2014-08-20 Wed

■ #1941. macaronic code-switching としての語源的綴字? [etymological_respelling][code-switching][bilingualism][latin][silent_letter][etymology][borrowing][grapheme]

中英語期には英仏羅の間で言語の切り替え code-switching が起こるテキストがあることを,「#1470. macaronic lyric」 ([2013-05-06-1]),「#1625. 中英語期の書き言葉における code-switching」 ([2013-10-08-1]) の記事でみた.ジャンルとしては宗教的な韻文や散文,また書簡などの事例があるが,これらが著者によるランダムな切り替えなのか,あるいは切り替えに際して何らかの "social and discourse-pragmatic reasons" があったのかが問題となる(cf. 「#1627. code-switching と code-mixing」 ([2013-10-10-1])).

通常,上記の macaronic code-switching で問題とされるのは,語句,節,文といった比較的大きな言語単位で一方の言語から他方の言語へ切り替わる場合だが,より小さな単位,例えば形態素や音素(文字素)という単位での macaronic code-switching はありうるのだろうか.もしあるとすれば,そこにも何らかの "social and discourse-pragmatic reasons" が関わっていると考えられるのだろうか.

Miller (211) は,<doubt> (cf. ME <doute>) に見られるような語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) はもしかすると macaronic code-switching により生じたものかもしれないと推測している.

Some changes may be due to the macaronic codeswitching between Medieval Latin and Late Middle English in certain poetic texts and especially London accounting records . . . .

しかし,この推測が妥当かどうかを決めることは難しい.<doubt> や <receipt> のように <b> や <p> を挿入する行為は,実に細微な点をついたラテン語かぶれの行為である.より大きな言語単位での英羅間の切り替えが頻繁に起こっていない限り,この細微さが物語るのは,著者が流ちょうな2言語使用者ではなくラテン語を外国語として(不十分に)学んだ英語話者だということだろう.ラテン語の語源形を参照した文字の挿入を macaronic code-switching と呼ぶべきかどうかは,畢竟,その定義にかかってくる.しかし,code-switching とは何かを考え始めれば,bilingualism とは何かという頭の痛い問題にも至らざるを得ない.また,「#1661. 借用と code-switching の狭間」 ([2013-11-13-1]) の問題も関わってこよう.<b> や <p> が初めて挿入されたとき,それははたして macaronic code-switching の現われなのか,あるいはラテン語形の借用なのか.そして,いずれにせよ,そこに社会的・語用論的な意図はあったのか.

この挿入がある程度慣習化してくると,語源主義,綴字論,衒学的風潮に裏打ちされて「社会的・語用論的な意義」が付加されることにはなったろう.しかし,初めて挿入されたときに,そのような意義や意図があったかどうかは,推測の域を出ない.

以上を考察した上で,次のような感想をもった.(1) code-switching が文字という小さな単位で起こり得るかどうか疑わしい.(2) 「#653. 中英語におけるフランス借用語とラテン借用語の区別」 ([2011-02-09-1]) でみたフランス語における類例が示唆するように,中途半端なラテン語の知識に基づく混用とみなすことで十分ではないか.(3) 結果として後に,<b> や <p> の挿入に社会的・語用論的な意義が付された点こそが重要なのであって,その過程が code-switching か借用かなどの問題は各々の定義の問題であり,それほど重要ではない.ただし,挿入の過程に macaronic text の存在を考えてみる視点はなかったので,新鮮な推測ではある.

・ Miller, D. Gary. External Influences on English: From its Beginnings to the Renaissance. Oxford: OUP, 2012.

2014-08-09 Sat

■ #1930. 系統と影響を考慮に入れた西インドヨーロッパ語族の関係図 [indo-european][family_tree][contact][loan_word][borrowing][geolinguistics][linguistic_area][historiography][french][latin][greek][old_norse]

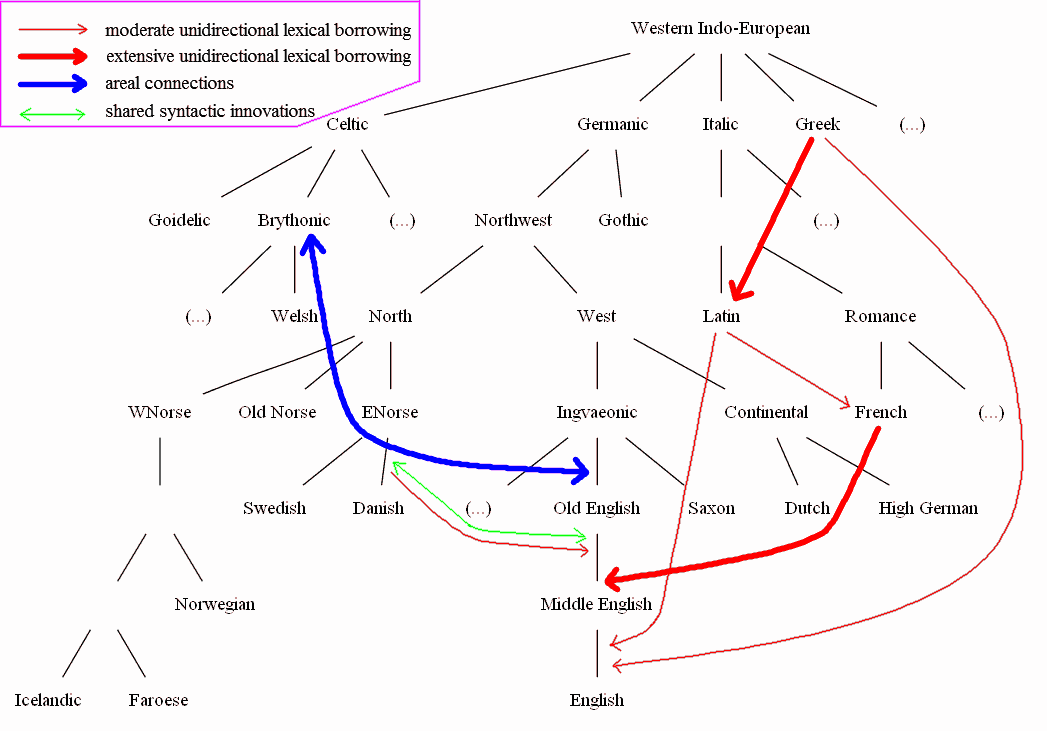

「#999. 言語変化の波状説」 ([2012-01-21-1]),「#1118. Schleicher の系統樹説」 ([2012-05-19-1]),「#1236. 木と波」 ([2012-09-14-1]),「#1925. 語派間の関係を示したインドヨーロッパ語族の系統図」 ([2014-08-04-1]) で触れてきたように,従来の言語系統図の弱点として,言語接触 (language contact) や地理的な隣接関係に基づく言語圏 (linguistic area; cf. 「#1314. 言語圏」 [2012-12-01-1])がうまく表現できないという問題があった.しかし,工夫次第で,系統図のなかに他言語からの影響に関する情報を盛り込むことは不可能ではない.Miller (3) がそのような試みを行っているので,見やすい形に作図したものを示そう.

この図では,英語が歴史的に経験してきた言語接触や地理言語学的な条件がうまく表現されている.特に,主要な言語との接触の性質,規模,時期がおよそわかるように描かれている.まず,ラテン語,フランス語,ギリシア語からの影響が程度の差はあれ一方的であり,語彙的なものに限られることが,赤線の矢印から見て取れる.古ノルド語 (ENorse) との言語接触についても同様に赤線の一方向の矢印が見られるが,緑線の双方向の矢印により,構造的な革新において共通項の少なくないことが示唆されている.ケルト語 (Brythonic) との関係については,近年議論が活発化してきているが,地域的な双方向性のコネクションが青線によって示されている.

もちろん,この図も英語と諸言語との影響の関係を完璧に示し得ているわけではない.例えば,矢印で図示されているのは主たる言語接触のみである(矢印の種類と数を増やして図を精緻化することはできる).また,フランス語との接触について,中英語以降の継続的な関与はうまく図示されていない.それでも,この図に相当量の情報が盛り込まれていることは確かであり,英語史の概観としても役に立つのではないか.

・ Miller, D. Gary. External Influences on English: From its Beginnings to the Renaissance. Oxford: OUP, 2012.

2014-07-09 Wed

■ #1899. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ (3) [etymological_respelling][h][spelling][orthography][latin]

「#1292. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ」 ([2012-11-09-1]),「#1675. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ (2)」 ([2013-11-27-1]),「#1677. 語頭の <h> の歴史についての諸説」 ([2013-11-29-1]) などに引き続いての話題.

昨日の記事「#1898. ラテン語にもあった h-dropping への非難」 ([2014-07-08-1]) で取り上げたように,後期ラテン語にかけて /h/ の脱落が生じていた.過剰修正 (hypercorrection) もしばしば起こる始末で,脱落傾向は止めようもなく,その結果は後のロマンス諸語にも反映されることになった.すなわち,古典ラテン語の正書法上の <h> に対応する子音は,フランス語を含むロマンス諸語へ無音として継承され,フランス語を経由して英語へも受け継がれた.ところが,ラテン語正書法の綴字 <h> そのものは長い規範主義の伝統により,完全に失われることはなく中世ヨーロッパの諸言語へも伝わった.結果として,中世において,自然の音韻変化の結果としての無音と人工的な規範主義を体現する綴字 <h> とが,長らく競い合うことになった.

英語でも,ラテン語に由来する語における <h> の保持と復活は中英語期より意識されてきた問題だった.「#1292. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ」 ([2012-11-09-1]) で触れたように,これは初期近代英語期に盛んにみられることになる語源的綴り字 (etymological_respelling) の先駆けとして,英語史上評価されるべき現象だろう.この点については Horobin (80--81) も以下のようにさらっと言及しているのみだが,本来はもっと評価が高くあって然るべきだと思う.

Because of the loss of initial /h/ in French, numerous French loanwords were borrowed into Middle English without an initial /h/ sound, and were consequently spelled without an initial <h>; thus we find the Middle English spellings erbe 'herb', and ost 'host'. But, because writers of Middle English were aware of the Latin origins of these words, they frequently 'corrected' these spellings to reflect their Classical spelling. As a consequence, there is considerable variation and confusion about the spelling of such words, and we regularly find pairs of spellings like heir, eyr, here, ayre, ost, host. The importance accorded to etymology in determining the spelling of such words led ultimately to the spellings with initial <h> becoming adopted; in some cases the initial /h/ has subsequently been restored in the pronunciation, so that we now say hotel and history, while the <h> remains silent in French hôtel and histoire.

近現代英語ならずとも歴史英語における h-dropping は扱いにくい問題だが,一般に考えられているよりも早い段階で語源的綴り字が広範に関与している例として,英語史上,掘り下げる意義のあるトピックである.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2014-07-08 Tue

■ #1898. ラテン語にもあった h-dropping への非難 [latin][etymological_respelling][h][spelling][orthography][prescriptive_grammar][hypercorrection][substratum_theory][etruscan][stigma]

英語史における子音 /h/ の不安定性について,「#214. 不安定な子音 /h/」 ([2009-11-27-1]) ,「#459. 不安定な子音 /h/ (2)」 ([2010-07-30-1]) ,「#494. hypercorrection による h の挿入」 ([2010-09-03-1]),「#1292. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ」 ([2012-11-09-1]),「#1675. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ (2)」 ([2013-11-27-1]),「#1677. 語頭の <h> の歴史についての諸説」 ([2013-11-29-1]) ほか,h や h-dropping などの記事で多く取り上げてきた.

近代英語以後,社会言語学的な関心の的となっている英語諸変種の h-dropping の起源については諸説あるが,中英語期に,<h> の綴字を示すものの決して /h/ とは発音されないフランス借用語が,大量に英語へ流れ込んできたことが直接・間接の影響を与えてきたということは,認めてよいだろう.一方,フランス語のみならずスペイン語やイタリア語などのロマンス諸語で /h/ が発音されないのは,後期ラテン語の段階で同音が脱落したからである.したがって,英語の h-dropping を巡る話題の淵源は,時空と言語を超えて,最終的にはラテン語の1つの音韻変化に求められることになる.

おもしろいことに,ラテン語でも /h/ の脱落が見られるようになってくると,ローマの教養人たちは,その脱落を通俗的な発音習慣として非難するようになった.このことは,正書法として <h> が綴られるべきではないところに <h> が挿入されていることを嘲笑する詩が残っていることから知られる.この詩は h-dropping に対する過剰修正 (hypercorrection) を皮肉ったものであり,それほどまでに h-dropping が一般的だったことを示す証拠とみなすことができる.この問題の詩は,古代ローマの抒情詩人 Gaius Valerius Catullus (84?--54? B.C.) によるものである.以下,Catullus Poem 84 より和英対訳を掲げる.

1 CHOMMODA dicebat, si quando commoda uellet ARRIUS, if he wanted to say "winnings " used to say "whinnings", 2 dicere, et insidias Arrius hinsidias, and for "ambush" "hambush"; 3 et tum mirifice sperabat se esse locutum, and thought he had spoken marvellous well, 4 cum quantum poterat dixerat hinsidias. whenever he said "hambush" with as much emphasis as possible. 5 credo, sic mater, sic liber auunculus eius. So, no doubt, his mother had said, so his uncle the freedman, 6 sic maternus auus dixerat atque auia. so his grandfather and grandmother on the mother's side. 7 hoc misso in Syriam requierant omnibus aures When he was sent into Syria, all our ears had a holiday; 8 audibant eadem haec leniter et leuiter, they heard the same syllables pronounced quietly and lightly, 9 nec sibi postilla metuebant talia uerba, and had no fear of such words for the future: 10 cum subito affertur nuntius horribilis, when on a sudden a dreadful message arrives, 11 Ionios fluctus, postquam illuc Arrius isset, that the Ionian waves, ever since Arrius went there, 12 iam non Ionios esse sed Hionios are henceforth not "Ionian," but "Hionian."

問題となる箇所は,1行目の <commoda> vs <chommoda>,2行目の <insidias> vs <hinsidias>, 12行目の <Ionios> vs <Hionios> である.<h> の必要のないところに <h> が綴られている点を,過剰修正の例として嘲っている.皮肉の効いた詩であるからには,オチが肝心である.この詩に関する Harrison の批評によれば,12行目で <Inoios> を <Hionios> と(規範主義的な観点から見て)誤った綴字で書いたことにより,ここにおかしみが表出しているという.Harrison は ". . . the last word of the poem should be χιoνέoυς. When Arrius crossed, his aspirates blew up a blizzard, and the sea has been snow-swept ever since." (198--99) と述べており,誤った <Hionios> がギリシア語の χιoνέoυς (snowy) と引っかけられているのだと解釈している.そして,10行目の nuntius horribilis がそれを予告しているともいう.Arrius の過剰修正による /h/ が,7行目の nuntius horribilis に予告されているように,恐るべき嵐を巻き起こすというジョークだ.

Harrison (199) は,さらに想像力をたくましくして,Catullus のようなローマの教養人による当時の h に関する非難の根源は,気音の多い Venetic 訛りに対する偏見,すなわち基層言語の影響 (substratum_theory) による耳障りなラテン語変種に対する否定的な評価にあるのでないかという.同様に Etruscan 訛りに対する偏見という説を唱える論者もいるようだ.これらの見解はいずれにせよ speculation の域を出るものではないが,近現代英語の h-dropping への stigmatisation と重ね合わせて考えると興味深い.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ Harrison, E. "Catullus, LXXXIV." The Classical Review 29.7 (1915): 198--99.

2014-07-05 Sat

■ #1895. 古英語のラテン借用語の綴字と借用の類型論 [spelling][loan_word][borrowing][latin][christianity][typology]

キリスト教の伝来とラテン単語の借用の関係について,「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1]) や「#1437. 古英語期以前に借用されたラテン語の例」 ([2013-04-03-1]) などの記事で取り上げてきた.一方,借用の類型論に関わる話題として,「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]),「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1]),「#903. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語」 ([2011-10-17-1]),「#1619. なぜ deus が借用されず God が保たれたのか」 ([2013-10-02-1]),「#1778. 借用語研究の to-do list」 ([2014-03-10-1]) などの記事を書いてきた.今回は,古英語のラテン借用語の綴字という話題を介して,借用の類型論を考察してみたい.

古英語期には,キリスト教の伝来とともに,多くの宗教用語や学問用語がラテン語から英語の書き言葉へともたらされた.apostol (L apostulus), abbod (L abbadem), fenix (L phoenix), biscop (L episcopus) などである.ここで注意すべきは,借用の際に,発音にせよ綴字にせよ,ラテン語の形態をそのまま借用したのではなく,多分に英語化して取り込んでいることである.ところが,後の10世紀にラテン語借用のもう1つの波があったときには,ラテン単語は英語化されず,ほぼそのままの形態で借用されている.つまり,古英語のラテン語借用の2つの波の間には,質的な差があったことになる.この差を,Horobin (64--65) は次のように指摘している.

What is striking about these loanwords is that their pronunciation and spelling has been assimilated to Old English practices, so that the spelling-sound correspondences were not disturbed. Note, for instance, the spelling mynster, which shows the Old English front rounded vowel /y/, the <æ> in Old English mæsse, indicating the Old English front vowel. The Old English spelling of fenix with initial <f> shows that the word was pronounced the same way as in Latin, but that the spelling was changed to reflect Old English practices. While the spelling of Old English biscop appears similar to that of Latin episcopus, the pronunciation was altered to the /ʃ/ sound, still heard today in bishop, and so the <sc> spelling retained its Old English usage. This process of assimilation can be contrasted with the fate of the later loanword, episcopal, borrowed from the same Latin root in the fifteenth century but which has retained its Latin spelling and pronunciation. However, during the third state of Latin borrowing in the tenth century, a number of words from Classical Latin were borrowed which were not integrated into the native language in the same way. The foreign status of these technical words was emphasized by the preservation of their Latinate spellings and structure, as we can see from a comparison of the tenth-century Old English word magister (Latin magister), with the earlier loan mægester, derived from the same Latin word. Where the earlier borrowing has been respelled according to Old English practices, the later adoption has retained its classical Latin spelling.

借用の種類としては,いずれもラテン語の形態に基づいているという点で substitution ではなく importation である.しかし,同じ importation といっても,前期はモデルから逸脱した綴字による借入,後期はモデルに忠実な綴字による借入であり,importation というスケール内部での程度差がある.いずれも substitution ではないのだが,前者は後者よりも substitution に一歩近い importation である,と表現することはできるかもしれない.話し言葉でたとえれば,前者はラテン単語を英語的発音で取り入れることに,後者は原語であるラテン語の発音で取り入れることに相当する.あらっぽくたとえれば,英単語を日本語へ借用するときにカタカナ書きするか,英語と同じようにアルファベットで綴るか,という問題と同じことだが,古英語の例では,いずれの方法を取るかが時期によって異なっていたというのが興味深い.

借用語のモデルへの近接度という問題に迫る際に,そしてより一般的に借用の類型論を考察する際に,綴字習慣の差というパラメータも関与しうるというのは,新たな発見だった.関連して,語が借用されるときの importation 内部での程度と,借用された後に徐々に示される同化の程度との区別も明確にする必要があるかもしれない.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2014-05-08 Thu

■ #1837. ローマ字とギリシア文字の字形の差異 [alphabet][greek][latin][grammatology][map][dialect]

「#1832. ギリシア・アルファベットの文字の名称 (1)」 ([2014-05-03-1]) の記事で,ギリシア・アルファベット (Greek alphabet) の一覧を示した.ローマン・アルファベット (Roman alphabet) と比べると,文字数,字形,音価において若干の違いが見られるが,この違いの背後にどのような事情があったのだろうか.

まず,一般論を述べておくと,ある言語を表記する文字体系を別の言語へ移植・適用するときには,決まって多少の改変が加えられる.とりわけ,音韻体系をもっともよく反映するアルファベットのような音素文字であれば,なおさらである.まったく同じ音韻体系をもっている言語(方言)はないといってよく,既存の文字セットを移植するときには,必ずいくつかの文字の過剰と不足が生じる.そこで,過剰な文字を新しい音価に割り当てたり,新しい文字を創り出すなどの手段が講じられる.しかし,文字には保守的な側面もあり,総文字数を大きく変化させるような事態には至らないことが多い.アルファベット史をみても,およそ20?40文字の範囲に収まっているようである.ギリシア文字→エトルリア文字→ローマ字とアルファベットが伝播してゆく過程でも多少の改変と本質的な不変が見られるが,これは文字の伝播においては普通に観察されることである.

次に具体論に移ろう.古代におけるギリシア・アルファベットは一枚岩ではなく,多数の方言的変種が存在した.これは,古代ギリシア語の話し言葉が多種多様に方言分化していたのと呼応する.よく言われるように,古代ギリシアは諸都市の独立と自足を特徴とし,後のローマとは対照的に統一国家を生み出すことはなかった.話し言葉や文字体系の方言化も,この独立精神と無関係ではない.話し言葉の方言については「#1454. ギリシャ語派(印欧語族)」 ([2013-04-20-1]) で触れたので繰り返さないが,アルファベットの変種については,細かく分類すれば4種類が区別された.ドイツの学者 Kirchhoff による分類で,地図を4種類の色に塗り分けてその分布を示したことにちなみ,それぞれ色の名前で呼称される慣習がある.Green, Red, Dark blue, Light blue の4変種だ.

(1) Green alphabet は,Crete や近隣の島々で行われた変種で,フェニキア・アルファベット (Phoenician alphabet) への追加文字(他変種におけるΦ,Χ,Ψ)を欠いているのが特徴である.

(2) Red alphabet は,Euboea や Laconia で行われた変種で,Φ [ph], Ψ [kh] の追加文字を加えた.また,ΧはΞに代わって [ks] の音価を表わした.Euboea の都市の名を取って Chalcis 型あるいは西方型の変種と呼ばれる.

(3) Dark blue alphabet は,Ionia, Corinth, Rhodes で広く行われた変種で,Φ [ph], Χ [kh], Ψ [ps] の追加文字を加えた.この Ψ [ps] は,Red alphabet のΨ [kh] と音価が異なることに注意.Ionia 型あるいは東方型の変種と呼ばれる.

(4) Light blue alphabet は,Attica で行われた変種である.Φ [ph], Χ [kh] を追加した.Ionia 型の亜種といってよいが,後に標準的な変種となった.

これを2つに大別すれば,Euboea の Chalcis を中心とする西方型と Ionia の Miletus を中心とする東方型に分けられるだろう.フェニキアの商人が去った後,エーゲ海は Chalcis と Miletus の独占舞台となり,両都市は商業的・植民的覇権を争った.Chalcis はトラキアやイタリアに植民して,エトルリア語経由でラテン語に西方型アルファベットを伝えた.一方,Miletus は黒海沿岸地方に植民し,古典ギリシア・アルファベットを確立し,さらにキリル文字などのスラヴ系アルファベットの発展を促した.

ローマン・アルファベットとギリシア・アルファベットの若干の違いは,もととなる変種の違いに起因するということがわかるだろう.大文字でいえば <C> と <Γ>,<D> と <Δ>, <L> と <Λ>,<X> と <Ξ>,<S> と <Σ> の字形の違い,また上述のように <Χ> の音価の [ks] と [kh] の違い,さらに <Η> の音価の [h] と [eː] の違いは,以上の事情による.

参考までに現代ギリシアの地図を掲げておこう.

以上,田中 (57--60) および Comrie et al. (183--87) を参照して執筆した. *

・ 田中 美輝夫 『英語アルファベット発達史 ―文字と音価―』 開文社,1970年.

・ Comrie, Bernard, Stephen Matthews, and Maria Polinsky, eds. The Atlas of Languages. Rev. ed. New York: Facts on File, 2003.

2014-05-07 Wed

■ #1836. viz. と「流石」 [latin][grapheme][grammatology][japanese][kanji][spelling_pronunciation_gap]

昨日の記事「#1835. viz.」 ([2014-05-06-1]) に引き続き,英語で namely と読み下す viz. について.今回は,文字論の立場から論じる.

英語において viz. と表記される語の構成要素である3文字(省略を表わす period を除く)は,当然ながらいずれもアルファベット文字(=表音文字)である.しかし,個々の文字で考えても,3文字が合わさった全体で考えても,まるで /neɪmli/ の発音を示唆するところがない.<viz.> はこの点において非表音的である.意味についても同様に,字面を個々に考えても全体で考えても,とうてい「すなわち」の意味は浮かび上がってこない.<viz.> はこの点において非表意的である.つまり,英語の <viz.> は,語源形であるラテン語 videlicet を想起するまれな場合を除き,通常は音も意味も示唆しない.

にもかかわらず,<viz.> は英語の副詞 namely と同等であるとして,英語使用者の意識のなかでは密接に結びついている.言い換えれば,<viz.> は,3文字全体としてむりやりに namely を表語している.<viz.> の綴字は,表音 (phonographic) でも表意 (ideographic) でもなく,表語 (logographic) の機能を果たしているのであり,記号論の用語を使えば,<viz.> が指し示しているものは,namely という記号 (signe) の能記 (signifiant) でも所記 (signifié) でもなく,namely という記号そのものである,ということになる.むりやりの結びつきであるから,英語使用者は,この <viz.> = namely の関係を暗記しなければならない.<viz.> のもつこの表語機能は,「#1042. 英語における音読みと訓読み」 ([2012-03-04-1]) で挙げた,<e.g.> (for example), <i.e.> (that is) にも見られる.

そこで,典型的に表語文字といわれる漢字を使いこなす日本語において,これと比較される類例があるだろうかと考えてみた.しかし,案外と見つからないものだ.漢字は確かに表語的ではあるが,同時に表意機能も果たすのが普通だし,形声文字の場合には表音機能も備わっている.英語の <viz.> の場合のように,発音も意味も示唆すらしないという徹底的な例は,なかなかない.

頭をひねってやっと思いついたのが,熟字訓として /さすが/ と読ませる <流石> という例だ.<流> も <石> も,さらにはそれを組み合わせた <流石> 全体も,なんら /さすが/ の発音を示唆するところがないし,「何といってもやはり」の意味を匂わせるところがない.<流石> は表音的でも表意的でもなく,副詞「さすが」をむりやりに表語しているのである.<viz.> と <流石> の唯一の差異は,前者の構成要素であるアルファベット文字が本質的に表音的であるのに対して,後者の構成要素である漢字は本質的に表語・表意的であるという点だろう.しかし,いずれの表記も全体としては結局のところ非表音的かつ非表意的であり,発現している機能はもっぱら表語機能である点では同じだ.

一見すると,「流石」 に代表される熟字訓は,純粋な表語機能(=非表音かつ非表意かつ表語)の好例を提供してくれそうだが,<私語> /ささやき/,<五月雨> /さみだれ/,<海苔> /のり/,<紅葉> /もみじ/ などでは,漢字の組み合わせが意味を匂わせてしまっており(しかも美しく詩的に),<viz.> = namely の純粋な表語機能には達していない.むしろ英語はアルファベットという表音文字体系をベースに置いている言語であるからこそ,<viz.> = namely のような例において,稀ではあるが純粋な表語機能を獲得し得たのかもしれない.文字論の観点からは,この逆説は興味深い.

なお,<流石> を /さすが/ と訓読するのは,以下の故事によるものとするのが通説である(『学研 日本語「語源」辞典』より).

中国,西晋の国の孫楚が「石に枕し,流れに漱ぐ」というべきところを,誤って「石に漱ぎ,流れに枕す」と言ってしまった.これを聞いた親友の王済が「流れは枕にできないし,石では口をすすげない」と言ってからかうと,孫楚は「流れを枕にするのは耳を洗うためであり,石に漱ぐというのは歯を磨くためである」と言って言い逃れたという.この故事を「さすがにうまいこじつけだ」と評し,「流石」の字が当てられたとする説がある.

上の議論では,一般の日本語話者がこの故事を知らない,あるいは普段は特に意識せずに,<流石> = /さすが/ の関係を了解していることを前提とした.故事を意識していれば,<流石> が非常に間接的ながらも何らかの表意機能をもっていると主張できるかもしれないからである.

文字の表語機能については,「#1332. 中英語と近代英語の綴字体系の本質的な差」 ([2012-12-19-1]),「#1386. 近代英語以降に確立してきた標準綴字体系の特徴」 ([2013-02-11-1]),「#1655. 耳で読むのか目で読むのか」 ([2013-11-07-1]),「#1829. 書き言葉テクストの3つの機能」 ([2014-04-30-1]) を参照.

2014-05-06 Tue

■ #1835. viz. [latin][loan_word][abbreviation][grapheme][grammatology][spelling_pronunciation_gap]

viz. は "namely" (すなわち)の意を表わす語で,/vɪz/ と読まれることもあるが,普通は namely /ˈneɪmli/ と発音される.もっぱら書き言葉に現れるので,ある種の省略符合と考えてよいだろう.もとの形は,英語でもまれにそのように発音されることはあるが, videlicet /vɪˈdɛləsɪt/ という語で,これはラテン語で「すなわち,換言すると」を意味する vidēlicet に由来する.このラテン語自体は,vidēre licet (it is permitted to see) という慣用表現のつづまったものである.OED によると,英語での初出は videlicet が1464年,省略形の viz. がa1540年である.

viz. の現代英語における用例をいくつか見てみよう.とりわけイギリス英語の形式張った書き言葉において,より明確に説明を施したり,具体例を列挙したりするのに用いられる.

・ four major colleges of surgery, viz. London, Glasgow, Edinburgh and Dublin

・ We both shared the same ambition, viz, to make a lot of money and to retire at 40.

・ The school offers two modules in Teaching English as a Foreign Language, viz. Principles and Methods of Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics.

関連して,ラテン語 scīre licet (it is permitted to know) のつづまった scilicet /ˈsɪləˌsɛt/ とその略形 scil. sc. も,英語でおよそ同じ意味に用いられる.

それにしても,videlicet が viz. と略されるのはなぜだろうか.中世ラテン語の写本では,<z> の文字は,-et, -(b)us, -m などの省略記号として一般に用いられていた.そこで,<z> = <et> と見立て,表記上 <vi(delic)z> とつづめたのである.古くは,<vidz.>, <vidzt>, <vz.> などとも表記された.ラテン語では et は "and" を意味するのでこの <z> の略記は多用され,古英語や中英語の写本でもそれをまねて and の語(あるいはその音価)に代わって頻繁に現れた.実際の <z> の字形は現在のものとは異なり,数字の <7> に似た <⁊ > という字形 (Unicode ⁊) で,この記号は Tironian et と呼ばれた.古代ローマのキケロの筆記者であった Marcus Tullius Tiro が考案した速記システム (Tironian notes, or notae Tironianae) で用いられた速記記号の1つである.これが,後に字形の類似から <z> に置き換えられるようになった.Irish や Scottish Gaelic では現在も Tironian et が使用されるが,英語では viz. にそのかすかな痕跡を残すのみである.

2014-05-03 Sat

■ #1832. ギリシア・アルファベットの文字の名称 (1) [greek][etruscan][latin][alphabet]

まず,Greek alphabet の24字の一覧を掲げよう.意外と正確には知らない英語での発音も要チェック.セム語名称と意味については,田中 (22) とカルヴェ (116--19) を参照した.

| 大文字 | 小文字 | 名称 | 英語名称 | 英語発音 | セム語名称 | 意味 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Α | α | アルファ | alpha | /ˈælfə/ | aleph | "ox" |

| 2 | Β | β | ベータ | beta | /ˈbeɪtə, ˈbiːtə/ | bet | "house" |

| 3 | Γ | γ | ガンマ | gamma | /ˈgæmə/ | gaml | "camel" |

| 4 | Δ | δ | デルタ | delta | /ˈdɛltə/ | delt | "door" |

| 5 | Ε | ε | エプシロン | epsilon | /ˈɛpsəˌlɑn/ | hé | ? |

| 6 | Ζ | ζ | ゼータ | zeta | /ˈzeɪtə, ˈziːtə/ | zai | "weapon"? |

| 7 | Η | η | エータ | eta | /ˈeɪtə, ˈiːtə/ | hét | "fence"? |

| 8 | Θ | θ | テータ | theta | /ˈθeɪtə, ˈθiːtə/ | tét | ? |

| 9 | Ι | ι | イオタ | iota | /aɪˈoʊtə/ | yod | "hand" |

| 10 | Κ | κ | カッパ | kappa | /ˈkæpə/ | kaf | "bend hand" |

| 11 | Λ | λ | ラムダ | lambda | /ˈlæmdə/ | lamd | "ox-goad"; "rod of teacher" |

| 12 | Μ | μ | ミュー | mu | /mjuː/ | mém | "water" |

| 13 | Ν | ν | ニュー | nu | /njuː/ | nun | "fish"; "serpent" |

| 14 | Ξ | ξ | クシー | xi | /(k)saɪ, (g)zaɪ/ | ||

| 15 | Ο | ο | オミクロン | omicron | /ˈɑməˌkrɑn/ | ‘ain | "eye" |

| 16 | Π | π | パイ | pi | /paɪ/ | ||

| 17 | Ρ | ρ | ロー | rho | /roʊ/ | rosh | "head" |

| 18 | Σ | σ, ς | シグマ | sigma | /ˈsɪgmə/ | ||

| 19 | Τ | τ | タウ | tau | /taʊ/ | tau | "mark" |

| 20 | Υ | υ | ユプシロン | upsilon | /ˈjuːpsəˌlɑn/ | wau | "peg", "hook" |

| 21 | Φ | φ | ファイ | phi | /faɪ/ | pé | "mouth" |

| 22 | Χ | χ | キー | chi | /kaɪ/ | ||

| 23 | Ψ | ψ | プシー | psi | /(p)saɪ/ | ||

| 24 | Ω | ω | オメガ | omega | /ˌoʊˈmeɪgə, ˌoʊˈmiːgə/ |

昨日の記事「#1831. アルファベットの子音文字の名称」 ([2014-05-02-1]) ほか文字の名称を扱った過去の記事(「#1830. Y の名称」 ([2014-05-01-1]) のリンク先を参照)では,文字の名称は,表音文字であるから当然のごとく対応する音価を含んでいるという前提で議論した.<a> は [eɪ] の音価を表わすのだからそのまま [eɪ] と呼ばれるし,<b> は [b] の音価を表わすのだから [b] を含んだ [biː] と呼ばれる.日本語の仮名も「あ」の文字名は「あ」であり,「い」の文字名は「い」である.文字のこのような呼び方,phonetic name といわれるこの方式は,ごく自然のことのように思われるが,ローマン・アルファベット (Roman alphabet) の祖先の上記ギリシア・アルファベット (Greek alphabet),さらに遡ったセム・アルファベット (Semitic alphabet) では,acrophonic name あるいは mnemonic name といわれる別の方式に従っていた.ギリシア語ではαは "alpha" と読み,βは "beta" と読んだが,これは "alpha" や "beta" という既存の単語を発音したものであり,確かに [a] と [b] は語頭音として含まれているが,英語における呼称とは方式が異なっている.

いま既存の単語を発音したものと述べたが,厳密にいえば "alpha" や "beta" はギリシア語の単語ではない."alpha", "beta", "gamma" 等々の単語はセム語において意味をもつ単語であり,ギリシア・アルファベットの発生以前のセム・アルファベットの段階での呼称だった.ギリシア人は,自らにとって無意味な語で呼称しながら,セム・アルファベットの文字一式を受け入れたのである.逆にいえば,ギリシア・アルファベットの文字がギリシア語で無意味な呼称を与えられている事実こそが,そのセム・アルファベット起源を物語っている.

acrophonic name 方式から phonetic name 方式への移行は,部分的にはギリシア語でも始まっていたが,本格的にはエトルリア語やラテン語がアルファベットをもつようになってからである.田中 (85) は,「ラテン・アルファベットにおける文字の新しい命名法は,古典ギリシアの方法に優る一大進歩」と評価している.

・ 田中 美輝夫 『英語アルファベット発達史 ―文字と音価―』 開文社,1970年.

・ ルイ=ジャン・カルヴェ 著,矢島 文夫 監訳,会津 洋・前島 和也 訳 『文字の世界史』 河出書房,1998年.

2014-05-02 Fri

■ #1831. アルファベットの子音文字の名称 [alphabet][consonant][latin][etruscan][phonetics][gvs]

過去の記事で,ローマン・アルファベットのいくつかの文字の名称について話題にした(昨日の記事「#1830. Y の名称」 ([2014-05-01-1]) と,その末尾にあるリンク先を参照).個々の文字について語るべきことはあるが,今回は子音字に関する一般論を中心に話を進めたい.以下,田中 (83--85) に依拠する.

現代英語のアルファベット26文字のうち,母音字 <a, e, i, o, u> を除いた21字が子音字である.子音字の名称はいくつかの例外を除き,その子音の音価に [iː] を後続させるグループ (Class I) と,[ɛ] を先行させるグループ (Class II) とに分けられる.

・ Class I: <b, c, d, g, p, t, v, z>

・ Class II:<f, l, m, n, s, x>

この分布を理解するには,歴史的な音価,とりわけ子音についてはラテン語(さらに文字史を遡ってエトルリア語)の音価を意識する必要がある.Class I の最初の6字はラテン語の破裂音 [b, k, d, g, p, t] に対応する.それぞれに後続する長母音 [iː] は,[eː] が大母音推移により,上げを経た結果である.一方,Class II の子音字はラテン語の継続音あるいは複合子音 [f, l, m, n, s, ks] に対応する.Class I の <v> と <z> は破裂音ではなく摩擦音だが,おそらく [ɛv], [ɛz] と呼んでしまうと,対応する無声子音字 <f> [ɛf], <s> [ɛs] と発音上区別がつきにくくなるという理由があったのではないか.

調音音声学的に Class I と II の分布を説明しようとすると,次のようになる(田中,p. 84).

子音文字について,継続宇音には e が先行し,そして破裂音には e が後続した現象は,Isaac Taylor がしたように,生理学的観点から眺めることもできよう.例えば,fe よりも ef という方がやさしく,eb よりも be という方がやさしい.それは継続音を発音する際には発音器官は完全には閉鎖されず,気息が漏れ,従って,子音が聞かれる前に母音が無意識に作られる.これにより,fe に達する前に実際上 ef が得られる.これに反して,破裂音の場合には閉鎖は完全であり,そして開放が行なわれる時,意識的な努力なくして母音が作られる.これにより,b に e を先行させることは明らかに努力を必要とするが,b は,唇が開かれる時,e に後続されることなくして発することはできない.言い換えれば,「最小努力の法則」 ('law of least effort') が,母音が継続音に先行し,そして破裂音に後続することを要求する.そして,この場合,最も容易な母音は中性的な e である.

興味深い説ではある.関連して,「#1141. なぜ mama と papa なのか? (2)」 ([2012-06-11-1]) も参照されたい.

<j> の名称 [ʤeɪ] については「#1828. j の文字と音価の対応について再訪」 ([2014-04-29-1]) で触れた通り,すぐ右どなりの <k> の名称 [keɪ] にならったものとされるが,[keɪ] 自体はなぜこの二重母音を伴っているのだろうか.これは,「#1824. <C> と <G> の分化」 ([2014-04-25-1]) で示唆したように,エトルリア語やラテン語において [k] 音の表記が後続する母音に応じて <c>, <k>, <qu> の間で変異していたことが影響している.[i, e] など前母音が後続するときには <c> が選ばれ,[a] の低母音が後続するときには <k> が選ばれ,[u, o] など後母音が後続するときには <q> が選ばれた.この傾向は英語を含めた後の諸言語にも多かれ少なかれ受け継がれており,英語の各文字の呼称にも間接的に反映されている.すなわち,<c> = [siː] はラテン語の <c> = [keː] から発展し,<k> = [keɪ] はラテン語の <k> = [kaː] から発展し,<q> = [kjuː] はラテン語の <q> = [kuː] から発展した.(前母音の前位置における [k] > [s] の音発達については,ラテン語から古フランス語を経て英語もその影響を被ったが,[kj] > [tj] > [ʧ] > [ʦ] > [s] の経路をたどった.)

最後に <r> の名称 [ɑː] (AmE [ɑr]) について.[r] は継続音として本来 Class II に属しており,ラテン語では少なくとも4世紀以降は [ɛr] のように読まれていた.中英語期に [er] > [ar] の変化が sterre > star, ferre > far など多くの語で生じたのに伴って,この文字の読みも [ar] へと変化した(関連して,「#179. person と parson」 ([2009-10-23-1]) と「#186. clerk と cleric」 ([2009-10-30-1]) を参照).その後,18世紀までに [ar] > [ær] > [æːr] > [ɑː] と規則変化して,現在に至る(田中,pp. 157--58).

・ 田中 美輝夫 『英語アルファベット発達史 ―文字と音価―』 開文社,1970年.

2014-04-29 Tue

■ #1828. j の文字と音価の対応について再訪 [phonetics][french][latin][italian][spelling][pronunciation][consonant][j][grapheme]

「#1650. 文字素としての j の独立」 ([2013-11-02-1]) の記事の最後の段落で,<j> (= <i>) = /ʤ/ の対応関係が生まれた背景について触れた.ラテン語から古フランス語への発展期に,有声硬口蓋接近音 [j] が有声後部歯茎破擦音 [ʤ] へ変化したという件だ.この音韻変化と「#1651. j と g」 ([2013-11-03-1]) の記事の内容に関連して,田中 (138--39) によくまとまった記述があったので,引用する(OED の記述もほぼ同じ内容).

6世紀少し前に,後期ラテン語において,上述の [j] 音はしばしば発声上圧縮され,前舌面および舌尖を [j] の位置よりさらに高めることによってその前に d 音を発生させ iūstus > d-iūstus, māior > mā-d-ior, [dj] を経て [ʤ] に assibilate された.一方 g の古い喉音は前母音の前で口蓋化して [ʤ] に変わっていたので,consonantal i と 'soft' g はロマンス諸語では同一の音価をもつようになった.

イタリア語では,consonantal i から発展した新しい音 [ʤ] は e, i の前には g,そして a, o, u の前には gi- によって書き変えられることになって,j の綴りは捨てられた.〔中略〕

しかし,フランス語では i 文字は発展した音価をもってそのまま保存され,従って consonantal i と 'soft' g は等値記号であり,その差異は語の起源によるだけである.

L OF It. ModE iūstus iuste giusto just iūdic-cem iuge giudice judge Iēsus Iesu Gesù Jesus māior maire maggiore major gesta geste gesto gest (jest)

Norman Conquest 後,consonantal i はその古代フランス語の音価 [ʤ] をもって英語に輸入された.フランス語ではその後 [ʤ] はその第一要素を失って [ʒ] に単純化されたが,英語は今日に至るまでフランス起源の語においてその原音を保存している.

加えて,アルファベット <J> の呼称 /ʤeɪ/ について,田中 (141) の記述を引用しておこう.

J は古くは jy [ʤai] と呼ばれて左どなりの同族文字 I [ai] と押韻し,そしてフランス名 ji と呼応した.この呼び名は今でもスコットランドその他において普通である.近代イギリス名(17世紀)ja あるいは jay [ʤei] は,その a [ei] を右どなりの k に負う (O. Jespersen, B. L. Ullman) .ドイツ名 jot [jɔt] は,16世紀に j が初めて i から分化した時,セム名 yōd から取られた.

・ 田中 美輝夫 『英語アルファベット発達史 ―文字と音価―』 開文社,1970年.

2014-04-27 Sun

■ #1826. ローマ字は母音の長短を直接示すことができない [grammatology][grapheme][latin][greek][alphabet][vowel][spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap]

現代英語の綴字と発音を巡る多くの問題の1つに,母音の長短が直接的に示されないという問題がある.英語も印欧語族の一員として,母音の長短,正確にいえば短母音か長母音・二重母音かという区別に敏感である.換言すれば,母音の単・複が音韻的に対立する.ところが,この音韻対立が綴字上に直接的に反映していない.例えば,bat vs bate や give vs five では同じ <a> や <i> を用いていながら,それぞれ前者では短母音を,後者では二重母音を表わしている.確かに,bat vs bate のように,次の音節の <e> によって,母音がいかに読まれるかを間接的に示すヒントは与えられている(「#1289. magic <e>」 ([2012-11-06-1]) を参照).しかし,母音字そのものを違えることで音の違いを示しているのではないという意味では,あくまで間接的な標示法にすぎない.give vs five では,そのヒントすら与えられていない.

母音字を組み合わせて長母音・二重母音を表わす方法は広く採られている.また,長母音補助記号として母音字の上に短音記号や長音記号を付し,ā や ă のようにする方法も,正書法としては採用されていないが,教育目的では使用されることがある.もとより文字体系というものは音韻対立を常にあますところなく標示するわけではない以上,英語の正書法において母音の長短が文字の上に直接的に標示されないということは,特に驚くべきことではないのかもしれない.

しかし,この状況が,英語にとどまらず,ローマン・アルファベットを採用しているあらゆる言語にみられるという点が注目に値する.母音の長短が,母音字そのものによって示されることがないのである.母音字を重ねて長母音を表わすことはあっても,長母音が短母音とまったく別の1つの記号によって表わされるという状況はない.この観点からすると,ギリシア・アルファベットのε vs η,ο vs ωの文字の対立は,目から鱗が落ちるような革新だった.

アルファベット史上,ギリシア人の果たした役割は(ときに過大に評価されるが)確かに革命的だった.「#423. アルファベットの歴史」 ([2010-06-24-1]) で述べたように,ギリシア人は,子音文字だったセム系アルファベットに初めて母音文字を導入することにより,音素と文字のほぼ完全な結合を実現した.音韻対立という言語にとってきわめて本質的かつ抽象的な特徴を取り出し,それに文字という具体的な形をあてがった.これが第1の革命だったとすれば,それに比べてずっと地味であり喧伝されることもないが,同じくらい本質を突いた第2の革命もあった.それは,母音の音価ではなく音量(長さ)をも文字に割り当てようとした発想,先述の ε vs η,ο vs ω の対立の創案のことだ.ギリシア人はフェニキア・アルファベットのなかでギリシア語にとって余剰だった子音文字5種を母音文字(α,ε,ι,ο,υ)へ転用し,さらに余っていたηをεの長母音版として採用し,次いでωなる文字をοの長母音版として新作したのだった(最後に作られたので,アルファベットの最後尾に加えられた).

ところが,歴史の偶然により,ローマン・アルファベットにつながる西ギリシア・アルファベットにおいては,上記の第2の革命は衝撃を与えなかった.西ギリシア・アルファベットでは,η(大文字Η)は元来それが表わした子音 [h] を表わすために用いられたので,そのままラテン語へも子音文字として持ち越された(後にラテン語やロマンス諸語で [h] が消失し,<h> の存在意義が形骸化したことは実に皮肉である).また,ωの創作のタイミングも,ラテン語へ影響を与えるには遅すぎた.かくして,第2の革命は,ローマ字にまったく衝撃を与えることがなかった.以上が,後にローマ字を採用した多数の言語が母音の長短を直接母音字によって区別する習慣をもたない理由である.

・ 田中 美輝夫 『英語アルファベット発達史 ―文字と音価―』 開文社,1970年.

2014-04-26 Sat

■ #1825. ローマ字 <F> の起源と発展 [grammatology][grapheme][latin][greek][alphabet][consonant][f][reduplication]

現代英語で <f> はほぼ常に /f/ に対応している(唯一の例外は of).この安定した関係は中英語にまで遡る.それ以前の古英語では <v> を欠いていたので,<f> は [f] とともに [v] にも対応していたが,中英語期にフランス語の綴字習慣に影響されて <v> が導入されることにより,<f> = /f/ の一意の関係が確立した.この経緯については,「#373. <u> と <v> の分化 (1)」 ([2010-05-05-1]),「#374. <u> と <v> の分化 (2)」 ([2010-05-06-1]),「#1222. フランス語が英語の音素に与えた小さな影響」 ([2012-08-31-1]),「#1230. over と offer は最小対ではない?」 ([2012-09-08-1]) を参照されたい.

英語史の範囲内で見る限り,<f> は特に問題となることはなさそうだが,この文字が無声唇歯摩擦音に対応するようになったのは,ラテン語における革新ゆえである.古代ギリシア語のアルファベットを知っている人は,<f> に対応する文字がないことに気づくだろう.しかし,古代ギリシア語でも西方言には <f> に相当する文字が残っていたし,東方言でも最初期の段階にはそれがあった.後に koiné となる東方言の1変種である Attic ではそれが失われていたので,現代に至るギリシア・アルファベットには <f> が含まれていないのである.

初期ギリシア語には存在した <F> は,Γを上下にずらして2つ並べたような字形だったために,"digamma" として知られていた.これは,セム・アルファベットの第6番目の文字(Yに似た字形で,"wāu" と呼ばれる)を引き継いだもので,ギリシア語では半母音 [w] に近い摩擦音の音価を表わした.しかし,東方言ではこの音は消失し,その文字も捨て去られた.半母音 [w] に対して純正の母音 [u] は同起源のΥの文字で表わされ,これが後にラテン語以降の諸言語で <U>, <V>, <W>, <Y> へと分化していった.つまり,ローマ字の <F>, <U>, <V>, <W>, <Y> はすべてセム・アルファベットの wāu に起源をもつことになる.

さて,ラテン語はギリシア語西方言でまだ生き残っていた <F> = [w] の関係を取り入れた.しかし,ラテン語では [w] は <V> で表わす慣習が確立したので,<F> は不要となった.不要となった <F> はギリシア語東方言のときのように廃用となる可能性もあったが,ラテン語はこの余った文字をギリシア語にはなく,ラテン語にはあった無声唇歯摩擦音 [f] を表わすのに転用することを決めた.当初は,直接の転用には抵抗があったらしく,<F> 単体ではなく <FH> のように2文字を合わせて [f] を標示することを試みた証拠がある.例えば,紀元前7世紀の最古のラテン語で記された「マニオス刻文」には,右から左へ "IOISAMVN DEKAHFEHF DEM SOINAM" (Manios made me for Numasios) とあり,第3語目に "FHEFHAKED" (古典ラテン語の fecit に相当する古い加重形 reduplication)が見える(田中,p. 71).しかし,後には <F> 単体で [f] を表わすことになった.この関係が,ラテン語およびそれ以降の諸言語で保持されている.

ある言語のアルファベットが別の言語に移植される際に,不要な文字が廃用となったり,転用されたり,新しい文字が足されるなど,種々の変更が加えられることは,アルファベット史を通じて何度となく繰り返されてきた.文字と音化の関係は,ときに惰性で保持されることはあっても,その都度変化するのも普通のことだったことがわかるだろう.

以上,田中 (pp. 125--28) を参照して執筆した.

・ 田中 美輝夫 『英語アルファベット発達史 ―文字と音価―』 開文社,1970年.

2014-04-25 Fri

■ #1824. <C> と <G> の分化 [grammatology][grapheme][latin][greek][alphabet][etruscan][rhotacism][consonant][c][g][q]

現代英語で典型的に <c> は /k/, /s/ に,<g> は /g/, /ʤ/ に対応する.それぞれ前者の発音は,古英語期に英語が Roman alphabet を受け入れたときのラテン語の音価に相当し,後者の発音は,その後の英語の歴史における発展を示す(<g> については,「#1651. j と g」 ([2013-11-03-1]) を参照).ラテン語から派生したロマンス諸語でも,種々の音変化の結果として,<c> や <g> が表わす音は,古典ラテン語のものとは異なっていることが多い.しかし,上で規範であるかのように参照したラテン語の <c> = /k/, <g> = /g/ という対応関係そのものも,ラテン語の歴史や前史における発展の結果,確立してきたものである.

ラテン語は,後にローマ字と呼ばれることになるアルファベットを,ギリシア語の西方方言からエトルリア語 (Etruscan) を介して受け取った.ギリシアとローマの両文明の仲介者であるエトルリア人とその言語は,「#423. アルファベットの歴史」 ([2010-06-24-1]) や「#1006. ルーン文字の変種」 ([2012-01-28-1]) でみたように,アルファベット史上に大きな役割を果たしたが,非印欧語であるエトルリア語について多くが知られているわけではない.しかし,エトルリア語の破裂音系列に有声・無声の音韻的対立がなかったことはわかっている.それにより,エトルリア語では,有声破裂音を表わすギリシア語のβとδは不要とされ廃用となった.しかし,γについては生き残り,これが軟口蓋破裂音 [k], [g] を表わす文字として用いられることとなった.

さて,エトルリア語から文字を受け取ったラテン語は,当初,γ = [k], [g] の関係を継続した.したがって,人名の省略形では,GAIUS に対して C. が,GNAEUS に対して CN. が当てられていた.しかし,紀元前300年頃に,この文字はとりわけ [k] に対応するようになり,純正に音素 /k/ を表わす文字として認識されるようになった.字体も rounded Γ と呼ばれる現代的な <C> へと近づいてゆき,<C> = /k/ の関係が確立すると,対応する有声音素 /g/ を表わすのに <C> に補助記号を伏した字形,後に <G> へ発展することになる字形が用いられるようになった.こうして紀元前300年頃に <C> と <G> が分化すると,後者はギリシア・アルファベットにおいてζが収っていた位置にはめ込まれた.ζは,ラテン語では後に <Z> として再採用されアルファベットの末尾に加えられることになったものの,[z] -> [r] の rhotacism を経て初期の段階で不要とされ廃用とされていたのである.

なお,ローマン・アルファベットでは無声軟口蓋破裂音を表わすのに <c>, <k>, <q> など複数の文字が対応しており,この点について英語を含めた諸言語は複雑な歴史を経験してきた.これは,英語の各文字の名称 /siː/, /keɪ/, /kjuː/ が暗示しているように,後続母音に応じた使い分けがあったことに起因する.エトルリア語では,前7世紀あるいはその後まで,CE, KA, QO という連鎖で用いられていた (cf. Greek kappa (Ka) vs koppa (Qo)) .現在にまで続く [k] を表わす文字の過剰は,ギリシア語やエトルリア語からの遺産を受け継いでいるがゆえである.

以上,田中 (pp. 76--79, 119) を参照して執筆した.

・ 田中 美輝夫 『英語アルファベット発達史 ―文字と音価―』 開文社,1970年.

2014-04-24 Thu

■ #1823. ローマ数字 [numeral][latin][greek][grammatology][alphabet][etruscan]

現代の英語や日本語でも,時々ローマ数字 (Roman numerals) が使われる機会がある.例えば,番号,年号,本のページ,時計の文字盤などに現役で使用されている.現代英語からの例をいくつか挙げよう.

・ It was built in the time of Henry V.

・ For details, see Introduction page ix.

・ Do question (vi) or question (vii), but not both.

・ a fine XVIII-century' English walnut chest of drawers

ローマ数字は,ほんの数種類の文字と組み合わせ方の単純な原理さえ覚えれば,大きな数も難なく表わすことができるという長所をもち,ヨーロッパで2000年以上にわたる伝統を誇ってきた.10進法のなかに5進法が混在しており,後者にはギリシアのアッティカ式の影響が見られる.IV = 4, IX = 9 など減法も利用したやや特異な記数法である.以下に凡例を掲げよう.

| 1 | I |

| 2 | II |

| 3 | III |

| 4 | IV |

| 5 | V |

| 6 | VI |

| 7 | VII |

| 8 | VIII |

| 9 | IX |

| 10 | X |

| 11 | XI |

| 12 | XII |

| 13 | XII |

| 14 | XIV |

| 19 | XIX |

| 20 | XX |

| 21 | XXI |

| 30 | XXX |

| 40 | XL |

| 45 | XLV |

| 50 | L |

| 60 | LX |

| 90 | XC |

| 100 | C |

| 500 | D |

| 1000 | M |

| 1998 | MCMXCVIII |

ヨーロッパでアラビア数字 (Arabic numerals) の使用が最初に確認されるのは976年のウィギラム写本においてだが,13--14世紀以降に普及するまでは,ローマ時代以来,ローマ数字 (Roman numerals) が一般的に使用されてきた(カルヴェ,pp. 210--11) .それ以降も,上述のような限られた文脈においては,現在まで命脈を保っている.

では,ローマ数字の起源について考えよう.I が1を表わすというのは直感的に理解できるとしても,V, X, C などその他の単位の文字はどのように選ばれたのだろうか.明確なことはわかっていないが,ドイツの歴史家 Theodor Mommsen (1817--1903) の説が有名である.それによると,V は手をかたどった象形文字であり,指の本数である5を表わすという.Vを上下に向かい合わせて重ねると,X (10) となる.L, C, M は,エトルリア語や初期ラテン語を書き表すのに不要とされた西ギリシア文字のΨ (khi; 東ギリシア文字では khi はΧによって表わされるので注意),Θ (theta),Φ (phi) をそれぞれ 50, 100, 1000 の数に割り当てたのが起源とされる.後に字形の類似により,Ψ(後に字形が┴のように変形する)が L と,Θが C(ラテン語 centum の影響もあり)と,Φが M(ラテン語 mille の影響もあり)と結びつけられた.L (50) の字形が C (100) の下半分の字形に似ているという意識,さらに D (500) の字形が M (1000) の右半分の字形に似ているという意識も関与していたのではないかと言われる(田中,p. 75).

・ 田中 美輝夫 『英語アルファベット発達史 ―文字と音価―』 開文社,1970年.

・ ルイ=ジャン・カルヴェ 著,矢島 文夫 監訳,会津 洋・前島 和也 訳 『文字の世界史』 河出書房,1998年.

2014-04-22 Tue

■ #1821. フランス語の復権と英語の復権 [french][latin][reestablishment_of_english][me][history][hfl]

中英語後期の,フランス語に対する英語の復権について,本ブログでは reestablishment_of_english の各記事で話題にしてきた.同じ頃,お隣のフランスでは,ラテン語に対するフランス語の復権が起こっていた.つまり,中世末期,イングランドとフランスの両国(のみならず実際にはヨーロッパ各国)で,相手にする言語こそ異なれ,大衆の言語 (vernacular) が台頭してきたのである.

中世後期のフランスで,フランス語がいかに市民権を得てきたか,行政・司法に用いられる言語という観点から概説しよう.中世フランスでは,行政・司法の言語としてラテン語が一般的であったことは間違いないが,13世紀中からフランス語の使用も始まっていた.特に Charles IV の治世 (1322--28) において行政・司法におけるフランス語の使用は,安定したものとはならなかったものの,進展した.その後14世紀末からは,フランス王国のアイデンティティと結びついた国語として,フランス語の存在感が確かに認められるようになってゆく.そして,ついに1539年8月15日,行政・司法におけるフランス語に,決定的なお墨付きが与えられることとなった.フランス語史上に名高いヴィレ・コトレの勅令 (l'ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts) である.「#653. 中英語におけるフランス借用語とラテン借用語の区別」 ([2011-02-09-1]) で触れたように,それまで法曹界はラテン語とフランス語の2言語制で回っていたが,フランソワ1世 (Francis I; 1494--1547) が行政・司法でのラテン語使用を廃止したのである.Perret (47) より,勅令の関係する箇所を引こう.

L'ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts (1539) Articles 110 et 111

«Et afain qu'il n'y ait cause de douter sur l'intelligence desdits arrests, nous voulons et ordonnons qu'ils soient faits et escrits si clairement, qu'il n'y ait ne puisse avoir aucune ambiguïté ou incertitude, ne lieu à demander interprétation.

Et pour ce que de telles choses sont souvent advenues sur l'intelligence des mots latins contenus esdits arrests, ensemble toutes autres procédures, [...] soient prononcez, enregistrez et delivrez aux parties en langaige maternel françois et non autrement.»

この勅令は,ラテン語を扱えない官吏の業務負担を減らすためという実際的な目的もあったが,フランス語をフランスの国語として制定するという意味合いがあった.その後の歴史において,フランスは他言語や非標準方言を退け,標準フランス語の普及と拡大に突き進んでゆくが,その最初の決定的な一撃が1539年に与えられたことになる.実際に,17世紀中にこの勅令の内容は拡大し,フランス革命後も堅持されたことはいうまでもない.

一方,イングランドにおける英語の復権は,「#131. 英語の復権」 ([2009-09-05-1]) や「#706. 14世紀,英語の復権は徐ろに」 ([2011-04-03-1]) で示したように,あくまで徐々に進んでいった.確かに,「#324. 議会と法廷で英語使用が公認された年」 ([2010-03-17-1]) である1362年のような,英語の復権を象徴する契機はあるにはあるが,ヴィレ・コトレの勅令のような1つの決定的な出来事に相当するものはない.

近代ではイングランド,フランスともに標準語を巡る問題,規範の議論が持ち上がったが,諸問題への対処法や言語政策は両国間で大きく異なっていた.その差異の起源は,すでに中世後期における土着語の復権の仕方そのものにあったように思われる.

・ Perret, Michèle. Introduction à l'histoire de la langue française. 3rd ed. Paris: Colin, 2008.

2014-03-22 Sat

■ #1790. フランスでも16世紀に頂点を迎えた語源かぶれの綴字 [etymological_respelling][spelling][latin][history_of_french][french][hfl]

語源かぶれの綴字 (etymological_respelling) について,「#116. 語源かぶれの綴り字 --- etymological respelling」 ([2009-08-21-1]) や「#192. etymological respelling (2)」 ([2009-11-05-1]) を始めとして多くの記事で取り上げてきた.中英語後期から近代英語初期にかけて,幾多の英単語の綴字が,主としてラテン語の由緒正しい綴字の影響を受けて,手直しを加えられてきた.ラテン語への心酔にもとづくこの傾向は,しばしば英国ルネサンスの16世紀と結びつけられることが多い.確かに例を調べると16世紀に頂点を迎える感はあるが,実際には中英語期から散発的に例が見られることは注意しておくべきである.また,同じ傾向はお隣のフランスで,おそらくイングランドよりも多少早く発現していたことも銘記しておきたい.このことについては,「#653. 中英語におけるフランス借用語とラテン借用語の区別」 ([2011-02-09-1]) の記事で少し触れた.

フランスでは,13世紀後半辺りに,ラテン語の語源的綴字からの干渉を受け始めたようだが,ブリュッケル (77) によれば,そのピークはやはり16世紀だという.

フランス語の単語をそれらの語源語またはそれらの自称語源語に近づけようというこうした関心は16世紀に頂点に達する.例えば,ある数のフランス語の単語の歴史において,r の前で a と e の選択に躊躇をする一時期があり,その時期は,実際には,15世紀から17世紀にまで拡がっていることが知られている.元の母音が復元されたのは古いフランス語の形にしたがってではなく,語源語であるラテン語にしたがってであることが確認される.armes 〔武器〕はその a を arma に,semon 〔説教〕はその e を(sermo の対格である)sermonem に負っている.さらには,中世と16世紀初頭において識られている唯一の形である erres 〔担保,保証〕はカルヴァンの作品においては arres に置き代えられ,のちになって arrhes がそれにとって代わることになるが,それらの相次ぐ二つの置き代えはまさに語源語である arrha に基づいてなされた.

フランス語史と英語史とで,ラテン語にもとづく語源かぶれの綴字が流行した時期が平行していることは,それほど驚くことではないかもしれない.しかし,英語史研究で語源かぶれの綴字が問題とされる場合には,当然ながら語源語となったラテン語の綴字のほうに強い関心が引き寄せられ,フランス語での平行的な現象には注意が向けられることがない.両言語の傾向のあいだにどの程度の直接・間接の関係があるのかは未調査だが,その答えがどのようなものであれ,広い観点からアプローチすることで,この英語史上の興味深い話題がますます興味深いものになる可能性があるのではないかと考えている.

・ シャルル・ブリュッケル 著,内海 利朗 訳 『語源学』 白水社〈文庫クセジュ〉,1997年.

2014-01-31 Fri

■ #1740. interpretor → interpreter [spelling][suffix][latin]

昨年末,標記の綴字の歴史的変遷に関する質問をいただいた.

寺澤芳雄 編『英語語源辞典(縮刷版)』(研究社,1999年,p.731)によりますと,interpreterという語において,語尾 -er が用いられるようになったのは16世紀からとされています.-er が優勢になった背景にはどんな事情があったのでしょうか.ご教示いただけたら幸いです.

それから少し調べてみたが,これは interpreter という1語の問題ではなく,動作主接尾辞 -er, -or を巡る,より一般的な問題のようであり,歴史的状況は複雑とみられる.本格的に回答するには少々腰を据えて調べなければならないと思われるので,今回は取り急ぎのものを示したい.

-or が -er へ置換されたもの,またその逆方向の置換は,英語史上しばしば見られる.起源についていえば,接尾辞 -er は英語本来のもの,接尾辞 -or はラテン語に由来するものであるが,中英語以来,両者は代用あるいは併用される例が現れる.現代英語においてラテン語要素 -or をもつ英単語の観点から歴史的状況を眺めると,Upward and Davidson (143--44) に次のような記述がある.

-OR, -OUR: The ending -OR was originally Lat, and many of the words with that ending in ModE are exact Lat forms: actor, doctor, professor, poerator, error, horror, senior, superior, etc.

・ Many other words with -OR may have it modelled on the Lat ending, but derive more directly from Fr forms with other endings which were often used in ME or EModE:

* Ambassador, author, emperor, governor, tailor were often written with -OUR in EModE.

* Bachelor, chancellor were often written with -ER in ME and EModE.

* Councillor was formerly not distinguished from counsellor. Both derive from Fr counseiller and were often written counseller in ME.

* Warrior (OFr werreor, ModFr guerrier) was in ME generally spelt -IOUR.

* Ancestor, anchor, traitor have ModFr equivalents ending in -RE (ancêtre, etc.) and were often spelt with -RE in ME.

* Mayor was adopted in EModE as a more Latinate form (compare major) in preference to ME mair(e) from Fr maire.

ラテン語形として -or をもつ語が英語に入ってくると,-or が保たれるものは確かに多いが,一方で英語やフランス語の慣例に従って -(i)our や -er と脱ラテン化する場合もあったことがわかる.

このような混乱まじりの慣例のなかから,ある程度の体系を示す慣例が次第にできあがってきた.「#1349. procrastination の生成過程」 ([2013-01-05-1]) や「#1383. ラテン単語を英語化する形態規則」 ([2013-02-08-1]) でも話題にしたように,ラテン語からの借用に慣れてくるにしたがって,ラテン単語を英語として取り入れる際の緩やかな「英語化規則」が適用されるようになってきたということだろう.その新しい慣例・規則の1つに,ラテン語で -ator をもつ動作主名詞を -er として受け入れる(あるいは受け入れなおす)というものがあったのではないか.ただし,慣例・規則とは言ったものの,実際にはある程度確立されるまでには時間もかかったわけであり,その間,共時的な変異と通時的な変化があったものと思われる.ラテン語の -ator は,まず -eur, -or, -our などのフランス語的な形態を経て,最終的には英語風の -er に収ったのではないか.結果としてみれば,ラテン語 -ator と英語 -er の対応が成立したことになる.これについて,Upward and Davidson (110) は次のように述べている.

The -ER may have developed from Lat -ATOR through MFr/ME -OUR to ModE -ER: e.g. Lat portator > OFr porteour > ME porteour > ME portour > ModE porter. Similar histories underlie controller, counter, recorder, turner, and partially also waiter (< OFr waitour).

そして,この引用の最後にもう1つ付け加えるべき例として,今回問題にしている LL interpretātor (explainer) が挙げられるのではないか.ここから,OF interpreteur や AF interpretour を経由して, ME interpretour や interpretor が行なわれ,ModE で interpreter へと至ったと考えられる.

以上を要約すれば,ラテン語の -ator に起源をもつ一群の語が,中英語期に -or その他の形態を経たのち,近代英語期に -er へ至る例が多かったということではないか.16世紀の interpretor > interpreter は,その事例の1つとみなすことができそうである.

この問題については,今後もいろいろ調べていく予定である.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2013-11-20 Wed

■ #1668. フランス語の影響による形容詞の後置修飾 (2) [adjective][syntax][french][latin][word_order][implicational_scale]

昨日の記事「#1667. フランス語の影響による形容詞の後置修飾 (1)」 ([2013-11-19-1]) の続編.英語史において,形容詞の後置修飾は古英語から見られた.後置修飾は中英語では決して稀ではなかったが,初期近代英語期の間に前置修飾が優勢となった (Rissanen 209) .Fischer (214) によると,Lightfoot (205--09) は,この歴史的経緯を踏まえて Greenberg 流の語順類型論に基づく含意尺度 (implicational scale) の観点から,形容詞後置 (Noun-Adjective) の語順の衰退は,SOV (Subject-Object-Verb) の語順の衰退と連動していると論じた.つまり,SVO が定着しつつあった中英語では同時に形容詞後置も発達していたのだというのである.(SVOの語順の発達については,「#132. 古英語から中英語への語順の発達過程」 ([2009-09-06-1]) を参照.)

しかし,中英語の形容詞の語順の記述研究をみる限り,Lightfoot の論を支える事実はない.例えば,Sir Gawain and the Green Knight では,8割が形容詞前置であり,後置を示す残りの2割のうち2/3の例が韻律により説明されるという.また,予想されるとおり,散文より韻文のほうが一般的に多く後置修飾を示す.さらに,後置修飾の形容詞は,フランス語の "learned adjectives" (Fischer 214) であることが多かった (ex. oure othere goodes temporels, the service dyvyne) .つまり,修飾される名詞とあわせて,これらの表現の多くはフランス語風の慣用表現だったと考えるのが妥当のようである.

中英語におけるこの傾向は,初期近代英語にも続く.Rissanen (208) は次のように述べている.

The order of the elements of the noun phrase is freer in the sixteenth century than in late Modern English. The adjective is placed after the nominal head more readily than today . . . . This is probably largely due to French or Latin influence: most noun + adjective combinations contain a borrowed adjective and the whole expression is often a term going back to French or Latin.

この時期からの例としては,a tonge vulgare and barbarous, the next heire male, life eternall などを挙げている.初期近代英語期の間にこの語順が衰退してきたという大きな流れはいくつかの研究 (Rissanen 209 を参照)で指摘されているが,テキストタイプや個々の著者別に詳細に調査してゆく必要があるかもしれない.昨日の記事でも触れたように,フランス語が問題の語順に与えた影響は,限られた範囲においてではあるが,現代英語でも生産的である.形容詞後置の問題は,英語史上,興味深いテーマとなるのではないか.

・ Fischer, Olga. "Syntax." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 2. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 207--408.

・ Rissanen, Matti. "Syntax." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 187--331.

・ Lightfoot, D. W. Principles of Diachronic Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 1979.

2013-10-21 Mon

■ #1638. フランス語とラテン語からの大量語彙借用のタイミングの共通点 [french][latin][renaissance][lexicology][loan_word][borrowing][reestablishment_of_english][language_shift]

フランス語借用の爆発期は「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1]) で見たように14世紀である.このタイミングについては,「#1205. 英語の復権期にフランス借用語が爆発したのはなぜか」 ([2012-08-14-1]) や「#1209. 1250年を境とするフランス借用語の区分」 ([2012-08-18-1]) の記事で話題にしたように,イングランドにおいて英語が復権してきた時期と重なる.それまでフランス語が担ってきた社会的な機能を英語が肩代わりすることになり,突如として大量の語彙が必要となったからとされる.フランス語を話していたイングランドの王侯貴族にとっては,英語への言語交替 (language shift) が起こっていた時期ともいえる(「#1540. 中英語期における言語交替」 ([2013-07-15-1]) を参照).

一方,ラテン語借用の爆発期は,「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]) や「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1]) で見たように,16世紀後半を中心とする時期である.このタイミングは,それまでラテン語が担ってきた社会的な機能,とりわけ高尚な書き物の言語にふさわしいとされてきた地位を,英語が徐々に肩代わりし始めた時期と重なる.ルネサンスによる新知識の爆発のために突如として大量の語彙が必要になり,英語は追いつけ,追い越せの目標であるラテン語からそのまま語彙を借用したのだった.このようにラテン語熱がいやましに高まったが,裏を返せば,そのときまでに人々の一般的なラテン語使用が相当落ち込んでいたことを示唆する.イングランド知識人の間に,ある意味でラテン語から英語への言語交替が起こっていたとも考えられる.

つまり,フランス語とラテン語からの大量語彙借用の最盛期は異なってはいるものの,共通項として「英語への言語交替」がくくりだせるように思える.ここでの「言語交替」は文字通りの母語の乗り換えではなく,それまで相手言語がもっていた社会言語学的な機能を,英語が肩代わりするようになったというほどの意味で用いている.この点を指摘した Fennell (148) の洞察の鋭さを評価したい.

As is often the case when use of a language ceases (as French did at the end of the Middle English period), the demise of Latin coincides with the borrowing of huge numbers of Latin words into English in order to fill perceived gaps in the language.

・ Fennell, Barbara A. A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow