2023-08-31 Thu

■ #5239. t の弾音化はいつから? --- Mond の質問 [mond][sobokunagimon][phonetics][r][ame]

先日,知識共有サービス Mond でいただいた質問に回答しました.

![[t] の弾音化はいつから? --- Mond の質問](lib/mond_20230831.png)

結論としては,t の弾音化 (flapping or tapping) は遅くとも中英語以降に生じていた,ということになります.イングランドで異音として行なわれていたものが,17世紀以降にアメリカを含む世界各地に移植・継承されたものと思われます.t の弾音化はアメリカ英語に典型的な特徴であるという印象が強いですが,その他の多くのアメリカ英語の特徴とともに,実際の起源は中世イングランドに求められそうです.

回答記事では今回の調査に際して当たった典拠を記していませんでしたが,主に Dobson (Vol. 2, p. 956) と Minkova (147--48) に拠りました.Dobson の記述をメモとして残しておきます.

(4) Intervocalic [t] becomes [r]

385. From early in the sixteenth century there appear the forms porridge, porringer, &c. for earlier pottage, potager (see OED, s.vv.), though the older forms also survived (thus Salesbury has potanger and Bullokar potage). Coles gives porridg and porringer as 'phonetic' spellings of pottage and pottinger, from which it appears that written forms with t may sometimes conceal spoken forms with [r].

関連して「#61. porridge は愛情をこめて煮込むべし」 ([2009-06-28-1]),および r と rhotic の記事群も参照.

・ Dobson, E. J. English Pronunciation 1500--1700. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Oxford: OUP, 1968.

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

2021-09-19 Sun

■ #4528. イギリス諸島の周辺地域に残る3つの発音 [pronunciation][h][r][rhotic][vowel][centralisation][phonology][phonetics][phoneme][substratum_theory][celtic_hypothesis][cockney]

イギリス諸島全体のなかで中心的な英語といえば,ブリテン島のイングランドのロンドンを中心とするイングランド南部標準英語のことを指すのが普通である.これ以外のイングランドの南西部・中部・北部や,ウェールズ,スコットランド,アイルランド,その他の島嶼部などをまとめて周辺地域と呼ぶことにすると,この周辺地域の英語変種にはしばしば古い言語特徴 (relic features) が観察される.音韻論的な特徴として,Corrigan (355) より3つの有名な事例を挙げておこう.

(1) "FOOT/STRUT split"

歴史的な /ʊ/ が,中心地域で /ʊ/ と /ʌ/ に分裂した音韻変化をさす.17世紀に生じた中舌化 (centralisation) と呼ばれる過程で,これにより母音音素が1つ増えたことになる.一方,周辺地域では分裂は起こっていないために foot と strut は相変わらず /ʊt/ で脚韻を踏む.「#1297. does, done の母音」 ([2012-11-14-1]) で方言地図を示したように,分裂の有無の方言分布は明確である.

(2) "non-prevocalic /r/"

この話題は本ブログでも rhotic の多くの記事で話題にしてきた.「#452. イングランド英語の諸方言における r」 ([2010-07-23-1]) に方言地図を掲載しているが,周辺部では母音前位置に来ない歴史的な r が実現され続けているが,中心部では実現されない.スコットランドやアイルランドも rhotic である(ただしウェールズでは一部を除き non-rhotic である).

(3) "h-dropping"

Cockney 発音としてよく知られている h が脱落する現象.実は Cockney に限らず,初期近代英語期以降,中心地域で広く行なわれてきた.h-dropping は地域変種としての特徴ではなく社会変種としての特徴とみられることが多いが,周辺地域の変種ではあまり見られないという事実もあり,ことは単純ではない.ケルト系の基層をもつ英語変種では一般的に語頭の h が保持されている.

このように周辺地域は古い特徴を保持していることが多いが,純粋に地理的な観点から分布を説明するだけで十分なのだろうか.これらの地域は,地理的な意味で周辺であるだけでなく,ケルト系言語・方言を基層にもつ英語変種が行なわれている地域として民族的な意味でも周辺である.Corrigan は上記の特徴がケルト語基層仮説によるものだと強く主張しているわけではないが,それを示唆する書き方で紹介している.

・ Corrigan, Karen P. "The Atlantic Archipelago of the British Isles." Chapter 17 of The Oxford Handbook of World Englishes. Ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, and Devyani Sharma. New York: OUP, 2017. 335--70.

2021-09-12 Sun

■ #4521. 英語史上の主要な母音変化 [sound_change][vowel][phonetics][phonology][diphthong][gvs][r]

「#3386. 英語史上の主要な子音変化」 ([2018-08-04-1]) の母音版を書いていなかったので,今回は英語史における母音の音変化について,主要なものをまとめたい.

とはいっても,英語史上の音変化は「#1402. 英語が千年間,母音を強化し子音を弱化してきた理由」 ([2013-02-27-1]) からも示唆されるように,母音変化のほうがずっと種類や規模が著しい.したがって,少数の主な変化にまとめ上げるのも難しい.そこで,Cruttenden (72) に従って,古英語と現代英語の母音体系を比較対照したときに際立つポイントを6点挙げることで,この難題の当面の回答としたい.

(1) OE rounded front vowels [yː, ʏ] were lost by ME (following even earlier loss of [øː, œ]).

(2) Vowels in weakly accented final syllables (particularly in suffixes) were elided or obscured to [ə] or [ɪ] in ME or eModE.

(3) All OE long vowels closed or diphthongised in eModE or soon after.

(4) Short vowels have remained relatively stable. The principal exception is the splitting of ME [ʊ] into [ʌ] and [ʊ], the latter remaining only in some labial and velar contexts.

(5) ME [a] was lengthened and retracted before [f,θ,s] in the eighteenth century.

(6) The loss of post-vocalic [r] in the eighteenth century gave rise to the centring diphthongs /iə,eə,ɔə,ʊə/ (later /ɔə/ had merged with /ɔː/ by 1950 and /eə/ became /ɛː/ by 2000). The pure vowel /ɜː/ arose in the same way and the same disappearance of post-vocalic [r] introduced /ɑː,ɔː/ into new categories of words, e.g. cart, port

(3) がいわゆる「大母音推移」 (gvs) に関連する変化である,

英語史上の多数の母音変化のなかで何を重視して有意義とするかというのはなかなか難しい問題なのだが,こうして少数の項目に絞って提示されると妙に納得する.非常に参考になるリストであることは間違いない.

・ Cruttenden, Alan. Gimson's Pronunciation of English. 8th ed. Abingdon: Routledge, 2014.

2020-09-23 Wed

■ #4167. なぜ英語では l と r が区別されるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版 [hellog-radio][sobokunagimon][hel_education][pronunciation][consonant][l][r][dissimilation]

今回の hellog ラジオ版の話題は,日本語母語話者が苦手とされる英語の l と r の区別についてです.同じラ行音として r ひとつで済ませれば楽なはずなのに,なぜ英語ではわざわざ l と r と2つの音に分けるのか.そのような面倒は,ぜひやめてほしい! という訴えももっともなことです.I eat rice. (私は米を食べます)と I eat lice. (私はしらみを食べます),I love you. (あなたを愛しています)と I rub you. (あなたをこすります)など,日本語母語話者が l と r の区別が下手であることをダシにした,ちょっと頭に来るジョークもあります.これは何とかお返しをしなければ.

ということで,以下の解説をお聴きください.異化 (dissimilation) の解説でもあります.

英語では現在のみならず歴史的にもずっと l と r が異なる音素として区別されてきました.しかし,音声学的にいって両音が似ていることは確かですし,両音が取っ替え引っ替えされてきたことは pilgrim, marble, colonel 等の英単語のたどってきた歴史のなかに確認されるのです.l と r は英語でもやっぱり似てたんじゃん!

今回の話題に関心をもった方は,ぜひ##72,1618,1817,3684,3016,3904,3940の記事セットをどうぞ.

2020-08-13 Thu

■ #4126. NURSE Merger の諸相 [sound_change][phonetics][centralisation][vowel][merger][assimilation][rhotic][r][walker]

「#3507. NURSE Merger」 ([2018-12-03-1]),「#4068. 初期近代英語の -ir, -er, -ur の融合の音声学的メカニズム」 ([2020-06-16-1]) の記事で,r の前位置の母音が歴史的に融合してきた過程に注目した.初期近代英語の音変化の大家である Dobson (724) も "No consonant exercises greater or more varied influence on the development of the words in ME and ModE than r." と述べている通り,近代英語史上きわめて影響力の大きな音変化である.

この音変化について Hickey の論文を読む機会があった.要点がまとめられていて有益なので,その箇所を引用しよう (99--100) .

The BIRD-TERM-NURSE merger

For his discussion of short vowel centralisation before /r/ Dobson discusses /ɛ/, /ɪ/ and /ʌ/ separately and in that order. However, he sees the development of all three vowels as similar and as having taken place in the early seventeenth century, in "Standard English", though earlier "in the dialects" (Dobson 1968, 746). The centralisation took place "because of the influence of the following r to the central vowel [ə]". He continues to state that "[t]he reason for the retraction was to anticipate the pronunciation of the r, for [ə] is a vowel closely allied to the ModE [r]". Lass (2006, 91) sees the centralisation for all three ME vowels as having taken place somewhat later and mentions Nares (1794) as the first writer to say that "vergin, virgin and vurgin would be pronounced alike".

Dobson (1968, 746) states that the schwa vowel "must have been of approximately the same quality as PresE [ə] which later develops from it when the r is vocalized to [ə]". There is an important conclusion from these remarks, namely that centralisation presupposes the existence of a following /r/ so that the loss of rhoticity must be dated after the centralisation. Confirmation of this is found from prescriptive authors of the eighteenth century. For instance, John Walker in his Critical Pronouncing Dictionary of 1791 has 'bu2rd' for bird, his u2 represents schwa (in his principle 172 he states that the vowel value is the same as that in done, son). Walker also transcribes bird with "r" but we know that he favoured the retention of non-prevocalic /r/ even though he recognised that it was rapidly losing ground during his lifetime.

ここから NURSE Merger のクロノロジーについて改めてポイントを抜き出すと,次のようになる.

(1) 融合が生じた時期は,17世紀初期から18世紀末までと諸説間に幅がある

(2) 標準英語では非標準英語よりも遅かった

(3) まず前舌母音どうしが中舌化して融合し,その後に後舌母音が融合した

(4) 問題の母音の融合は /r/ の消失の前に生じた

・ Dobson, E. J. English Pronunciation 1500--1700. 1st ed. Oxford: Clarendon, 1957. 2 vols.

・ Hickey, Raymond. "Vowels before /r/ in the History of English." Contact, Variation, and Change in the History of English. Ed. Simone E. Pfenninger, Olga Timofeeva, Anne-Christine Gardner, Alpo Honkapohja, Marianne Hundt and Daniel Schreier. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins, 2014. 95--110.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." A History of the English Language. Ed. Richard Hogg and David Denison. Cambridge: CUP, 2006. 43--108.

・ Nares, Robert. Elements of Orthoepy. 1794. Reprint. Menston: Scolar P, 1968.

2020-06-16 Tue

■ #4068. 初期近代英語の -ir, -er, -ur の融合の音声学的メカニズム [rhotic][r][vowel][sound_change][emode][phonetics][centralisation][merger][assimilation]

標記の音変化は,本ブログでもすでに扱ったように「#3507. NURSE Merger」 ([2018-12-03-1]) と呼ばれている.その音声学的メカニズムについて Minkova (277--78) の解説を聞いてみよう.

A coda /-r/ is a neutralising environment. For the short vowels neutralisation of [ɪ], [ʊ], [ɛ] results in merger into the featurally neutral schwa outcome. The phonetic rationale behind this is the coarticulation of the short vowel + /-r/ which affects both segments: it lowers and centralises the vowel, while the adjacent sonorant coda becomes more schwa-like; its further weakening can eliminate the consonantal cues, leading to complete loss of the consonantal properties of /r/. The difficulty of perceiving the distinctive features of pre-/r/ vowels is attributed to the acoustic similarity of the first two formants of [ɹ], [ɻ], and [ə ? ɨ] . . . .

音節末 (coda) の /r/ は,直前の母音を中舌化(いわゆる曖昧母音化)させ,それにより /r/ 自身も子音的性質を減じて中舌母音に近づく.結果として,/r/ は子音性を完全に失うことになり,直前の短母音と合流して対応する長母音となる,という顛末だ.本来は固有の音声的性質を保持していた2音が,相互に同化 (assimilation) し,ついには弛緩しきった [əː] へと終結したという,何だか哀れなような,だらしないような結果だが,これが英単語の語末には溢れているのだから仕方ない.

関連して,「#2274. heart の綴字と発音」 ([2015-07-19-1]) の記事もどうぞ.

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

2020-06-15 Mon

■ #4067. 「長母音+ /r/」が経た音変化 [rhotic][r][vowel][diphthong][triphthong][sound_change][gvs]

後期中英語の「長母音+ /r/」あるいは「2重母音+ /r/」の音連鎖は,近代英語期にかけていくつかの互いに密接な音変化を経てきた.以下,Minkova (279) が挙げている一覧を再現しよう.ここで念頭にあるタイムスパンは,後期中英語から18?19世紀にかけてである.

| Late ME to EModE | Schwa-insertion | Length adjustment | /-r/-loss | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -əir ? -ʌir | -aiər | -aɪər | -aɪə | fire (OE fȳr) |

| -eː̝r ? -iːr | -iːər | -ɪər | -ɪə | deer (OE dēor) |

| -ɛːr ? -e̝ːr ? -iːr | -iːər | -ɪər | -ɪə | ear (OE ēare) |

| -ɛːr ? -eːr | -eːər | -ɛər | -ɛə | pear (OE pere) |

| -æːr ? -ɛːr | -ɛːər | -ɛər | -ɛə | hare (OE hara) |

| -ɔːr | -ɔː(ə)r | -ɔ(ː)(ə)r | -ɔ(ː)(ə) | oar (OE ār) |

| -oːr | -ɔː(ə)r | -ɔ(ː)(ə)r | -ɔ(ː)(ə) | floor (OE flōr) |

| -oː̝r ? -uːr | -uːər | -ʊər | -ʊə | poor (AN pover, pour) |

| -əur ? -ʌur | -auər | -aʊər | -aʊə | bower (OE būr) |

このように Minkova (278) は,(1) schwa-insertion, or breaking, (2) pre-shwa-laxing, or length adjustment, (3) /-r/-loss という3つの音過程が関与したことを前提としている.また,厳密に上記の順序で音過程が進行したかどうかは確定できないものの,non-rhotic 変種が辿った経路のモデルとして,上記を提示したとも述べている.

non-rhotic 変種では,これらの音変化の結果として,いくつかの新種の2重母音や3重母音が現われたことになる.

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2020-06-14 Sun

■ #4066. /r/ 消失を開始・推進した要因と阻止した要因 [rhotic][r][sound_change][orthography][french][contact][ame_bre][emode][causation][multiple_causation]

「rhotic なアメリカ英語」と「non-rhotic なイギリス英語」という対立はよく知られている.しかし,この対立は単純化してとらえられるきらいがあり,実際にはアメリカ英語で non-rhotic な変種もあれば,イギリス英語で rhotic な変種もある.アメリカ英語の一部でなぜ non-rhotic な発音が行なわれているかについては込み入った歴史があり,詳細はいまだ明らかにされていない (cf. 「#3953. アメリカ英語の non-rhotic 変種の起源を巡る問題」 ([2020-02-22-1])) .

そもそも non-rhotic な発音を生み出すことになった /r/ 消失という音変化は,なぜ始まったのだろうか.Minkova (280) は,/r/ 消失に作用した音声学的,社会言語学的要因を指摘しつつ,一方で綴字に固定化された <r> が同音の消失傾向に歯止めをかけたがために,複雑な綱引き合いの結果として,rhotic と non-rhotic の両発音が並存することになっているのだと説く.

While loss of /r/ may be described as 'natural' in a phonetic sense, it is still unclear why some communities of speakers preserved it when others did not. One reason why the change may have taken off in the first place, not usually considered in the textbook accounts, is loan phonology. In Later Old French (eleventh to fourteenth century) and Middle French (fourteenth to sixteenth century), pre-consonantal [r] was assimilated to the following consonant and thereby lost in the spoken language (it is retained in spelling to this day), producing rhymes such as sage : large, fors : clos, ferme : meesme. Thus English orthography was at odds with the functional factor of ease of articulation and with the possibly prestigious pronunciation of recent loanwords in which pre-consonantal [-r] had been lost. This may account for the considerable lag time for the diffusion and codification of [r]-loss in early Modern English. Rhotic and non-rhotic pronunciations must have coexisted for over three centuries, even in the same dialects. . . . [C]onservatism based on spelling maintained rhoticity in the Southern standard until just after the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

上で触れられているフランス語の "loan phonology" が関与していたのではないかという仮説は,斬新な視点である.

「自然な」音過程,フランス語における /r/ 消失,綴字における <r> の保持 --- これらの /r/ 消失を開始し推進した音声学的,社会言語学的要因と,それを阻止しようと正書法的要因とが,長期にわたる綱引きを繰り広げ,結果的に1700年頃から現在までの300年以上にわたって rhotic と non-rhotic の両発音を共存させ続けてきたということになる.

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

2020-02-09 Sun

■ #3940. 形容詞を作る接尾辞 -al と -ar [suffix][adjective][morphology][dissimilation][r][l]

英語の形容詞を作る典型的な接尾辞 (suffix) に -al がある.abdominal, chemical, dental, editorial, ethical, fictional, legal, magical, medical, mortal, musical, natural, political, postal, regal, seasonal, sensational, societal, tropical, verbal など非常に数多く挙げることができる.これはラテン語の形容詞を作る接尾辞 -ālis (pertaining to) が中英語期にフランス語経由で入ってきたもので,生産的である.

よく似た接尾辞に -ar というものもある.これも決して少なくない.angular, cellular, circular, insular, jocular, linear, lunar, modular, molecular, muscular, nuclear, particular, polar, popular, regular, singular, spectacular, stellar, tabular, vascular など多数の例が挙がる.この接尾辞の起源はやはりラテン語にあり,形容詞を作る -āris (pertaining to) にさかのぼる.両接尾辞の違いは l と r だけだが,互いに関係しているのだろうか.

答えは Yes である.これは典型的な l と r の異化 (dissimilation) の例となっている.ラテン語におけるデフォルトの接尾辞は -ālis の方だが,基体に l が含まれるときには l 音の重複を嫌って,接尾辞の l が r へと異化した.特に基体が「子音 + -le」で終わる場合には,音便として子音の後に u が挿入され (anaptyxis) ,派生形容詞は -ular という語尾を示すことになる.

l と r の異化については,「#72. /r/ と /l/ は間違えて当然!?」 ([2009-07-09-1]),「#1597. star と stella」 ([2013-09-10-1]),「#1614. 英語 title に対してフランス語 titre であるのはなぜか?」 ([2013-09-27-1]),「#3016. colonel の綴字と発音」 ([2017-07-30-1]),「#3684. l と r はやっぱり近い音」 ([2019-05-29-1]),「#3904. coriander の第2子音は l ではなく r」 ([2020-01-04-1]) も参照.

2020-01-04 Sat

■ #3904. coriander の第2子音は l ではなく r [dissimilation][r][l][wycliffe]

香味料として知られる coriander (コリアンダー)が,中英語では coliandre などの l をもつ異形が行なわれていたということを知った.r と l が入れ替わる現象,特に語中に同じ子音が2つ現われる場合に一方が交替する現象は,異化 (dissimilation) として知られており,頻繁とはいえずとも決して稀ではない.次の記事を参照.

・ 「#72. /r/ と /l/ は間違えて当然!?」 ([2009-07-09-1])

・ 「#259. phonaesthesia と 異化」 ([2010-01-11-1])

・ 「#3016. colonel の綴字と発音」 ([2017-07-30-1])

・ 「#3229. 2月,February,如月」 ([2018-02-28-1])

・ 「#3684. l と r はやっぱり近い音」 ([2019-05-29-1])

MED を引いてみると,coria(u)ndre (n.) と colia(u)ndre (n.) が別見出しで立てられている.他の語源辞典の情報から考え合わせると,r を示す前者の形態については,L coriandrum > OF coriandre > ME coria(u)ndre というストレートな借用の流れが想定されているようだ.一方,l を示す後者の形態については,L coriandrum > VL *coliandru(m) > OF coliandre > ME colia(u)ndre のように,俗ラテン語の段階で異化を経たものが中英語に入ったというルートが想定されている.

おもしろいのは,MED のそれぞれの見出しのもとに次のような Wycliffite Bible からの用例が掲載されていることだ.Early Version では r 形と l 形の両方が使われていることが確認される.

・ a1425 (a1382) WBible(1) (Corp-O 4) Num.11.7: Manna forsothe was as the seed coryaundre [WB(2): seed of coriaundre], of the colour of bdelli.

・ a1425 (a1382) WBible(1) (Corp-O 4) Ex.16.31: The hows of Yrael clepide the name of it man, that was as the seed of coliaundre [WB(2): coriandre] white, and the taast of it as of tryed floure with hony.

また,同時代の文法書においても,語源形との関係について指摘がみえる.

・ a1425 *Medulla (Stnh A.1.10)17b/b: Coriandrum: coliandre.

ついでに OED を参照してみると,ここでも coriander と †coliander の2つの見出しが立てられているが,後者の初出のほうが早い(以下の例文).ただし,この l 形は初期近代英語期の例を最後に廃用となっている.

・ c1000 Sax. Leechd. I. 218 Genim þas wyrte þe man coliandrum & oðrum naman þam gelice cellendre nemneð.

結果的としてみれば,異化を経ていない「正統」の形態が現代標準語に受け継がれたことになるが,中英語期に両形が共時的に並存していたというのはおもしろい.通常,異化は「r が l に変化した」などの通時的な現象として語られるが,両形の共存という共時的な観点から眺めてみるのも1つの洞察だろう.

2019-08-28 Wed

■ #3775. 英語は開音節を目指して音変化を起こしている [sound_change][phonetics][phonology][r][l][consonant][syllable][vowel][stress][rhythm][prosody]

「#3719. 日本語は開音節言語,英語は閉音節言語」 ([2019-07-03-1]) でみたように,英語は類型論的にいえば有標の音節タイプである閉音節を多くもつ言語であることは事実だが,それでも英語の音変化の潮流を眺めてみると,英語は無標の開音節を志向していると考えられそうである.

安藤・澤田は現代英語にみられる r の弾音化 (flapping; city, data などの t が[ɾ] となる現象),l の咽頭化 (pharyngealization; feel, help などの l が暗い [ɫ] となる現象),子音の脱落(attem(p)t, exac(t)ly, mos(t) people など)といった音韻過程を取り上げ,いずれも音節末の子音が関わっており,その音節を開音節に近づける方向で生じているのではないかと述べている.以下,その解説を引用しよう (70) .

弾音化は,阻害音の /t/ を,より母音的な共鳴音に変える現象であり,これは一種の母音化 (vocalization) と考えられる.非常に早い話し方では,better [bɛ́r] のように,弾音化された /t/ が脱落することもある.また,/l/ の咽頭化では,舌全体を後ろに引く動作が加えられるが,これは本質的に母音的な動作であり,/l/ は日本語の「オ」のような母音に近づく.実際,feel [fíːjo] のように,/l/ が完全に母音になることもある.したがって,/l/ の咽頭化も,共鳴音の /l/ をさらに母音に近づける一種の母音化と考えられる.子音の脱落は,母音化ではないが,閉音節における音節末の子音連鎖を単純化する現象である.

このように,三つの現象は,いずれも,音節末の子音を母音化したり,脱落させることによって,最後が母音で終わる開音節に近づけようとしている現象であり,機能的には共通していることがわかる.〔中略〕本質的に開音節を志向する英語は,さまざまな音声現象を引き起こしながら,閉音節を開音節に近づけようとしていると考えられる.

これは音韻変化の方向性が音節構造のあり方と関連しているという説だが,その音節構造のあり方それ自身は,強勢やリズムといった音律特性によって決定されているともいわれる.これは音変化に関する壮大な仮説である.「#3387. なぜ英語音韻史には母音変化が多いのか?」 ([2018-08-05-1]),「#3466. 古英語は母音の音量を,中英語以降は母音の音質を重視した」 ([2018-10-23-1]) を参照.

・ 安藤 貞雄・澤田 治美 『英語学入門』 開拓社,2001年.

2019-05-29 Wed

■ #3684. l と r はやっぱり近い音 [phonetics][phonology][dissimilation][l][r][japanese]

日本語母語話者は英語その他の言語で区別される音素 /l/ と /r/ の区別が苦手である.日本語では異なる音素ではなく,あくまでラ行子音音素 /r/ の2つの異音という位置づけであるから,無理もない.英語を学ぶ以上,発音し分け,聴解し分ける一定の必要があることは認めるが,区別の苦手そのものを無条件に咎められるとすれば,それは心外である.生得的な苦手とはいわずとも準生得的な苦手だからである.どうしようもない.日本語母語話者が両音の区別が苦手なのは,音声学的な英語耳ができていないからというよりも,あくまで音韻論的な英語耳ができていないからというべきであり,能力の問題というよりは構造の問題として理解する必要がある.

しかし,一方で音声学的な観点からいっても,l と r は,やはり近い音であることは事実である.このことはもっと強調されるべきだろう.ともに流音 (liquid) と称され,聴覚的には母音に近い,流れるような子音と位置づけられる.調音的にいえば l と r が異なるのは確かだが,特に r でくくられる音素の実際的な調音は実に様々である(「#2198. ヨーロッパ諸語の様々な r」 ([2015-05-04-1]) を参照).そのなかには [l] と紙一重というべき r の調音もあるだろう.実際,日本語母語話者でも,ラ行子音を伝統的な歯茎弾き音 [ɾ] としてでなく,歯茎側音 [l] として発音する話者もいる.l と r は,調音的にも聴覚的にもやはり類似した音なのである.

実は,/l/ と /r/ を区別すべき異なる音素と標榜してきた英語においても,歴史的には両音が交替しているような現象,あるいは両者がパラレルに発達しているような現象がみられる.よく知られている例としては,同根に遡る pilgrim (巡礼者)と peregrine (外国の)の l と r の対立である.語源的には後者の r が正統であり,前者の l は,単語内に2つ r があることを嫌っての異化 (dissimilation) とされる.同様に,フランス語 marbre を英語が借用して marble としたのも異化の作用とされる.異化とは,簡単にいえば「同じ」発音の連続を嫌って「類似した」発音に切り替えるということである.

したがって,上記のようなペアから,英語でも l と r は確かに「同じ」音ではないが,少なくとも「類似した」音であることが例証される.英語の文脈ですら,l と r は歴史的にやはり近かったし,今でも近い.

関連して,以下の記事も参照.

・ 「#72. /r/ と /l/ は間違えて当然!?」 ([2009-07-09-1])

・ 「#1618. 英語の /l/ と /r/」 ([2013-10-01-1])

・ 「#1817. 英語の /l/ と /r/ (2)」 ([2014-04-18-1])

・ 「#1818. 日本語の /r/」 ([2014-04-19-1])

・ 「#1597. star と stella」 ([2013-09-10-1])

・ 「#1614. 英語 title に対してフランス語 titre であるのはなぜか?」 ([2013-09-27-1])

2017-07-30 Sun

■ #3016. colonel の綴字と発音 [spelling][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap][dissimilation][silent_letter][folk_etymology][l][r]

(陸軍)大佐を意味する colonel は,この綴字で /ˈkəːnəl/ と発音される.別の単語 kernel (核心)と同じ発音である.l が黙字 (silent_letter) であるばかりか,その前後の母音字も,発音との対応があるのかないのかわからないほどに不規則である.これはなぜだろうか.

この単語の英語での初出は1548年のことであり,そのときの綴字は coronell だった.l ではなく r が現われていたのである.これは対応するフランス語からの借用語で,そちらで coronnel, coronel, couronnel などと綴られていたものが,およそそのまま英語に入ってきたことになる.このフランス単語自体はイタリア語からの借用で,イタリア語では colonnello, colonello のように綴られていた.つまり,イタリア語からフランス語へ渡ったときに,最初の流音が元来の l から r へすり替えられたのである.これはロマンス諸語ではよくある異化 (dissimilation) の作用の結果である (cf. Sp. coronel) .語中に l 音が2度現われることを嫌っての音変化だ(英語に関する類例は「#72. /r/ と /l/ は間違えて当然!?」 ([2009-07-09-1]),「#1597. star と stella」 ([2013-09-10-1]),「#1614. 英語 title に対してフランス語 titre であるのはなぜか?」 ([2013-09-27-1]) を参照).

さらに語源を遡ればラテン語 columnam (円柱)に行き着き,「兵士たちの柱(リーダー)」ほどの意味で用いられるようになった.フランス語で変化した coronnel の綴字についていえば,民間語源 (folk_etymology) により corona, couronne "crown" と関係づけられて保たれた.しかし,フランス語でも16世紀後半には l が綴字に戻され,colonnel として現在に至る.

英語では,当初の綴字に基づき l ではなく r をもつ発音がその後も用いられ続けたが,綴字に関しては早くも16世紀後半に元来の綴字を参照して l が戻されることになった.フランス語における l の復活も同時に参照したものと思われる.18世紀前半までは古い coronel も存続していたが,徐々に消えていき現在の colonel が唯一の綴字となった.発音は古いものに据えおかれ,綴字だけが変化したがゆえに,現在にまで続く綴字と発音のギャップが生じてしまったというわけだ.

しかし,実際の経緯は,上の段落で述べたほど単純ではなかったようだ.綴字に l が戻されたのに呼応して発音でも l が戻されたと確認される例はあり,/ˌkɔləˈnɛl/ などの発音が19世紀初めまで用いられていたという.発音される音節数についても通時的に変化がみられ,本来は3音節語だったが17世紀半ばより2音節語として発音される例が現われ,19世紀の入り口までにはそれが一般化しつつあった.

<colonel> = /ˈkəːnəl/ は,綴字と発音の関係が複雑な歴史を経て,結果的に不規則に固まってきた数々の事例の1つである.

2016-10-20 Thu

■ #2733. hoarse の r [phonetics][etymology][metathesis][r]

現代英語の hoarse (しゃがれ声の)には r が含まれているが,古英語での形は hās であり,r はなかった.主要な語源辞典によると,この r は中英語期における挿入であるという.意味的に緩く関連する中英語 harsk (harsh, coarse) などからの類推だろうとされている.

ただし,この r の起源は,もっと古いところにある可能性もある.ゲルマン祖語では *χais(r)az, *χairsaz が再建されており,もともと r が s の前後に想定されている(前後しているのは音位転換 (metathesis) の関与によるものと考えられる).実際に,ゲルマン諸語で文証される形態は,(M)HG heiser, MDu heersch, ON háss (< *hārs < *hairsaR) など,r を含んでいるか,少なくとも前段階で r が存在していたことを示唆している.

一方,古英語と同様に r を欠く形態を示す言語も少なくない.OFr hās, OS & MLG hēs, OHG heis などである.どうやら,時代にもよるが,英語にかぎらず複数の言語変種において,r の有無は揺れを示していたようだ.とすると,古英語で r を含む形態が文証されず,中英語になって初めて文献上に現われたからといって,古英語で r 形がまったく使われていなかったとは言い切れなくなる.

中英語では,hoos, hos, hors などが共存しており,実際この3つの綴字は Piers Plowman, B. xvii. 324 の異写本間に現われる.異綴字については,MED の hōs (adj.) も参照.

r の挿入ではなく r の消失という過程についていえば,英語史上,ときどき観察される.例えば,「#452. イングランド英語の諸方言における r」 ([2010-07-23-1]),「#2368. 古英語 sprecen からの r の消失」 ([2015-10-21-1]) の事例のほか,arse の r が19世紀に脱落して ass となったケースもある.しかし,今回のような r の挿入(と見えるような)例は珍しいといってよいだろう(だが,「#500. intrusive r」 ([2010-09-09-1]),「#2026. intrusive r (2)」 ([2014-11-13-1]) を参照).

2014-04-19 Sat

■ #1818. 日本語の /r/ [phonetics][consonant][japanese][phoneme][r][l]

「#1618. 英語の /l/ と /r/」 ([2013-10-01-1]) および昨日の記事「#1817. 英語の /l/ と /r/ (2)」 ([2014-04-18-1]) に引き続き,/r/ の話題.今回は日本語の /r/ の音声的実現についてである.

日本語のラ行の子音 /r/ は,典型的には,有声歯茎はじき音 [ɾ] として実現される.特に「あられ」のように,母音に挟まれた環境ではこれが普通である.この音は,BrE の merry や AmE の letter の第2子音として典型的に現れる音でもある.調音音声学的には,この音は有声歯茎閉鎖音 /d/ にかなり近いが,[ɾ] では舌尖と歯茎による閉鎖が弱く,その時間も短いという特徴がある.「ライオン」などの語頭や「アッラー」などの促音の後では接触が強くなり,/d/ にさらに近づくが,閉鎖の開放は弱めである.

意外と知られてないことだが,日本語母語話者の個人によっては,有声側面接近音 [l] に近い子音がラ行子音として用いられている.語頭や撥音の後で現われることが多いが,母音間でも側音に近くなる人もいる.ぴったりの音声標記はないが,有声そり舌破裂音 [ɖ] や 有声歯茎側面はじき音 [ɺ] や(接触が長い場合の)舌尖による有声歯茎側面接近音 [l̺] にも近いので,これらで代用する方法もある.有声歯茎側面はじき音 [ɺ] は,いわば [l] をはじき音化したものだが,タンザニアのチャガ語などで聞かれる子音である.

ほかにも「べらんめえ口調」に典型的とされる有声歯茎ふるえ音 [r] が,日本語 /r/ の自由異音として現れることがある.

以上,斉藤 (91) と佐藤 (43) を参照した.

・ 斉藤 純男 『日本語音声学入門』改訂版 三省堂,2013年.

・ 佐藤 武義(編著) 『展望 現代の日本語』 白帝社,1996年.

2014-04-18 Fri

■ #1817. 英語の /l/ と /r/ (2) [phonetics][consonant][rp][dialect][phoneme][r][l]

英語の /l/ と /r/ については,「#72. /r/ と /l/ は間違えて当然!?」 ([2009-07-09-1]),「#1597. star と stella」 ([2013-09-10-1]),「#1614. 英語 title に対してフランス語 titre であるのはなぜか?」 ([2013-09-27-1]) などで扱ってきた.とりわけ調音について「#1618. 英語の /l/ と /r/」 ([2013-10-01-1]) で概要を記したが,今回は一部重複するものの,それに補足する内容の記事を Crystal (245) に依拠して書く.

前の記事でも見たように,英語の音素 /l/ は,様々な音声として実現される.[l] の基本的な調音は,舌先を歯茎に接し,舌の側面から呼気を抜けさせるものだが,舌のとる形に応じて大きく2種類が区別される.それぞれ "clear l" と "dark l" と呼ばれる.前者 [l] は,前舌が硬口蓋に向かって上がるもので,前母音の響きをもち,RP では母音や [j] の前位置で起こる (ex. leap) .後者 [ɫ] は,後舌が軟口蓋に向かって上がるもので,後母音の響きをもち,RP ではそれ以外の位置で起こる (ex. pool) .ただし,clear l と dark l の分布は,諸変種において様々であり,例えば,Irish の一部であらゆる位置で clear l が聞かれたり,Scots や AmE の多くであらゆる位置で dark l が聞かれる.また,please, sleep のような無声子音の後位置では無声化した [l] が用いられる.そのほか,bottle のように音節主音的な l では,先行する [t] の側面破裂を伴う.Cockney 方言や一部 RP ですら,peel などの dark l が母音化し,[piːo] などとなる.

英語の音素 /r/ は,おそらく変種による差や個人差が最も多い子音だろう.最も普通には有声歯茎接近音 [ɹ] として実現される.d に後続する場合には,舌先が歯茎に限りなく接近し,摩擦音化が生じる (ex. drive) .母音に挟まれた位置やいくつかの子音の後位置で,日本語の典型的なラ行の子音と同じような有声歯茎はじき音 [ɾ] となる (ex. very, sorry, three) .気息を伴う [ph, th, kh] の後位置では無声摩擦音となる (ex. pry, try, cry) .

変種による異音としては,最も有名なのが有声そり舌接近音の [ɻ] で,先行する母音の音色を帯びる.General American に典型的だが,ほかにもイングランド南西部や東南アジアの変種でも聞かれる.有声歯茎ふるえ音の [r] は,Scots や Welsh の一部で聞かれるが,その他の変種でも格調高い発音において現れることがある.そのほか,フランス語やドイツ語で一般的に聞かれる有声口蓋垂摩擦音 [ʁ] あるいは有声口蓋垂ふるえ音 [ʀ] が,イングランド北東方言や一部スコットランド方言でも聞かれ,"Northumbrian burr" と呼ばれることがある(「#1055. uvular r の言語境界を越える拡大」 ([2012-03-17-1]) を参照).最後に,19世紀前半のイングランドで,red を [wed] と発音するように /r/ を [w] で代用することがはやったことを付け加えておこう.

なお,音素としては /r/ ではないが,AmE で matter の t は有声歯茎はじき音 [ɾ] として実現されることが多く,party の t は有声そり舌はじき音 [ɽ] で発音される.

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2013-10-01 Tue

■ #1618. 英語の /l/ と /r/ [phonetics][consonant][spectrogram][l][r]

「#72. /r/ と /l/ は間違えて当然!?」 ([2009-07-09-1]),「#1597. star と stella」 ([2013-09-10-1]),「#1614. 英語 title に対してフランス語 titre であるのはなぜか?」 ([2013-09-27-1]) の記事で,/l/ と /r/ の交替する事例を見てきた.日本語母語話者は,英語学習上,両音の識別が大事であることをよく知っているので,この種の話題に関心をもちやすい.だが,両音が似ていることは知っているが,具体的にはどのように似ているのだろうか.今回は,英語の /l/ と /r/, およびその異音に関する音声学的な事実を紹介したい.以下,『大修館英語学事典』 (325--28) の両音についての記述を要約する.

英語の側音 /l/ は舌先を歯茎につけて調音するが,音節内での位置に応じて2つの異音が区別される.母音および /j/ の前では前舌部が硬口蓋に向かって上げられ,前母音に似た響きをもつ clear l が発せられる.休止と子音の前では,後舌部が軟口蓋に向かって上げられ,後母音に似た響きをもつ dark l が発せられる./l/ は原則として有声音だが,気息を伴う /ph, kh/ に後続する場合には無声化する.音響学的にいえば,/l/ は非常に母音的であり,一般的なな子音とは異なり明白なフォルマントを示す.第1フォルマント (F1) と第2フォルマント (F2) が,clear l では前母音に特徴的な領域に現われ,dark l では後母音に特徴的な領域に現われる.

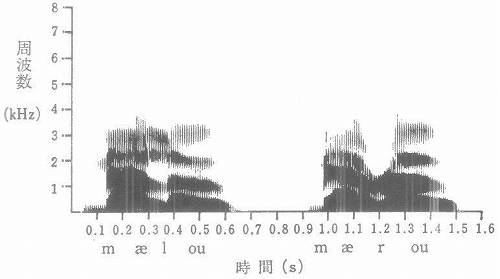

一方,/r/ は,音声環境や応じて,また話者や使用域に応じて,いくつかある異音のいずれかとして実現される.語頭で母音が続く位置,/d/ 以外の有声音に続く位置では,接近音として発音される./d/ に後続する場合には有声摩擦音となる.気息を伴う /ph, th, kh/ に後続する場合には無声摩擦音となる.母音間,あるいは /θ, ð/ や /b, g/ の後位置で,ときに弾音が用いられる.また,格調高い詩の朗読などに顫動音が用いられることもある.音響学的には,/r/ は側音 /l/ と同様,非常に母音的である./r/ と /l/ の音響学的な差は,主として F3 が引き起こすフォルマント推移に見られる.Fry, D. B. (The Physics of Speech. Cambridge: CUP, 1979) による「l と r のスペクトログラム」を,『大修館英語学事典』 (327) より再掲しよう.

それぞれ mallow と marrow の発音をスペクトログラフにかけた結果である./l/ では F3 は前後の母音の F3 とほぼ同じ領域に現れるのに対し,/r/ では F3 が深い谷を形成する.この F3 の振る舞いの差異は,前後の母音から独立して保持される.英語の /l/ と /r/ を聞き分けるのに困難を感じる日本語母語話者は,なかんずく両音における F3 の変動に対して感度が低いということになろうか.

・ 松浪 有,池上 嘉彦,今井 邦彦(編) 『大修館英語学事典』 大修館書店,1983年.

2009-07-09 Thu

■ #72. /r/ と /l/ は間違えて当然!? [consonant][phonetics][dissimilation][r][l]

日本人の苦手とする発音のペアの代表選手として [r] と [l] がある.rice と lice が同じ発音になったり,I love you が I rub you になったりという報告が絶えない.そもそも,日本語には,両者に音素としての区別がないのだから,間違えても仕方がないともいえる.「仕方ない!」と開き直ってもよい理由を二つ挙げてみよう.

一つ目は,そもそも [r] と [l] は音声学的に似ている音である.決して日本人の耳や口が無能なわけではない,音として間違いなく似ているのだ.この二音は「流音」と呼ばれ,ともに舌先と歯茎を用いて調音される.前後の音と合一して,母音のような音色に化ける点でも似ている.これくらい似ているのだから,間違えても当然,と開き直ることができる.

二つ目は,[r] と [l] を使い分けている話者,例えば英語の母語話者ですら,両者を代替することがあった.一つの語のなかに [r] が二度も出てくると,口の滑らかな話者ですら舌を噛みそうになる.その場合には,ちょっと舌の位置をずらしてやるほうが,かえって発音しやすいということもありうる.そんなとき,一方の [r] を [l] で発音してはどうだろうか,あるいはその逆はどうだろうか,などという便法が現れた.発音の都合などによって,もともと同音だった二つの音が,あえて異なる音として発音されるようになることを「異化(作用)」 ( dissimilation ) という.

異化の具体例を見てみよう.pilgrim 「巡礼者」は,<l> と <r> を含んでいるが,語源はラテン語の peregrīnum 「外国人」である.一つ目の <r> が異化を起こして <l> となり,それが英語に入った.関連語の peregrine 「遍歴中の」は異化を経ていず,いまだに二つの <r> を保っている.

同様に marble 「大理石」も,ラテン語では marmor と <r> が二つあった.13世紀末に英語に入ってきたときには <r> が二つの綴りだったようだが,二つ目の <r> が <l> へと異化した綴りも早くから行われたようである.(二つ目の <m> が <b> へ変化したのは同化(作用)によるが,説明省略.)

上で示したように,[r] と [l] は,音声的に近いだけでなく,ふだん使い分けをしている話者ですら,異化作用によって両音を交替させ得たほどに密接な関係なのである.

これで,もう自信をもって /r/ と /l/ を間違えられる!?

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow