際経験で)都会的な,洗練された,上品な」ほどの語義をもち,もとより肯定的な含意を有する形容詞である.つまり,cosmopolitan vocabulary という特徴をこの言い方で取り上げた時点で,Baugh and Cable は現代英語が洗練された語彙をもつ洗練された言語であることを示唆しているのである.学習者用の辞典をいくつか繰ってみると,OALD8 では次のようにあった.

1 containing people of different types or from different countries, and influenced by their culture

2 having or showing a wide experience of people and things from many different countries

ここでは,定義のなかで肯定的な含意は特に明示されていないが,語義2において wide はプラスイメージである.LDOCE5 では,語義1についてではあるが,"use this to show approval" と肯定的なコメントが付けられている.

1. a cosmopolitan place has people from many different parts of the world --- use this to show approval

2. a cosmopolitan person, belief, opinion etc shows a wide experience of different people and places

次に COBUILD Thesaurus では,cosmopolitan の類義語として "sophisticated, broad-minded, catholic, open-minded, universal, urbane, well-travelled, worldly-wise" が挙げられている.いずれもプラスの評価といっていい.

この特徴を必ずしも asset とはみなせないという私の立場からすると,そもそも "cosmopolitan vocabulary" と呼ぶこと自体が不適切のように思えてきた.中立的な言い方をすると,"vocabulary of various (linguistic) origins" 辺りだろうか.確かにおもしろくも何ともないネーミングだけれども.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2018-05-17 Thu

■ #3307. 文法用語としての participle 「分詞」 [terminology][grammar][etymology][sobokunagimon][loan_translation][participle]

現在分詞 (present participle) と過去分詞 (past participle) は,英語の動詞が取り得る形態のうちの2種類に与えられた名前である.しかし,「分詞」 participle というネーミングは何なのだろうか.何が「分」かれているというのか,何の part だというのか.今回は,この文法用語の問題に迫ってみたい.

この語は直接にはフランス語からの借用語であり,英語では a1398 の Trevisa において,ラテン語 participii (主格単数形は participium)に対応するフランス語化した語形 participles として初出している.最初から文法用語として用いられている.

では,ラテン語の participium とはどのような語源・語形成なのか.この単語は pars "part" + capere "to take" という2つの語根から構成されており,「分け前を取る」が原義である.動詞 participate は同根であり,「参加する」の意味は,「分け前を取る」=「分け合う」=「その集団に加わっている」という発想からの発展だろう.partake や take part も,participate のなぞりである.さらにいえば,ラテン語 participium 自体も,同義のギリシア語 metokhḗ からのなぞりだったのである.

さて,問題の文法用語において「分け前を取る」「分け合う」「参加する」とは何のことを指すのかといえば,動詞と形容詞の機能を「分け合う」ということらしい.1つの単語でありながら,片足を動詞に,片足を形容詞に突っ込んでいることを participle 「分詞」と表現したわけだ.なお,現在では廃義だが,participle には「二つ以上の異なった性質を合わせもつ人[動物,もの]」という語義もあった.2つの品詞に同時に参加し,2つの性質を合わせもつ語,それが「分詞」だったのである.

なお,上記の説明は,古英語でラテン文法書を著わした Ælfric にすでに現われている.OED の participle, n. and adj. に載せられている引用を再掲しよう.なお,ラテン語の場合には名詞と形容詞は同類なので,Ælfric の解説では,合わせもつものは動詞と名詞となっていることに注意.

OE Ælfric Gram. (St. John's Oxf.) 9 [sic]PARTICIPIVM ys dæl nimend. He nymð anne dæl of naman and oðerne of worde. Of naman he nymð CASVS, þæt is, declinunge, and of worde he nymð tide and getacnunge. Of him bam he nymð getel and hiw. Amans lufiende cymð of ðam worde amo ic lufige.

他の文法用語の問題については,「#1258. なぜ「他動詞」が "transitive verb" なのか」 ([2012-10-06-1]),「#1520. なぜ受動態の「態」が voice なのか」 ([2013-06-25-1]) も参照.

2018-04-21 Sat

■ #3281. Hopper and Traugott による文法化の定義と本質 [grammaticalisation][terminology][language_change]

Hopper and Traugott による文法化 (grammaticalisation) の定義および捉え方を紹介しておきたい.文法化というとき,それは言語変化のあるパターンを指すこともあれば,そのような言語変化を研究する枠組みのことを指すこともある.まずは,Hopper and Traugott (231) より,その辺りの定義から.

. . . we have considered grammaticalization as (i) a research framework for studying the relationships between lexical, constructional, and grammatical material in language, whether diachronically or synchronically, whether in particular languages or cross-linguistically, and (ii) a term referring to the change whereby lexical items and constructions come in certain linguistic contexts to serve grammatical functions and, once grammaticalized, continue to develop new grammatical functions.

(ii) の意味での文法化について,Hopper and Traugott (231) は,その本質は話し手と聞き手の間における意味の交渉であるとみている.文法化は,このようにコミュニケーションの基本的なポイントに立脚しているがゆえに,語用論的な観点や認知言語学的な観点も含み込むことになり,射程が広いフレームワークということになるのだろう.

We have argued that grammaticalization can be thought of as the result of the continual negotiation of meaning that speakers and hearers engage in in the context of discourse production and perception. The potential for grammaticalization lies in speakers attempting to be maximally informative, and in hearers attempting to be maximally cooperative, depending on the needs of the particular situation. Negotiating meaning may involve innovation, specifically, pragmatic, semantic, and ultimately grammatical enrichment. This means that grammaticalization is conceptualized as a type of change not limited to early child language acquisition or to perception (as is assumed in some models of language change), but due also to adult acquisition and to production.

この射程の広さが,文法化研究の魅力の1つといってよい.

・ Hopper, Paul J. and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. Grammaticalization. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2018-04-07 Sat

■ #3267. 談話標識とその形成経路 [discourse_marker][pragmatics][language_change][terminology][subjectification][intersubjectification][grammaticalisation][historical_pragmatics]

談話標識 (discourse marker, DM) について,「#2041. 談話標識,間投詞,挿入詞」 ([2014-11-28-1]) や discourse_marker の各記事で取り上げてきた.ここでは,種々の先行研究から要点をまとめた Archer に従って,談話標識の特徴と形成経路について紹介する.

まず,談話標識の特徴から.Archer (660) は次の4点を上げている.

- DMs are phonologically short items that normally occur sentence-initially (but can occur in medial or final position . . .);

- DMs are syntactically independent elements (often constituting separate intonation units) which occur with high frequency (in oral discourse in particular);

- DMs lack semantic content (i.e. they are non-referential/non-propositional in meaning)

- DMs are non-truth-conditional elements, and thus optional (i.e. they may be deleted).

たいていの談話標識は,歴史をたどれば,談話標識などではなかった.歴史の過程で,ある表現が談話標識らしくなってきたということである.では,どのような表現が談話標識へと発展しやすいのだろうか.典型的な談話標識の形成経路については,統語的な観点から記述したものと,意味論的な観点のものがある.まず,前者について (Archer 661) .

- adverb/preposition > conjunction > DM;

- predicate adverb > sentential adverb structure > parenthetical DM . . .;

- imperative matrix clause > indeterminate structure > parenthetical DM;

- relative/adverbial clause > parenthetical DM.

意味論的な観点からの経路は,次の通り (Archer 661) .

- truth-conditional > non-truth conditional . . .,

- content > procedural, and nonsubjective > subjective > intersubjective meaning,

- scope within the proposition > scope over the proposition > scope over discourse.

・ Archer, Dawn. "Early Modern English: Pragmatics and Discourse" Chapter 41 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 652--67.

2018-04-02 Mon

■ #3262. 後期中英語の標準化における "intensive elaboration" [lme][standardisation][latin][french][register][terminology][lexicology][loan_word][lexical_stratification]

「#2742. Haugen の言語標準化の4段階」 ([2016-10-29-1]) や「#2745. Haugen の言語標準化の4段階 (2)」 ([2016-11-01-1]) で紹介した Haugen の言語標準化 (standardisation) のモデルでは,形式 (form) と機能 (function) の対置において標準化がとらえられている.それによると,標準化とは "maximal variation in function" かつ "minimal variation in form" に特徴づけられる現象である.前者は codification (of form),後者は elaboration (of function) に対応すると考えられる.

しかし,"elaboration" という用語は注意が必要である.Haugen が標準化の議論で意図しているのは,様々な使用域 (register) で広く用いることができるという意味での "elaboration of function" のことだが,一方 "elaboration of form" という別の過程も,後期中英語における標準化と深く関連するからだ.混乱を避けるために,Haugen が使った意味での "elaboration of function" を "extensive elaboration" と呼び,"elaboration of form" のほうを "intensive elaboration" と呼んでもいいだろう (Schaefer 209) .

では,"intensive elaboration" あるいは "elaboration of form" とは何を指すのか.Schaefer (209) によれば,この過程においては "the range of the native linguistic inventory is increased by new forms adding further 'variability and expressiveness'" だという.中英語の後半までは,書き言葉の標準語といえば,英語の何らかの方言ではなく,むしろラテン語やフランス語という外国語だった.後期にかけて英語が復権してくると,英語がそれらの外国語に代わって標準語の地位に就くことになったが,その際に先輩標準語たるラテン語やフランス語から大量の語彙を受け継いだ.英語は本来語彙も多く保ったままに,そこに上乗せして,フランス語の語彙とラテン語の語彙を取り入れ,全体として序列をなす三層構造の語彙を獲得するに至った(この事情については,「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]) や「#2977. 連載第6回「なぜ英語語彙に3層構造があるのか? --- ルネサンス期のラテン語かぶれとインク壺語論争」」 ([2017-06-21-1]) の記事を参照).借用語彙が大量に入り込み,書き言葉上,英語の語彙が序列化され再編成されたとなれば,これは言語標準化を特徴づける "minimal variation in form" というよりは,むしろ "maximal variation in form" へ向かっているような印象すら与える.この種の variation あるいは variability の増加を指して,"intensive elaboration" あるいは "elaboration of form" と呼ぶのである.

つまり,言語標準化には形式上の変異が小さくなる側面もあれば,異なる次元で,形式上の変異が大きくなる側面もありうるということである.この一見矛盾するような標準化のあり方を,Schaefer (220) は次のようにまとめている.

While such standardizing developments reduced variation, the extensive elaboration to achieve a "maximal variation in function" demanded increased variation, or rather variability. This type of standardization, and hence norm-compliance, aimed at the discourse-traditional norms already available in the literary languages French and Latin. Late Middle English was thus re-established in writing with the help of both Latin and French norms rather than merely substituting for these literary languages.

・ Schaefer Ursula. "Standardization." Chapter 11 of The History of English. Vol. 3. Ed. Laurel J. Brinton and Alexander Bergs. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2017. 205--23.

2018-03-17 Sat

■ #3246. 制限コードと精密コード [sociolinguistics][terminology][context][style]

標題は,現在でも社会言語学においてたまに出会う用語・概念である.制限コード (restricted code) と洗練コード (elaborated code) は,対立する2つの言語使用形態を表わす.制限コードは,比較的少ない語彙や単純な文法構造を用いた,文脈依存性の高い言葉遣いである.一方,精密コードは,豊富な語彙と洗練された文法構造を用いた,文脈依存性の低い言葉遣いである.極端ではあるが,子供の用いるインフォーマルな話し言葉と,大人の用いるフォーマルな書き言葉の対立をイメージすればよい.

この用語がある種の問題を帯びたのは,用語の導入者であるイギリスの社会言語学者 Basil Bernstein が,異なる階級の子供たちの言葉遣いを区別するのにそれを用いたからである.中流階級の子供は両コードを使えるが,労働者階級の子供は制限コードしか使えないという点を巡って,それが各階級の言語習慣の問題なのか,あるいは知性そのものの問題なのかという議論が持ち上がり,教育上の論争に発展した.現在では知性とは関係ないとされているものの,用語のインパクトは強く,いまなお健在である.

Crystal の用語集より,"restricted" と "elaborated" の説明をみておこう.

restricted (adj.) A term used by British sociologist Basil Bernstein (1924--2000) to refer to one of two varieties (or codes) of language use, introduced as part of a general theory of the nature of social systems and social roles, the other being elaborated. Restricted code was thought to be used in relatively informal situations, stressing the speaker's membership of a group, was very reliant on context for its meaningfulness (e.g. there would be several shared expectations and assumptions between the speakers), and lacked stylistic range. Linguistically, it was highly predictable, with a relatively high proportion of such features as pronouns, tag questions, and use of gestures and intonation to convey meaning. Elaborated code, by contrast, was thought to lack these features. The correlation of restricted code with certain types of social-class background, and its role in educational settings (e.g. whether children used to this code will succeed in schools where elaborated code is the norm --- and what should be done in such cases), brought this theory considerable publicity and controversy, and the distinction has since been reinterpreted in various ways.

elaborated (adj.) A term used by the sociologist Basil Bernstein (1924--2000) to refer to one of two varieties (or codes) of language use, introduced as part of a general theory of the nature of social systems and social rules, the other being restricted. Elaborated code was said to be used in relatively formal, educated situations; not to be reliant for its meaningfulness on extralinguistic context (such as gestures or shared beliefs); and to permit speakers to be individually creative in their expression, and to use a range of linguistic alternatives. It was said to be characterized linguistically by a relatively high proportion of such features as subordinate clauses, adjectives, the pronoun I and passives. Restricted code, by contrast, was said to lack these features. The correlation of elaborated code with certain types of social-class background, and its role in educational settings (e.g. whether children used to a restricted code will succeed in schools where elaborated code is the norm --- and what should be done in such cases), brought this theory considerable publicity and controversy, and the distinction has since been reinterpreted in various ways.

英語史上,制限コードに関連して取り上げられ得る話題は,「#3043. 後期近代英語期の識字率」 ([2017-08-26-1]) で見たような識字率の問題だろう.両コードの区別を念頭に,書き言葉というメディアと識字教育の歴史を再検討してみるとおもしろいかもしれない.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2018-03-16 Fri

■ #3245. idiolect [terminology][idiolect][history_of_linguistics][saussure]

同一の方言に属する個人の間でも,細かくみれば発音,文法,語彙などの点で個人的な差が見られ,全く同じ言葉遣いをする人は二人といない.この事実に鑑みて,idiolect 「個人(言)語」というものを考えることができる.新英語学辞典の "idiolect" の項には次のようにある.

Bloc (1948) が初めて用いた術語で,1個人のある1時期における発話の総体を指す.それは発音・文法・語彙の全体にわたり,個人的な癖まで含む.

「個人言語」の概念の発展はアメリカの構造言語学の考えかたと強く結び付いている.すなわち,言語の構造性を明らかにするためには資料をできるだけ等質的にすべきだと考え,異なった方言,同一方言の異なった時代の資料の混同を厳に戒め,最も等質的な資料として個人言語にたどりついた.また言語研究は,どのみち具体的な個人言語を出発点とせざるをえないのであるという理解も大きな支えとなっている.〔中略〕

同一の地域的あるいは社会的方言に属する個人間の個人言語の差異の現われ方は言語の部分によっていろいろである.音韻体系では差異が最も少なく,文法体系がそれに次ぐ.語彙体系では差が最も激しい.常連の連語,つまり「ことば癖」の面にも大きい個人差が見られる.

言語学者がラングという社会に共通の構造体を追い求めながらも,idiolect という極めて個人的な地点に行き着いてしまったというくだりは,Labov のいう "Saussurean Paradox" を指している(「#2202. langue と parole の対比」 ([2015-05-08-1]) も参照).

また,引用の最後の段落で個人間の idiolect の差異が話題となっているが,ある1人の話者の idiolect 内部を考えても,はたして本当に等質的なのだろうかという疑問が生じる.たとえば,個人が標準語と非標準語など複数の変種を操れる場合,すなわち linguistic repertoire をもっている場合には,その話者は複数の idiolects をもっていることになり,それは社会言語学的な異質性を示しているにほかならない.ただし,repertoire を構成する一つひとつを仮に style と呼んでおくとすれば,各 style を指して idiolect とみなすやり方はあるだろう.

いずれにせよ「等質的な idiolect」もまた,言語学の作業のために必要とされるフィクションと考えておくのがよさそうだ.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄 監修 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1987年.

・ Block, B. "A Set of Postulates for Phonetic Analysis." Language 24 (1948): 3--46.

2018-03-09 Fri

■ #3238. 言語交替 [language_shift][language_death][bilingualism][diglossia][terminology][sociolinguistics][irish][terminology]

本ブログでは,言語交替 (language_shift) の話題を何度か取り上げてきたが,今回は原点に戻って定義を考えてみよう.Trudgill と Crystal の用語集によれば,それぞれ次のようにある.

language shift The opposite of language maintenance. The process whereby a community (often a linguistic minority) gradually abandons its original language and, via a (sometimes lengthy) stage of bilingualism, shifts to another language. For example, between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries, Ireland shifted from being almost entirely Irish-speaking to being almost entirely English-speaking. Shift most often takes place gradually, and domain by domain, with the original language being retained longest in informal family-type contexts. The ultimate end-point of language shift is language death. The process of language shift may be accompanied by certain interesting linguistic developments such as reduction and simplification. (Trudgill)

language shift A term used in sociolinguistics to refer to the gradual or sudden move from the use of one language to another, either by an individual or by a group. It is particularly found among second- and third-generation immigrants, who often lose their attachment to their ancestral language, faced with the pressure to communicate in the language of the host country. Language shift may also be actively encouraged by the government policy of the host country. (Crystal)

言語交替は個人や集団に突然起こることもあるが,近代アイルランドの例で示されているとおり,数世代をかけて,ある程度ゆっくりと進むことが多い.関連して,言語交替はしばしば bilingualism の段階を経由するともあるが,ときにそれが制度化して diglossia の状態を生み出す場合もあることに触れておこう.

また,言語交替は移民の間で生じやすいことも触れられているが,敷衍して言えば,人々が移動するところに言語交替は起こりやすいということだろう(「#3065. 都市化,疫病,言語交替」 ([2017-09-17-1])).

アイルランドで歴史的に起こった(あるいは今も続いている)言語交替については,「#2798. 嶋田 珠巳 『英語という選択 アイルランドの今』 岩波書店,2016年.」 ([2016-12-24-1]),「#1715. Ireland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-06-1]),「#2803. アイルランド語の話者人口と使用地域」 ([2016-12-29-1]),「#2804. アイルランドにみえる母語と母国語のねじれ現象」 ([2016-12-30-1]) を参照.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2018-03-09 Fri

■ #3238. 言語交替 [language_shift][language_death][bilingualism][diglossia][terminology][sociolinguistics][irish][terminology]

本ブログでは,言語交替 (language_shift) の話題を何度か取り上げてきたが,今回は原点に戻って定義を考えてみよう.Trudgill と Crystal の用語集によれば,それぞれ次のようにある.

language shift The opposite of language maintenance. The process whereby a community (often a linguistic minority) gradually abandons its original language and, via a (sometimes lengthy) stage of bilingualism, shifts to another language. For example, between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries, Ireland shifted from being almost entirely Irish-speaking to being almost entirely English-speaking. Shift most often takes place gradually, and domain by domain, with the original language being retained longest in informal family-type contexts. The ultimate end-point of language shift is language death. The process of language shift may be accompanied by certain interesting linguistic developments such as reduction and simplification. (Trudgill)

language shift A term used in sociolinguistics to refer to the gradual or sudden move from the use of one language to another, either by an individual or by a group. It is particularly found among second- and third-generation immigrants, who often lose their attachment to their ancestral language, faced with the pressure to communicate in the language of the host country. Language shift may also be actively encouraged by the government policy of the host country. (Crystal)

言語交替は個人や集団に突然起こることもあるが,近代アイルランドの例で示されているとおり,数世代をかけて,ある程度ゆっくりと進むことが多い.関連して,言語交替はしばしば bilingualism の段階を経由するともあるが,ときにそれが制度化して diglossia の状態を生み出す場合もあることに触れておこう.

また,言語交替は移民の間で生じやすいことも触れられているが,敷衍して言えば,人々が移動するところに言語交替は起こりやすいということだろう(「#3065. 都市化,疫病,言語交替」 ([2017-09-17-1])).

アイルランドで歴史的に起こった(あるいは今も続いている)言語交替については,「#2798. 嶋田 珠巳 『英語という選択 アイルランドの今』 岩波書店,2016年.」 ([2016-12-24-1]),「#1715. Ireland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-06-1]),「#2803. アイルランド語の話者人口と使用地域」 ([2016-12-29-1]),「#2804. アイルランドにみえる母語と母国語のねじれ現象」 ([2016-12-30-1]) を参照.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2018-03-08 Thu

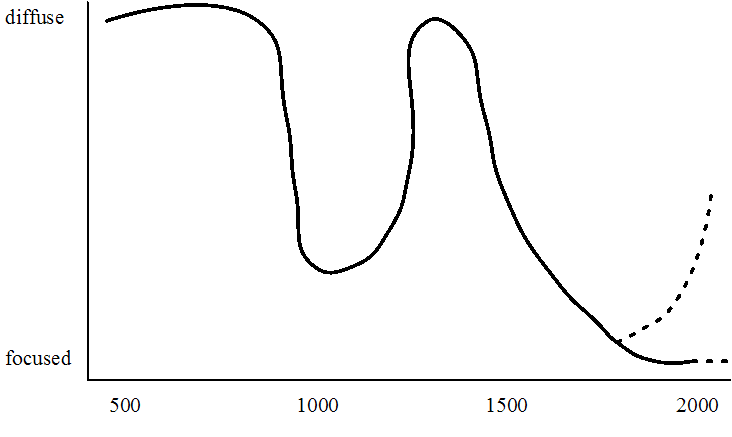

■ #3237. 標準化サイクル [terminology][standardisation][historiography]

ある言語が歴史的に標準化と非標準化を繰り返す現象を,標準化サイクル (standardisation cycle) と呼ぶ.「#3207. 標準英語と言語の標準化に関するいくつかの術語」 ([2018-02-06-1]) で紹介した術語を用いれば,言語(共同体)は focused と diffuse の両極を行ったり来たりするということになる.

Swann et al. の社会言語学辞典によると,次のようにある.

standardisation cycle According to Greenberg (1986) and Ferguson (1988), a regular historical process by which an originally relatively uniform language splits into several dialects; then at a later stage a common, uniform standard is established on the basis of these dialects. Finally, this variety will again split into regional and social varieties and the cycle will start again.

確かに,この観点から英語史を振り返ると,振幅や周波数の変異こそあれ,focused と diffuse の間を行き来している波を認めることができる.「#3231. 標準語に軸足をおいた Blake の英語史時代区分」 ([2018-03-02-1]) の7区分を粗略にグラフ化すると,次のようになるのではないか.

1000年前後にある谷は,英語史上最初の標準語 Late West Saxon の確立を指す.ただし,確立とはいっても完全なる "focused" の状態には到達しておらず,ある程度の変異を許容する緩い標準である.その後,再び中英語の "diffuse" な状態へ回帰するが,15世紀頃からゆっくりと現代の標準語につらなる潮流が始まっている.この英語史上2度目の標準化は,1度目よりも "focused" の程度が著しく,ほぼ "fixed" というべきものであることに注意したい.しかし,一方で後期近代以降,英語が分裂・拡散しているのも事実であり,それもグラフに描き込むのであれば,破線のようになるかもしれない.とすれば,focused から diffuse へのサイクルが再び始動しているように見えてくる.

・ Swann, Joan, Ana Deumert, Theresa Lillis, and Rajend Mesthrie, eds. A Dictionary of Sociolinguistics. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 2004.

・ Greenberg, J. H. "Were There Egyptian Koines?" The Fergusonian Impact. Vol. 1. Ed. A. Fishman, A. Tabouret-Kellter, M. Clyne, B. Krishnamurti and M. Abdulaziz. Berlin and New York: Academic P, 1986.

・ Ferguson, C. A. "Standardization as a Form of Language Spread." Language Spread and Language Policy: Issues, Implications, and Case Studies. Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics, 1987. Ed. P. Lowenberg. Washington, DC: Georgetown UP, 1988.

・ Blake, N. F. A History of the English Language. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1996.

2018-03-06 Tue

■ #3235. 標準語イデオロギー,標準化イデオロギー [linguistic_ideology][standardisation][language_myth][terminology]

標準語イデオロギー (standard language ideology) とは,Swann et al. の社会言語学辞典によると以下の通りである.

standard language ideology A concept introduced to sociolinguistics by James Milroy and Lesley Milroy (1999) in order to describe the prescriptive attitudes that accompany the emergence of standard languages. Standard Language Ideologies (SLIs) are characterised by a metalinguistically articulated and culturally dominant belief that there is only one correct way of speaking (i.e. the standard language). The SLI leads to a general intolerance towards linguistic variation, and non-standard varieties in particular are regarded as 'undesirable' and 'deviant'.

ここで参照されている Milroy and Milroy に,第4版(2012年)で当たってみると,p. 19 に関連する記述がある.

. . . it seems appropriate to speak more abstractly of standardisation as an ideology, and a standard language as an idea in the mind rather than a reality --- a set of abstract norms to which actual usage conform to a greater or lesser extent.

標準○○語というものが抽象物であることは,「#3232. 理想化された抽象的な変種としての標準○○語」 ([2018-03-03-1]) でも Milroy and Milroy を通じて確認した.そのような変種が存在すると信じることは,1つのイデオロギーであるということだ.これが「標準語イデオロギー」である.

さらに進めていえば,言語の標準化 (standardisation) という過程自体も実体としての過程というよりも,言語観察者の頭の中にあるイデオロギーにすぎないというべきだろう.こちらは「標準化イデオロギー」と呼んでよい.

「○○語史における標準化の形成と発展」というようなテーマを扱う場合には,そのテーマの立て方自体に1つの言語イデオロギーが宿っている点に注意すべきだろう.私もこれまで英語の標準化の歴史を素朴な疑問として追求してきたが,標準化を論じる際には,その前提にあるイデオロギー性に自覚的でなければならないと反省している.

・ Swann, Joan, Ana Deumert, Theresa Lillis, and Rajend Mesthrie, eds. A Dictionary of Sociolinguistics. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 2004.

・ Milroy, Lesley and James Milroy. Authority in Language: Investigating Language Prescription and Standardisation. 4th ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2012.

2018-02-08 Thu

■ #3209. 言語標準化の7つの側面 [standardisation][sociolinguistics][terminology][language_planning][reestablishment_of_english][spelling_reform][genbunicchi]

言語の標準化の問題を考えるに当たって,1つ枠組みを紹介しておきたい.Milroy and Milroy (27) にとって,standardisation とは言語において任意の変異可能性が抑制されることにほかならず,その過程には7つの段階が認められるという.selection, acceptance, diffusion, maintenance, elaboration of function, codification, prescription である.これは古典的な「#2745. Haugen の言語標準化の4段階 (2)」 ([2016-11-01-1]) に基づいて,さらに精密化したものとみることができる.Haugen は,selection, codification, elaboration, acceptance の4段階を区別していた.

Milroy and Milroy の7段階という枠組みを用いて標準英語の形成を歴史的に分析・解説したものとしては,Nevalainen and Tieken-Boon van Ostade の論考が優れている.そこではもっぱら現代標準英語の発達の歴史が扱われているが,同じ方法で英語史における大小様々な「標準化」を切ることができるだろうと述べている.かぎ括弧つきの「標準化」は,何らかの意味で個人や集団による人為的な要素が認められる言語改革風の営みを指している.具体的には,10世紀のアルフレッド大王による土着語たる古英語の公的な採用(ラテン語に代わって)や,Chaucer 以降の書き言葉としての英語の採用(フランス語やラテン語に代わって)や,12世紀末の Orm の綴字改革や,19世紀の William Barnes による母方言たる Dorset dialect を重用する試みや,アメリカ独立革命期以降の Noah Webster による「アメリカ語」普及の努力などを含む (Nevalainen and Tieken-Boon van Ostade 273) .互いに質や規模は異なるものの,これらのちょっとした言語計画 (language_planning) というべきものを,「標準化」の試みの事例として Milroy and Milroy 流の枠組みで切ってしまおうという発想は,斬新である.

日本語史でいえば,現代標準語の形成という中心的な話題のみならず,仮名遣いの変遷,言文一致運動,常用漢字問題,ローマ字問題などの様々な事例も,広い意味での標準化の問題としてカテゴライズされ得るということになろう.

・ Milroy, Lesley and James Milroy. Authority in Language: Investigating Language Prescription and Standardisation. 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge, 1991.

・ Nevalainen, Terttu and Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade. "Standardisation." Chapter 5 of A History of the English Language. Ed. Richard Hogg and David Denison. Cambridge: CUP, 2006. 271--311.

2018-02-06 Tue

■ #3207. 標準英語と言語の標準化に関するいくつかの術語 [terminology][sociolinguistics][standardisation][koine][dialect_levelling][language_planning][variety]

このところ,英語の標準化 (standardisation) の歴史のみならず,言語の標準化について一般的に考える機会を多くもっている.この問題に関連する術語と概念を整理しようと,社会言語学の用語集 (Trudgill) を開いてみた.そこから集めたいくつかの術語とその定義・説明を,備忘のために記しておきたい.

まずは,英語に関してずばり "Standard English" という用語から(「#1396. "Standard English" とは何か」 ([2013-02-21-1]),「#2116. 「英語」の虚構性と曖昧性」 ([2015-02-11-1]) も参照).

Standard English The dialect of English which is normally used in writing, is spoken by educated native speakers, and is taught to non-native speakers studying the language. There is no single accent associated with this dialect, but the lexicon and grammar of the dialect have been subject to codification in numerous dictionaries and grammars of the English language. Standard English is a polycentric standard variety, with English, Scottish, American, Australian and other standard varieties differing somewhat from one another. All other dialects can be referred to collectively as nonstandard English.

ここで使われている "polycentric" という用語については,「#2384. polycentric language」 ([2015-11-06-1]) と「#2402. polycentric language (2)」 ([2015-11-24-1]) も参照.

次に,"standardisation" という用語から芋づる式にいくつかの用語をたどってみた.

standardisation The process by which a particular variety of a language is subject to language determination, codification and stabilisation. These processes, which lead to the development of a standard language, may be the result of deliberate language planning activities, as with the standardisation of Indonesia, or not, as with the standardisation of English.

status planning [≒language determination] In language planning, status planning refers to decisions which have to be taken concerning the selection of particular languages or varieties of language for particular purposes in the society or nation in question. Decisions about which language or languages are to be the national or official languages of particular nation-states are among the more important of status planning issues. Status planning is often contrasted with corpus planning or language development. In the use of most writers, status planning is not significantly different from language determination.

codification The process whereby a variety of a language, often as part of a standardisation process, acquires a publicly recognised and fixed form in which norms are laid down for 'correct' usage as far as grammar, vocabulary, spelling and perhaps pronunciation are concerned. This codification can take place over time without involvement of official bodies, as happened with Standard English, or it can take place quite rapidly, as a result of conscious decisions by governmental or other official planning agencies, as happened with Swahili in Tanzania. The results of codification are usually enshrined in dictionaries and grammar books, as well as, sometimes, in government publications.

stabilisation A process whereby a formerly diffuse language variety that has been in a state of flux undergoes focusing . . . and takes on a more fixed and stable form that is shared by all its speakers. Pidginised jargons become pidgins through the process of stabilisation. Dialect mixtures may become koinés as a result of stabilisation. Stabilisation is also a component of language standardisation.

focused According to a typology of language varieties developed by the British sociolinguist Robert B. LePage, some language communities and thus language varieties are relatively more diffuse, while others are relatively more focused. Any speech act performed by an individual constitutes an act of identity. If only a narrow range of identities is available for enactment in a speech community, that community can be regarded as focused. Focused linguistic communities tend to be those where considerable standardisation and codification have taken place, where there is a high degree of agreement about norms of usage, where speakers tend to show concern for 'purity' and marking their language variety off from other varieties, and where everyone agrees about what the language is called. European language communities tend to be heavily focused. LePage points out that notions such as admixture, code-mixing, code-switching, semilingualism and multilingualism depend on a focused-language-centred point of view of the separate status of language varieties.

diffuse According to a typology of language varieties developed by the British sociolinguist Robert B. LePage, a characteristic of certain language communities, and thus language varieties. Some communities are relatively more diffuse, while others are relatively more focused. Any speech act performed by an individual constitutes an act of identity. If a wide range of identities is available for enactment in a speech community, that community can be regarded as diffuse. Diffuse linguistic communities tend to be those where little standardisation or codification have taken place, where there is relatively little agreement about norms of usage, where speakers show little concern for marking off their language variety from other varieties, and where they may accord relatively little importance even to what their language is called.

最後に挙げた2つ "focused" と "diffuse" は言語共同体や言語変種について用いられる対義の形容詞で,実に便利な概念だと感心した.光の反射の比喩だろうか,集中と散乱という直感的な表現で,標準化の程度の高低を指している.英語史の文脈でいえば,中英語は a diffuse variety であり,(近)現代英語や後期古英語は focused varieties であると概ね表現できる."focused" のなかでも程度があり,程度の高いものを "fixed",低いものを狭い意味での "focused" とするならば,(近)現代英語は前者,後期古英語は後者と表現できるだろう.fixed と focused の区別については,「#929. 中英語後期,イングランド中部方言が標準語の基盤となった理由」 ([2011-11-12-1]) も参照.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2018-01-09 Tue

■ #3179. 「新古典主義的複合語」か「英製羅語」か [neo-latin][latin][greek][word_formation][lexicology][loan_word][compounding][derivation][lmode][scientific_english][scientific_name][neologism][waseieigo][terminology][register]

新古典主義的複合語 (neoclassical compounds) とは,aerobiosis, biomorphism, cryogen, nematocide, ophthalmopathy, plasmocyte, proctoscope, rheophyte, technocracy のような語(しばしば科学用語)を指す.Durkin (346--37) によれば,この類いの語彙は早くは1600年前後から確認され,例えば polycracy (1581), pantometer (1597), multinomial (1608) がみられる.しかし,爆発的に量産されるようになったのは,科学が急速に発展した後期近代英語期,とりわけ19世紀になってからのことである(「#616. 近代英語期の科学語彙の爆発」 ([2011-01-03-1]),「#3013. 19世紀に非難された新古典主義的複合語」 ([2017-07-27-1]),「#3014. 英語史におけるギリシア語の真の存在感は19世紀から」 ([2017-07-28-1]),「#3166. 英製希羅語としての科学用語」 ([2017-12-27-1]) を参照).

新古典主義的複合語について強調しておくべきは,それが借用語ではなく,あくまで英語(を始めとするヨーロッパの諸言語)において形成された語であるという点だ.確かにラテン語やギリシア語などの古典語をモデルとしてはいるが,決してそこから借用されたわけではない.その意味では英単語ぽい体裁をしていながらも英単語ではない「和製英語」と比較することができる.新古典主義的複合語の舞台は英語であるから,つまり「英製羅語」といってよい.しかし,英製羅語と和製英語とのきわだった相違点は,前者が主として国際的で科学的な文脈で用いられるが,後者はそうではないという事実にある.すなわち,両者のあいだには使用域において著しい偏向がみられる.Durkin は,新古典主義的複合語について次のように述べている.

. . . these formations typically belong to the international language of science and move freely, often with little or no morphological adaptation, between English, French, German, and other languages of scientific discourse. They are often treated in very different ways in different traditions of lexicography and lexicology; however, those terms that are coined in modern vernacular languages are certainly not loanwords from Latin or Greek, even though they may be formed from elements that originated in such loanwords. (347)

. . . Latin words and word elements have become ubiquitous in modern technical discourse, but frequently in new compound or derivative formations or with new meanings that have seldom if ever been employed in contextual use in actual Latin sentences. (349)

これらの造語を指して「新古典主義的複合語」と呼ぶか「英製羅語」と呼ぶかは,たいした問題ではない.しかし,和製英語の場合には「英語主義的複合語」と呼ばないのはなぜだろうか.この違いは何に起因するのだろうか.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow