2025-10-06 Mon

■ #6006. 声の書評 --- khelf 木原桃子さんが紹介する『英語文化史を知るための15章』 [khelf][hellive2025][review][voice_review][kenkyusha][heldio][voicy][manuscript][beowulf]

この秋,khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)のメンバーによる hel活 (helkatsu) が活発化してきています.昨日狼煙を上げた heldio での「声の書評」シリーズも,khelf による企画です,今回は khelf 副会長の木原桃子さんにご登場願い,武内信一(著)『英語文化史を知るための15章』(研究社,2009年)を紹介してもらいました.著者は,木原さんの青山学院大学時代の恩師でもあります.ぜひ今朝の heldio 配信回「#1590. 声の書評 by khelf 木原桃子さん --- 武内信一(著)『英語文化史を知るための15章』(研究社,2009年)」をお聴きいただければ.

木原さんは,本書の魅力として,語彙や文法といった英語の内面史を追うだけでなく,その言語が使われている社会や文化と関連づけた英語の外面史,すなわち「英語文化史」を重視する視点を的確に指摘してくれました.単なる「英語史」ではなく「英語文化史」と冠した本書は,その格好の入門書であると.私も本書を最初に読んだとき,同じ印象をもったことを覚えています.

本書は15の章からなり,それぞれがベオウルフ,英語聖書,シェイクスピア,ジョンソンの辞書,OED といった独立したテーマを扱っているため,どこからでも読み進められます.「英語文化史」を鳥瞰的に見渡せる構成は,特にこれから英語史を学ぶ高校生や大学生にとって,興味の入り口を見つけるのに最適だと思います.

木原さんは,武内先生ご自身が写本を作成していることを紹介しつつ,先生の運営されている MANUSCRIPT CHOUMEIAN にも触れています.Beowulf と『平家物語』の意外な関係が論じられている章については,木原さんはこの章を読んで英語史の魅力に目覚めたとのことです.体験に裏打ちされた言葉には説得力がありました.

khelf メンバーが自身の言葉で書籍を紹介してくれるのは,とても嬉しいことです.「声の書評」が,多くの方にとって新たな本との出会いの場となることを期待しています.皆さん,ぜひ本書を手に取ってみてください.

・ 武内 信一 『英語文化史を知るための15章』 研究社,2009年.

2024-11-30 Sat

■ #5696. royal we の古英語からの例? [oe][me][royal_we][monarch][personal_pronoun][pronoun][beowulf][aelfric][philology][historical_pragmatics][number]

「君主の we」 (royal_we) について「#5284. 単数の we --- royal we, authorial we, editorial we」 ([2023-10-15-1]) や「#5692. royal we --- 君主は自身を I ではなく we と呼ぶ?」 ([2024-11-26-1]) の記事で取り上げてきた.

OED の記述によると,古英語に royal we の古い例とおぼしきものが散見されるが,いずれも真正な例かどうかの判断が難しいとされる.Mitchell の OES (§252) への参照があったので,そちらを当たってみた.

§252. There are also places where a single individual other than an author seems to use the first person plural. But in some of these at any rate the reference may be to more than one. Thus GK and OED take we in Beo 958 We þæt ellenweorc estum miclum, || feohtan fremedon as referring to Beowulf alone---the so-called 'plural of majesty'. But it is more probably a genuine plural; as Klaeber has it 'Beowulf generously includes his men.' Such examples as ÆCHom i. 418. 31 Witodlice we beorgað ðinre ylde: gehyrsuma urum bebodum . . . and ÆCHom i. 428. 20 Awurp ðone truwan ðines drycræftes, and gerece us ðine mægðe (where the Emperor Decius addresses Sixtus and St. Laurence respectively) may perhaps also have a plural reference; note that Decius uses the singular in ÆCHom i. 426. 4 Ic geseo . . . me . . . ic sweige . . . ic and that in § ii. 128. 6 Gehyrsumiað eadmodlice on eallum ðingum Augustine, þone ðe we eow to ealdre gesetton. . . . Se Ælmihtiga God þurh his gife eow gescylde and geunne me þæt ic mote eoweres geswinces wæstm on ðam ecan eðele geseon . . . , where Pope Gregory changes from we to ic, we may include his advisers. If any of these are accepted as examples of the 'plural of majesty', they pre-date that from the proclamation of Henry II (sic) quoted by Bøgholm (Jespersen Gram. Misc., p. 219). But in this too we may include advisers: þæt witen ge wel alle, þæt we willen and unnen þæt þæt ure ræadesmen alle, oþer þe moare dæl of heom þæt beoþ ichosen þurg us and þurg þæt loandes folk, on ure kyneriche, habbeþ idon . . . beo stedefæst.

ここでは royal we らしく解せる古英語の例がいくつか挙げられているが,確かにいずれも1人称複数の用例として解釈することも可能である.最後に付言されている初期中英語からの例にしても,royal we の用例だと確言できるわけではない.素直な1人称複数とも解釈し得るのだ.いつの間にか,文献学と社会歴史語用論の沼に誘われてしまった感がある.

ちなみに,上記引用中の "the proclamation of Henry II" は "the proclamation of Henry III" の誤りである.英語史上とても重要な「#2561. The Proclamation of Henry III」 ([2016-05-01-1]) を参照.

・ Mitchell, Bruce. Old English Syntax. 2 vols. New York: OUP, 1985.

2024-10-06 Sun

■ #5641. 「ゼロから学ぶはじめての古英語」 Part 10 with 小河舜さん&まさにゃん at 「英語史ライヴ2024」 [voicy][heldio][hellive2024][masanyan][ogawashun][oe][oe_text][beowulf][hajimeteno_koeigo][hel_education][notice][popular_passage][literature][helkatsu][instagram][khelf]

9月8日(日)に12時間の公開収録生配信として開催された「英語史ライヴ2024」(hellive2024) の目玉企画の1つとして,人気シリーズ「はじめての古英語」(hajimeteno_koeigo) の第10弾「#1219. 「はじめての古英語」第10弾 with 小河舜さん&まさにゃん --- 「英語史ライヴ2024」より」が実現しました.講師はいつものように,小河舜さん(上智大学),「まさにゃん」こと森田真登さん(武蔵野学院大学),そして堀田隆一の3名です.

多くのギャラリーの方々を前にしての初めての公開収録となり,3名とも興奮のなかで34分ほどの古英語講座を展開しました.冒頭のコールを含め,これほど古英語で盛り上がる集団なり回なりは,かつて存在したでしょうか? おそらく歴史的なイベントになったのではないかと思います(笑).

今回の第10弾は,小河さん主導で古英詩の傑作 Beowulf の冒頭にほど近い ll. 24--25 の1文に注目しました(以下 Jack 版より).

lofdǣdum sceal in mǣgþa gehwǣre man geþēon.

忍足による日本語訳によれば「いかなる民にあっても,人は名誉ある/行いをもって栄えるものである」となります.古英語の文法や語彙の詳しい解説は,上記配信回をじっくりお聴きください.

実は上記の公開収録は Voicy heldio のほか,khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)の公式 Instagram アカウント @khelf_keioでインスタ動画としても生配信・収録しております.ヴィジュアルも欲しいという方は,ぜひこちらよりご覧ください.会場の熱気が感じられると思います.

シリーズ過去回は hajimeteno_koeigo よりご訪問ください.

・ Jack, George, ed. Beowulf: A Student Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1994.

・ 忍足 欣四郎(訳) 『ベーオウルフ』 岩波書店,1990年.

2024-07-28 Sun

■ #5571. 朝カル講座「現代の英語に残る古英語の痕跡」のまとめ [asacul][notice][lexicology][vocabulary][oe][kenning][beowulf][compounding][derivation][word_formation][celtic][contact][borrowing][etymology][kdee]

先日の記事「#5560. 7月27日(土)の朝カル新シリーズ講座第4回「現代の英語に残る古英語の痕跡」のご案内」 ([2024-07-17-1]) でお知らせした通り,昨日朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にてシリーズ講座「語源辞典でたどる英語史」の第4回「現代の英語に残る古英語の痕跡」を開講しました.今回も教室およびオンラインにて多くの方々にご参加いただき,ありがとうございました.

古英語と現代英語の語彙を比べつつ,とりわけ古英語のゲルマン的特徴に注目した回となっています.古英語期の歴史的背景をさらった後,古英語には借用語は比較的少なく,むしろ自前の要素を組み合わせた派生語や複合語が豊かであることを強調しました.とりわけ複合 (compounding) からは kenning (隠喩的複合語)と呼ばれる詩情豊かな表現が多く生じました.ケルト語との言語接触に触れた後,「#1124. 「はじめての古英語」第9弾 with 小河舜さん&まさにゃん&村岡宗一郎さん」で注目された Beowulf からの1文を取り上げ,古英語単語の語源を1つひとつ『英語語源辞典』で確認していきました.

以下,インフォグラフィックで講座の内容を要約しておきます.

2024-07-27 Sat

■ #5570. 古英語の動詞 dugan と agan の活用 [oe][preterite-present_verb][inflection][beowulf][voicy][heldio][etymology][hajimeteno_koeigo]

「#5542. 「ゼロから学ぶはじめての古英語」 Part 9 with 小河舜さん,まさにゃん,村岡宗一郎さん」 ([2024-06-29-1]) では,Voicy heldio の人気シリーズの最新回となる「#1124. 「はじめての古英語」第9弾 with 小河舜さん&まさにゃん&村岡宗一郎さん」を紹介しました.その配信回では,小河さんによって取り上げられた Beowulf からの1文が話題となりました.

Wyrd oft nereð/ unfǣgne eorl, þonne his ellen dēah. (ll. 572b--73)

"Fate often saves an undoomed earl, when his courage avails."

「運命はしばしば死すべき運命にない勇士を救う,彼の勇気が役立つ時に」

引用の最後の語 dēah は, "to be good, to be strong, to avail" 意味する dugan という動詞の3単現の形です.妙な形態ですが,それもそのはず,歴史的には過去現在動詞 (preterite-present_verb) と呼ばれる特殊な型の動詞でした(cf. 「#66. 過去現在動詞」 ([2009-07-03-1])).

Sweet's Anglo-Saxon Primer (37) より,この動詞の活用表を,もう1つのよく似た仲間の動詞 āgan "to own, possess" と並べて掲げましょう.

| Infin. | dugan 'avail' | āgan 'own' | ||

| Pres. | sing. | 1, 3. | dēah | āh |

| Pres. | sing. | 2. | āhst | |

| Pres. | pl. | dugon | āgon | |

| Pres. | subj. | dyge, duge | āge | |

| Pret. | dohte | āhte | ||

| Past | part. | āgen (only as adj.) |

いずれの動詞も,その後は複雑な歴史をたどりました.dugan については,doughty (勇敢な,有能な),dow ([北部・スコットランド方言]成功する,うまくやる)が関連語として現代に伝わっています.

・ Davis, Norman. Sweet's Anglo-Saxon Primer. 9th ed. Oxford: Clarendon, 1953.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2024-06-29 Sat

■ #5542. 「ゼロから学ぶはじめての古英語」 Part 9 with 小河舜さん,まさにゃん,村岡宗一郎さん [voicy][heldio][masanyan][ogawashun][oe][oe_text][beowulf][hajimeteno_koeigo][hel_education][notice][popular_passage][literature][preterite-present_verb][helkatsu]

先週の木曜日,6月20日(木)の夜に,堀田研究室に4名の英語史学徒が集結しました.そこで Voicy heldio にて「はじめての古英語」シリーズの第9弾を収録し,それを一昨日「#1124. 「はじめての古英語」第9弾 with 小河舜さん&まさにゃん&村岡宗一郎さん」としてお届けしました.生配信ではありませんでしたが,ライヴ感のある充実した内容となっているかと思います.ぜひお聴きいただければ.

今回の収録は,レギュラーメンバーの小河舜さん(上智大学),「まさにゃん」こと森田真登さん(武蔵野学院大学)に加え,村岡宗一郎さん(日本大学)をお呼びして収録しました.今回は古英語のある1文に集中しましたが,それだけで十分に堪能することができました.

上記のシリーズ回の翌日には「#1125. 「はじめての古英語」第9弾のアフタートーク」で,さらに4人が盛り上がる様子をお届けしています.個々のメンバーによる音読もあり,こちらも必聴です.

シリーズを重ねるにつれ,お聴きの皆さんの古英語への関心が高まってきているように感じます.さらにいえば,hel活 (helkatsu) 全般が活気づいてきています.リスナーの Grace さんによる A to Z の「英語史研究者紹介」というべき note,lacolaco さんによる「英語語源辞典通読ノート」,Lilimi さんによる古英語ファンアートを含む「Lilimiのオト」,り~みんさんによる X 上での古英語音読の試みなど,さまざまに盛り上がってきています

「はじめての古英語」シリーズ (hajimeteno_koeigo),これからも続けていければと思います.

2024-06-12 Wed

■ #5525. 古英語文学 --- Baugh and Cable の英語史の第52節より [bchel][oe][literature][beowulf][wulfstan][voicy][heldio][notice][hel_education][link]

Baugh and Cable の英語史の古典的名著 A History of the English Language (第6版)を原書で「超」精読する Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ」 (heldio) のシリーズ企画を進めています.このシリーズは普段は有料配信なのですが,この名著を広めていきたいという思いもあり,たまにテキストを公開しながら無料配信も行なっています.これまでのシリーズ配信回のバックナンバーは「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) でご確認ください.

目下,第3章をおおよそ読了するところまで来ています.第3章の最後を飾るのが第52節 "Old English Literature" (pp. 65--68) です.古英語文学に関する重要な3ページ超の節で,短時間で超精読するにはなかなか手強い節です.これを私1人で解説するには荷が重いということで,本日6月12日(水)の夕方5時半頃より,強力な助っ人をお招きして,60分弱の対談精読実況生中継として2人でお届けする予定です(それでも終わらなければ,プレミアム限定配信 helwa で引き続き生配信することも十分にあり得ます).聴取はこちらからどうぞ.

今回は公開配信ということで,テキストも以下に掲載し公開しておきます(が,シリーズ継続のために,ぜひ本書を入手していただければ). *

52. Old English Literature. The language of a past time is know by the quality of its literature. Charters and records yield their secrets the philologist and contribute their quota of words and inflections to our dictionaries and grammars. But it is in literature that a language displays its full power, its ability to convey in vivid and memorable form the thoughts and emotions of a people. The literature of the Anglo-Saxons is fortunately one of the richest and most significant of any preserved among the early Germanic peoples. Because it is the language mobilized, the language in action, we must say a word about it.

Generally speaking, this literature is of two sorts. Some of it was undoubtedly brought to England by the Germanic conquerors from their continental homes and preserved for a time in oral tradition. All of it owes its preservation, however, and not a little its inspiration to the reintroduction of Christianity into the southern part of the island at the end of the sixth century, an event whose significance for the English language will be discussed in the next chapter. Two streams thus mingle in Old English literature, the pagan and the Christian, and they are never quite distinct. The poetry of pagan origin is constantly overlaid with Christian sentiment, while even those poems that treat of purely Christian themes contain every now and again traces of an earlier philosophy not wholly forgotten. We can indicate only in the briefest way the scope and content of this literature, and we shall begin with that which embodies the native traditions of the people.

The greatest single work of Old English literature is Beowulf. It is a poem of some 3,000 lines belonging to the type known as the folk epic, that is to say, a poem which, whatever it may owe to the individual poet who gave it final form, embodies material long current among the people. It is a narrative of heroic adventure relating how a young warrior, Beowulf, fought the monster Grendel, which was ravaging the land of King Hrothgar, slew it and its mother, and years later met his death while ridding his own country of an equally destructive foe, a fire-breathing dragon. The theme seems somewhat fanciful to a modern reader, but the character of the hero, the social conditions pictured, and the portrayal of the motives and ideals that animated people in early Germanic times make the poem one of the most vivid records we have of life in the heroic age. It is not an easy life. It is a life that calls for physical endurance, unflinching courage, and a fine sense of duty, loyalty, and honor. A stirring expression of the heroic ideal is in the words that Beowulf addresses to Hrothgar before going to his dangerous encounter with Grendel's mother: "Sorrow not... . Better is it for every man that he avenge his friend than that he mourn greatly. Each of us must abide the end of this world's life; let him who may, work mighty deeds ere he die, for afterwards, when he lies lifeless, that is best for the warrior."

Outside of Beowulf, Old English poetry of the native tradition is represented by a number of shorter pieces. Anglo-Saxon poets sang of the things that entered most deeply into their experience---of war and of exile, of the sea with its hardships and its fascination, of ruined cities, and of minstrel life. One of the earliest products of Germanic tradition is a short poem called Widsith in which a scop or minstrel pretends to give an account of his wanderings and of the many famous kings and princes before whom he has exercised his craft. Deor, another poem about a minstrel, is the lament of a scop who for years has been in the service of his lord and now finds himself thrust out by a younger man. But he is no whiner. Life is like that. Age will be displaced by youth. He has his day. Peace, my heart! Deor is one of the most human of Old English poems. The Wanderer is a tragedy in the medieval sense, the story of a man who once enjoyed a high place and has fallen upon evil times. His lord is dead and he has become a wanderer in strange courts, without friends. Where are the snows of yesteryear? The Seafarer is a monologue in which the speaker alternately describes the perils and hardships of the sea and the eager desire to dare again its dangers. In The Ruin, the poet reflects on a ruined city, once prosperous and imposing with its towers and halls, its stone courts and baths, now but the tragic shadow of what it once was. Two great war poems, the Battle of Brunanburh and the Battle of Maldon, celebrate with patriotic fervor stirring encounters of the English, equally heroic in victory and defeat. In its shorter poems, no less than in Beowulf, Old English literature reveals at wide intervals of time the outlook and temper of the Germanic mind.

More than half of Anglo-Saxon poetry is concerned with Christian subjects. Translations and paraphrases of books of the Old and New Testament, legends of saints, and devotional and didactic pieces constitute the bulk of this verse. The most important of this poetry had its origin in Northumbria and Mercia in the seventh and eighth centuries. The earliest English poet whose name we know was Cædmon, a lay brother in the monastery at Whitby. The story of how the gift of song came to him in a dream and how he subsequently turned various parts of the Scriptures into beautiful English verse comes to us in the pages of Bede. Although we do not have his poems on Genesis, Exodus, Daniel, and the like, the poems on these subjects that we do have were most likely inspired by his example. About 800, and Anglian poet named Cynewulf wrote at least four poems on religious subjects, into which he ingeniously wove his name by means of runes. Two of these, Juliana and Elene, tell well-known legends of saints. A third, Christ, deals with Advent, the Ascension, and the Last Judgment. The fourth, The Fates of the Apostles, touches briefly on where and how the various apostles died. There are other religious poems besides those mentioned, such as the Andreas, two poems on the life of St. Guthlac, a portion of a fine poem on the story of Judith in the Apocrypha; The Phoenix, in which the bird is taken as a symbol of the Christian life; and Christ and Satan, which treats the expulsion of Satan from Paradise together with the Harrowing of Hell and Satan's tempting of Christ. All of these poems have their counterparts in other literatures of the Middle Ages. They show England in its cultural contact with Rome and being drawn into the general current of ideas on the continent, no longer simply Germanic, but cosmopolitan.

In the development of literature, prose generally comes late. Verse is more effective for oral delivery and more easily retained in the memory. It is therefore a rather remarkable fact, and one well worthy of note, that English possessed a considerable body of prose literature in the ninth century, at a time when most other modern languages in Europe had scarcely developed a literature in verse. This unusual accomplishment was due to the inspiration of one man, the Anglo-Saxon king who is justly called Alfred the Great (871--99). Alfred's greatness rests not only on his capacity as a military leader and statesman but also on his realization that greatness in a nation is no simply physical thing. When he came to the throne he found that the learning which in the eight century, in the days of Bede and Alcuin, had placed England in the forefront of Europe, had greatly decayed. In an effort to restore England to something like its former state, he undertook to provide for his people certain books in English, books that he deemed most essential to their welfare. With this object in view, he undertook in mature life to learn Latin and either translated these books himself or caused others to translate them for him. First as a guide for the clergy he translated the Pastoral Care of Pope Gregory, and then, in order that the people might know something of their own past, inspired and may well have arranged for a translation of Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. A history of the rest of the world also seemed desirable and was not so easily to be had. But in the fifth century when so many calamities were befalling the Roman Empire and those misfortunes were being attributed to the abandonment of the pagan deities in favor of Christianity, a Spanish priest named Orosius had undertaken to refute this idea. His method was to trace the rise of other empires to positions of great power and their subsequent collapse, a collapse in which obviously Christianity had had no part. The result was a book which, when its polemical aim had ceased to have any significance, was still widely read as a compendium of historical knowledge. This Alfred translated with omissions and some additions of his own. A fourth book that he turned into English was The Consolation of Philosophy b Boethius, one of the most famous books of the Middle Ages. Alfred also caused a record to be compiled of the important events of English history, past and present, and this, as continued for more than two centuries after his death, is the well-known Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. King Alfred was the founder of English prose, but there were others who carried on the tradition. Among these is Ælfric, the author of two books of homilies and numerous other works, and Wulfstan, whose Sermon to the English is an impassioned plea for moral and political reform.

So large and varied a body of literature, in verse and prose, gives ample testimony to the universal competence, at times to the power of beauty, of the Old English language.

終わり方も実に味わい深いですね.さて,次回からは第4章 "Foreign Influences on Old English" へと進みます.

(以下,後記:2024/06/16(Sun)

上記の生放送は2時間かけて配信されました.アーカイヴでは2回に分けてお届けしました(2回目はプレミアム限定配信となります).

(1) 「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (52) Old English Literature --- 和田忍さんとの実況中継(前半)」

(2) 「【英語史の輪 #146】 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (52) Old English Literature --- 和田忍さんとの実況中継(後半)」

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2023-09-16 Sat

■ #5255. Voicy heldio の「ゼロから学ぶはじめての古英語」シリーズへご好評いただいています [oe][masanyan][ogawashun][hel_education][voicy][heldio][runic][anglo-saxon][link][notice][alfred][beowulf][proverb][heldio_community][hajimeteno_koeigo]

毎朝6時に音声配信している Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」にて「ゼロから学ぶはじめての古英語」シリーズが始まっています(不定期で無料の配信です).第3回まで配信してきましたが,嬉しいことにリスナーの皆さんにはご好評いただいています.各配信回の概要欄やチャプターに紐付けられたリンク先に,題材となっている古英語のテキストなども掲載していますので,そちらを参照しながら聴いていただければと思います.これまでの3回では,アルフレッド大王,古英語の格言,叙事詩『ベオウルフ』に関係する文章が取り上げられています.本当に「初めての方」に向けての講座となっていますので,お気軽にどうぞ.

ナビゲーターは英語史や古英語を専攻する次の3人です.小河舜さん(フェリス女学院大学ほか),khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)元会長の「まさにゃん」こと森田真登さん(武蔵野学院大学),および堀田隆一です.3人で楽しそうに話しているのが魅力,との評価もいただいています.

毎回,厳選された古英語の短文を取り上げ,文字通り「ゼロから」解説しています.日本語による解説つきで気軽に始められる「古英語講座」なるものは,おそらくこれまでどの媒体においても皆無だったのではないでしょうか(唯一の例外は,まさにゃんによる「毎日古英語」かもしれません).このたびのシリーズは,その意味では本邦初といってよい試みとなります.ナビゲーター3人も,肩の力を抜いておしゃべりしていますので,それに見合った気軽さで聴いていただければと思います.

本シリーズのサポートページとして,まさにゃんによる note 記事「ゼロから学ぶはじめての古英語(#1~#3)」が公開されています.また,X(旧ツイッター)上の「heldio コミュニティ by 堀田隆一」にて関連情報も発信しています.このコミュニティは承認制ですが,基本的にはメンバーリクエストをいただければお入りいただけますので,ぜひご参加ください.

シリーズの第4弾もお楽しみに!

2023-08-18 Fri

■ #5226. アングロサクソン人名の名付けの背景にある2つの動機づけ [name_project][onomastics][personal_name][anglo-saxon][oe][bede][beowulf]

昨日の記事「#5225. アングロサクソン人名の構成要素 (2)」 ([2023-08-17-1]) で,Clark を参照して Bede にみられる古英語人名の傾向を確認した.そこでの人名を構成する "themes" に対応する語彙は,古英詩 Beowulf でもよく用いられている単語群であり,古英語における文化的キーワードを表わすものといえるかもしれない.

一方で,名付けの実際に当たっては,それぞれの themes の意味が,古英語期に共時的に理解されていたかどうかは分からない.当初は名前に込められていた「意味」が形骸化するのはよくあることだし,Beowulf の語彙は詩の語彙であり,古英語当時ですら古風だったことは,よく指摘されきたことである.アングロサクソンの文化的キーワードというよりも文化遺産的キーワードといったほうがよいようにも思われる.

この点について,Clark も慎重な見解を示している (457--58) .

Name themes thus largely parallel the diction of heroic verse . . . . Kindred elements in the diction of Beowulf include common items such as beorht, cēne, cūð, poetic ones such as brego and torht, and also, more strikingly, compounds like frēawine 'lord and friend', gārcēne 'bold with spear', gūðbeorn 'battle-warrior', heaðomǣre 'renowned in battle', hildebill 'battle-blade', wīgsigor 'victorious in battle' . . . . Parallels must not be pressed; for rules of formation differed and, more crucially, such 'meaning' as name-compounds possessed was not in practice etymological. Name-themes might, besides, long out-live related items of daily, even literary, vocabulary: non-onomastic Old English usage shows no cognate of the feminine deuterotheme -flǣd 'beauty' and, as cognates of Tond- 'fire', only the mutated derivatives ontendan 'kindle' and tynder 'kindling wood'. Resemblances between naming and heroic diction nonetheless suggest motivations behind the original Germanic styles: hopes and wishes appropriate to a warrior society, and perhaps belief in onomastic magic . . . .

引用の最後にあるように,Clark はアングロサクソン人名の名付けの背景にある2つの動機づけとして (1) 戦士社会にふさわしい望みと願い,(2) 名前の魔法への信仰,を挙げている.アングロサクソン特有という見方もできるが,一歩引いて見ればある意味で名付けの普遍的動機づけともとらえられそうだ.

上で少し触れた名前における「意味」をめぐる問題については,以下も参照.

・ hellog 「#2212. 固有名詞はシニフィエなきシニフィアンである」 ([2015-05-18-1])

・ hellog 「#5197. 固有名に意味はあるのか,ないのか?」 ([2023-07-20-1])

・ heldio 「#665. 固有名詞には指示対象はあるけれども意味はないですよネ」(2023年3月27日)

・ Clark, Cecily. "Onomastics." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 1. Ed. Richard M. Hogg. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 452--89.

2023-08-08 Tue

■ #5216. Beowulf について専門家にアレコレ尋ねてみました [beowulf][oe][literature][voicy][heldio][manuscript][rhetoric]

先日の hellog 「#5206. Beowulf の冒頭11行を音読」 ([2023-07-29-1]) や Voicy heldio 「#783. 古英詩の傑作『ベオウルフ』 (Beowulf) --- 唐澤一友さん,和田忍さん,小河舜さんと飲みながらご紹介」を通じて,古英語で書かれた代表的な英雄詩 Beowulf に関心をもたれた方もいるかと思います.

前回に引き続き,古英語を専門とする唐澤一友氏(立教大学),和田忍氏(駿河台大学),小河舜氏(フェリス女学院大学ほか)の3名と,酒を交わしながら Beowulf 談義を繰り広げました.とりわけこの作品の専門家である唐澤氏に,Beowulf はいかにして現代に伝わってきたのか,その言葉遣いの特徴は何か,その物語はいつ成立したのか等の質問を投げかけ,回答をいただきました.

本編のみで40分ほどの長尺となっており(しかも終わりの方は少々荒れてい)ますが,時間のあるときにお聴きいただければ.

・ heldio 「#797. 唐澤一友さんに Beowulf のことを何でも質問してみました with 和田忍さん and 小河舜さん」

この作品に関心を抱いた方は,本ブログの beowulf の各記事もご覧下さい.

2023-07-30 Sun

■ #5207. 朝カルのシリーズ講座「文字と綴字の英語史」の第2回「古英語の綴字 --- ローマ字の手なずけ」を終えました [asacul][writing][grammatology][alphabet][notice][spelling][oe][literature][beowulf][runic][christianity][latin][alliteration][distinctiones][punctuation][standardisation][voicy][heldio]

先日「#5194. 7月29日(土),朝カルのシリーズ講座「文字と綴字の英語史」の第2回「古英語の綴字 --- ローマ字の手なずけ」」 ([2023-07-17-1]) でご案内した通り,昨日,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室にてシリーズ講座「文字と綴字の英語史」の第2回となる「古英語の綴字 --- ローマ字の手なずけ」を開講しました.多くの方々に対面あるいはオンラインで参加いただきまして感謝申し上げます.ありがとうございました.

古英語期中に,いかにして英語話者たちがゲルマン民族に伝わっていたルーン文字を捨て,ローマ字を受容したのか.そして,いかにしてローマ字で英語を表記する方法について時間をかけて模索していったのかを議論しました.ローマ字導入の前史,ローマ字の手なずけ,ラテン借用語の綴字,後期古英語期の綴字の標準化 (standardisation) ,古英詩 Beowulf にみられる文字と綴字について,3時間お話ししました.

昨日の回をもって全4回シリーズの前半2回が終了したことになります.次回の第3回は少し先のことになりますが,10月7日(土)の 15:00~18:45 に「中英語の綴字 --- 標準なき繁栄」として開講する予定です.中英語期には,古英語期中に発達してきた綴字習慣が,1066年のノルマン征服によって崩壊するするという劇的な変化が生じました.この大打撃により,その後の英語の綴字はカオス化の道をたどることになります.

講座「文字と綴字の英語史」はシリーズとはいえ,各回は関連しつつも独立した内容となっています.次回以降の回も引き続きよろしくお願いいたします.日時の都合が付かない場合でも,参加申込いただけますと後日アーカイブ動画(1週間限定配信)にアクセスできるようになりますので,そちらの利用もご検討ください.

本シリーズと関連して,以下の hellog 記事をお読みください.

・ hellog 「#5088. 朝カル講座の新シリーズ「文字と綴字の英語史」が4月29日より始まります」 ([2023-04-02-1])

・ hellog 「#5194. 7月29日(土),朝カルのシリーズ講座「文字と綴字の英語史」の第2回「古英語の綴字 --- ローマ字の手なずけ」」 ([2023-07-17-1])

同様に,シリーズと関連づけた Voicy heldio 配信回もお聴きいただければと.

・ heldio 「#668. 朝カル講座の新シリーズ「文字と綴字の英語史」が4月29日より始まります」(2023年3月30日)

・ heldio 「#778. 古英語の文字 --- 7月29日(土)の朝カルのシリーズ講座第2回に向けて」(2023年7月18日)

2023-07-29 Sat

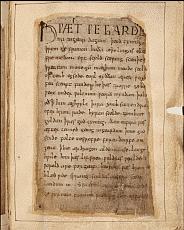

■ #5206. Beowulf の冒頭11行を音読 [voicy][heldio][beowulf][oe][literature][oe_text][popular_passage][manuscript]

「#2893. Beowulf の冒頭11行」 ([2017-03-29-1]) と「#2915. Beowulf の冒頭52行」 ([2017-04-20-1]) で,古英詩の傑作 Beowulf の冒頭を異なるエディションより紹介しました.今回は Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」と連動させ,この詩の冒頭11行を Jack 版から読み上げてみたので,ぜひ聴いていただければと思います.「#789. 古英詩の傑作『ベオウルフ』の冒頭11行を音読」です.以下に,Jack 版と忍足による日本語訳のテキスト,および写本画像を掲げておきます.

1 Hwæt, wē Gār-Dena in geārdagum, いざ聴き給え,そのかみの槍の誉れ高きデネ人の勲,民の王たる人々の武名は, 2 þēodcyninga þrym gefrūnon, 貴人らが天晴れ勇武の振舞をなせし次第は, 3 hū ðā æþelingas ellen fremedon. 語り継がれてわれらが耳に及ぶところとなった. 4 Oft Scyld Scēfing sceaþena þrēatum, シェーフの子シュルドは,初めに寄る辺なき身にて 5 monegum mǣgþum meodosetla oftēah, 見出されて後,しばしば敵の軍勢より, 6 egsode eorl[as], syððan ǣrest wearð 数多の民より,蜜酒の席を奪い取り,軍人らの心胆を 7 fēasceaft funden; hē þæs frōfre gebād, 寒からしめた.彼はやがてかつての不幸への慰めを見出した. 8 wēox under wolcnum, weorðmyndum þāh, すなわち,天が下に栄え,栄光に充ちて時めき, 9 oðþæt him ǣghwylc þ[ǣr] ymbsittendra 遂には四隣のなべての民が 10 ofer hronrāde hȳran scolde, 鯨の泳ぐあたりを越えて彼に靡き, 11 gomban gyldan. Þæt wæs gōd cyning! 貢を献ずるに至ったのである.げに優れたる君王ではあった.

Beowulf については,本ブログでも beowulf の各記事で取り上げてきました.また,この作品については,先日 Voicy heldio で専門家との対談を収録・配信したので,そちらもお聴き下さい.「#783. 古英詩の傑作『ベオウルフ』 (Beowulf) --- 唐澤一友さん,和田忍さん,小河舜さんと飲みながらご紹介」です.

古英語の響きに関心を持った方は,ぜひ Voicy heldio より以下もお聴きいただければ.

・ 「#326. どうして古英語の発音がわかるのですか?」

・ 「#321. 古英語をちょっとだけ音読 マタイ伝「岩の上に家を建てる」寓話より」

・ 「#735. 古英語音読 --- マタイ伝「種をまく人の寓話」より毒麦の話」

・ 「#766. 古英語をちょっとだけ音読 「キャドモンの賛歌」」

・ Jack, George, ed. Beowulf: A Student Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1994.

・ 忍足 欣四郎(訳) 『ベーオウルフ』 岩波書店,1990年.

2021-10-12 Tue

■ #4551. 19世紀に Beowulf の価値が高騰した理由 [beowulf][oe][literature][language_myth][manuscript][history][reformation][philology][linguistic_imperialism][oed]

「#4541. 焼失を免れた Beowulf 写本の「使い途」」 ([2021-10-02-1]) でみたように,Beowulf 写本とそのテキストは,"myth of the longevity of English" を創出し確立するのに貢献してきた.主に文献学的な根拠に基づいて,その制作時期を紀元700年頃と推定することにより,英語と英文学の歴史的時間幅がぐんと延びることになったからだ.しかも,文学的に格調の高い叙事詩とあっては,うってつけの宣伝となる.

Beowulf の価値が高騰し,この「神話」が醸成されたのは,19世紀だったことに注意が必要である.なぜこの時期だったのだろうか.なぜ,例えばアングロサクソン学が始まった16世紀などではなかったのだろうか.Watts (52) は,これが19世紀的な現象であることを次のように説明している.

As a whole the longevity of English myth, consisting of the ancient language myth and the unbroken tradition myth, was a nineteenth-century phenomenon that lasted almost till the end of the twentieth century. The need to establish a linguistic pedigree for English was an important discourse archive within the framework of the growth of the nation-state and the Age of Imperialism. In the face of competition from other European languages, particularly French, it was perhaps necessary to construct English as a Kultursprache, and one way to do this was to trace English to its earliest texts.

端的にいえば,イギリスは,イギリス帝国の威信を対外的に喧伝するために,その象徴である英語という言語が長い伝統を有することを,根拠をもって示す必要があった,ということだ.歴史的原則に立脚した OED の編纂も,この19世紀の文脈のなかでとらえる必要がある(cf. 「#3020. 帝国主義の申し子としての比較言語学 (1)」 ([2017-08-03-1]),「#3021. 帝国主義の申し子としての比較言語学 (2)」 ([2017-08-04-1]),「#3376. 帝国主義の申し子としての英語文献学」 ([2018-07-25-1])).

16世紀には,さすがにまだそのような動機づけは存在していなかった.その代わりに16世紀のイングランドには別の関心事があった.それは,ヘンリー7世によって開かれたばかりのテューダー朝をいかに権威づけるか,そしてヘンリー8世によって設立された英国国教会をいかに正当化するか,ということだった.この目的のために,ノルマン朝より古いアングロサクソン時代に,キリスト教文典や法律が英語という土着語で書かれていたという歴史的事実が利用されることになった.テューダー朝はとりわけ宗教改革に揺さぶられていた時代であるから,宗教的なテキストの扱いには慎重だった.一方,Beowulf のような民族叙事詩のテキストには,相対的にいってさほどの関心が注がれなかったというわけだ.Watts (52) は次のように述べている.

The dominant discourse archive at this particular moment of conjunctural time [= the sixteenth century] was religious. It was the struggle to assert Protestantism after the break with the Church of Rome that determined the focus on religious, legal, constitutional and historical texts of the Anglo-Saxon era. The Counter-Reformation in the seventeenth century sustained this dominant discourse and relegated interest in the longevity of the language and the poetic value of texts like Beowulf till a much later period.

・ Watts, Richard J. Language Myths and the History of English. Oxford: OUP, 2011.

2021-10-02 Sat

■ #4541. 焼失を免れた Beowulf 写本の「使い途」 [beowulf][oe][literature][language_myth][manuscript]

1731年10月23日,ウェストミンスターのアシュバーナム・ハウスが火事に見舞われた.そこに収納されていたコットン卿蔵書 (Cottonian Library) も焼けたが,辛くも焼失を免れた古写本のなかに古英語の叙事詩 Beowulf のテキストを収めた写本があった.これについて Watts (29) が次のように述べている.

The loss of Beowulf would have meant the loss of the greatest literary work and one of the most puzzling and enigmatic texts produced during the Anglo-Saxon period.

仮定法の文だが,裏を返せば英文学を代表する最も偉大な作品が奇跡的にも火事から救われたという趣旨の文である.英文学者や英語史学者ならずとも,ほとんどの人々が,この写本が消失を免れて本当によかったと思うだろう.

しかし,「言語の神話」の解体をもくろむ Watts の考えは異なる.焼失したほうがよかったと主張するわけでは決してないが,驚くことに次のように文章を続けるのだ.

But it would also have made one of the most powerful linguistic myths focusing on the English language, the myth of the longevity of English, immeasurably more difficult to construct. This is not because other Anglo-Saxon texts have not come down to us; it is, rather, because of the perceived literary and linguistic value of Beowulf. To construct the longevity myth one needs to locate such texts, and the further back in time they can be located, the "older" the language becomes and the greater is the "cultural" significance that can be associated with that language.

Watts の主張は,焼失を免れた Beowulf 写本は,英語に関する最も強力な神話,すなわち「英語長寿神話」を創出し,確立させるのに利用されてきたということだ.Beowulf 写本が生き残ったことにより「英語は歴史のある偉大な言語である」と言いやすくなったというわけだ.

現に Beowulf 写本が生き残ったのは偶然である.別の棚に保存されていたら焼失していたかもしれない.そして,もし焼けてしまっていたならば,英文学や英語はさほど歴史がないことになり,さほど偉大でもなくなるだろう.英文学や英語は別の「売り」を探さなければならなかったに違いない.

この見方は,英文学や英語が偉大かそうでないかは火事の及んだ範囲という偶然に依存しており,必然的に,あるいは本質的に偉大なわけではないという洞察につながる.これが,Watts が神話の解体によって行なおうとしていることなのだろう.

・ Watts, Richard J. Language Myths and the History of English. Oxford: OUP, 2011.

2017-04-20 Thu

■ #2915. Beowulf の冒頭52行 [beowulf][link][oe][literature][popular_passage][oe_text]

「#2893. Beowulf の冒頭11行」 ([2017-03-29-1]) で挙げた11行では物足りなく思われたので,有名な舟棺葬 (ship burial) の記述も含めた Beowulf 冒頭の52行を引用したい.舟棺葬とは,6--11世紀にスカンディナヴィアとアングロサクソンの文化で見られた高位者の葬法である.

原文は Jack 版で.現代英語訳は Norton Anthology に収録されているアイルランドのノーベル文学賞受賞詩人 Seamus Heaney の版でお届けする.

| OE | PDE translation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| a-verse | b-verse | ||

| Hwæt, wē Gār-Dena | in geārdagum, | So. The Spear-Danes in days gone by | |

| þēodcyninga | þrym gefrūnon, | and the kings who ruled them had courage and greatness. | |

| hū ðā æþelingas | ellen fremedon. | We have heard of those princes' heroic campaigns. | |

| Oft Scyld Scēfing | sceaþena þrēatum, | There was Shield Sheafson, scourge of many tribes, | |

| 5 | monegum mǣgþum | meodosetla oftēah, | a wrecker of mead-benches, rampaging among foes. |

| egsode eorl[as], | syððan ǣrest wearð | This terror of the hall-troops had come far. | |

| fēasceaft funden; | hē þæs frōfre gebād, | A foundling to start with, he would flourish later on | |

| wēox under wolcnum, | weorðmyndum þāh, | as his powers waxed and his worth was proved. | |

| oðþæt him ǣghwylc þ[ǣr] | ymbsittendra | In the end each clan on the outlying coasts | |

| 10 | ofer hronrāde | hȳran scolde, | beyond the whale-road had to yield to him |

| gomban gyldan. | Þæt wæs gōd cyning! | and begin to pay tribute. That was one good king. | |

| Ðǣm eafera wæs | æfter cenned | Afterward a boy-child was born to Shield, | |

| geong in geardum, | þone God sende | a cub in the yard, a comfort sent | |

| folce tō frōfre; | fyrenðearfe ongeat | by God to that nation. Hew knew what they had tholed, | |

| 15 | þ[e] hīe ǣr drugon | aldor[lē]ase | the long times and troubles they'd come through |

| lange hwīle. | Him þæs Līffrēa, | without a leader; so the Lord of Life, | |

| wuldres Wealdend | woroldāre forgeaf; | the glorious Almighty, made this man renowned. | |

| Bēowulf wæs brēme | ---blǣd wīde sprang--- | Shield had fathered a famous son: | |

| Scyldes eafera | Scedelandum in. | Beow's name was known through the north. | |

| 20 | Swā sceal [geong g]uma | gōde gewyrcean, | And a young prince must be prudent like that, |

| fromum feohgiftum | on fæder [bea]rme, | giving freely while his father lives | |

| þæt hine on ylde | eft gewunigen | so that afterward in age when fighting starts | |

| wilgesīþas | þonne wīg cume, | steadfast companions will stand by him | |

| lēode gelǣsten; | lofdǣdum sceal | and hold the line. Behavior that's admired | |

| 25 | in mǣgþa gehwǣre | man geþēon. | is the path to power among people everywhere. |

| Him ðā Scyld gewāt | tō gescæphwīle, | Shield was still thriving when his time came | |

| felahrōr fēran | on Frēan wǣre. | and he crossed over into the Lord's keeping. | |

| Hī hyne þā ætbǣron | tō brimes faroðe, | His warrior band did what he bade them | |

| swǣse gesīþas, | swā hē selfa bæd, | when he laid down the law among the Danes: | |

| 30 | þenden wordum wēold | wine Scyldinga; | they shouldered him out to the sea's flood, |

| lēof landfruma | lange āhte. | the chief they revered who had long ruled them. | |

| Þǣr æt hȳðe stōd | hringedstefna | A ring-whorled prow rode in the harbor, | |

| īsig ond ūtfūs, | æþelinges fær; | ice-clad, outbound, a craft for a prince. | |

| ālēdon þā | lēofne þēoden, | They stretched their beloved lord in his boat, | |

| 35 | bēaga bryttan | on bearm scipes, | laid out by the mast, amidships, |

| mǣrne be mæste. | Þǣr wæs mādma fela | the great ring-giver. Far-fetched treasures | |

| of feorwegum, | frætwa gelǣded; | were piled upon him, and precious gear. | |

| ne hȳrde ic cȳmlīcor | cēol gegyrwan | I never heard before of a ship so well furbished | |

| hildewǣpnum | ond heaðowǣdum, | with battle-tackle, bladed weapons | |

| 40 | billum ond byrnum; | him on bearme læg | and coats of mail. The massed treasure |

| mādma mænigo, | þā him mid scoldon | was loaded on top of him: it would travel far | |

| on flōdes ǣht | feor gewītan. | on out into the ocean's sway. | |

| Nalæs hī hine lǣssan | lācum tēodan, | They decked his body no less bountifully | |

| þēodgestrēonum, | þon þā dydon | with offerings than those first ones did | |

| 45 | þe hine æt frumsceafte | forð onsendon | who cast him away when he was a child |

| ǣnne ofer ȳðe | umborwesende. | and launched him alone out over the waves. | |

| Þā gȳt hie him āsetton | segen g[yl]denne | And they set a gold standard up | |

| hēah ofer hēafod, | lēton holm beran, | high above his head and let him drift | |

| gēafon on gārsecg. | Him wæs geōmor sefa, | to wind and tide, bewailing him | |

| 50 | murnende mōd. | Men ne cunnon | and mourning their loss. No man can tell, |

| secgan tō sōðe, | selerǣden[d]e, | no wise man in hall or weathered veteran | |

| hæleð under heofenum, | hwā þǣm hlæste onfēng. | knows for certain who salvaged that load. | |

・ Jack, George, ed. Beowulf: A Student Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1994.

・ Greenblatt, Stephen, ed. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 8th ed. New York:: Norton, 2006.

2017-03-29 Wed

■ #2893. Beowulf の冒頭11行 [beowulf][link][oe][literature][popular_passage][oe_text][hel_education]

Beowulf は,古英語で書かれた最も長い叙事詩(3182行)であり,アングロサクソン時代から現存する最も重要な文学作品である.スカンディナヴィアの英雄 Beowulf はデンマークで怪物 Grendel を殺し,続けてその母をも殺した.Beowulf は後にスウェーデン南部で Geat 族の王となるが,年老いてから竜と戦い,戦死する.

この叙事詩は,古英語で scop と呼ばれた宮廷吟遊詩人により,ハープの演奏とともに吟じられたとされる.現存する唯一の写本(1731年の火事で損傷している)は1000年頃のものであり,2人の写字生の手になる.作者は不詳であり,いつ制作されたかについても確かなことは分かっていない.8世紀に成立したという説もあれば,11世紀という説もある.

冒頭の11行を Crystal (18) より,現代英語の対訳付きで以下に再現しよう.

1 HǷÆT ǷE GARDEna in ȝeardaȝum . Lo! we spear-Danes in days of old 2 þeodcyninȝa þrym ȝefrunon heard the glory of the tribal kings, 3 hu ða æþelinȝas ellen fremedon . how the princes did courageous deeds. 4 oft scyld scefing sceaþena þreatum Often Scyld Scefing from bands of enemies 5 monegū mæȝþum meodo setla ofteah from many tribes took away mead-benches, 6 eȝsode eorl[as] syððan ærest ƿearð terrified earl[s], since first he was 7 feasceaft funden he þæs frofre ȝebad found destitute. He met with comfort for that, 8 ƿeox under ƿolcum, ƿeorðmyndum þah, grew under the heavens, throve in honours 9 oðþ[æt] him æȝhƿylc þara ymbsittendra until each of the neighbours to him 10 ofer hronrade hyran scolde over the whale-road had to obey him, 11 ȝomban ȝyldan þ[æt] ƿæs ȝod cyninȝ. pay him tribute. That was a good king!

冒頭部分を含む写本画像 (Cotton MS Vitellius A XV, fol. 132r) は,こちらから閲覧できる.その他,以下のサイトも参照.

・ Cotton MS Vitellius A XV, Augustine of Hippo, Soliloquia; Marvels of the East; Beowulf; Judith, etc.: 写本画像を閲覧可能.

・ Beowulf: BL による物語と写本の解説.

・ Beowulf Readings: 古英語原文と「読み上げ」へのアクセスあり.

・ Beowulf Translation: 現代英語訳.

・ Diacritically-Marked Text of Beowulf facing a New Translation (with explanatory notes): 古英語原文と現代英語の対訳のパラレルテキスト.

・ Crystal, David. Evolving English: One Language, Many Voices. London: The British Library, 2010.

2016-08-25 Thu

■ #2677. Beowulf にみられる「王」を表わす数々の類義語 [synonym][oe][lexicology][compounding][kenning][beowulf][metonymy]

古英語は複合 (compounding) による語形成が非常に得意な言語だった.これは「#1148. 古英語の豊かな語形成力」 ([2012-06-18-1]) でも確認済みだが,複合語はとりわけ韻文において最大限に活用された.実際 Beowulf に代表される古英詩においては「王」「勇士」「戦い」「海」などの頻出する概念に対して,様々な類義語 (synonym) が用いられた.これは,単調さを避けるためでもあったし,昨日の記事「#2676. 古英詩の頭韻」 ([2016-08-24-1]) で取り上げた頭韻の規則に沿うために種々の表現が必要だったからでもあった.

以下,Baker (137) より,Beowulf (及びその他の詩)に現われる「王,主君」を表わす類義語を列挙しよう(複合語が多いが,単形態素の語も含まれている).

bēagġyfa, masc. ring-giver.

bealdor, masc. lord.

brego, masc. lord.

folcāgend, masc. possessor of the people.

folccyning, masc. king of the people.

folctoga, masc. leader of the people.

frēa, masc. lord.

frēadrihten, masc. lord-lord.

frumgār, masc. first spear.

godlgġyfa, masc. gold-giver.

goldwine, masc. gold-friend.

gūðcyning, masc. war-king.

herewīsa, masc. leader of an army.

hildfruma, masc. battle-first.

hlēo, masc. cover, shelter.

lēodfruma, masc. first of a people.

lēodġebyrġea, masc. protector of a people.

mondryhten, masc. lord of men.

rǣswa, masc. counsellor.

siġedryhten, masc. lord of victory.

sincġifa, masc. treasure giver.

sinfrēa, masc. great lord.

þenġel, masc. prince.

þēodcyning, masc. people-king.

þēoden, masc. chief, lord.

wilġeofa, masc. joy-giver.

wine, masc. friend.

winedryhten, masc. friend-lord.

wīsa, masc. guide.

woroldcyning, masc. worldly king.

ここには詩にしか現われない複合語も多く含まれており,詩的複合語 (poetic compound) と呼ばれている.第1要素が第2要素を修飾する folccyning (people-king) のような例もあれば,両要素がほぼ同義で冗長な frēadrihten (lord-lord) のような例もある.さらに,メトニミーを用いた謎かけ・言葉遊び風の bēagġyfa (ring-giver) もある.最後に挙げた類いの比喩的複合語は kenning と呼ばれ,古英詩における大きな特徴となっている(「#472. kenning」 ([2010-08-12-1]) を参照).

・ Baker, Peter S. Introduction to Old English. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow