2018-12-31 Mon

■ #3535. 「ざんねんな言語」という見方もあってよい [language_change][evolution][biology]

今泉 忠明 (監修)『「おもしろい!進化のふしぎ ざんねんないきもの事典』(高橋書店,2016年)などの,ちょっと間抜けな生物を扱った本が受けているようだ.最近,宣伝が出ていて気になったのが,芝原 暁彦(監修)・土屋 健(著)『おしい!ざんねん!!会いたかった!!!あぁ,愛しき古生物たち --- 無念にも滅びてしまった彼ら ---』(笠倉出版社,2018年)である.

うならせるほどの奇妙な形態のオパビニア,背中の帆の役割が今もってはっきりしないディメトロドン,宇宙人さながらのマルレラなど,どうしてこんな風に進化したのだろうと想像すると興味がつきない.120種類の古生物が,愛らしいイラストと笑えるコメントをもって紹介されている.

サイエンスライターの著者が「おわりに」 (pp. 156--67) で次のように述べているのが目を引いた.

そもそも「進化」とは,どのようなものなのでしょうか?

簡単に言えば,それはこういうものです.

「変化が世代を超えて受け継がれていくこと」

もっと簡単に言えば,「進化とは変化」です.そこにはポジティブな意味も,ネガティブな意味もありません.ただ単純な「変化」なのです.

さまざまな変化が受け継がれることで,生命は多様化していき,「ちょっ!なんで,こんな生き物になったの!」とも思える愛すべき生物をたくさん生み出してきたのです.

この文章は,「生物」を「言語」に変えても,ほぼそのまま理解することができる.

そもそも「(言語の)進化」とは,どのようなものなのでしょうか?

簡単に言えば,それはこういうものです.

「変化が世代を超えて受け継がれていくこと」

もっと簡単に言えば,「進化とは変化」です.そこにはポジティブな意味も,ネガティブな意味もありません.ただ単純な「変化」なのです.

さまざまな変化が受け継がれることで,言語は多様化していき,「ちょっ!なんで,こんな言葉になったの!」とも思える愛すべき言語をたくさん生み出してきたのです.

「変化が世代を超えて受け継がれていく」という部分については,生成文法の子供基盤仮説の立場からは反論や修正意見が出されるかもしれないが,緩く解釈すれば,このまま理解できる.言語変化は価値観を伴わないただの変化であり,その結果として多種多様な,ときに驚異的な特徴をもつ愛すべき諸言語が生まれてきたのである.

「ざんねんな言語」と名指ししたら,その話者に怒られそうだが,この「ざんねんな」は生物の場合と同じように相対主義を前提としての愛情と敬意のこもった修飾語であり,むしろ賛辞だと信じている.日本語も英語も,いろいろと「ざんねんな」部分はあるのだろうが,そこがまた愛しいのだろう.言語の「ざんねん」本もいろいろ出てくるとおもしろそうだなあと夢想する.

言語変化の価値中立性については「#1382. 「言語変化はただ変化である」」 ([2013-02-07-1]),「#2525. 「言語は変化する,ただそれだけ」」 ([2016-03-26-1]),「#2544. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方 (3)」 ([2016-04-14-1]),「#3354. 「言語変化はオフィスの整理である」」 ([2018-07-03-1]),「#3529. 言語は進歩しているのか,堕落しているのか?」 ([2018-12-25-1]) を参照.

・ 芝原 暁彦(監修)・土屋 健(著)『おしい!ざんねん!!会いたかった!!!あぁ,愛しき古生物たち --- 無念にも滅びてしまった彼ら ---』(笠倉出版社,2018年)

2018-02-16 Fri

■ #3217. ドーキンスと言語変化論 (3) [evolution][biology][language_change][semantic_change][bleaching][meme][lexicology]

この2日間の記事 ([2018-02-14-1], [2018-02-15-1]) に続き,ドーキンスの『盲目の時計職人』より,生物進化と言語変化の類似点や相違点について考える.同著には,時間とともに強意語から強意が失われていき,それを埋め合わせる新たな強意語が生まれる現象,すなわち「強意逓減の法則」と呼ぶべき話題を取りあげている箇所がある (349--50) .「花形役者」を意味する英単語 star にまつわる強意逓減に触れている.

〔言語には〕純粋に抽象的で価値観に縛られない意味あいで前進的な,進化のような傾向を探り当てることができる.そして,意味のエスカレーションというかたちで(あるいは別の角度からそれを見れば,退化ということになる)正のフィードバックの証拠が見いだされさえするだろう.たとえば,「スター」という単語は,まったく類まれな名声を得た映画俳優を意味するものとして使われていた.それからその単語は,ある映画で主要登場人物の一人を演じるくいらいの普通の俳優を意味するように退化した.したがって,類まれな名声というもとの意味を取り戻すために,その単語は「スーパースター」にエスカレートしなければならなかった.そのうち映画スタジオの宣伝が「スーパースター」という単語をみんなの聞いたこともないような俳優にまで使いだしたので,「メガスター」へのさらなるエスカレーションがあった.さていまでは,多くの売出し中の「メガスター」がいるが,少なくとも私がこれまで聞いたこともない人物なので,たぶんそろそろ次のエスカレーションがあるだろう.われわれはもうじき「ハイパースター」の噂を聞くことになるのだろうか? それと似たような正のフィードバックは,「シェフ」という単語の価値をおとしめてしまった.むろん,この単語はフランス語のシェフ・ド・キュイジーヌから来ており,厨房のチーフあるいは長を意味している.これはオックスフォード辞典に載っている意味である.つまり定義上は厨房あたり一人のシェフしかいないはずだ.ところが,おそらく対面を保つためだろう,通常の(男の)コックが,いやかけだしのハンバーガー番でさえもが,自分たちのことを「シェフ」と呼び出した.その結果,いまでは「シェフ長」なる同義反復的な言いまわしがしばしば聞かれるようになっている.

ドーキンスは,ここで「スター」や「シェフ」のもともとの意味をミーム (meme) としてとらえているのかもしれない(関連して,「#3188. ミームとしての言語 (1)」 ([2018-01-18-1]),「#3189. ミームとしての言語 (2)」 ([2018-01-19-1])).いずれにせよ,変化の方向性に価値観を含めないという点で,ドーキンスは徹頭徹尾ダーウィニストである.

強意の逓減に関する話題としては,「#992. 強意語と「限界効用逓減の法則」」 ([2012-01-14-1]) や「#1219. 強意語はなぜ種類が豊富か」 ([2012-08-28-1]),「#2190. 原義の弱まった強意語」 ([2015-04-26-1]) などを参照されたい.

・ ドーキンス,リチャード(著),中嶋 康裕・遠藤 彰・遠藤 知二・疋田 努(訳),日高 敏隆(監修) 『盲目の時計職人 自然淘汰は偶然か?』 早川書房,2004年.

2018-02-15 Thu

■ #3216. ドーキンスと言語変化論 (2) [glottochronology][evolution][biology][language_change][comparative_linguistics][history_of_linguistics][speed_of_change][statistics]

昨日の記事 ([2018-02-14-1]) に引き続き,ドーキンスの『盲目の時計職人』で言語について言及している箇所に注目する.今回は,ドーキンスが,言語の分岐と分類について,生物の場合との異同を指摘しながら論じている部分を取りあげよう (348--49) .

言語は何らかの傾向を示し,分岐し,そして分岐してから何世紀か経つにつれて,だんだんと相互に理解できなくなってしまうので,あきらかに進化すると言える.太平洋に浮かぶ多くの島々は,言語進化の研究のための格好の材料を提供している.異なる島の言語はあきらかに似通っており,島のあいだで違っている単語の数によってそれらがどれだけ違っているかを正確に測ることができよう.この物差しは,〔中略〕分子分類学の物差しとたいへんよく似ている.分岐した単語の数で測られる言語間の違いは,マイル数で測られる島間の距離に対してグラフ上のプロットされうる.グラフ上にプロットされた点はある曲線を描き,その曲線が数学的にどんな形をしているかによって,島から島へ(単語)が拡散していく速度について何ごとかがわかるはずだ.単語はカヌーによって移動し,当の島と島とがどの程度離れているかによってそれに比例した間隔で島に跳び移っていくだろう.一つの島のなかでは,遺伝子がときおり突然変異を起こすのとほとんと同じようにして,単語は一定の速度で変化する.もしある島が完全に隔離されていれば,その島の言語は時間が経つにつれて何らかの進化的な変化を示し,したがって他の島の言語からなにがしか分岐していくだろう.近くにある島どうしは,遠くにある島どうしに比べて,カヌーによる単語の交流速度があきらかに速い.またそれらの島の言語は,遠く離れた島の言語よりも新しい共通の祖先をもっている.こうした現象は,あちこちの島のあいだで観察される類似性のパターンを説明するものであり,もとはと言えばチャールズ・ダーウィンにインスピレーションを与えた,ガラパゴス諸島の異なった島にいるフィンチに関する事実と密接なアナロジーが成り立つ.ちょうど単語がカヌーによって島から島へ跳び移っていくように,遺伝子は鳥の体によって島から島へ跳び移っていく.

実際,太平洋の島々の諸言語間の関係を探るのに,統計的な手法を用いる研究は盛んである.太平洋から離れて印欧語族の研究を覗いても,ときに数学的な手法が適用されてきた(「#1129. 印欧祖語の分岐は紀元前5800--7800年?」 ([2012-05-30-1]) を参照).Swadesh による言語年代学も,おおいに批判を受けてきたものの,その洞察の魅力は完全には失われていないように見受けられる(「#1128. glottochronology」 ([2012-05-29-1]) や glottochronology の各記事を参照).近年のコーパス言語学の発展やコンピュータの計算力の向上により,語彙統計学 (lexicostatistics) という分野も育ってきている.生物学の方法論を言語学にも応用するというドーキンスの発想は,素直でもあるし,実際にいくつかの方法で応用されてきてもいるのである.

関連して,もう1箇所,ドーキンスが同著内で言語の分岐を生物の分岐になぞらえている箇所がある.しかしそこでは,言語は分岐するだけではなく混合することもあるという点で,生物と著しく相違すると指摘している (412) .

言語は分岐するだけではなく,混じり合ってしまうこともある.英語は,はるか以前に分岐したゲルマン語とロマンス語の雑種であり,したがってどのような階層的な入れ子の図式にもきっちり収まってくれない.英語を囲む輪はどこかで交差したり,部分的に重複したりすることがわかるだろう.生物学的分類の輪の方は,絶対にそのように交差したりしない.主のレベル以上の生物進化はつねに分岐する一方だからである.

生物には混合はあり得ないという主張だが,生物進化において,もともと原核細胞だったミトコンドリアや葉緑体が共生化して真核細胞が生じたとする共生説が唱えられていることに注意しておきたい.これは諸言語の混合に比較される現象かもしれない.

・ ドーキンス,リチャード(著),中嶋 康裕・遠藤 彰・遠藤 知二・疋田 努(訳),日高 敏隆(監修) 『盲目の時計職人 自然淘汰は偶然か?』 早川書房,2004年.

2018-02-14 Wed

■ #3215. ドーキンスと言語変化論 (1) [teleology][evolution][biology][language_change]

ドーキンスの名著『盲目の時計職人』(原題 The Blind Watchmaker (1986))は,(ネオ)ダーウィニズムの最右翼の書である.言語変化論にとって生物の進化と言語の進化・変化の比喩がどこまで有効かという問題は決定的な重要性をもっており,私も興味津々なのだが,比喩の有用性と限界の境目を見定めるのは難しい.

ドーキンスの上掲書を通読するかぎり,言語に直接・間接に応用可能な箇所を指摘すれば,3点あるように思われる.(1) 非目的論 (teleology) の原理,(2) 言語の分岐と分類,(3) 意味の漂白化と語彙的充填だ.今回は (1) の非目的論について考えてみたい.

ドーキンス (24--25) は,生物進化の無目的性,すなわち「盲目の時計職人」性について次のように明言している.言語の進化・変化についても,そのまま当てはまると考える.

自然界の唯一の時計職人は,きわめて特別なはたらき方ではあるものの,盲目の物理的な諸力なのだ.本物の時計職人の方は先の見通しをもっている.心の内なる眼で将来の目的を見すえて歯車やバネをデザインし,それらを相互にどう組み合わせるかを思い描く.ところが,あらゆる生命がなぜ存在するか,それがなぜ見かけ上目的をもっているように見えるかを説明するものとして,ダーウィンが発見しいまや周知の自然淘汰は,盲目の,意識をもたない自動的過程であり,何の目的ももっていないのだ.自然淘汰には心もなければ心の内なる眼もありはしない.将来計画もなければ,視野も,見通しも,展望も何もない.もし自然淘汰が自然界の時計職人の役割を演じていると言ってよいなら,それは盲目の時計職人なのだ.

言語変化も,その言語の話者が担っているには違いないが,その話者の演じるところはあくまで無目的の「盲目の時計職人」であると考えられる.確かに,話者はその時々の最善のコミュニケーションのために思考し,言葉を選び,それを実際に発しているかもしれない.それはその通りなのだが,後にそれが帰結するかもしれない言語変化について,すでにその段階で話者が何かを目論んでいるとは思えない.言語変化はそのように予定されているものではなく,その意味において無目的であり,盲目なのである.本当は,個々の話者は「盲目の時計職人」すら演じているわけではなく,結果的に「時計職人」ぽく,しかも「盲目の時計職人」ぽく見えるにすぎないのだろう.

言語変化における目的論に関わる諸問題については,teleology の各記事を参照されたい.

・ ドーキンス,リチャード(著),中嶋 康裕・遠藤 彰・遠藤 知二・疋田 努(訳),日高 敏隆(監修) 『盲目の時計職人 自然淘汰は偶然か?』 早川書房,2004年.

2018-02-09 Fri

■ #3210. 時代が下るにつれ,書き言葉の記録から当時の日常的な話し言葉を取り出すことは難しくなるか否か [standardisation][evolution][writing][methodology][genbunicchi]

標題はふと抱いた疑問なのだが,歴史言語学の evidence を巡る問題として考えてみるとおもしろいのではないか.念頭に置いているのは英語であり,すべての言語に当てはまるわけではないだろうが,似たようなことは少なからぬ言語の研究において当てはまるのではないか.

通常,現存する最初期の文献の多くは韻文であることが多い.たいてい韻文とは,書き記されたその時代においてすら古風とされる文学語であり,当時の話し言葉をそのまま反映しているものと解釈することはできない.しかし,時代が下るにつれ,とりわけ近代にかけて西洋のように言文一致風の散文が発達した場合には,つまり書き言葉と話し言葉の差が比較的縮まってくるような文化にあっては,書き記された記録から話し言葉の実体を取り出すことが,もっと容易になってくる.全体として,時間とともに,話し言葉の evidence へのアクセスが保証されるようになってきたようにみえる.

しかし,一方で近代にかけて,標準語というものが発達してきた事実がある.書き手は,発達してきた散文において,自らの母語や母方言とは言語的に隔たりのある標準語で書くことを余儀なくされる.すると,現代の研究者が目にしている彼らのものした散文は,確かに韻文と比べれば日常の話し言葉を反映している可能性が高いとはいえ,彼らの自然の母語が反映されているわけではなく,教育によって矯正された言語変種,ある種の不自然な話し言葉変種が反映されているにすぎないともいえる.その意味では,そのような証拠から彼らの「素の」日常的な話し言葉を取り出すことは難しくなっていると言えるのでないか.全体として,時間とともに,素の話し言葉の evidence へのアクセスが妨げられるようになってきたと考えられる.

さらに議論を続ければ,散文の文体としても,時代が下るにつれ pragmatic mode あるいは informal discourse から syntactic mode あるいは formal discourse へと推移する "syntacticization" の傾向を指摘する Givón のような論者もある (Schaefer 1277) .話し言葉の気取らない pragmatic/informal な性質は,syntactic/formal を指向する近現代の書き言葉とは相容れないという見方も説得力がある.

上記のプラスとマイナスを印象的に総合すると,日常的な話し言葉へのアクセシビリティは,たとえば3歩進んで2歩下がるというくらいのペースで進んできたとは言えないだろうか.通言語的にこのような一般論が語れるかどうかは怪しいかもしれないが,歴史言語学の evidence を巡る問題として一般的に論じるに値するテーマではないだろうか.

・ Schaefer, Ursula. "Interdisciplinarity and Historiography: Spoken and Written English --- Orality and Literacy." Chapter 81 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1274--88.

2017-03-10 Fri

■ #2874. 淘汰圧 [evolution][language_change][speed_of_change][functional_load][schedule_of_language_change][entropy]

進化生物学では,自然淘汰 (natural selection) と関連して淘汰圧 (selective pressure or evolutionary pressure) という概念がある.伊勢 (23) の説明を見てみよう.

自然淘汰の強さの度合いを表わすときに,淘汰圧 (selective pressure または evolutionary pressure) という言葉を使います.形質による適応度の違いが大きいとき,淘汰圧は高くなります.たとえば,環境が悪化して多くの個体が子孫を残さずに死に絶え,適応度の高いごく一部の個体だけが子孫を残して繁栄するような状況では,淘汰圧は高くなります.

淘汰圧が高いとき,進化は猛スピードで進みます.適応度は形質によって大きく異なるので,高い適応度を生む形質が自然淘汰で選ばれていき,適応度を下げる形質は急速に失われていきます.逆に,淘汰圧が低い状況では,形質が違ってもそれほど適応度に差が見られません.よって,世代を経ても形質の変化はあまり見られません.

伊勢は,例としてアルビノ化を挙げている.アルビノ化した個体はカモフラージュが苦手なので,一般に生存確率が下がる.つまり適応度を下げる形質なので,通常の淘汰圧の高い状況下では,失われていくことがほとんどである.ところが,真っ暗な洞窟など,カモフラージュすることが意味をもたない環境においては,淘汰圧は低いため,アルビノ化した個体が適応度の点で特に劣ることにはならない.洞窟においては,アルビノ化(の有無)は重要性をもたないのである.

さて,ここで言語の話題に移ろう.言語変化を,広い意味で言語をとりまく環境の変化に適応するための自然淘汰であると捉えるのであれば,言語における淘汰圧というものを考えることは有用だろう.淘汰圧が高い状況では,ちょっとした言語項の変異でも重要性を帯び,より適応度の高い変異体が選択される可能性が高い.一方,淘汰圧が低い状況では,それなりに目立つ変異であってもさほど重要性をもたないため,特定の変異体が勝ったり負けたりというような淘汰のプロセスへ進んでいかない.

では,言語において淘汰圧の高い状態や低い環境とは何だろうか.言語体系内での圧力と言語体系外の圧力に分けて考えることができる.前者については,構造言語学的な観点から機能負担量 (functional_load),対立の効率性,体系の対称性など,様々な考え方がある.後者については,社会言語学や語用論で取り上げられる話者間の相互作用や言語接触などが,特定の言語環境を用意する要素となる.

生物における淘汰圧が進化の速度にも関係するということは,言語についても当てはまりそうである.淘汰圧が高ければ,おそらく言語変化はスピーディに進むだろう.この点に関しては,エントロピー (entropy) という,もう1つの興味深い話題も想起される.「#1810. 変異のエントロピー」 ([2014-04-11-1]),「#1811. "The later a change begins, the sharper its slope becomes."」 ([2014-04-12-1]) の議論を参照されたい.

・ 伊勢 武史 『生物進化とはなにか?』 ベレ出版,2016年.

2017-03-09 Thu

■ #2873. 生物進化に関する誤解と,その解消法の言語への応用 [evolution][language_myth][family_tree][indo-european]

「#2863. 種分化における「断続平衡説」と「系統漸進説」」 ([2017-02-27-1]) でも触れたが,近年の言語学では,進化生物学における進化 (evolution) の概念がしばしば参照される.生物の進化と言語を進化を比較すると,興味深い洞察が得られることが多い.今回は,生物進化に関して人々が典型的に抱いている誤解を紹介しながら,対応する言語進化の誤解について考えてみたい.

伊勢 (52--53) によると,生物進化について次のような誤解が蔓延しているという.進化のなかでヒトが最も上位であり,その次がサル,そしてその下にもろもろの生き物(獣や虫など)が位置づけられ,全体として序列がある,という見解である.しかし,進化生物学では,それぞれの生き物が各々の環境に適応してきたのであり,ヒトにしても,サルにしても,アリにしても,みな共通の祖先から枝分かれして,同じ時間だけ自然淘汰にさらされ,常に進化の最前線で生きてきたのだと考える.つまり,様々な種の間には,系統関係の遠近はあるにせよ,上下・優劣の差といった序列はない.

ヒトが生物界の序列の頂点に鎮座しているという誤解を解きほぐすには,系統図の描き方を少々工夫すればよい.例えば,伊勢 (54) は以下の左図よりも右図の見方のほうが啓蒙的であるとしている.

アリ ネコ ゴリラ チンパンジー ヒト │ アリ ネコ チンパンジー ヒト ゴリラ \ \ \ \ / │ \ \ \ / / \ \ \ \ / │ \ \ \ / / \ \ \ \/ │ \ \ \/ / \ \ \ / │ \ \ \ / \ \ \ / │ \ \ \ / \ \ \/ │ \ \ \/ \ \ / │ \ \ / \ \ / │ \ \ / \ \/ │ \ \/ \ / │ \ / \ / │ \ / \/ │ \/ / │ / / │ / / │ /

右図では,ヒトが「序列の頂点」の想起されやすい右端のポジションには置かれておらず,特別な存在ではないことが示される.さらに,チンパンジーが実はゴリラよりもヒトのほうに近い親戚であることが読み取りやすくなる.ヒトとそれ以外のサル(チンパンジーとゴリラ)という対立ではなく,ヒトとチンパンジーから成るグループと,ゴリラのグループとの対立である,という点が浮き彫りになるのだ.あるいは,チンパンジーにとって最も近縁の動物は何かという問い方をすれば,ゴリラではなくヒトである,というのが正しい答えであることも読み取りやすい.

一般には,ヒトの立場から見れば,チンパンジーもゴリラも同じ「サル」として下等に見える.しかし,ゴリラの目線から見れば,ヒトとチンパンジーは「自分たちから外れていった変なサル」として同類に映るだろう.チンパンジーの目線からは,ヒトもゴリラも風変わりの度合いこそ異なるが,いずれにせよ風変わりな「どうしちゃったのチンパンジー」などと見えているかもしれないのだ.

上の例は,言語に関する誤解と,その誤解の解消についても当てはめることができるのではないか.現代世界で最も国際的に有用で,広く使用されている英語という言語は,上等で偉い言語であると見なされがちである.言語系統図にしても,英語が最も重要と見なされやすい位置に描かれ,その他の言語とそれに至る進化の枝は二次的で周辺的な扱いを受けるように描かれることがある.しかし,相対化してみれば,英語も他の言語も各々に環境適応してきたという点では同格であり,いずれが上等ということはない.以下,粗っぽい図ではあるが,英語を含む諸言語の系統図,2種類を比べてみよう.

印欧祖語 独語 蘭語 フリジア語 英語 │ 印欧祖語 独語 フリジア語 英語 蘭語 \ \ \ \ / │ \ \ \ / / \ \ \ \ / │ \ \ \ / / \ \ \ \/ │ \ \ \/ / \ \ \ / │ \ \ \ / \ \ \ / │ \ \ \ / \ \ \/ │ \ \ \/ \ \ / │ \ \ / \ \ / │ \ \ / \ \/ │ \ \/ \ / │ \ / \ / │ \ / \/ │ \/ / │ / / │ / / │ /

英語を含む印欧語族の系統図については,cat:indo-european family_tree の各記事を参照.

・ 伊勢 武史 『生物進化とはなにか?』 ベレ出版,2016年.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2017-02-28 Tue

■ #2864. 分類学における系統と段階 [family_tree][anthropology][homo_sapiens][diachrony][terminology][linguistic_area][typology][methodology][world_languages][evolution]

世界の言語を分類する際の2つの基準である「系統」と「影響」は,言語どうしの関係の仕方を決定づける基準でもある.この話題については,本ブログでも以下の記事を始めとして,あちらこちらで論じてきた (see 「#369. 言語における系統と影響」 ([2010-05-01-1]),「#807. 言語系統図と生物系統図の類似点と相違点」 ([2011-07-13-1]),「#371. 系統と影響は必ずしも峻別できない」 ([2010-05-03-1]),「#1136. 異なる言語の間で類似した語がある場合」 ([2012-06-06-1]),「#1236. 木と波」 ([2012-09-14-1]),「#1930. 系統と影響を考慮に入れた西インドヨーロッパ語族の関係図」 ([2014-08-09-1])) .

系統と影響は,それぞれ通時態と共時態の関係にも通じるところがある.系統とは時間軸に沿った歴史の縦軸を指し,影響とは主に地理的な隣接関係にある横軸を指す.言語における「系統」と「影響」という視点の対立は,生物分類学でいうところの「系統」と「段階」の対立に相似する.

分岐分類学 (cladistics) では,時間軸に沿った種分化の歴史を基盤とする「系統」の視点から,種どうしの関係づけがなされる.系統としての関係が互いに近ければ,形態特徴もそれだけ似ているのは自然だろう.だが,形態特徴が似ていれば即ち系統関係が近いかといえば,必ずしもそうならない.系統としては異なるが,環境の類似性などに応じて似たような形態が発達すること(収斂進化)があり得る.このような系統とは無関係の類似を,成因的相同 (homoplasy) という.系統的な近さではなく,成因的相同に基づいて集団をくくる分類の仕方は,「段階」 (grade) による区分と呼ばれる.

ウッド (70) を参考にして,現生高等霊長類を分類する方法を取り上げよう.「系統」の視点によれば,以下のように分類される.

ヒト族 チンパンジー族 ゴリラ族 オランウータン族 \ / / / \ / / / \ / / / \/ / / \ / / \ / / \ / / \ / \ / \ / \/ \ \ \

一方,「段階」の視点によれば,以下のように「ヒト科」と「オランウータン科」の2つに分類される.

ヒト科 オランウータン科 │ ┌─────────┼───────┐ │ │ │ ヒト族 チンパンジー族 ゴリラ族 オランウータン族

「段階」の区分法は,言語学でいえば,類型論 (typology) や言語圏 (linguistic_area) に基づく分類と似ているといえる.ただし,生物においても言語においても「段階」という用語とその含意には十分に気をつけておく必要がありそうだ.というのは,それは現時点における歴史的発達の「段階」によって区分するという考え方を喚起しやすいからだ.つまり,「段階」の上下や優劣という概念を生み出しやすい.「段階」の区分法は,あくまで共時的類似性あるいは成因的相同に基づく分類である,という点に留意しておきたい.

・ バーナード・ウッド(著),馬場 悠男(訳) 『人類の進化――拡散と絶滅の歴史を探る』 丸善出版,2014年.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2017-02-27 Mon

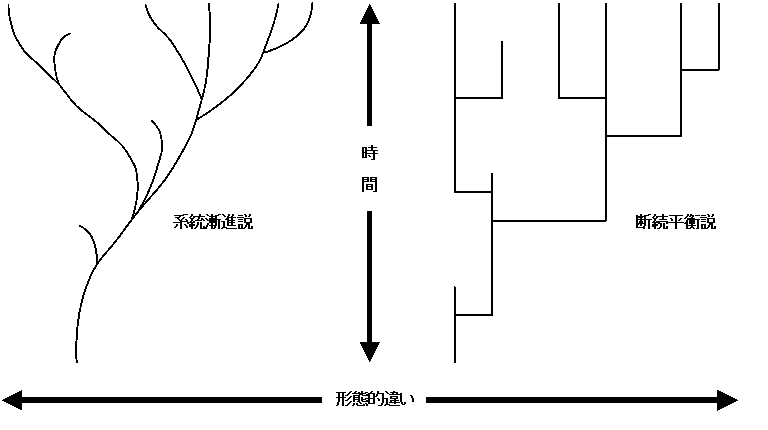

■ #2863. 種分化における「断続平衡説」と「系統漸進説」 [evolution][punctuated_equilibrium][origin_of_language][language_change][speed_of_change]

言語進化論や言語起源論は,しばしば進化生物学の仮説を参照する.言語の分化を説明するモデルとして生物の種分化に関するモデルが参考とされるが,後者では2種類の対立する仮説が立てられている.断続平衡説 (punctuated_equilibrium) と系統漸進説 (phyletic gradualism) である.バーナード・ウッドの人類進化の概説書より,種分化に関する解説を引用する (60--61).

ある研究者は,新しい種の誕生は集団全体がゆっくり変化することと考える.この解釈は「系統漸進説 (phyletic gradualism)」とよばれ,種分化は「アナゲネシス,漸進進化 (anagenesis)」によって起こると見なされる.ほかの研究者は,新しい種の誕生は地理的に隔離された一部の集団が急速に変化することと考える.この解釈は「断続平衡説 (punctuated equilibrium)」とよばれ,急速な変化と変化の間の期間には,特定の方向への変化は起こらず,無方向的な散歩(ふらつき (random walk))しか起こらないと見なされる.断続平衡説における種形成は「分岐進化 (cladogenesis)」とよばれ,種形成と種形成との間の形態的に安定した期間は停滞期 (stasis) と考える.ほぼすべての研究者は,進化における形態変化は種分化のときに起こると認識している.

これを図示すると,以下のようになる(ウッド,p. 61 を参考に).

いずれのモデルにおいても,種の誕生や分化がとりわけ盛んな時期があると想定されている.これは適応放散 (adaptative radiation) と呼ばれ,新環境が生じたときに起こることが多いとされる.

生物進化の比喩がどこまで言語進化に通用するものなのか,議論の余地はあるが,比較対照すると興味深い.関連して,「#807. 言語系統図と生物系統図の類似点と相違点」 ([2011-07-13-1]) も参照.とりわけ,言語の起源,進化,変化速度に関する断続平衡説の応用については,「#1397. 断続平衡モデル」 ([2013-02-22-1]),「#1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード」 ([2014-02-09-1]),「#1755. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード (2)」 ([2014-02-15-1]),「#2641. 言語変化の速度について再考」 ([2016-07-20-1]) を参照されたい.

・ バーナード・ウッド(著),馬場 悠男(訳) 『人類の進化――拡散と絶滅の歴史を探る』 丸善出版,2014年.

2017-02-08 Wed

■ #2844. 人類の起源と言語の起源の関係 (2) [language_family][world_languages][anthropology][family_tree][evolution][altaic][japanese][indo-european][origin_of_language]

「#2841. 人類の起源と言語の起源の関係」 ([2017-02-05-1]) 及び「#2843. Ruhlen による世界の語族」 ([2017-02-07-1]) に引き続き,世界の語族分類について.Ruhlen 自身のものではないが,著書のなかで頻繁に参照・引用して支持している Cavalli-Sforza et al. が,遺伝学,考古学,言語学の知見を総合して作り上げた関係図がある.Ruhlen (33) で "Comparison of the Genetic Tree with the Linguistic Phyla" として掲げられている図は,Cavalli-Sforza らによるマッピングから少し改変されているようだが,いずれにせよ驚くべきは,遺伝学的な分類と言語学的な分類が,完全とは言わないまでも相当程度に適合していることだ. *

言語学者の多くは,昨日の記事 ([2017-02-07-1]) で触れたように,遺伝学と言語学の成果を直接結びつけることに対して非常に大きな抵抗を感じている.両者のこのような適合は,にわかには信じられないだろう.特に分類上の大きな問題となっているアメリカ先住民の諸言語の位置づけについて,この図によれば,遺伝学と言語学が異口同音に3分類法を支持していることになり,本当だとすればセンセーショナルな結果となる.

ちなみに,ここでは日本語は朝鮮語とともにアルタイ語族に所属しており,さらにモンゴル語,チベット語,アイヌ語などとも同じアルタイ語族内で関係をもっている.また,印欧語族は,超語族 Nostratic と Eurasiatic に重複所属する語族という位置づけである.この重複所属については,ロシアの言語学者たちや Greenberg が従来から提起してきた分類から導かれる以下の構図も想起される (Ruhlen 20) .

?????? Afro-Asiatic

?????? Kartvelian

?????? Elamo-Dravidian

NOSTRATIC ─┼─ Indo-European ─┐

├─ Uralic-Yukaghir ─┤

├─ Altaic ─┤

└─ Korean ─┤

Japanese ─┼─ EURASIATIC

Ainu ─┤

Gilyak ─┤

Chukchi-Kamchatkan ─┤

Eskimo-Aleut ─┘

Cavalli-Sforza et al. や Ruhlen にとって,遺伝学と言語学の成果が完全に一致しないことは問題ではない.言語には言語交替 (language_shift) があり得るものだし,その影響は十分に軽微であり,全体のマッピングには大きく影響しないからだという.

素直に驚くべきか,短絡的と評価すべきか.

・ Ruhlen, Merritt. The Origin of Language. New York: Wiley, 1994.

・ Cavalli-Sforza, L. L, Alberto Piazza, Paolo Menozzi, and Joanna Mountain. "Reconstruction of Human Evolution: Bringing Together Genetic, Archaeological and Linguistic Data." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 85 (1988): 6002--06.

2017-02-05 Sun

■ #2841. 人類の起源と言語の起源の関係 [evolution][origin_of_language][homo_sapiens][anthropology]

連日,人類の起源や拡散についての話題を取り上げている ([2017-02-02-1], [2017-02-03-1], [2017-02-04-1]) .それは,この話題が言語の起源と拡散というもう1つの話題と関連する可能性があるからだ.人類の起源に関して単一起源説と多地域進化説が対立しているように,言語の起源についても単一起源説と多起源説が唱えられている.この2つの問題を関係づけて論じたくなるのも自然のように思われるかもしれない.

しかし,言語学の世界では,この関係づけに対する慎重論がことのほか目立つ.1つには,「#515. パリの言語学会が言語起源論を禁じた条文」 ([2010-09-24-1]) で述べたように,1866年にパリの言語学会で言語起源論が公的に禁止されて以来,この話題に対する「怯え」が学界において定着し,継承されてきたという事情がある.また,人類学や考古学が,ホモ・サピエンスの出現以前にまで遡る数十万年以上のタイムスパンを扱えるのに対して,比較言語学で遡れるのはせいぜい1万年ほどと言われるように,想定している時間の規模が大きく異なっているという事情もあるだろう (cf. 「#1313. どのくらい古い時代まで言語を遡ることができるか」 ([2012-11-30-1])) .このような事情から,人類の起源と言語の起源という2つの話題を結びつけようとすることは早計であり,原則として互いに立ち入るべきではないという学問的「謙虚さ」(あるいは「怯え」)が生じたものと思われる.

この慎重論は,確かに傾聴に値する.しかし,「#231. 言語起源論の禁止と復活」 ([2009-12-14-1]) でも触れたように,近年,人類や言語の起源を巡る関連諸分野がめざましく発展しており,従来の怯えを引きずっているかのような慎重論に物足りなさを感じる進化言語学者や類型論学者が現われてきた.その急先鋒の学者の1人が,「#1116. Nostratic を超えて Eurasian へ」 ([2012-05-17-1]) で触れた,世界諸言語の系統図をまとめ上げようとしている Ruhlen である.Ruhlen は,著書の "An End to Mythology" と題する節で,他の研究者を引用しながら次のように述べている.

Many linguists still believe that there is little correlation between linguistic and biological traits. According to Campbell (1986: 488), "repetition of the obvious seems required: there is no deterministic connection between language and gene pools or culture." However, recent work by L. L. Cavalli-Sforza et al. (1988) shows that the correlations between biological and linguistic classifications are of a most intimate nature: "Linguistic families correspond to groups of populations with very few, easily understood overlaps, and their origin can be given a time frame. Linguistic superfamilies show remarkable correspondence . . . , indicating considerable parallelism between genetic and linguistic development."

特に説得力のある説明とはなってはいないが,人類と言語の起源の関連を頭ごなしに否定するのは,その関連を初めから前提とするのと同じくらい不適切である,という主張ならば理解できる.

また,Ruhlen は,比較言語学が数千年ほどしか遡れないとする従来の常識について,"the widely held notion that the comparative method is limited to the last 5,000--8,000 years can be shown to be little more than a cherished myth of twentieth-century linguistics" (14--15) と述べていることも付け加えておこう.

・ Ruhlen, Merritt. The Origin of Language. New York: Wiley, 1994.

2017-02-04 Sat

■ #2840. 人類の脳容量の変化 [evolution][origin_of_language][homo_sapiens][anthropology][family_tree]

「#2838. 新人の登場と出アフリカ」 ([2017-02-02-1]) と「#2839. 新人の出アフリカ後のヨーロッパとアメリカへの進出」 ([2017-02-03-1]) に引き続き,人類学の話題.人類の進化を脳容量の変化という観点からたどると,興味深いことに,類人猿までの進化には相当手間取ったらしい.

ヒトに最も近いチンパンジーの脳の容量は400cc.霊長類の歴史では,ここから500ccの大台に乗るのまでに400万年という時間を要した.逆に,それ以降の進化は早い.300?200万年前のアウストラロピテクス・アフリカヌスの段階で450ccになった後,230?140万年前のホモ・ハビリスでついに550ccを記録.さらに,150?20万年前のホモ・エレクトスでは1000ccとなり,40?2万年前に生存したホモ・ネアンデルターレンシスでは1500ccにも達した.ちなみに現在まで続く新人たるホモ・サピエンスの脳容量はむしろ若干少なく,1350ccである.この進化の過程で,漸進的に顎が後退し,体毛が喪失した.

霊長類という観点から進化をたどると,およそ次のような図式となる(谷合. p. 223 を参照).

3500万年前 ─┬──────── マーモセット

│

│

│

│

2500万年前 └┬─────── ニホンザル・メガネザル

│

│

│

1800万年前 └┬────── テナガザル

│

│

1200万年前 └┬───── オランウータン

│

│

700?500万年前 ──┴┬──── ゴリラ

│

└─┬── チンパンジー

│

サヘラントロプス・チャデンシス

│

└── ヒト

その他,谷合より,脳容量の比較(231)や人類の進化系統樹(240)の図も有用. * *・ 谷合 稔 『地球・生命――138億年の進化』 SBクリエイティブ,2014年.

2017-02-03 Fri

■ #2839. 新人の出アフリカ後のヨーロッパとアメリカへの進出 [evolution][origin_of_language][homo_sapiens][anthropology]

昨日の記事「#2838. 新人の登場と出アフリカ」 ([2017-02-02-1]) に引き続き,約10万年前にアフリカを出たとされる新人が,その後いかに世界へ拡散したか,という話題.

昨日の地図を眺めると,アフリカからシナイ半島を渡ってレヴァント地方へ進出した新人のさらなる移動について疑問が生じる.彼らはまもなくアジア方面へは展開していったようだが,距離的には比較的近いはずのヨーロッパ方面への展開は数万年ほど遅れてのことである.この空白の時間は何を意味するのだろうか.ロバーツ (308--09) がある学説を紹介している.

アラビア半島やインド亜大陸から北のヨーロッパへ移動するのは,簡単なように思えるが,スティーヴン・オッペンハイマーによると,過去一〇万年にわたって,アフリカから出る北のルート(シナイ半島とレヴァント地方を通る)を砂漠が阻んでいるのと同様に,インド亜大陸とアラビア半島から地中海沿岸へ至る道もまた,イラン南部のザクロス山脈や,アラビア半島北部のシリア砂漠,ネフド砂漠といった地理的な障害によって閉ざされていた.浜辺の採集者たちが東へ進んでいく一方で,北のヨーロッパへ向かう道は遮断されていたのだ.しかし,およそ五万年前,数千年という短い間だったが,気候が暖かくなった.オッペンハイマーは,この温暖な気候のせいで,ペルシャ湾岸から地中海沿岸まで緑の通路がつながり,ヨーロッパへの扉が開かれたと論じている.

ヨーロッパへの展開を遅れさせたもう1つの要因として,そこに旧人のホモ・ネアンデルターレンシスがすでに暮らしていたという事実もあったかもしれない.新人のクロマニョン人が約4万年前にヨーロッパに到達したとき,ホモ・ネアンデルターレンシスは栄えていたのだ.このとき両人類が共生・交雑し合ったかどうか,ホモ・ネアンデルターレンシスも言語をもっていたかどうかは,人類学上の最重要問題の1つだが,とにかく彼らが出会ったことは確かなようだ.

次に,新人が3?1.2万年にアメリカ大陸へ渡ったという画期的な事件について.海面が低くベーリング海峡が地続きだった時代に,シベリアから新世界へと新人の移住が起こった.移住の波が一度だったのか,あるいはいくつかの波で起こったのかについて論争があるようだが,最近の核DNAの研究結果は,一度だったのではないかという説を支持している.これに従うと,人類のアメリカへの移動は次のように解釈される(ロバーツ,p. 431).

ベーリンジアはアジア人が通過した「陸橋」というより,アジアのさまざまな地域からの人々を受け入れた「中継地点」であり,そこで彼らの系統はいったん混ぜ合わされ,それを背負った子孫たちがアメリカ大陸に移住したということだ.そうだとすれば,アジアをアメリカ先住民の故郷と見なすのは,単純すぎるということになる.彼らの祖先はアジアだけでなく,さまざまな地域からベーリンジアにやってきた.言うなればベーリンジアがアメリカ人の故郷なのだ.

「最初のアメリカ人」は5千人程度だったが,その後アメリカでは2万年前以降に人口が膨張したとされる.こうして,南極大陸以外の地球上の大陸は,新人に満たされることになった.人類の歴史として考えると,遠い昔のことではなく,ごく最近の出来事である.

・ アリス・ロバーツ(著),野中 香方子(訳) 『人類20万年 遙かなる旅路』 文芸春秋,2013年.

2017-02-02 Thu

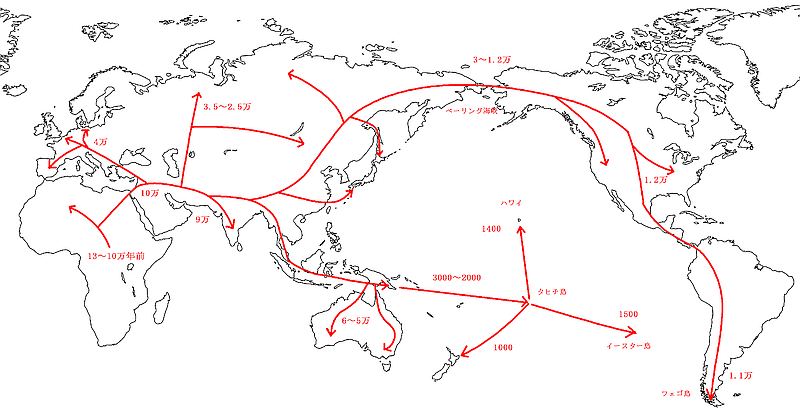

■ #2838. 新人の登場と出アフリカ [evolution][origin_of_language][homo_sapiens][anthropology][map]

新人(ホモ・サピエンス)の起源については,アフリカ単一起源説と多地域進化説がある.後者は,先行して世界に展開していたホモ・ネアンデルターレンシスなどの旧人が,各地で新人へと進化したという仮説である.一方,前者は新人はアフリカに現われたが,その後,旧人や原人が暮らす各地へ進出していったとするものである.

近年は,ミトコンドリアDNAを利用した遺伝子変異の分布の研究により,約20万年前にアフリカに現われた1人の女性「ミトコンドリア・イブ」の存在を想定したアフリカ単一起源説が優勢となっている.さらに,2003年にはエチオピアで約16万年前のものとされる人骨(ホモ・サピエンス・イダルトゥと名付けられた)が発見されており,現生人類に進化する直前の姿ではないかと言われている.

ミトコンドリア・イブの年代については諸説あり,上で述べた約20万年前というのは1つの仮説である.ミトコンドリア・イブの子孫たち,すなわち新人がアフリカを出た時期についても諸説あるが,およそ10万年前のことと考えられている.その後の世界展開については,谷合 (241) を参照して作成した以下の地図を参考までに.

ホモ・サピエンスがその初期の段階から言語をもっていたと仮定するならば,この移動の地図は,そのまま人類言語の拡散の地図となるだろう.

関連して,「#160. Ardi はまだ言語を話さないけれど」 ([2009-10-04-1]),「#751. 地球46億年のあゆみのなかでの人類と言語」 ([2011-05-18-1]),「#1544. 言語の起源と進化の年表」 ([2013-07-19-1]),「#1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード」 ([2014-02-09-1]),「#1755. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード (2)」 ([2014-02-15-1]) も参照.また,Origins of Modern Humans: Multiregional or Out of Africa? の記事も参考になる.

・ 谷合 稔 『地球・生命――138億年の進化』 SBクリエイティブ,2014年.

2017-02-01 Wed

■ #2837. 人類史と言語史の非目的論 [historiography][teleology][anthropology][evolution][language_myth]

近年,環境問題への意識の高まりから,人類史,地球史,宇宙史といった大きな規模での歴史が関心を呼んでいる.そのような広い視野の歴史からみると,人類の言語の歴史など刹那にすぎないことは,「#751. 地球46億年のあゆみのなかでの人類と言語」 ([2011-05-18-1]) や「#1544. 言語の起源と進化の年表」 ([2013-07-19-1]) でも確認した通りである.しかし,言語史も歴史の一種であるから,より大きな人類史などを参照することで,参考となること,学べることも多い.

解剖学者アリス・ロバーツの『人類20万年 遙かなる旅路』を読んだ.人類が,故郷のアフリカ大陸から世界へ拡散していった過程を「旅路」(原題は The Incredible Human Journey) と呼んでいるが,そこにはある種のロマンチックな響きが乗せられている.しかし,著者の態度は,実際にはロマンチックでもなければ,目的論的でもない.それは,次の文章からも知られる (39) .

祖先たちは何度もぎりぎりの状況をくぐり抜け,最も過酷な環境へも足を踏み入れて生きながらえてきた.その苦難に思いを馳せれば,畏怖と賞賛を感じずにはいられない.アフリカに生まれ,地球全体に住むようになるまでの人類の歩みは,たしかに畏敬の念を起こさせる物語である.

しかし,その旅を,逆境に立ち向かう英雄的な戦いのようにとらえたり,祖先たちが世界中に移住するという目的をもって旅立ったと考えたりするのは,軽率と言えるだろう.よく言われる「人類の旅」とは比喩にすぎず,祖先たちはどこかへ行こうとしたわけではなかった.「旅」や「移住」という言葉は,人類の集団が膨大な年月にわたって地球上を移動した様子を表現するのに便利ではあるが,わたしたちの祖先は積極的に新天地に進出していったわけではない.たしかに彼らは狩猟採集民で,季節に応じて移動していたが,ほとんどの期間,ある場所から他の場所へあえて移ることはなかった.人類であれ動物であれ個体数が増えれば周囲に拡散するというただそれだけのことだったのだ.

数百万年におよぶ人類の拡散を,抽象的な意味において「旅」や「移住」と呼ぶことはできるだろう.しかし,祖先たちはどこかを目指したわけでもなければ,英雄に導かれたわけでもなかった.環境の変化に押されてではあったとしても,人類という種が生きのびてきたことに,わたしたちは畏怖を覚え,祖先たちの発明の才と適応力に驚きを感じるが,彼らがあなたやわたしと同じ,普通の人間だったということを忘れてはならない.

この文章は,「人類」をおよそ「言語」に置き換えても成り立つ.人類の発展の経路が最初から決まっていたわけではないのと同様に,言語の歴史の経路も既定路線ではなく,一時ひととき,非目的論的な変化を続けてきただけである.言語とて「積極的に新天地に進出していったわけではない」.個々の言語の「適応力に驚きを感じる」のは確かだが,いずれも「普通の」言語だったということを忘れてはならない.

・ アリス・ロバーツ(著),野中 香方子(訳) 『人類20万年 遙かなる旅路』 文芸春秋,2013年.

2016-12-12 Mon

■ #2786. 世界言語構造地図 --- WALS Online [web_service][syntax][evolution][typology][word_order]

The World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS Online) というサイトがある.世界中の多くの言語を様々な観点から記述したデータベースに基づき,その地理的分布を世界地図上にプロットしてくれる機能を有するツールである.進化人類学の成果物として提供されており,進化言語学や言語類型論にも貢献し得るデータベースとなっている.

検索できる言語的素性の種類は豊富で,音韻,形態,統語,語彙と多岐にわたる.表をクリックしていくことで,簡単に分布図を表示してくれるという優れものだ.素性を組み合わせて分布図を示すこともでき,素性間の相関関係を探るのにも適している.例えば,VO/OV 語順と接置詞 (adposition) 語順の相関について,Feature 83A と 85A を組み合わせると,こちらの分布図が得られる.青と黄緑のマークが目立つが,青は日本語型の「OV語順かつ後置詞使用」を示す言語,黄緑は英語型の「VO語順かつ前置詞使用」を示す言語である.同じように VO/OV と NA/AN の素性 (Feature 83A と 87A) の組み合わせで地図を表示させることもできる(こちら).なお,この2つの例は,名古屋大学を中心とする研究者の方々により出版された『文法変化と言語理論』のなかの若山論文で参照され,論じられているものである.

いろいろな素性を,単体で,あるいは組み合わせで試しながら遊べそうだ.WALS Online は,本ブログでは「#1887. 言語における性を考える際の4つの視点」 ([2014-06-27-1]) でも触れているので,ご参照を.

・ 若山 真幸 「言語変化における主要部媒介変数の働き」『文法変化と言語理論』田中 智之・中川 直志・久米 祐介・山村 崇斗(編),開拓社.294--308頁.

2016-07-20 Wed

■ #2641. 言語変化の速度について再考 [speed_of_change][schedule_of_language_change][language_change][lexical_diffusion][evolution][punctuated_equilibrium]

昨日の記事「#2640. 英語史の時代区分が招く誤解」 ([2016-07-19-1]) で,言語変化は常におよそ一定の速度で変化し続けるという Hockett の前提を見た.言語変化の速度という問題については長らく関心を抱いており,本ブログでも speed_of_change, , lexical_diffusion などの多くの記事で一般的,個別的に取り上げてきた.

多くの英語史研究者は,しばしば言語変化の速度には相対的に激しい時期と緩やかな時期があることを前提としてきた.例えば,「#795. インターネット時代は言語変化の回転率の最も速い時代」 ([2011-07-01-1]),「#386. 現代英語に起こっている変化は大きいか小さいか」 ([2010-05-18-1]) の記事で紹介したように,現代は変化速度の著しい時期とみなされることが多い.また,言語変化の単位や言語項の種類によって変化速度が一般的に速かったり遅かったりするということも,「#621. 文法変化の進行の円滑さと速度」 ([2011-01-08-1]),「#1406. 束となって急速に生じる文法変化」 ([2013-03-03-1]) などで前提とされている.さらに,語彙拡散の理論では,変化の段階に応じて拡散の緩急が切り替わることが前提とされている.このように見てくると,言語変化の研究においては,言語変化の速度は,原則として一定ではなく,むしろ変化するものだという理解が広く行き渡っているように思われる.この点では,Hockett のような立場は分が悪い.Hockett (63) の言い分は次の通りである.

Since we find it almost impossible to measure the rate of linguistic change with any accuracy, obviously we cannot flatly assert that it is constant; if, in fact, it is variable, then one can identify relatively slow change with stability, and relatively rapid change with transition. I think we can with confidence assert that the variation in rate cannot be very large. For this belief there is descriptive evidence. Currently we are obtaining dozens of reports of language all over the world, based on direct observation. If there were any really sharp dichotomy between 'stability' and 'transition', then our field reports would reveal the fact: they would fall into two fairly distinct types. Such is not the case, so that contrapositively the assumption is shown to be false.

Hockett (58) は別の箇所でも,言語変化の速度を測ることについて懐疑的な態度を表明している.

Can we speak, with any precision at all, about the rate of linguistic change? I think that precision and significance of judgments or measurements in this connection are related as inverse functions. We can be precise by being superficial, say in measuring the rate of replacement in basic vocabulary; but when we turn to deeper aspects of language design, the most we can at present hope for is to attain some rough 'feel' for rate of change.

Hockett の言い分をまとめれば,こうだろう.語彙や音声や文法などに関する個別の言語変化については,ある単位を基準に具体的に変化の速度を計測する手段が用意されており,実際に計測してみれば相対的に急な時期,緩やかな時期を区別することができるかもしれない.しかし,言語体系が全体として変化する速度という一般的な問題になると,正確にそれを計測する手段はないといってよく,結局のところ不可知というほかない.何となれば,反対の証拠がない以上,変化速度はおよそ一定であるという仮説を受け入れておくのが無難だろう.

確かに,個別の言語変化という局所的な問題について考える場合と,言語体系としての変化という全体的な問題の場合には,同じ「速度」の話題とはいえ,異なる扱いが必要になってくるだろう.関連して「#1551. 語彙拡散のS字曲線への批判」 ([2013-07-26-1]),「#1569. 語彙拡散のS字曲線への批判 (2)」 ([2013-08-13-1]) も参照されたい.

上に述べた言語体系としての変化という一般的な問題よりも,さらに一般的なレベルにある言語進化の速度については,さらに異なる議論が必要となるかもしれない.この話題については,「#1397. 断続平衡モデル」 ([2013-02-22-1]),「#1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード」 ([2014-02-09-1]),「#1755. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード (2)」 ([2014-02-15-1]) を参照.

・ Hockett, Charles F. "The Terminology of Historical Linguistics." Studies in Linguistics 12.3--4 (1957): 57--73.

2016-07-19 Tue

■ #2640. 英語史の時代区分が招く誤解 [terminology][periodisation][language_myth][speed_of_change][language_change][hel_education][historiography][punctuated_equilibrium][evolution]

「#2628. Hockett による英語の書き言葉と話し言葉の関係を表わす直線」 ([2016-07-07-1]) (及び補足的に「#2629. Curzan による英語の書き言葉と話し言葉の関係の歴史」 ([2016-07-08-1]))の記事で,Hockett (65) の "Timeline of Written and Spoken English" の図を Curzan 経由で再現して,その意味を考えた.その後,Hockett の原典で該当する箇所に当たってみると,Hockett 自身の力点は,書き言葉と話し言葉の距離の問題にあるというよりも,むしろ話し言葉において変化が常に生じているという事実にあったことを確認した.そして,Hockett が何のためにその事実を強調したかったかというと,人為的に設けられた英語史上の時代区分 (periodisation) が招く諸問題に注意喚起するためだったのである.

古英語,中英語,近代英語などの時代区分を前提として英語史を論じ始めると,初学者は,あたかも区切られた各時代の内部では言語変化が(少なくとも著しくは)生じていないかのように誤解する.古英語は数世紀にわたって変化の乏しい一様の言語であり,それが11世紀に急激に変化に特徴づけられる「移行期」を経ると,再び落ち着いた安定期に入り中英語と呼ばれるようになる,等々.

しかし,これは誤解に満ちた言語変化観である.実際には,古英語期の内部でも,「移行期」でも,中英語期の内部でも,言語変化は滔々と流れる大河の如く,それほど大差ない速度で常に続いている.このように,およそ一定の速度で変化していることを表わす直線(先の Hockett の図でいうところの右肩下がりの直線)の何地点かにおいて,人為的に時代を区切る垂直の境界線を引いてしまうと,初学者の頭のなかでは真正の直線イメージが歪められ,安定期と変化期が繰り返される階段型のイメージに置き換えられてしまう恐れがある.

Hockett (62--63) 自身の言葉で,時代区分の危険性について語ってもらおう.

Once upon a time there was a language which we call Old English. It was spoken for a certain number of centuries, including Alfred's times. It was a consistent and coherent language, which survived essentially unchanged for its period. After a while, though, the language began to disintegrate, or to decay, or to break up---or, at the very least, to change. This period of relatively rapid change led in due time to the emergence of a new well-rounded and coherent language, which we label Middle English; Middle English differed from Old English precisely by virtue of the extensive restructuring which had taken place during the period of transition. Middle English, in its turn, endured for several centuries, but finally it also was broken up and reorganized, the eventual result being Modern English, which is what we still speak.

One can ring various changes on this misunderstanding; for example, the periods of stability can be pictured as relatively short and the periods of transition relatively long, or the other way round. It does not occur to the layman, however, to doubt that in general a period of stability and a period of transition can be distinguished; it does not occur to him that every stage in the history of a language is perhaps at one and the same time one of stability and also one of transition. We find the contrast between relative stability and relatively rapid transition in the history of other social institutions---one need only think of the political and cultural history of our own country. It is very hard for the layman to accept the notion that in linguistic history we are not at all sure that the distinction can be made.

Hockett は,言語史における時代区分には参照の便よりほかに有用性はないと断じながら,参照の便ということならばむしろ Alfred, Ælfric, Chaucer, Caxton などの名を冠した時代名を設定するほうが記憶のためにもよいと述べている.従来の区分や用語をすぐに廃することは難しいが,私も原則として時代区分の意義はおよそ参照の便に存するにすぎないだろうと考えている.それでも誤解に陥りそうになったら,常に Hockett の図の右肩下がりの直線を思い出すようにしたい.

時代区分の問題については periodisation の各記事を,言語変化の速度については speed_of_change の各記事を参照されたい.とりわけ安定期と変化期の分布という問題については,「#1397. 断続平衡モデル」 ([2013-02-22-1]),「#1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード」 ([2014-02-09-1]),「#1755. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード (2)」 ([2014-02-15-1]) の議論を参照.

・ Hockett, Charles F. "The Terminology of Historical Linguistics." Studies in Linguistics 12.3--4 (1957): 57--73.

・ Curzan, Anne. Fixing English: Prescriptivism and Language History. Cambridge: CUP, 2014.

2016-05-03 Tue

■ #2563. 通時言語学,共時言語学という用語を巡って [saussure][terminology][diachrony][methodology][history_of_linguistics][evolution]

「#2555. ソシュールによる言語の共時態と通時態」 ([2016-04-25-1]) で,共時態と通時態の区別について話題にした.ところで,Saussure (116--17) は Cours で,通時態と共時態の峻別を説いた段落の直後に,標題の2つの言語学の呼称について次のように論じている.

Voilà pourquoi nous distinguons deux linguistiques. Comment les désignerons-nous? Les termes qui s'offrent ne sont pas tous également propres à marquer cette distinction. Ainsi histoire et «linguistique historique» ne sont pas utilisables, car ils appellent des idées trop vagues; comme l'histoire politique comprend la description des époques aussi bien que la narration des événements, on pourrait s'imaginer qu'en décrivant des états de la langue succesifs on étudie la langue selon l'axe du temps; pour cela, il faudrait envisager séparément les phénomènes qui font passer la langue d'un état à un autre. Les termes d'évolution et de linguistique évolutive sont plus précis, et nous les emploierons souvent; par opposition on peut parler de la science des états de langue ou linguistique statique.

Mais pour mieux marquer cette opposition et ce croisement de deux ordres de phénomènes relatifs au même objet, nous préfèrons parler de linguistique synchronique et de linguistique diachronique. Est synchronique tout ce qui se rapporte à l'aspect statique de notre science, diachronique tout ce qui a trait aux évolutions. De même synchronie et diachronie désigneront respectivement un état de langue et une phase d'évolution.

ここで Saussure は用語へのこだわりを見せている.Saussure が「歴史」言語学 (linguistique historique) では曖昧だというのは,時間軸上の異なる点における状態を次々と記述することも「歴史」であれば,ある共時的体系から別の共時的体系へと時間軸に沿って進ませている現象について語ることも「歴史」であるからだ.後者の意味を表わすためには「歴史」だけでは不正確であるということだろう.そこで後者に特化した用語として "linguistic historique" の代わりに "linguistique évolutive" (対して "linguistic statique")を用いることを選んだ.さらに,2つの軸の対立を用語上で目立たせるために,"linguistique diachronique" (対して "linguistic synchronique") を採用したのである.

このような経緯で通時態と共時態の用語上の対立が確立してきたわけが,進化言語学 ("linguistique évolutive") と静態言語学 ("linguistic statique") という呼称も,個人的にはすこぶる直感的で捨てがたい気がする.

・ Saussure, Ferdinand de. Cours de linguistique générale. Ed. Tullio de Mauro. Paris: Payot & Rivages, 2005.

2016-04-14 Thu

■ #2544. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方 (3) [language_change][evolution][language_myth][teleology][spaghetti_junction]

[2010-07-03-1], [2016-04-13-1]に引き続き標題について.言語変化に対する3つの立場について,過去の記事で Aitchison と Brinton and Arnovick による説明を概観してきたが,Aitchison 自身のことばで改めて「言語堕落観」「言語進歩観」「言語無常観(?)」を紹介しよう.

In theory, there are three possibilities to be considered. They could apply either to human language as a whole, or to any one language in particular. The first possibility is slow decay, as was frequently suggested in the nineteenth century. Many scholars were convinced that European languages were on the decline because they were gradually losing their old word-endings. For example, the popular German writer Max Müller asserted that, 'The history of all the Aryan languages is nothing but gradual process of decay.'

Alternatively, languages might be slowly evolving to more efficient state. We might be witnessing the survival of the fittest, with existing languages adapting to the needs of the times. The lack of complicated word-ending system in English might be sign of streamlining and sophistication, as argued by the Danish linguist Otto Jespersen in 1922: 'In the evolution of languages the discarding of old flexions goes hand in hand with the development of simpler and more regular expedients that are rather less liable than the old ones to produce misunderstanding.'

A third possibility is that language remains in substantially similar state from the point of view of progress or decay. It may be marking time, or treading water, as it were, with its advance or decline held in check by opposing forces. This is the view of the Belgian linguist Joseph Vendryès, who claimed that 'Progress in the absolute sense is impossible, just as it is in morality or politics. It is simply that different states exist, succeeding each other, each dominated by certain general laws imposed by the equilibrium of the forces with which they are confronted. So it is with language.'

Aitchison は,明らかに第3の立場を採っている.先日,「#2531. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction"」 ([2016-04-01-1]) や「#2533. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction" (2)」 ([2016-04-03-1]) で Aitchison による言語変化における spaghetti_junction の考え方を紹介したように,Aitchison は言語変化にはある種の方向性や傾向があることは認めながらも,それは「堕落」とか「進歩」のような道徳的な価値観とは無関係であり,独自の原理により説明されるべきであるという立場に立っている.現在,多くの歴史言語学者が,Aitchison に多かれ少なかれ似通ったスタンスを採用している.

・ Aitchison, Jean. Language Change: Progress or Decay. 3rd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2001.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow