2019-01-01 Tue

■ #3536. one, once, none, nothing の第1音節母音の問題 [vowel][phonetic_change][phonetics][indefinite_pronoun][pronoun][personal_pronoun]

明けましておめでとうございます.このブログも足かけ11年目に突入しました.平成も終わりに近づいていますが,来たるべき時代にかけても,どうぞよろしくお願い申し上げます.

新年一発目は,ある意味で難しい話題.最近,<o .. e> ≡ /ʌ/ の問題について「#3513. come と some の綴字の問題」 ([2018-12-09-1]) で触れた.その際に,one, none などにも触れたが,それと関連する once とともに,この3語は実に複雑な歴史をもっている.「#86. one の発音」 ([2009-07-22-1]),「#89. one の発音は訛った発音」 ([2009-07-25-1]) でも,現代に至る経緯は簡単に述べたが,詳しく調べると実に複雑な歴史的経緯があるようだ.母音の通時的変化と共時的変異が解きほぐしがたく絡み合って発達してきたようで,単純に説明することはできない.ということで,中尾 (207) の解説に丸投げしてしまいます.

one/none/once: ModE では [ū?ō?ɔː?ɔ] の交替をしめす.史的発達からいえば PE [oʊ] が期待される.事実 only (<ānlic/alone (<eall ān)/atone にはそれが反映されている.PE の [ʌ] をもつ例えば [wʌn] はすでに16--17世紀にみられるが,これは方言的または卑俗的であり,1700年まで StE には受けられていない.しかしそのころから [oːn] を置換していった.

上述3語の PE [ʌ] の発達はつぎのようであったと思われる.すなわち,OE ɑːn > ME ɔːn,方言的上げ過程 . . . を受け [oːn] へ上げられた.語頭に渡り音 [w] が挿入され (cf. Hart の wonly) . . . woːn > (GVS) uː > (短化 . . .) ʊ > (非円唇化) ʌ へ到達する . . . .

この解釈では,語頭への w 挿入により上げを経てきた歴史にさらに上げが上乗せされ,ついに高母音になってしまったというシナリオが想定されている.いずれにせよ,方言発音の影響という共時的な側面も相俟って,単純には説明できない発音の代表格といっていいのかもしれない.

なお,上では one, none, once の3語のみが注目されていたが,このグループに関連語 nothing (< nā(n) þing) も付け加えておきたい.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

2018-12-23 Sun

■ #3527. 呼称のポライトネスの通時変化,代名詞はネガティヴへ,名詞はポジティヴへ [address_term][politeness][t/v_distinction][emode][title][honorific][face][personal_pronoun][solidarity]

椎名 (65--72) は,1640--1760年までの gentry comedy を含むコーパスで,呼称 (address_term) の表現を調査した.

呼称は,大きく negative politeness を指向する "deferential type" と positive politeness を指向する "familiar type" に区分される.これは,2人称代名詞でいえば you と thou の区別に相当し,名詞(句)でいえば,たとえば Lord と dear の区別に相当する (cf. 「#2131. 呼称語のポライトネス座標軸」 ([2015-02-26-1])) .歴史的な事実としておもしろいのは,代名詞と名詞(句)の呼称の変化に関して,調査された初期近代英語期から,その後の後期近代英語期および現代英語期にかけて,傾向が異なっていることだ.代名詞では,よく知られているように negative politeness が重視されたかのように thou ではなく you が一般化した.ところが,名詞(句)では,むしろ dear や名前 (first name) での呼びかけのように positive politeness が重視されて,現在に至っている.椎名 (69) の指摘するとおり,「nominal address terms の変化の方向が pronominal address terms の変化の方向と逆だということ」である.

2人称代名詞に関して,なぜ thou ではなく you の方向で一般化したのかについては,「#1127. なぜ thou ではなく you が一般化したか?」 ([2012-05-28-1]),「#1336. なぜ thou ではなく you が一般化したか? (2)」 ([2012-12-23-1]) で話題にしてきたが,ここに新たな論点が加わったように思われる.つまり,なぜ名詞(句)の呼びかけ表現では,むしろ親密 (familiarity) や団結 (solidarity) を示す方向が選択されたのか.これは偶然だろうか.あるいは総合的なバランスということだろうか.

・ 椎名 美智 「第3章 歴史語用論における文法化と語用化」『文法化 --- 新たな展開 ---』秋元 実治・保坂 道雄(編) 英潮社,2005年.59--74頁.

2018-11-28 Wed

■ #3502. pronoun exchange [personal_pronoun][case][prescriptive_grammar][dialectology][shakespeare]

人称代名詞について,文法的に目的格が求められるところで主格の形態が用いられたり,その逆が起こったりするケースを pronoun exchange と呼ぶ.最も有名なのは「#301. 誤用とされる英語の語法 Top 10」 ([2010-02-22-1]) でトップに輝いた between you and I である.前置詞に支配される位置なので1人称代名詞には目的格の me が適格だが,前置詞から少々離れているということもあり,ついつい I といってしまう類いの「誤用」である.

しかし,誤用とはいっても,それは規範文法が確立した後期近代英語以後の言語観に基づく発想である.それ以前の時代には「正誤」の問題ではなく,いずれの表現も許容されていたという意味において「代替表現」にすぎなかった.実際,よく知られているように Shakespeare も Sweet Bassanio, ... all debts are cleared between you and I if I might but see you at my death. (The Merchant of Venice iii.ii) のように用いているのである.同様に,Yes, you have seen Cassio and she together. (Othello iv. ii) などの例もある.

古い英語のみならず,現代の非標準諸方言でも,pronoun exchange はありふれた現象である.Gramley (196) を引用する.

Pronoun exchange, in which case is reversed, is widespread (SW, Wales, East Anglia, the North). This refers to the use of the subject pronoun for the object: They always called I "Willie," see; you couldn't put she [a horse] in a putt.. The converse is also possible. Compare 'er's shakin' up seventy; . . . what did 'em call it?; Us don't think naught about things like that. Subject forms are much more common as objects than the other way around (55% to 20%) . . . . In the North second person thou/thee often shows up as leveled tha in traditional dialects . . ., but not north of the Tyne or in Northumberland . . . . Today pronoun exchange is generally receding.

引用で触れられている thou/thee については,拙論の連載 第10回 なぜ you は「あなた」でもあり「あなたがた」でもあるのか?の方言地図も参照されたい.同様に,she と er (< her) の pronoun exchange の例については,「#793. she --- 現代イングランド方言における異形の分布」 ([2011-06-29-1]) の方言地図を参照.

考えてみれば,そもそも現代標準英語でも,2人称(複数)代名詞の主格の you は歴史的には pronoun exchange の例だったのである.you はもとは目的格の形態にすぎず,主格の形態は ye だったが,前者 you が主格のスロットにも侵入してきたために,後者 ye が追い出されてしまったという歴史だ.これについては「#781. How d'ye do?」 ([2011-06-17-1])「#800. you による ye の置換と phonaesthesia」 ([2011-07-06-1]),「#2077. you の発音の歴史」 ([2015-01-03-1]) を参照.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

2018-11-27 Tue

■ #3501. 1552年と1662年の祈祷書の文法比較 [book_of_common_prayer][bible][emode][3sp][personal_pronoun][t/v_distinction][relative_pronoun][be][language_change]

1549年,Thomas Crammer の編纂した The Book of Common Prayer (祈祷書)が世に出た.1552年には,その改訂版が出されている.この祈祷書の引用元となっているのは1539年の the Great Bible である.一方,およそ1世紀後,王政復古期の1662年に,別版の祈祷書が出版された.現在も一般に用いられているこちらの新版は,1611年の the King James Bible に基づいており,言語的にはむしろ保守的である.つまり,1552年版と1662年版の祈祷書を比べてみると,後者のほうが年代としては100年余り遅いにもかかわらず,言語的には前者よりも古い特徴を示すことがあるということだ.ただし,全部が全部そうなのではなく,後者が予想通り,より新しい特徴を示している例もあり複雑だ.

Gramley (144) は,Nevalainen (1998) の研究を参照しながら,5点の文法項目を比較している.

| feature | 1552 | 1662 |

|---|---|---|

| 3rd person singular ending | mixed {-th} and {-s} | reversion to {-th} |

| 2nd person singular personal | thou/thee but some ye/you | largely a return to thou/thee |

| nominative ye/you | both ye and you | largely a return to ye |

| nominative which/who | 56 who vs. 129 which | 172 who vs. 13 which |

| present tense plural be/are | 52 are vs. 105 be | 125 are vs. 32 be |

最初の3点は1662年版のほうがむしろ古風な特徴を保持しているケース,最後の2点は時代に即した分布を示しているようにみえるケースだ.2つのケースの違いは,前者が意識的な変化 ("change from above") の結果であり,後者が無意識的な変化 ("change from below") の結果であるとして説明することができるかもしれない.口頭の発話が意図されている文脈ではより新しい語法が用いられているという報告もあるので,おそらく文体の問題と1世紀の間の言語変化の問題とが複雑に絡み合って,それぞれの表現が選ばれているのだろう.聖書を用いた通時言語学的比較は,おおいに注意を要する作業である.

祈祷書については,「#745. 結婚の誓いと wedlock」 ([2011-05-12-1]),「#1803. Lord's Prayer」 ([2014-04-04-1]),「#2738. Book of Common Prayer (1549) と King James Bible (1611) の画像」 ([2016-10-25-1]),「#2597. Book of Common Prayer (1549)」 ([2016-06-06-1]) を参照.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

・ Nevalainen, T. "Change from Above. A Morphosyntactic Comparison of Two Early Modern English Editions of The Book of Common Prayer." A Reader in Early Modern English. Ed. M. Rydé, I. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, and M. Kytö. Frankfurt: Lang, 165--86.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2018-11-21 Wed

■ #3495. Jespersen による滲出の例 [terminology][personal_pronoun][article]

「#3480. 膠着と滲出」 ([2018-11-14-1]) で,burger の「滲出」の例をみた.「滲出」を形態論上の問題として論じた Jespersen (384) は,次のように定義している.

By secretion I understand the phenomenon that one integral portion of a word comes to acquire a grammatical signification which it had not at first, and is then felt as something added to the word itself. Secretion thus is a consequence of a 'metanalysis' . . .; it shows its full force when the element thus secreted comes to be added to other words not originally possessing this element.

Jespersen は「滲出」の例として文法的なケースを念頭においていたようで,理解するのは意外と難しい.「滲出」の "a clear instance" として,所有代名詞 mine から n が滲出したケースを挙げているので,それを以下に解説する.

古英語では min, þin の n は語の一部であり,それ自体は特に有意味な単位ではなかった.しかし,中英語になると,後続音との関係で n の脱落する例が現われてきた.つまり,子音の前位置では n が保たれたものの,母音の前位置で n が消失する事例が増えてきた.一方,単独で「?のもの」を意味する所有代名詞として用いられる場合には,語源的な n は消えずに mine, thine などとして存続した.この段階になって,純粋に音韻的だった対立が機能的な対立へと転化され,現代的な my と mine, thy と thine の使い分けが発達することになった(関連して,不定冠詞 a と an の分化を扱った「#831. Why "an apple"?」 ([2011-08-06-1]) も参照).

さて,my, thy は上記の通り,歴史的には mine, thine の語の一部である n が脱落した結果の形ではあるが,my, thy がデフォルトの所有格と理解されるに及び,むしろそれに n を付加したものが mine, thine であるととらえられるようになった.つまり,n がどこからともなく,ある種の機能を帯びた音韻・形態として切り取られることになったのである.いったんこのような「有意味な」 n が切り取られて独立すると,これが他の数・人称・性の代名詞の所有格にも付加され,新たな所有代名詞 hisn, hern, ourn, yourn, theirn (ただし現代では非標準的)が生み出されることになった.これらは,明らかに n が「滲出」した証拠と理解することができる.

これらの -n を語尾にもつ所有代名詞については,「#2734. 所有代名詞 hers, his, ours, yours, theirs の -s」 ([2016-10-21-1]),「#2737. 現代イギリス英語における所有代名詞 hern の方言分布」 ([2016-10-24-1]) を参照.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Language: Its Nature, Development, and Origin. 1922. London: Routledge, 2007.

2018-11-06 Tue

■ #3480. 人称とは何か? (3) [person][category][personal_pronoun][deixis][title][pidgin][fetishism]

標題は,[2018-10-20-1], [2018-10-25-1]の記事の続編.『新英語学辞典』と The Oxford Companion to the English Language より, (人称)という用語を引くと,興味深い情報が得られた.英語の人称代名詞の用法の詳細についての話題が主となるが「人称」というフェチ的世界観の奥深さが垣間見える.いくつかを挙げよう.

・ Well, and how are we today? などにおける「親身の we」 (paternal we) は,1人称(複数)というよりも「総称人称」 (generic person) あるいは「共通人称」というべき.as we know なども同様.

・ 人称の指示対象と人称の文法上の振る舞いは異なる:たとえば the (present) writer, the author, the speaker などは,指示対象は1人称だが,文法上は3人称である.同様に your Majesty, your Excellency なども指示対象は2人称だが,文法上は3人称である.Does His Majesty wish to leave? や Does Madam wish to look at some other hats? などを参照.関連して「#440. 現代に残る敬称の you」 ([2010-07-11-1]) も.

・ 逆に,Mother, where are you? のような呼びかけでは,3人称的な名詞を用いながらも,2人称的色彩が濃厚.

・ 各種の Pidgin English では "inclusive" な1人称複数 yumi (< "you-me") と,"exclusive" な1人称複数 mipela (< "me-fellow") が区別される (cf. 「#1313. どのくらい古い時代まで言語を遡ることができるか」 ([2012-11-30-1])) .

・ royal we という,きわめてイギリスらしい慣習.Victoria 女王による We are not amused. (← 一生に1度でも言ってみたい)を参照.

・ 日本語「こそあ(ど)」は各々1,2,3人称に対応すると考えられる.(← なるほど)

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄 監修 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1987年.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

2018-10-25 Thu

■ #3468. 人称とは何か? (2) [person][category][personal_pronoun][agreement][t/v_distinction][deixis][sobokunagimon]

人称 (person) について,先日「#3463. 人称とは何か?」 ([2018-10-20-1]) で私見を述べた.より客観的に言語における人称を考えていくに当たって,まずは言語学用語辞典で person を引いてみよう.以下,Crystal (358--59) の記述より.

person (n.) (per, PER) A category used in grammatical description to indicate the number and nature of the participants in a situation. The contrasts are deictic, i.e. refer directly to features of the situation of utterance. Distinctions of person are usually marked in the verb and/or in the associated pronouns (personal pronouns). Usually a three-way contrast is found: first person, in which speakers refer to themselves, or to a group usually including themselves (e.g. I, we); second person, in which speakers typically refer to the person they are addressing (e.g. you); and third person, in which other people, animals, things, etc are referred to (e.g. he, she, it, they). Other formal distinctions may be made in languages, such as 'inclusive' v. 'exclusive' we (e.g. speaker, hearer and others v. speaker and others, but no hearer); formal (or 'honorific') v. informal (or 'intimate'), e.g. French vous v. tu; male v. female; definite v. indefinite (cf. one in English); and so on. There are also several stylistically restricted uses, as in the 'royal' and authorial uses of we. Other word-classes than personal pronouns may show person distinction, as with the reflexive and possessive pronouns in English (myself, etc., my, etc.). Verb constructions which lack person contrast, usually appearing in the third person, are called impersonal. An obviative contrast may also be recognized.

なるほど,一口に人称といっても考慮すべき点はいろいろあるようだ.意味論・語用論的な観点からの人称の捉え方もあれば,文体的な問題としての人称もある.

最後に触れられている obviative という3人称と区別される弁別的な人称の発想はおもしろい.いわば「4人称」である.Crystal (338) の同じ用語辞典より,説明を聞いてみよう.

obviative (adj./n.) A term used in linguistics to refer to a fourth-person form used in some languages (e.g. some North American Indian languages). The obviative form ('the obviative') of a pronoun, verb, etc. usually contrasts with the third person, in that it is used to refer to an entity distinct from that already referred to by the third-person form --- the general sense of 'someone/something else'.

「オレ」「オマエ」「それ以外」という3区分に従えば obviative も3人称であるには違いなく,「4人称」とは不適切な呼称かもしれない.しかし,「4人称」という発想は,人称というフェチな世界観が(いくつかの言語においては)すでに言及されているか否かという談話の観点までも考慮しつつ,どこまでもフェチになりうる文法範疇であることを教えてくれる.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2018-05-16 Wed

■ #3306. we two, you three などの所有格 [genitive][inflection][numeral][syntax][personal_pronoun]

人称代名詞に数詞が後続する we two 「私たち2人」,you three「あなたがた3人」などの名詞句があるが,この名詞句を所有格とする場合にはどうなるのだろうか.Jespersen (§17.15) を参照してみよう.

まず,近代英語では,人称代名詞だけが所有格に屈折し,数詞は無屈折のままという事例がある.例えば,Shakespeare では your three motiues, your two helpes, their two estates, our two histories などがみられる.これらの場合には,数詞は意味的に後ろの名詞にかかっているとも解釈できるだろう.

次に,数詞が所有格マーカーを伴って現われる事例もある.例えば,初期近代の Bullokar などに,our twooz chanc' という表現がみえる.

そして,もちろん迂言法を利用して of us two, of you three とする方法は常に残されている.

数詞ではなく,all, both などを用いた we all や you both のような表現の場合にも,歴史的には上記の3種が可能だった.しかし,これらの語は,人称代名詞の後ではなく前に置いて all our . . . や both your . . . などと用いられるのが,数詞の場合とは異なる点である.また,all については,古英語の後でも比較的遅くまで aller や alder などの属格形が残存していたため,後期中英語の Chaucer でも hir aller cappe, our alder dede などの表現が可能だったことも付記しておこう.

現代英語では,迂言的に逃げる,あるいはその他の表現を工夫して回避するなどの方策が最もスマートだろうか.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

2017-11-27 Mon

■ #3136. singular you は疑わないのに singular they には注目が集まる [personal_pronoun][gender][singular_they]

singular they の話題について,以下の記事で扱ってきた.

・ 「#275. 現代英語の三人称単数共性代名詞」 ([2010-01-27-1])

・ 「#1054. singular they」 ([2012-03-16-1])

・ 「#1887. 言語における性を考える際の4つの視点」 ([2014-06-27-1])

・ 「#1920. singular they を取り締まる規範文法 (1)」 ([2014-07-30-1])

・ 「#1921. singular they を取り締まる規範文法 (2)」 ([2014-07-31-1])

・ 「#1922. singular they を取り締まる規範文法 (3)」 ([2014-08-01-1])

・ 「#2455. 2015年の英語流行語大賞」 ([2016-01-16-1])

先日,Merriam-Webster の辞書サイトのコラムで,Singular 'They' に関する記事を見つけた.1881年に Emily Dickinson が singular they の用例を提供してくれていること,男女という性別の二分法そのものに疑問を呈するシンボルとしての用法が現われてきていることなど興味深い内容を含んだ記事だが,読みながらとりわけなるほどと膝を打ったのが,次のくだりである.

. . . the development of singular they mirrors the development of the singular you from the plural you, yet we don't complain that singular you is ungrammatical . . . .

互いに近すぎるために,これまで気づかなかった.人称代名詞の複数系列では,2人称と3人称においてともに,形態上の数の区別が中和され(得)るということだ.英語史上,人称代名詞体系はちょこちょこ変化してきたが,その伝統は21世紀へも着実に受け継がれており,今も変化と変異を生み出し続けている.

単複兼用の2人称代名詞 you については,「#3099. 連載第10回「なぜ you は「あなた」でもあり「あなたがた」でもあるのか?」」 ([2017-10-21-1]) 及びそこに張ったリンク先を参照されたい.

2017-10-21 Sat

■ #3099. 連載第10回「なぜ you は「あなた」でもあり「あなたがた」でもあるのか?」 [link][notice][personal_pronoun][number][t/v_distinction][category][rensai][sobokunagimon][fetishism]

昨日10月20日付けで,英語史連載企画「現代英語を英語史の視点から考える」の第10回の記事「なぜ you は「あなた」でもあり「あなたがた」でもあるのか?」が公開されました.

本文でも述べているように,この素朴な疑問にも「驚くべき歴史的背景が隠されて」おり,解説を通じて「英語史のダイナミズム」を感じられると思います.2人称代名詞を巡る諸問題については,これまでも本ブログで書きためてきました.以下に関連記事へのリンクを張りますので,どうぞご覧ください.

[ 各時代,各変種の人称代名詞体系 ]

・ 「#180. 古英語の人称代名詞の非対称性」 ([2009-10-24-1])

・ 「#181. Chaucer の人称代名詞体系」 ([2009-10-25-1])

・ 「#196. 現代英語の人称代名詞体系」 ([2009-11-09-1])

・ 「#529. 現代非標準変種の2人称複数代名詞」 ([2010-10-08-1])

・ 「#333. イングランド北部に生き残る thou」 ([2010-03-26-1])

[ 文法範疇とフェチ ]

・ 「#1449. 言語における「範疇」」 ([2013-04-15-1])

・ 「#2853. 言語における性と人間の分類フェチ」 ([2017-02-17-1])

[ 親称と敬称の対立 (t/v_distinction) ]

・ 「#167. 世界の言語の T/V distinction」 ([2009-10-11-1])

・ 「#185. 英語史とドイツ語史における T/V distinction」 ([2009-10-29-1])

・ 「#1033. 日本語の敬語とヨーロッパ諸語の T/V distinction」 ([2012-02-24-1])

・ 「#1059. 権力重視から仲間意識重視へ推移してきた T/V distinction」 ([2012-03-21-1])

・ 「#1126. ヨーロッパの主要言語における T/V distinction の起源」 ([2012-05-27-1])

・ 「#1552. T/V distinction と face」 ([2013-07-27-1])

・ 「#2107. ドイツ語の T/V distinction の略史」 ([2015-02-02-1])

[ thou, ye, you の競合 ]

・ 「#673. Burnley's you and thou」 ([2011-03-01-1])

・ 「#1127. なぜ thou ではなく you が一般化したか?」 ([2012-05-28-1])

・ 「#1336. なぜ thou ではなく you が一般化したか? (2)」 ([2012-12-23-1])

・ 「#1865. 神に対して thou を用いるのはなぜか」 ([2014-06-05-1])

・ 「#291. 二人称代名詞 thou の消失の動詞語尾への影響」 ([2010-02-12-1])

・ 「#2320. 17世紀中の thou の衰退」 ([2015-09-03-1])

・ 「#800. you による ye の置換と phonaesthesia」 ([2011-07-06-1])

・ 「#781. How d'ye do?」 ([2011-06-17-1])

[ 敬称の you の名残り ]

・ 「#440. 現代に残る敬称の you」 ([2010-07-11-1])

・ 「#1952. 「陛下」と Your Majesty にみられる敬意」 ([2014-08-31-1])

・ 「#3095. Your Grace, Your Highness, Your Majesty」 ([2017-10-17-1])

[ you の発音と綴字 ]

・ 「#2077. you の発音の歴史」 ([2015-01-03-1])

・ 「#2234. <you> の綴字」 ([2015-06-09-1])

2017-10-17 Tue

■ #3095. Your Grace, Your Highness, Your Majesty [pragmatics][title][address_term][honorific][monarch][personal_pronoun][agreement]

イギリス君主を呼称・指示するのに,Majesty という称号が用いられる.通常,所有格を伴い,Your Majesty, Her Majesty, His Majesty, Their Majesties, the Queen's Majesty, the King's Majesty などと使われる.Your Majesty は2人称代名詞で受けられるが,動詞に対しては3人称単数で一致するという特殊な用法を示す.

英語における Your Majesty などの「所有格 + Majesty」という敬称の型は,ラテン語の対応表現にならって中英語期から用いられていたが,平行して Your Grace や Your Highness なども同義で用いられていた.石井 (87) によれば,Your Majesty の使用が確立したのは,チューダー朝の開祖 Henry VII の治世下 (1485--1509) においてだったという.

チューダー王朝の開祖ヘンリー七世は,王家のしきたりをいくつか変えたり新設したりしたが,そのなかに王の尊称がある.それまでは,国王の尊称は Your Grace だったが,それを Your Majesty に改め,王権をいちだんと高める措置をとった.以来,君主には Your Majesty と呼びかけるのがルールになっている.

しかし,実際にはチューダー朝の後続の君主たちも,一貫して Your Majesty と呼ばれていたわけではなく,従来からの Your Grace, Your Highness も用いられていた.さらにスチュアート朝でも,開祖 James I に対して Your Majesty と並んで Your Highness も無差別に用いられていた.OED の majesty, n. の語義2の説明によれば,Your Majesty の定着は17世紀のことだったという.James I の治世の後半には確立したようだ.

It was not until the 17th cent. that Your Majesty entirely superseded the other customary forms of address to the sovereign in English. Henry VIII and Queen Elizabeth I were often addressed as 'Your Grace' and 'Your Highness', and the latter alternates with 'Your Majesty' in the dedication of the Bible of 1611 to James I.

チューダー朝からスチュアート朝にかけて,互いに重複しながらも,およそ Your Grace → Your Highness → Your Majesty と移り変わってきたことになる.おりしも絶対王政が敷かれ,君主の権威がいよいよ高まってきた時代である.音節が1つずつ増え,より重く厳かになってきているようで興味深い.

・ 石井 美樹子 『図説 イギリスの王室』 河出書房,2007年.

2016-11-22 Tue

■ #2766. 初期中英語における1人称代名詞主格の異形態の分布 [laeme][eme][map][personal_pronoun][owl_and_nightingale][compensatory_lengthening]

初期中英語のテキスト The Owl and the Nightingale を Cartlidge 版で読んでいる.868行にこのテキストからの唯一例として,1人称代名詞主格として ih の綴字が現われる.梟が歌のさえずり方について議論しているシーンで,Ne singe ih hom no foliot! として用いられている.この綴字はC写本のものであり,対するJ写本ではこの箇所に一般的な綴字 ich が用いられている.

この事実から,初期中英語における1人称代名詞主格の異形態の分布に関心をもった.そこで,LAEME で分布をさっと調べてみることにした.特に気になっているのは語末の子音の有無,およびその子音の種類である.母音を無視して典型的な綴字タイプを取り出してみると,ich, ik, ih, i 辺りが挙がる.細かく見ればほかにもありうるが,当面この4系列の綴字について出現分布を大雑把にみておきたい.

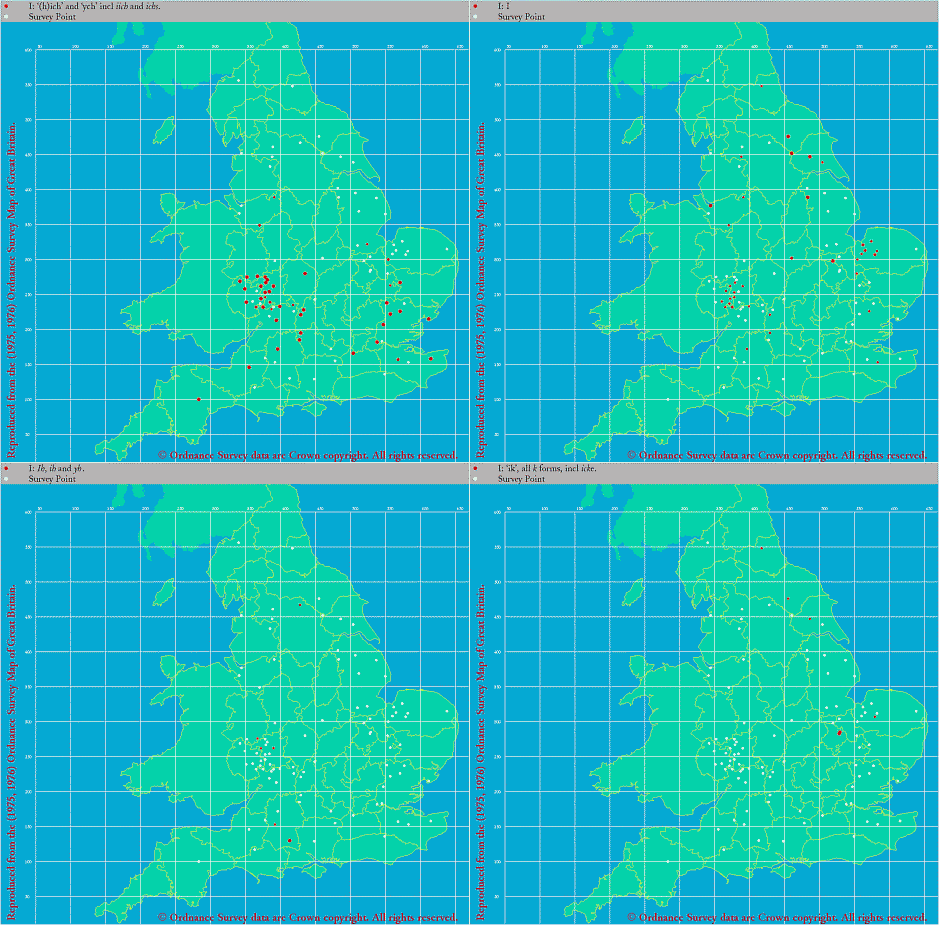

LAEME のプログラムはよくできているので,私の行なったことといえば,該当する形態に関して地図を表示させることのみだ.以下に4枚の方言分布図をつなぎ合わせたものを掲載する.キャンプションが小さくて読みにくいが,位置関係は次の表に示した通り(画像をクリックすれば拡大版が現われる).

| 以下の合成地図での位置 | Map No. | 説明 |

|---|---|---|

| 左上 | 00001312 | I: Ih, ih and yh |

| 右上 | 00001305 | I: 'ik', all k forms, incl icke. |

| 左下 | 00001302 | I: '(h)ich' and 'ych' incl iich and ichs |

| 右下 | 00001308 | I: I. |

分布としては,左上の伝統的な ich 系が最も普通に南中部に広がっているのが分かる.右上の子音の落ちた i 系の綴字も普通であり,主として中部から北部に広がっている.左下の ih 系が今回注目した綴字を表わすが,西中部や南西部の,いわゆる最も保守的と言われる方言部分に散見される程度である.右下の ik 系は,東中部や北部に散在する程度で,一般的ではない.

The Owl and the Nightingale の方言については様々な議論がなされてきたが,いずれの写本の方言も,南西中部のものという解釈が一般的である.その点からすると,C写本で ih が現われたということは,初期中英語の全体の方向性と一致するだろう.

この問題に関心をもっているのは,伝統的な ich かいかなる経路を辿って後の I へと変化していったかという歴史的な問題に関係するからだ.この問題の周辺について,「#1198. ic → I」 ([2012-08-07-1]),「#1773. ich, everich, -lich から語尾の ch が消えた時期」 ([2014-03-05-1]) で簡単に話題にしたが,単に /ʧ/ と想定される語末子音が消失し,先行母音が代償延長 (compensatory_lengthening) したと考えておくだけでよいのか,疑念が残るのである.周辺的な方言に散見される ih や ik の語末子音は,/ʧ/ と通時的・共時的にどのような関係にあるのか.ih の子音は /ʧ/ の弱化した音で,消失への途中段階を表わすものではないか等々,いろいろな可能性が頭に浮かぶ.

・ Cartlidge, Neil, ed. The Owl and the Nightingale. Exeter: U of Exeter P, 2001.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2016-10-24 Mon

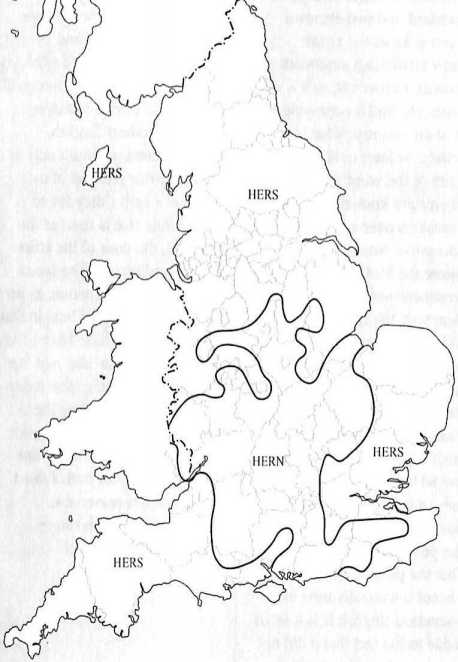

■ #2737. 現代イギリス英語における所有代名詞 hern の方言分布 [map][personal_pronoun][suffix][dialect][terminology]

「#2734. 所有代名詞 hers, his, ours, yours, theirs の -s」 ([2016-10-21-1]) の記事で,-s の代わりに -n をもつ,hern, hisn, ourn, yourn, theirn などの歴史的な所有代名詞に触れた.これらの形態は標準英語には残らなかったが,方言では今も現役である.Upton and Widdowson (82) による,hern の方言分布を以下に示そう.イングランド南半分の中央部に,わりと広く分布していることが分かるだろう.

-n 形については,Wright (para. 413) でも触れられており,19世紀中にも中部,東部,南部,南西部の諸州で広く用いられていたことが知られる.

-n 形は,非標準的ではあるが,実は体系的一貫性に貢献している.mine, thine も含めて,独立用法の所有代名詞が一貫して [-n] で終わることになるからだ.むしろ,[-n] と [-z] が混在している標準英語の体系は,その分一貫性を欠いているともいえる.

なお,my と mine のような用法の違いは,Upton and Widdowson (83) によれば,限定所有代名詞 (attributive possessive pronoun) と叙述所有代名詞 (predicative possessive pronoun) という用語によって区別されている.あるいは,conjunctive possessive pronoun と disjunctive possessive pronoun という用語も使われている.

・ Upton, Clive and J. D. A. Widdowson. An Atlas of English Dialects. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge, 2006.

・ Wright, Joseph. The English Dialect Grammar. Oxford: OUP, 1905. Repr. 1968.

2016-10-21 Fri

■ #2734. 所有代名詞 hers, his, ours, yours, theirs の -s [personal_pronoun][genitive][inflection][suffix]

現代英語で「?のもの」を意味する所有代名詞は,1人称単数の mine を除き,いずれも -s が付き,yours, his, hers, ours, theirs のようになる (it に対応する所有代名詞が事実上ない件については,「#197. its に独立用法があった!」 ([2009-11-10-1]) を参照).端的にいえば,名詞の所有格および「?のもの」を意味する -'s を,代名詞にも応用したものと考えることができるが,一般化したのはそれほど古くなく,15世紀のことである.では,それ以前には,所有代名詞に相当する表現は何だったのだろうか.

古英語と中英語では,人称代名詞の所有格がそのまま所有代名詞としても用いられており,この状況は17世紀まで見られた.現代風にいえば,所有格の your, her, our, their などがそのまま所有代名詞としても用いられていたということだ.しかし,中英語では,所有代名詞として別の刷新形も現われ,並行して用いられるようになった.北部方言では,現代の hers, ours, yours, ours につらなる -s の付いた形態が,a1325 の Cursor Mundi に軒並み初出する.

一方,南・中部では -s ならぬ -n の付いた hern (hers, theirs) が早くから ?a1200 の Ancrene Riwle で現われ,後期中英語には hisn, yourn, ourn, theirn も現われた.この -n を伴う形態は,my/mine や thi/thine に見られるような交替からの類推と考えられる(1・2人称単数については,古英語より mīn, þīn に所有代名詞としての用法がすでに存在した).これらの -n 形は現代では方言に限定されるなどして,一般的ではない.

歴史的には,初期中英語の北部方言に現われた -s をもつ刷新形の所有代名詞が,15世紀に分布を広げて一般化し,標準形として現代英語に伝わったことになる.

2016-08-30 Tue

■ #2682. 3人称代名詞を欠く言語 [japanese][personal_pronoun][person][deixis][category][cognitive_linguistics][pragmatics]

「#2680. deixis」 ([2016-08-28-1]) に関わる文法範疇 (category) の1つに,人称 (person) がある.ただし,直接 deixis に関係するのは,1人称(話し手)と2人称(聞き手)のみであり,いわゆる3人称とはそれ以外の一切の事物として否定的に定義されるものである.「私」と「あなた」の指示対象は,会話の参与者が変わればそれに応じて当然変わるものであり,コミュニケーションにとって,このように相対的な指示機能を果たす1・2人称代名詞が是非とも必要だが,3人称については,絶対的にそれを指し示す名詞(句)だけを使っても用を足すことはできる.例えば代名詞「彼」や「彼女」を用いる代わりに,「鈴木」や「山田」と名前を繰り返し用いて済ませることも可能である.したがって,諸言語の人称代名詞体系において最も本質的なものは1,2人称であり,3人称は場合によってなしでも可である.

Huang (137) は,3人称代名詞を欠く言語がありうる理由について,次のように述べている.

Third person is the grammaticalization of reference to persons or entities which are neither speakers nor addressees in the situation of utterance, that is, the 'participant-role' with speaker and addressee exclusion [-S, -A] . . . . Notice that third person is unlike first or second person in that it does not necessarily refer to any specific participant-role in the speech event . . . . Therefore, it can be regarded as the grammatical form of a residual non-deictic category, given that it is closer to non-person than either first or second person . . . . This is why all of the world's languages seem to have first- and second-person pronouns, but some appear to have no third-person pronouns.

具体的に Huang が3人称代名詞を欠く言語として言及しているのは,Dyirbal, Hopi, Yéli Dnye, Yidiɲ, 及びコーカサス諸語である.

実は,日本語にしても,人称代名詞をどのように考えるかという議論はあるが,3人称代名詞については古来指示代名詞の転用が一般的であり,独自のものはなかったといってよい.1人称はア・アレ,ワ・ワレ,2人称ではナ・ナレが固有の語幹としてあったのに対し,3人称は少なくとも独自の語幹をもつほどには発達していなかったからだ.

ところで,日本語でも英語でも小さい子供が自分のことを1人称代名詞ではなく固有名詞で呼ぶ現象があるが,あれは相対的なものの見方や自我の発達と関係があるのだろうか.deixis は,その時々の立ち位置を定めた上での相対的な指示機能であるから,認知能力の発達と関係しそうではある.これは絶対敬語の問題とも関係し,広い意味で語用論の話題,deixis の話題といえる.

・ Huang, Yan. Pragmatics. Oxford: OUP, 2007.

2016-08-28 Sun

■ #2680. deixis [pragmatics][deixis][demonstrative][personal_pronoun][tense][adverb]

語用論の基本的な話題の1つに deixis (ダイクシス,直示性)がある.この用語は,ギリシア語で「示す,指し示す」を意味する deikunúnai に由来する.Huang (132) の定義によれば,deixis とは "the phenomenon whereby features of context of utterance or speech event are encoded by lexical and/or grammatical means in a language" である.直示表現 (deictic (expression)) には,指示詞 (demonstrative),1・2人称代名詞 (1st and 2nd personal_pronoun),時制標識 (tense marker),時や場所の副詞 (adverb of time and place),移動動詞 (motion verb) が含まれる.

何らかの deixis をもたない言語は存在しない.それは,deixis を標示する手段がないと,人間の通常のコミュニケーション上の要求を満たすことができないからだ.確かに「私」「ここ」「今」のような直示的概念なしでは,いかなる言語も役に立たないだろう.海辺で拾った瓶のメモに "Meet me here a month from now with a magic wand about this long." と書かれていても,誰に,どこで,いつ,どのくらいの長さの杖をもって会えばよいのか不明である.これは読み手が書き手の意図した deixis を解決できないために生じるコミュニケーション障害である.

英語の直示表現の典型例として you を挙げよう.通常,話し相手を指して you が用いられ,時と場合によって you の指示対象は変わるものであるから,これは典型的な直示表現といえる.しかし,If you travel on a train without a valid ticket, you will be liable to pay a penalty fare. のように一般人称として用いられる you では,本来の直示的な性質はなりをひそめており,2人称代名詞 you の非直示的用法の例というべきだろう.

直示表現のもう1つの典型例として,this を挙げよう.指さしや視線などの物理的なジェスチャーを伴って this table と言うとき,この this はすぐれて直示的な用法といえるが,物理的な行動を伴わずに this town と言うときには,この this は直示的ではあるがより象徴的な用法といえる.後者は前者からの発展的,派生的用法と考えられ,実際,ジェスチャー用法 (gestural) でしか用いられず,象徴的 (symbolic) な用法を欠いているフランス語の voici, voilà のような直示表現もある.言い換えれば,象徴的用法のみをもつ直示表現というのはありそうにない.

以上より,直示表現の用法は以下のように分類される (Huang 135 の図を改変).

┌─── Gestural

│

┌─── Deictic use ───┤

│ │

Deictic expression ───┤ └─── Symbolic

│

└─── Non-deictic use

・ Huang, Yan. Pragmatics. Oxford: OUP, 2007.

2016-04-30 Sat

■ #2560. 古英語の形容詞強変化屈折は名詞と代名詞の混合パラダイム [adjective][ilame][terminology][morphology][inflection][oe][germanic][paradigm][personal_pronoun][noun]

古英語の形容詞の強変化・弱変化の区別については,ゲルマン語派の顕著な特徴として「#182. ゲルマン語派の特徴」 ([2009-10-26-1]),「#785. ゲルマン度を測るための10項目」 ([2011-06-21-1]),「#687. ゲルマン語派の形容詞の強変化と弱変化」 ([2011-03-15-1]) で取り上げ,中英語における屈折の衰退については ilame の各記事で話題にした.

強変化と弱変化の区別は古英語では名詞にもみられた.弱変化形容詞の強・弱屈折は名詞のそれと形態的におよそ平行しているといってよいが,若干の差異がある.ことに形容詞の強変化屈折では,対応する名詞の強変化屈折と異なる語尾が何カ所かに見られる.歴史的には,その違いのある箇所には名詞ではなく人称代名詞 (personal_pronoun) の屈折語尾が入り込んでいる.つまり,古英語の形容詞強変化屈折は,名詞屈折と代名詞屈折が混合したようなものとなっている.この経緯について,Hogg and Fulk (146) の説明に耳を傾けよう.

As in other Gmc languages, adjectives in OE have a double declension which is syntactically determined. When an adjective occurs attributively within a noun phrase which is made definite by the presence of a demonstrative, possessive pronoun or possessive noun, then it follows one set of declensional patterns, but when an adjective is in any other noun phrase or occurs predicatively, it follows a different set of patterns . . . . The set of patterns assumed by an adjective in a definite context broadly follows the set of inflexions for the n-stem nouns, whilst the set of patterns taken in other indefinite contexts broadly follows the set of inflexions for a- and ō-stem nouns. For this reason, when adjectives take the first set of inflexions they are traditionally called weak adjectives, and when they take the second set of inflexions they are traditionally called strong adjectives. Such practice, although practically universal, has less to recommend it than may seem to be the case, both historically and synchronically. Historically, . . . some adjectival inflexions derive from pronominal rather than nominal forms; synchronically, the adjectives underwent restructuring at an even swifter pace than the nouns, so that the terminology 'strong' or 'vocalic' versus 'weak' or 'consonantal' becomes misleading. For this reason the two declensions of the adjective are here called 'indefinite' and 'definite' . . . .

具体的に強変化屈折のどこが起源的に名詞的ではなく代名詞的かというと,acc.sg.masc (-ne), dat.sg.masc.neut. (-um), gen.dat.sg.fem (-re), nom.acc.pl.masc. (-e), gen.pl. for all genders (-ra) である (Hogg and Fulk 150) .

強変化・弱変化という形態に基づく,ゲルマン語比較言語学の伝統的な区分と用語は,古英語の形容詞については何とか有効だが,中英語以降にはほとんど無意味となっていくのであり,通時的にはより一貫した統語・意味・語用的な機能に着目した不定 (definiteness) と定 (definiteness) という区別のほうが妥当かもしれない.

・ Hogg, Richard M. and R. D. Fulk. A Grammar of Old English. Vol. 2. Morphology. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2016-01-16 Sat

■ #2455. 2015年の英語流行語大賞 [lexicology][ads][woy][personal_pronoun][gender][link][singular_they]

今年もこの時期がやってきた.American Dialect Society による 2015年の The Word of the Year が1月8日に発表された.今年の受賞は,singular "they" である.

They was recognized by the society for its emerging use as a pronoun to refer to a known person, often as a conscious choice by a person rejecting the traditional gender binary of he and she.

. . . .

The use of singular they builds on centuries of usage, appearing in the work of writers such as Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Jane Austen. In 2015, singular they was embraced by the Washington Post style guide. Bill Walsh, copy editor for the Post, described it as "the only sensible solution to English's lack of a gender-neutral third-person singular personal pronoun."

While editors have increasingly moved to accepting singular they when used in a generic fashion, voters in the Word of the Year proceedings singled out its newer usage as an identifier for someone who may identify as "non-binary" in gender terms.

"In the past year, new expressions of gender identity have generated a deal of discussion, and singular they has become a particularly significant element of that conversation," Zimmer said. "While many novel gender-neutral pronouns have been proposed, they has the advantage of already being part of the language."

なぜ今さら singular they がという気がしないでもなかったが,上の記事と合わせて Wordorigins.org: ADS Word of the Year for 2015 の記事を読んでみて合点がいった.単に性別を問わない単数の一般人称代名詞としての they の用法はここ数十年間で確かに認知されてきており,とりわけ2015年を特徴づける語法というわけではないが,男女という性別の二分法そのものに疑問を呈するシンボル (nonbinary identifier) として,昨年,焦点が当てられたという.テレビ番組などで transgender の話題が多く取り上げられ,"nonbinary identifier" としての they の使用が目立ったということだ.なお,singular they は,MOST USEFUL カテゴリーでも受賞している.時代のキーワードであることが,特によくわかる受賞だった.

singular_they については,本ブログでも何度か扱ってきたので,以下にリンクを張っておきたい.

・ 「#275. 現代英語の三人称単数共性代名詞」 ([2010-01-27-1])

・ 「#1054. singular they」 ([2012-03-16-1])

・ 「#1887. 言語における性を考える際の4つの視点」 ([2014-06-27-1])

・ 「#1920. singular they を取り締まる規範文法 (1)」 ([2014-07-30-1])

・ 「#1921. singular they を取り締まる規範文法 (2)」 ([2014-07-31-1])

・ 「#1922. singular they を取り締まる規範文法 (3)」 ([2014-08-01-1])

過去の WOY の受賞については,woy を参照.

2015-11-01 Sun

■ #2379. 再帰代名詞の外適応 [exaptation][reflexive_pronoun][personal_pronoun][syntax][speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][language_change]

「#2376. myself, thyself における my- と thy-」 ([2015-10-29-1]) で取り上げた Keenan の論文では,近現代英語の再帰代名詞が外適応 (exaptation) の結果生まれたものであることが説かれている.oneself の形態は,当初,人称代名詞の対照的な用法として始まったが,それが同一指示あるいは局所的束縛という性質を獲得し,今見られるような再帰的用法として機能するようになったという ("pron + self is selected because of its contrast function, and later, losing contrast, survives because of its local binding function" (250)) .

Keenan (346) は,古英語から近代英語にかけての oneself の用法別の分布を取り,このことを示そうとした.古英語および中英語において,再帰的用法は,集められた oneself の直接目的語としての全用例のうち20%程度を占めるにすぎないが,初期近代英語には突如として80%を越える.これは,言語変化の速度やスケジュールという観点からは,急激なS字曲線を描くということになり,興味深い現象である.

Keenan (347) は,対照用法から再帰用法への外適応の道筋を,次のように考えている.

. . . by the end of ME bare object occurrences of pron + self are losing their contrast interpretation. But this leads again to an ANTI-SYNONYMY violation on a paradigm level. Without the contrast interpretation a locally bound pron + self is synonymous with a locally bound bare pronoun. So him and him + self, her and her + self, etc. would become synonyms. This was avoided by an interpretative differentiation: pron + self in object position came to require local antecedents and bare pronouns came to reject local antecedents (in favor of the always possible non-local ones or deictic interpretations).

なお,Keenan は,この変化はあくまで外適応であり,文法化 (grammaticalisation) ではないと判断している.「#1975. 文法化研究の発展と拡大 (2)」 ([2014-09-23-1]) や「#2146. 英語史の統語変化は,語彙投射構造の機能投射構造への外適応である」 ([2015-03-13-1]) で示唆したように,外適応は文法化との関連で論じられることが多いが,両者の関係は必ずしも単純ではないのかもしれない.

・ Keenan, Edward. "Explaining the Creation of Reflexive Pronouns in English." Studies in the History of the English Language: A Millennial Perspective. Ed. D. Minkova and R. Stockwell. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 2002. 325--54.

2015-10-29 Thu

■ #2376. myself, thyself における my- と thy- [reflexive_pronoun][personal_pronoun][case][clitic]

再帰代名詞の oneself の前半要素に,人称代名詞の所有格形が当てられているか (ex. myself, thyself),目的格形が当てられているか (ex. himself, themselves) の問題は,英語史で長らく議論されてきた問題の1つである.本ブログでも,「#47. 所有格か目的格か:myself と himself」 ([2009-06-14-1]),「#1851. 再帰代名詞 oneself の由来についての諸説」 ([2014-05-22-1]) で扱ってきた.

myself, thyself で所有格が用いられることについて,先の記事では self が名詞と解釈されたとする説とケルト語からの影響とする説を紹介した.もう1つ有力なのは,Mustanoja (146) などのとる与格形の母音弱化説である.初期中英語では,1,2人称でも self に前置されるのは3人称の場合と同様に与格形であり,me self, þe self などと表わされていた.この me や þe が後接辞 (proclitic) のように機能し始めると音声的に弱化し,e で表わされる母音が i へと変化した.かくして13世紀末頃に miself, þiself となるに及び,mi, þi は所有格として,self は名詞としてとして再分析され,これを1,2人称複数に応用した our selve(n), your selve(n) も現われるようになったという.後接辞の音声弱化は,biforen, bitwene における be- > bi- などにしばしば観察される,よくある現象である.

Keenan (344) も,次のように述べて Mustanoja の音声弱化説を支持している.

I claim these forms [= mi + self and þi + self] are just phonologically reduced forms of the procliticized dative pronouns me and þe. The correspondence of Old English long close e to Middle English short i is well attested . . . . Me and þe are the only dative pronouns that consist of a single light syllable. The others are either closed (him, us, hem or disyllabic or diphthongal (hire, eow). So it is natural that phonological reduction takes place first in 1st and 2nd sg. Once reduced we may identify them with possessive adjectives, surely the basis of the Pattern Generalization to your + self and our + self in 1st and 2nd pl (modern spelling) in the mid-1300s, which facilitates interpreting self as a N.

この説は,me と þi のみが開いた単音節であるという指摘において,説得力があるように思われる.また,人称代名詞のような語類において,歴史上,何度も繰り返し音声の弱化と強化が生じてきたことは,「#1198. ic → I」 ([2012-08-07-1]),「#2076. us の発音の歴史」 ([2015-01-02-1]),「#2077. you の発音の歴史」 ([2015-01-03-1]) でも見てきたとおりである.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

・ Keenan, Edward. "Explaining the Creation of Reflexive Pronouns in English." Studies in the History of the English Language: A Millennial Perspective. Ed. D. Minkova and R. Stockwell. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 2002. 325--54.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow