2015-09-12 Sat

■ #2329. 中英語の借用元言語 [borrowing][loan_word][me][lexicology][contact][latin][french][greek][italian][spanish][portuguese][welsh][cornish][dutch][german][bilingualism]

中英語の語彙借用といえば,まずフランス語が思い浮かび (「#1210. 中英語のフランス借用語の一覧」 ([2012-08-19-1])),次にラテン語が挙がる (「#120. 意外と多かった中英語期のラテン借用語」 ([2009-08-25-1]), 「#1211. 中英語のラテン借用語の一覧」 ([2012-08-20-1])) .その次に低地ゲルマン語,古ノルド語などの言語名が挙げられるが,フランス語,ラテン語の陰でそれほど著しくは感じられない.

しかし,実際のところ,中英語は上記以外の多くの言語とも接触していた.確かにその他の言語からの借用語の数は多くはなかったし,ほとんどが直接ではなく,主としてフランス語を経由して間接的に入ってきた借用語である.しかし,多言語使用 (multilingualism) という用語を広い意味で取れば,中英語イングランド社会は確かに多言語使用社会だったといえるのである.中英語における借用元言語を一覧すると,次のようになる (Crespo (28) の表を再掲) .

| LANGUAGES | Direct Introduction | Indirect Introduction |

| Latin | --- | |

| French | --- | |

| Scandinavian | --- | |

| Low German | --- | |

| High German | --- | |

| Italian | through French | |

| Spanish | through French | |

| Irish | --- | |

| Scottish Gaelic | --- | |

| Welsh | --- | |

| Cornish | --- | |

| Other Celtic languages in Europe | through French | |

| Portuguese | through French | |

| Arabic | through French and Spanish | |

| Persian | through French, Greek and Latin | |

| Turkish | through French | |

| Hebrew | through French and Latin | |

| Greek | through French by way of Latin |

「#392. antidisestablishmentarianism にみる英語のロマンス語化」 ([2010-05-24-1]) で引用した通り,"French acted as the Trojan horse of Latinity in English" という謂いは事実だが,フランス語は中英語期には,ラテン語のみならず,もっとずっと多くの言語からの借用の「窓口」として機能してきたのである.

関連して,「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1]),「#516. 直接のギリシア語借用は15世紀から」 ([2010-09-25-1]),「#2164. 英語史であまり目立たないドイツ語からの借用」 ([2015-03-31-1]) も参照.

・ Crespo, Begoña. "Historical Background of Multilingualism and Its Impact." Multilingualism in Later Medieval Britain. Ed. D. A. Trotter. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000. 23--35.

2015-09-11 Fri

■ #2328. 中英語の多言語使用 [me][bilingualism][french][latin][contact][sociolinguistics][writing][diglossia][register]

中英語における,英語,フランス語,ラテン語の3言語使用を巡る社会的・言語的状況については,これまでの記事でも多く取り上げてきた.例えば,以下を参照.

・ 「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1])

・ 「#661. 12世紀後期イングランド人の話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-02-17-1])

・ 「#1488. -glossia のダイナミズム」 ([2013-05-24-1])

・ 「#1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造」 ([2014-09-08-1])

・ 「#2025. イングランドは常に多言語国だった」 ([2014-11-12-1])

Crespo (24) は,中英語期における各言語の社会的な位置づけ,具体的には使用域,使用媒体,地位を,すごぶる図式ではあるが,以下のようにまとめている.

| LANGUAGE | Register | Medium | Status |

| Latin | Formal-Official | Written | High |

| French | Formal-Official | Written/Spoken | High |

| English | Informal-Colloquial | Spoken | Low |

Crespo (25) はまた,3言語使用 (trilingualism) が時間とともに2言語使用 (bilingualism) へ,そして最終的に1言語使用 (monolingualism) へと解消されていく段階を,次のように図式的に示している.

| ENGLAND | Languages | Linguistic situation |

| Early Middle Ages | Latin--French--English | TRILINGUAL |

| 14th--15th centuries | French--English | BILINGUAL |

| 15th--16th c. onwards | English | MONOLINGUAL |

実際には,3言語使用や2言語使用を実践していた個人の数は全体から見れば限られていたことに注意すべきである.Crespo (25) も2つ目の表について述べている通り,"The initial trilingual situation (amongst at least certain groups) developed into oral bilingualism (though not universal) which in turn gradually resulted in vernacular monolingualism" ということである.だが,いずれの表も,中英語期のマクロ社会言語学的状況の一面をうまく表現している図ではある.

・ Crespo, Begoña. "Historical Background of Multilingualism and Its Impact." Multilingualism in Later Medieval Britain. Ed. D. A. Trotter. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000. 23--35.

2015-08-11 Tue

■ #2297. 英語 flow とラテン語 fluere [latin][etymology][indo-european][cognate][comparative_linguistics][grimms_law]

昨日の記事「#2296. flute の語源について」 ([2015-08-10-1]) でラテン語の動詞 fluere (to flow) の印欧語根 *bhleu- (to swell, well up, overflow) に触れた.この動詞の語根をもとにラテン語で様々な語彙が派生し,その多くが後に英語へ借用された.例を挙げれば,affluent, confluent, effluent, effluvium, efflux, fluctuate, fluent, fluid, flume, fluor, fluorescent, fluoride, fluoro-, flush, fluvial, flux, influence, influenza, influx, mellifluous, reflux, superfluous 等だ.

同じ印欧語根 *bhleu- に由来する英語の本来語は存在しないが,ゲルマン系としては古ノルド語経由で bloat (to swell) が英語に入っている.この語の語頭子音 b- から分かるとおり,印欧語根の *bh はゲルマン語ではグリムの法則 (grimms_law) により b として現われる.一方,同じ *bh は,ラテン語では上に挙げた多くの例が示すように f へ変化している.結果としてみれば英語 b とラテン語 f が音韻的に対応することになり,このことは,別の語根からの例になるが bear vs fertile, bloom vs flower, break vs fragile, brother vs fraternal など数多く挙げることができる.

さて,次に英語 flow について考えよう.上記のラテン語 fluere と意味も形態も似ているので,つい同根と勘違いしてしまうが,語源的には無縁である.英語の f は,グリムの法則を逆算すれば,印欧祖語で *p として現われるはずであり,後者はラテン語へそのまま p として受け継がれる.つまり,共時的には英語 f とラテン語 p が対応することになる (e.g. father vs paternal, foot vs pedal, fish vs Pisces) .実際,flow の印欧語根として再建されているのは *pleu- (to flow) である.

*pleu- を起源とする英語本来語としては,fledge, flee, fleet, fley, flight, float, flood, flow, flutter, fly, fowl などが挙げられる.古ノルド語経由で英語に入ってきたものとしては,flit, flotilla がある.その他,(flèche, fletcher), flotsam, (flue [flew]), fugleman などもゲルマン語を経由してきた単語である.

ラテン語では,印欧語根 *pleu- をもとに,例えば pluere (to rain) が生じたが,これに関連するいくつかの語が英語へ入った (e.g.pluvial, pulmonary) .ギリシア語でも印欧語根の子音を保ったが,Pluto, plut(o)-, plutocracy, pneumonia, pyel(o)- 等が英語に入っている.ケルト語から「滝」を表わす linn も同根である.

上記のように,英語 flow とラテン語 fluere は,それぞれ印欧語根 *pleu- (to flow) と *bhleu- (to swell, well up, overflow) に遡り,語源的には無縁である.しかし,共時的には両単語は意味も形態も似ており,互いに関係しているはずと思うのも無理からぬことである.例えば,ともに「流入」を意味する inflow と influx が語源的に無関係といわれれば驚くだろう(反対語はそれぞれ outflow と efflux である).古英語でも,ラテン語 fluere に対する訳語としてもっぱら本来語 flōwan (> PDE flow) を当てていたという事実があり,共時的に両者を結びつけようとする意識があったように思われる.

比較言語学に基づいて語源を追っていると,flow と fluere のように,互いに似た意味と形態をもっている語のペアが,実は語源的に無縁であるとわかって驚く機会が時折ある.典型的なのが,英語の have とラテン語 habēre (及びラテン語形に対応するフランス語 avoir)である.形態も似ているし「持っている」という主たる語義も共通であるから同根かと思いきや,語源的には無関係である.他にも『英語語源辞典』(pp. 1666--67) の「真の語源と見せかけの語源」を参照されたい

・ 寺澤 芳雄 (編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

2015-07-28 Tue

■ #2283. Shakespeare のラテン語借用語彙の残存率 [shakespeare][inkhorn_term][loan_word][lexicology][emode][renaissance][latin][greek]

初期近代英語期のラテン語やギリシア語からの語彙借用は,現代から振り返ってみると,ある種の実験だった.「#45. 英語語彙にまつわる数値」 ([2009-06-12-1]) で見た通り,16世紀に限っても13000語ほどが借用され,その半分以上の約7000語がラテン語からである.この時期の語彙借用については,以下の記事やインク壺語 (inkhorn_term) に関連するその他の記事でも再三取り上げてきた.

・ 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1])

・ 「#1409. 生き残ったインク壺語,消えたインク壺語」 ([2013-03-06-1])

・ 「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1])

・ 「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1])

16世紀後半を代表する劇作家といえば Shakespeare だが,Shakespeare の語彙借用は,上記の初期近代英語期の語彙借用の全体的な事情に照らしてどのように位置づけられるだろうか.Crystal (63) は,Shakespeare において初出する語彙について,次のように述べている.

LEXICAL FIRSTS

・ There are many words first recorded in Shakespeare which have survived into Modern English. Some examples:

accommodation, assassination, barefaced, countless, courtship, dislocate, dwindle, eventful, fancy-free, lack-lustre, laughable, premeditated, submerged

・ There are also many words first recorded in Shakespeare which have not survived. About a third of all his Latinate neologisms fall into this category. Some examples:

abruption, appertainments, cadent, exsufflicate, persistive, protractive, questrist, soilure, tortive, ungenitured, unplausive, vastidity

特に上の引用の第2項が注目に値する.Shakespeare の初出ラテン借用語彙に関して,その3分の1が現代英語へ受け継がれなかったという事実が指摘されている.[2010-08-18-1]の記事で触れたように,この時期のラテン借用語彙の半分ほどしか後世に伝わらなかったということが一方で言われているので,対応する Shakespeare のラテン語借用語彙が3分の2の確率で残存したということであれば,Shakespeare は時代の平均値よりも高く現代語彙に貢献していることになる.

しかし,この Shakespeare に関する残存率の相対的な高さは,いったい何を意味するのだろうか.それは,Shakespeare の語彙選択眼について何かを示唆するものなのか.あるいは,時代の平均値との差は,誤差の範囲内なのだろうか.ここには語彙の数え方という方法論上の問題も関わってくるだろうし,作家別,作品別の統計値などと比較する必要もあるだろう.このような統計値は興味深いが,それが何を意味するか慎重に評価しなければならない.

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2015-07-22 Wed

■ #2277. 「行く」の意味の repair [etymology][latin][loan_word][homonymy][doublet][indo-european][cognate]

repair (修理する)は基本語といってよいが,別語源の同形同音異義語 (homonym) としての repair (行く)はあまり知られていない.辞書でも別の語彙素として立てられている.

「修理する」の repair は,ラテン語 reparāre に由来し,古フランス語 réparer を経由して,中英語に repare(n) として入ってきた.ラテン語根 parāre は "to make ready" ほどを意味し,印欧祖語の語根 *perə- (to produce, procure) に遡る.この究極の語根からは,apparatus, comprador, disparate, emperor, imperative, imperial, parachute, parade, parasol, pare, parent, -parous, parry, parturient, prepare, rampart, repertory, separate, sever, several, viper などの語が派生している.

一方,「行く」の repair は起源が異なり,後期ラテン語 repatriāre が古フランス語で repairier と形態を崩して,中英語期に repaire(n) として入ってきたものである.したがって,英語 repatriate (本国へ送還する)とは2重語を構成する.語源的な語根は,patria (故国)や pater (父)であるから,「修理する」とは明らかに区別される語彙素であることがわかる.印欧祖語 *pəter- (father) からは,ラテン語経由で expatriate, impetrate, padre, paternal, patri-, patrician, patrimony, patron, perpetrate が,またギリシア語経由で eupatrid, patriarch, patriot, sympatric が英語に入っている.

現代英語の「行く」の repair は,古風で形式的な響きをもち,「大勢で行く,足繁く行く」ほどを意味する.いくつか例文を挙げよう.最後の例のように「(助けなどを求めて)頼る,訴える,泣きつく」の語義もある.

・ After dinner, the guests repaired to the drawing room for coffee.

・ (humorous) Shall we repair to the coffee shop?

・ He repaired in haste to Washington.

・ May all to Athens backe againe repaire. (Shakespeare, Midsummer Night's Dream iv. i. 66)

・ Thither the world for justice shall repaire. (Sir P. Sidney tr. Psalmes David ix. v)

中英語からの豊富な例は,MED の repairen (v) を参照されたい.

2015-07-16 Thu

■ #2271. 後期中英語の macaronic な会計文書 [code-switching][me][bilingualism][latin][register][pragmatics]

中英語期の英羅仏の混在型文書,いわゆる macaronic writing については,「#1470. macaronic lyric」 ([2013-05-06-1]),「#1625. 中英語期の書き言葉における code-switching」 ([2013-10-08-1]) で話題にし,それを応用した議論として初期近代英語期の語源的綴字について「#1941. macaronic code-switching としての語源的綴字?」 ([2014-08-20-1]) の記事を書いた.文書のなかで言語を切り替える動機づけは,ランダムなのか,あるいは社会的・談話語用的な意味合いがあるのか議論してきた.

この分野で活発に研究している Wright (768--69) は,中英語の文書,とりわけ彼女の調査したロンドンの会計文書に現われる英羅語の code-switching には,社会的・談話語用的な動機づけがあったのではないかと論じている

I am led to suggest that macaronic writing should not be taken simply as a reflection of growing ignorance of Latin, nor be explained merely as some kind of partial bilingualism into which users naturally fell because they had been exposed to Latin in their profession. Rather I conclude that macaronic writing formed a deliberate, formal register; with systemic rules for the formation of words and sentences, which underwent temporal change as does any language structure. At this early stage of investigation, I venture to suggest that macaronic writing may be associable with a specific social group (in this case, accountants) whose professional status was defined at least in part by a facility in both languages, and whose emerging position may itself have been marked by the hybrid usage of macaronic writing as a formal register in professional contexts.

会計文書における英羅語の混在がランダムな code-switching ではないということ,両言語をまともに解さない半言語使用 (semilingualism) に基づくものではないということについて,Wright (769fn) はピジン語と対比しながら次のように述べている.

. . . pidgins develop due to the inability of the interlocutors to understand each other's language, whereas macaronic writing appears to show the ability of the composer to understand both Latin and English. Pidgins depend upon the spoken form as a primary medium for their development, whereas there is no evidence that material so stylistically sophisticated as macaronic sermons or administrative records were first transmitted as speech.

macaronic writing は商用文書のほかに聖歌や説教にも見られるが,いずれの使用域においても何らかの社会的・語用的な動機づけがあるのではないかという議論である.商用文書に関しては,実用を目的とする上で英羅語混在が有利な何らかの理由があったのかもしれないし,聖歌や説教では使用言語によって,聞き手の宗教心に訴えかける効果が異なっていたということなのかもしれない.いずれにせよ,code-switching に動機づけがあったとして,それが具体的に何だったのかが問題である.

・ Wright, Laura. "Macaronic Writing in a London Archive, 1380--1480." History of Englishes: New Methods and Interpretations in Historical Linguistics. Ed. Matti Rissanen, Ossi Ihalainen, Terttu Nevalainen, and Irma Taavitsainen. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1992. 762--71.

2015-06-15 Mon

■ #2240. thousand は "swelling hundred" [etymology][indo-european][numeral][latin][loan_word]

先日,thousand の語源が「膨れあがった百」であることを初めて知った.現代英語の thousand からも古英語の þūsend からも,hund(red) が隠れているとは想像すらしなかったが,調べてみると PGmc *þūs(h)undi- に遡るといい,なるほど hund が隠れている.印欧祖語形としては *tūskm̥ti が再建されており,その第1要素は *teu(ə)- (to swell, be strong) である.これはラテン語動詞 tumēre (to swell) を生み,そこから様々に派生した上で英語へも借用され,tumour, tumult などが入っている.ギリシア語に由来する tomb 「墓,塚」もある.また,ゲルマン語から英語へ受け継がれた語としては thigh, thumb などがある.腿も親指も,膨れあがって太いと言われればそのとおりだ.かくして,thousand は「膨れあがった百」ほどの意となった.

一方,ラテン語の mille (thousand) は,まったく起源が異なり,thousand との接点はないようだ.では mille の起源は何かというと,これが不詳である.印欧祖語には「千」を表わす語は再建されておらず,確実な同根語もみられない.英語には早い段階で mile が借用され,millenium, millepede, milligram, million などの語では combining form (cf. 「#552. combining form」 ([2010-10-31-1])) として用いられるなど活躍しているのだが,謎の多い語幹である.

hundred を表わす印欧語根については,「#100. hundred と印欧語比較言語学」 ([2009-08-05-1]),「#1150. centum と satem」 ([2012-06-20-1]) を参照.

2015-05-11 Mon

■ #2205. proceed vs recede [spelling][latin][french][spelling_pronunciation_gap][orthography]

標題の語は,語源的には共通の語幹をもち,接頭辞が異なるだけなのだが,現代英語ではそれぞれ <proceed>, <recede> と異なる綴字を用いる.これは一体なぜなのかと,学生からの鋭い質問が寄せられた.

なるほど語幹はラテン語 -cedere (go, proceed) あるいはそのフランス語形 -céder に由来するので,語源的には <cede> の綴字がふさわしいところだろうが,語によって <ceed> か <cede> かが決まっている.Upward and Davidson (103) は,次の10語を挙げている.

・ -<ceed>: exceed, proceed, succeed

・ -<cede>: cede, accede, concede, intercede, precede, recede, secede

いずれの語も,中英語期や初期近代英語に最初に現われたときの綴字は -<cede> だったのだが,混乱期を経て,上の状況に収まったという.初期近代英語では interceed, preceed, recead/receed なども行われていたが,標準的にはならなかった.振り返ってみると -<cede> が優勢だったように見えるが,類推と逆類推の繰り返しにより,各々がほとんどランダムに決まったといってよいのではないか.綴字と発音の一対多の関係をよく表わす例だろう.

このような混乱に乗じて,同一単語が2語に分かれた例がある.discrete と discreet だ.いずれもラテン語 discretus に遡るが,綴字の混乱を逆手に取るかのようにして,2つの異なる語へ分裂した.しかし,だからといって何かが分かりやすくなったわけでもないが・・・.

近代英語では <e>, <ee>, <ea> の三つ巴の混乱も珍しくなく,complete, compleat, compleet などと目まぐるしく代わった.この混乱の落とし子ともいうべきものが,speak vs speech のような対立に残存している (Upward and Davidson 104; cf. 「#49. /k/ の口蓋化で生じたペア」 ([2009-06-16-1])) .関連して,「#436. <ea> の綴りの起源」 ([2010-07-07-1]) も要参照.

-<cede> vs -<ceed> の例に限らず,長母音 /iː/ に対応する綴字の選択肢の多さは目を見張る.いくつか挙げてみよう.

・ <ae>: Caeser, mediaeval

・ <ay>: quay

・ <e>: be, he, mete

・ <ea>: lead, meat, sea

・ <ee>: feet, meet, see

・ <ei>: either, receive, seize,

・ <eigh>: Leigh

・ <eip>: receipt

・ <eo>: feoff, people

・ <ey>: key

・ <i>: chic, machine, Philippines

・ <ie>: believe, chief, piece

・ <oe>: amoeba, Oedipus

探せば,ほかにもあると思われる.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2015-03-29 Sun

■ #2162. OED によるフランス語・ラテン語からの借用語の推移 [oed][loan_word][statistics][french][latin][lexicology]

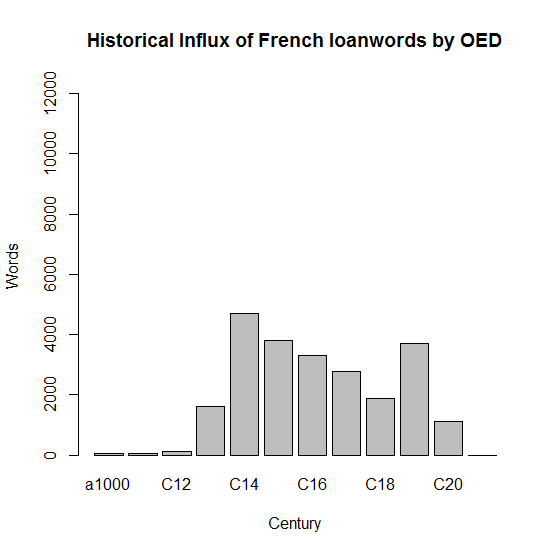

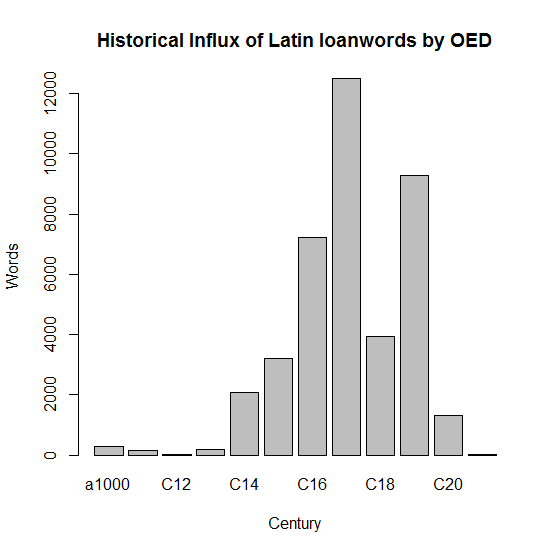

Wordorigins.org の "Where Do English Words Come From?" と題する記事では,OED をソースとした語種比率の通時的推移の調査報告がある.古英語から現代英語への各世紀に,語源別にどれだけの新語が語彙に加えられたかが解説とともにグラフで示されている.本文中にも述べられているように,見出し語の語源に関して OED の語源欄より引き出された情報は,眉に唾をつけて解釈しなければならない.というのは,語源欄にある言語が言及されていたとしても,それが借用元の語源を表すとは限らないからだ.しかし,およその参考になることは確かであり,通時的な概観のために有用であることには相違ない.

ここでは,CSV形式あるいはEXCEL形式で公開されている世紀別で語源別の数値を拝借し,フランス語とラテン語から英語語彙へ追加された借用語の推移をグラフ化して並べてみた.

|

|

得られた傾向は,一般的な概説書で述べられているものと一致する.フランス語のピークは後期中英語,ラテン語のピークは初期近代英語である.比較すると,ラテン語の規模の著しさがよくわかる.フランス語とラテン語からの借用語に関連する統計については,すでに以下のように多くの記事で取り上げてきたので,そちらも参照されたい.

[2009-08-22-1]: #117. フランス借用語の年代別分布

[2009-11-15-1]: #202. 現代英語の基本語彙600語の起源と割合

[2010-06-30-1]: #429. 現代英語の最頻語彙10000語の起源と割合

[2010-12-12-1]: #594. 近代英語以降のフランス借用語の特徴

[2011-02-16-1]: #660. 中英語のフランス借用語の形容詞比率

[2011-08-20-1]: #845. 現代英語の語彙の起源と割合

[2011-09-18-1]: #874. 現代英語の新語におけるソース言語の分布

[2012-08-11-1]: #1202. 現代英語の語彙の起源と割合 (2)

[2012-08-18-1]: #1209. 1250年を境とするフランス借用語の区分

[2012-08-20-1]: #1211. 中英語のラテン借用語の一覧

[2012-09-03-1]: #1225. フランス借用語の分布の特異性

[2012-09-04-1]: #1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布

[2012-11-12-1]: #1295. フランス語とラテン語の2重語

[2014-08-24-1]: #1945. 古英語期以前のラテン語借用の時代別分類

また,OED の利用に際しては,以下の記事も参照されたい.

[2010-10-10-1] #:531. OED の引用データをコーパスとして使えるか

[2010-10-14-1] #:535. OED の引用データをコーパスとして使えるか (2)

[2010-10-15-1] #:536. OED の引用データをコーパスとして使えるか (3)

[2011-01-05-1] #:618. OED の検索結果から語彙を初出世紀ごとに分類する CGI

[2011-01-29-1] #:642. OED の引用データをコーパスとして使えるか (4)

2015-01-31 Sat

■ #2105. 英語アルファベットの配列 [writing][grammatology][alphabet][phonetics][greek][latin][etruscan][grapheme]

昨日の記事「#2104. 五十音図」 ([2015-01-30-1]) の終わりにアルファベットの配列について触れたので,今回はその話題を.なぜ英語で用いられるアルファベットは「ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ」という並び順なのだろうか.

文字の配列の原理として,4種類が区別される(大名, p. 155).

(1) 音韻論的分類法.音韻論の原理に基づくもので,昨日示した五十音図のほか,サンスクリット語の文字(悉曇,梵字),ハングルなどがある.

(2) 形態論的分類法.形字の原理に従うもので,漢和辞典の部首索引など.

(3) 意義論的分類法.意味の関連を考慮したもの.漢和辞典の部首は意符でもあるので,部分的には意義論的分類法に従っている.また,中国最古の字書『説文解字』では,文字の並びそれ自身が意味をもっていたという点で,意義論的分類の一種と考えられる.千字文,「あめつちの詞」,「いろは」 (cf. 「#1005. 平仮名による最古の「いろは歌」が発見された」 ([2012-01-27-1]))なども,字の並びが全体として章句を構成している点で,この分類に属する.

(4) 年代順的分類法.各文字が派生したり加えられたりした順に並べる原理.例えば,<Z> はラテン・アルファベットにおいて後から加えられたので,文字セットの最後に配されている等々.<G>, <X>, <I--J>, <U--V--W-Y> も同じ.仮名の「ん」も.

英語アルファベットはラテン・アルファベットから派生したものであり,後者が6世紀末にブリテン等に伝えられて以来,新たな文字が付け加わるなど,いくつかの改変を経て現代に至る.したがって,英語アルファベットの配列は,原則としてラテン・アルファベットの配列にならっている考えてよい.では,ラテン・アルファベットの配列は何に基づいているのか.それは,ギリシア・アルファベットの配列である.ギリシア・アルファベットの配列が基となり,それにいくつかの改変が加えられ,ラテン・アルファベットが成立した.

ギリシア・アルファベットからラテン・アルファベットに至る経緯には,前者の西方型の変種 (cf. 「#1837. ローマ字とギリシア文字の字形の差異」 ([2014-05-08-1])) やエトルリア語 (Etruscan) が関与しており,事情は複雑である.この過程で <C> から <G> が派生したり (cf. 「#1824. <C> と <G> の分化」 ([2014-04-25-1])) ,その <G> がギリシア・アルファベットでは <Z> の占めていた位置に定着したり,<Z> が後から再導入されたりした.また,<F> は「#1825. ローマ字 <F> の起源と発展」 ([2014-04-26-1]) でみたような経緯で現在の位置に納まった.<I--J> の分化や <U--V--W--Y> の分化 (cf. 「#1830. Y の名称」 ([2014-05-01-1])) も生じて,それぞれおよそ隣り合う位置に配された.このように種々の改変はあったが,全体としてはギリシア・アルファベットの配列が基盤にあることは疑いえない.

では,そのギリシア・アルファベットの配列の原理は何か.「#1832. ギリシア・アルファベットの文字の名称 (1)」 ([2014-05-03-1]),「#1833. ギリシア・アルファベットの文字の名称 (2)」 ([2014-05-04-1]) でみたように,ギリシア・アルファベットは,セム・アルファベット (Semitic alphabets) の1変種であるフェニキア・アルファベット (Phoenician alphabet) に由来する.したがって,究極的にはフェニキア・アルファベットなどの原初アルファベットの配列原理を理解しなければならない.

「#1832. ギリシア・アルファベットの文字の名称 (1)」 ([2014-05-03-1]) に掲げた文字表の右端2列が,セム語における文字の名称と意味である.並び合っている1組の文字の意味が,「手」 (yod) と「曲げた手」 (kaf) ,「水」 (mēm) と「魚」 (nūn) のように何らかの関係をもっているところから考えると,少なくとも部分的には意義論的分類法に従っているのではないかと思われる節がある.一方,bet, gaml, delt は破裂音を表し,hé, wau (セム語ではこの位置にあった), zai は摩擦音を表し,lamd, mém, nun は流音を表すなど,音韻論的分類法の原理も部分的に働いているようにみえる.全体としても,およそ子音は調音位置が唇から咽喉へ,母音は低母音から高母音へと並んでいるかのようだ(大名,p. 157).

以上をまとめると,英語アルファベットの配列は,一部意義論的,一部音韻論的な原理で配列されたと思われるフェニキア・アルファベットに起源をもち,そこへギリシア・アルファベットとラテン・アルファベットの各段階において主として年代順的な原則により新しい文字が加えられるなど種々の改変がなされた結果である,といえる.関連して「#1849. アルファベットの系統図」 ([2014-05-20-1]) も参照されたい.

・ 大名 力 『英語の文字・綴り・発音のしくみ』 研究社,2014年.

2015-01-18 Sun

■ #2092. アルファベットは母音を直接表わすのが苦手 [grammatology][grapheme][vowel][alphabet][greek][latin][spelling][digraph][diacritical_mark]

「#1826. ローマ字は母音の長短を直接示すことができない」 ([2014-04-27-1]) で取り上げた話題をさらに推し進めると,標記のように「アルファベットは母音を直接表わすのが苦手」と言ってしまうこともできるかもしれない.この背景には3千年を超えるアルファベットの歴史がある.

「#423. アルファベットの歴史」 ([2010-06-24-1]) でみたように,古代ギリシア人は子音文字であるフェニキアのアルファベットを素材として今から3千年ほど前に初めて母音字を創案したとされるが,その創案は,ギリシア語の子音表記にとって余剰的なフェニキア文字のいくつかをギリシア語の母音に当ててみようという,どちらかというと消極的な動機づけに基づいていた.つまり,母音を表す母音字を発明しようという積極的な動機があったわけではない.実際,ギリシア語の様々な母音を正確に表わそうとするならば,フェニキア・アルファベットからのいくつかの余剰的な文字だけでは明らかに数が不足していた.だが,だからといって新たな母音字を作り出すというよりは,あくまで伝統的な文字セットを用いて子音と同時にいくつかの母音「も」表わせるように工夫したということだ.フェニキア文字以後のローマン・アルファベットの歴史的発展の記述を Horobin (48--49) より要約すると,次のようになる.

The Origins of the Roman alphabet lie in the script used by Phoenician traders around 1000 BC. This was a system of twenty-two letters which represented the individual consonant sounds, in a similar way to modern consonantal writing systems like Arabic and Hebrew. The Phoenician system was adopted and modified by the Greeks, who referred to them as 'Phoenician letters' and who added further symbols, while also re-purposing existing consonantal symbols not needed in Greek to represent vowel sounds. The result was a revolutionary new system in which both vowels and consonants were represented, although because the letters used to represent the vowel wounds in Greek were limited to the redundant Phoenician consonants, a mismatch between the number of vowels in speech and writing was created which still affects English today.

この消極的な母音字の創案とその伝統は,そのままエトルリア文字,それからローマ字へも伝わり,結果的には現代英語にもつらなっている.もちろん,英語史を含め,その後ローマ字を用いてきた多くの言語変種の歴史的段階において,母音をより正確に表わす方法は編み出されてきた.英語史に限っても,二重字 (digraph) など文字の組み合わせにより,ある母音を表すということはしばしば行われてきたし,magic <e> (cf. 「#1289. magic <e>」 ([2012-11-06-1])) にみられるような発音区別符(号) (diacritical mark; cf. 「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1])) 的な <e> の使用によって先行母音の音質や音量を表す試みもなされてきた.だが,現代英語においても,これらの方法は間接的な母音表記にとどまり,ずばり1文字で直接ある母音を表記するという作用は限定的である.数千年という長い時間の歴史的視座に立つのであれば,これはアルファベットが子音文字として始まったことの呪縛とも称されるものかもしれない.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2014-12-29 Mon

■ #2072. 英語語彙の三層構造の是非 [lexicology][loan_word][latin][french][register][synonym][romancisation][lexical_stratification]

英語語彙の三層構造について「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]),「#335. 日本語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-28-1]),「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1]),「#1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造」 ([2014-09-08-1]) など,多くの記事で言及してきた.「#1366. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2013-01-22-1]) でみたように,語彙の三層構造ゆえに英語は非民主的な言語であるとすら言われることがあるが,英語語彙のこの特徴は見方によっては是とも非となる類いのものである.

Jespersen (121--39) がその是と非の要点を列挙している.まず,長所から.

(1) 英仏羅語に由来する類義語が多いことにより,意味の "subtle shades" が表せるようになった.

(2) 文体的・修辞的な表現の選択が可能になった.

(3) 借用語には長い単語が多いので,それを使う話者は考慮のための時間を確保することができる.

(4) ラテン借用語により国際性が担保される.

まず (1) と (2) は関連しており,表現力の大きさという観点からは確かに是とすべき項目だろう.日本語語彙の三層構造と比較すれば,表現者にとってのメリットは実感されよう.しかし,聞き手や学習者にとっては厄介な特徴ともいえ,その是非はあくまで相対的なものであるということも忘れてはならない.(3) はおもしろい指摘である.非母語話者として英語を話す際には,ミリ秒単位(?)のごく僅かな時間稼ぎですら役に立つことがある.長い単語で時間稼ぎというのは,状況にもよるが,戦略としては確かにあるのではないか.(4) はラテン借用語だけではなくギリシア借用語についても言えるだろう.関連して「#512. 学名」 ([2010-09-21-1]) や「#1694. 科学語彙においてギリシア語要素が繁栄した理由」 ([2013-12-16-1]) も参照されたい.

次に,Jespersen が挙げている短所を列挙する.

(5) 不必要,不適切なラテン借用語の使用により,意味の焦点がぼやけることがある.

(6) 発音,綴字,派生語などについて記憶の負担が増える.例えば,「#859. gaseous の発音」 ([2011-09-03-1]) の各種のヴァリエーションの問題や「#573. 名詞と形容詞の対応関係が複雑である3つの事情」 ([2010-11-21-1]) でみた labyrinth の派生形容詞の問題などは厄介である.

(7) 科学の日常化により,関連語彙には国際性よりも本来語要素による分かりやすさが求められるようになってきている.例えば insomnia よりも sleeplessness のほうが分かりやすく有用であるといえる.

(8) 非本来語由来の要素の導入により,派生語間の強勢位置の問題が生じた (ex. Cánada vs Canádian) .

(9) ラテン語の複数形 (ex. phenomena, nuclei) が英語へもそのまま持ち越されるなどし,形態論的な統一性が崩れた.

(10) 語彙が非民主的になった.

是と非とはコインの表裏の関係にあり,絶対的な判断は下しにくいことがわかるだろう.結局のところ,英語の語彙構造それ自体が問題というよりは,それを使用者がいかに使うかという問題なのだろう.現代英語の語彙構造は,各時代の言語接触などが生み出してきた様々な語彙資源の歴史的堆積物にすぎず,それ自体に良いも悪いもない.したがって,そこに民主的あるいは非民主的というような評価を加えるということは,評価者が英語語彙を見る自らの立ち位置を表明しているということである.Jespersen (139) は次の総評をくだしている.

While the composite character of the language gives variety and to some extent precision to the style of the greatest masters, on the other hand it encourages an inflated turgidity of style. . . . [W]e shall probably be near the truth if we recognize in the latest influence from the classical languages 'something between a hindrance and a help'.

日本語において明治期に大量に生産された(チンプン)漢語や20世紀にもたらされた夥しいカタカナ語にも,似たような評価を加えることができそうだ(「#1999. Chuo Online の記事「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」」 ([2014-10-17-1]) とそこに張ったリンク先を参照).

英語という言語の民主性・非民主性という問題については「#134. 英語が民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2009-09-08-1]),「#1366. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2013-01-22-1]),「#1845. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由 (2)」 ([2014-05-16-1]) で取り上げたので,そちらも参照されたい.また,英語語彙のロマンス化 (romancisation) に関する評価については「#153. Cosmopolitan Vocabulary は Asset か?」 ([2009-09-27-1]) や「#395. 英語のロマンス語化についての評」 ([2010-05-27-1]) を参照.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Growth and Structure of the English Language. 10th ed. Chicago: U of Chicago, 1982.

2014-12-16 Tue

■ #2059. 語源的綴字,表語文字,黙読習慣 (2) [etymological_respelling][latin][grammatology][manuscript][silent_reading][standardisation][renaissance]

昨日の記事「#2058. 語源的綴字,表語文字,黙読習慣 (1)」 ([2014-12-15-1]) に引き続いての話題.

昨日引用した Perret がフランス語史において指摘したのと同趣旨で,Scragg (56) は,英語史における黙字習慣の発展と表語文字への転換とが密接に関わっていることを指摘している.

. . . an important change overtook the written language towards the end of the fourteenth century: suddenly literacy became more widespread with the advent of cheaper writing materials. In earlier centuries, while parchment was expensive and wax tablets were cumbersome, the church easily retained control of education and writing, but with the introduction of paper, mass literacy became both feasible and desirable. In the fifteenth century, private reading began to replace public recitation, and the resultant demand for books led, during that century, to the development of the printing press. As medieval man ceased pointing to the words with his bookmark as he pronounced them aloud, and turned to silent reading for personal edification and satisfaction, so his attention was concentrated more on the written word as a unit than on the speech sounds represented by its constituent letters. The connotations of the written as opposed to the spoken word grew, and given the emphasis on the classics early in the Renaissance, it was inevitable that writers should try to extend the associations of English words by giving them visual connection with related Latin ones. They may have been influences too by the fact that Classical Latin spelling was fixed, whereas that of English was still relatively unstable, and the Latinate spellings gave the vernacular an impression of durability. Though the etymologising movement lasted from the fifteenth century to the seventeenth, it was at its height in the first half of the sixteenth.

黙字習慣が確立してくると,読者は一連の文字のつながりを,その発音を介在させずに,直接に語という単位へ結びつけることを覚えた.もちろん綴字を構成する個々の文字は相変わらず表音主義を標榜するアルファベットであり,表音主義から表語主義へ180度転身したということにはならない.だが,表語主義の極へとこれまでより一歩近づいたことは確かだろう.

さらに重要と思われるのは,引用の後半で Scragg も指摘しているように,ラテン語綴字の採用が表語主義への流れに貢献し,さらに綴字の標準化の流れにも貢献したことだ.ルネサンス期のラテン語熱,綴字標準化の潮流,語源的綴字,表語文字化,黙読習慣といった諸要因は,すべて有機的に関わり合っているのである.

・ Scragg, D. G. A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974.

2014-12-15 Mon

■ #2058. 語源的綴字,表語文字,黙読習慣 (1) [french][etymological_respelling][latin][grammatology][manuscript][scribe][silent_reading][renaissance][hfl]

一昨日の記事「#2056. 中世フランス語と英語における語源的綴字の関係 (1)」 ([2014-12-13-1]) で,フランス語の語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) が同音異義語どうしを区別するのに役だったという点に触れた.フランス語において語源的綴字がそのような機能を得たということは,別の観点から言えば,フランス語の書記体系が表音 (phonographic) から表語 (logographic) へと一歩近づいたとも表現できる.このような表語文字体系への接近が,英語では中英語から近代英語にかけて生じていたのと同様に,フランス語では古仏語から中仏語にかけて生じていた.むしろフランス語での状況の方が,英語より一歩も二歩も先に進んでいただろう.(cf. 「#1332. 中英語と近代英語の綴字体系の本質的な差」 ([2012-12-19-1]),「#1386. 近代英語以降に確立してきた標準綴字体系の特徴」 ([2013-02-11-1]),「#1829. 書き言葉テクストの3つの機能」 ([2014-04-30-1]),「#1940. 16世紀の綴字論者の系譜」 ([2014-08-19-1]),「#2043. 英語綴字の表「形態素」性」 ([2014-11-30-1]).)

フランス語の状況に関しては,当然ながら英語史ではなくフランス語史の領域なので,フランス語史概説書に当たってみた.以下,Perret (138) を引用しよう.まずは,古仏語の書記体系は表音的であるというくだりから.

L'ancien français : une écriture phonétique

. . . . dans la mesure où l'on disposait de graphèmes pour rendre les son que l'on entendait, l'écriture était simplement phonétique (feré pour fairé, souvent kí pour quí) . . . .

Perret (138--39) は続けて,中仏語の書記体系の表語性について次のように概説している.

Le moyen français : une écriture idéographique

À partir du XIIIe siècle, la transmission des textes cesse d'être uniquement orale, la prose commence à prendre de l'importance : on écrit aussi des textes juridiques et administratifs en français. Avec la prose apparaît une ponctuation très différente de celle que nous connaissons : les textes sont scandés par des lettrines de couleur, alternativement rouges et bleues, qui marquent le plus souvent des débuts de paragraphes, mais pas toujours, et des points qui correspondent à des pauses, généralement en fin de syntagme, mais pas forcément en fin de phrase. Les manuscrits deviennent moins rares et font l'objet d'un commerce, ils ne sont plus recopiés par des moines, mais des scribes séculiers qui utilisent une écriture rapide avec de nombreuses abréviations. On change d'écriture : à l'écriture caroline succèdent les écritures gothique et bâtarde dans lesquelles certains graphèmes (les u, n et m en particulier) sont réduits à des jambages. C'est à partir de ce moment qu'apparaissent les premières transformations de l'orthographe, les ajouts de lettres plus ou moins étymologiques qui ont parfois une fonction discriminante. C'est entre le XIVe et le XVIe siècle que s'imposent les orthographes hiver, pied, febve (où le b empêche la lecture ‘feue’), mais (qui se dintingue ainsi de mes); c'est alors aussi que se développent le y, le x et le z à la finale des mots. Mais si certains choix étymologiques ont une fonction discrminante réelle, beaucoup semblent n'avoir été ajoutés, pour le plaisir des savants, qu'afin de rapprocher le mot français de son étymon latin réel ou supposé (savoir s'est alors écrit sçavoir, parce qu'on le croyait issu de scire, alors que ce mot vient de sapere). C'est à ce moment que l'orthographe française devient de type idéographique, c'est-à-dire que chaque mot commence à avoir une physionomie particulière qui permet de l'identifier par appréhension globale. La lecture à haute voix n'est plus nécessaire pour déchiffrer un texte, les mots peuvent être reconnus en silence par la méthode globale.

引用の最後にあるように,表語文字体系の発達を黙読習慣の発達と関連づけているところが実に鋭い洞察である.声に出して読み上げる際には,発音に素直に結びつく表音文字体系のほうがふさわしいだろう.しかし,音読の機会が減り,黙読が通常の読み方になってくると,内容理解に直結しやすいと考えられる表語(表意)文字体系がふさわしいともいえる (cf. 「#1655. 耳で読むのか目で読むのか」 ([2013-11-07-1]),「#1829. 書き言葉テクストの3つの機能」 ([2014-04-30-1])) .音読から黙読への転換が,表音文字から表語文字への転換と時期的におよそ一致するということになれば,両者の関係を疑わざるを得ない.

フランス語にせよ英語にせよ,語源的綴字はルネサンス期のラテン語熱との関連で論じられるのが常だが,文字論の観点からみれば,表音から表語への書記体系のタイポロジー上の転換という問題ともなるし,書物文化史の観点からみれば,音読から黙読への転換という問題ともなる.<doubt> の <b> の背後には,実に学際的な世界が広がっているのである.

・ Perret, Michèle. Introduction à l'histoire de la langue française. 3rd ed. Paris: Colin, 2008.

2014-12-14 Sun

■ #2057. 中世フランス語と英語における語源的綴字の関係 (2) [etymological_respelling][spelling][french][latin][scribe][anglo-norman][renaissance]

昨日の記事に引き続き,英仏両言語における語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の関係について.Scragg (52--53) は,次のように述べている.

Throughout the Middle Ages, French scribes were very much aware of the derivation of their language from Latin, and there were successive movements in France for the remodelling of spelling on etymological lines. A simple example is pauvre, which was written for earlier povre in imitation of Latin pauper. Such spellings were particularly favoured in legal language, because lawyers' clerks were paid for writing by the inch and superfluous letters provided a useful source of income. Since in France, as in England, conventional spelling grew out of the orthography of the chancery, at the heart of the legal system, many etymological spellings became permanently established. Latin was known and used in England throughout the Middle Ages, and there was a considerable amount of word-borrowing from it into English, particularly in certain registers such as that of theology, but since the greater part of English vocabulary was Germanic, and not Latin-derived, it is not surprising that English scribes were less affected by the etymologising movements than their French counterparts. Anglo-Norman, the dialect from which English derived much of its French vocabulary, was divorced from the mainstream of continental French orthographic developments, and any alteration in the spelling of Romance elements in the vocabulary which occurred in English in the fourteenth century was more likely to spring from attempts to associate Anglo-Norman borrowings with Parisian French words than from a concern with their Latin etymology. Etymologising by reference to Latin affected English only marginally until the Renaissance thrust the classical language much more positively into the centre of the linguistic arena.

重要なポイントをまとめると,

(1) 中世フランス語におけるラテン語源を参照しての文字の挿入は,写字生の小金稼ぎのためだった.

(2) フランス語に比べれば英語にはロマンス系の語彙が少なく(相対的にいえば確かにその通り!),ラテン語源形へ近づけるべき矯正対象となる語もそれだけ少なかったため,語源的綴字の過程を経にくかった,あるいは経るのが遅れた (cf. 「#653. 中英語におけるフランス借用語とラテン借用語の区別」 ([2011-02-09-1])) .

(3) 14世紀の英語の語源的綴字は,直接ラテン語を参照した結果ではなく,Anglo-Norman から離れて Parisian French を志向した結果である.

(4) ラテン語の直接の影響は,本格的にはルネサンスを待たなければならなかった.

では,なぜルネサンス期,より具体的には16世紀に,ラテン語源形を直接参照した語源的綴字が英語で増えたかという問いに対して,Scragg (53--54) はラテン語彙の借用がその時期に著しかったからである,と端的に答えている.

As a result both of the increase of Latinate vocabulary in English (and of Greek vocabulary transcribed in Latin orthography) and of the familiarity of all literate men with Latin, English spelling became as affected by the etymologising process as French had earlier been.

確かにラテン語彙の大量の流入は,ラテン語源を意識させる契機となったろうし,語源的綴字への影響もあっただろうとは想像される.しかし,語源的綴字の潮流は前時代より歴然と存在していたのであり,単に16世紀のラテン語借用の規模の増大(とラテン語への親しみ)のみに言及して,説明を片付けてしまうのは安易ではないか.英語における語源的綴字の問題は,より大きな歴史的文脈に置いて理解することが肝心なように思われる.

・ Scragg, D. G. A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974.

2014-12-13 Sat

■ #2056. 中世フランス語と英語における語源的綴字の関係 (1) [etymological_respelling][spelling][french][latin][hypercorrection][renaissance][hfl]

中英語期から近代英語期にかけての英語の語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の発生と拡大の背後には,対応するフランス語での語源的綴字の実践があった.このことについては,「#653. 中英語におけるフランス借用語とラテン借用語の区別」 ([2011-02-09-1]),「#1156. admiral の <d>」 ([2012-06-26-1]),「#1790. フランスでも16世紀に頂点を迎えた語源かぶれの綴字」 ([2014-03-22-1]),「#1942. 語源的綴字の初例をめぐって」 ([2014-08-21-1]) などの記事で触れてきたとおりである.

したがって,英語におけるこの問題を突き詰めようとすれば,フランス語史を参照せざるをえない.14--16世紀の中世フランス語の語源的綴字の実践について,Zink (24--25) を引用しよう.

Latinisation et surcharge graphique. --- L'idée de rapprocher les mots français de leurs étymons latins ne date pas de la Renaissance. Le mouvement de latinisation a pris naissance à la fin du XIIIe siécle avec les emprunts opérés par la langue juridique au droit romain sous forme de calques à peine francisés.... Parti du vocabulaire savant, il a gagné progressivement les mots courants de l'ancien fonds. Il ne pouvait s'agir dans ce dernier cas que de réfections purement graphiques, sans incidence sur la prononciation ; aussi est-ce moins le vocalisme qui a été retouché que le consonantisme par l'insertion de graphèmes dans les positions où on ne les prononçait plus : finale et surtout intérieure implosive.

Ainsi s'introduisent avec le flot des emprunts savants : adjuger, exception (XIIIe s.) ; abstraire, adjonction, adopter, exemption, subjectif, subséquent. . . (mfr., la prononciation actuelle datant le plus souvent du XVIe s.) et l'on rhabille à l'antique une foule de mots tels que conoistre, destre, doter, escrit, fait, nuit, oscur, saint, semaine, soissante, soz, tens en : cognoistre, dextre, doubter, escript, faict, nuict, obscur, sainct, sepmaine, soixante, soubz, temps d'après cognoscere, dextra, dubitare, scriptum, factum, noctem, obscurum, sanctum, septimana, sexaginta, subtus, tempus.

Le souci de différencier les homonymes, nombreux en ancien français, entre aussi dans les motivations et la langue a ratifié des graphies comme compter (qui prend le sens arithmétique au XVe s.), mets, sceau, sept, vingt, bien démarqués de conter, mais/mes, seau/sot, sait, vint.

Toutefois, ces correspondances supposent une connaissance étendue et précise de la filiation des mot qui manque encore aux clercs du Moyen Age, d'où des tâtonnements et des erreurs. Les rapprochements fautifs de abandon, abondant, oster, savoir (a + bandon, abundans, obstare, sapere) avec habere, hospitem (!), scire répandent les graphies habandon, habondant, hoster, sçavoir (à toutes les formes). . . .

要点としては,(1) フランス語ではルネサンスに先立つ13世紀末からラテン語借用が盛んであり,それに伴ってラテン語に基づく語源的綴字も現われだしていたこと,(2) 語末と語中の子音が脱落していたところに語源的な子音字を復活させたこと,(3) 語源的綴字を示すいくつかの単語が英仏両言語において共通すること,(4) フランス語の場合には語源的綴字は同音異義語どうしを区別する役割があったこと,(5) フランス語でも語源的綴字に基づき,それを延長させた過剰修正がみられたこと,が挙げられる.これらの要点はおよそ英語の語源的綴字を巡る状況にもあてはまり,英仏両言語の類似現象が関与していること,もっと言えばフランス語が英語へ影響を及ぼしたことが示唆される.(5) に挙げた過剰修正 (hypercorrection) の英語版については,「#1292. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ」 ([2012-11-09-1]),「#1899. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ (3)」 ([2014-07-09-1]),「#1783. whole の <w>」 ([2014-03-15-1]) も参照されたい.

語源的綴字を巡る状況に関して英仏語で異なると思われるのは,上記 (4) だろう.フランス語では,語源的綴字の導入は,同音異義語 (homonymy) を区別するのに役だったという.換言すれば,書記において同音異義衝突 (homonymic_clash) を避けるために,語源的原則に基づいて互いに異なる綴字を導入したということである.ラテン語からロマンス諸語へ至る過程で生じた数々の音韻変化の結果,フランス語では単音節の同音異義語が大量に生じるに至った.この問題を書記において解決する策として,語源的綴字が利用されたのである.日本語のひらがなで「こうし」と書いてもどの「こうし」か区別が付かないので,漢字で「講師」「公私」「嚆矢」などと書き分ける状況と似ている.ここにおいてフランス語の書記体系は,従来の表音的なものから,表語的なものへと一歩近づいたといえるだろう.

英語では同音異義衝突を避けるために語源的綴字を導入するという状況はなかったように思われるが,機能主義的な語源的綴字の動機付けという点については,もう少し注意深く考察する価値がありそうだ.

・ Zink, Gaston. ''Le moyen françis (XIVe et XV e siècles)''. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1990.[sic]

2014-11-05 Wed

■ #2018. <nacio(u)n> → <nation> の綴字変化 [spelling][latin][etymological_respelling][corpus][hc][eebo]

近現代英語で <nation> と綴られる語は,中英語では主として <nacio(u)n> と綴られていた.<nacio(u)> → <nation> の変化は,具体的にはなぜ,いつ,どのように生じたのだろうか.ここでは母音字 <ou> → <o> の変化と,子音字 <c> → <t> の変化を分けて考える必要がある.

まず母音字の変化について考えよう.中尾 (331) によると,俗ラテン語において /o/ + 鼻音で終わる閉音節は,対応する Norman French の形態では鼻母音化した短母音 /ʊ/ あるいは長母音 /uː/ を示した.この音をもつ語が中英語へ借用されると,round, troumpe, count, nombre, countrefeten, countour, cuntree, counseil, commissioun, condicioun, nacioun, resoun, sesoun, religioun などと綴られた.-<sioun> や -<tioun> の発音は,対応する現代の -<sion> や -<tion> の発音 /ʃ(ə)n/ とは異なり,いまだ同化も弱化もしておらず,完全な音価 /siuːn/ を保っていたと考えられる.後期中英語から初期近代英語にかけてこの音節に強勢が落ちなくなってくると,同化や弱化が始まり,現在の /ʃ(ə)n/ に近づいていったろう.この過程で長母音を示唆する綴字 -<ioun> はふさわしくないと感じられ,1文字を落として -<ion> とするのが一般化したと想像される.

しかし,<ou> → <o> の変化が単に発音と綴字を一致させるべく生じたものであるという説明が妥当かどうかは検証の余地がある.そこには多少なりとも語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の作用があったのではないか.というのは,ME nacioun が後に nation へ変化したとき,変化したのは問題の母音字だけではなく,先行する子音字の <c> から <t> への変化もろともだったからである.Upward and Davidson (97) によると,

The letter C with the value /s/ before E and I in OFr had two main sources. One was Lat C: Lat certanus > certain. The other was Lat T, which before unstressed E, I acquired the same value, /ts/, as C had in LLat. Medieval Lat commonly alternated T and C in such cases: nacionem or nationem, whence the widespread use of forms such as nacion in OFr and ME. The C adopted in LLat, OFr and ME for classical Lat T has sometimes survived into ModE: Lat spatium > space; platea > place. Elsewhere, a later preference for classical Lat etymology has led to the restoration of T in place of C, as in the -TION endings: ModE nation.

つまり,<nacio(u)n> → <nation> における母音字の変化も子音字の変化も,古典ラテン語の綴字に一致させるべく生じたものではないか.

この綴字変化がいつ,どのように生じたかについて,歴史コーパスを用いて調査してみた.まずは Helsinki Corpus に当たって,次の結果を得た(以下の検索では,いずれも複数語尾のついた綴字なども一緒に拾ってある).件数は少ないものの,16世紀が変化の時期だったことがうかがわれる.

| <nacion> (<nacioon>) | <nation> | |

|---|---|---|

| M2 (1250--1350) | 0 (1) | 0 |

| M3 (1350--1420) | 7 (1) | 0 |

| M4 (1420--1500) | 2 (0) | 0 |

| E1 (1500--1569) | 2 (0) | 2 |

| E2 (1570--1639) | 0 (0) | 13 |

| E3 (1640--1710) | 0 (0) | 14 |

前回と同様,初期近代英語期 (1418--1680) の約45万語からなる書簡コーパスのサンプル CEECS (The Corpus of Early English Correspondence でも検索してみたが,大雑把な年代区分で仕分けした限り,明確な結果の解釈は難しい.

| <nacion> | <nation> | |

|---|---|---|

| CEECS1 (1418--1638) | 2 | 12 |

| CEECS2 (1580--1680) | 1 | 27 |

有用な結果を得ることができたのは,EEBO (Early English Books Online) からのテキストを蓄積して個人的に作っている巨大なデータベースの検索によってである.半世紀ごとに区分した各サブコーパスの規模はそれぞれ異なるので,通時的な数値の単純比較はできないが,それぞれの時代における異綴字の相対的な分布は一目瞭然だろう.

| <nacion> | <nacioun> | <nation> | <natioun> | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1451--1500 (123,537 words) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1501--1550 (1,825,565 words) | 90 | 0 | 82 | 0 |

| 1551--1600 (6,648,588 words) | 64 | 0 | 947 | 13 |

| 1601--1650 (21,296,378 words) | 18 | 0 | 6,451 | 0 |

| 1651--1700 (38,545,254 words) | 11 | 0 | 22,350 | 1 |

| 1701--1750 (33,741 words) | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 |

母音字については,初期近代英語期の入り口までにすでに <-ioun> 形はほぼ廃れていたようである.そして,子音字については,16世紀中に一気に <t> が <c> を置き換えていった様子がわかる.少なくともこの子音字の変化のタイミングについては,一般に語源的綴字の最盛期といわれる16世紀に一致していることは指摘しておいてよいだろう.一方,母音字の変化については,語源的綴字による説明を排除するわけではないが,生じた時期が相対的に早かったことから,先述のとおり発音と綴字を一致させようという動機づけに基づいていた可能性が高いのではないか.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

2014-09-08 Mon

■ #1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造 [register][lexicology][loan_word][latin][french][greek][semantics][polysemy][lexical_stratification]

英語語彙に特徴的な三層構造について,「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]),「#335. 日本語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-28-1]),「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1]) などの記事でみてきた.三層構造という表現が喚起するのは,上下関係と階層のあるビルのような建物のイメージかもしれないが,ビルというよりは,裾野が広く頂点が狭いピラミッドのような形を想像するほうが妥当である.つまり,下から,裾野の広い低階層の本来語彙,やや狭まった中階層のフランス語彙,そして著しく狭い高階層のラテン・ギリシア語彙というイメージだ.

ピラミッドの比喩が適切なのは,1つには,高階層のラテン・ギリシア語彙のもつ特権的な地位と威信がよく示されているからだ.社会言語学的,文体的に他を圧倒するポジションについていることは,ビル型よりもピラミッド型のほうがよく表現できる.

2つ目として,それぞれの語彙の頻度が,ピラミッドにおける各階層の面積として表現できるからである.昨日の記事「#1959. 英文学史と日本文学史における主要な著書・著者の用いた語彙における本来語の割合」 ([2014-09-07-1]) でみたように,話し言葉のみならず書き言葉においても,本来語彙の頻度は他を圧倒している(なお,この分布は,「#1645. 現代日本語の語種分布」 ([2013-10-28-1]) でみたように,現代日本語においても同様だった).対照的に,高階層の語彙は頻度が低い.個々の語については反例もあるだろうが,全体的な傾向としては,各階層の頻度と面積とは対応する.もっとも,各階層の語彙量(異なり語数)ということでいえば,必ずしもそれがピラミッドの面積に対応するわけでない.最頻100語(cf. 「#309. 現代英語の基本語彙100語の起源と割合」 ([2010-03-02-1]) と最頻600語(cf. 「#202. 現代英語の基本語彙600語の起源と割合」 ([2009-11-15-1]))で見る限り,語彙量と面積はおよそ対応しているが,10000語というレベルで調査すると,「#429. 現代英語の最頻語彙10000語の起源と割合」 ([2010-06-30-1]) でみたように,上で前提としてきた3階層の上下関係は崩れる.

ピラミッドの比喩が有効と考えられる3つ目の理由は,ピラミッドにおける各階層の面積が,頻度のみならず,構成語のもつ意味と用法の広さにも対応しているからだ.本来語は相対的に卑近であり頻度も高いが,そればかりでなく,多義であり,用法が多岐にわたる.基本的な語義が同じ「与える」でも,本来語 give は派生的な語義も多く極めて多義だが,ラテン借用語 donate は語義が限定されている.また,give は文型として SVOiOd も SVOd to Oi も取ることができる(すなわち dative shift が可能だ)が,donate は後者の文型しか許容しない.ほかには「#112. フランス・ラテン借用語と仮定法現在」 ([2009-08-17-1]) で示唆したように,語彙階層が統語的な振る舞いに関与していると疑われるケースがある.

この第3の観点から,Hughes (43) は,次のようなピラミッド構造を描いた.

![]()

上記の3点のほかにも,各階層の面積と語の理解しやすさ (comprehensibility) が関係しているという見方もある.結局のところ,語彙階層は,基本性,日常性,文体的威信の低さ,頻度,意味・用法の広さといった諸相と相関関係にあるということだろう.ピラミッドの比喩は巧みである.

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-08-24 Sun

■ #1945. 古英語期以前のラテン語借用の時代別分類 [typology][loan_word][latin][oe][christianity][borrowing][statistics]

「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1]),「#1437. 古英語期以前に借用されたラテン語の例」 ([2013-04-03-1]) に続いて,古英語のラテン借用語の話題.古英語におけるラテン借用語の数は,数え方にもよるが,数百個あるといわれる.諸研究を参照した Miller (53) は,その数を600--700個ほどと見積もっている.

Old English had some 600--700 loanwords from Latin, about 500 of which are common to Northwest Germanic . . ., and 287 of which are ultimately from Greek, seventy-nine via Christianity . . . .

個数とともに確定しがたいのはそれぞれの借用語の借用年代である.[2013-04-03-1]の記事では,Serjeantson に従って借用年代を (i) 大陸時代,(ii) c. 450--c. 650, (iii) c. 650--c. 1100 と3分して示した.これは多くの論者によって採用されている伝統的な時代別分類である.これとほぼ重なるが,第4の借用の波を加えた以下の4分類も提案されている.

(1) continental borrowings

(2) insular borrowings during the settlement phase [c. 450--600]

(3) borrowings [600+] from christianization

(4) learned borrowings that accompanied and followed the Benedictine Reform [c10e]

この4分類をさらに細かくした Dennis H. Green (Language and History in the Early Germanic World. Cambridge: CUP, 1998.) による区分もあり,Miller (54) が紹介している.それぞれの特徴について Miller より引用し,さらに簡単に注を付す.

(1a) an early continental phase, when the Angles and Saxons were in Schleswig-Holstein (contact with merchants) and on the North Sea littoral as far as the mouth of the Ems (direct contact with the Romans)

数は少なく,主として商業語が多い.ローマからの商品,器,道具など.wine が典型例.

(1b) a later continental period, when the Angles and Saxons had penetrated to the litus Saxonicum (Flanders and Normandy)

ライン川河口以西でローマ人との直接接触して借用されたと思われる street, tile が典型例.

(2a) an early phase, featuring possible borrowing via Celtic

この時期に属すると思われる例は,ガリアで話されていた俗ラテン語と音声的に一致しており,ブリテン島での借用かどうかは疑わしいともいわれる.

(2b) a later phase, with loans from the continental Franks as part of their influence across the Channel, especially on Kent

(3) begins "with the coming of Augustine and his 40 companions in 597, and possibly even at an earlier date, with the arrival of Bishop Liudhard in the retinue of Queen Bertha of Kent in the 560s"

この時期の借用語は古英語期以前の音韻変化をほとんど示さない点で,他の時期のものと異なっている.多くは教会ラテン借用語である.

(4) of a learned nature, culled from classical Latin texts, and differ little from the classical written form

実際には,ここまで細かく枠を設定しても,ある借用語をいずれの枠にはめるべきかを確信をもって決することは難しい.continental か insular かという大雑把な分類ですら難しく,さらに曖昧に early か later くらいが精一杯ということも少なくない.

・ Miller, D. Gary. External Influences on English: From its Beginnings to the Renaissance. Oxford: OUP, 2012.

2014-08-21 Thu

■ #1942. 語源的綴字の初例をめぐって [etymological_respelling][spelling][french][latin][hart]

昨日の記事「#1941. macaronic code-switching としての語源的綴字?」 ([2014-08-20-1]) に引き続き,etymological_respelling の話題.英語史では語源的綴字は主に16--17世紀の話題として認識されている(cf. 「#1387. 語源的綴字の採用は17世紀」 ([2013-02-12-1])).しかし,それより早い例は14--15世紀から確認されているし,「#653. 中英語におけるフランス借用語とラテン借用語の区別」 ([2011-02-09-1]),「#1790. フランスでも16世紀に頂点を迎えた語源かぶれの綴字」 ([2014-03-22-1]) でみたように,お隣フランスでもよく似た現象が13世紀後半より生じていた.実際にフランスでも語源的綴字は16世紀にピークを迎えたので,この現象について,英仏語はおよそ歩調を合わせていたことになる.

フランス語側での語源的綴字について詳しく調査していないが,Miller (211) は14世紀終わりからとしている.

Around the end of C14, French orthography began to be influenced by etymology. For instance, doute 'doubt' was written doubte. Around the same time, such etymologically adaptive spellings are found in English . . . ., especially by C16. ME doute [?a1200] was altered to doubt by confrontation with L dubitō and/or contemporaneous F doubte, and the spelling remained despite protests by orthoepists including John Hart (1551) that the word contains an unnecessary letter . . . .

フランス語では以来 <doubte> が続いたが,17世紀には再び <b> が脱落し,現代では doute へ戻っている.

では,英語側ではどうか.doubt への <b> の挿入を調べてみると,MED の引用文検索によれば,15世紀から多くの例が挙がるほか,14世紀末の Gower からの例も散見される.

同様に,OED でも <doubt> と引用文検索してみると,15世紀からの例が少なからず見られるほか,14世紀さらには1300年以前の Cursor Mundi からの例も散見された.『英語語源辞典』では,doubt における <b> の英語での挿入は15世紀となっているが,実際にはずっと早くからの例があったことになる.

・ a1300 Cursor M. (Edinb.) 22604 Saint peter sal be domb þat dai,.. For doubt of demsteris wrek [Cott. wreke].

・ 1393 J. Gower Confessio Amantis I. 230 First ben enformed for to lere A craft, which cleped is facrere. For if facrere come about, Than afterward hem stant no doubt.

・ 1398 J. Trevisa tr. Bartholomew de Glanville De Proprietatibus Rerum (1495) xvi. xlvii. 569 No man shal wene that it is doubt or fals that god hath sette vertue in precyous stones.

だが,さすがに初期中英語コーパス ,LAEME からは <b> を含む綴字は見つからなかった.

・ 寺澤 芳雄 (編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

・ Miller, D. Gary. External Influences on English: From its Beginnings to the Renaissance. Oxford: OUP, 2012.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow