2016-01-29 Fri

■ #2468. 「英語は語彙的にはもはや英語ではない」の評価 [lexicology][loan_word][borrowing][japanese][style][register]

英語の語彙の大部分が諸言語からの借用語から成っていること,つまり世界的 (cosmopolitan) であることは,つとに指摘されてきた.そこから,英語は語彙的にはもはや英語とはいえない,と論じることも十分に可能であるように思われる.英語は,もはや借用語彙なしでは十分に機能しえないのではないか,と.

しかし,Algeo and Pyles (293--94) は,英語における語彙借用の著しさを適切に例証したうえで,なお "English remains English" たることを独自に主張している.少々長いが,意味深い文章なのでそのまま引用する.

Enough has been written to indicate the cosmopolitanism of the present English vocabulary. Yet English remains English in every essential respect: the words that all of us use over and over again, the grammatical structures in which we couch our observations upon practically everything under the sun remain as distinctively English as they were in the days of Alfred the Great. What has been acquired from other languages has not always been particularly worth gaining: no one could prove by any set of objective standards that army is a "better" word than dright or here., which it displaced, or that advice is any better than the similarly displaced rede, or that to contend is any better than to flite. Those who think that manual is a better, or more beautiful, or more intellectual word than English handbook are, of course, entitled to their opinion. But such esthetic preferences are purely matters of style and have nothing to do with the subtle patternings that make one language different from another. The words we choose are nonetheless of tremendous interest in themselves, and they throw a good deal of light upon our cultural history.

But with all its manifold new words from other tongues, English could never have become anything but English. And as such it has sent out to the world, among many other things, some of the best books the world has ever known. It is not unlikely, in the light of writings by English speakers in earlier times, that this could have been so even if we had never taken any words from outside the word hoard that has come down to us from those times. It is true that what we have borrowed has brought greater wealth to our word stock, but the true Englishness of our mother tongue has in no way been lessened by such loans, as those who speak and write it lovingly will always keep in mind.

It is highly unlikely that many readers will have noted that the preceding paragraph contains not a single word of foreign origin. It was perhaps not worth the slight effort involved to write it so; it does show, however, that English would not be quite so impoverished as some commentators suppose it would be without its many accretions from other languages.

英語と同様に大量の借用語からなる日本語の語彙についても,ほぼ同じことが言えるのではないか.漢語やカタカナ語があふれていても,日本語はそれゆえに日本語性を減じているわけではなく,日本語であることは決してやめていないのだ,と.

現在,日本では大和言葉がちょっとしたブームである.これは,1つには日本らしさを発見しようという昨今の潮流の言語的な現われといってよいだろう.ここには,消極的にいえば氾濫するカタカナ語への反発,積極的にいえばカタカナ語を鏡としての和語の再評価という意味合いも含まれているだろう.また,コミュニケーションの希薄化した現代社会において,人付き合いを円滑に進める潤滑油として和語からなる表現を評価する向きが広がってきているともいえる.いずれにせよ,日本語における語彙階層や語彙の文体的・位相的差違を省察する,またとない機会となっている.この機会をとらえ,日本語のみならず英語の語彙について改めて論じる契機ともしたいものである.

関連して,以下の記事も参照されたい.

・ 「#153. Cosmopolitan Vocabulary は Asset か?」 ([2009-09-27-1])

・ 「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1])

・ 「#335. 日本語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-28-1])

・ 「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1])

・ 「#1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造」 ([2014-09-08-1])

・ 「#2072. 英語語彙の三層構造の是非」 ([2014-12-29-1])

・ 「#756. 世界からの借用語」 ([2011-05-23-1])

・ 「#390. Cosmopolitan Vocabulary は Asset か? (2)」 ([2010-05-22-1])

・ 「#2359. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由 (3)」 ([2015-10-12-1])

・ Algeo, John, and Thomas Pyles. The Origins and Development of the English Language. 5th ed. Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

2015-12-18 Fri

■ #2426. York Memorandum Book にみられる英仏羅語の多種多様な混合 [code-switching][borrowing][loan_word][french][anglo-norman][latin][bilingualism][hybrid][lexicology]

後期中英語の code-switching や macaronic な文書について,「#1470. macaronic lyric」 ([2013-05-06-1]),「#1625. 中英語期の書き言葉における code-switching」 ([2013-10-08-1]),「#1941. macaronic code-switching としての語源的綴字?」 ([2014-08-20-1]),「#2271. 後期中英語の macaronic な会計文書」 ([2015-07-16-1]),「#2348. 英語史における code-switching 研究」 ([2015-10-01-1]) などで取り上げてきた.関連して,英仏羅語の混在する15世紀の経営・商業の記録文書を調査した Rothwell の論文を読んだので,その内容を紹介する.

調査対象となった文書は York Memorandum Book と呼ばれるもので,これは次のような文書である (Rothwell 213) .

The two substantial volumes of the York Memorandum Book provide some five hundred pages of records detailing the administrative and commercial life of the second city in England over the years between 1376 and 1493, setting down in full charters, ordinances of the various trade associations, legal cases involving citizens and so on.

York Memorandum Book には,英仏羅語の混在が見られるが,混在の種類も様々である.Rothwell の分類によれば,11種類の混在のさせ方がある.Rothwell (215--16) の文章より抜き出して,箇条書きで整理すると

(i) "English words inserted without modification into a Latin text"

(ii) "English words similarly introduced into a French text"

(iii) "French words used without modification into a Latin text"

(iv) "French words similarly used in an English text"

(v) "English words dressed up as Latin in a Latin text"

(vi) "English words dressed up as French in a French text"

(vii) "French words dressed up as Latin in a Latin text"

(viii) "French words are used in a specifically Anglo-French sense in a French text"

(ix) "French words may be found in a Latin text dressed up as Latin, but with an English meaning"

(x) "On occasion, a single word may be made up of parts taken from different languages . . . or a new word may be created by attaching a suffix to an existing word, either from the same language or from one language or another""

(xi) "Outside the area of word-formation there is also the question of grammatical endings to be considered"

3つもの言語が関わり,その上で "dressed up" の有無や意味の往来なども考慮すると,このようにきめ細かな分類が得られるということも頷ける.(x) はいわゆる混種語 (hybrid) に関わる問題である (see 「#96. 英語とフランス語の素材を活かした 混種語 ( hybrid )」 ([2009-08-01-1])) .このように見ると,語彙借用,その影響による新たな語形成の発達,意味の交換,code-switching などの諸過程がいかに互いに密接に関連しているか,切り分けがいかに困難かが察せられる.

Rothwell は結論として,当時のこの種の英仏羅語の混在は,無知な写字生による偶然の産物というよりは "recognised policy" (230) だったとみなすべきだと主張している.また,14--15世紀には,業種や交易の拡大により経営・商業の記録文書で扱う内容が多様化し,それに伴って専門的な語彙も拡大していた状況において,書き手は互いの言語の単語を貸し借りする必要に迫られたに違いないとも述べている.Rothwell (230) 曰く,

Before condemning the scribes of late medieval England for their ignorance, account must be taken of the situation in which they found themselves. On the one hand the recording of administrative documents steadily increasing in number and diversity called for an ever wider lexis, whilst on the other hand the conventions of the time demanded that such documents be couched in Latin or French. No one has ever remotely approached complete mastery of the lexis of his own language, let alone that of any other language, either in medieval or modern times.

Rothwell という研究者については「#1212. 中世イングランドにおける英語による教育の始まり (2)」 ([2012-08-21-1]),「#2348. 英語史における code-switching 研究」 ([2015-10-01-1]),「#2349. 英語の復権期にフランス借用語が爆発したのはなぜか (2)」 ([2015-10-02-1]),「#2350. Prioress の Anglo-French の地位はそれほど低くなかった」 ([2015-10-03-1]),「#2374. Anglo-French という補助線 (1)」 ([2015-10-27-1]),「#2375. Anglo-French という補助線 (2)」 ([2015-10-28-1]) でも触れてきたので,そちらも参照.

・ Rothwell, William. "Aspects of Lexical and Morphosyntactical Mixing in the Languages of Medieval England." Multilingualism in Later Medieval Britain. Ed. D. A. Trotter. D. S. Brewer, 2000. 213--32.

2015-11-18 Wed

■ #2396. フランス語からの句の借用に対する慎重論 [french][loan_translation][borrowing][contact][phraseology][ormulum][old_norse][phrasal_verb]

「#2351. フランス語からの句動詞の借用」 ([2015-10-04-1]) と昨日の記事「#2395. フランス語からの句の借用」 ([2015-11-17-1]) で話題にしたように,英語は中英語期にフランス語の単語のみならず句や表現を借用してきたと主張されてきた.一方,この主張に対して慎重な立場を取る論者もいる.その1人が Sypherd である.Sypherd はフランス語法借用説を主張する Sykes による論文 French Elements in Middle English (1899) を厳しく批判し,慎重論を展開した.

Sypherd の論の進め方は明解である.Sykes がフランス語の影響があると指摘している英語の句や表現の多くが,Sykes の取り上げている諸文献よりも早い時期に書かれた Ormulum に現われていることを,実証的に示したのである.Ormulum は,East Midland 方言で1200年頃に書かれたとされる長大な宗教詩で,方言的にも時代的にもフランス語の影響が少ないとされるテキストである.このテキストは,むしろ古ノルド語の言語的影響を強く示すものとして知られている.そこで,Sypherd (6--7) は,Sykes のいう「フランス語法」とは,むしろ古ノルド語法とすら考えられるのではないかと,逆手を取る.

Now, if in the Ormulum, a poem free from French influence, these phrases which Mr. Sykes ascribes to the Old French occur with considerable frequency, we are surely justified in denying the overwhelming French phrasal influence on Middle English. Furthermore, the justification of this denial is strengthened when we find that in Old-Norse literature anterior to or contemporary with Orm there exist in comparative abundance many of the identical phrases found in the Ormulum and in other Middle-English literature. And finally, though I do not urge it, the probability of considerable Old-Norse phrasal influence on Orm demands consideration, especially if we bear in mind the following facts: (1) the marked Old-Norse influence in general on Orm; (2) the Old-Norse literature in which these phrases occur in homiletic, sermonic; (3) much of the literature antedates the Ormulum.

もちろん,Sypherd はこの後論文のなかで,古ノルド語の文献から問題の英語の語法におよそ対応する表現を取り出して,提示してゆく.対象となったのは "bear witness", "take baptism", "take flesh, humanity", "take death", "take example", "take heed, take keep, take ȝeme", "take end", "take wife", "take rest", "take cross" に相当する句動詞であり,種類は必ずしも多くないが,議論と例示は全体として盤石で説得力がある.

昨日の記事の末尾でも述べたように,句の借用を実証することは案外難しい.Sypherd も,論文の読後感としては,フランス語からの借用とする説そのものを鋭く批判しているように聞こえるが,おそらく主張したいのは,そのような説には慎重に向き合うべきであり,別の可能性も考慮すべきである,ということだろう.

・ Sypherd, W. Owen. "Old French Influence on Middle English Phraseology." Modern Philology 5 (1907): 85--96.

2015-11-17 Tue

■ #2395. フランス語からの句の借用 [french][loan_translation][borrowing][contact][phraseology][proverb][methodology]

「#2351. フランス語からの句動詞の借用」 ([2015-10-04-1]) の話題と関連して,Prins の論文 "French Influence in English Phrasing" を紹介する.Prins はこの論文で,フランス語の影響が想定される英語の表現が多数あることを,豊富な具体例を挙げながら主張する.Prins の言葉をそのまま借りると,". . . besides the numerous isolated words which English has borrowed from French, there are also a great many cases in which complete phrases and turns of speech, proverbs and proverbial sayings were taken over from French and incorporated in the English language" (28) ということである.

論文の大半は,フランス語と英語の文献から集めた文脈つきの対応表現リストである.本記事では,その一覧を再現するのは控え,Prins が結論として指摘している3点を要約するにとどめたい.1点目は,フランス語由来と目される英語の句・表現が,14世紀にピークを迎えているという事実である.前の記事 ([2015-10-04-1]) で参照した Iglesias-Rábade も述べていたように,単体のフランス借用語のピークと時間的におよそ符合するという事実が重要である.ただし,Iglesias-Rábade は句の借用のピークを14世紀後半とみているのに対して,Prins は14世紀前半とみているという違いがある.Prins (81) が挙げている統計表を再現しておこう.

Period Items N. B. 1000--1100 1 1100--1200 0 1200--1300 13 (3 of which ins S. E. Leg.. c 1290) 1300--1400 29 (during the first half of the century twice as as many as during the second. Brunne comes in for 8, Cursor Mundi for 5, Chaucer for 4 items) 1400--1500 12 (of which 5 in Caxton) 1500--1600 8 1600--1700 3 1700--1800 1 1800--1900 1

次に,上掲の表に示される数の句の多くが,現代まで残っているという事実が指摘されている.現在までに廃用あるいは古風となっているものは15個にすぎず,残りの53個は現役で,"part and parcel of every day speech" (81--82) であるという.残存率は77.9%と確かに高い.

3点目として,借用された句の意味領域に注目すると,様々ではあるが,主たるところを挙げれば戦争関係が17個,騎士道が11個,法律が9個となる.文学史的にはフランス語の散文の文体が英語に恩恵を与えたのは15世紀後半といわれることが多いが,これらの表現の借用も文体的な含みがあることを考えれば,問題の恩恵は実際にはもっと早い時期から始まっていたと考えることができるかもしれない.

問題の多くの句は,フランス語の句の翻訳借用 (loan_translation) として提示されている.つまり,英語側の表現には,フランス借用語ではなく英語本来語の含まれているものが多い.そのような場合には,本当にフランス語からの「なぞり」なのか,あるいは英語で自前で作り上げられた表現なのか,確定するのが難しいケースもままある.単語単体ではなく,複数の単語を組み合わせた句や表現の借用に関する研究は,文法的な借用の研究とともに,方法として難しいところがある.

・ Prins, A. A. "French Influence in English Phrasing." Neophilologus 32 (1948): 28--39, 73--83.

2015-11-07 Sat

■ #2385. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計 (2) [oed][statistics][lexicology][loan_word][borrowing][latin][greek][french][italian][spanish][portuguese][romancisation]

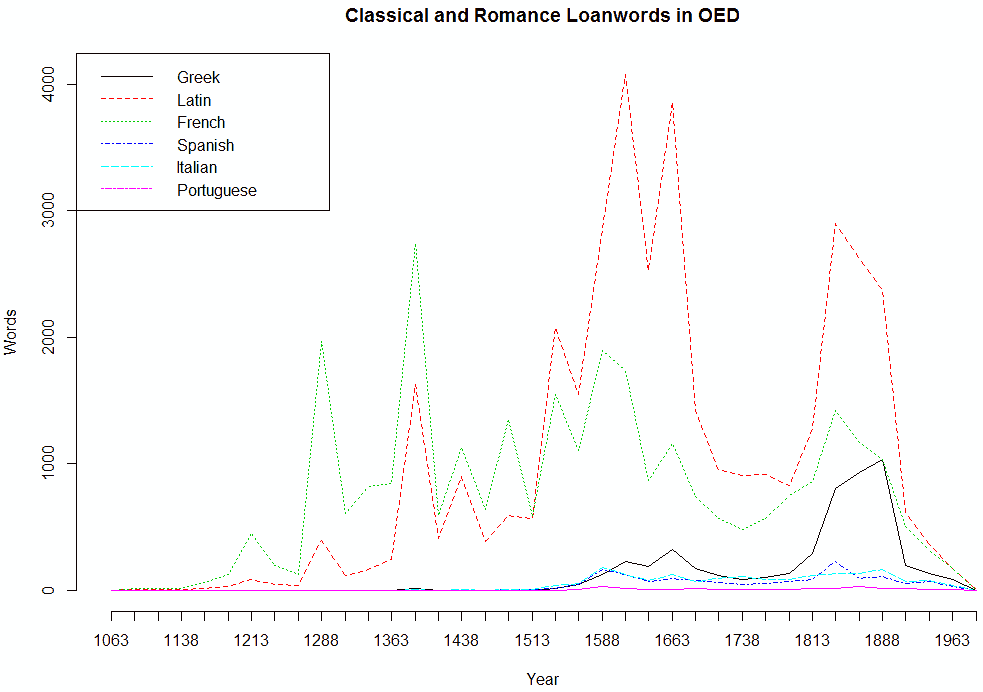

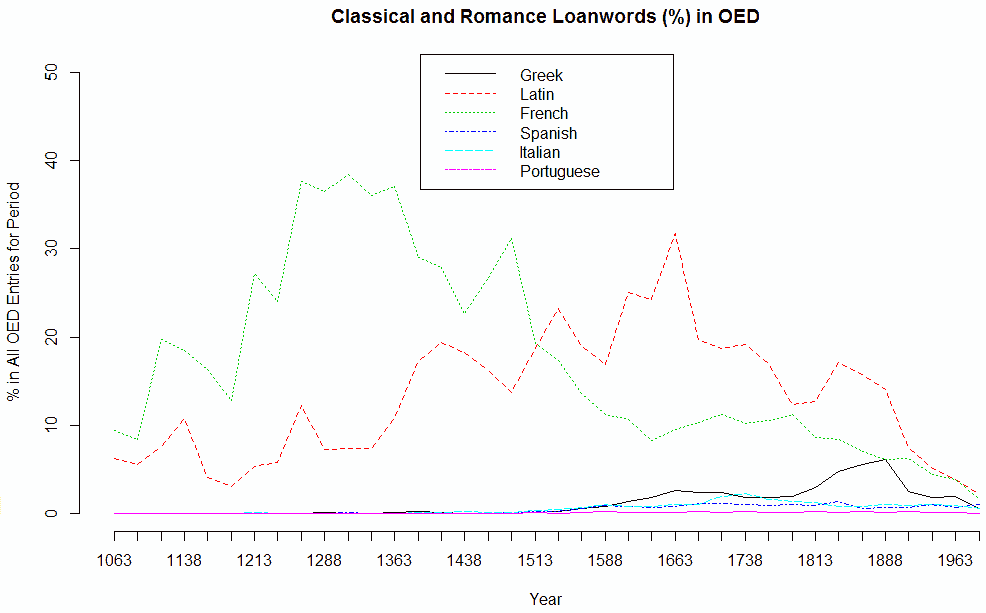

「#2357. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計」 ([2015-10-10-1]),「#2369. 英語史におけるイタリア語,スペイン語,ポルトガル語からの語彙借用の歴史」 ([2015-10-22-1]) で,Culpeper and Clapham (218) による OED ベースのロマンス系借用語の統計を紹介した.論文の巻末に,具体的な数値が表の形で掲載されているので,これを基にして2つグラフを作成した(データは,ソースHTMLを参照).1つめは4半世紀ごとの各言語からの借用語数,2つめはそれと同じものを,各時期の見出し語全体における百分率で示したものである.

関連する語彙統計として,「#2162. OED によるフランス語・ラテン語からの借用語の推移」 ([2015-03-29-1]) で触れた Wordorigins.org の "Where Do English Words Come From?" も参照.

・ Culpeper Jonathan and Phoebe Clapham. "The Borrowing of Classical and Romance Words into English: A Study Based on the Electronic Oxford English Dictionary." International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 1.2 (1996): 199--218.

2015-10-28 Wed

■ #2375. Anglo-French という補助線 (2) [semantics][semantic_change][semantic_borrowing][anglo-norman][french][lexicology][false_friend][methodology][borrowing][law_french]

昨日の記事 ([2015-10-27-1]) に引き続き,英語史研究上の Anglo-French の再評価についての話題.Rothwell は,英語語彙や中世英語文化の研究において,Anglo-French の役割をもっと重視しなければならないと力説する.研究道具としての MED の限界にも言い及ぶなど,中世英語の文献学者に意識改革を迫る主張が何度も繰り返される.フランス語彙の「借用」 (borrowing) という概念にも変革を迫っており,傾聴に値する.いくつか文章を引用したい.

The MED reveals on virtually every page the massive and conventional sense and that in literally thousands of cases forms and meanings were adopted (not 'borrowed') into English from Insular, as opposed to Continental, French. The relationship of Anglo-French with Middle English was one of merger, not of borrowing, as a direct result of the bilingualism of the literate classes in mediaeval England. (174)

The linguistic situation in mediaeval England . . . produced . . . a transfer based on the fact that generations of educated Englishmen passed daily from English into French and back again in the course of their work. Very many of the French terms they used had been developing semantically on English soil since 1066, were absorbed quite naturally with all their semantic values into the native English of those who used them and then continued to evolve in their new environment of Middle English. This is a very long way from the traditional idea of 'linguistic borrowing'. (179--80)

[I]n England . . . the social status of French meant that it was used extensively in preference to English for written records of all kinds from the twelfth to the fifteenth century. As a result, given that English was the native language of the majority of those who wrote this form of French, many hundreds of words would have been in daily use in spoken English for generations without necessarily being committed to parchment or paper, the people who used them being bilingual in varying degrees, but using only one of their two vernaculars --- French --- to set down in writing their decisions, judgements, transactions, etc., for posterity. (185)

昨日の記事では bachelor の「独身男性」の語義と apparel の「衣服」の語義の例を挙げた,もう1つ Anglo-French の補助線で解決できる事例として,Rothwell (184) の挙げている rape という語を取り上げよう.MED によると,「強姦」の意味での rāpe (n.(2)) は,英語では1425年の例が初出である.大陸のフランス語ではこの語は見いだされないのだが,Anglo-French では rap としてこの語義において13世紀末から文証される.

[A]s early as c. 1289 rape is defined in the French of the English lawyers as the forcible abduction of a woman; in c. 1292 the law defines it, again in French, as male violence against a woman's body. Therefore, for well over a century before the first attestation of 'rape' in Middle English, the law of England, expressed in French but executed by English justices, had been using these definitions throughout English society. rape is an Anglo-French term not found on the Continent. Admittedly, the Latin rapum is found even earlier than the French, but it was the widespread use of French in the actual pleading and detailed written accounts --- as distinct from the brief formal Latin record --- of cases in the English course of law from the second half of the thirteenth century onwards that has resulted in so very many English legal terms like rape having a French look about them. . . . As far as rape is concerned, there never was, in fact, a 'semantic vacuum' . . . .

Rothwell (184) は,ほかにも larceny を始め多くの法律用語に似たような状況が当てはまるだろうと述べている.中英語の語彙の研究について,まだまだやるべきことが多く残されているようだ.

・ Rothwell, W. "The Missing Link in English Etymology: Anglo-French." Medium Aevum 60 (1991): 173--96.

2015-10-23 Fri

■ #2370. ポルトガル語からの語彙借用 [portuguese][loan_word][borrowing][japanese]

昨日の記事「#2369. 英語史におけるイタリア語,スペイン語,ポルトガル語からの語彙借用の歴史」 ([2015-10-22-1]) に関連して,今回はとりわけポルトガル語からの借用語に焦点を当てよう.ポルトガルが海洋国家として世界に華々しく存在感を示した16世紀以降を中心として,以下のような借用語が英語へ入った (Strang 125, 宇賀治 113) .ルーツの世界性を感じることができる.

・ 新大陸より: coco(-nut) (ココヤシの木(の実)), macaw (コンゴウインコ), molasses (糖蜜[砂糖の精製過程に生じる黒色のシロップ]), sargasso (ホンダワラ類の海藻)

・ アフリカより: assagai/assegai ([南アフリカ先住民の]細身の投げ槍), guinea (ギニー(金貨)[1663--1813年間イギリスで鋳造された金貨;21 shillings に相当;本来アフリカ西部 Guinea 産の金でつくった]), madeira (マデイラワイン[ポルトガル領 Madeira 島原産の強く甘口の白ワイン]), palaver (口論;論議), yam (ヤマイモ)

・ インドより: buffalo (スイギュウ), cast(e) (カースト[インドの世襲階級制度]), emu (ヒクイドリ), joss (神像), tank ((貯水)タンク), typhoo (台風;後にギリシア語の影響で変形), verandah (ベランダ)

・ 中国より: mandarin ((中国清朝時代 (1616--1912) の)高級官吏), pagoda (パゴダ)

・ 日本より: bonze (坊主,僧)

ポルトガル本土に由来する借用語には moidore (モイドール[ポルトガル・スペインの昔の金貨;18世紀英国で通用]), port (ポート(ワイン))などがあるが,むしろ少数である.関連して「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1]) や「#756. 世界からの借用語」 ([2011-05-23-1]) で挙げた例も参照.

なお,日本語からポルトガル語を経由して英語に入った bonze は16世紀末の借用語だが,同じ時期に,ポルトガル語から日本語への語彙借用も起こっていたことに注意したい.借用語例は「#1896. 日本語に入った西洋語」 ([2014-07-06-1]) で挙げたとおりである.いずれも,当時のポルトガルの世界的な活動を映し出す鏡である.

2015-10-22 Thu

■ #2369. 英語史におけるイタリア語,スペイン語,ポルトガル語からの語彙借用の歴史 [italian][spanish][portuguese][loan_word][borrowing][statistics][lexicology]

「#2357. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計」 ([2015-10-10-1]) で少々触れたように,英語史上,フランス語に比して他の3つのロマンス諸語からの語彙借用は影が薄い.イタリア語,スペイン語,ポルトガル語の各言語からの借用語の例は,主に近代以降について「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1]) や「#756. 世界からの借用語」 ([2011-05-23-1]) で触れた.中英語にも,およそフランス語経由ではあるが,イタリア語やポルトガル語に起源をもつ語の借用があった (「#2329. 中英語の借用元言語」 ([2015-09-12-1])) .

Culpeper and Clapham (210) は,比較的マイナーなこれらのロマンス諸語からの語彙借用の歴史について,OED による語彙統計をもとに,次のように端的にまとめている.

The effect of Italian borrowing can be seen from the 15th century onwards. Italy was, and still is, famous for style in architecture and dress. It was also perceived an authority in matters to do with etiquette. Travellers to Italy --- often young sons dispatched to acquire some manners --- inevitably brought back Italian words. Italian borrowing is strongest in the 18th century (1.7% of recorded vocabulary), and is mostly related to musical terminology. Spanish and Portuguese borrowing commences in the 16th century, reflecting warfare, commerce, and colonisation, but at no point exceeds 1% of vocabulary recorded within a particular period.

まず,イタリア語からの借用語がある程度著しくなるのは,15世紀からである.「#1530. イングランド紙幣に表記されている Compa」 ([2013-07-05-1]) で言及したように,13世紀後半以降,16世紀まで,イタリアの先進的な商業・金融はイングランド経済に大きな影響を与えてきた.それが言語的余波となって顕われてきたのが,15世紀辺りからと解釈することができる.その後,イタリア借用語は18世紀の音楽用語の流入によってピークを迎えた.

一方,スペイン語とポルトガル語は,イタリア語よりもさらに目立たず,そのなかで比較的著しいといえるのは16世紀に限定される.当時,海洋国家として名を馳せた両雄の言語的な現われといえるだろう.

各言語からの語彙借用の様子は,統計的にみれば以上の通りだが,質的な違いを要約すると次の通りになる (Strang 124--26) .

(1) イタリア人は世界を開拓したり植民したりする冒険者ではなく,あくまでヨーロッパ内の旅人であった.したがって,イタリア語が提供した語彙も,ヨーロッパ的なものに限定されるといってよい.ルネサンスの発祥地ということもあり,芸術,音楽,文学,思想の分野の語彙を多く提供したことはいうまでもないが,文物を通してというよりは広い意味での旅人の口を経由して,それらの語彙が英語へ流入したとみるべきだろう.語形としては,あたかもフランス語を経由したような形態を取っていることが多い.

(2) 一方,スペイン語の流入は,イングランド女王 Mary とスペイン王 Philip II の結婚による両国の密な関係に負うところが多く,スペイン本土のみならず,新大陸に由来する語彙の少なくないことも特徴である.

(3) スペイン語以上に世界的な借用語を提供したのは,15--16世紀に航海術を発達させ,世界へと展開したポルトガルの言語である.ポルトガル語は,新大陸のみならず,アフリカやアジアからも多くの語彙をヨーロッパに持ち帰り,それが結果として英語にもたらされた.

具体的な借用語の例は,「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Culpeper Jonathan and Phoebe Clapham. "The Borrowing of Classical and Romance Words into English: A Study Based on the Electronic Oxford English Dictionary." International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 1.2 (1996): 199--218.

・ Strang, Barbara M. H. A History of English. London: Methuen, 1970.

2015-10-13 Tue

■ #2360. 20世紀のフランス借用語 [french][loan_word][borrowing][statistics][norman_french][creole][oed]

英語のフランス語との付き合いは古英語最末期より途切れることなく続いている.フランス語彙借用のピークは「#2357. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計」 ([2015-10-10-1]) や「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1]) で見たように1251--1375年だが,その後も,規模こそ縮小しながらも,借用は連綿と続いてきている.中英語以降の各時代のフランス語彙の借用については,「#1210. 中英語のフランス借用語の一覧」 ([2012-08-19-1]),「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1]),「#594. 近代英語以降のフランス借用語の特徴」 ([2010-12-12-1]), 「#678. 汎ヨーロッパ的な18世紀のフランス借用語」 ([2011-03-06-1]) を参照されたい.

今回は,現代英語におけるフランス借用語の話題を取り上げたい.Schultz は,OED Online を利用して,1900年以降に英語に入ってきたフランス語彙を調査した.Schultz がフランス借用語として取り出し,認定したのは,1677語である.Schultz の論文では,それらを14個の意味分野(とさらなる下位区分)ごとに整理し,サンプル語を列挙しているが,ここでは12分野それぞれに属する語の数と割合のみを示そう (Shultz 4--6) .

(1) Anthropology (11 borrowings, i.e. 0.7%)

(2) Metapsychics and parapsychology (11 borrowings, i.e. 0.7%)

(3) Archaeology (30 borrowings, i.e. 1.8%)

(4) Miscellaneous (46 borrowings, i.e. 2.7%)

(5) Technology (62 borrowings, i.e. 3.7%)

(6) La Francophonie (63 borrowings, i.e. 3.8%)

(7) Fashion and lifestyle (77 borrowings, i.e. 4.6%)

(8) Entertainment and leisure activities (86 borrowings, i.e. 5.1%)

(9) Mathematics and the humanities (92 borrowings, i.e. 5.5%)

(10) People and everyday life (154 borrowings, i.e. 9.2%)

(11) Civilization and politics (156 borrowings, i.e. 9.3%)

(12) Gastronomy (179 borrowings, i.e. 10.7%)

(13) Fine arts and crafts (260 borrowings, i.e. 15.5%)

(14) The natural sciences (450 borrowings, i.e. 26.8%)

20世紀のフランス借用語の特徴は何だろうか.1つは,Schultz が "the vocabulary recently adopted from French is characterized by its great variety, ranging from words related to everyday matters to highly specific terms in technology and science" (8) とまとめているように,意味分野の幅広さが挙げられる.食,芸術,自然科学が相対的に強いが,全体としてはマルチジャンルといってよい.ただし,マルチジャンルであることは中英語期のフランス借用語の特徴にも当てはまることから,これは英語史におけるフランス語彙借用に汎時的にみられる特徴といってもよいかもしれない.

注目すべきは,借用語のソースとして,標準フランス語のみならず,フランス語の諸変種やクレオール語なども含まれていることだ.カリブ諸島,カナダ,ルイジアナ,アフリカなどのフランス語変種からの借用語が少なくない.中英語期にも,中央フランス語のみならず,とりわけ初期にノルマン・フランス語 (norman_french) からも語彙が流入していたが,近代以降「フランス語」の指す範囲が拡がるとともに,借用元変種も多様化してきたということだろう.

現代世界の借用元言語としての英語を考えてみても,従来はイギリス標準英語やアメリカ標準英語がほぼ唯一の借用元変種だったかもしれないが,現在ではピジン語やクレオール語も含めた各種の英語変種が借用元変種となっている事実がある.それと同じことが,フランス語についても言えるということなのではないか.

・ Schultz, Julia. "Twentieth-Century Borrowings from french into English --- An Overview." English Today 28.2 (2012): 3--9.

2015-10-12 Mon

■ #2359. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由 (3) [history][loan_word][lexicology][borrowing][linguistic_imperialism][language_myth][purism]

標題と関連して,「#134. 英語が民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2009-09-08-1]),「#1366. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2013-01-22-1]),「#1845. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由 (2)」 ([2014-05-16-1]) で様々な見解を紹介してきた.今回は,主として英語が歴史的に他言語から多くの語彙を借用してきた事実に照らして,英語の民主性・非民主性について考えてみたい.

英語が多くの言語からおびただしい語彙を借用してきたことは,言語的純粋主義 (purism) の立場からの批判が皆無ではないにせよ,普通は好意的に語られる.英語の語彙借用好きは,ほとんどすべての英語史記述でも強調される特徴であり,これを指して "cosmopolitan vocabulary" などと持ち上げられることが多い.続けて,英語,そして英語国民は,柔軟にして鷹揚,外に対して開かれており,多様性を重んじる伝統を有すると解釈されることが多い.歴史的に英語国では言語を統制するアカデミーが設立されにくかったこともこの肯定的な議論に一役買っているだろう.また,もう1つの国際語であるフランス語が上記の点で英語と反対の特徴を示すことからも,相対的に英語の「民主性」が浮き彫りになる.

しかし,英語の民主性に関する肯定的なイメージはそれ自体が作られたイメージであり,語彙借用のある側面を反映していないという.Bailey (91) によれば,植民地帝国主義時代の英国人は,その人種的優越感ゆえに,諸言語からの語彙をやみくもに受け入れたわけではなく,むしろすでに他のヨーロッパ人が受け入れていた語彙についてのみ自らの言語へ受け入れることを許したという.これが事実だとすれば,英語(国民)はむしろ非民主的であると言えるかもしれない.

Far from its conventional image as a language congenial to borrowing from remote languages, English displays a tendency to accept exotic loanwords mainly when they have first been adopted by other European languages or when presented with marginal social practices or trivial objects. Anglophones who have ventured abroad have done so confident of the superiority of their culture and persuaded of their capacity for adaptation, usually without accepting the obligations of adapting. Extensive linguistic borrowing and language mixing arise only when there is some degree of equality between or among languages (and their speakers) in a multilingual setting. For the English abroad, this sense of equality was rare. Whether it is a language more "friendly to change than other languages" has hardly been questioned; those who embrace the language are convinced that English is a capacious, cosmopolitan language superior to all others.

Bailey によれば,「開かれた民主的な英語」のイメージは,それ自体が植民地主義の産物であり,植民地主義時代の語彙借用の事実に反するということになる.

ただし,Bailey の植民地主義と語彙借用の議論は,主として近代以降の歴史に関する議論であり,英語が同じくらい頻繁に語彙借用を行ってきたそれ以前の時代の議論には直接触れていないことに注意すべきだろう.中英語以前は,英語はラテン語やフランス語から多くの語彙を借り入れなければならない,社会的に下位の言語だったのであり,民主的も非民主的も論ずるまでもない言語だったのだから.

・ Bailey, R. Images of English. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1991.

2015-10-10 Sat

■ #2357. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計 [oed][statistics][lexicology][loan_word][borrowing][latin][greek][french][italian][spanish][portuguese][romancisation]

標題に関する,OED2 の CD-ROM 版を用いた本格的な量的研究を発見した.Culpeper and Clapham によるもので,調査方法を見るかぎり,語源欄検索の機能を駆使し,なるべく雑音の混じらないように腐心したようだ.OED などを利用した量的研究の例は少なくないが,方法論の厳密さに鑑みて,従来の調査よりも信頼のおける結果として受け入れてよいのではないかと考える.もっとも,筆者たち自身が OED を用いて語彙統計を得ることの意義や陥穽について慎重に論じており,結果もそれに応じて慎重に解釈しなければいけないことを力説している.したがって,以下の記述も,その但し書きを十分に意識しつつ解釈されたい.

Culpeper and Clapham の扱った古典語およびロマンス諸語とは,具体的にはラテン語,ギリシア語,フランス語,イタリア語,スペイン語,ポルトガル語を中心とする言語である.数値としてある程度の大きさになるのは,最初の4言語ほどである.筆者たちは,OED 掲載の2,314,82の見出し語から,これらの言語を直近の源とする借用語を77,335語取り出した.これを時代別,言語別に整理し,タイプ数というよりも,主として当該時代に初出する全語彙におけるそれらの借用語の割合を重視して,各種の語彙統計値を算出した.

一つひとつの数値が示唆的であり,それぞれ吟味・解釈していくのもおもしろいのだが,ここでは Culpeper and Clapham (215) が論文の最後で要約している主たる発見7点を引用しよう.

(1) Latin and French have had a profound effect on the English lexicon, and Latin has had a much greater effect than French.

(2) Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese are of relatively minor importance, although Italian experienced a small boost in the 18th century.

(3) The general trend is one of decline in borrowing from Classical and Romance languages. In the 17th century, 39.3% of recorded vocabulary came from Classical and Romance languages, whereas today the figure is 15%.

(4) Latin borrowing peaked in 1600--1675, and Latin contributed approximately 7000 words to the English lexicon during the 16th century.

(5) Greek, coming after Latin and French in terms of overall quantity, peaked in the 19th century.

(6) French borrowing peaked in 1251--1375, fell below the level of Latin borrowing around 1525, and thereafter declined except for a small upturn in the 18th century. French contributed over 11000 words to the English lexicon during the Middle English period.

(7) Today, borrowing from Latin may have a slight lead on borrowing from French.

この7点だけをとっても,従来の研究では曖昧だった調査結果が,今回は数値として具体化されており,わかりやすい.(1) は,フランス語とラテン語で,どちらが量的に多くの借用語彙を英語にもたらしてきたかという問いに端的に答えるものであり,ラテン語の貢献のほうが「ずっと大きい」ことを明示している.(7) によれば,そのラテン語の優位は,若干の差ながらも,現代英語についても言えるようだ.関連して,(6) から,最大の貢献言語がフランス語からラテン語へ切り替わったのが16世紀前半であることが判明するし,(4) から,ラテン語のピークは16世紀というよりも17世紀であることがわかる.

(3) では,近代以降,新語における借用語の比率が下がってきていることが示されているが,これは「#879. Algeo の新語ソース調査から示唆される通時的傾向」([2011-09-23-1]) でみたことと符合する.(2) と (5) では,ラテン語とフランス語以外の諸言語からの影響は,全体として僅少か,あるいは特定の時代にやや顕著となったことがある程度であることもわかる.

英語史における借用語彙統計については,cat:lexicology statistics loan_word の各記事を参照されたい.本記事と関連して,特に「#2162. OED によるフランス語・ラテン語からの借用語の推移」 ([2015-03-29-1]) を参照.

・ Culpeper Jonathan and Phoebe Clapham. "The Borrowing of Classical and Romance Words into English: A Study Based on the Electronic Oxford English Dictionary." International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 1.2 (1996): 199--218.

2015-10-08 Thu

■ #2355. フランス語の語彙以外への影響 --- 句,綴字,派生形態論,強勢 [french][contact][borrowing][derivation][stress][hybrid][rsr]

英語史では,フランス語は語彙の領域には多大な影響を及ぼしたが,それ以外では見るものが少ないと言われることがある.しかし,「#2351. フランス語からの句動詞の借用」 ([2015-10-04-1]) で見たように句の単位でも少なからぬ影響を及ぼしてきたし,綴字の領域にも大きな衝撃を与えてきた.

とはいえ,文法や音韻については,フランス語がたいした影響を与えて来なかったことは事実だろう.以下にリンクを張った記事で触れてきたように,影響が考えられ得る項目もいくつか指摘されているが,強い証拠のないものが多い.一方,ノルマン征服以後,フランス語は英語の社会的な地位をおとしめることにより,結果として下位言語としての英語の文法変化を促進させたという意味で,間接的な影響を及ぼしたと言うことはできるだろう.

・ 「#204. 非人称構文」 ([2009-11-17-1])

・ 「#1171. フランス語との言語接触と屈折の衰退」 ([2012-07-11-1])

・ 「#1208. フランス語の英文法への影響を評価する」 ([2012-08-17-1])

・ 「#1222. フランス語が英語の音素に与えた小さな影響」 ([2012-08-31-1])

・ 「#1815. 不定代名詞 one の用法はフランス語の影響か?」 ([2014-04-16-1])

・ 「#1884. フランス語は中英語の文法性消失に関与したか」 ([2014-06-24-1])

・ 「#1924. フランス語は中英語の文法性消失に関与したか (2)」 ([2014-08-03-1])

・ 「#2047. ノルマン征服の英語史上の意義」 ([2014-12-04-1])

・ 「#2347. 句比較の発達におけるフランス語,ラテン語の影響について」 ([2015-09-30-1])

さて,連日,参照・引用している Denison and Hogg (17) は,フランス語の語彙以外への影響という問題に関して,全体的には僅少であることを前提としながらも,派生形態論と強勢の領域においては見るものがあると指摘する.

. . . we should . . . look at French influence outside the borrowing of vocabulary. It is best to start by saying that French influence is largely absent from inflectional morphology. The only possibilities concern the eventual domination of the plural inflection -s at the expense of -en (hence shoes rather than shoon) and the rise of the personal pronoun one. Although there are parallels in French, it is virtually certain that the English developments are entirely independent.

The strongest influence of French can be best seen in two other areas, apparently unrelated but in fact closely connected to each other. These are: (i) derivational morphology; (ii) stress.

フランス語の派生形態論への影響を確認するには,「#96. 英語とフランス語の素材を活かした 混種語 ( hybrid )」 ([2009-08-01-1]) に挙げたような混種語 (hybrid) の例を見れば十分だろう.強勢については,「#718. 英語の強勢パターンは中英語期に変質したか」 ([2011-04-15-1]) や rsr (= Romance Stress Rule) に関する各記事を参照されたい.派生形態論と強勢という2つの領域が "closely connected" であるというのは,現代英語の語形成規則と強勢規則の適用が,語根がゲルマン系かロマンス系かによって層別されている事実を指すものと理解できる.

まとめると,フランス語の語彙以外への影響として,ある程度注目すべきものといえば,句,綴字,派生形態論,強勢といったところだろうか.

・ Denison, David and Richard Hogg. "Overview." Chapter 1 of A History of the English Language. Ed. Richard Hogg and David Denison. Cambridge: CUP, 2006. 1--42.

2015-10-04 Sun

■ #2351. フランス語からの句動詞の借用 [french][loan_translation][borrowing][contact][phrasal_verb][phraseology]

中英語期におけるフランス語彙借用については,本ブログでも「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1]),「#1210. 中英語のフランス借用語の一覧」 ([2012-08-19-1]) ほか french loan_word の各記事で様々に扱ってきた.しかし,フランス語からの句動詞 (phrasal_verb) の借用,より正確には翻訳借用 (loan_translation or calque) についてはあまり取り上げてこなかったので,ここで話題にしたい.

フランス語の句動詞をはじめとする複数語からなる各種表現が,少なからず英語に翻訳借用されてきたことについては,種々の先行研究でも触れられてきた.例えば,Iglesias-Rábade の参照した F. H. Sykes (French Elements in Middle English. Oxford: 1899.) や A. A. Prins (French Influence in English Phrasing. Leiden: 1952.) によれば,623ほどの句がフランス語由来と推定できるとしている (ex. take lond (< OF prendre terre (disembark))) .しかし,実証的な研究は少なく,本当にフランス語の表現のなぞりなのかどうか,実は英語における自然な発達としてとらえることも可能ではないか,など議論が絶えない.

そこで,Iglesias-Rábade は nime(n)/take(n) を用いた句動詞表現に的を絞り,この動詞が "light verb" あるいは "operator" として作用し,その後に動詞派生名詞あるいは前置詞+動詞派生名詞を伴う構文を MED より拾い出したうえで,当時のフランス語に対応表現があるかどうかを確認する実証的な研究をおこなった.研究対象となる2つの構文を厳密に定義すると,以下の通りである.

(1) Verbal phrases made of a 'light' V(erb) + deverbal noun: e.g. take(n) ende, take(n) dai, nime(n) air

(2) The 'light' verb nime(n)/take(n) + a 'prepositional' deverbal: e.g. take(n) in gree, take(n) to herte, take(n) in cure

(1) の型については,306の句が収集され,そのうち49個がフランス語からの意味借用であり,156個がフランス語に似た表現がみつかるというものであるという (Iglesias-Rábade 96) .(1) の型については,型自体は古英語からあるものの,フランス語の多くの句によって英語での種類や使用が増したとはいえるだろうとしている (99) .

. . . this syntactic pattern acquired great popularity in lME with extensive use and a varied typology. I do not claim that this construction is a French imprint, because it occurred in OE, but in my opinion French contributed decisively to the use of this type of structure consisting of a light verb translated from French + a deverbal element which bears the action and the lexical meaning and which usually kept the French form and content.

(2) の型については,Iglesias-Rábade (99) は,型自体も一部の句を除けば一般的に古英語に遡るとは言いにくく,概ねフランス語(あるいはラテン語)の翻訳借用と考えるのが妥当だとしている.

This pattern, too, dates from OE, though it was restricted to the verb niman + an object preceded by on, e.g. on gemynd niman ('to bear in mind'). However, this construction came to be much more frequent in lME, particularly with sequences which had no prototype in OE, and, more intriguingly, most of them were a calque in both form and content from French and/or Latin.

興味深いのは,いずれの型についても,句の初出が14世紀後半から15世紀にかけてピークを迎えるということだ.単体のフランス借用語も数的なピークが14世紀後半に来たことを考えると,その少し後を句の借用のピークが追いかけてきたように見える.実際,句に含まれる名詞は借用語であることが多い.Iglesias-Rábade (104) は,より一般化して "It seems plausible that the introduction of foreign single words precedes the incorporation of foreign phrases, turns of speech, proverbial sayings and idioms." ととらえている.

これらの句が英語に入ってきた経路について,Iglesias-Rábade は,英仏語の2言語使用者が日常の話し言葉においてもたらしたというよりは,翻訳文書において初出することが多いことから,主として書き言葉経由で流入したと考えている (100).結論として,p. 104 では次のように述べられている.

To conclude, I believe that English had borrowed from French an important bulk of phrases and turns of speech which today are considered to be part of daily speech. In my opinion phrasal structures of this type must have been rather artificial and removed from everyday speech when they first appeared in late ME works. I base this conclusion on the fact that such phrases were not common in a contemporary specimen of colloquial speech, the Towneley Plays . . . . I thus suggest that most of them made their way into English via literature and the translation process, rather than through the natural process of social bilingual speech. It is worth noting that most ME literature is based on French patterns or French matter. Most of this phrasal borrowing was the natural product of translation and composition.

Iglesias-Rábade の議論を受け入れて,これらのフランス語の句が書き言葉を経由した借用だったとして,次の疑問は,それが後に話し言葉へ浸透していったのは,いかなる事情があってのことだろうか.

関連して,「#2349. 英語の復権期にフランス借用語が爆発したのはなぜか (2)」 ([2015-10-02-1]) と,そこに張ったリンク先の記事も参照.

・ Iglesias-Rábade, Luis. "French Phrasal Power in Late Middle English." Multilingualism in Later Medieval Britain. Ed. D. A. Trotter. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000. 93--130.

2015-10-02 Fri

■ #2349. 英語の復権期にフランス借用語が爆発したのはなぜか (2) [reestablishment_of_english][language_shift][french][loan_word][borrowing][bilingualism][borrowing][lexicology][statistics][contact]

標記の問題については,以下の一連の記事などで取り上げてきた.

・ 「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1])

・ 「#1205. 英語の復権期にフランス借用語が爆発したのはなぜか」 ([2012-08-14-1])

・ 「#1209. 1250年を境とするフランス借用語の区分」 ([2012-08-18-1])

・ 「#1540. 中英語期における言語交替」 ([2013-07-15-1])

・ 「#1638. フランス語とラテン語からの大量語彙借用のタイミングの共通点」 ([2013-10-21-1])

・ 「#2069. 言語への忠誠,言語交替,借用方法」 ([2014-12-26-1])

この問題に関連して,Rothwell の論文を読んだ.Rothwell (50) によると,中英語のあいだに公的な記録の言語が,ラテン語からフランス語へ,フランス語から英語へ目まぐるしく切り替わった言語交替 (language_shift) という社会言語学的な視点を考慮しなければならないという.

If the English language appears to embark on a far more extensive campaign of lexical borrowing from the later fourteenth century, this is because French had become the second official language of record in England, alongside and often in replacement of Latin. This means in effect that from the thirteenth century onwards French is called upon to cover a much wider range of registers than in the earlier period, when it was used in the main for works of entertainment or edification. This change in the role of French took place at a time when English was debarred from use as a language of record, so that when English in its turn began to take on that role in the later fourteenth century, it was only to be expected that it would retain much of the necessary vocabulary used by its predecessor --- French. . . . For successive generations of countless English scribes and officials the administrative vocabulary of French had been an integral part of their daily life and work; it would be unrealistic to expect them to jettison it and re-create an entirely new Germanic set of terms when English came in to take over the role hitherto played by French.

13--14世紀にかけて,フランス語が法律関係を始めとする公的な言語としての役割を強めていくことは,「#2330. 13--14世紀イングランドの法律まわりの使用言語」 ([2015-09-13-1]) でみた.このようにイングランドにおいてフランス語で公的な記録が取られる慣習が数世代にわたって確立していたところに,14世紀後半,英語が復権してきたのである.書き言葉上のバイリンガルだったとはいえ,多くの写字生にとって,当初この言語交替には戸惑いがあったろう.特に政治や法律に関わる用語の多くは,これまでフランス単語でまかなってきており,対応する英語本来語は欠けていた.このような状況下で,写字生が書き言葉を英語へとシフトする際に,書き慣れたフランス語の用語を多用したことは自然だった.

後期中英語における各言語の社会言語学的な位置づけと,言語間の語彙借用の様相は,このように密接に結びついている.関連する最近の話題として,「#2345. 古英語の diglossia と中英語の triglossia」 ([2015-09-28-1]) も参照.

・ Rothwell, W. "Stratford atte Bowe and Paris." Modern Language Review 80 (1985): 39--54.

2015-10-02 Fri

■ #2349. 英語の復権期にフランス借用語が爆発したのはなぜか (2) [reestablishment_of_english][language_shift][french][loan_word][borrowing][bilingualism][borrowing][lexicology][statistics][contact]

標記の問題については,以下の一連の記事などで取り上げてきた.

・ 「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1])

・ 「#1205. 英語の復権期にフランス借用語が爆発したのはなぜか」 ([2012-08-14-1])

・ 「#1209. 1250年を境とするフランス借用語の区分」 ([2012-08-18-1])

・ 「#1540. 中英語期における言語交替」 ([2013-07-15-1])

・ 「#1638. フランス語とラテン語からの大量語彙借用のタイミングの共通点」 ([2013-10-21-1])

・ 「#2069. 言語への忠誠,言語交替,借用方法」 ([2014-12-26-1])

この問題に関連して,Rothwell の論文を読んだ.Rothwell (50) によると,中英語のあいだに公的な記録の言語が,ラテン語からフランス語へ,フランス語から英語へ目まぐるしく切り替わった言語交替 (language_shift) という社会言語学的な視点を考慮しなければならないという.

If the English language appears to embark on a far more extensive campaign of lexical borrowing from the later fourteenth century, this is because French had become the second official language of record in England, alongside and often in replacement of Latin. This means in effect that from the thirteenth century onwards French is called upon to cover a much wider range of registers than in the earlier period, when it was used in the main for works of entertainment or edification. This change in the role of French took place at a time when English was debarred from use as a language of record, so that when English in its turn began to take on that role in the later fourteenth century, it was only to be expected that it would retain much of the necessary vocabulary used by its predecessor --- French. . . . For successive generations of countless English scribes and officials the administrative vocabulary of French had been an integral part of their daily life and work; it would be unrealistic to expect them to jettison it and re-create an entirely new Germanic set of terms when English came in to take over the role hitherto played by French.

13--14世紀にかけて,フランス語が法律関係を始めとする公的な言語としての役割を強めていくことは,「#2330. 13--14世紀イングランドの法律まわりの使用言語」 ([2015-09-13-1]) でみた.このようにイングランドにおいてフランス語で公的な記録が取られる慣習が数世代にわたって確立していたところに,14世紀後半,英語が復権してきたのである.書き言葉上のバイリンガルだったとはいえ,多くの写字生にとって,当初この言語交替には戸惑いがあったろう.特に政治や法律に関わる用語の多くは,これまでフランス単語でまかなってきており,対応する英語本来語は欠けていた.このような状況下で,写字生が書き言葉を英語へとシフトする際に,書き慣れたフランス語の用語を多用したことは自然だった.

後期中英語における各言語の社会言語学的な位置づけと,言語間の語彙借用の様相は,このように密接に結びついている.関連する最近の話題として,「#2345. 古英語の diglossia と中英語の triglossia」 ([2015-09-28-1]) も参照.

・ Rothwell, W. "Stratford atte Bowe and Paris." Modern Language Review 80 (1985): 39--54.

2015-10-01 Thu

■ #2348. 英語史における code-switching 研究 [code-switching][me][emode][bilingualism][contact][latin][french][literature][borrowing][genre][historical_pragmatics][discourse_analysis]

本ブログでは code-switching (CS) に関していくつかの記事を書いてきた.とりわけ英語史の視点からは,「#1470. macaronic lyric」 ([2013-05-06-1]),「#1625. 中英語期の書き言葉における code-switching」 ([2013-10-08-1]),「#1941. macaronic code-switching としての語源的綴字?」 ([2014-08-20-1]),「#2271. 後期中英語の macaronic な会計文書」 ([2015-07-16-1]) で論じてきた.現代語の CS に関わる研究の発展に後押しされる形で,また歴史語用論 (historical_pragmatics) の流行にも支えられる形で,歴史的資料における CS の研究も少しずつ伸びてきているようであり,英語史においてもいくつか論文集が出されるようになった.

しかし,歴史英語における CS の実態は,まだまだ解明されていないことが多い.そもそも,CS が観察される歴史テキストはどの程度残っているのだろうか.Schendl は,中英語から初期近代英語にかけて,複数言語が混在するテキストは決して少なくないと述べている.

There is a considerable number of mixed-language texts from the ME and the EModE periods, many of which show CS in mid-sentence. The phenomenon occurs across genres and text types, both literary and non-literary, verse and prose; and the languages involved mirror the above-mentioned multilingual situation. In most cases Latin as the 'High' language is one of the languages, with one or both of the vernaculars English and French as the second partner, though switching between the two vernaculars is also attested. (79)

CS in written texts was clearly not an exception but a widespread specific mode of discourse over much of the attested history of English. It occurs across domains, genres and text types --- business, religious, legal and scientific texts, as well as literary ones. (92)

ジャンルを問わず,様々なテキストに CS が見られるようだ.文学テキストとしては,具体的には "(i) sermons; (ii) other religious prose texts; (iii) letters; (iv) business accounts; (v) legal texts; (vi) medical texts" が挙げられており,非文学テキストとしては "(i) mixed or 'macaronic' poems; (ii) longer verse pieces; (iii) drama; (iv) various prose texts" などがあるとされる (Schendl 80) .

英語史あるいは歴史言語学において CS (を含むテキスト)を研究する意義は少なくとも3点ある.1つは,過去の2言語使用と言語接触の状況の解明に資する点だ.2つめは,CS と借用の境目を巡る問題に関係する.語彙借用の多い英語の歴史にとって,借用の過程を明らかにすることは,理論的にも実際的にも極めて重要である (see 「#1661. 借用と code-switching の狭間」 ([2013-11-13-1]),「#1985. 借用と接触による干渉の狭間」 ([2014-10-03-1]),「#1988. 借用語研究の to-do list (2)」 ([2014-10-06-1]),「#2009. 言語学における接触,干渉,2言語使用,借用」 ([2014-10-27-1])) .3つめに,共時的な CS 研究に通時的な次元を与えることにより,理論を深化させることである.

・ Schendl, Herbert. "Linguistic Aspects of Code-Switching in Medieval English Texts." Multilingualism in Later Medieval Britain. Ed. D. A. Trotter. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000. 77--92.

2015-09-12 Sat

■ #2329. 中英語の借用元言語 [borrowing][loan_word][me][lexicology][contact][latin][french][greek][italian][spanish][portuguese][welsh][cornish][dutch][german][bilingualism]

中英語の語彙借用といえば,まずフランス語が思い浮かび (「#1210. 中英語のフランス借用語の一覧」 ([2012-08-19-1])),次にラテン語が挙がる (「#120. 意外と多かった中英語期のラテン借用語」 ([2009-08-25-1]), 「#1211. 中英語のラテン借用語の一覧」 ([2012-08-20-1])) .その次に低地ゲルマン語,古ノルド語などの言語名が挙げられるが,フランス語,ラテン語の陰でそれほど著しくは感じられない.

しかし,実際のところ,中英語は上記以外の多くの言語とも接触していた.確かにその他の言語からの借用語の数は多くはなかったし,ほとんどが直接ではなく,主としてフランス語を経由して間接的に入ってきた借用語である.しかし,多言語使用 (multilingualism) という用語を広い意味で取れば,中英語イングランド社会は確かに多言語使用社会だったといえるのである.中英語における借用元言語を一覧すると,次のようになる (Crespo (28) の表を再掲) .

| LANGUAGES | Direct Introduction | Indirect Introduction |

| Latin | --- | |

| French | --- | |

| Scandinavian | --- | |

| Low German | --- | |

| High German | --- | |

| Italian | through French | |

| Spanish | through French | |

| Irish | --- | |

| Scottish Gaelic | --- | |

| Welsh | --- | |

| Cornish | --- | |

| Other Celtic languages in Europe | through French | |

| Portuguese | through French | |

| Arabic | through French and Spanish | |

| Persian | through French, Greek and Latin | |

| Turkish | through French | |

| Hebrew | through French and Latin | |

| Greek | through French by way of Latin |

「#392. antidisestablishmentarianism にみる英語のロマンス語化」 ([2010-05-24-1]) で引用した通り,"French acted as the Trojan horse of Latinity in English" という謂いは事実だが,フランス語は中英語期には,ラテン語のみならず,もっとずっと多くの言語からの借用の「窓口」として機能してきたのである.

関連して,「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1]),「#516. 直接のギリシア語借用は15世紀から」 ([2010-09-25-1]),「#2164. 英語史であまり目立たないドイツ語からの借用」 ([2015-03-31-1]) も参照.

・ Crespo, Begoña. "Historical Background of Multilingualism and Its Impact." Multilingualism in Later Medieval Britain. Ed. D. A. Trotter. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000. 23--35.

2015-04-20 Mon

■ #2184. 英単語とフランス単語の相違 (2) [french][norman_french][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology][norman_conquest][false_friend]

昨日の記事「#2183. 英単語とフランス単語の相違 (1)」 ([2015-04-19-1]) に引き続いての話題.昨日は,英仏語の対応語の形や意味のズレの謎を解くべく,(1) 語彙の借用過程 (borrowing) に起こりがちな現象に注目した.今回は,(2) フランス語彙の借用の時期とその後の言語変化,(3) 借用の対象となったフランス語の方言という2つの視点を導入する.

まずは (2) について.英語とフランス語の対応語を比較するときに抱く違和感の最大の原因は,時間差である.私たちが比較しているのは,通常,現代英語と現代フランス語の対応語である.しかし,フランス単語が英語へ借用されたのは,大多数が中英語期においてである (cf. 「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1])) .つまり,6--8世紀ほど前のフランス語彙が6--8世紀ほど前の英語に流れ込んだ.昨日の記事でみたように,当時の借用過程においてすら model となるフランス単語と loan となる英単語のあいだに多少のギャップの生じるのが普通だったのであるから,ましてや当時より数世紀を経た現代において両言語の対応語どうしが形や意味においてピタッと一致しないのは驚くことではない.この6--8世紀のあいだに,その語の形や意味は,フランス語側でも英語側でも独自に変化している可能性が高い.

例えば,英語 doubt はフランス語 douter に対応するが,綴字は異なる.英単語の綴字に <b> が挿入されているのは英語における革新であり,この綴字習慣はフランス語では定着しなかった (cf. 「#1187. etymological respelling の具体例」 ([2012-07-27-1])) .またフランス語 journée は「1日」の意味だが,対応する英語の journey は「旅行」である.英語でも中英語期には「1日」の語義があったが,後に「1日の移動距離」を経て「旅行」の語義が発展し,もともとの語義は廃れた.数世紀の時間があれば,ちょっとしたズレが生じるのはもちろんのこと,初見ではいかに対応するのかと疑わざるを得ないほど,互いにかけ離れた語へと発展する可能性がある.

次に,(3) 借用の対象となったフランス語の方言,という視点も非常に重要である.数十年前ではなく数世紀前に入ったという時代のギャップもさることながら,フランス語借用の源が必ずしもフランス語の中央方言(標準フランス語)ではないという事実がある.私たちが学習する現代フランス語は中世のフランス語の中央方言に由来しているが,とりわけ初期中英語期に英語が借用したフランス語彙の多くは実はフランス北西部に行われていたノルマン・フレンチ (norman_french) である (cf. 「#1209. 1250年を境とするフランス借用語の区分」 ([2012-08-18-1])) .要するに,当時の「訛った」フランス単語が英単語として借用されて現在に至っているのであり,それと現代標準フランス語とを比較したときに,ズレが感じられるのは当然である.現代のフランス語母語話者の視点から現代英語の対応語を眺めると,「なぜ英語は大昔の,しかも訛ったフランス単語を用いているのだろうか」と首をかしげたくなる状況がある.具体的な事例については,「#76. Norman French vs Central French」 ([2009-07-13-1]),「#95. まだある! Norman French と Central French の二重語」 ([2009-07-31-1]),「#388. もっとある! Norman French と Central French の二重語」 ([2010-05-20-1]) などを参照されたい.

以上,2回にわたって英単語とフランス単語の相違の原因について解説してきた.両者のギャップは,(1) 借用過程そのものに起因するものもあれば,(2) 借用の生じた時代が数世紀も前のことであり,その後の両言語の歴史的発展の結果としてとらえられる場合もあるし,(3) 借用当時の借用ソースがフランス語の非標準方言だったという事実によるものもある.現代英単語と現代フランス単語とを平面的に眺めているだけでは見えてこない立体的な奥行を,英語史を通じて感じてもらいたい.

2015-04-19 Sun

■ #2183. 英単語とフランス単語の相違 (1) [french][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology][norman_conquest][false_friend]

英語史概説の授業などで,現代英語の語彙にいかに多くのフランス単語が含まれているかを話題にすると,初めて聞く学生は一様に驚く.大雑把にいって英語語彙の約1/3がフランス語あるいはその親言語であるラテン語からの借用語である.関連するいくつかの統計については,「#110. 現代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-15-1]) および,「#1645. 現代日本語の語種分布」 ([2013-10-28-1]) の冒頭に張ったリンクを参照されたい.

この事実を初めて聞くと,英語とフランス語に共通する語彙が数多く見られるのは,英単語がフランス語に大量に入り込んだからだと想像する学生が多いようだ.現在の英語の相対的な優位性,また日本語にも多くの英語語彙が流入している事実を考えれば,フランス語が多数の英単語を借用しているはずだという見方が生じるのも無理はない.

しかし,英語史を参照すれば実際には逆であることがわかる.歴史的に英語がフランス単語を大量に借用してきたゆえに,結果として両言語に共通の語彙が多く見られるのである.端的にいえば,1066年のノルマン征服 (norman_conquest) により,イングランドの威信ある言語が英語からフランス語へ移った後に,高位のフランス語から低位の英語へと語彙が大量に流れ込んだということである.(英語がフランス語に与えた影響という逆方向の事例は,歴史的には相対的に稀である.「#1026. 18世紀,英語からフランス語へ入った借用語」 ([2012-02-17-1]),「#1012. 古代における英語からフランス語への影響」 ([2012-02-03-1]) を参照.)

現代フランス語を少しでもかじったことのある者であれば,英仏語で共通する語は確かに多いけれど,形や意味が互いにずれているという例が少なくないことに気づくだろう.対応する語彙はあるのだが,厳密に「同じ」であるわけではない.これにより,false_friend (Fr. "faux amis") の問題が生じることになる (cf. 「#390. Cosmopolitan Vocabulary は Asset か? (2)」 ([2010-05-22-1])) .フランス語側の model と英語側の loan との間に,形や意味のずれが生じてしまうのは,いったいなぜだろうか(model と loan という用語については,「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]) を参照).

この問いに答えるには,(1) 語彙の借用過程 (borrowing) に起こりがちな現象,(2) フランス語彙の借用の時期とその後の言語変化,(3) 借用の対象となったフランス語の方言,という3点について理解しておく必要がある.今回は,(1) に注目しよう.語彙の借用過程に起こりがちな現象とは,借用元言語における語の形や意味が,多少なりとも歪められて借用先言語へコピーされるのが普通であることだ.まず形に注目すれば,借用語は,もとの発音や綴字を,多かれ少なかれ借用先言語の体系に適合させて流入するのが通常である.例えば,フランス語の円心前舌高母音 /y/ や硬口蓋鼻音 /ɲ/ は,必ずしもそのままの形で英語に取り入れられたのではなく,多くの場合それぞれ /ɪʊ/, /nj/ として取り込まれた (cf. 「#1222. フランス語が英語の音素に与えた小さな影響」 ([2012-08-31-1]),「#1727. /ju:/ の起源」 ([2014-01-18-1])) .微妙な差異ではあるが,語の借用において model がそのまま綺麗にコピーされるわけではないことを示している.英語の /ʃəːt/ (shirt) が日本語の /shatsu/ (シャツ)として取り込まれる例など,話し言葉から入ったとおぼしきケースでは,このようなズレが生じるのは極めて普通である.

次に意味に注目しても,model と loan の間にはしばしばギャップが観察される.とりわけ借用においては model の語義の一部のみが採用されることが多く,意味の範囲としては model > loan の関係が成り立つことが多い.有名な動物と肉の例を挙げると,英語 beef は古フランス語 boef, buefから借用した語である.model には牛と牛肉の両方の語義が含まれるが,loan には牛肉の語義しか含まれない.ここではフランス単語が,意味を縮小した形で英語へ借用されている(ただし,「#331. 動物とその肉を表す英単語」 ([2010-03-24-1]),「#332. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」の神話」 ([2010-03-25-1]) も参照).同様に,英語 room は「ルーム」として部屋の語義において日本語に入っているが,余地の語義は「ルーム」にはない.

上で挙げてきた諸例では,英単語とフランス単語の間の差異はあったとしても比較的小さいものだった.しかし,フランス語学習において出会う単語の英仏語間のズレと違和感は,しばしばもっと大きい.この謎を探るには,(2) と (3) の視点が是非とも必要である.これについては,明日の記事で.

2015-04-01 Wed

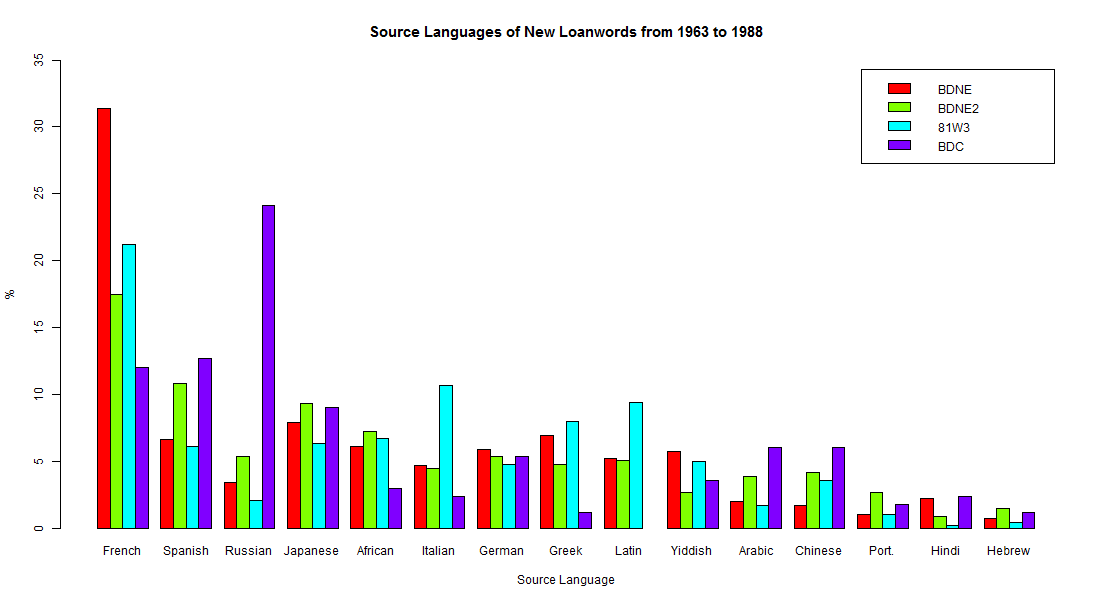

■ #2165. 20世紀後半の借用語ソース [loan_word][statistics][lexicology][french][japanese][borrowing]

現代英語の新語の導入においては,複合 (compounding) や派生 (derivation) が主たる方法となってきており,借用 (borrowing) の貢献度は相対的に低い.ここ1世紀ほどの推移をみても,借用の割合は全体的に目減りしている (cf. 「#873. 現代英語の新語における複合と派生のバランス」 ([2011-09-17-1]) や「#874. 現代英語の新語におけるソース言語の分布」 ([2011-09-18-1]),「#875. Bauer による現代英語の新語のソースのまとめ」 ([2011-09-19-1]),「#878. Algeo と Bauer の新語ソース調査の比較」([2011-09-22-1]),「#879. Algeo の新語ソース調査から示唆される通時的傾向」([2011-09-23-1])) .

だが,相対的に減ってきているとはいえ,語彙借用は現代英語でも続いている.#874 と Algeo の詳細な区分のなかでも示されているように,ソース言語は相変わらず多様である.「#45. 英語語彙にまつわる数値」 ([2009-06-12-1]),「#126. 7言語による英語への影響の比較」 ([2009-08-31-1]),「#142. 英語に借用された日本語の分布」 ([2009-09-16-1]) では,現代英語への語彙提供者として案外日本語が有力であることに触れたが,日本語なども含めたソース言語別のより詳しい割合が知りたいところだ.

Algeo (78) は,Garland Cannon (Historical Change and English Word-Formation. New York: Peter Lang, 1987. pp. 69--97) の調査に基づいて,20世紀後半に入ってきた借用語彙のソース言語別割合を提示している.具体的には,およそ1963--88年の間に英語に入ってきた借用語を記録する4つの辞書を調査対象とし,ソース言語別に借用語を数え上げ,それぞれの割合を出した.その4つの辞書とは,(1) The Barnhart Dictionary of New English since 1963 (1973), (2) The Second Barnhart Dictionary of New English (1980), (3) Webster's Third (1961), (4) The Barnhart Dictionary Companion Index (1987) である.それぞれから407語, 332語, 523語, 166語を集めた1428語の小さい語彙集合ではあるが,それに基づいて以下の調査結果が得られた.

| (1) BDNE | (2) BENE2 | (3) 81W3 | (4) BDC | Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French | 31.4% | 17.5 | 21.2 | 12.0 | 1 |

| Spanish | 6.6 | 10.8 | 6.1 | 12.7 | 2 |

| Russian | 3.4 | 5.4 | 2.1 | 24.1 | 3 |

| Japanese | 7.9 | 9.3 | 6.3 | 9.0 | 4 |

| African | 6.1 | 7.2 | 6.7 | 3.0 | 5 |

| Italian | 4.7 | 4.5 | 10.7 | 2.4 | 6 |

| German | 5.9 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 5.4 | 7 |

| Greek | 6.9 | 4.8 | 8.0 | 1.2 | 8 |

| Latin | 5.2 | 5.1 | 9.4 | 9 | |

| Yiddish | 5.7 | 2.7 | 5.0 | 3.6 | 10 |

| Arabic | 2.0 | 3.9 | 1.7 | 6.0 | 11 |

| Chinese | 1.7 | 4.2 | 3.6 | 6.0 | 12 |

| Portuguese | 1.0 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 13 |

| Hindi | 2.2 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 14 |

| Hebrew | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 15 |

| Sanskrit | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 16 | |

| Persian | 0.2 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 17 | |

| Afrikaans | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 18 | |

| Dutch | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 19 | |

| Indonesian | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 20 |

| Malayo-Polynesian | 2.1 | 0.2 | 21 | ||

| Norwegian | 0.2 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 22 | |

| Swedish | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 23 | |

| Korean | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 24 | |

| Vietnamese | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 25 | |

| Amerindian | 1.2 | 0.6 | 26 | ||

| Bengali | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 27 | |

| Danish | 0.5 | 1.0 | 28 | ||

| Eskimo | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 29 |

表に記されていない30--56位の言語群は合わせても全体として1%にも満たないが,念のために次のような言語である.Amharic, Annamese, Basque, Bhutanese, Catalan, Czech, Hawaiian, Hungarian, Irish, Khmer, Mongolian, Papuan, Pashto, Pidgin English, Pilipino, Polish, Provençal, Punjabi, Samoan, Scots (Gaelic), Serbo-Croatian, Tahitian, Thai (and Lao), Turkish, Urdu, Welsh, West Indian.

BDC でロシア語が妙に高い割合を示しているが,これは編集上の偏りに起因する可能性がある.偏りの可能性を差し引いて考えると,ロシア語は順位としてはアラビア語と中国語の間の12位前後に付くと思われる.

15位までの言語についてグラフ化したのが,下図である.

このグラフは,「#874. 現代英語の新語におけるソース言語の分布」 ([2011-09-18-1]) でみた Bauer の調査に基づくグラフの場合とソース言語の設定の仕方が異なるので,比較しにくいところがあるが,フランス語,ギリシア語,ラテン語,ドイツ語などが上位で健闘している様子はいずれのグラフからも見て取ることができる.スペイン語やイタリア語などのロマンス諸語も堅調といってよい.そのなかで,非印欧語として筆頭に立っているのが日本語である.アフリカ諸語,アラビア語,中国語も続いており,英語の cosmopolitan vocabulary 振りは現代においても健在といえるだろう.

・ Algeo, John. "Vocabulary." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 4. Cambridge: CUP, 1998. 57--91.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow