2022-04-29 Fri

■ #4750. 社会言語学の3つのパラダイム [sociolinguistics][history_of_linguistics][language_change]

社会言語学 (sociolinguistics) と一口にいっても,幅広い領域なので研究内容は多岐にわたる.「#2545. Wardhaugh の社会言語学概説書の目次」 ([2016-04-15-1]) を眺めるだけでも,扱っている問題の多様性がうかがえるだろう.

社会言語学を研究対象となる現象の規模という観点からざっくり2区分すると,「#1380. micro-sociolinguistics と macro-sociolinguistics」 ([2013-02-05-1]) でみた通りになる.一方,学史的な観点を踏まえると,社会言語学では大きく3つのパラダイムが発展してきたので,3区分することも可能だ.以下は,Dittmar による3区分に依拠した Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg (18) の表である.社会言語学の見取り図として有用だ.

| Paradigm/Dimension | Sociology of language | Social dialectology | Interactional sociolinguistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Object of study | * status and function of languages and language varieties in speech communities | * variation in grammar and phonology * linguistic variation in discourse * speaker attitudes | * interactive construction and organization of discourse |

| Mode of inquiry | * domain-specific use of languages and varieties of language | * correlating linguistic and sociological categories | organization of discourse as social interaction |

| Fieldwork | * questionnaire * interview | * sociolinguistic interview * participant observation | * documentation of linguistic and non-linguistic interaction in different contexts |

| Describing | * the norms and patterns of language use in domain-specific conditions | * the linguistic system in relation to external factors | * co-operative rules for organization of discourse |

| Explaining | * differences of and changes in status and function of languages and language varieties | * social dynamics of language varieties in speech communities * language change | * communicative competence; verbal and nonverbal input in goal-oriented interaction |

"Sociology of language", "Social dialectology", "Interactional sociolinguistics" の3つのパラダイムは,それぞれ Joshua Fishman, William Labov, John Gumperz という著名な研究者と結びついている.

近年,英語史研究においても言語変化に関する社会言語学の洞察と方法論が導入され,「英語歴史社会言語学」という新領域の人気が急上昇している.ただし,英語史研究で注目されている社会言語学のパラダイムは,言語変化 (language_change) を扱う "Social dialectology" に限定されていることに注意.関連して「#4700. 英語史と社会言語学」 ([2022-03-10-1]) も参照.

・ Nevalainen, Terttu and Helena Raumolin-Brunberg. Historical Sociolinguistics: Language Change in Tudor and Stuart England. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge, 2017.

・ Dittmar, Norbert. Grundlagen der Soziolinguistik. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer, 1997.

2022-04-21 Thu

■ #4742. Oxford Bibliographies による統語変化研究の概要 [hel_education][history_of_linguistics][bibliography][syntax][grammaticalisation][generative_grammar][language_change][oxford_bibliographies]

分野別に整理された書誌を専門家が定期的にアップデートしつつ紹介してくれる Oxford Bibliographies より,"Syntactic Change" の項目を参照してみた(すべてを読むにはサブスクライブが必要).Acrisio Pires と David Lightfoot による選書で,最終更新は2013年,最終レビューは2017年となっている(そろそろ更新されないかと期待したい). *

英語史の分野では統語変化研究が非常に盛んであり,我が国でも先達のおかげで英語統語論の史的研究はよく進んでいる.しかし,学史を振り返ってみると,統語変化研究の隆盛は20世紀後半以降の現象といってよく,それ以前は音韻論や形態論の研究が主流だった.1950--60年代の生成文法の登場と,それに触発されたさまざまな統語研究のブームにより,英語史の分野でも統語への関心が高まってきたのである.21世紀に入ってからは,とりわけ文法化 (grammaticalisation) が注目され,統語変化研究は新局面に突入した.上記の "Syntactic Change" の項のイントロダクションより引用する.

Linguistics began in the 19th century as a historical science, asking how languages came to be the way they are. Almost all of the work dealt with the changing pronunciation of words and "sound change" more broadly. Much attention was paid to explaining why sounds changed the way they did, and that involved developing ideas about directionality. Work on syntax was limited to compiling how different languages expressed clause types differently, notably Vergleichende Syntax der Indogermanischen Sprachen, by Berthold Delbrück. With the greatly increased attention to syntax in the latter half of the 20th century, approaches to syntactic change were enriched significantly. Most of the work on change, both generative and nongenerative, continued the 19th-century search for an inherent directionality to language change, now in the domain of syntax, but other approaches were developed seeking to understand new syntactic systems arising through the contingent conditions of language acquisition.

Oxford Bibliographies からの話題としては,「#4631. Oxford Bibliographies による意味・語用変化研究の概要」 ([2021-12-31-1]) と「#4634. Oxford Bibliographies による英語史研究の歴史」 ([2022-01-03-1]) も参照.

2022-03-29 Tue

■ #4719. 歴史言語学の観点からみる方言学とは? [dialectology][historical_linguistics][variation][variety][hel][language_change]

方言学 (dialectology) と聞けば,ある言語の諸地域方言について調査し,それぞれの特徴を整理して示す分野なのだろうと思われるだろう.もちろん,それは事実なのだが,それだけではない.まず,「方言」には地域方言 (regional dialect) だけではなく社会方言 (social dialect) というものもある.また,私自身のように歴史言語学の観点からみる方言学は,さらに時間という動的なパラメータも考慮することになる.より具体的にいって英語史と方言学を掛け合わせたいと考えるならば,少なくとも空間,時間,社会という3つのパラメータが関与するのだ.

この話題について「#4168. 言語の時代区分や方言区分はフィクションである」 ([2020-09-24-1]) で論じたが,そこで引用した Laing and Lass の論考を改めて読みなおし,もっと長く引用すべきだったと悟った."On Dialectology" (417) という冒頭の1節だが,上記の事情がうまく表現されている.

There are no such things as dialects. Or rather, "a dialect" does not exist as a discrete entity. Attempts to delimit a dialect by topographical, political or administrative boundaries ignore the obvious fact that within any such boundaries there will be variation for some features, while other variants will cross the borders. Similar oversimplification arises from those purely linguistic definitions that adopt a single feature to characterize a large regional complex, e.g. [f] for <wh-> in present day Northeast Scotland or [e(:)] in "Old Kentish" for what elsewhere in Old English was represented as [y(:)]. Such definitions merely reify taxonomic conventions. A dialect atlas in fact displays a continuum of overlapping distributions in which the "isoglosses" delimiting dialectal features vary from map to map and "the areal transition between one dialect type and another is graded, not discrete" (Benskin 1994: 169--73).

To the non-dialectologist, the term "dialectology" usually suggests static displays of dots on regional maps, indicating the distribution of phonological, morphological, or lexical features. The dialectology considered here will, of course, include such items; but this is just a small part of our subject matter. Space is only one dimension of dialectology. Spatial distribution is normally a function of change over time projected on a geographical landscape. But change over time involves operations within speech communities; this introduces a third dimension --- human interactions and the intricacies of language use. Dialectology therefore operates on three planes: space, time, and social milieu.

歴史社会言語学的な観点から方言をみることに慣れ親しんできた者にとっては,この方言学の定義はスッと入ってくる.通時軸や言語変化も込みでの動的な方言学ということである.

・ Laing, M. and R. Lass. "Early Middle English Dialectology: Problems and Prospects." Handbook of the History of English. Ed. A. van Kemenade and Los B. L. Oxford: Blackwell, 2006. 417--51.

・ Benskin, M. "Descriptions of Dialect and Areal Distributions." Speaking in Our tongues: Medieval Dialectology and Related Disciplines. Ed. M. Laing and K. Williamson. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1994. 169--87.

2022-03-06 Sun

■ #4696. エリザベス1世による3単現 -th と -s が入り乱れた散文 [3sp][emode][monarch][speed_of_change][language_change]

初期近代英語期に3単現の語尾が -th から -s へと推移していった変化は,英語史でよく研究されている.本ブログでも「#2141. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の概要」 ([2015-03-08-1]),「#1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力」 ([2014-05-28-1]),「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]),「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]) などで取り上げてきた.

エリザベス1世 (1533--1603) の時代は -th から -s への推移のまっただなかにあり,女王自身も両語尾を併用しているが,明確な使い分けの基準があったわけではない.当時は,すでに話し言葉では -s が普通に用いられ,韻文(書き言葉)であれば -th が好まれるという段階にはあったが,では,その中間的なレジスターともいえる散文(書き言葉)ではどうだったのかというと,事情は複雑だ.Lass (163) に引用されている,エリザベス1世が Boethius を英訳した The Consolation of Philosophy より1節を覗いてみよう (Book 0, Prose IX) .

He that seekith riches by shunning penury, nothing carith for powre, he chosith rather to be meane & base, and withdrawes him from many naturall delytes. . . But that waye, he hath not ynogh, who leues to haue, & greues in woe, whom neerenes ouerthrowes & obscurenes hydes. He that only desyres to be able, he throwes away riches, despisith pleasures, nought esteems honour nor glory that powre wantith.

Lass (163) によると,同英訳書のサンプルで調査したところ,-th と -s の比はおよそ 1:2 だったという.すでに -s が上回っていたようだが,まだ推移のまっただなかだったと言ってよいだろう.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 56--186.

2022-03-02 Wed

■ #4692. 類型論の3つの問題,および類型論と言語変化の関係について [typology][diachrony][language_change][how_and_why]

類型論 (typology) は,通言語的にみられる言語普遍性や普遍的傾向を扱う分野である.類型論が研究対象とする分野は多岐にわたるが,同分野の入門書を著わした Whaley (28) は3つの点を指摘している.

The starting point for all typology is the presupposition that there are recurrent structural patterns across languages that are not random or accidental. These patterns can be described in statements called language universals.

Once one grants this simple assumption, myriad questions arise. . . . [T]ypologists explore both absolute properties of language and probabilistic properties. In addition, they are concerned with the connections between two or more properties.

A second key question about universals is "How are they determined?" . . . . For now, it is sufficient to say that this question has become central to typology in the past few decades, and its answer has profound implications, particularly for universals that are based on statistical probability.

The final basic question that concerns modern typology is "How are universals explained?" A protracted debate over issues of explanation has been occurring since the 1950s. The most acrimonious elements of the debate have concerned the relationship between diachrony and synchrony (i.e., to what degree does an explanation require reference to past stages of a language?) and the need to go outside the language system itself in forming satisfying explanations . . . .

ここに挙げられている類型論上の3つの関心は,それぞれ類型論上の特徴に関する What, How, Why の問いととらえてよいだろう.

歴史言語学の立場からは,とりわけ3つめの Why の問題が,通時態が関わってくる点で重要である.類型論と言語変化の関係を巡る問題について,Whaley (25--26) の説明を聞こう.

Another characteristic trait of modern typology that is represented well in Greenberg's work is a focus on the ways that language changes through time . . . . Greenberg's interest in diachrony was in many ways a throwback to the earlier days of typology in which historical-comparative linguistics predominated. The uniqueness of Greenberg's work, however, was in his use of language change as an explanation for language universals. The basic insight is the following: Because the form that a language takes at any given point in time results from alterations that have occurred to a previous stage of the language, one should expect to find some explanations for (or exceptions to) universals by examining the processes of language change. In other words, many currently existing properties of a language can be accounted for in terms of past properties of the language.

類型論という基本的には共時的な視点をとっている巨大な分野に,さらに通時的視点を投入するとなると,なかなか壮大な議論になっていきそうだ.

・ Whaley, Lindsay J. Introduction to Typology: The Unity and Diversity of Language. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1997.

2022-02-18 Fri

■ #4680. Bybee による言語変化の「なぜ」 [language_change][causation][how_and_why][multiple_causation][cognitive_linguistics][usage-based_model][context][analogy]

言語変化論の第一人者である Bybee (9) が,標題の問題について大きな答えを与えている.

A very general answer is that the words and constructions of our language change as they cycle through our minds and bodies and are passed through usage from one speaker to another.

言語変化の「なぜ」というより「どのように」への答えに近いのではないかと考えられるが,いずれにせよこの1文だけで Bybee の言語変化観の枠組みをつかむことができる.一言でいえば,認知基盤および使用基盤の言語変化観である.

続けて Bybee は,言語変化には3つの傾向が見いだされると主張する.引用により,その3点の骨子を示す.

Because language is an activity that involves both cognitive access (recalling words and constructions from memory) and the motor routines of production (articulation), and because we use the same words and constructions many times over the course of a day, week, or year, these words and constructions are subject to the kinds of processes that repeated actions undergo. (9)

Another pervasive process in the human approach to the world is the formation of patterns from our experience and application of these patterns to new experiences or ideas. (10)

The other major factor in language change is the way words or patterns of language are used in context. Very often the meaning supplied by frequently occurring contexts can lead to change. Words and constructions that are used in certain contexts become associated with those contexts. (10)

1つめは認知・運動基盤,2つめは広い意味での類推作用 (analogy),3つめは使用基盤 (usage-based_model) と言い換えてもよいだろう.

・ Bybee, Joan. Language Change. Cambridge: CUP, 2015.

2022-01-29 Sat

■ #4660. 言語の「世代変化」と「共同変化」 [language_change][schedule_of_language_change][sociolinguistics][do-periphrasis][methodology][progressive][speed_of_change]

通常,言語共同体には様々な世代が一緒に住んでいる.言語変化はそのなかで生じ,広がり,定着する.新しい言語項は時間とともに使用頻度を増していくが,その頻度増加のパターンは世代間で異なっているのか,同じなのか.

理論的にも実際的にも,相反する2つのパターンが認められるようである.1つは「世代変化」 (generational change),もう1つは「共同変化」 (communal change) だ.Nevalainen (573) が,Janda を参考にして次のような図式を示している.

(a) Generational change

┌──────────────────┐

│ │

│ frequency │

│ ↑ ________ G6 │

│ ________ G5 │

│ ________ G4 │

│ ________ G3 │

│ ________ G2 │

│ ________ G1 time → │

│ │

└──────────────────┘

(b) Communal change

┌──────────────────┐

│ │

│ frequency | │

│ ↑ | | G6 │

│ | | G5 │

│ | | G4 │

│ | | G3 │

│ | | G2 │

│ | G1 time → │

│ │

└──────────────────┘

世代変化の図式の基盤にあるのは,各世代は生涯を通じて新言語項の使用頻度を一定に保つという仮説である.古い世代の使用頻度はいつまでたっても低いままであり,新しい世代の使用頻度はいつまでたっても高いまま,ということだ.一方,共同変化の図式が仮定しているのは,全世代が同じタイミングで新言語項の使用頻度を上げるということだ(ただし,どこまで上がるかは世代間で異なる).2つが対立する図式であることは理解しやすいだろう.

音変化や形態変化は世代変化のパターンに当てはまり,語彙変化や統語変化は共同変化に当てはまる,という傾向が指摘されることもあるが,実際には必ずしもそのようにきれいにはいかない.Nevalainen (573--74) で触れられている統語変化の事例を見渡してみると,16世紀における do 迂言法 (do-periphrasis) の肯定・否定平叙文での発達は,予想されるとおりの世代変化だったものの,17世紀の肯定文での衰退は世代変化と共同変化の両パターンで進んだとされる.また,19世紀の進行形 (progressive) の増加も統語変化の1つではあるが,むしろ共同変化のパターンに沿っているという.

具体的な事例に照らすと難しい問題は多々ありそうだが,理論上2つのパターンを区別しておくことは有用だろう.

・ Nevalainen, Terttu. "Historical Sociolinguistics and Language Change." Chapter 22 of The Handbook of the History of English. Ed. Ans van Kemenade and Bettelou Los. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006. 558--88.

・ Janda, R. D. "Beyond 'Pathways' and 'Unidirectionality': On the Discontinuity of Language Transmission and the Counterability of Grammaticalization''. Language Sciences 23.2--3 (2001): 265--340.

2021-10-23 Sat

■ #4562. 通時態は共時態に歴史的与件を提供する [saussure][diachrony][language_change][sociolinguistics][link]

ソシュール以来,共時態 (synchrony) と通時態 (diachrony) の関係を巡る論争は絶えたためしがない.本ブログでも,この話題について様々に議論してきた.

・ 「#866. 話者の意識に通時的な次元はあるか?」 ([2011-09-10-1])

・ 「#1025. 共時態と通時態の関係」 ([2012-02-16-1])

・ 「#1076. ソシュールが共時態を通時態に優先させた3つの理由」 ([2012-04-07-1])

・ 「#1260. 共時態と通時態の接点を巡る論争」 ([2012-10-08-1])

・ 「#2134. 言語変化は矛盾ではない」 ([2015-03-01-1])

・ 「#2197. ソシュールの共時態と通時態の認識論」 ([2015-05-03-1])

・ 「#2555. ソシュールによる言語の共時態と通時態」 ([2016-04-25-1])

・ 「#3264. Saussurian Paradox」 ([2018-04-04-1])

・ 「#3508. ソシュールの対立概念,3種」 ([2018-12-04-1])

言語にアプローチする2つの態に関して私の考えるところによれば,通時態は共時態に歴史的与件を提供するものではないか.歴史的与件とは,その時点で過去から受け継いだ言語的資産目録というほどの意味である.両態は確かに直行する軸であり性質がまるで異なっているのだが,現在という時点において唯一の接触点をもつ.この接触点に両態のエネルギーが凝縮しているとみている.時間軸上のある1点における断面図である言語の共時態は,通時態からエネルギーを提供されて,そのような断面図になっているのだ.

Sweetser (9--10) が著書の序章において,ソシュールのチェスの比喩をあえて引用しつつ,似たような見解を示しているので引用したい.

. . . [W]e cannot rigidly separate synchronic from diachronic analysis: all of modern sociolinguistics has confirmed the importance of reuniting the two. As with the language and cognition question, the synchrony/diachrony interrelationship has to be seen in a more sophisticated framework. The structuralist tradition spent considerable effort on eliminating confusion between synchronic regularities and diachronic changes: speakers do not necessarily have rules or representations which reflect the language's past history. But neither Saussure nor any of his colleagues would have denied that synchronic structure inevitably reflects its history in important ways: the whole chess metaphor is a perfect example of Saussure's deep awareness of this fact. Saussure, of course, uses chess because for future play the past history of the board is totally irrelevant: you can analyze a chess problem without any information about past moves. But he could hardly have picked --- as he must have known --- an example of a domain where past events more inevitably, regularly, and evidently (if not uniquely) determine the present resulting state. No phonologist today would reconstruct a proto-language's sound system without attention both to recognized universals of synchronic sound-systems and to attested (and phonetically motivated) paths of phonological change; it is assumed that the same perceptual, muscular, acoustic, and cognitive constraints are responsible for both universals of structure and universals of structural change. And, for a historical phonologist or semanticist trying to avoid imposing past analyses on present usage, it is an empirical question which aspects of diachrony are preserved in a given synchronic phonological structure or meaning structure.

詰め将棋は本番のための訓練としてはよいが,本番そのものではない.言語研究も,本番の真剣勝負こそを観察対象とするものであってほしい.

・ Sweetser, E. From Etymology to Pragmatics. Cambridge: CUP, 1990.

2021-10-14 Thu

■ #4553. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (4) [contact][language_change][causation][how_and_why][multiple_causation]

標題の話題について,本ブログでもたびたび議論してきた.例えば次の通り.

・ 「#443. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か?」 ([2010-07-14-1])

・ 「#1232. 言語変化は雨漏りである」 ([2012-09-10-1])

・ 「#1233. 言語変化は風に倒される木である」 ([2012-09-11-1])

・ 「#1582. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (2)」 ([2013-08-26-1])

・ 「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1])

・ 「#1977. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (1)」 ([2014-09-25-1])

・ 「#1978. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (2)」 ([2014-09-26-1])

・ 「#1986. 言語変化の multiple causation あるいは "synergy"」 ([2014-10-04-1])

・ 「#3152. 言語変化の "multiple causation"」 ([2017-12-13-1])

・ 「#3271. 言語変化の multiple causation 再考」 ([2018-04-11-1])

・ 「#3355. 言語変化の言語内的な要因,言語外的な要因,"multiple causation"」 ([2018-07-04-1])

・ 「#3377. 音韻変化の原因2種と結果3種」 ([2018-07-26-1])

・ 「#3842. 言語変化の原因の複雑性と多様性」 ([2019-11-03-1])

・ 「#3971. 言語変化の multiple causation 再再考」 ([2020-03-11-1])

今回は,もう1つ Hickey (487--88) より議論を追加したい.この問題を巡る近年の様々な立場が,要領よくまとめられている.

2.1 Language-internal versus contact factors

In the current context language-internal change is understood as that which occurs within a speech community, among monolingual speakers, and contact-induced change as that which is induced by interfacing with speakers of a different language.

Opinions are divided on when to assume contact as the source of change. Some authors insist on the primacy of internal factors . . . and so favor these when the scales of probability are not biased in either direction for any instance of change. Other scholars view contact explanations more favorably . . . while still others would like to see a less dichotomous view of internal versus and external factors in change . . . .

The fate of explanations based on language contact has varied in recent linguistic literature. During the 1980s many linguists reacted negatively to apparently superficial contact explanations . . . . Others . . . have been consistently skeptical of contact explanations, stressing the coherent internal structure of languages and assuming by default that this is the locus of new features. This position has also been theoretically contested . . . , as it is unproven that language-internal factors take automatic precedence over contact in language change.

Another point needs to be highlighted: at best contact accounts for a phenomenon but does not explain why this should have arisen in the first place. Contact treatments tend to push sources back a step, but not to explain ultimate origins. Rather contact seeks to account for how features come about. "Account" is a more muted term and does not raise expectations of high degrees of adequacy implied by "explanation" . . . .

It would be blind to neglect the possible language-internal arguments for various features suspected of having a contact source. If internal arguments are considered and then deemed insufficient on their own, this actually strengthens the contact case, as contact is then seen as a necessary contributory factor to account fully for the appearance of features. Ultimately, contact accounts depend for acceptance on whether scholars are convinced by what they know about contact scenarios in general, specific contact in the case being discussed, possible alternative accounts and the crucial balance of internal and external factors.

Given that both language-internal and contact sources are available to speakers, it might be fair to postulate that no matter what the likelihood of transfer though contact, language internal factors can always play a role. It is the nature and rate of change which can be influenced by contact, a factor which can vary in intensity.

私自身は,この問題について様々な意見を読み考えてきたが,言語変化一般についていえば言語内的・外的要因の両方が等しく重要であるという立場から動いたことはない.ただし,個別の言語変化についていえば,いずれかの要因がより強く作用しているということはあり得ると考える.

・ Hickey, Raymond. "Assessing the Role of Contact in the History of English." Chapter 37 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of English. Ed. Terttu Nevalainen and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. New York: OUP, 2012. 485--96.

2021-06-26 Sat

■ #4443. 法助動詞の発達と構文文法 [auxiliary_verb][grammaticalisation][construction_grammar][preterite-present_verb][language_change][generative_grammar]

英語史や言語変化の研究において,法助動詞 (modal verb) の発達の問題は,とりわけ生成文法 (generative_grammar) や文法化 (grammaticalisation) などの理論的な観点から注目されてきた.古英語期やそれ以前から存在した過去現在動詞 (preterite-present_verb) に端を発し,中英語期には文法化を通じて各種の法助動詞が生まれ,そして近現代英語期に至っても準助動詞と称される仲間たちが続々と誕生している.主として注目される時期は文法化が進行していた後期中英語から初期近代英語にかけてだが,その前後を含めれば相当に息の長い言語変化である.本ブログでは以下の記事などで取り上げてきた.

・ 「#1670. 法助動詞の発達と V-to-I movement」 ([2013-11-22-1])

・ 「#1406. 束となって急速に生じる文法変化」 ([2013-03-03-1])

・ 「#3528. 法助動詞を重ねられた時代」 ([2018-12-24-1])

・ 「#64. 法助動詞の代用品が続々と」 ([2009-07-01-1])

最初の2つの記事で触れたように,Lightfoot によると,多くの法助動詞は短期間に生じ,その過程は16世紀初期までに完了していたという.しかし,この見方には異論がある.Bergs (1640--41) によれば,むしろ各法助動詞は時期的にバラバラに発達しているし,法助動詞的な諸特徴が一斉に獲得されたわけでもなかった,というのだ.

時期的にバラバラに発達した件について,Bergs は次のように述べる.法助動詞化の嚆矢となったのは,おそらく motan, magan である.両者ともにすでに古英語期に法助動詞的な特徴を示していた.次に,初期中英語で cunnan が,後期中英語で willan が発達した.過去形の should, would, could, might も各々バラバラの時期に法助動詞化しており,対応する現在形より早かったケースもある.さらに,法助動詞化の過程において新旧の形態が共存していた "layering" の事実も確認されている.つまり,すべてが徐々にゆっくり進行していたというわけだ.

また,法助動詞的な諸特徴が一斉に獲得されたわけではないという件についても,Bergs は次のように述べる.直接目的語を取らないという法助動詞の特徴は,あるとき一夜にして生じたものではなく,あくまで徐々に獲得されてきたものである.また,形態的無屈折という特徴についても同様.

Bergs は,法助動詞化の問題を,構文文法 (construction_grammar) の枠組みでとらえようとしている.構文文法は,言語体系を構文間のネットワークととらえ,言語変化をそのネットワークの変化ととらえる.したがって,法助動詞化という言語変化は,問題の動詞の形式・機能的特徴が,それまでの他の構文との関わり方を変化させ,ネットワークの組み替えを行なったということにほかならない.そして,そのネットワークの組み替えは,あくまで徐々にゆっくりと起こったものであると説く.

法助動詞の発達は,文法化の典型例として紹介されることが多いが,構文文法の枠組みにあっては上記のように構文化 (constructionalization) の典型例として解釈されるのである.

・ Lightfoot, David W. "Cuing a New Grammar." Chapter 2 of The Handbook of the History of English. Ed. Ans van Kemenade and Bettelou Los. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006. 24--44.

・ Bergs, Alexander. "New Perspectives, Theories and Methods: Construction Grammar." Chapter 103 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1631--46.

2021-06-16 Wed

■ #4433. J. Milroy の「弱い絆」理論と W. Labov の「強い絆」理論 [social_network][weakly_tied][language_change][sociolinguistics]

社会言語学の social_network の理論によれば,ある集団に強固には組み込まれておらず,他集団と弱く結びついている (weakly_tied) 個人こそが,言語的革新を拡散させるのに重要な役割を果たすという.James Milroy の研究によって広く知られるようになった理論であり,本ブログでも「#882. Belfast の女性店員」 ([2011-09-26-1]),「#1179. 古ノルド語との接触と「弱い絆」」 ([2012-07-19-1]),「#1352. コミュニケーション密度と通時態」 ([2013-01-08-1]) などで取り上げてきた.

この理論について,もう少し詳しく説明しよう.結束の固いネットワークは,外部からもたらされる革新の受容を拒む保守的な傾向を示す一方,そのようなネットワークと弱いつながりをもつにすぎない個人は,外部からの革新を受容しやすく,そのネットワーク内部にその革新を染み込ませていく入口になり得るという洞察だ.別の見方をすれば,「弱い絆」に特徴づけられる個人は,内部の「強い絆」に特徴づけられる個々のネットワーク間の橋渡しの役割を演じることがあるということだ.もちろん「弱い絆」をもつ個人が常に革新の橋渡しに貢献するということではなく,革新の橋渡しがなされているのであれば,そこにそのような個人が関わっているはずだという理屈だ (Milroy 176--79) .

一方で,William Labov (351, 360, 364) は,これに対して真っ向から対立する立場を取っている.言語的革新を拡散させるのは,内部にも外部にも「強い絆」をもっている指導者たちであるという.内部からも外部からも社会的に一目を置かれる「参照点」となる指導者こそが,革新の拡散に貢献するだろう.これに対して,Milroy は Labov の想定するような内部にあっても外部にあっても中心的な指導者など存在し得ないと反論している.

実際のところ,各々の理論を支持する事例が見つかっており,どちらが絶対的に正しいということではなさそうである.Britain (2034) は,Raumolin-Brunberg (2006) を参照しながら,両理論を止揚する見解を紹介している.

[D]rawing on evidence from the Helsinki Corpus of Early English Correspondence, Raumolin-Brunberg (2006) was able to suggest that both the Labovian and Milroyian approaches to finding the social locus of the diffusers of change may be accurate, sometimes. For a number of different features, she examined the rates of change at different stages of progress, and was, thereby, able to shed light on the strength of innovators' network ties at those different stages. When changes were in their infancy, she found that it was those individuals who were highly mobile and who had social profiles characterized by many weak social networks that were leading the change. When the changes were somewhat more advanced, however, it was individuals who were influential central "pillars" of their communities, with strong multiplex social ties, that were leading. She was able to conclude, therefore, that the two positions are perhaps not mutually exclusive, but simply reflect the position at different points along the life-cycle of a change.

また,Britain (2035) は,両理論の同意している点が1つあると述べている.言語変化をリードするのは,中ほどの階層 ("the upper working and lower middle classes") であるということだ (cf. 「#1371. New York City における non-prevocalic /r/ の文体的変異の調査」 ([2013-01-27-1])) .

論争を通じて理解が深まっている感がある.

・ Milroy, James. Linguistic Variation and Change: On the Historical Sociolinguistics of English. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

・ Labov, William. Principles of Linguistic Change: Social Factors. Oxford: Blackwell, 2001.

・ Raumolin-Brunberg, Helena. "Leaders of Linguistic Change in Early Modern England." Corpus-Based Studies of Diachronic English Ed. Roberta Facchinetti and Matti Rissanen. Bern: Peter Lang, 115--34.

・ Britain, David. "Varieties of English: Diffusion." Chapter 129 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 2031--43.

2021-01-12 Tue

■ #4278. クブラーの『時のかたち』からのインスピレーション [historiography][periodisation][speed_of_change][language_change][teleology]

ある言語の体系や正書法を「本来非同期的な複数の時のかたちが一瞬出会った断面」ととらえる見解について,美学者・考古学者のクブラー (George Kubler [1912--96]) を引用・参照しながら「#3911. 言語体系は,本来非同期的な複数の時のかたちが一瞬出会った断面である」 ([2020-01-11-1]) の記事で論じた.また,クブラー流の歴史観・時間観に触発されて,他にも「#3083. 「英語のスペリングは大聖堂のようである」」 ([2017-10-05-1]),「#3874. 「英語の正書法はパリのような大都会である」」 ([2019-12-05-1]),「#3912. (偽の)語源的綴字を肯定的に評価する (1)」 ([2020-01-12-1]),「#3913. (偽の)語源的綴字を肯定的に評価する (2)」 ([2020-01-13-1]) の記事を書いてきた.

今回,クブラーの『時のかたち』を読了し,言語がそのなかで変化していく「時間」について,改めて考えを巡らせた.言語変化の速度 (speed_of_change) や言語史における時代区分 (periodisation) に関してインスピレーションを得た部分が大きいので,関連する部分を備忘録的に引用しておきたい.

物質の空間の占め方がそうであるように,事物の時間の占め方は無限にあるわけではない.時間の占め方の種類を分類することが難しいのは,持続する期間に見合った記述方法を見つけ出すことが難しかったからである.持続を記述しようとしても,出来事を,あらかじめ定められた尺度で計測しているうちに,その記述は出来事の推移とともに変化してしまう.歴史学には定められた周期表もなく,型や種の分類もない.ただ太陽時と,出来事を区分けする旧来の方法が二,三あるのみで,時間の構造についての理論は一切なかったのである.

出来事はすべて独自なのだから分類は不可能だとするような非現実的な考え方をとらず,出来事にはその分類を可能とする原理があると考えれば,そこで分類された出来事は,疎密に変化する秩序を持った時間の一部として群生していることがわかる.この集合体のなかには,後続する個々の出来事によってその要件が変化していくような諸問題に対して,漸進的な解決として結びつく出来事が含まれている.その際,出来事が急速に連続すればそれは密な配列となり,多くの中断を伴う緩慢な連続であれば配列は疎となる.美術史ではときおり,一世代,ときには一個人が,ひとつのシークエンスにとどまらず,一連のシークエンス全体のなかで,多くの新しい地位を獲得することがある.その対極として,目前の課題が,解決されないまま数世代,ときには何世紀にもわたって存続することもある.(189--90)

時代とその長さ

こうして,あらゆる事物はそれぞれに異なった系統年代に起因する特徴を持つだけでなく,事物の置かれた時代がもたらす特徴や外観としてのまとまりをも持った複合体となる.それは生物組織も同様である.哺乳類の場合であれば,その血液と神経は生物史(絶対年代)的な見地での歴史が異なっているし,眼と皮膚というそれぞれの組織はその系統年代と異なっている.

事物の持続期間は絶対年代と系統年代というふたつの基準で計測が可能である.そのために歴史的時間は未来から現在を通過して過去へと続く単純な絶対年代の流れに加えて,系統年代という多数の包皮から構成されているとみなすことができる.この包皮は,いずれも,それが包んでいるその内容によって持続時間が決定されるために,その輪郭は多様なものとなるが,大小の異なった形状の系に容易に分類することができる.誰しも自身の生活のなかの同じ行為の初期のやり方と後期のやり方からなるこのようなパターンの存在を見出すことができるが,ここで,個人の時間における微細な形式にまで立ち入るつもりはない.それらは,ほんの数秒の持続から生涯にわたるものまで,個人のあらゆる経験に見出すことができる.しかし,私たちがここで注目したいのは,人の一生より長く,集合的に持続して複数の人数分の時間を生きている形や形式についてである.そのなかで最小の系は入念につくり上げられた毎年の服装の流行である.それは,現代の商業化された生活では服飾産業によるものであり,産業革命以前には宮廷の儀礼によるものであった.そこではこの流行を着こなすことが外見的に最も確かな上流階級の証しだったのである.一方,全宇宙のような大規模な形のまとめ方はごくわずかである.それらは人類の時間を巨視的にとらえた場合にかすかに思い浮かぶ程度のものである.すなわち,西洋文明,アジア文化,あるいは先史,未開,原始の社会などである.そして最大と最小の中間には,太陽暦や十進法にもとづく慣習的な時間がある.世紀という単位の本当の優位性は,おそらく自然現象にも,またそれが何であれ,人為的な出来事のリズムにも対応していないことになるのかもしれない.その例外は,西暦千年紀が近づいたときに終末論的な雰囲気が人々を襲ったことや,フランス革命中に恐怖政治が行われた一七九〇年代との単なる数値の類似が一八九〇年以降に世紀末の無気力感を引き起こしたことぐらいである.(193--95)

私たちは,〔中略〕時間の流れを繊維の束と想定することができる.それぞれの繊維は,活動のための特定の場として必要に応え,繊維の長さは必要とその問題に対する解決の持続に応じてさまざまである.したがって,文化の束は,出来事という繊維状のさまざまな長さの期間で構成される.その長さはたいてい長いのだが,短いものも多数ある.それらはほとんど偶然によって並べられ,意識的な将来への展望や緻密な計画によって並べられることはめったにないのである.(228)

最後の引用にある比喩を言語に当てはめれば,言語体系とは異なる長さからなる繊維の束の断面であるという見方になる.「言語体系」を,その部分集合である「正書法」「音韻体系」「語彙体系」などと置き換えてもよい.これと関連する最も理解しやすい卑近な例として,数語からなる短い1つの英文を考えてみるとよい.その構成要素である各語の語源(由来や初出年代)は互いに異なっており,体現される音形・綴字や,それらを結びつけている文法規則も,各々歴史的に発展してきたものである.この短文は,異なる長さの時間を歩んできた個々の部品から成り立っており,偶然にこの瞬間に組み合わされて,ある一定の意味を創出しているのである.

・ クブラー,ジョージ(著),中谷 礼仁・田中 伸幸(訳) 『時のかたち 事物の歴史をめぐって』 鹿島出版会,2018年.

2020-12-25 Fri

■ #4260. 言葉使いの正しさとは? --- ことばの正誤について [purism][register][dialect][language_change][prescriptivism]

言葉使いに関して「正しい」「正しくない」と評価することは日常茶飯である.ら抜き言葉は正しくない.雰囲気の発音は「ふいんき」ではなく「ふんいき」が正しい.こんにち「わ」ではなく,こんにち「は」の書き方が正しい,等々.一般に言葉使いには規範的に正しい答えがあると信じられており,それに照らして正誤を判断するわけだ.

しかし,言語学的にいえば --- 記述主義的にいえば --- 言葉使いに「正誤」の問題は存在しない.「正しくない」とおぼしきケースがあったとしても,それは「正しくない」というよりは,むしろ「通じない」や「ふさわしくない」に近いことが多い.

Hughes et al. (16) は言葉使いの "correctness" について,3種類を区別している.

The first type is elements which are new to the language. Resistance to these by many speakers seems inevitable, but almost as inevitable, as long as these elements prove useful, is their eventual acceptance into the language. The learner needs to recognize these and understand them. It is interesting to note that resistance seems weakest to change in pronunciation. There are linguistic reasons for this but, in the case of the RP accent, the fact that innovation is introduced by the social elite must play a part.

The second type is features of informal speech. This, we have argued, is a matter of style, not correctness. It is like wearing clothes. Most people reading this book will see nothing wrong in wearing a bikini, but such an outfit would seem a little out of place in an office (no more out of place, however, than a business suit would be for lying on the beach). In the same way, there are words one would not normally use when making a speech at a conference which would be perfectly acceptable in bed, and vice versa.

The third type is features of regional speech. We have said little about correctness in relation to these, because we think that once they are recognized for what they are, and not thought debased or deviant forms of the prestige dialect or accent, the irrelevance of the notion of correctness will be obvious.

第1のものは,言語変化によってもたらされた新表現の類いである.純粋主義者を含めた言語について保守的な陣営から,しばしば「正しくない」とレッテルを貼られる語法などである.多くは時間とともに言語共同体のなかで広く受け入れられ,「正しい」語法へと格上げされていく.

第2のものは,語法そのものの正誤の問題というよりは,用いる場面を間違えてしまうという,register の観点からの「ふさわしさ」の問題といえば分かりやすいだろうか.ビキニを着ることそれ自体は問題ないが,会社で着るのは問題だ,という比喩がとても分かりやすい.

第3のものは,地域方言に関する誤解である.標準語使用が予期される文脈で地域方言の語法が用いられるとき誤解が生じることがあるが,後に単に地域方言の語法だったと分かり,誤解が解けさえすれば,言葉使いの正誤の問題とはみなさなくなるだろう.

日常生活である言葉使いが「正しくない」と思ったとき,それが記述主義的な立場からどのように解釈できるか,冷静に考えてみるとおもしろい.

・ Hughes, Arthur, Peter Trudgill, and Dominic Watt. English Accents and Dialects: An Introduction to Social and Regional Varieties of English in the British Isles. 4th ed. London: Hodder Education, 2005.

2020-12-10 Thu

■ #4245. 頻度と漸近双曲線 (A-curve) [lexical_diffusion][zipfs_law][frequency][statistics][language_change][uniformitarian_principle]

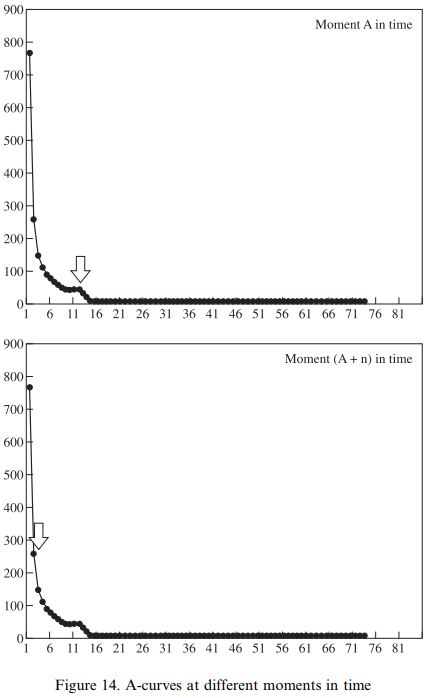

variationist の立場を高度に押し進めた言語(変化)観を提案する,Kretzschmar and Tamasi の論考を読んだ."A-curve", "asymptotic hyperbolic distribution", "power law", "S-curve" などの用語が連発し思わず身構えてしまう論文だが,言わんとしていることは Zipf's Law (cf. zipfs_law) の発展版のように思われる.低頻度の言語項は多く,高頻度の言語項は少ないということだ.

ある英語コーパスにおいて,1度しか現われない語は相当数ある.一方,the, of, have などは超高頻度で現われるが,主として機能語であり種類数でいえば相当に限定される.例えば,1回しか現われない語 ( x = 1 ) は1000個 ( y = 1000 ) あるが,1000回も現われる語 ( x = 1000 ) は the の1語しかない ( y = 1 ) とすると,これを座標上にプロットしてみれば第1象限の左上と右下に点が打たれることになる.この2点を両端として,その間の点を次々と埋めていくと,y = 1/x で表わせるような漸近双曲線 (asymptotic hyperbolic curve) の片割れに近づくだろう.これを Kretzschmar and Tamasi は "A-curve" と呼んでおり,背後にある法則を "power law" (べき乗則)と呼んでいる.後者は "few realizations that occur very frequently and many realizations that occur infrequently" (384) ということである.

Kretzschmar and Tamasi は,アメリカ方言における訛語や調音の variants を調査し,各種の変異形について頻度の分布を取った.結果として,いずれのケースについても "A-curve" が観察されることを示した.

また,Kretzschmar and Tamasi は,語彙拡散 (lexical_diffusion) との関連でしばしば言及される "S-curve" と,彼らの "A-curve" との関係についても議論している.同一の言語変化を異なる軸に着目してプロットすると "S-curve" にも "A-curve" にもなり,両者は矛盾しないどころか,親和性が高いという.

私の拙い言葉使いでは上手く解説することができないのだが,言語体系や言語変化を徹底的に variationist に眺めようとすると,このような言語観あるいは言語理論になるのかと感心した.Kretzschmar and Tamasi (394) より,とりわけ重要と思われる箇所を引用する.

Our second observation, about the distribution of variants according to Zipf's Law, has the strongest set of implications for historical study of language. If we take the A-curve as the model for the frequency distribution of variants for any linguistic feature of interest to us at any moment in time, then we should expect that any particular variant of interest to us will have a particular rank along the A-curve. Therefore, one of the things that we should try to do for any given moment in time is to determine the place of our variant of interest on the curve; we need to know whether it is the most frequent variant in the set of possible realizations (at the top of the curve), or an infrequent variant (in the tail of the curve). Then, for any subsequent moment in time, we can again try to determine the location of our variant of interest along the curve, and so try to make a statement about whether the location of the variant has changed in the intervening time (see Figure 14). Since we hypothesize that an A-curve will exist for every feature at any moment in time (i.e., that language will not suddenly become invariant), we can define the notion "linguistic change" itself as the change in the location of the target variant at different heights along the curve. If a particular variant occurs at a higher place on the curve than it did before, it has become more frequent and so we can say that the direction of change for that variant is positive; if a variant occurs at a lower place on the curve than it did before, it has become less frequent and the direction of change is negative.

・ Kretzschmar, Jr.,William A and Susan Tamasi. "Distributional Foundations for a Theory of Language Change." World Englishes 22 (2003): 377--401.

2020-12-07 Mon

■ #4242. ソシュールにとって記号の変化は「ズレ」ではなく「置換」 [terminology][saussure][sign][language_change][diachrony][semiotics]

ソシュール (Ferdinand de Saussure; 1857--1913) は,言語の共時態 (synchrony) と通時態 (diachrony) を区別したことで知られる (2つの態についてはこちらの記事セットを参照).ソシュールは通時的次元を「諸価値の変動のことであり,それは有意単位の変動ということにほかならない」(丸山,p. 310)と定義している.この「変動」は,フランス語 déplacement (英語の displacement)の訳語だが,むしろ「置換」と理解したほうが分かりやすい.ソシュールは,シニフィエ (signifié) とシニフィアン (signifiant) の結合から成る記号 (signe) の変化は,両者の「ずれ」というよりも,別の記号による「置換」と考えている節があるからだ.

同じ丸山『ソシュール小事典』より déplacement の項 (284) を繰ってみると訳語としてこそ「ずれ,変動」と記されているが,内容をよく読んでみると実際には「置換」にほかならない.以下,引用する.

déplacement [ずれ,変動]

ラングなる体系内での辞項 (terme) の布置が変り,その結果として価値 (valeur) の変動が起こること.「辞項と諸価値のグローバルな関係のずれ (frag. 1279) .動詞形の déplacer (ずらす)も用いられた「いかなるラングも(…)変容 (altération) の諸要因に抗するすべはない.その結果,時とともにシニフィエ (signifie) に対するシニフィアン (signifiant) のトータルな関係 (rapport) がずらされる」 (frag. 1259) .このずれは,シーニュ (signe) 内での不可分離な二項がずれるという意味ではなく,シーニュの輪郭を決定する分節線そのものがずれて新しいシーニュが誕生することを意味するが,古いシーニュと新しいシーニュを比較する際,語る主体 (sujet parlant) にとってはシニフィアンとシニフィエがずれたように錯覚されるのである.

つまり,"déplacement" という用語を,記号内のシニフィエとシニフィアンの関係の「ずれ,変動」を指すものであるかのように使っているが,実際にソシュールが意図していたのは「ずれ」ではなく「置換」なのである(「再生」ですらない).とすると,語の音声変化や意味変化も,シニフィエかシニフィアンの片方は固定していたが他方がずれたのである,とはみなせなくなる.古いシーニュが新しいシーニュに置き換えられたのだと,みなすことになろう.

・ 丸山 圭三郎 『ソシュール小事典』 大修館,1985年.

2020-11-23 Mon

■ #4228. 歴史言語学は「なぜ変化したか」だけでなく「なぜ変化しなかったか」をも問う [historical_linguistics][language_change][suppletion]

標題は,英語史を含め歴史言語学的研究を行なう際に常に気に留めておきたいポイントである.通常「歴史」とは変化の歴史のことを指すととらえられており,無変化や現状維持は考察するに値しないと目されている.無変化や現状維持は,いわば変化という絵が描かれる白いキャンバスにすぎない,という見方だ.

しかし,近年では,変化こそが常態であり,無変化こそが説明されるべきだという主張も聞かれるようになってきている.私としては,両方の見方のバランスをとって,変化にせよ無変化にせよ何かしら原因があると解釈しておくのが妥当だと考えている.

この問題と関連して,Fertig (9) による短いが説得力のある主張に耳を傾けよう.

Historical linguistics is commonly defined as 'the study of language change'. Some scholars do focus exclusively on changes and assume that if nothing changes, then there is nothing to account for. A large and growing number of scholars, however, recognize that lack of change can sometimes be just as remarkable and worthy of investigation as change (Milroy 1992; Nichols 2003). An obvious example from morphology is the apparent resistance of analogical change in certain highly irregular paradigms, such as English good--better--best; have--has--had; bring--brought; child--children, etc. . . . This all suggests that we should define historical linguistics as the study of language history rather than of (only) language change.

「なぜ変化しなかったか」を真剣に問うた論者の1人が,引用中にも言及されている社会言語学者 Milroy である.この Milroy の洞察との関連で書いてきた記事として「#2115. 言語維持と言語変化への抵抗」 ([2015-02-10-1]),「#2208. 英語の動詞に未来形の屈折がないのはなぜか?」 ([2015-05-14-1]),「#2220. 中英語の中部・北部方言で語頭摩擦音有声化が起こらなかった理由」 ([2015-05-26-1]),「#2574. 「常に変異があり,常に変化が起こっている」」 ([2016-05-14-1]) を挙げておきたい.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

・ Milroy, James. Linguistic Variation and Change: On the Historical Sociolinguistics of English. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

・ Nichols, Johanna. "Diversity and Stability in Language." Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Ed. Brian D. Joseph and Richard D. Janda. Oxford: Blackwell, 283--310.

2020-11-21 Sat

■ #4226. 言語変化と通時的対応関係 [language_change][diachrony][historical_linguistics][terminology][etymology][oe_dialect]

Fertig (7) に "Change vs. diachronic correspondence" と題する節をみつけた.この2つは歴史言語学において区別すべき重要な概念である.この区別を意識していないと,思わぬ誤解に陥ることがある.

Linguists often use 'change' to refer to correspondences among forms that may be separated by centuries or millennia, e.g. Old English stān and Modern English stone or Middle English holp and Modern English helped. For purposes of comparative reconstruction, diachronic correspondences that relate forms separated by hundreds of years may be just what one needs, but such correspondences often mask a complex sequence of smaller developments that may have taken a very circuitous route. Linguists who are serious about understanding how change actually happens often point to the fallacies that arise from treating diachronic correspondences as if they directly reflected individual changes. Where plentiful data allows us to examine the course of a change in fine-grained detail, the picture that emerges is often very different from what we would posit if we only had evidence of the 'before' and 'after' states . . . .

異なる2つの時点において(主として形式について)対応関係が認められる1組の言語項があるとき,その2つの言語項は何らかの通時的な線で結びつけられて然るべきである.この通時的な線こそが,その言語項が遂げた変化の実態である.しかし,時間に沿ってよほど細かな証拠が得られない限り,その線が直線なのか曲線なのか,曲線であればどんな形状の曲線なのか,分からないことが多い.その過程を慎重に推測し,せいぜい点線でつなげることができれば及第点であり,厳密に実線で描けるという幸運な状況は稀のように思われる.否,根本的な問いとして,最初に対応関係を認めた2つの言語項が,本当に対応関係があるものとみなしてよいのか,というところから議論しなければならないかもしれないのである.

具体例を1つ挙げよう.現代標準英語には「古い」を意味する old という語がある.一方,古英語にも同義の eald という語が確認される.千年の時間の隔たりはあるものの,意味や用法はほぼ一致しており,形式的にも十分に近似しているため,この2つの言語項の間に通時的対応関係が認められるとは言えそうだ.しかし,通時的対応関係を認めたとしても,音変化を通じて直線的に eald → old へと発展したと結論づけるのは早計である.丁寧に音変化を考察すれば分かるが,eald は古英語ウェストサクソン方言における形態であり,現代標準英語の old という形態の直接の祖先ではないからだ.むしろ古英語アングリア方言の ald に遡るとみるべきである.だとすれば,eald と old の関係は,直接的でも直線的でもないことになる.ald と old がなす直接的・直線的な関係に対して,eald が初期の部分で斜めに絡んできている,というのが正しい解釈となる.

点と点を結ぶ線(直線か曲線か)に関して,「点と点」の部分が通時的対応関係を指し,「線」の部分が言語変化を指すと考えておけばよい.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

2020-10-13 Tue

■ #4187. Meillet が重視した意味変化の社会語用論的側面 [semantic_change][sociolinguistics][register][semantic_borrowing][language_change]

「#4183. 「記号のシニフィエ充填原理」」 ([2020-10-09-1]) で引用した Meillet は,その重要論文において,意味変化 (semantic_change) に関する社会言語学な原理を強調している.単語は社会集団ごとに用いられ方が異なるものであり,その単語の意味も社会集団ごとの関心に沿って変化や変異することを免れない.そのようにして各社会集団で生じた新たな意味のいくつかが,元の社会集団へ戻されるとき,元の社会集団の立場からみれば,その単語のオリジナルの意味に,新しい意味が付け加わったようにみえるだろう.つまり,そこで実際に起こっていることは,意味変化そのものではなく,他の社会集団からの意味借用 (semantic_borrowing) なのだ,という洞察である.

Meillet は,先行研究を見渡しても意味変化の確かな原理というものを見出すことはできないが,1つそれに近いものを挙げるとすれば上記の事実だろうと自信を示している.この「社会集団」を「言語が用いられる環境」として緩く解釈すれば,語の意味変化は,異なる意味が異なる使用域 (register) 間で移動することによって生じるものと理解することができる.これは,意味変化を社会語用論的な立場からみたものにほかならない.Meillet (27) が力説している部分を引用しておこう.

Il apparaît ainsi que le principe essentiel du changement de sens est dans l'existence de groupements sociaux à l'intérieur du milieu où une langue est parlée, c'est-à-dire dans un fait de structure sociale. Il serait assurément chimérique de prétendre expliquer dès maintenant toutes les transformations de sense par ce principe: un grand nombre de faits résisteraient et ne se laisseraient interpréter qu'à l'aide de suppositions arbitraires et souvent forcées; l'histoire des mots n'est pas assez faite pour qu'on puisse, sur aucun domaine, tenter d'épuiser tous les cas et démontrer qu'ils se ramènent sans aucun reste au principe invoqué, ce qui serait le seul procédé de preuve théoriquement possible; le plus souvent même ce n'est que par hypothèse qu'on peut tracer la courbe qu'a suivie le sens d'un mot en se transformant. Mais, s'il est vrai qu'un changement de sens ne puisse pas avoir lieu sans être provoqué par une action définie --- et c'est le postulat nécessaire de toute théorie solide en sémantique ---, le principe invoqué ici est le seul principe connu et imaginable dont l'intervention soit assez puissante pour rendre compte de la pluplart des faits observés; et d'autre part l'hypothèse se vérifie là où les circonstances permettent de suivre les faits de près.

Meillet の上記の考え方については,「#1973. Meillet の意味変化の3つの原因」 ([2014-09-21-1]) でも指摘した.また,関連する議論として「#2246. Meillet の "tout se tient" --- 社会における言語」 ([2015-06-21-1]),「#2161. 社会構造の変化は言語構造に直接は反映しない」 ([2015-03-28-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Meillet, Antoine. "Comment les mots changent de sens." Année sociologique 9 (1906). 1921 ed. Rpt. Dodo P, 2009.

2020-09-08 Tue

■ #4152. アメリカ英語の -our から -or へのシフト --- Webster の影響は限定的? [webster][ame][spelling_reform][spelling][standardisation][prescriptivism][language_change]

昨日の記事「#4151. 標準化と規範化の関係」 ([2020-09-07-1]) で引用した文章のなかに,Anson からの引用が埋め込まれていた.Anson 論文は,アメリカ英語における color, humor, valor, honor などの -or 綴字の発展と定着の歴史を実証的に調査した研究である.1740--1840年にアメリカ北東部で発行された新聞からのランダムサンプルを用いた調査の結果が特に信頼に値する.イギリス英語綴字 -our に対するアメリカ英語綴字 -or の定着は,一般に Noah Webster (1758--1843) の功績とされることが多いが,事はそれほど簡単ではない.以下が,Anson (47) による調査報告のまとめの部分である.

Most obvious is the appearance of both -or and -our through the century, but gradual change can be detected from the -our extreme in 1740 to the -or extreme in 1840. Only small and sporadic change occurred around the time of Webster's strongest influence, which suggests that if he did contribute to the dropping of -u, his contribution was slow to take effect.

A key year appears to be 1830 --- after the appearance of Worcester's dictionary and the public attention, during the previous decade, to Webster's and Worcester's battle of dictionaries and spellers. . . .

On the whole, then, the American usage chart shows a slow but steady movement toward the -or spelling. No doubt the movement spilled at least into the first quarter of the twentieth century, when sporadic cases of -our were still to be seen. Aided by later dictionaries, which have looked to usage or other American authorities, the shift to -or is now virtually complete.

この調査報告を読むと,Webster (および彼と辞書編纂で争った Worcester)の当該語の綴字への影響は1830年以降に少し感じられはするが,決定的な影響というほどではなかったという.しかも -our から -or へのシフトの完成は,それから優に数十年も待たなければならなかったのである.Webster の役割は,せいぜいシフトの触媒としての役割にとどまっていたといえそうだ.

この事例研究から,Anson (48) は言語変化の標準化と規範化の関係に関する次の一般論を導き出そうとしている.

. . . usage and authority work mutually and each tends to influence the other and be influenced by it. A highly respected dictionary may influence the way an educated public spells debated words; on the other hand, no authority --- even Webster --- can hope to change a firmly entrenched spelling habit among the general public. The chances are good that, had the public not been moving steadily toward -or forms, we might still be spelling in favor of -our, despite Webster. While Webster may have served as a catalyst for some spelling changes, he was not, for spelling reform, the cause celebre many have assumed. Most of his reforms never caught on. Curiously, spelling reform on a large scale, like Esperanto and other synthetic languages, has never appealed to the public as have changes introduced organically and from within. Proponents of spelling reform argue quite convincingly that their proposals meet a real public need for simplicity, precision, and uniformity; yet often the public allows linguistic changes that work in just the opposite direction. Usage, then, is a highly resistant strain when it comes to 'curing the ills' of the language, and it ultimately determines its own future.

昨日の記事の趣旨に照らせば,この引用冒頭の "usage" を標準化と,"authority" を規範化と読み替えてもよいだろう.

・ Anson, Chris M. "Errours and Endeavors: A Case Study in American Orthography." International Journal of Lexicography 3 (1990): 35--63.

2020-03-11 Wed

■ #3971. 言語変化の multiple causation 再再考 [language_change][causation][multiple_causation]

標題については,「#3842. 言語変化の原因の複雑性と多様性」 ([2019-11-03-1]) に張ったリンク先の記事ですでに様々に論じてきたが,今ひとつ Fischer et al. (31) より,趣旨として関連する箇所を引用したい.昨今の言語変化研究において multiple_causation がトレンドであることが分かりやすく述べられている.

The current trend in theory formation is for this multifactorial view of causality to be formulated more and more explicitly. This is true both of models that accommodate multiple language-internal causes, typically with roots in the grammaticalization literature ..., and of models that seek to combine language-internal and language-external explanations of change ....

私がこれまで言語変化の "multiple causation" について主張してきたのは,引用の最後にあるように言語内的・外的な説明の合わせ技を念頭においてのことだった.しかし,なるほど,引用の半ばにあるように言語内的説明だけ取ってもそれは一枚岩ではなく礫岩的であるというという観点から "multiple" を考えることもできるし,その点でいえば引用で触れられていないが言語外的説明も "multiple" なはずだろう.どのレベルにおいても複合的な要因を前提として言語変化の解明に挑むというのが,昨今のトレンドといってよい.言語(変化)というきわめて複雑な現象を理解するためには,既存の知識を総動員し,さらに想像力を駆使しながら対象に挑むという姿勢が,ますます必要になってきているといえるだろう.

Fischer et al. (54) のバランスの取れた見方を示す1節を引用しておきたい.

Methodologically, it is most sound to give heed to and study quite a number of aspects of both an external and an internal kind, having to do with the type of contact, the socio-cultural make-up of the speech-community, and the state of the conventional internalized code that individuals in the community have developed during the period of language acquisition and beyond.

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow