2025-04-02 Wed

■ #5819. 開かれたクラス,閉じたクラス,品詞 [pos][terminology][linguistics][category][word_class][prototype][noun][verb][adjective][adverb][lexicology]

pos のタグの着いたいくつかの記事で,品詞とは何かを論じてきた.今回も言語学辞典に拠って,品詞について理解を深めていきたい.International Encyclopedia of Linguistics の pp. 250--51 より,8段落からなる PARTS OF SPEECH の項を段落ごとに引用しよう.

PARTS OF SPEECH. Languages may vary significantly in the number and type of distinct classes, or parts of speech, into which their lexicons are divisible. However, all languages make a distinction between open and closed lexical classes, although there may be relatively few of the latter in languages favoring morphologically complex words. Open classes are those whose membership is in principle unlimited, and may differ from speaker to speaker. Closed classes are those which contain a fixed, usually small number of words, and which are essentially the same for all speakers.

品詞論を始める前に,まず語彙を「開かれたクラス」 (open class) と「閉じたクラス」 (closed class) に大きく2分している.この2分法は普遍的であることが説かれる.

The open lexical classes are nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Not all these classes are found in all languages; and it is not always clear whether two sets of words, having some shared and some unshared properties, should be identified as belonging to distinct open classes, or to subclasses of a single class. Criteria for determining which open classes are distinguished in a given language are syntactic and/or morphological, but the names used to identify the classes are generally based on semantic criteria.

「開かれたクラス」についての説明が始まる.言語にもよるが,概ね名詞,動詞,形容詞,副詞が主に意味的な基準により区別されるという.

The noun/verb distinction is apparently universal. Although the existence of this distinction in certain languages has been questioned, close scrutiny of the facts has invariably shown clear, if sometimes subtle, grammatical differences between two major classes of words, one of which has typically noun-like semantics (e.g. denoting persons, places, or things), the other typically verb-like semantics (e.g. denoting actions, processes, or states).

とりわけ名詞と動詞の2つの品詞については,ほぼ普遍的に区別されるといってよい.

Nouns most commonly function as arguments or heads of arguments, but they may also function as predicates, either with or without a copula such as English be. Categories for which nouns are often morphologically or syntactically specified include case, number, gender, and definiteness.

名詞の典型的な機能や保有する範疇が紹介される.

Verbs most commonly function as predicates, but in some languages may also occur as arguments. Categories for which they are often specified include tense, aspect, mood, voice, and positive/negative polarity.

次に,動詞の典型的な機能や保有する範疇について.

Adjectives are usually identified grammatically as modifiers of nouns, but also commonly occur as predicates. Semantically, they often denote attributes. A characteristic specification is for positive, comparative, or superlative degree. Some languages do not have a distinct class of adjectives, but instead express all typically adjectival meanings with nouns and/or verbs. Other languages have a small, closed class that may be identified as adjectives --- commonly including a few words denoting size, color, age, and value --- while nouns and/or verbs are used to express the remainder of adjectival meanings.

続けて形容詞の典型的な機能が論じられる.言語によっては形容詞という語類を明確にもたないものもある.

Adverbs, often a less than homogeneous class, may be identified grammatically as modifiers of constituents other than nouns, e.g. verbs, adjectives, or sentences. Their semantics typically varies with what they modify. As modifiers of verbs they may denote manner (e.g. slowly); of adjectives, degree (extremely); and of sentences, attitude (unfortunately). Many languages have no open class of adverbs, and express adverbial meanings with nouns, verbs, adjectives窶俳r, in some heavily affixing languages, affixes.

さらに副詞が比較的まとまりのない品詞として紹介される.名詞以外を修飾する語として,意味特性は多様である.

Some commonly attested closed classes are articles, auxiliaries, clitics, copulas, interjections, negators, particles, politeness markers, prepositions and postpositions, pro-forms, and quantifiers. A survey of these and other closed classes, as well as a detailed account of open classes, is given by Schachter 1985.

最後に「閉じたクラス」が簡単に触れられる.

全体的に英語ベースの品詞論となっている感はあるが,理解しやすい解説である.この項の執筆者であり,最後に言及もある Schachter には本格的な品詞論の論考があるようだ.

・ Frawley, William J., ed. International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003.

・ Schachter, Paul. "Parts-of-Speech Systems." Language Typology and Syntactic Description. Vol. 1. Clause Structure. Ed. Timothy Shopen. p. 3?61. Cambridge and New York: CUP, 1985. 3--61.

2024-08-06 Tue

■ #5580. 過去分詞は動詞か形容詞か --- Mond での回答 [prototype][verb][adjective][participle][mond][sobokunagimon][pos][category]

先日,知識共有サービス Mond にて,次の問いが寄せられました.

be + 過去分詞(受身)の過去分詞は,動詞なんですか, それとも形容詞なんですか? The door was opened by John. 「そのドアはジョンによって開けられた」は意味的にも動詞だと思いますが,John is interested in English. 「ジョンは英語に興味がある」は, 動詞というよりかは形容詞だと思います.これらの現象は,言語学的にどう説明されるんでしょうか?

この問いに対して,こちらの回答を Mond に投稿しました.詳しくはそちらを読んでいただければと思いますが,要点としてはプロトタイプ (prototype) で考えるのがよいという回答でした.

過去分詞は動詞由来ではありますが,機能としては形容詞に寄っています.そもそも過去分詞に限らず現在分詞も,さらには不定詞や動名詞などの他の準動詞も,本来の動詞を別の品詞として活用したい場合の文法項目ですので,動詞と○○詞の両方の特性をもっているのは不思議なことではなく,むしろ各々の定義に近いところのものです.

上記の Mond の回答では,動詞から形容詞への連続体を想定し,そこから4つの点を取り出すという趣旨で例文を挙げました.回答の際に参照した Quirk et al. (§3.74--78) の記述では,実はもっと詳しく8つほどの点が設定されています.以下に8つの例文を引用し,Mond への回答の補足としたいと思います.(1)--(4) が動詞ぽい半分,(5)--(8) が形容詞ぽい半分です.

(1) This violin was made by my father

(2) This conclusion is hardly justified by the results.

(3) Coal has been replaced by oil.

(4) This difficulty can be avoided in several ways.

(5) We are encouraged to go on with the project.

(6) Leonard was interested in linguistics.

(7) The building is already demolished.

(8) The modern world is getting ['becoming'] more highly industrialized and mechanized.

この問題と関連して,以下の hellog 記事もご参照ください.

・ 「#1964. プロトタイプ」 ([2014-09-12-1])

・ 「#3533. 名詞 -- 形容詞 -- 動詞の連続性と範疇化」 ([2018-12-29-1])

・ 「#4436. 形容詞のプロトタイプ」 ([2021-06-19-1])

・ 「#3307. 文法用語としての participle 「分詞」」 ([2018-05-17-1])

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2023-09-23 Sat

■ #5262. 秋元実治先生との「他動性」談義 [transitivity][voicy][heldio][prototype][terminology][subjectification][language_change]

昨日の Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」にて,「#844. 他動性とは何か? --- 秋元実治先生との対談」を配信しました.30分ほどの濃密な transitivity 談義です.秋元先生のご著書「#5184. 秋元実治『イギリス哲学者の英語』(開拓社,2023年)」 ([2023-07-07-1]) の議論に基づいた談義となっていますので,そちらもご覧いただければと思います.

対談でも論じている通り,他動性とは絶対的な指標というよりは,相対的で連続的でプロトタイプ的な指標です.他動性を決定するパラメータは様々ありますし,言語によっ具現化の仕方は異なります.それくらい抽象度の高い概念ではありますが,だからこそ広く一般的な言語の諸現象に関わってくるのであり,理論的にも興味深い視点となるわけです.主体性 (agentivity) や主観化 (subjectification) という概念とも複雑に関連してくるようで,合わせて言語変化の潮流を記述する有望な道具立てとなりそうです.

他動性については,本ブログでも次の記事を書いてきました.参考まで.

・ 「#5202. 他動性 (transitivity) とは何か?」 ([2023-07-25-1])

・ 「#5204. 他動性 (transitivity) とは何か? (2)」 ([2023-07-27-1])

・ 「#5209. 他動性 (transitivity) とは何か? (3)」 ([2023-08-01-1])

2023-07-15 Sat

■ #5192. 何に名前をつけるのか? --- 固有名を名付ける対象のプロトタイプ [onomastics][prototype][noun][hypostasis][semiotics][typology][trademark][personal_name][toponymy]

人は何に名前をつけるのか.理論的には,ありとあらゆるものに名前をつけられる.実際上も,人は言語を通じて森羅万象にラベルを貼り付けてきた.それが名詞 (noun) である.ただし,今回考えたいのはもう少し狭い意味での名前,いわゆる固有名である.人は何に固有名をつけるのか.

Van Langendonck and Van de Velde (33--38) は,異なる様々な言語を比較した上で,主に文法的な観点から,名付け対象を典型順に(よりプロトタイプ的なものからそうでないものへ)列挙している.ただし,網羅的な一覧ではないとの断わり書きがあることをここに明記しておく.

・ 人名

・ 地名

・ 月名

・ 商品名,商標名

・ 数

・ 病気名,生物の種の名前

・ "autonym"

論文では各項目に解説がつけられているが,ここでは最後の "autonym" を簡単に紹介しておこう.一覧のなかでは最もプロトタイプ的ではない位置づけにある名付け対象である.これは,例えば "Bank is a homonymous word." 「Bank (という単語)は同音異義語である」という場合の Bank のことを指している.ありとあらゆる言語表現が,その場限りで「名前」となり得る,ということだ.この臨時的な名付けには「#1300. hypostasis」 ([2012-11-17-1]) が関係してくる.

一覧の下から2番目にある病気名などは,名付け対象としてのプロトタイプ性が低いので,言語によっては固有名を与えられず,あくまで普通名詞として通っているにすぎない,というケースもある.確かに Covid-19 は固有名詞ぽいが,ただの風邪 cold は普通名詞ぽい.何に固有名をつけるのかという問題については,通言語学的に傾向はあるものの,あくまでプロトタイプとして考える必要があるということだろう.

・ Van Langendonck, Willy and Mark Van de Velde. "Names and Grammar." Chapter 2 of The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. Ed. Carole Hough. Oxford: OUP, 2016. 17--38.

2023-07-14 Fri

■ #5191. 「名前」とは何か? [terminology][onomastics][prototype][noun]

固有名詞学 (onomastics) のハンドブックにおいて,name (名前)の定義がいくつかの形で提示されている.第2章の結論の記述が最もよくまとまっているように思われるので,その部分を引用しよう.

Names are nouns with unique denotation, they are definite, have no restrictive relative modifiers, and occupy a special place in anaphoric relations. They display an inherent basic level and can be argued to be the most prototypical nominal category. Names have no defining sense. They can have connotative meanings, but this has little grammatical relevance. We have stressed the need to rely on grammatical criteria, which are too often ignored in approaches to names.

The approach developed in this chapter aims at being universally valid in two ways. First, the pragmatic-semantic concept of names defined in the introduction is cross-linguistically applicable. It is distinct from language-specific grammatical categories of Proper Names for which language-specific grammatical criteria should be adduced. Second, our approach takes into account all types of proper names. The question of what counts as a name, very often debated in the literature, should be answered on two levels, keeping in mind the distinction between proprial lemmas and proper names. The language specific question as to what belongs to the grammatical category of Names does not necessarily yield the same answer as the question of what can be considered to be a name from a semantic-pragmatic point of view. Mismatches are most likely to be found at the bottom of the cline of nameworthiness . . . . (Langendonck and Van de Velde 38)

正確にいえば,この文章は name の定義というよりも,name に確認される典型的な複数の特徴を記述したものと考えられる.第2段落にあるように,この定義なり特徴は,(1) 通言語学的に有効であり,(2) 人名や地名に限らずあらゆる種類の名前に当てはまる,という2点において,よく練られたものといってよさそうだ.さらにこの文章からは,名前をめぐる議論では,ある項目が名前か否かというデジタルな問題ではなく,「名前らしさ」のプロトタイプの問題,程度の問題としてとらえる必要があることも示唆されている.

「名前」がこれほど複雑で奥行きのある話題だとは思わなかった.

・ Van Langendonck, Willy and Mark Van de Velde. "Names and Grammar." Chapter 2 of The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. Ed. Carole Hough. Oxford: OUP, 2016. 17--38.

2023-03-26 Sun

■ #5081. 談話標識の意味に対する3つのアプローチ [discourse_marker][pragmatics][prototype][semantics][polysemy][homonymy]

「#5074. 英語の談話標識,43種」 ([2023-03-19-1]),「#5075. 談話標識の言語的特徴」 ([2023-03-20-1]) で談話標識 () 的にとらえていくのがよいだろうという見解である.

実はこの3つのアプローチは,談話標識の意味にとどまらず,一般の語の意味を分析する際にもそのまま応用できる.要するに,同音異義 (homonymy) の問題なのか,あるいは多義 (polysemy) の問題なのか,という議論だ.これについては,以下の記事も参照されたい.

・ 「#286. homonymy, homophony, homography, polysemy」 ([2010-02-07-1])

・ 「#815. polysemic clash?」 ([2011-07-21-1])

・ 「#1801. homonymy と polysemy の境」 ([2014-04-02-1])

・ 「#2823. homonymy と polysemy の境 (2)」 ([2017-01-18-1])

・ 松尾 文子・廣瀬 浩三・西川 眞由美(編著) 『英語談話標識用法辞典 43の基本ディスコース・マーカー』 研究社,2015年.

2023-03-24 Fri

■ #5079. 商標 (trademark) の言語学的な扱いは難しい [trademark][onomastics][eponym][semantic_change][prototype]

昨日の記事で紹介した「#5078. 法言語学 (forensic linguistics)」 ([2023-03-23-1]) は広く「法と言語」を扱う分野ととらえてよい.そこで論じられる問題の1つに商標 (trademark) がある.商標にはコピーライトが付与され,法的に守られることになるが,対応する商品があまりに人気を博すると,商標は総称的 (generic) な名詞,つまり普通名詞に近づいてくる.法的に守られているとはいえ,社会の大多数により普通名詞として用いられるようになれば,法律とて社会の慣用に合わせて変化していかざるを得ないだろう.商標を言語的に,社会的にどのように位置づけるかは実際的な問題である.

McArthur の用語辞典を参照すると,trademark が言語学的に厄介であることがよく分かる.

TRADEMARK, also trade mark, trade-mark, [16c]. . . . A sign or name that is secured by legal registration or (in some countries) by established use, and serves to distinguish one product from similar brands sold by competitors: for example, the shell logo for Shell, the petroleum company, and the brand name Jacuzzi for one kind of whirlpool bath. Legal injunctions are often sought when companies consider that their sole right to such marks has been infringed; the makers of Coke, Jeep, Jell-O, Kleenex, Scotch Tape, and Xerox have all gone to court in defence of their brand (or proprietary) names . . . . Although companies complain when their trademarks begin to be used as generic terms in the media or elsewhere, their own marketing has often, paradoxically, caused the problem: 'Most marketing people will try hard to get their brand names accepted by the public as a generic. It's the hallmark of success. But then the trademarks people have to defend the brand from becoming a generic saying it is unique and owned by the company' (trademark manager, quoted in Journalist's Week, 7 Dec. 1990).

There is in practice a vague area between generic terms proper, trademarks that have become somewhat generic, and trademarks that are recognized as such. The situation is complicated by different usages in different countries: for example, Monopoly and Thermos are trademarks in the UK but generics in the US. Product wrappers and business documents often indicate that a trademark is registered by adding TM (for 'trademark') or R (for 'registered') in a superscript circle after the term, as with English TodayTM, Sellotape®. The term usually differs from trade name [first used c.1860s] by designating a specific product and not a business, service, or class of goods, articles, or substances: but some trademarks and trade names may happen to be the same. Everyday words of English that were once trademarks (some now universal, some more common in one variety of English than another, some dated, all commonly written without an initial capital) include aspirin, bandaid, cellophane, celluloid, cornflakes, dictaphone, escalator, granola, hoover, kerosene, lanolin, mimeograph, nylon, phonograph, shredded wheat, zipper. Trademarks facing difficulties include Astroturf, Dacron, Formica, Frisbee, Hovercract, Jacuzzi, Laundromat, Mace, Muzak, Q-Tips, Scotch Tape, Styrofoam, Teflon, Vaseline, Xerox. The inclusion of such names in dictionaries, even when marked 'trademark' or 'proprietary term', indicates that their status has begun to shift. Trademark names used as verbs are a further area of difficulty, both generally and in lexicography. One solution adopted by publishers of dictionaries is to regard the verb forms as generic, with a small initial letter: that is, Xerox (noun), but xerox (verb).

商標の位置づけが空間的に変異し,時間的に変化し得るとなれば,言語変化や歴史言語学の話題としてみることもできるだろう.「商標の英語史」というのもなかなかおもしろそうなテーマではないか.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

2023-03-20 Mon

■ #5075. 談話標識の言語的特徴 [discourse_marker][pragmatics][prototype][category]

昨日の記事「#5074. 英語の談話標識,43種」 ([2023-03-19-1]) で紹介した松尾ほか編著の『英語談話標識用法辞典』の補遺では,談話標識 (discourse_marker) についての充実した解説が与えられている.特に「談話標識についての基本的な考え方」の記事は有用である.

談話標識は品詞よりも一段高いレベルのカテゴリーであり,かつそのカテゴリーはプロトタイプ (prototype) として解釈されるべきものである,という説明から始まる.談話標識そのものがあるというよりも,談話標識的な用法がある,という捉え方に近い.その後に「談話標識の一般的特徴」と題するコラムが続く (333--34) .とてもよくまとまっているので,ここに引用しておきたい.

談話標識に共通する最も一般的な特徴は,「話し手の何らかの発話意図を合図する談話機能を備えている」ことである.ただし,「談話」 (discourse) は広義にとらえて,談話標識が現れる前後の文脈や,テクストとして具現化される文脈のみならず発話状況 (utterance situation) 全体を含むものとする.さらに,その発話状況に参与する話し手・聞き手の知識やコミュニケーションの諸要素が談話標識の機能に関与する.以下,いくつかの観点から談話標識の特徴をまとめる.

【語彙的・音韻的特徴】

(a) 一語からなるものが多いが,句レベル,節レベルのものも含まれる.

(b) 伝統的な単一の語類には集約できない.

(c) ポーズを伴い,独立した音調群を形成することが多い.

(d) 談話機能に応じ,さまざまな音調を伴う.

【統語的特徴】

(a) 文頭に現れることが多いが,文中,文尾に生じるものもある.

(b) 命題の構成要素の外側に生じる,あるいは統語構造にゆるやかに付加されて生じる.

(c) 選択的である.

(d) 複数の談話標識が共起することがある.

(e) 単独で用いられることがある.

【意味的特徴】

(a) それ自体で,文の真偽値に関わる概念的意味をほとんど,あるいは全く持たないものが多い.

(b) 文の真偽値に関わる概念的意味を持つ場合にも,文字通りの意味を表さ場合が多い.

【機能的特徴】

多機能的で,いくつかの談話レベルで機能するものが多い.

【社会的・文体的特徴】

(a) 書き言葉より話し言葉で用いられる場合が多い.

(b) くだけた文体で用いられるものが多い.

(c) 地域的要因,性別,年齢,社会階層,場面などによる特徴がある.

様々な角度から分析することのできる奥の深いカテゴリーであることが分かるだろう.昨日の記事 ([2023-03-19-1]) の43種の談話標識を思い浮かべながら,これらの特徴を確認されたい.

・ 松尾 文子・廣瀬 浩三・西川 眞由美(編著) 『英語談話標識用法辞典 43の基本ディスコース・マーカー』 研究社,2015年.

2022-12-17 Sat

■ #4982. 名詞と代名詞は異なる品詞か否か? [pos][noun][pronoun][category][sobokunagimon][prototype]

名詞 (noun) と代名詞 (pronoun) は2つの異なる品詞とみなすべきか,あるいは後者は前者の一部ととらえるべきか.品詞分類はなかなか厳密にはいかないのが常であり,見方によってはいずれも「正しい」という結論になることが多い.昨今は明確に白黒をつけるというよりは,プロトタイプ (prototype) としてファジーに捉えておくのがよい,という見解が多くなっているのかもしれない.しかし,最終的にはケリをつけないと気持ちが悪いと思うのも人間の性であり,やっかいなテーマだ.

Aarts が両陣営の議論をまとめているので引用する.

[ 名詞と代名詞は異なるカテゴリーとみなすべきである (Aarts, p. 25) ]

・ Pronouns show nominative and accusative case distinctions (she/her, we/us, etc.); common nouns do not.

・ Pronouns show person and gender distinctions; common nouns do not.

・ Pronouns do not have regular inflectional plurals in Standard English.

・ Pronouns are more constrained than common nouns in taking dependents.

・ Noun phrases with common or proper nouns as head can have independent reference, i.e. they can uniquely pick out an individual or entity in the discourse context, whereas the reference of pronouns must be established contextually.

[ 名詞と代名詞は同一のカテゴリーとみなすべきである (Aarts, p. 26) ]

・ Although common nouns indeed do not have nominative and accusative case inflections they do have genitive inflections, as in the doctor's garden, the mayor's expenses, etc., so having case inflections is not a property that is exclusive to pronouns.

・ Indisputably, only pronouns show person and arguably also gender distinctions, but this is not a sufficient reason to assign them to a different word class. After all, among the verbs in English we distinguish between transitive and intransitive verbs, but we would not want to establish two distinct word classes of 'transitive verbs' and 'intransitive verbs'. Instead, it would make more sense to have two subcategories of one and the same word class. If we follow this reasoning we would say that pronouns form a subcategory of nouns that show person and gender distinctions.

・ It's not entirely true that pronouns do not have regular inflectional plurals in Standard English, because the pronoun one can be pluralized, as in Which ones did you buy? Another consideration here is that there are regional varieties of English that pluralize pronouns (for example, Tyneside English has youse as the plural of you, which is used to address more than one person . . . . And we also have I vs. we, mine vs. ours, etc.

・ Pronouns do seem to be more constrained in taking dependents. We cannot say e.g. *The she left early or *Crazy they/them jumped off the wall. However, dependents are not excluded altogether. We can say, for example, I'm not the me that I used to be. or Stupid me; I forgot to take a coat. As for PP dependents: some pronouns can be followed by prepositional phrases in the same way as nouns can. Compare: The shop on the corner and one of the students.

・ Although it's true that noun phrases headed by common or proper nouns can have independent reference, while pronouns cannot, this is a semantic difference between nouns and pronouns, not a grammatical one.

この討論を経た後,さて,皆さんは異なるカテゴリー派,あるいは同一カテゴリー派のいずれでしょうか?

・ Aarts, Bas. "Syntactic Argumentation." Chapter 2 of The Oxford Handbook of English Grammar. Ed. Bas Aarts, Jill Bowie and Gergana Popova. Oxford: OUP, 2020. 21--39.

2022-08-25 Thu

■ #4868. 英語の意味を分析する様々なアプローチ --- 通信スクーリング「英語学」 Day 4 [english_linguistics][semantics][prototype][metaphor][metonymy][cognitive_linguistics][polysemy][voicy][2022_summer_schooling_english_linguistics][history_of_linguistics][lexicology][semantic_field]

言葉の意味とは何か? 言語学者や哲学者を悩ませ続けてきた問題です.音声や形態は耳に聞こえたり目に見えたりする具体物で,分析しやすいのですが,意味は頭のなかに収まっている抽象物で,容易に分析できません.言語は意味を伝え合う道具だとすれば,意味こそを最も深く理解したいところですが,意味の研究(=意味論 (semantics))は言語学史のなかでも最も立ち後れています(cf. 「#1686. 言語学的意味論の略史」 ([2013-12-08-1])).

しかし,昨今,意味を巡る探究は急速に深まってきています(cf. 「#4697. よくぞ言語学に戻ってきた意味研究!」 ([2022-03-07-1])).意味論には様々なアプローチがありますが,大きく伝統的意味論と認知意味論があります.スクーリングの Day 4 では,両者の概要を学びます.

1. 意味とは何か?

1.1 「#1782. 意味の意味」 ([2014-03-14-1])

1.2 「#2795. 「意味=指示対象」説の問題点」 ([2016-12-21-1])

1.3 「#2794. 「意味=定義」説の問題点」 ([2016-12-20-1])

1.4 「#1990. 様々な種類の意味」 ([2014-10-08-1])

1.5 「#2278. 意味の曖昧性」 ([2015-07-23-1])

2. 伝統的意味論

2.1 「#1968. 語の意味の成分分析」 ([2014-09-16-1])

2.2 「#1800. 様々な反対語」 ([2014-04-01-1])

2.3 「#1962. 概念階層」 ([2014-09-10-1])

2.4 「#4667. 可算名詞と不可算名詞とは何なのか? --- 語彙意味論による分析」 ([2022-02-05-1])

2.5 「#4863. 動詞の意味を分析する3つの観点」 ([2022-08-20-1])

3. 認知意味論

3.1 「#1961. 基本レベル範疇」 ([2014-09-09-1])

3.2 「#1964. プロトタイプ」 ([2014-09-12-1])

3.3 「#1957. 伝統的意味論と認知意味論における概念」 ([2014-09-05-1])

3.4 「#2406. metonymy」 ([2015-11-28-1])

3.5 「#2496. metaphor と metonymy」 ([2016-02-26-1])

3.6 「#2548. 概念メタファー」 ([2016-04-18-1])

4. 本日の復習は heldio 「#451. 意味といっても様々な意味がある」,およびこちらの記事セットより

2022-07-26 Tue

■ #4838. worth の形容詞的特徴 [adjective][preposition][pos][prototype][complementation][syntax]

昨日の記事「#4837. worth, (un)like, due, near は前置詞ぽい形容詞」 ([2022-07-25-1]) に引き続き,worth の品詞分類の問題について.Huddleston and Pullum (607) によると,まず worth が例外的な形容詞であるとの記述が見える.

As an adjective, . . . worth is highly exceptional. Most importantly for present purposes, it licenses an NP complement, as in The paintings are [worth thousands of dollars]. In this respect, it is like a preposition, but overall the case for analysing it as an adjective is strong.

では,Huddleston and Pullum は何をもって worth がより形容詞的だと結論づけているのだろうか.まず,機能的な特性として2点を指摘している.1つは,典型的な形容詞らしく become の補語になれるということ.もう1つは,(分詞構文的に)述語として機能できるということである.それぞれ以下の2つの例文によって示される,前置詞ではあり得ない芸当ということだ.

・ What might have been a $200 first edition suddenly became [worth perhaps 10 times that amount].

・ [Worth over a million dollars,] the jewels were kept under surveillance by a veritable army of security guards.

一方,比較変化および修飾という観点からみると,worth は形容詞らしくない.It was more worth the effort than I'd expected it to be. のような比較級の文は可能ではあるが,worth それ自体の意味について比較しているのかどうかについては議論がある.同様に,It was very much worth the effort. のように worth が強調されているかのような文はあり得るが,この強調は本当に worth の程度を強調しているのだろうか,議論があり得る.

もう1つ,精妙な統語論的な分析がある.worth が前置詞であれば関係代名詞の前に添えることができるが,形容詞であれば難しいと予想される.そして,その予想は当たっているのだ.

・ This was far less than the amount [which she thought the land was now worth].

・ *This was far less than the amount [worth which she thought the land was now].

上記を検討した上で総合的に評するならば,worth は典型的な形容詞とはいえず,前置詞的な特徴を持つものの,それでもどちらかといえば形容詞だ,ということになりそうだ.奥歯に物が挟まった言い方であることは承知しつつ.

・ Huddleston, Rodney and Geoffrey K. Pullum, eds. The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: CUP, 2002.

2022-07-25 Mon

■ #4837. worth, (un)like, due, near は前置詞ぽい形容詞 [adjective][preposition][pos][prototype][complementation][syntax]

先日 khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)内で,worth は形容詞か前置詞かという問題が議論された.歴史的には古英語の形容詞・名詞 w(e)orþ に遡ることが分かっているが,現代英語の worth を共時的に分析するならば,どちらの分析も可能である.

まず,「価値がある」という明確な語彙的な意味をもち,「価値」の意味をもつ対応する名詞もあることから,形容詞とみるのが妥当という意見がある.一方,後ろに原則として補語(目的語)を要求する点で前置詞のような振る舞いを示すことも確かだ.実際に,いくつかの英和辞書を参照すると,形容詞と取っているものもあれば,前置詞とするものもある.

一般に英語学では,このような問題を検討するのに prototype のアプローチを取る.典型的な形容詞,および典型的な前置詞に観察される言語学的諸特徴をあらかじめリストアップしておき,問題の語,今回の場合であれば worth について,どちらの品詞の特徴を多く有するかによって,より形容詞的であるとか,より前置詞的であるといった判断をくだすのである.

この分析自体がなかなかおもしろいのだが,当面は worth を,後ろに補語を要求するという例外的な特徴をもつ「異質な」形容詞とみておこう.Huddleston and Pullum (546--47) によれば,似たような異質な形容詞の仲間として (un)like と due がある.以下の例文で,角括弧に括った部分が,それぞれ補語を伴った形容詞句として分析される.

・ The book turned out to be [worth seventy dollars].

・ Jill is [very like her brother].

・ You are now [due $750]. / $750 is now [due you].

さらにこのリストに near も加えることができるだろう.

関連して「#947. 現代英語の前置詞一覧」 ([2011-11-30-1]),「#4436. 形容詞のプロトタイプ」 ([2021-06-19-1]),「#209. near の正体」 ([2009-11-22-1]) を参照.

品詞分類を巡る英語の問題としては,形容詞と副詞の区分を巡る議論も有名だ.これについては「#981. 副詞と形容詞の近似」 ([2012-01-03-1]),「#995. The rose smells sweet. と The rose smells sweetly.」 ([2012-01-17-1]),「#1354. 形容詞と副詞の接触点」 ([2013-01-10-1]),「#2441. 副詞と形容詞の近似 (2) --- 中英語でも困る問題」 ([2016-01-02-1]) などを参照.

・ Huddleston, Rodney and Geoffrey K. Pullum, eds. The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: CUP, 2002.

2021-11-02 Tue

■ #4572. 「他動詞」「自動詞」という用語について [verb][terminology][prototype]

常々考えており,学生たちともよく議論していることなのだが,「他動詞」 (transitive verb) と「自動詞」 (intransitive verb) という用語は紛らわしい.

ある動詞のことを「他動詞」か「自動詞」かに分類するよりも,その動詞には「他動詞的用法」 (transitive use) があるとか,「自動詞的用法」 (intransitive use) があるとか,両用法があるとか,そのような用語使いのほうが分かりやすいのではないかと思うからだ.

確かに,通常は自動詞的用法しかもたない exist, fall, matter のような動詞を「自動詞」と呼んでおくのは一見すると分かりやすいし,同様に普通は他動詞的用法しかもたない greet, have, visit のような動詞を「他動詞」と称するのは問題ないように思われる.しかし,eat, write, move など大多数の動詞が実は両用法をもつのであり,これらの動詞を個々の具体的な文脈における用法に注目せず,所属タイプとして「他動詞」や「自動詞」と分類してしまうのは適切ではない.eat は基本的には「他動詞」だが,場合によっては目的語が省略され「自動詞」ともなり得る,というような言い方は混乱のもとである.

似たようなことは「可算名詞」 (countable noun) や「不可算名詞」 (uncountable noun or mass noun) についても言えるし,「限定形容詞」 (attributive adjective) や「叙述形容詞」 (predicative adjective) についても言えるだろう.これらの用語は,動詞,名詞,形容詞のタイプとしての「種別」を表わす用語ではなく,具体的に実現されるトークンとしての「用法」を表わす用語と解釈しておくのが妥当に思われる.

タイプ種別として A か B かに厳密にカテゴライズできないのは,言語(学用語)の常である.およそA的だがB的な要素もあるとか,状況に応じてA的にもB的にもなり得るとか,そのようなケースのほうが多い.言語事象も言語学用語もたいていプロトタイプ (prototype) の観点からみておくのがよい.

このような問題を考察したい方は,ぜひ Taylor をどうぞ.さらにこちらも「#1258. なぜ「他動詞」が "transitive verb" なのか」 ([2012-10-06-1]) .

・ Taylor, John R. Linguistic Categorization. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 2003.

2021-06-19 Sat

■ #4436. 形容詞のプロトタイプ [comparison][adjective][adverb][category][prototype][pos][comparison]

品詞 (part of speech = pos) というものは,最もよく知られている文法範疇 (category) の1つである.たいていの言語学用語なり英文法用語なりは,文法範疇につけられたラベルである.主語,時制,数,格,比較,(不)可算,否定などの用語が出てきたら,文法範疇について語っているのだと考えてよい.

英語の形容詞(および副詞)という品詞について考える場合,比較 (comparison) という文法範疇が話題の1つとなる.日本語などでは「比較」を文法範疇として特別扱いする慣習はなく,せいぜい格助詞「より」の用法の1つとして論じられる程度だが,印欧語族においては言語体系に深く埋め込まれた文法範疇として,特別視されることになっている.私はいまだにこの感覚がつかめていないのだが,英語学において比較という文法範疇が通時的にも共時的にも重要視されてきたことは確かである.

比較はまずもって形容詞(および副詞)の文法範疇ということだが,ある語が形容詞であるからといって,必ずしもこの範疇が関与するわけではない.本当に形容詞らしい形容詞は比較の範疇に適合するが,さほど形容詞らしくない形容詞は比較とは相容れない.逆に見れば,ある形容詞を取り上げたとき,比較の範疇に適合するかどうかで,形容詞らしい形容詞か,そうでもない形容詞かが判明する.これは,とりもなおさず形容詞に関するプロトタイプ (prototype) の問題である.

Crystal (92) が,形容詞のプロトタイプについて分かりやすい説明を与えてくれている.

The movement from a central core of stable grammatical behaviour to a more irregular periphery has been called gradience. Adjectives display this phenomenon very clearly. Five main criteria are usually used to identify the central class of English adjectives:

(A) they occur after forms of to be, e.g. he's sad;

(B) they occur after articles and before nouns, e.g. the big car;

(C) they occur after very, e.g. very nice;

(D) they occur in the comparative or superlative form e.g. sadder/saddest, more/most impressive; and

(E) they occur before -ly to form adverbs, e.g. quickly.

We can now use these criteria to test how much like an adjective a word is. In the matrix below, candidate words are listed on the left, and the five criteria are along the top. If a word meets a criterion, it is given a +; sad, for example, is clearly an adjective (he's sad, the sad girl, very sad, sadder/saddest, sadly). If a word fails the criterion, it is given a - (as in the case of want, which is nothing like an adjective: *he's want, *the want girl, *very want, *wanter/wantest, *wantly).

A B C D E happy + + + + + old + + + + - top + + + - - two + + - - - asleep + - - - - want - - - - -

The pattern in the diagram is of course wholly artificial because it depends on the way in which the criteria are placed in sequence; but it does help to show the gradual nature of the changes as one moves away from the central class, represented by happy. Some adjectives, it seems, are more adjective-like than others.

形容詞という文法範疇について,特にその比較という文法範疇については,以下の記事を参照.

・ 「#3533. 名詞 -- 形容詞 -- 動詞の連続性と範疇化」 ([2018-12-29-1])

・ 「#3835. 形容詞などの「比較」や「級」という範疇について」 ([2019-10-27-1])

・ 「#3843. なぜ形容詞・副詞の「原級」が "positive degree" と呼ばれるのか?」 ([2019-11-04-1])

・ 「#3844. 比較級の4用法」 ([2019-11-05-1])

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge: CUP, 1995. 2nd ed. 2003. 3rd ed. 2019.

2021-06-11 Fri

■ #4428. hedge と prototype の関係 [hedge][prototype][semantics][pragmatics][logic]

連日「#4426. hedge」 ([2021-06-09-1]) と「#4427. 様々な hedge および関連表現」 ([2021-06-10-1]) のように hedge の話題を取り上げている.今回も Lakoff の論文を参照して考察を続けたい.

論文を読んで hedge の理解が変わってきた.昨日の記事の最後でも述べたが,単なる「ぼかし言葉」ではなく「ある命題を真たらしめる条件を緩く指定・制限する方略」と理解すべきだろう.少なくとも Lakoff の考える hedge はそのようなものらしい.そうすると,議論は必然的に意味論から語用論の方面に広がっていくことになるだろうし,意味に関する検証主義という言語哲学の問題にもつながっていきそうだ.

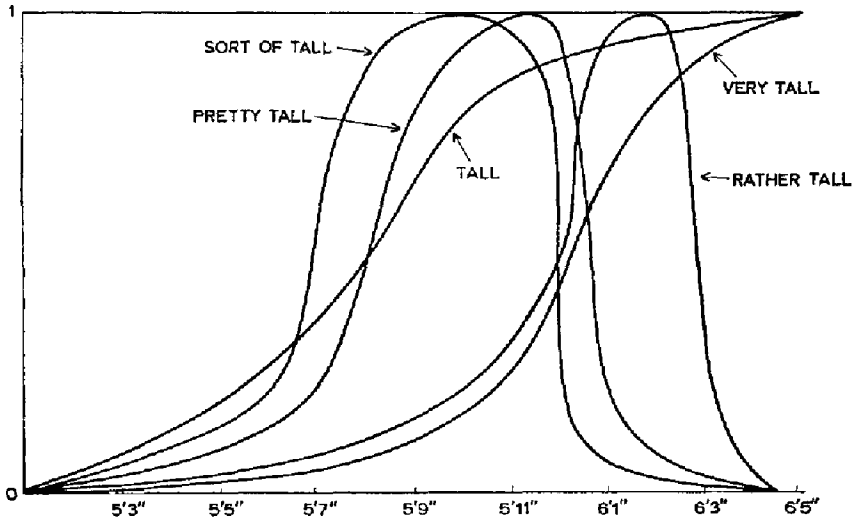

hedge と prototype の深い関係も明らかになった.例えば,sort of という hedge は,プロトタイプから少々逸脱したものを許容する方向に作用する意味論・語用論上の「関数」とみることができる.実際,Lakoff はファジー集合を提唱した Lofti Zadeh の研究よりインスピレーションを受け,論理学・代数学的な関数を利用して tall, very tall, sort of tall, pretty tall, rather tall の意味分析を行なっている.Lakoff 論文 (482) より,以下の図を見てもらいたい.

この図の見方は次の通りだ.「ある人が tall, very tall, sort of tall, pretty tall, rather tall である」という命題がある場合,実際にどれくらいの背の高さであれば,その命題は真であると考えられるかについて多数の人にアンケートを取った結果のサマリーと読める.つまり,5'3" (5フィート3インチ≒160cm)で tall とみなす回答者はほぼ0%だろうが,6'3" (6フィート3インチ≒190cm)であればほぼ100%の回答者が tall を妥当な形容詞とみなすだろう.6'3" であれば,very tall ですら100%に近い高い値を示すだろう.しかし,rather tall は 6'3" に対しては,大方かえって不適切な表現と判断されるだろう,等々.

要するに,5種類の表現に対して描かれた各曲線の形状が,その表現の hedge としての効果である,と解釈できる.これらは曲線であるから,代数的には関数として表現できることになる.もちろん Lakoff とて何らかの定数を与えた厳密な意味での関数の立式を目指しているわけではないのだが,hedge と prototype の関係がよく分かる考え方ではある.

この点について Lakoff 自身の要約 (492--93) を引用しておこう.

6.5. Algebraic Functions Play a Role in the Semantics of Certain Hedges

Hedges like SORT OF, RATHER, PRETTY, and VERY change distribution curves in a regular way. Zadeh has proposed that such changes can be described by simple combinations of a small number of algebraic functions. Whether or not Zadeh's proposals are correct in all detail, it seems like something of the sort is necessary. . . .

6.6. Perceptual Finiteness Depends on an Underlying Continuum of Values

Since people can perceive, for each category, only a finite number of gradations in any given context, one might be tempted to suggest that fuzzy logic be limited to a relatively small finite number of values. But the study of hedges like SORT OF, VERY, PRETTY, and RATHER, whose effect seems to be characterizable at least in part by algebraic functions, indicates that the number and distribution of perceived values is a surface matter, determined by the shape of underlying continuous functions. For this reason, it seems best not to restrict fuzzy logic to any fixed finite number of values. Instead, it seems preferable to attempt to account for the perceptual phenomena by trying to figure out how, in a perceptual model, the shape of underlying continuous functions determines the number and distribution of perceived values.

いつの間にかファジー集合という抜き差しならない領域にまで到達してしまったが,そもそも hedge =「ぼかし(言葉)」という認識から始まったわけなので,遠く離れていないようにも思えてきた.

・ Lakoff, G. "Hedges: A Study in Meaning Criteria and the Logic of Fuzzy Concepts." Journal of Philosophical Logic 2 (1973): 458--508.

2021-06-10 Thu

■ #4427. 様々な hedge および関連表現 [hedge][prototype][semantics][pragmatics][intensifier]

昨日の記事で「#4426. hedge」 ([2021-06-09-1]) を取り上げた.英語についていえば sort of が hedge の代表例として挙げられることが多いが,実際のところ hedge の種類は多様である.

昨日の引用文で触れた Lakoff の論文を読んだ.p. 472 に "SOME HEDGES AND RELATED PHENOMENA" と題する表が掲げられている.英語の hedge (関連)表現の具体例として,以下に掲載しておこう.

sort of

kind of

loosely speaking

more or less

on the _____ side (tall, fat, etc.)

roughly

pretty (much)

relatively

somewhat

rather

mostly

technically

strictly speaking

essentially

in essence

basically

principally

particularly

par excellence

largely

for the most part

very

especially

exceptionally

quintessential(ly)

literally

often

more of a _____ than anything else

almost

typically/typical

as it were

in a sense

in one sense

in a real sense

in an important sense

in a way

mutatis mutandis

in a manner of speaking

details aside

so to say

a veritable

a true

a real

a regular

virtually

all but technically

practically

all but a

anything but a

a self-styled

nominally

he calls himself a ...

in name only

actually

really

(he as much as ...

-like

-ish

can be looked upon as

can be viewed as

pseudo-

crypto-

(he's) another (Caruso/Lincoln/ Babe Ruth/...)

_____ is the _____ of _____ (e,g., America is the Roman Empire of the modern world. Chomsky is the DeGaulle of Linguistics. etc.)

一覧して分かるように,「#4236. intensifier の分類」 ([2020-12-01-1]) で挙げた広い意味での強意語 (intensifier) は,いずれも hedge の一種とみなすことができる.これまで hedge を単純に「ぼかし言葉」くらいに認識していたが,そうでもないことが分かってきた.ある命題を真たらしめる条件を緩く指定・制限する方略と理解しておくのがよさそうだ.

・ Lakoff, G. "Hedges: A Study in Meaning Criteria and the Logic of Fuzzy Concepts." Journal of Philosophical Logic 2 (1973): 458--508.

2021-06-09 Wed

■ #4426. hedge [hedge][pragmatics][terminology][cooperative_principle][prototype][sociolinguistics][cognitive_linguistics][semantics]

hedge (hedge) は,語用論の用語・概念として広く知られている.一般用語としては「垣根」を意味する単語だが,そこから転じて「ぼかし言葉」を意味する.日本語の得意技のことだと言ったほうが分かりやすいだろうか.

『ジーニアス英和辞典』によると「(言質をとられないための)はぐらかし発言,ぼかし語句;〔言語〕語調を和らげる言葉,ヘッジ《◆I wonder, sort of など》.」とある.

また,Cruse の意味論・語用論の用語集を引いてみると,たいへん分かりやすい説明が与えられていた.

hedge An expression which weakens a speaker's commitment to some aspect of an assertion:

She was wearing a sort of turban.

To all intents and purposes, the matter was decided yesterday.

I've more or less finished the job.

As far as I can see, the plan will never succeed.

She's quite shy, in a way.

述べられている命題に関して,それが真となるのはある条件の下においてである,と条件付けをしておき,後に批判されるのを予防するための言語戦略といってよい.一般には「#1122. 協調の原理」 ([2012-05-23-1]) を破ってウソを述べるわけにもいかない.そこで言葉を濁すことによって,言質を与えない言い方で穏便に済ませておくという方略である.これは私たちが日常的に行なっていることであり,日本語に限らずどの言語においてもそのための手段が様々に用意されている.

私も hedge という用語を上記のような語用論的な意味で理解していたが,言語学用語としての hedge はもともと認知意味論の文脈,とりわけ prototype 理論の文脈で用いられたものらしい.Bussmann の用語集から引こう (205) .

hedge

Term introduced by Lakoff (1973). Hedges provide a means for indicating in what sense a member belongs to its particular category. The need for hedges is based on the fact that certain members are considered to be better or more typical examples of the category, depending on the given cultural background (→ prototype). For example, in the central European language area, sparrows are certainly more typical examples of birds than penguins. For that reason, of these two actually true sentences, A sparrow is a bird and A penguin is a bird, only the former can be modified by the hedge typical or par excellence, while the latter can be modified only by the hedges in the strictest sense or technically speaking.

この言語学用語自体が,この半世紀の間,意味合いを変えながら発展してきたということのようだ.ところで,個人的には hedge という用語はどうもしっくりこない.なぜ「垣根」?

・ Cruse, Alan. A Glossary of Semantics and Pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2006.

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

・ Lakoff, G. "Hedges: A Study in Meaning Criteria and the Logic of Fuzzy Concepts." Journal of Philosophical Logic 2 (1973): 458--508.

2021-02-02 Tue

■ #4299. Trier の「意味の場」の理論的限界 [semantics][semantic_field][prototype][cognitive_linguistics]

「#4293. Trier の「意味の場」の言語学史上の意義 (1)」 ([2021-01-27-1]),「#4294. Trier の「意味の場」の言語学史上の意義 (2)」 ([2021-01-28-1]) で Trier の「意味の場」について紹介してきた.後者の記事の最後で,Trier の構造主義的な「場の理論」があまりに理想主義的であり,現実の語彙にきれいに適用できるものではないという評価に触れた.

実際,後に展開した意味論の成分分析 (componential analysis) は,Trier の「意味の場」が現実離れした概念であることを示した.語の意味とは,確かに構造的な側面もあるが,それ以外にも多様な側面をもっているのだ.

Trier の理論的限界を指摘する評価を,『新英語学辞典』の field の項より引用したい (434) .

場の内部構造に関しては,初期の頃は,Trier の有名な「モザイク模様」のたとえにも見られるように,ある決まった概念分野を幾つかの語が隙間もなく,また重なりもなく完全に覆っているといった理想像が描かれていた.このようなイメジは,後に Trier 自身をも含めて放棄され,代わって,場を構成する個々の語はその意味の周辺部では他の語の意味範囲との重複や交差があり,一つの場自体の境界も明確な線としてではなく,他の隣接する場への緩やかな移行という形で受け取られるようになった.また,語の意味はそれを場の中に位置づけることによってのみわかるという強い形での主張や,場からある語が失われたり,ある語がそこへ新しく入ってきた場合,その場に属するすべての語がその影響を受けるというような考え方も現在ではやや理想的にすぎるとされている.さらに,場はその術語から想像されがちなように平板的な構造を有している場合のみとは限らず,例えば親族用語などに照らしても明らかなように,幾つかの対立の次元に基づいて多元的な構造を有しているという点についても意見の一致が得られているようである.意味の成分分析 (COMPONENTIAL ANALYSIS) の研究が進むにつれて,その観点から伝統的な「場」の概念に新しい規定の道が開かれるものと予想される.

とはいえ,Trier に端を発する構造言語学的な語彙・意味の分析は,英語史や英語学の入門書・入門講義ではまだまだ取り上げられることも多いのではないだろうか.図式的できれいに説明できるので,手放しがたいものと思われる.しかし,現代の意味論,とりわけ認知意味論では,むしろ意味の区画は整然としていないことを前提とする prototype の見方が主流であり,Trier 流のガチガチの構造主義的意味論は肩身が狭い.したがって,現代的にいえば,Trier の「意味の場」の理論的限界は明らかだろう.

それでも,言語学史的にみれば,いきなりファジーな prototype を持ち出されるよりは,ガチガチの構造主義的な「意味の場」のほうが,ずっと分かりやすかったのも事実である.まずきっちりした区画が前提としてあり,その後,現実はもっとファジーなものなのだと再解釈を促される,という順序で教えられたほうが,よほど理解しやすいのである.やはり,Trier の「意味の場」は大きな学史的な意義を有すると思う.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2020-07-17 Fri

■ #4099. sore の意味変化 [cognitive_linguistics][semantic_change][metaphor][metonymy][loan_word][french][prototype][polysemy]

Geeraerts による,英語史と認知言語学 (cognitive_linguistics) のコラボを説く論考より.本来語 sore の歴史的な意味変化 (semantic_change) を題材にして,metaphor, metonymy, prototype などの認知言語学的な用語・概念と具体例が簡潔に導入されている.

現代英語 sore の古英語形である sār は,当時よりすでに多義だった.しかし,古英語における同語の prototypical な語義は,頻度の上からも明らかに "bodily suffering" (肉体的苦しみ)だった.この語義を中心として,それをもたらす原因としての外科的な "bodily injury, wound" (傷)や内科的な "illness" (病気)の語義が,メトニミーにより発達していた.一方,"emotional suffering" (精神的苦しみ)の語義も,肉体から精神へのメタファーを通じて発達していた.このメタファーの背景には,語源的には無関係であるが形態的に類似する sorrow (古英語 sorg)との連想も作用していただろう.

古英語 sār が示す上記の多義性は,以下の各々の語義での例文により示される (Geeraerts 622) .

(1) "bodily suffering"

þisse sylfan wyrte syde to þa sar geliðigað (ca. 1000: Sax.Leechd. I.280)

'With this same herb, the sore [of the teeth] calms widely'

(2) "bodily injury, wound"

Wið wunda & wið cancor genim þas ilcan wyrte, lege to þam sare. Ne geþafað heo þæt sar furður wexe (ca. 1000: Sax.Leechd. I.134)

'For wounds and cancer take the same herb, put it on to the sore. Do not allow the sore to increaase'

(3) "illness"

þa þe on sare seoce lagun (ca. 900: Cynewulf Crist 1356)

'Those who lay sick in sore'

(4) "emotional suffering"

Mið ðæm mæstam sare his modes (ca. 888: K. Ælfred Boeth. vii. 則2)

'With the greatest sore of his spirit

このように,古英語 sār'' は,あくまで (1) "bodily suffering" の語義を prototype としつつ,メトニミーやメタファーによって派生した (2) -- (4) の語義も周辺的に用いられていたという状況だった.ところが,続く初期中英語期の1297年に,まさに "bodily suffering" を意味する pain というフランス単語が借用されてくる.長らく同語義を担当していた本来語の sore は,この新参の pain によって守備範囲を奪われることになった.しかし,死語に追いやられたわけではない.prototypical な語義を (1) "bodily suffering" から (2) "bodily injury, would" へとシフトさせることにより延命したのである.そして,後者の語義こそが,現代英語 sore の prototype となった(他の語義が衰退し,この現代的な状況が明確に確立したのは近代英語期).

・ Geeraerts, Dirk. "Cognitive Linguistics." Chapter 59 of A Companion to the History of the English Language. Ed. Haruko Momma and Michael Matto. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. 618--29.

2018-12-29 Sat

■ #3533. 名詞 -- 形容詞 -- 動詞の連続性と範疇化 [prototype][category][pos][noun][verb][adjective][typology][conversion]

大堀 (70) は,語彙カテゴリー(いわゆる品詞)の問題を論じながら,名詞 -- 形容詞 -- 動詞の連続性に注目している.一方の極に安定があり,他方の極に移動・変化がある1つの連続体という見方だ.

語彙カテゴリーが成り立つ基盤は,知覚の上で不変の対象と,変化をともなう過程との対立に見出すことができる.つまり,一方では時間の経過の中で安定した対象があり,もう一方ではその移動や変化の過程が知覚される.こうした対立をもとに考えると,名詞のプロトタイプは,変化のない安定した特性をもった対象である.指示を行うためには,明瞭な輪郭をもち,恒常性のある物体であることが基本となる.これに対し,動詞のプロトタイプは,状態の変化という特性をもった過程である.叙述を行うのは,際立った変化がみとめられた場合が主であり,それは典型的には行為の結果として現れるからである.談話の中での機能という点からこれを見れば,「名詞らしさ」は談話内で一定の対象を続けて話題にするための安定した背景を設け,「動詞らしさ」は時間の中での変化によって起きる事態の進行を表すはたらきをもつ.

このように考えると,類型論的に形容詞が名詞らしさと動詞らしさの間で「揺れ」を示す,あるいは自立したカテゴリーとしては限られたメンバーしかもたないことが多いという点は,形容詞がもつ用法上の特性から説明されると思われる.形容詞は修飾的用法(例:「赤いリンゴ」)と叙述的用法(例:「リンゴは赤い」)を両方もっており,前者は対象の特定を通じて「名詞らしさ」の側に,後者は(行為ではないが)性質についての叙述を通じて「動詞らしさ」の側に近づくからである.そして概念的にプロトタイプから外れたときには,名詞や動詞からの派生によって表されることが多くなる.

形容詞が名詞と動詞に挟まれた中間的な範疇であるがゆえに,ときに「名詞らしさ」を,ときに「動詞らしさ」を帯びるという見方は説得力がある.その違いが,修飾的用法と叙述的用法に現われているのではないかという洞察も鋭い.また,言語類型論的にいって,形容詞というカテゴリーは語彙数や文法的振る舞いにおいて言語間の異なりが激しいのも,中間的なカテゴリーだからだという説明も示唆に富む(例えば,日本語では形容詞は独立して述語になれる点で動詞に近いが,印欧諸語では屈折形態論的には名詞に近いと考えられる).

上のように連続性と範疇化という観点から品詞をとらえると,品詞転換 (conversion) にまつわる意味論やその他の傾向にも新たな光が当てられるかもしれない.

・ 大堀 壽夫 『認知言語学』 東京大学出版会,2002年.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow