2025-02-26 Wed

■ #5784. 連結辞 -o- は統語的グループではなく形態的複合を表わす [morphology][compound][greek][latin][word_formation][combining_form][morpheme][vowel][stem][syntax][phrase][connective]

昨日の記事「#5783. ギリシア語の連結辞 (connective) -o- とラテン語の連結辞 -i-」 ([2025-02-25-1]) で取り上げた -o- について,Kruisinga (II. 3, p. 7) が何気なさそうに鋭いことを指摘している.

1587. In literary English there is a formal way of distinguishing compounds from groups: the use of the Greek and Latin suffix -o to the first element:

Anglo-Indian, Anglo-Catholic, the Franco-German war, the Russo-Japanese war.

Of course, this use, though quite common, is of a learned character, clearly contrary to the natural structure of English words.

冒頭の "a formal way of distinguishing compounds from groups" がキモである.単語に相当する要素を2つ並べる場合,形態的に組み合わせると複合語 (compound) となり,統語的に組み合わせると句 (phrase) となる.別の言い方をすると,複合語は1語だが,句は2語である.言語学上の存在の仕方が異なるのだが,形態論的に何が異なるのかと問われると,回答するのに少し時間を要する.

発音してみれば,強勢位置が異なるという例はあるだろう.よく引かれる例でいえば bláckbòard (黒板)は複合語だが,black bóard (黒い板)は句である(cf. 「#4855. 複合語の認定基準 --- blackboard は複合語で black board は句」 ([2022-08-12-1])).綴字でもスペースを空けるか否かという区別がある.しかし,これらは韻律や正書法における区別であり,形態論上の区別というわけではない.複合語と句を分ける形態論上の方法は,意外とないのかもしれない.

逆にそのことに気付かせてくれたのが,上の引用だった.なるほど,連結辞 -o- が2要素間に挿入されていれば,その全体は句ではなく複合語であると判断できる.また,統語的な句を作るときに「つなぎ」として -o- を用いる例は存在しないだろう(少なくとも,思い浮かべられない).すると,連結辞 -o- はすぐれて形態論的な要素であり標識である,ということになる.

・ Kruisinga, E A Handbook of Present-Day English. 4 vols. Groningen, Noordhoff, 1909--11.

2025-02-25 Tue

■ #5783. ギリシア語の連結辞 -o- とラテン語の連結辞 -i- [morphology][compound][greek][latin][word_formation][combining_form][morpheme][vowel][stem][connective]

「#552. combining form」 ([2010-10-31-1]) にて,連結形の形態論上の問題点を挙げた.その (3) で「anthropology は anthrop- と -logy の combining form からなるが,間にはさまっている連結母音 -o- は明確にどちらに属するとはいえず,扱いが難しい」として取り上げた.この -o- というのは何だろうか.

『英語語源辞典』語源を探ると,ギリシア語において合成語(=複合語)の第1要素と第2要素を結ぶ「連結辞」 (connective) とある.さらに正確にいえば,ギリシア語の名詞・形容詞の語幹形成母音にさかのぼる.aristocracy, philosophy, technology にみられる通り,本来はギリシア語要素をつなげるケースに特有だったが,後にラテン語やその他の諸言語の要素を結ぶ場合にも利用されるようになった.

一般の複合語のほか,Anglo-French, Franco-Canadian, Graeco-Latin, Russo-Japanese のように同格関係を表わす複合語 (dvandva) にもよく用いられる.英語の語形成の歴史では,この種の複合語は比較的新しいものであり,小さなギリシア語連結辞 -o- の果たした役割は決して小さくない.これについては「#4449. ギリシア語の英語語形成へのインパクト」 ([2021-07-02-1]) を参照.

同様の連結辞として,ギリシア語ではなくラテン語に由来する -i- もある.英語に入ってきた複合語として omnivorous, pacific, uniform などがある.問題の -i- は最初の2単語については語幹の一部としてあった.しかし,最後の語についてはなかったので,純粋に連結辞として機能していたことになる.

いずれの連結形も古典語に由来し,フランス語を経て,英語にも入ってきた.現代英語における共時的な役割としては「つなぎの母音」ととらえておいてよいだろう.科学用語を中心として広く用いられるようになった偉大なチビ要素である.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

2025-02-22 Sat

■ #5780. 古典語に由来する連結形は日本語の被覆形に似ている [morphology][compound][latin][greek][japanese][word_formation][combining_form][terminology][derivation][affixation][morpheme]

昨日の記事「#5779. 連結形は語に対応する拘束形態素である」 ([2025-02-21-1]) で,連結形 (combining_form) に注目した.今回も引き続き注目していくが,『新英語学辞典』の解説を読んでみよう.

combining form 〔文〕(連結形) 複合語,時に派生語を造るときに用いられる拘束的な異形態をいう.英語の本来語では語基 (BASE) と区別がないが,ギリシア語・ラテン語に由来する形態の場合は連結形が独自に存在するのがふつうである.連結上の特徴から見ると前部連結形(例えば philo-)と後部連結形(例えば -sophy)とに分けることができる.接頭辞,接尾辞のような純粋な拘束形式と異なり,連結形は互いにそれら同士で結合したり,あるいは接辞をとることもできる.

おおよそ昨日の記述と重なるが,「英語の本来語では語基 (BASE) と区別がない」の指摘は比較言語学的にも対照言語学的にも興味深い.英語では,古い段階の古英語ですら,語 (word) の単位がかなり明確で,語とは別に語幹 (stem) や語根 (root) を切り出す共時的な動機づけは比較的弱い.

それに対して,ギリシア語やラテン語などの古典語では,英語に比べて屈折がよく残っており,これを反映して,形態的に独立した語とは異なる非独立的な連結形が存在する.

西洋古典語の連結形と関連して思い出されるのは,古代日本語の非独立形あるいは被覆形と呼ばれる形態だ.「#3390. 日本語の i-mutation というべき母音交替」 ([2018-08-08-1]) で導入した通り,例えば「かぜ」(風)と「かざ」(風見),「ふね」(船)と「ふな」(船乗り),「あめ」(雨)と「あま」(雨ごもり)のように,独立形と,複合語を作る際に用いられる非独立形の2系列があった.歴史的には音韻形態論的な変化の結果,2系列が生じたのだが,西洋古典語の連結形についても同じことがいえるかもしれない.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

2025-02-21 Fri

■ #5779. 連結形は語に対応する拘束形態素である [morphology][compound][latin][greek][word_formation][combining_form][terminology][derivation][affixation][morpheme]

接頭辞 (prefix) ぽい,あるいは接尾辞 (suffix) ぽい,それでいてどちらでもないという中途半端な位置づけの形態素 (morpheme) がある.連結形と訳される combining_form である.連結形についての説明や問題点は「#552. combining form」 ([2010-10-31-1]) で触れたとおりだが,『英語学要語辞典』での解説が分かりやすかったので,今回はその項目を引用したい.

combining form 〔言〕(連結形,造語形) 合成語 (COMPOUND) ときに派生語 (DERIVATIVE WORD) の形成に用いられる構成要素をいう.OED で aero- の定義にはじめて用いられたと考えられる.本来はギリシア語・ラテン語系に由来するものが多く,前部連結形(例 philo-)と後部連結形(例 -logy)の2種類がある.連結形は自由形式 (FREE FORM) をなす語 (WORD) の拘束異形態 (bound allomorph) ということができ,本来は独立語として用いられない.しかし,最近では anti (← anti-),graph (← -graph) のような例外的用法も増加している.また,連結形は接頭辞 (PREFIX)・接尾辞 (SUFFIX) に比べて意味が一層具象的であり,連結の関係も通例等位的である.ただし,最近では bio-degradable (= biologically ---) のような例外も認められる.さらに,接頭辞・接尾辞が通例直接互いに連結することがないのに対して,連結形は語や他の連結形のほか,接辞,特に接尾辞と連結することも可能である(例:-morphic (← -morph + -ic),heteroness (← hetero- + -ness)).

「連結形は語に対応する拘束形態素である」という捉え方は,とても分かりやすい.

なお,引用中にある OED への言及についてだが,combining form の項目に初例として以下が掲載されていた.

1884 Gr. ἀερο-, combining form of ἀήρ, ἀέρα

New English Dictionary (OED first edition) at Aero-

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編) 『英語学要語辞典』 研究社,2002年.

2025-02-20 Thu

■ #5778. connection か connexion か? [x][webster][latin][french][spelling][orthography][ame_bre][voicy][heldio]

5日ほど前に Voicy heldio にて,リスナー lacolaco さんの「英語語源辞典通読ノート」の最新回に基づいて「#1357. 接頭辞 con- の単語はまだ続く --- lacolaco さんの「英語語源辞典通読ノート」最新回より」と題する音声配信をお届けした.

そこで話題の1つとして,「コネクション」に対応する英単語の綴字が connection と connexion の間で揺れを示す件が触れられた.前者の綴字が一般的だがイギリス式では後者の綴字も見られるという.deflection, inflection, reflection についても同様に,メジャーな <-ction> に対してマイナーな <-xion> も辞書に登録されている.一方,complexion については,むしろこちらの綴字のほうが一般的で complection は稀である.

上記の heldio の配信後,この問題に関心を抱かれたリスナーのり~みんさんが,「-ction v.s. -xion」と題して Google Ngram での調査と合わせて記事を書かれている.

私もこの問題が気になって,少し調べてみた.というのも,私自身の研究テーマが英語の屈折 (inflection) の歴史にあり,先行研究の文献内で inflexion の綴字をよく目にしてきたからだ.

Upward and Davidson (167--68) によれば,英語では本来的には <-xion> も普通に見られたが,アメリカの辞書編纂家かつ綴字改革者の Noah Webster (1758--1843) が <-ction> のほうを推奨したのだという.19世紀から現代にかけての <-ction> の一般化に,Webster の影響があったらしい.

-XION and -CTION

Complexion, crucifixion, fluxion are standard ModE forms, and connexion, deflexion, inflexion exist as alternatives to connection, etc.

・ Complexion derives from the past participle plexum from the Lat verb plectere; although ME and EModE used such alternatives as complection, complection, ModE is firm on the x-spelling.

・ Crucifixion derives from the participle fixum of figere 'to fix'; the form crucifixion has been consistently used in the Christian tradition, and *crucifiction is not attested.

・ Fluxion is similarly determined by the Lat participle fluxum; the verb fluere offers no -CT- alternative.

・ Uncertainty has arisen in the case of connexion, deflexion, inflexion because, despite the Lat participles nexum, flexum with x, the corresponding infinitives, nectere, flectere have given rise to the Eng verbs connect, deflect, inflect.

・ In his American Dictionary of the English Language (1828), the American lexicographer Noah Webster . . . recommended the -CT- forms, which (despite ModFr connexion, deflexion, inflexion are today found much more frequently.

単純化していえば <-xion> はラテン語の過去分詞に基づき,かつそれを採用したフランス語的な綴字であり,<-ction> はラテン語の不定詞に基づき,それを推奨したアメリカ英語的な綴字ということになる.crucifixion が <-xion> としか綴られないのは,十字架の表象たる <X> と関係があるのだろうか,謎である.

今回の問題と関連して「#2280. <x> の話」 ([2015-07-25-1]) も参照.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2025-01-27 Mon

■ #5754. divers vs diverse [variant][pronunciation][latin][french][doublet][stress][spelling][adjective][polysemy][pronoun][doublet]

米国ではトランプ2.0が発足し,世界も予測不能のステージに入ってきている.この新政権では,DEI (= diversity, equity, and inclusion) の理念からの離脱が図られているとされる.この1つめの diversity は「多様性;相違」を意味するキーワードであり,英語にはラテン語からフランス語を経て14世紀半ばに借用されてきた.

この名詞の基体はラテン語の形容詞 dīversum であり,これ自体は動詞 dīvertere (わきへそらす,転換する)に遡る.それて転じた結果,「別種の;多様な;数個の」へ展開したことになる.

ところで,現代英語辞書には divers /ˈdaɪvəz/ と diverse /daɪˈvəːs/ とが別々に立項されている.綴字上は語尾に <e> があるかないかの違いがあり,発音上は強勢の落ちる音節および語末子音の有声・無声の相違がある.意味・語法としては,前者は古風・文学的な響きをもって「別種の;数個の」で用いられ,後者は主に「多様な」の語義で通用される.もともとは両者は互いに異形にすぎず,中英語期以降いずれの語義にも用いられてきたが,1700年頃に語形・意味において分化してきた.

divers /ˈdaɪvəz/ は「数個;数人」を意味する名詞・代名詞としても用いられるようになったためか,その語末子音は,名詞複数形の -s を反映するかのように /z/ へと転じた.また,diverse /daɪˈvəːs/ の発音と綴字は,ラテン語由来の adverse, inverse などと関連づけられて定着したものと思われる.

OED でも両語は別々に立項されているが,Diverse, Adj. & Adv. の項にて両語の形態と発音の歴史が詳細に解説されている.

Form and pronunciation history

The stress was originally on the second syllable, but was at an early date shifted to the first, although both pronunciations long coexisted, especially in verse. In early modern English divers (with stress on the first syllable) is the dominant form (overwhelmingly so in the 17th cent.), especially in the very common sense 'several, sundry, various' (see divers adj.) in which the word always occurs with a plural noun (the final -s coming to be pronounced /z/ after the plural ending -s, making the word homophonous with the plural of diver n.).

By the 18th cent. the senses of the word had come to be distinguished in form, with divers typically used to express the notions of variety and (especially) indefinite number (see divers adj. & n.) and diverse (probably by more immediate association with Latin diversus) the notion of difference (as in senses A.1 and A.3); thus Johnson (1755), Sheridan (1780), and Walker (1791), all of whom have two parallel entries. Both forms were typically stressed on the first syllable, and differed only in the pronunciation of the final consonant (respectively /z/ and /s/ ). The same formal and semantic distinction is reflected in 19th-cent. dictionaries, including Smart (1836), Worcester (1846), Knowles (1851), Stormonth (1877), Cent. Dict. (1889), and New English Dictionary (OED first edition) (1897). The latter notes at divers adj. (in sense 'various, sundry, several') that it is 'now somewhat archaic, but well known in legal and scriptural phraseology'; in this form the word is now chiefly archaic and used mainly in literary or legal contexts.

In the second half of the 19th cent. (as divers adj. was gradually becoming more restricted in use), the dictionaries begin to note an alternative pronunciation for diverse adj. with stress on the second syllable. This pronunciation probably continues the original one that had never entirely disappeared for this form, as is shown by examples from verse (compare e.g. quots. a1618, 1837 at sense A.1a, 1754 at sense A.3a). Knowles (1851) is one of the first dictionaries to note this pronunciation of diverse adj. (which, interestingly, he gives as the sole pronunciation); more commonly the two alternatives are given, as e.g. Craig (1882), who puts the pronunciation with initial stress first, and Stormonth (1877), Cent. Dict. (1889), New English Dictionary (OED first edition) (1897), who give priority to the pronunciation with stress on the second syllable; this has since become by far the more common pronunciation of the word.

2025-01-10 Fri

■ #5737. 語源,etymology, veriloquium [etymology][terminology][greek][latin][oe][aelfric]

下宮忠雄(著)『歴史比較言語学入門』(開拓社,1999年)の第9章は「語源学」と題されている.『スタンダード英語語源辞典』の編者の1人でもあるし,思い入れの強い章かと想像される.下宮 (131) は第9章の冒頭でこう書いている.

言語学概論の1年間の授業が終わったあとで,何が印象に残っているか,何が面白かったかを試験問題の最後に問うと,語源と意味論という返事が圧倒的に多い.言語の研究は古代ギリシアに始まるが,そこでは,文法 (grammar) と語源 (etymology) が言語研究の2つの柱だった.

単語は一つ一つが歴史を持っている.語源 (etymology) は単語の本来の意味(これをギリシア語では etymon という)を探り,その歴史を記述する.したがって,意味論とも大いに関係をもっている.Cicero (キケロー)はギリシア語の etymologia を vēriloquium (vērum 「真実」,loquium 「語ること,ことば」)とラテン語に訳したが,修辞学者 Quintilianus [クウィンティリアーヌス]が etymologia にもどし,これが西欧諸国に伝わって今日にいたっている.grammar も etymology も2千年以上も前のギリシア人が創造した用語である.

「語源」を意味する語が,西洋語の歴史において変遷してきたというのは知らなかった.ギリシア語由来の etymology の響きは高尚で好きだが,キケローのラテン語 vēriloquium も味わいがある.いずれも英語本来語でいえば true word ほどである.そこに日本語あるいは漢語の「語源」に含まれる「みなもと」の意味要素が(少なくとも明示的には)含まれていない点がおもしろい.

ちなみに,ギリシア語由来ながらもラテン語に取り込まれていた ethymologia の単語は,古英語でも術語として受容されていたようで,OED によると Ælfric, Grammar (St. John's Oxford MS.) 293 に文証される.

Sum þæra [sc. divisions of the art of grammar] hatte ETHIMOLOGIA, þæ is namena ordfruma and gescead, hwi hi swa gehatene sind.

この時点ではあくまでラテン単語としての受容にすぎなかったとはいえ,英語文化において etymology は相当に長い歴史をもっているといえる.

(以下,後記:2025/01/12(Sun))

・ heltalk 「ラテン語で「語源」を意味する veriloquium もカッコいいですね」 (2025/01/10)

・ heldio 「#1322. word-lore 「語誌」っていいですよね」 (2025/01/11)

・ 下宮 忠雄 『歴史比較言語学入門』 開拓社,1999年.

・ 下宮 忠雄・金子 貞雄・家村 睦夫(編) 『スタンダード英語語源辞典』 大修館,1989年.

2025-01-07 Tue

■ #5734. B&C の第60節 "Latin Influence of the Second Period" の第3段落を Taku さん(ほかヘルメイト数名)と対談精読しました [bchel][latin][borrowing][christianity][link][voicy][heldio][anglo-saxon][st_augustine][history][helmate]

今朝の Voicy heldio で「#1318. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (60-3) Latin Influence of the Second Period --- Taku さん対談精読実況中継」を配信しました.これは昨年末の12月26日(木)の夕方に生配信した対談精読実況中継のアーカイヴ版です.

今回の対談回はヘルメイトさんたちとの忘年会も兼ねていたので,賑やかです.今回は,前回に引き続き Taku さんこと金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)に司会をお願いしました.さらに,専門家として小河舜さん(上智大学)に加わっていただきました.ヘルメイトとしては,Grace さん,ykagata さん, lacolaco さん, Lilimi さん,ぷりっつさんが参加されました.8名でのたいへん充実した精読会となりました.

今回の精読箇所は第60節 "Latin Influence of the Second Period: The Christianizing of Britain" の第3段落です.さほど長くない1節でしたが,55分ほどかけて皆で「超」精読しました.文字通りに「豊かな」時間となりました.特に gradual という基本語の意味をめぐって,私はたいへん大きな学びを得ることができました.お時間のあるときに,ぜひ精読対象のテキストとなる1段落分の文章(Baugh and Cable, pp. 79--80 より以下に掲載)を追いつつ,超精読にお付き合いください.

The conversion of the rest of England was a gradual process. In 635 Aidan, a monk from the Scottish monastery of Iona, independently undertook the reconversion of Northumbria at the invitation of King Oswald. Northumbria had been Christianized earlier by Paulinus but had reverted to paganism after the defeat of King Edwin by the Welsh and the Mercians in 632. Aidan was a man of great sympathy and tact. With a small band of followers he journeyed from town to town, and wherever he preached he drew crowds to hear him. Within twenty years, he had made all Northumbria Christian. There were periods of reversion to paganism and some clashes between the Celtic and the Roman leaders over doctrine and authority, but England was slowly won over to the faith. It is significant that the Christian missionaries were allowed considerable freedom in their labors. There is not a single instance recorded in which any of them suffered *martyrdom* in the cause they espoused. Within a hundred years of the landing of Augustine in Kent, all England was Christian.

本節と関連の深い hellog 記事や heldio コンテンツは,「#5686. B&C の第60節 "Latin Influence of the Second Period" の第1段落を対談精読実況生中継しました」 ([2024-11-20-1]) に挙げたリンク集よりご参照ください.B&C の対談精読実況中継は,今後も時折実施していきたいと思います.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2024-12-27 Fri

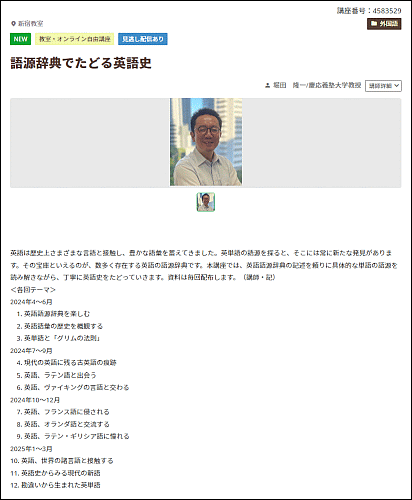

■ #5723. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第9回「英語,ラテン・ギリシア語に憧れる」をマインドマップ化してみました [asacul][latin][greek][mindmap][notice][kdee][etymology][hel_education][lexicology][vocabulary][heldio][link]

12月21日に,今年度の朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室でのシリーズ講座の第9回が開講されました.今回は「英語,ラテン・ギリシア語に憧れる」と題して,古典語への傾倒が顕著だった16--17世紀の初期近代英語期に注目しました.この時期,知識が増大し学問も発展したために新しい語彙が大量に必要となり,そのニーズに応えるべくラテン語やギリシア語の単語や要素が持ち出されたのでした.結果として,古典語に基づく借用語や新語がおびただしく導入され,英語語彙は空前の拡張を遂げることになります.

今回も,対面およびオンラインで多くの方々にご参加いただきました.ありがとうございます.講座の内容を,markmap というウェブツールによりマインドマップ化して整理してみました(画像としてはこちらからどうぞ).受講された方は復習用に,そうでない方は講座内容を垣間見る機会としてご活用ください.

今回のシリーズ第9回については hellog と heldio の過去回でも取り上げていますので,ご参照ください.

・ hellog 「#5710. 12月21日(土)の朝カルのシリーズ講座第9回「英語,ラテン・ギリシア語に憧れる」のご案内」 ([2024-12-14-1])

・ heldio 「#1297. 12月21日(土)の朝カル講座「英語,ラテン・ギリシア語に憧れる」に向けて」 (2024/12/17)

また,シリーズ過去回のマインドマップについては,以下もご参照ください.

・ 「#5625. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第1回「英語語源辞典を楽しむ」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-09-20-1])

・ 「#5629. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第2回「英語語彙の歴史を概観する」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-09-24-1])

・ 「#5631. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第3回「英単語と「グリムの法則」」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-09-26-1])

・ 「#5639. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第4回「現代の英語に残る古英語の痕跡」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-10-04-1])

・ 「#5646. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第5回「英語,ラテン語と出会う」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-10-11-1])

・ 「#5650. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第6回「英語,ヴァイキングの言語と交わる」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-10-15-1])

・ 「#5669. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第7回「英語,フランス語に侵される」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-11-03-1])

・ 「#5704. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第8回「英語,オランダ語と交流する」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-12-08-1])

次回の朝カル講座は.冬のクールの始まりとして,新年の1月25日(土)17:30--19:00に開講予定です.第10回「英語,世界の諸言語と接触する」と題して,主に後期近代英語期以降の世界中の諸言語からの借用語にフォーカスします.ご関心のある方は,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室の「語源辞典でたどる英語史」のページよりお申し込みください.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

2024-12-26 Thu

■ #5722. Shakespeare は1591--1611年の間にラテン語由来の単語を600語取り込んだ [renaissance][shakespeare][emode][latin][greek][borrowing][loan_word][neologism][statistics][neo-latin][scientific_name][scientific_english][word_formation]

16--17世紀の初期近代英語期は,大部分が英国ルネサンスの最盛期に当たり,古典語(ラテン語とギリシア語)が尊ばれ,そこから大量の単語が英語語彙に取り込まれた時期である.同時代の代表的な文人が Shakespeare なのだが,Durkin によればこの劇作家のみに注目したとしても,短期間に相当数のラテン語由来の新語 ("latinate neologisms") が英語に流入したことが確認されるという.

The peak period of the Literary Renaissance was C.1590--1600. The Primary author was Shakespeare who, between 1591 and 1611, introduced no fewer than six hundred latinate neologisms, fifty-three of which occur in Hamlet alone. Many of these became everyday words, e.g. addiction, assassination, compulsive, domineering, obscene, sanctimonious, traditional. (226--27)

この点で Shakespeare は同時代的に著しい造語力を体現しているといえるが,さらに重要なのは,その後の新古典主義新語ブームに前例を与えたという功績なのではないか.Shakespeare に代表されるルネサンス期に火のついた古典語からの語彙借用の慣習は,続く時代にも勢いが緩まるどころか,むしろ拡張しつつ受け継がれていったからである.Durkin はこう続けている.

After the Renaissance, a vast amount of technical and scientific vocabulary flooded into English from both Greek and Latin, hence words like carnivorous, clitoris, formula, hymen, nucleus. In the next century, Linnaeus [1707--78] introduced numerous biological terms, like chrysanthemums and rhododendron. The Scientific period, which peaked C.1830, featured many Neolatin terms like am(o)eba, bacterium, flagellum. Finally, the modern technical/technological period featured words like floccilation. (227)

これは Shakespeare が英語語彙史上に果たした役割の1つとみてよいだろう.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2024-12-23 Mon

■ #5719. ギリシア語が英語に影響を与えた3つの型 [greek][latin][borrowing][loan_word][lexicology][word_formation][derivation][compounding][oe][prestige][combining_form][morphology][scientific_name][scientific_english][link]

ギリシア語が英語に与えた語彙的影響は,ラテン語やフランス語のそれに比べると見劣りするように思われるかもしれないが,実際にはきわめて大きい.語彙そのものというより,むしろ語形成 (word_formation) に与えた影響が大きい,といったほうが適切かもしれない.とりわけ連結形 (combining_form) を用いた科学系の複合語の形成は,ギリシア語の偉大な貢献である.

Durkin (231) は,英語史におけるギリシア語の影響について,広い視野から次のように述べている.

Between C5 and C8-9, the Greek liberal arts education was revived, first by the Ostrogoths, later by the Carolingians, and Greek gained special prestige. Writers liberally sprinkled their woks with Greek words, many of which found their way into other languages of Europe, including Old English. Particularly noteworthy are the glossarial poems from Canterbury with words like apoplexis, liturgia, spasmus. Since then, Greek medical doctrine and the terms associated with it became the major part of English medical lexis . . . . More general scientific vocabulary from Greek has mushroomed since C18 . . . .

. . . .

Greek influence on English, then, is restricted to the lexicon, (limited) derivation, and compounding. Words entered English initially through Roman borrowings, then through direct borrowing from Ancient Greek writers, more recently through word formation (combining roots and affixes) in English.

ギリシア語の英語への影響には,3パターンあるいは3段階があったとまとめてよいだろう.

(1) ラテン語を経由して(中世から)

(2) 直接ギリシア語から(近代以降)

(3) ギリシア語「要素」を用いた英語内での造語(近代以降,特に18世紀以降;「科学用語新古典主義的複合語」 (neo-classical compounds) あるいは「英製希語」と呼んでもよいか)

いずれのパターンについても,ギリシア語に付された威信 (prestige) を反映して学術用語の造語が圧倒的である.関連する話題として,以下の hellog 記事も参照.

・ 「#516. 直接のギリシア語借用は15世紀から」 ([2010-09-25-1])

・ 「#552. combining form」 ([2010-10-31-1])

・ 「#616. 近代英語期の科学語彙の爆発」 ([2011-01-03-1])

・ 「#617. 近代英語期以前の専門5分野の語彙の通時分布」 ([2011-01-04-1])

・ 「#1694. 科学語彙においてギリシア語要素が繁栄した理由」 ([2013-12-16-1])

・ 「#3014. 英語史におけるギリシア語の真の存在感は19世紀から」 ([2017-07-28-1])

・ 「#3013. 19世紀に非難された新古典主義的複合語」 ([2017-07-27-1])

・ 「#3166. 英製希羅語としての科学用語」 ([2017-12-27-1])

・ 「#3179. 「新古典主義的複合語」か「英製羅語」か」 ([2018-01-09-1])

・ 「#3368. 「ラテン語系」語彙借用の時代と経路」 ([2018-07-17-1])

・ 「#4191. 科学用語の意味の諸言語への伝播について」 ([2020-10-17-1])

・ 「#4449. ギリシア語の英語語形成へのインパクト」 ([2021-07-02-1])

・ 「#5718. ギリシア語由来の主な接尾辞,接頭辞,連結形」 ([2024-12-22-1])

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2024-12-22 Sun

■ #5718. ギリシア語由来の主な接尾辞,接頭辞,連結形 [greek][suffix][prefix][lexicology][word_formation][combining_form][morphology][latin][french][loan_word][borrowing]

Durkin (216--19) にかけて,英語に入ったギリシア語由来の要素が列挙されている.接尾辞 (suffix),接頭辞 (prefix),連結形 (combining_form) に分けて,主たるものを列挙しよう.ラテン語やフランス語からの借用語のなかに混じっている要素もあり,究極的にはギリシア語由来であることが気づかれていないものも含まれているのではないか.

[ 接尾辞 ]

-on (plural -a), -ter, -terion, -ma/-mat- (adj. -matic), the family of -ize/-ise (-ist/-ast, -ism, -asm), -ite, -ess, -oid, -isk, -(t)ic, -istic(al), -astic(al)

[ 接頭辞 ]

a(n)-, amph(i)-, an(a)-, anti-, ap(o)-, cat(a)-/kat(a)-, di(a)-, dys-, a(n)-, end(o)-, exo-, ep(i)-, hyper-, hyp(o)-, met(a)-, par(a)-, peri-, pro-, pros-, syn-/sys-

[ 連結形 ]

acro- "high; of the extremities", agath(o)- "good", all(o)- "other, alternate, distinct", arch- "chief; original", argyr(o)- "silver", aut(o)- "self(-induced); spontaneous", bary-/bar(o)- "heavy; low; internal", brachy- "short", brady- "slow", cac(o)- "bad", chlor(o)- "green; chlorine", chrys(o)- "gold; golden-yellow", cry(o)- "freezing; low-temperature", crypt(o)- "secret; concealed", cyan(o)- "blue", dipl(o)- "twofold, double", dolich(o)- "long", erythr(o)- "red", eu- "good, well", glauc(o)- "bluish-green, grey", gluc(o)- "glucose"/glyc(o)- "sugar; glycerol"/glycy- "sweet", gymn(o)- "naked, bare", heter(o)- "other, different", hol(o)- "whole, entire", homeo- "similar; equal", hom(o)- "same", leuc/k(o)- "white", macro- "(abnormally) large", mega- "huge; very large", megal(o)- "large; grandiose" and -megaly "abnormal enlargement", melan(o)- "black; dark-colored; pigmented", mes(o)- "middle", micr(o)- "(very) small", nano- "one thousand-millionth; extremely small", necr(o)- "dead; death", ne(o)- "new; modified; follower", olig(o)- "few; diminished; retardation", orth(o)- "upright; straight; correct", oxy- "sharp, pointed; keen", pachy- "thick", pan(to)- "all", picr(o)- "bitter", platy- "broad, flat", poikil(o)- "variegated; variable", poly- "much, many", proto- "first", pseud(o)- "false", scler(o)- "hard", soph(o)- and -sophy "skilled; wise", tachy- "swift", tel(e)- "(operating) at a distance", tele(o)- "complete; completely developed", therm(o)- "warm, hot", trachy- "rough"

英語ボキャビルのおともにどうぞ.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2024-12-14 Sat

■ #5710. 12月21日(土)の朝カルのシリーズ講座第9回「英語,ラテン・ギリシア語に憧れる」のご案内 [asacul][notice][kdee][etymology][hel_education][helkatsu][link][lexicology][vocabulary][latin][greek][renaissance][emode][voicy][heldio]

・ 日時:12月21日(土) 17:30--19:00

・ 場所:朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室

・ 形式:対面・オンラインのハイブリッド形式(1週間の見逃し配信あり)

・ お申し込み:朝日カルチャーセンターウェブサイトより

今年度の朝カルシリーズ講座「語源辞典でたどる英語史」が,月に一度のペースで順調に進んでいます.主に『英語語源辞典』(研究社)を参照しながら,英語語彙史をたどっていくシリーズです.

1週間後に開講される第9回では主に初期近代英語期におけるラテン語およびギリシア語の語彙的影響を評価します.16--17世紀の初期近代英語期は英国ルネサンスの時代に当たり,古典語への傾倒が顕著でした.知識が増大し学問も発展したために新しい語彙が大量に必要となり,そのニーズに応えるべくラテン語やギリシア語の単語や要素が持ち出されたのです.結果として,古典語に基づく借用語や新語がおびただしく導入され,英語語彙は空前の拡張を遂げることになります.

今回の講座では,古典語からの借用語に主に注目し,この時期の語彙拡大の悲喜劇を観察してみたいと思います.ぜひ皆さんもこの時代にもたらされたラテン・ギリシア語系のオモシロ単語を探してみてください.

本シリーズ講座の各回は独立していますので,過去回への参加・不参加にかかわらず,今回からご参加いただくこともできます.過去8回分については,各々概要をマインドマップにまとめていますので,以下の記事をご覧ください.

・ 「#5625. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第1回「英語語源辞典を楽しむ」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-09-20-1])

・ 「#5629. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第2回「英語語彙の歴史を概観する」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-09-24-1])

・ 「#5631. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第3回「英単語と「グリムの法則」」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-09-26-1])

・ 「#5639. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第4回「現代の英語に残る古英語の痕跡」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-10-04-1])

・ 「#5646. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第5回「英語,ラテン語と出会う」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-10-11-1])

・ 「#5650. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第6回「英語,ヴァイキングの言語と交わる」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-10-15-1])

・ 「#5669. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第7回「英語,フランス語に侵される」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-11-03-1])

・ 「#5704. 朝カルシリーズ講座の第8回「英語,オランダ語と交流する」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2024-12-08-1])

本講座の詳細とお申し込みはこちらよりどうぞ.『英語語源辞典』(研究社)をお持ちの方は,ぜひ傍らに置きつつ受講いただければと存じます(関連資料を配付しますので,辞典がなくとも受講には問題ありません).

(以下,後記:2024/12/17(Tue))

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

2024-12-06 Fri

■ #5702. 古英語単語の意味変化 [oe][semantic_change][christianity][latin][metaphor][semantic_borrowing][contact]

いずれの言語においても,語彙の意味変化 (semantic_change) はきわめてありふれたタイプの言語変化であり,常に起こっている.このことは「#1955. 意味変化の一般的傾向と日常性」 ([2014-09-03-1]) でも論じた通りである.古英語の単語にも,多くの意味変化が起こっていたことだろう.

しかし,たくさんあったであろう古英語単語の意味変化を,文献学的に文証できるかどうかは別問題である.そもそも古英語の現存する資料は少ないため,ある単語の意味変化が古英語期中に起こったのかどうかを確かめるのに十分な情報が得られないことも多い.また,意味変化が確かに起こったと言えるためには,変化前と変化後の語義の各々の出典となるテキストが,時間的に前後していることを確言できなければならない.しかし,これにはテキスト年代や写本年代をめぐる諸問題がつきまとう.

このような事情で古英語期の単語の意味変化を論じるには困難が生じるのだが,それでもある程度言えることはある.アングロサクソン事典の "semantic change" の項目 (p. 415) より関連する箇所を引用する.

One area of vocabulary in which semantic change clearly took place during the Old English period is religious terminology. God 'God', heofon 'heaven', and helle 'hell', for example, necessarily adopted new meanings when they were applied to Christian rather than pagan concepts. Semantic change can also take the form of the development of a metaphorical meaning. In Old English this sometimes took place under the influence of Latin. Examples include tunge 'tongue', which was extended to mean 'language', possibly modelled on Latin lingua, and wit(e)ga 'wise man', used for 'prophet', perhaps influenced by Latin propheta. After the establishment of the Danelaw, OE terms also underwent semantic development under the influence of their Old Norse cognates. Modern English bloom 'flower' takes its form from either Old English bloma 'ingot of iron' or Old Norse blom 'flower', but its sense is clearly from Old Norse. In Old English, plog (ModE plough) was used for the measure of land which a yoke of oxen could plough in a day; its use with reference to an agricultural implement developed under the influence of Old Norse plogr. Similarly, Old English eorl 'man, warrior' (ModE earl) developed the sense 'chief, ruler of a shire' under the influence of Old Norse jarl.

ラテン語のキリスト教用語の影響による意味変化や古ノルド語の対応語の影響による意味変化が取り上げられているが,これは歴史言語学では意味借用 (semantic_borrowing) として言及されることの多いタイプのものである.他言語における当該の単語の意味が分かっており,かつ言語接触の時期などが特定できれば,このような意味変化の議論も可能になるということだ.歴史言語学や文献学の方法論上のトピックとしてもおもしろい.

・ Lapidge, Michael, John Blair, Simon Keynes, and Donald Scragg, eds. The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1999.

2024-12-02 Mon

■ #5698. royal we の起源と古英語・中英語 [greek][latin][royal_we][monarch][sociolinguistics][oe][me]

昨日の記事「#5697. royal we は「君主の we」ではなく「社会的不平等の複数形」?」 ([2024-12-01-1]) に引き続き「君主の we」 (royal_we) に注目する.術語としては "plural of majesty", "plural of inequality" なども用いられているが,いずれも1人称複数代名詞の同じ用法を指している.

Mustanoja (124) は,"plural of majesty" という用語を使いながら,ラテン語どころかギリシア語にまでさかのぼる用例の起源を示唆している.その上で,英語史における古い典型例として,中英語より「ヘンリー3世の宣言」での用例に言及していることに注目したい.

PLURAL OF MAJESTY. --- Another variety of the sociative plural (pluralis societatis) exists as the plural of majesty (pluralis majestatis), likewise characterised by the use of the pronoun of the first person plural for the first person singular. The plural of majesty originates in a living sovereign's habit of thinking of himself as an embodiment of the whole community. As the use of the plural becomes a mere convention, the original significance of this plurality tends to disappear. The plural of majesty is found in the imperial decrees of the later Roman Empire and in the letters of the early Roman bishops, but it can be traced to even earlier times, to Greek syntactical usage (cf. H. Zilliacus, Selbstgefühl und Servilität: Studien zum unregelmâssigen Numerusgebrauch im Griechischen, SSF-GHL XVIII, 3, Helsinki 1953). The plural of majesty is extensively used in medieval Latin. In OE it does not seem to be attested. OE royal charters, for example, have the singular (ic Offa þurh Cristes gyfe Myrcena kining; ic Æþelbald cincg, etc.). The plural of majesty begins to be used in ME. A typical ME example is the following quotation from the English proclamation of Henry III (18 Oct., 1258), a characteristic beginning of a royal charter: --- Henry, thurȝ Gode fultume king of Engleneloande, Lhoaverd on Yrloande, Duk on Normandi, on Aquitaine, and Eorl on Anjow, send igretinge to alle hise holde, ilærde ond ileawede, on Huntendoneschire: thæt witen ȝe alle þæt we willen and unnen þæt . . ..

引用中の "the English proclamation of Henry III (18 Oct., 1258)" (「ヘンリー3世の宣言」)での用例について,ナルホドと思いはする.しかし「#5696. royal we の古英語からの例?」 ([2024-11-30-1]) の最後の方で触れたように,この例ですら確実な royal we の用法かどうかは怪しいのである.この宣言の原文については「#2561. The Proclamation of Henry III」 ([2016-05-01-1]) を参照.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2024-11-24 Sun

■ #5690. B&C の第60節 "Latin Influence of the Second Period" の第2段落を Taku さんと対談精読しました [bchel][latin][borrowing][christianity][link][voicy][heldio][anglo-saxon][st_augustine][history][bede]

今朝の Voicy heldio で「#1274. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (60-2) Latin Influence of the Second Period --- Taku さん対談精読実況中継」を配信しました.これは4日前に配信した「#1270. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (60-1) Latin Influence of the Second Period --- 対談精読実況中継」の続編です(hellog でも同趣旨の記事 [2024-11-20-1] を公開しています).

「対談精読実況中継」なるものは,「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) の一環として,時々ゲストをお招きしつつお届けしているのですが,今回は前回に引き続き MC として金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)にご出演いただきました.Voicy のコラボ収録(オンライン)機能を初めて利用してみたのですが,音声も十分にクリアです.

今回の精読箇所は第60節 "Latin Influence of the Second Period: The Christianizing of Britain" の第2段落です.さほど長くない1節を,Taku さんと60分近くかけてじっくりと読みました.実に豊かな精読タイムでした.イングランドのキリスト教化がいかに困難だったか,そしていかにラッキーだったかを解説するくだりです.お時間のあるときに,ぜひ対象テキスト(Baugh and Cable, p. 79 より以下に掲載)を追いながら「超」精読のおもしろさを堪能していただければ.

It is not easy to appreciate the difficulty of the task that lay before this small band. Their problem was not so much to substitute one ritual for another as to change the philosophy of a nation. The religion that the Anglo-Saxons shared with the other Germanic tribes seems to have had but a slight hold on the people at the close of the sixth century; but their habits of mind, their ideals, and the action to which these gave rise were often in sharp contrast to the teachings of the New Testament. Germanic philosophy exalted physical courage, independence even to haughtiness, and loyalty to one's family or leader that left no wrong unavenged. Christianity preached meekness, humility, and patience under suffering and said that if a man struck you on one cheek you should turn the other. Clearly it was no small task that Augustine and his forty monks faced in trying to alter the age-old mental habits of such a people. They might even have expected difficulty in obtaining a respectful hearing. But they seem to have been men of exemplary lives, appealing personality, and devotion to purpose, and they owed their ultimate success as much to what they were as to what they said. Fortunately, upon their arrival in England one circumstance was in their favor. There was in the kingdom of Kent, in which they landed, a small number of Christians. But the number, though small, included no less a person than the queen. Æthelberht, the king, had sought his wife among the powerful nation of the Franks, and the princess Bertha had been given to him only on condition that she be allowed to continue undisturbed in her Christian faith. Æthelberht set up a small chapel near his palace in Kentwarabyrig (Canterbury), and there the priest who accompanied Bertha to England conducted regular services for her and the numerous dependents whom she brought with her. The circumstances under which Æthelberht received Augustine and his companions are related in the extract from Bede given §47 earlier. Æthelberht was himself baptized within three months, and his example was followed by numbers of his subjects. By the time Augustine died seven years later, the kingdom of Kent had become wholly Christian.

本節と関連の深い hellog 記事や heldio コンテンツは,「#5686. B&C の第60節 "Latin Influence of the Second Period" の第1段落を対談精読実況生中継しました」 ([2024-11-20-1]) に挙げたリンク集よりご参照ください.B&C の対談精読実況中継は,今後も時折実施していきたいと思います.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2024-11-20 Wed

■ #5686. B&C の第60節 "Latin Influence of the Second Period" の第1段落を対談精読実況生中継しました [bchel][latin][borrowing][christianity][link][voicy][heldio][anglo-saxon][st_augustine][history][bede][link]

今朝配信された Voicy heldio にて「#1270. 英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む (60-1) Latin Influence of the Second Period --- 対談精読実況中継」をお届けしています.英語史の古典的名著を読むシリーズはゆっくりと続いており,第60節まで進んできました.全部で264節ある本なので,まだまだ序盤戦ではあります.バックナンバー一覧は「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) よりご覧いただけます.

ニッチなシリーズなので通常は Voicy heldio の有料配信としてお届けしているのですが,たまに一緒に精読してくださる方をお招きして「対談精読実況中継」をフリーでお届けしています.今回の精読会は,金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)に仕切っていただきまして,helwa リスナーを中心に7名の方々が対面で参加されました(lacolaco さん,ykagata さん,藤原郁弥さん,ぷりっつさん,Lilimi さん,小河舜さん).たいへん熱い読書会となりました.(なお,今回の精読会とほぼ同じメンバーで『英語語源辞典』の読書会もたまに開催しています.heldio より「#1266. chair と sit --- 『英語語源辞典』精読会 with lacolaco さんたち」をお聴きください.)

今回の精読箇所は第60節 "Latin Influence of the Second Period: The Christianizing of Britain" です.古英語期におけるラテン語の影響について,イングランドのキリスト教化との関連で論じられています.3段落からなる節ですが,今回は1時間ほどかけて最初の1段落のみを超精読して終わりました(本シリーズの精度と速度のほどがわかるかと思います).以下に当該テキスト (Baugh and Cable, pp. 78--79) を掲載します.

60. Latin Influence of the Second Period: The Christianizing of Britain The greatest influence of Latin upon Old English was occasioned by the conversion of Britain to Roman Christianity beginning in 597. The religion was far from new in the island, because Irish monks had been preaching the gospel in the north since the founding of the monastery of Iona by Columba in 563. However, 597 marks the beginning of a systematic attempt on the part of Rome to convert the inhabitants and make England a Christian country. According to the well-known story reported by Bede as a tradition current in his day, the mission of St. Augustine was inspired by an experience of the man who later became Pope Gregory the Great. Walking one morning in the marketplace at Rome, he came upon some fair-haired boys about to be sold as slaves and was told that they were from the island of Britain and were pagans. "Alas! what pity," said he, "that the author of darkness is possessed of men of such fair countenances, and that being remarkable for such a graceful exterior, their minds should be void of inward grace?" He therefore again asked, what was the name of that nation and was answered, that they were called Angles. "Right," said he, "for they have an angelic face, and it is fitting that such should be co-heirs with the angels in heaven. What is the name," proceeded he, "of the province from which they are brought?" It was replied that the natives of that province were called Deiri. "Truly are they de ira," said he, "plucked from wrath, and called to the mercy of Christ. How is the king of that province called?" They told him his name was Ælla; and he, alluding to the name, said "Alleluia, the praise of God the Creator, must be sung in those parts." The same tradition records that Gregory wished himself to undertake the mission to Britain but could not be spared. Some years later, however, when he had become pope, he had not forgotten his former intention and looked about for someone whom he could send at the head of a missionary band. Augustine, the person of his choice, was a man well known to him. The two had lived together in the same monastery, and Gregory knew him to be modest and devout and thought him well suited to the task assigned him. With a little company of about forty monks Augustine set out for what seemed then like the end of the earth.

本節と関連の深い hellog 記事や heldio コンテンツを数多く公開してきたので,以下にリンクを張っておきます.

[ hellog 記事 ]

・ 「#2902. Pope Gregory のキリスト教布教にかける想いとダジャレ」 ([2017-04-07-1])

・ 「#5526. Pope Gregory のダジャレの現場を写本でみる」 ([2024-06-13-1])

・ 「#5444. 古英語の原文を読む --- 597年,イングランドでキリスト教の布教が始まる」 ([2024-03-23-1])

・ 「#5450. heldio の人気シリーズ復活 --- 「ゼロから学ぶはじめての古英語 --- Part 4 with 小河舜さん and まさにゃん」」 ([2024-03-29-1])

・ 「#5476. 「ゼロから学ぶはじめての古英語」 Part 5 with 小河舜さん and まさにゃん」 ([2024-04-24-1])

・ 「#5497. 「ゼロから学ぶはじめての古英語」 Part 6 with 小河舜さん and まさにゃん」 ([2024-05-15-1])

・ 「#5514. 「ゼロから学ぶはじめての古英語」 Part 7 with 小河舜さん and まさにゃん」 ([2024-06-01-1])

・ 「#5527. 「ゼロから学ぶはじめての古英語」 Part 8 with 小河舜さん and まさにゃん and 五所万実さん」 ([2024-06-14-1])

[ heldio コンテンツ ]

・ 「#1030. 「はじめての古英語」生放送 with 小河舜さん&まさにゃん --- Bede を読む」

・ 「#1057. 「はじめての古英語」生放送 with 小河舜さん&まさにゃん --- Bede を読む (2)」

・ 「#1078. 「はじめての古英語」生放送 with 小河舜さん&まさにゃん --- Bede を読む (3)」

・ 「#1093.「はじめての古英語」生放送(第7弾) with 小河舜さん&まさにゃん --- Bede を読む (4)」

・ 「#1107. 「はじめての古英語」生放送(第8弾) with 小河舜さん&まさにゃん --- Bede を読む (5)」

今後もこの精読シリーズは続いていきます.ぜひ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013. を入手して,お付き合いいただければ.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2024-11-11 Mon

■ #5677. 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』の接辞リスト(129種) [etymology][prefix][suffix][vocabulary][hel_education][lexicology][word_formation][derivation][derivative][morphology][latin][greek][review]

昨日の記事「#5676. 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』の300語根」 ([2024-11-10-1]) に引き続き,同書の付録 (344--52) に掲載されている主要な接辞のリストを挙げたいと思います.接頭辞 (prefix) と接尾辞 (suffix) を合わせて129種の接辞が紹介されています.

【 主な接頭辞 】

| a-, an- | ない (without) |

| ab-, abs- | 離れて,話して (away) |

| ad-, a-, ac-, af-, ag-, al-, an-, ap-, ar-, as-, at- | …に (to) |

| ambi- | 周りに (around) |

| anti-, ant- | 反… (against) |

| bene- | よい (good) |

| bi- | 2つ (two) |

| co- | 共に (together) |

| com-, con-, col-, cor- | 共に (together);完全に (wholly) |

| contra-, counter- | 反対の (against) |

| de- | 下に (down);離れて (away);完全に (wholly) |

| di- | 2つ (two) |

| dia- | 横切って (across) |

| dis-, di-, dif- | ない (not);離れて,別々に (apart) |

| dou-, du- | 2つ (two) |

| en-, em- | …の中に (into);…にする (make) |

| ex-, e-, ec-, ef- | 外に (out) |

| extra- | …の外に (outside) |

| fore- | 前もって (before) |

| in-, im-, il-, ir-, i- | ない,不,無,非 (not) |

| in-, im- | 中に,…に (in);…の上に (on) |

| inter- | …の間に (between) |

| intro- | 中に (in) |

| mega- | 巨大な (large) |

| micro- | 小さい (small) |

| mil- | 1000 (thousand) |

| mis- | 誤って (wrongly);悪く (badly) |

| mono- | 1つ (one) |

| multi- | 多くの (many) |

| ne-, neg- | しない (not) |

| non- | 無,非 (not) |

| ob-, oc-, of-, op- | …に対して,…に向かって (against) |

| out- | 外に (out) |

| over- | 越えて (over) |

| para- | わきに (beside) |

| per- | …を通して (through);完全に (wholly) |

| post- | 後の (after) |

| pre- | 前に (before) |

| pro- | 前に (forward) |

| re- | 元に (back);再び (again);強く (strongly) |

| se- | 別々に (apart) |

| semi- | 半分 (half) |

| sub-, suc-, suf-, sum-, sug-, sup-, sus- | 下に (down),下で (under) |

| super-, sur- | 上に,越えて (over) |

| syn-, sym- | 共に (together) |

| tele- | 遠い (distant) |

| trans- | 越えて (over) |

| tri- | 3つ (three) |

| un- | ない (not);元に戻して (back) |

| under- | 下に (down) |

| uni- | 1つ (one) |

【 名詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -age | 状態,こと,もの |

| -al | こと |

| -ance | こと |

| -ancy | 状態,もの |

| -ant | 人,もの |

| -ar | 人 |

| -ary | こと,もの |

| -ation | すること,こと |

| -cle | もの,小さいもの |

| -cracy | 統治 |

| -ee | される人 |

| -eer | 人 |

| -ence | 状態,こと |

| -ency | 状態,もの |

| -ent | 人,もの |

| -er, -ier | 人,もの |

| -ery | 状態,こと,もの;類,術;所 |

| -ess | 女性 |

| -hood | 状態,性質,期間 |

| -ian | 人 |

| -ics | 学,術 |

| -ion, -sion, -tion | こと,状態,もの |

| -ism | 主義 |

| -ist | 人 |

| -ity, -ty | 状態,こと,もの |

| -le | もの,小さいもの |

| -let | もの,小さいもの |

| -logy | 学,論 |

| -ment | 状態,こと,もの |

| -meter | 計 |

| -ness | 状態,こと |

| -nomy | 法,学 |

| -on, -oon | 大きなもの |

| -or | 人,もの |

| -ory | 所 |

| -scope | 見るもの |

| -ship | 状態 |

| -ster | 人 |

| -tude | 状態 |

| -ure | こと,もの |

| -y | こと,集団 |

【 形容詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -able | できる,しやすい |

| -al | …の,…に関する |

| -an | …の,…に関する |

| -ant | …の,…の性質の |

| -ary | …の,…に関する |

| -ate | …の,…のある |

| -ative | …的な |

| -ed | …にした,した |

| -ent | している |

| -ful | …に満ちた |

| -ible | できる,しがちな |

| -ic | …の,…のような |

| -ical | …の,…に関する |

| -id | …状態の,している |

| -ile | できる,しがちな |

| -ine | …の,…に関する |

| -ior | もっと… |

| -ish | ・・・のような |

| -ive | ・・・の,・・・の性質の |

| -less | ・・・のない |

| -like | ・・・のような |

| -ly | ・・・のような;・・・ごとの |

| -ory | ・・・のような |

| -ous | ・・・に満ちた |

| -some | ・・・に適した,しがちな |

| -wide | ・・・にわたる |

【 動詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -ate | ・・・にする,させる |

| -en | ・・・にする |

| -er | 繰り返し・・・する |

| -fy, -ify | ・・・にする |

| -ish | ・・・にする |

| -ize | ・・・にする |

| -le | 繰り返し・・・する |

【 副詞をつくる接尾辞 】

| -ly | ・・・ように |

| -ward | ・・・の方へ |

| -wise | ・・・ように |

・ 池田 和夫 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』 研究社,2019年.

2024-11-10 Sun

■ #5676. 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』の300語根 [etymology][prefix][suffix][vocabulary][hel_education][lexicology][word_formation][derivation][derivative][morphology][latin][greek][review]

英語ボキャビルのための本を紹介します.研究社から出版されている『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』です.300の語根を取り上げ,語根と意味ベースで派生語2500語を学習できるように構成されています.研究社の伝統ある『ライトハウス英和辞典』『カレッジライトハウス英和辞典』『ルミナス英和辞典』『コンパスローズ英和辞典』の辞書シリーズを通じて引き継がれてきた語根コラムがもとになっています.

選ばれた300個の語根は,ボキャビル以外にも,英語史研究において何かと役に立つリストとなっています.目次に従って,以下に一覧します.

cess (行く)

ceed (行く)

cede (行く)

gress (進む)

vent (来る)

verse (向く)

vert (向ける)

cur (走る)

pass (通る)

sta (立つ)

sist (立つ)

sti (立つ)

stitute (立てた)

stant (立っている)

stance (立っていること)

struct (築く)

fact (作る,なす)

fic (作る)

fect (作った)

gen (生まれ)

nat (生まれる)

crease (成長する)

tain (保つ)

ward (守る)

serve (仕える)

ceive (取る)

cept (取る)

sume (取る)

cap (つかむ)

mote (動かす)

move (動く)

gest (運ぶ)

fer (運ぶ)

port (運ぶ)

mit (送る)

mis (送られる)

duce (導く)

duct (導く)

secute (追う)

press (押す)

tract (引く)

ject (投げる)

pose (置く)

pend (ぶら下がる)

tend (広げる)

ple (満たす)

cide (切る)

cise (切る)

vary (変わる)

alter (他の)

gno (知る)

sent (感じる)

sense (感じる)

cure (注意)

path (苦しむ)

spect (見る)

vis (見る)

view (見る)

pear (見える)

speci (見える)

pha (現われる)

sent (存在する)

viv (生きる)

act (行動する)

lect (選ぶ)

pet (求める)

quest (求める)

quire (求める)

use (使用する)

exper (試みる)

dict (言う)

log (話す)

spond (応じる)

scribe (書く)

graph (書くこと)

gram (書いたもの)

test (証言する)

prove (証明する)

count (数える)

qua (どのような)

mini (小さい)

plain (平らな)

liber (自由な)

vac (空の)

rupt (破れた)

equ (等しい)

ident (同じ)

term (限界)

fin (終わり,限界)

neg (ない)

rect (真っすぐな)

prin (1位)

grade (段階)

part (部分)

found (基礎)

cap (頭)

medi (中間)

popul (人々)

ment (心)

cord (心)

hand (手)

manu (手)

mand (命じる)

fort (強い)

form (形,形作る)

mode (型)

sign (印)

voc (声)

litera (文字)

ju (法)

labor (労働)

tempo (時)

uni (1つ)

dou (2つ)

cent (100)

fare (行く)

it (行く)

vade (行く)

migrate (移動する)

sess (座る)

sid (座る)

man (とどまる)

anim (息をする)

spire (息をする)

fa (話す)

fess (話す)

cite (呼ぶ)

claim (叫ぶ)

plore (叫ぶ)

doc (教える)

nounce (報じる)

mon (警告する)

audi (聴く)

pute (考える)

tempt (試みる)

opt (選ぶ)

cri (決定する)

don (与える)

trad (引き渡す)

pare (用意する)

imper (命令する)

rat (数える)

numer (数)

solve (解く)

sci (知る)

wit (知っている)

memor (記憶)

fid (信じる)

cred (信じる)

mir (驚く)

pel (追い立てる)

venge (復讐する)

pone (置く)

ten (保持する)

tin (保つ)

hibit (持つ)

habit (持っている)

auc (増す)

ori (昇る)

divid (分ける)

cret (分ける)

dur (続く)

cline (傾く)

flu (流れる)

cas (落ちる)

cid (落ちる)

cease (やめる)

close (閉じる)

clude (閉じる)

draw (引く)

trai (引っ張る)

bat (打つ)

fend (打つ)

puls (打つ)

cast (投げる)

guard (守る)

medic (治す)

nur (養う)

cult (耕す)

ly (結びつける)

nect (結びつける)

pac (縛る)

strain (縛る)

strict (縛られた)

here (くっつく)

ple (折りたたむ)

plic (折りたたむ)

ploy (折りたたむ)

ply (折りたたむ)

tribute (割り当てる)

tail (切る)

sect (切る)

sting (刺す)

tort (ねじる)

frag (壊れる)

fuse (注ぐ)

mens (測る)

pens (重さを量る)

merge (浸す)

velop (包む)

veil (覆い)

cover (覆う;覆い)

gli (輝く)

prise (つかむ)

cert (確かな)

sure (確かな)

firm (確実な)

clar (明白な)

apt (適した)

due (支払うべき)

par (等しい)

human (人間の)

common (共有の)

commun (共有の)

semble (一緒に)

simil (同じ)

auto (自ら)

proper (自分自身の)

potent (できる)

maj (大きい)

nov (新しい)

lev (軽い)

hum (低い)

cand (白い)

plat (平らな)

minent (突き出た)

sane (健康な)

soph (賢い)

sacr (神聖な)

vict (征服した)

text (織られた)

soci (仲間)

demo (民衆)

civ (市民)

polic (都市)

host (客)

femin (女性)

patr (父)

arch (長)

bio (命,生活,生物)

psycho (精神)

corp (体)

face (顔)

head (頭)

chief (頭)

ped (足)

valu (価値)

delic (魅力)

grat (喜び)

hor (恐怖)

terr (恐れさせる)

fortune (運)

hap (偶然)

mort (死)

art (技術)

custom (習慣)

centr (中心)

eco (環境)

circ (円,環)

sphere (球)

rol (回転;巻いたもの)

tour (回る)

volve (回る)

base (基礎)

norm (標準)

ord (順序)

range (列)

int (内部の)

front (前面)

mark (境界)

limin (敷居)

point (点)

punct (突き刺す)

phys (自然)

di (日)

hydro (水)

riv (川)

mari (海)

sal (塩)

aster (星)

camp (野原)

mount (山)

insula (島)

vi (道)

loc (場所)

geo (土地)

terr (土地)

dom (家)

court (宮廷)

cave (穴)

bar (棒)

board (板)

cart (紙)

arm (武装,武装する)

car (車)

leg (法律)

reg (支配する)

her (相続)

gage (抵当)

merc (取引)

・ 池田 和夫 『語根で覚えるコンパスローズ英単語』 研究社,2019年.

2024-10-29 Tue

■ #5664. 初期近代のジェスチャーへの関心の高まり [gesture][emode][gesture][paralinguistics][history_of_linguistics][latin][lingua_franca][vernacular]

西洋の初期近代では普遍言語や普遍文字への関心が高まったが,同様の趣旨としてジェスチャー (gesture) へも関心が寄せられるようになった.Kendon (73) によれば,その背景は以下の通り.

The expansion of contacts between Europeans and peoples of other lands, especially in the New World, led to an enhanced awareness of the diversity of spoken languages, and because explorers and missionaries had reported successful communication by gesture, the idea rose that gesture could form the basis of a universal language. The idea of a universal language that could overcome the divisions between peoples brought about by differences in spoken languages was longstanding. However, interest in it became widespread, especially in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, in part because, as Latin began to be replaced with vernaculars, the need for a new lingua franca was felt. There were philosophical and political reasons as well, and there developed the idea that a language should be created whose meanings were fixed, which could be written or expressed in forms that would be comprehensible, regardless of a person's spoken language. The idea that humans share a 'universal language of the hands,' mentioned by Quintilian, was taken up afresh by Bonifaccio. In his L'arte dei cenni ('The art of signs') of 1616 (perhaps the first book ever published to be devoted entirely to bodily expression) . . . , he hoped that his promotion of the 'mute eloquence' of bodily signs would contribute to the restoration of the natural language of the body, given to all mankind by God, and so overcome the divisions created by the artificialities of spoken languages.

西洋の初期近代におけるジェスチャーへの関心は,新世界での見知らぬ諸言語との接触,リンガフランカとしてのラテン語の衰退,哲学的・政治的な観点からの普遍言語への関心,「自然な肉体言語」の再評価などに裏付けられていたという解説だ.関連して「#5128. 17世紀の普遍文字への関心はラテン語の威信の衰退が一因」 ([2023-05-12-1]) の議論も思い出される.

・ Kendon, Adam. "History of the Study of Gesture." Chapter 3 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. Ed. Keith Allan. Oxford: OUP, 2013. 71--89.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow