2020-03-31 Tue

■ #3991. なぜ仮定法には人称変化がないのですか? (2) [oe][verb][subjunctive][inflection][number][person][sound_change][analogy][sobokunagimon][conjugation][paradigm]

昨日の記事 ([2020-03-30-1]) に引き続き,標記の問題についてさらに歴史をさかのぼってみましょう.昨日の説明を粗くまとめれば,現代英語の仮定法に人称変化がないのは,その起源となる古英語の接続法ですら直説法に比べれば人称変化が稀薄であり,その稀薄な人称変化も中英語にかけて生じた -n 語尾の消失により失われてしまったから,ということになります.ここでもう一歩踏み込んで問うてみましょう.古英語という段階においてすら直説法に比べて接続法の人称変化が稀薄だったというのは,いったいどういう理由によるのでしょうか.

古英語と同族のゲルマン語派の古い姉妹言語をみてみますと,接続法にも直説法と同様に複雑な人称変化があったことがわかります.現代英語の to bear に連なる動詞の接続法現在の人称変化表(ゲルマン諸語)を,Lass (173) より説明とともに引用しましょう.Go はゴート語,OE は古英語,OIc は古アイスランド語を指します.

(iii) Present subjunctive. The Germanic subjunctive descends mainly from the old IE optative; typical paradigms:

(7.24)

Go OE OIc sg 1 baír-a-i ber-e ber-a 2 baír-ai-s " ber-er 3 baír-ai " ber-e pl 1 baír-ai-ma ber-en ber-em 2 baírai-þ " ber-eþ 3 baír-ai-na " ber-e

The basic IE thematic optative marker was */-oi-/, which > Gmc */-ɑi-/ as usual; this is still clearly visible in Gothic. The other dialects show the expected developments of this diphthong and following consonants in weak syllables . . . , except for the OE plural, where the -n is extended from the third person, as in the indicative. . . .

. . . .

(iv) Preterite subjunctive. Here the PRET2 grade is extended to all numbers and persons; thus a form like OE bǣr-e is ambiguous between pret ind 2 sg and all persons subj sg. The thematic element is an IE optative marker */-i:-/, which was reduced to /e/ in OE and OIc before it could cause i-umlaut (but remains as short /i/ in OS, OHG).

ここから示唆されるのは,古いゲルマン諸語では接続法でも直説法と同じように完全な人称変化があり,表の列を構成する6スロットのいずれにも独自の語形が入っていたということです.一般的に古い語形をよく残しているといわれる左列のゴート語が,その典型となります.ところが,古英語ではもともとの複雑な人称変化が何らかの事情で単純化しました.

では,何らかの事情とは何でしょうか.上の引用でも触れられていますが,1つにはやはり音変化が関与していました.古英語の前史において,ゴート語の語形に示される類いの語尾の母音・子音が大幅に弱化・消失するということが起こりました.その結果,接続法現在の単数は bere へと収斂しました.一方,接続法現在の複数は,3人称の語尾に含まれていた n (ゴート語の語形 baír-ai-na を参照)が類推作用 (analogy) によって1,2人称へも拡大し,ここに beren という不変の複数形が生まれました.上記は(強変化動詞の)接続法現在についての説明ですが,接続法過去でも似たような類推作用が起こりましたし,弱変化動詞もおよそ同じような過程をたどりました (Lass 177) .結果として,古英語では全体として人称変化の薄い接続法の体系ができあがったのです.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2020-03-30 Mon

■ #3990. なぜ仮定法には人称変化がないのですか? (1) [oe][verb][be][subjunctive][inflection][number][person][sound_change][sobokunagimon][conjugation][3ps][paradigm]

現代英語の仮定法では,各時制(現在と過去)内部において直説法にみられるような人称変化がみられません.仮定法現在では人称(および数)にかかわらず動詞は原形そのものですし,仮定法過去でも人称(および数)にかかわらず典型的に -ed で終わる直説法過去と同じ形態が用いられます.

もっとも,考えてみれば直説法ですら3人称単数現在で -(e)s 語尾が現われる程度ですので,現代英語では人称変化は全体的に稀薄といえますが,be 動詞だけは人称変化が複雑です.直説法においては人称(および数)に応じて現在時制では is, am, are が区別され,過去時制では were, were が区別されるからです.一方,仮定法においては現在時制であれば不変の be が用いられ,過去時制となると不変の were が用いられます(口語では仮定法過去で If I were you . . . ならぬ If I was you . . . のような用例も可能ですが,伝統文法では were を用いることになっています).be 動詞をめぐる特殊事情については,「#2600. 古英語の be 動詞の屈折」 ([2016-06-09-1]),「#2601. なぜ If I WERE a bird なのか?」 ([2016-06-10-1]),「#3284. be 動詞の特殊性」 ([2018-04-24-1]),「#3812. was と were の関係」 ([2019-10-04-1]))を参照ください.

今回,英語史の観点からひもといていきたいのは,なぜ仮定法には上記の通り人称変化が一切みられないのかという疑問です.仮定法は歴史的には接続法 (subjunctive) と呼ばれるので,ここからは後者の用語を使っていきます.現代英語の to love (右表)に連なる古英語の動詞 lufian の人称変化表(左表)を眺めてみましょう.

| 古英語 lufian | 直説法 | 接続法 | → | 現代英語 love | 直説法 | 接続法 | ||||||

| ?????? | 茲???? | ?????? | 茲???? | ?????? | 茲???? | ?????? | 茲???? | |||||

| 現在時制 | 1人称 | lufie | lufiaþ | lufie | lufien | 現在時制 | 1人称 | love | love | love | ||

| 2篋榊О | lufast | 2篋榊О | ||||||||||

| 3篋榊О | lufaþ | 3篋榊О | loves | |||||||||

| 過去時制 | 1人称 | lufode | lufoden | lufode | lufoden | 過去時制 | 1人称 | loved | loved | |||

| 2篋榊О | lufodest | 2篋榊О | ||||||||||

| 3篋榊О | lufode | 3篋榊О | ||||||||||

古英語でも接続法は直説法に比べれば人称変化が薄かったことが分かります.実際,純粋な意味での人称変化はなく,数による変化があったのみです.しかし,単数か複数かという数の区別も念頭においた広い意味での「人称変化」を考えれば,古英語の接続法では現代英語と異なり,一応のところ,それは存在しました.現在時制では主語が単数であれば lufie,複数であれば lufien ですし,過去時制では主語が単数で lufode, 複数で lufoden となりました.いずれも単数形に -n 語尾を付したものが複数となっています.小さな語尾ですが,これによって単数か複数かが区別されていたのです.

その後,後期古英語から中英語にかけて,この複数語尾の -n 音は弱まり,ゆっくりと消えていきました.結果として,複数形は単数形に飲み込まれるようにして合一してしまったのです.

以上をまとめしょう.古英語の動詞の接続法には,数によって -n 語尾の有無が変わる程度でしたが,一応,人称変化は存在していたといえます.しかし,その -n 語尾が中英語にかけて弱化・消失したために,数にかかわらず同一の形態が用いられるようになったということです.現代英語の仮定法に人称変化がないのは,千年ほど前にゆっくりと起こった小さな音変化の結果だったのです.

2019-04-13 Sat

■ #3638.『英語教育』の連載第2回「なぜ不規則な複数形があるのか」 [notice][hel_education][elt][sobokunagimon][plural][number][rensai][link]

『英語教育』の英語史連載記事「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ」が,前回の4月号より始まっています.昨日発売された5月号では,第2回の記事として「なぜ不規則な複数形があるのか」という素朴な疑問を取りあげています.是非ご一読ください.

名詞複数形の歴史は,私のズバリの専門分野です(博士論文のタイトルは The Development of the Nominal Plural Forms in Early Middle English でした).そんなこともあり,本ブログでも複数形の話題は plural の記事で様々に取りあげてきました.今回の連載記事の内容ととりわけ関係するブログ記事へのリンクを以下に張っておきます.

・ 「#946. 名詞複数形の歴史の概要」 ([2011-11-29-1])

・ 「#146. child の複数形が children なわけ」 ([2009-09-20-1])

・ 「#157. foot の複数はなぜ feet か」 ([2009-10-01-1])

・ 「#12. How many carp!」 ([2009-05-11-1])

・ 「#337. egges or eyren」 ([2010-03-30-1])

・ 「#3298. なぜ wolf の複数形が wolves なのか? (1)」 ([2018-05-08-1])

・ 「#3588. -o で終わる名詞の複数形語尾 --- pianos か potatoes か?」 ([2019-02-22-1])

・ 「#3586. 外来複数形」 ([2019-02-20-1])

英語の複数形の歴史というテーマについても,まだまだ研究すべきことが残っています.英語史は奥が深いです.

2017年に連載した「現代英語を英語史の視点から考える」の第1回「「ことばを通時的にみる 」とは?」でも複数形の歴史を扱いましたので,そちらも是非ご一読ください.

・ 堀田 隆一 「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ 第2回 なぜ不規則な複数形があるのか」『英語教育』2019年5月号,大修館書店,2019年4月12日.62--63頁.

2018-06-10 Sun

■ #3331. 印欧祖語からゲルマン祖語への動詞の文法範疇の再編成 [indo-european][germanic][category][voice][mood][tense][aspect][number][person][exaptation][sanskrit][gothic]

Lass (151--53) によると,Sanskrit の典型的な動詞には,時制,人称,数のカテゴリーに応じて126の定形がある.ゲルマン諸語のなかで最も複雑な屈折を示す Gothic では,22の屈折形がある.ゲルマン諸語のなかでもおよそ典型的といってよい古英語は,最大で8つの屈折形を示す.なお,現代英語では最大でも3つだ.この事実は,示唆的だろう.時代を経るごとに,屈折の種類が減ってきているのである.

印欧祖語では,区別されていた文法カテゴリーとその中味は以下の通り.

・ 態 (voice) :能動態 (active) ,中動態 (middle)

・ 法 (mood) :直説法 (indicative) ,接続法 (subjunctive),祈願法 (optative) ,命令法 (imperative)

・ 相・時制 (aspect/tense) :現在 (present) ,無限定過去 (aorist) ,完了 (perfect)

・ 数 (number) :単数 (singular) ,両数 (dual) ,複数 (plural)

・ 人称 (person) :1人称 (first) ,2人称 (second) ,3人称 (third)

これらのカテゴリーについて,印欧祖語からゲルマン祖語への再編成の様子を略述しよう.

態のカテゴリーについては,印相祖語の能動態 vs 中動態の区別は,ゲルマン祖語では(能動態) vs (受動態と再帰態)とでもいうべき区別に再編成された.

法のカテゴリーに関しては,印欧祖語の4つの区分は,北・西ゲルマン語派では,直説法,接続法,命令法の3区分,あるいはさらに融合が進み,古英語では直説法と接続法の2区分へと再編成された.

印欧祖語の時制・相のカテゴリーは,基本的には相に基づいたものと考えられている.議論はあるようだが,主として印欧祖語の「完了」が,ゲルマン祖語における「過去」に再編成されたようだ.結果として,ゲルマン祖語では,この新生「過去」と,現在を包含する「非過去」との,時制に基づく2分法が確立する.

数のカテゴリーは,古英語では両数が人称代名詞にわずかに残存しているものの,概論的にいえば,単数と複数の2区分に再編成された.この再編成については,「#2152. Lass による外適応」 ([2015-03-19-1]),「#2153. 外適応によるカテゴリーの組み替え」 ([2015-03-20-1]) を参照されたい.

最後に,人称のカテゴリーについては,現代英語の「3単現の -s」にも象徴されるように,およそ3区分法が現代まで受け継がれている.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2018-05-11 Fri

■ #3301. なぜ wolf の複数形が wolves なのか? (4) [sobokunagimon][genitive][plural][consonant][phonetics][fricative_voicing][analogy][number][inflection][paradigm][clitic]

3日間にわたり標題の話題を発展させてきた ([2018-05-08-1], [2018-05-09-1], [2018-05-10-1]) .今回は第4弾(最終回)として,この問題にもう一ひねりを加えたい.

wolves (および間接的に wives)の背景には,古英語の男性強変化名詞の屈折パターンにおいて,複数主格(・対格)形として -as が付加されるという事情があった.これにより古英語 wulf が wulfas となり,f は有声音に挟まれるために有声化するのだと説明してきた.wīf についても,本来は中性強変化という別のグループに属しており,自然には wives へと発達しえないが,後に wulf/wulfas タイプに影響され,類推作用 (analogy) により wives へと帰着したと説明すれば,それなりに納得がいく.

このように,-ves の複数形については説得力のある歴史的な説明が可能だが,今回は視点を変えて単数属格形に注目してみたい.機能的には現代英語の所有格の -'s に連なる屈折である.以下,単数属格形を強調しながら,古英語 wulf と wīf の屈折表をあらためて掲げよう.

|

|

両屈折パターンは,複数主格・対格でこそ異なる語尾をとっていたが,単数属格では共通して -es 語尾をとっている.そして,この単数属格 -es を付加すると,語幹末の f は両サイドを有声音に挟まれるため,発音上は /v/ となったはずだ.そうだとするならば,現代英語でも単数所有格は,それぞれ *wolve's, *wive's となっていてもよかったはずではないか.ところが,実際には wolf's, wife's なのである.複数形と単数属格形は,古英語以来,ほぼ同じ音韻形態的条件のもとで発展してきたはずと考えられるにもかかわらず,なぜ結果として wolves に対して wolf's,wives に対して wife's という区別が生じてしまったのだろうか.(なお,現代英語では所有格形に ' (apostrophe) を付すが,これは近代になってからの慣習であり,見た目上の改変にすぎないので,今回の議論にはまったく関与しないと考えてよい(「#582. apostrophe」 ([2010-11-30-1]) を参照).)

1つには,属格標識は複数標識と比べて基体との関係が疎となっていったことがある.中英語から近代英語にかけて,属格標識の -es は屈折語尾というよりは接語 (clitic) として解釈されるようになってきた(cf. 「#1417. 群属格の発達」 ([2013-03-14-1])).換言すれば,-es は形態的な単位というよりは統語的な単位となり,基体と切り離してとらえられるようになってきたのである.それにより,基体末尾子音の有声・無声を交替させる動機づけが弱くなっていったのだろう.こうして属格表現において基体末尾子音は固定されることとなった.

それでも中英語から近代英語にかけて,いまだ -ves の形態も完全に失われてはおらず,しばしば類推による無声の変異形とともに並存していた.Jespersen (§16.51, pp. 264--65) によれば,Chaucer はもちろん Shakespeare に至っても wiues などが規則的だったし,それは18世紀終わりまで存続したのだ.calues も Shakespeare で普通にみられた.特に複合語の第1要素に属格が用いられている場合には -ves が比較的残りやすく,wive's-jointure, staves-end, knives-point, calves-head などは近代でも用いられた.

しかし,これらとて現代英語までは残らなかった.属格の -ves は,標準語ではついえてしまったのである.いまや複数形の wolves など少数の語形のみが,古英語の音韻規則の伝統を引く最後の生き残りとして持ちこたえている.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2018-05-10 Thu

■ #3300. なぜ wolf の複数形が wolves なのか? (3) [sobokunagimon][plural][consonant][phonetics][fricative_voicing][analogy][number][inflection]

2日間の記事 ([2018-05-08-1], [2018-05-09-1]) で,標記の素朴な疑問を題材に,英語史の奥深さに迫ってきた.今回は第3弾.

古英語の wulf (nom.acc.sg.)/wulfas (nom.acc.pl) を原型とする wolf (sg.)/wolves (pl.) という単複ペアのモデルが,類推作用 (analogy) によって,歴史的には wulf と異なる屈折クラスに属する,語尾に -f をもつ他の名詞にも拡がったことを見た.leaf/leaves や life/lives はそれにより説明される.

しかし,現代英語の現実を眺めると,語尾に -f をもつ名詞のすべてが複数形において -ves を示すわけではない.例えば,roof/roofs, belief/beliefs などが思い浮かぶが,これらは完全に「規則的」な複数形を作っている.とりわけ roof などは,古英語では hrōf という形態で,まさに wulf と同じ男性強変化グループに属していたのであり,正統には古英語で実際に用いられていた hrōfas が継承され,現在は *rooves となっていて然るべきなのである.ところが,そうなっていない(しかし,rooves については以下の表も参照).

ここで起こったことは,先に挙げたのとは別種の類推作用である.wife などの場合には,類推のモデルとなったのは wolf/wolves のタイプだったのだが,今回の roof を巻き込んだ類推のモデルは,もっと一般的な,例えば stone/stones, king/kings といったタイプであり,語尾に -s をつければ済むというという至極単純なタイプだったのである.同様にフランス借用語の grief, proof なども,もともとのフランス語での複数形の形成法が単純な -s 付加だったこともあり,後者のモデルを後押し,かつ後押しされたことにより,現在その複数形は griefs, proofs となっていると理解できる.

語尾に -f をもつ名詞群が,類推モデルとして wolf/wolves タイプを採用したか,あるいは stone/stones タイプを採用したかを決める絶対的な基準はない.個々の名詞によって,振る舞いはまちまちである.歴史的に両タイプの間で揺れを示してきた名詞も少なくないし,現在でも -fs と -ves の両複数形がありうるという例もある.類推作用とは,それくらいに個々別々に作用するものであり,その意味でとらえどころのないものである.

一昨日の記事 ([2018-05-08-1]) では,wolf の複数形が wolves となる理由を聞いてスッキリしたかもしれないが,ここにきて,さほど単純な問題ではなさそうだという感覚が生じてきたのではないだろうか.現代英語の現象を英語史的に考えていくと,往々にして問題がこのように深まっていく.

以下,主として Jespersen (Modern, §§16.21--16.25 (pp. 258--621)) に基づき,語尾に -f を示すいくつかの語の,近現代における複数形を挙げ,必要に応じてコメントしよう(さらに多くの例,そしてより詳しくは,Jespersen (Linguistic, 374--75) を参照).明日は,懲りずに第4弾.

| 単数形 | 複数形 | コメント |

|---|---|---|

| beef | beefs/beeves | |

| belief | beliefs | 古くは believe (sg.)/believes (pl.) .この名詞は,OE ġelēafa と関連するが,語尾の母音が脱落して,f が無声化した.16世紀頃には believe (v.) と belief (n.) が形態上区別されるようになり,名詞 -f が確立したが,これは grieve (v.)/grief (n.), prove (v.)/proof (n.) などの類推もあったかもしれない. |

| bluff | bluffs | |

| brief | briefs | |

| calf | calves | |

| chief | chiefs | |

| cliff | cliffs | 古くは cleves (pl.) も. |

| cuff | cuffs | |

| delf | delves | 方言として delfs (pl.) も.また,標準英語で delve (sg.) も. |

| elf | elves | まれに elfs (pl.) や elve (sg.) も. |

| fief | fiefs | |

| fife | fifes | |

| gulf | gulfs | |

| half | halves | 「半期(学期)」の意味では halfs (pl.) も. |

| hoof | hoofs | 古くは hooves (pl.) . |

| knife | knives | |

| leaf | leaves | ただし,ash-leafs (pl.) "ash-leaf potatoes". |

| life | lives | 古くは lyffes (pl.) など. |

| loaf | loaves | |

| loof | looves/loofs | loove (sg.) も. |

| mastiff | mastiffs | 古くは mastives (pl.) も. |

| mischief | mischiefs | 古くは mischieves (pl.) も. |

| oaf | oaves/oafs | |

| rebuff | rebuffs | |

| reef | reefs | |

| roof | roofs | イングランドやアメリカで rooves (pl.) も. |

| safe | safes | |

| scarf | scarfs | 18世紀始めからは scarves (pl.) も. |

| self | selves | 哲学用語「自己」の意味では selfs (pl.) も. |

| sheaf | sheaves | |

| shelf | shelves | |

| sheriff | sheriffs | 古くは sherives (pl.) も. |

| staff | staves/staffs | 「棒きれ」の意味では staves (pl.) .「人々」の意味では staffs (pl.) .stave (sg.) も. |

| strife | strifes | |

| thief | thieves | |

| turf | turfs | 古くは turves (pl.) も. |

| waif | waifs | 古くは waives (pl.) も. |

| wharf | warfs | 古くは wharves (pl.) も |

| wife | wives | 古くは wyffes (pl.) など.housewife "hussy" でも housewifes (pl.) だが,Austen ではこの意味で huswifes も. |

| wolf | wolves |

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Linguistica: Selected Papers in English, French and German. Copenhagen: Levin & Munksgaard, 1933.

2018-05-09 Wed

■ #3299. なぜ wolf の複数形が wolves なのか? (2) [sobokunagimon][plural][consonant][oe][phonetics][fricative_voicing][analogy][number][conjugation][inflection][paradigm]

昨日の記事 ([2018-05-08-1]) で,wolf (sg.) に対して wolves (pl.) となる理由を古英語の音韻規則に照らして説明した.これにより,関連する他の -f (sg.)/ -ves (pl.) の例,すなわち calf/calves, elf/elves, half/halves, leaf/leaves, life/lives, loaf/loaves, knife/knives, self/selves, sheaf/sheaves, shelf/shelves, thief/thieves, wife/wives などもきれいに説明できると思うかもしれない.しかし,英語史はそれほどストレートで美しいものではない.言語という複雑なシステムがたどる歴史は,一癖も二癖もあるのが常である.

例えば,wife (sg.)/wives (pl.) の事例を取り上げよう.この名詞は,古英語では wīf という単数主格(見出し語)形を取っていた(当時の語義は「妻」というよりも「女性」だった).f は,左側に有声母音こそあれ右側には何もないので,「有声音に挟まれている」わけではなく,デフォルトの /f/ で発音される.そして,次に来る説明として予想されるのは,「ところが,複数主格(・対格)形では wīf に -as の屈折語尾が付くはずであり,f は有声音に挟まれることになるから,/v/ と有声音化するのだろう」ということだ.

しかし,そうは簡単にいかない.というのは,wulf の場合はたまたま男性強変化というグループに属しており,昨日の記事で掲げた屈折表に従うことになっているのだが,wīf は中性強変化というグループに属する名詞であり,古英語では異なる屈折パターンを示していたからだ.以下に,その屈折表を掲げよう.

| (中性強変化名詞) | 単数 | 複数 |

|---|---|---|

| 主格 | wīf | wīf |

| 対格 | wīf | wīf |

| 属格 | wīfes | wīfa |

| 与格 | wīfe | wīfum |

中性強変化の屈折パターンは上記の通りであり,このタイプの名詞では複数主格(・対格)形は単数主格(・対格)形と同一になるのである.現代英語に残る単複同形の名詞の一部 (ex. sheep) は,古英語でこのタイプの名詞だったことにより説明できる(「#12. How many carp!」 ([2009-05-11-1]) を参照).とすると,wīf において,単数形の /f/ が複数形で /v/ に変化する筋合いは,当然ながらないことになる./f/ か /v/ かという問題以前に,そもそも複数形で s など付かなかったのだから,現代英語の wives という形態は,上記の古英語形からの「直接の」発達として理解するわけにはいかなくなる.実は,これと同じことが leaf/leaves と life/lives にも当てはまる.それぞれの古英語形 lēaf と līf は,wīf と同様,中性強変化名詞であり,複数主格(・対格)形はいわゆる「無変化複数」だったのだ.

では,なぜこれらの名詞の複数形が,現在では wolves よろしく leaves, lives となっているのだろうか.それは,wīf, lēaf, līf が,あるときから wulf と同じ男性強変化名詞の屈折パターンに「乗り換えた」ことによる.wulf のパターンは確かに古英語において最も優勢なパターンであり,他の多くの名詞はそちらに靡く傾向があった.比較的マイナーな言語項が影響力のあるモデルにしたがって変化する作用を,言語学では類推作用 (analogy) と呼んでいるが,その典型例である(「#946. 名詞複数形の歴史の概要」 ([2011-11-29-1]) を参照).この類推作用により,歴史的な複数形(厳密には複数主格・対格形)である wīf, lēaf, līf は,wīfas, lēafas, līfas のタイプへと「乗り換えた」のだった.その後の発展は,wulfas と同一である.

ポイントは,現代英語の複数形の wives, leaves, lives を歴史的に説明しようとする場合,wolves の場合ほど単純ではないということだ.もうワン・クッション,追加の説明が必要なのである.ここでは,古英語の「摩擦音の有声化」という音韻規則は,まったく無関係というわけではないものの,あくまで背景的な説明というレベルへと退行する.本音をいえば,昨日と今日の記事の標題には,使えるものならば wolf (sg.)/wolves よりも wife (sg.)/wives (pl.) を使いたいところではある.wife/wives のほうが頻度も高いし,両サイドの有声音が母音という分かりやすい構成なので,説明のための具体例としては映えるからだ.だが,上記の理由で,摩擦音の有声化の典型例として前面に出して使うわけにはいかないのである.英語史上,ちょっと「残念な事例」ということになる.

とはいえ,wives は,類推作用というもう1つのきわめて興味深い言語学的現象に注意を喚起してくれた.これで英語史の奥深さが1段深まったはずだ.明日は,関連する話題でさらなる深みへ.

2018-05-08 Tue

■ #3298. なぜ wolf の複数形が wolves なのか? (1) [sobokunagimon][plural][consonant][oe][phonetics][fricative_voicing][number][v][conjugation][inflection][paradigm]

標題は,「#1365. 古英語における自鳴音にはさまれた無声摩擦音の有声化」 ([2013-01-21-1]) で取り上げ,「#1080. なぜ five の序数詞は fifth なのか?」 ([2012-04-11-1]) や「#2948. 連載第5回「alive の歴史言語学」」 ([2017-05-23-1]) でも具体的な例を挙げて説明した問題の,もう1つの応用例である.wolf の複数形が wolves となるなど,単数形 /-f/ が複数形 /-vz/ へと一見不規則に変化する例が,いくつかの名詞に見られる.例えば,calf/calves, elf/elves, half/halves, leaf/leaves, life/lives, loaf/loaves, knife/knives, self/selves, sheaf/sheaves, shelf/shelves, thief/thieves, wife/wives などである.これはどういった理由だろうか.

古英語では,無声摩擦音 /f, θ, s/ は,両側を有声音に挟まれると自らも有声化して [v, ð, z] となる音韻規則が確立していた.この規則は,適用される音環境の条件が変化することもあれば,方言によってもまちまちだが,中英語以降でもしばしばお目にかかるルールである.必ずしも一貫性を保って適用されてきたわけではないものの,ある意味で英語史を通じて現役活動を続けてきた根強い規則といえる.摩擦音の有声化 (fricative_voicing) などという名前も与えられている.

今回の標題に照らし,以下では /f/ の場合に説明を絞ろう.wolf (狼)は古英語では wulf という形態だった.この名詞は男性強変化というグループに属する名詞で,格と数に応じて以下のように屈折した.

| (男性強変化名詞) | 単数 | 複数 |

|---|---|---|

| 主格 | wulf | wulfas |

| 対格 | wulf | wulfas |

| 属格 | wulfes | wulfa |

| 与格 | wulfe | wulfum |

単数主格(・対格)の形態,いわゆる見出し語形では wulf には屈折語尾がつかず,f の立場からみると,確かに左側に有声音の l はあるものの右側には何もないので「有声音に挟まれている」環境ではない.したがって,この f はそのままデフォルトの /f/ で発音される.しかし,表のその他の6マスでは,いずれも母音で始まる何らかの屈折語尾が付加しており,問題の f は有声音に挟まれることになる.ここで摩擦音の有声化規則が発動し,f は発音上 /f/ から /v/ へと変化する.古英語では綴字上 <f> と <v> を使い分ける慣習はない(というよりも <v> の文字が存在しない)ので,文字上は無声であれ有声であれ <f> のままである(文字 <v> の発達については「#373. <u> と <v> の分化 (1)」 ([2010-05-05-1]),「#374. <u> と <v> の分化 (2)」 ([2010-05-06-1]) を参照).この屈折表の複数主格(・対格)の wulfas が,その後も生き残って現代英語における「複数形」として伝わったわけだ.この複数形では,綴字こそ wolves と書き改められたが,発音上は古英語の /f/ ならぬ /v/ がしっかり残っている.

このように,古英語の音韻規則を念頭におけば,現代の wolf/wolves の関係はきれいに説明できる.現代英語としてみると確かに「不規則」と呼びたくなる関係だが,英語史を参照すれば,むしろ「規則的」なのである.このような気づきこそが,英語史を学ぶ魅力であり,英語史の奥深さといえる.

しかし,英語史の奥深さはここで止まらない.上の説明で納得して終わり,ではない.ここから発展してもっとおもしろく,不可思議に展開していくのが英語史である.新たな展開については明日以降の記事で.

2017-10-21 Sat

■ #3099. 連載第10回「なぜ you は「あなた」でもあり「あなたがた」でもあるのか?」 [link][notice][personal_pronoun][number][t/v_distinction][category][rensai][sobokunagimon][fetishism]

昨日10月20日付けで,英語史連載企画「現代英語を英語史の視点から考える」の第10回の記事「なぜ you は「あなた」でもあり「あなたがた」でもあるのか?」が公開されました.

本文でも述べているように,この素朴な疑問にも「驚くべき歴史的背景が隠されて」おり,解説を通じて「英語史のダイナミズム」を感じられると思います.2人称代名詞を巡る諸問題については,これまでも本ブログで書きためてきました.以下に関連記事へのリンクを張りますので,どうぞご覧ください.

[ 各時代,各変種の人称代名詞体系 ]

・ 「#180. 古英語の人称代名詞の非対称性」 ([2009-10-24-1])

・ 「#181. Chaucer の人称代名詞体系」 ([2009-10-25-1])

・ 「#196. 現代英語の人称代名詞体系」 ([2009-11-09-1])

・ 「#529. 現代非標準変種の2人称複数代名詞」 ([2010-10-08-1])

・ 「#333. イングランド北部に生き残る thou」 ([2010-03-26-1])

[ 文法範疇とフェチ ]

・ 「#1449. 言語における「範疇」」 ([2013-04-15-1])

・ 「#2853. 言語における性と人間の分類フェチ」 ([2017-02-17-1])

[ 親称と敬称の対立 (t/v_distinction) ]

・ 「#167. 世界の言語の T/V distinction」 ([2009-10-11-1])

・ 「#185. 英語史とドイツ語史における T/V distinction」 ([2009-10-29-1])

・ 「#1033. 日本語の敬語とヨーロッパ諸語の T/V distinction」 ([2012-02-24-1])

・ 「#1059. 権力重視から仲間意識重視へ推移してきた T/V distinction」 ([2012-03-21-1])

・ 「#1126. ヨーロッパの主要言語における T/V distinction の起源」 ([2012-05-27-1])

・ 「#1552. T/V distinction と face」 ([2013-07-27-1])

・ 「#2107. ドイツ語の T/V distinction の略史」 ([2015-02-02-1])

[ thou, ye, you の競合 ]

・ 「#673. Burnley's you and thou」 ([2011-03-01-1])

・ 「#1127. なぜ thou ではなく you が一般化したか?」 ([2012-05-28-1])

・ 「#1336. なぜ thou ではなく you が一般化したか? (2)」 ([2012-12-23-1])

・ 「#1865. 神に対して thou を用いるのはなぜか」 ([2014-06-05-1])

・ 「#291. 二人称代名詞 thou の消失の動詞語尾への影響」 ([2010-02-12-1])

・ 「#2320. 17世紀中の thou の衰退」 ([2015-09-03-1])

・ 「#800. you による ye の置換と phonaesthesia」 ([2011-07-06-1])

・ 「#781. How d'ye do?」 ([2011-06-17-1])

[ 敬称の you の名残り ]

・ 「#440. 現代に残る敬称の you」 ([2010-07-11-1])

・ 「#1952. 「陛下」と Your Majesty にみられる敬意」 ([2014-08-31-1])

・ 「#3095. Your Grace, Your Highness, Your Majesty」 ([2017-10-17-1])

[ you の発音と綴字 ]

・ 「#2077. you の発音の歴史」 ([2015-01-03-1])

・ 「#2234. <you> の綴字」 ([2015-06-09-1])

2017-03-17 Fri

■ #2881. 中英語期の複数2人称命令形語尾の消失 [imperative][verb][inflection][number][agreement]

標題の言語変化について,「#2475. 命令にはなぜ動詞の原形が用いられるのか」 ([2016-02-05-1]) と「#2476. 英語史において動詞の命令法と接続法が形態的・機能的に融合した件」 ([2016-02-06-1]) で少しく触れた.屈折語尾の弱化・消失は,とりわけ古英語期から中英語期にかけて起こった英語史上の大変化だが,動詞命令形の屈折語尾については,周辺的で影が薄いためか,あまり本格的な記述がなされていないように思われる.しかし,この問題は動詞における「数の一致」の標示手段に関する問題として統語形態上の重要性をもつし,中英語期において2人称の「数」はいわゆる t/v_distinction というポライトネスに直結する問題でもあるから,見かけ以上に追究する価値のあるテーマなのではないか.

この件について,中尾 (162) に当たってみると,次のようにあった.

命令法――単・複数

単数は {-ø} (sing/her (=hear)).ただし,母音,<h> の前では -e も起こる.複数接辞は直説法・複数のそれとほぼ同じ方言分布を示す ({-es, -eth}).ただし主語表現を直続させるときは {-e} (helpe ye).15世紀半ばごろから {-ø} が複数の範疇にも進出して来るようになる(AncrR にすでにその例が起こる).

p. 277 にも関連する記述があった.

命令法は屈折接辞 (helpes, helpeth) または語順 (helpe ye) によりあらわされる.前者は主語が複数,あるいは「丁重な呼び掛け」の単数の場合に用いられる.主語表現を伴うことはきわめてまれである.後者は単数および複数主語の場合に用いられる.

ここから,中英語期の命令法・複数は,(1) 屈折語尾について直説法・複数と同じ方言分布を示すということ,(2) 「丁重な単数」の2人称にも用いられたこと,(3) 15世紀半ば頃からゼロ屈折に置換されるようになってきたことが分かる.しかし,これ以上の詳細な記述はない.

後期中英語の様々な方言や異写本テキストなどで分布を調査したり,さらに時代を遡って初期中英語辺りの分布を見てみること等が必要かもしれない.

・中尾 俊夫 『英語史 II』 英語学大系第9巻 大修館書店,1972年.

2015-12-28 Mon

■ #2436. 形容詞複数屈折の -e が後期中英語まで残った理由 [adjective][ilame][inflection][final_e][plural][number][category][agreement]

この2日間,「#2434. 形容詞弱変化屈折の -e が後期中英語まで残った理由」 ([2015-12-26-1]) と「#2435. eurhythmy あるいは "buffer hypothesis" の適用可能事例」 ([2015-12-27-1]) の記事で,Inflectional Levelling of Adjectives in Middle English (ilame) について考察した.#2434の記事で話題にしたのは,実は形容詞の「単数」の弱変化屈折として生起する -e のことであって,同じように -e 語尾が遅くまでよく保たれていた形容詞の「複数」の屈折については触れていなかった.「#532. Chaucer の形容詞の屈折」 ([2010-10-11-1]) に挙げた屈折表から分かるように,複数においては,弱変化と強変化の区別なく,原則としてあらゆる統語環境において,単音節形容詞は -e を取ったのである.#2435の記事で扱った "eurhythmy" や "buffer hypothesis" は,形容詞の用いられる統語環境の差異を前提とした仮説だったが,複数の場合には上記のように統語環境が不問となるので,なぜ複数屈折の -e がよく保持されたのかについては,別の問題として扱わなければならない.

この問題に対して,基本的には,単複を区別する数 (number) という文法範疇 (category) が英語の言語体系においてよく保守されてきたからである,と答えておきたい.名詞や代名詞においては,印欧祖語から古英語を経て現代英語に至るまで一貫して数の区別は保たれてきたし,主語と動詞の一致 (concord) においても,数という範疇は常に関与的であり続けてきた.形容詞では,結果的に近代英語期以降,数の標示をしなくなったことは事実だが,初期中英語期の激しい語尾の水平化と消失の潮流のなかを生き延び,後期中英語まで複数語尾 -e をよく保ってきたということは,英語の言語体系において数という範疇が根深く定着していたことを示すものだろう.この点で,私は以下の Minkova (329) の見解に同意する.

My analysis assumes that the status of the final -e as a grammatical marker is stable in the plural. Yet in maintaining the syntactically based strong-weak distinction in the singular, it is no longer independently viable. As a plural signal it is still salient, possibly because of the morphological stability of the category of number in all nouns, so that there is phrase-internal number concord within the adjectival NPs. Another argument supporting the survival of plural -e comes from the continuing number agreement between subject NPs and the predicate, in other words the singular-plural opposition continues to be realized across the system.

では,なぜ英語では数という文法範疇がここまで根強く残ろうとした(そして現在でも残っている)のか.これは言語における文法範疇の一般的な問題であり,究極の問題というべきである.これについての議論は,拙著の "Syntactic Agreement" と題する6.6節 (141--44) で触れているので参照されたい.

・ Minkova, Donka. "Adjectival Inflexion Relics and Speech Rhythm in Late Middle and Early Modern English." Papers from the 5th International Conference on English Historical Linguistics, Cambridge, 6--9 April 1987. Ed. Sylvia Adamson, Vivien Law, Nigel Vincent, and Susan Wright. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1990. 313--36.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi. The Development of the Nominal Plural Forms in Early Middle English. Hituzi Linguistics in English 10. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo, 2009.

2015-03-12 Thu

■ #2145. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (6) [verb][conjugation][emode][number][agreement][3pp][nptr]

標題については 3pp の各記事で取り上げてきたが,関連する記述をもう1つ見つけたので,以下に記しておきたい.「#1301. Gramley の英語史概説書のコンパニオンサイト」 ([2012-11-18-1]) と「#2007. Gramley の英語史概説書の目次」 ([2014-10-25-1]) で紹介した Gramley (136--37) からの引用である.

Third person {-s} vs. {-(e)th} is a further inflectional point. This distinction is one of the most noticeable in this period [EModE], and it may be used as evidence of the influence of Northern on Southern English. In ME Northerners used the ending {-s} where Southerners used {-(e)th}. In each case the respective inflection could be used in both the third person singular present tense as well as in the whole of the plural . . . . While zero became normal in the plural, in the third person singular present tense there was no such move, and the two forms were in competition with each other both in colloquial London speech and in the written language.

同英語史書のコンパニオンサイトより,6章のための補足資料 (p. 8) に,さらに詳しい解説が載っており有用である.また,そこでは Northern Subject Rule (= Northern Present Tense Rule; cf. nptr, 「#689. Northern Personal Pronoun Rule と英文法におけるケルト語の影響」 ([2011-03-17-1])) にも触れられており,その関連で Lass (166, 185) と Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg (283, 312) への言及もある.

NPTR が南部において適用された結果と思われる複現の -s の例を挙げておこう.

・ they laugh that wins (F1--3, Q1--3; win F4) (Shakespeare, Othello 4.1.121)

・ whereby they make their pottage fat, and therewith driues out the rest with more content. (Deloney, Jack of Newbury 72)

・ For if neither they can doo that they promise & wantes greatest good (Elizabeth, Boethius 48.11)

・ Well know they what they speak that speaks (F1; speak Q) so wisely (Shakespeare, Troilus 3.2.145)

・ when sorrows comes (F1), they come not single spies. (Shakespeare, Hamlet 4.5.73)

・ As surely as your feet hits (F1) the ground they step on (Shakespeare, Twelfth Night 3.4.265)

Shakespeare では版によって複現の -s が現われたり消えたりする例が見られることから,そこには文体的あるいは通時的な含意がありそうである.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 56--186.

・ Nevalainen, T. and H. Raumolin-Brunberg. "The Changing Role of London on the Linguistic Map of Tudor and Stuart England." The History of English in a Social Context: A Contribution to Historical Sociolinguistics. Ed. D. Kastovsky and A. Mettinger. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2000. 279--337.

2014-08-01 Fri

■ #1922. singular they を取り締まる規範文法 (3) [singular_they][prescriptive_grammar][gender][number][personal_pronoun][language_myth]

一昨日 ([2014-07-30-1]) ,昨日 ([2014-07-31-1]) と続いての話題.口語において中英語期より普通に用いられてきた不定一般人称に対する singular they は,18世紀の規範文法の隆盛に従って,公に非難されるようになった.しかし,すでに早く16世紀より,性を問わない he の用法を妥当とする考え方は芽生えていた.Bodine (134) によると,T. Wilson は1553年の Arte of rhetorique で男性形を優勢とする見解を明示している.

Some will set the Carte before the horse, as thus. My mother and my father are both at home, even as thoughe the good man of the house ware no breaches, or that the graye Mare were the better Horse. And what thoughe it often so happeneth (God wotte the more pitte) yet in speaking at the leaste, let us kepe a natural order, and set the man before the woman for maners Sake. (1560 ed.: 189)

同様に,Bodine (134) によると,7世紀には J. Pool が English accidence (1646: 21) で同様の見解を示している.

The Relative agrees with the Antecedent in gender, number, and person. . . The Relative shall agree in gender with the Antecedent of the more worthy gender: as, the King and the Queen whom I honor. The Masculine gender is more worthy than the Feminine.

しかし,Bodine (135) は,不定一般人称の he の本格的な擁護の事例として最初期のものは Kirby の A new English grammar (1746) であると見ている.Kirby は88の統語規則を規範として掲げたが,その Rule 21 が問題の箇所である.

The masculine Person answers to the general Name, which comprehends both Male and Female; as Any Person, who knows what he says. (117)

以降,この見解は広く喧伝されることになる.L. Murray の English grammar (1795) をはじめとする後の規範文法家たちはこぞって he を支持し,they をこき下ろしてきた.その潮流の絶頂が,Act of Parliament (1850) だろう.これは,he or she を he で置き換えるべしとした法的な言及である.

さて,Kirby の Rule 21 に続く Rule 22 は,性ではなく数の問題を扱っているが,今回の議論とも関わってくるので紹介しておく.これは一般不定人称において単数と複数はお互いに交換することができるというルールであり,例えば "The Life of Man" と "The Lives of Men" は同値であるとするものだ.しかし,Bodine (136) は,Kirby の Rule 21, 22 や Act of Parliament には議論上の欠陥があると指摘する.

Thus, the 1850 Act of Parliament and Kirby's Rules 21-2 manifest their underlying androcentric values and world-view in two ways. First, linguistically analogous phenomena (number and gender) are handled very differently (singular or plural as generic vs. masculine only as generic). Second, the precept just being established is itself violated in not allowing singular 'they', since if the plural 'shall be deemed and taken' to include the singular, then surely 'they' includes 'she' and 'he' and 'she or he'.

これは,昨日の記事 ([2014-07-31-1]) で取り上げた議論にも通じる.不定一般人称の he の用法とは,近代という時代によって作られ,守られてきた一種の神話であるといってもよいかもしれない.

・ Bodine, Ann. "Androcentrism in Prescriptive Grammar: Singular 'they', Sex-Indefinite 'he,' and 'he or she'." Language in Society 4 (1975): 129--46.

2014-07-31 Thu

■ #1921. singular they を取り締まる規範文法 (2) [singular_they][prescriptive_grammar][gender][number][personal_pronoun][political_correctness][t/v_distinction]

昨日の記事「#1920. singular they を取り締まる規範文法 (1)」 ([2014-07-30-1]) に引き続いての話題.singular they を巡る議論は様々あるが,実際にはこれは文法的な問題である以上に性に関する社会的な問題であると考える理由がある.このことを理解するためには,英語で不定一般人称を既存の人称代名詞で表現しようとする際に,性と数に関わる問題が生じざるを得ないことを了解しておく必要がある.

「#275. 現代英語の三人称単数共性代名詞」 ([2010-01-27-1]) や「#1054. singular they」 ([2012-03-16-1]) でもいくつか例文を示したが,"If anyone is interested in this blog, ( ) can always contact me." のような文において,if 節の主語 anyone を照応する人称代名詞を括弧の箇所に補おうとすると,英語では既存の人称代名詞として he, she, he or she, they のいずれかが候補となる.しかし,いずれも性あるいは数の一致に関する問題が生じ,完璧な解決策はない.単数人称代名詞 he あるいは she にすると,単数 anyone との照応にはふさわしいが,不定であるはずの性に,男性あるいは女性のいずれかを割り当ててしまうことになり,性の問題が残る.he or she (あるいは s/he などの類似表現)は性と数の両方の問題を解決できるが,不自然でぎこちない表現とならざるをえない.一方,they は男性か女性かを明示しない点で有利だが,一方で数の不一致という問題が残る.つまり,he と she は性の問題を残し,he or she は表現としてのぎこちなさの問題を残し,they は数の問題を残す.

だが,性か数のいずれかを尊重すれば他方が犠牲にならざるを得ない状況下で,どちらの選択肢を採用するかという問題が生じる.はたして,どちらの解決策も同じ程度に妥当と考えられるだろうか.一見すると両解決策の質は同じように見えるが,実は重要な差異がある.数は社会性を帯びていないが,性は社会性を帯びているということだ (cf. social gender) .単数と複数の区別は原則として指示対象のモノ関する属性であり,自然で論理的な区別である.単数を複数で置き換えようが,複数を単数で置き換えようが,特に社会的な影響はない(数の犠牲ということでいえば,元来の thou の領域に ye/you が侵入してきた T/V distinction の事例も参照されたい).ところが,性は原則として指示対象のヒトの属性であり,男性を女性で代表させたり,女性を男性で代表させたりすることには,社会的な不均衡や不平等が含意される.Bodine (133) のいうように,"the two [number and sex] . . . are not socially analogous, since number lacks social significance" である.

不定一般人称を he で代表させるということは,(1) 社会性を含意しない数よりも社会性を含意する性を標示することをあえて選び,(2) その際に女性形でなく男性形をあえて選ぶ,という2つの意図的な選択の結果としてしかありえない.18世紀以来の規範文法家は,この2つの「あえて」を冒し,he の使用を公然と推挙してきたのである.逆に,口語において歴史上普通に行われていた不定一般人称を they で代表させるやり方は,(1) 社会性を含意しない数の厳密な区別を犠牲にし,(1) 社会性を含意する性を標示しないことを選んだ結果である.どちらの解決法が社会的により無難であるかは明らかだろう.

he or she がぎこちないという問題については,確かにぎこちないかもしれないが,対応する数の範疇についても同じくらいぎこちない表現として one or more や person or persons などがあり,これらは普通に使用されている.したがって,he or she だけを取りあげて「ぎこちない」と評するのは妥当ではない.

英語話者は,民衆の知恵として,より無難な解決法 (= singular they) を選択してきた.一方,規範文法家は,あまりに人工的,意図的,不自然なやり方 (he) に訴えてきたのである.

・ Bodine, Ann. "Androcentrism in Prescriptive Grammar: Singular 'they', Sex-Indefinite 'he,' and 'he or she'." Language in Society 4 (1975): 129--46.

2014-07-30 Wed

■ #1920. singular they を取り締まる規範文法 (1) [singular_they][prescriptive_grammar][gender][number][personal_pronoun][paradigm]

伝統的に規範文法によって忌避されてきた singular they が,近年,市民権を得てきたことについて,「#275. 現代英語の三人称単数共性代名詞」 ([2010-01-27-1]),「#1054. singular they」 ([2012-03-16-1]),またその他 singular_they の記事で触れてきた.英語史的には,singular they の使用は近代以前から確認されており,18世紀の規範文法家によって非難されたものの,その影響の及ばない非標準的な変種や口語においては,現在に至るまで連綿と使用され続けてきた.要するに,非規範的な変種に関する限り,singular they を巡る状況は,この500年以上の間,何も変わっていないのである.この変化のない平穏な歴史の最後の200年ほどに,singular they を取り締まる規範文法が現われたが,ここ数十年の間にその介入の勢いがようやく弱まってきた,という歴史である.Bodine (131) 曰く,

. . . despite almost two centuries of vigorous attempts to analyze and regulate it out of existence, singular 'they' is alive and well. Its survival is all the more remarkable considering that the weight of virtually the entire educational and publishing establishment has been behind the attempt to eradicate it.

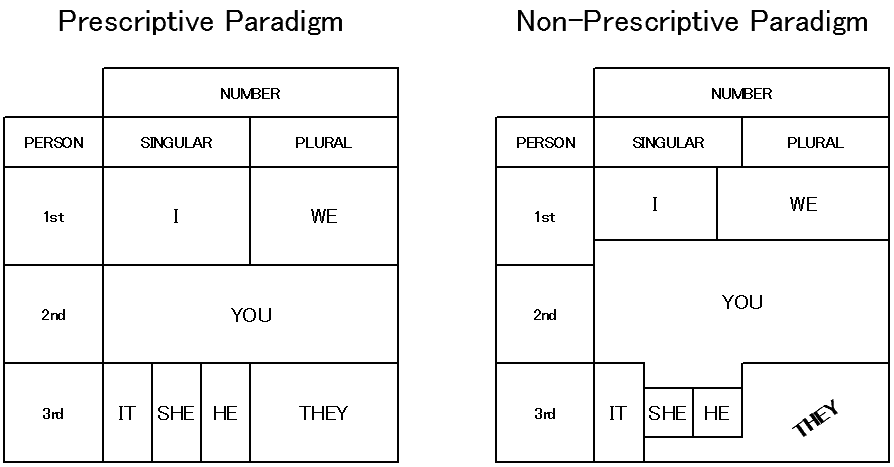

18世紀以降に話を絞ると,性を問わない単数の一般人称を既存のどの人称代名詞で表わすかという問題を巡って,(1) 新興の規範文法パラダイム (Prescriptive Paradigm) と,(2) 従来の非規範文法パラダイム (Non-Prescriptive Paradigm) とが対立してきた.Bodine (132) が,それぞれの人称代名詞のパラダイムを示しているので,再現しよう.

Non-Prescriptive Paradigm における YOU や WE の拡張は別の話題なのでおいておくとし,THEY が SHE, HE の領域に食い込んでいる部分が singular they の用法に相当する.比較すると,Prescriptive Paradigm の人工的な整然さがよくわかるだろう.後者のもつ問題点について,明日の記事で話題にする.

・ Bodine, Ann. "Androcentrism in Prescriptive Grammar: Singular 'they', Sex-Indefinite 'he,' and 'he or she'." Language in Society 4 (1975): 129--46.

2014-06-05 Thu

■ #1865. 神に対して thou を用いるのはなぜか [number][personal_pronoun][honorific][face][politeness][t/v_distinction][solidarity][sobokunagimon]

2人称代名詞 you と thou を巡る英語史上の問題については,多くの記事で取り上げてきた( you thou personal_pronoun を参照).中英語期から初期近代英語期まで見られた敬称の you と親称の thou の使い分けは,「#673. Burnley's you and thou」 ([2011-03-01-1]) で述べたように,細かく規定しようとすると非常に複雑だが,基本ルールとしては,社会的立場が上の者に対しては敬称の you を用いるべし,といえる.ところが,キリスト教徒が神に対して呼びかける場合には,英語では親称の thou を用いるのが慣習である.神のことを社会的立場が上の者と表現するのも妙ではあるが,究極の敬意を示す対象として,敬称の you が予想されそうなところだが,なぜそうならないのだろうか.実は,英語だけの問題ではない.現代のフランス語とドイツ語などを参照すると,やはり神に対して親称の tu, du をそれぞれ用いる慣習がある.

歴史的には,politeness に基づく T/V distinction がいまだ存在しなかった時代,例えば古英語期には,キリスト教のただ一人の神への呼びかけは,当然ながら単数形 thou を用いていたという事実がある.その伝統的な用法を,中英語以降も継続したということはありそうだ.また,唯一神であることを強調するために,単数を明示できる thou が選ばれたという考え方もある.しかし,前代からの伝統とはいえ,T/V distinction が導入され定着した時代の共時的な感覚として,神に対して thou と呼びかけるのは失礼とはまったく思わなかったのだろうか.そんな素朴な疑問がわいてくる.

これに対する1つの解答は,「#1564. face」 ([2013-08-08-1]) で導入した positive face あるいは solidarity-face を立てようとする politeness の考え方である.その記事で「英語に T/V distinction があった時代の親しみの thou と敬いの you は,向きこそ異なれ,いずれも相手の face を尊重する politeness の行為だということになる」と述べたように,親称の thou の使用は,敬称の you の使用とは異なった向きではあるが,同じようにポライトだということである.前者は相手(神)の positive face を立てる行為であり,互いの solidarity を醸成するのに役立つ.神が自分のことを thou と呼び,親しく歩み寄ってくれているのだから,その神の厚意を尊重して受け入れ,こちらからも親しみを込めて thou と呼んで接しよう,という説明になろうか.positive politeness と negative politeness については,Wardhaugh (292) が次のように説明している.

Positive politeness leads to moves to achieve solidarity through offers of friendship, the use of compliments, and informal language use: we treat others as friends and allies, do not impose on them, and never threaten their face. On the other hand, negative politeness leads to deference, apologizing, indirectness, and formality in language use: we adopt a variety of strategies so as to avoid any threats to the face others are presenting to us.

浅田 (19) は,ドイツ語で神を敬称の Sie ではなく親称の du で呼ぶ慣習について,positive politeness という術語を導入せずに,次のように易しく説明している.

たとえば,こんなふうに考えてはどうでしょう.キリスト教を信じている人は,食事の前や寝る前など,日常生活のいろいろな場面で神様にお祈りをします.何かうまくいかないときや,なやんでいるとき,どうしてもかなえたい希望があるときも,神様にお祈りをします.つまり神様は,人々の日常生活の中にいつでもいて,すぐ身近に感じている存在なのではないでしょうか.いつもそばにいて身近だから,「ドゥー」をつかうのだともいえます.

ということは,ドイツ語では「ドゥー」をつかったからといって,敬意を表わしていないことにはならないのです.親しみの表現と尊敬の表現とはぜんぜん関係がなくて,日本語のように,尊敬の表現をつかうと親しみがなくなってしまうなどということはないのです.親しみのある表現をつかって,なおかつ敬意を表わすことができるのが,ドイツ語なのだといえるのではないでしょうか.

・ Wardhaugh, Ronald. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 6th ed. Malden: Blackwell, 2010.

・ 浅田 秀子 『日本語にはどうして敬語が多いの?』 アリス館,1997年.

2014-02-26 Wed

■ #1766. a three-hour(s)-and-a-half flight [compound][adjective][plural][number][numeral][hyphen]

標記のような数詞と単位を含む複合形容詞においては,単位を表わす名詞は複数形を取らないのが規則とされる.a four-power agreement, a five-foot-deep river, a ten-dollar bill, a twelve-year-old boy などの如くである.

しかし,ときに複数形を取る例も散見され,a three-hours-and-a-half flight もあり得るし,a four years course もあり得る.Quirk et al. (Section 17.108) によれば,同種の表現として以下の4通りが可能である.

. . . in quantitative expressions of the following type there is possible variation . . .:

a ten day absence [singular] a ten-day absence [hyphen + singular] a ten days absence [plural] a ten days' absence [genitive plural]

同様に,「4年制課程」についても,"a four year course", "a four-year course", "a four years course", "a four years' course" のいずれもあり得ることになる.これらの変異形がいかにして生じてきたのか,使い分けの基準がありうるのかという問題は,通時的,理論的に興味深い問題だが,現段階では未調査である.

この問題と関連しうる話題として注意しておきたいのは,やはりイギリス英語において,名詞の限定形容詞用法では,その名詞が複数形としてある程度語彙化している場合に,複数形の形態のままで実現されることが多いという事実だ.例えば,Quirk et al. (Section 17.109) によると,イギリス英語限定だが,次のような例がみられるという.parks department, courses committee, examinations board, the heavy chemicals industry, Scotland Yard's Obscene Publications Squad, Chesterfield Hospitals management Committee, the British Museum Prints and Drawings Gallery, an Arts degree, soft drinks manufacturer, entertainments guide, appliances manufacturer, the Watergate tapes affair.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2013-12-09 Mon

■ #1687. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (4) [verb][conjugation][emode][number][agreement][analogy][3pp]

「#1413. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s」 ([2013-03-10-1]),「#1423. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (2)」 ([2013-03-20-1]),「#1576. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (3)」 ([2013-08-20-1]) に引き続いての話題.Wyld (340) は,初期近代英語期における3複現の -s を北部方言からの影響としてではなく,3単現の -s からの類推と主張している.

Present Plurals in -s.

This form of the Pres. Indic. Pl., which survives to the present time as a vulgarism, is by no means very rare in the second half of the sixteenth century among writers of all classes, and was evidently in good colloquial usage well into the eighteenth century. I do not think that many students of English would be inclined to put down the present-day vulgarism to North country or Scotch influence, since it occurs very commonly among uneducated speakers in London and the South, whose speech, whatever may be its merits or defects, is at least untouched by Northern dialect. The explanation of this peculiarity is surely analogy with the Singular. The tendency is to reduce Sing. and Pl. to a common form, so that certain sections of the people inflect all Persons of both Sing. and Pl. with -s after the pattern of the 3rd Pres. Sing., while others drop the suffix even in the 3rd Sing., after the model of the uninflected 1st Pers. Sing. and the Pl. of all Persons.

But if this simple explanation of the present-day Pl. in -s be accepted, why should we reject it to explain the same form at an earlier date?

It would seem that the present-day vulgarism is the lineal traditional descendant of what was formerly an accepted form. The -s Plurals do not appear until the -s forms of the 3rd Sing. are already in use. They become more frequent in proportion as these become more and more firmly established in colloquial usage, though, in the written records which we possess they are never anything like so widespread as the Singular -s forms. Those who persist in regarding the sixteenth-century Plurals in -s as evidence of Northern influence on the English of the South must explain how and by what means that influence was exerted. The view would have had more to recommend it, had the forms first appeared after James VI of Scotland became King of England. In that case they might have been set down as a fashionable Court trick. But these Plurals are far older than the advent of James to the throne of this country.

類推説を支持する主たる論拠は,(1) 3複現の -s は,3単現の -s が用いられるようになるまでは現れていないこと,(2) 北部方言がどのように南部方言に影響を与え得るのかが説明できないこと,の2点である.消極的な論拠であり,決定的な論拠とはなりえないものの,議論は妥当のように思われる.

ただし,1つ気になることがある.Wyld が見つけた初例は,1515年の文献で,"the noble folk of the land shotes at hym." として文証されるという.このテキストには3単現の -s は現われず,3複現には -ith がよく現れるというというから,Wyld 自身の挙げている (1) の論拠とは符合しないように思われるが,どうなのだろうか.いずれにせよ,先立つ中英語期の3単現と3複現の屈折語尾を比較検討することが必要だろう.

・ Wyld, Henry Cecil. A History of Modern Colloquial English. 2nd ed. London: Fisher Unwin, 1921.

2013-08-20 Tue

■ #1576. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (3) [verb][conjugation][emode][number][agreement][analogy][3pp]

[2013-03-10-1], [2013-03-20-1]に引き続き,標記の話題.北部方言影響説か3単現からの類推説かで見解が分かれている.初期近代英語を扱った章で,Fennell (143) は後者の説を支持して,次のように述べている.

In the written language the third person plural had no separate ending because of the loss of the -en and -e endings in Middle English. The third person singular ending -s was therefore frequently used also as an ending in the third person plural: troubled minds that wakes; whose own dealings teaches them suspect the deeds of others. The spread of the -s ending in the plural is unlikely to be due to the influence of the northern dialect in the South, but was rather due to analogy with the singular, since a certain number of southern plurals had ended in -e)th like the singular in colloquial use. Plural forms ending in -(e)th occur as late as the eighteenth century.

一方,Strang (146) は北部方言影響説を支持している.

The function of the ending, whatever form it took, also wavered in the early part of II [1770--1570]. By northern custom the inflection marked in the present all forms of the verb except first person, and under northern influence Standard used the inflection for about a century up to c. 1640 with occasional plural as well as singular value.

構造主義の英語史家 Strang の議論が興味深いのは,2点の指摘においてである.1点目は,初期近代英語の同時期に,古い be に代わって新しい are が用いられるようになったのは北部方言の影響ゆえであるという事実と関連させながら,3単・複現の -s について議論していることだ.are が疑いなく北部方言からの借用というのであれば,3複現の -s も北部方言からの借用であると考えるのが自然ではないか,という議論だ.2点目は,主語の名詞句と動詞の数の一致に関する共時的かつ通時的な視点から,3複現の -s が生じた理由ではなく,それがきわめて稀である理由を示唆している点である.上の引用文に続く箇所で,次のように述べている.

The tendency did not establish itself, and we might guess that its collapse is related to the climax, at the same time, of the regularisation of noun plurality in -s. Though the two developments seem to belong to very different parts of the grammar, they are interrelated in syntax. Before the middle of II there was established the present fairly remarkable type of patterning, in which, for the vast majority of S-V concords, number is signalled once and once only, by -s (/s/, /z/, /ɪz/), final in the noun for plural, and in the verb for singular. This is the culmination of a long movement of generalisation, in which signs of number contrast have first been relatively regularised for components of the NP, then for the NP as a whole, and finally for S-V as a unit.

名詞の複数の -s と動詞の3単現の -s の交差的な配列を,数を巡る歴史的発達の到達点ととらえる洞察は鋭い.3複現の出現が北部方言の影響か3単現からの類推かのいずれかに帰せられるにせよ,生起は稀である.なぜ稀であるかという別の問題にすり替わってはいるが,当初の純粋に形態的な問題が統語的な話題,通時的な次元へと広がってゆくのを感じる.

・ Fennell, Barbara A. A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001.

・ Strang, Barbara M. H. A History of English. London: Methuen, 1970.

2013-06-17 Mon

■ #1512. fish の複数形 [plural][number][poema_morale][manuscript][inflection]

現代英語では,通常 fish の複数形は同形の fish である (ex. I saw a school of fish in the river) .特に種類が異なる魚であることを強調する場合には fishes とすることもあるが,その場合にも three kinds of fish などとすることが多い.また,イギリス英語では種類の異同にかかわらず fishes とすることはあるが,一般的には fish は単複同形と考えておいてよいだろう.あるいは,複数としての fish は集合的に用いられているものと考えてもよい.その点では,部分的に fruit や hair などとも用法が似ている.

単複同形といえば,ほかに sheep や deer (ただし規則的な複数形 deers もある)が思い浮かぶかもしれない.これらは両語とも古英語の中性強変化名詞 scēap, dēor に遡り,複数主格・対格が同形になることは古英語の形態規則に沿っている.したがって,現代英語の単複同形は古英語からの遺産として説明される.

ところが,fish の古英語形 fisc は,男性強変化名詞なので複数主格・対格形は fiscas である.これが後に fishes へと発展してゆくのだが,現代英語でより一般的な複数形 fish のほうは sheep, deer のように古英語の遺産としては説明できないことになる.つまり,複数形 fish は古英語より後の時代に生まれた革新形と考える必要がある.

実際に,複数形 fish は初期中英語で初出している.OED によると,fish を単数形と同形のまま集合的に用いる用法 (1b) は,a1300 の Cursor Mundi に初出する.

9395 (Cott.): Foghul and fiche, grett thing and small.

また,MED の fish (n.) (2b) によれば,fish の総称的あるいは質量的な名詞としての用法が挙げられており,初例は?a1200の作とされる Layamon's Brut からだ.

Lay. Brut (Clg A.9) 22000: Þer inne is feower kunnes fisc.

手元にある初期中英語の複数形データベースでは,40例までが複数語尾を伴う形態で,5例のみが単数形と同形である.いまだ -es 形が優勢だが,後の歴史のある段階で形勢が逆転することになったのだろう.7つのバージョンで伝わる Poema Morale では,D写本とM写本のみが語尾なしの形態を用いている.

T(83): He makeð þe fisses in þe sa þe fueles on þe lofte.

J(82): He makede fysses in þe sea. and fuweles in þe lufte.

E1(83): He makede fisses inne þe see. and fuȝeles inne þe lofte

E2(83): He makede fisces in ðe sé. {end} fuȝeles in ðe lufte.

D (159--60): he wrohte fis on þer sae / and foȝeles on þar lefte.

L (83): He makede fisses in þe se 7 fuȝeles in þe lifte.

M (77): He scuppeþ þe fish in þe seo, þe foȝel bi þe lefte.

以上は「#12. How many carp!」 ([2009-05-11-1]) でも取り上げた話題だが,現代英語における「不規則な」形態の多くが古英語からの遺産として説明できる一方,中英語以降の革新として説明される例も同じくらい多いということに注意したい.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow