2017-12-03 Sun

■ #3142. ホメオカオス (1) [chaos_theory][complex_system][language_change][variation]

言語体系がカオスと自己組織化を特徴とする複雑系であることについて,以下の記事で取り上げてきた(cf. 「#3111. カオス理論と言語変化 (1)」 ([2017-11-02-1]) ,「#3112. カオス理論と言語変化 (2)」 ([2017-11-03-1]),「#3122. 言語体系は「カオスの辺縁」にある」 ([2017-11-13-1]),「#3123. カオスとフラクタル」 ([2017-11-14-1]),「#3130. 複雑系言語学」 ([2017-11-21-1])).

言語の変化と変異を研究対象にしていると,言語に関わる現象のあまりの複雑さに圧倒される.どのように考えても解きにくいと悟った時,複雑系にすがる動機が生れる.見れば見るほど無秩序のようにみえて,それでも間違いなく何らかの秩序はあると直感するとき,それは複雑系に違いないという発想になる.静的な中心の欠如,動的な安定性の存在,結果としてバランスの保たれるアンバランス,秩序のなかの変化と変異.このような相矛盾する特徴が,気象や物理現象や生物や言語といった一筋縄では理解できない対象のうちに内在する.

『「複雑系」とは何か』を著わした吉永 (169) は,このような秩序を金子らに従って「ホメオカオス」という造語で呼んでいる.

部分秩序層で生成される秩序は,自己組織化という言葉から誤ってイメージされるような,静的な安定性ではない.多数の自由度をもつ弱いカオス的振動が,完全にそろうわけでもなく,かといって完全にばらばらになるわけでもなく,お互い影響し合い,依存し合いながら,つまり多様性を保持しながら――あるいは多様性をもつがゆえに――大筋ではあたかも基準となる状態があって,そこから逸脱しないかのようなふるまいをする,動的な安定状態である.

金子らはこの多様性を維持した安定性機構を「ホメオカオス homeochaos」と呼んでいる.いわゆるホメオスタシスが,理想的な静的安定性を想定し,そこから生じたゆらぎに対するゆり戻しのフィードバック機構と考えられてきたのに対し,ホメオカオスはそのような理想状態を仮想しなくてもいいことを教えてくれている.

さらに,このホメオカオスにおいて著しいのは,秩序の「次元」や「自由度」といった枠組みそのものが変化し,異なる枠組みへ飛躍することがあり得るということだ.これはオープンカオス(開放型カオス)と呼ばれる(吉永, pp. 169--70).

ホメオカオスがとくに重要になるのは,相空間の次元を決めるシステムそのものの自由度が変動するケースである.具体的には,要素的なユニットが互いの相互作用を経て分裂したり,また途中から消失したりする場合であり,たとえば細胞の増殖や死など,自然界の大半のシステムはこうした自由度の変動を許す開いたシステムになっている.

自由度が固定された,したがって相空間の次元が不変に保たれた閉じたシステムに見られる通常のカオスでは,相空間の中での軌道が不安定になって伸ばされていくと,どこかで折りたたまれる.相空間そのものが変わることはない.ところが,自由度が変動する開いたシステムでは,不安定性が増大していって運動が不規則になると,そこで自由度のジャンプが起こることがある.そして,新たに出現した余分な自由度に不安定さが分配されると,そこで生じた大自由度の弱いカオス状態にホメオカオスの機構が働いて,多様性を維持した安定性が生成される.このような開いたシステムに特有なカオスのダイナミクスを金子らは「開放型カオス」と呼んでいる.

システムをシステムとして維持するための動的な機構が提案されるのであれば,それは言語にも適用できる可能性が高いだろう.それくらい言語は動的で複雑である.

・ 吉永 良正 『「複雑系」とは何か』 講談社〈講談社現代新書〉,1996年.

・ 金子 邦彦,津田 一郎 『複雑系のカオス的シナリオ』 朝倉書店,1996年.

2017-11-24 Fri

■ #3133. 言語変化の "how" と "why" [causation][language_change][how_and_why]

言語変化の "why" は,歴史言語学において究極の問いである.その答えに少しでも近づくためには,その他の4W1Hの問いへの答えを着実に積み重ねていくよりほかない.それでも "why" に完璧にたどり着くのはほとんど不可能であり,せいぜい "how" を明らかにするのが関の山である.その "how" の答えですら,仮説の域を出ないことも多いだろう.

本ブログでも,言語変化の how_and_why については,「#784. 歴史言語学は abductive discipline」 ([2011-06-20-1]),「#2255. 言語変化の原因を追究する価値について」 ([2015-06-30-1]),「#2123. 言語変化の切り口」 ([2015-02-18-1]) などで扱ってきた.

昨日の記事「#3130. 複雑系言語学」 ([2017-11-21-1]) で紹介した Kretzschmar (251--52) は,複雑系の理論を用いて言語変化(具体的にはアメリカ英語の諸変種の生起という問題)に迫ることにより,"why" の問いには答えられないとしても,"how" の問いに対しては有効な答えを与えることができると自信を示している.

We cannot answer the question "why" American English is as it is --- there is never a good answer to the "why" question in linguistics --- but it is now possible to address more adequately the question "how" it came to be as it is.

Kretzschmar の言葉遣いによると,ある言語現象を共時的に説明しようとする際の問いが "why" で,通時的・歴史的に説明しようとする際の問いが "how" であるようにも感じられる.あるいは,言語変化の原因を問うのが "why" で,言語変化の型を問うのが "how" であると述べているようにも聞こえる.

論者によって "how" と "why" という疑問詞によって何を指すのかはおおいに異なり得るということを認めた上で,私も言語変化の how_and_why にこだわり続けていきたい.

・ Kretzschmar, William A., Jr. "Complex Systems in the History of American English." Chapter 4 of Developments in English: Expanding Electronic Evidence. Ed. Irma Taavitsainen, Merja Kytö, Claudia Claridge, and Jeremy Smith. Cambridge, 2015. 251--64.

2017-11-21 Tue

■ #3130. 複雑系言語学 [chaos_theory][complex_system][variety][zipfs_law][language_change][contact][methodology]

Kretzschmar は,言語を複雑系としてとらえ,言語変化を論じる研究者である.最近の論文で,複雑系の概念を用いて,アメリカ英語の諸変種がいかにして生じてきたかという問題を論じている.論文の冒頭 (251) で,発話を複雑系としてとらえる見方が端的に述べられている.

. . . language in use, speech as opposed to linguistic systems as usually described by linguists, satisfies the conditions for complex systems as defined in sciences such as physics, evolutionary biology, and economics . . . .

言語は複雑系とみなされるべき2つの特徴,すなわち "non-linear distribution" と "scaling" を備えているという (253) .前者 "non-linear distribution" は,具体的にいえば,漸近双曲線 (A-curve) の分布を指している.例としてすぐに思い浮かぶのは,「#1103. GSL による Zipf's law の検証」 ([2012-05-04-1]) や「#1101. Zipf's law」 ([2012-05-02-1]) で紹介した zipfs_law のグラフである.少数の高頻度語と多数の低頻度語により,右下へ長い尾を引くグラフが描かれる.Kretzschmar は,言語に関わる他の現象でもこのようなグラフが得られると主張する.

「言語=複雑系」に関するもう1つの特徴である "scaling" は,A-curve のような分布が言語の異なるレベルにおいて繰り返し現われる状況を指している.アメリカ東部諸州における方言単語(訛語)の頻度調査で,各形態について頻度順位の高い順に並べて頻度をプロットしていくと A-curve となるが,New York 州に限って同様のグラフを作成しても類似した曲線が得られるし,女性話者に限ったグラフでもやはり同様の曲線が得られるという (255) .

グラフが非線形でありスケール・フリーということになれば,当然ながら「#3123. カオスとフラクタル」 ([2017-11-14-1]) が想起される.関連して,「#3111. カオス理論と言語変化 (1)」 ([2017-11-02-1]),「#3112. カオス理論と言語変化 (2)」 ([2017-11-03-1]),「#3122. 言語体系は「カオスの辺縁」にある」 ([2017-11-13-1]) も参照されたい.

Kretzschmar (263--64) は論文の最後で,言語変種の生起・拡大を説明するのに複雑系の考え方が有用であると結論づけ,複雑系言語学を唱える.

Complexity science is the model that can cope successfully with the problems of language variation and change that we are interested in solving for the history of American English. Complexity science addresses the emergence of a new American variety, along with its component regional varieties, more adequately than traditional approaches. Complex systems replace the notion of monolithic "language contact" or Fischer's "cultural shift" with interaction between speakers. Complex systems can deal with the extension of existing varieties into new areas, and still account for the evident acquisition of new variants from important cultural groups in different areas. Finally, complex systems can cope with contemporary American cultural change and attendant language change, again without recourse to monolithic thinking. We are just at the beginning of research to understand the operation of the complex system of speech, but it is already clear that it gives us a good way to describe how the process of emergence and change really works.

従来のような "monolithic" な言語接触に基づいた理論ではなく,それを内に含み込むような複雑系の理論こそが,これからの言語変化研究を支えていくのではないかというわけだ.確かに刺激的な話題である.

・ Kretzschmar, William A., Jr. "Complex Systems in the History of American English." Chapter 4 of Developments in English: Expanding Electronic Evidence. Ed. Irma Taavitsainen, Merja Kytö, Claudia Claridge, and Jeremy Smith. Cambridge, 2015. 251--64.

2017-11-13 Mon

■ #3122. 言語体系は「カオスの辺縁」にある [chaos_theory][language_change][invisible_hand][complex_system]

『カオス的世界像』の著者スチュアート (481--82) によると,カオスについて興味深いことは,カオスと秩序との境目に近い「カオスの辺縁」において,ただならぬ何かが起こっているということである.

複雑性はカオスの概念の上に築かれるものである.実際,複雑性理論にうるさくつきまとう基本語――あるいはより正確には慣用句――は「カオスのふち(辺縁)」という語句である.カチカチと規則正しく時を刻む,歯車でできた時計仕掛の宇宙のように,いくつかのシステムは非常に単純な仕方でふるまう.しかし,カオス現象を示すシステムはもっとずっと複雑な仕方でふるまう.その極端な例として,気体分子の全体としてのランダムな運動がある.その中間にあるシステムは,もっと興味深い類のふるまい――複雑ではあるがパターンを暗示するようなふるまい――を示す.これらの複雑ではあるが組織化されたシステムは,まさに秩序とカオスの間の遷移状態にあるように見える――そして,それこそが「カオスの辺縁」なのである.ここで示唆されるのは,淘汰(選択)あるいは学習によってシステムがこの境域に行きつくということである.あまりに単純なシステムは,競合的環境のなかでは生き残れない.なぜなら,より複雑微妙なシステムはそれらの規則性を食い物にすることによって単純なシステムを出し抜けるからである.(もしもある現金輸送会社の車が,毎週金曜日の午前十時に銀行からお金を受け取り,正確に同じルートを通って輸送するとしたら,強盗はいとも簡単に現金強奪劇を演ずることができるだろう.)まったくランダムなシステムもまた,生き残らないだろう.なぜならそういうシステムは,秩序のある(コヒーレントな)ことは何もなし遂げられないからである.(もしも現金輸送車がまったくランダムなルートをとるとしたら,銀行に到着するまでに時間があまりにかかりすぎ,到着する前にその仕事は別の会社に奪われてしまうだろう.)だから,生き残るという点では,全体としての構造を失ってしなわない程度にできるかぎり複雑化するのが利益になるのである.進化するシステムは,カオスの辺縁にとどまるよう強いられているのである.

言語体系も,環境の変化に柔軟に適応する体系である.言語変異や言語接触は「カオスの辺縁」ととらえることができ,まさにそこで最もおもしろい現象が繰り広げられている.言語は,生き残りに成功してきた,単純すぎも複雑すぎもしない1つのシステムなのである.

関連して,「#3111. カオス理論と言語変化 (1)」 ([2017-11-02-1]),「#3112. カオス理論と言語変化 (2)」 ([2017-11-03-1]) も参照.

・ スチュアート,イアン(著),須田 不二夫・三村 和男(訳) 『カオス的世界像 非定形の理論から複雑系の科学へ』 白揚社,1998年.

2017-11-03 Fri

■ #3112. カオス理論と言語変化 (2) [chaos_theory][language_change][teleology][invisible_hand][complex_system]

昨日の記事 ([2017-11-02-1]) に引き続いての話題.カオス理論と言語変化の接点に注目した英語史研究者に Smith がいる.Smith (194) は,言語変化について次のように述べている.

Change . . . is the result of the complex interaction of extralinguistic and intralinguistic developments, and any resulting change itself interacts with further developments to produce yet more change. The conception is therefore a dynamic one . . . .

Smith (195) は,上のように述べた後で,このような多様な側面をもつ言語変化を「カオス理論」で説明され得る現象として提示している.

Such a multifarious conception of language change . . . seems to correspond to the most recent paradigm in both the natural and human sciences: 'chaos-theory'. Chaos-theory is really about order, about the way in which order results from complex interaction. The best-known popular example of this process --- the butterfly stamping in the forest causing a storm a thousand miles away --- is really about how a tiny innovation can make a difference, by interacting with other innovations to produce a snowball effect. If language is a metastable system deployed by interacting innovative and conservative language-users, it does not, in a chaotic world, require or imply some divine plan or overall grand design. Rather, living languages are the result of what Dawkins has called a 'blind watchmaker' effect, whereby order comes out of chaos.

Such an approach is hardly revolutionary, and . . . no claims of special newness are made here.

Smith は,言語変化を,言語に関与する種々の要素の "complex interaction" のたまものとしてとらえている.Smith の言語変化観については,「#1123. 言語変化の原因と歴史言語学」 ([2012-05-24-1]),「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1]),「#1928. Smith による言語レベルの階層モデルと動的モデル」 ([2014-08-07-1]) を参照.上の引用にもある "blind watchmaker" の比喩と関連して,teleology や invisible_hand の記事もどうぞ.

・ Smith, Jeremy J. An Historical Study of English: Function, Form and Change. London: Routledge, 1996.

2017-11-02 Thu

■ #3111. カオス理論と言語変化 (1) [chaos_theory][language_change][complex_system]

1960年代より,カオス理論 (chaos_theory) は「時計じかけの宇宙」観に代わる自然科学のパラダイムとして受け入れられてきたのみならず,社会科学その他の領域へも応用されてきた.それは,気象学,物理学,天文学,数学に始まり,生物学,経済学,社会学にまで裾野を広げている.例えば,気象現象,流体力学,幾何学,生物の個体数の増加速度,立ち上る煙の振る舞い,綿花の価格などがカオス理論で説明されるといわれ,ほかには実用的なところでCGの描画にも活用されている.

カオス理論は,その名前とは裏腹に,実は秩序に関する理論である.一見ランダムで予測できない現象にも,ある種の傾向が見られると主張する.また,カオス理論は,初期条件が僅かに異なるだけでも,その後の振る舞いに甚大な影響が及ぼされる点を指摘する.その最も有名な例がバタフライ効果 (butterfly effect) だろう.『サイエンス大図鑑 コンパクト版』 (351) によれば,バタフライ効果とは,

カオス系の主な特徴である「初期条件に大きく左右される性質」を表現するために,エドワード・ローレンツが考案した用語.初期条件の変更がたとえわずかであっても,現象が何度も繰り返されるうちに,大きな差が生じてしまうことを示す.ローレンツは「蝶(バタフライ)がブラジルで羽ばたくと,テキサスで竜巻が起こる」と表現した.彼のデータから描かれたモデル“ローレンツ・アトラクタ”は,偶然にも蝶の形をしている.カオス的な現象の進行を示すこのモデルでは,突然,進行方向が逆転し,同じ軌跡は2度と通らない.

"Lorenz' attractor" と呼ばれる蝶を彷彿とさせるこの3次元のグラフは,天候の軌跡を表現している.開始点の座標がたとえ僅かでも異なると,軌道が大きく逸脱し,異なる羽形の領域(各々穏やかな天候と荒れた天候を表わす)へ帰着するという.

初期条件の僅かな異なりが後に甚大な差異をもたらす現象を,数学の簡単な例で確かめることができる.A を定数(ここでは A = 2 とおく)とし,x0 を0から1の間をとるものとする(ここでは x0 = 0.9 とおく).このとき,x1 を Ax0(1 - x0) と定義すれば,x1 = 2 * 0.9 * (1 - 0.9) = 0.18 となる.同様に,x2 = Ax1(1 - x1) = 2 * 0.18 * (1 - 0.18) = 0.2952 とし,このサイクルを繰り返して,x0 から xn までの数列を得る.結果は,0.09, 0.18, 0.2952, 0.4161, 0.4859, 0.4996, 0.5000, 0.5000, ... となり,0.5000で安定する.A の値を2から3まで大きくしても,安定期に入るまでのサイクル数は増えるものの,最終的には安定する.これは,振り子が多少乱されても,最終的には揺れが安定してくることになぞらえられる.

ところが,A が3を超えると,2つの数を行き来する関係に至るなど予期できない振る舞いを示すようになる.そして,A が3.57程度になると,いつまでたっても定期性を示さない状態,すなわちカオスの状態に帰結する.例えば,A を3.7とおき,初期値の x0 を 0.9 と置いた場合と,僅かに異なる 0.9000009 と置いた場合の数列を得てグラフをプロットすると,以下のように興味深い結果が得られる.

35サイクルまでは2つのグラフは事実上重なっているが,以降40サイクルくらいまでにある種の安定的な分岐を示すようになり,その後は互いに無関係のカオス的な様相を呈する.すべては,初期値の僅かな差に由来するのだ.見方を変えれば,種々の初期条件がほぼ一致していたとしても,ある1つの条件において0.000009ほどの差があれば,後にたどる運命を天と地ほどまで違えるのに十分であるということになる.

カオス理論は,「環境」が関与するありとあらゆる分野に適用されることが明らかになってきている.言語とその変化も「環境」のなかで作用しているものであるから,当然,カオス理論と無縁ではない.例えば,拙著『英語の「なぜ?」に答える はじめての英語史』の「3.5.2 -e の衰退の一波万波」で示したとおり,英語史における屈折語尾の弱化という調音の僅かな変化が引き金となって,英語の統語論ががらんと組み替えられた事例が,カオス理論のバタフライ効果に対応するだろうか.言語も,「一波動けば万波生ず」なのである.

明日の記事でも,引き続きカオス理論の話題を扱う.

・ デイヴィス,アダム・ハート(総監修),日暮 雅通(監訳) 『サイエンス大図鑑 コンパクト版』 河出書房新社,2014年.

・ 堀田 隆一 『英語の「なぜ?」に答えるはじめての英語史』 研究社,2016年.

2017-08-09 Wed

■ #3026. 歴史における How と Why [historiography][history][causation][language_change][methodology][prediction_of_language_change]

歴史言語学は言語変化を扱う分野だが,なぜ言語は変化するのかという原因 (causation) を探究するという営みについては様々な立場がある.本ブログでも言語変化 (language_change) の「原因」「要因」「駆動力」を様々に論じてきたが,「なぜ」に対する答えはそもそも存在するのだろうかという疑念が常につきまとっている.仮に与えられた答えらしきものは,言語変化の「なぜ」 (Why?) に対する答えではなく,「どのように」 (How?) に対する答えにすぎないのではないか,と.言語変化の How と Why については,「#2123. 言語変化の切り口」 ([2015-02-18-1]) と「#2255. 言語変化の原因を追究する価値について」 ([2015-06-30-1]) で別々の問いであるかのように扱ってきたが,この2つの問いはどのような関係にあるのだろうか.

連日参照している Harari (265--66) は,歴史学の立場からこの問題を論じており,Why に対する How の重要性を説いている.

What is the difference between describing 'how' and explaining 'why'? To describe 'how' means to reconstruct the series of specific events that led from one point to another. To explain 'why' means to find causal connections that account for the occurrence of this particular series of events to the exclusion of all others.

Some scholars do indeed provide deterministic explanations of events such as the rise of Christianity. They attempt to reduce human history to the workings of biological, ecological or economic forces. They argue that there was something about the geography, genetics or economy of the Roman Mediterranean that made the rise of a monotheist religion inevitable. Yet most historians tend to be sceptical of such deterministic theories. This is one of the distinguishing marks of history as an academic discipline --- the better you know a particular historical period, the harder it becomes to explain why things happened one way and not another. Those who have only a superficial knowledge of a certain period tend to focus only on the possibility that was eventually realised. They offer a just-so story to explain with hindsight why that outcome was inevitable. Those more deeply informed about the period are much more cognisant of the roads not taken.

では,歴史の Why ではなく How に踏みとどまざるを得ない歴史学とは何のためにあるのか.Harari (48) は解放感のある次のような言葉で言い切る.

So why study history? Unlike physics or economics, history is not a means for making accurate predictions. We study history not to know the future but to widen our horizons, to understand that our present situation is neither natural nor inevitable, and that we consequently have many more possibilities before us than we imagine. For example, studying how Europeans came to dominate Africans enables us to realise that there is nothing natural or inevitable about the racial hierarchy, and that the world might well be arranged differently.

未来予測が歴史学の目的ではない.同じように,言語変化を扱う歴史言語学も,言語の未来予測を目的としていない.

言語の予測可能性については,「#843. 言語変化の予言の根拠」 ([2011-08-18-1]),「#844. 言語変化を予想することは危険か否か」 ([2011-08-19-1]),「#1019. 言語変化の予測について再考」 ([2012-02-10-1]),「#2154. 言語変化の予測不可能性」 ([2015-03-21-1]),「#2273. 言語変化の予測可能性について再々考」 ([2015-07-18-1]) をはじめとする (prediction_of_language_change) の記事を参照されたい.

・ Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. 2011. London: Harvill Secker, 2014.

2017-07-29 Sat

■ #3015. 後期近代英語への関心の高まり (2) [lmode][history_of_linguistics][language_change][sociolinguistics][gender][world_englishes][variety]

「#2993. 後期近代英語への関心の高まり」 ([2017-07-07-1]) で,近年,後期近代英語期の研究が盛り上がってきていることに触れた.その理由は様々に説明できるように思われるが,Kytö et al. (4--5) の指摘している4点に耳を傾けよう.19世紀の英語が研究に値する理由として,先の記事で触れたものと合わせて確認しておきたい.

(1) 19世紀中に識字率が上がったことにより,多種多様なテキストが豊富に生み出された.とりわけ性差と言語変化の関係がよく調査できるようになった.

(2) Brown Family のような現代英語のコーパスによる研究の成果として,数十年ほどの短期間における言語変化に注目が集まった.ここから,後期近代英語期の社会的・政治的な出来事と,当時の言語変化の関係を探る研究が試みられるようになった.

(3) この時期にジャンルの広がりが見られた.特に,私信,新聞,小説,科学の言説など,現代にかけて重要性を増すことになる諸ジャンルが開拓された時期として重要である.

(4) 19世紀は,イギリス以外の英語変種の多くにとって形成期に相当する.

いずれの項目も,後期近代英語期に特有の特殊な歴史事情を反映していることはいうまでもないが,それ以上に近年のコーパス言語学,社会言語学,語用論といったアプローチが興隆してきた学史的な背景と連動していることが重要である.もとより歴史的な分野であるとはいえ,いま歴史のどの側面に関心を寄せやすいのか,関心があるのかという現在的な動機こそが,歴史研究を駆動していくものだとわかる.

・ Kytö, Merja, Mats Rydén, and Erik Smitterberg. "Introduction: Exploring Nineteenth-Century English --- Past and Present Perspective." Nineteenth-Century English: Stability and Change. Ed. Merja Kytö, Mats Rydén, and Erik Smitterberg. Cambridge: CUP, 2006. 1--16.

2017-07-17 Mon

■ #3003. 英語史が近代英語期で止まってしまったかのように見える理由 (4) [lmode][historiography][language_change][speed_of_change][phonetics][sound_change][variety][contact]

昨日の記事 ([2017-07-16-1]) に引き続き,標題の第4弾.後期近代英語期に対する関心と注目が本格的に増してきたのは,「#2993. 後期近代英語への関心の高まり」 ([2017-07-07-1]) で見たとおり,今世紀に入ってからといっても過言ではない.しかし,それ以前にもこの時代に関心を寄せる個々の研究者はいた.早いところでは,英語史の名著の1つを著わした Strang も,少なからぬ関心をもって後期近代英語期を記述した.Strang は,この時代に体系的な音変化が生じていない点を指摘し,同時代が軽視されてきた一因だとしながらも,だからといって語るべき変化がないということにはならないと論じている.

Some short histories of English give the impression that changes in pronunciation stopped dead in the 18c, a development which would be quite inexplicable for a language in everyday use. It is true that the sweeping systematic changes we can detect in earlier periods are missing, but the amount of change is no less. Rather, its location has changed: in the past two hundred years changes in pronunciation are predominantly due, not, as in the past, to evolution of the system, but to what, in a very broad sense, we may call the interplay of different varieties, and to the complex analogical relationship between different parts of the language. (78--79)

(音)変化の現場が変わった,という言い方がおもしろい.では,現場はどこに移動したかといえば,変種間の接触という社会言語学的な領域であり,体系内の複雑な類推作用という領域だという.

ここで Strang に質問できるならば,では,中世や初期近代における言語変化は,このような領域と無縁だったのか,と問いたい.おそらく無縁ということはなく,かつても後期近代と同様に,変種間の相互作用や体系内の類推作用はおおいに関与していただろう.ただ異なるのは,かつての時代の言語を巡る情報は後期近代英語期よりもアクセスしにくく,本来の複雑さも見えにくいということではないか.後期近代英語期は,ある程度の社会言語学的な状況も復元することができてしまうがゆえに,問題の複雑さも実感しやすいということだろう.解像度が高いだけに汚れが目立つ,とでも言おうか.つまり,変化の現場が変わったというよりは,最初からあったにもかかわらず見えにくかった現場が,よく見えるようになってきたと表現するのが妥当かもしれない.もちろん,現代英語期については,なおさらよく見えることは言うまでもない.

・ Strang, Barbara M. H. A History of English. London: Methuen, 1970.

2017-07-16 Sun

■ #3002. 英語史が近代英語期で止まってしまったかのように見える理由 (3) [lmode][historiography][language_change][speed_of_change]

標題に関して「#319. 英語話者人口の銀杏の葉モデル」 ([2010-03-12-1]),「#339. 英語史が近代英語期で止まってしまったかのように見える理由」 ([2010-04-01-1]),「#386. 現代英語に起こっている変化は大きいか小さいか」 ([2010-05-18-1]),「#622. 現代英語の文法変化は統計的・文体的な問題」 ([2011-01-09-1]),「#1430. 英語史が近代英語期で止まってしまったかのように見える理由 (2)」 ([2013-03-27-1]) で取り上げてきたが,もう1つ議論の材料を追加したい.

近代英語末期から現代英語期にかけての時代を扱った Cambridge 英語史シリーズ第4巻の編者 Romaine は,序章でこの時代を次のように特徴づけている (1) .

The final decades of the eighteenth century provide the starting point for this volume --- a time when arguably less was happening to shape the structure of the English language than to shape attitudes towards it in a social climate that became increasingly prescriptive. . . . The most radical changes to English grammar had already taken place over the roughly one thousand years preceding the starting year of this volume.

この時期には,言語体系に影響するような変化はさほど起こっておらず,むしろ話者の態度における変化(主として規範主義的言語観の定着)が顕著に見られるのだという.言い換えれば,言語学的な変化というよりは社会言語学的な変化に特徴づけられる時代ということであり,歴史社会言語学的な側面がクローズアップされる時代ということになる.

この時期,特に文法の分野で大規模な変化として見るべきものがないことは,「#622. 現代英語の文法変化は統計的・文体的な問題」 ([2011-01-09-1]) で触れた通りだが,Romaine (2) も同じ趣旨で次のように論じている.

The immediately preceding period dealt with in Volume III (1476--1776) of this series, the Early Modern Period, has often been described as the formative period in the history of Modern Standard English. By the end of the seventeenth century what we might call the present-day 'core' grammar of Standard English was already firmly established. As pointed out by Denison in his chapter on syntax, relatively few categorical innovations or losses occurred. The syntactic changes during the period covered in this volume have been mainly statistical in nature, with certain construction types becoming more frequent.

もちろん,(後期)近代英語期に英語史の流れが本当に止まったわけではない.言語内的な変化は,先行する時代に比して確かに目立たないと言えそうだが,言語外的な変化は激しく生じている.英語史が内的な歴史(内面史)と外的な歴史(外面史)の和である以上,その流れが止まることは決してない.

・ Romaine, Suzanne. "Introduction." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 4. Cambridge: CUP, 1998. 1--56.

2017-06-28 Wed

■ #2984. なぜ英語史を学ぶか (5) [hel_education][language_change][variation]

標記の話題について,Crystal (296--97) は著書の終わりに近い部分で,説得力をもって次のように述べている.

It is no more than common sense for those who have invested a childhood, or adult time and money, in successfully acquiring the English language to maintain an active interest in the language's progress. The more we learn about where the language has been, how it is structured, how it is used, and how it is changing, the more we will be able to judge its present course and help to plan its future. For many people, this will indeed mean a conscious altering of attitude. Language variation and language change --- the two aspects of English which are at the centre of its identity, and which are most in the public eye --- are too often blindly condemned. If just a fraction of the nervous energy which is currently devoted to the criticism of split infinitives and the intrusive r were devoted to the constructive promotion of forward-looking language activities, what might not be achieved?

Crystal は,英語の変化と変異 (change and variation) を学ぶことにより,その現在をよりよく判断し,未来をよりよく計画することができると力説している.これが,英語の歴史を始め,構造,変異,使用を学ぶ意義だろう.現在,そして未来に向けて,英語とうまく付き合っていくための知識であり知恵となる.さらに,英語史を学ぶことは,母語を含めた言語一般に対する視野を広げ,寛容な態度を育てることにも貢献する.今後も,この分野のもつ大きな可能性を指摘し,説いていきたいと思っている.

関連して,「#24. なぜ英語史を学ぶか」 ([2009-05-22-1]),「#1199. なぜ英語史を学ぶか (2)」 ([2012-08-08-1]),「#1200. なぜ英語史を学ぶか (3)」 ([2012-08-09-1]),「#1367. なぜ英語史を学ぶか (4)」 ([2013-01-23-1]) も参照.

・ Crystal, David. The English Language. 2nd ed. London: Penguin, 2002.

2017-05-06 Sat

■ #2931. 新しきは古きを排除するのではなく選択肢を増やす [language_change][register][semantic_change][printing]

カーランスキー(著)『紙の世界史』を読んだ.紙の歴史については「#2465. 書写材料としての紙の歴史と特性」 ([2016-01-26-1]) でも扱ったが,密接に関連する印刷術のテクノロジーと合わせて,紙が人類の文明に偉大な貢献をなしたことは疑いようがない.

カーランスキーの紙の歴史の叙述は一級品だが,テクノロジーの歴史に関する一般的な原理の指摘も示唆に富んでいる (11) .

テクノロジーの歴史から学ぶべき重要なこと,一般に誤った推論がなされていることはほかにもある.新しいテクノロジーは古いテクノロジーを排除するというのがそのひとつだ.これはめったには起こらない.パピルスは紙が導入されてからも地中海沿岸を中心とする地域で何世紀も使われつづけた.羊皮紙はいまだに使われている.ガスや電気ストーブが発明されても暖炉がなくなることはなかった.印刷ができるようになっても人はペンで書くことをやめなかった.テレビはラジオを駆逐しなかった.映画は劇場をなくせなかった.ホームビデオも映画館をなくせなかった.が,今挙げたものはどれも誤った予測をたてられた.電卓がそろばんの使用を終わらせることさえできなかったのに.そして,商業的成功を約束された電球の特許がトーマス・エジソンに与えられた一八七九年から一世紀以上経った現在でも,アメリカ合衆国だけで四百社の蝋燭製造業者が存在し,およそ七千人の従業員を雇い,年間で二十億ドル以上を売り上げている.二十一世紀の最初の十年には蝋燭の売り上げが伸びたほどだ.むろん蝋燭の使い途は大きく変わったけれども.同様のことは羊皮紙の製造法や用途についても起こった.新たなテクノロジーは古いテクノロジーを排除するというより選択肢を増やすのだ.コンピュータはまちがいなく紙の役割を変えるだろうが,紙が消えることはけっしてない.

確かに,紙に印刷された書籍が現われたあとも長らく羊皮紙はとりわけ正式な文書にふさわしい素材だとみなされ続け,18世紀末のアメリカ独立宣言においても羊皮紙で書かれるべきことが説かれたほどである.

昨今,紙の書籍と電子書籍の競合についての議論が盛んだが,カーランスキー (461--62) は上記のテクノロジー観をさらに押し進めて,次のように述べる.

デジタル時代に消えてゆくであろうものを予測するまえに,口承文化が今も生き残っているということを思い出してみるのもいいだろう.新刊本の販売促進で最初におこなわれるイベントが著者による朗読会であったりするのは,人には耳で聞いたものを読みたくなる傾向があるからだろう.オーディオブックも人気となっている.

なるほど,古いテクノロジーは新しいテクノロジーにより置き換えられるというよりは,独特な機能を保持・獲得しつつ,存続してゆくことが多いものかもしれない.これは,ちょうど古い語が新しい語に置き換えられるのではなく,語義,用法,使用域を特化させてしぶとく生き残っていく様にも似ている.古きものは社会の一線からは退くかもしれないが,完全に廃棄されてしまうわけではなく,むしろ選択肢の一つとして積み重ねられていき,生活や表現のヴァリエーションを豊かにしていくものなのだろう.

・ マーク・カーランスキー(著),川副 智子(訳)『紙の世界史 歴史に突き動かされた技術』 徳間書店,2016年.

2017-04-02 Sun

■ #2897. 渋沢栄一の述べる「言語動作の感染性と伝播力」 [language_change][lexical_diffusion]

渋沢栄一と言語(学)はあまり結びつかないと思われるが,『論語と算盤』のなかの「習慣の感染性と伝播力」と題する節で,善事の習慣も悪事の習慣も人々に感染するものだから,よく気をつけなければならない,と説くくだりがある.そこで,「言語動作」も例外ではないとして,言語の伝播について,そして実質的には言語の変化について触れている (pp. 101--02) .

言語動作のごときは,甲の習慣が乙に伝わり,乙の習慣が丙に伝わるような例は,決して珍しくない.著しい例証を挙ぐれば,近来新聞紙上に折々新文字が見える.一日甲の新聞にその文字が登載されたかと思うと,それがたちまち乙丙丁の新聞に伝載され,遂には社会一般の言語として,誰しも怪しまぬことになる.かの「ハイカラ」とか「成金」とかいう言葉は,すなわちその一例である.婦女子の言葉などもやはり左様で,近頃の女学生が頻りに「よくッてよ」とか「そうだわ」とかいう類の言語を用いるのも,ある種の習慣が伝播したものといって差し支えない.また昔日は無かった「実業」という文字のごときも,今日は最早習慣となり,実業といえばただちに,商工業のことを思わせるようになって来た.かの「壮士」という文字なども,字面から見れば壮年の人でなければならぬ筈であるのに,今日では老人を指しても壮士といい,誰一人それを怪しむものなきに至っている.もって習慣が,如何に感染性と伝播力を持っているかを察知するに足るであろう.しかして,この事実より推測する時は,一人の習慣は終に天下の習慣となりかねまじき勢いであるから,習慣に対しては深い注意を払うとともに,また自重してもらわねばならぬのである.

当時の新語や言葉遣いの様子が分かっておもしろい.渋沢がこれらの新語に対して必ずしも好意的ではなかったように読めるが,いずれにせよ,それほど言葉も強い感染力と伝播力をもっているのだ,ということが説かれている.

また,言語が伝播するというよりは,言語動作が伝播するという言い方をしているのもおもしろい.言語そのものよりも,その話者に一歩近い立場から言語変化を見ていることになるだろうか.

「感染性」と「伝播力」と関連して,語彙拡散の諸問題について「#5. 豚インフルエンザの二次感染と語彙拡散の"take-off"」 ([2009-05-04-1]),「#1572. なぜ言語変化はS字曲線を描くと考えられるのか」 ([2013-08-16-1]),「#2299. 拡散の駆動力3点」 ([2015-08-13-1]) を含む lexical_diffusion の各記事を参照されたい.

・ 渋沢 栄一 『論語と算盤』 忠誠堂,1927年.KADOKAWA,2008年.

2017-03-10 Fri

■ #2874. 淘汰圧 [evolution][language_change][speed_of_change][functional_load][schedule_of_language_change][entropy]

進化生物学では,自然淘汰 (natural selection) と関連して淘汰圧 (selective pressure or evolutionary pressure) という概念がある.伊勢 (23) の説明を見てみよう.

自然淘汰の強さの度合いを表わすときに,淘汰圧 (selective pressure または evolutionary pressure) という言葉を使います.形質による適応度の違いが大きいとき,淘汰圧は高くなります.たとえば,環境が悪化して多くの個体が子孫を残さずに死に絶え,適応度の高いごく一部の個体だけが子孫を残して繁栄するような状況では,淘汰圧は高くなります.

淘汰圧が高いとき,進化は猛スピードで進みます.適応度は形質によって大きく異なるので,高い適応度を生む形質が自然淘汰で選ばれていき,適応度を下げる形質は急速に失われていきます.逆に,淘汰圧が低い状況では,形質が違ってもそれほど適応度に差が見られません.よって,世代を経ても形質の変化はあまり見られません.

伊勢は,例としてアルビノ化を挙げている.アルビノ化した個体はカモフラージュが苦手なので,一般に生存確率が下がる.つまり適応度を下げる形質なので,通常の淘汰圧の高い状況下では,失われていくことがほとんどである.ところが,真っ暗な洞窟など,カモフラージュすることが意味をもたない環境においては,淘汰圧は低いため,アルビノ化した個体が適応度の点で特に劣ることにはならない.洞窟においては,アルビノ化(の有無)は重要性をもたないのである.

さて,ここで言語の話題に移ろう.言語変化を,広い意味で言語をとりまく環境の変化に適応するための自然淘汰であると捉えるのであれば,言語における淘汰圧というものを考えることは有用だろう.淘汰圧が高い状況では,ちょっとした言語項の変異でも重要性を帯び,より適応度の高い変異体が選択される可能性が高い.一方,淘汰圧が低い状況では,それなりに目立つ変異であってもさほど重要性をもたないため,特定の変異体が勝ったり負けたりというような淘汰のプロセスへ進んでいかない.

では,言語において淘汰圧の高い状態や低い環境とは何だろうか.言語体系内での圧力と言語体系外の圧力に分けて考えることができる.前者については,構造言語学的な観点から機能負担量 (functional_load),対立の効率性,体系の対称性など,様々な考え方がある.後者については,社会言語学や語用論で取り上げられる話者間の相互作用や言語接触などが,特定の言語環境を用意する要素となる.

生物における淘汰圧が進化の速度にも関係するということは,言語についても当てはまりそうである.淘汰圧が高ければ,おそらく言語変化はスピーディに進むだろう.この点に関しては,エントロピー (entropy) という,もう1つの興味深い話題も想起される.「#1810. 変異のエントロピー」 ([2014-04-11-1]),「#1811. "The later a change begins, the sharper its slope becomes."」 ([2014-04-12-1]) の議論を参照されたい.

・ 伊勢 武史 『生物進化とはなにか?』 ベレ出版,2016年.

2017-03-03 Fri

■ #2867. 言語変化の偶然と必然 [language_change][causation][teleology][entropy][unidirectionality][spaghetti_junction][invisible_hand]

偶然(及びその対立項としての必然)とは何か,という問いは哲学上の問題だが,言語変化の原因を探る際にも避けて通るわけにはいかない.統計学者・確率論者である竹内による「偶然」に関する新書を読んでみた.

竹内は,「偶然の必然的産物」 (139) という表現に要約されているように,偶然と必然は対立する概念というよりは,むしろ組み合わさって現象を生じさせる連続的な動因であると考えている.例えば,生物進化について「突然変異の起こり方には方向性はないが,自然選択の圧力のもとで,その積み重ねには方向性が生じ」ると述べている (138) .突然変異自体はあくまで「偶然」だが,その偶然を体現したものが何だったのかによって,次の一歩の選択肢が狭まり,ある特定の選択肢が選ばれる確率が高まる.そのように何歩か進んでいくうちに,最終的には選択肢が1つに絞られ,確率が1,すなわち「必然」となる.完全なる「偶然」から出発しながらも,徐々に「方向」が絞られ,ついには「必然」へと連なる,というわけだ.

ある壺に白玉と黒玉を入れる2つの試行を考えてみよう.まず,第1の試行.壺には同数の白玉と黒玉が入っているとする.そこから無作為に1つを取り出し,白玉か黒玉かを記録し,壺に戻す,ということを繰り返す.いずれかの玉が出る確率は,大数の法則により1/2となることは自明である.では次に第2の試行.ここでは,無作為に1つ取り出した後に,それと同じ色のもう1つの玉を加えて壺に戻すということを繰り返してみる.最初の取り出しでいずれの色が出るかの確率は1/2だが,例えばたまたま白玉が出たとして,それを壺に戻す際には,もう1つの白玉も加えた上で戻すので,次の取り出しに際しての確率の計算式は,少しく白玉が有利な式へと変わるだろう.その若干の有利さゆえに実際に次の回に白玉が出たとすると,その次の回にはさらに白玉が有利となるだろう.回を重ねるごとに白玉の有利さは増し,最終的には白玉を取り出す確率は限りなく1に近づいていくはずである.最初は偶然だったものが,最後にはほぼ必然となってしまう例である.

2つの試行から,偶然の蓄積される方法に2種類あることが分かる.1つ目ではいつまでたっても1/2という確率は変わらず,むしろ偶然が純化されていくかのようだ.言い換えれば,エントロピーの増大,あるいは情報量の減少である.一方,2つ目は,最初の偶然により徐々にある方向に偏っていき,最終的に必然に近づいていく.これは,エントロピーの減少,あるいは情報量の増大といえるだろう.竹内 (74) は,次のように述べている.

宇宙のいろいろな局面において,「エントロピー増大の法則」と「情報量増大の法則」がともに働いていると思う.つまり,宇宙には必然性の枠に入らない偶然性というものが存在し,そうして偶然性には大数の法則を成り立たせるような,極限において完全な一様性をもたらす性質のものと,累積することによって情報として働き,一定の環境の下で新たな秩序を作り出すようなものとの二種類がある.前者の偶然性はエントロピーの増大をもたらすが,後者は情報量の増大をもたらすのである.より詳しくいえば,偶然に作り出された新しい秩序が情報システムによって捉えられることによって,安定し維持されることになるのである.

ある現象が偶然でもあり必然でもあるというのは一見すると矛盾しているが,このように考えれば調和する.この見方は,言語変化論にも多くの示唆を与えてくれる.例えば,言語変化の方向性に関する議論に,unidirectionality の問題や invisible_hand や spaghetti_junction と呼ばれる仮説がある(「#2531. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction"」 ([2016-04-01-1]),「#2533. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction" (2)」 ([2016-04-03-1]),「#2539. 「見えざる手」による言語変化の説明」 ([2016-04-09-1]) などを参照).また,言語におけるエントロピーの問題については entropy の各記事で扱ってきたので,そちらも参照.

・ 竹内 啓 『偶然とは何か――その積極的意味』 岩波書店〈岩波新書〉,2010年.

2017-02-27 Mon

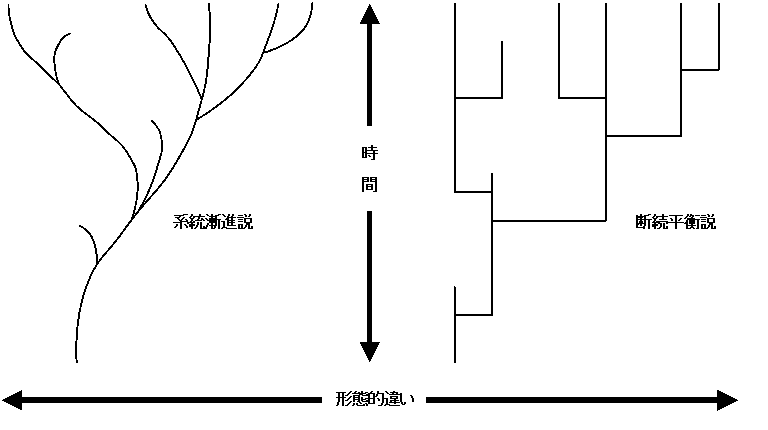

■ #2863. 種分化における「断続平衡説」と「系統漸進説」 [evolution][punctuated_equilibrium][origin_of_language][language_change][speed_of_change]

言語進化論や言語起源論は,しばしば進化生物学の仮説を参照する.言語の分化を説明するモデルとして生物の種分化に関するモデルが参考とされるが,後者では2種類の対立する仮説が立てられている.断続平衡説 (punctuated_equilibrium) と系統漸進説 (phyletic gradualism) である.バーナード・ウッドの人類進化の概説書より,種分化に関する解説を引用する (60--61).

ある研究者は,新しい種の誕生は集団全体がゆっくり変化することと考える.この解釈は「系統漸進説 (phyletic gradualism)」とよばれ,種分化は「アナゲネシス,漸進進化 (anagenesis)」によって起こると見なされる.ほかの研究者は,新しい種の誕生は地理的に隔離された一部の集団が急速に変化することと考える.この解釈は「断続平衡説 (punctuated equilibrium)」とよばれ,急速な変化と変化の間の期間には,特定の方向への変化は起こらず,無方向的な散歩(ふらつき (random walk))しか起こらないと見なされる.断続平衡説における種形成は「分岐進化 (cladogenesis)」とよばれ,種形成と種形成との間の形態的に安定した期間は停滞期 (stasis) と考える.ほぼすべての研究者は,進化における形態変化は種分化のときに起こると認識している.

これを図示すると,以下のようになる(ウッド,p. 61 を参考に).

いずれのモデルにおいても,種の誕生や分化がとりわけ盛んな時期があると想定されている.これは適応放散 (adaptative radiation) と呼ばれ,新環境が生じたときに起こることが多いとされる.

生物進化の比喩がどこまで言語進化に通用するものなのか,議論の余地はあるが,比較対照すると興味深い.関連して,「#807. 言語系統図と生物系統図の類似点と相違点」 ([2011-07-13-1]) も参照.とりわけ,言語の起源,進化,変化速度に関する断続平衡説の応用については,「#1397. 断続平衡モデル」 ([2013-02-22-1]),「#1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード」 ([2014-02-09-1]),「#1755. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード (2)」 ([2014-02-15-1]),「#2641. 言語変化の速度について再考」 ([2016-07-20-1]) を参照されたい.

・ バーナード・ウッド(著),馬場 悠男(訳) 『人類の進化――拡散と絶滅の歴史を探る』 丸善出版,2014年.

2017-02-10 Fri

■ #2846. 言語変化における「世代」 [language_change][kanji][semantic_change][generative_grammar][diachrony][semantic_change][polysemy]

2月6日の読売新聞朝刊のコーナー「翻訳語事情」に,generation の訳語としての「世代」について,解説があった.本来,「世代」という漢語は「年代」「時代」「代々」「世々代々」ほどの意味で使われていたが,明治後半の教科書などで生物学用語として遺伝的な意味での「世代」が広まっていったという.さらに,19--20世紀にドイツ人文学から「歴史的体験を共有する同年齢層の集団」を意味する用法が哲学,社会学,芸術,文学などにおいて広がった.とりわけカール・マンハイム (1893--1947) が社会学的見地から「世代」を考察したことで,その潮流を受けた日本においても,現代的な意味での「世代」が定着するようになった.

生物学的な「世代」と社会学的な「世代」とでは,形としては同じ単語であっても,大きな意味の差がある.前者は順に交替していくという意味での段階性を表わすのに対して,後者は同年齢層集団としての継続性が含意される.例えば「団塊の世代」の価値観は,時とともに構成員の年齢は上がっていくものの,それ自体は変化しないという点で継続性があるといえる.

しかし,解説者の斎藤希史氏によれば,両方の意味において共通しているのは,「世代という語には,世の中を輪切りにして,断絶を意識させる傾向がある」ということだ.だが,冒頭に述べた原義にたち帰れば,「世々代々」とは「世を重ねて未来へ続いていくイメージ」があった.つまり,「世代」と聞いて喚起するイメージは,「世代交替」よりは「世代間交流」のほうに近かった可能性がある.

「世代」に対する2つのイメージの差は,言語変化を考察するに当たっても示唆的である,生成文法の立場からは,言語変化とは文法変化のことであり,そこでは「世代交代」の発想が原則である.しかし,社会言語学的な立場から見れば,言語変化のイメージは「世代間交流」のほうに近いだろう.年上話者層と年下話者層では,確かに言葉遣いの平均値は異なっているだろうが,個々の話者を見れば,年下の言葉遣いの影響を受ける年上の人もいれば,その逆のケースもある.両話者層は,生まれた年代は異なるものの,現在を含むある幅の期間,(言語)生活を共有しているのだから,その共有の程度に応じて,多少なりとも存在している言語上の格差は薄められるだろう.言語変化は,世代交替によりカクカクと進んでいく側面もあるかもしれないが,世代間交流によりあくまで緩やかに進んでいくという部分が大きいのではないか.

Bloomfield の言語変化における「世代」の認識も,「#1352. コミュニケーション密度と通時態」 ([2013-01-08-1]) で見たように,「世代間交流」の発想に近かったように思われる.

2016-12-27 Tue

■ #2801. 発音器官の副次的性質と言語変化 [speech_organ][language_change][causation][phonetics][phonology][vowel]

ヒトの発音器官が二次的な派生物であることについて,「#544. ヒトの発音器官の進化と前適応理論」 ([2010-10-23-1]) でみた.この結果としてヒトの言語は様々な特徴,あるいは制限をもつに至ったと思われるが,音声変化や,さらには言語変化の普遍性も,ヒトの発音器官の生理的な特質と関連しているという見方がある.三輪 (15) は,マルティネの見解を次のように紹介している.

言語は常に均整のとれた体系へと変化する.しかし,人間の発音器官は,発音を第一次機能としてもつのではない.口,歯,舌,唇は食べ物を摂取し,咀嚼し,飲み込むためにできており,発音器官は,消化機能の上に,いわば,副次的機能としてあるにすぎない.したがって,口の中の器官は,食べ物の消化には都合よくできていても,発音に必ずしも都合よくできていない.発音器官としてみると不均衡にできており,均衡のとれた体系を目指す言語体系,特に母音・子音の体系とそれを実現に移す発音器官とは整合していない.そのことが普遍的な言語変化の要因であり,実際にしばしば発音の変化,言語の変化の原因となる.

調音音声学や生理学の視点に立てば,例えば母音をみれば分かるように,前舌系列と後舌系列は非対称的で不均衡である.「#19. 母音四辺形」 ([2009-05-17-1]) や「#118. 母音四辺形ならぬ母音六面体」 ([2009-08-23-1]) の図をみれば,口腔を横からみたときに,正方形や長方形ではなく台形(それすらも理想的な図示)である.ところが,音韻論的にいえば,例えば日本語のような5母音体系において,/i, e, a, o, u/ の各音素は左右対称の優美な三角形(あるいはV字形)の辺の上に配置されるのが普通である.理想は対称的,しかし現実は非対称的,という構図がここにある.

上の引用で主張されていることは,この理想と現実のズレこそが現実を変化させる原動力である,という説だ.この「理想」には,言語は対立の体系であるとするソシュール以来の構造主義的な言語観が色濃く反映されている.

・ 三輪 伸春 『ソシュールとサピアの言語思想 現代言語学を理解するために』 開拓社,2014年.

2016-12-13 Tue

■ #2787. アメリカ英語に "colonial lag" はあるか (4) [colonial_lag][language_change][speed_of_change]

アメリカ英語について古風な性質や保守性がしばしば指摘されるが,それはどこまで真実なのか.この問題について,「#1266. アメリカ英語に "colonial lag" はあるか (1)」 ([2012-10-14-1]),「#1267. アメリカ英語に "colonial lag" はあるか (2)」 ([2012-10-15-1]),「#1268. アメリカ英語に "colonial lag" はあるか (3)」 ([2012-10-16-1]),「#1304. アメリカ英語の「保守性」」 ([2012-11-21-1]),「#1738. 「アメリカ南部山中で話されるエリザベス朝の英語」の神話」 ([2014-01-29-1]) などの記事で考えてきた.

英語史の古典的名著を著わした Baugh and Cable (350) も,colonial_lag という用語こそ用いていないが,アメリカ英語に見られるこの特徴について論じている.「接ぎ木」の比喩がおもしろい.

. . . it has often been maintained that transplanting a language results in a sort of arrested development. The process has been compared to the transplanting of a tree. A certain time is required for the tree to take root, and growth is temporarily retarded. In language, this slower development is often regarded as a form of conservatism, and it is assumed as a general principle that the language of a new country is more conservative than the same language when it remains in the old habitat. In this theory there is doubtless an element of truth. . . . And it is a well-recognized fact in cultural history that isolated communities tend to preserve old customs and beliefs. To the extent, then, that new countries into which a language is carried are cut off from contact with the old, we may find them more tenacious of old habits of speech.

孤立した地域に古風な言語項が保存されるということは直観的にも理解できるだろう.実際に,「#430. 言語変化を阻害する要因」 ([2010-07-01-1]) で孤立したアイスランドの言語の例や,日本やヨーロッパからは,「#1045. 柳田国男の方言周圏論」 ([2012-03-07-1]) や「#1000. 古語は辺境に残る」 ([2012-01-22-1]) で取り上げた例に示される通りである.アメリカ植民においても,特に初期には新しい集落が互いに孤立してポツポツと点在していたのであり,そこでイギリス本国から持ち込まれた語法が変化せず,末永く保たれることになった,ということは十分にありそうである.

しかし Baugh and Cable は,この後,しばしば言われる「アメリカ英語の保守性」は無批判に受け入れることはできないだろうと慎重に議論を展開している.その議論は,至極まっとうである.アメリカ英語には "colonial lag" として説明できそうな古風な表現が多くあることは認めるにせよ,言語的革新もまた多く生じてきたのであり,一言で「古風」「保守的」と特徴づけて終わらせることはできない.

やはり "colonial lag" は多分に相対的な概念だと思う.ところで,なぜ「植民地の遅れ」と表現し「宗主国の進み」とは表現しないのだろうか.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2016-12-03 Sat

■ #2777. 語彙の14年周期説? [lexicology][language_change][speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][n-gram][corpus]

Language trends run in mysterious 14-year cycles と題する記事をみつけた.非常におもしろい. *

Marcelo Montemurro と Damián Zanette による調査結果である.2人は「#607. Google Books Ngram Viewer」 ([2010-12-25-1]) とコンピュータ・プログラムを用いて,1700年から2008年の間の常用される名詞の "popularity" の推移を探った.すると,14年周期で英単語の "popularity" が上がっては下がるということが繰り返されていることが分かったという.意味的に関連する語群は盛衰をともにするというパターンも見つかっているし,英語に限らずフランス語,ドイツ語,イタリア語,ロシア語,スペイン語などの言語でも似たような周期が確認されるというから驚きだ.

では,なぜこのような周期があり,そしてなぜ14年前後という間隔なのか.いくつかの語については,政治を含めた社会的な変化との連動の可能性が指摘されうるが,一般論として,なぜこのような周期があるのかは不明である.もちろん,この周期が無作為変動の誤差の範囲にとどまっているのではないかという疑念は残っており,さらなる調査が必要ではあろう.しかし,もし何らかの要因があるとすれば,それはいったい何なのか.研究者の1人は "an obvious cultural connection" は見られないとしている.

人間行動の反復性,流行の周期,言語行動の慣れや飽き,などの問題と関わるのだろうか.いずれにせよ,非常に不思議で,興味をそそる現象である.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow