2024-06-18 Tue

■ #5531. Chancery English とは何か? [chancery_standard][standardisation][lme][spelling][orthography][signet]

現代標準英語の歴史的基盤はどこにあるか.この問題は英語史でも第一級の重要課題である.正書法に関する限り,それは中英語後期の Chancer English に求められる,とするのが Samuels (1963) 以来の有力な説である,これについては「#306. Samuels の中英語後期に発達した書きことば標準の4タイプ」 ([2010-02-27-1]),「#1228. 英語史における標準英語の発展と確立を巡って」 ([2012-09-06-1]))や「#3214. 1410年代から30年代にかけての Chancery English の萌芽」 ([2018-02-13-1]) をはじめとする chancery_standard の記事を参照されたい.

この Chancery とは「大法官庁」のことで,いわゆる国家の官僚組織を指す.では,その名前にあやかって後に Chancer English や Chancery Standard と呼ばれることになった英語変種とは,具体的には何のことなのだろうか.Fisher et al. (xii) より,当面の定義を与えておこう.

We follow M. L. Samuels, in calling the official written English of the first half of the 15th century "Chancery English" although it emanated from at least four offices, Signet, Privy Seal, Parliament, and the emerging Court of Chancery itself. The generalized term is valid in an historical sense. By the end of the 15th century the term "Chancery" had come to be restricted to the royal courts of law, but until the departmentalization of the national bureaucracy into various offices, which began in the reign of Henry VII, Chancery comprised virtually all of the national bureaucracy except for the closely allied Exchequer. Thomas Frederick Tout, who made a life-time study of the workings of Chancery and its affiliated offices, begins his Chapters in The Administrative History of Mediaeval England by quoting Palgrave's observation that "Chancery was the Secretariat of State in all departments of late medieval government."

Chancery とは,玉璽局 (Signet),王璽尚書局 (Privy Seal),議会 (Parliament),大法官裁判所 (Court of Chancery) を中心とし, 王室会計局 (Exchequer) を除いたほぼすべての国家事務局を指したということだ.そこで用いられた比較的一様な綴字によって表わされる英語変種が,Chancery English ということになる.完全な定義ではないとはいえ,当面はこの理解で十分だろう.

・ Samuels, Michael Louis. "Some Applications of Middle English Dialectology." English Studies 44 (1963): 81--94. Revised in Middle English Dialectology: Essays on Some Principles and Problems. Ed. Margaret Laing. Aberdeen: Aberdeen UP, 1989.

・ Fisher, John H., Malcolm Richardson, and Jane L. Fisher, comps. An Anthology of Chancery English. Knoxville: U of Tennessee P, 1984. 392.

2023-08-27 Sun

■ #5235. 片見彰夫先生と15世紀の英文法について対談しました [voicy][heldio][review][corpus][lme][syntax][phrasal_verb][subjunctive][complementation][caxton][malory][negative][impersonal_verb][preposition][periodisation]

6月に開拓社より出版された『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』について,すでに何度かご紹介してきました.6名の研究者の各々が,15--20世紀の各世紀の英文法およびその変化について執筆するというユニークな構成の本です.

本書の第1章「15世紀の文法的・構文的変化」の執筆を担当された片見彰夫先生(青山学院大学)と,Voicy heldio での対談が実現しました.えっ,15世紀というのは伝統的な英語史の時代区分では中英語期の最後の世紀に当たるのでは,と思った方は鋭いです.確かにその通りなのですが,対談を聴いていただければ,15世紀を近代英語の枠組みで捉えることが必ずしも無理なことではないと分かるはずです.まずは「#817. 『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』 --- 片見彰夫先生との対談」をお聴きください(40分超の音声配信です).

私自身も,片見先生と対談するまでは,15世紀の英語はあくまで Chaucer に代表される14世紀の英語の続きにすぎないという程度の認識でいたところがあったのですが,思い違いだったようです.近代英語期への入り口として,英語史上,ユニークで重要な時期であることが分かってきました.皆さんも15世紀の英語に関心を寄せてみませんか.最初に手に取るべきは,対談の最後にもあったように,Thomas Malory による Le Morte Darthur 『アーサー王の死』ですね(Arthur 王伝説の集大成).

時代区分の話題については,本ブログでも periodisation のタグのついた多くの記事で取り上げていますので,ぜひお読み下さい.

さて,今回ご案内した『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』については,これまで YouTube 「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」,hellog, heldio などの各メディアで紹介してきました.以下よりご参照ください.

・ YouTube 「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」より「#137. 辞書も規範文法も18世紀の産業革命富豪が背景に---故山本史歩子さん(英語・英語史研究者)に捧ぐ---」

・ hellog 「#5166. 秋元実治(編)『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』(開拓社,2023年)」 ([2023-06-19-1])

・ hellog 「#5167. なぜ18世紀に規範文法が流行ったのですか?」 ([2023-06-20-1])

・ hellog 「#5182. 大補文推移の反対?」 ([2023-07-05-1])

・ hellog 「#5186. Voicy heldio に秋元実治先生が登場 --- 新刊『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』についてお話しをうかがいました」 ([2023-07-09-1])

・ hellog 「#5208. 田辺春美先生と17世紀の英文法について対談しました」 ([2023-07-31-1])

・ hellog 「#5224. 中山匡美先生と19世紀の英文法について対談しました」 ([2023-08-16-1])

・ heldio 「#769. 『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』 --- 秋元実治先生との対談」

・ heldio 「#772. 『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』 --- 16世紀の英語をめぐる福元広二先生との対談」

・ heldio 「#790. 『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』 --- 田辺春美先生との対談」

・ heldio 「#806. 『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』 --- 中山匡美先生との対談」

・ heldio 「#817. 『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』 --- 片見彰夫先生との対談」

・ 秋元 実治(編),片見 彰夫・福元 広二・田辺 春美・山本 史歩子・中山 匡美・川端 朋広・秋元 実治(著) 『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』 開拓社,2023年.

2023-01-16 Mon

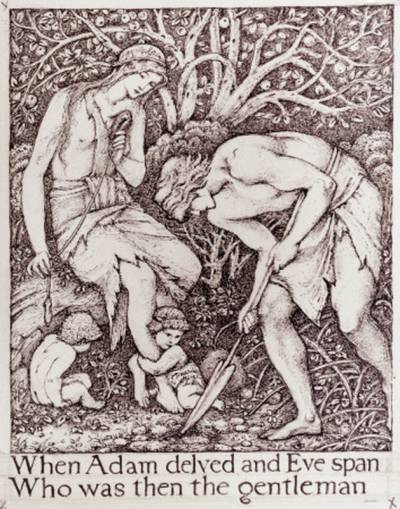

■ #5012. When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman? --- John Ball の扇動から生まれた諺 [proverb][black_death][lme][morris][hundred_years_war]

標題の諺は「アダムが耕しイヴが紡いだとき,だれがジェントルマンであったのか」を意味する.14世紀後半のイングランドでは,英仏百年戦争 (hundred_years_war) と黒死病 (black_death) により人々が窮乏生活にあえいでいた.そんな中,1381年に農民一揆 (Peasants' Revolt) が勃発した.この一揆は,すぐに Richard II により鎮圧されたが,英語の復権にあずかって力があった事件として英語史上にも名を残している.

この農民一揆の指導者の1人が John Ball (d. 1381) である(もう1人が Wat Tyler (d. 1381)).Ball は聖職者だったが,階級社会を批判する説教をしたとして破門されていた.彼はロンドンの Blackheath で標題の文句を唱え,群衆を扇動して一揆へ駆り立てたとされる.後に Ball は審問され絞首刑となった.その後500年の時が流れ,19世紀後半の詩人・工芸美術家の William Morris (1834--96) が,社会主義の主張を込めて小説 A Dream of John Ball (1888) を著わし,Ball を有名にした.諺としては,後期中英語から近代英語にかけて知られていたようである.

delve は現代英語では「掘り下げる,徹底的に調べる」を意味し,This biography delves deep into the artist's private life. や If you're interested in a subject, use the Internet to delve deeper. のように用いる.しかし,古英語の語源形 delfan は文字通り「掘る;耕す」の意味で,現代の比喩的な語義が発達したのは17世紀半ばのことである.

農民一揆という歴史的事件から生まれた諺として記憶しておきたい.

・ Speake, Jennifer, ed. The Oxford Dictionary of Proverbs. 6th ed. Oxford: OUP, 2015.

2023-01-10 Tue

■ #5006. YouTube 版,515通りの through の話し [spelling][me_dialect][lme][scribe][youtube][standardisation][oed][med][laeme][lalme][hc][through]

昨年2月26日に,同僚の井上逸兵さんと YouTube チャンネル「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」を開始しました.以降,毎週レギュラーで水・日の午後6時に配信しています.最新動画は,一昨日公開された第91弾の「ゆる~い中世の英語の世界では綴りはマイルール?!through のスペリングは515通り!堀田的ゆるさベスト10!」です.

英語史上,前置詞・副詞の through はどのように綴られてきたのでしょうか? 後期中英語期(1300--1500年)を中心に私が調査して数え上げた結果,515通りの異なる綴字が確認されています.OED や MED のような歴史英語辞書,Helsinki Corpus, LAEME, LALME のような歴史英語コーパスや歴史英語方言地図など,ありとあらゆるリソースを漁ってみた結果です.探せばもっとあるだろうと思います.

標準英語が不在だった中英語期には,写字生 (scribe) と呼ばれる書き手は,自らの方言発音に従って,自らの書き方の癖に応じて,様々な綴字で単語を書き落としました.同一写字生が,同じ単語を異なる機会に異なる綴字で綴ることも日常茶飯事でした.とりわけ through という語は方言によって発音も様々だったため,子音字や母音字の組み合わせ方が豊富で,515通りという途方もない種類の綴字が生じてしまったのです.

関連する話題は hellog でもしばしば取り上げてきました.以下をご参照ください.

・ 「#53. 後期中英語期の through の綴りは515通り」 ([2009-06-20-1])

・ 「#54. through 異綴りベスト10(ワースト10?)」 ([2009-06-21-1])

・ 「#3397. 後期中英語期の through のワースト綴字」 ([2018-08-15-1])

・ 「#193. 15世紀 Chancery Standard の through の異綴りは14通り」 ([2009-11-06-1])

・ 「#219. eyes を表す172通りの綴字」 ([2009-12-02-1])

・ 「#2520. 後期中英語の134種類の "such" の異綴字」 ([2016-03-21-1])

・ 「#1720. Shakespeare の綴り方」 ([2014-01-11-1])

今回,515通りの through の話題を YouTube でお届けした次第ですが,その収録に当たって「小道具」を用意しました.せっかくですので,以下に PDF で公開しておきます.

・ 横置きA4用紙10枚に515通りの through の綴字を敷き詰めた資料 (PDF)

・ 横置きA4用紙1枚に1通りの through の綴字を大きく印字した全515ページの資料 (PDF)

・ 堀田の選ぶ「ベスト(ワースト)10」の through の綴字を印字した10ページの資料 (PDF)

ユルユル綴字の話題と関連して,同じ YouTube チャンネルより比較的最近アップされた第83弾「ロバート・コードリー(Robert Cawdrey)の英英辞書はゆるい辞書」もご覧いただければと(cf. 「#4978. 脱力系辞書のススメ --- Cawdrey さんによる英語史上初の英英辞書はアルファベット順がユルユルでした」 ([2022-12-13-1])).

2022-10-05 Wed

■ #4909. eWAVE は LAEME/LALME の現代世界英語版だった! [ewave][laeme][lalme][pde][eme][lme][world_englishes]

「#4902. eWAVE 3.0 の紹介 --- 世界英語の言語的特徴を格納したデータベース」 ([2022-09-28-1]) で,世界77変種の英語の統語形態情報を集積したデータベース eWAVE 3.0 (= The Electronic World Atlas of Varieties of English) を紹介した.言語項目に関する分布を世界地図上にプロットしてくれる優れものだが,どこか既視感のようなものを感じていた.

そして思い当たった.これは初期・後期中英語のイングランド方言地図 LAEME と LALME の現代世界英語版ではないかと.逆にいえば,LAEME/LALME は eWAVE の中英語版とみることができる.このことに気づいた瞬間,eWAVE と LAEME/LALME の英語史上の位置づけと意義が理解できた.

eWAVE と LAEME/LALME は対象とする時代や地理的な規模こそ異なっているが,狙いとしては類似している点が多い.いずれも当該時代の英語の特定の言語項目について,地域変種ごとにプロファイルをまとめてくれ,さらに地図上に分布をプロットしてくれる.そして,出力された結果を正しく解釈するためには高度な英語学・英語史の知識が必要であるという点も似ている.「標準変種」の概念が不在,あるいは少なくとも強く意識されていない,というのも共通点だ.

ただし,そもそも連携が意識されたプロジェクトではないわけで,当然ながら異なる点も多々ある.

・ eWAVE のターゲットは現代の世界英語というグローバルな規模,LAEME/LALME のターゲットは初期・後期中英語イングランドというローカルな規模

・ eWAVE のインフォーマントは各変種に精通した現代に生きる言語の専門家,LAEME/LALME のインフォーマントはたまたま現存している写本資料(eWAVE には "fit-technique" のような理論的な手法は不要)

・ eWAVE は統語形態項目に特化したプロファイルを,LAEME/LALME は音韻形態・綴字項目に特化したプロファイルを提供している

・ eWAVE のエンジンはデータベース,LAEME(体系的ではないが LALME も)のエンジンはコーパス(GloWbE のような世界英語コーパスは存在するが,eWAVE とは独立しているため,LAEME のように方言地図とコーパスとのシームレスな連携は望めない)

おもしろいのは,時代的に eWAVE と LAEME/LALME の間に位置する近代英語期について,類似の方言地図が作られていないことだ.近代英語期から現存する言語資料の大半が標準変種で書かれており,各地域変種の様子が見えてこないために,データベースもコーパスも編纂できないからだろう.地域変種の現われ方という観点からすると,時代を隔てた中英語と現代英語のほうがむしろ似ているのである.

2018-08-16 Thu

■ #3398. 中英語期の such のワースト綴字 [spelling][eme][lme][me_dialect][levenshtein_distance]

昨日の記事「#3397. 後期中英語期の through のワースト綴字」 ([2018-08-15-1]) に引き続き,今回は such の異綴字について.「#2520. 後期中英語の134種類の "such" の異綴字」 ([2016-03-21-1]),「#2521. 初期中英語の113種類の "such" の異綴字」 ([2016-03-22-1]) で見たように,私の調べた限り,中英語全体では such を表記する異綴字が212種類ほど確認される.そのうちの208種について,昨日と同じ方法で現代標準綴字の such にどれだけ類似しているかを計算し,似ている順に列挙してみた.

| Similarity | Spellings |

|---|---|

| 1.0000 | such |

| 0.8889 | sƿuch, shuch, succh, suche, sucht, suech, suich, sulch, suuch, suych, swuch |

| 0.8571 | suc |

| 0.8000 | sƿucch, sƿuche, schuch, scuche, shuche, souche, sucche, suchee, suchet, suchte, sueche, suiche, suilch, sulche, sutche, suuche, suuech, suyche, swuche, swulch |

| 0.7500 | sƿuc, scht, sech, shuc, sich, soch, sueh, suhc, suhe, suic, sulc, suth, suyc, swch, swuh, sych |

| 0.7273 | sƿucche, sƿuchne, sƿulche, schuche, suecche, suueche, suweche |

| 0.6667 | hsƿucche, sƿche, sƿich, sƿucches, sƿulc, schch, schuc, schut, seche, shich, shoch, shych, siche, soche, suicchne, suilc, svche, svich, swche, swech, swich, swlch, swulchen, swych, syche, zuich, zuych |

| 0.6154 | swulchere |

| 0.6000 | asoche, sƿiche, sƿilch, sƿlche, sƿuilc, sƿulce, schech, schute, scoche, scwche, secche, shiche, shoche, sowche, soyche, sqwych, suilce, sviche, sweche, swhych, swiche, swlche, swyche, zuiche, zuyche |

| 0.5714 | sec, sic, sug, swc, syc |

| 0.5455 | aswyche, sƿicche, sƿichne, sƿilche, sƿi~lch, scheche, schiche, schilke, schoche, sewyche, sqwyche, sswiche, swecche, swhiche, swhyche, swichee, swyeche, zuichen |

| 0.5333 | sucheȝ |

| 0.5000 | sƿic, sɩͨh, scli, secc, sick, silc, slic, solchere, sulk, swic, swlc, swlchere, swulcere |

| 0.4444 | sƿilc, sclik, sclyk, suilk, sulke, suylk, swics, swilc |

| 0.4000 | sƿillc, sclike, sclyke, squike, squilk, squylk, suilke, suwilk, suylke, swilce, swlcne, swulke, swulne |

| 0.3636 | sƿilcne, suilkin, swhilke |

| 0.3333 | swisɩͨhe |

| 0.2857 | sik, sli, slk, sly, syk |

| 0.2500 | selk, sike, silk, slik, slyk, swil, swlk, swyk, swyl, syge, syke, sylk |

| 0.2222 | sƿilk, selke, sliik, slike, slilk, slyke, swelk, swilk, swlke, swyke, swylk, sylke |

| 0.2000 | slieke, slkyke, swilke, swylke, swylle |

| 0.1818 | sƿillke, swilkee, swilkes |

これによると,歴史的なワースト綴字は sƿillke, swilkee, swilkes の3つということになる.確かに・・・.

2018-08-15 Wed

■ #3397. 後期中英語期の through のワースト綴字 [spelling][lme][me_dialect][levenshtein_distance][through]

「#53. 後期中英語期の through の綴りは515通り」 ([2009-06-20-1]),「#54. through 異綴りベスト10(ワースト10?)」 ([2009-06-21-1]) で紹介したように,後期中英語の through の綴字は,著しくヴァリエーションが豊富である.そこではのべ515通りの綴字を集めたが,ハイフン(語の一部であるもの),イタリック体(省略符号などを展開したもの),上付き文字,大文字小文字の違いの有無を無視すれば,444通りとなる.この444通りの綴字について,現代の標準綴字 through にどれだけ近似しているかを,String::Similarity という Perl のモジュールを用いて計算させてみた.類似性の程度を求めるアルゴリズムは,文字変換の工程数 (Levenshtein edit distance) に基づくものである.完全に一致していれば 1.0000 の値を取り,まったく異なると 0.0000 を示す.では,「似ている」順に列挙しよう.

| Similarity | Spellings |

|---|---|

| 1.0000 | through |

| 0.9333 | thorough, throughe, throught |

| 0.9231 | throgh, throug, throuh, thrugh, trough |

| 0.8750 | thoroughe, thorought |

| 0.8571 | thorogh, thorouh, thorugh, thourgh, throȝgh, throghe, throght, throwgh, thrughe, thrught |

| 0.8333 | thogh, throu, thrug, thruh, trogh, trugh |

| 0.8000 | thoroghe, thoroght, thorouȝh, thorowgh, thorughe, thorught, thourghe, thourght, throȝghe, throghet, throghte, throighe, throuȝht, throuche, throwght, thrughte |

| 0.7692 | þrough, thorgh, thorou, thoruh, thourh, throȝh, throch, throuȝ, throue, throwg, throwh, thruch, thruth, thrwgh, thrygh, thurgh, thwrgh, troght, trowgh, trughe, trught |

| 0.7500 | thorowghe, thorowght |

| 0.7273 | thro |

| 0.7143 | þorough, þrought, thorȝoh, thorghe, thorght, thorghw, thorgth, thorohe, thorouȝ, thorowg, thorowh, thorrou, thoruȝh, thoruth, thorwgh, thourhe, thourth, thourwg, thowrgh, throȝhe, throcht, throuȝe, throwth, thruȝhe, thrwght, thurgeh, thurghe, thurght, thurgth, thurhgh, trowght, yorough |

| 0.6667 | þorought, þough, þrogh, þroughte, þrouh, þrugh, thorg, thorghwe, thorh, thoro, thorowth, thorowut, thoru, thour, throȝ, throw, thruȝ, thrue, thuht, thurg, thurghte, thurh, thuro, thuru, torgh, yrogh, yrugh |

| 0.6154 | þorogh, þorouh, þorugh, þourgh, þroȝgh, þroghe, þrouȝh, þrouhe, þrouht, þrowgh, þurugh, thorȝh, thorch, thoroo, thorow, thorth, thoruȝ, thorue, thorur, thorwh, thourȝ, thoure, thourr, thourw, thowur, throȝe, throȝt, throve, throwȝ, throwe, throwr, thruȝe, thrvoo, thurȝh, thurch, thurge, thurhe, thurow, thurth, torghe, trghug, yhurgh, yorugh, yourgh |

| 0.5714 | þoroghe, þorouȝh, þorowgh, þorught, þourght, þrouȝth, þrowghe, þurughe, thorowȝ, thorowe, thorrow, thorthe, thourȝe, thourow, thowrow, thrawth, throwȝe, thurȝhg, thurȝth, thurgwe, thurhge, thurowe, thurthe, yhurght, yourghe |

| 0.5455 | þrou, þruh, thow, thrw, thur, trow, yrou |

| 0.5333 | þorowghe, þorrughe, thorowȝt |

| 0.5000 | þorgh, þorou, þorug, þoruh, þourg, þourh, þroȝh, þroth, þrouȝ, þrowh, þurgh, þwrgh, ȝorgh, thorȝ, thorv, thorw, thowe, thowr, threw, thrwe, thurȝ, thurv, thurw, thwrw, trowe, yhorh, yhoru, yhrow, yorgh, yorou, yoruh, yourh, yurgh |

| 0.4615 | þhorow, þorghȝ, þorghe, þorght, þorguh, þorouȝ, þoroue, þorour, þorowh, þoruȝh, þorugȝ, þoruhg, þoruth, þorwgh, þourȝh, þourgȝ, þourth, þroȝth, þrouȝe, þrouȝt, þurgȝh, þurghȝ, þurghe, þurght, þuruch, dorwgh, dourȝh, drowgȝ, durghe, tþourȝ, thorȝe, thorȝt, thorȝw, thorew, thorwȝ, thorwe, thurȝe, thurȝt, thurew, thurwe, yorghe, yoroue, yorour, yourch, yurghe, yurght |

| 0.4286 | þorouȝe, þorouȝt, þorouwȝ, þorowth, þrouȝte, thorȝwe, thorewe, thorffe, thorwȝe, thowffe, trowffe |

| 0.4000 | þro |

| 0.3636 | ðoru, þorg, þorh, þoro, þoru, þouȝ, þour, þroȝ, þrow, þruȝ, þurg, þurh, þuro, þuru, ȝoru, ȝour, torw, twrw, yorh, yoro, yoru, your, yrow, yruȝ, yurg, yurh, yuru |

| 0.3333 | þerow, þerue, þhurȝ, þorȝh, þorch, þoreu, þorgȝ, þoroȝ, þorow, þorth, þoruþ, þoruȝ, þorue, þorwh, þouȝt, þourþ, þourȝ, þourt, þourw, þroȝe, þroȝt, þrowþ, þrowȝ, þrowe, þruȝe, þurȝg, þurȝh, þurch, þureh, þurhg, þurht, þurow, þurru, þurth, þuruȝ, þurut, ȝoruȝ, ȝurch, doruȝ, torwe, yoȝou, yorch, yorow, yoruȝ, yourȝ, yourw, yurch, yurhg, yurht, yurth, yurwh |

| 0.3077 | þorȝhȝ, þorowþ, þorowe, þorrow, þoruȝe, þoruȝt, þorwgȝ, þorwhe, þorwth, þourȝe, þourȝt, þourȝw, þourow, þouruȝ, þourwe, þrorow, þrowȝe, þurȝhg, þurȝth, þurthe, ȝoruȝt, yerowe, yorowe, yurowe, yurthe |

| 0.2857 | þrorowe |

| 0.2000 | þor, þur |

| 0.1818 | þarȝ, þorþ, þorȝ, þore, þorv, þorw, þowr, þurþ, þurȝ, þurf, þurw, ȝorw, ȝowr, dorw, yorȝ, yora, yorw, yowr, yurȝ, yurw |

| 0.1667 | þerew, þorȝe, þorȝt, þoreȝ, þorew, þorwȝ, þorwe, þowre, þurȝe, þurȝt, þureȝ, þurwȝ, þurwe, dorwe, durwe, yorwe, yowrw, yurȝe |

| 0.1538 | þorewȝ, þorewe, þorwȝe, þorwtȝ |

これによると,最も through とは似ていない,とんでもない綴字は,þorewȝ, þorewe, þorwȝe, þorwtȝ の4種類ということになる.そんなに似ていないかなあと思ってしまうのは,中英語のとんでもない綴字に見慣れてしまったせいだろうか・・・.ちなみに,現在アメリカ英語で省略綴字として用いられる thru は,後期中英語には,ありそうでなかったようだ.

2018-04-02 Mon

■ #3262. 後期中英語の標準化における "intensive elaboration" [lme][standardisation][latin][french][register][terminology][lexicology][loan_word][lexical_stratification]

「#2742. Haugen の言語標準化の4段階」 ([2016-10-29-1]) や「#2745. Haugen の言語標準化の4段階 (2)」 ([2016-11-01-1]) で紹介した Haugen の言語標準化 (standardisation) のモデルでは,形式 (form) と機能 (function) の対置において標準化がとらえられている.それによると,標準化とは "maximal variation in function" かつ "minimal variation in form" に特徴づけられる現象である.前者は codification (of form),後者は elaboration (of function) に対応すると考えられる.

しかし,"elaboration" という用語は注意が必要である.Haugen が標準化の議論で意図しているのは,様々な使用域 (register) で広く用いることができるという意味での "elaboration of function" のことだが,一方 "elaboration of form" という別の過程も,後期中英語における標準化と深く関連するからだ.混乱を避けるために,Haugen が使った意味での "elaboration of function" を "extensive elaboration" と呼び,"elaboration of form" のほうを "intensive elaboration" と呼んでもいいだろう (Schaefer 209) .

では,"intensive elaboration" あるいは "elaboration of form" とは何を指すのか.Schaefer (209) によれば,この過程においては "the range of the native linguistic inventory is increased by new forms adding further 'variability and expressiveness'" だという.中英語の後半までは,書き言葉の標準語といえば,英語の何らかの方言ではなく,むしろラテン語やフランス語という外国語だった.後期にかけて英語が復権してくると,英語がそれらの外国語に代わって標準語の地位に就くことになったが,その際に先輩標準語たるラテン語やフランス語から大量の語彙を受け継いだ.英語は本来語彙も多く保ったままに,そこに上乗せして,フランス語の語彙とラテン語の語彙を取り入れ,全体として序列をなす三層構造の語彙を獲得するに至った(この事情については,「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]) や「#2977. 連載第6回「なぜ英語語彙に3層構造があるのか? --- ルネサンス期のラテン語かぶれとインク壺語論争」」 ([2017-06-21-1]) の記事を参照).借用語彙が大量に入り込み,書き言葉上,英語の語彙が序列化され再編成されたとなれば,これは言語標準化を特徴づける "minimal variation in form" というよりは,むしろ "maximal variation in form" へ向かっているような印象すら与える.この種の variation あるいは variability の増加を指して,"intensive elaboration" あるいは "elaboration of form" と呼ぶのである.

つまり,言語標準化には形式上の変異が小さくなる側面もあれば,異なる次元で,形式上の変異が大きくなる側面もありうるということである.この一見矛盾するような標準化のあり方を,Schaefer (220) は次のようにまとめている.

While such standardizing developments reduced variation, the extensive elaboration to achieve a "maximal variation in function" demanded increased variation, or rather variability. This type of standardization, and hence norm-compliance, aimed at the discourse-traditional norms already available in the literary languages French and Latin. Late Middle English was thus re-established in writing with the help of both Latin and French norms rather than merely substituting for these literary languages.

・ Schaefer Ursula. "Standardization." Chapter 11 of The History of English. Vol. 3. Ed. Laurel J. Brinton and Alexander Bergs. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2017. 205--23.

2017-01-08 Sun

■ #2813. Bokenham の純粋主義 [purism][french][latin][lme][reestablishment_of_english]

「#2147. 中英語期のフランス借用語批判」 ([2015-03-14-1]) で触れたように,Polychronicon を15世紀に英訳した Osbern Bokenham (1393?--1447?) という人物がいる.ノルマン征服以来,英語がフランス語やその他の言語と混合して崩れた言語になってしまったこと,英語話者がろくでもない英語を使うようになってしまったことを嘆いた純粋主義 (purism) の徒である.Bokenham の批判の直接の対象は,フランス語やラテン語にかぶれたイングランド社会の風潮であり,結果として人々がどの言語を用いるにせよ野蛮な言葉遣いしかできなくなっている現状だった.Bokenham のぼやきを,Gramley (110) からの引用で示そう.

And þis corrupcioun of Englysshe men yn þer modre-tounge, begunne as I seyde with famylyar commixtion of Danys firste and of Normannys aftir, toke grete augmentacioun and encrees aftir þe commyng of William conquerour by two thyngis. The firste was: by decre and ordynaunce of þe seide William conqueror children in gramer-scolis ageyns þe consuetude and þe custom of all oþer nacyons, here owne modre-tonge lafte and forsakyn, lernyd here Donet on Frenssh and to construyn yn Frenssh and to maken here Latyns on þe same wyse. The secounde cause was þat by the same decre lordis sonys and all nobyll and worthy mennys children were fyrste set to lyrnyn and speken Frensshe, or þan þey cowde spekyn Ynglyssh and þat all wrytyngis and endentyngis and all maner plees and contravercyes in courtis of þe lawe, and all maner reknyngnis and countis yn howsoolde schulle be doon yn the same. And þis seeyinge, þe rurales, þat þey myghte semyn þe more worschipfull and honorable and þe redliere comyn to þe famyliarite of þe worthy and þe grete, leftyn hure modre tounge and labouryd to kunne spekyn Frenssh: and thus by processe of tyme barbariȝid thei in bothyn and spokyn neythyr good Frenssh nor good Englyssh.

実際には15世紀にはイングランド人のフランス語やラテン語の能力はぐんと落ちていたはずであり,どの階層の人々も日常的に英語を用いる時代になって久しかったのだから,これらの外国語を母語たる英語に対する本格的な脅威として見ていたわけではないだろう(関連して「#2612. 14世紀にフランス語ではなく英語で書こうとしたわけ」 ([2016-06-21-1]),「#2622. 15世紀にイングランド人がフランス語を学んだ理由」 ([2016-07-01-1]) を参照).だが,これらの言語からの借用語などの「遺産」は英語において累々と積み重ねられており,それが Bokenham の言語的純粋主義を刺激していたものと思われる.むしろ英語の復権が事実上達成された後の時代における不満,あるいはいまだフランス語やラテン語にかぶれている貴族階級を中心とするイングランド人への非難,というように聞こえる.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

2017-01-07 Sat

■ #2812. バラ戦争の英語史上の意義 [history][standardisation][lme][monarch][sociolinguistics]

イングランド史において中世の終焉を告げる1大事件といえば,バラ戦争 (the Wars of the Roses; 1455--85) だろう(この名付けは,後世の Sir Walter Scott (1829) のもの).国内の貴族が,赤バラの紋章をもつ Lancaster 家と白バラの York 家の2派に分かれて,王位継承を争った内乱である.30年にわたる戦いで両派閥ともに力尽き,結局は漁父の利を得るがごとく Lancaster 家の Henry Tudor が Henry VII として王位に就くことになった.この戦いでは貴族が軒並み没落したため,王権は強化されることになり,さらに商人階級が社会的に台頭する契機ともなった.

バラ戦争は,イングランドが中世の封建制から脱皮して近代へと歩みを進めていく過渡期として,政治・経済・社会史上の意義を付されているが,英語史の観点からはどのように評価できるだろうか.Gramley (98--99) は次のように評価している.

. . . the series of wars that go under this name [= The Wars of the Roses] sped up the weakening of feudal power and strengthened the merchant classes since the wars further thinned the ranks of the feudal nobility and facilitated in this way the easier rise of ambitious and able people from the middle ranks of society. When the conflict was settled under Henry VII, a Lancastrian and a Tudor, power was essentially centralized. From the point of view of the language, this meant that the standard which had begun to emerge in the early fourteenth century would continue with a firm base in the usage which had been crystallizing in the London area at least since Henry IV (reign 1399--1413), the first king since the OE period who was a native speaker of English.

この評によると,14世紀の前半に始まっていた英語の標準化 (standardisation) が,バラ戦争の結果として王権が強化され,中産階級が台頭したことにより,15世紀後半以降もロンドンを基盤としていっそう推し進められることになった,という.もとより英語の標準化は非常にゆっくりとしたプロセスであり,引用にあるとおりその開始は "the early fourteenth century" のロンドンにあったと考えることができる(「#1275. 標準英語の発生と社会・経済」 ([2012-10-23-1]) を参照).その後,バラ戦争までの1世紀半の間にも標準化は進んでいたが,あくまで緩慢な過程だった.そのように標準化が穏やかに進んでいたところに,バラ戦争という社会的な大騒動が起こり,標準化を利とみる王権と中産階級が大きな影響力をもつに及んで,その動きが促進された,ということだろう.

その他の歴史的大事件の英語史上の意義については,以下の記事を参照.

・ 「#119. 英語を世界語にしたのはクマネズミか!?」 ([2009-08-24-1])

・ 「#208. 産業革命・農業革命と英語史」 ([2009-11-21-1])

・ 「#254. スペイン無敵艦隊の敗北と英語史」 ([2010-01-06-1])

・ 「#255. 米西戦争と英語史」 ([2010-01-07-1])

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

2016-07-01 Fri

■ #2622. 15世紀にイングランド人がフランス語を学んだ理由 [reestablishment_of_english][french][bilingualism][lme][law_french]

「#2612. 14世紀にフランス語ではなく英語で書こうとしたわけ」 ([2016-06-21-1]) で取り上げたように,後期中英語期にはイングランド人のフランス語使用は減っていった.14世紀から15世紀に入るとその傾向はますます強まり,フランス語は日常的に用いられる身近な言語というよりは,文化と流行を象徴する外国語として認識されるようになっていった.フランス語は,ちょうど現代日本における英語のような位置づけにあったのだ.

15世紀初頭に John Barton がフランス語学習に関する Donet François という論説を書いており,イングランド人がフランス語を学ぶ理由は3つあると指摘している.1つ目は,フランス人と意思疎通できるようになるから,という自然な理由である.なお,イングランド人の間での日常的なコミュニケーションのためにフランス語を学ぶべきだという言及は,どこにもない.後者の用途でのフランス語使用はすでに失われていたと考えてよいだろう.

2つ目は,いまだ法律がおよそフランス語で書かれていたからである.3つ目は,紳士淑女はフランス語で手紙を書き合うのにやぶさかではなかったからである.

2つ目と3つ目の理由は後世には受け継がれなかったが,特に3つ目の理由に色濃く感じられる「フランス語=文化と流行の言語」のイメージそのものは存続した.フランス語のこの方面での威信は,後の18世紀に最高潮に達したが,その余韻は現在も息づいていると言ってよいだろう.フランス借用語彙に宿っているオシャレな含意と相まって,英語(話者)にとってのフランス語のイメージは,中世から大きく変化していないのである.以上,Baugh and Cable (147) を参照した.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-06-21 Tue

■ #2612. 14世紀にフランス語ではなく英語で書こうとしたわけ [reestablishment_of_english][lme][french]

初期近代英語期に書き言葉がラテン語から英語へ切り替わっていった経緯と背景について,昨日の記事「#2611. 17世紀中に書き言葉で英語が躍進し,ラテン語が衰退していった理由」 ([2016-06-20-1]) や「#1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題」 ([2013-03-04-1]),「#2580. 初期近代英語の国語意識の段階」 ([2016-05-20-1]) の記事で話題にした.切り替わりの時期には,まだ英語で書くことへの気後れが感じられたものだが,よく似たような状況が,数世紀遡った14世紀の文学の言語においても見られた.ただし,14世紀の場合に問題となっていたのは,ラテン語からの切り替えというよりは,むしろフランス語からの切り替えである.

この状況を最も直接的に示すのは,14世紀のいくつかのテキストにみられる,英語使用を正当化する旨の言及である.Baugh and Cable (138--40) より,3つのテキストからの引用を挙げよう.1つ目は,1300年頃のイングランド北部方言で書かれた説教からである.

Forthi wil I of my povert

Schau sum thing that Ik haf in hert,

On Ingelis tong that alle may

Understand quat I wil say;

For laued men havis mar mister

Godes word for to her

Than klerkes that thair mirour lokes,

And sees hou thai sal lif on bokes.

And bathe klerk and laued man

Englis understand kan,

That was born in Ingeland,

And lang haves ben thar in wonand,

Bot al men can noht, I-wis,

Understand Latin and Frankis.

Forthi me think almous it isse

To wirke sum god thing on Inglisse,

That mai ken lered and laued bathe.

ここで著者は,イングランドではフランス語やラテン語を理解しない者はいるが,英語を理解しない者はいないと述べて,英語で書くことを正当化している.次に,William of Nassyngton の Speculum Vitae or Mirror of Life (c. 1325) からの1節.

In English tonge I schal ȝow telle,

ȝif ȝe wyth me so longe wil dwelle.

No Latyn wil I speke no waste,

But English, þat men vse mast,

Þat can eche man vnderstande,

Þat is born in Ingelande;

For þat langage is most chewyd,

Os wel among lered os lewyd.

Latyn, as I trowe, can nane

But þo, þat haueth it in scole tane,

And somme can Frensche and no Latyn,

Þat vsed han cowrt and dwellen þerein,

And somme can of Latyn a party,

Þat can of Frensche but febly;

And somme vnderstonde wel Englysch,

Þat can noþer Latyn nor Frankys.

Boþe lered and lewed, olde and ȝonge,

Alle vnderstonden english tonge.

最後に,おそらく14世紀初頭に書かれたロマンス Arthur and Merlin からの1節.

Riȝt is, þat Inglische Inglische vnderstond,

Þat was born in Inglond;

Freynsche vse þis gentilman,

Ac euerich Inglische can.

Mani noble ich haue yseiȝe

Þat no Freynsche couþe seye.

この頃までには,多くの貴族がすでにフランス語能力を失っていたということがわかる.14世紀には,英語は階級を問わずイングランドの皆が理解する言語として認識されていたのである.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-05-13 Fri

■ #2573. Caxton による Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye の序文 [caxton][lme][literature][printing][popular_passage][manuscript][link][me_text]

英語史上最初に英語で印刷された本は,William Caxton による印刷で,Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye (1475) である.印刷された場所はイングランドではなく,Caxton の修行していた Bruges だった.この本は,当時の北ヨーロッパの文化と流行の中心だったブルゴーニュの宮廷においてよく知られていたフランス語の本であり,ヨーク家のイングランド王 Edward IV の妹でブルゴーニュ公 Charles に嫁いでいた Margaret が気に入っていた本でもあったため,Caxton はこれを英訳して出版することを商機と見ていた.

題名の Historyes は,当時は「歴史(物語)」に限定されず「伝説(物語)」をも意味した.Recuyell という英単語は「寄せ集める」を意味する(したがって「編纂文学」ほどを指す)フランス単語を借用したものであり,まさにこの本の題名における使用が初例である.

以下に,英語史上燦然と輝くこの本の序文を,Crystal (32) の版により再現しよう.

hEre begynneth the volume intituled and named the recuyell of the historyes of Troye / composed and drawen out of dyuerce bookes of latyn in to frensshe by the ryght venerable persone and wor-shipfull man . Raoul le ffeure . preest and chapelayn vnto the ryght noble gloryous and myghty prince in his tyme Phelip duc of Bourgoyne of Braband etc In the yere of the Incarnacion of our lord god a thou-sand foure honderd sixty and foure / And translated and drawen out of frenshe in to englisshe by Willyam Caxton mercer of ye cyte of London / at the comaūdemēt of the right hye myghty and vertuouse Pryncesse hys redoubtyd lady. Margarete by the grace of god . Du-chesse of Bourgoyne of Lotryk of Braband etc / Whiche sayd translacion and werke was begonne in Brugis in the Countee of Flaundres the fyrst day of marche the yere of the Incarnacion of our said lord god a thousand foure honderd sixty and eyghte / And ended and fynysshid in the holy cyte of Colen the . xix . day of Septembre the yere of our sayd lord god a thousand foure honderd sixty and enleuen etc.

And on that other side of this leef foloweth the prologe.

なお,Rylands Medieval Collection より The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye の写本画像 を閲覧できる.

・ Crystal, David. Evolving English: One Language, Many Voices. London: The British Library, 2010.

2016-03-21 Mon

■ #2520. 後期中英語の134種類の "such" の異綴字 [spelling][lme][lalme][corpus][scribe][me_dialect][frequency]

「#53. 後期中英語期の through の綴りは515通り」 ([2009-06-20-1]),「#219. eyes を表す172通りの綴字」 ([2009-12-02-1]) に引き続き,英語史における著しい綴字の変異について.今回は,異綴字の種類の多さに定評のある(?) "such" を取り上げる.

「#1622. eLALME」 ([2013-10-05-1]) で紹介した,後期中英語の方言地図 LALME の改訂・電子版 eLALME において,Item List 10 が "such" を扱っている.この一覧から異綴字を抜き出すと,不確かな例を除いて少な目に数えても,以下の134種類が挙がる(かっこ内の数値は文証される頻度).

asoche (1), aswyche (1), schch (1), schech (1), scheche (3), schiche (1), schoche (1), scht (1), schuc (1), schuch (3), schuche (4), schut (1), schute (1), sclik (2), sclike (1), sclyk (2), sclyke (2), scoche (1), scwche (1), sech (8), seche (39), sewyche (2), shich (1), shiche (1), shoch (1), shoche (1), shuch (5), shuche (3), shych (1), sic (6), sic- (1), sich (53), siche (101), sick (1), sɩͨh (1), sik (1), sik- (1), sike (2), silk (3), sli (1), slieke (1), slik (10), slike (26), slilk (2), slkyke (1), slyk (13), slyke (26), soch (12), soche (60), souche (3), sowche (2), soyche (1), squike (1), squilk (2), squylk (1), sqwych (1), sqwyche (1), sswiche (1), suc (1), succh (1), sucche (5), such (242), suche (375), suchee (1), sucheȝ (1), suchet (1), sucht (1), suchte (1), suech (4), sueche (6), suhc (1), suhe (1), suich (9), suiche (7), suilk (6), suilk- (1), suilke (3), suilkin (1), sulc (1), sulk (4), sulke (2), sutche (1), suth (1), suuch (1), suuche (1), suuech (1), suueche (1), suych (13), suyche (15), suylk (7), suylke (6), svche (1), sviche (1), swc (1), swch (7), swche (4), swech (19), sweche (48), swelk (4), swhiche (2), swhilke (2), swhych (2), swhyche (1), swic (2), swich (77), swiche (84), swichee (1), swilc (3), swilk (76), swilke (45), swilkes (1), swisɩͨhe (1), swlk (1), swlke (1), swuch (3), swuche (2), swych (56), swyche (65), swyeche (1), swyk (1), swyke (1), swyl (1), swylk (62), swylke (35), swylle (1), syc- (1), sych (23), syche (67), syge (1), syk (4), syk- (1), syke (5), sylk (3), sylke (2)

方言の別を度外視して頻度の統計を取ると,トップ10が suche, such, siche, swiche, swich, swilk, syche, swyche, swylk, soche である.トップの2種類 suche と such は現代英語を見慣れている者にとって,十分常識的にみえるだろう.実際,この2種類だけで617例が文証され,総1867例のほぼ3分の1を占める.また,トップの10種類だけで,ほぼ3分の2を占める.したがって,異綴字がこれだけ多くあるからといって,そのまま完全なる混沌に等しい,ということにはならない.このような事情は,中英語期に多種類の綴字が認められる多くの語について認められ,混沌のなかにもある程度の秩序らしきものがが宿っているといえる.そうだとしても,当時の書き手と読み手にとってはやはり不便な状況だったに違いない.この点については,「#1311. 綴字の標準化はなぜ必要か」 ([2012-11-28-1]),「#1450. 中英語の綴字の多様性はやはり不便である」 ([2013-04-16-1]) で論じた通りである.

初期中英語や近現代の諸方言形を調べれば,もっと異綴字の種類は増すだろう.出典は失念したが,数え方にもよるものの,500種類ほどという数字を見かけたことがある・・・.

2015-07-20 Mon

■ #2275. 後期中英語の音素体系と The General Prologue [chaucer][pronunciation][phonology][phoneme][phonetics][lme][popular_passage]

Chaucer に代表される後期中英語の音素体系を Cruttenden (65--66) に拠って示したい.音素体系というものは,現代語においてすら理論的に提案されるものであるから,複数の仮説がある.ましてや,音価レベルで詳細が分かっていないことも多い古語の音素体系というものは,なおさら仮説的というべきである.したがって,以下に示すものも,あくまで1つの仮説的な音素体系である.

[ Vowels ]

iː, ɪ uː, ʊ eː oː ɛː, ɛ ɔː, ɔ aː, a ɑː ə in unaccented syllables

[ Diphthongs ]

ɛɪ, aɪ, ɔɪ, ɪʊ, ɛʊ, ɔʊ, ɑʊ

[ Consonants ]

p, b, t, d, k, g, ʧ, ʤ

m, n ([ŋ] before velars)

l, r (tapped or trilled)

f, v, θ, ð, s, z, ʃ, h ([x, ç])

j, w ([ʍ] after /h/)

以下に,Chaucer の The General Prologue の冒頭の文章 (cf. 「#534. The General Prologue の冒頭の現在形と完了形」 ([2010-10-13-1])) を素材として,実践的に IPA で発音を記そう (Cruttenden 66) .

Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote

hʍan θat aːprɪl, wiθ hɪs ʃuːrəs soːtə

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

θə drʊxt ɔf marʧ haθ pɛrsəd toː ðe roːtə,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour

and baːðəd ɛːvrɪ vaɪn ɪn swɪʧ lɪkuːr

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

ɔf hʍɪʧ vɛrtɪʊ ɛnʤɛndərd ɪs θə flurː,

Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

hʍan zɛfɪrʊs ɛːk wɪθ hɪs sweːtə brɛːθ

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

ɪnspiːrəd haθ ɪn ɛːvrɪ hɔlt and hɛːθ

The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

θə tɛndər krɔppəs, and ðə jʊŋgə sʊnnə

Hath in the Ram his halve cours yronne,

haθ ɪn ðə ram hɪs halvə kʊrs ɪrʊnnə,

And smale foweles maken melodye,

and smɑːlə fuːləs maːkən mɛlɔdiːə

That slepen al the nyght with open ye

θat sleːpən ɑːl ðə nɪçt wiθ ɔːpən iːə

(So priketh hem nature in hir corages),

sɔː prɪkəθ hɛm naːtɪur ɪn hɪr kʊraːʤəs

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

θan lɔːŋgən fɔlk toː gɔːn ɔn pɪlgrɪmaːʤəs.

・ Cruttenden, Alan. Gimson's Pronunciation of English. 8th ed. Abingdon: Routledge, 2014.

2010-11-11 Thu

■ #563. Chaucer の merry [chaucer][spelling][lme]

昨日の記事[2010-11-10-1]で,中英語の方言事情に由来する綴字と発音の乖離を話題にした.結果としてみれば,busy や bury などは綴字と発音が標準化の際に別々に振る舞ってしまった不運な例であり,merry などは綴字と発音がセットで行動した幸運な例であったことになる.

これはあくまで偶然の結果である.ロンドンのような方言のるつぼでは,実際には綴字と発音のあらゆる組み合わせが試されたと想像べきだろう.busy でいえば,ロンドンでは /ɪ/, /y/, /ɛ/ の発音がいずれも聞かれたろうし,<i>, <u>, <e> の綴字のいずれも見られたろう.3×3=9通りの組み合わせのいずれもあり得たと想像される.標準化に際しての最終的な決定は,理性,慣用,ランダム性といった要素が複雑に作用した結果だったろう.標準化は短期間で起こったわけではなく,産みの苦しみとして多大な時間がかかったので,その間に後世からみれば妙に思われることが一つや二つ起こったとしても不思議ではない.busy や bury はそのような例と考えられる.

14世紀後半のロンドンでは,書き言葉の標準化が緩やかに始動していたが,そのロンドン英語をおよそ代表しているのが Chaucer である.先日 The Canterbury Tales の "The Nun's Priest's Tale" を読んでいて,merry に何度か出会ったので,異なる綴字を記録しながら読み進めてみた.以下,引用は The Riverside Chaucer より.

<myrie>

Be myrie, housbonde, for youre fader kyn! (l. 2968)

That stood ful myrie upon an haven-syde; (l. 3071)

Ther as he was ful myrie and wel at ese. (l. 3259)

Faire in the soond, to bathe hire myrily, (l. 3267; [:by])

How that they syngen wel and myrily). (l. 3272; [:sikerly])

For trewely, ye have as myrie a stevene (l. 3291)

<mery>

Of herbe yve, growyng in oure yeerd, ther mery is; (l. 2966)

And after that he, with ful merie chere, (l. 3461 in Epilogue to NPT)

<murie>

His voys was murier than the murie orgon (l. 2851)

Soong murier than the mermayde in the see (l. 3270)

This was a murie tale of Chauntecleer. (l. 3449 in Epilogue to NPT)

Chaucer にも予想通り,3通りの綴字があったことが分かる.このテキストに関する限り相対的に優勢なのは <myrie> だが,私たち後世が知っているとおり,後に標準化したのは最も少数派である <mery> の母音(字)をもつ形態である.書き言葉の標準化が徐々に進行したものであり,それゆえに標準化の過程には複雑な事情があったようだということがよく分かるのではないか.

2010-11-10 Wed

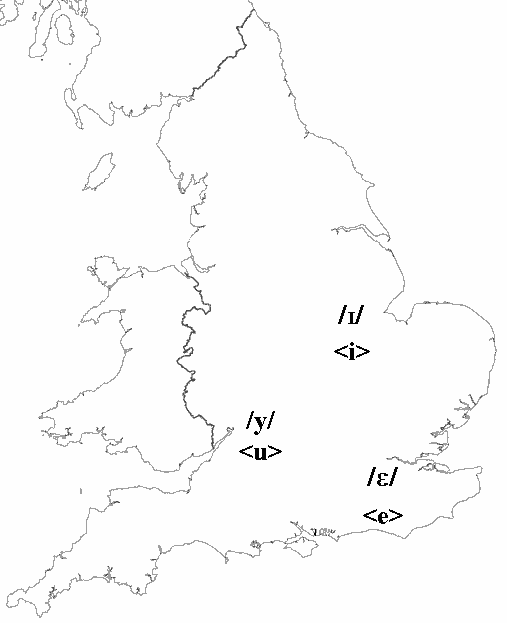

■ #562. busy の綴字と発音 [spelling][lme][me_dialect][spelling_pronunciation_gap][standardisation][map]

現代英語の綴字と発音の乖離には種々の歴史的背景がある.その歴史的原因のいくつかについては[2009-06-28-2]の記事で話題にしたが,そこの (2) で示唆したが明確には説明していない中英語期の方言事情があった.spelling-pronunciation gap の問題として現代英語にまで残った例は必ずしも多くないが,ここにはきわめて英語的な事情があった.

busy (及びその名詞形 business )を例にとって考えてみよう.busy の第1母音は <u> の綴字をもちながら /ɪ/ の発音を示す点で,英語語彙のなかでも最高度に不規則な語といっていいだろう.

この原因を探るには,中英語の方言事情を考慮に入れなければならない.[2009-09-04-1]で見たように,中英語期のイングランドには明確な方言区分が存在した.もちろんそれ以前の古英語にも以降の近代英語にも方言は存在したし,程度の差はあれ方言を発達させない言語はないと考えてよい.それでも,中英語が「方言の時代」と呼ばれ,その方言の存在が注目されるのは,書き言葉の標準が不在という状況下で,各方言が書き言葉のうえにずばり表現されていたからである.写字生は自らの話し言葉の「訛り」を書き言葉の上に反映し,結果として1つの語に対して複数の綴字が濫立する状況となった(その最も極端な例が[2009-06-20-1]で紹介した through の綴字である).

14世紀以降,緩やかにロンドン発祥の書き言葉標準らしきものが現われてくる.しかし,後の英語史が標準語の産みの苦しみの歴史だとすれば,中英語後期はその序章を構成するにすぎない.ロンドンは地理的にも方言の交差点であり,また全国から流入する様々な方言のるつぼでもあった.ロンドン方言を基盤としながらも種々の方言が混ざり合う混沌のなかから,時間をかけて,部分的には人為的に,部分的には自然発生的に標準らしきものが醸成されきたのである.

上記の背景を理解した上で中英語期の母音の方言差に話しを移そう.古英語で <y> (綴字),/y/ (発音)で表わされていた綴字と発音は,中英語の各方言ではそれぞれ次のように表出してきた.

大雑把にいって,イングランド北部・東部では <i> /ɪ/,西部・南西部では <u> /y/,南東部では <e> /ɛ/ という分布を示した(西部・南西部の綴字 <u> はフランス語の綴字習慣の影響である).したがって,古英語で <y> をもっていた語は,中英語では方言によって様々に綴られ,発音されたことになる.以下の表で例を示そう(中尾を参考に作成).

| Southwestern, West-Midland | North, East-Midland | Southeastern (Kentish) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OE forms | /y/ | /ɪ/ | /ɛ/ |

| byrgan "bury" | bury | biry | bery |

| bysig "busy" | busy | bisy | besy |

| cynn "kin" | kun | kin | ken |

| lystan "lust" | luste(n) | liste(n) | leste(n) |

| myrge "merry" | murie | myry | mery |

| synn "sin" | sunne | synne | senne, zenne |

さて,これらの方言別の諸形態がロンドンを中心とする地域で混ざり合った.書き言葉標準が時間をかけて徐々に生み出されるときに,後から考えれば実に妙に思える事態が生じた.多くの語では,ある方言の綴字と発音がセットで標準となった.例えば,merry は南東部方言の形態が標準化した例である.個々の語の標準形がどの方言に由来するかはランダムとしかいいようがないが,綴字と発音がセットになっているのが普通だった.ところが,少数の語では,発音はある方言のものから標準化したが,綴字は別の方言から標準化したということが起こった.busy がその例であり,発音は北部・東部の /ɪ/ が最終的に標準形として採用されたが,綴字は西部の <u> が採用された.そして,このちぐはぐな関係が現在にまで受け継がれている.bury (および名詞形 burial )も同様の事情で,現在,その綴字と発音の関係はきわめて不規則である.

ちなみに,上の地図の方言境界はおよそのものであり,語によっても当該母音の分布の異なるのが実際である.例えば,LALME Vol. 1 の dot maps 371--73 には busy の第1母音の方言分布が示されているが,<u> の期待される West-Midland へ,<e> や <i> の母音字が相当に張り出している.また,dot maps 972--74 では bury の第1母音の方言分布が示されているが,やはり <e> や <i> は「持ち場」の外でもぱらぱらと散見される.特にこの <e> と <i> はともに広く東部で重なって分布しているというのが正確なところだろう.

語の形態にみられる方言差の類例としては,[2009-07-25-1] ( one と will / won't ) , [2010-03-30-1] ( egg ) を参照.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『英語史 II』 英語学大系第9巻,大修館書店,1972年.38頁.

・ McIntosh, Angus, M. L. Samuels, and M. Benskin. A Linguistic Atlas of Late Mediaeval English. 4 vols. Aberdeen: Aberdeen UP, 1986.

2009-06-20 Sat

■ #53. 後期中英語期の through の綴りは515通り [spelling][lme][scribe][me_dialect][through]

現代英語の学習者が,初めて中英語で書かれたテキストを読もうとするときに驚くのは,スペリングの多様さである.例えば,後期中英語期には through という単語はなんと515通りもの異なるスペリングがあり得た.

doruȝ-, dorw, dorwe, dorwgh, dourȝh, drowgȝ, durghe, durwe, -thogh, thorch, thorew, thorewe, thorffe, thorg, Thorgh, thorgh, -thorgh, thorgh, thorghe, thorght, thorghw, thorghwe, thorgth, thorh, thoro, thorogh, thoroghe, thoroght, -thoroght, thorohe, thoroo, thorou, Thorough, thorough, thorough-, thoroughe, thorought, Thorouh, thorouȝ, thorouȝh, Thorow, thorow, thorow-, Thorowe, thorowe, thorowg, thorowgh, thorowghe, thorowght, thorowh, thorowth, thorowut, thorowȝ, thorowȝt, thorrou, thorrow, thorth, thorthe, thoru, thoru-, thorue, thorugh, -thorugh, thorughe, thorught, -thorught, Thoruh, thoruh, thoruh-, thorur, thoruth, Thoruȝ, thoruȝ, thoruȝh, thorv, Thorw, thorw, -thorw, thorw, Thorwe, thorwe, thorwgh, thorwh, thorwȝ, -thorwȝ, thorwȝ, thorwȝe, Thorȝ, thorȝ, Thorȝe, thorȝe, thorȝh, thorȝoh, thorȝt, thorȝw, thorȝwe, thour, thour, thoure, thourgh, -thourgh, thourghe, thourght-, thourh, thourhe, thourow, thourr, thourth, thourw, thourw, thourwg, thourȝ, thourȝ, thourȝe, thow, thowe, thowffe, thowr, thowrgh, thowrow, thowur, thrawth, threw, thro, thro-, -thro, throch, throcht, throgh, throghe, throghet, throght, throght, throghte, throighe, throu, throuche, throue, throug, through, through-, throughe, throught, throuh, throuȝ, throuȝe, throuȝht, throve, throw, throw-, throw, throwe, throwe, throwe, throwg, throwgh, throwght, throwh, throwr, throwth, throwȝ, throwȝe, throȝ, -throȝe, throȝe, throȝgh, throȝghe, throȝh, throȝhe, throȝt, thruch, thrue-, thrug-, Thrugh, thrugh, thrughe, thrught, thrughte, thruh, thruth, thruȝ, thruȝe, thruȝhe, thrvoo, thrw, thrwe, thrwgh, thrwght, thrygh, thuht, thur, thurch, thurew, thurg, thurge, thurge-, thurgeh, Thurgh, thurgh, thurgh-, -thurgh, thurgh, thurghe, thurght, thurghte, thurgth, thurgwe, Thurh, thurh, thurhe, thurhge, thurhgh, thuro, thurow, thurowe, thurth, thurthe, thuru, thurv, thurw, -thurw, thurwe, Thurȝ, thurȝ, thurȝe, Thurȝh, thurȝh, Thurȝhg, thurȝt, thurȝth, thwrgh, thwrw, torgh, torghe, torw, -torwe, trghug, trogh, troght, trough, trow, trowe, trowffe, trowgh, trowght, trugh, trughe, trught, twrw, yerowe, yhorh, yhoru, yhrow, yhurgh, yhurght, yora, yorch, yorgh, yorghe, yorh, yoro, yorou, yoroue, yorough, yorour, yorow, yorow-, yorowe, yorowe, yoru, yorugh, yoruh, yoruȝ, yorw, yorwe, yorȝ, your, yourch, yourgh, yourghe, yourh, yourw-, yourȝ, yowr, yowrw, yoȝou, yrogh, yrou-, yrow, yrugh, yruȝ, yurch, yurg-, yurgh, yurghe, yurght, yurh, yurhg, yurht, yurowe, yurth, yurthe, yuru, yurw, yurwh, yurȝ, yurȝe, ðoru, þarȝ, þerew, þerew, þerow, þerue-, þhorow, þhurȝ, þor, þorch, þore, þoreu, þorew, þorewe, þorewȝ, þoreȝ, þorg, -þorgh, þorgh, þorghe, þorght, þorghȝ, þorguh, þorgȝ, þorh, þoro, þorogh, þoroghe, þorou, þorou, þoroue, þorough, þorought, þorouh, þorour, -þorouȝ, þorouȝ, þorouȝe, þorouȝh, þorouȝt, þorow, -þorow, þorow, þorow, þorowe, þorowgh, þorowghe, þorowh, þorowth, þorowþ, þorouwȝ, þoroȝ, þorrow, þorrughe, þorth, þoru, -þoru, þorue, þorug, þorugh, þorught, þorugȝ, þoruh, þoruhg, þoruth, þoruþ, þoruȝ, -þoruȝ, þoruȝe, þoruȝh, þoruȝt, þorv, þorw, þorw-, -þorw, þorwe, þorwgh, þorwgȝ, þorwh, -þorwh, þorwhe, þorwth, þorwtȝ, þorwȝ, þorwȝe, þorþ, þorȝ, þorȝe, þorȝh, þorȝhȝ, þorȝt, þough, þour, þour, þour, þourg, þourgh, þourght, þourgȝ, þourh, þourh, þourow, þourt, þourth, þouruȝ, þourw, þourw-, -þourw, þourwe, þourþ, þourȝ, t-þourȝ, þourȝ, þourȝe, þourȝh, þourȝt, þourȝw, þouȝ, þouȝt, þowr, þowre, þro, þrogh, þroghe, þrorow, þrorowe, þroth, þrou, þrough, þrought, þroughte-, þrouh, þrouhe, þrouht, þrouȝ, þrouȝe, þrouȝh, þrouȝt, þrouȝte, þrouȝth, þrow, þrow, þrowe, þrowgh, þrowghe, þrowh, -þrowþ, þrowȝ, þrowȝe, þroȝ, þroȝe, þroȝgh, þroȝh, þroȝt, þroȝth, þrugh, -þruh, þruȝ, þruȝe, þur, þurch, þureh, þureȝ, þurf, þurg, þurgh, -þurgh, þurghe, þurght, þurghȝ, þurgȝh, þurh, þurh, þurhg, þurht, þuro, þurow, þurru, þurth, þurthe, þuru, þuruch, þurugh, þurughe, þurut, þuruȝ, þurw, þurw-, þurwe, þurwȝ, þurwȝ, þurþ, þurȝ, þurȝe, þurȝg, þurȝh, þurȝhg, þurȝt, þurȝth, þwrgh, ȝorgh, ȝoru, ȝoruȝ, ȝoruȝt, ȝorw, ȝour, ȝowr, ȝurch

壮観である.だが,なぜこんな状況になっていたのだろうか.

一言でいえば,標準スペリングというものがなかったということである.当時は規範となる辞書もなければ,スペリング・マスターのような人物もいない.写字生 ( scribe ) と呼ばれる書き手の各々が,およそ自分の発音に即して綴り字をあてたのである.例えば,イングランド北部・南部の出身の写字生では,方言がまるで違うわけであり,発音も相当異なったろう.そこで,同じ単語でもかなり異なった綴り字が用いられたはずである.さらには,同じ写字生でも,一つの単語が,数行後に異なるスペリングで書かれるということも珍しいことではない.スペリングがきちんと定まっている現代英語から見ると,信じがたい状況である.

英語のスペリングがおよそ現在のような形に落ち着いたのは,近代英語以降である.それも比較的ゆっくりと固まっていった.英語の試験で一字でも間違えたらバツということを我々は当たり前のように受け入れているが,中世の写字生がこの厳しい英語教育の現状を見たらなんというだろうか?

中英語のほうが余裕と遊びがあるようにも思えるが,さすがに515通りは行き過ぎか・・・.そもそも <trghug> なんてどう発音されたのだろうか?

(以下,後記:2025/01/15(Wed))

hellog 「#5738. 516番目の through を見つけました」 ([2025-01-11-1]) および heldio 「#1326. through の綴字,516通り目を発見!」 で紹介したとおり,久しぶりに新たな異綴りを見出しました.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow