2025-03-10 Mon

■ #5796. ghost word を OED で引いてみた [lexicography][word_formation][folk_etymology][ghost_word][terminology]

昨日の記事「#5795. ghost word 再訪」 ([2025-03-09-1]) で取り上げた興味深い語彙的現象について,もう少し追いかけたい.OED に ghost word (NOUN) が立項されているので引用しよう.

A word or word form that has come into existence by error rather than established usage, e.g. as a result of a typographical error, the incorrect transcription of a manuscript, an incorrect definition in a dictionary, etc.

1887 Report upon 'Ghost-words', or Words which have no real Existence... We should jealously guard against all chances of giving any undeserved record of words which had never any real existence, being mere coinages due to the blunders of printers or scribes, or to the perfervid imaginations of ignorant or blundering editors. (W. W. Skeat in Transactions of Philological Society 1885--7 vol. 20 350)

1888 The word meant is estures, bad spelling of estres; and eftures is a ghost-word. (W. W. Skeat in Notes & Queries 30 June 504/1)

1977 He [sc. Murray] found a special class of ‘ghost words’, misspelled or ill-defined items that had been admitted to some previous dictionary, thus undergoing an illegitimate birth. (Time 26 December 54/2)

2019 The project will uncover previously unrecorded words, excise ghost words and suggest new or revised definitions. (TendersInfo (Nexis) 21 May)

ghost word の栄えある初例は1887年の Skeat のもので,これは「#2725. ghost word」 ([2016-10-12-1]) でも引用した通りである.いずれにしても緩い定義なので緩く付き合っていくのがよさそうな用語だが,あまりに魅力的な響きで気になってしまうのは仕方ないのだろうか.このように緩くとった「幽霊語」は,少なくとも英語において(そして推測するに日本語など他の言語においても)思いのほか多いのではないだろうか.

2025-03-09 Sun

■ #5795. ghost word 再訪 [lexicography][word_formation][folk_etymology][ghost_word][terminology]

「#2725. ghost word」 ([2016-10-12-1]) や「#912. 語の定義がなぜ難しいか (3)」 ([2011-10-26-1]) で,この用語に触れてきた.今回は『新英語学辞典』の解説を読んでみよう.

ghost word〔言〕(幽霊語)

Skeat (TPS, 1885--87, II. 350--51) の用語 (OED, s.v. ghost).誤植,書写の誤り,編集者・表現者の思い違いから生じた語で,本来はあるべからざる語のこと.そのありうべからざる語が現実に現われた場合,この語を幽霊語または幽霊形 (ghost form) という.つまり,語源的には不要な字が入るなどして,あるべからざる語形をとっている語(例:aghast, sprightly, island, ye (= the)) も幽霊語であるが,誤解から,本来はないはずの意味を与えられた語も幽霊語である.1) acre (= duel). 'fight an acre' のことを「(イングランドとスコットランド辺境地区で)決闘をする」という意味に解し,acre に duel の意味を与えること.本来は中世ラテン語 acram (= duel) committre の英訳の誤りから生じたもの. 2) in derring do (= in daring to do). Chaucer, Troilus and Criseyde 837 から Spenser が誤解して, derring-do を「勇敢な行動」の意味で用いている.3) bourne (= realm). Shakespeare, Hamlet 3:1:79--80 の The undiscovered country, from whose bourne (= limit) No traveller returns から誤解して fiery realm and airy bourne (= realm)--Keats というとき,この bourne は本来なかった意味で用いられていることになる(Bloomfield, 1933, p. 487).これもまた幽霊語の一種である.

一言でいえば,諸々の事情で「あるべからざる語」が現に存在するようになったものが ghost word(幽霊語)ということになる.日常用語としてはこれで済むかもしれないが,学術的には「あるべからざる語」の定義が必要だろう.どのような条件が成立すれば「あるべき語」なのか,あるいは「あるべからざる語」なのか.

上記の引用では「誤植,書写の誤り,編集者・表現者の思い違い」の3点が挙げられているが,これだけで十分なのだろうか.また,真に「誤り」や「思い違い」が関わっているのどうかを歴史的に確かめることは,どこまで可能なのだろうか.幽霊形,幽霊語義,幽霊綴字などと様々に発展させられそうな概念なだけに,基本的な定義を固めておくことが重要のように考える.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2025-03-08 Sat

■ #5794. 英文法用語としての準動詞 [verb][verbid][participle][gerund][infinitive][terminology][sobokunagimon][jespersen][voicy][heldio][pos]

昨日と今朝の heldio にて,「#1377. 思い出の英文法用語 --- リスナーの皆さんからお寄せいただきました(前半)」と「#1378. 思い出の英文法用語 --- リスナーの皆さんからお寄せいただきました(後半)」を配信しました.これは,2月24日にリスナー参加型企画として公開した「#1366. あなたの思い出の英文法用語を教えてください」のフォローアップ回でした.heldio リスナーの皆さんには,多くのコメントを寄せていただきましてありがとうございました.

英文法用語といってもピンからキリまであります.基本的な用語から言語学の術語というべきものまで多々あります.レベルを気にせずに,とにかく思い出の/気になる/推しの/嫌いな用語を挙げてくださいという趣旨で,コメントを募りました.その結果を読み上げたのが,上掲の2つの配信回です.

そのなかで準動詞という用語が何度か言及されていました.英語では verbal や verbid と呼ばれますが,これはいったい何のことでしょうか.『新英語学辞典』の verbal を引いてみると,(1) として「準動詞」の解説があります.

(1) (準動詞) 不定詞 (infinitive),分詞 (participle),動名詞 (gerund) の総称.verbid ともいう.また非定形 (non-finite form),不定形 (infinite form),非定形動詞 (non-finite verb) ともいう.なお,準動詞が名詞的に用いられたものを名詞的準動詞 (noun verbal) または動詞的名詞 (verbal noun) といい,形容詞的用法のものを形容詞的準動詞 (adjective verbal) または動詞的形容詞 (verbal adjective) ということがある.I'm thinking of going./I wish to go. 〔名詞的準動詞〕//melting snow 〔形容詞的準動詞〕.

言い換え表現や,さらに細かい区分の用語もあり,ややこしいですね.次に,OED の verbid (NOUN) を引いてみましょう.

Grammar. Somewhat rare.

A word, such as an infinitive, gerund, or participle, which has some characteristics of a verb but cannot form the head of a predicate on its own. Also: (with reference to certain West African languages) a bound verb with in a serial verb construction.

1914 We shall..restrict the name of verb to those forms that have the eminently verbal power of forming sentences, and..apply the name of verbid to participles and infinitives. (O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar vol. II. 7)

. . . .

OED での初例から,これが Jespersen の造語であることを初めて知りました.「#5782. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に形態を基準にして分類するとどうなるか」 ([2025-02-24-1]) で紹介した Jespersen の品詞論との関連からも,興味深い事実です.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2025-03-05 Wed

■ #5791. "word class" (語類)は OED によると1882年初出 [oed][pos][terminology][linguistics][category][morphology][inflection][word_class][loan_translation][german]

昨日の記事「#5790. 品詞とは何か? --- OED の "part of speech" を読む」 ([2025-03-04-1]) などで触れてきたが,品詞 (pos) と重なりつつも,もっと緩い括りである語類 (word_class) について OED を引いてみた.

A category of words of similar form or syntactic characteristics; esp. a part of speech.

1882 A root is an abstraction of all word-classes and their differences. (E. Channing, translation of A. F. Pott in translation of B. Delbrück, Introd. Study Language v. 74.

1914 Other word classes which are not expressed by formational similarity. (L. Bloomfield, Introduction to Study of Language iv. 109)

1924 We have a great many words which can belong to one word-class only: admiration, society, life can only be substantives [etc.]. (O. Jespersen, Philosophy of Grammar iv. 61)

1953 The so-called parts of speech (still more inappropriately word-classes) are classes of stem-morpheme. (C. E. Bazell, Linguistic Form vi. 76)

1998 All of the general properties shared by whole word classes..are assumed to be within the competence of the grammar rather than of the lexicon. (Euralex '98 Proceedings vol. I. ii. 261)

初出は1882年で,歴史的には新しい.語源欄にはドイツ語 Wortklasse (1817) のなぞりとの示唆もある.

狭い意味では品詞と同様に用いることができるものの,語類は単語はをいかようにでも分類でき,随意の分類について語ることができるために,言語学的にはきわめて有用な用語である.

2025-03-04 Tue

■ #5790. 品詞とは何か? --- OED の "part of speech" を読む [oed][pos][terminology][linguistics][category][morphology][inflection][loan_translation][latin][oe][aelfric]

英語で「品詞」を表わす語句 part of speech (pos) は,どのように定義されているのか,そしていつ初出したのか.OED では part (NOUN1) の I.1.c. に part of speech が立項されている.それを引用しよう.

I.1.c. part of speech noun

Each of the categories to which words are traditionally assigned according to their grammatical and semantic functions. Cf. part of reason n. at sense I.1b.

In English there are traditionally considered to be eight parts of speech, i.e. noun, adjective, pronoun, verb, adverb, preposition, conjunction, interjection; sometimes nine, the article being distinguished from the adjective, or, formerly, the participle often being considered a distinct part of speech. Modern grammars often distinguish lexical and grammatical classes, the lexical including in particular nouns, adjectives, full verbs, and adverbs; the grammatical variously subdivided, often distinguishing classes such as auxiliary verbs, coordinators and subordinators, determiners, numerals, etc. See also word class n.

In quot. c1450 showing similar use of party of speech (compare party n. I).

[c1450 Aduerbe: A party of spech þat ys vndeclynyt, þe wych ys cast to a verbe to declare and fulfyll þe sygnificion [read sygnificacion] of þe verbe. (in D. Thomson, Middle English Grammatical Texts (1984) 6 (Middle English Dictionary))

c1475 How many partes of spech be ther? (in D. Thomson, Middle English Grammatical Texts (1984) 61 (Middle English Dictionary))

1517 For as moche as there be Viii. partes of speche, I wolde knowe ryght fayne What a nowne substantyue, is in his degre. (S. Hawes, Pastime of Pleasure (1928) v. 27)

. . . .

ここでは,品詞が文法的・意味的な機能によって分類されていること,英語では伝統的に8つ(場合によっては9つ)の品詞が認められてきたこと,品詞分類に準じて語類 (word class) という区分法があり語彙的クラスと文法的クラスなどに分けられることなどが記述されている.

最初例の例文は1450年頃からのものとなっているが,そこでは party of spech の語形であることに注意すべきである.さらにそれと関連して party of reason や part of reason という類義語も OED に採録されており,いずれも上に見える1450年頃の同じソース D. Thomson, Middle English Grammatical Texts より例文がとられていることも指摘しておこう.

また,part 単体として「品詞」を意味する用法があり,ラテン語表現のなぞりという色彩が濃いが,なんと早くも古英語期に文証されている(Ælfric の文法書).

OE Þry eacan synd met, pte, ce, þe man eacnað on ledenspræce to sumum casum þises partes. (Ælfric, Grammar (St. John's Oxford MS.) 107)

OE Þes part mæg beon gehaten dælnimend. (Ælfric, Grammar (St. John's Oxford MS.) 242)

part of speech という英語の語句は,古英語期に確認されるラテン文法の伝統的な用語遣いにあやかりつつ,中英語末期に現われ,その後盛んに用いられるようになったタームということになる.

品詞考については pos の関連記事,とりわけ以下の記事群を参照.

・ 「#5762. 品詞とは何か? --- 日本語の「品詞」を辞典・事典で調べる」 ([2025-02-04-1])

・ 「#5763. 品詞とは何か? --- ただの「語類」と呼んではダメか」 ([2025-02-05-1])

・ 「#5765. 品詞とは何か? --- Bloomfield の見解」 ([2025-02-07-1])

・ 「#5771. 品詞とは何か? --- 分類基準の問題」 ([2025-02-13-1])

・ 「#5772. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に意味を基準にした分類は可能か」 ([2025-02-14-1])

・ 「#5773. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に機能を基準にした分類の試み」 ([2025-02-15-1])

・ 「#5782. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に形態を基準にして分類するとどうなるか」 ([2025-02-24-1])

2025-03-02 Sun

■ #5788. 思考と現実 --- 意味論および言語哲学の問題 [thought_and_reality][semantics][philosophy_of_language][terminology]

Saeed の意味論の概説書に "Thought and reality" と題する節がある.これは意味論 (semantics) と言語哲学 (philosophy_of_language) の接点というべき問題だ.英語の原文 (p. 45) を引用しながら,この方面のいくつかの用語を確認しておこう.

We can ask: must we as aspiring semanticists adopt for ourselves a position on traditional questions of ontology, the branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of being and the structure of reality, and epistemology, the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of knowledge? For example, do we believe that reality exists independently of the workings of human minds? If not, we are adherents of idealism. If we do believe in an independent reality, can we perceive the world as it really is? One response is to say yes. We might assert that knowledge of reality is attainable and comes from correctly conceptualizing and categorizing the world. We could call this position objectivism. On the other hand we might believe that we can never perceive the world as it really is: that reality is only graspable through the conceptual filters derived from our biological and cultural evolution. We could explain the fact that we successfully interact with reality (run away from lions, shrink from fire, etc.) because of a notion of ecological viability. Crudely: that those with very inefficient conceptual systems (not afraid of lions or fire) died out and weren't our ancestors. We could call this position mental constructivism: we can't get to a God's eye view of reality because of the way we are made.

意味論,ひいては言語学を学ぶ前提として,思考と現実の関係について言語哲学上の立場が複数あることは知っておきたい.

・ Saeed, John I. Semantics. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.(比較的新しい意味論の概説書です)

2025-02-24 Mon

■ #5782. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に形態を基準にして分類するとどうなるか [pos][terminology][linguistics][category][morphology][inflection]

今月は,品詞をめぐる議論を以下の記事で取り上げてきた.

・ 「#5763. 品詞とは何か? --- ただの「語類」と呼んではダメか」 ([2025-02-05-1])

・ 「#5765. 品詞とは何か? --- Bloomfield の見解」 ([2025-02-07-1])

・ 「#5771. 品詞とは何か? --- 分類基準の問題」 ([2025-02-13-1])

・ 「#5772. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に意味を基準にした分類は可能か」 ([2025-02-14-1])

・ 「#5773. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に機能を基準にした分類の試み」 ([2025-02-15-1])

品詞は,分類基準に何を据えるかで様相が大きく異なってくる.今回は,厳密に形態に基づいて分類するとどうなるかを考えてみたい.参照するのは,引き続き『新英語学辞典』の parts of speech の項である.

形態に基づく分類として最も分かりやすいのは,当該の単語が形態的に変化し得るか,しないかである.ラベルを貼るとすれば「変化詞」と「不変化詞」がふさわしい.

実際 Sweet は,この基準による品詞分類を提案した.それによると,伝統的にいうところの「名詞」「形容詞」「動詞」は,文法機能に応じて何らかの形態変化を示すので「変化詞」となる.一方,「前置詞」「接続詞」「間投詞」は原則として形態変化を示さないので「不変化詞」となる(Sweet ではここに「副詞」も加えられているが,副詞には比較変化があり得ることに注意が必要である).

続いて,Jespersen も形態的な基準により「変化詞」と「不変化詞」に分けた.「変化詞」には従来の「名詞」「形容詞」「代名詞」「動詞」が含まれ,「不変化詞」には従来の「副詞」「前置詞」「接続詞」「間投詞」が含まれる.

ただし,Sweet にせよ Jespersen にせよ,「変化詞」や「不変化詞」の各々の下位区分の基準については触れておらず,結局のところ従来の機能・意味的基準を暗に採用しているではないか,という批判は避けられない.

もちろん「名詞」には名詞独自の,「動詞」には動詞独自の形態変化があるので,その形態的振る舞いを拠り所にして下位区分していくことは可能である.ただし,その場合,例えば名詞と動詞を兼任する love という語の場合,これを同一語と捉えるのか,「文法的同音異義語」として異なる2語と捉えるのかという問題が生じる.この問題は伝統的な品詞分類においても生じており,特別な問題ではないといえばそうなのだが,そもそも品詞分類とは何のためにするはずだったのか,という原初の問題に立ち返る契機を与えてくれはする.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2025-02-22 Sat

■ #5780. 古典語に由来する連結形は日本語の被覆形に似ている [morphology][compound][latin][greek][japanese][word_formation][combining_form][terminology][derivation][affixation][morpheme]

昨日の記事「#5779. 連結形は語に対応する拘束形態素である」 ([2025-02-21-1]) で,連結形 (combining_form) に注目した.今回も引き続き注目していくが,『新英語学辞典』の解説を読んでみよう.

combining form 〔文〕(連結形) 複合語,時に派生語を造るときに用いられる拘束的な異形態をいう.英語の本来語では語基 (BASE) と区別がないが,ギリシア語・ラテン語に由来する形態の場合は連結形が独自に存在するのがふつうである.連結上の特徴から見ると前部連結形(例えば philo-)と後部連結形(例えば -sophy)とに分けることができる.接頭辞,接尾辞のような純粋な拘束形式と異なり,連結形は互いにそれら同士で結合したり,あるいは接辞をとることもできる.

おおよそ昨日の記述と重なるが,「英語の本来語では語基 (BASE) と区別がない」の指摘は比較言語学的にも対照言語学的にも興味深い.英語では,古い段階の古英語ですら,語 (word) の単位がかなり明確で,語とは別に語幹 (stem) や語根 (root) を切り出す共時的な動機づけは比較的弱い.

それに対して,ギリシア語やラテン語などの古典語では,英語に比べて屈折がよく残っており,これを反映して,形態的に独立した語とは異なる非独立的な連結形が存在する.

西洋古典語の連結形と関連して思い出されるのは,古代日本語の非独立形あるいは被覆形と呼ばれる形態だ.「#3390. 日本語の i-mutation というべき母音交替」 ([2018-08-08-1]) で導入した通り,例えば「かぜ」(風)と「かざ」(風見),「ふね」(船)と「ふな」(船乗り),「あめ」(雨)と「あま」(雨ごもり)のように,独立形と,複合語を作る際に用いられる非独立形の2系列があった.歴史的には音韻形態論的な変化の結果,2系列が生じたのだが,西洋古典語の連結形についても同じことがいえるかもしれない.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2025-02-21 Fri

■ #5779. 連結形は語に対応する拘束形態素である [morphology][compound][latin][greek][word_formation][combining_form][terminology][derivation][affixation][morpheme]

接頭辞 (prefix) ぽい,あるいは接尾辞 (suffix) ぽい,それでいてどちらでもないという中途半端な位置づけの形態素 (morpheme) がある.連結形と訳される combining_form である.連結形についての説明や問題点は「#552. combining form」 ([2010-10-31-1]) で触れたとおりだが,『英語学要語辞典』での解説が分かりやすかったので,今回はその項目を引用したい.

combining form 〔言〕(連結形,造語形) 合成語 (COMPOUND) ときに派生語 (DERIVATIVE WORD) の形成に用いられる構成要素をいう.OED で aero- の定義にはじめて用いられたと考えられる.本来はギリシア語・ラテン語系に由来するものが多く,前部連結形(例 philo-)と後部連結形(例 -logy)の2種類がある.連結形は自由形式 (FREE FORM) をなす語 (WORD) の拘束異形態 (bound allomorph) ということができ,本来は独立語として用いられない.しかし,最近では anti (← anti-),graph (← -graph) のような例外的用法も増加している.また,連結形は接頭辞 (PREFIX)・接尾辞 (SUFFIX) に比べて意味が一層具象的であり,連結の関係も通例等位的である.ただし,最近では bio-degradable (= biologically ---) のような例外も認められる.さらに,接頭辞・接尾辞が通例直接互いに連結することがないのに対して,連結形は語や他の連結形のほか,接辞,特に接尾辞と連結することも可能である(例:-morphic (← -morph + -ic),heteroness (← hetero- + -ness)).

「連結形は語に対応する拘束形態素である」という捉え方は,とても分かりやすい.

なお,引用中にある OED への言及についてだが,combining form の項目に初例として以下が掲載されていた.

1884 Gr. ἀερο-, combining form of ἀήρ, ἀέρα

New English Dictionary (OED first edition) at Aero-

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編) 『英語学要語辞典』 研究社,2002年.

2025-02-15 Sat

■ #5773. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に機能を基準にした分類の試み [pos][terminology][linguistics][category][semantics][function_of_language][functionalism][syntax]

昨日の記事「#5772. 品詞とは何か? --- 厳密に意味を基準にした分類は可能か」 ([2025-02-14-1]) で,1つの基準を厳密に適用した場合の品詞論について考え始めた.引き続き『新英語学辞典』の parts of speech の項に依拠しながら,今回は機能のみに基づいた品詞分類を思考実験してみよう.

(3) 機能を基準にした品詞分類. Fries (1952, ch. 6) は品詞を厳密に機能を基準にして分類すべきであると主張し,独自の品詞分類を提案した.語の位置[機能]を基準にして,同一の位置にくる語を一つの語類にまとめた.The concert was good (always). / The clerk remembered the tax (suddenly). / The team went there. の3種の代表的な検出枠 (test frame) を出発点として,文法構造を変えずに,これらの文のどの語の位置にくるかによって,次の4種の類語 (CLASS WORD) --- ほぼ内容語 (CONTENT WORD) に同じ --- を設定し,これらを品詞とした.

第一類語 (class 1 word): concert, clerk, tax, team の位置にくる語

第二類語 (class 2 word): was, remembered, went の位置にくる語

第三類語 (class 3 word): good の位置にくる語

第四類語 (class 4 word): always, suddenly, there の位置にくる語

これ以外は機能語 (FUNCTION WORD) として A から O まで15の群 (group) に分けた.注意すべきは,The poorest are always with us. の poorest は,その形態がどうであろうとその位置から第一類語とするし,また,I know the poorest man. の poorest は,第三類語とするのである.さらに,a boy friend と a good friend の boy も good も同じ第三類語に入れられるのは明らかである.従って a cannon ball の cannon が名詞であるか形容詞であるかの議論も生じてこない.〔もちろんこの場合の cannon は第三類語となる.〕 この分類によれば,一つの語がただ一つの品詞に入れられなくなるのは全くなつのことになり,ある環境にどんな語が現われるかと問われると,名詞とか代名詞とかでなく,1語ずつ現われうるすべての語を答えなければならない.このような分類は方法論の厳密さに価値はあるが,文法体系全体としては余り意味のない場合も生じるかもしれない.

ここまで読むと分かると思うが,「機能」とは「統語的機能」のことである.確かにこれはこれで理論的に一貫している.しかし,実用には供しづらい.『新英語学辞典』の記述の前提には,品詞分類の要諦は実用性にあり,という姿勢があることが確認できる.この点は重要だと思う.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2025-02-14 Fri

■ #5772. 品詞とは何か? --- 意味のみを基準にした厳密な分類は可能か [pos][terminology][linguistics][category][semantics]

標題について「#5763. 品詞とは何か? --- ただの「語類」と呼んではダメか」 ([2025-02-05-1]),「#5765. 品詞とは何か? --- Bloomfield の見解」 ([2025-02-07-1]),「#5771. 品詞とは何か? --- 分類基準の問題」 ([2025-02-13-1]) で議論してきた.

品詞 (parts of speech, or pos) というものを設けると決めた以上,何に基づいて分類するのがベストなのかという問題が生じる(品詞を設ける必要がないというのも1つの立場だが,では言語を何で分けるのがよいのかという別の問いが生じる).昨日の記事では,伝統的な品詞分類が意味,機能,形態の3つの基準の複合に拠っていることを確認した.基準のオーバーラップが問題となるのであれば,いずれか1つに基づいた厳密な理論化こそが目指すべき方向となる.

では,意味(論) (semantics) に基づいた厳密な分類をするとどうなるか.『新英語学辞典』の parts of speech の項では,この試みはうまく行かないだろうと論じられている.以下に引用しよう (p. 837) .

意味,機能,形態の3種の基準のうち,どれを採用してもよいわけであるが,ある一つを基準とした場合,まず,正確に分類できるかどうか,また仮に,分類できたにしても,その分類が文法記述に有効かどうかを考えなければならない.例えば,意味を基準に分類してみると,品詞間の境界を明確に区別することが困難であり,さらにもしあえて分類したとしても,その分類が文法記述には余り有益にはならないであろう.例えば,arrive と arrival を同じ品詞に入れたとすると,その用法について記述しようとすれば,その分類は,語形成とか,節から句への転換とかいう場合を除いては全く無意味になろう.このように意味基準の品詞分類の無益さから,次に機能,形態を基準にした分類が考えられる.

意味による分類は,言うまでもなく意味論としてはおおいに意義があるのだが,品詞を区切る基準としては有益ではないようだ.とすると,品詞というのは,そもそも意味が関わる余地が少ないということになるのだろうか.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2025-02-13 Thu

■ #5771. 品詞とは何か? --- 分類基準の問題 [pos][terminology][linguistics][history_of_linguistics][category][structuralism]

「#5763. 品詞とは何か? --- ただの「語類」と呼んではダメか」 ([2025-02-05-1]) と「#5765. 品詞とは何か? --- Bloomfield の見解」 ([2025-02-07-1]) で品詞論を紹介してきた.今回は『新英語学辞典』の parts of speech の項を参照しながら,英語の伝統的な8品詞の分類基準について考えてみる.

英語の伝統的な8品詞は,意味,機能,形態の3つの分類基準がごちゃ混ぜになった分類であり,理論的には問題があるとされる.まず,名詞,形容詞,動詞,間投詞については,主に意味的な基準で分けられているといってよい.もちろん意味的な基準といっても微妙なケースはいくらでもある.英語で white は,日本語では「白」という名詞にも,「白い」という形容詞にも相当し,意味的には互いに限りなく近い.同様に,分詞は形容詞と動詞の合いの子といってよいが,合いの子からみればいずれにも意味的に近い.さらに,以上4品詞の分類については形態的な基準も少なからず関わっており,意味的な基準だけで語れるわけではない.間投詞は他と比べて意味的な自律性があるといえそうだが,これもまだ検討の余地があるかもしれない.

一方,代名詞,副詞,接続詞は機能的な基準による分類だ.ただし,言語において「機能的」とのラベルはカバーする範囲が非常に広い.かりに「統語的」と狭めておけば,それなりに説明できるかもしれないが,グレーゾーンは残る.副詞や接続詞は統語的に決定できそうだが,代名詞は統語論的機能と同時に語用論的機能も帯びており,「機能的」のカバー範囲をもっと広めに設定しておく必要があるようにも思われる.

最後に前置詞はどうだろうか.基本的には統語的な機能の観点からの分類といってよさそうだが,意味的な考慮が入っていないとはいえない.like や worth は後ろに「目的語」らしきものをとる点で統語的には前置詞的な振る舞いを示すが,比較的中身のある語彙的意味をもっている点では形容詞ぽい.

品詞間の境目が明確でないという問題自体は古くからあり,個々の論点が指摘されてきたが,それ以前に3つの分類基準が複雑にオーバーラップしているという本質的な課題を抱えているのである.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2025-02-07 Fri

■ #5765. 品詞とは何か? --- Bloomfield の見解 [pos][terminology][linguistics][history_of_linguistics][category][structuralism]

一昨日の記事「#5763. 品詞とは何か? --- ただの「語類」と呼んではダメか」 ([2025-02-05-1]) で,"parts of speech" (品詞),"word-class" (語類),"form-class" (形式類)といった近似する用語群について考えた.アメリカ構造主義の旗手 Bloomfield は,代表的著書 Language (§12.11) にて,この3つを区別して考えている.

The syntactic form-classes of phrases . . . can be derived from the syntactic form-classes of words: the form-classes of syntax are most easily described in terms of word-classes. Thus, in English, a substantive expression is either a word (such as John) which belongs to this form-class (a substantive), or else a phrase (such as poor John) whose center is a substantive; and an English finite verb expression is either a word (such as ran) which belongs to this form-class (a finite verb), or else a phrase (such as ran away) whose center is a finite verb. An English actor-action phrase (such as John ran or poor John ran away) does not share the form-class of any word, since its construction is exocentric, but the form-class of actor-action phrases is defined by their construction: they consist of a nominative expression and a finite verb expression (arranged in a certain way), and this, in the end, again reduces the matter to terms of word-classes.

The term parts of speech is traditionally applied to the most inclusive and fundamental word-classes of a language, and then, in accordance with the principle just stated, the syntactic form-classes are described in terms of the parts of speech that appear in them. However, it is impossible to set up a fully consistent scheme of parts of speech, because the word-classes overlap and cross each other.

form-class は語句の統語的な役割に対応する単位,word-class はその form-class の典型的な主要部を示す語の属する語彙的な区分,parts of speech はその word-class の伝統的で基本的な型,ということになるだろうか.

あえてすっきりまとめるのであれば,それぞれ統語的単位,語彙的単位,語彙・統語・形態的単位といってよい.「品詞」 (parts of speech) は実用的な便利さゆえに広く用いられているが,実際には複合的(で意外と複雑)な単位ということになる.

・ Bloomfield, Leonard. Language. 1933. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1984.

2025-02-05 Wed

■ #5763. 品詞とは何か? --- ただの「語類」と呼んではダメか [pos][terminology][linguistics][history_of_linguistics][category][structuralism]

昨日の記事 ([2025-02-04-1]) に続き,品詞 (parts of speech, or pos) という概念・用語をめぐる話題.今回は Crystal の言語学用語辞典を繰ってみた.

part of speech The TRADITIONAL term for a GRAMMATICAL CLASS of WORDS. The main 'parts of speech' recognized by most school grammars derive from the work of the ancient Greek and Roman grammarians, primarily the NOUN, PRONOUN, VERB, ADVERB, ADJECTIVE, PREPOSITION, CONJUNCTION and INTERJECTION, with ARTICLE, PARTICIPLE and others often added. Because of the inexplicitness with which these terms were traditionally defined (e.g. the use of unclear NOTIONAL criteria), and the restricted nature of their definitions (reflecting the characteristics of Latin or Greek), LINGUISTS tend to prefer such terms as WORD-class or FORM-class, where the grouping is based on FORMAL criteria of a more UNIVERSALLY applicable kind.

ギリシア語やラテン語の文法の遺産を引き継いだ歴史的で伝統的な文法範疇 (category) であることが強調されており,それが必ずしも明確な語彙の区分であるわけではないことにも触れられている.従来,品詞は概念的な語彙区分として理解されることが多かったが,実際にはそれも "unclear" (不明確)であるとすら述べられている.

加えて,Crystal は言語学ではむしろ "word-class" (語類)や "form-class" (形式類)と呼ぶ向きも多いと述べている.確かに「品詞」という用語を敢えて避けるケースはありそうだ.「品詞」できれいに割り切れない場合に,より一般的な概念・用語としての「語類」を持ち出すことはあると思う.

それでも,言語学においては,拠って立つ理論次第ではあるが,「品詞」はあまりに便利すぎて手放せないケースのほうが多いのではないか.方便としてここまで踏み固められた「品詞」を手放すのは惜しい.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2025-02-04 Tue

■ #5762. 品詞とは何か? --- 日本語の「品詞」を辞典・事典で調べる [pos][terminology][linguistics][history_of_linguistics][category]

品詞 (parts of speech, or pos) は最古の文法範疇の1つといってよい.古代から現代にいたる広い意味での言語学 (linguistics) の歴史のなかで,きわめて有用であり続けた言語理論である.

日本語の「品詞」という用語について,国語辞典や百科事典の記述を確かめてみたい.まず『日本国語大辞典』より.

ひん-し【品詞】〔名〕〈英 parts of speech の訳語〉({英}parts of speech の訳語)文法上の意義・職能・形態などから分類した単語の区分け。欧米語の学校文法では、現在一般に八品詞(名詞・代名詞・形容詞・動詞・副詞・接続詞・前置詞・間投詞)とされる。国文法では、名詞・数詞・代名詞・動詞・形容詞・形容動詞・連体詞・副詞・接続詞・感動詞・助詞・助動詞が挙げられるが、併合、細分する場合もあり、また、学説によって異同がある。「品詞」の語は、日本文法書としては、明治七年(一八七四)に田中義廉が「小学日本文典」で七品詞を説いたのが最も早い。*小学日本文典〔1874〕〈田中義廉〉二・八「七品詞の名目」*風俗画報‐一六八号〔1898〕言語門「一は品詞の如何に関せず、単に標準語を伊呂波順に配列し而して是に対照する方言を蒐集するもの」*日本文法中教科書〔1902〕〈大槻文彦〉一「単語の以上八品を品詞と名づく」*中等教科明治文典〔1904〕〈芳賀矢一〉一・一三「助詞は種々の品詞の下につきて他の品詞との関係を示し又は其作用を助くる詞なり」

次に『デジタル大辞泉』より.

ひん-し【品詞】《parts of speech》文法上の職能によって類別した単語の区分け。国文法ではふつう、名詞・代名詞・動詞・形容詞・形容動詞・連体詞・副詞・接続詞・感動詞・助動詞・助詞の11品詞に分類する。分類については、右のうち、形容動詞を認めないものや、右のほかに数詞を立てるものなど、学説により異同がある。

『世界大百科事典』では長い項目となっている.冒頭の1段落のみを引用する.

品詞 ひんし

文法用語の一つ。それぞれの言語における発話の規準となる単位,すなわち,文は,文法のレベルでは最終的に単語に分析しうる(逆にいえば,単語の列が文を形成する)。そのような単語には,あまり多くない数の範疇(はんちゆう)(カテゴリー)が存在して,すべての単語はそのいずれかに属している。一つの範疇に属する単語はある種の機能(用いられ方,すなわち,文中のどのような位置に現れるか)を共有している。こうした範疇を従来より品詞 parts of speech と呼んできた。名詞とか動詞とかと呼ばれているものがそれである。

『日本大百科全書』でも長い項目なので,最初の3段落のみ示す.

品詞 ひんし

文法上の記述、体系化を目的として、あらゆる語を文法上の性質に基づいて分類した種別。語義、語形、職能(文構成上の役割)などの観点が基準となる。個々の語はいずれかの品詞に所属することとなる。

品詞の名称は parts of speech (英語)、parties du discours (フランス語)などの西洋文典の術語の訳として成立したもの。江戸時代には、オランダ文法の訳語として、「詞品」「蘭語九品」「九品の詞」のようなものがあった。語の分類意識としては、日本にも古くからあり、「詞」「辞」「てにをは」「助け字」「休め字」「名(な)」などの名称のもとに語分類が行われていたが、「品詞」という場合は、一般に、西洋文典の輸入によって新しく考えられた語の類別をさす。品詞の種類、名称には、学説によって多少の異同もあるが、現在普通に行われているものは、名詞・数詞・代名詞・動詞・形容詞・形容動詞・連体詞・副詞・接続詞・感動詞・助詞・助動詞などである。これらのうちの数種の上位分類である「体言」「用言」などの名称、および下位分類である「格助詞」「係助詞」なども品詞として扱われることもある。なお、「接頭語」「接尾語」なども品詞の名のもとに用いられることもある。

それぞれの品詞に所属する具体的な語も、学説によって異同がある。たとえば、受身・可能・自発・尊敬・使役を表す「る・らる・す・さす・しむ(れる・られる・せる・させる)」は、山田孝雄 (よしお) の学説では「複語尾」、橋本進吉の学説では「助動詞」、時枝誠記 (もとき) の学説では「接尾語」とされる。現在の国語辞書では、見出し語の下に品詞名を記すことが普通である。ただし、圧倒的に数の多い「名詞」については、これを省略しているものが多い。

重要と思われる4点を抽出すると,次のようになる.

・ 品詞は語を意義・職能・形態によって区分したものである

・ 学説・論者によって品詞の区分や数が異なる

・ 一般に区分された品詞の数は少数で,一つひとつの単語はいずれかの品詞に属する

・ 日本語の「品詞」は,西洋語から輸入された語の区分を指すのに主として用いられる

2025-01-19 Sun

■ #5746. etymology の語源 [etymology][terminology][kdee][oed][etymological_fallacy][language_myth]

語源 (etymology) について,最近の記事として「#5737. 語源,etymology, veriloquium」 ([2025-01-10-1]) と「#5739. 定期的に考え続けたい「語源とは何か?」」 ([2025-01-12-1]) で考えた.今回は etymology という用語自体について検討する.

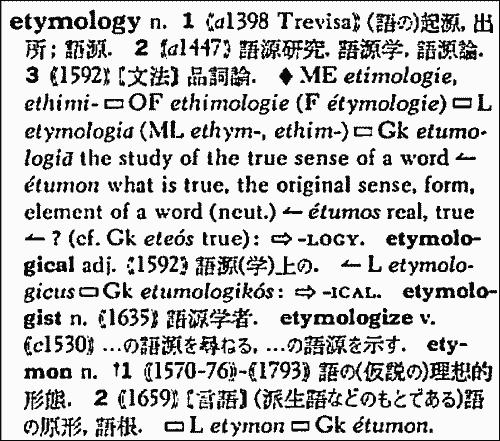

英単語 etymology は,ギリシア語に端を発し,ラテン語,古フランス語を経由して,後期中英語に入ったが,もともとは高度に専門的な用語である.『英語語源辞典』の etymology の項目を掲げる.

OED の etymology, n. では,部分的にフランス語から,部分的にラテン語から入ったものとして,つまり "Of multiple origins" として解釈している.それぞれの経路について,次のように述べている.

< (i) Middle French ethimologie, ethymologie (French etymologie) established account of the origin of a given word, explaining its composition (2nd half of the 12th cent. in Old French; frequently from early 16th cent.), interpretation of a word, that which is revealed by such interpretation (c1337), the branch of linguistics concerned with determining of the origins of words (1622 in the passage translated in quot. 1630 at sense 5, or earlier),

and its etymon (ii) classical Latin etymologia (in post-classical Latin also aethimologia, ethimologia, ethymologia) interpretation and explanation of a word on the basis of its origin < Hellenistic Greek ἐτυμολογία, probably < Byzantine Greek ἐτυμολόγος (although this is apparently first attested later: see etymologer n.) + -ία -y suffix3; on the semantic motivation for the Greek word see etymon n. and discussion at that entry.

語源的意味こそが「真の意味」であるとする考え方については,OED の 2.a.i. にて次の注意書きがある.

The idea that a word's origin conveys its true meaning (cf. discussion at etymon n.) has become progressively discredited since the 18th cent. with the increased study of etymology as a linguistic science (see sense 5). It is now sometimes referred to as the etymological fallacy.

注意すべきは etymology の学問分野としての語義である.OED の第3語義は「語源学」ではなく「品詞論」を指し,c1475 を初出として次のようにみえる.

3. Grammar. A branch of grammar which deals with the formation and inflection of individual words and their different parts of speech. Now historical.

現代的な「語源学」の語義は OED の第5語義に相当し,初出は1630年と若干遅い.

5. The branch of linguistics which deals with determining the origin of words and the historical development of their form and meanings.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

2025-01-10 Fri

■ #5737. 語源,etymology, veriloquium [etymology][terminology][greek][latin][oe][aelfric]

下宮忠雄(著)『歴史比較言語学入門』(開拓社,1999年)の第9章は「語源学」と題されている.『スタンダード英語語源辞典』の編者の1人でもあるし,思い入れの強い章かと想像される.下宮 (131) は第9章の冒頭でこう書いている.

言語学概論の1年間の授業が終わったあとで,何が印象に残っているか,何が面白かったかを試験問題の最後に問うと,語源と意味論という返事が圧倒的に多い.言語の研究は古代ギリシアに始まるが,そこでは,文法 (grammar) と語源 (etymology) が言語研究の2つの柱だった.

単語は一つ一つが歴史を持っている.語源 (etymology) は単語の本来の意味(これをギリシア語では etymon という)を探り,その歴史を記述する.したがって,意味論とも大いに関係をもっている.Cicero (キケロー)はギリシア語の etymologia を vēriloquium (vērum 「真実」,loquium 「語ること,ことば」)とラテン語に訳したが,修辞学者 Quintilianus [クウィンティリアーヌス]が etymologia にもどし,これが西欧諸国に伝わって今日にいたっている.grammar も etymology も2千年以上も前のギリシア人が創造した用語である.

「語源」を意味する語が,西洋語の歴史において変遷してきたというのは知らなかった.ギリシア語由来の etymology の響きは高尚で好きだが,キケローのラテン語 vēriloquium も味わいがある.いずれも英語本来語でいえば true word ほどである.そこに日本語あるいは漢語の「語源」に含まれる「みなもと」の意味要素が(少なくとも明示的には)含まれていない点がおもしろい.

ちなみに,ギリシア語由来ながらもラテン語に取り込まれていた ethymologia の単語は,古英語でも術語として受容されていたようで,OED によると Ælfric, Grammar (St. John's Oxford MS.) 293 に文証される.

Sum þæra [sc. divisions of the art of grammar] hatte ETHIMOLOGIA, þæ is namena ordfruma and gescead, hwi hi swa gehatene sind.

この時点ではあくまでラテン単語としての受容にすぎなかったとはいえ,英語文化において etymology は相当に長い歴史をもっているといえる.

(以下,後記:2025/01/12(Sun))

・ heltalk 「ラテン語で「語源」を意味する veriloquium もカッコいいですね」 (2025/01/10)

・ heldio 「#1322. word-lore 「語誌」っていいですよね」 (2025/01/11)

・ 下宮 忠雄 『歴史比較言語学入門』 開拓社,1999年.

・ 下宮 忠雄・金子 貞雄・家村 睦夫(編) 『スタンダード英語語源辞典』 大修館,1989年.

2024-12-01 Sun

■ #5697. royal we は「君主の we」ではなく「社会的不平等の複数形」? [terminology][oe][me][royal_we][monarch][personal_pronoun][pronoun][sociolinguistics][politeness][t/v_distinction][honorific][number][shakespeare]

数日間,「君主の we」 (royal_we) 周辺の問題について調べている.Jespersen に当たってみると「君主の we」ならぬ「社会的不平等の複数形」 ("the plural of social inequality") という用語が挙げられていた.2人称代名詞における,いわゆる "T/V distinction" (t/v_distinction) と関連づけて we を議論する際には,確かに便利な用語かもしれない.

4.13. Third, we have what might be called the plural of social inequality, by which one person either speaks of himself or addresses another person in the plural. We thus have in the first person the 'plural of majesty', by which kings and similarly exalted persons say we instead of I. The verbal form used with this we is the plural, but in the 'emphatic' pronoun with self a distinction is made between the normal plural ourselves and the half-singular ourself. Thus frequently in Sh, e.g. Hml I. 2.122 Be as our selfe in Denmarke | Mcb III. 1.46 We will keepe our selfe till supper time alone. (In R2 III. 2.127, where modern editions have ourselves, the folio has our selfe; but in R2 I. 1,16, F1 has our selues). Outside the plural of majesty, Sh has twice our selfe (Meas. II. 2.126, LL IV. 3.314) 'in general maxims' (Sh-lex.).

. . . .

In the second person the plural of social inequality becomes a plural of politeness or deference: ye, you instead of thou, thee; this has now become universal without regard to social position . . . .

The use of us instead of me in Scotland and Ireland (Murray D 188, Joyce Ir 81) and also in familiar speech elsewhere may have some connexion with the plural of social inequality, though its origin is not clear to me.

ベストな用語ではないかもしれないが,社会的不平等における「上」の方を指すのに「敬複数」 ("polite plural") などの術語はいかがだろうか.あるいは,これではやや綺麗すぎるかもしれないので,もっと身も蓋もなく「上位複数」など? いや,一回りして,もっとも身も蓋もない術語として「君主複数」でよいのかもしれない.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 2. Vol. 1. 2nd ed. Heidelberg: C. Winter's Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1922.

2024-11-26 Tue

■ #5692. royal we --- 君主は自身を I ではなく we と呼ぶ? [personal_pronoun][pronoun][royal_we][monarch][terminology][indefinite_pronoun][reflexive_pronoun][number]

「君主の we」 (royal_we) と称される伝統的な用法がある.王や女王が,自身1人のことを指して I ではなく we を用いるという特別な一人称代名詞の使い方である.この用法については「#5284. 単数の we --- royal we, authorial we, editorial we」 ([2023-10-15-1]) で OED を参照しつつ少々取り上げた.

この特殊用法について,Quirk et al. の §6.18 の Note [a] に次のような記述がある.

[a] The virtually obsolete 'royal we' (= I) is traditionally used by a monarch, as in the following examples, both famous dicta by Queen Victoria:

We are not interested in the possibilities of defeat. We are not amused.

Quirk et al. の §6.23 には,対応する再帰代名詞 ourself への言及もある.

There is also . . . a very rare 'royal we' singular reflexive pronoun ourself . . . .

次に Fowler の語法辞典を調べてみた.その we の項目に,royal we に関する記述があった (835) .

4 The royal we. The OED gives examples from the OE period onward in which we is used by a single sovereign or ruler to refer to himself or herself. The custom seems to be dying out: in her formal speeches Queen Elizabeth II rarely if ever uses it now. (On royal tours when accompanied by the Duke of Edinburgh we is often used by the Queen to refer to them both; alternatively My husband and I.)

History of the term. The OED record begins with Lytton (1835): Noticed you the we---the style royal? Later examples: The writer uses 'we' throughout---rather unfortunately, as one is sometimes in doubt whether it is a sort of 'royal' plural, indicating only himself, or denotes himself and companions---N&Q 1931; 'In the absence of the accused we will continue with the trial.' He used the royal 'we', but spoke for us all---J. Rae, 1960. (The last two examples clearly overlap with those given in para 3.) It will be observed that the term 'the royal we' has come to be used in a weakened, transferred, or jocular manner. The best-known example came when Margaret Thatcher informed the world in 1989 that her daughter-in-law had given birth to a son: We have become a grandmother, the Prime Minister said. A less well-known American example: interviewed on a television programme in 1990 Vice-President Quayle, in reply to the interviewer's expression of hope that Quayle would join him again some time, replied We will.

なお,上の引用の中程に言及のある"para 3" では,indefinite we が扱われていることを付け加えておく.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

・ Burchfield, Robert, ed. Fowler's Modern English Usage. Rev. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1998.

2024-11-16 Sat

■ #5682. Low Dutch という略称 [dutch][low_german][flemish][contact][lexicology][borrowing][loan_word][terminology][germanic][variety]

「#2646. オランダ借用語に関する統計」 ([2016-07-25-1]) で,英語史におけるオランダ借用語をめぐって Durkin を参照した.そこで Dutch でも Low German でもなく,中間的な Low Dutch という用語が使われていた.これが何を指すのかといえば,Durkin 自身が丁寧に解説してくれていた.その1節 (354) を読んでみよう.

Loanwords into English from Dutch (including Flemish) and Low German are normally considered together, because it is so difficult to tell them apart. This is partly because word forms in both languages were, and to some extent still are, so similar, and partly because the social and cultural circumstances of borrowing into English are also often hard to tell apart. 'Low Dutch' is sometimes used as a collective cover term for borrowings from either or both languages into English, although it is important to note that Low Dutch is not itself a language name, but simply a terminological shorthand for referring to a complex situation.

Dutch と Low German は各々区別される言語変種ではあるが,単語の形態が互いによく似ており,借用元同定の文脈においては,実際上区別がつかないことも多いために,便宜上2変種を合わせた用語として Low Dutch を設定しておく,ということだ.ある意味で Low Dutch はフィクションということになる.フランス借用語かラテン借用語か判別がつきにくいときに,便宜上「フランス・ラテン系借用語」などと一括して呼ぶのに似ている.

しかし,こうした用語のフィクション性それ自体も程度の問題ともいえるかもしれない.というのは,上記の Dutch にしても Low German にしても,「区別される言語変種」と一応のところ述べはしたが,やはり何らかの程度においてフィクションでもあるからだ.この点については「#415. All linguistic varieties are fictions」 ([2010-06-16-1]) を参照.

便利に使えるのであれば Low Dutch というタームは悪くない.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow