2014-12-02 Tue

■ #2045. なぜ mayn't が使われないのか? (2) [auxiliary_verb][negative][clitic][corpus][emode][lmode][eebo][clmet][sobokunagimon]

昨日の記事「#2044. なぜ mayn't が使われないのか? (1)」 ([2014-12-01-1]) に引き続き,標記の問題.今回は歴史的な事実を提示する.OED によると,短縮形 mayn't は16世紀から例がみられるというが,引用例として最も早いものは17世紀の Milton からのものだ.

1631 Milton On Univ. Carrier ii. 18 If I mayn't carry, sure I'll ne'er be fetched.

OED に基づくと,注目すべき時代は初期近代英語以後ということになる.そこで EEBO (Early English Books Online) ベースで個人的に作っている巨大テキスト・データベースにて然るべき検索を行ったところ,次のような結果が出た(mai や nat などの異形も含めて検索した).各時期のサブコーパスの規模が異なるので,100万語当たりの頻度 (wpm) で比較されたい.

| Period (subcorpus size) | mayn't | may not |

|---|---|---|

| 1451--1500 (244,602 words) | 0 wpm (0 times) | 474.24 wpm (116 times) |

| 1501--1550 (328,7691 words) | 0 (0) | 133.22 (438) |

| 1551--1600 (13,166,673 words) | 0 (0) | 107.01 (1,409) |

| 1601--1650 (48,784,537 words) | 0.020 (1) | 131.85 (6,432) |

| 1651--1700 (83,777,910 words) | 1.03 (86) | 131.54 (11,020) |

| 1701--1750 (90,945 words) | 0 (0) | 109.96 (10) |

短縮形 mayn't は非短縮形 may not に比べて,常に圧倒的少数派であったことは疑うべくもない.短縮形の16世紀からの例は見つからなかったが,17世紀に少しずつ現われ出す様子はつかむことができた.18世紀からの例がないのは,サブコーパスの規模が小さいからかもしれない.「#1948. Addison の clipping 批判」 ([2014-08-27-1]) で見たように,Addison が18世紀初頭に mayn't を含む短縮形を非難していたほどだから,口語ではよく行われていたのだろう.

続いて後期近代英語のコーパス CLMET3.0 で同様に調べてみた.18--19世紀中にも,mayn't は相対的に少ないながらも確かに使用されており,19世紀後半には頻度もやや高まっているようだ.mayn't と may not の間で揺れを示すテキストも少なくない.

| Period (subcorpus size) | mayn't | may not |

|---|---|---|

| 1710--1780 (10,480,431 words) | 33 | 859 |

| 1780--1850 (11,285,587) | 21 | 703 |

| 1850--1920 (12,620,207) | 68 | 601 |

19世紀後半に mayn't の使用が増えている様子は,近現代アメリカ英語コーパス COHA でも確認できる.

20世紀に入ってからの状況は未調査だが,「#677. 現代英語における法助動詞の衰退」 ([2011-03-05-1]) から示唆されるように,may 自体が徐々に衰退の運命をたどることになったわけだから,mayn't の運命も推して知るべしだろう.昨日の記事で触れたように特に現代アメリカ英語では shan't も shall とともに衰退したてきたことと考え合わせると,否定短縮形の衰退は助動詞本体(肯定形)の衰退と関連づけて理解する必要があるように思われる.may 自体が古く堅苦しい助動詞となれば,インフォーマルな響きをもつ否定接辞を付加した mayn't のぎこちなさは,それだけ著しく感じられるだろう.この辺りに,mayn't の不使用の1つの理由があるのではないか.もう1つ思いつきだが,mayn't の不使用は,非標準的で社会的に低い価値を与えられている ain't と押韻することと関連するかもしれない.いずれも仮説段階の提案にすぎないが,参考までに.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2014-10-20 Mon

■ #2002. Richard Hodges の綴字改革ならぬ綴字教育 [spelling_reform][spelling][orthography][alphabet][emode][final_e][silent_letter][mulcaster][diacritical_mark]

「#1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論」 ([2014-08-18-1]) や「#1940. 16世紀の綴字論者の系譜」 ([2014-08-19-1]) でみたように,16世紀には様々な綴字改革案が出て,綴字の固定化を巡る議論は活況を呈した.しかし,Mulcaster を代表とする伝統主義路線が最終的に受け入れられるようになると,16世紀末から17世紀にかけて,綴字改革の熱気は冷めていった.人々は,決してほころびの少なくない伝統的な綴字体系を半ば諦めの境地で受け入れることを選び,むしろそれをいかに効率よく教育していくかという実際的な問題へと関心を移していったのである.そのような教育者のなかに,Edmund Coote (fl. 1597; see Edmund Coote's English School-maister (1596)) や Richard Hodges (fl. 1643--49) という顔ぶれがあった.

Hodges については「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]) でも触れたように,綴字史への関与のほかにも,当時の発音に関する貴重な資料を提供してくれているという功績がある.例えば Hodges のリストには,cox, cocks, cocketh; clause, claweth, claws; Mr Knox, he knocketh, many knocks などとあり,-eth が -s と同様に発音されていたことが示唆される (Horobin 129) .また,様々な発音区別符(号) (diacritical mark) を綴字に付加したことにより,Hodges は事実上の発音表記を示してくれたのである.例えば,gäte, grëat のように母音にウムラウト記号を付すことにより長母音を表わす方式や,garde, knôwn のように黙字であることを示す下線を導入した (The English Primrose (1644)) .このように,Hodges は当時のすぐれた音声学者といってもよく,Shakespeare 死語の時代の発音を伝える第1級の資料を提供してくれた.

しかし,Hodges の狙いは,当然ながら後世に当時の発音を知らしめることではなかった.それは,あくまで綴字教育にあった.体系としては必ずしも合理的とはいえない伝統的な綴字を子供たちに効果的に教育するために,その橋渡しとして,上述のような発音区別符の付加を提案したのである.興味深いのは,その提案の中身は,1世代前の表音主義の綴字改革者 William Bullokar (fl. 1586) の提案したものとほぼ同じ趣旨だったことである.Bullokar も旧アルファベットに数々の記号を付加することにより,表音を目指したのだった.しかし,Hodges の提案のほうがより簡易で一貫しており,何よりも目的が綴字改革ではなく綴字教育にあった点で,似て非なる試みだった.時代はすでに綴字改革から綴字教育へと移り変わっており,さらに次に来たるべき綴字規則化論者 ("Spelling Regularizers") の出現を予期させる段階へと進んでいたのである.

この時代の移り変わりについて,渡部 (96) は「Bullokar と同じ工夫が,違った目的のためになされているところに,つまり17世紀中葉の綴字問題が一種の「ルビ振り」に似た努力になっている所に,時代思潮の変化を認めざるをえない」と述べている.Hodges の発音区別符をルビ振りになぞらえたのは卓見である.ルビは文字の一部ではなく,教育的配慮を含む補助記号である.したがって,形としてはほぼ同じものであったとしても,文字の一部を構成する不可欠の要素として Bullokar が提案した記号は,決してルビとは呼べない.ルビ振りの比喩により,Bullokar の堅さと Hodges の柔らかさが感覚的に理解できるような気がしてくる.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ 渡部 昇一 『英語学史』 英語学大系第13巻,大修館書店,1975年.

2014-10-13 Mon

■ #1995. Mulcaster の語彙リスト "generall table" における語源的綴字 [mulcaster][lexicography][lexicology][cawdrey][emode][dictionary][spelling_reform][etymological_respelling][final_e]

昨日の記事「#1994. John Hart による語源的綴字への批判」 ([2014-10-12-1]) や「#1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論」 ([2014-08-18-1]),「#1940. 16世紀の綴字論者の系譜」 ([2014-08-19-1]),「#1943. Holofernes --- 語源的綴字の礼賛者」 ([2014-08-22-1]) で Richard Mulcaster の名前を挙げた.「#441. Richard Mulcaster」 ([2010-07-12-1]) ほか mulcaster の各記事でも話題にしてきたこの初期近代英語期の重要人物は,辞書編纂史の観点からも,特筆に値する.

英語史上最初の英英辞書は,「#603. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (1)」 ([2010-12-21-1]),「#604. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (2)」 ([2010-12-22-1]),「#726. 現代でも使えるかもしれない教育的な Cawdrey の辞書」 ([2011-04-23-1]),「#1609. Cawdrey の辞書をデータベース化」 ([2013-09-22-1]) で取り上げたように,Robert Cawdrey (1537/38--1604) の A Table Alphabeticall (1604) と言われている.しかし,それに先だって Mulcaster が The First Part of the Elementarie (1582) において約8000語の語彙リスト "generall table" を掲げていたことは銘記しておく必要がある.Mulcaster は,教育的な見地から英語辞書の編纂の必要性を訴え,いわば試作としてとしてこの "generall table" を世に出した.Cawdrey は Mulcaster に刺激を受けたものと思われ,その多くの語彙を自らの辞書に採録している.Mulcaster の英英辞書の出版を希求する切実な思いは,次の一節に示されている.

It were a thing verie praiseworthie in my opinion, and no lesse profitable then praise worthie, if som one well learned and as laborious a man, wold gather all the words which we vse in our English tung, whether naturall or incorporate, out of all professions, as well learned as not, into one dictionarie, and besides the right writing, which is incident to the Alphabete, wold open vnto vs therein, both their naturall force, and their proper vse . . . .

上の引用の最後の方にあるように,辞書編纂史上重要なこの "generall table" は,語彙リストである以上に,「正しい」綴字の指南書となることも目指していた.当時の綴字改革ブームのなかにあって Mulcaster は伝統主義の穏健派を代表していたが,穏健派ながらも final e 等のいくつかの規則は提示しており,その効果を具体的な単語の綴字の列挙によって示そうとしたのである.

For the words, which concern the substance thereof: I haue gathered togither so manie of them both enfranchised and naturall, as maie easilie direct our generall writing, either bycause theie be the verie most of those words which we commonlie vse, or bycause all other, whether not here expressed or not yet inuented, will conform themselues, to the presidencie of these.

「#1387. 語源的綴字の採用は17世紀」 ([2013-02-12-1]) で,Mulcaster は <doubt> のような語源的綴字には否定的だったと述べたが,それを "generall table" を参照して確認してみよう.EEBO (Early English Books Online) のデジタル版 The first part of the elementarie により,いくつかの典型的な語源的綴字を表わす語を参照したところ,auance., auantage., auentur., autentik., autor., autoritie., colerak., delite, det, dout, imprenable, indite, perfit, receit, rime, soueranitie, verdit, vitail など多数の語において,「余分な」文字は挿入されていない.確かに Mulcaster は語源的綴字を受け入れていないように見える.しかし,他の語例を参照すると,「余分な」文字の挿入されている aduise., language, psalm, realm, salmon, saluation, scholer, school, soldyer, throne なども確認される.

語によって扱いが異なるというのはある意味で折衷派の Mulcaster らしい振る舞いともいえるが,Mulcaster の扱い方の問題というよりも,当時の各語各綴字の定着度に依存する問題である可能性がある.つまり,すでに語源的綴字がある程度定着していればそれがそのまま採用となったということかもしれないし,まだ定着していなければ採用されなかったということかもしれない.Mulcaster の選択を正確に評価するためには,各語における語源的綴字の挿入の時期や,その拡散と定着の時期を調査する必要があるだろう.

"generall table" のサンプル画像が British Library の Mulcaster's Elementarie より閲覧できるので,要参照. *

2014-10-12 Sun

■ #1994. John Hart による語源的綴字への批判 [etymological_respelling][spelling][emode][hart][spelling_reform]

初期近代英語期の語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) について,本ブログでいろいろと議論してきた.そのなかの1つ「#1942. 語源的綴字の初例をめぐって」 ([2014-08-21-1]) で,語源的綴字に批判的だった論客の1人として John Hart (c. 1501--74) の名前を挙げた.Hart は表音主義の綴字改革者の1人で An Orthographie (1569) を出版したことで知られるが,あまりに急進的な改革案のために受け入れられず,後世の綴字に影響を及ぼすことはほとんどなかった.実際,Hart は語源的綴字の問題に関しても批判を加えたものの,最終的にはその批判は響かず,Mulcaster など伝統主義の穏健派に主導権を明け渡すことになった.

Hart の語源的綴字に対する批判は,当時の英語の綴字が全般的に抱える諸問題の指摘のなかに見いだされる.Hart は,英語の綴字は "the divers vices and corruptions which use (or better abuse) mainteneth in our writing" に犯されているとし,問題点として diminution, superfluite, usurpation of power, misplacing の4種を挙げている.diminution はあるべきところに文字が欠けていることを指すが,実例はないと述べており,あくまで理論上の欠陥という扱いである.残りの3つは実際的なもので,まず superfluite はあるべきではないところに文字があるという例である.<doubt> の <b> がその典型例であり,いわゆる語源的綴字の問題は,Hart に言わせれば superfluite の問題の1種ということになる.usurpation は,<g> が /g/ にも /ʤ/ にも対応するように,1つの文字に複数の音価が割り当てられている問題.最後に misplacing は,例えば /feɪbəl/ に対応する綴字としては *<fabel> となるべきところが <fable> であるという文字の配列の問題を指す.

上記のように,語源的綴字が関わってくるのは,あるべきでないところに文字が挿入されている superfluite においてである.Hart (121--22) の原文より,関連箇所を引用しよう.

Then secondli a writing is corrupted, when yt hath more letters than the pronunciation neadeth of voices: for by souch a disordre a writing can not be but fals: and cause that voice to be pronunced in reading therof, which is not in the word in commune speaking. This abuse is great, partly without profit or necessite, and but oneli to fill up the paper, or make the word thorow furnysshed with letters, to satisfie our fantasies . . . . As breifli for example of our superfluite, first for derivations, as the b in doubt, the g in eight, h in authorite, l in souldiours, o in people, p in condempned, s in baptisme, and divers lyke.

Hart は superfluite の例として eight や people なども挙げているが,通常これらは英語史において初期近代英語期に典型的ないわゆる語源的綴字の例として言及されるものではない.したがって,「語源的綴字 < superfluite 」という関係と理解しておくのが適切だろう.

・Hart, John. MS British Museum Royal 17. C. VII. The Opening of the Unreasonable Writing of Our Inglish Toung. 1551. In John Hart's Works on English Orthography and Pronunciation [1551, 1569, 1570]: Part I. Ed. Bror Danielsson. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1955. 109--64.

2014-10-01 Wed

■ #1983. -ick or -ic (3) [suffix][corpus][spelling][emode][eebo][johnson]

昨日の記事「#1982. -ick or -ic (2)」 ([2014-09-30-1]) に引き続き,初期近代英語での -ic(k) 語の異綴りの分布(推移)を調査する.使用するコーパスは市販のものではなく,個人的に EEBO (Early English Books Online) からダウンロードして蓄積した巨大テキスト集である.まだコーパス風に整備しておらず,代表性も均衡も保たれていない単なるテキストの集合という体なので,調査結果は仮のものとして解釈しておきたい.時代区分は16世紀と17世紀に大雑把に分け,それぞれコーパスサイズは923,115語,9,637,954語である(コーパスサイズに10倍以上の開きがある不均衡な実態に注意).以下では,100万語当たりの頻度 (wpm) で示してある.

| Spelling pair | Period 1 (1501--1600) (in wpm) | Period 2 (1601--1700) (in wpm) |

|---|---|---|

| angelick / angelic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.45 / 0.21 |

| antick / antic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 2.49 / 0.10 |

| apoplectick / apoplectic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| aquatick / aquatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.00 |

| arabick / arabic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.52 / 0.10 |

| archbishoprick / archbishopric | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.00 |

| arctick / arctic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.42 / 0.00 |

| arithmetick / arithmetic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 3.22 / 0.31 |

| aromatick / aromatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.83 / 0.10 |

| asiatick / asiatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.31 / 0.00 |

| attick / attic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.31 / 0.21 |

| authentick / authentic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 3.94 / 0.42 |

| balsamick / balsamic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.73 / 0.10 |

| baltick / baltic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.93 / 0.00 |

| bishoprick / bishopric | 1.08 / 0.00 | 4.25 / 0.00 |

| bombastick / bombastic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.00 |

| catholick / catholic | 5.42 / 0.00 | 38.39 / 1.97 |

| caustick / caustic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| characteristick / characteristic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.10 |

| cholick / cholic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.93 / 0.00 |

| comick / comic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 1.45 / 0.10 |

| critick / critic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.76 / 1.87 |

| despotick / despotic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.62 / 0.21 |

| domestick / domestic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 8.09 / 0.21 |

| dominick / dominic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 0.62 / 0.42 |

| dramatick / dramatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.83 / 0.10 |

| emetick / emetic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.31 / 0.00 |

| epick / epic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.10 |

| ethick / ethic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.00 / 0.10 |

| exotick / exotic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.73 / 0.10 |

| fabrick / fabric | 0.00 / 0.00 | 8.72 / 0.31 |

| fantastick / fantastic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 3.42 / 0.10 |

| frantick / frantic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 3.94 / 0.00 |

| frolick / frolic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 3.32 / 0.00 |

| gallick / gallic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 3.32 / 0.52 |

| garlick / garlic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 2.28 / 0.00 |

| heretick / heretic | 2.17 / 0.00 | 6.02 / 0.00 |

| heroick / heroic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 16.91 / 1.35 |

| hieroglyphick / hieroglyphic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.31 / 0.00 |

| lethargick / lethargic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.52 / 0.10 |

| logick / logic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 7.06 / 1.04 |

| lunatick / lunatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.66 / 0.00 |

| lyrick / lyric | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.42 / 0.10 |

| magick / magic | 2.17 / 0.00 | 3.32 / 0.10 |

| majestick / majestic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 4.88 / 0.42 |

| mechanick / mechanic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 4.15 / 0.00 |

| metallick / metallic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| metaphysick / metaphysic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.21 |

| mimick / mimic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.42 / 0.00 |

| musick / music | 7.58 / 627.22 | 40.98 / 251.40 |

| mystick / mystic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.45 / 0.10 |

| panegyrick / panegyric | 0.00 / 0.00 | 4.46 / 0.10 |

| panick / panic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.35 / 0.10 |

| paralytick / paralytic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.00 |

| pedantick / pedantic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.93 / 0.00 |

| philosophick / philosophic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.00 / 0.21 |

| physick / physic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 27.39 / 1.56 |

| plastick / plastic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| platonick / platonic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.93 / 0.00 |

| politick / politic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 15.98 / 1.14 |

| prognostick / prognostic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.52 / 0.00 |

| publick / public | 5.42 / 3.25 | 237.39 / 5.71 |

| relick / relic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.52 / 0.00 |

| republick / republic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 3.01 / 0.31 |

| rhetorick / rhetoric | 0.00 / 0.00 | 5.71 / 0.21 |

| rheumatick / rheumatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| romantick / romantic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.83 / 0.00 |

| rustick / rustic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.66 / 0.00 |

| sceptick / sceptic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.10 |

| scholastick / scholastic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.31 / 0.42 |

| stoick / stoic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.93 / 0.00 |

| sympathetick / sympathetic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| topick / topic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.45 / 0.00 |

| traffick / traffic | 3.25 / 0.00 | 8.61 / 0.42 |

| tragick / tragic | 3.25 / 0.00 | 2.91 / 0.00 |

| tropick / tropic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.04 / 0.00 |

全体として眺めると,初期近代英語では -ick のほうが -ic よりも優勢である.-ic が例外的に優勢なのは,16世紀からの music と,17世紀の critic, scholastic くらいである.昨日の結果と合わせて推測すると,1700年以降,おそらく18世紀前半の間に,-ick から -ic への形勢の逆転が比較的急速に進行していたのではないか.個々の語において逆転のスピードは多少異なるようだが,一般的な傾向はつかむことができた.18世紀半ばに -ick を選んだ Johnson は,やはり保守的だったようだ.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2014-08-19 Tue

■ #1940. 16世紀の綴字論者の系譜 [spelling][orthography][emode][spelling_reform][mulcaster][alphabet][grammatology][hart]

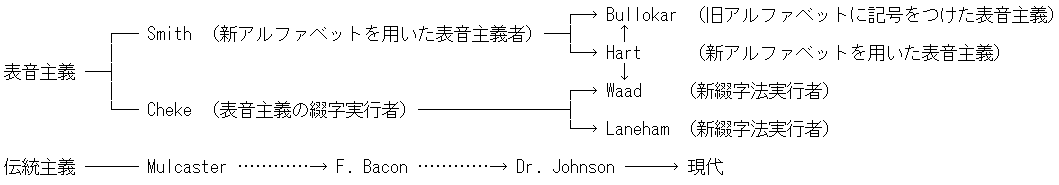

昨日の記事「#1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論」 ([2014-08-18-1]) で,数名の綴字論者の名前を挙げた.彼らは大きく表音主義の急進派と伝統主義の穏健派に分けられる.16世紀半ばから次世紀へと連なるその系譜を,渡部 (64) にしたがって示そう.

昨日の記事で出てきていない名前もある.Cheke と Smith は宮廷と関係が深かったことから,宮廷関係者である Waad と Laneham にも表音主義への関心が移ったようで,彼らは Cheke の新綴字法を実行した.Hart は Bullokar や Waad に影響を与えた.伝統主義路線としては,Mulcaster と Edmund Coote (fl. 1597; see Edmund Coote's English School-maister (1596)) が16世紀末に影響力をもち,17世紀には Francis Bacon (1561--1626) や Ben Jonson (c. 1573--1637) を経て,18世紀の Dr. Johnson (1709--84) まで連なった.そして,この路線は,結局のところ現代にまで至る正統派を形成してきたのである.

結果としてみれば,厳格な表音主義は敗北した.表音文字を標榜する ローマン・アルファベット (Roman alphabet) を用いる英語の歴史において,厳格な表音主義が敗退したということは,文字論の観点からは重要な意味をもつように思われる.文字にとって最も重要な目的とは,表語,あるいは語といわずとも何らかの言語単位を表わすことであり,アルファベットに典型的に備わっている表音機能はその目的を達成するための手段にすぎないのではないか.もちろん表音機能それ自体は有用であり,捨て去る必要はないが,表語という最終目的のために必要とあらば多少は犠牲にできるほどの機能なのではないか.

このように考察した上で,「#1332. 中英語と近代英語の綴字体系の本質的な差」 ([2012-12-19-1]),「#1386. 近代英語以降に確立してきた標準綴字体系の特徴」 ([2013-02-11-1]),「#1829. 書き言葉テクストの3つの機能」 ([2014-04-30-1]) の議論を改めて吟味したい.

・ 渡部 昇一 『英語学史』 英語学大系第13巻,大修館書店,1975年.

2014-08-18 Mon

■ #1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論 [punctuation][alphabet][standardisation][spelling][orthography][emode][spelling_reform][mulcaster][spelling_pronunciation_gap][final_e][hart]

16世紀には正書法 (orthography) の問題,Mulcaster がいうところの "right writing" の問題が盛んに論じられた(cf. 「#1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題」 ([2013-03-04-1])).英語の綴字は,現代におけると同様にすでに混乱していた.折しも生じていた数々の音韻変化により発音と綴字の乖離が広がり,ますます表音的でなくなった.個人レベルではある種の綴字体系が意識されていたが,個人を超えたレベルではいまだ固定化されていなかった.仰ぎ見るはラテン語の正書法だったが,その完成された域に達するには,もう1世紀ほどの時間をみる必要があった.以下,主として Baugh and Cable (208--14) の記述に依拠し,16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論を概説する.

個人レベルでは一貫した綴字体系が目指されたと述べたが,そのなかには私的にとどまるものもあれば,出版されて公にされるものもあった.私的な例としては,古典語学者であった John Cheke (1514--57) は,長母音を母音字2つで綴る習慣 (ex. taak, haat, maad, mijn, thijn) ,語末の <e> を削除する習慣 (ex. giv, belev) ,<y> の代わりに <i> を用いる習慣 (ex. mighti, dai) を実践した.また,Richard Stanyhurst は Virgil (1582) の翻訳に際して,音節の長さを正確に表わすための綴字体系を作り出し,例えば thee, too, mee, neere, coonning, woorde, yeet などと綴った.

公的にされたものの嚆矢は,1558年以前に出版された匿名の An A. B. C. for Children である.そこでは母音の長さを示す <e> の役割 (ex. made, ride, hope) などが触れられているが,ほんの数頁のみの不十分な扱いだった.より野心的な試みとして最初に挙げられるのは,古典語学者 Thomas Smith (1513--77) による1568年の Dialogue concerning the Correct and Emended Writing of the English Language だろう.Smith はアルファベットを34文字に増やし,長母音に符号を付けるなどした.しかし,この著作はラテン語で書かれたため,普及することはなかった.

翌年1569年,そして続く1570年,John Hart (c. 1501--74) が An Orthographie と A Method or Comfortable Beginning for All Unlearned, Whereby They May Bee Taught to Read English を出版した.Hart は,<ch>, <sh>, <th> などの二重字 ((digraph)) に対して特殊文字をあてがうなどしたが,Smith の試みと同様,急進的にすぎたために,まともに受け入れられることはなかった.

1580年,William Bullokar (fl. 1586) が Booke at large, for the Amendment of Orthographie for English Speech を世に出す.Smith と Hart の新文字導入が失敗に終わったことを反面教師とし,従来のアルファベットのみで綴字改革を目指したが,代わりにアクセント記号,アポストロフィ,鉤などを惜しみなく文字に付加したため,結果として Smith や Hart と同じかそれ以上に読みにくい恐るべき正書法ができあがってしまった.

Smith, Hart, Bullokar の路線は,17世紀にも続いた.1634年,Charles Butler (c. 1560--1647) は The English Grammar, or The Institution of Letters, Syllables, and Woords in the English Tung を出版し,語末の <e> の代わりに逆さのアポストロフィを採用したり,<th> の代わりに <t> を逆さにした文字を使ったりした.以上,Smith から Butler までの急進的な表音主義の綴字改革はいずれも失敗に終わった.

上記の急進派に対して,保守派,穏健派,あるいは伝統・慣習を重んじ,綴字固定化の基準を見つけ出そうとする現実即応派とでも呼ぶべき路線の第一人者は,Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) である(この英語史上の重要人物については「#441. Richard Mulcaster」 ([2010-07-12-1]) や mulcaster の各記事で扱ってきた).彼の綴字に対する姿勢は「綴字は発音を正確には表わし得ない」だった.本質的な解決法はないのだから,従来の慣習的な綴字を基にしてもう少しよいものを作りだそう,いずれにせよ最終的な規範は人々が決めることだ,という穏健な態度である.彼は The First Part of the Elementarie (1582) において,いくつかの提案を出している.<fetch> や <scratch> の <t> の保存を支持し,<glasse> や <confesse> の語末の <e> の保存を支持した.語末の <e> については,「#1344. final -e の歴史」 ([2012-12-31-1]) でみたような規則を提案した.

「#1387. 語源的綴字の採用は17世紀」 ([2013-02-12-1]) でみたように,Mulcaster の提案は必ずしも後世の標準化された綴字に反映されておらず(半数以上は反映されている),その分だけ彼の歴史的評価は目減りするかもしれないが,それでも綴字改革の路線を急進派から穏健派へシフトさせた功績は認めてよいだろう.この穏健派路線は English Schoole-Master (1596) を著した Edmund Coote (fl. 1597) や The English Grammar (1640) を著した Ben Jonson (c. 1573--1637) に引き継がれ,Edward Phillips による The New World of English Words (1658) が世に出た17世紀半ばまでには,綴字の固定化がほぼ完了することになる.

この問題に関しては渡部 (40--64) が詳しく,たいへん有用である.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

・ 渡部 昇一 『英語学史』 英語学大系第13巻,大修館書店,1975年.

2014-06-28 Sat

■ #1888. 英語の性を自然性と呼ぶことについて [gender][sociolinguistics][emode][personification][terminology]

昨日の記事「#1887. 言語における性を考える際の4つの視点」 ([2014-06-27-1]) で,英語史における「文法性から自然性への変化」を考える際に関与するのは,grammatical gender, lexical gender, referential gender の3種であると述べた.しかし,これは正確な言い方ではないかもしれない.そこには social gender もしっかりと関与している,という批判を受けるかもしれない.Curzan は,英語史で前提とされている「文法性から自然性への変化」という謂いの不正確さを指摘している.

自然性 (natural gender) という用語が通常意味しているのは,語の性は,それが指示している対象の生物学的な性 (biological sex) と一致するということである.例えば,girl という語は人の女性を指示対象とするので,語としての性も feminine であり,father という語は人の男性を指示対象とするので,語としての性も masculine となる,といった具合である.また,book の指示対象は男性でも女性でもないので,語としての性は neuter であり,person の指示対象は男女いずれを指すかについて中立的なので,語としては common gender といわれる.このように,自然性の考え方は単純であり,一見すると問題はないように思われる.昨日導入した用語を使えば,自然性とは,referential gender がそのまま lexical gender に反映されたものと言い換えることができそうだ.

しかし,Curzan は「自然性」のこのような短絡的なとらえ方に疑問を呈している.Curzan は,Joschua Poole, William Bullokar, Alexander Gil, Ben Jonson など初期近代英語の文法家たちの著作には,擬人性への言及が多いことを指摘している.例えば,Jonson は,1640年の The English Grammar で,Angels, Men, Starres, Moneth's, Winds, Planets は男性とし,I'lands, Countries, Cities, ship は女性とした.また,Horses, Dogges は典型的に男性,Eagles, Hawkess などの Fowles は典型的に女性とした (Curzan 566) .このような擬人性は当然ながら純粋な自然性とは質の異なる性であり,当時社会的に共有されていたある種の世界観,先入観,性差を反映しているように思われる.換言すれば,これらの擬人性の例は,当時の social gender がそのまま lexical gender に反映されたものではないか.

上の議論を踏まえると,近代英語期には確立していたとされるいわゆる「自然性」は,実際には (1) 伝統的な理解通り,referential gender (biological sex) がそのまま lexical gender に反映されたものと,(2) social gender が lexical gender に反映されたもの,の2種類の gender が融合したもの,言うなれば "lexical gender based on referential and social genders" ではないか.この長い言い回しを避けるためのショートカットとして「自然性」あるいは "natural gender" と呼ぶのであれば,それはそれでよいかもしれないが,伝統的に理解されている「自然性」あるいは "natural gender" とは内容が大きく異なっていることには注意したい.

Curzan (570--71) の文章を引用する.

The Early Modern English gender system has traditionally been treated as biologically "natural", which it is in many respects: male human beings are of the masculine gender, females of the feminine, and most inanimates of the neuter. But these early grammarians explicitly describe how the constraints of the natural gender system can be broken by the use of the masculine or feminine for certain inanimate nouns. Their categories construct the masculine as representing the "male sex and that of the male kind" and the feminine as the "female sex and that of the female kind", and clearly various inanimates fall into these gendered "kinds". Personification, residual confusion, and classical allegory are not sufficient explanations, as many scholars now recognize in discussions of similar fluctuation in the Modern English gender system. An alternative explanation is that what the early grammarians label "kind" is synonymous with what today is labeled "gender"; in other words, "kind" refers to the socially constructed attributes assigned to a given sex.

この議論に基づくならば,英語史における性の変化の潮流は,より正確には,「grammatical gender から natural gender へ」ではなく「grammatical gender から lexical gender based on referential and social gender へ」ということになるだろうか.

英語における擬人性については,関連して「#1517. 擬人性」 ([2013-06-22-1]),「#1028. なぜ国名が女性とみなされてきたのか」 ([2012-02-19-1]),「#890. 人工頭脳系 acronym は女性名が多い?」 ([2011-10-04-1]),「#852. 船や国名を受ける代名詞 she (1)」 ([2011-08-27-1]) 及び「#853. 船や国名を受ける代名詞 she (2)」 ([2011-08-28-1]),「#854. 船や国名を受ける代名詞 she (3)」 ([2011-08-29-1]) も参照.

・ Curzan, Anne. "Gender Categories in Early English Grammars: Their Message in the Modern Grammarian." Gender in Grammar and Cognition. Ed. Barbara Unterbeck et al. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2000. 561--76.

2014-05-30 Fri

■ #1859. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (5) [verb][conjugation][emode][paradigm][analogy][3pp][shakespeare][nptr][causation]

今回は,これまでにも 3pp の各記事で何度か扱ってきた話題の続き.すでに論じてきたように,動詞の直説法における3複現の -s の起源については,言語外的な北部方言影響説と,言語内的な3単現の -s からの類推説とが対立している.言語内的な類推説を唱えた初期の論者として,Smith がいる.Smith は Shakespeare の First Folio を対象として,3複現の -s の例を約100個みつけた.Smith は,その分布を示しながら北部からの影響説を強く否定し,内的な要因のみで十分に説明できると論断した.その趣旨は論文の結論部よくまとまっている (375--76) .

I. That, as an historical explanation of the construction discussed, the recourse to the theory of Northumbrian borrowing is both insufficient and unnecessary.

II. That these s-predicates are nothing more than the ordinary third singulars of the present indicative, which, by preponderance of usage, have caused a partial displacement of the distinctively plural forms, the same operation of analogy finding abundant illustrations in the popular speech of to-day.

III. That, in Shakespeare's time, the number and corresponding influence of the third singulars were far greater than now, inasmuch as compound subjects could be followed by singular predicates.

IV. That other apparent anomalies of concord to be found in Shakespeare's syntax,---anomalies that elude the reach of any theory that postulates borrowing,---may also be adequately explained on the principle of the DOMINANT THIRD SINGULAR.

要するに,Smith は,当時にも現在にも見られる3単現の -s の共時的な偏在性・優位性に訴えかけ,それが3複現の領域へ侵入したことは自然であると説いている.

しかし,Smith の議論には問題が多い.第1に,Shakespeare のみをもって初期近代英語を代表させることはできないということ.第2に,北部影響説において NPTR (Northern Present Tense Rule; 「#1852. 中英語の方言における直説法現在形動詞の語尾と NPTR」 ([2014-05-23-1]) を参照) がもっている重要性に十分な注意を払わずに,同説を排除していること(ただし,NPTR に関連する言及自体は p. 366 の脚注にあり).第3に,Smith に限らないが,北部影響説と類推説とを完全に対立させており,両者をともに有効とする見解の可能性を排除していること.

第1と第2の問題点については,Smith が100年以上前の古い研究であることも関係している.このような問題点を指摘できるのは,その後研究が進んできた証拠ともいえる.しかし,第3の点については,今なお顧慮されていない.北部影響説と類推説にはそれぞれの強みと弱みがあるが,両者が融和できないという理由はないように思われる.

「#1852. 中英語の方言における直説法現在形動詞の語尾と NPTR」 ([2014-05-23-1]) の記事でみたように McIntosh の研究は NPTR の地理的波及を示唆するし,一方で Smith の指摘する共時的で言語内的な要因もそれとして説得力がある.いずれの要因がより強く作用しているかという効き目の強さの問題はあるだろうが,いずれかの説明のみが正しいと前提することはできないのではないか.私の立場としては,「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1]) で論じたように,3複現の -s の問題についても言語変化の "multiple causation" を前提としたい.

・ Smith, C. Alphonso. "Shakespeare's Present Indicative S-Endings with Plural Subjects: A Study in the Grammar of the First Folio." Publications of the Modern Language Association 11 (1896): 363--76.

・ McIntosh, Angus. "Present Indicative Plural Forms in the Later Middle English of the North Midlands." Middle English Studies Presented to Norman Davis. Ed. Douglas Gray and E. G. Stanley. Oxford: OUP, 1983. 235--44.

2014-05-28 Wed

■ #1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力 [verb][conjugation][emode][language_change][causation][suffix][inflection][phonotactics][3sp]

「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]),「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]) と続けて3単現の -th → -s の変化について取り上げてきた.この変化をもたらした要因については諸説が唱えられている.また,「#1413. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s」 ([2013-03-10-1]) で触れた通り,3複現においても平行的に -th → -s の変化が起こっていたらしい証拠があり,2つの問題は絡み合っているといえる.

北部方言では,古英語より直説法現在の人称語尾として -es が用いられており,中部・南部の -eþ とは一線を画していた.したがって,中英語以降,とりわけ初期近代英語での -th → -s の変化は北部方言からの影響だとする説が古くからある.一方で,いずれに方言においても確認された2単現の -es(t) の /s/ が3単現の語尾にも及んだのではないかとする,パラダイム内での類推説もある.その他,be 動詞の is の影響とする説,音韻変化説などもあるが,いずれも決定力を欠く.

諸説紛々とするなかで,Jespersen (17--18) は音韻論の観点から「効率」説を展開する.音素配列における「最小努力の法則」 ('law of least effort') の説と言い換えてもよいだろう.

In my view we have here an instance of 'Efficiency': s was in these frequent forms substituted for þ because it was more easily articulated in all kinds of combinations. If we look through the consonants found as the most important elements of flexions in a great many languages we shall see that t, d, n, s, r occur much more frequently than any other consonant: they have been instinctively preferred for that use on account of the ease with which they are joined to other sounds; now, as a matter of fact, þ represents, even to those familiar with the sound from their childhood, greater difficulty in immediate close connexion with other consonants than s. In ON, too, þ was discarded in the personal endings of the verb. If this is the reason we understand how s came to be in these forms substituted for th more or less sporadically and spontaneously in various parts of England in the ME period; it must have originated in colloquial speech, whence it was used here and there by some poets, while other writers in their style stuck to the traditional th (-eth, -ith, -yth), thus Caxton and prose writers until the 16th century.

言語の "Efficiency" とは言語の進歩 (progress) にも通じる.(妙な言い方だが)Jespersen だけに,実に Jespersen 的な説と言えるだろう.Jespersen 的とは何かについては,「#1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観」 ([2014-01-19-1]) を参照されたい.[s] と [θ] については,「#842. th-sound はまれな発音か」 ([2011-08-17-1]) と「#1248. s と th の調音・音響の差」 ([2012-09-26-1]) もどうぞ.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

2014-05-27 Tue

■ #1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた [pronunciation][verb][conjugation][emode][spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][suffix][inflection][3sp]

昨日の記事「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]) で参照した Kytö (115) は,17世紀当時の評者を直接引用しながら,17世紀前半には -eth と綴られた屈折語尾がすでに -s として発音されていたと述べている.

Contemporary commentators' statements, and verse rhymes, indicate that the -S and -TH endings were pronounced identically from the early 17th century on. Richard Hodges (1643) listed different spellings given for the same pronunciation: for example, clause, claweth, claws; Hodges also pointed out in 1649 that "howesoever wee write them thus, leadeth it, maketh it, noteth it, we say lead's it, make's it, note's it" (cited in Jespersen, 1942: 19--20).

Kytö (132 fn. 10) では,Hodges の後の版での発言も紹介されている.

In the third (and final) edition of his guide (1653: 63--64), Hodges elaborated on his statement: "howsoever wee write many words as if they were two syllables, yet wee doo commonly pronounce them as if they were but one, as for example, these three words, leadeth, noteth, taketh, we doo commonly pronounce them thus, leads, notes, takes, and so all other words of this kind."

17世紀には一般的に <-eth> が /-s/ として発音されていたという状況は,/θ/ と /s/ とは異なる音素であるとしつこく教え込まれている私たちにとっては,一見奇異に思われるかもしれない.しかし,これは,話し言葉での変化が先行し,書き言葉での変化がそれに追いついていかないという,言語変化のありふれた例の1つにすぎない.後に書き言葉も話し言葉に合わせて <-s> と綴られるようになったが,綴字が発音に追いつくには多少なりとも時間差があったということである.日本語表記が旧かなづかいから現代かなづかいへと改訂されるまでの道のりに比べれば,<-eth> から <-s> への綴字の変化はむしろ迅速だったと言えるほどである.

なお,Jespersen (20) によると,超高頻度の動詞 hath, doth, saith については,<-th> 形が18世紀半ばまで普通に見られたという.

表音文字と発音との乖離については spelling_pronunciation_gap の多くの記事で取り上げてきたが,とりわけ「#15. Bernard Shaw が言ったかどうかは "ghotiy" ?」 ([2009-05-13-1]) と「#62. なぜ綴りと発音は乖離してゆくのか」 ([2009-06-28-2]) の記事を参照されたい.

・ Kytö, Merja. "Third-Person Present Singular Verb Inflection in Early British and American English." Language Variation and Change 5 (1993): 113--39.

・ Hodges, Richard. A Special Help to Orthographie; Or, the True Writing of English. London: Printed for Richard Cotes, 1643.

・ Hodges, Richard. The Plainest Directions for the True-Writing of English, That Ever was Hitherto Publisht. London: Printed by Wm. Du-gard, 1649.

・ Hodges, Richard. Most Plain Directions for True-Writing: In Particular for Such English Words as are Alike in Sound, and Unlike Both in Their Signification and Writing. London: Printed by W. D. for Rich. Hodges., 1653. (Reprinted in R. C. Alston, ed. English Linguistics 1500--1800. nr 118. Menston: Scholar Press, 1968; Microfiche ed. 1991)

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

2014-03-15 Sat

■ #1783. whole の <w> [spelling][phonetics][etymology][emode][h][hc][hypercorrection][etymological_respelling][ormulum][w]

whole は,古英語 (ġe)hāl (healthy, sound. hale) に遡り,これ自身はゲルマン祖語 *(ȝa)xailaz,さらに印欧祖語 * kailo- (whole, uninjured, of good omen) に遡る.heal, holy とも同根であり,hale, hail とは3重語をなす.したがって,<whole> の <w> は非語源的だが,中英語末期にこの文字が頭に挿入された.

MED hōl(e (adj.(2)) では,異綴字として wholle が挙げられており,以下の用例で15世紀中に <wh>- 形がすでに見られたことがわかる.

a1450 St.Editha (Fst B.3) 3368: When he was take vp of þe vrthe, he was as wholle And as freysshe as he was ony tyme þat day byfore.

15世紀の主として南部のテキストに現れる最初期の <wh>- 形は,whole 語頭子音 /h/ の脱落した発音 (h-dropping) を示唆する diacritical な役割を果たしていたようだ.しかし,これとは別の原理で,16世紀には /h/ の脱落を示すのではない,単に綴字の見栄えのみに関わる <w> の挿入が行われるようになった.この非表音的,非語源的な <w> の挿入は,現代英語の whore (< OE hōre) にも確認される過程である(whore における <w> 挿入は16世紀からで,MED hōr(e (n.(2)) では <wh>- 形は確認されない).16世紀には,ほかにも whom (home), wholy (holy), whoord (hoard), whote (hot)) whood (hood) などが現れ,<o> の前位置での非語源的な <wh>- が,当時ささやかな潮流を形成していたことがわかる.whole と whore のみが現代標準英語まで生きながらえた理由については,Horobin (62) は,それぞれ同音異義語 hole と hoar との区別を書記上明確にするすることができるからではないかと述べている.

Helsinki Corpus でざっと whole の異綴字を検索してみたところ(「穴」の hole などは手作業で除去済み),中英語までは <wh>- は1例も検出されなかったが,初期近代英語になると以下のように一気に浸透したことが分かった.

| <whole> | <hole> | |

|---|---|---|

| E1 (1500--1569) | 71 | 32 |

| E2 (1570--1639) | 68 | 2 |

| E3 (1640--1710) | 84 | 0 |

では,whole のように,非語源的な <w> が初期近代英語に語頭挿入されたのはなぜか.ここには語頭の [hw] から [h] が脱落して [w] となった音韻変化が関わっている.古英語において <hw>- の綴字で表わされた発音は [hw] あるいは [ʍ] だったが,この発音は初期中英語から文字の位置の逆転した <wh>- として表記されるようになる(<wh>- の規則的な使用は,1200年頃の Ormulum より).しかし,同時期には,すでに発音として [h] の音声特徴が失われ,[w] へと変化しつつあった徴候が確認される.例えば,<h> の綴字を欠いた疑問詞に wat, wænne, wilc などが文証される.[hw] と [h] のこの不安定さゆえに,対応する綴字 <wh>- と <h>- も不安定だったのだろう,この発音と綴字の不安定さが,初期近代英語期の正書法への関心と,必ずしも根拠のない衒いに後押しされて,<whole> や <whore> のような非語源的な綴字を生み出したものと考えられる.

なお,whole には,語頭に /w/ をもつ /woːl/, /wʊl/ などの綴字発音が各種方言に聞かれる.EDD Online の WHOLE, adj., sb. v. を参照.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2014-02-12 Wed

■ #1752. interpretor → interpreter (2) [spelling][suffix][corpus][emode][hc][ppcme2][ppceme][archer][lc]

標記の件については「#1740. interpretor → interpreter」 ([2014-01-31-1]) と「#1748. -er or -or」 ([2014-02-08-1]) で触れてきたが,問題の出発点である,16世紀に interpretor が interpreter へ置換されたという言及について,事実かどうかを確認しておく必要がある.この言及は『英語語源辞典』でなされており,おそらく OED の "In 16th cent. conformed to agent-nouns in -er, like speak-er" に依拠しているものと思われるが,手近にある16世紀前後の時代のいくつかのコーパスを検索し,詳細を調べてみた.

まずは,MED で中英語の綴字事情をのぞいてみよう.初例の Wycliffite Bible, Early Version (a1382) を含め,33例までが -our あるいは -or を含み,-er を示すものは Reginald Pecock による Book of Faith (c1456) より2例のみである.初出以来,中英語期中の一般的な綴字は,-o(u)r だったといっていいだろう.

同じ中英語の状況を,PPCME2 でみてみると,Period M4 (1420--1500) から Interpretours が1例のみ挙った.

次に,初期近代英語期 (1418--1680) の約45万語からなる書簡コーパスのサンプル CEECS (The Corpus of Early English Correspondence でも検索してみたが,2期に区分されたコーパスの第2期分 (1580--1680) から interpreter と interpretor がそれぞれ1例ずつあがったにすぎない.

続いて,MEMEM (Michigan Early Modern English Materials) を試す.このオンラインコーパスは,こちらのページに説明のあるとおり,初期近代英語辞書の編纂のために集められた,主として法助動詞のための例文データベースだが,簡便なコーパスとして利用できる.いくつかの綴字で検索したところ,interpretour が2例,いずれも1535?の Thomas Elyot による The Education or Bringing up of Children より得られた.一方,現代的な interpreter(s) の綴字は,9の異なるテキスト(3つは16世紀,6つは17世紀)から計16例確認された.確かに,16世紀からじわじわと -er 形が伸びてきているようだ.

LC (The Lampeter Corpus of Early Modern English Tracts) は,1640--1740年の大衆向け出版物から成る約119万語のコーパスだが,得られた7例はいずれも -er の綴字だった.

同様の結果が,約330万語の近現代英語コーパス ARCHER 3.2 (A Representative Corpus of Historical English Registers) (1600--1999) でも認められた.1672年の例を最初として,13例がいずれも -er である.

最後に,中英語から近代英語にかけて通時的にみてみよう.HC (Helsinki Corpus) によると,E1 (1500--70) の Henry Machyn's Diary より,"he becam an interpretour betwen the constable and certein English pioners;" が1例のみ見られた.HC を拡大させた PPCEME によると,上記の例を含む計17例の時代別分布は以下の通り.

| -o(u)r | -er(s) | |

|---|---|---|

| E1 (1500--1569) | 2 | 1 |

| E2 (1570--1639) | 3 | 5 |

| E3 (1640--1710) | 0 | 6 |

以上を総合すると,確かに16世紀に,おそらくは同世紀の後半に,現代的な -er が優勢になってきたものと思われる.なお,OED では,1840年の例を最後に -or は姿を消している.

2013-12-09 Mon

■ #1687. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (4) [verb][conjugation][emode][number][agreement][analogy][3pp]

「#1413. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s」 ([2013-03-10-1]),「#1423. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (2)」 ([2013-03-20-1]),「#1576. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (3)」 ([2013-08-20-1]) に引き続いての話題.Wyld (340) は,初期近代英語期における3複現の -s を北部方言からの影響としてではなく,3単現の -s からの類推と主張している.

Present Plurals in -s.

This form of the Pres. Indic. Pl., which survives to the present time as a vulgarism, is by no means very rare in the second half of the sixteenth century among writers of all classes, and was evidently in good colloquial usage well into the eighteenth century. I do not think that many students of English would be inclined to put down the present-day vulgarism to North country or Scotch influence, since it occurs very commonly among uneducated speakers in London and the South, whose speech, whatever may be its merits or defects, is at least untouched by Northern dialect. The explanation of this peculiarity is surely analogy with the Singular. The tendency is to reduce Sing. and Pl. to a common form, so that certain sections of the people inflect all Persons of both Sing. and Pl. with -s after the pattern of the 3rd Pres. Sing., while others drop the suffix even in the 3rd Sing., after the model of the uninflected 1st Pers. Sing. and the Pl. of all Persons.

But if this simple explanation of the present-day Pl. in -s be accepted, why should we reject it to explain the same form at an earlier date?

It would seem that the present-day vulgarism is the lineal traditional descendant of what was formerly an accepted form. The -s Plurals do not appear until the -s forms of the 3rd Sing. are already in use. They become more frequent in proportion as these become more and more firmly established in colloquial usage, though, in the written records which we possess they are never anything like so widespread as the Singular -s forms. Those who persist in regarding the sixteenth-century Plurals in -s as evidence of Northern influence on the English of the South must explain how and by what means that influence was exerted. The view would have had more to recommend it, had the forms first appeared after James VI of Scotland became King of England. In that case they might have been set down as a fashionable Court trick. But these Plurals are far older than the advent of James to the throne of this country.

類推説を支持する主たる論拠は,(1) 3複現の -s は,3単現の -s が用いられるようになるまでは現れていないこと,(2) 北部方言がどのように南部方言に影響を与え得るのかが説明できないこと,の2点である.消極的な論拠であり,決定的な論拠とはなりえないものの,議論は妥当のように思われる.

ただし,1つ気になることがある.Wyld が見つけた初例は,1515年の文献で,"the noble folk of the land shotes at hym." として文証されるという.このテキストには3単現の -s は現われず,3複現には -ith がよく現れるというというから,Wyld 自身の挙げている (1) の論拠とは符合しないように思われるが,どうなのだろうか.いずれにせよ,先立つ中英語期の3単現と3複現の屈折語尾を比較検討することが必要だろう.

・ Wyld, Henry Cecil. A History of Modern Colloquial English. 2nd ed. London: Fisher Unwin, 1921.

2013-10-13 Sun

■ #1630. インク壺語,カタカナ語,チンプン漢語 [japanese][kanji][katakana][waseieigo][lexicology][emode]

初期近代英語期,主としてラテン語に由来するインク壺語 (inkhorn_term) と呼ばれる学者語が大量に借用されたとき,外来語の氾濫に対する大議論が巻き起こったことは,「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1]) や「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1]) などの記事で触れた.Bragg (116) の評価によれば,"This controversy was the first and probably the greatest formal dispute about the English language." ということだった.

現代日本語において似たような問題が,カタカナ語の氾濫という形で生じている.インク壺語とカタカナ語の問題の類似点については,「#1615. インク壺語を統合する試み,2種」 ([2013-09-28-1]) と「#1616. カタカナ語を統合する試み,2種」 ([2013-09-29-1]) で取り上げたが,借用語彙の受容を巡る議論は,およそ似たような性質を帯びるものらしい.そこへもう1つ新語彙の受容を巡る問題を加えるとすれば,近代期の日本の新漢語問題が思い浮かぶ.昨日の記事「#1629. 和製漢語」 ([2013-10-12-1]) でも話題にした,和製漢語を種とする新漢語の大量生産である.

幕末以降,特に明治初期以来,英語をはじめとする大量の西洋語を受け入れるのに,それを漢訳して受容した.当時の知識人に漢学の素養があったからである.漢訳に当たっては,古来の漢語を利用したり,W. Lobscheid の『英華字典』を参照したり(例えば,文学,教育,内閣,国会,階級,伝記など)して対処したものもあったが,和製漢語を作り出す場合が多かった.この大量の新漢語は「漢語の氾濫」問題を惹起し,一般庶民にまで影響を及ぼすことになった.

例えば,『日本語百科大事典』 (453--54) によれば,『都鄙新聞』第1号(慶應4・明治1)に「此は頃鴨東ノの芸妓,少女ニ至ルマデ,専ラ漢語ヲツカフコトヲ好ミ,霖雨ニ盆地ノ金魚ガ脱走シ,火鉢ガ因循シテヰルナド,何ノワキマヘモナクイヒ合フコトコレナリ」という皮肉が聞かれたし,『漢語字類』(明治2)には「方今奎運盛ニ開ケ,文化日ニ新タナリ.上ミハ朝廷ノ政令,方伯ノ啓奏ヨリ,下モ市井閭閻ノ言談論議ニ至ルマデ,皆多ク雑ユルニ漢語ヲ以テス」とある.『我楽多珍報』(明治14. 9. 30)では「生意気な猫ハ漢語で無心いひ」とまである.このように新漢語が流行していたようだが,庶民がどの程度理解していたかは疑問で,「チンプン漢語」とまで呼ばれていたほどである."inkhorn terms" や「カタカナ語」という呼称と比較されよう.そして,漢語を統合する試みの1つとして,漢語字引が次々と出版されたことも,他の2例と驚くほどよく似ている.

現代日本語のカタカナ語問題を議論するのに,16世紀後半のイングランドや19世紀後半の日本の言語事情を参照することは,意味のあることだろう.

・ Bragg, Melvyn. The Adventure of English. New York: Arcade, 2003.

・ 『日本語百科大事典』 金田一 春彦ほか 編,大修館,1988年.

2013-08-20 Tue

■ #1576. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (3) [verb][conjugation][emode][number][agreement][analogy][3pp]

[2013-03-10-1], [2013-03-20-1]に引き続き,標記の話題.北部方言影響説か3単現からの類推説かで見解が分かれている.初期近代英語を扱った章で,Fennell (143) は後者の説を支持して,次のように述べている.

In the written language the third person plural had no separate ending because of the loss of the -en and -e endings in Middle English. The third person singular ending -s was therefore frequently used also as an ending in the third person plural: troubled minds that wakes; whose own dealings teaches them suspect the deeds of others. The spread of the -s ending in the plural is unlikely to be due to the influence of the northern dialect in the South, but was rather due to analogy with the singular, since a certain number of southern plurals had ended in -e)th like the singular in colloquial use. Plural forms ending in -(e)th occur as late as the eighteenth century.

一方,Strang (146) は北部方言影響説を支持している.

The function of the ending, whatever form it took, also wavered in the early part of II [1770--1570]. By northern custom the inflection marked in the present all forms of the verb except first person, and under northern influence Standard used the inflection for about a century up to c. 1640 with occasional plural as well as singular value.

構造主義の英語史家 Strang の議論が興味深いのは,2点の指摘においてである.1点目は,初期近代英語の同時期に,古い be に代わって新しい are が用いられるようになったのは北部方言の影響ゆえであるという事実と関連させながら,3単・複現の -s について議論していることだ.are が疑いなく北部方言からの借用というのであれば,3複現の -s も北部方言からの借用であると考えるのが自然ではないか,という議論だ.2点目は,主語の名詞句と動詞の数の一致に関する共時的かつ通時的な視点から,3複現の -s が生じた理由ではなく,それがきわめて稀である理由を示唆している点である.上の引用文に続く箇所で,次のように述べている.

The tendency did not establish itself, and we might guess that its collapse is related to the climax, at the same time, of the regularisation of noun plurality in -s. Though the two developments seem to belong to very different parts of the grammar, they are interrelated in syntax. Before the middle of II there was established the present fairly remarkable type of patterning, in which, for the vast majority of S-V concords, number is signalled once and once only, by -s (/s/, /z/, /ɪz/), final in the noun for plural, and in the verb for singular. This is the culmination of a long movement of generalisation, in which signs of number contrast have first been relatively regularised for components of the NP, then for the NP as a whole, and finally for S-V as a unit.

名詞の複数の -s と動詞の3単現の -s の交差的な配列を,数を巡る歴史的発達の到達点ととらえる洞察は鋭い.3複現の出現が北部方言の影響か3単現からの類推かのいずれかに帰せられるにせよ,生起は稀である.なぜ稀であるかという別の問題にすり替わってはいるが,当初の純粋に形態的な問題が統語的な話題,通時的な次元へと広がってゆくのを感じる.

・ Fennell, Barbara A. A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001.

・ Strang, Barbara M. H. A History of English. London: Methuen, 1970.

2013-07-16 Tue

■ #1541. Mind you の語順 [imperative][word_order][syntax][emode]

現代英語では,2人称に対する命令文では,通常,主語の you は省略される.ただし,相手に対するいらだちを表わしたり,特定の人を指して命令する場合には,会話において you が現われることも少なくない.その場合には "Come on! You open up and tell me everything." のように,you が動詞の前位置に置かれ,強勢を伴う.

しかし,初期近代英語までは,主語の you や thou が省略されずに表出する場合には,動詞の後位置に現われた.荒木・宇賀治 (406) および細江 (149) に引用されている,Shakespeare や聖書からの例を挙げよう.

・ Bring thou the master to the citadel (Oth II. i. 211)

・ So in the Lethe of thy angry soul Thou drown the sad remembrance of those wrongs Which thou supposest I have done to thee. (R 3 IV. iv. 250--2)

・ So speak ye, and do so. --- James, ii. 12.

・ Go, and do thou likewise. --- Luke, x. 37.

18世紀以降は,主語が動詞に前置される語順が次第に優勢となったが,否定命令文では,いまだに "Don't you be so sure of yourself." のように,you は don't の後位置に置かれる(強勢は don't のほうに落ちる).これは,古い英語の名残である.同様の名残に,現代英語の mind you, mark you, look you なども挙げられる.これらの you は動詞の目的語ではなく,あくまで命令文において明示された主語である.いずれも,「いいかい,よく聞け,忘れるな,言っておくが」ほどの意味で,略式の発話において内緒話を導入するときや聞き手の注意を引くときに用いる.you に強勢が置かれる.

・ Mind you, this is just between you and me.

・ Cellphones are becoming more and more popular. Mind you, I don't like cellphones.

・ I've heard they're getting divorced. Mind you, I'm not surprised --- they were always arguing.

・ She hasn't had much success yet. Mark you, she tries hard.

・ Her uncle's just given her a car --- given, mark you, not lent.

OED によると,mind you の初例は1768年(語義12b),mark you は Shakespeare (語義27b),look you も Shakespeare (語義4a)であり,近代英語期からの語法ということになる.なお,Look ye. 「見よ」については,「#781. How d'ye do?」 ([2011-06-17-1]) の記事も参照.

・ 荒木 一雄,宇賀治 正朋 『英語史IIIA』 英語学大系第10巻,大修館書店,1984年.

・ 細江 逸記 『英文法汎論』3版 泰文堂,1926年.

2013-05-13 Mon

■ #1477. The Salamanca Corpus --- 近代英語方言コーパス [corpus][emode][dialect][dialectology][caxton][popular_passage]

英語史では,中英語の方言研究は盛んだが,近代英語期の方言研究はほとんど進んでいない.「#1430. 英語史が近代英語期で止まってしまったかのように見える理由 (2)」 ([2013-03-27-1]) でも触れた通り,近代英語期は英語が標準化,規範化していった時期であり,現代世界に甚大な影響を及ぼしている標準英語という視点に立って英語史を研究しようとすると,どうしても標準変種の歴史を追うことに専心してしまうからかもしれない.その結果か,あるいは原因か,近代英語方言テキストの収集や整理もほとんど進んでいない状況である.近代英語の方言状況を知る最大の情報源は,いまだ「#869. Wright's English Dialect Dictionary」 ([2011-09-13-1]) であり,「#868. EDD Online」 ([2011-09-12-1]) で紹介した通り,そのオンライン版が利用できるようになったとはいえ,まだまだである.

2011年より,University of Salamanca がこの分野の進展を促そうと,近代英語期 (c.1500--c.1950) の方言テキストの収集とデジタル化を進めている.The Salamanca Corpus: Digital Archive of English Dialect Texts は,少しずつ登録テキストが増えてきており,今後,貴重な情報源となってゆくかもしれない.

コーパスというよりは電子テキスト集という体裁だが,その構成は以下の通りである.まず,内容別に DIALECT LITERATURE と LITERARY DIALECTS が区別される.前者は方言で書かれたテキスト,後者は方言について言及のあるテキストである.次に,テキストの年代により1500--1700年, 1700--1800年, 1800--1950年へと大きく3区分され,さらに州別の整理,ジャンル別の仕分けがなされている.

コーパスに収録されている最も早い例は,LITERARY DIALECTS -> 1500--1700年 -> The Northern Counties -> Prose と追っていったところに見つけた William Caxton による Eneydos の "Prologue"(1490年)だろう.テキストは221語にすぎないが,こちらのページ経由で手に入る.[2010-03-30-1]の記事「#337. egges or eyren」で引用した,卵をめぐる方言差をめぐる話しを含む部分である.やや小さいが,刊本画像も閲覧できる.Caxton の言語観を知るためには,[2010-03-30-1]の記事で引用した前後の文脈も重要なので,ぜひ一読を.

2013-05-08 Wed

■ #1472. ルネサンス期の聖書翻訳の言語的争点 [bible][renaissance][emode][methodology][reformation]

「#1427. 主要な英訳聖書に関する年表」 ([2013-03-24-1]) から明らかなように,16世紀は様々な聖書が爆発的に出版された時代だった(もう1つの爆発期は20世紀).当時は宗教改革の時代であり,様々なキリスト教派の存在,古典語からの翻訳の長い伝統,出版の公式・非公式の差など諸要素が絡み合い,異なる版の出現を促した.当然ながら,各版は独自の目的や問題意識をもっており,言語的な点においても独自のこだわりをもっていた.では,この時代の聖書翻訳家たちが関心を寄せていた言語的争点とは,具体的にどのようなものだったのだろうか.Görlach (5) によれば,以下の4点である.

1. Should a translator use the Latin or Greek/Hebrew sources?

2. Should translational equivalents be fixed, or varying renderings be permitted according to context? (cf. penitentia = penance, penitence, amendment)

3. To what extent should foreign words be permitted or English equivalents be used, whether existing lexemes or new coinages (cf. Cheke's practice)?

4. How popular should the translator's language be? There was a notable contrast between the Protestant tradition (demanding that the Bible should be accessible to all) and the Catholic (claiming that even translated Bibles needed authentic interpretation by the priest). Note also that dependence on earlier versions increased the conservative, or even archaic character of biblical diction from the sixteenth century on

それぞれの問いへの答えは,翻訳家によって異なっており,これが異なる聖書翻訳の出版を助長した.まったく同じ形ではないにせよ,20--21世紀にかけての2度目の聖書出版の爆発期においても,これらの争点は当てはまるのではないか.

さて,英語史の研究では,異なる時代の英訳聖書を比較するという手法がしばしば用いられてきたが,各版のテキストの異同の背景に上のような問題点が関与していたことは気に留めておくべきである.複数の版のあいだの単純比較が有効ではない可能性があるからだ.Görlach (6) によれば,より一般的な観点から,聖書間の単純比較が成立しない原因として次の4点を挙げている.

1. the translators used different sources;

2. older translations were used for comparison;

3. the source was misunderstood or interpreted differently;

4. concepts and contexts were absent from the translator's language and culture.

様々な英訳聖書の存在が英語史研究に貴重な資料を提供してくれたことは間違いない.だが,英語史研究の方法論という点からみると,相当に複雑な問題を提示してくれていることも確かである.

・ Görlach, Manfred. The Linguistic History of English. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997.

2013-04-29 Mon

■ #1463. euphuism [style][literature][inkhorn_term][johnson][emode][renaissance][alliteration][rhetoric]

「#292. aureate diction」 ([2010-02-13-1]) で,15世紀に発生したラテン借用語を駆使する華麗語法について見た.続く16世紀には,inkhorn_term と呼ばれるほどのラテン語かぶれした語彙が押し寄せた.これに伴い,エリザベス朝の文体はラテン作家を範とした技巧的なものとなった.この技巧は John Lyly (1554--1606) によって最高潮に達した.Lyly は,Euphues: the Anatomy of Wit (1578) および Euphues and His England (1580) において,後に標題にちなんで呼ばれることになった euphuism (誇飾体)という華麗な文体を用い,初期の Shakespeare など当時の文芸に大きな影響を与えた.

euphuism の特徴としては,頭韻 (alliteration),対照法 (antithesis),奇抜な比喩 (conceit),掛けことば (paronomasia),故事来歴への言及などが挙げられる.これらの修辞法をふんだんに用いた文章は,不自然でこそあれ,人々に芸術としての散文の魅力をおおいに知らしめた.例えば,Lyly の次の文を見てみよう.

If thou perceive thyself to be enticed with their wanton glances or allured with their wicket guiles, either enchanted with their beauty or enamoured with their bravery, enter with thyself into this meditation.

ここでは,enticed -- enchanted -- enamoured -- enter という語頭韻が用いられているが,その間に wanton glances と wicket guiles の2重頭韻が含まれており,さらに enchanted . . . beauty と enamoured . . . bravery の組み合わせ頭韻もある.

euphuism は17世紀まで見られたが,17世紀には Sir Thomas Browne (1605--82), John Donne (1572--1631), Jeremy Taylor (1613--67), John Milton (1608--74) などの堂々たる散文が現われ,世紀半ばからの革命期以降には John Dryden (1631--1700) に代表される気取りのない平明な文体が優勢となった.平明路線は18世紀へも受け継がれ,Joseph Addison (1672--1719), Sir Richard Steele (1672--1729), Chesterfield (1694--1773),また Daniel Defoe (1660--1731), Jonathan Swift (1667--1745) が続いた.だが,この平明路線は,世紀半ば,Samuel Johnson (1709--84) の荘重で威厳のある独特な文体により中断した.

初期近代英語期の散文文体は,このように華美と平明とが繰り返されたが,その原動力がルネサンスの熱狂とそれへの反発であることは間違いない.ほぼ同時期に,大陸諸国でも euphuism に相当する誇飾体が流行したことを付け加えておこう.フランスでは préciosité,スペインでは Gongorism,イタリアでは Marinism などと呼ばれた(ホームズ,p. 118).

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

・ 石橋 幸太郎 編 『現代英語学辞典』 成美堂,1973年.

・ U. T. ホームズ,A. H. シュッツ 著,松原 秀一 訳 『フランス語の歴史』 大修館,1974年.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow