2015-01-22 Thu

■ #2096. SUBTLEX-US Word Frequency List [frequency][statistics][corpus][lexicology][zipfs_law][cgi][web_service]

従来の英語学研究において,権威ある語彙頻度表といえばアメリカ英語に関する Kucera and Francis (1967) のものや,イギリス英語に比重を置いたより新しいものとして CELEX (1993) やその2版 (cf. 「#1424. CELEX2」 ([2013-03-21-1])) がよく用いられてきた.しかし,最近,これらを批判し,新しい手法に基づいたアメリカ英語の語彙頻度表が現われた.ベルギー,ヘント大学の実験心理学科の提供する SUBTLEXus である.左のHPから,SUBTLEXus の一群の頻度表のファイルや記述がダウンドーロできる.

SUBTLEXus の基盤にあるコーパスは,8388件の映画の字幕の集成であり,総語数は5100万語に及ぶ.SUBTLEXus の頻度表は,Kucera and Francis や CELEX の頻度表と比べて,いくつかの算出された指標においてすぐれていると主張されている.頻度は,見出し語 (lemma) ごとではなく語形 (word form) ごとに数えられており,例えば名詞であれば単数形と -s 語尾などをもつ複数形は別扱いされる(異なる語形は74,286種類).名詞と動詞など複数の品詞として用いられる語形については,それぞれの品詞ごとの頻度にもアクセスできるし,より優勢な品詞 (Dominant POS) のほうへ合算した頻度へもアクセスできる.データには,ほかに何件の映画に現われているか,小文字として現われているのは何回か,頻度の対数を取った指標,Zipf 指標 (cf. 「#1101. Zipf's law」 ([2012-05-02-1])) なども含まれている.これだけの種類のデータが含まれていると,目的とアイデア次第でおおいに有効に利用できるだろう.話し言葉ベースであることも顕著な特徴だ.

ダウンロードできるいくつかのデータのなかで "a zipped Excel file of SUBTLEX-US with the Zipf values included" をダウンロードし,少しいじってみた.例えば,(1) 全体的に多く現われ,かつ (2) 多くの映画にも現われる語形は,総合的な意味で頻度が高いと考えられるだろう.そこで (1) と (2) に関する対数の指標を掛け合わせて,それを降順に並べて最初の100語を取ると,正真正銘の最頻単語100語が得られるはずだ.省略形の片割れなども含まれているが,以下がそのリストである.

you, I, the, to, s, a, it, t, that, and, of, what, in, me, is, we, this, he, on, for, my, m, your, don, have, do, re, no, be, know, was, not, can, are, all, with, just, get, here, but, there, ll, so, they, like, right, out, go, up, about, she, if, him, got, at, now, come, oh, one, how, well, want, yeah, her, think, good, see, let, did, why, who, as, going, his, will, from, when, back, time, yes, look, d, take, an, where, man, would, them, been, some, or, tell, us, had, were, say, could, gonna, didn, hey

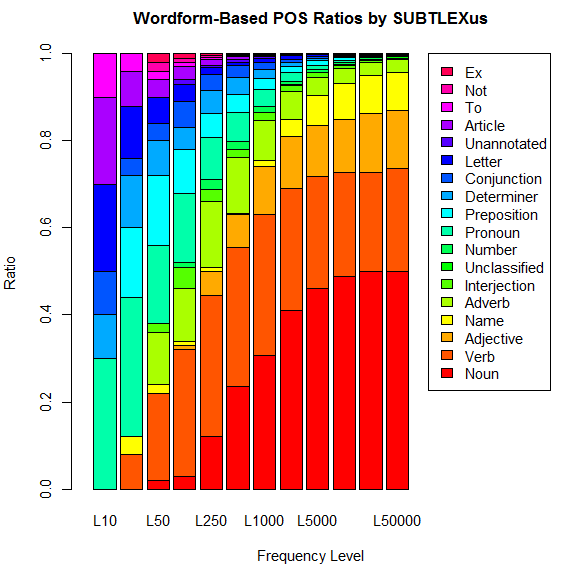

ほかには,最頻10語,25語,50語,100語,250語,500語,1,000語,2,500語,5,000語,10,000語,25,000語,50,000語,100,000語について,Dominant POS ごとに数え上げてみることもたやすい.「#666. COCA 最頻5000語で品詞別の割合は?」 ([2011-02-22-1]),「#667. COCA 最頻50万語で品詞別の割合は?」 ([2011-02-23-1]),「#1132. 英単語の品詞別の割合」 ([2012-06-02-1]) の記事でも,別のコーパスにより似たような調査を行ったが,SUBTLEX-US 版の調査結果は次のグラフにまとめられる.

以下はおまけの検索ツール (SUBTLEX-US Word Frequency Extractor) .おまけなので,10例までしか結果が出力されない仕様です.SUBTLEXus の提供する複雑な検索も可能な,SUBTLEXus Online Search もどうぞ.

2014-12-29 Mon

■ #2072. 英語語彙の三層構造の是非 [lexicology][loan_word][latin][french][register][synonym][romancisation][lexical_stratification]

英語語彙の三層構造について「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]),「#335. 日本語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-28-1]),「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1]),「#1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造」 ([2014-09-08-1]) など,多くの記事で言及してきた.「#1366. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2013-01-22-1]) でみたように,語彙の三層構造ゆえに英語は非民主的な言語であるとすら言われることがあるが,英語語彙のこの特徴は見方によっては是とも非となる類いのものである.

Jespersen (121--39) がその是と非の要点を列挙している.まず,長所から.

(1) 英仏羅語に由来する類義語が多いことにより,意味の "subtle shades" が表せるようになった.

(2) 文体的・修辞的な表現の選択が可能になった.

(3) 借用語には長い単語が多いので,それを使う話者は考慮のための時間を確保することができる.

(4) ラテン借用語により国際性が担保される.

まず (1) と (2) は関連しており,表現力の大きさという観点からは確かに是とすべき項目だろう.日本語語彙の三層構造と比較すれば,表現者にとってのメリットは実感されよう.しかし,聞き手や学習者にとっては厄介な特徴ともいえ,その是非はあくまで相対的なものであるということも忘れてはならない.(3) はおもしろい指摘である.非母語話者として英語を話す際には,ミリ秒単位(?)のごく僅かな時間稼ぎですら役に立つことがある.長い単語で時間稼ぎというのは,状況にもよるが,戦略としては確かにあるのではないか.(4) はラテン借用語だけではなくギリシア借用語についても言えるだろう.関連して「#512. 学名」 ([2010-09-21-1]) や「#1694. 科学語彙においてギリシア語要素が繁栄した理由」 ([2013-12-16-1]) も参照されたい.

次に,Jespersen が挙げている短所を列挙する.

(5) 不必要,不適切なラテン借用語の使用により,意味の焦点がぼやけることがある.

(6) 発音,綴字,派生語などについて記憶の負担が増える.例えば,「#859. gaseous の発音」 ([2011-09-03-1]) の各種のヴァリエーションの問題や「#573. 名詞と形容詞の対応関係が複雑である3つの事情」 ([2010-11-21-1]) でみた labyrinth の派生形容詞の問題などは厄介である.

(7) 科学の日常化により,関連語彙には国際性よりも本来語要素による分かりやすさが求められるようになってきている.例えば insomnia よりも sleeplessness のほうが分かりやすく有用であるといえる.

(8) 非本来語由来の要素の導入により,派生語間の強勢位置の問題が生じた (ex. Cánada vs Canádian) .

(9) ラテン語の複数形 (ex. phenomena, nuclei) が英語へもそのまま持ち越されるなどし,形態論的な統一性が崩れた.

(10) 語彙が非民主的になった.

是と非とはコインの表裏の関係にあり,絶対的な判断は下しにくいことがわかるだろう.結局のところ,英語の語彙構造それ自体が問題というよりは,それを使用者がいかに使うかという問題なのだろう.現代英語の語彙構造は,各時代の言語接触などが生み出してきた様々な語彙資源の歴史的堆積物にすぎず,それ自体に良いも悪いもない.したがって,そこに民主的あるいは非民主的というような評価を加えるということは,評価者が英語語彙を見る自らの立ち位置を表明しているということである.Jespersen (139) は次の総評をくだしている.

While the composite character of the language gives variety and to some extent precision to the style of the greatest masters, on the other hand it encourages an inflated turgidity of style. . . . [W]e shall probably be near the truth if we recognize in the latest influence from the classical languages 'something between a hindrance and a help'.

日本語において明治期に大量に生産された(チンプン)漢語や20世紀にもたらされた夥しいカタカナ語にも,似たような評価を加えることができそうだ(「#1999. Chuo Online の記事「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」」 ([2014-10-17-1]) とそこに張ったリンク先を参照).

英語という言語の民主性・非民主性という問題については「#134. 英語が民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2009-09-08-1]),「#1366. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2013-01-22-1]),「#1845. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由 (2)」 ([2014-05-16-1]) で取り上げたので,そちらも参照されたい.また,英語語彙のロマンス化 (romancisation) に関する評価については「#153. Cosmopolitan Vocabulary は Asset か?」 ([2009-09-27-1]) や「#395. 英語のロマンス語化についての評」 ([2010-05-27-1]) を参照.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Growth and Structure of the English Language. 10th ed. Chicago: U of Chicago, 1982.

2014-10-17 Fri

■ #1999. Chuo Online の記事「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」 [japanese][katakana][kanji][lexicology][lexicography][inkhorn_term][loan_word][waseieigo][link]

ヨミウリ・オンライン(読売新聞)内に,中央大学が発信するニュースサイト Chuo Online がある.そのなかの 教育×Chuo Online へ寄稿した「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」と題する私の記事が,昨日(2014年10月16日)付で公開されたので,関心のある方はご参照ください.ちょうど今期の英語史概説の授業で,この問題の英語版ともいえる初期近代英語期のインク壺語 (inkhorn_term) を巡る論争について取り上げる矢先だったので,とてもタイムリー.数週間後に記事の英語版も公開される予定. *

上の投稿記事に関連する内容は本ブログでも何度か取り上げてきたものなので,関係する外部リンクと合わせて,この機会にリンクを張っておきたい.

・ 文化庁による平成25年度「国語に関する世論調査」

・ 「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1])

・ 「#296. 外来宗教が英語と日本語に与えた言語的影響」 ([2010-02-17-1])

・ 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1])

・ 「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1])

・ 「#609. 難語辞書の17世紀」 ([2010-12-27-1])

・ 「#845. 現代英語の語彙の起源と割合」 ([2011-08-20-1])

・ 「#1067. 初期近代英語と現代日本語の語彙借用」 ([2012-03-29-1])

・ 「#1202. 現代英語の語彙の起源と割合 (2)」 ([2012-08-11-1])

・ 「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1])

・ 「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1])

・ 「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1])

・ 「#1493. 和製英語ならぬ英製羅語」 ([2013-05-29-1])

・ 「#1526. 英語と日本語の語彙史対照表」 ([2013-07-01-1])

・ 「#1606. 英語言語帝国主義,言語差別,英語覇権」 ([2013-09-19-1])

・ 「#1615. インク壺語を統合する試み,2種」 ([2013-09-28-1])

・ 「#1616. カタカナ語を統合する試み,2種」 ([2013-09-29-1])

・ 「#1617. 日本語における外来語の氾濫」 ([2013-09-30-1])

・ 「#1624. 和製英語の一覧」 ([2013-10-07-1])

・ 「#1629. 和製漢語」 ([2013-10-12-1])

・ 「#1630. インク壺語,カタカナ語,チンプン漢語」 ([2013-10-13-1])

・ 「#1645. 現代日本語の語種分布」 ([2013-10-28-1]) とそこに張ったリンク集

・ 「#1869. 日本語における仏教語彙」 ([2014-06-09-1])

・ 「#1896. 日本語に入った西洋語」 ([2014-07-06-1])

・ 「#1927. 英製仏語」 ([2014-08-06-1])

(後記 2014/10/30(Thu):英語版の記事はこちら. *)

2014-10-13 Mon

■ #1995. Mulcaster の語彙リスト "generall table" における語源的綴字 [mulcaster][lexicography][lexicology][cawdrey][emode][dictionary][spelling_reform][etymological_respelling][final_e]

昨日の記事「#1994. John Hart による語源的綴字への批判」 ([2014-10-12-1]) や「#1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論」 ([2014-08-18-1]),「#1940. 16世紀の綴字論者の系譜」 ([2014-08-19-1]),「#1943. Holofernes --- 語源的綴字の礼賛者」 ([2014-08-22-1]) で Richard Mulcaster の名前を挙げた.「#441. Richard Mulcaster」 ([2010-07-12-1]) ほか mulcaster の各記事でも話題にしてきたこの初期近代英語期の重要人物は,辞書編纂史の観点からも,特筆に値する.

英語史上最初の英英辞書は,「#603. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (1)」 ([2010-12-21-1]),「#604. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (2)」 ([2010-12-22-1]),「#726. 現代でも使えるかもしれない教育的な Cawdrey の辞書」 ([2011-04-23-1]),「#1609. Cawdrey の辞書をデータベース化」 ([2013-09-22-1]) で取り上げたように,Robert Cawdrey (1537/38--1604) の A Table Alphabeticall (1604) と言われている.しかし,それに先だって Mulcaster が The First Part of the Elementarie (1582) において約8000語の語彙リスト "generall table" を掲げていたことは銘記しておく必要がある.Mulcaster は,教育的な見地から英語辞書の編纂の必要性を訴え,いわば試作としてとしてこの "generall table" を世に出した.Cawdrey は Mulcaster に刺激を受けたものと思われ,その多くの語彙を自らの辞書に採録している.Mulcaster の英英辞書の出版を希求する切実な思いは,次の一節に示されている.

It were a thing verie praiseworthie in my opinion, and no lesse profitable then praise worthie, if som one well learned and as laborious a man, wold gather all the words which we vse in our English tung, whether naturall or incorporate, out of all professions, as well learned as not, into one dictionarie, and besides the right writing, which is incident to the Alphabete, wold open vnto vs therein, both their naturall force, and their proper vse . . . .

上の引用の最後の方にあるように,辞書編纂史上重要なこの "generall table" は,語彙リストである以上に,「正しい」綴字の指南書となることも目指していた.当時の綴字改革ブームのなかにあって Mulcaster は伝統主義の穏健派を代表していたが,穏健派ながらも final e 等のいくつかの規則は提示しており,その効果を具体的な単語の綴字の列挙によって示そうとしたのである.

For the words, which concern the substance thereof: I haue gathered togither so manie of them both enfranchised and naturall, as maie easilie direct our generall writing, either bycause theie be the verie most of those words which we commonlie vse, or bycause all other, whether not here expressed or not yet inuented, will conform themselues, to the presidencie of these.

「#1387. 語源的綴字の採用は17世紀」 ([2013-02-12-1]) で,Mulcaster は <doubt> のような語源的綴字には否定的だったと述べたが,それを "generall table" を参照して確認してみよう.EEBO (Early English Books Online) のデジタル版 The first part of the elementarie により,いくつかの典型的な語源的綴字を表わす語を参照したところ,auance., auantage., auentur., autentik., autor., autoritie., colerak., delite, det, dout, imprenable, indite, perfit, receit, rime, soueranitie, verdit, vitail など多数の語において,「余分な」文字は挿入されていない.確かに Mulcaster は語源的綴字を受け入れていないように見える.しかし,他の語例を参照すると,「余分な」文字の挿入されている aduise., language, psalm, realm, salmon, saluation, scholer, school, soldyer, throne なども確認される.

語によって扱いが異なるというのはある意味で折衷派の Mulcaster らしい振る舞いともいえるが,Mulcaster の扱い方の問題というよりも,当時の各語各綴字の定着度に依存する問題である可能性がある.つまり,すでに語源的綴字がある程度定着していればそれがそのまま採用となったということかもしれないし,まだ定着していなければ採用されなかったということかもしれない.Mulcaster の選択を正確に評価するためには,各語における語源的綴字の挿入の時期や,その拡散と定着の時期を調査する必要があるだろう.

"generall table" のサンプル画像が British Library の Mulcaster's Elementarie より閲覧できるので,要参照. *

2014-09-15 Mon

■ #1967. 料理に関するフランス借用語 [loan_word][french][lexicology][norman_conquest][semantic_field][recipe]

昨日の記事「#1966. 段々おいしくなってきた英語の飲食物メニュー」 ([2014-09-14-1]) で,英語の料理や飲食物に関する語彙には,歴史的にフランス借用語が幅を利かせてきたことを確認した.その背景にあるのは,疑いなく1066年のノルマン・コンクェエストである.それ以降,「#331. 動物とその肉を表す英単語」 ([2010-03-24-1]) で典型的に知られているように,アングロサクソン系の大多数の庶民は家畜の世話に追われ,フランス系の上流階級はフランスの料理に舌鼓を打った.イングランドにおいてフランス料理は,単においしいだけでなく,権威や洗練の象徴として社会的な含意をもっていた.

動物とその肉料理に関する sheep / mutton; ox / beef; pig / pork, bacon, gammon; calf / veal; boar / brawn; fowl / poultry の英仏語彙の対立はよく知られているが,ほかにもフランス借用語が料理に関する意味場を広く占めている証拠はたくさんある.昨日の記事で引用した Hughes は,"The sociology of food" (117--20) と題する節で,興味深い事例を列挙している.

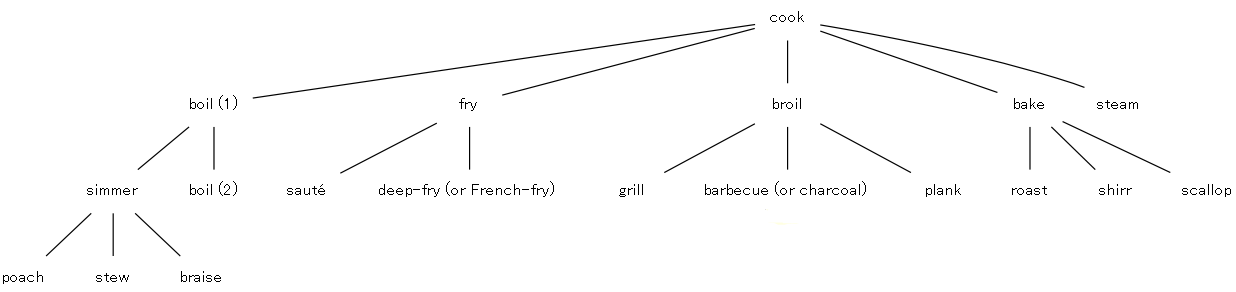

まず,動物の可食部位で上質な部位と下等な部位とで呼び名が異なるという事実がある.haunch, joint, cutlet はフランス語だが,brains, tongue, shank は英語だ.ある程度豪華な食事を表わす dinner, supper, banquet はフランス語だが,質素な breakfast は英語だ(なお,lunch は16世紀末に初出し,昼食の意では19世紀から).火を通す調理法は「#1962. 概念階層」 ([2014-09-10-1]) の COOK の配下に挙げた boil, broil, roast, grill, fry など多くの動詞がフランス語だ.スープ,デザート,調味料など風味の素材も然り (ex. soup, potage, sauce, dessert, mustard, cream, ginger, liquorice, flan, pasty, claret, biscuit) .アングロ・サクソンの食文化のひもじさが悲しいほどだ.

中世のご馳走を用意する係の名前にもフランス語が目立つ.steward (給仕長)こそ英語だが(sty + ward で「豚小屋世話人」というのが皮肉),marshal (接待係),sewer (配膳方),pantler (食料貯蔵室管理人),butler (執事)はフランス語である.下働きの scullion (皿洗い男),blackguard (召使い),pot-boy (ボーイ)はいずれも英語である.

最後に,15世紀のレシピの英文を覗いてみよう.Hughes (118) からの再引用だが,イタリック体の語がフランス借用語である.いかに料理の意味場がフランス語かぶれしているかが分かるだろう.

Oystres in grauey

Take almondes, and blanche hem, and grinde hem and drawe þorgh a streynour with wyne, and with goode fressh broth into gode mylke, and sette hit on þe fire and lete boyle; and cast therto Maces, clowes, Sugur, pouder of Ginger, and faire parboyled oynons mynced; And þen take faire oystres, and parboile hem togidre in faire water; And then caste hem ther-to, And let hem boyle togidre til þey ben ynowe; and serve hem forth for gode potage.

いかにもフランス語かぶれしている.しかし,かぶれていなかったら,今でさえ評価されることの少ないイングランドの食事情は,さらに貧しいものとなったに違いない.人たるもの,食の分野において purism の議論はあり得ない.

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-09-14 Sun

■ #1966. 段々おいしくなってきた英語の飲食物メニュー [loan_word][french][history][lexicology]

Hughes (119) に,眺めているだけでおいしくなってくる英語の "A historical menu" が掲載されている.古英語期から現代英語期までに次々と英語へ入ってきた飲食物を表わす借用語が,時代順に並んでいる.Hughes は現代から古英語へと遡るように一覧を提示しており,昔の食べ物は素朴だったなあという感慨を得るにはよいのだが,下から読んだほうが圧倒的に食欲が増すので,そのように読むことをお勧めしたい.

| Food | Drink | |

|---|---|---|

| pesto, salsa, sushi | ||

| tacos, quiche, schwarma | ||

| pizza, osso bucco | Chardonnay | |

| 1900 | paella, tuna, goulash | |

| hamburger, mousse, borscht | Coca Cola | |

| grapefruit, éclair, chips | soda water | |

| bouillabaisse, mayonnaise | ||

| ravioli, crêpes, consommé | riesling | |

| 1800 | spaghetti, soufflé, bechamel | tequila |

| ice cream | ||

| kipper, chowder | ||

| sandwich, jam | seltzer | |

| meringue, hors d'oeuvre, welsh rabbit | whisky | |

| 1700 | avocado, pâté | gin |

| muffin | port | |

| vanilla, mincemeat, pasta | champagne | |

| salmagundi | brandy | |

| yoghurt, kedgeree | sherbet | |

| 1600 | omelette, litchi, tomato, curry, chocolate | tea, sherry |

| banana, macaroni, caviar, pilav | coffee | |

| anchovy, maize | ||

| potato, turkey | ||

| artichoke, scone | sillabub | |

| 1500 | marchpane (marzipan) | |

| whiting, offal, melon | ||

| pineapple, mushroom | ||

| salmon, partridge | ||

| Middle English | venison, pheasant | muscatel |

| crisp, cream, bacon | rhenish (rhine wine) | |

| biscuit, oyster | claret | |

| toast, pastry, jelly | ||

| ham, veal, mustard | ||

| beef, mutton, brawn | ||

| sauce, potage | ||

| broth, herring | ||

| meat, cheese | ale | |

| Old English | cucumber, mussel | beer |

| butter, fish | wine | |

| bread | water |

予想通りフランス借用語が多いものの,全体的にはバラエティ豊かで多国籍風である.

料理の分野におけるフランス語については,ほかにも「#61. porridge は愛情をこめて煮込むべし」 ([2009-06-28-1]),「#331. 動物とその肉を表す英単語」 ([2010-03-24-1]),「#332. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」の神話」 ([2010-03-25-1]),「#1583. swine vs pork の社会言語学的意義」 ([2013-08-27-1]),「#1603. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」を最初に指摘した人」 ([2013-09-16-1]),「#678. 汎ヨーロッパ的な18世紀のフランス借用語」 ([2011-03-06-1]),「#1792. 18--20世紀のフランス借用語」 ([2014-03-24-1]),「#1667. フランス語の影響による形容詞の後置修飾 (1)」 ([2013-11-19-1]),「#1210. 中英語のフランス借用語の一覧」 ([2012-08-19-1]) を参照.

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-09-13 Sat

■ #1965. 普遍的な語彙素 [lexicology][glottochronology][semantics][lexeme][componential_analysis]

先日の「#1961. 基本レベル範疇」 ([2014-09-09-1]) の記事で,基本語彙あるいは基礎語彙の話題を取り上げたときに,Swadesh の提案した基礎語彙に言及した.これは「#1128. glottochronology」 ([2012-05-29-1]) で挙げた100語からなる basic vocabulary のことであり,通言語的に普遍的な基礎語彙であると唱えられている.批判も多いが,比較言語学や歴史言語学では core vocabulary に関する影響力のある提案の1つと認識されている.

core vocabulary を同定するもう1つの試みとして,Wierzbicka や Goddard の提案がある.Swadesh の提案が比較言語学を基盤としているのに対し,Wierzbicka らの提案は意味論を基盤としている.意味論には,ちょうど音韻論において普遍的な弁別素性が仮定されるのと同様に,普遍的な意味の原子要素 (semantic primes) があるはずだと考え,それを同定しようとする伝統がある.これは,意味の成分分析 (componential_analysis) の伝統の延長線上にある.決して成功しているとはいえないが,意味のプリミティヴを追求するというこの魅力的な計画には,これまでも多くの研究者が参加してきた.Goddard もこの計画に魅せられた1人であり,使命感をもって次のように述べている(Cliff Goddard ("Lexico-Semantic Universals: A Critical overview." Linguistic Typology 5.1 (2001): 1--65. p. 3) から引用した Saeed (78) より).

Natural Semantic Metalanguage

. . . a 'meaning' of an expression will be regarded as a paraphrase, framed in semantically simpler terms than the original expression, which is substitutable without change of meaning into all contexts in which the original expression can be used . . . The postulate implies the existence, in all languages, of a finite set of indefinable expressions (words, bound morphemes, phrasemes). The meanings of these indefinable expressions, which represent the terminal elements of language-internal semantic analysis, are known as 'semantic primes'.

具体的には,Wierzbicka と Goddard により,次の60語が "universal semantic primes" として提案されている(Saeed 79).諸言語の語彙を比較調査した上でより抜かれた精鋭の語彙素だといわれる.

| Substantives: | I, you, someone/person, something, body |

| Determiners: | this, the same, other |

| Quantifiers: | one, two, some, all, many/much |

| Evaluators: | good, bad |

| Descriptors: | big, small |

| Mental predicates: | think, know, want, feel, see, hear |

| Speech: | say, word, true |

| Actions, events, movement: | do, happen, move, touch |

| Existence and possession: | is, have |

| Life and death: | live, die |

| Time: | when/time, now, before, after, a long time, a short time, for some time, moment |

| Space: | where/place, here, above, below |

| 'Logical' concepts: | not, maybe, can, because, if |

| Intensifier, augmentor: | very, more |

| Taxonomy: | kind (of), part (of) |

| Similarity: | like |

意味の原子要素を同定するということは一種のメタ言語,論理的な言語をもつことにつながるが,Wierzbicka や Goddard はそれをあえて自然言語の語彙素に対応させて示そうとした.できあがった語彙リストは,したがって,基礎語彙のリストというよりは,普遍的な意味の原子要素を反映する語彙素のリストとして提案されたのである.

・ Saeed, John I. Semantics. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

2014-09-10 Wed

■ #1962. 概念階層 [lexicology][semantics][hyponymy][terminology][semantic_field][cognitive_linguistics]

昨日の記事「#1961. 基本レベル範疇」 ([2014-09-09-1]) で,概念階層 (conceptual hierarchy) あるいは包摂関係 (hyponymy) という術語を出した.後者の包摂関係は語彙的な関係を念頭においた見方であり,「家具」と「いす」の例で考えれば,「家具」は「いす」の上位語 (hypernym) であるといわれ,「いす」は「家具」の下位語 (hyponym) であるといわれる.一方,前者の概念階層は概念間の関係を念頭においた見方であり,上位と下位の関係が幾重にも広がり,巨大なネットワークが展開されているととらえる.

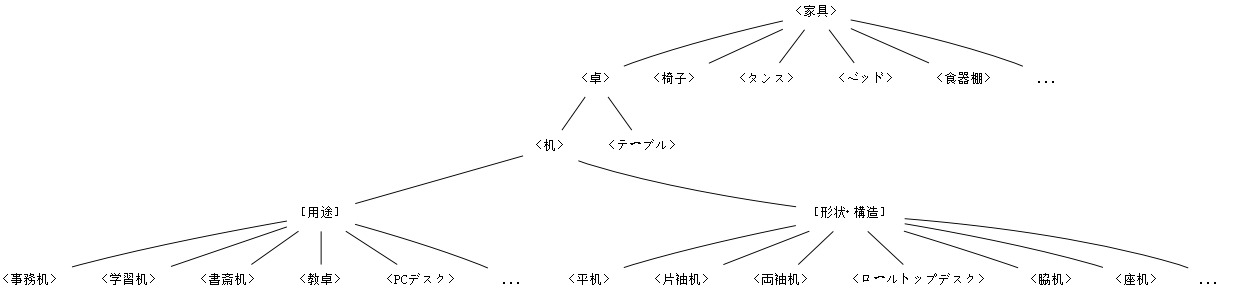

概念階層を理解するは,具体的にある意味場 (semantic_field) を取り上げ,関係を図示してみるのがよい.生物学における界 (kingdom),門 (phylum or division),綱 (class),目 (order),科 (family),属 (genus),種 (species) の分類図はよく知られた概念階層であるし,比較言語学の系統図 (family_tree) もその一種である.以下では中野 (17) に挙げられている日本語「家具」の意味場における概念階層と,英語 COOK(動詞)の意味場における概念階層を示す.

「家具」について[用途]と[形状・構造]というノードがあるが,これはそれ以下の分類が視点に基づいたものであることを示す.意味場に応じてあり得る視点も変わるだろうし,個人によっても異なる可能性があるので,上の図は1つのモデルと考えたい.

すぐに気づくように,概念階層は語彙学習にも役立つ.上記の COOK は動詞の例だが,FURNITURE, FRUIT, VEHICLE, WEAPON, VEGETABLE, TOOL, BIRD, SPORT, TOY, CLOTHING などの名詞の概念階層を描いてみると勉強になりそうだ.

・ 中野 弘三(編)『意味論』 朝倉書店,2012年.

2014-09-09 Tue

■ #1961. 基本レベル範疇 [lexicology][semantics][cognitive_linguistics][prototype][glottochronology][basic_english][hyponymy][terminology][semantic_field]

昨日の記事「#1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造」 ([2014-09-08-1]) の最後で,「語彙階層は,基本性,日常性,文体的威信の低さ,頻度,意味・用法の広さといった諸相と相関関係にある」と述べた.言語学では,しばしば「基本的な語彙」が話題になるが,何をもって基本的とするかについては様々な立場がある.直感的には,基本的な語彙とは,日常的に用いられ,高頻度で,子供にも早期に習得される語彙であると済ませることもできそうだし,確かにそれで大きく外れていないと思う.しかし,どこまでを基本語彙と認めるかという問題や,個別言語ごとに異なるものなのか,あるいは通言語的にある程度は普遍的なものなのかという問題もあり,易しいようで難しいテーマである.例えば,言語学史的には「#1128. glottochronology」 ([2012-05-29-1]) を提唱した Swadesh の綴字した基礎語彙に対して,猛烈な批判が加えられたという事例もあったし,実用的な目的で唱えられた Basic English (cf. 「#960. Basic English」 ([2011-12-13-1]),「#1705. Basic English で書かれたお話し」 ([2013-12-27-1])) とその基本語彙についても,疑念の目が向けられたことがあった.

基本的な語彙ということでもう1つ想起されるのは,認知意味論でしばしば取り上げられる基本レベル範疇 (Basic Level Category) である.語彙的な関係の1つに,概念階層 (conceptual hierarchy) あるいは包摂関係 (hyponymy) というものがある.例えば,「家具」という意味場 (semantic_field) を考えてみる.「家具」という包括的なカテゴリーの下に「いす」や「机」のカテゴリーがあり,それぞれの下に「肘掛けいす」「デッキチェア」や「勉強机」「パソコンデスク」などがある.さらに上にも下にも,そして横にもこのような語彙関係が広がっており,「家具」の意味場に巨大な語彙ネットワークが展開しているというのが,意味論や語彙論の考え方だ.ここで「家具」「いす」「肘掛けいす」という3段階の包摂関係について注目すると,最も普通のレベルは真ん中の「いす」と考えられる.「ちょっと疲れたから,いすに座りたいな」は普通だが,「家具に座りたいな」は抽象的で粗すぎるし,「肘掛けいすに座りたいな」は通常の文脈では不自然に細かすぎる.「いす」というレベルが,抽象的すぎず一般的すぎず,ちょうどよいレベルという感覚がある.ここでは,「いす」が Basic Level Category を形成しているといわれる.

では,この Basic Level Category は何によって決まるのだろうか.Taylor (52) は,プロトタイプ理論の権威 Rosch に依拠しながら,次のような機能主義的な説明を支持している.

Rosch argues that it is the basic level categories that most fully exploit the real-world correlation of attributes. Basic level terms cut up reality into maximally informative categories. The basic level, therefore, is the level in a categorization hierarchy at which the 'best' categories can emerge. More precisely, Rosch hypothesizes that basic level categories both

(a) maximize the number of attributes shared by members of the category;

and

(b) minimize the number of attributes shared with members of other categories.

「いす」は,その配下の様々な種類のいす,例えば「肘掛けいす」や「デッキチェア」と多くの共通の特性をもつ点で (a) にかなう.また,「いす」は,「机」や様々な種類の机,例えば「勉強机」や「パソコンデスク」と共有する特性は少ないので,(b) にかなう.これは「いす」を中心にして考えた場合だが,同じように「家具」あるいは「肘掛けいす」を中心に考えて (a) と (b) にかなうかどうかを検査してみると,いずれも「いす」ほどには両条件を満たさない.

Basic Level Category の語彙は,認知的に重要と考えられている.また,日常的に最もよく使われ,子供によって最初に習得され,大人も最も速く反応することが知られている.ある種の基本性を備えた語彙といえるだろう.

基本語彙の別の見方については,「#308. 現代英語の最頻英単語リスト」 ([2010-03-01-1]),「#1874. 高頻度語の語義の保守性」 ([2014-06-14-1]),「#1101. Zipf's law」 ([2012-05-02-1]) の記事も参照されたい.

・ Taylor, John R. Linguistic Categorization. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 2003.

2014-09-08 Mon

■ #1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造 [register][lexicology][loan_word][latin][french][greek][semantics][polysemy][lexical_stratification]

英語語彙に特徴的な三層構造について,「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]),「#335. 日本語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-28-1]),「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1]) などの記事でみてきた.三層構造という表現が喚起するのは,上下関係と階層のあるビルのような建物のイメージかもしれないが,ビルというよりは,裾野が広く頂点が狭いピラミッドのような形を想像するほうが妥当である.つまり,下から,裾野の広い低階層の本来語彙,やや狭まった中階層のフランス語彙,そして著しく狭い高階層のラテン・ギリシア語彙というイメージだ.

ピラミッドの比喩が適切なのは,1つには,高階層のラテン・ギリシア語彙のもつ特権的な地位と威信がよく示されているからだ.社会言語学的,文体的に他を圧倒するポジションについていることは,ビル型よりもピラミッド型のほうがよく表現できる.

2つ目として,それぞれの語彙の頻度が,ピラミッドにおける各階層の面積として表現できるからである.昨日の記事「#1959. 英文学史と日本文学史における主要な著書・著者の用いた語彙における本来語の割合」 ([2014-09-07-1]) でみたように,話し言葉のみならず書き言葉においても,本来語彙の頻度は他を圧倒している(なお,この分布は,「#1645. 現代日本語の語種分布」 ([2013-10-28-1]) でみたように,現代日本語においても同様だった).対照的に,高階層の語彙は頻度が低い.個々の語については反例もあるだろうが,全体的な傾向としては,各階層の頻度と面積とは対応する.もっとも,各階層の語彙量(異なり語数)ということでいえば,必ずしもそれがピラミッドの面積に対応するわけでない.最頻100語(cf. 「#309. 現代英語の基本語彙100語の起源と割合」 ([2010-03-02-1]) と最頻600語(cf. 「#202. 現代英語の基本語彙600語の起源と割合」 ([2009-11-15-1]))で見る限り,語彙量と面積はおよそ対応しているが,10000語というレベルで調査すると,「#429. 現代英語の最頻語彙10000語の起源と割合」 ([2010-06-30-1]) でみたように,上で前提としてきた3階層の上下関係は崩れる.

ピラミッドの比喩が有効と考えられる3つ目の理由は,ピラミッドにおける各階層の面積が,頻度のみならず,構成語のもつ意味と用法の広さにも対応しているからだ.本来語は相対的に卑近であり頻度も高いが,そればかりでなく,多義であり,用法が多岐にわたる.基本的な語義が同じ「与える」でも,本来語 give は派生的な語義も多く極めて多義だが,ラテン借用語 donate は語義が限定されている.また,give は文型として SVOiOd も SVOd to Oi も取ることができる(すなわち dative shift が可能だ)が,donate は後者の文型しか許容しない.ほかには「#112. フランス・ラテン借用語と仮定法現在」 ([2009-08-17-1]) で示唆したように,語彙階層が統語的な振る舞いに関与していると疑われるケースがある.

この第3の観点から,Hughes (43) は,次のようなピラミッド構造を描いた.

![]()

上記の3点のほかにも,各階層の面積と語の理解しやすさ (comprehensibility) が関係しているという見方もある.結局のところ,語彙階層は,基本性,日常性,文体的威信の低さ,頻度,意味・用法の広さといった諸相と相関関係にあるということだろう.ピラミッドの比喩は巧みである.

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-09-07 Sun

■ #1959. 英文学史と日本文学史における主要な著書・著者の用いた語彙における本来語の割合 [statistics][lexicology][literature][style][japanese]

標題について,Hughes (42) は,Frederic T. Wood (An Outline History of the English Language. London: Heinemann, 1959. p.47) を参照して,数値を挙げている.以下にグラフ化して示そう.

King James Bible (1611) (94%): ********************************************************************************

Shakespeare (1564--1616) (90%): ****************************************************************************

Spenser (c1552--99) (86%): *************************************************************************

Milton (1608--74) (81%): ********************************************************************

Addison (1672--1719) (82%): *********************************************************************

Swift (1667--1745) (75%): ***************************************************************

Pope (1688--1744) (80%): ********************************************************************

Johnson (1709--84) (72%): *************************************************************

Hume (1711--76) (73%): **************************************************************

Gibbon (1737--94) (70%): ***********************************************************

Macaulay (1881--1958) (75%): ***************************************************************

Tennyson (1850--92) (77%): *****************************************************************

最高値を示す The King James Version が94%,最低値を示す Gibbon が70%だが,いずれにせよ相当に高い割合で本来語が用いられていることがわかる.話し言葉において本来語が高いことは容易に予想されるが,上記のような書き言葉において,しかも概して荘厳な文体が好まれた近代英語期に,ここまで本来語比率が高いという事実は注目に値する.特に Milton, Johnson, Gibbon などは難解な語彙を多く用いているという印象が強いが,英語史を通じて中核的であり続けた本来語彙の底力が際立っている.一方,最高値と最低値の間の20%ほどの幅は,それぞれの著者の時代や文体の相対的な差異を浮き彫りにしてくれることも確かである.

日本語の古典文学についても同様の調査を見てみよう.宮島達夫著『古典対称語い表』に基づいた加藤ほか (68, 73) に挙げられている数値を表にまとめて示す.

| 和語 | 漢語 | 混種語 | 語彙量(異なり語数) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 万葉集(8世紀後半) | 99.6% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 6,505 |

| 竹取物語(9世紀末?10世紀初め) | 91.7% | 6.7% | 1.6% | 1,311 |

| 伊勢物語(10世紀初め?中ごろ) | 93.8% | 5.3% | 1.0% | 1,692 |

| 古今集(905年) | 99.9% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 1,994 |

| 土佐日記(935年) | 94.1% | 4.5% | 1.4% | 984 |

| 枕草子(1001年ごろ) | 84.1% | 12.2% | 3.6% | 5,247 |

| 源氏物語(11世紀初め) | 87.1% | 8.8% | 4.0% | 11,423 |

| 大鏡(12世紀初めごろ) | 67.6% | 27.6% | 4.8% | 4,819 |

| 方丈記(1212年) | 78.0% | 20.1% | 1.8% | 1,148 |

| 徒然草(1331年頃) | 68.6% | 28.1% | 3.3% | 4,242 |

和語についても,英文学史の場合と同様にグラフ化してみよう.日英語の間で通じるところが多いことに気づくだろう.

万葉集(8世紀後半) (99%): *******************************************************************************

竹取物語(9世紀末?10世紀初め) (91%): *************************************************************************

伊勢物語(10世紀初め?中ごろ) (93%): ***************************************************************************

古今集(905年) (99%): ********************************************************************************

土佐日記(935年) (94%): ***************************************************************************

枕草子(1001年ごろ) (84%): *******************************************************************

源氏物語(11世紀初め) (87%): *********************************************************************

大鏡(12世紀初めごろ) (67%): ******************************************************

方丈記(1212年) (78%): **************************************************************

徒然草(1331年頃) (68%): ******************************************************

関連して,「#1645. 現代日本語の語種分布」 ([2013-10-28-1]) とそこに張られているリンク,および「#1526. 英語と日本語の語彙史対照表」 ([2013-07-01-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

・ 加藤 彰彦,佐治 圭三,森田 良行 編 『日本語概説』 おうふう,1989年.

2014-09-06 Sat

■ #1958. Hughes の語彙星雲 [register][semantics][lexicology][purism][semantic_field]

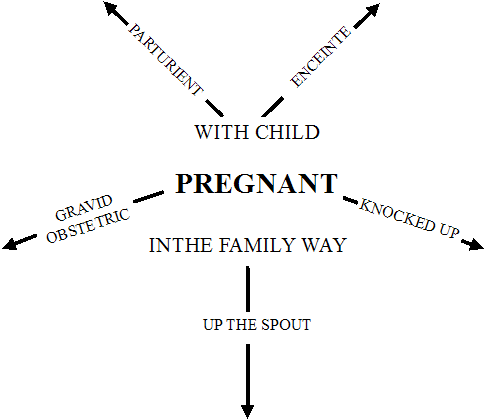

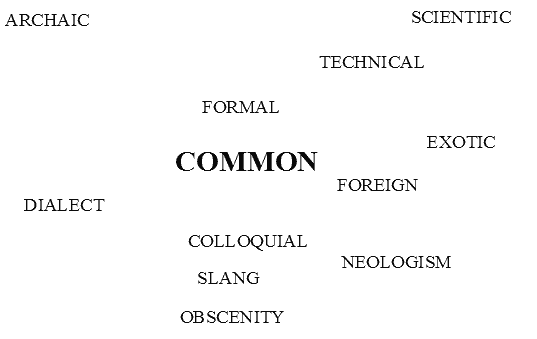

使用域 (register) による語彙と意味の広がりについて,「#611. Murray の語彙星雲」 ([2010-12-29-1]) で見た.そこで図示したように,COMMON (meaning) を中心に,LITERARY, FOREIGN, SCIENTIFIC, TECHNICAL, COLLOQUIAL, SLANG, DIALECTAL へと放射状に語彙と意味が広がっているというのが,Murray の捉え方だ.この図を具体的な語と意味で埋めてみよう.以下の図 (Hughes 5) では,「妊娠した」 (PREGNANT) という意味の場を巡って,種々の語句が然るべき位置を占めていることが示されている.

平面的に描かれがちな意味の場に使用域という次元を加え,語彙的な関係を立体的に描くことを可能とした点で,「語彙星雲」との見方は鋭い洞察だった.しかし,Hughes は語彙星雲のあり方も通時的な変化を免れることはないとし,現代英語の語彙星雲を形作るガス(使用域)は,ますます多岐に及んできていると論じた.Murray から100年たった今,別の図式が必要だと.そして,Murray の語彙星雲を次のように改良し,提示した (372) .

新しいラベルが加えられたり位置が変化したりしているが,Hughes (370--71) によれば,これは現代英語の語彙の特性を反映したものであるという.例えば,現代は借用語に対する純粋主義 (purism) が以前よりも弱まり,他言語から語彙が流入しやすくなってきたという点で,FOREIGN とは区別されるべき,取り込まれた外来要素を示すラベル EXOTIC が必要だろう(ただし,現代英語で全体的に語彙借用が減ってきていることについて,「#879. Algeo の新語ソース調査から示唆される通時的傾向」([2011-09-23-1]) を参照).また,SCIENTIFIC と TECHNICAL の語彙の増大や役割の変化に伴って,両者の位置関係についても再考が必要かもしれない.上記4ラベルが ARCHAIC とともに中心から離れた周辺に位置しているのは,これらの語彙の不透明さを反映している.さらに,現代はLITERARY というラベルの守備範囲が曖昧になってきていることから,そのラベルはなしとし,部分的に FORMAL, ARCHAIC, 場合によっては COLLOQUIAL, SLANG, OBSCENITY その他のラベルで補うのが妥当かもしれない.

この図に反映されていないものとして,他変種からの語彙がある.例えば,イギリス英語の語彙を念頭におくとき,そのなかに多く入り込んでくるようになったアメリカ英語の語彙 (americanism) やその他の変種の語彙はどのように位置づけられるだろうか.FOREIGN や EXOTIC とも違うし,伝統的な地域方言が念頭にある DIALECT とも異なる.

語彙構造も意味構造も時代とともに変化する.現代英語もその例に漏れない.現代英語でも,使用域として貼り付けるラベル,そして語彙星雲の図式が,再考を迫られている.

・Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-09-04 Thu

■ #1956. Hughes の英語史略年表 [timeline][lexicology][lexicography][register][slang][hel][historiography]

Hughes (xvii--viii) は,著書 A History of English Words で,語彙史と辞書史を念頭に置いた,外面史を重視した英語史年表を与えている.略年表ではあるが,とりわけ語彙史,辞書との関連が前面に押し出されている点で,著者の狙いが透けて見える年表である.

| 410 | Departure of the Roman legions |

| c.449 | The Invasion of the Angles, Saxons, Jutes and Frisians |

| 597 | The Coming of Christianity |

| 731 | Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People |

| 787 | The first recorded Scandinavian raids |

| 871--99 | Alfred King of Wessex |

| 900--1000 | Approximate date of Anglo-Saxon poetry collections |

| 1016--42 | Canute King of England, Scotland and Denmark |

| 1066 | The Norman Conquest |

| c.1150 | Earliest Middle English texts |

| 1204 | Loss of Calais |

| 1362 | English restored as language of Parliament and the law |

| 1370--1400 | The works of Chaucer, Langland and the Gawain poet |

| 1384 | Wycliffite translation of the Bible |

| 1476 | Caxton sets up his press at Westminster |

| 1525 | Tyndale's translation of the Bible |

| 1549 | The Book of Common Prayer |

| 1552 | Early canting dictionaries |

| 1584 | Roanoke settlement of America (abortive) |

| 1590--16610 | Shakespeare's main creative period |

| 1603 | Act of Union between England and Scotland |

| 1604 | Robert Cawdrey's Table Alphabeticall |

| 1607 | Jamestown settlement in America |

| 1609 | English settlement of Jamaica |

| 1611 | Authorized Version of the Bible |

| 1619 | First Arrival of slaves in America |

| 1620 | Arrival of Pilgrim fathers in America |

| 1623 | Shakespeare's First Folio published |

| 1649--60 | Puritan Commonwealth: closure of the theatres |

| 1660 | Restoration of the monarchy |

| 1667 | Milton's Paradise Lost |

| 1721 | Nathaniel Bailey's Universal Etymological English Dictionary |

| 1755 | Samuel Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language |

| 1762--94 | Grammars published by Lowth, Murray, etc. |

| 1765 | Beginning of the English Raj in India |

| 1776 | Declaration of American Independence |

| 1788 | Establishment of the first penal colony in Australia |

| 1828 | Noah Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language |

| 1884--1928 | Publication of the Oxford English Dictionary |

| 1903 | Daily Mirror published as the first tabloid |

| 1922 | Establishment of the BBC |

| 1947 | Independence of India |

| 1957--72 | Independence of various African, Asian and Caribbean states |

| 1961 | Third edition of Webster's Dictionary |

| 1968 | Abolition of the post of Lord Chancellor |

| 1989 | Second edition of the Oxford English Dictionary |

著書を読んだ後に振り返ると,著者の英語史記述に対する姿勢,英語史観がよくわかる.年表というのは1つの歴史観の表現であるなと,つくづく思う.これまで timeline の各記事で,英語史という同一対象に対して異なる年表を飽きもせずに掲げてきたのは,その作者の英語史観を探りたいがためだった.いろいろな年表を眺めてみてください.

・Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-07-19 Sat

■ #1909. 女性を表わす語の意味の悪化 (2) [semantic_change][gender][lexicology][semantics][euphemism][taboo][sapir-whorf_hypothesis]

昨日の記事「#1908. 女性を表わす語の意味の悪化 (1)」 ([2014-07-18-1]) で,英語史を通じて見られる semantic pejoration の一大語群を見た.英語史的には,女性を表わす語の意味の悪化は明らかな傾向であり,その背後には何らかの動機づけがあると考えられる.では,どのような動機づけがあるのだろうか.

1つは,とりわけ「売春婦」を指示する婉曲的な語句 (euphemism) の需要が常に存在したという事情がある.売春婦を意味する語は一種の taboo であり,間接的にやんわりとその指示対象を指示することのできる別の語を常に要求する.ある語に一度ネガティヴな含意がまとわりついてしまうと,それを取り払うのは難しいため,話者は手垢のついていない別の語を用いて指示することを選ぶのである.その方法は,「#469. euphemism の作り方」 ([2010-08-09-1]) でみたように様々あるが,既存の語を取り上げて,その意味を転換(下落)させてしまうというのが簡便なやり方の1つである.日本語の「風俗」「夜鷹」もこの類いである.関連して,女性の下着を表わす語の euphemism について「#908. bra, panties, nightie」 ([2011-10-22-1]) を参照されたい.

しかし,Schulz の主張によれば,最大の動機づけは,男性による女性への偏見,要するに女性蔑視の観念であるという.では,なぜ男性が女性を蔑視するかというと,それは男性が女性を恐れているからだという.恐怖の対象である女性の価値を社会的に(そして言語的にも)下げることによって,男性は恐怖から逃れようとしているのだ,と.さらに,なぜ男性は女性を恐れているのかといえば,根源は男性の "fear of sexual inadequacy" にある,と続く.Schulz (89) は複数の論者に依拠しながら,次のように述べる.

A woman knows the truth about his potency; he cannot lie to her. Yet her own performance remains a secret, a mystery to him. Thus, man's fear of woman is basically sexual, which is perhaps the reason why so many of the derogatory terms for women take on sexual connotations.

うーむ,これは恐ろしい.純粋に歴史言語学的な関心からこの意味変化の話題を取り上げたのだが,こんな議論になってくるとは.最初に予想していたよりもずっと学際的なトピックになり得るらしい.認識の言語への反映という観点からは,サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) にも関わってきそうだ.

・ Schulz, Muriel. "The Semantic Derogation of Woman." Language and Sex: Difference and Dominance. Ed. Barrie Thorne and Nancy Henley. Rowley, MA: Newbury House, 1975. 64--75.

2014-07-18 Fri

■ #1908. 女性を表わす語の意味の悪化 (1) [semantic_change][gender][lexicology][semantics]

「#473. 意味変化の典型的なパターン」 ([2010-08-13-1]) の (3) で示した意味の悪化 (pejoration) は,英語史において例が多い.良い意味,あるいは少なくとも中立的な意味だった語にネガティヴな価値が付される現象である.これまでの記事としては,「#505. silly の意味変化」 ([2010-09-14-1]),「#683. semantic prosody と性悪説」 ([2011-03-11-1] ),「#742. amusing, awful, and artificial」 ([2011-05-09-1]) などで具体例を見てきた.

しかし,英語史における意味の悪化の例としてとりわけよく知られているのは,女性を表わす語彙だろう.英語史を通じて,「女性」を意味する語群は,軒並み侮蔑的な含蓄的意味 (connotation) を獲得していく傾向を示す.「女性」→「性的にだらしない女性」→「娼婦」というのが典型的なパターンである.この話題を正面から扱った Schulz の論文 "The Semantic Derogation of Woman" によると,「女性を表わす語の堕落」がいかに一般的な現象であるかが,これでもかと言わんばかりに示される.3箇所から引用しよう.

Again and again in the history of the language, one finds that a perfectly innocent term designating a girl or woman may begin with totally neutral or even positive connotations, but that gradually it acquires negative implications, at first perhaps only slightly disparaging, but after a period of time becoming abusive and ending as a sexual slur. (82--83)

. . . virtually every originally neutral word for women has at some point in its existence acquired debased connotations or obscene reference, or both. (83)

I have located roughly a thousand words and phrases describing women in sexually derogatory ways. There is nothing approaching this multitude for describing men. Farmer and Henley (1965), for example, have over five hundred terms (in English alone) which are synonyms for prostitute. They have only sixty-five synonyms for whoremonger. (89)

Schulz の論文内には,数多くの例が列挙されている.論文内に現われる99語をアルファベット順に並べてみた.すべてが「性的に堕落した女」「娼婦」にまで意味が悪化したわけではないが,英語史のなかで少なくともある時期に侮蔑的な含意をもって女性を指示し得た単語群である.

abbess, academician, aunt, bag, bat, bawd, beldam, biddy, Biddy, bitch, broad, broadtail, carrion, cat, cleaver, cocktail, courtesan, cousin, cow, crone, dame, daughter, doll, Dolly, dolly, dowager, drab, drap, female, flagger, floozie, frump, game, Gill, girl, governess, guttersnipe, hack, hackney, hag, harlot, harridan, heifer, hussy, jade, jay, Jill, Jude, Jug, Kitty, kitty, lady, laundress, Madam, minx, Miss, Mistress, moonlighter, Mopsy, mother, mutton, natural, needlewoman, niece, nun, nymph, nymphet, omnibus, peach, pig, pinchprick, pirate, plover, Polly, princess, professional, Pug, quean, sister, slattern, slut, sow, spinster, squaw, sweetheart, tail trader, Tart, tickletail, tit, tramp, trollop, trot, twofer, underwear, warhorse, wench, whore, wife, witch

重要なのは,これらに対応する男性を表わす語群は必ずしも意味の悪化を被っていないことだ.spinster (独身女性)に対する bachelor (独身男性),witch (魔女)に対する warlock (男の魔法使い)はネガティヴな含意はないし,どちらかというとポジティヴな評価を付されている.老女性を表わす trot, heifer などは侮蔑的だが,老男性を表わす geezer, codger は少々侮蔑的だとしてもその度合いは小さい.queen (女王)は quean (あばずれ女)と通じ,Byron は "the Queen of queans" などと言葉遊びをしているが,対する king (王)には侮蔑の含意はない.princess と prince も同様に対照的だ.mother, sister, aunt, niece の意味は堕落したことがあったが,対応する father, brother, uncle, nephew にはその気味はない.男性の職業・役割を表わす footman, yeoman, squire は意味の下落を免れるが,abbess, hussy, needlewoman など女性の職業・役割の多くは professional その語が示しているように,容易に「夜の職業」へと転化してゆく.若い男性を表わす語は boy, youth, stripling, lad, fellow, puppy, whelp など中立的だが,doll, girl, nymph は侮蔑的となる.

女性を表わす固有名詞も,しばしば意味の悪化の対象となる.また,男性と女性の両者を指示することができる dog, pig, pirate などの語でも,女性を指示する場合には,ネガティヴな意味が付されるものも少なくない.いやはや,随分と類義語を生み出してきたものである.

・ Schulz, Muriel. "The Semantic Derogation of Woman." Language and Sex: Difference and Dominance. Ed. Barrie Thorne and Nancy Henley. Rowley, MA: Newbury House, 1975. 64--75.

2014-07-06 Sun

■ #1896. 日本語に入った西洋語 [loan_word][borrowing][japanese][lexicology][borrowing][portuguese][spanish][dutch][italian][russian][german][french]

日本語に西洋語が初めて持ち込まれたのは,16世紀半ばである.「#1879. 日本語におけるローマ字の歴史」 ([2014-06-19-1]) でも触れたように,ポルトガル人の渡来が契機だった.キリスト教用語とともに一般的な用語ももたらされたが,前者は後に禁教となったこともあって定着しなかった.後者では,アルヘイトウ(有平糖)(alfeloa) ,カステラ (Castella),カッパ (capa),カボチャ(南瓜,Cambodia),カルサン(軽袗,calsãn),カルタ (carta),コンペイトウ(金平糖,confeitos),サラサ(更紗,saraça),ザボン (zamboa),シャボン (sabão),ジバン(襦袢,gibão),タバコ(煙草,tabaco),チャルメラ (charamela),トタン (tutanaga),パン (pão),ビイドロ (vidro),ビスカット(ビスケット,biscoito),ビロード (veludo),フラスコ (frasco),ブランコ (blanço),ボオロ (bolo),ボタン (botão) などが残った.16世紀末にはスペイン語も入ってきたが,定着したものはメリヤス (medias) ぐらいだった.

近世中期に蘭学が起こると,オランダ語の借用語が流れ込んでくる.自然科学の語彙が多く,後に軍事関係の語彙も入った.まず,医学・薬学では,エーテル (ether),エキス (extract),オブラート (oblaat),カルシウム (calcium),カンフル (kamfer, kampher),コレラ (cholera),ジギタリス (digitalis),スポイト (spuit),ペスト (pest),メス (mes),モルヒネ (morphine).化学・物理・天文では,アルカリ (alkali),アルコール (alcohol),エレキテル (electriciteit),コンパス (kompas),ソーダ (soda),テレスコープ (telescoop),ピント (brandpunt),レンズ (lenz).生活関係では,オルゴール (orgel),ギヤマン (diamant),コーヒ (koffij),コック (kok),コップ(kop; cf. 「#1027. コップとカップ」 ([2012-02-18-1])),ゴム (gom),シロップ (siroop),スコップ (schop),ズック (doek),ソップ(スープ,soep),チョッキ (jak),ビール (bier),ブリキ (blik),ペン (pen),ペンキ (pek), ポンプ (pomp),ホック (hoek),ホップ (hop),ランプ (lamp).軍事関係では,サーベル (sabel),ピストル (pistool),ランドセル (ransel).

明治時代には西洋語のなかでは英語が優勢となってくるが,明治初期にはいまだ「コップ」「ドクトル」などオランダ借用語の使用が幅を利かせていた.しかし,大正中期以降は英語系が大半を占めるようになり,オランダ風の「ソップ」が英語風の「スープ」へ置換されたように,発音も英語風へと統一されてくる.英語以外の西洋語としては,大正から昭和にかけてドイツ語(主に医学,登山,哲学関係),フランス語(主に芸術,服飾,料理関係),イタリア語(主に音楽関係),ロシア語も見られるようになった.それぞれの例を挙げてみよう.

・ ドイツ語:ノイローゼ(Neurose),カルテ(Karte),ガーゼ(Gaze),カプセル(Kapsel),ワクチン(Vakzin),イデオロギー(Ideologie),ゼミナール(Seminar),テーマ(Thema),テーゼ(These),リュックサック(Rucksack),ザイル(Seil),ヒュッテ(Hütte),オブラート (Oblate), クレオソート (Kreosot).

・ フランス語:デッサン(dessin),コンクール(concours),シャンソン(chanson),ロマン(roman),エスプリ(esprit),ジャンル(genre),アトリエ(atelier),クレヨン(crayon),ルージュ(rouge),ネグリジェ(néglige),オムレツ(omelette),コニャック(cognac),シャンパン(champagne),マヨネーズ(mayonnaise)

・ イタリア語:オペラ(opera),ソナタ(sonata),テンポ(tempo),フィナーレ(finale),マカロニ(macaroni),スパゲッティ(spaghetti)

・ ロシア語:ウォッカ(vodka),カンパ(kampaniya),ペチカ(pechka),ノルマ(norma)

今日,西洋語の8割が英語系であり,借用の対象となる英語の変種としては太平洋戦争をはさんで英から米へと切り替わった.

以上,佐藤 (179--80, 185--86) および加藤他 (74) を参照して執筆した.関連して,「#1645. 現代日本語の語種分布」 ([2013-10-28-1]),「#1526. 英語と日本語の語彙史対照表」 ([2013-07-01-1]),「#1067. 初期近代英語と現代日本語の語彙借用」 ([2012-03-29-1]) の記事も参照されたい.

・ 佐藤 武義 編著 『概説 日本語の歴史』 朝倉書店,1995年.

・ 加藤 彰彦,佐治 圭三,森田 良行 編 『日本語概説』 おうふう,1989年.

2014-06-21 Sat

■ #1881. 接尾辞 -ee の起源と発展 (2) [suffix][pde_language_change][lexicology][statistics][oed][productivity][agentive_suffix]

昨日の記事「#1880. 接尾辞 -ee の起源と発展 (1)」 ([2014-06-20-1]) に続き,当該接尾辞の現代英語にかけての質的な変化および量的な発展について,Isozaki に拠りながら考える.

Isozaki は,OED ほかの参考資料に当たり,現代英語から500を超える -ee 語を収集した.そして,これらを初出年代,統語・意味の種別,語幹の語源により分析し,後期近代英語から現代英語にかけての潮流を2点突き止めた.昨日の記事の終わりで述べた,(1) ロマンス系語幹ではなく本来語幹に接続する傾向が生じてきていること,および (2) standee のような動作主(主語)タイプが増えてきていること,の2つである.

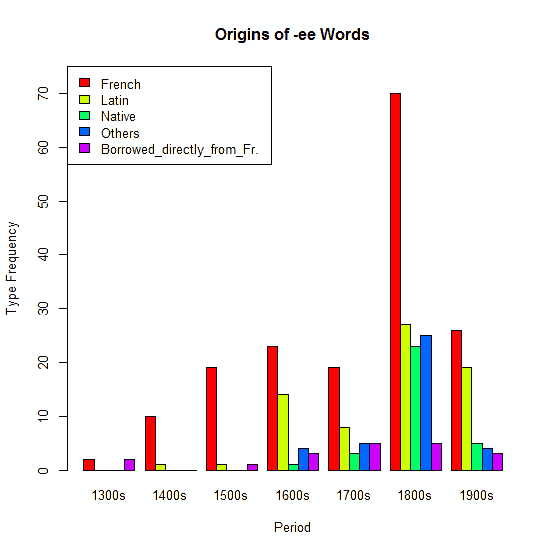

(1) については,OED を用いた調査結果をグラフ化すると以下のようになる (Isozaki 7) .

フランス語幹に接続する傾向が一貫して強いことは明らかである.しかし,本来語幹に接続する語例が後期近代より現われてきたことは注目に値する.なお,19世紀の爆発期の後で20世紀が地味に見えるのは,OED の語彙収録の特徴によるところが大きいかもしれない.

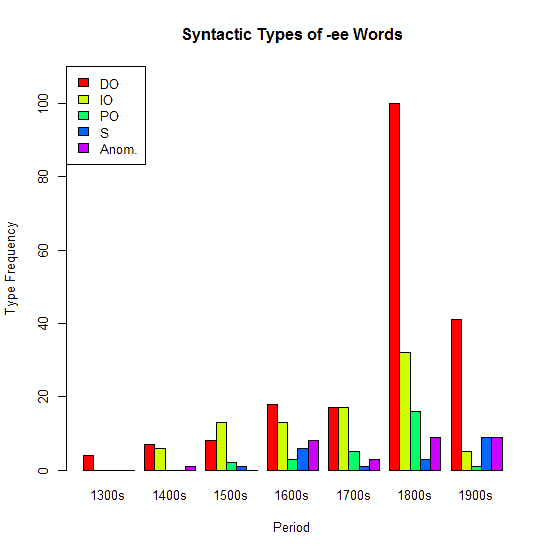

次に (2) についてだが,同じく OED を用いて,統語(意味)的な観点から分類した結果は以下の通りである (Isozaki 6) .グラフのなかで,DO は動詞の直接目的語,IO は間接目的語,PO は前置詞目的語,S は主語,Anom. は動詞とは直接に関係しない変則的なものである.

従来型の DO タイプが常に優勢であり続けていることが顕著であり,S タイプの拡張は特に目立たないようにみえる.しかし,OED を離れて,1900--2005年の種々の本や参考図書での出現を考慮に入れると,DO が117例,IO が23例,PO が4例,S が32例,Anom. が18例と,S (主語タイプ)の伸張が示唆される (Isozaki 6) .

-ee 語は臨時語的な使われ方が多いと想像され,使用域の一般化も進んでいるように思われる.今後は語用論的な調査も必要となってくるかもしれない.接辞の生産性 (productivity) という観点からも,アンテナを張っておきたい話題である.

・ Isozaki, Satoko. "520 -ee Words in English." Lexicon 36 (2006): 3--23.

2014-06-09 Mon

■ #1869. 日本語における仏教語彙 [japanese][kanji][loan_word][religion][buddhism][lexicology]

宗教の伝来が受け入れ側の言語に著しい影響を及ぼすことについて,「#296. 外来宗教が英語と日本語に与えた言語的影響」 ([2010-02-17-1]) で取り上げた.その記事では,日英において顕著な類似点があることを指摘した.ユーラシア大陸の両端で,時をほぼ同じくする6世紀という時期に,それぞれ大陸から仏教とキリスト教が伝わった.各々,漢字とローマ字を受容して本格的な文字文化が始まり,その宗教と関連した種々の文物や語彙が流入した.新宗教は乗り物として機能しており,語彙はそれに乗って,日本とイングランドへ到着したのである.

キリスト教が英語に与えた語彙上の影響については,「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1]) や「#1439. 聖書に由来する表現集」 ([2013-04-05-1]) で触れ,日英の語彙史の比較対照は「#1526. 英語と日本語の語彙史対照表」 ([2013-07-01-1]) や「#1049. 英語の多重語と漢字の異なる字音」 ([2012-03-11-1]) で言及した.今回は,日本語における仏教語の受容について取り上げる.以下,『日本語学研究事典』 (407--08) を参照して記す.

6世紀半ばに仏教が伝来すると,以降,多くの仏教語(あるいは仏語)が日本語へ流入した.聖徳太子以後,仏教を振興した上代には「香炉」「蝋燭」「脇息」「高座」「功徳」「供養」などが入り,天台・真言の二宗の栄えた中古には「大徳」「修法」「念誦」「新発意」「持仏」「名号」「数珠」「加持」「精進」「彼岸」「布施」「回向」「出家」,また「道理」「本意」「世界」「世間」「孝養」「懈怠」「道心」「変化」「稀有」「愛敬」「執念」などが見られた.中古から中世にかけては,信仰がいっそう深まり,仏教説話も多く現われ,「諸行無常」「盛者必衰」「煩悩」「衆生」「修行」「三界」「智慧」「過去」,また「発心」「悲願」「勧進」「微塵」「安穏」など300語以上が借用されている.中世から近世にかけては,臨済・曹洞などの禅宗の伝来とともに使用の拡がった「挨拶」「以心伝心」「向上」「到底」「到頭」「端的」「滅却」「毛頭」「行脚」「看経」に加え,「一得一失」「主眼」「自粛」「体得」「打開」「単刀直入」「門外漢」「老婆心」のように日常化したものも多い.また,インドの経論が漢文に音訳された,いわゆる梵語も「閼伽」「伽藍」「娑婆」「卒塔婆」「荼毘」「檀那」のように日本語へ入ってきている.

仏教語はその他多数あるが,以下に『学研 日本語「語源」辞典』に挙げられている仏教語・梵語に由来することばを列挙しよう.借用された時期はまちまちだが,仏教が日本語の語彙や表現に与えてきた影響の甚大さが知られる.

愛敬〔あいきょう〕,挨拶〔あいさつ〕,愛着〔あいちゃく〕,阿吽〔あうん〕,閼伽〔あか〕,悪魔〔あくま〕,阿修羅〔あしゅら〕,痘痕〔あばた〕,尼〔あま〕,行脚〔あんぎゃ〕,安心〔あんしん〕,意識〔いしき〕,以心伝心〔いしんでんしん〕,一大事〔いちだいじ〕,一念発起〔いちねんほっき〕,一蓮托生〔いちれんたくしょう〕,衣鉢〔いはつ〕,因果〔いんが〕,因業〔いんごう〕,引導〔いんどう〕,因縁〔いんねん〕,有為転変〔ういてんぺん〕,有象無象〔うぞうむぞう〕,有頂天〔うちょうてん〕,優曇華〔うどんげ〕,優婆夷・優婆塞〔うばい・うばそく〕,盂蘭盆〔うらぼん〕,雲水〔うんすい〕,会釈〔えしゃく〕,縁起〔えんぎ〕,往生〔おうじょう〕,応用〔おうよう〕,お題目〔おだいもく〕,億劫〔おっくう〕,餓鬼〔がき〕,加持祈祷〔かじきとう〕,呵責〔かしゃく〕,火宅〔かたく〕,我慢〔がまん〕,空念仏〔からねんぶつ〕,伽藍〔がらん〕,迦陵頻伽〔かりょうびんが〕,瓦〔かわら〕,観念〔かんねん〕,甘露〔かんろ〕,伽羅〔きゃら〕,経木〔きょうぎ〕,行住坐臥〔ぎょうじゅうざが〕,苦界〔くがい〕,愚痴〔ぐち〕,功徳〔くどく〕,供養〔くよう〕,庫裏〔くり〕,紅蓮〔ぐれん〕,怪訝〔けげん〕,袈裟〔けさ〕,解脱〔げだつ〕,外道〔げどう〕,玄関〔げんかん〕,香典〔こうでん〕,虚仮〔こけ〕,居士〔こじ〕,後生〔ごしょう〕,乞食〔こつじき〕,御来迎〔ごらいごう〕,御利益〔ごりやく〕,権化〔ごんげ〕,言語道断〔ごんごどうだん〕,金輪際〔こんりんざい〕,散華〔さんげ〕,懺悔〔ざんげ〕,三途の川〔さんずのかわ〕,三昧〔さんまい〕,四苦八苦〔しくはっく〕,獅子身中の虫〔しししんちゅうのむし〕,竹篦返し〔しっぺがえし〕,七宝〔しっぽう〕,慈悲〔じひ〕,娑婆〔しゃば〕,舎利〔しゃり〕,出世〔しゅっせ〕,修羅〔しゅら〕,精進〔しょうじん〕,正念場〔しょうねんば〕,所詮〔しょせん〕,新発意〔しんぼち〕,随喜〔ずいき〕,頭陀袋〔ずだぶくろ〕,世間〔せけん〕,世知〔せち〕,殺生〔せっしょう〕,雪隠〔せっちん〕,刹那〔せつな〕,専念〔せんねん〕,禅問答〔ぜんもんどう〕,相好〔そうごう〕,息災〔そくさい〕,作麼生〔そもさん〕,醍醐味〔だいごみ〕,大衆〔たいしゅう〕,荼毘〔だび〕,他力本願〔たりきほんがん〕,旦那〔だんな〕,断末魔〔だんまつま〕,知恵〔ちえ〕,長広舌〔ちょうこうぜつ〕,長者〔ちょうじゃ〕,爪弾き〔つまはじき〕,道具〔どうぐ〕,堂堂巡り〔どうどうめぐり〕,道楽〔どうらく〕,内緒〔ないしょ〕,南無三〔なむさん〕,奈落〔ならく〕,涅槃〔ねはん〕,拈華微笑〔ねんげみしょう〕,暖簾〔のれん〕,馬鹿〔ばか〕,彼岸〔ひがん〕,比丘・比丘尼〔びく・びくに〕,非業〔ひごう〕,火の車〔ひのくるま〕,不思議〔ふしぎ〕,普請〔ふしん〕,布施〔ふせ〕,分別〔ふんべつ〕,法師〔ほうし〕,坊主〔ぼうず〕,方便〔ほうべん〕,菩提〔ぼだい〕,法螺〔ほら〕,煩悩〔ぼんのう〕,摩訶不思議〔まかふしぎ〕,魔羅〔まら〕,曼荼羅〔まんだら〕,満遍なく〔まんべんなく〕,微塵〔みじん〕,未曾有〔みぞう〕,冥利〔みょうり〕,未来〔みらい〕,無垢〔むく〕,無残〔むざん〕,無常〔むじょう〕,無尽蔵〔むじんぞう〕,冥土〔めいど〕,滅相もない〔めっそうもない〕,滅法〔めっぽう〕,妄想〔もうそう〕,野狐禅〔やこぜん〕,夜叉〔やしゃ〕,唯我独尊〔ゆいがどくそん〕,遊山〔ゆさん〕,律儀〔りちぎ〕,輪廻〔りんね〕,流転〔るてん〕,瑠璃〔るり〕,老婆心〔ろうばしん〕,渡りに船〔わたりにふね〕

上述のとおり,日本では仏教が国民生活に深く浸透したために,仏教語は日本語語彙に広く見られるだけでなく,転義を生じて俗語となったものも多い.英語側でも同様に,「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1]) や「#1439. 聖書に由来する表現集」 ([2013-04-05-1]) の語彙・表現リストに見られるように,当初はキリスト教の専門用語として始まったものの,後に専門的な響きを弱め,使用域 (register) を拡げた語 (ex. candle, master, noon, school, verse) も少なくない.この点でも,日英両言語において宗教伝来と語彙史の関連を比較対照することは意義深い.

・ 『日本語学研究事典』 飛田 良文ほか 編,明治書院,2007年.

2014-04-01 Tue

■ #1800. 様々な反対語 [semantics][markedness][antonymy][lexicology]

反対語 (opposite) には反意語,反義語などの呼び名があるが,用語の不安定さもさることながら,何をもって反対とするかについての理解も様々である.

黒の反対は白か,しかし白の反対は紅(赤)とも考えられるのではないか.だが『赤と黒』という組み合わせもあるし,信号機を思い浮かべれば赤と青(実際の色は緑)という対立も考え得る.また「高い」の反対には「低い」と「安い」の2つがあるが,「低い」の反対には「高い」1つしかない.兄の反対は弟か,あるいは姉か,はたまた妹か.犬に対する猫,タコに対するイカは反対語といえるのか.happy の反対は unhappy か,それとも sad か.長いと短い,生と死,山と海,北と南,夫と妻は,それぞれ同じ基準によって反対語と呼べるのだろうか.

意味論では,反対語にも様々な種類があることが認められている.以下に Hofmann (40--46, 57--60) に拠って,代表的なものをまとめよう.

(1) (gradable) antonym

最も典型的な反対語は,high / low,long / short, old / new, hot / cold のような程度を表わす形容詞の対である.これらの反対語形容詞は,英語でいえば比較級や最上級にできる,very で程度を強められるなどの特徴をもつ.程度を尋ねる疑問や名詞形に使用されるのは,対のうちいずれかであり,そちらが一時的に中立的な意味を担うことになる.例えば,long / short の対に関しては long が無標となり,How long is the train? や the length of the train などと中和した意味で用いられる.日本語でも「どのくらい長いのか」と尋ねるし,名詞は「長さ」という.漢字では「長短」「大小」「寒暖」などと対にして中立的な程度を表わすことができるのがおもしろい.

(2) complementary

on / off,true / false, finite / infinite, mortal / immortal, single / married などの二律背反の対を構成する.(1) の対と異なり,very などで強めることはできず,程度として表現できないデジタルな関係である.一般的に,否定の接頭辞が付加されている場合を除いて,どちらが無標であるかを決めることができない.ただし,対の一方が (1) の性質をもち,他方が (2)の性質をもつケースもある.例えば,open / shut, cooked / raw, invisible / visible は,それぞれのペアのうち前者は gradable である.

他の品詞では,male / female, stop / move などが挙げられる.

(3) antonymous group

black / white / red / blue / green のように,「反対」となりうるものが集まって一連の語群(この場合には色彩語彙)を形成するもの.これらは反対語というよりは,むしろ同じ語群に属するという意味では類義語とも言うべきである.互いに同類でありながらも,その属の内部では固有の地位を占めており互いに差異的であるという点で,見方によっては「反対語」ともされるにすぎない.dog と cat はそれぞれ同類でありながら,同属の内部で相互に異なっているので,antonymous group の一部をなしているといえる.犬と猫は日本語でも英語でも慣用的にペアをなすので対語と見なされるが,同じグループの構成員としては,鼠,豚,狐,鹿を含めた多くの動物を挙げることができる.形容詞の例としては,big / small であれば (1) の例と同様にみえるが,huge / big / small / tiny という4段階制のなかで考えれば (3) を問題にしていることがわかる.つまり,(3) は,(1) や (2) の2項対立とは異なり,複数項対立と言い換えてもよいだろう.north / south / east / west の4項目など,方向に関して内部構造をもっているようなグループもある.

日本語で山の反対は海(あるいは川?)が普通だが,アメリカでは mountain に対しては valley が普通である.このように,グルーピングに文化的影響が見られるものも多い.

(4) reversative

動詞の動作について,逆転関係を表わす.tie (結ぶ)と untie (ほどく),clothe (着せる)と unclothe (脱がせる)など.過去分詞形容詞にして tied / untied, clothed / unclothed の対立へ転化すると,(1) や (2) の例となる.appear / disappear, enable / disable も同様.

(5) converse

husband / wife, parent / child のような相互に逆方向でありながら補い合う関係."X is the (husband) of Y." のとき,"Y is the (wife) of X." が成り立つ.だが,son / father は上の言い換えが必ずしもできないので,見せかけの converse である (ex. "X is the father of Liz") .

性質は異なるが,buy / sell, lend / borrow のように単一の出来事を反対の観点で見るものや,above / below, in front of / behind, north of / south of, right / left のように空間的位置関係を表わすものも,converse といえる.

上記のようにきれいに分類できないような「反対語」もあるはずだが,一応の区分として参考になるだろう.

・ Hofmann, Th. R. Realms of Meaning. Harlow: Longman, 1993.

2014-03-26 Wed

■ #1794. 借用はなぜ起こるか (2) [borrowing][lexicology][loan_word][typology]

「#46. 借用はなぜ起こるか」 ([2009-06-13-1]) の記事で,語彙が他言語から借用される理由を考えた.しかし,この「なぜ」は究極の問いであり,本格的に追究するのであれば,先に他の4W1Hの問いから潰していかなければならない.why の前に,what, who, when, where, how を問う必要があるということだ.そこで borrowing の記事を中心に,本ブログでも様々なアプローチを採ってきた.

借用語の「なぜ」に迫る論考としては,Hans Käsmann (Studien zum kirchlichen Wortschatz des Mittelenglischen 1100--1350. Eng Beitrag zum Problem der Sprachmischung. Tübingen, 1961.) に拠った Görlach (149--50) のものがあるので紹介しよう."causes and situations favouring the transfer" として,次のような分類表を掲げている(語例の前の "A11" などは.Görlach のテキスト参照記号).

(A) Gaps in the indigenous lexis

1. The word is taken over together with the new content and the new object: A11 myrre, D31 senep, F21 sabat, synagoge.

2. A well-known content has no word to designate it: D32 plant

3. Existing expressions are insufficient to render specific nuances ('misericordia', see blow).

(B) Previous weakening of the indigenous lexis

4. The content had been experimentally rendered by a number of unsatisfactory expressions: E15 leorningcniht||disciple.

5. The content had been rendered by a word weakened by homonymy, polysemy, or being part of an obsolescent type of word-formation: C24 hilid||covered; C25 hǣlan = heal, save; H11 hǣlend||sauyoure.

6. An expression which is connotationally loaded needs to be replaced by a neutral expression.

(C) Associative relations

7. A word is borrowed after a word of the same family has been adopted: D49 iust (after justice; cf. judge n., v., judgement).

8. The borrowing is supported by a native word of similar form: læccan × catchen; the process was particularly important with adoptions from Scandinavian.

9. 'Corrections': an earlier loanword is adapted in form/replaced by a new loanword: F2 engel||aungel.

(D) Special extralinguistic conditions

10. Borrowing of words needed for rhymes and metre.

11. Adoptions not motivated by necessity but by fashion and prestige.

12. Words left untranslated because the translator was incompetent, lazy or anxious to stay close to his source: H10 euangelise EV.

There remain a large number of uncertain classifications, most of these somehow connected with 11), a category which is very difficult to define.

(A), (B), (C) はまとめて,既存の語彙体系から生じる借用への圧力ということができるだろうか.「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]) でみたタイポロジーとも交差する.(D) はおよそ言語外的な要因というべきものである.通常,語の借用を話題にする場合には,言語外的な要因が注目されることも多いが,この分類は相対的にその扱いが弱いのが特徴だ.結局のところ,最後に但し書きで逃げ口上を打っているように,このような分類を立てることに限界があるのだろう.Fischer (105) は,この分類に不満を表明している.

Like all attempts to "explain" language change, this one suffers from the fact that explanations can only be guessed at and that actual, verifiable proof is hard to come by. Any such typology, therefore, will remain tentative.

冒頭で述べたように,まずは借用の4W1Hを着実に理解してゆくところから始める必要がある.

・ Görlach, Manfred. The Linguistic History of English. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997.

・ Fischer, Andreas. "Lexical Borrowing and the History of English: A Typology of Typologies." Language Contact in the History of English. 2nd rev. ed. Ed. Dieter Kastovsky and Arthur Mettingers. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2003. 97--115.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow