2024-04-03 Wed

■ #5455. 矢冨弘先生との heldio トークと「日英の口の可動域」 [voicy][heldio][helwa][phonetics][pronunciation][japanese][do-periphrasis][emode][sociolinguistics][name_project][vowel][helkatsu]

先日,英語史研究者である矢冨弘先生(熊本学園大学)とお会いする機会がありました.「名前プロジェクト」 (name_project) の一環として,他のプロジェクトメンバーのお二人,五所万実先生(目白大学)と小河舜先生(上智大学)もご一緒でした.

そこで主に「名前」の問題をめぐり Voicy heldio/helwa の生放送をお届けしたり収録したりしました.以下の3本をアーカイヴより配信しています.いずれも長めですので,お時間のあるときにでもお聴きいただければ.

(1) heldio 「#1034. 「名前と英語史」 4人で生放送 【名前プロジェクト企画 #3】」(59分)

(2) helwa 「【英語史の輪 #113】「名前と英語史」生放送のアフタートーク生放送」(←こちらの回のみ有料のプレミアム限定配信です;60分)

(3) heldio 「#1038. do から提起する新しい英語史 --- Ya-DO-me 先生(矢冨弘先生)教えて!」(20分)

その後,矢冨先生がご自身のブログにて,上記の収録と関連する内容の記事を2本書かれていますので,ご紹介します.

・ 「3月末の遠征と4月の抱負」

・ 「日英の口の可動域」

2つめの「日英の口の可動域」は,上記 (2) の helwa 生放送中に,名前の議論から大きく逸れ,発音のトークに花が咲いた折に飛びだした話題です.トーク中に,矢冨先生が日本語と英語では口の使い方(母音の調音点)が異なることを日頃から意識されていると述べ,場が湧きました.英語で口の可動域が異なることを示す図をお持ちだということも述べられ,その後リスナーの方より「その図が欲しい」との要望が出されたのを受け,このたびブログで共有していただいた次第です.皆さん,ぜひ英語の発音練習に活かしていただければ.

ちなみに,矢冨先生についてもっと詳しく知りたい方は,khelf 発行の『英語史新聞』第6号と第7号をご覧ください.それぞれ第3面の「英語史ラウンジ by khelf」にて,2回にわたり矢冨先生のインタビュー記事を掲載しています.

矢冨先生,今後も様々な「hel活」 (helkatsu) をよろしくお願いします!

2023-12-12 Tue

■ #5342. 切り取り (clipping) による語形成の類型論 [word_formation][shortening][abbreviation][clipping][terminology][polysemy][homonymy][morphology][typology][apostrophe][hypocorism][name_project][onomastics][personal_name][australian_english][new_zealand_english][emode][ame_bre]

語形成としての切り取り (clipping) については,多くの記事で取り上げてきた.とりわけ形態論の立場から「#893. shortening の分類 (1)」 ([2011-10-07-1]) で詳しく紹介した.

先日12月8日の Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ」 (heldio) の配信回にて「#921. 2023年の英単語はコレ --- rizz」と題して,clipping による造語とおぼしき最新の事例を取り上げた.

この配信回では,2023年の Oxford Word of the Year が rizz に決定したというニュースを受け,これが charisma の clipping による短縮形であることを前提として charisma の語源を紹介した.

rizz が charisma の clipping による語形成であることを受け入れるとして,もとの単語の語頭でも語末でもなく真ん中部分が切り出された短縮語である点は特筆に値する.このような語形成は,それほど多くないと見込まれるからだ.「#893. shortening の分類 (1)」 ([2011-10-07-1]) の "Mesonym" で取り上げたように,例がないわけではないが,やはり珍しいには違いない.以下の解説によると "fore-and-aft clipping" と呼んでもよい.

heldio のリスナーからも関連するコメント・質問が寄せられたので,この問題と関連して McArthur の英語学用語辞典より "clipping" を引用しておきたい (223--24) .

CLIPPING [1930s in this sense]. Also clipped form, clipped word, shortening. An abbreviation formed by the loss of word elements, usually syllabic: pro from professional, tec from detective. The process is attested from the 16c (coz from cousin 1559, gent from gentleman 1564); in the early 18c, Swift objected to the reduction of Latin mobile vulgus (the fickle throng) to mob. Clippings can be either selective, relating to one sense of a word only (condo is short for condominium when it refers to accommodation, not to joint sovereignty), or polysemic (rev stands for either revenue or revision, and revs for the revolutions of wheels). There are three kinds of clipping:

(1) Back-clippings, in which an element or elements are taken from the end of a word: ad(vertisement), chimp(anzee), deli(catessen), hippo(potamus), lab(oratory), piano(forte), reg(ulation)s. Back-clipping is common with diminutives formed from personal names Cath(erine) Will(iam). Clippings of names often undergo adaptations: Catherine to the pet forms Cathie, Kate, Katie, William to Willie, Bill, Billy. Sometimes, a clipped name can develop a new sense: willie a euphemism for penis, billy a club or a male goat. Occasionally, the process can be humorously reversed: for example, offering in a British restaurant to pay the william.

(2) Fore-clippings, in which an element or elements are taken from the beginning of a word: ham(burger), omni(bus), violon(cello), heli(copter), alli(gator), tele(phone), earth(quake). They also occur with personal names, sometimes with adaptations: Becky for Rebecca, Drew for Andrew, Ginny for Virginia. At the turn of the century, a fore-clipped word was usually given an opening apostrophe, to mark the loss: 'phone, 'cello, 'gator. This practice is now rare.

(3) Fore-and-aft clippings, in which elements are taken from the beginning and end of a word: in(flu)enza, de(tec)tive. This is commonest with longer personal names: Lex from Alexander, Liz from Elizabeth. Such names often demonstrate the versatility of hypocoristic clippings: Alex, Alec, Lex, Sandy, Zander; Eliza, Liz, Liza, Lizzie, Bess, Betsy, Beth, Betty.

Clippings are not necessarily uniform throughout a language: mathematics becomes maths in BrE and math in AmE. Reverend as a title is usually shortened to Rev or Rev., but is Revd in the house style of Oxford University Press. Back-clippings with -ie and -o are common in AusE and NZE: arvo afternoon, journo journalist. Sometimes clippings become distinct words far removed from the applications of the original full forms: fan in fan club is from fanatic; BrE navvy, a general labourer, is from a 19c use of navigator, the digger of a 'navigation' or canal. . . .

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

2023-11-23 Thu

■ #5323. Shakespeare 時代の主な劇団 --- 井出新(著)『シェイクスピア それが問題だ!』(大修館,2023年)より [shakespeare][drama][emode][renaissance]

「#5316. Shakespeare の作品一覧(執筆年代順) --- 井出新(著)『シェイクスピア それが問題だ!』(大修館,2023年)より」 ([2023-11-16-1]) の表中に [A] Pembroke's Men [B] Strange's Men [C] Derby's Men [D] Chamberlain's Men [E] King's Men などのラベルがみえる.これは当該の作品と結びつけられている劇団の名前である.井出 (66--67) の「シェイクスピア時代の主な劇団(( )内は活動時期)と題するコラムがあるので,備忘録としてこちらにも記載しておきたい.こうしてみると劇団にも盛衰があるのだなあ.

■レスター伯一座 (Earl of Leicester's Men, 1559--88)

パトロンはロバート・ダドリー.伯爵に叙せられる1564年以前は「ダドリー一座として活動.地方巡業を多く行った.1570年代前半にジェイムズ・バーベッジ(リチャードの父)が所属.

■ウスター伯一座 (Earl of Worcester's Men, 1562--1603)

パトロンはウィリアム・サマーセットと息子エドワード.海外巡業を得意としたロバート・ブラウンや宮内大臣一座を脱退したウィリアム・ケンプが所属した.地方巡業を多く行なったが,1602年にボアズ・ヘッド館を拠点化し,宮内大臣一座や海軍大臣一座に次ぐ劇団となった.ジェイムズ一世即位後はアン王妃の庇護を受け,「アン王女一座」として1619年まで活動した.

■ストレインジ卿一座 (Lord Strange's Men, 1564--94)

パトロンはヘンリー・スタンリーと息子ファーディナンド.ジョン・ヘミングズやケンプが宮内大臣一座に加入する前に所属.1590年代はシアター座,ローズ座などを使用.1594年ファーディナンドの死去により団員はいくつかの劇団に離散,残留組は彼の弟ウィリアムの庇護下でダービー伯一座として活動した.

■王室礼拝堂少年劇団 (Children of the Chapel Royal, 1575--90, 1600--03)

1576年にリチャード・ファラント座長のもと,御前公演のリハーサルという建前で一般向け上演を開始.1600年以降はブラックフライアーズ座を拠点にベン・ジョンソンらの諷刺喜劇を上演して成人劇団を凌ぐ人気を得た.ジェイムズ即位後は(王妃)祝典少年劇団 (1603--13) として活動したが,1609年に拠点をホワイトフライアーズ座へと移してからは勢いが衰えた.

■聖ポール少年劇団 (Children of St Paul's, 1575--82, 1586--90, 1599--1606)

聖ポール大聖堂の聖歌隊を母体にして商業演劇に乗り出し,境内に建設された屋内劇場を拠点に活動.1600年代はジョン・マーストンやトマス・ミドルトンらによる諷刺喜劇で人気を博した.

■海軍大臣一座 (Lord Admiral's Men, 1576--1603)

パトロンはチャールズ・ハワード.海軍大臣に任じられる1585年までは「ハワーズ一座」として活動.1580年代後半に加入した名優エドワード・アレンの活躍によりロンドン二大劇団の一つとなった.興行師フィリップ・ヘンズロウの経営するローズ座とフォーチュン座を本拠地に活動した.→ヘンリー王子一座

■女王一座 (Queen's Men, 1583--94)

パトロンはエリザベス一世.枢密院の肝いりでリチャード・タールトンなど有名俳優をいろいろな劇団から引き抜いて結成された.1588年にタールトンが死去してからは次第に人気が凋落.地方巡業が多く,ロンドンではシアター座やカーテン座などを使用.

■ペンブルック伯一座 (Earl of Pembroke's Men, 1591--1601)

パトロンはヘンリー・ハーバート.宮内大臣一座に加入する以前シェイクスピアが一座に所属していたと推測する学者も多い.興行主フランシス・ラングリーの経営するスワン座が本拠地.

■宮内大臣一座 (Lord Chamberlain's Men, 1594--1603)

パトロンはヘンリー・ケアリと息子のジョージ.1594年にシェイクスピアやリチャード・バーベッジらを加えて新結成.幹部が共同経営するシアター座,グローブ座が本拠地.→国王一座

■国王一座 (King's Men, 1603--42)

パトロンはジェイムズ一世とチャールズ一世.ジェイムズは即位後の5月19日,宮内大臣一座の劇団員を庇護下に置き,彼らに特権的地位を与えた.本拠地はグローブ座,1609年以降は少年劇団が使用していたブラックフライアーズ座も拠点化した.

■ヘンリー王子一座 (1603--12)

前身は海軍大臣一座.ジェイムズ一世の即位後,ヘンリー王子の庇護を得た.王子が1612年にチフスで死去した後は王女エリザベスの夫フリードリヒ五世をパトロンとして1624年まで活動するが,本拠地フォーチュン座消失(1621年)後は勢いが衰えた.

・ 井出 新 『シェイクスピア それが問題だ!』 大修館,2023年.

2023-11-18 Sat

■ #5318. シェイクスピアの言語は "speaking picture" [shakespeare][drama][emode][literature][link]

McKeown のシェイクスピアの言語論を読んだ.英語史のハンドブックのなかに納められている,"Shakespeare's Literary Language" と題する9ページほどのさほど長くない導入的エッセーである.結論的にいえば,沙翁の言語は "speaking picture" であるということだ.これは「語る絵画」と訳せばよいのだろうか.言葉によって,あたかも絵画を鑑賞しているような雰囲気に誘う,というほどの理解でよいだろうか.

その効果が最もよく発揮されているのが「独白」であるという.シェイクスピアといえば,確かに独白を思い浮かべる人も多いだろう.エッセーの締めくくりに次のようにある.

There is much more to Shakespeare the poet than the soliloquy or the monologue but there is nothing more Shakespeare than this poetic mode. If we recognize that it derives from a tradition that regards poetry as a "speaking picture" that teaches and delights, we can give some critical substance to the oft made suggestion that Shakespeare, more than anyone else, teaches us what it means to be human. For what is definitive about human beings if not self-consciousness, and what is self-consciousness if not the capacity to act as witnesses to our own lives, to separate ourselves from our experiences, however blissful or devastating, and give them voice?

沙翁については,本ブログでも shakespeare の各記事で取り上げてきたし,Voicy heldio でも話題にしてきた.主要なコンテンツを列挙しておこう.今後も多く取り上げていきたい.

・ hellog 「#195. Shakespeare に関する Web resources」 ([2009-11-08-1])

・ hellog 「#1763. Shakespeare の作品と言語に関する雑多な情報」 ([2014-02-23-1])

・ hellog 「#2283. Shakespeare のラテン語借用語彙の残存率」 ([2015-07-28-1])

・ hellog 「#4341. Shakespeare にみられる4体液説」 ([2021-03-16-1])

・ hellog 「#4250. Shakespeare の言語の研究に関する3つの側面と4つの目的」 ([2020-12-15-1])

・ hellog 「#4285. Shakespeare の英語史上の意義?」 ([2021-01-19-1])

・ hellog 「#4482. Shakespeare の発音辞書?」 ([2021-08-04-1])

・ hellog 「#4483. Shakespeare の語彙はどのくらい豊か?」 ([2021-08-05-1])

・ hellog 「#5316. Shakespeare の作品一覧(執筆年代順) --- 井出新(著)『シェイクスピア それが問題だ!』(大修館,2023年)より」 ([2023-11-16-1])

・ heldio 「#898. 井出新先生のご著書の紹介 --- 『シェイクスピア それが問題だ!』(大修館,2023年)」

・ McKeown, Adam. N. "Shakespeare's Literary Language." Chapter 44 of A Companion to the History of the English Language. Ed. Haruko Momma and Michael Matto. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. 455--63.

2023-07-31 Mon

■ #5208. 田辺春美先生と17世紀の英文法について対談しました [voicy][heldio][review][corpus][emode][syntax][phrasal_verb][subjunctive][complementation]

6月に開拓社より近代英語期の文法変化に焦点を当てた『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』が出版されました.秋元実治先生(青山学院大学名誉教授)による編著です.6名の研究者の各々が,15--20世紀の各世紀の英文法およびその変化について執筆しています.

このたび,本書の第3章「17世紀の文法的・構文的変化」の執筆を担当された田辺春美先生(成蹊大学)と,Voicy heldio での対談が実現しました.17世紀は英語史上やや地味な時代ではありますが,着実に変化が進行していた重要な世紀です.ことさらに取り上げられることが少ない世紀ですので,今回の対談はむしろ貴重です.「#790. 『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』 --- 田辺春美先生との対談」をお聴き下さい(21分ほどの音声配信です).

田辺先生の最後の台詞「17世紀も忘れないでね~」が印象的でしたね.

本書については,すでに YouTube 「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」,hellog, heldio などの各メディアで紹介してきましたので,そちらもご参照いただければ幸いです.

・ YouTube 「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」より「#137. 辞書も規範文法も18世紀の産業革命富豪が背景に---故山本史歩子さん(英語・英語史研究者)に捧ぐ---」

・ hellog 「#5166. 秋元実治(編)『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』(開拓社,2023年)」 ([2023-06-19-1])

・ hellog 「#5167. なぜ18世紀に規範文法が流行ったのですか?」 ([2023-06-20-1])

・ hellog 「#5182. 大補文推移の反対?」 ([2023-07-05-1])

・ hellog 「#5186. Voicy heldio に秋元実治先生が登場 --- 新刊『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』についてお話しをうかがいました」 ([2023-07-09-1])

・ heldio 「#769. 『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』 --- 秋元実治先生との対談」

・ heldio 「#772. 『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』 --- 16世紀の英語をめぐる福元広二先生との対談」

・ heldio 「#790. 『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』 --- 田辺春美先生との対談」

・ 秋元 実治(編),片見 彰夫・福元 広二・田辺 春美・山本 史歩子・中山 匡美・川端 朋広・秋元 実治(著) 『近代英語における文法的・構文的変化』 開拓社,2023年.

2023-05-12 Fri

■ #5128. 17世紀の普遍文字への関心はラテン語の威信の衰退が一因 [writing_system][alphabet][latin][prestige][emode][history_of_linguistics][orthoepy][orthography][pictogram]

スペリングの英語史を著わした Horobin によると,17世の英語社会には従来のローマン・アルファベットではなく万国共通の普遍文字を考案しようとする動きが生じていた.

16--17世紀には正音学 (orthoepy) が発達し,それに伴って正書法 (orthography) への関心も高まった時代だが,そこで常に問題視されたのはローマン・アルファベットの不完全性だった.この問題意識のもとで,完全なる普遍的な文字体系が模索されることになったことは必然といえば必然だった.しかし,17世紀の普遍文字の考案の動きにはもう1つ,同時代に特有の要因があったのではないかという.それは長らくヨーロッパ社会で普遍言語として認識されてきたラテン語の衰退である.古い普遍「言語」が失われかけたときに,新しい普遍「文字」が模索されるようになったというのは,時代の流れとしておもしろい.Horobin (25) より引用する.

Attempts have also been made to devise alphabets to overcome the difficulties caused by this mismatch between figura and potestas. In the seventeenth century, a number of scholars attempted to create a universal writing system which could be understood by everyone, irrespective of their native language. This determination was motivated in part by a dissatisfaction with the Latin alphabet, which was felt to be unfit for purpose because of its lack of sufficient letters and because of the differing ways it was employed by the various European languages. The seventeenth century also witnessed the loss of Latin as a universal language of scholarship, as scholars increasingly began to write in their native tongues. The result was the creation of linguistic barriers, hindering the dissemination of ideas. This could be overcome by the creation of a universal writing system in which characters represented concepts rather than sounds, thereby enabling scholars to read works composed in any language. This search for a universal writing system was prompted in part by the mistaken belief that the Egyptian system of hieroglyphics was designed to represent the true essence and meaning of an object, rather than the name used to refer to it. Some proponents of a universal system were inspired by the Chinese system of writing, although this was criticized by others on account of the large number of characters required and for the lack of correspondence between the shapes of the characters and the concepts they represent.

21世紀の現在,普遍文字としての絵文字やピクトグラム (pictogram) の可能性に注目が寄せられている.現代における普遍言語というべき英語が17世紀のラテン語のように衰退しているわけでは必ずしもないものの,現代の普遍文字としてのピクトグラムの模索への関心が高まっているというのは興味深い.17世紀と現代の状況はどのように比較対照できるだろうか.

関連して「#2244. ピクトグラムの可能性」 ([2015-06-19-1]),「#422. 文字の種類」 ([2010-06-23-1]) を参照.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ サイモン・ホロビン(著),堀田 隆一(訳) 『スペリングの英語史』 早川書房,2017年.

2023-03-31 Fri

■ #5086. この30年ほどの英語歴史綴字研究の潮流 [spelling][orthography][sociolinguistics][historical_pragmatics][history_of_linguistics][emode][standardisation][variation]

Cordorelli (5) によると,直近30年ほどの英語綴字に関する歴史的な研究は,広い意味で "sociolinguistic" なものだったと総括されている.念頭に置いている中心的な時代は,後期中英語から初期近代英語にかけてだろうと思われる.以下に引用する.

The first studies to investigate orthographic developments in English within a diachronic sociolinguistic framework appeared especially from the late 1990s and the early 2000s . . . . The main focus of these studies was on the diffusion of early standard spelling practices in late fifteenth-century correspondence, the development of standard spelling practices, and the influence of authors' age, gender, style, social status and social networks on orthographic variation. Over the past few decades, book-length contributions with a relatively strong sociolinguistic stance were also published . . . . These titles have touched upon different aspects of spelling patterns and change, providing useful frameworks of analysis and ideas for new angles of research in English orthography.

一言でいえば,綴字の標準化 (standardisation) の過程は,一本線で描かれるようなものではなく,常に社会的なパラメータによる変異を伴いながら,複線的に進行してきたということだ.そして,このことが30年ほどの研究で繰り返し確認されてきた,ということになろう.

英語史において言語現象が変異を伴って複線的に推移してきたことは,何も綴字に限ったことではない.ここ数十年の英語史研究では,発音,形態,統語,語彙のすべての側面において,同趣旨のことが繰り返し主張されてきた.学界ではこのコンセンサスがしっかりと形成され,ほぼ完全に定着してきたといってよいが,学界外の一般の社会には「一本線の英語史」という見方はまだ根強く残っているだろう.英語史研究者には,この新しい英語史観を広く一般に示し伝えていく義務があると考える.

過去30年ほどの英語歴史綴字研究を振り返ってみたが,では今後はどのように展開していくのだろうか.Cordorelli はコンピュータを用いた量的研究の新たな手法を提示している.1つの方向性として注目すべき試みだと思う.

・ Cordorelli, Marco. Standardising English Spelling: The Role of Printing in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Graphemic Developments. Cambridge: CUP, 2022.

2023-03-29 Wed

■ #5084. 現代英語の綴字は初期近代英語期の産物である [spelling][orthography][emode][standardisation][link]

現代英語の標準綴字はいつ成立したか.英語の標準化 (standardisation) の時期をピンポイントで指摘することは難しい.言語の標準化の過程は,多かれ少なかれ緩慢に進行していくものだからだ(cf. 「#2321. 綴字標準化の緩慢な潮流」 ([2015-09-04-1])).

私はおおよその確立を1650年辺りと考えているが,研究者によってはプラスマイナス百数十年の幅があるだろうことは予想がつく.「#4093. 標準英語の始まりはルネサンス期」 ([2020-07-11-1]) で見たように,緩く英国ルネサンス期 (renaissance),あるいはさらに緩く初期近代英語期 (emode) と述べておくのが最も無難な答えだろう.

実際,Cordorelli による英語綴字の標準化に関する最新の研究書の冒頭でも "the Early Modern Era" と言及されている (1) .

English spelling is in some ways a product of the Early Modern Era. The spelling forms that we use today are the result of a long process of conscious development and change, most of which occurred between the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries. This portion of history is marked by a number of momentous events in England and the Continent, which had an immediate effect on English culture and language.

初期近代英語期とその前後に生じた様々な歴史的出来事や社会的潮流が束になって,英語綴字の標準化を推し進めたといってよい.現代につらなる正書法は,この時代に,諸要因の複雑な絡み合いのなかから成立してきたものなのである.以下に関連する記事へのリンクを挙げておく.

・ 「#297. 印刷術の導入は英語の標準化を推進したか否か」 ([2010-02-18-1])

・ 「#871. 印刷術の発明がすぐには綴字の固定化に結びつかなかった理由」 ([2011-09-15-1])

・ 「#1312. 印刷術の発明がすぐには綴字の固定化に結びつかなかった理由 (2)」 ([2012-11-29-1])

・ 「#1384. 綴字の標準化に貢献したのは17世紀の理論言語学者と教師」 ([2013-02-09-1])

・ 「#1385. Caxton が綴字標準化に貢献しなかったと考えられる根拠」 ([2013-02-10-1])

・ 「#1386. 近代英語以降に確立してきた標準綴字体系の特徴」 ([2013-02-11-1])

・ 「#1939. 16世紀の正書法をめぐる議論」 ([2014-08-18-1])

・ 「#2321. 綴字標準化の緩慢な潮流」 ([2015-09-04-1])

・ 「#3243. Caxton は綴字標準化にどのように貢献したか?」 ([2018-03-14-1])

・ 「#3564. 17世紀正音学者による綴字標準化への貢献」 ([2019-01-29-1])

・ 「#4628. 16世紀後半から17世紀にかけての正音学者たち --- 英語史上初の本格的綴字改革者たち」 ([2021-12-28-1])

・ Cordorelli, Marco. Standardising English Spelling: The Role of Printing in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Graphemic Developments. Cambridge: CUP, 2022.

2023-03-27 Mon

■ #5082. 語源的綴字の1文字挿入は植字工の懐を肥やすため? [etymological_respelling][emode][printing]

Cordorelli による初期近代英語期の綴字に関する新刊の研究書を読んでいる.そこでは語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の問題も詳しく論じられているのだが,興味深い説が提示されている.語源的綴字の多くの例は,dout に対する doubt,receit に対する receipt のように1文字長くなることが多い.労働時間ではなく植字文字数(より正確には文字幅の総量)で賃金を支払われるようになった16世紀の植字工は,文字数,すなわち稼ぎを増やすために,より長くなりがちな語源的綴字のほうを選んだのではないかという.もちろん文字数を水増しする方法は他にもいろいろあったと思われるが,語源的綴字もそのうちの1つだったのではないか,という議論だ.Cordorelli (184--85) の説明を引用する.

With regard to remuneration, large-scale etymological developments were initially prompted, I suggest, by a change in the economic organisation of the printing labour. From the turn of the sixteenth century, the mode of remuneration changed in accordance with the pressures exerted by modernisation: printers no longer received time-based wages, but were generally paid according to their output . . . . For typesetters, wages were set taking into account the kind of printing form, the publication format, the typefaces and the languages that were used in the texts . . . . As a result of a first move towards a performance-based pay, compositors' output also began to be measured, rather roughly, by the page or by the sheet; later, a more accurate measurement by ens was adopted. One en corresponded to half an em of any size of type, and the number of ens in a setting of type was proportional to the number of pieces of type used in it . . . . With compositors' output being measured by page first, and by ens later, typesetters became increasingly more prone to using as many types as possible when composing a book, while also having to make sure that the overall meaning of the text would not be corrupted by this practice. As a rule, the more types were used on a given page, the more ens were likely to result, which in turn meant that compositors would be paid a higher rate for a given project. Making the most of each typesetting project was more important than one might think, especially during the first half of the sixteenth century, when the English printing industry was still growing on unstable economic ground . . . . The flow of jobs that characterised most staff roles in the EModE printing industry was variable and often irregular for everyone, especially for compositors. The irregularity of the market could keep compositors short of work for long periods of time, and forced them either into part-time employment with another printer or even into joining the vast reservoir of employed labour . . . .

印刷術の発明,その産業化,植字工の雇用といった技術・経済上の要因が,初期近代英語期の語源的綴字の興隆と関わっているとなれば,これはたいへんおもしろいトピックである.この仮説を実証するには,当時の社会事情と綴字習慣を詳細に調査する必要があるだろう.

Cordorelli (185) 自身による要約となる1文も引用しておきたい.

From this point of view, etymological spelling would have worked as a convenient means to increase average pay, to such an extent that printers evidently compromised linguistic correctness with personal profit, accepting or perhaps even enforcing the diffusion of 'false' etymological spellings like phantasy and aunswar.

・ Cordorelli, Marco. Standardising English Spelling: The Role of Printing in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Graphemic Developments. Cambridge: CUP, 2022.

2023-02-20 Mon

■ #5047. 「大航海時代略年表」 --- 『図説大航海時代』より [timeline][history][age_of_discovery][me][emode][renaissance][link]

世界史上,ひときわきらびやかに映る大航海時代 (age_of_discovery) .広い視野でみると,当然ながら英語史とも密接に関わってくる(cf. 「#4423. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第10回「大航海時代と活版印刷術」を終えました」 ([2021-06-06-1])).

以下,『図説大航海時代』の巻末 (pp. 109--10) の略年表を掲載する.大航海時代の範囲についてはいくつかの考え方があるが,1415年のポルトガル軍によるセウタ占領に始まり,1648年のウェストファリア条約の締結に終わるというのが1つの見方である.しかし,下の略年表にみえるように,その前史は長い.

| 紀元前5世紀 | スキュラクス,インダス河口からスエズ湾まで航海 |

| 4世紀後半 | ネアルコス,インダス地方からティグリス河口まで探検 |

| 111 | 漢の武帝,南越を併合 |

| 1世紀 | カンボジヤ南部に扶南国興る |

| 60--70頃 | 『エリュトラ海案内記』 |

| 1世紀前半 | 「ヒッパロスの風」によるアラビア海航海がさかんになる |

| 2世紀 | 扶南とローマ,インドと中国の交易がおこなわれる |

| 166 | 大秦王安敦(マルクス・アウレリウス)の支社日南郡に至る |

| 207 | 南越国建国 |

| 4--5世紀 | 東南アジアのインド化進む |

| 399--412 | 東晋の法顕のインド,セイロン旅行.『仏国記』を書く |

| 7世紀前半 | 扶南,真臘に併合される |

| 618 | 唐建国 |

| 639 | アラブ人のエジプト侵入 |

| 7世紀後半 | シュリーヴィジャヤ王国マラッカ海峡の交易を支配 |

| 671--95 | 唐の仏僧義浄インド滞在.『南海寄帰内法伝』 |

| 750 | バグダートにアッバース朝おこる.インド洋貿易に進出 |

| 875 | チャンパ(占城)興る |

| 907 | 唐滅亡.五代十国時代に入る |

| 960 | 宋建国.海外貿易の隆盛 |

| 969 | ファーティマ朝カイロに移る.紅海を通じてのアジア貿易.以後エジプトは紅海経由のインド洋貿易を主導する |

| 1096 | 第1次十字軍 (--99) .イタリア港市の台頭 |

| 1127 | 南宋興る |

| 1147 | 第2次十字軍 (--48) |

| 1169 | エジプトにアイユーブ朝成立 |

| 1245--47 | プラノ・カルピーニ,教皇の命によりカラコルムに至る旅行記を著わす |

| 1254 | リュブリュキ,教皇の命によりカラコルムまで旅行.旅行記を書く |

| 1258 | モンゴル軍バグダート占領.アッバース朝滅亡.ただしモンゴル軍はシリア,エジプトに侵入できず |

| 1271--95 | マルコ・ポロのアジア旅行と中国滞在.旅行記を口述 |

| 1291 | ジェノヴァのヴィヴァルディ兄弟西アフリカ航海 |

| 1293 | ジャヴァにマジャパヒト王国成立.モンゴル軍ジャヴァに侵攻 |

| 1312 | ジェノヴァのランチェローテ・マロチェーロ,カナリア諸島に航海 |

| 1349(ママ) | イブン・バトゥータ,24年にわたるアフリカ,アジア旅行からタンジールに帰る |

| 1336 | 南インドにヴィジャヤナガル王国興る |

| 1345 | マジャパヒト,全ジャヴァに勢力拡大 |

| 1351--54 | イブン・バトゥータ西アフリカ旅行.『三大陸周遊記』を書く |

| 1360 | マンデヴィルの『東方旅行記』この頃成立 |

| 1368 | 明建国 |

| 1372 | 明,海禁政策をとる |

| 1403 | スペインのクラビーホ,中央アジアに旅行しティムールに謁す.ラ・サルとベタンクール,カナリア諸島に航海 |

| 1405 | 鄭和の大航海.1433年まで7回にわたる |

| 1415 | ポルトガル軍セウタ占領.間もなく西アフリカ航路の探検が始まる |

| 1434 | ジル・エアネス,ボジャドール岬回航 |

| 1453 | オスマン軍によるコンスタンティノープル攻略 |

| 1455 | ヴェネツィア人カダモストの西アフリカ航海 |

| 1475 | ヴィチェンツァでプトレマイオスの『地理学』刊行 |

| 1479 | スペイン,ポルトガル間にアルカソヴァス条約 |

| 1482 | ポルトガルの西アフリカの拠点エルミナ建設.ポルトガル人コンゴ王国と接触 |

| 1488 | ディアスによる喜望峰発見.大航海時代 |

| 1492 | コロンブス第1回航海 (--93) |

| 1493 | コロンブス第2回航海 |

| 1494 | スペイン,ポルトガル間にトルデシリャス条約 |

| 1498 | ガマのインド航海.コロンブス第3回航海.南米本土に達する |

| 1500 | カブラル,インドへの途次ブラジルに漂着 |

| 1501 | アメリゴ・ヴェスプッチ南アメリカの南緯52°まで航海 |

| 1502 | コロンブス第4回航海.中米沿岸航海 |

| 1505 | トロ会議.西回りで香料諸島探検を議決 |

| 1508 | ブルゴス会議で同様な趣旨の議決 |

| 1509 | アルメイダ,ディウ沖で,エジプト,グジャラート連合艦隊撃破 |

| 1510 | ポルトガル,ゴア完全占領 |

| 1511 | ポルトガル,マラッカ攻略 |

| 1512 | ポルトガル人香料諸島に到着 |

| 1513 | バルボア,パナマ地峡を横断して太平洋岸に達する |

| 1519--21 | コルテスのメキシコ(アステカ王国)征服 |

| 1520 | マゼラン,地峡を発見し,太平洋を横断してフィリピンに至る |

| 1522 | エルカノ以下18人,最初の世界回航をとげてセビリャ着 |

| 1527 | モンテホのユカタン探検 |

| 1528--33 | ピサロのインカ帝国征服 |

| 1529 | サラゴッサ条約により香料諸島のポルトガル帰属決定 |

| 1534 | カルティエのカナダ探検 |

| 1535 | アルマグロのチリ探検 |

| 1537 | ケサーダのムイスカ(チブチャ)征服 |

| 1538 | 皇帝・教皇・ジェノヴァ連合艦隊プレヴェザでトルコ人に敗北 |

| 1541 | ゴンサーロ・ピサロのアマゾン探検.部下のオレリャーナ,河口まで航海 (1542) |

| 1543 | 三人のポルトガル人,種子島着 |

| 1545 | ボリビアのポトシ銀山発見,翌年メキシコでも大銀山発見 |

| 1553 | ウィロビーの北東航路探検 |

| 1565 | ウルダネータ,大圏航路によりフィリピンからメキシコまで航海 |

| 1567 | メンダーニャの太平洋航海.翌年ソロモン諸島発見 |

| 1568 | ジョン・ホーキンズ,サン・ファン・デ・ウルアでスペインの奇襲をうけて脱出 |

| 1570 | ドレイクのカリブ海スペイン基地の掠奪 |

| 1571 | レガスピ,マニラ市建設.キリスト教徒の海軍レパントでオスマン艦隊に勝利 |

| 1575 | フロビッシャー,北西航路探検の勅許を得る |

| 1577--80 | ドレイク,掠奪の世界周航をおこなう |

| 1578 | アルカサルーキヴィルでポルトガル軍モロッコ軍に大敗 |

| 1584--85 | ウォルター・ローリのヴァージニア植民計画 |

| 1586--88 | キャベンディシュの世界周航 |

| 1595 | ローリの第1次ギアナ探検.メンダーニャの太平洋探検,マルケサス諸島発見 |

| 1598 | ファン・ノールト,オランダ人として最初の世界周航 |

| 1599 | オランダ人ファン・ネック東インド航海 |

| 1600 | イギリス東インド会社設立.この頃ブラジルに砂糖産業が興り,アフリカ人奴隷の輸送始まる |

| 1605 | キロスの航海.ニュー・ヘブリデスまで |

| 1606 | キロク帰国後,あとに残されたトレス,ニュー・ギニア,オーストラリア間の海峡を発見し,マニラに向かう |

| 1610 | ハドソン,アニアン海峡を求めて行方不明になる |

| 1614 | メンデス・ピントの東洋旅行記『遍歴記』刊行 |

| 1615 | オランダ人スホーテンとル・メールの航海.ホーン岬発見 |

| 1617 | ローリ第2回ギアナ探検 |

| 1620 | メイフラワー号ニュー・イングランドに到着 |

| 1622 | インド副王の艦隊,モサンビケ沖でオランダ船隊の攻撃を受け壊滅 |

| 1623 | アンボイナ事件.オランダ人によるイギリス人,日本人の殺害.これ以後イギリス人は東インドの香料貿易から撤退し,インドに集中 |

| 1637 | オランダ人西アフリカのエルミナ奪取 |

| 1639 | マカオの対日貿易,鎖国のため不可能になる.タスマンの太平洋航海 |

| 1641 | オランダ人マラッカ奪取 |

| 1642--43 | タスマン,オーストラリアの輪郭を明らかにする |

| 1645 | オランダ人セント・ヘレナ島占領 |

| 1647 | オランダ,アンボイナ島完全占領.カサナーテのカリフォルニア探検 |

| 1648 | セミョン・デジニョフ,アジア最北東端の岬(デジニョフ岬)に到達.ただしベーリング海峡の存在には気がつかなかった.ウェストファリア条約の締結による三十年戦争の終わり.オランダの独立承認される |

hellog ではこれまでも関連する年表を多く掲載してきた.大航海時代との関連で,以下のリンクを挙げておこう.

・ 「#2371. ポルトガル史年表」 ([2015-10-24-1])

・ 「#3197. 初期近代英語期の主要な出来事の年表」 ([2018-01-27-1])

・ 「#3478. 『図説イギリスの歴史』の年表」 ([2018-11-04-1])

・ 「#3479. 『図説 イギリスの王室』の年表」 ([2018-11-05-1])

・ 「#3487. 『物語 イギリスの歴史(上下巻)』の年表」 ([2018-11-13-1])

・ 「#3497. 『イギリス史10講』の年表」 ([2018-11-23-1]) を参照.

・ 増田 義郎 『図説大航海時代』 河出書房新社,2008年.

2022-12-09 Fri

■ #4974. †splendidious, †splendidous, †splendious の惨めな頻度 --- EEBO corpus より [eebo][corpus][synonym][emode]

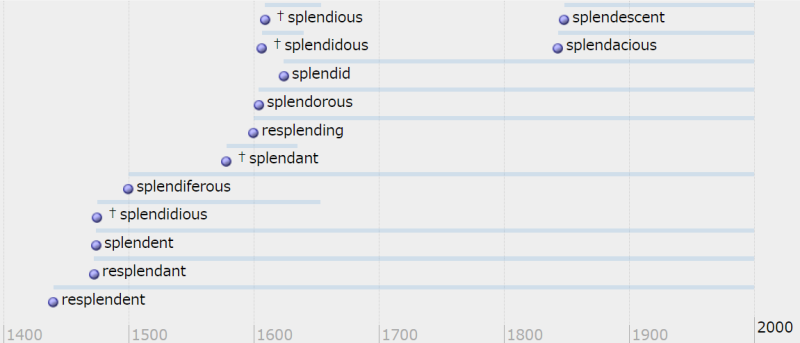

「#3157. 華麗なる splendid の同根類義語」 ([2017-12-18-1]),「#4969. splendid の同根類義語のタイムライン」 ([2022-12-04-1]) で,初期近代英語期を中心とする時期に splendid の同根類義語が多数生み出された話題を取り上げた.

そのなかでもとりわけ短命に終わった,3つの酷似した語尾をもつ †splendidious, †splendidous, †splendious について,EEBO corpus で検索し,頻度を確認してみた.参考までに,現在もっとも普通の splendid の頻度も合わせて,半世紀ごとに数値をまとめてみた.

| word | current by OED | C16b | C17a | C17b | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| †splendidious | ?a1475 (?a1425)--1653 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 17 |

| †splendidous | 1607--1640 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| †splendious | 1609--1654 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| splendid | 1624-- | 15 | 116 | 2534 | 2665 |

廃語となった3語は,現役中にも惨めな頻度だったことがわかるだろう.全体で2例しか挙がってこなかった splendious に至っては「現役」だったという表現すら当たらないかもしれない.この2つの例文を覗いてみよう(斜字体は筆者).2例目では先行する delicious が同じ語尾を取っている.

・ 1609: Ilands besides of much hostillitie, which are as sun-shine, sometimes splendious, anon disposed to altering frailtie

・ 1656: imagin madam, what a delicious life i lead, in so noble company, so splendious entertainment, and so magnificent equipage

この splendious などは,事実上その場で即席にフランス単語らしく造語された使い捨ての臨時語 (nonce word) といってよく,「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]) で解説した当時の時代精神をよく表わす事例ではないだろうか.「輝かしい」はずの形容詞だが,実際にはかりそめの存在だった.

2022-12-04 Sun

■ #4969. splendid の同根類義語のタイムライン [cognate][synonym][lexicology][inkhorn_term][emode][borrowing][loan_word][renaissance][oed][timeline]

すでに「#3157. 華麗なる splendid の同根類義語」 ([2017-12-18-1]) で取り上げた話題ですが,一ひねり加えてみました.splendid (豪華な,華麗な;立派な;光り輝く)というラテン語の動詞 splendēre "to be bright or shining" に由来する形容詞ですが,英語史上,数々の同根類義語が生み出されてきました.先の記事で触れなかったものも含めて OED で調べた単語を列挙すると,廃語も入れて13語あります.

resplendant, resplendent, resplending, splendacious, †splendant, splendent, splendescent, splendid, †splendidious, †splendidous, splendiferous, †splendious, splendorous

OED に記載のある初出年(および廃語の場合は最終例の年)に基づき,各語の一生をタイムラインにプロットしてみたのが以下の図です.とりわけ16--17世紀に新類義語の登場が集中しています.

ほかに1796年に初出の resplendidly という副詞や1859年に初出の many-splendoured という形容詞など,合わせて考えたい語もあります.いずれにせよ英語による「節操のない」借用(あるいは造語)には驚かされますね.

2022-10-14 Fri

■ #4918. William Bullokar の8品詞論 [history_of_linguistics][latin][emode][bullokar][pos][greek][latin]

「#2579. 最初の英文法書 William Bullokar, Pamphlet for Grammar (1586)」 ([2016-05-19-1]) でみたように,Bullokar (c. 1530--1609) による Pamphlet for Grammar (1586) という小冊子が,英語史上初の英文法書といわれている.今回は Bullokar の品詞区分を覗いてみたい.

まず,品詞区分について先立つ伝統を確認しておこう.古くアレクサンドリアで Dionysius Thrax (c. BC170--BC90) がギリシア語に8品詞を認めたのが出発点である.オノマ(名詞・形容詞),レーマ(動詞),メトケー(分詞),アルトロン(冠詞),アントーニュミアー(代名詞),プロテシス(前置詞),エピレーマ(副詞),シュンデスモス(接続詞)である(斎藤,p. 11).

これを受け継いだのが,後に絶大な影響力を誇るラテン語文法を著わした Donatus (c. 300--399) である.ただしラテン語には冠詞ないので取り除かれ,間投詞が加えられた.結果として数としては8品詞にとどまっている.名詞 (nomen),代名詞 (pronomen),動詞 (verbum),副詞 (adverbium),分詞 (participium),接続詞 (coniunctio),前置詞 (praepositio),間投詞 (interiectio) である.後の Priscianus (fl. 500) もこれに従った(斎藤,pp. 14--15).

時代は下って16世紀のイングランド.Donatus の影響のもと,1509年に出版された William Lily のラテン語文法の英訳版 Short Introduction of Grammar (1548) が一世を風靡していた.これに依拠して書かれたのが Bullokar の英文法書 Pamphlet for Grammar (1586) だったの.

ラテン語文法の伝統を受け継いで,Bullokar は英語にも8品詞を認めた.名詞,代名詞,動詞,副詞,分詞,接続詞,前置詞,間投詞である.Bullokar (115 (22)) の原文によると次のようにある(Bullokar 特有のスペリングにも注意).

Spech may be diuyded intoo on of thæȝ eiht parts: too wit, Nown, Pronoun, Verb (declyned). Participle, Aduerb, Coniunction, Preposition, Interiection, (vn-declyned).

つまり,8品詞の伝統は Thrax → Donatus → Lily → Bullokar とリレーしながら,1700年にわたり保持されてきたのである.そして,Bullokar の後も英文法では8品詞が受け継がれていくことになる.凄まじい伝統と継続の力だ.

・ 斎藤 浩一 『日本の「英文法」ができるまで』 研究社,2022年.

・ Bullokar, William . Bref Grammar and Pamphlet for Grammar. 『William Bullokar: Book at large, Bref Grammar and Pamphlet for Grammar. P. Gr.: Grammatica Anglicana. Edmund Coote: The English Schoole-maister』英語文献翻刻シリーズ第1巻.南雲堂,1971年.pp. 107--64.

2022-09-19 Mon

■ #4893. King's English と Queen's English の初出年代 [emode][monarch][oed][inkhorn_term][voicy][heldio]

今月8日にエリザベス女王 (Elizabeth II) が亡くなり,本日19日にウェストミンスター寺院にて国葬が営まれる予定とのことです.統治期間はイギリス史上最長の70年.まさに1つの歴史を刻んだ君主でした.そして,チャールズ国王 (Charles III) が新たに即位しました.

これまで Queen's English と呼ばれてきた,いわゆるイギリス標準英語は,今後は King's English という呼称に回帰することになると思います.この機会に King's English や Queen's English という呼び方について少々調べ,今朝の Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」にて「#476. King's English と Queen's English」と題してしゃべってみました.

放送内で触れた OED による両表現の初出について,以下で補っておきます.まず,King's English については,king, n. の下で,次のように説明と用例が与えられています.

King's English n. [apparently after king's coin n.] (chiefly with the) the English language regarded as under the guardianship of the King of England; (hence) standard or correct English, usually taken as that written and spoken by educated people in Britain; cf. Queen's English n. at queen n. Compounds 3b.

1553 T. Wilson Arte of Rhetorique iii. f. 86 These fine Englishe clerkes, will saie thei speake in their mother tongue, if a man should charge them for counterfeityng the kynges English.

a1616 W. Shakespeare Merry Wives of Windsor (1623) i. iv. 5 Abusing of Gods patience, and the Kings English.

1787 Eng. Rev. May 284 That fervent zeal which now displays itself among all ranks of persons,..to circulate the purity of the king's English among them.

1836 E. Howard Rattlin xxxv. 144 They..put the king's English to death so charmingly.

1941 W. J. Cash Mind of South i. i. 28 Smelly old fellows with baggy pants and a capacity for butchering the king's English.

2003 E. Stuart Entropy & Alchemy vi. 71 The British, custodians of the King's English and supposedly so careful and conscientious with words.

king's coin (硬貨に刻まれている国王の肖像画)からの類推ではないかということですが,どうなのでしょうか.ちなみに初出する1553年というのは,Edward VI が早世し Mary I が女王として即位した年でもあり,興味深いタイミングではあります.初例を提供している T(homas) Wilson については「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1]),「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1]),「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1]),「#2479. 初期近代英語の語彙借用に対する反動としての言語純粋主義はどこまで本気だったか?」 ([2016-02-09-1]),「#4093. 標準英語の始まりはルネサンス期」 ([2020-07-11-1]) などを参照.

次に Queen's English もみてみましょう.queen, n. の下で,次のように記述されています.初出する1592年は Elizabeth I の統治下です.

Queen's English n. (usually with the) the English language regarded as under the guardianship of the Queen of England; (hence) standard or correct English, usually as written and spoken by educated people in Britain; cf. King's English n. at king n. Compounds 5b.

1592 T. Nashe Strange Newes sig. B1v He must be running on the letter, and abusing the Queenes English without pittie or mercie.

a1753 P. Drake Memoirs (1755) II. iii. 81 He was pretty far overcome by the Champaign, for he clipped the Queen's English.

1848 Southern Literary Messenger 14 636/2 'On' yesterday, (another Southern emendation of the Queen's English, which is funny enough,) I was so unfortunate [etc.].

1867 F. S. Cozzens Sayings 82 In fact, that arbitrary style of speaking which is commonly known as the Queen's English.

1885 Punch 4 July 5/2 (heading) The Premier's Primer; or Queen's English as she is wrote.

1902 F. Hume Fever of Life 146 I! Oh, how can you? I speak the Queen's English.

1991 K. Waterhouse English our English p. xvii The more slipshod English in circulation, the wider the assumption that it doesn't matter any more, that the Queen's English is by now the quaint preserve of pedants.

2006 PC Gamer Apr. 79/1 This doesn't mean that the cast of characters suddenly speak the Queen's English with cut-glass accents and quote Shakespeare.

いずれも読ませる例文が選ばれており,さすが OED と感心します.両表現とも初出年代が16世紀というのが,またおもしろいところです.英国ルネサンスの真っ只中にあった当時,ラテン語やギリシア語などの古典語に対する憧れが高まっていましたが,その一方でヴァナキュラーである英語への自信も少しずつ深まってきていました.その国語の自信を支える「顔」として,政治上のトップである君主が選ばれたことは自然なことです.その伝統が現在まで400年以上続いているというのは,やはり息の長いことだと思います.

2022-05-27 Fri

■ #4778. 変わりゆく言葉に嘆いた詩人 Edmund Waller の "Of English Verse" [chaucer][language_change][hel_contents_50_2022][emode][literature]

khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)による「英語史コンテンツ50」が終盤を迎えている.今回の hellog 記事は,先日5月20日にアップされた院生によるコンテンツ「どこでも通ずる英語…?」にあやかり,そこで引用されていたイングランドの詩人 Edmund Waller による詩 "Of English Verse" を紹介したい.

Waller (1606--87年)は17世紀イングランドを代表する詩人で,文学史的にはルネサンスの終わりと新古典主義時代の始まりの時期をつなぐ役割を果たした.Waller は32行の短い詩 "Of English Verse" のなかで,変わりゆく言葉(英語)の頼りなさやはかなさを嘆き,永遠に固定化されたラテン語やギリシア語への憧れを示している.一方,Chaucer を先輩詩人として引き合いに出しながら,詩人の言葉ははかなくとも,詩人の心は末代まで残るのだ,いや残って欲しいのだ,と痛切な願いを表現している.

Waller は,まさか1世紀ほど後にイングランドがフランスとの植民地争いを制して世界の覇権を握る糸口をつかみ,その1世紀後にはイギリス帝国が絶頂期を迎え,さらに1世紀後には英語が世界語として揺るぎない地位を築くなどとは想像もしていなかった.Waller はそこまでは予想できなかったわけだが,それだけにかえって現代の私たちがこの詩を読むと,言語(の地位)の変わりやすさ,頼りなさ,はかなさがひしひしと感じられてくる.

OF ENGLISH VERSE.

1 Poets may boast, as safely vain,

2 Their works shall with the world remain;

3 Both, bound together, live or die,

4 The verses and the prophecy.

5 But who can hope his lines should long

6 Last in a daily changing tongue?

7 While they are new, envy prevails;

8 And as that dies, our language fails.

9 When architects have done their part,

10 The matter may betray their art;

11 Time, if we use ill-chosen stone,

12 Soon brings a well-built palace down.

13 Poets that lasting marble seek,

14 Must carve in Latin, or in Greek;

15 We write in sand, our language grows,

16 And, like the tide, our work o'erflows.

17 Chaucer his sense can only boast;

18 The glory of his numbers lost!

19 Years have defaced his matchless strain;

20 And yet he did not sing in vain.

21 The beauties which adorned that age,

22 The shining subjects of his rage,

23 Hoping they should immortal prove,

24 Rewarded with success his love.

25 This was the generous poet's scope;

26 And all an English pen can hope,

27 To make the fair approve his flame,

28 That can so far extend their fame.

29 Verse, thus designed, has no ill fate,

30 If it arrive but at the date

31 Of fading beauty; if it prove

32 But as long-lived as present love.

・ Waller, Edmond. "Of English Verse". The Poems Of Edmund Waller. London: 1893. 197--98. Accessed through ProQuest on May 27, 2022.

2022-03-06 Sun

■ #4696. エリザベス1世による3単現 -th と -s が入り乱れた散文 [3sp][emode][monarch][speed_of_change][language_change]

初期近代英語期に3単現の語尾が -th から -s へと推移していった変化は,英語史でよく研究されている.本ブログでも「#2141. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の概要」 ([2015-03-08-1]),「#1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力」 ([2014-05-28-1]),「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]),「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]) などで取り上げてきた.

エリザベス1世 (1533--1603) の時代は -th から -s への推移のまっただなかにあり,女王自身も両語尾を併用しているが,明確な使い分けの基準があったわけではない.当時は,すでに話し言葉では -s が普通に用いられ,韻文(書き言葉)であれば -th が好まれるという段階にはあったが,では,その中間的なレジスターともいえる散文(書き言葉)ではどうだったのかというと,事情は複雑だ.Lass (163) に引用されている,エリザベス1世が Boethius を英訳した The Consolation of Philosophy より1節を覗いてみよう (Book 0, Prose IX) .

He that seekith riches by shunning penury, nothing carith for powre, he chosith rather to be meane & base, and withdrawes him from many naturall delytes. . . But that waye, he hath not ynogh, who leues to haue, & greues in woe, whom neerenes ouerthrowes & obscurenes hydes. He that only desyres to be able, he throwes away riches, despisith pleasures, nought esteems honour nor glory that powre wantith.

Lass (163) によると,同英訳書のサンプルで調査したところ,-th と -s の比はおよそ 1:2 だったという.すでに -s が上回っていたようだが,まだ推移のまっただなかだったと言ってよいだろう.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 56--186.

2022-02-12 Sat

■ #4674. 「初期近代英語期における語彙拡充の試み」 [slide][contrastive_linguistics][lexicology][borrowing][loan_word][emode][renaissance][inkhorn_term][latin][japanese_history][contrastive_language_history]

3週間前のことですが,1月22日(土)に,ひと・ことばフォーラムのシンポジウム「言語史と言語的コンプレックス ー 「対照言語史」の視点から」の一環として「初期近代英語期における語彙拡充の試み」をお話しする機会をいただきました.Zoom によるオンライン発表でしたが,その後のディスカッションを含め,たいへん勉強になる時間でした.主催者の方々をはじめ,シンポジウムの他の登壇者や出席者参加者の皆様に感謝申し上げます.ありがとうございました.

私の発表は,すでに様々な機会に公表してきたことの組み替えにすぎませんでしたが,今回はシンポジウムの題に含まれる「対照言語史」 (contrastive_linguistics) を意識して,とりわけ日本語史における語彙拡充の歴史との比較対照を意識しながら情報を整理しました.

当日利用したスライドを公開します.スライドからは本ブログ記事へのリンクも多く張られていますので,合わせてご参照ください.

1. ひと・ことばフォーラム言語史と言語的コンプレックス ー 「対照言語史」の視点から初期近代英語期における語彙拡充の試み

2. 初期近代英語期における語彙拡充の試み

3. 目次

4. 1. はじめに --- 16世紀イングランド社会の変化

5. 2. 統合失調症の英語 --- ラテン語への依存とラテン語からの独立

6. 英語が抱えていた3つの悩み

7. 3. 独立を目指して

8. 4. 依存症の深まり (1) --- 語源的綴字

9. 5. 依存症の深まり (2) --- 語彙拡充

10. オープン借用,むっつり借用,○製△語

11. 6.「インク壺語」の大量借用

12. 7. 大量借用への反応

13. 8. インク壺語,チンプン漢語,カタカナ語の対照言語史

14. 9. まとめ

15. 語彙拡充を巡る独・日・英の対照言語史

16. 参考文献

2021-12-30 Thu

■ #4630. Shakespeare の比較級・最上級の例をもっと [shakespeare][emode][comparison][superlative][adjective][adverb][suffix][periphrasis][suppletion]

昨日の記事「#4629. Shakespeare の2重比較級・最上級の例」 ([2021-12-29-1]) で,現代英語の規範文法では許容されない2重比較級・最上級が Shakespeare によって使われていた事例を見た.

それとは異なるタイプだが,現代では普通 more, most を前置する迂言形が用いられるところに Shakespeare では -er, -est を付す屈折形が用いられていた事例や,その逆の事例も観察される.さらには,現代では比較級や最上級になり得ない「絶対的」な意味をもつ形容詞・副詞が,Shakespeare ではその限りではなかったという例もある.現代と Shakespeare には400年の時差があることを考えれば,このような意味・統語論的な変化があったとしても驚くべきことではない.

Shakespeare と現代の語法で異なるものを Crystal and Crystal (88--90) より列挙しよう.

[ 現代英語では迂言法,Shakespeare では屈折法の例 ]

| Modern comparative | Shakespearian comparative | Example |

| ---------------------- | ----------------------------- | ----------- |

| more honest | honester | Cor IV.v.50 |

| more horrid | horrider | Cym IV.ii.331 |

| more loath | loather | 2H6 III.ii.355 |

| more often | oftener | MM IV.ii.48 |

| more quickly | quicklier | AW I.i.122 |

| more perfect | perfecter | Cor II.i.76 |

| more wayward | waywarder | AY IV.i.150 |

| Modern superlative | Shakespearian superlative | Example |

| ---------------------- | ----------------------------- | --------------- |

| most ancient | ancient'st | WT Iv.i10 |

| most certain | certain'st | TNK V.iv.21 |

| most civil | civilest | 2H6 IV.vii.56 |

| most condemned | contemned'st | KL II.ii.141 |

| most covert | covert'st | R3 III.v.33 |

| most daring | daring'st | H8 II.iv.215 |

| most deformed | deformed'st | Sonn 113.10 |

| most easily | easil'est | Cym IV.ii.206 |

| most exact | exactest | Tim II.ii.161 |

| most extreme | extremest | KL V.iii.134 |

| most faithful | faithfull'st | TN V.i.112 |

| most foul-mouthed | foul mouthed'st | 2H4 II.iv.70 |

| most honest | honestest | AW III.v.73 |

| most loathsome | loathsomest | TC II.i.28 |

| most lying | lyingest | 2H6 II.i.124 |

| most maidenly | maidenliest | KL I.ii.131 |

| most pained | pained'st | Per IV.vi.161 |

| most perfect | perfectest | Mac I.v.2 |

| most ragged | ragged'st | 2H4 I.i.151 |

| most rascally | rascalliest | 1H4 I.ii.80 |

| most sovereign | sovereignest | 1H4 I.iii.56 |

| most unhopeful | unhopefullest | MA II.i.349 |

| most welcome | welcomest | 1H6 II.ii.56 |

| most wholesome | wholesom'st | MM IV.ii.70 |

[ 現代英語では屈折法,Shakespeare では迂言法の例 ]

| Modern comparative | Shakespearian comparative | Example |

| ---------------------- | ----------------------------- | --------------- |

| greater | more great | 1H4 IV.i77 |

| longer | more long | Cor V.ii.63 |

| nearer | more near | AW I.iii.102 |

[ 現代英語では比較級・最上級を取らないが,Shakespeare では取っている例 ]

| Modern word | Shakespearian comparison | Example |

| ---------------------- | ----------------------------- | --------------- |

| chief | chiefest | 1H6 I.i.177 |

| due | duer | 2H4 III.ii.296 |

| just | justest | AC II.i.2 |

| less | lesser | R2 II.i.95 |

| like | liker | KJ II.i.126 |

| little | littlest [cf. smallest] | Ham III.ii.181 |

| rather | ratherest | LL IV.ii.18 |

| very | veriest | 1H4 II.ii.23 |

| worse | worser [cf. less bad] | Ham III.iv.158 |

現代と過去とで比較級・最上級の作り方が異なる例については「#3618. Johnson による比較級・最上級の作り方の規則」 ([2019-03-24-1]) も参照.

・ Crystal, David and Ben Crystal. Shakespeare's Words: A Glossary & Language Companion. London: Penguin, 2002.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2021-12-29 Wed

■ #4629. Shakespeare の2重比較級・最上級の例 [shakespeare][emode][comparison][double_comparative][superlative][adjective][adverb]

本ブログの以下の記事で書いてきたが,Shakespeare が most unkindest cut of all (JC III.ii.184) のような,現代の規範文法では破格とされる2重最上級(および2重比較級 (double_comparative))を用いたことはよく知られている.実際には,Shakespeare がこのような表現をとりわけ頻用したわけではないのだが,使っていることは確かである.

・ 「#195. Shakespeare に関する Web resources」 ([2009-11-08-1])

・ 「#3615. 初期近代英語の2重比較級・最上級は大言壮語にすぎない?」 ([2019-03-21-1])

・ 「#3619. Lowth がダメ出しした2重比較級と過剰最上級」 ([2019-03-25-1])

では,Shakespeare は他のどのような2重比較級・最上級を使ったのか.Crystal and Crystal (88) が代表的な例を列挙してくれているので,それを再現したい.

[ Double comparatives ]

・ more better (MND III.i.18)

・ more bigger-looked (TNK I.i.215)

・ more braver (Tem I.ii.440)

・ more corrupter (KL II.ii.100)

・ more fairer (E3 II.i.25)

・ more headier (KL II.iv.105)

・ more hotter (AW IV.v.38)

・ more kinder (Tim IV.i.36)

・ more mightier (MM V.i.235)

・ more nearer (Ham II.i.11)

・ more nimbler (E3 II.ii.178)

・ more proudlier (Cor IV.vii.8)

・ more rawer (Ham V.ii.122)

・ more richer (Ham III.ii.313)

・ more safer (Oth I.iii.223)

・ more softer (TC II.ii.11)

・ more sounder (AY III.ii.58)

・ more wider (Oth I.iii.107)

・ more worse (KL II.ii.146)

・ more worthier (AY III.iii.54)

・ less happier (R2 II.i.49)

[ Double superlatives ]

・ most boldest (JC III.i.121)

・ most bravest (Cym IV.ii.319)

・ most coldest (Cym II.iii.2)

・ most despiteful'st (TC IV.i.33)

・ most heaviest (TG IV.ii.136)

・ most poorest (KL II.iii.7)

・ most stillest (2H4 III.ii.184)

・ most unkindest (JC III.ii.184)

・ most worst (WT III.ii.177)

このなかで more nearer の事例はおもしろい.語源を振り返れば,まさに3重比較級 (triple comparative) である.「#209. near の正体」 ([2009-11-22-1]), および「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」より「near はもともと比較級だった!」をどうそ.

・ Crystal, David and Ben Crystal. Shakespeare's Words: A Glossary & Language Companion. London: Penguin, 2002.

2021-12-28 Tue

■ #4628. 16世紀後半から17世紀にかけての正音学者たち --- 英語史上初の本格的綴字改革者たち [orthography][orthoepy][spelling][standardisation][emode][mulcaster][hart][bullokar][spelling_reform][link]

英語史における最初の綴字改革 (spelling_reform) はいつだったか,という問いには答えにくい.「改革」と呼ぶからには意図的な営為でなければならないが,その点でいえば例えば「#2712. 初期中英語の個性的な綴り手たち」 ([2016-09-29-1]) でみたように,初期中英語期の Ormulum の綴字も綴字改革の産物ということになるだろう.

しかし,綴字改革とは,普通の理解によれば,個人による運動というよりは集団的な社会運動を指すのではないか.この理解に従えば,綴字改革の最初の契機は,16世紀後半から17世紀にかけての一連の正音学 (orthoepy) の論者たちの活動にあったといってよい.彼らこそが,英語史上初の本格的綴字改革者たちだったのだ.これについて Carney (467) が次のように正当に評価を加えている.

The first concerted movement for the reform of English spelling gathered pace in the second half of the sixteenth century and continued into the seventeenth as part of a great debate about how to cope with the flood of technical and scholarly terms coming into the language as loans from Latin, Greek and French. It was a succession of educationalists and early phoneticians, including William Mulcaster, John Hart, William Bullokar and Alexander Gil, that helped to bring about the consensus that took the form of our traditional orthography. They are generally known as 'orthoepists'; their work has been reviewed and interpreted by Dobson (1968). Standardization was only indirectly the work of printers.

この点について Carney は,基本的に Brengelman の1980年の重要な論文に依拠しているといってよい.Brengelman の論文については,以下の記事でも触れてきたので,合わせて読んでいただきたい.

・ 「#1383. ラテン単語を英語化する形態規則」 ([2013-02-08-1])

・ 「#1384. 綴字の標準化に貢献したのは17世紀の理論言語学者と教師」 ([2013-02-09-1])

・ 「#1385. Caxton が綴字標準化に貢献しなかったと考えられる根拠」 ([2013-02-10-1])

・ 「#1386. 近代英語以降に確立してきた標準綴字体系の特徴」 ([2013-02-11-1])

・ 「#1387. 語源的綴字の採用は17世紀」 ([2013-02-12-1])

・ 「#2377. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (1)」 ([2015-10-30-1])

・ 「#2378. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (2)」 ([2015-10-31-1])

・ 「#3564. 17世紀正音学者による綴字標準化への貢献」 ([2019-01-29-1])

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

・ Dobson, E. J. English Pronunciation 1500--1700. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Oxford: OUP, 1968.

・ Brengelman, F. H. "Orthoepists, Printers, and the Rationalization of English Spelling." JEGP 79 (1980): 332--54.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow