2014-08-12 Tue

■ #1933. 言語変化と monitoring (2) [communication][linguistics][language_change][phonetics][speech_perception][causation][speed_of_change][usage-based_model][monitoring]

昨日の記事 ([2014-08-11-1]) で引用した monitoring に関する Smith の文章で,Lyons が参照されていた.Lyons (111) に当たってみると,言語音の産出と理解について論じている箇所で,話者と聴者の互いの monitoring 作用を前提とすることが重要だという趣旨の議論において,feedback あるいは monitoring という表現が現われている.

In the case of speech, we are not dealing with a system of sound-production and sound-reception in which the 'transmitter' (the speaker) and the 'receiver' (the hearer) are completely separate mechanisms. Every normal speaker of a language is alternately a producer and a receiver. When he is speaking, he is not only producing sound; he is also 'monitoring' what he is saying and modulating his speech, unconsciously correlating his various articulatory movements with what he hears and making continual adjustments (like a thermostat, which controls the source of heat as a result of 'feedback' from the temperature readings). And when he is listening to someone else speaking, he is not merely a passive receiver of sounds emitted by the speaker: he is registering the sounds he hears (interpreting the acoustic 'signal') in the light of his own experience as a speaker, with a 'built-in' set of contextual cues and expectancies.

言語使用者は調音音声学的機構と音響音声学的機構をともに備えているばかりでなく,言語音の産出と理解において双方を連動させている,という仮説がここで唱えられている.関連して「#1656. 口で知覚するのか耳で知覚するのか」 ([2013-11-08-1]) を参照されたい.

Lyons は,主として言語音の産出と理解における monitoring の作用を強調しているが,monitoring の作用は音声以外の他の言語部門にも同様に見られると述べている.

It may be pointed out here that the principle of 'feedback' is not restricted to the production and reception of physical distinctions in the substance, or medium, in which language is manifest. It operates also in the determination of phonological and grammatical structure. Intrinsically ambiguous utterances will be interpreted in one way, rather than another, because certain expectancies have been established by the general context in which the utterance is made or by the previous discourse . . . . (111)

monitoring と関連して慣習 (established),文脈 (context),キュー (cue) というキーワードが出てくれば,次には共起 (collocation) や頻度 (frequency) などという用語が出てきてもおかしくなさそうだ.言語変化論の観点からは,Usage-Based Grammar や「#1406. 束となって急速に生じる文法変化」 ([2013-03-03-1]) でみた "clusters of bumpy change" の考え方とも関係するだろう.昨今は,従来の話者主体ではなく聴者主体の言語(変化)論が多く聞かれるようになってきたが,monitoring という考え方は,言語において「話者=聴者」であることを再認識させてくれるキーワードといえるかもしれない.関連して,聞き手の関与する意味変化について「#1873. Stern による意味変化の7分類」 ([2014-06-13-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Lyons, John. Introduction to Theoretical Linguistics. Cambridge: CUP, 1968.

2014-08-11 Mon

■ #1932. 言語変化と monitoring (1) [communication][linguistics][language_change][prescriptive_grammar][diachrony][causation][monitoring]

Smith の抱く言語変化観を表わすものとして「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1]) と「#1928. Smith による言語レベルの階層モデルと動的モデル」 ([2014-08-07-1]) を紹介した.これらは機械的な言語変化の見方であり,人間不在の印象を与えるかもしれないが,Smith の言語変化論は決して言語の社会的な側面,話者と聴者と言語の関係をないがしろにしているわけではない.Smith (49) は,言語変化の種としての variation の存在,および variation のなかからの個々の言語項の選択という行為は,言語使用者が不断に実践している monitoring という作用と深い関わりがあると述べている.

Human beings are social creatures, and not simply transmitters (speakers) or receivers (hearers); they are both. When humans speak, they are not only producing sounds and grammar and vocabulary; they are also monitoring what they and others say by listening, and evaluating the communicative efficiency of their speech for the purposes for which it is being used: communicative purposes which are not only to do with the conveying and receiving of information, but also to do with such matters as signalling the social circumstances of the interaction taking place. And what humans hear is constantly being monitored, that is, compared with their earlier experience as speakers and hearers. . . . / This principle of monitoring, or feedback as it is sometimes called (Lyons 1968: 111), is crucial to an understanding of language-change.

話者は自分の発する言葉がいかに理解されるかに常に注意を払っているし,聴者は相手の発した言葉を理解するのに常にその言語の標準的な体系を参照している.話者も聴者も,発せられた言葉に逐一監視の目を光らせており,互いにチェックし合っている.2人の言語体系は音声,文法,語彙の細部において若干相違しているだろうが,コミュニケーションに伴うこの不断の照合作業ゆえに,互いに大きく逸脱することはない.2人の言語体系は焦点を共有しており,その焦点そのものが移動することはあっても,それは両者がともに移動させているのである.これが,言語(変化)における monitoring の役割だという.

人の言葉遣いが一生のなかで変化し得ることについて「#866. 話者の意識に通時的な次元はあるか?」 ([2011-09-10-1]) や「#1890. 歳とともに言葉遣いは変わる」 ([2014-06-30-1]) で考察してきたが,monitoring という考え方は,この問題にも光を当ててくれるだろう.個人が生きて言語を使用するなかで,常に対話者との間に monitoring 機能を作用させ,その monitoring の結果として,自らも言語体系の焦点を少しずつ移動させていくかもしれないし,相手にも焦点の移動を促していくかもしれない.

monitoring は,言語における規範主義とも大いに関係する.通常,話者や聴者の monitoring の参照点は,互いの言語使用,あるいはもう少し広く,彼らが属する言語共同体における一般の言語使用だろう.しかし,「#1929. 言語学の立場から規範主義的言語観をどう見るべきか」 ([2014-08-08-1]) で示唆したように,規範主義的言語観がある程度言語共同体のなかに浸透すると,規範文法そのものが monitoring の参照点となりうる.つまり,自分や相手がその規範を遵守しているかどうかを逐一チェックし合うという,通常よりもずっと息苦しい状況が生じる.規範主義的言語観の発達は,monitoring という観点からみれば,monitoring の質と量を重くさせる過程であるともいえるかもしれない.

・ Smith, Jeremy J. An Historical Study of English: Function, Form and Change. London: Routledge, 1996.

2014-08-07 Thu

■ #1928. Smith による言語レベルの階層モデルと動的モデル [language_change][linguistics][systemic_regulation]

言語変化のモデルの例として,過去の記事で「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1]) や「#1600. Samuels の言語変化モデル」 ([2013-09-13-1]) などを紹介してきた.Smith は,言語変化のモデルに先立って,言語そのもののモデル,あるいは言語を構成する各レベルの関係図をも提示しており,それに基づいて言語変化を論じている.

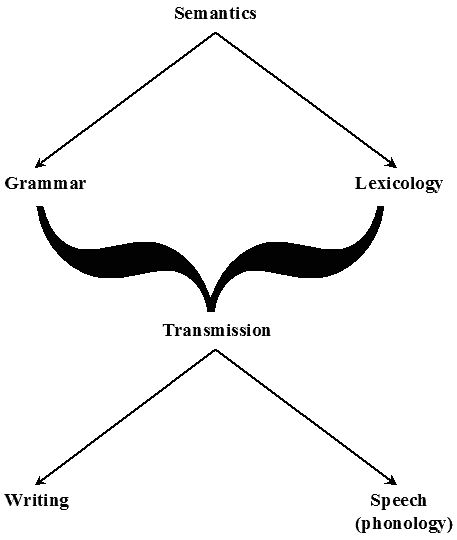

まず,Smith (4) の "The levels of language (hierarchical model)" を再現する.

これは,言語の最も深いレベルに Semantics (意味)があり,次にそれが Grammar (文法)と Lexicology (語彙)によって表現され,次いでそれらが Transmission (伝達)の過程を経て,最後に Speech (話し言葉)あるいは Writing (書き言葉)という媒体により顕現するという階層モデルである.ここで,Transmission として話し言葉と書き言葉が同列に置かれていることは注目に値する.言語は音声であるとする20世紀言語学の常識から脱し,書き言葉を言語学の現場に引き戻そうとする意志が強く感じられる.この言語観については「#1665. 話しことばと書きことば (4)」 ([2013-11-17-1]),「#748. 話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-05-15-1]) も参照されたい.

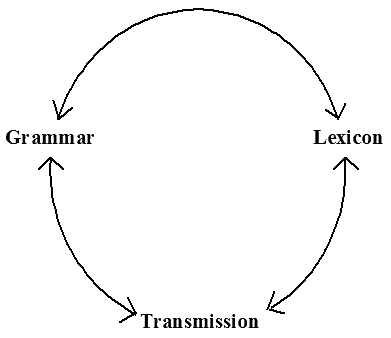

上の階層モデルは静的である.言語変化という動的な過程を扱おうと思えば,このままの静的なモデルでは利用し続けることができない.Smith (5) が言語変化について述べているとおり,"any given linguistic event is the result of complex interaction between levels of language, and between language itself and the sociohistorical setting in which it is situated" である.そこで,Smith (5) は以下の動的なモデル "The levels of language (dynamic model)" を提示した.

これは,階層の上下の区別を設けずに,相互作用を重視した動的なモデルである.Grammar, Lexicon, Transmission の3者ががっちりとスクラムを組んだ言語体系 (cf. "système où tout se tient") において,ある一点で生じた変化は,体系内の別の部分にも影響を与えざるを得ない.なお,この図に Semantics が含まれていないのは,意味はいずれのレベルとも直接に関わるものであり,この図の背面(あるいは前面?)で常に作用しているという前提があるからのようだ (Smith 5) .

Smith は言語変化における言語外的な要素 ("the sociohistorical setting") の役割も重視しているが,これを組み込んだ第3のモデルは図示していない.しかし,彼の師匠の Samuels が提示した「#1600. Samuels の言語変化モデル」 ([2013-09-13-1]) を念頭においていることは確かのようだ.

・ Smith, Jeremy J. An Historical Study of English: Function, Form and Change. London: Routledge, 1996.

2014-07-11 Fri

■ #1901. apparent time と real time [age_grading][sociolinguistics][language_change][methodology][terminology][diachrony]

「#1890. 歳とともに言葉遣いは変わる」 ([2014-06-30-1]) の記事で,age-grading という社会言語学上の概念と用語を紹介した.言語変化の実証的研究において,age-grading の可能性は常に念頭においておかなければならない.というのは,観察者が,現在起こっている歴史的な(したがって単発の)言語変化とであると思い込んでいた現象が,実際には毎世代繰り返されている age-grading にすぎなかったということがあり得るからだ.逆に,毎世代繰り返される age-grading と信じている現象が,実際にはその時代に特有の一回限りの言語変化であるかもしれない.

では,観察中の言語現象が真正の言語変化なのか age-grading なのかを見分けるには,どうすればよいのだろうか.現在進行中の言語変化を観察する方法論として,2種類の視点が知られている.apparent time と real time である.Trudgill の用語集より,それぞれ引用しよう.

apparent-time studies Studies of linguistic change which attempt to investigate language changes as they happen, not in real time (see real-time studies), but by comparing the speech of older speakers with that of younger speakers in a given community, and assuming that differences between them are due to changes currently taking place within the dialect of that community, with older speakers using older forms and younger speakers using newer forms. As pointed out by William Labov, who introduced both the term and the technique, it is important to be able to distinguish in this comparison of age-groups between ongoing language changes and differences that are due to age-grading (Trudgill 9--10)

real-time studies Studies of linguistic change which attempt to investigate language changes as they happen, not in apparent time by comparing the speech of older speakers with that of younger speakers in a given community, but in actual time, by investigating the speech of a particular community and then returning a number of years later to investigate how speech in this community has changed. In secular linguistics, two different techniques have been used in real-time studies. In the first, the same informants are used in the follow-up study as in the first study. In the second, different informants, who were too young to be included in the first study or who were not then born, are investigated in the follow-up study. One of the first linguists to use this technique was Anders Steinsholt, who carried out dialect research in the southern Norwegian community of Hedrum, near Larvik, in the late 1930s, and then returned to carry out similar research in the late 1960s. (Trudgill 109)

apparent-time studies は,通時軸の一断面において世代差の言語使用を比較対照することで,現在進行中の言語変化を間接的に突き止めようとする方法である.現在という1点のみに立って調査できる方法として簡便ではあるが,明らかになった世代差が,果たして真正の言語変化なのか age-grading なのか,別の方法で(通常は real-time studies によって)見極める必要がある.

一方,real-time studies は,通時軸上の複数の点において調査する必要があり,その分実際上の手間はかかるが,真正の言語変化か age-grading かを見分けるのに必要なデータを生で入手することができるという利点がある.

理論的,実際的な観点からは,言語変化を調査する際には両方法を組み合わせるのが妥当な解決策となることが多い.結局のところ,共時的な調査を常に続け,調査結果をデータベースに積み重ねて行くことが肝心なのだろう.同じ理由で,定期的に共時的コーパスを作成し続けていくことも,歴史言語学者にとって重要な課題である.

apparent time と real time については「#919. Asia の発音」 ([2011-11-02-1]) でも触れたので,参照を.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2014-06-30 Mon

■ #1890. 歳とともに言葉遣いは変わる [age_grading][generative_grammar][language_change][terminology]

人の言葉遣いは,一生の中でも変化する.世の中の言葉遣いが変化すれば個人もそれに応じて変化するということは,誰しも私的に体験している通りである.新語や死語などの語彙の盛衰はいうに及ばず,発音,語法,文法の変化にも気づかないうちに応じている.生成理論などでは,個人の文法は一度習得されると生涯固定され,文法変化は次世代の子供による異分析を通じてのみ起こりうると考えられているが,実際の言語運用においては,社会で進行している言語変化は,確かに個人の言語に反映されている.世の中で通時的に言語変化が進んでいるのであれば,同じタイミングで通時的に生きている話者がそれを受容し,自らの言葉遣いに反映するというのは,自然の成り行きだろう.

しかし,上記の意味とは異なる意味で,「歳とともに言葉遣いは変わる」ことがある.例えば,世の中で通時的に起こっている言語変化とは直接には関係せずに,歳とともに使用語彙が変化するということは,みな経験があるだろう.幼児期には幼児期に特有の話し方が,修学期には修学期を特徴づける言葉遣いが,社会人になれば社会人らしい表現が,中高年になれば中高年にふさわしいものの言い方がある.個人は,歳とともにその年代にふさわしい言葉遣いを身につけてゆく.このパターンは,世の中の通時的な言語変化に順応して生涯のなかで言葉遣いを変化させてゆくのと異なり,通常,毎世代繰り返されるものであり,成長とともに起こる変化である.これを社会言語学では age-grading と呼んでいる.この概念と用語について,2点引用しよう.

age-grading A phenomenon in which speakers in a community gradually alter their speech habits as they get older, and where this change is repeated in every generation. It has been shown, for example, that in some speech communities it is normal for speakers to modify their language in the direction of the acrolect as they approach middle-age, and then to revert to less prestigious speech patterns after they reach retirement age. Age-grading is something that has to be checked for in apparent-time studies of linguistic change to ensure that false conclusions are not being drawn from linguistic differences between generations. (Trudgill 6)

. . . it is a well attested fact that particularly young speakers use specific linguistic features as identity markers, but give them up in later life. That is, instead of keeping their way of speaking as they grow older, thereby slowly replacing the variants used by the speakers of the previous generations, they themselves grow out of their earlier way of speaking. (Schendl 75)

Wardhaugh (200-01) に述べられているカナダ英語における age-grading の例を挙げよう.カナダの Ontario 南部と Toronto では,子供たちはアルファベットの最後の文字を,アメリカ発の未就学児向けのテレビ番組の影響で "zee" と発音するが,成人に達すると "zed" へとカナダ化する.これは何世代にもわたって繰り返されており,典型的な age-grading の例といえる.

また,小学生の言語は,何世紀ものあいだ受け継がれてきた保守的な形態に満ちていると一般に言われる.古くから伝わる数え方や遊び用語などが連綿と生き続けているのである.また,青年期には自分の世代と数歳上の先輩たちの世代との差別化をはかり,革新的な言葉遣いを生み出す傾向が,いつの時代にも見られる.成人期になると,仕事上の目的,また "linguistic market-place" の圧力のもとで,多かれ少なかれ標準的な形態を用いる傾向が生じるともいわれる (Hudson 14--16) .このように,年代別の言語的振る舞いは,時代に関わらずある種の傾向を示す.

東 (91--92) より,「#1529. なぜ女性は言語的に保守的なのか (3)」 ([2013-07-04-1]) で簡単に触れた age-grading について引用する.

さまざまな社会で,年齢と言語のバリエーションの関係が研究されているが,おもしろい発見の1つは,どの社会階級のグループについてもいえるのだが,思春期(あるいはもう少し若い)年代の若者は社会的に低くみられているバリエーションを大人よりも頻繁に好んで使う傾向があるということであり,これは covert prestige (潜在的権威)と呼ばれている.〔中略〕別な言い方をすれば,年齢が上がるにつれて,社会的に低いと考えられている文法使用は少なくなっていくということになる(これは age grading とよばれている).

各年齢層には社会的にその層にふさわしいと考えられている振る舞いが期待され,人々は概ねそれに従って社会生活を営んでいる.この振る舞いのなかには,当然,言葉遣いも含まれており,これが age-grading の駆動力となっているのだろう.

関連して,「#866. 話者の意識に通時的な次元はあるか?」 ([2011-09-10-1]) も参照.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

・ Wardhaugh, Ronald. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 6th ed. Malden: Blackwell, 2010.

・ Schendl, Herbert. Historical Linguistics. Oxford: OUP, 2001.

・ Hudson, R. A. Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 1996.

・ 東 照二 『社会言語学入門 改訂版』,研究社,2009年.

2014-06-26 Thu

■ #1886. AAVE の分岐仮説 [aave][sociolinguistics][language_change][speed_of_change][ame][variety][sapir-whorf_hypothesis]

昨日の記事「#1885. AAVE の文法的特徴と起源を巡る問題」 ([2014-06-25-1]) で,AAVE の特徴と起源に関する考え方を整理した.もし変種間の言語的な差異はその話者集団の社会的な差異に対応すると考えることができるのであれば,アメリカで主として黒人の用いる AAVE と主として白人の用いる Standard English により近い変種との言語的な差異は,アメリカの黒人社会と白人社会の差異を表わしているとみることができる.差異とは見方によっては乖離ともとらえられ,その大小は社会的,政治的,イデオロギー的,人種的な含意をもつことになる.

Creolist Hypothesis は,元来標準変種から大きく乖離していたクレオール語が,脱クレオール化 (decreolization) の過程を通じて標準変種に近づいてきたと仮定している.つまり,両変種(そして含意では両変種の話者集団)の歴史は合流 (convergence) の方向を示してきたという解釈になる.一方,Anglicist Hypothesis は,イギリス諸方言がアメリカにもたらされ,黒人変種と白人変種という大きな2つの流れへと分岐し,現在に至るまでその分岐状態が保たれているのだとする.つまり,両変種(そして含意では両変種の話者集団)の歴史は分岐 (divergence) の方向を示してきたという解釈になる.

では,現在のアメリカ社会において,言語的にはどちらの潮流が観察されるのだろうか.現在生じていることを客観的に判断することは常に難しいが,黒人変種と白人変種は分岐する方向にあると唱える "divergence hypothesis" が論争の的となっている.Trudgill (60) の説明を引用する.

Research carried out in the 1990s appears to suggest that, even if AAVE is descended from an English-based Creole which has, over the centuries, come to resemble more and more closely the English spoken by other Americans, this process has now begun to swing into reverse. The suggestion is that AAVE and white dialects of English are currently beginning to grow apart. In other words, changes are taking place in white dialects which are not occurring in AAVE, and vice versa. Quite naturally, this hypothesis has aroused considerable attention in the United States because, if true, it would provide a dramatic reflection of the racially divided nature of American society. The implication is that these linguistic divergences are taking place because of a lack of integration between black and white communities in the USA, particularly in urban areas.

具体的な事例を挙げれば,Philadelphia などでは白人変種では二重母音 [aɪ] > [əɪ] の変化が進行中だが,同じ都市の黒人変種にはこれが生じていない.一方,AAVE では未来結果相を表わす be done 構文 (ex. I'll be done killed that motherfucker if he tries to lay a hand on my kid again.) が独自に発達してきているが,白人変種には反映されていない.

サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) に舞い戻ってしまうが,言語と社会の関係がどの程度直接的であるかを判断することがたやすくないことを考えれば,言語問題を即社会問題化しようとする傾向には慎重でなければならないだろう.特にアメリカでは,この話題は政治問題,人種問題,イデオロギー問題へと化しやすい.客観的な言語学の観点から,2つの変種の言語変化の潮流を見極める態度が必要である.言うは易し,ではあるが.

通時言語学における divergence と convergence については,「#627. 2変種間の通時比較によって得られる言語的差異の類型論」 ([2011-01-14-1]) および「#628. 2変種間の通時比較によって得られる言語的差異の類型論 (2)」 ([2011-01-15-1]) を参照.

・ Trudgill, Peter. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin, 2000.

2014-05-28 Wed

■ #1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力 [verb][conjugation][emode][language_change][causation][suffix][inflection][phonotactics][3sp]

「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]),「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]) と続けて3単現の -th → -s の変化について取り上げてきた.この変化をもたらした要因については諸説が唱えられている.また,「#1413. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s」 ([2013-03-10-1]) で触れた通り,3複現においても平行的に -th → -s の変化が起こっていたらしい証拠があり,2つの問題は絡み合っているといえる.

北部方言では,古英語より直説法現在の人称語尾として -es が用いられており,中部・南部の -eþ とは一線を画していた.したがって,中英語以降,とりわけ初期近代英語での -th → -s の変化は北部方言からの影響だとする説が古くからある.一方で,いずれに方言においても確認された2単現の -es(t) の /s/ が3単現の語尾にも及んだのではないかとする,パラダイム内での類推説もある.その他,be 動詞の is の影響とする説,音韻変化説などもあるが,いずれも決定力を欠く.

諸説紛々とするなかで,Jespersen (17--18) は音韻論の観点から「効率」説を展開する.音素配列における「最小努力の法則」 ('law of least effort') の説と言い換えてもよいだろう.

In my view we have here an instance of 'Efficiency': s was in these frequent forms substituted for þ because it was more easily articulated in all kinds of combinations. If we look through the consonants found as the most important elements of flexions in a great many languages we shall see that t, d, n, s, r occur much more frequently than any other consonant: they have been instinctively preferred for that use on account of the ease with which they are joined to other sounds; now, as a matter of fact, þ represents, even to those familiar with the sound from their childhood, greater difficulty in immediate close connexion with other consonants than s. In ON, too, þ was discarded in the personal endings of the verb. If this is the reason we understand how s came to be in these forms substituted for th more or less sporadically and spontaneously in various parts of England in the ME period; it must have originated in colloquial speech, whence it was used here and there by some poets, while other writers in their style stuck to the traditional th (-eth, -ith, -yth), thus Caxton and prose writers until the 16th century.

言語の "Efficiency" とは言語の進歩 (progress) にも通じる.(妙な言い方だが)Jespersen だけに,実に Jespersen 的な説と言えるだろう.Jespersen 的とは何かについては,「#1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観」 ([2014-01-19-1]) を参照されたい.[s] と [θ] については,「#842. th-sound はまれな発音か」 ([2011-08-17-1]) と「#1248. s と th の調音・音響の差」 ([2012-09-26-1]) もどうぞ.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

2014-05-14 Wed

■ #1843. conservative radicalism [language_change][personal_pronoun][contact][homonymic_clash][homonymy][conjunction][demonstrative][me_dialect][wave_theory][systemic_regulation][causation][functionalism][she]

「#941. 中英語の言語変化はなぜ北から南へ伝播したのか」 ([2011-11-24-1]) は,いまだ説得力をもって解き明かされていない英語史の謎である.常識的には,社会的影響力のある London を中心とするイングランド南部方言が言語変化の発信地となり,そこから北部など周辺へ伝播していくはずだが,中英語ではむしろ逆に北部方言の言語項が南部方言へ降りていくという例が多い.

この問題に対して,Millar は Samuels 流の機能主義的な立場から,"conservative radicalism" という解答を与えている.例として取り上げている言語変化は,3人称複数代名詞 they による古英語形 hīe の置換と,そこから玉突きに生じたと仮定されている,接続詞 though による þeah の置換,および指示詞 those による tho の置換だ.

The issue with ambiguity between the third person singular and plural forms was also sorted through the borrowing of Northern usage, although on this occasion through what had been an actual Norse borrowing (although it would be very unlikely that southern speakers would have been aware of the new form's provenance --- if they cared): they. Interestingly, the subject form came south earlier than the oblique them and possessive their. Chaucer, for instance, uses the first but not the other two, where he retains native <h> forms. This type of usage represents what I have termed conservative radicalism (Millar 2000; in particular pp. 63--4). Northern forms are employed to sort out issues in more prestigious dialects, but only in 'small homeopathic doses'. The problem (if that is the right word) is that the injection of linguistically radical material into a more conservative framework tends to encourage more radical importations. Thus them and their(s) entered written London dialect (and therefore Standard English) in the generation after Chaucer's death, possibly because hem was too close to him and hare to her. If the 'northern' forms had not been available, everyone would probably have 'soldiered on', however.

Moreover, the borrowing of they meant that the descendant of Old English þeah 'although' was often its homophone. Since both of these are function words, native speakers must have felt uncomfortable with using both, meaning that the northern (in origin Norse) conjunction though was brought into southern systems. This borrowing led to a further ambiguity, since the plural of that in southern England was tho, which was now often homophonous with though. A new plural --- those --- was therefore created. Samuels (1989a) demonstrates these problems can be traced back to northern England and were spread by 'capillary motion' to more southern areas. These changes are part of a much larger set, all of which suggest that northern influence, particularly at a subconscious or covert level, was always present on the edges of more southerly dialects and may have assumed a role as a 'fix' to sort out ambiguity created by change.

ここで Millar が Conservative radicalism の名のもとで解説している北部形が南部の体系に取り込まれていくメカニズムは,きわめて機能主義的といえるが,そのメカニズムが作用する前提として,方言接触 (dialect contact) と諸変異形 (variants) の共存があったという点が重要である.接触 (contact) の結果として形態の変異 (variation) の機会が生まれ,体系的調整 (systemic regulation) により,ある形態が採用されたのである.ここには「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1]) で紹介した言語変化の3機構 contact, variation, systemic regulation が出そろっている.Millar の conservative radicalism という考え方は,一見すると不可思議な北部から南部への言語変化の伝播という問題に,一貫した理論的な説明を与えているように思える.

they と though の変化に関する個別の話題としては,「#975. 3人称代名詞の斜格形ではあまり作用しなかった異化」 ([2011-12-28-1]) と「#713. "though" と "they" の同音異義衝突」 ([2011-04-10-1]) を参照.

なお,Millar (119--20) は,3人称女性単数代名詞 she による古英語 hēo の置換の問題にも conservative radicalism を同じように適用できると考えているようだ.she の問題については,「#792. she --- 最も頻度の高い語源不詳の語」 ([2011-06-28-1]), 「#793. she --- 現代イングランド方言における異形の分布」 ([2011-06-29-1]),「#827. she の語源説」 ([2011-08-02-1]),「#974. 3人称代名詞の主格形に作用した異化」([2011-12-27-1]) を参照.

・ Millar, Robert McColl. English Historical Sociolinguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2012.

2014-05-10 Sat

■ #1839. 言語の単純化とは何か [terminology][language_change][pidgin][creole][functionalism][functional_load][entropy][redundancy][simplification]

英語史は文法の単純化 (simplification) の歴史であると言われることがある.古英語から中英語にかけて複雑な屈折 (inflection) が摩耗し,文法性 (grammatical gender) が失われ,確かに言語が単純化したようにみえる.屈折の摩耗については,「#928. 屈折の neutralization と simplification」 ([2011-11-11-1]) で2種類の過程を区別する観点を導入した.

単純化という用語は,ピジン化やクレオール化を論じる文脈でも頻出する.ある言語がピジンやクレオールへ推移していく際に典型的に観察される文法変化は,単純化として特徴づけられる,と言われる.

しかし,言語における単純化という概念は非常にとらえにくい.言語の何をもって単純あるいは複雑とみなすかについて,言語学的に合意がないからである.語彙,文法,語用の部門によって単純・複雑の基準は(もしあるとしても)異なるだろうし,「#293. 言語の難易度は測れるか」 ([2010-02-14-1]) でも論じたように,各部門にどれだけの重みを与えるべきかという難問もある.また,機能主義的な立場から,ある言語の functional_load や entropy を計測することができたとしても,言語は元来余剰性 (redundancy) をもつものではなかったかという疑問も生じる.さらに,単純化とは言語変化の特徴をとらえるための科学的な用語ではなく,ある種の言語変化観と結びついた評価を含んだ用語ではないかという疑いもぬぐいきれない(関連して「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]) を参照).

ショダンソン (57) は,クレオール語にみられるといわれる,意味の不明確なこの「単純化」について,3つの考え方を紹介している.

(A) 「最小化」 ―― この仮説は,O・イエスペルセンによって作られた.イエスペルセンは,クレオール語のなかに,いかなる言語にとっても欠かせない特徴のみをそなえた最小の体系をみた.

(B) 「最適化」 ―― L・イエルムスレウの理論で,彼にとって「クレオール語における形態素の表現は最適状態にある」.

(C) 「中立化」 ―― この視点はリチャードソンによって提唱された.リチャードソンは,モーリシャス語の場合,はじめに存在していた諸言語の体系(フランス語,マダガスカル語,バントゥー語)があまりに異質であったために,体系の節減が起こったと考えた.

しかし,ショダンソンは,いずれの概念も曖昧であるとして「単純化」という術語そのものに疑問を呈している.フランス語をベースとするレユニオン・クレオール語からの具体的な例を用いた議論を引用しよう (57--58) .ショダンソンの議論は,本質をついていると思う.

単純化という概念そのものが自明ではない.たとえばレユニオン・クレオール語の mon zanfan 〔わたしのこども〕という表現は,フランス語で mon enfant 〔単数:わたしの子〕と mes enfants 〔複数:わたしの子供たち〕という二つの形に翻訳することができる.これをみて,レユニオン語は単数と複数とを区別しないから,フランス語より単純だといいたくなるかもしれないが,別の面からみれば,同じ理由から,クレオール語の表現はもっとあいまいだから,したがってより「単純」ではないともいえるだろう!実際,「単純」という語の意味は,「複合的ではない」とも,「明晰」「あいまいでない」ともいえるのである.しかし,上の例をさらによく調べるならば,レユニオン語は,はっきりさせる必要があるときは複数をちゃんと表わすことができることに気がつく.その時には mon bane zanfan (私の子供たち)のように〔bane という複数を表わす道具を用いて〕いう.だから,クレオール語とフランス語のちがいは,一部には,もっぱら話しことばであるクレオール語がコンテクストの要素に大きな場所をあたえていることによる.母親がしばらくの間こどもをお隣りさんにあずけるとき,vey mon zanfan! 〔うちの子をみてくださいね〕と頼んだとしよう.このときわざわざ,こどもが一人か複数かをはっきりさせる必要はない.他方で,口語フランス語では,複数をしめすには,たいていの場合,名詞の形態的標識ではなく,修飾語の標識によっている.だから,クレオール語で修飾語の体系を組み立てなおしたならば,それと同時に,数の表示にも手をつけることになるのである.しかし,これは別の過程から来るとばっちりにすぎない.

この数の問題についての逆説をすすめていくと,レユニオン・クレオール語は双数をもっているから,フランス語よりももっと複雑だということにもなろう.事実,レユニオン・クレオール語では,何でも二つで一つになっているもの(目,靴など)に対し,特別のめじるしがある.「私の〔二つの〕目」については,mon bane zyé ということはできず,mon dé zyé といわなければならない.同様に「私の〔一つの〕目」といいたいときは,mon koté d zyé という.koté d と dé は,双数用の特別のめじるしである.したがって,mon bane soulie は,何足かの靴を指すことしかできないのである.

このような事情があるから,「単純化」ということばは使わないにこしたことはない.この語には〔クレオール語を劣ったものとみる〕人種主義的なニュアンスがあるし,機能的,構造的に異なる言語を比較している以上,事柄を具体的に解明するには,あまりに精密を欠き,あいまいだからである.「再構造化」といったほうがずっといい.「再構造化」という語のほうがもっと中立的であるし,他の多くの用語(単純化,最小化,最適化)とことなり,明らかにしようとしている構造的なちがいの原因を,偏見の目で判断しないという利点がある.

上の最初の引用にあるイエスペルセンの言語観については「#1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観」 ([2014-01-19-1]) を,イエルムスレウについては「#1074. Hjelmslev の言理学」 ([2012-04-05-1]) を参照.

・ ロベール・ショダンソン 著,糟谷 啓介・田中 克彦 訳 『クレオール語』 白水社〈文庫クセジュ〉,2000年.

2014-04-17 Thu

■ #1816. drift 再訪 [drift][gvs][germanic][synthesis_to_analysis][language_change][speed_of_change][unidirectionality][causation][functionalism]

Millar (111--13) が,英語史における古くて新しい問題,drift (駆流)を再訪している(本ブログ内の関連する記事は,cat:drift を参照).

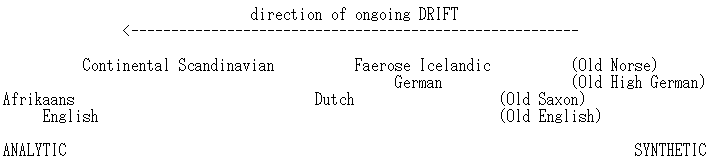

Sapir の唱えた drift は,英語なら英語という1言語の歴史における言語変化の一定方向性を指すものだったが,後に drift の概念は拡張され,関連する複数の言語に共通してみられる言語変化の潮流をも指すようになった.これによって,英語の drift は相対化され,ゲルマン諸語にみられる drifts の比較,とりわけ drifts の速度の比較が問題とされるようになった.Millar (112) も,このゲルマン諸語という視点から,英語史における drift の問題を再訪している.

A number of scholars . . . take Sapir's ideas further, suggesting that drift can be employed to explain why related languages continue to act in a similar manner after they have ceased to be part of a dialect continuum. Thus it is striking . . . that a very similar series of sound changes --- the Great Vowel Shift --- took place in almost all West Germanic varieties in the late medieval and early modern periods. While some of the details of these changes differ from language to language, the general tendency for lower vowels to rise and high vowels to diphthongise is found in a range of languages --- English, Dutch and German --- where immediate influence along a geographical continuum is unlikely. Some linguists would suggest that there was a 'weakness' in these languages which was inherited from the ancestral variety and which, at the right point, was triggered by societal forces --- in this case, the rise of a lower middle class as a major economic and eventually political force in urbanising societies.

これを書いている Millar 自身が,最後の文の主語 "Some linguists" のなかの1人である.Samuels 流の機能主義的な観点に,社会言語学的な要因を考え合わせて,英語の drift を体現する個々の言語変化の原因を探ろうという立場だ.Sapir の drift = "mystical" というとらえ方を退け,できる限り合理的に説明しようとする立場でもある.私もこの立場に賛成であり,とりわけ社会言語学的な要因の "trigger" 機能に関心を寄せている.関連して,「#927. ゲルマン語の屈折の衰退と地政学」 ([2011-11-10-1]) や「#1224. 英語,デンマーク語,アフリカーンス語に共通してみられる言語接触の効果」 ([2012-09-02-1]) も参照されたい.

ゲルマン諸語の比較という点については,Millar (113) は,drift の進行の程度を模式的に示した図を与えている.以下に少し改変した図を示そう(かっこに囲まれた言語は,古い段階での言語を表わす).

この図は,「#191. 古英語,中英語,近代英語は互いにどれくらい異なるか」 ([2009-11-04-1]) で示した Lass によるゲルマン諸語の「古さ」 (archaism) の数直線を別の形で表わしたものとも解釈できる.その場合,drift の進行度と言語的な「モダンさ」が比例の関係にあるという読みになる.

この図では,English や Afrikaans が ANALYTIC の極に位置しているが,これは DRIFT が完了したということを意味するわけではない.現代英語でも,DRIFT の継続を感じさせる言語変化は進行中である.

・ Millar, Robert McColl. English Historical Sociolinguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2012.

2014-04-12 Sat

■ #1811. "The later a change begins, the sharper its slope becomes." [lexical_diffusion][speed_of_change][language_change][entropy][do-periphrasis][schedule_of_language_change]

昨日の記事「#1810. 変異のエントロピー」 ([2014-04-11-1]) の最後で,「遅く始まった変化は急速に進行するという,言語変化にしばしば見られるパターン」に言及した.これは必ずしも一般的に知られていることではないので,補足説明しておきたい.実はこのパターンが言語変化にどの程度よく見られることなのかは詳しくわかっておらず,この問題は私の数年来の研究テーマともなっている.

言語変化のなかには,進行速度が slow-quick-quick-slow と変化する語彙拡散 (lexical_diffusion) と呼ばれるタイプのものがある.語彙拡散の研究によると,変化を開始するタイミングは語によって異なり,比較的早期に変化に呑み込まれるものから,比較的遅くまで変化に抵抗するものまで様々である.Ogura や Ogura and Wang の指摘で興味深いのは,このタイミングの早い遅いによって,開始後の変化の進行速度も異なる可能性があるということだ.早期に開始したもの (leaders) はゆっくりと進む傾向があるのに対して,遅れて開始したもの (laggers) は急ピッチで進む傾向があるという.譬えは悪いが,早起きしたけれども歩くのが遅いので遅刻するタイプと,寝坊したけれども慌てて走るので間に合うタイプといったところか.標記に挙げた "the later a change begins, the sharper its slope becomes" は,Ogura (78) からの引用である.

私自身,初期中英語諸方言における複数形の -s の拡大に関する2010年の論文で,この傾向を明らかにした.その論文から,Ogura と Ogura and Wang へ言及している部分など2箇所を引用する.

In their series of studies on Lexical Diffusion, Ogura and Wang discussed whether leaders and laggers of a change are any different from one another in terms of the speed of diffusion. In case studies such as the development of periphrastic do and the development of -s in the third person singular present indicative, they proposed that the later the change, the more items change and the faster they change . . . . (12)

. . . the laggers catching up with the leaders in SWM C13b and in SEM C13b concurs with the recent proposition of Lexical Diffusion that "the later a change begins, the sharper its slope becomes." (14)

変化に参与する各語をそれぞれS字曲線として表わすと,例えば以下のような非平行的なS字曲線の集合となる.

ここで昨日の相対エントロピーの話に戻ろう.上のようなグラフを,Y軸を相対エントロピーの値として描き直せば,スタートは早いが進みは遅い語は,長い裾を引く富士山型の線を,スタートは遅いが進みは速い語は,尖ったマッターホルン型の線を描くことになるだろう.

語彙拡散のS字曲線,エントロピー,[2013-09-09-1]の記事で触れた「#1596. 分極の仮説」などは互いに何らかの関係があると見られ,言語変化のスピードやスケジュールという一般的な問題に迫るヒントを与えてくれるだろう.

・ Ogura, Mieko. "The Development of Periphrastic Do in English: A Case of Lexical Diffusion in Syntax." Diachronica 10 (1993): 51--85.

・ Ogura, Mieko and William S-Y. Wang. "Snowball Effect in Lexical Diffusion: The Development of -s in the Third Person Singular Present Indicative in English." English Historical Linguistics 1994. Papers from the 8th International Conference on English Historical Linguistics. Ed. Derek Britton. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1994. 119--41.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi. "Leaders and Laggers of Language Change: Nominal Plural Forms in -s in Early Middle English." Journal of the Institute of Cultural Science (The 30th Anniversary Issue II) 68 (2010): 1--17.

2014-04-11 Fri

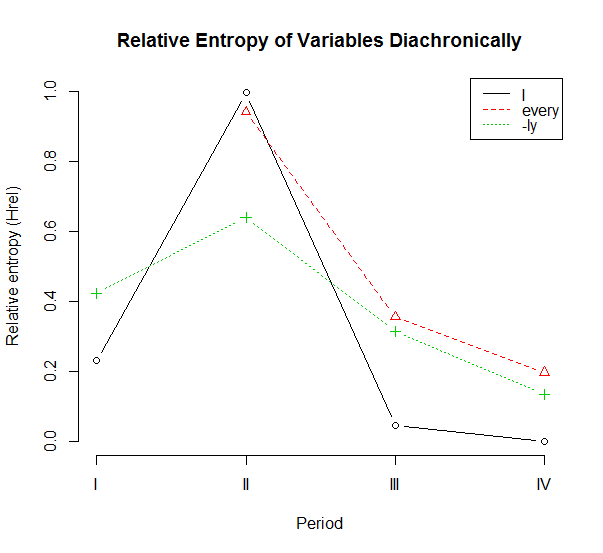

■ #1810. 変異のエントロピー [statistics][entropy][variation][consonant][speed_of_change][language_change][schedule_of_language_change][-ly]

昨今,エントロピー (entropy) というキーワードをよく聞くようになったが,言語との関連で,この概念が話題にされることはあまりない.本ブログでは,「#838. 言語体系とエントロピー」 ([2011-08-13-1]) をはじめとして,##838,1089,1090,1587,1693 の各記事でこの用語に触れてきたが,まだ具体的な問題に適用したことはなかった.

エントロピーとは,体系としての乱雑さの度合いを示す指標である.データがいかに一様に散らばっているかを表わす尺度と言い換えてもよい.言語への応用は,Gries (112) が少し触れている.

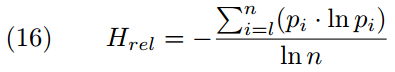

A simple measure for categorical data is relative entropy Hrel. Hrel is 1 when the levels of the relevant categorical variable are all equally frequent, and it is 0 when all data points have the same variable level. For categorical variables with n levels, Hrel is computed as shown in formula (16), in which pi corresponds to the frequency in percent of the i-th level of the variable:

Gries は,300個の名詞句における冠詞の分布という例を挙げている.無冠詞164例,不定冠詞33例,定冠詞103例という内訳だった場合,Hrel = 0.8556091 となり,かなり不均質な分布を示すことになる.

ほかに散らばり具合が問題になるケースはいろいろと考えることができる.例えば,注目語句の出現頻度が,テキスト(のジャンル)に応じて一様か否かを測るということもできるだろう.

また,ある語に異形態や異綴字が認められる場合に,それぞれの変異形 (variants) の分布が均一か不均一かを計測することなどもできる.そのような変異の相対エントロピーが同時代の異なるテキスト(ジャンル)の間でどのくらい異なるのか,あるいは歴史的な関心からは,異なる時代のテキスト(ジャンル)の間でどのくらい異なるのかを,客観的に確かめることができるだろう.標準化その他の過程により,その変異が1つの形へ収斂してゆく場合,エントロピーが減少することになる.

具体的に考えるために,「#1773. ich, everich, -lich から語尾の ch が消えた時期」 ([2014-03-05-1]) で取り上げた,語尾の ch の脱落のデータを参照しよう.先の記事で Schlüter による集計結果の表を掲げたが,今回は,音声環境 (before V, before <h>, before C) の区別はせず,単純に ME II--ME IV の各時代に現れた変異形のトークン数のみを考慮に入れることにする.各変異形の各時代の Hrel を計算した結果の表を下に示す.

| I | 1150--1250 (ME I) | 1250--1350 (ME II) | 1350--1420 (ME III) | 1420--1500 (ME IV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ich | 853 | 589 | 7 | 0 |

| I | 33 | 503 | 1397 | 2612 |

| Hrel | 0.2295 | 0.9955 | 0.04531 | 0.0000 |

| EVERY | 1150--1250 (ME I) | 1250--1350 (ME II) | 1350--1420 (ME III) | 1420--1500 (ME IV) |

| everich | - | 12 | 10 | 9 |

| everiche | - | 12 | 3 | 0 |

| every | - | 5 | 112 | 152 |

| Hrel | - | 0.9406 | 0.3550 | 0.1962 |

| -LY | 1150--1250 (ME I) | 1250--1350 (ME II) | 1350--1420 (ME III) | 1420--1500 (ME IV) |

| -lich | 106 | 33 | 31 | 3 |

| -''liche' | 689 | 168 | 70 | 44 |

| -ly | 12 | 19 | 1088 | 1444 |

| Hrel | 0.4225 | 0.6390 | 0.3123 | 0.1342 |

これの をプロットすると,次のようになる.

1人称単数代名詞主格 I の変異は,集束→発散→集束と推移しており,不安定期 II の突出が目立つ.安定していた体系が急激に乱され,そしてすぐに回復したという推移だ.第I期のデータを欠く every の変異は,I ほどではないものの,同じようにIIからIIIの時期にかけて急激な下落を示す.-ly の変異も,より緩やかではあるが,同時期に同様の下降を表わす.

Schlüter は,ich, everich, -lich の順で語尾の ch が脱落し,変異の収斂に向かっていったと評価しているが,これは第II期以降のエントロピーの減少率のことを指していると解釈できる.しかし,第I期からの推移も考慮に入れると,I の発散の開始は -ly の発散よりも後のようである.これは,早く始まった変化はゆっくりと進行するのに対し,遅く始まった変化は急速に進行するという,言語変化にしばしば見られるパターンを示唆する.エントロピー曲線の形状でいえば,前者は裾の長い富士山型,後者は先のとがったマッターホルン型ということになる.エントロピーという指標を用いて,言語変化のスピードについて何か一般化できることがあるかもしれない.

・ Gries, Stefan Th. Statistics for Linguistics with R: A Practical Introduction. Berlin: Mouton, 2009.

・ Schlüter, Julia. "Weak Segments and Syllable Structure in ME." Phonological Weakness in English: From Old to Present-Day English. Ed. Donka Minkova. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. 199--236.

2014-01-19 Sun

■ #1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観 [language_change][teleology][evolution][unidirectionality][drift][history_of_linguistics][artificial_language][language_myth]

英語史の授業で英語が経てきた言語変化を概説すると,「言語はどんどん便利な方向へ変化してきている」という反応を示す学生がことのほか多い.これは,「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]) の (2) に挙げた「言語変化はより効率的な状態への緩慢な進歩である」と同じものであり,言語進歩観とでも呼ぶべきものかもしれない.しかし,その記事でも述べたとおり,言語変化は進歩でも堕落でもないというのが現代の言語学者の大方の見解である.ところが,かつては,著名な言語学者のなかにも,言語進歩観を公然と唱える者がいた.デンマークの英語学者 Otto Jespersen (1860--1943) もその1人である.

. . . in all those instances in which we are able to examine the history of any language for a sufficient length of time, we find that languages have a progressive tendency. But if languages progress towards greater perfection, it is not in a bee-line, nor are all the changes we witness to be considered steps in the right direction. The only thing I maintain is that the sum total of these changes, when we compare a remote period with the present time, shows a surplus of progressive over retrogressive or indifferent changes, so that the structure of modern languages is nearer perfection than that of ancient languages, if we take them as wholes instead of picking out at random some one or other more or less significant detail. And of course it must not be imagined that progress has been achieved through deliberate acts of men conscious that they were improving their mother-tongue. On the contrary, many a step in advance has at first been a slip or even a blunder, and, as in other fields of human activity, good results have only been won after a good deal of bungling and 'muddling along.' (326)

. . . we cannot be blind to the fact that modern languages as wholes are more practical than ancient ones, and that the latter present so many more anomalies and irregularities than our present-day languages that we may feel inclined, if not to apply to them Shakespeare's line, "Misshapen chaos of well-seeming forms," yet to think that the development has been from something nearer chaos to something nearer kosmos. (366)

Jespersen がどのようにして言語進歩観をもつに至ったのか.ムーナン (84--85) は,Jespersen が1928年に Novial という補助言語を作り出した背景を分析し,次のように評している(Novial については「#958. 19世紀後半から続々と出現した人工言語」 ([2011-12-11-1]) を参照).

彼がそこへたどり着いたのはほかの人の場合よりもいっそう,彼の論理好みのせいであり,また,彼のなかにもっとも古くから,もっとも深く根をおろしていた理論の一つのせいであった.その理論というのは,相互理解の効率を形態の経済性と比較してみればよい,という考えかたである.それにつづくのは,平均的には,任意の一言語についてみてもありとあらゆる言語についてみても,この点から見ると,正の向きの変化の総和が不の向きの総和より勝っているものだ,という考えかたである――そして彼は,もっとも普遍的に確認されていると称するそのような「進歩」の例として次のようなものを列挙している.すなわち,音楽的アクセントが次第に単純化すること,記号表現部〔能記〕の短縮,分析的つまり非屈折的構造の発達,統辞の自由化,アナロジーによる形態の規則化,語の具体的な色彩感を犠牲にした正確性と抽象性の増大である.(『言語の進歩,特に英語を照合して』) マルティネがみごとに見てとったことだが,今日のわれわれにはこの著者のなかにあるユートピア志向のしるしとも見えそうなこの特徴が,実は反対に,ドイツの比較文法によって広められていた神話に対する当時としては力いっぱいの戦いだったのだと考えて見ると,実に具体的に納得がいく.戦いの相手というのは,諸言語の完全な黄金時期はきまってそれらの前史時代の頂点に位置しており,それらの歴史はつねに形態と構造の頽廃史である,という神話だ.(「語の研究」)

つまり,Jespersen は,当時(そして少なからず現在も)はやっていた「言語変化は完全な状態からの緩慢な堕落である」とする言語堕落観に対抗して,言語進歩観を打ち出したということになる.言語学史的にも非常に明快な Jespersen 評ではないだろうか.

先にも述べたように,Jespersen 流の言語進歩観は,現在の言語学では一般的に受け入れられていない.これについて,「#448. Vendryes 曰く「言語変化は進歩ではない」」 ([2010-07-19-1]) 及び「#1382. 「言語変化はただ変化である」」 ([2013-02-07-1]) を参照.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Language: Its Nature, Development, and Origin. 1922. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ ジョルジュ・ムーナン著,佐藤 信夫訳 『二十世紀の言語学』 白水社,2001年.

2014-01-13 Mon

■ #1722. Pisani 曰く「言語は大河である」 [wave_theory][family_tree][language_change][historiography][neolinguistics]

「#1578. 言語は何に喩えられてきたか」 ([2013-08-22-1]) や「#1579. 「言語は植物である」の比喩」 ([2013-08-23-1]) の記事ほかで,「言語は○○である」の比喩を考察した.言語を川に喩える謂いは「#449. Vendryes 曰く「言語は川である」」 ([2010-07-20-1]) で紹介したが,Vendryes とは異なる意味で言語を川(というよりは大河)に喩えている言語学者がいるので紹介したい.昨日の記事「#1721. 2つの言語の類縁性とは何か?」 ([2014-01-12-1]) で導入した Pisani である.

Pisani は,系統樹モデルでいう継承と波状モデルでいう借用とのあいだに有意義な区別を認めず,両者を言語的革新 (créations) として統合しようとした.この区別をとっぱらうことで木と波のイメージをも統合し,新たなイメージとして大河 (fleuve) が浮かんできた.支流どうしが複雑に合流と分岐を繰り返し,時間に沿ってひたすら流れ続ける大河である.

À vrai dire, le terme de parenté, avec les images qu'il reveille, porte à une vision erronée comme l'autre, qui y est connexée, de l'arbre généalogique. Une image beaucoup plus correspondante à la réalité des faits linguistiques pourrait être suggérée par un système hydrique compliqué: un fleuve qui rassemble l'eau de torrents et ruisseaux, à un certain moment se mêle avec un autre fleuve, puis se bifurque, chacun des deux bras continue à son tour à se mêler avec d'autres cours d'eau, peut-être aussi avec un ou plusieurs dérivés de son compagnon, il se forme des lacs dont de nouveaux fleuves se départent, et ainsi de suite. (13)

この大河の部分部分は○○水系や○○河と呼ばれる得るが,○○水系や○○河の始まりがどこなのか,別の水系や河との境はどこなのかという問いに答えることはできない.同じことが大河に喩えられた言語にもいえる.言語という複雑な一大水系のなかで,どの部分がゲルマン系と呼ばれるのか,どの部分が英語と呼ばれるのかを答えることはできない.せいぜいできることといえば,およその部分に便宜的にそれらのラベルを貼ることぐらいだろう.そのように考えると,英語史記述というのも,迷路のような支流群のなかから,ある特定の川筋を鉛筆でたどり,「はい,この線が英語(史)ですよ」と言っているに等しいことになる.

・ Pisani, Vittore. "Parenté linguistique." Lingua 3 (1952): 3--16.

2014-01-12 Sun

■ #1721. 2つの言語の類縁性とは何か? [wave_theory][family_tree][language_change][romancisation]

2つの言語のあいだにみられる類縁性とか血縁関係とか言われるものは,いったい何を指しているのだろうか.2言語間の関係を把握するモデルとして伝統的に系統樹モデル (family_tree) と波状モデル (wave_theory) が提起されてきたが,この2つのモデルの関係自体が議論の対象とされており,いまだに両者を総合したモデルの模索が続いている.##369,371,999,1118,1236,1302,1303,1313,1314 ほか,比較的最近では「#1236. 木と波」 ([2012-09-14-1]) や「#1397. 断続平衡モデル」 ([2013-02-22-1]) でこの問題に関連する話題を扱ってきたが,今回はイタリアの言語学者 Pisani の論文を参照し,再考してみよう.

Pisani にとって,2つの言語のあいだの類縁性 (parenté) とは,共通している言語的要素の多さによって決まる.

. . . à chaque moment nous nous trouvons en présence d'une langue nouvelle constituée par la confluence et le mélange toujours divers d'éléments de provenance diverse dans les innombrables créations des individus parlants; et parenté linguistique n'est autre chose que la communauté d'éléments que l'on constate ainsi entre langue et langue. (14)

これは単純な言い方のようだが,系統樹モデルにも波状モデルにもあえて言及しない,意図的な言い回しなのである.系統樹モデルに従えば,ある言語項目は,それに先立つ段階の対応する言語項目から歴史的に発展したものとされる.一方で,波状モデルに従えば,ある言語項目は,隣接する言語の対応する言語項目を借りたものであるとされる.いずれの場合にも,問題の言語項目は既存の対応する言語項目に何らかの意味で「似ている」には違いなく,どちらのモデルによる場合のほうがより「似ている」のかを一般的に決めることはできない.それならば,「似ている」度合いを測る上で,系統樹的な関係をより重視してよい理由もなければ,逆に波状的な関係を優遇してよい理由もないということになる.

英語の場合を考えてみると,伝統的には系統樹モデルに従ってゲルマン語派に属するとされるが,特に語彙のロマンス語化が中英語期以降に激しかったので,波状モデルに従って,イタリック語派にも片足を踏み入れているとも言われる.つまり,この広く行き渡った見解は,原則としては系統樹モデルの考え方を優勢とみなして,第一義的にゲルマン語派に属すると唱え,その後に波状モデルの考え方を導入して,第二義的にイタリック的でもあると唱えているのである.英語の場合には,比較的豊富な文献が残っており,その歴史も借用の時間的な前後関係もある程度はわかっているので,上記の優先順位でとらえるのが自然であるという見方が現れやすいが,歴史的な情報がほとんど得られないある言語において,それと何らかの程度で似ている言語との類縁性を測る場合には,系統樹モデルを前提とすることもできないし,波状モデルを前提とすることもできない(「#371. 系統と影響は必ずしも峻別できない」 ([2010-05-03-1]) を参照).目の前にあるのは,類似性を示す言語項目のみである.

Pisani は,Schuchardt にしたがって親子関係と借用関係のあいだに意味ある区別を認めず,すべての言語は混合言語 (Mischsprachen) であるという立場に立って,2言語間の類縁性を定義しようとしたのである(関連して,「#1069. フォスラー学派,新言語学派,柳田 --- 話者個人の心理を重んじる言語観」 ([2012-03-31-1]) も参照).2言語間の言語項目の類似性の理由は,親子関係かもしれないし借用関係かもしれないが,いずれにせよそれぞれの言語において,過去のある時点に何らかの言語的革新が生じ,互いが似通ってきたり離れてきたりしてきたに違いない.重要なのは言語的革新のみであり,Pisani は「それぞれが固有の展開をとげる個々別々の改新しか進化のなかには認めなかった」のである(ペロ,p. 89).

・ Pisani, Vittore. "Parenté linguistique." Lingua 3 (1952): 3--16.

・ ジャン・ペロ 著,高塚 洋太郎・内海 利朗・滝沢 隆幸・矢島 猷三 訳 『言語学』 白水社〈文庫クセジュ〉,1972年.

2013-09-13 Fri

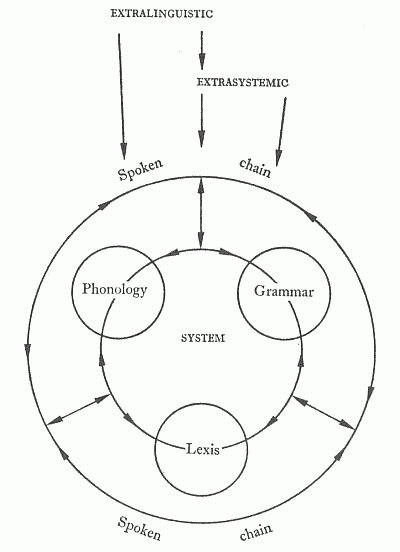

■ #1600. Samuels の言語変化モデル [language_change][causation]

言語変化にかかわる諸要因をモデル化する試みは様々になされてきたが,大づかみの見取り図を示してくれたものとして,Samuels のモデル (141) を紹介したい.筆者は,このモデルのすっきりとした見通しのよさに,いたく感銘を受けたものである.

言語体系 (system) は,文法 (grammar) ,音韻 (phonology) ,語彙 (lexis) の3部門から成り立っており,それぞれは互いに強く結びついている. 構造言語学でいうところの,"système où tout se tient" である.この体系は,3部門の堅いスクラムによりがっちりと組まれているものの,水も通さぬ密室というわけではない.体系は,それを基盤として現実に生み出される発話 (spoken chain) という現実の言語使用により,それ自身が常に変容にさらされている.その発話はまた,別の言語体系 (extrasystemic) からの圧力を受け,その圧力を間接的に文法,音韻,語彙へと伝え,体系を変容させる.さらに,文化や歴史のような種々の言語外的な (extralinguistic) な要因により,いっそう間接的にではあるが,中央の言語体系に影響を及ぼす.

Samuels の上の図は,非常にあらあらの図ではあるが,言語(変化)の1つの参照すべきモデルを提供している.ここには,生成文法で想定されている component や faculty という概念も含まれているし,ソシュールの langue と parole の対比も system と spoken chain の対比として表現されている.同心円の内部で作用している intrasystemic な要因と外部で作用している extrasystemic な要因とも図に反映されているし,以上のすべてを含めた intralinguistic な次元と,それ以外の extralinguistic な次元とも区別している.

この図は,dynamic ではあるが synchronic である.diachronic な軸を加えようとすれば,この図の面に直交して前後に伸びるチューブのようなイメージになるだろう.Samuels も当面そこまで踏み込むことはしていない.

言語変化の原因・要因については本ブログでも数々議論してきたが,とりわけ一般的な問題として取り上げた記事へのリンクを張っておきたい.

・ 「#442. 言語変化の原因」 ([2010-07-13-1])

・ 「#1476. Fennell による言語変化の原因」 ([2013-05-12-1])

・ 「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1])

・ 「#443. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か?」 ([2010-07-14-1])

・ 「#1582. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (2)」 ([2013-08-26-1])

・ 「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1])

・ 「#1123. 言語変化の原因と歴史言語学」 ([2012-05-24-1])

・ 「#1282. コセリウによる3種類の異なる言語変化の原因」 ([2012-10-30-1])

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

2013-09-09 Mon

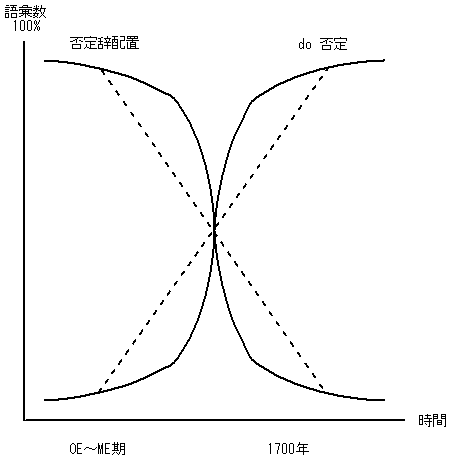

■ #1596. 分極の仮説 [lexical_diffusion][language_change][speed_of_change][generative_grammar][negative][syntax][do-periphrasis][schedule_of_language_change]

標題は英語で "polarization hypothesis" と呼ばれる.児馬先生の著書で初めて知ったものである.昨日の記事「#1572. なぜ言語変化はS字曲線を描くと考えられるのか」 ([2013-08-16-1]) および「#1569. 語彙拡散のS字曲線への批判 (2)」 ([2013-08-13-1]) などで言語変化の進行パターンについて議論してきたが,S字曲線と分極の仮説は親和性が高い.

分極の仮説は,生成文法やそれに基づく言語習得の枠組みからみた言語変化の進行に関する仮説である.それによると,文法規則には大規則 (major rule) と小規則 (minor rule) が区別されるという.大規則は,ある範疇の大部分の項目について適用される規則であり,少数の例外的な項目(典型的には語彙項目)には例外であるという印がつけられており,個別に処理される.一方,小規則は,少数の印をつけられた項目にのみ適用される規則であり,それ以外の大多数の項目には適用されない.両者の差異を際立たせて言い換えれば,大規則には原則として適用されるが少数の適用されない例外があり,小規則には原則として適用されないが少数の適用される例外がある,ということになる.共通点は,例外項目の数が少ないことである.分極の仮説が予想するのは,言語の規則は例外項目の少ない大規則か小規則のいずれかであり,例外項目の多い「中規則」はありえないということだ.習得の観点からも,例外のあまりに多い中規則(もはや規則と呼べないかもしれない)が非効率的であることは明らかであり,分極の仮説に合理性はある.

分極の仮説と言語変化との関係を示すのに,迂言的 do ( do-periphrasis ) による否定構造の発達を挙げよう.「#486. 迂言的 do の発達」 ([2010-08-26-1]) ほかの記事で触れた話題だが,古英語や中英語では否定構文を作るには定動詞の後に not などの否定辞を置くだけで済んだ(否定辞配置,neg-placement)が,初期近代英語で do による否定構造が発達してきた.do 否定への移行の過程についてよく知られているのは,know, doubt, care など少数の動詞はこの移行に対して最後まで抵抗し,I know not などの構造を続けていたことである.

さて,古英語や中英語では否定辞配置が大規則だったが,近代英語では do 否定に置き換えられ,一部の動詞を例外としてもつ小規則へと変わった.do 否定の観点からみれば,発達し始めた16世紀には,少数の動詞が関与するにすぎない小規則だったが,17世紀後半には少数の例外をもつ大規則へと変わった.否定辞配置の衰退と do 否定の発達をグラフに描くと,中間段階に著しく急速な変化を示す(逆)S字曲線となる.

語彙拡散と分極の仮説は,理論の出所がまるで異なるにもかかわらず,S字曲線という点で一致を見るというのがおもしろい.

合わせて,分極の仮説の関連論文として園田の「分極の仮説と助動詞doの発達の一側面」を読んだ.園田は,分極の仮説を,生成理論の応用として通時的な問題を扱う際の補助理論と位置づけている.

・ 児馬 修 『ファンダメンタル英語史』 ひつじ書房,1996年.111--12頁.

・ 園田 勝英 「分極の仮説と助動詞doの発達の一側面」『The Northern Review (北海道大学)』,第12巻,1984年,47--57頁.

2013-08-29 Thu

■ #1585. 閉鎖的な共同体の言語は複雑性を増すか [suppletion][social_network][sociolinguistics][language_change][contact][accommodation_theory][language_change]

Ross (179) によると,言語共同体を開放・閉鎖の度合いと内部的な絆の強さにより分類すると,(1) closed and tightknit, (2) open and tightknit, (3) open and tightloose の3つに分けられる(なお,closed and tightloose の組み合わせは想像しにくいので省く).(1) のような閉ざされた狭い言語共同体では,他の言語共同体との接触が最小限であるために,共時的にも通時的にも言語の様相が特異であることが多い.

閉鎖性の強い共同体の言語の代表として,しばしば Icelandic が取り上げられる.本ブログでも,「#430. 言語変化を阻害する要因」 ([2010-07-01-1]), 「#903. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語」 ([2011-10-17-1]), 「#927. ゲルマン語の屈折の衰退と地政学」 ([2011-11-10-1]) などで話題にしてきた.Icelandic はゲルマン諸語のなかでも古い言語項目をよく保っているといわれる.social_network の理論によると,アイスランドのような,成員どうしが強い絆で結ばれている,閉鎖された共同体では,言語変化が生じにくく保守的な言語を残す傾向があるとされる.しかし,そのような共同体でも完全に閉鎖されているわけではないし,言語変化が皆無なわけではない.

では,比較的閉鎖された共同体に起こる言語変化とはどのようなものか.Papua New Guinea 島嶼部の諸言語の研究者たちによると,閉鎖された共同体では,言語変化は複雑化する方向に,また周辺の諸言語との差を際立たせる方向に生じることが多いという (Ross 181) .具体的には異形態 (allomorphy) や補充法 (suppletion) の増加などにより言語の不規則性が増し,部外者にとって理解することが難しくなる.そして,そのような不規則性は,かえって共同体内の絆を強める方向に作用する.このことは「#1482. なぜ go の過去形が went になるか (2)」 ([2013-05-18-1]) で引き合いに出した accommodation_theory の考え方とも一致するだろう.補充法の問題への切り口として注目したい.

閉鎖された共同体の言語における複雑化の過程は,Thurston という学者により "esoterogeny" と名付けられている.この過程に関して,Ross (182) の問題提起の一節を引用しよう.

In a sense, these processes, which Thurston labels 'esoterogeny', are hardly a form of contact-induced change, but rather its converse, a reaction against other lects. However, as they are conceived by Thurston their prerequisite is at least minimal contact with another community speaking a related lect from which speakers of the esoteric lect are seeking to distance themselves. Thurston's conceptions raises an interesting question: if a community is small, and closed simply because it is totally isolated from other communities, will its lect accumulate complexities anyway, or is the accumulation of complexity really spurred on by the presence of another community to react against? I am not sure of the answer to this question.

"esoterogeny" の仮説が含意するのは,逆のケース,すなわち開かれた共同体では,言語変化はむしろ単純化する方向に生じるということだ.関連して,古英語と古ノルド語の接触による言語の単純化について「#928. 屈折の neutralization と simplification」 ([2011-11-11-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Ross, Malcolm. "Diagnosing Prehistoric Language Contact." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 174--98.

2013-08-29 Thu

■ #1585. 閉鎖的な共同体の言語は複雑性を増すか [suppletion][social_network][sociolinguistics][language_change][contact][accommodation_theory][language_change]

Ross (179) によると,言語共同体を開放・閉鎖の度合いと内部的な絆の強さにより分類すると,(1) closed and tightknit, (2) open and tightknit, (3) open and tightloose の3つに分けられる(なお,closed and tightloose の組み合わせは想像しにくいので省く).(1) のような閉ざされた狭い言語共同体では,他の言語共同体との接触が最小限であるために,共時的にも通時的にも言語の様相が特異であることが多い.

閉鎖性の強い共同体の言語の代表として,しばしば Icelandic が取り上げられる.本ブログでも,「#430. 言語変化を阻害する要因」 ([2010-07-01-1]), 「#903. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語」 ([2011-10-17-1]), 「#927. ゲルマン語の屈折の衰退と地政学」 ([2011-11-10-1]) などで話題にしてきた.Icelandic はゲルマン諸語のなかでも古い言語項目をよく保っているといわれる.social_network の理論によると,アイスランドのような,成員どうしが強い絆で結ばれている,閉鎖された共同体では,言語変化が生じにくく保守的な言語を残す傾向があるとされる.しかし,そのような共同体でも完全に閉鎖されているわけではないし,言語変化が皆無なわけではない.

では,比較的閉鎖された共同体に起こる言語変化とはどのようなものか.Papua New Guinea 島嶼部の諸言語の研究者たちによると,閉鎖された共同体では,言語変化は複雑化する方向に,また周辺の諸言語との差を際立たせる方向に生じることが多いという (Ross 181) .具体的には異形態 (allomorphy) や補充法 (suppletion) の増加などにより言語の不規則性が増し,部外者にとって理解することが難しくなる.そして,そのような不規則性は,かえって共同体内の絆を強める方向に作用する.このことは「#1482. なぜ go の過去形が went になるか (2)」 ([2013-05-18-1]) で引き合いに出した accommodation_theory の考え方とも一致するだろう.補充法の問題への切り口として注目したい.

閉鎖された共同体の言語における複雑化の過程は,Thurston という学者により "esoterogeny" と名付けられている.この過程に関して,Ross (182) の問題提起の一節を引用しよう.

In a sense, these processes, which Thurston labels 'esoterogeny', are hardly a form of contact-induced change, but rather its converse, a reaction against other lects. However, as they are conceived by Thurston their prerequisite is at least minimal contact with another community speaking a related lect from which speakers of the esoteric lect are seeking to distance themselves. Thurston's conceptions raises an interesting question: if a community is small, and closed simply because it is totally isolated from other communities, will its lect accumulate complexities anyway, or is the accumulation of complexity really spurred on by the presence of another community to react against? I am not sure of the answer to this question.

"esoterogeny" の仮説が含意するのは,逆のケース,すなわち開かれた共同体では,言語変化はむしろ単純化する方向に生じるということだ.関連して,古英語と古ノルド語の接触による言語の単純化について「#928. 屈折の neutralization と simplification」 ([2011-11-11-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Ross, Malcolm. "Diagnosing Prehistoric Language Contact." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 174--98.

2013-08-28 Wed

■ #1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3) [causation][language_change]

[2010-07-14-1]と[2013-08-26-1]に引き続き,言語変化の説明原理としての endogeny と exogeny (contact-based) の問題を取り上げる.この論争は,endogeny を支持する保守派と exogeny の重要性を説く革新派の間で繰り広げられている.前者は Lass ([2013-08-26-1]) や Martinet (「#1015. 社会の変化と言語の変化の因果関係は追究できるか?」 [2012-02-06-1]) などが代表的な論客であり,後者には Milroy ([2013-08-26-1]) や Thomason and Kaufman などの論客がいる.

exogeny 支持派の多くは,ある言語変化が内的な要因によってうまく説明されるとしても,それゆえに外的な要因は関与していないと結論づけることはできないと主張する.また,多くの場合,内的な要因と外的な要因は一緒になって作用していると考える必要があり,言語変化論は "multiple causation" を前提とすべきだと説く.まずは,Thomason から3点を引用しよう.

Many linguistic changes have two or more causes, both external and internal ones; it often happens that one of the several causes of a linguistic change arises out of a particular contact situation. (62)

It clearly is not justified, for instance, to assume that you can only argue successfully for a contact origin if you fail to find any plausible internal motivation for a particular change. One reason is that the goal is always to find the best historical explanation for a change, and a good solid contact explanation is preferable to a weak internal one; another reason is that the possibility of multiple causation should always be considered and, as we saw above, it often happens that an internal motivation combines with an external motivation to produce a change. (91)

Yet another unjustified assumption is that contact-induced change should not be proposed as an explanation if a similar or identical change happened elsewhere too, without any contact or at least without the same contact situation. (92)

さらに,ケルト語の英語への影響の論客 Filppula より,同趣旨の一節を引用しよう.

Disagreements as to what weight each of the proposed methodological principles should be assigned in a given case are bound to remain part of the scholarly discourse, but certain things seem to me uncontroversial. First, as Lass (1997: 200--1) argues, apparent similarity, i.e. a mere formal parallel, cannot serve as proof of contact influence --- neither can it prove something to be of endogenous origin . . . . Before jumping to conclusions it is always necessary to examine the earlier history and the full syntactic, semantic and functional range of the features at issue, and also search for every possible kind of extra-linguistic evidence such as the extent of bilingualism in the speech communities involved, the chronological priority of rival sources, the geographical or areal distribution of the feature(s) at issue, demographic phenomena, etc. Secondly --- again in line with Lass's thinking (see, e.g., Lass 1997: 208) --- it is true to say that, from the point of view of the actual research, there is always a greater amount of homework in store for those who want to find conclusive evidence for contact influence than for those arguing for endogeny. On the other hand, even if endogeny is hard to rule out, as was shown by the examples discussed above, it does not follow that there would be no room for contact-based explanations or for those based on an interaction of factors. (171)

最後に, Weinreich, Labov and Herzog の著名な論文より引用する.

Linguistic and social factors are closely interrelated in the development of language change. Explanations which are confined to one or the other aspect, no matter how well constructed, will fail to account for the rich body of regularities that can be observed in empirical studies of language behavior. (188)

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey and Terrence Kaufman. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: U of California P, 1988.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey. Language Contact. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2001.

・ Filppula, Markku. "Endogeny vs. Contact Revisited." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 161--73.

・ Lass, Roger. Historical Linguistics and Language Change. Cambridge: CUP, 1997.

・ Weinreich, Uriel, William Labov, and Marvin I. Herzog. "Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change." Directions for Historical Linguistics. Ed. W. P. Lehmann and Yakov Malkiel. U of Texas P, 1968. 95--188.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow