2020-08-03 Mon

■ #4116. It's very kind of you to come. の of の用法は? [preposition][syntax][infinitive][construction][adjective][semantics][apposition]

標題のように,いくつかの形容詞は「of + 人」という前置詞句を伴う.

・ It's very kind of you to come. (わざわざ来てもらってすみません.)

・ It was foolish of you to spend so much. (そんなにお金を使って馬鹿ねえ.)

・ It was wrong of him to tell lies. (嘘をついて,彼もよくなかったね.)

・ It is wise of you to stay away from him. (君が彼とつき合わないのは賢明だ.)

・ It was silly of me to forget my passport. (パスポートを忘れるとはうかつだった.)

典型的に It is ADJ of PERSON to do . . . . という構文をなすわけだが,PERSON is ADJ to do . . . . という構文もとることができる点で興味深い.たとえば標題は You're very kind to come. とも言い換えることができる.この点で,より一般的な「for + 人」を伴う It is important for him to get the job. (彼が職を得ることは重要なことだ.)の構文とは異なっている.後者は *He is important to get the job. とはパラフレーズできない.

標題の構文を許容する形容詞 --- すなわち important タイプではなく kind タイプの形容詞 --- を挙げてみると,careful, careless, crazy, greedy, kind, mad, nice, silly, unwise, wise, wrong 等がある (Quirk et al. §§16.76, 16.82).いずれも意味的には人の行動を評価する形容詞である.別の角度からみると,標題の文では kind (親切な)なのは「来てくれたこと」でもあり,同時に「あなた」でもあるという関係が成り立つ.

一方,上述の important (重要な)を用いた例文では,重要なのは「職を得ること」であり,「彼」が重要人物であるわけではないから,やはり両タイプの意味論的性質が異なることが分かるだろう.つまり,important タイプの for を用いた構文とは異なり,kind タイプの of を用いた構文では,kind of you の部分が you are kind という意味関係を包含しているのである.

とすると,この前置詞 of の用法は何と呼ぶべきか.一種の同格 (apposition) の用法とみることもできるが,どこか納まりが悪い(cf. 「#2461. an angel of a girl (1)」 ([2016-01-22-1]),「#2462. an angel of a girl (2)」 ([2016-01-23-1])).「人物・行動評価の of」などと呼んでもよいかもしれない.いずれにせよ,歴史的に探ってみる必要がある.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2020-08-02 Sun

■ #4115. なぜ「the 比較級,the 比較級」で「?すればするほど?」の意味になるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版 [hellog-radio][sobokunagimon][hel_education][article][comparison][adjective][instrumental]

hellog ラジオ版の第12回は,1つの公式として学習することの多い標題の構文について.

・ The longer you work, the more you will earn. (長く働けば働くほど,多くのお金を稼げます.)

・ The older we grow, the weaker our memory becomes. (年をとればとるほど,記憶力は衰えます.)

・ The sooner, the better. (早ければ早いほどよい.)

この構文では,比較級を用いた節が2つ並列されるので「?すればするほど?」という意味になることは何となく分かる気がするのですが,なぜ定冠詞 the が出てくるのかしょうか.この the の役割はいったい何なのでしょうか.今回は,その謎解きをしていきます.

実は驚くほど歴史の古い構文なのですね.しかも,the が副詞 (adverb) として機能しているとは! 考え方としては,when . . . then, if . . . then, although . . . yet, as . . . so のような相関構文と同列に扱えばよいということになります.

この問題について詳しく理解したい方は,##812,811の記事セットをご覧ください.

2020-05-05 Tue

■ #4026. なぜ Japanese や Chinese などは単複同形なのですか? (3) [plural][number][adjective][etymology][suffix][metanalysis][sobokunagimon]

標記の素朴な疑問について2日間の記事 ([2020-05-03-1], [2020-05-04-1]) で論じてきました.今日もその続きです.

Japanese や Chinese は本来形容詞であるから名詞として用いる場合でも複数形の -s がつかないのだという説に対して,いや初期近代英語期には Japaneses や Chineses のような通常の -s を示す複数形が普通に使われていたのだから,そのような形容詞起源に帰する説は受け入れられない,というところまで議論をみてきました.ここで問うべきは,なぜ Japaneses や Chineses という複数形が現代までに廃用になってしまったのかです.

考えられる答えの1つは,これまでの論旨と矛盾するようではありますが,やはり起源的に形容詞であるという意識が根底にあり続け,最終的にはそれが効いた,という見方です.例えば Those students over there are Japanese. と聞いたとき,この Japanese は複数名詞として「日本人たち」とも解釈できますが,形容詞として「日本(人)の」とも解釈できます.つまり両義的です.起源的にも形容詞であり,使用頻度としても形容詞として用いられることが多いとすれば,たとえ話し手が名詞のつもりでこの文を発したとしても,聞き手は形容詞として理解するかもしれません.歴とした名詞として Japaneses が聞かれた時期もあったとはいえ,長い時間の末に,やはり本来の Japanese の形容詞性が勝利した,とみなすことは不可能ではありません.

もう1つの観点は,やはり上の議論と関わってきますが,the English, the French, the Scottish, the Welsh, など,接尾辞 -ish (やその異形)をもつ形容詞に由来する「?人」が -(e)s を取らず,集合的に用いられることとの平行性があるのではないかとも疑われます(cf. 「#165. 民族形容詞と i-mutation」 ([2009-10-09-1])).

さらにもう1つの観点を示すならば,発音に関する事情もあるかもしれません.Japaneses や Chineses では語末が歯摩擦音続きの /-zɪz/ となり,発音が不可能とはいわずとも困難になります.これを避けるために複数形語尾の -s を切り落としたという可能性があります.関連して所有格の -s の事情を参照してみますと,/s/ や /z/ で終わる固有名詞の所有格は Socrates' death, Moses' prophecy, Columbus's discovery などと綴りますが,発音としては所有格に相当する部分の /-ɪz/ は実現されないのが普通です.歯摩擦音が続いて発音しにくくなるためと考えられます.Japanese, Chineses にも同じような発音上の要因が作用したのかもしれません.

音韻的な要因をもう1つ加えるならば,Japanese や Chinese の語末音 /z/ 自体が複数形の語尾を体現するものとして勘違いされたケースが,歴史的に観察されたという点も指摘しておきましょう.OED では,勘違いの結果としての単数形としての Chinee や Portugee の事例が報告されています.もちろんこのような勘違い(専門的には「異分析」 (metanalysis) といいます)が一般化したという歴史的事実はありませんが,少なくとも Japaneses のような歯摩擦音の連続が不自然であるという上記の説に間接的に関わっていく可能性を匂わす事例ではあります.

以上,仮説レベルの議論であり解決には至っていませんが,英語史・英語学の観点から標題の素朴な疑問に迫ってみました.英語史のポテンシャルと魅力に気づいてもらえれば幸いです.

2020-05-04 Mon

■ #4025. なぜ Japanese や Chinese などは単複同形なのですか? (2) [plural][number][adjective][etymology][suffix][sobokunagimon]

昨日の記事 ([2020-05-03-1]) に引き続き,英語史の授業で寄せられた標題の素朴な疑問について.

昨日の議論では,-ese 語は起源的に形容詞であり,だからこそ名詞という品詞に特有の「複数形」などはとらないのだという説明を見ました.しかし,英語には形容詞起源の名詞はごまんとあり,それらは通例しっかり複数形の -s をとっているのです (ex. Americans, blacks, females, gays, natives) .この説明だけでは満足がいきません.

さらにこの説明にとって都合の悪いことに,初期近代英語には,なんと Japaneses という名詞複数形が用いられていたのです.OED の Japanese, adj. and n. より,該当する語義の項目と例文を挙げてみましょう.

B. n

1. A native of Japan.

Formerly as true noun with plural in -es; now only as an adjective used absolute and unchanged for plural: a Japanese, two Japanese, the Japanese.

. . . .

1655 E. Terry Voy. E.-India 129 I have taken speciall notice of divers Chinesaas, and Japanesaas there.

1693 T. P. Blount Nat. Hist. 105 The Iapponeses prepare [tea]..quite otherwise than is done in Europe.

. . . .

スペリングこそまだ現代風ではありませんが Japanesaas や Iapponeses という語形がみえます.つまり,名詞としての複数形 Americans, blacks, females, gays, natives が当たり前に用いられるのと同じように,Japaneses も当たり前のように用いられていたのです.上の1655年の例文には Chinesaas も用いられており,17世紀にはこれが一般的だったのです.実際,ピューリタン詩人ミルトンも名作『失楽園』にて "1667 J. Milton Paradise Lost iii. 438 Sericana, where Chineses drive With Sails and Wind thir canie Waggons light." のように Chineses を用いています.問題は,なぜ名詞複数形の Japaneses, Chineses が後に廃用となり,単複同形となったのかです.

引き続き,明日の記事で考えていきたいと思います.

2020-05-03 Sun

■ #4024. なぜ Japanese や Chinese などは単複同形なのですか? (1) [plural][number][adjective][etymology][suffix][latin][french][sobokunagimon]

英語史の授業で寄せられた素朴な疑問です.-ese の接尾辞 (suffix) をもつ「?人」を意味する国民名は,複数形でも -s を付けず,単複同形となります.There are one/three Japanese in the class. のように使います.なぜ複数形なのに -s を付けないのでしょうか.これは,なかなか難しいですが良問だと思います.

現代英語には sheep, hundred, fish など,少数ながらも単複同形の名詞があります.その多くは「#12. How many carp!」 ([2009-05-11-1]) でみたように古英語の屈折事情にさかのぼり,その古い慣習が現代英語まで化石的に残ったものとして歴史的には容易に説明できます.しかし,-ese は事情が異なります.この接尾辞はフランス語からの借用であり,早くとも中英語期,主として近代英語期以降に現われてくる新顔です.古英語の文法にさかのぼって単複同形を説明づけることはできないのです.

-ese の語源から考えていきましょう.-ese という接尾辞は,まずもって固有名からその形容詞を作る接尾辞です.ラテン語の形容詞を作る接尾辞 -ensis に由来し,その古フランス語における反映形 -eis が中英語に -ese として取り込まれました.つまり,起源的に Japanese, Chinese は第一義的に形容詞として「日本の」「中国の」を意味したのです.

一方,形容詞が名詞として用いられるようになるのは英語に限らず言語の日常茶飯です.Japanese が単独で「日本の言語」 "the Japanese language" や「日本の人(々)」 "(the) Japanese person/people" ほどを意味する名詞となるのも自然の成り行きでした.しかし,現在に至るまで,原点は名詞ではなく形容詞であるという意識が強いのがポイントです.複数名詞「日本人たち」として用いられるときですら原点としての形容詞の意識が強く残っており,形容詞には(単数形と区別される)複数形がないという事実も相俟って,Japanese という形態のままなのだと考えられます.要するに,Japanese が起源的には形容詞だから,名詞だけにみられる複数形の -s が付かないのだ,という説明です.

しかし,この説明には少々問題があります.起源的には形容詞でありながらも後に名詞化した単語は,英語にごまんとあります.そして,その多くは名詞化した以上,名詞としてのルールに従って複数形では -s をとるのが通例です.例えば American, black, female, gay, native は起源的には形容詞ですが,名詞としても頻用されており,その場合,複数形に -s をとります.だとすれば Japanese もこれらと同じ立ち位置にあるはずですが,なぜか -s を取らないのです.起源的な説明だけでは Japanese の単複同形の問題は満足に解決できません.

この問題については,明日の記事で続けて論じていきます.

2020-04-12 Sun

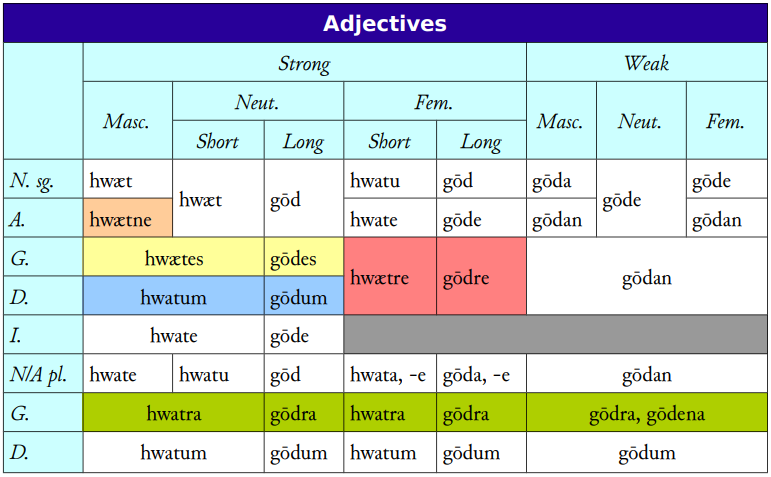

■ #4003. ゲルマン語派の形容詞の強変化と弱変化 (2) [adjective][inflection][oe][germanic][indo-european][comparative_linguistics][grammaticalisation][paradigm]

現代英語にはみられないが,印欧語族の多くの言語では形容詞 (adjective) に屈折 (inflection) がみられる.さらにゲルマン語派の諸言語においては,形容詞屈折に関して,統語意味論的な観点から強変化 (strong declension) と弱変化 (weak declension) の2種の区別がみられる(各々の条件については「#687. ゲルマン語派の形容詞の強変化と弱変化」 ([2011-03-15-1]) を参照).このような強弱の区別は,ゲルマン語派の著しい特徴の1つとされており,比較言語学的に興味深い(cf. 「#182. ゲルマン語派の特徴」 ([2009-10-26-1])).

英語では,古英語期にはこの区別が明確にみられたが,中英語期にかけて屈折語尾の水平化が進行すると,同区別はその後期にかけて失われていった(cf. 「#688. 中英語の形容詞屈折体系の水平化」 ([2011-03-16-1]),「#2436. 形容詞複数屈折の -e が後期中英語まで残った理由」 ([2015-12-28-1]) ).現代英語は,形容詞の強弱屈折の区別はおろか,屈折そのものを失っており,その分だけゲルマン語的でも印欧語的でもなくなっているといえる.

古英語における形容詞の強変化と弱変化の屈折を,「#250. 古英語の屈折表のアンチョコ」 ([2010-01-02-1]) より抜き出しておこう.

では,なぜ古英語やその他のゲルマン諸語には形容詞の屈折に強弱の区別があるのだろうか.これは難しい問題だが,屈折形の違いに注目することにより,ある種の洞察を得ることができる.強変化屈折パターンを眺めてみると,名詞強変化屈折と指示代名詞屈折の両パターンが混在していることに気付く.これは,形容詞がもともと名詞の仲間として(強変化)名詞的な屈折を示していたところに,指示代名詞の屈折パターンが部分的に侵入してきたものと考えられる(もう少し詳しくは「#2560. 古英語の形容詞強変化屈折は名詞と代名詞の混合パラダイム」 ([2016-04-30-1]) を参照).

一方,弱変化の屈折パターンは,特徴的な n を含む点で弱変化名詞の屈折パターンにそっくりである.やはり形容詞と名詞は密接な関係にあったのだ.弱変化名詞の屈折に典型的にみられる n の起源は印欧祖語の *-en-/-on- にあるとされ,これはラテン語やギリシア語の渾名にしばしば現われる (ex. Cato(nis) "smart/shrewd (one)", Strabōn "squint-eyed (one)") .このような固有名に用いられることから,どうやら弱変化屈折は個別化の機能を果たしたようである.とすると,古英語の形容詞弱変化屈折を伴う se blinda mann "the blind man" という句は,もともと "the blind one, a man" ほどの同格的な句だったと考えられる.それがやがて文法化 (grammaticalisation) し,屈折という文法範疇に組み込まれていくことになったのだろう.

以上,Marsh (13--14) を参照して,なぜゲルマン語派の形容詞に強弱2種類の屈折があるのかに関する1つの説を紹介した.

・ Marsh, Jeannette K. "Periods: Pre-Old English." Chapter 1 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1--18.

2020-04-10 Fri

■ #4001. want の英語史 --- 語末の t [old_norse][loan_word][borrowing][inflection][adjective][gender][impersonal_verb]

連日 want という語を英語史的に掘り下げる記事を書いている(過去記事は [2020-04-08-1] と [2020-04-09-1]).今回は語末の t について考えてみたい.

英語史の教科書などでは,want のような日常的な単語が古ノルド語からの借用語であるというのは驚くべきこととしてしばしば言及される.また,語末の t が古ノルド語の形容詞の中性語尾であることも指摘される(cf. 「#1253. 古ノルド語の影響があり得る言語項目」 ([2012-10-01-1])).しかし,この t を巡っては意外と込み入った事情がある.

「#3999. want の英語史 --- 語源と意味変化」 ([2020-04-08-1]) で触れたように,英語の名詞 want と動詞 want とは語幹こそ確かに同一だが,入ってきた経路は異なる.名詞 want は,古ノルド語の形容詞 vanr (欠いた)が中性に屈折した vant という形態が名詞的に用いられるようになったものである.一方,動詞 want は古ノルド語の動詞 vanta (欠く,欠いている)に由来する.つまり,語根に対応する wan の部分こそ共通とみてよいが,語末の t に関しては,名詞の場合には形容詞の中性語尾に由来するといわなければならず,動詞の場合には(未調査だが)また別に由来があるということになる.したがって,want の t は形容詞の中性語尾であるという教科書的な指摘は,名詞としての want にのみ当てはまるということだ.

動詞の t については別途調べることにし,ここでは教科書で言及される,名詞の t が形容詞の中性語尾に由来する件について掘り下げたい.すでに述べたように,古ノルド語 vanr は形容詞で「?を欠いている」 (lacking) を意味した(古英語の形容詞 wana と同根語).古ノルド語では,これが be 動詞と組み合わさって非人称構文を構成した.OED の want, adj. and n.2 の語源欄に,次のように記述がある.

Old Icelandic vant (neuter singular adjective) is used predicatively in expressions of the type vera vant to be lacking, typically with the person lacking something in the dative and the thing that is lacking in the genitive and with vant thus behaving similarly to a noun (compare e.g. var þeim vettugis vant they were lacking nothing, they had want of nothing, or var vant kýr a cow was missing, there was want of a cow).

形容詞としての vanr (中性形 vant)は,つまり "was VANT to them of nothing" (彼らにとって何も欠けていなかった)のように主語のない非人称構文において用いられていたということである.この用法がよほど高頻度だったのだろうか,古ノルド語話者と接触した英語話者は,中性に屈折した vant それ自体があたかも語幹であるかのように解釈し,語頭子音を英語化しつつ t 語尾込みの want を「欠乏,不足」を意味する名詞として受容したと考えられる.

語の借用においては,受け入れ側の話者が相手言語の文法に精通していないかぎり,屈折語尾を含めて語幹と勘違いして,「原形」として取り込んでしまう例はいくらでもあったろう.実際,形容詞の中性語尾に由来する t をもつ他の例として,scant (乏しい), thwart (横切って), wight (勇敢な),†quart (健康な)などが挙げられる.

関連して,フランス語の不定詞語尾 -er を含んだまま英語に取り込まれた cesser, detainer, dinner, merger, misnomer, remainder, surrender なども,ある意味で類例といえるだろう.これにつていは「#220. supper は不定詞」 ([2009-12-03-1]),「#221. dinner も不定詞」 ([2009-12-04-1]) を参照.

2020-02-09 Sun

■ #3940. 形容詞を作る接尾辞 -al と -ar [suffix][adjective][morphology][dissimilation][r][l]

英語の形容詞を作る典型的な接尾辞 (suffix) に -al がある.abdominal, chemical, dental, editorial, ethical, fictional, legal, magical, medical, mortal, musical, natural, political, postal, regal, seasonal, sensational, societal, tropical, verbal など非常に数多く挙げることができる.これはラテン語の形容詞を作る接尾辞 -ālis (pertaining to) が中英語期にフランス語経由で入ってきたもので,生産的である.

よく似た接尾辞に -ar というものもある.これも決して少なくない.angular, cellular, circular, insular, jocular, linear, lunar, modular, molecular, muscular, nuclear, particular, polar, popular, regular, singular, spectacular, stellar, tabular, vascular など多数の例が挙がる.この接尾辞の起源はやはりラテン語にあり,形容詞を作る -āris (pertaining to) にさかのぼる.両接尾辞の違いは l と r だけだが,互いに関係しているのだろうか.

答えは Yes である.これは典型的な l と r の異化 (dissimilation) の例となっている.ラテン語におけるデフォルトの接尾辞は -ālis の方だが,基体に l が含まれるときには l 音の重複を嫌って,接尾辞の l が r へと異化した.特に基体が「子音 + -le」で終わる場合には,音便として子音の後に u が挿入され (anaptyxis) ,派生形容詞は -ular という語尾を示すことになる.

l と r の異化については,「#72. /r/ と /l/ は間違えて当然!?」 ([2009-07-09-1]),「#1597. star と stella」 ([2013-09-10-1]),「#1614. 英語 title に対してフランス語 titre であるのはなぜか?」 ([2013-09-27-1]),「#3016. colonel の綴字と発音」 ([2017-07-30-1]),「#3684. l と r はやっぱり近い音」 ([2019-05-29-1]),「#3904. coriander の第2子音は l ではなく r」 ([2020-01-04-1]) も参照.

2020-01-19 Sun

■ #3919. Chibanian (チバニアン,千葉時代)の接尾辞 -ian (2) [suffix][word_formation][adjective][participle][indo-european][etymology]

昨日の記事 ([2020-01-18-1]) に引き続き,話題の Chibanian の接尾辞 -ian について.この英語の接尾辞は,ラテン語で形容詞を作る接尾辞 -(i)ānus にさかのぼることを説明したが,さらに印欧祖語までさかのぼると *-no- という接尾辞に行き着く.語幹母音に *-ā- が含まれるものに後続すると,*-āno- となり,これ全体が新たな接尾辞として切り出されたということだ.ここから派生した -ian, -an, -ean が各々英語に取り込まれ,生産的な語形成を展開してきたことは,昨日挙げた多くの例で示される通りである.

さて,印欧祖語の *-no- は,ゲルマン語派のルートを通じて,英語の意外な部分に受け継がれてきた.強変化動詞の過去分詞形に現われる -en と素材を表わす名詞に付されて形容詞を作る -en である.前者は broken, driven, shown, taken, written などの -en を指し,後者は brazen, earthen, golden, wheaten, wooden, woolen などの -en を指す (cf. 後者について「#1471. golden を生み出した音韻・形態変化」 ([2013-05-07-1]) も参照).いずれも形容詞以外から形容詞を作るという点で共通の機能を果たしている.

つまり,Chibanian の -ian と golden の -en は,現代英語に至るまでの経路は各々まったく異なるものの,さかのぼってみれば同一ということになる.

2020-01-18 Sat

■ #3918. Chibanian (チバニアン,千葉時代)の接尾辞 -ian (1) [suffix][word_formation][toponymy][adjective][anthropology][homo_sapiens][productivity]

昨日,ついに Chibanian (チバニアン,千葉時代)が初の日本の地名に基づく地質時代の名前として,国際地質科学連合により決定された.本ブログでこの話題を「#2979. Chibanian はラテン語?」 ([2017-06-23-1]) で取り上げてから2年半が経過しているが,ようやくの決定である.当の千葉県では新聞の号外が配られたというから,ずいぶん盛り上がっているようだ.

Chibanian は,約77万4千年?12万9千年前の地質時代を指す名称である.この時代は,ホモ・サピエンス (homo_sapiens) が登場した頃であり,さらには初期の言語能力が芽生えていた可能性もある点で興味が尽きない.先の記事では,Chibanian なる新語は,よく考えてみるとラテン語でも英語でも日本語でもない不思議な語だと述べた.今回は名称決定を記念して,この新語に引っかけて語源的な話題をもう少し提供してみたい.接尾辞 (suffix) の -ian についてである.

この接尾辞は「?の,?に属する」を意味する形容詞を作るラテン語の接尾辞 -iānus にさかのぼる.さらに分解すれば,-i- は連結母音であり,実質的な機能をもっているのは -ānus の部分である.ラテン語で語幹に i をもつ固有名詞から,その形容詞を作るのに -ānus が付されたものだが,後に -iānus が全体として接尾辞と感じられるようになったものだろう (ex. Italia -- Italiānus, Fabius -- Fabiānus, Vergilius -- Vergiliānus) .

英語はこのラテン語の語形成にならい,-ian 接尾辞により固有名詞の形容詞(およびその形容詞に対応する名詞)を次々と作り出してきた.例を挙げれば,Addisonian, Arminian, Arnoldian, Bodleian, Cameronian, Gladstonian, Hoadleian, Hugonian, Johnsonian, Morrisonian, Ruskinian, Salisburyian, Shavian, Sheldonian, Taylorian, Tennysonian, Wardian, Wellsian, Wordsworthian; Aberdonian, Bathonian, Bostonian, Bristolian, Cantabrigian, Cornubian, Devonian, Galwegian, Glasgowegian, Johnian, Oxonian, Parisian, Salopian, Sierra Leonian などである.固有名詞ベースのものばかりでなく,小文字書きする antediluvian, barbarian, historian, equestrian, patrician, phonetician, statistician など,例は多い.

実は,ラテン語の接尾辞 -ānus にさかのぼる点では -ian も -an も -ean も同根である.したがって,African, American, European, Mediterranean なども,語形成的には兄弟関係にあるといえる (cf. 「#366. Caribbean の綴字と発音」 ([2010-04-28-1])) .ただし,現代の新語形成においては,固有名詞につく場合,-ian の付くのが一般的のようである.今回の Chibanian も,この接尾辞の近年の生産性 (productivity) を示す証拠といえようか.

2019-11-05 Tue

■ #3844. 比較級の4用法 [comparison][adjective][adverb][semantics]

昨日の記事「#3843. なぜ形容詞・副詞の「原級」が "positive degree" と呼ばれるのか?」 ([2019-11-04-1]) や「#3835. 形容詞などの「比較」や「級」という範疇について」 ([2019-10-27-1]) で,形容詞・副詞の比較 (comparison) について調べている.以下は『新英語学辞典』の comparison の項からの要約にすぎないが,Kruisinga (Handbook, Vol. 4, §§1734--41) による比較級の4用法を紹介しよう.

(i) 対照比較級 (comparative of contrast)

a younger son における比較級 younger は,an elder son の elder を念頭に,それと対照的に用いられている.How slow you are! Try and be a little quicker. のように,テキスト中に明示的に対照性が示される場合もある.一方,unique, real, right, wrong などの形容詞は本来的に対照的な意味を有しており,それゆえに対照比較級をとることはない.

(ii) 優勢比較級 (comparative of superiority)

2者について同じ特徴をもつが,一方が他方よりも高い程度を表わす場合に用いられる.He worked harder than most men. のような一般的な比較文がこれである.対照比較級の特別な場合と考えることもできる.

(iii) 比例比較級 (comparative of proportion)

平行する2つの節で用いられることが多く,同じ比率で増加・減少する性質を表現する.The more he contemplated the thing the greater became his astonishment. や You grow queerer as you grow older. や Life seemed the better worth living because she had glimpsed death. などの例があがる.

(iv) 漸層比較級 (comparative of graduation)

ある性質が漸次増加・減少することを表わすのに and を用いて比較級を重ねるもの.The road got worse and worse until there was none at all. など.worse and worse とする代わりに even worse などと副詞を添える場合もあるし,worse 1つを単独で用いる場合もある.

比較級を意味論的に分類してみると興味深い.これらの歴史的発達も調べてみるとおもしろそうだ.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄 監修 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1987年.

2019-11-04 Mon

■ #3843. なぜ形容詞・副詞の「原級」が "positive degree" と呼ばれるのか? [comparison][terminology][adjective][adverb][sobokunagimon]

「#3835. 形容詞などの「比較」や「級」という範疇について」 ([2019-10-27-1]) で,形容詞・副詞にみられる比較 (comparison) という範疇 (category) について考えた.一般に英語の比較においては,3つの級 (grade) が区別される.原級 (positive degree),比較級 (comparative degree),最上級 (superlative degree) である.ここで英語の用語に関して comparative と superlative はよく分かるのだが,positive というのがイマイチ理解しにくい.何がどう positive だというのだろうか.

OED で positive, adj. and n. を引いてみると,この文法用語としての意味は,語義12に挙げられている.

12. Grammar. Designating the primary degree of an adjective or adverb, which expresses simple quality without qualification; not comparative or superlative. . . .

この positive は negative の反対というわけではない.それは特に何も修正や小細工が施されていない形容詞・副詞そのもののあり方をいう.換言すれば absolute (絶対的), intrinsic (本質的), independent (独立的)といってもよいほどの意味だろう.比較的・相対的な級である comparative や superlative に対して,比較しない絶対的な級だから positive というわけだ.ある意味で,否定的に定義されている用語・概念といえる.

文法用語としての初例は1434年頃となっている.用語の理解に資する歴史的な例文をいくつか引こう.

・ c1434 J. Drury Eng. Writings in Speculum (1934) 9 79 Þe positif degre..be-tokenyth qualite or quantite with outyn makyng more or lesse & settyth þe grownd of alle oþere degreis of Comparison.

・ 1704 J. Harris Lexicon Technicum I Positive Degree of Comparison in Grammar, is that which signifies the Thing simply and absolutely, without comparing it with others; it belongs only to Adjectives.

・ 1930 Frederick (Maryland) Post 15 Jan. 4/2 The Positive degree is used when no comparison is made with any other noun or pronoun, except as to their class; it is expressed by the simple unchanged form of the adjective; it expresses a certain idea to an ordinary extent.

上記を考えると,日本語の「原級」という訳語も決して悪くない.

2019-10-27 Sun

■ #3835. 形容詞などの「比較」や「級」という範疇について [comparison][adjective][adverb][category][terminology][fetishism]

英語の典型的な形容詞・副詞には,原級・比較級・最上級の区別がある.日本語の「比較」や「級」という用語には,英語の "comparison", "degree", "gradation" などが対応するが,そもそもこれは言語学的にどのような範疇 (category) なのか.Bussmann の用語辞典より,まず "degree" の項目をみてみよう.

degree (also comparison, gradation)

All constructions which express a comparison properly fall under the category of degree; it generally refers to a morphological category of adjectives and adverbs that indicates a comparative degree or comparison to some quantity. There are three levels of degree: (a) positive, or basic level of degree: The hamburgers tasted good; 'b) comparative, which marks an inequality of two states of affairs relative to a certain characteristic: The steaks were better than the hamburgers; (c) superlative, which marks the highest degree of some quantity: The potato salad was the best of all; (d) cf. elative (absolute superlative), which marks a very high degree of some property without comparison to some other state of affairs: The performance was most impressive . . . .

Degree is not grammaticalized in all languages through the use of systematic morphological changes; where such formal means are not present, lexical paraphrases are used to mark gradation. In modern Indo-European languages, degree is expressed either (a) synthetically by means of suffixation (new : newer : (the) newest); (b) analytically by means of particles (anxious : more/most anxious); or (c) through suppletion . . . , i.e. the use of different word stems: good : better : (the) best.

同様に "gradation" という項目も覗いてみよう.

gradation

Semantic category which indicates various degrees (i.e. gradation) of a property or state of affairs. The most important means of gradation are the comparative and superlative degrees of adjectives and some (deadjectival) adverbs. In addition, varying degrees of some property can also be expressed lexically, e.g. especially/really quick, quick as lightning, quicker and quicker.

上の説明にあるように "degree" や "gradation" が「意味」範疇であることはわかる.英語のみならず,日本語でも「より良い」「ずっと良い」「最も良い」「最良」などの表現が様々に用意されており,「比較」や「級」に相当する機能を果たしているからだ.しかし,通言語的にはそれが常に形態・統語的な「文法」範疇でもあるということにはならない.いってしまえば,たまたま印欧諸語では文法化し(=文法に埋め込まれ)ているので文法範疇として認められているが,日本語では特に文法範疇として設定されていないという,ただそれだけのことである.

個々の文法範疇は,通言語的に比較的よくみられるものもあれば,そうでないものもある.文法範疇とは,ある意味で個別言語におけるフェチというべきものである.この見方については「#2853. 言語における性と人間の分類フェチ」 ([2017-02-17-1]) をはじめ fetishism の各記事を参照されたい.

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

2019-08-30 Fri

■ #3777. set, put, cut のほかにもあった無変化活用の動詞 [verb][conjugation][inflection][-ate][analogy][conversion][adjective][participle][conversion]

set, put, cut の類いの無変化活用の動詞について「#1854. 無変化活用の動詞 set -- set -- set, etc.」 ([2014-05-25-1]),「#1858. 無変化活用の動詞 set -- set -- set, etc. (2)」 ([2014-05-29-1]) の記事で取り上げてきた.そこでは,これらの動詞の振る舞いが,英語の音韻形態論の歴史に照らせば,ある程度説得力のある説明が与えられることをみた.

語幹末に t や d が現われる単音節語である,というのがこれらの動詞の共通項だが,歴史的には,この条件を満たしている限りにおいて,ほかの動詞も同様に無変化活用を示していたことがあった.たとえば,fast, fret, lift, start, waft などである.Jespersen (36) から引用例を再現しよう.

4.42. The influence of analogy has increased the number of invariable verbs. Especially verbs ending in -t tend in this direction. The tendency perhaps culminated in early ModE, when several words now regular had unchanged forms, sometimes side by side with forms in -ed:

fast. Sh Cymb IV. 2.347 I fast and pray'd for their intelligense. || fret. More U 75 fret prt. || lift (from ON). AV John 8.7 hee lift vp himselfe | ib 8.10 when Iesus had lift vp himselfe (in AV also regular forms) | Mi PL 1. 193 With Head up-lift above the wave | Bunyan P 19 lift ptc. || start. AV Tobit 2.4 I start [prt] vp. || waft. Sh Merch. V. 1.11 Stood Dido .. and waft her Loue To come again to Carthage | John II. 1.73 a brauer choice of dauntlesse spirits Then now the English bottomes haue waft o're.

Jespersen のいうように,これらは歴史的に,あるいは音韻変化によって説明できるタイプの無変化動詞というよりは,あくまで set など既存の歴史的な無変化動詞に触発された,類推作用 (analogy) の結果として生じた無変化動詞とみるべきだろう.その点では2次的な無変化動詞と呼んでもよいかもしれない.これらは現代までには標準英語からは消えたとはいえ,重要性がないわけではない.というのは,それらが新たな類推のモデルとなって,次なる類推を呼んだ可能性もあるからだ.つまり,語幹が -t で終わるが,従来の語のように単音節でもなければゲルマン系由来でもないものにすら,同現象が拡張したと目されるからだ.ここで念頭に置いているのは,過去の記事でも取りあげた -ate 動詞などである(「#3764. 動詞接尾辞 -ate の起源と発達」 ([2019-08-17-1]) を参照).

同じく Jespersen (36--37) より,この旨に関する箇所を引用しよう.

4.43. It was thus not at all unusual in earlier English for a ptc in -t to be = the inf. The analogy of these cases was extended even to a series of words of Romantic origin, namely such as go back to Latin passive participle, e. g. complete, content, select, and separate. These words were originally adopted as participles but later came to be used also as infinitives; in older English they were frequently used in both functions (as well as in the preterit), often with an alternative ptc. in -ed; . . . A contributory cause of their use as verbal stems may have been such Latin agent-nouns as corruptor and editor; as -or is identical in sound with -er in agent-nouns, the infinitives corrupt and edit may have been arrived at merely through subtraction of the ending -or . . . . Finally, the fact that we have very often an adj = a vb, e. g. dry, empty, etc . . ., may also have contributed to the creation of infs out of these old ptcs (adjectives).

引用の後半で,類推のモデルがほかにも2つある点に触れているのが重要である.corruptor, editor タイプからの逆成 (back_formation),および dry, empty タイプの動詞・形容詞兼用の単語の存在である.「#1748. -er or -or」 ([2014-02-08-1]),「#438. 形容詞の比較級から動詞への転換」 ([2010-07-09-1]) も参照.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

2019-08-17 Sat

■ #3764. 動詞接尾辞 -ate の起源と発達 [suffix][-ate][adjective][participle][verb][word_formation][loan_word][latin][french][conversion][morphology][analogy]

昨日の記事「#3763. 形容詞接尾辞 -ate の起源と発達」 ([2019-08-16-1]) に引き続き,接尾辞 -ate の話題.動詞接尾辞の -ate については「#2731. -ate 動詞はどのように生じたか?」 ([2016-10-18-1]) で取り上げたが,今回はその起源と発達について,OED -ate, suffix1 を参照しながら,もう少し詳細に考えてみよう.

昨日も述べたように,-ate はラテン語の第1活用動詞の過去分詞接辞 -ātus, -ātum, -āta に遡るから,本来は動詞の語尾というよりは(過去分詞)形容詞の語尾というべきものである.動詞接尾辞 -ate の起源を巡る議論で前提とされているのは,-ate 語に関して形容詞から動詞への品詞転換 (conversion) が起こったということである.形容詞から動詞への品詞転換は多くの言語で認められ,実際に古英語から現代英語にかけても枚挙にいとまがない.たとえば,古英語では hwít から hwítian, wearm から wearmian, bysig から bysgian, drýge から drýgan が作られ,それぞれ後者の動詞形は近代英語期にかけて屈折語尾を失い,前者と形態的に融合したという経緯がある.

ラテン語でも同様に,形容詞から動詞への品詞転換は日常茶飯だった.たとえば,siccus から siccāre, clārus から clārāre, līber から līberāre, sacer から sacrāre などが作られた.さらにフランス語でも然りで,sec から sècher, clair から clairer, content から contenter, confus から confuser などが形成された.英語はラテン語やフランス語からこれらの語を借用したが,その形容詞形と動詞形がやはり屈折語尾の衰退により15世紀までに融合した.

こうした流れのなかで,16世紀にはラテン語の過去分詞形容詞をそのまま動詞として用いるタイプの品詞転換が一般的にみられるようになった.direct, separate, aggravate などの例があがる.英語内部でこのような例が増えてくると,ラテン語の -ātus が,歴史的には過去分詞に対応していたはずだが,共時的にはしばしば英語の動詞の原形にひもづけられるようになった.つまり,過去分詞形容詞的な機能の介在なしに,-ate が直接に動詞の原形と結びつけられるようになったのである.

この結び付きが強まると,ラテン語(やフランス語)の動詞語幹を借りてきて,それに -ate をつけさえすれば,英語側で新しい動詞を簡単に導入できるという,1種の語形成上の便法が発達した.こうして16世紀中には fascinate, concatenate, asseverate, venerate を含め数百の -ate 動詞が生み出された.

いったんこの便法が確立してしまえば,実際にラテン語(やフランス語)に存在したかどうかは問わず,「ラテン語(やフランス語)的な要素」であれば,それをもってきて -ate を付けることにより,いともたやすく新しい動詞を形成できるようになったわけだ.これにより nobilitate, felicitate, capacitate, differentiate, substantiate, vaccinate など多数の -ate 動詞が近現代期に生み出された.

全体として -ate の発達は,語形成とその成果としての -ate 動詞群との間の,絶え間なき類推作用と規則拡張の歴史とみることができる.

2019-08-16 Fri

■ #3763. 形容詞接尾辞 -ate の起源と発達 [suffix][-ate][adjective][participle][word_formation][loan_word][latin][french][conversion][morphology]

英語で典型的な動詞語尾の1つと考えられている -ate 接尾辞は,実はいくつかの形容詞にもみられる.aspirate, desolate, moderate, prostrate, sedate, separate は動詞としての用法もあるが,形容詞でもある.一方 innate, oblate, ornate, temperate などは常に形容詞である.形容詞接尾辞としての -ate の起源と発達をたどってみよう.

この接尾辞はラテン語の第1活用動詞の過去分詞接辞 -ātus, -ātum, -āta に遡る.フランス語はこれらの末尾にみえる屈折接辞 -us, -um, -a を脱落させたが,英語もラテン語を取り込む際にこの脱落の慣習を含めてフランス語のやり方を真似た.結果として,英語は1400年くらいから,ラテン語 -atus などを -at (のちに先行する母音が長いことを示すために e を添えて -ate) として取り込む習慣を獲得していった.

上記のように -ate の起源は動詞の過去分詞であるから,英語でも文字通りの動詞の過去分詞のほか,形容詞としても機能していたことは無理なく理解できるだろう.しかし,後に -ate が動詞の原形と分析されるに及んで,本来的な過去分詞の役割は,多く新たに規則的に作られた -ated という形態に取って代わられ,過去分詞(形容詞)としての -ate の多くは廃用となってしまった.しかし,形容詞として周辺的に残ったものもあった.冒頭に挙げた -ate 形容詞は,そのような経緯で「生き残った」ものである.

以上の流れを解説した箇所を,OED の -ate, suffix2 より引こう.

Forming participial adjectives from Latin past participles in -ātus, -āta, -ātum, being only a special instance of the adoption of Latin past participles by dropping the inflectional endings, e.g. content-us, convict-us, direct-us, remiss-us, or with phonetic final -e, e.g. complēt-us, finīt-us, revolūt-us, spars-us. The analogy for this was set by the survival of some Latin past participles in Old French, as confus:--confūsus, content:--contentus, divers:--diversus. This analogy was widely followed in later French, in introducing new words from Latin; and both classes of French words, i.e. the popular survivals and the later accessions, being adopted in English, provided English in its turn with analogies for adapting similar words directly from Latin, by dropping the termination. This began about 1400, and as in -ate suffix1 (with which this suffix is phonetically identical), Latin -ātus gave -at, subsequently -ate, e.g. desolātus, desolat, desolate, separātus, separat, separate. Many of these participial adjectives soon gave rise to causative verbs, identical with them in form (see -ate suffix3), to which, for some time, they did duty as past participles, as 'the land was desolat(e by war;' but, at length, regular past participles were formed with the native suffix -ed, upon the general use of which these earlier participial adjectives generally lost their participial force, and either became obsolete or remained as simple adjectives, as in 'the desolate land,' 'a compact mass.' (But cf. situate adj. = situated adj.) So aspirate, moderate, prostrate, separate; and (where a verb has not been formed), innate, oblate, ornate, sedate, temperate, etc. As the French representation of Latin -atus is -é, English words in -ate have also been formed directly after French words in --é, e.g. affectionné, affectionate.

つまり,-ate 接尾辞は,起源からみればむしろ形容詞にふさわしい接尾辞というべきであり,動詞にふさわしい接尾辞へと変化したのは,中英語期以降の新機軸ということになる.なぜ -ate が典型的な動詞接尾辞となったのかという問題を巡っては,複雑な歴史的事情がある.これについては「#2731. -ate 動詞はどのように生じたか?」 ([2016-10-18-1]) を参照(また,明日の記事でも扱う予定).

接尾辞 -ate については,強勢位置や発音などの観点から「#1242. -ate 動詞の強勢移行」 ([2012-09-20-1]),「#3685. -ate 語尾をもつ動詞と名詞・形容詞の発音の違い」 ([2019-05-30-1]),「#3686. -ate 語尾,-ment 語尾をもつ動詞と名詞・形容詞の発音の違い」 ([2019-05-31-1]),「#1383. ラテン単語を英語化する形態規則」 ([2013-02-08-1]) をはじめ,-ate の記事で取り上げてきたので,そちらも参照されたい.

2019-06-17 Mon

■ #3703.『英語教育』の連載第4回「なぜ比較級の作り方に -er と more の2種類があるのか」 [notice][hel_education][elt][sobokunagimon][adjective][adverb][comparison][rensai][latin][french][synthesis_to_analysis][link]

6月14日に,『英語教育』(大修館書店)の7月号が発売されました.英語史連載記事「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ」の第4回目として拙論「なぜ比較級の作り方に -er と more の2種類があるのか」が掲載されています.是非ご覧ください.

形容詞・副詞の比較表現については,本ブログでも (comparison) の各記事で扱ってきました.以下に,今回の連載記事にとりわけ関連の深いブログ記事のリンクを張っておきますので,あわせて読んでいただければ,-er と more に関する棲み分けの謎について理解が深まると思います.

・ 「#3617. -er/-est か more/most か? --- 比較級・最上級の作り方」 ([2019-03-23-1])

・ 「#3032. 屈折比較と句比較の競合の略史」 ([2017-08-15-1])

・ 「#456. 比較の -er, -est は屈折か否か」 ([2010-07-27-1])

・ 「#2346. more, most を用いた句比較の発達」 ([2015-09-29-1])

・ 「#403. 流れに逆らっている比較級形成の歴史」 ([2010-06-04-1])

・ 「#2347. 句比較の発達におけるフランス語,ラテン語の影響について」 ([2015-09-30-1])

・ 「#3349. 後期近代英語期における形容詞比較の屈折形 vs 迂言形の決定要因」 ([2018-06-28-1])

・ 「#3619. Lowth がダメ出しした2重比較級と過剰最上級」 ([2019-03-25-1])

・ 「#3618. Johnson による比較級・最上級の作り方の規則」 ([2019-03-24-1])

・ 「#3615. 初期近代英語の2重比較級・最上級は大言壮語にすぎない?」 ([2019-03-21-1])

・ 堀田 隆一 「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ 第4回 なぜ比較級の作り方に -er と more の2種類があるのか」『英語教育』2019年7月号,大修館書店,2019年6月14日.62--63頁.

2019-04-18 Thu

■ #3643. many years ago の ago とは何か? [adjective][adverb][participle][reanalysis][be][perfect][sobokunagimon]

現代英語の副詞 ago は,典型的に期間を表わす表現の後におかれて「?前に」を表わす.a moment ago, a little while ago, some time ago, many years ago, long ago などと用いる.

この ago は語源的には,動詞 go に接頭辞 a- を付した派生動詞 ago (《時が》過ぎ去る,経過する)の過去分詞形 agone から語尾子音が消えたものである.要するに,many years ago とは many years (are) (a)gone のことであり,be とこの動詞の過去分詞 agone (後に ago)が組み合わさって「何年もが経過したところだ」と完了形を作っているものと考えればよい.

OED の ago, v. の第3項には,"intransitive. Of time: to pass, elapse. Chiefly (now only) in past participle, originally and usually with to be." とあり,用例は初期古英語という早い段階から文証されている.早期の例を2つ挙げておこう.

・ eOE Anglo-Saxon Chron. (Parker) Introd. Þy geare þe wæs agan fram Cristes acennesse cccc wintra & xciiii uuintra.

・ OE West Saxon Gospels: Mark (Corpus Cambr.) xvi. 1 Sæternes dæg wæs agan [L. transisset].

このような be 完了構文から発達した表現が,使われ続けるうちに be を省略した形で「?前に」を意味する副詞句として再分析 (reanalysis) され,現代につらなる用法が発達してきたものと思われる.別の言い方をすれば,独立分詞構文 many years (being) ago(ne) として発達してきたととらえてもよい.こちらの用法の初出は,OED の ago, adj. and adv. によれば,14世紀前半のことである.いくつか最初期の例を挙げよう.

・ c1330 (?c1300) Guy of Warwick (Auch.) l. 1695 (MED) It was ago fif ȝer Þat he was last þer.

・ c1415 (c1395) Chaucer Wife of Bath's Tale (Lansd.) (1872) l. 863 I speke of mony a .C. ȝere a-go.

・ ?c1450 tr. Bk. Knight of La Tour Landry (1906) 158 (MED) It is not yet longe tyme agoo that suche custume was vsed.

MED では agōn v. の 5, 6 に類例が豊富に挙げられているので,そちらも参照.

2019-03-28 Thu

■ #3622. latter の形態を説明する古英語・中英語の "Pre-Cluster Shortening" [consonant][vowel][shortening][adjective][comparison][sound_change][etymology][shocc]

「#3616. 語幹母音短化タイプの比較級に由来する latter, last, utter」 ([2019-03-22-1]) で取り上げたように,中英語では,形容詞の比較級において原級では長い語幹母音が短化するケースがあった.これを詳しく理解するには,古英語および中英語で生じた "Pre-Cluster Shortening" なる音変化の理解が欠かせない.

"Pre-Cluster Shortening" とは,特定の子音群の前で,本来の長母音が短母音へと短化する過程である.音韻論的には,音節が「重く」なりすぎるのを避けるための一般的な方略と解釈される.原理としては,feed, keep, meet, sleep などの長い語幹母音をもつ動詞に歯音を含む過去(分詞)接辞を加えると fed, kept, met, slept と短母音化するのと同一である.あらためて形容詞についていえば,語幹に長母音をもつ原級に対して,子音で始まる古英語の比較級接尾辞 -ra (中英語では -er へ発展)を付した比較級の形態が,短母音を示すようになった例のことを話題にしている.Lass (102) によれば,

Originally long-stemmed adjectives with gemination in the comparative and superlative showing Pre-Cluster Shortening: great 'great'/gretter, similarly reed 'red', whit 'white', hoot 'hot', late. (The old short-vowel comparative of late has been lexicalised as a separate form, later, with new analogical later/latest.)

長母音に子音群が後続すると短母音化する "Pre-Cluster Shortening" は,ありふれた音変化の1種と考えられ,実際に英語音韻史では異なる時代に異なる環境で生じている.Lass (71) によれば,古英語で生じたものは以下の通り(gospel については「#2173. gospel から d が脱落した時期」 ([2015-04-09-1]) を参照).

About the seventh century . . . long vowels shortened before /CC/ if another consonant followed, either in the coda or the onset of the next syllable, as in bræ̆mblas 'branbles' < */bræːmblɑs/, gŏdspel 'gospel' < */goːdspel/. This removes one class of superheavy syllables.

この古英語の音変化は3子音連続の前位置で生じたものだが,初期中英語で生じたバージョンでは2子音連続の前位置で生じている.今回取り上げている形容詞語幹の長短の交替に関与するのは,この初期中英語期のものである (Lass 72--73) .

Long vowels shortened before sequences of only two consonants . . . , and --- variably--- certain ones like /st/ that were typically ambisyllabic . . . . So shortening in kĕpte 'kept' < cēpte (inf. cēpan), mĕtte met < mētte'' (inf. mētan), brēst 'breast' < breŏst 'breast' < brēost. Shortening failed in the same environment in priest < prēost; in words like this it may well be the reflex of an inflected form like prēostas (nom./acc.pl.) that has survived, i.e. one where the /st/ could be interpreted as onset of the second syllable; the same holds for beast, feast from French. This shortening accounts for the 'dissociation' between present and past vowels in a large class of weak verbs, like those mentioned earlier and dream/dreamt, leave/left, lose/lost, etc. (The modern forms are even more different from each other due to later changes in both long and short vowels that added qualitative dissociation to that in length: ME /keːpən/ ? /keptə/, now /kiːp/ ? /kɛpt/, etc.)

latter (および last) は,この初期中英語の音変化による出力が,しぶとく現代まで生き残った事例として銘記されるべきものである.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 2. Cambridge: CUP, 1992. 23--154.

2019-03-25 Mon

■ #3619. Lowth がダメ出しした2重比較級と過剰最上級 [comparison][double_comparative][superlative][lowth][prescriptive_grammar][adjective]

「#2583. Robert Lowth, Short Introduction to English Grammar」 ([2016-05-23-1]) や「#3036. Lowth の禁じた語法・用法」 ([2017-08-19-1]) で紹介したように,規範文法家の第一人者 Robert Lowth による1762年の文法書には様々な語法の禁止条項がみえるが,連日取り上げている形容詞の比較についても,2重比較級 (double_comparative) と,意味的に過剰な最上級へのダメ出しがなされている.Lowth (34--35) より関連箇所を抜き出そう.

[4] Double Comparatives and Superlatives are improper.

"The Duke of Milan, / And his more braver Daughter could controul thee." "After the most straitest sect of our religion I lived a Pharisee." Shakespeare, Tempest. Acts xxvi. 5. So likewise Adjectives, that have in themselves a Superlative signification, admit not properly the Superlative form superadded: "Whosoever of you will be chiefest, shall be servant of all." Mark x. 44. "One of the first and chiefest instances of prudence." Atterbury, Serm. IV. "While the extremest parts of the earth were meditating a submission." Ibid. I. 4.

"But first and chiefest with thee bring

Him, that you soars on golden wing,

Guiding the fiery-wheeled throne,

The Cherub Contemplation." Milton, Il Penseroso.

"That on the sea's extremest border stood." Addison, Travels.

But poetry is in possession of these two improper Superlatives, and may be indulged in the use of them.

. . . .

[5] "Lesser, says Mr. Johnson, is a barbarous corruption of Less, formed by the vulgar from the habit of terminating comparisons in er."

"Attend to what a lesser Muse indites." Addison.

Worser sounds much more barbarous, only because it has not been so frequently used:

"Chang'd to a worser shape thou canst not be." Shakespeare, 1 Hen. VI.

"A dreadful quiet felt, and worser far / Than arms, a sullen interval of war." Dryden.

ダメだしされているのは more braver, lesser, worser のような2重比較級,most straitest のような2重最上級,そして chiefest, extremest のようにもともと最上級に相当する意味をもっている形容詞をさらに最上級化する過剰最上級の例である.しかも,槍玉にあがっているのは Shakespeare, Milton, Addison, Dryden などの大物揃いだから読み応えがある(この戦略も Lowth の常套手段である).なお,lesser は現在では普通に用いられていることに注意.

Shakespeare の worser 使用については「#195. Shakespeare に関する Web resources」 ([2009-11-08-1]) を参照されたい.また,Dryden はここで worser の使用ゆえに Lowth によって断罪されているが,「#3220. イングランド史上初の英語アカデミーもどきと Dryden の英語史上の評価」 ([2018-02-19-1]) で触れたように,実は Dryden 自身が2重比較を非難していたのである.

近代英語における2重比較については「#3615. 初期近代英語の2重比較級・最上級は大言壮語にすぎない?」 ([2019-03-21-1]) も要参照.

・ Lowth, Robert. A Short Introduction to English Grammar. 1762. New ed. 1769. (英語文献翻刻シリーズ第13巻,南雲堂,1968年.9--113頁.)

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow